Taadži Liguistics

Author: Lauren Kuffler

MS Date: 12-11-2022

FL Date: 03-01-2023

FL Number: FL-00008A-00

Citation: Kuffler, Lauren. 2022. “Taadži Liguistics.” FL-

00008A-00, Fiat Lingua,

Copyright: © 2022 Lauren Kuffler. This work is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

Fiat Lingua is produced and maintained by the Language Creation Society (LCS). For more information

about the LCS, visit http://www.conlang.org/

Taadži Linguistics

paraat lanjĩ

/paɾaːt lanjĩ/

“first words”

Introduction

The Tade Taadži language grew out of a broader worldbuilding

project begun in late 2020. I wanted to construct a language that

allowed me to play to my strengths, and from which I could work

on my weak points–I felt confident in my culture-building, and in

creating and evolving a written script that would be aesthetically

pleasing while also being feasible to write with authentic tools.

However, With little formal linguistics training, creating a unique

grammar without an Indo-European bias is a difficult process for

me. To get me started, I began with the phonemic inventory of

Proto-Uto-Aztecan and a few aesthetic goals for the writing sys-

tem, and slowly evolved from there. Tade Taadži is thus an ongo-

ing project, and a member of a language family that can provide

a fun space for me to learn and experiment.

Abstract

ngkko odorwà

/ŋ̩kːo odoɾwɐ/

“important teachings”

Tade Taadži is the representative conlang of an ongoing

worldbuilding project, focusing on a culture that arises from dis-

possessed peoples transported to an isolated archipelago. This

article will provide a brief historical context for the language,

describe its grammar and its logo-phonetic writing system. Nota-

ble features include an extensive system of ligatures in formal

texts, and a five-gender personal pronoun system. Any setting-

specific terms provided in the document can be assumed to be

those used by the Taadži culture, rather than local endonyms.

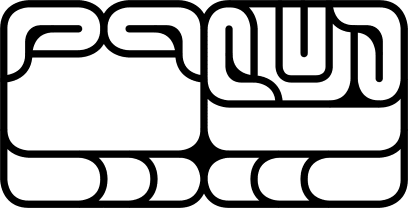

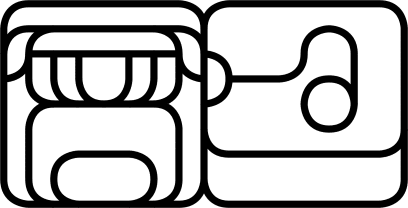

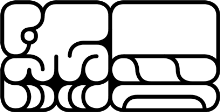

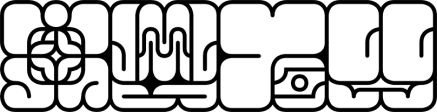

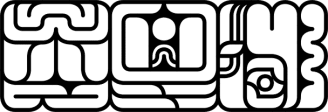

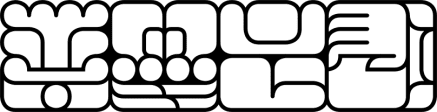

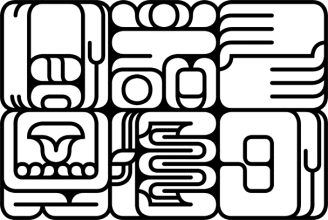

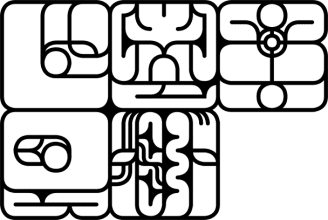

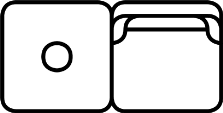

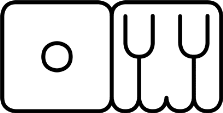

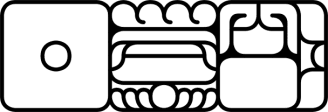

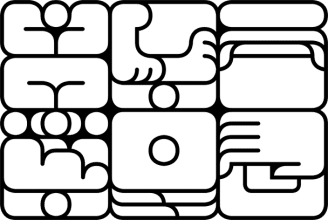

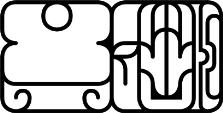

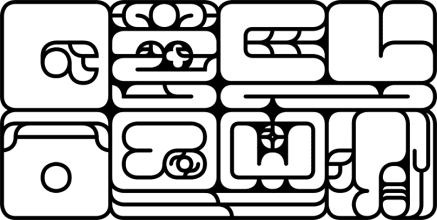

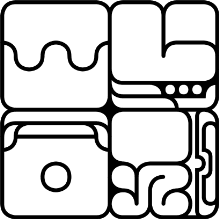

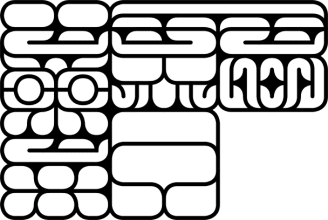

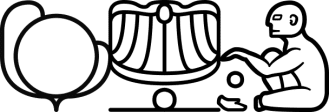

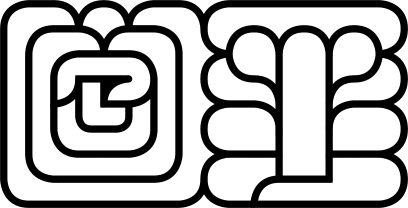

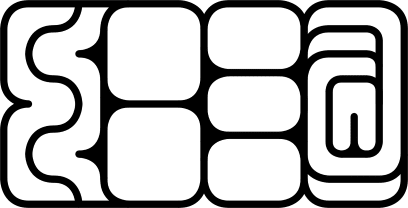

Fig. 1. An atlas of the planet Karawãhe, labeled in Lanje Taadži glyphs. The glyph representing the Naasengo species is redacted, in

accordance with Taadži cultural taboos. The remaining glyphs represent the homeland of the ancestral cultures of the Taadži

(left), and the Taadži themselves (right).

2

Radžuoğğu

/ɾad͡ʒuoɣːu/

History

Tade Taadži originates on an Earth-like plan-

et with near-zero axial tilt. This creates more extreme tempera-

ture gradients, and stronger mid-ocean currents. To simplify the

conlang creation process, this planet features two major human-

oid species, eventually referred to as the Naasengo and the

Taadži.

Geographic isolation kept these species largely

separated from each other. (Fig. 1) The smaller,

gregarious Naasengo that occupied the larger territory gave rise

to the imperialist ʻAgãłè culture, which colonized large portions

of the main continents. After learning of a navigable

passage through the treacherous waters near the

western mountain range, they came in contact with the

ancestors of the Taadži culture.

This species was larger (avg 2.3-2.4m), and evolutionary pres-

sures to adapt to local parasites and strong sunlight left them

hairless, thicker-skinned and possessing dark sclera and a

distinctive green color to their blood, due to high levels of

circulating biliverdin. While their thick skin provided them better

protection from both biting insectoids and sunburn, it left them

less capable of sweating to achieve evaporative cooling.

Decorating the body with mud or other body pigments was a

common strategy to reduce sun exposure.

Local trade and exploration had resulted in some limited contact

between proto-Taadži and southwestern Naasengo cultures, but

their existence had been previously unconfirmed by the ʻAgãłè.

While seemingly primitive to the ʻAgãłè due to their relative lack

of metalworking technology, these proto-Taadži peoples were a

mix of settled and nomadic cultures, many of whom had

well-developed literary traditions, monumental ritual sites and/

or well-established population centers, and some possessed a

far more advanced understanding of medical theory and tech-

nique. Many worshiped celestial bodies as their mythic

ancestors, leading to their eventual name:

Taadžipanu, or Children of the Sun and Moon.

While initially welcoming to the newcomers and establishing

trade, the Taadži cultures eventually began to push back against

colonial projects within their homeland, and the kidnapping of

their people. The ʻAgãłè responded aggressively, with captured

Taadži transported in slave ships to an isolated colonial project

on a mid-oceanic archipelago.

Enslaved Taadži were not permitted to write and deliberately

divided into groups that limited same-culture contact. These

measures were intended to decrease their capability to organize

and rebel, leading to the creation of a pidgin and the loss of

writing technology.

Despite this, the Taadži mounted an increasingly organized

series of slave revolts, contributing to the failure of the colonial

venture. As a result, the ʻAgãłè left the archipelago, leaving the

Taadži behind on the most isolated land mass on the planet.

While poorly adapted to their new environment, enough Taadži

survived to form a genetically viable population. This archipelago

remained isolated from the outside world for centuries to come,

outlasting the ʻAgãłè and possibly the entire Nassengo species.

