Section II: Phonetics and Phonology and Section III:

Morphology

Author: Madeline Palmer

MS Date: 03-12-2012

FL Date: 04-01-2012

FL Number: FL-000007-00

Citation: Palmer, Madeline. 2012. Section II: Phonetics

and Phonology and Section III: Morphology.

In Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred:

A Grammar and Lexicon of the Northern

Latitudinal Dialect of the Dragon Tongue.

FL-000007-00, Fiat Lingua,

Copyright: © 2012 Madeline Palmer. This work is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

!

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

Fiat Lingua is produced and maintained by the Language Creation Society (LCS). For more information

about the LCS, visit http://www.conlang.org/

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

Table of Contents

For

Sections II & III

Section II: Phonetics and Phonology……………………………………………………………………………………………………..2

2.1. Overview……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..2

2.2. A Note on the Orthography of this Paper………………………………………………………………………………3

2.3. Vowels………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..4

2.4. Semi-Vowels……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….4

2.5. Consonants………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….5

2.6. Phonology…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..6

2.6.1. Consonant Assimilation………………………………………………………………………………………….7

2.6.2. Vowel Assimilation………………………………………………………………………………………………..9

2.6.3. Semi-Vowel Assimilation……………………………………………………………………………………….11

2.6.4. Tense Marker Assimilation……………………………………………………………………………………11

2.7. Consonant Clusters…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….12

2.8. Deletion of Repeated Final and Non-Final Syllables……………………………………………………………..12

§2.9. Stress………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..13

§2.10. The Draconic “Accent”………………………………………………………………………………………………….…13

Section III: Morphology………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………17

3.1. Overview……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………17

3.2. Root Forms…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………19

3.3. Derivational Structure…………………………………………………………………………………………………………20

3.4. Particles……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..21

3.5. Inflection of Affixes……………………………………………………………………………………………………………21

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

Section II:

Phonetics and Phonology

2.1. Overview

Davis once scrawled in the margin of his notes that the draconic language was “a whole bunch of

hissing and every other unpleasant sound you can imagine thrown in there just to torment those who speak

it…and listen to it!” This is a slightly biased description—one which he later changed—although it is

accurate in that the draconic language is replete with an inventory of sounds which make it sound hissing,

sibilant and breathy, as can be expected by the nature of the language’s speakers. This section goes over the

phonetic inventory of the draconic languages; the sounds which make it up; they way in which they are

pronounced, or the nearest possible way for those who are not dragons to pronounce them; as well as the

way these sounds are altered when coming into contact with one another. At first brush, Srínawésin

sounds extremely alien and often unpleasant to hear. Although Davis notes that if you ever have the

opportunity to hear a dragon speak in its native language for any amount of time, this language can be quite

beautiful, the alien and foreign quality never quite goes away. The phonetic aspects which most separate

Srínawésin from the younger races’ languages are:

Continuant Sounds

The phonetic inventory of all languages of which I am familiar with have stop consonants1

both voiced (b, d, g) and unvoiced (p, t, k) to varying degrees, but they all possess a few stop

consonants as a matter of course. The Dragon Tongue for one reason or another has not a single

true stop consonant in its inventory, by far preferring continuant sounds such as s, x, w, y, h, ł, r as

well as a unique sound š (as depicted in this orthography). Davis once posited that this was due to

the construction of their vocal passageway although most of the Kindred which he met and

conversed with spoke several Qxnéréx languages quite well despite the plethora of stop sounds found

therein. After discussing the matter at length with his sources, Howard discovered that while

dragons could reproduce the various sounds in our languages, they had difficulty doing so, managing

it only by various tricks, much as a ventriloquist learns to speak without the use of their lips.

Thus, I am quite sure that the physical construction of the Kindred’s vocal passageway limits

their ability to fully stop the air leaving their throats without closing off the air passage entirely and

thus interrupting the ability to speak. This would explain the lack of true stop consonants in

Srínawésin and this feature lends a hissing, lispy quality to the Dragon Tongue.

Affricate Sounds

Affricate sounds are those sounds produced when the air passage is stopped then released

with a slightly restricted quality, producing a half-stop/half-continuant sound such as in the English

chair (which is a combination of the ‘t’ and ‘sh’ sounds). Although the Dragon Tongue does not

possess any true stops, it does possess a group of sounds which are close to full stops or affricates,

written in this paper as qs, qx, and ts. My only explanation for the lack of stops but the inclusion of

affricates in the draconic language is that the easiest method used to stop the passage of air

necessitates a fricative sound following it (much as the s in dogs is pronounced as a /z/ due to various

pronunciation factors in rapid human speech) unless concentrated effort is put into it. Several of the

affricates found in Srínawésin are, to my knowledge, unique or at least rare as separate phonemes

within a language and these sounds are often the most difficult for humans to reproduce. These

sounds lend both a hissing as well as tongue-tying difficulty to the dragons’ language, and along

with unvoiced vowels (see below) are responsible for the “foreign accent” which all Qxnéréx

speaking the Dragon Tongue apparently have.

1 Stop consonants are those given above, p, b, t, d, k, g as well as glottal stops where the passage of air through the mouth is stopped

for a moment then released, thus producing the desired sound.

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

Voiced/Unvoiced Distinctions: The distinction between voiced and unvoiced sounds (the

vibration of the vocal chords vs. not vibrating them as in p and b) is common throughout all the

languages of humans, such as the first sounds in English’s to and do, for instance, or the final sounds

in Old Irish macc and mag. Srínawésin possesses this distinction but in a very unique way. All

consonants in the Dragon Tongue are voiceless, spoken with a whispering or breathy quality.