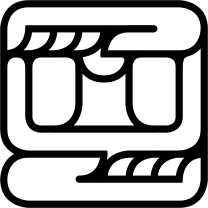

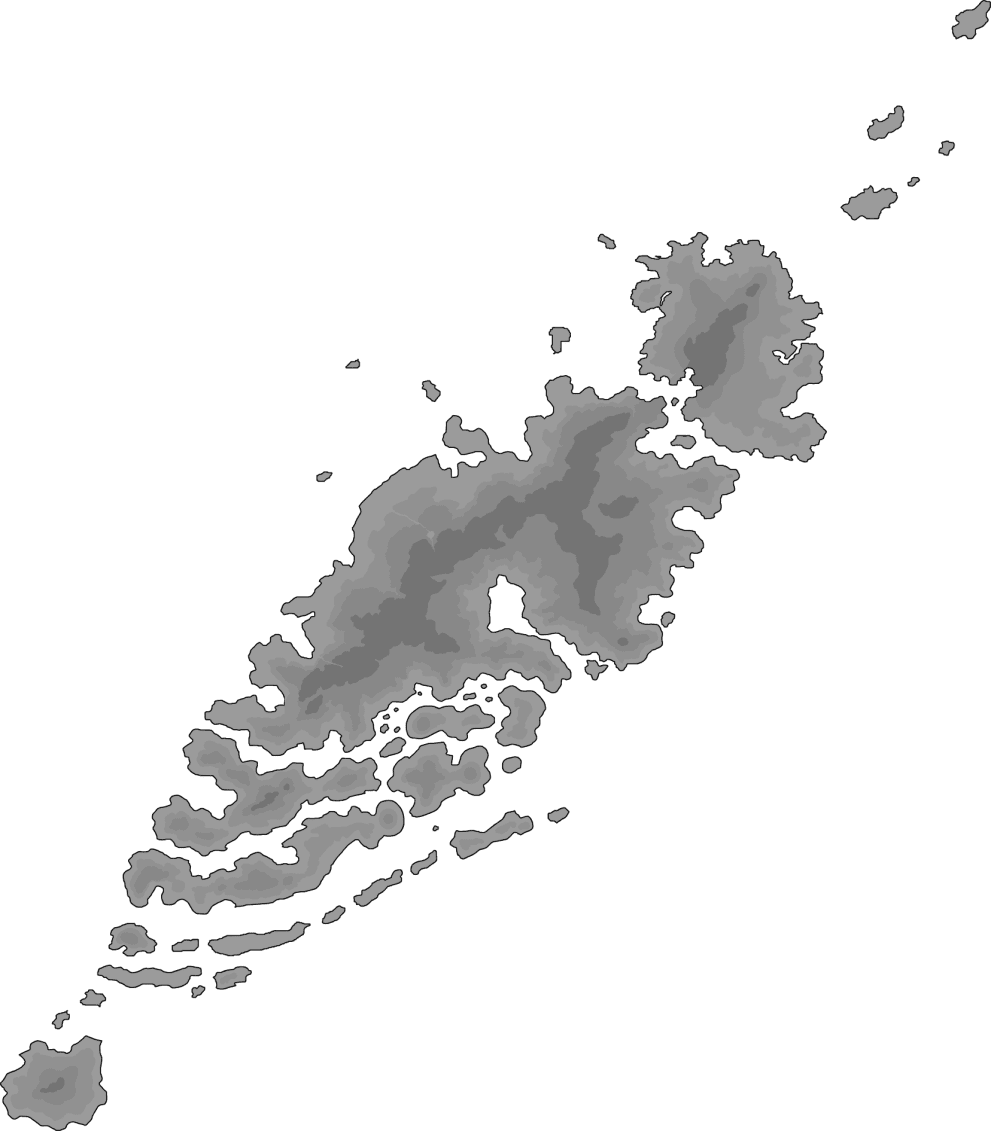

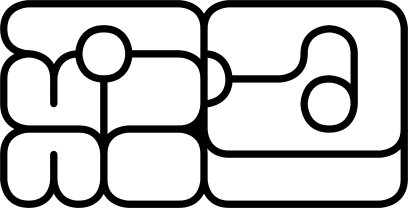

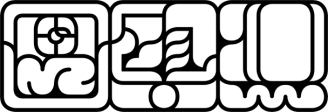

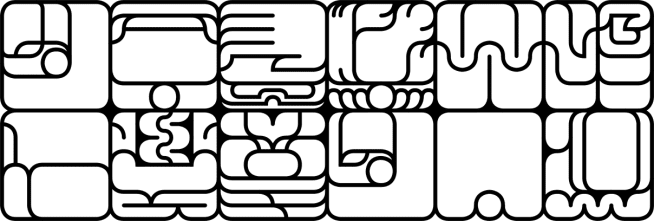

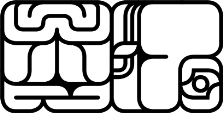

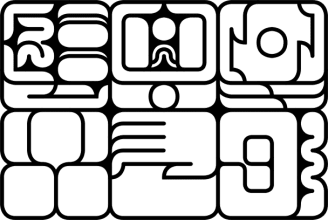

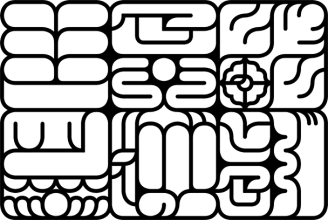

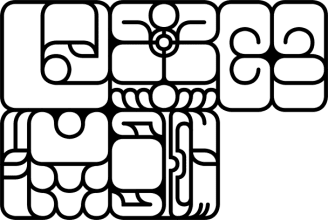

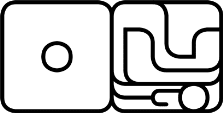

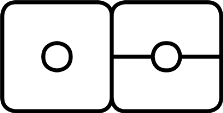

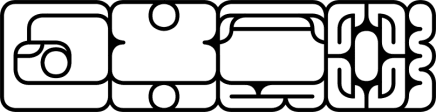

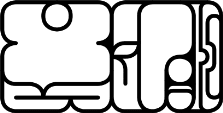

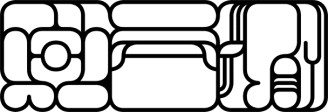

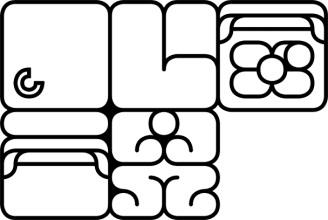

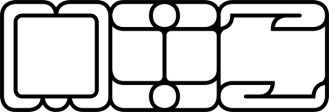

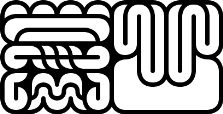

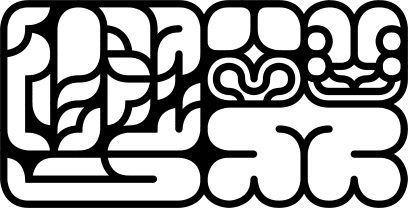

Fig. 2 A map of the Taadži archipelago, or Taadžipanuhe. This project focuses on Tade Taadži, a linguistically conservative eastern

language spoken near the original colony (centered at star).

2

3

While the creole language of the Taadži peoples developed into

multiple branches as they slowly radiated to new foraging and

fishing grounds, this project currently focuses on one relatively

early dialect, Tade Taadži.

proximity.

The sibilant affricates ts/dž can’t follow plosives or sibilants

except t/d, ŋ can’t follow plosives, sibilants or rhotics, rhotics

can’t follow labial(ized) or glottal plosives.

lanjy papaaxẽ

/lanjɨ papaːxẽ/

“word dance”

Linguistics

Tade Taadži has a Nominative-Accusative alignment and an SOV

word order, with OVS subordinate clauses. The language is

head-final, with adjectives and descriptive clauses preceding the

noun or verb they modify, and postpositions are used. The pos-

essee is marked rather than the possessor. The language has

recently transitioned from analytic to mostly synthetic, with

noun-adjective agreement in case and plurality. Verbs feature

optional person-marking.

Length and

Phonotactics

ybamxũ kaanjã

/ɨbamxũ kaːnjã/

“wall (of) sound”

Tade Taadži features contrasting vowel and consonant length.

Until recently, Tade Taadži had no distinction between voiced

and unvoiced consonants. A weak distinction is evolving, but in

most cases voicing is non-contrastive. The basic syllable

structure of Tade Taadži is as follows:

(C){V,S}(C), with S = m, n, ŋ, j, ɫ, and w.

Geminate consonants, long vowels, and nasal vowels are

contrastive versus their basic counterparts. Plosives must be

spaced by a central vowel if compounding would place them in

Stress

Stress defaults to the first

non-affix syllable.

kağ kaanjã

/kaɣ kaːnjã/

“strike sound”

If there are one or more long vowels in a non-final position, the

stress falls on the first long vowel. If there are geminate

consonants, the non-ultimate syllable following the long

consonant or incorporating it as its onset takes the stress, unless

it is an affricate or fricative.

Romanization

lanjkaanjmi syturhe

/lanjɨkaːnjmi sɨtuɾhe/

“written sound from

foreign place”

The romanization used in this text is focused on aiding the

reader in acquiring consistent pronunciation of Tade Taadži, and

follows IPA transcription fairly closely (Table 1). It is thus more

descriptive than the minimal pairs that native Taadži speakers

would identify, including distinctions between voiced and

unvoiced consonants, and distinctions between vowel sounds

that are found in specific phonotactic contexts. Length or

gemination indicated in the romanization with double letters. In

digraphs, the sonorant is doubled. Thus, /ŋː/ is rendered as nng,

/t͡s/ is rendered as tss, and /d͡ʒ:/ is rendered as džž.

Table 1. Phonology and romanization of Tade Taadži. Romanization is listed (in parentheses) when it differs from IPA.

Labial

Coronal

Dorsal

Laryngeal

Alveolar

Palatal

Velar

Glottal

Front Central Back

Place → Man-

ner ↓

Nasal

Plosive

Sibilant

affricate

Fricative

m

p, b

n

t, d

t͡s, d͡ʒ~d͡z (dž)

ɲ (ñ)*

ŋ (ng)

k, g

ʔ (ʻ)

s, z

x, ɣ (ğ)

h

Approximant

w~v

l, ɫ (ł)

j

Rhotic

ɾ̥~ɾ~r (r)

*a marginal phoneme only found in a few words.

ɨ, ɵ

(y, è)

u

ũ

o

õ

Close

Close-

mid

Open

i

ĩ

e

ẽ

a, ɐ

(a, à)

ã

3

4

Nouns and Adjectives

lanjy pavã

/lanjɨ pavã/

“word (of) thing”

There is only a very weak distinction between nouns and

adjectives, which are treated the same grammatically. They are

better thought of as concrete and abstract or descriptive nouns.

Tade Taadži is early in the process of transitioning from an

analytic to a synthetic language, and thus features five fairly

regular declension patterns. Noun and Adjective cases are

Nominative, Accusative, Possessed, Allative, Instrumental, and

Vocative. Adjectives agree with the case of the noun they

modify. Adjectives or modifying nouns come before the primary

noun.

Nominative marks the actor for both transitive

and intransitive verbs, and modifiers of verbs. It

is unmarked in the singular form.

Ozà huumà. /ozɐ huːmɐ/

reptomammal.PL.NOM sleep.STAT

“Animals sleep.”

Accusative marks the patient of transitive verbs.

Naiddahe saangwus haapu.

/naidːahe saːŋwus haːpu/

Naiddahe.NOM shy.prawn.ACC

see.NEARPAST

“Naiddahe saw a darting prawn.”

Possessed marks an object possessed by

something (his book, the person’s word), an

origin (people from the islands), and apposition (my sister, a

healer). Possessed nouns come before the noun they modify,

and can be compound-forming, though the case marker may be

dropped depending on sound similarity. The word order of

(concrete) noun adjuncts also follows this pattern (ex. “face

mask” would be literally rendered “mask (of the) face”).

Uzumi papã kamitsigwis kii.

/uzumi papã kamit͡sigwis kiː/

body.paint.POS moon.NOM

crater.PL.ACC exist.STAT

“The dark markings on the face of the moon are craters.”

Allative marks motion toward (I went to the

house), direction (I went north), and also marks

indirect objects of most verbs (I gave the stone

to her). The Allative comes after the

Nominative and Accusative.

Aratmàpà jazdu idda aannagu. /

aɾatmɐpɐ jazdu idːa aːnːagu/

Aɾatmàpà.NOM sea.ALL go.INFV

want.PRES

“Aratmàpà wants to go to the sea.”

Instrumental acts as the agent of passive voice

construction (I was hit by the stick), and to

indicate location (I work in the field), time (I work today),

participation in an action (she benefited from her mother’s love),

substance of composition (a wheel of cheese), source (a portion

of food), and comitative statements (I went in the company of

the fisherman). Instrumental nouns follow the noun they modify.

Laranwà kushyngyr swtsddur sydurpy.

/laɾanwɐ kushɨŋɨɾ̥ sw̩ t͡sdːuɾ̥ sɨduɾpɨ/

tree.PL.NOM east.PL.INST wind.INST

curve.STAT

“Trees from the east are bowed because of the wind.”

Vocative identifies an addressee, and is the

default case in most dialects for referring to the

gods. Some dialects may use the vocative only as

a pejorative, while others are beginning to use the vocative as a

topic marker.

Xummmaa, nga ʻus tsã pavà pavapso?

/xumːaː ŋa ʔus t͡sã pavɐ pavapso?/

friend.VOC 2S.NOM ACC Q.INFML therefore

do.NEARPAST-that.ACC

“Oh friend, why did you do that?”

Table 2. Taadži declensions

Singular

NOM ACC POS ALL

INST

VOC

1. -/t/d/ts/dž/

s/z/ʻ/w/h/(V)

2. -/y/i/e/(r)

3. -/N/Ṽ/(jV)

4. -/u/o/(r)

5. -a(r)

Standalone

–

–

–

–

–

–

-wus -di

-du

-ddur

-dà

-us

-e

-u

-yr

-uu

-ns

-us

-as

ʻus

-mi

-my

-mr

-maa

-i

-i

it

-u

-a

up

-ur

-ar

yr

-oo

-àà

àà

Plural

NOM ACC POS ALL

INST

VOC

1. -/t/d/ts/dž/

s/z/ʻ/w/h/(V)

-zà

-zat

-zabi -zà

-zur

-zàà

2. -/y/i/e/(r)

-Ṽ

-Ṽs

-ẽ

-(V)

-(V)ngyr -(V)nguu

3. -/N/Ṽ/(jV)

-wà

-was

-wi

-wy

-wur

-wàà

4. -/u/o/(r)

-wi

-wis

-wi

-wu

-wur

-woo

5. -a(r)

-agà

-agas -agi

-agà

-agar

-agàà

Standalone particles acting as case markers may be used for

emphasis, to separate different noun phrases in the same case,

and/or to mark the end of a subordinate clause. For the

nominative case, an appropriate pronoun may be used (see page

7). This is a remnant of the analytic grammar of the early Taadži

creole which has maintained useful grammatical functions.

Sot suwus sage hadžedžaazat joovũ mavarà yr jaddiigopu

xummr taat ʻus haapu.

/sot suwus sage

had͡ʒed͡ʒaːzat joːvũ

mavaɾɐ ɨɾ̥ jadːiːgopu

xum̩ ːɾ̥ taːt ʔus haːpu/

3S.NOM pot.ACC take.PRES shellfish.ACC.PL water cook.INF INST

bay.ALL friend.INST 3SM.NOM ACC see.PAST

She saw that he took the pot to the bay to boil shellfish with a

friend.

4

5

Verbs

paʻwanjy

/paʔwanjɨ/

“doing word”

Verbs have four tenses: Remote Past, Past,

Present, and Future. Tense is strictly absolute

(centered on the “now”) unless directly quoting someone.

Table 3. Taadži tenses. The 3rd and 4th conjugations are

differentiated by etymological roots of a given verb.

Verb Stem Remote Past Present Future Imperative

-a,ã,i,ĩ,x,p,t

-Vdžu

-Vpu

-Vgu

-Vzi

-Vdžã

-e,o

-u

-u(s)

-Vdže

-Vpe

-Vge

-Vzi

-Vdžã

-adže

-ape

-age

-azi

-adžã

-udžas

-upas -ugas

-uzis

-udžã

Remote Past tense is usually used to refer to events

that occurred more than one day ago. It can also

function as a discontinuous past tense, where the event

has experienced a change. It may also be used for

recent events that the speaker was present for but does not

clearly remember.

Tsudu tyjddadžu. /t͡sudu tɨjdːad͡ʒu/

beach.ALL 3SF.go-RPAST

“She went to the beach (before today/but isn’t there anymore)”

Tsudu jinmr tyjddadžu.

/t͡sudu jinm̩ ɾ̥ tɨjdːad͡ʒu/

beach.ALL today.INST 3SF.go-RPAST

“I think she went to the beach today”

Past tense or Simple Past tense refers to events within

the past day, or when the speaker wants to emphasize

the clarity of their memory.

Tsudu jinmr tyjddapu.

/t͡sudu jinm̩ ɾ̥ tijdːapu/

beach.ALL today.INST 3SF.go-PAST

“She went to the beach today”

Present and Future tenses can be used for

statements that would refer to the continuous

or perfective aspect, but not for gnomic or

attributive (see below).

Tsudu tyjddagu. /t͡sudu tijdːagu/

beach.ALL 3SF.go-PRES

“She’s going to the beach”

The Infinitive is the uninflected form of the verb with its stem

included, and can be used as the Gnomic aspect, describing

general truths rather than specific events. The infinitive

is often used in multi-verb constructs, including some

with grammatical functions (Table 4).

Tsudu tyjdda. /t͡sudu tɨjdːa/

beach.ALL 3SF.go

“Everyone knows that she goes to the beach.”

Attributive verbs can be created by removing the verb

stem. This is not represented in the writing system.

They are treated as an adjective, and precede any word

they modify.

Kavax sugarmavat tetaadžus kavaxege.

/kavax sugaɾmavat tetaːd͡ʒus kavaxege/

burn.ATTR fire-pit.NOM child.ACC

warm-PRES

“The burning fire pit warms the child.”

Perfective aspect is created by taking the infinitive

verb and adding the verb kus (“to come”). This is a

serial verb construction with kus taking most

inflection, except for nominative person marking (see pg. 6).

Pavà anngar tsigur, xitssejanns kav haadi

nanmy aʻukiju kusadže.

/pavɐ aŋːaɾ̥ t͡siguɾ̥ xit͡sːejanːs kav haːdi

nanmɨ aʔukiju kusap/

make.INFV dry.clay.INST rock.INST,

wet-clay.ACC watch.ATTR eye.POS sun.ALL

1P-set.down PERF.RPAST

“We laid the clay in the sun to make bricks.”

Passive verbs are formed in a similar manner, using

the auxiliary verb su (“to take”). The subject of the

verb is placed in the instrumental case, and the

object remains in the accusative.

Jaadns ʻogmr sukype sadže.

/jaːdn̩s ʔogm̩ ɾ̥ sukɨpe sad͡ʒe/

storm.ACC delicate.plant.INST break PASS.RPAST

The delicate plant was broken by the storm.

Hypothetical mood is created in the same way,

with the auxiliary verb kaanja (“to hear”).

Uvaswovus jinmr irtyr rat su kaanjapu.

/uvaswovus jinmɾ̥ iɾtɨɾ̥ rat su kaːnjapu/

earthquake.ACC bridge.INST today.INST cut

PASS HYP.PAST

“The bridge could have been cut in today’s

earthquake.”

The hypothetical mood can also be used to construct if/then

statements. The “then” clause is the primary clause, and takes

the hypothetical mood. The “if” clause is dependent. When

describing a hypothetical action, the clause is marked with the

instrumental case. When describing a precondition beyond one’s

power to affect, the allative case is used.

Aʻujoovũnavarazisai yr kmg tsaʻiwus ajihopà

kaanjazi.

/aʔujoːvũnavaɾazisai ɨɾ̥ km̩ g t͡saʔiwus ajihopɐ

kaːnjazi/

1P-boil-FUT-this INST eat.ATTR safe.ACC

this.be.at.INFV HYP.FUT

“If we boil this, then it will be safe to eat.”

Axohuumazi kushyxanã up laramiigopu tyjazzaddà kaanjazi.

/axohuːmɐzi kushɨxanã up laɾamiːgopu tɨjazːadːa kaːnjazi/

that.calm.sea-FUT tomorrow.NOM ALL

reef.ALL 3SF.boat.travel HYP.FUT

“If tomorrow has calm seas, then she’ll

paddle out to the reef.”

5

6

Imperative mood is formed either through the verb

tsã (“to require” or “must”), or through its

grammaticized suffix form –Vdžã.

Laranwadu ngakahha tsagu!

/laɾanwadu ŋakahːa t͡sagu/

forest.ALL 2S.run must-PRES

“You must run to the forest!”

Tsawus kapu pavadžã! /t͡sawus kapu pavad͡ʒã/

health.ACC 2S.ALL make-IMP

“Be healthy!” (or less literally, a formal “Hello!”)

Verbs can optionally be marked for person in the nominative

and accusative case in most dialects of the language, with some

additionally marking the instrumental case. This is not required,

nor are pronouns required if sufficient context is established. In

multi-verb constructions, the nominative marking is applied to

the first verb, and the accusative and/or instrumental marking is

applied to the final verb.

Note: If a vowel is phonotactically required to attach a person

marker to a verb, but none is given in the table, then an echo

vowel is used. If the preceding syllable has a consonantal

nucleus, it is either echoed or /ɨ/ is used.

Axoggudarà

/axogːudaɾɐ/

3P.FAR.NOM-teach-1S.ACC-3P.NEAR.INST

“They teach me about that/them.”

Serial verb construction is possible in Tade Taadži. The initial

verb in a serial construct takes nominative person marking. All

non-final verbs and are kept in the infinitive. The first verb takes

nominative marking, and the final verb takes accusative,

instrumental, and/or tense marking.

Kare Hyb Patsaahi pnʻowaranwas rarizi

mavarawapasai.

/kare hɨb pat͡saːhi pn̩ʔowaɾanwas rarizi

mavarawapasai/

All jump moon.fish.NOM tuber.PL.ACC 3S.AND

-gather cook.PAST-3PNEAR

Kare Hyb Patsaahi gathered the tubers and cooked them.