Although consonants are all voiceless, vowels are divided up into voiced and unvoiced vowels (á, é, í,

and ú in the former case and a, e, i, and u in the latter)! This strange feature seems to be due to

particularities of the dragons’ speech apparatus, they do not possess vocal chords as we do, but in

order to make a voiced sound they instead vibrate a membrane deeper in their chest. This membrane

is easily vibrated when their throat is open (as in pronouncing vowels) but not so easily when

constricted (as in making consonant sounds). Davis believed that the Shúna’s extremely good

hearing easily made up for this “deficiency” (as a human would call it) as they were capable of

hearing even entirely voiceless words as well as voiced ones, even over long distances. Although

dragons can learn to reproduce voiced and unvoiced consonants to replicate the speech of the

younger races, they do not make use of this membrane to make the b, d, th, g and other voiced

consonants, instead using membranes in their nasal passages to slightly hum the sound with a faint

nasal quality that gives them a slight accent if they are not adept at it.

These distinctions are part of the Northern Latitudinal dialect spoken by Bloody Face. Other

dialects of draconic apparently include long/short vowel distinctions (primarily in the older and Oceanic

forms), fricatives such as ç (which Howard describes as a “rolled s”) in the most ancient form of the

language, affricates such as qš, qw, qł and qç as well as a mw sound in most Oceanic languages, such as the

word for humans, qs’mwêhuñ or “the boat people.”

2.2. A Note on the Orthography of this Paper

“Orthography” is a technical term which simply means “How something is written.” Davis’

methodology was precise and professional but his orthographic system seemed to change several times

throughout the years and thus was not very systematic at all. I began working with Srínawésin primarily

because I discovered his re-re-revised orthographic system, which he began to use relatively late during his

work. In order to simplify the writing of this paper, and to keep anyone from wasting their time, I have

systemized his orthography, removing some of the more archaic symbols he used (some of which he was

really fond of) and replacing them with more “common” symbols. The removed or revised symbols

include:

Original

æ

ą

ę

į

ų

þ

lh

This Paper

ae

a

e

i

u

th

ł

Original

ß

ċ

ś

j

ĵ

χ

ş

This Paper

š

ch

x

ý

y

h

sh

Interestingly, Davis preferred to mark unvoiced vowels while leaving the voiced varieties unmarked.

I have reversed this notation, indicating the voiced vowels as á, é, í, and ú while leaving the unvoiced forms

unmarked. I believe this is a better representation of the way these vowels are thought of by their speakers

as being ‘naturally unvoiced,’ in keeping with the general unvoiced tendency of the language as a whole.

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

In this paper, certain things are expressed in the orthography which are not really differentiated in

the spoken language. This is similar to the English difference between their, they’re and there, all of which

are spoken identically but which are written differently because they function differently within a

sentence. There are certain contractions which take place in Srínawésin which I choose to represent in the

written form (although Davis did not) to help the learner as well as to keep grammatical conditions clear.

For instance the English translation of the phrase ‘I sleep’ would be written and pronounced as below:

Davis’ Original Orthography

Orthographic Presentation

Pronounced Form

[tsįtsęją-n]

[tsitseya’n]

/tsitseyan/

These variations mostly occur in the contractions of evidential sentence enclitics such as in the

example above and those in 2.8. Deletion of Repeated Final and Non-Final Syllables.

2.3. Vowels

As noted above, vowels are divided up into two groups, unvoiced and voiced and distinctions between

the two do form minimal pairs, differentiating the root hawa- “female goat” from hawá- “meat.” Davis,

half-jokingly says that this difference is vital not only to speaking correctly, but to not insulting the listener

and thus having your face ripped off.

a

á

i

í

e

é

u

ú

This vowel is pronounced basically like the English vowel in “father” although it is unvoiced with a

sort of whispered, breathy quality to it, pronouncing the sound without vibrating the vocal chords.

In the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) it would be represented as /ạ/.

This vowel is pronounced exactly like “father,” including voicing, and to a dragon it is as distinct

from the a as p and b are to English speakers. In IPA it is /a/.

Pronounced as in English “machine” or “see” but with a breathy, unvoiced quality, sometimes with a

slight palatalization forming a y sound. In IPA is /ị/.

Voiced version of i, pronounced exactly as in “machine” or “see”. In IPA it is /i/.

Pronounced as in English “bet” but with breathy, unvoiced quality. In IPA it is /ẹ/.

Voiced version of e, pronounced as in English “bet”. In IPA it is /e/.

Pronounced as in English “boot” but with breathy, unvoiced quality. In IPA it is /ụ/.

Voiced version of e, pronounced as in English “boot”. In IPA it is /u/.

Noticeably the phoneme /o/ is absent from this dialect. I know of no physical or biological reason

for this phoneme to be left out as other dialects include it, but Davis notes that the Northern Latitudinal

dialect apparently changed all the o/ó sounds to a/á at least fifty draconic generations ago.

2.4. Semi-Vowels

There are several sounds that while originally being vowels are altered in a particular way to form a

sort of semi-vowel, usually through vowel assimilation as detailed in 2.6.2. Vowel Assimilation below.

They maintain an unvoiced/voiced distinction as with all vowels but tend to alter the pronunciation of the

proceeding sound rather then form a wholly distinct sound of their own.

y

ý

This orthographic symbol is close to an i or y sound but represents a palatalization of the preceding

sound (much like giving it a y quality). In IPA it would be represented by /ỵ/ and for instance the

word Tsyenrisa’n would be represented as /tsỵẹṇṛịsạṇ/. Another common usage are sounds such as sy

/sy/ and xy /∫y/.

A voiced version of the above y sound pronounced the same but voiced. In IPA it is /y/.

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

w

w

This sound is similar to the y sound but gives a rounded-lip quality to the preceding sound. It is

important that this is the way a human would articulate it, but the Shúna do not actually round their

lips to achieve this quality. In IPA it is /ẉ/, therefore [sw] would be pronounced as /sẉ/ and [xw]

would be pronounced as /∫ẉ/.