Table 4. Other verb conjugations in Tade Taadži.

Mood/Form/

Voice/etc.

Conjugation/Inflected

Auxiliary Verb

Meaning

V + stem

Infinitive

Attributive V – stem

To X

the X-ing /Noun/

Perfective

INFV + kus (“to come”) X-ed; Finish X-ing

Passive

Hypothetical INFV + kaanja (“to hear”) would/could/might X

INFV + su (“to take”)

is/was/will be Xed

Table 5. Person marking on Tade Taadži

Verb Marking

NOM

ACC

INST

1S

2S

t(o)-

-t, -dà

-(o)t

ng(a)-

-k(à)

-kat, -gat

3S Fem.

3S Lean Fem.

ty-

pi-

3S Androgynous

ra-

3S Lean Masc.

3S Masc.

ki-

ta-

-s, -ze

-t,-di

-r(à), -à

-k(u)

-t, -dà

-(z)at

-(b)it

-(r)at

-(g)it

-yt, -dyt

Plural

NOM

ACC

INST

1P

2P

3P Near

3P Far

aʻu-

aka-

aj(i)-

ax(o)-

-(i)t

-sà

-sai

-so

-rat

-rage

-rà

-rage

6

7

Pronouns

Tade Taadži has first, second,

and third person pronouns,

which take declension. The first and second person pronouns

have singular and plural forms.

Lanjy mĩ

/lanjɨ mĩ/

“word (of) all”

Their written glyphs function both independently and as radicals

for verb person-marking. (For more about the writing system,

see pg. 11)

Third person pronouns are split into five grammatical genders,

each matching a social role within Taadži culture. These roles are

loosely mapped onto a continuum of most to least feminine, but

the actual realization of these roles is inconsistent across

cultures, and has minimal correlation to sex or reproductive role.

Nearness counts as 2 steps towards masculine/feminine for

female/male speakers, 1 step in either direction for all others.

Familial nearness is dependent on the culture and context.

There is a weak remnant of a grammatical gender system in the

endings of nouns and adjectives, which is mostly used to

determine the use of near/far person markers on verbs in

informal speech. Adjectives no longer agree with the gender of

their noun, but poetic or deliberately archaic speech may use

personal pronouns in agreement with a noun’s gender.

Sot kapyğmi harawus paduu tymavadžusai.

/sot kapɨɣm̩ i haɾawus paduː tɨmavad͡ʒusai/

3F.NOM village.POS ancestor.ACC 1P.ALL

3F.NOM.tell.story.RPAST-3P.NEAR.ACC

“She tells us a story about the ancestor of her

village.”

Taat harazat odorõ taanngare kiiguso.

/taːt haɾazat odoɾõ taːŋːaɾe kiːguso/

3M.NOM ancestor.PL.ACC thought

3M.NOM.crush able.to-PRES-3P.FAR.ACC

“He isn’t making any sense”,

lit. “He could confuse the ancestors.”

Sot– translated to English as “she/her/hers”.

Pit– translated to English as “xe/xer/xers”.

Ran– translated to English as singular “they/them/theirs”.

Kur– translated to English as “e/em/eirs”.

Taat – translated to English as “he/him/his”.

Table 6. Taadži pronouns

Singular

NOM ACC POS ALL

INST VOC

1S

2S

tuu

taas rii

lanu

ladi

laas

nga kàà

kii

kapu kadi kaas

3S Fem.

sot

sade dà

sadu sadi saas

3S Lean Fem.

pit pide pi

pidu pidi paas

These pronouns are only used for people who have been

introduced to the speaker, or members of the same cultural

group who wear unambiguous signs of their social role, in dress,

body paint, or tattoos. Some communities only use gendered

pronouns in familiar or extremely casual speech.

3S Androgynous ran

rane rà

rabu radi

raas

3S Lean Masc.

kur kure ku

kubu kudi kaas

3S Masc.

taat taade tàà

tabu taadi taas

Plural

NOM ACC POS ALL

INST VOC

When referring to children, outsiders, or

unmarked Taadži adults, impersonal pronouns

(it or this/that) are used. Taadži religious

practices believe in an immortal, reincarnated

spirit that had a role assigned to it upon their

creation by the gods, which is forgotten upon

entering a physical existence. Thus, children are expected to

declare their own role during a maturation ceremony, at which

point gendered pronouns may be used. Note that verb person

marking for these impersonal pronouns is not used, thus formal

speech tends to limit person marking to first and second person

only.

1P

2P

aduu saduu iduu paduu raduu aatuu

agà sagà

igà

pagà ragà aagà

3P Near

ajit

sajit

ijit

pajit rajit aajit

3P Far

ağat sağat iğat pağat rağat aağa

Impersonal

NOM ACC POS ALL

INST VOC

Near (this, it)

jit

jur

Far (that, it)

xat

xur

ji

xi

jur

xur

ji

xi

jàà

xaa

Plural pronouns do not reflect gender in the

third person, instead splitting between “near”

and “far” categories: A speaker will use the

“near” pronoun for a group that is close to

them on the gender spectrum or familial

relation, and the “far” pronoun for all others.

7

8

Interrogatives

Odorlanjy

/odorlanjɨ/

“teaching word”

Tade Taadži has a pair of basic question

words used for formal/inanimate and

informal/animate queries, hhat and tsã. In their base form they

can be most easily translated as “what?” or “who?” if used

alone. If placed at the end of a sentence, they

act as a marker for a yes/no question.

Conjugated forms of hhat and tsã produces

more specific meaning. These can be placed in sentences to ask

specific questions in context. If conjugation isn’t sufficient,

helper words can be used to clarify meaning (see table below).

Nominative or Accusative forms can be translated

as “what?” or “who?”

Hhat yymypwas suudžu?

/hːat ɨːmɨpwas suːd͡ʒu?/

“Q.FML.NOM fermentation.jar.PL.ACC open.RPAST”

“Who opened the fermenting food?”

Pit tsans sudu kiipu?

/Pit t͡sans sudu kiːpu?/

“3SDF.NOM Q.INFML.ACC jar.ALL give-PAST”

“What did xe put in that jar?”

Joowmiwirdi hhat kiigu?

/Joːw̩ miwiɾdi hːat kiːgu?/

“boat.POS Q.FML give-PRES”

“Whose boat is that?”

Possessed forms ask “what kind of?” or “what?”, specifically in

the context of something’s possessed items or attributes.

Hhadi rywywus ngahaap?

/hːadi rɨwɨwus ŋahaːp?/

“Q.FML.POS bird.ACC 2S-see.PAST”

“What kind of bird did you see?”

Table 7. Compound question words

Instrumental case can be used to ask “how?”

Taadži hawus łè anngatsigus hhaddur pavà?

/Taːdʒi hawus łè aŋːatsigus hːadːuɾ̥ pavɐ?/

“person durable.ACC AUG brick.ACC

Q.FML.INST make.GNOM”

“How does one make such strong bricks?”

Allative forms signify “to what?”, “to where?” or “to whom?”

depending on context.

Tsamy ngiddagu? /Tsamɨ ŋidːagu?/

“Q.INFML.ALL 2S.go-PRES”

“Where are you going?”

Syğwis hhadu kiizi? /Sɨɣwis hːadu kiːzi?/

“food.ACC.PL Q.FML.ALL give-FUT”

“Who will receive the food?”

Vocative forms are generally used for invoking deities or for

(often) profane emphasis, as in “which god?”

or “what the hell?”

Hhadà xitsus kii? /hːadɐ xitsus kiː?/

“Q.FML.VOC rain.ACC give.GNOM”

“Which god brings the rain?”

Tsamàà ngatadege? /Tsamɐː ŋatadege?/

“Q.INFML.VOC 2S-speak-PRES”

“What the f*** are you talking about?”

Placing an unconjugated question word in the place of a verb

can create the meaning of “to do what?”. If

this is not sufficient to disambiguate intent,

person marking may be attached to the ques-

tion word.

Nga xi tsã? /ŋa xi t͡sã/ 2S there.INST Q.INFML

You went there to do what?

Tade Taadži

Glyph

Gloss

Translation

Tade Taadži

Glyph

Gloss

Translation

Hhat łè

Q DISC

How far?

Hhazà hmrỹ

Hhat kavaxe

Q wait

How long? (≤ day) Hhat ntà

Hhat ijãã

Q time

How long? (≥ day) Hhazà nzà

Hhadu

kavaxu?

Hhaddur

kavaxyr

Hhaddur

ijãmr

Q.ALL

wait.ALL

Q.INST

wait.INST

Q.INST

time.INST

Until when?

Hhat rumà

When?/At what

time?

Hhat he

What day?

Hhaddur hyr

Hhat hmry

Q finger

Which? (≤ 5)

Hhat pava

Q.PL

finger.PL

Q hand

Q.PL

hand.PL

Q roots

How much?

(≤ 5)

Which? (≥ 6)

How much?

(≥ 6)

What kind?

Q place

Where?

Q.INST

place.INST

Q make

From

where?

Why?

8

9

Postpositions

paarawo

/paːrawo/

“near far”

There are two main postpositions that cover

many spatial and temporal relationships in

Tade Taadži: paarà and łè. These are referred to as the Associa-

tive and Dissociative postpositions.

Paarà covers concepts of motion toward, into, closeness, and to

be among something.

Łè has the contrasting meaning of motion away, out of, distance,

and to be apart from something.

Tsigu paarà paʻo łè tsudu aʻukuushazi.

/t͡sigu paːɾɐ paʔo ɫɵ t͡sudu aʔukuːshazi./

Rock.ALL ASC and DISC shore.ALL

1P-swim-FUT

“We’ll swim out to the rock and back to the shore.”

Kur tenannakapde kmga tsigu

paarà kushyr xanmr kiddazi.

/kuɾ tenanːakapde km̩ ga t͡sigu paːɾɐ

kushɨɾ xanm̩ ɾ kidːazi/

3DM.NOM shrine.POS tooth.ALL

rock.ALL ASC 3DM.go-FUT

“E will go into the mountain shrine tomorrow.”

Syğhus łè tykupas.

/sɨɣhus ɫɵ tɨkupas/

hunting-ground.ACC DISC

3F.NOM.come.PAST

“She has come back from the hunting ground.”

Paarà mavaddur aʻuhybaguso.

/paːɾɐ mavadːuɾ̥ aʔuhɨbaguso/

ASC now.INST 1P.NOM-be.at-PRES-

3PFAR.ACC

“We are close to them now. “

Rywydu saduu łèʻo łè hybagu.

/ɾɨwɨdu saduː ɫɵʔo ɫɵ hɨbagu/

Bird.NOM 1P.ACC very.far DISC

remain-PRES

“The bird stays far away from us.”

(Note: as łè already means “far”, this sentence also features the

intensified form łèʻo, which clarifies the meaning

of the phrase.)

Ydzã tsigwur paarà łèèsage.

/ɨdzã t͡sigwuɾ̥ paːɾɐ ɫɵːsage/

Idol.NOM stone.PL.INST ASC hide-PRES

“The idol is hidden among the stones.”

Maanu tsigu ratypaarar łè hybà.

/Maːnu t͡sigu ɾatɨpaːɾaɾ̥ ɫɵ hɨbɐ/

Chest.NOM rock.NOM group.INST DISC

be-at.GNOM

“The weathered mountain stands apart from the range.”

Both paarà and łè can be used as intensifiers, which color the

adjective or action they refer to. Paarà acts a diminutive, and łè

acts as an augmentative.

Te paarà tsaazà uuzu łèʻo łè kuushap

kii.

/te paːɾɐ tsaːzɐ uːzu ɫɵʔo ɫɵ kuːshap

kiː/

Small.PL DIM fish.PL river.ALL very.far AUG swim able.to.GNOM

“The smaller fish can swim further up the river.”

Both words can be used in phrases that provide other spatial or

temporal distinctions, such as pospur (“back (anatomy)”) to

create postpositional phrases meaning “behind” (pospur paarà)

versus “far behind” (pospur łè). Some of these are commonly

used as set phrases.

Opanwàà raduu lapo łè kave.

/opanwɐː raduː lapo ɫɵ kave/

Mother.goddess.PL.VOC 1P.INST body

DISC watch.

“The mother goddesses watch from above

us.”

Pospur paarà, aduu paduu jahybà tsã.

/Pospuɾ paːɾɐ, aduː paduː jahɨbɐ t͡sã/

Back ASC, 1P.NOM 1P.ALL decide.INF

IMP.GNOM.

“On the other hand, we must make decisions

for ourselves.”

Grammatical Suffixes

Certain suffixes are generative and can form new words. These

are not always required to bring a word into a new grammatical

role or alter meaning, they do decrease ambiguity. Note that

since the distinction between nouns, adjectives and adverbs is

rather weak, these suffixes provide specific guidance as to the

meaning. For example, if one begins with the verb jaado (“to

shout”), one can produce jaadã (“a shout”), jaador (“loud(ly)”),

and jaadotja (“intense(ly)”).

Table 8. Grammatical suffixes and examples.

Role

Suffix Radical Example

N→ V

-(u)x(y)

Adj → V

-(y)ngjy

anngà -> anngàxy

sand -> shift; be unsteady

xos -> xosyngjy

old -> to ponder

V; Adj; POS

→ N

-ĩ/-ã/

-(i/a)ngo

jaado -> jaadã

shout -> a shout

V → Adj

-(u)r

N → Adj

-(o)t

Adj; V →

Adv

-(a)tja

jaado -> jaador

shout -> loud(ly)

anngà -> anngàt

sand -> sandy; fine

jaado -> jaadotja

shout -> intense(ly)

9

10

Numbers

Hmrihaat

/hmɾihaːt/

Number(s)

Tade Taadži features a base 6 number system, also called “senary” (abbreviated to “Sen”). When finger counting, Taadži will use

the fingers on their dominant hand to count up to five, and their non-dominant hand counts multiples of six.

Numbers 1-6 and all senary places (powers of 6 rather than powers of 10) have unique names up to 1×66. All numerals at a given

base besides the final are placed in the Possessed case, and the base is in the nominative. The final base or numeral may display

noun case agreement. Paʻo (“and”) may be placed after senary bases where the numeral 1 would appear in Arabic numerals, ex-

cept for the first position. ex. mi paʻo hã (“Six and four”, Sen 14, Dec 10). Written forms of the numbers can combine senary bases

with paʻo or digits at that base. Tade Taadži does not yet have a true word for “zero”, thus the word for “nothing” is used below.

Table 9. Numerals

Decimal

Heximal

Glyph

NOM

ACC

POS

ALL

INST

VOC

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

1

2

3

4

5

10

36

100

216

1,000

sàà

sas

si

sà

sar

sàà

ng

so

tar

hã

kyr

mi

kyt

kũ

ngãs

ngi

nge

ngmr

ngàà

sus

tas

hãs

kus

mins

si

ti

su

tà

sur

tar

soo

tàà

hãi

hãe

hãr

hãwàà

ky

mi

ku

my

kyr

mr

kuu

màà

kyʻus

kydi

kydu

kyddur

kydàà

kns

kũ

kmy

kmr

kmàà

1,296

10,000

nantà

nanus

nandi

nandu

nanddur

nandàà

7,776

100,000

pantà

panus

padi

padu

padur

padàà

46,656

1,000,000

mità

miʻus

midi

midu

midur

midàà

Ngi nantà ngi kũ ky kyt

ngi mi tar

/ŋi nantɐ ŋi kũ kɨ kɨt ŋi

mi tar/

1.POS 6^4 1.POS 6^3

5.POS 6^2 1.POS 6 3

Dec 1701, Sen 11,513

Pantàpaʻo nantàpaʻo

hãikũ kytpaʻo hãimi hã

/pantɐpaʔo nantɐpaʔo

hãikũ kɨtpaʔo hãimi hã/

6^5-and 6^4-and 4.POS

-6^3 6^2-and 4.POS-

6^1 4

Dec 10,000, Sen 114144

Simità kynantà kykyt

hãimi hã

/simitɐ kɨnantɐ kɨkɨt

hãimi hã/

2.POS-6^6 5.POS-6^4

5.POS-6^2 4.POS-6^1 4

Dec 100,000,

Sen 2,050,544

10

11

Pavar lanjy

/pavaɾ̥ lanjɨ/

way-to write

Writing System

The Lanje Taadži writing system is

logo-syllabic, arising relatively quickly after

the loss of writing technology, but is completely isolated from

previous scripts. The

script is usually written

with a reed pen when

paper is available,

carved into wax

codices for temporary

documents, and carved

into stone or stucco for

important texts.