This sound is the voiced equivalent of the simple w semi-vowel although voicing distinctions are

not shown in the orthography. In IPA it is /w/.

2.5. Consonants

The consonantal inventory of the Dragon Tongue is somewhat easier then the vowels, as all are

unvoiced. Several sounds are extremely difficult to produce and in fact it might be physically impossible

for humans to reproduce them, however the method for pronouncing the nearest possible approximate

sounds are given below.

h

ł

s

š

x

sh

th

Sibilants

Pronounced as in the name “Harry” but with a slightly more breathy expulsion of air. Sometimes,

in excited or angry speech it is pronounced more as a ch sound as in Welsh chwarae ‘game’ or

German’s Bach. In IPA it is /h/and sometimes as /χ/.

A “lisped l” sound somewhat like the Welsh pronunciation of certain l-sounds (orthographically

represented in Welsh as ‘ll’). But, unlike the Welsh pronunciation, the sides of the mouth are tensed

much tighter, the lips are opened more and more air is allowed to spill out with a greater hissing

quality. This sound can be pronounced by humans by placing the tip of the tongue in the same place

as one would if they were producing the normal ‘l’ sound but allowing the air to spill out from either

side of the tongue with a pronounced hissing sound. This sound is classed as part of the sibilant

sounds, s, š, x and so on. In IPA it would be written as /łs/as opposed to the usual Welsh sound /ł/.

This sound is pronounced as the English sound in “soon,” although it tends to be held slightly longer

than in standard English pronunciation. Long enough to be noticeable although not as long as the š.

In IPA it is /s/.

The long version of ‘s’ it is pronounced as above but approximately twice as long, making a drawn

out, hissing sound as when someone is hissing the word “yessss” unpleasantly. It is better to hold it

overlong then to make it too short and confuse it with the short s. This is a minimal pair with s and

is not a geminate sound; it is truly a long, hissed ‘s’. In IPA it is /s:/.

Pronounced as in the English “shade” although sometimes with a slightly longer quality to it. The

long and short versions do not form a minimal pair. I have borrowed the convention of writing x to

represent the ‘sh’ sound from the classical Spanish orthographies of Mesoamerican languages and

some Chinese Romanized alphabets. In IPA this sound is /∫/.

This sound is not the same as the ‘sh’ in English (see the x sound above) but is pronounced as it is

written as an ‘s’ sound with an ‘h’ following. This sound is similar to an affricate in that there is one

sound with a release of another sound pronounced in almost the same moment, but as both of these

sounds are sibilants it is better to think of this sound as an emphatic, breathy ‘s.’ Thus, a word such

as shiwasu ‘algae’ is pronounced as ‘s-hee—wah—soo’ with all the vowels and consonants unvoiced.

In IPA it would be written as /sh/.

This strange sound is written with the common English digraph ‘th’ although it is pronounced with

a slightly lisped and harsh quality rather then the standard English pronunciation. Although this

sound can be replicated by simply articulating it as ‘th’ it sounds foreign and strange to the Shúna,

and the most authentic way of pronouncing this sounds as to articulate it as if you suffered from a

lisp, even exaggerating it if need be. It is interesting to note that the standard English pronunciation

sounds as if the speaker has a lisp to one of the Shúna while the correct pronunciation sounds like a

lisp to English speakers! In IPA (the International Phonetic Alphabet) it would be best represented

as /θs/.

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

Affricates

ch

qs

qx

ts

n

r

w

y

This sound does not occur naturally in Srínawésin as a separate phoneme but is rather a contraction

of two sounds, usually x and ts, discussed below in 2.6.1. Consonant Assimilation. Although it is not

a separate phoneme, it is basically pronounced as in the English word “such” although sometimes is

drawn out slightly longer then the standard pronunciation. In IPA it is /t∫/.

Very similar to the English sound as in “fox” but this sound is a true affricate in Srínawésin and can

come at the beginning of words such as qsánir ‘moon’. The q part of the affricate tends to be

pronounced farther back in the throat (when humans replicate it), similar to the uvular q in Iñuit or

Arabic languages. In IPA it is /qs/ sometimes with a slightly lengthened sound as in /qs:/

represented as qš in the orthography although qs and qš do not form a minimal pair and represent an

assimilation of two sounds.

This sound is difficult for many humans. Similar to the sound in the word “action” this sound is

essentially a ‘ksh’ sound but is a true affricate and can come at the beginning, middle or end of word

such as the root qxeqxí- ‘fern’ pronounced as “ksheh-kshee.” The q is pronounced similarly to the

sound noted in qs above. In IPA it is /q∫/. This sound appears to be similar to the initial sound of

the Sanskrit name “Kśemendra.”

This affricate is pronounced as in the Japanese “Tsunami” or in the English “its” but is a true

affricate and can come at the beginning of a sound such as tsúhú- ‘darkness’. In IPA it is /ts/.

Nasals, Liquids and Semi-Vowels

An unvoiced version of n as in the English pronunciation of “no” but with a breathy, voiceless

quality. In IPA it is /ṇ/. Very rarely this sound is pronounced as ng although there seems to be no

pattern to the n vs. ng pronunciation that Davis could discern, thus he believed that these are simply

allophones of one another. The only draconic speaker Davis repeatedly notes used a ng-

pronunciation was the female Moonchild so it is possible this is a female speech pattern only, or

might be simply an accent of this individual or even a speech impediment but I have almost no

evidence for any supposition.

This sound roughly corresponds to a rolled or trilled ‘r’ as in the Spanish pronunciation of “pero” or

some Scottish/English pronunciations of the ‘r’. Sometimes with a slight growling quality as in the

French pronunciation of “Paris,” however in all cases it is unvoiced. This sound is usually

pronounced by dragons with a slight purring sound which cannot be exactly duplicated by humans

perfectly and therefore can only be approximated as above. In IPA it is / /.

A simple, unvoiced version of the English sound “when” or “what” when pronounced as older people

tend to do. This is the only “bilabial” sound in the Dragon Tongue although dragons do not possess

lips in the way humans do, thus do not make use of these anatomical features in pronunciation. In

IPA it is /ẉ/.

An unvoiced version of the English word “yet” with a breathy, whispered quality. In IPA it is /ỵ/.

2.6. Phonology

Phonology is the discipline of understanding not just the individual sounds that comprise a

language, but the way in which they are put together and how they influence one another. An example is

how the ‘s’ in both bugs and dogs are pronounced in normal English speech as /z/ and not as [s] as they are

written. Despite the difference in pronunciation, English speakers understand that these sounds are the

same as the ‘s’ in cats, if they even realize they pronounced them differently at all. The complexities of

pronunciation are—thankfully—somewhat eased by the fact that sounds in the Dragon Tongue have only a

general influence on one another during normal speech, but it is important to note that assimilation only

occurs within a word when the various affixes are applied to the roots to make meaningful words, not between

two different words.

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

2.6.1. Consonant Assimilation

The main rule of consonant assimilation is:

(1)

(Consonant A) + (ConsonantA2) = (Consonant A)

Essentially this means that if a sound such as qx is placed next to another of the same (qx in

this case) within a word the two sounds combine to produce a single sound, i.e. a single qx. An

example is found in the first word of the sentence:

Sawqxítsúts anneqsánisyáhur łaxáxéhášér aQsánir sa Qxéyéš’n.

Moonchild spoke to the bright moon in the unreachable heavens above.

The first word Sawqxítsúts is comprised of the root qxítsú- ‘to speak to’ along with several

affixes including the infix –uqx- denoting the object of the verb. Instead of *Sawqxqxítsúts2 the two

‘qx’ sounds are combined, thus forming the proper form: sawqxítsúts.

Another rule is similar:

(2)

(Consonants s, š, x) + (Consonants s, š, x) = š

In other words, if any of the sibilants s, š, or x come in contact with the sibilants s, š or x then

they assimilate, turning into the long š sound. This holds true even if the initial ‘s’ is part of an

affricate such as ts or qs becoming tš and qš respectively, although neither of these two sounds form

minimal pairs with their shorter sisters but instead represent assimilation. The exception to this is

when x and x come in contact, detailed below. Additional rules follow the same model:

(3)

(Consonants qs, qx) + (Consonants x, s, š) = qš

(4)

(Consonant ts) + (Consonants s, š) = tš

There are three exceptions to these overarching rules:

(5)

(Consonant x) + (Consonant x) = x

(6)

(Consonant qx) + (Consonant x) = qx

(7)

(Consonant ts) + (Consonant x) = ch

Pronounced with the long ‘s’ but is

not a minimal pair with the shorter

‘qs’

Pronounced with the long ‘s’ but is

not a minimal pair with the shorter

‘ts’

Rule 1) seems to take precedence

here rather then Rule 2)

And not qš with the same reasons

as above

This contraction only occurs then the ts occurs first and the x afterwards, not the reverse and

usually only applies within a single word. However, when the evidential question words xi/xa/xu

follows the Class I Subject ending –ets it often contracts to –ech as an exception of this rule. This is

2 Or a geminate consonant replicating the sound pronounced as /

s

∫q∫

s/ or “sawqsh-qshee-tsoots”

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

further discussed in section 7.3. Evidential Sentence Enclitics below. One final “rule” is how the

syllable wu is treated by Srínawésin’s speakers. I say “rule” because unlike most of the other

consonant assimilations presented above there is no universal method of treating this sound and the

way speakers treat this sound varies somewhat from individual to individual. Essentially, however,

there appears to be a tendency among the Northern Latitudinal Dialect speakers’ towards a definite

dislike of the sound wu, not only in verb roots themselves but also on the rare occasions when the

combination of w+u appears due to morphological conditions such as the addition of affixes to a verb

root, the inflection of a prefix according to tense or other factors.

In fact, the syllable wu only appears once in a verb root in all of Davis’ notes in the word

qsłáwu- or ‘a forest with a great variety of mixed trees.’ I have no evidence for this belief and Davis

himself never remarks on this disparity (at least in the notes I have access to) but I would

hypothesize that since most forests have a large variety of trees in one way or another that the root

qsłáwu- is a rather common word to be used in describing forests and might therefore represent a

form of archaism or holdout from a period of time before the Northern Latitudinal Dialect

developed a dislike of the sound wu and began to alter its pronunciation. This is similar to how in

English irregular and archaic word patterns such as am, are, were, be and so forth tend to be

maintained because they are used so much (the dropping of the form thou art is relatively recent in

English’ history). There is some evidence for this hypothesis as on the rare occasions where this

syllable appears in Davis’ notes it is almost always when he was recording “archaic” speech patterns

either spoken by very old dragons or by a younger dragon attempting to replicate what an older

dragon might sound like for Always Scratching at Something’s benefit or in other varieties of

Srínawésin such as the Arctic Latitudinal, which appears to retain the use of the wu syllable.

Despite these variations, one thing is very clear from Davis’ notes. Many, if not most of the

Northern Latitudinal Dialect’s speakers dislike the sound wu and when it appears will alter the

sounds therein to a more “pleasing” sound (Star Gazer’s term, not mine). I would guess the reason

for the dislike of this syllable is that the two sounds which comprise it /w/ and /u/ are not just

similar to a dragon’s speech apparatus but they are pronounced virtually identically. The

combination of a w and u would therefore fall under both the consonant assimilation rule (1) above

and the vowel assimilation rule (4) below, both of which simply state that when two identical

sounds appear next to one another they assimilate into one sound. Normally this would be a simple

task, but often the phoneme w contains vital grammatical information as it is invariably part of a

grammatical prefix or suffix and the phoneme u almost always an indicator of the Cyclical Tense

when combined in these forms and thus carries grammatical and semantic burden as well, so simply

combining them would reduce the information required in the sentence.