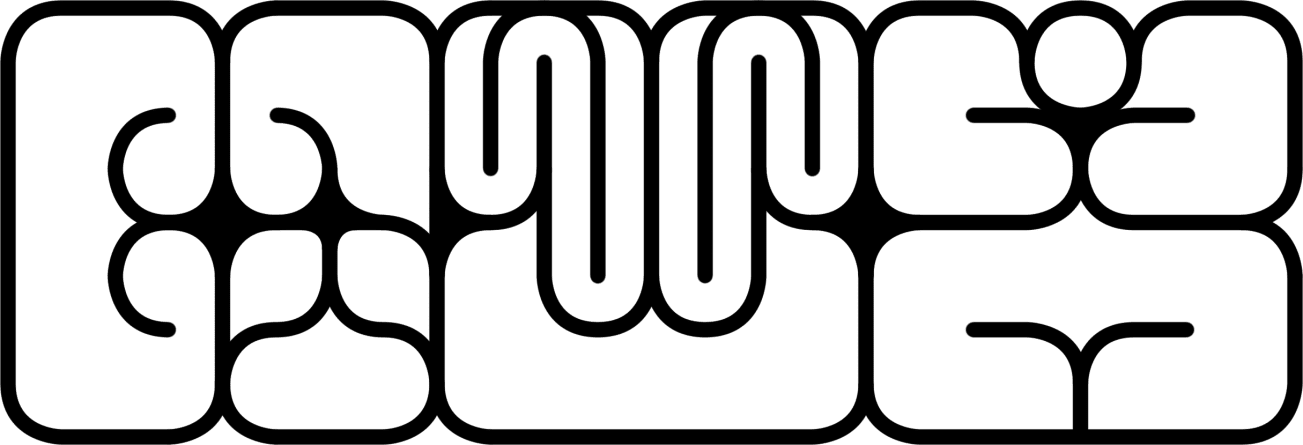

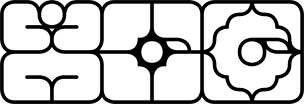

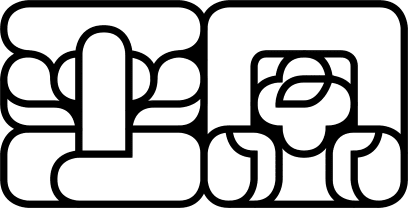

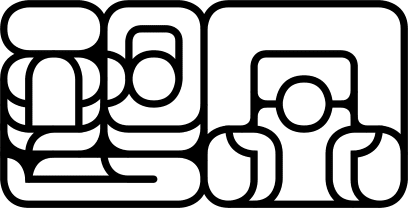

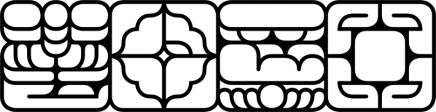

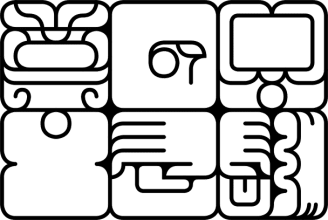

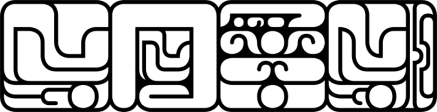

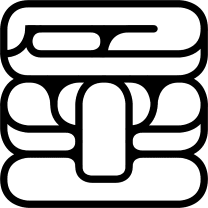

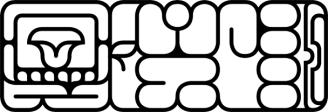

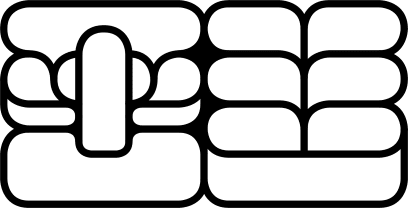

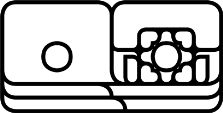

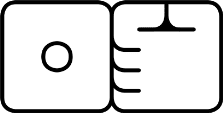

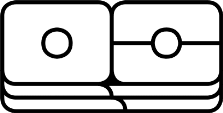

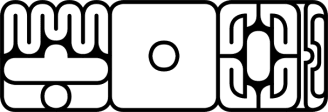

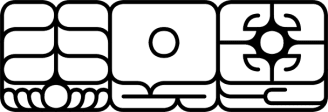

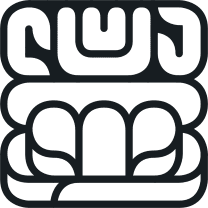

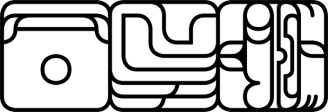

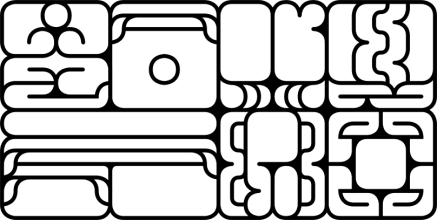

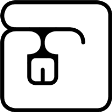

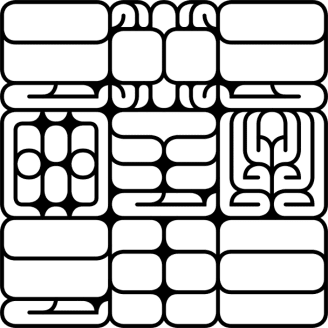

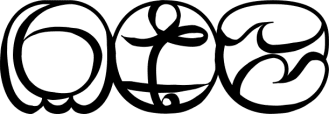

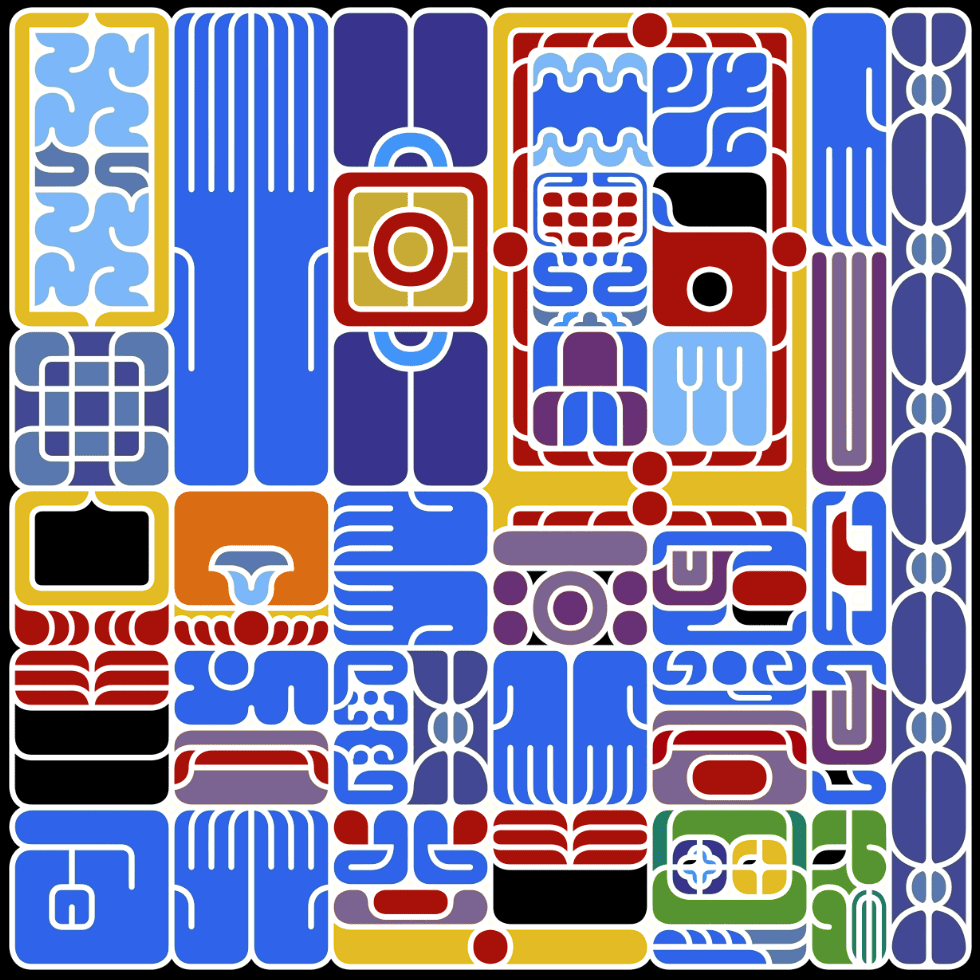

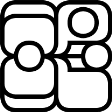

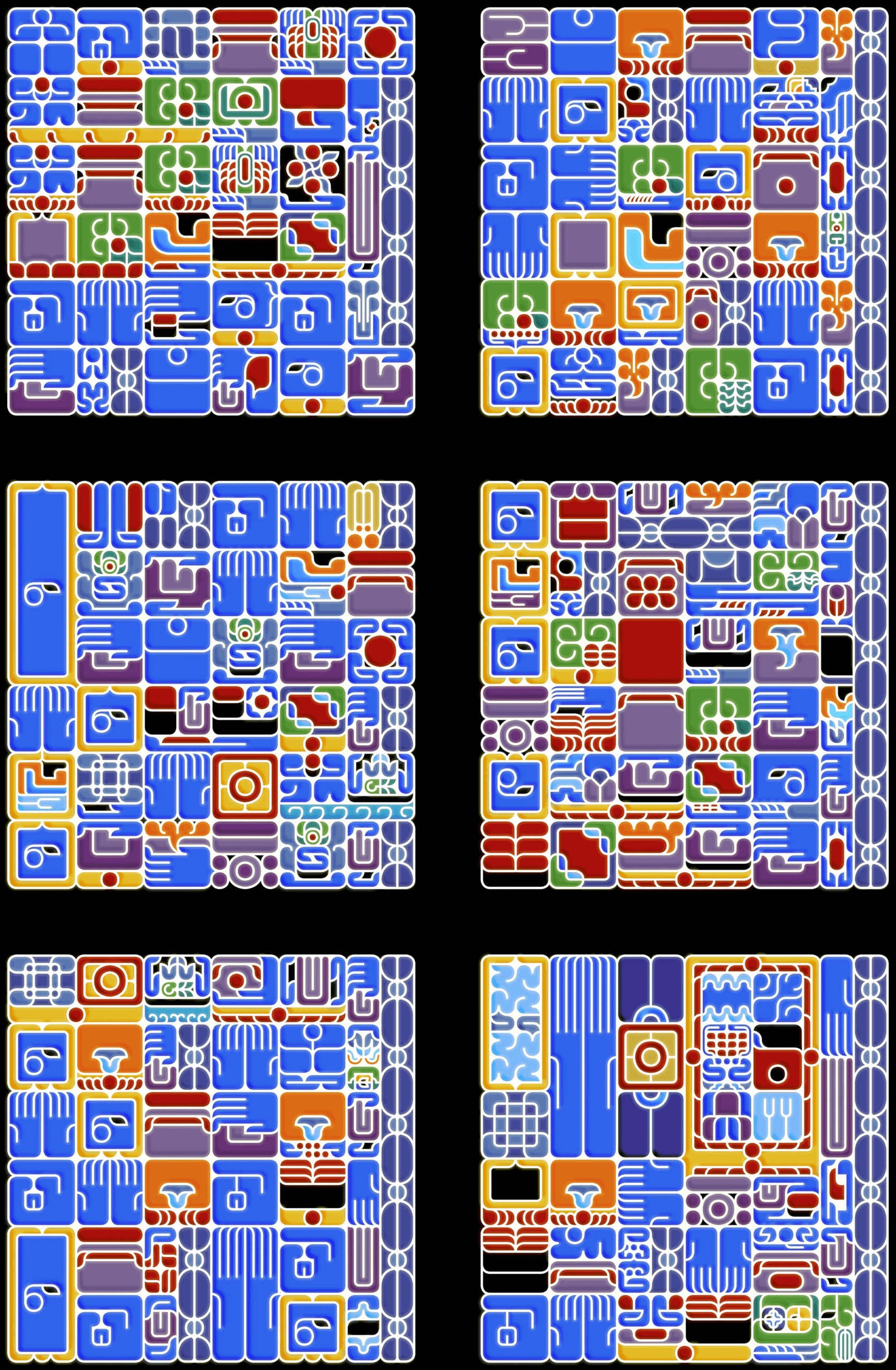

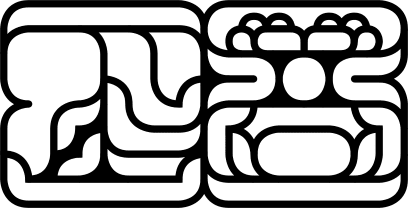

Fig. 3 Archaic, formal, handwritten and open

script versions of the sentence Xat mrjas kii, /

xat mɾ.jas kiː/ (that good give.GNOM),

translated as “That’s pleasing”, or “I love that”.

Originally, glyphs could take any shape, but would often be fit

into a loose grid of equal-sized spaces. As the writing system

evolved and simplified, the grid structure became more

pronounced. In modern formal texts, glyphs are square and have

self-containing outlines. Handwritten text is often more

rounded, and some scribal traditions are developing open

glyphs.

Glyphs encode for multi-syllabic words, and compound words

may sometimes rendered as a single glyph. This is often

achieved through simplified radicals, by containing one glyph

within another, or both.

When a word features accompanying grammatical information,

it is written in a reduced form and shares the glyph block with

these grammatical elements. Nominative nouns are unmarked,

as are stative and infinitive verbs.

Many Taadži cultures consider the ideal proportions of a text to

be a block of 6×6 glyphs. Informal texts may be of variable line

length, but a formal text will attempt to fill a full 6×6 block as

naturally as possible.

Texts may include some amount of ligature between glyph

blocks. These ligatures are read once for every block that they

cross. Ligatures joining noun phrases may be commonly seen in

informal texts. Formal texts will commonly feature cross-row

ligatures of repeated glyphs or grammatical elements. The value

of the glyph is read every time the reader encounters it as they

progress through the text.