So if simply combining the sounds cannot be done, what then do the language’s speakers do

with this undesirable sound? This problem is not one which has found a universal solution by

draconic speakers in Davis’ notes but there are two general strategies employed by the language’s

speakers. 1) if the wu syllable is absolutely essential for understanding—usually in a short, clipped

sentence of only a word or two when the rest of the affixes of the sentence are not available to

provide the necessary information—the syllable wu is unchanged and left on. 2) if the rest of the

sentence has the various affixes which provide the necessary tense information which would usually

be carried by the /u/ phoneme, the u sound is simply deleted entirely and ignored even though it

would usually be required. However, when this occurs the /w/ phoneme is invariably voiced to

compensate and indicate the deletion of the /u/ sound although in this font it is not usually

indicated. For instance, the exchange:

Saqsániwéha asa ixíxéwárá sa síthrarésu irúnárahawéha nisa narúsa saxésits qxáxéłusaha nasa’x,

xiXíhúréš?

Xax? Wúx, xiRihu sa Sayaxhú!

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

Have those large mountains over by the wide open ocean changed much since you last flew

to them, Dribbler?

What did you say? They are probably always (changing) in cycles, Little Friend!

The term wúx in this exchange is part of a short, clipped phrase which has no other affixes in

order to indicate the tense which the speaker intends to convey so in this instance the wú syllable is

left unchanged as noted above. However, in the sentence below:

Wtsithí sa xinhaxłárésin urúrín sa nunashusurésin huła

I hear that the cold, icy winds are always eroding (the mountains) over the ages

In this instance, the verb wtsithí sa xinhaxłárésin “(the innumerable winds) are always eroding

(the innumerable mountains) in geologic time” would appear as Wutsithí sa xinhaxłárésin but since

the Cyclical Tense is indicated by various other inflections of affixes throughout the sentence the

“unpleasant” wu syllable beginning the verb is modified by simply deleting the /u/ phoneme leaving

the /w/ phoneme alone. This is primarily a orthographic convention on my part to aid in

understanding, it would probably be more accurate to write útsithí sa xinhaxłárésin as the [wts]

beginning the verb is pronounced identically to /uts/ but for the purposes of a beginner—and

something of an expert in my case!—it is easier to write the [w] to indicate the “geologic timescale”

prefix which is attached to the verbal root. The way verbs are put together and arraigned will be

treated in further sections but for now it is enough to note that these constructions exist although on

several occasions Davis noted that a speaker would go through some fairly complex linguistic

acrobatics in order to avoid the “unpleasant sounding” wu sound when a more straightforward

approach which entailed wu would be much simpler.

2.6.2. Vowel Assimilation

Vowel assimilations are similar to the consonantal forms, but are more complicated and

unfortunately more common. When two vowels are placed together in the Dragon Tongue one of

them always “wins” over the other, replacing it completely, (although there is an important

exception, see 2.6.4. Tense Marker Assimilation below). There are four rules followed when

applying this form of assimilation.

Rule (1)

Voiced (cid:108) Voiceless

This rule means that although one of the vowels will replace the other completely, it will

assimilate with the voiced/unvoiced quality of the vowel it replaced. If two unvoiced vowels assimilate

then the resulting vowel is also unvoiced but if an unvoiced vowel assimilates with a voiced vowel

result will always be voiced regardless if the voiced vowel is replaced or is the replaced vowel. Thus

an ‘a’ added to a ‘á’ will always result in ‘á.’

Rule (2)

Front (cid:108) non-Fronted

This means that the front vowel ‘i’ will win out over any other vowel which is not fronted (so

called because for humans the ‘i’ is pronounced in the front of the mouth, once again in terms of

human but not necessarily draconic pronunciation). I cannot give the physiological reason for this in

regards to the dragons’ speech apparatus, but I imagine that a similar process is at work. It is

important to note that Rule (1) still applies, thus although an ‘i’ will replace an ‘ú,’ the result will

always be voiced: ‘í.’

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

Rule (3)

High (cid:108) Low

In this case a vowel which is pronounced high in the mouth (i, í, u and ú) will replace one

which is pronounced low in the mouth (a, á, e, and é). ‘E’ will replace ‘a’ as it is pronounced higher

in the mouth then the ‘a’ although it is not technically a true high vowel. Rules (1) and (2) still

apply, thus ‘i’ will win out over ‘ú’ (both are high vowels but ‘i’ is a front vowel while ‘ú’ is a back

vowel) but the result will still be ‘í’ (voiced due to the voicing of the original ‘ú’). These rules can be

written out as below, the various rules determining the results given in superscript:

(e, é, i, í, u, ú) + a = (e, é, i, í, u, ú)3

(e, é, i, í, u, ú) + á = (é, í, ú)1, 2

(i, í) + e, é = (i, í)1, 2, 3

(u, ú) + i, í = (i, í)1, 2

(u, ú) + e, é = (u, ú)1, 3

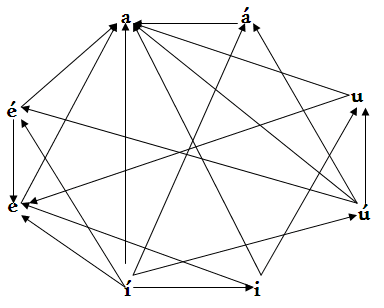

These vowel changes can be represented with the following diagram:

Thus, ‘í’ is the strongest vowel in that nothing will replace it; while ‘a’ is the weakest as even

‘á’ will replace its unvoiced sister. Interestingly, Davis notes that the vowel o/ó is still used in

certain dialects of Srínawésin (primarily in the Arctic varieties) and the rule for vowel assimilation

in these dialects is:

(o, ó) + any other vowel = (a, á)

He believed that this paradigm lead to the reduction and final demise of the o/ó as a separate

phoneme in the Northern Latitudinal Dialect of Srínawésin.

Finally:

Rule (4)

(Vowel A) + (Vowel A2) = (Vowel A)

This rule states that if two vowels of the same kind (including voicing distinctions) come into

contact within the same word they combine and form one vowel of the same type: a + a = a and á + á

= á. They do not produce a long vowel in the Northern Latitudinal dialect of the Dragon Tongue,

instead simply combining into a single sound, although some other dialects do have long vowels

which form in this case.

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

2.6.3. Semi-Vowel Assimilation

There are a few cases when two vowels may come into contact with one another yet not

assimilate, the primary one being dealt with below in 2.6.4. Tense Marker Assimilation. It should

be noted that when this occurs there is a very slight pronunciation alteration to the following

unassimilated vowel. Essentially the following vowel is changed from a full syllabic vowel into a

non-syllabic semi-vowel which alters the quality of the proceeding vowel rather then being

pronounced in full on its own. This distinction deals primarily with the vowels u, ú, i, and í, a/á and

e/é are left largely untouched by this. Semi-Vowel Assimilation is shown below:

a/á+u/ú

a + u = aw

a + ú = áw*

á + u = áw*

á + ú = áw*

e/é+u/ú

e + u = ew

e + ú = éw*

é + u = éw*

é + ú = éw*

a/á+i/í

a + i = ay

a + í = áý

á + i = áý

á + í = áý

e/é+i/í

e + i = ey

e + í = éý

é + i = éý

é + í = éý

* The w in all of these cases is voiced but due to the limitations in this font they are not

represented.

2.6.4. Tense Marker Assimilation

There is one exception to the rules of vowel assimilation. If a vowel that is to be submerged by

the other is part of an affix which is inflected for tense, the only rule which applies is Rule (1), i.e. the

assimilation of unvoiced/voiced vowels. The inflection of affixes for tense is detailed below in 3.5.

Inflection of Affixes, but it is important to note at the moment that the vowel in the verbal prefix

ha- will not combine with an infix which follows it such as –en-, the infix marker for Class I verbs as

in the case below:

Haenšáwéts aSłáya sa Snaréš xárrúnáha na

Bloody Face sometimes saw her/him (another of the Kindred) (as she flew) across the

mountains

Thus, in the word haenšáwéts, which is comprised of the morphemes ha+en+šáwá+ets the root

šáwá- combines with –ets to produce –šáwéts but ha- and –en do not combine to form *hen- as ha- is

inflected for the past tense, therefore immune.

However, in the case of:

Háýnšáwéts aSłáya sa Snaréš xárrúnáha na

Bloody Face saw it (the small prey animal) (as she flew) across the mountains

The word háýnšáwéts is composed of the morphemes ha+ín+šáwá+ets and in this case the

prefix ha- becomes há- due to the voicing of the infix -ín- despite the fact that it is inflected for the

past tense while the infix –ín- becomes the palatalized –ýn- due to the influence of the proceeding

vowel. However, if both the tense-inflected vowel and the original vowel of the root are the same,

they will assimilate with one another under the rules of 1) and 4) from 2.6.2. above:

Hixíłeya’n

(hi+ixí+ŁEYA+Ø) (+’n)

(Periodic Aspect+Class III Plural+HUNT-BY-SCENT+1st Person Null Subject) (Certainly)

Sometimes-I-large animals-hunt-by-scent-alone certainly (lit.)

Sometimes I hunt large animals by scent alone

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

2.7. Consonant Clusters

Consonant clusters are uncommon within verbal roots, the main derivational form of all draconic

words (see 3.3. Derivational Structure below) although consonant clusters do occur during the normal

course of word formation when the various affixes are attached to verbal roots. When affixes are attached

to these verbal roots and this function produces a consonant cluster, it is subjected to the normal forms of

consonant assimilation as noted above in 2.6.1. Consonant Assimilation. Thus the Dragon Tongue does not

disallow consonant clusters entirely although consonant clusters are restricted if they are found at the

beginning or end of a single syllable. Clusters forming across the boundary of two different syllables are

subjected to Consonant Assimilation and are otherwise ignored.

A consonant cluster may begin or end a syllable when:

1)

2)

3)

Consonant 1 is a fricative or is an affricate, i.e. ‘qs, qx, s, x, š, ts’

Consonant 2 is either a nasal or liquid sounds or ‘n, ł, r’

Consonant 2 is a semi-vowel sound such as ‘y, ý’ and ‘w’

Thus the only allowable consonant clusters at the beginning or end of a syllable are: ‘qsn, qxn, sn, xn,

šn, tsn, qsł, qxł, sł, xł, šł, tsł, qsr, qxr, sr, xr, šr, tsr, qsy, qxy, xy, sy, šy, tsy, šw, xw’ and so forth although not all of

these sounds are found with any regularity. The most common consonant clusters at the beginning of a

syllable are overwhelmingly ‘sn, xn, tsn, sł, xł, šł, sy, xy, sw’ and ‘šy’ while the most common cluster found at

the end of a syllable is any of the above sounds with –n appended. This –n attachment, written in this

orthography as –’n, is commonly found when the positive evidentials ni, na and nu are contracted and

attached to the end of a words, see 7.3. Evidential Sentence Enclitics below.