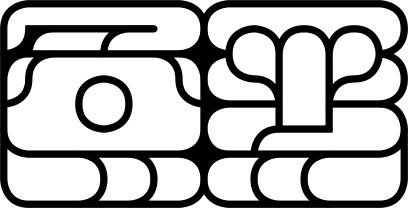

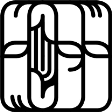

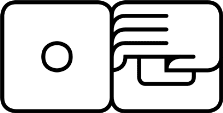

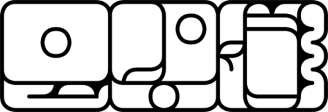

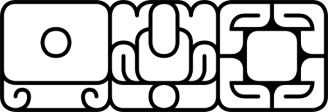

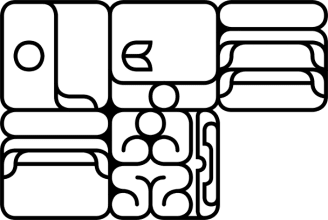

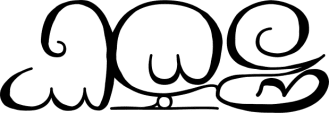

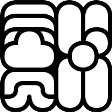

Fig. 5 A. Three alternate forms of kii (“to give”, “to exist”, “to be able to”).

B. Three alternate forms of the third person singular

androgyne pronoun, ran. The first is marked solely with a

simplified version of traditional face paint, the second is

marked with a phonogram (raʻn, “dark”), and the third is

marked with a radical representing a quarter-moon, the day

on which a religiously active androgyne Taadži is expected to

pray to the celestial gods.

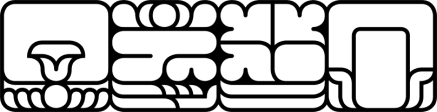

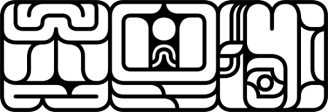

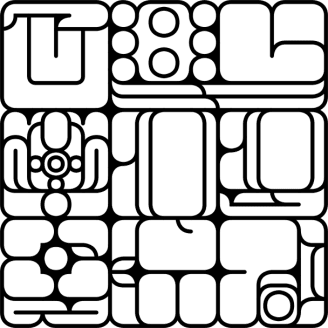

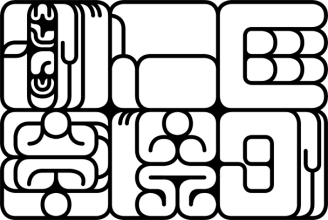

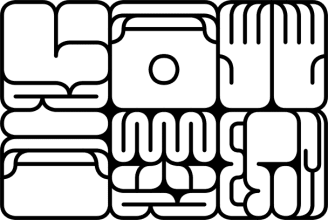

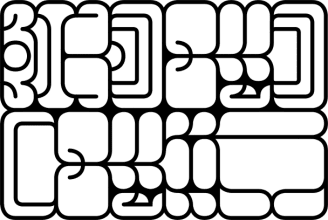

Fig. 4 A stanza from the Taadži myth describing the creation of life. The glyphs

are decorated with color, and rendered with white lines on a black

background, the traditional medium for especially important documents. Note

the use of ligatures that cross rows and columns of the text, rotation of the

“and” glyph (a pair of hands), as well as two variations on the “teach” radical

determined by their size (row 4, column 5, versus row 5, column 6). For a full

reproduction and translation of this text, please see page 13-15.

Rotation of glyphs and use of decorative ligatures are occasion-

ally used, usually to link thematically similar elements. These do

not change the reading of the text. Rotation is usually not

employed for verbs, and some rotations are not allowed for

pronouns or person markers.

Variation in Glyph Structure

Some glyphs may have multiple valid forms, and their style of

presentation may differ depending on local written dialect or the

artistic flair of the writer. Personal pronouns are especially

prone to this, as they represent adornments or body paint

associated with particular social roles, which may vary between

cultures. Texts meant for mass consumption may establish

pronoun forms at their outset, incorporate phonetic radicals, or

incorporate moon phases religiously associated with each

gender.

Of special note are glyphs relating to the Naasengo species. To

avoid committing their name to text, the body of the glyph is

either completely filled in with ink, or the square is left blank.

Some dialects may substitute the euphemistic term Saawanjy,

lit. “Unnamed” (see page 1-2).

11

12

For foreign words and concepts that are difficult to visually ex-

press, phonograms are constructed from pre-existing glyphs.

Due to the syllable structure of Tade Taadži, these phonograms

are often not 1-to-1 matches. Phoneme length and consonant

value are somewhat flexible in phonographic use. When no pho-

nogram exists that matches the onset and coda, underspelling is

common for word-internal consonants, while at word bounda-

ries, overspelling may be used (see page 16). This syllable struc-

ture also lowers the likelihood that Tade Taadži will adopt a

purely phonetic writing system in the foreseeable future, though

an alphabet or abjad may potentially develop in time.

When transcribing a foreign word or phonogram, determinative

glyphs may be included by the writer to provide context. This

determinative is usually not pronounced.

The practice of marking words with a determinative is most

common in written documents exchanged between groups

along the jagged and inaccessible southeast coast, due to more

extreme sound changes which have arisen in this area (see page

2).

Fig. 6 A. Two valid ways of writing iirà, “clean”, colorful”,

“young”, “bright”, “to wash”. The first is composed of

“light” (iiwa) and half (raddur), the second “foam” (idžà) and

“part” (rate). B. “Quenya” rendered in Taadži glyphs (xwyja,

lit. “to the houses-sea voyage”), and accompanied by a deter-

minative glyph (tade, “language” or “to say”). Note also that

one of the component phonograms (xwy, “house.ALL”) is

inflected, a valid method for generating desired phonograms

or more elegant logographic readings. C. Radicals for use in phonograms, indi-

cating alternate readings for the radical they contain: to read the word in its

entirety, or read only the final syllable.

12

13

13

14

In the early world, our people were nothing.

Taadži saas radžur łè karawãddur kiidžžu.

/ˈtaː.d͡ʒi saːs ˈɾa.d͡ʒuɾ̥ ɫɵ ˈka.ɾa.wã.dːuɾ̥ ˈkiː.d͡ʒːu/

taadzi.NOM nothing.ACC ash.INST DISC world.INST

be.RPAST.RPAST.

Only the greatest spirits walked,

Aratwà łè oğğwà xaddur ngot iddadžžu.

/ˈa.ɾat.wɐ ɫɵ ˈoɣː.wɐ ˈxa.dːuɾ̥ ŋot iˈdːa.d͡ʒːu/

powerful.PL.NOM AUG spirit.PL.NOM there.INST alone

walk.RPAST.RPAST

and they slowly learned the world.

Aratwà łè oğğwas karawãddur rova odorodžže.

/a.ɾat.wɐ ɫɵ oɣː.was ˈka.ɾa.wã.dːuɾ̥ ro.va ˈo.do.ɾo.d͡ʒːe/

powerful.PL.ACC AUG spirit.PL.ACC world.INST slowly learn.RPRP

They learned the magic that sits in all elements.

They made the first life.

Moggadi Iiwmi karejoğğwàà paraazat odorwas pavadžžu.

/moˈgːa.di ˈiː.w.mi ˈka.ɾeˈjoɣː.wɐː paˈɾaː.zat ˈo.doɾ.was

ˈpa.va.d͡ʒːu/

stillness.POS light.POS master.PL.VOC first.ACC

living.thing.PL.ACC create.RPRP

They made plants, and they rejoiced in their children,

Ajit larwas pavadžžu paʻo, tengwu pohodžže

/ˈa.jit ˈlaɾ.was ˈpa.va.d͡ʒːu ˈpa.ʔo ˈteŋ.wu ˈpo.ho.d͡ʒːe/

3P.NEAR.NOM plant.PL.ACC make.RPRP and children.ALL

rejoice.RPRP

and taught them how to create also.

paʻo, ajit łè pav larwy odorodžže.

/ˈpa.ʔo ˈa.jit ɫɵ pav laɾ.wɨ ˈo.do.ɾo.d͡ʒːe/

and 3P.NEAR.NOM DISC create.INF plant.PL.ALL teach.RPRP

Hit oğğwà kavaxmi karẽs karawas odorodžže,

/hit ˈoɣː.wɐ ˈka.vax.mi ˈka.ɾẽs ˈka.ɾa.was ˈo.do.ɾo.d͡ʒːe/

this.PL.NOM spirit.PL.NOM magic.POS all.ACC.PL element.ACC.PL

learn.RPRP

But mated plants could not make anything,

Saa paʻo, larwà saa karus pavadžžu.

/saː ˈpa.ʔo ˈlaɾ.wɐ saː ˈka.ɾus ˈpa.va.d͡ʒːu/

not and plant.PL.NOM not anything.ACC create.RPRP

But their creation remained a mystery.

no matter how they tried.

Saa paʻo, pavmi sajit saa oğğadžže.

/saː ˈpa.ʔo ˈpav.mi ˈsa.jit saː oˈɣːa.d͡ʒːe/

not and creation.POS 3P.NEAR.ACC not remember.RPRP

To learn of their creation, some decided to create.

Pav jahybadžžu ngtsaduu pavmi sajit odor.

/pav ˈja.hɨ.ba.d͡ʒːu ˈŋ̍.t͡sa.duː ˈpav.mi ˈsa.jit ˈo.doɾ/

create.INF choose.RPRP some.NMNZ.NOM creation.POS

3P.NEAR.ACC learn.INF

They failed many times, but they were patient.

Ajit ogĩ ngaavadžžu saa paʻo, ʻogadžžu.

/ˈa.jit ˈo.gĩ ˈŋaː.va.d͡ʒːu saː ˈpa.ʔo ˈʔo.ga.d͡ʒːu/

3P.NEAR.NOM many fail.RPRP not and be.patient.RPRP

Then they learned to mate,

Ajit harazotad odorodžže paʻo, ijãmr łè,

/ˈa.jit ˈha.ɾa.zo.tad ˈo.do.ɾo.d͡ʒːe ˈpa.ʔo ˈi.jã.m̩ ɾ̥ ɫɵ/

3P.NEAR.NOM mate.INF learn.RPRP and time.INST DISC

and eventually they learned that some mating could create.

Ajit pavà ngtsap harazotad pav kiidžžu.

/ˈa.jit ˈpa.vɐ ˈŋ̍.t͡sap ˈha.ɾa.zo.tad pav ˈkiː.d͡ʒːu/

3P.NEAR.NOM create.STAT some.NOM mating.NOM create.INF

able.to.STAT

Agxat łè surudžžu paʻo, saa pavadžžu.

/ˈa.ɣat ɫɵ ˈsu.ɾu.d͡ʒːu ˈpa.ʔo saː ˈpa.va.d͡ʒːu/

3P.FAR.NOM DISC try.RPRP and not create.RPRP

They did not understand why, and they wept.

Agxat saa oğğadžže paʻo, agxat ʻaahàadžžu

/ˈa.ɣat saː oˈɣːa.d͡ʒːe ˈpa.ʔo ˈa.ɣat ˈʔaː.hɐː.d͡ʒːu/

3P.FAR.NOM not understand.RPRP and 3P.FAR.NOM weep.RPRP

Eventually some plants became very elderly

Aazat ntsap larwà łè xozat tuuğadžu

/ˈha.zat ˈŋ̍.t͡sap ˈlaɾ.wɐ ɫɵ ˈxo.zat ˈtuː.ɣa.d͡ʒu/

later some plant.PL.NOM AUG elderly.ACC became.RPRP

and they died, which shocked their mothers.

paʻo, agxat hurhybàdžžu paʻo, panwà saanghadžu.

/ˈpa.ʔo ˈa.ɣat ˈhuɾ.hɨ.bɐ.d͡ʒːu ˈpa.ʔo ˈpan.wɐ ˈsaːŋ.ha.d͡ʒu/

and 3P.FAR.NOM died.RPRP and mother.PL.NOM shocked.RPRP

But the spirits within them remained,

Saa paʻo, oğğwà agxat paara kiidžžu,

/saː ˈpa.ʔo ˈoɣː.wɐ ˈa.ɣat ˈpaːɾa ˈkiː.d͡ʒːu/

not and spirit.PL.NOM 3P.FAR.NOM ASC exist.RPRP

And so they created pure combinations of elements.

and when other plants mated,

Paʻo, ajit ngpavagi ngkwi karawas pavadžžu.

/ˈpa.ʔo ˈa.jit ˈŋ̍.pa.va.gi ˈŋ̍.kiː ˈka.ɾa.was ˈpa.va.d͡ʒːu/

and 3P.NEAR.NOM pure.POS combine.NMZ.POS element.ACC.PL

create.RPRP

paʻo xat mavat yymwà larwà harazotadedžže

/ˈpa.ʔo xat ˈma.vat ˈɨːm.wɐ ˈlaɾ.wɐ ˈha.ɾa.zoˌta.de.d͡ʒːe/

and this time when other plant.PL.NOM mated.RPRP

they climbed into their seeds and grew again.

Then the masters of Stillness and Light

Xatmavadà, Moggadi paʻo Iiwmi aratwàà karejoğğwàà,

/ˈxat.ma.va.dɐ moˈgːa.di ˈpa.ʔo ˈiː.w.mi ˈa.ɾat.wɐː

ˈka.ɾeˈjoɣː.wɐː/

that time.NOM, stillness.POS and light.POS great.VOC

master.PL.VOC

learned how other matings could influence the creation.

ajit pavns hobupyyma yymã harazotad odorodžže.

/ˈa.jit ˈpav.n̩s ho.buˈpɨː.ma ˈɨː.mã ˈha.ɾa.zo.tad ˈo.do.ɾo.d͡ʒːe/

3P.NEAR.NOM creation.ACC influence.STAT other.NOM

mating.NOM learn.RPRP

oğğwi larwà pizà kudžžas paʻo tuuğadžžu

/ˈoɣː.wi ˈlaɾ.wɐ ˈpi.zɐ ˈku.d͡ʒːas ˈpa.ʔo ˈtuː.ɣa.d͡ʒːu/

spirit.PL.POS plant.PL.NOM seeds.ALL entered.RPRP and

grow.RPRP

They made themselves so small to do this, that they could

not hold their memories.

agxat tẽs tuuğadžžu oğğ saa kiidžžu

/ˈa.ɣat tẽs ˈtuː.ɣa.d͡ʒːu oɣː saː ˈkiː.d͡ʒːu/

3P.FAR.NOM small.PL. ACC become.RPRP remember.INF not

able-to.RPRP

14

15

They lived again, grew, learned new things, and died.

Motion and Dark created the swimming creatures,

Agxat podja odorodžže, tuuğadžžu, iirà odorodžže,

/ˈa.ɣat ˈpo.dja ˈo.do.ɾo.d͡ʒːe ˈtuː.ɣa.d͡ʒːu iːɾɐ ˈo.do.ɾo.d͡ʒːe/

3P.FAR.NOM again live.RPRP grow.RPRP new learn.RPRP

Then they returned to gather up their old memories,

xatmavat hurhybàdžžu. Riz mawatswdžžagà oğğwy

podjajddadžžu,

/ˈxat.ma.vat ˈhuɾ.hɨ.bɐ.d͡ʒːu riz ˈma.wa.t͡swˌd͡ʒːa.gɐ ˈoɣː.wɨ

ˌpo.djajˈdːa.d͡ʒːu/

that time.NOM, die.RPRP gather.INF old.PL.ALL memory.PL.ALL

return.RPRP

and found that they were now wiser.

agxat mioğğus łè odormr tuuğadžžu kavedžže.

/ˈa.ɣat ˈmi.o.ɣːus ɫɵ ˈo.dor.m̩ ɾ̥ ˈtuː.ɣa.d͡ʒːu ˈka.ve.d͡ʒːe/

3P.FAR.NOM wise.ACC DISC life.INST become see.RPRP

Other great spirits began to create together,

Yymwà aratmà łè oğğwà pav pohodžže,

/ˈɨːm.wɐ ˈa.ɾat.mɐ ɫɵ ˈoɣː.wɐ pav ˈpo.ho.d͡ʒːe/

other powerful.PL.NOM AUG spirit.PL.NOM create begin.RPRP

They made new things from the elements,

agxat iiragas pavwas karawi ragxat pavadžžu,

/ˈa.ɣat ˈiː.ɾa.gas ˈpav.was ˈka.ɾa.wi ˈɾa.ɣat ˈpa.va.d͡ʒːu/

3P.FAR.NOM new.PL.ACC thing.PL.ACC element.PL.POS

3P.FAR.INST create.RPRP

each according to their masteries.

kare karawã yywas pavwas pav kiidžžu.

/ˈka.ɾe ˈka.ɾa.wã ˈɨːwas ˈpav.was pav ˈkiː.d͡ʒːu/

every.NOM element.NOM different.PL.ACC thing.PL.ACC cre-

ate.INF able.to.RPRP

Uvas paʻo Raʻn joovns tsaazat pavadžžu,

/ˈu.vas ˈpa.ʔo ˈɾa.ʔn̩ ˈjoːv.n̩s ˈt͡saː.zat ˈpa.va.d͡ʒːu/

motion.NOM and dark.NOM water.PL.ACC creature.PL.ACC cre-

ate.RPRP

Motion and Light created the flying creatures,

Uvas paʻo Iiwã karehybagas rywyzat pavadžžu,

/ˈu.vas ˈpa.ʔo ˈiː.wã ˈka.ɾeˌhɨ.ba.gas ˈrɨ.wɨ.zat ˈpa.va.d͡ʒːu/

motion.NOM and light.NOM flying.PL.ACC creature.PL.ACC cre-

ate.RPRP

Stillness and Dark created the roots of the earth.

Moggat paʻo Raʻn oprĩs laranwas pavadžžu.

/ˈmo.gːat ˈpa.ʔo ˈɾa.ʔn̩ ˈop.ɾĩs ˈla.ɾan.was ˈpa.va.d͡ʒːu/

stillness.NOM and dark.NOM earth.PL.ACC roots.PL.ACC cre-

ate.RPRP

These ate the plants and each other,

Hit larwas paʻo yymwas odorwas kmgadžžu,

/hit ˈlaɾ.was ˈpa.ʔo ˈɨːm.was ˈo.doɾ.was ˈkm̩ .ga.d͡ʒːu/

these.PL.NOM plant.PL.ACC and other.PL.ACC creature.PL.ACC

eat.RPRP

and sped their reincarnation, learning less,

karẽ kahhawo lapohopadžžu paʻo, tepaara odorodžže

/ˈka.ɾẽ kaˈhːa.wo ˈla.poˌho.pa.d͡ʒːu ˈpa.ʔo teˈpaː.ɾa ˈo.do.ɾo.d͡ʒːe/

all.NMNZ faster live.RPRP and less learn.RPRP

but they had more time to ponder between lives.

saa paʻo, ognsłè karns panagiiddur oğğadžže.

/saː ˈpa.ʔo ˈog.n̩s.ɫɵ ˈkaɾ.n̩s pa.naˈgiː.dːuɾ̥ oˈɣːa.d͡ʒːe/

not and more.ACC everything.ACC heaven.INST think.RPRP

15

16

Abbreviations

Ratelanjy /ratelanjɨ/

“piece-word”, also

“radical”

Acknowledgments

David J. Peterson for the invitation to submit to Fiat Lingua, and

Yosh000 and Spartan Creeper for editing assistance.

Dàvat Pityrsy /dɐvat pitɨrsɨ/

“walk(ing) fire, jade (of

the) graceful dancer”

Jos(o) tarsãã /jos tarsãː/

“water two, three not-

thing”

saapadi tsaʻitmavataʻos

/saːparãdi t͡saʔitmavataʔos/

“Light green blast animal

from prawn-talks-to-moon”

Nominative

Accusative

Possessed

Allative

Instrumental

Vocative

Plural

NOM

ACC

POS

ALL

INST

VOC

PL

RPAST; RP Remote Past Tense

Past Tense

PAST

Pesent Tense

PRES

Future Tense

FUT

Imperative

IMP

Infinitive

INFV

Attributive

ATTR

Perfective

PERF

Hypothetical

HYP

1st Person Singular

1S

2nd Person Singular

2S

3rd Person Feminine

3S.F

3rd Person Demi-Feminine

3S.DF

3rd Person Androgynous

3S.A

3rd Person Demi-Masculine

3S.DM

3rd Person Masculine

3S.M

1st Person Plural

1P

2nd Person Plural

2P

3rd Person Near

3P.N

3rd Person Far

3P.F

Q.FML

Inanimate/Formal Question Marker

Q.INFML Animate/Informal Question Marker

Associative postposition

ASC

Dissociative postposition

DISC

Augmentative

AUG

Diminutive

DIM

Nominalizing suffix

NMZ

16