2.8. Deletion of Repeated Final and Non-Final Syllables

In most words in the Dragon Tongue, suffixes are appended to nouns and verbs and in certain cases

this suffix duplicates the final syllable of the root word to which it is attached. For instance:

-hunha+ha

a deep, wide lake which has dried up

In these cases, whether it is a true-verb or a noun-verb, speakers will usually drop the repeated

syllable completely (the proper suffix is simply understood to be there). When this is done the remaining

syllable is voiced. If the syllable is already voiced no further change occurs:

-hunha+ha

(cid:108)

-hunhá (not *hunhaha)

This occurs in almost all cases, but there are two exceptions. If the word immediately following the

noun or verb in question is one of the evidentials (treated in 7.3. Evidential Sentence Enclitics) or the

particle sa, the repeated syllable is not deleted and remains in its full form:

Nahunhaha’x?

At the deep, wide lake that dried up?

The phoneme š is considered to be different then the simple s so there is not final deletion in cases

such as Hiwašinsin’ ‘It periodically smokes.’ Another deletion which takes place in Srínawésin occurs when

the contracted form of an evidential enclitic falls behind a word with the same sound. When this occurs, the

evidential is usually dropped, being understood as being there due to the previous sound. This form is

represented in the orthography as [’], showing that the evidential is still “there” simply not expressed as a

separate sound:

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

Aqxnéhix’?

Tsiqsusésin’

Náqšaráqs’

(contracted form of Aqxnéhix xi?)

(contracted form of Tsiqsusésin ni)

(contracted form of Náqšaráqs qsa)

A human (interrogative subject)?

It is raining

It (aquatic) didn’t come up from

underneath and grab it (another aquatic

thing)

These deletions also occur to non-final syllables, although with much greater rarity. The general rule

for non-final syllable deletion appears to be similar to final syllable deletion, i.e. the repeated syllables are

contracted into one syllable which is then lengthened. For example:

Tsatsaqsáthich? (cid:108) Tsáqsáthich?

Were you/him/her eating it (Class XII Component)

These deletions are extremely rare, and only take place in certain circumstances, usually the

addition of prefixes which repeat the sound of syllable after them. There are three exceptions to this,

however, 1) voiced/unvoiced distinctions do not appear to apply in these cases (if the syllable tsa was

attached to the syllable tsá they will not contract as they are considered to be sufficiently different from one

another). 2) Roots are immune to contraction, i.e. if the attached syllable is the same as the root’s initial

syllable they are not contracted:

Rúrúnáwéha’n (cid:108) *Rúnáwéha’n

Through the mountains

3) Roots with repeated syllables are also immune to any form of contraction (qsáqsá- ‘crow’ never

appears as *qsá-). Finally, in “formal,” polite, poetic speech or in life-threatening situations (which when

dealing with a dragon would definitely necessitate being polite!) the repeated syllables are often left on and

not deleted. This is similar to the way English speakers will tend to use “do not” rather then “don’t” in

formal occasions.

§2.9. Stress

The stress pattern in the Dragon Tongue is extremely regular although due to the fact that the

language differentiates between voiced/unvoiced vowels, it can be difficult to recognize which sound is

stressed and which is not. The stress always falls on the first syllable of the verb root whether it is being

used as a verb, noun-verb or adjective. In those instances when two roots are found within a single word

(such as transitive verbs with infixed objects) the stress falls on the main verbal root not on the infixed

object.

§2.10. The Draconic “Accent”

Although this chapter is primarily about how the Kindred articulate their own languages, how the

Shúna attempt to speak human languages is just as interesting and is just as conditioned by their

physiological characteristics. This section attempts to describe the draconic “accent” while they are

attempting to speak in the human tongue, particularly in English, as the languages Howard heard his

informants speak was overwhelmingly English and Srínawésin.

According to Davis’ notes, the accent a particular Sihá displays ranges from Bloody Face’s nearly

perfect English to Charred Oak and Blue Tongue’s almost unintelligible accent. This range depends upon

several factors: a Sihá’s exposure to the languages of the Younger Races, the amicability of the Sihá-

Qxnéréx interactions and above all the particular dragon’s desire to learn. Dragons such as Frost Song or

Obsidian Claw thought of people as strange barely edible prey-creatures and so never really bothered to

learn the “chattering” of the Younger Races. Bloody Face and Moonchild often dealt with their non-

draconic neighbors (in a mostly but not always semi-friendly way) so they spoke fluently in a variety of

languages with almost no accent whatsoever. On the other hand, some Shúna such as White Eye, Twisted

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

Smoke and Angry Face regarded the Qxnéréx as an abundant and easy food source and not only learned

human languages but could speak them just as well as Bloody Face and Moonchild, albeit with the goal of

deceiving and luring tasty tid-bits closer.

Davis also noted that dragons (if they speak a human language at all) have not all been exposed to—

or cared to learn—English because it simply isn’t relevant to them. White Eye didn’t speak any English

whatsoever but spoke Norwegian, Swedish and Saami quite well, but then again that only made sense

given he was from the Trondheim district of Norway. Dragons living in the Gobi desert will most likely

speak Chinese if they know any human language at all, just as those in Africa would speak Bantu, Xhosa,

Swahili or any of hundreds of other African languages. In addition it appears that certain human languages

are more difficult for dragons to pronounce and articulate because some human languages have more

sounds which do not come easily to the Kindred and some are easier because they contain sounds the Shúna

can more readily pronounce. Lastly, the Shúna live so long the time in which they originally learned a

Qxnéréx language is extremely relevant as well. Although Bloody Face often (read as once or twice in a

century) dealt with his non-draconic neighbors, his last exposure to English had been in the 1600’s so before

he adapted to modern English he constantly said things like:

“Forsooth, Master Howard! Thou cookest thy meat before partaking? My troth!

Dost thou not miss the taste of warm blood in thy seared strip of flesh?”

Needless to say, Howard found a huge crimson dragon speaking in an archaic English accent and

saying things like “Fie upon that fish! It hath escaped me!” rather disturbing. Luckily, it took Bloody Face

only a moon or two of exposure to Howard before he was using a little more up-to-date English.

But no matter how skilled a particular Sihá is with a human language there are certain physiological

characteristics that will always give a dragon a particular accent, just as a human speaking Srínawésin will

never be able to speak the language without a similar accent as neither race can physically form the same

set of sounds as the other. A dragon speaking a human language is forced to employ particular articulation

tricks in order to approximate certain human sounds which they simply cannot reproduce exactly. This is

similar to a ventriloquist reproducing sounds such as ‘p, f, b, m’ and other sounds which require the use of

the lips—without actually moving the lips. A particularly skilled Sihá can reproduce these sounds so well

their accent is virtually impossible to hear although a majority of the Shúna usually retain a fairly strong

accent. Howard also noted that while a Sihá is speaking in English there is a strange disconnect between

the words they are speaking and the motions of their mouth. Most people are at least peripherally aware

(although not usually consciously) of the way a mouth is “supposed” to move when someone is speaking—

particularly with sounds that require the lips—but even when reproducing these sounds the Shúna do not

move their mouth “quite right” because they are approximating human sounds, not forming them as we

would. I would guess it is similar to watching a foreign movie which has dubbed over English dialogue, no

matter how good the dubbing is there will always be instances when the mouth and the sounds it is

supposed to be producing will not quite match up. The difference with watching one of the Kindred speak

is that they are in fact producing the sounds but not doing it in a way which “matches up” with what a

human mouth will look like while making the same sounds. I would also assume that seeing those long,

razor-sharp teeth behind unmoving lips while a dragon is making (or attempting to make) a ‘p’ sound

would be rather disconcerting as well. Davis noted that he never corrected a dragon when they made a

mistake in English and I would venture to say anyone who would never like the pleasure of seeing their

intestines all over the ground would probably do well to do the same.

Shúna have three main areas of difficulty while reproducing the languages of the Younger Races:

Labial Sounds: These sounds are produced with the lips and include phonemes such as /p, b, f, v, w,

m/ and so forth. Dragons do not possess the same degree of articulation control over their

lips as humans do, so they—for the purposes of language—do not have lips to make these

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

sounds. The one exception is the ‘w’ sound, which is found in their own language and which

they apparently make by slightly curling back their tongue while producing a /u/ sound to

create the quality of the /w/ which humans make by rounding our lips. Dragons can

replicate human labial sounds in a similar manner—by manipulating the back of the tongue

to approximate sounds such as /w, m/ and /v/. Davis also theorized that they placed the

back of their tongue against the top of their throat and releasing it to create labial stop sounds

such as /p/ and /b/ although with a great deal of difficulty. Howard noted that the way the

/f/ sound was created was much more transparent, this sound was created by releasing the

air in their mouths over their tongues while slightly sticking their tongues out from their

mouths, essentially making it look like the dragon was half-way between sticking its tongue

out at him or making a raspberry. I would suggest no one laughs if they see a dragon make a

/f/ sound. Even a skilled speaker has difficulty achieving these sounds because a Sihá must

force the air in their lungs through their nasal passages rather then through their mouths for

all the labial sounds except for /f/, giving all labial sounds a slightly thick or nasalized

quality to them.

Voiced Consonants: As noted in 2.1 Overview above, “voiced” sounds are articulated by the Shúna

through the vibration of a membrane deep within their chest as opposed to the vibration of

vocal chords as humans do. This membrane is easily used with an open air passage but less

so when the passage is restricted such as when making consonantal sounds. This means that

voiced-unvoiced differentiation is much easier to apply to vowels rather then consonants,

even the voiced versions of phonemes the Kindred commonly use (such as /z/, the voiced

variant of /s/). Therefore, the Shúna have great difficulty producing any sort of voiced

consonantal sounds such as /b, d, g, v, ð, j/ and so on. When a skilled speaker attempts to

reproduce these sounds, Davis noted that the easiest way to do this is by forcing the air

partially through the nasal cavity, allowing the nasal vibration to take the place of a vocal

vibration. This gives “voiced” consonants a highly nasal quality similar to they way ‘labial’

draconic sounds are produced although the strength of the nasal quality depends on the skill

of the speaker.

Stop Consonants: The Shúna dislike “stop” sounds, apparently believing them to sound “chirpy,

abrupt” and “choppy”—according to Tear of the Sun—and have a great deal of difficulty

recreating stop sounds such as /t, d, k, g, p, b/ and so on. While attempting to speak a

human language (which always have a variety of stop consonants which is partially the

reason we are referred to as qxnéhiréx “chatterers”) a Sihá typically pronounces these sounds

similarly to the ‘ts, qx’ and ‘qs’ sounds, releasing the consonants with a slight sibilant sound

following it, making it a semi-affricate. With a particularly thick accent this will sound like

“I dso nots see while its is so hards for you tso eats raw flesh!” The strength of the sibilant release

ranges from strong to almost imperceptible but Davis noted it was always present even if it

was very difficult to hear.

These difficulties are cumulative, so a voiced bilabial stop such as /b/ is terribly difficult for a Sihá to

pronounce correctly and requires a variety of articulation tricks to produce. This is similar to a human

trying to make a /b/ sound without using their lips and attempting to make an /r/ sound at the same time.

Davis noted that the ability to create stop sounds come easiest to the Shúna and the ability to repress the

sibilant release comes fairly soon after that if they have enough exposure to humans and if they care at all

to try that hard. If someone can’t understand what they are trying to say simply eating them is a perfectly

viable alternative. But the nasalized voiced consonants and the difficulty replicating labial sounds are

much more difficult to overcome. He noted (with some well-concealed humor in the presence of his

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

informants) that unskilled draconic speakers of English tended to voice everything (a relatively common

tendency given the draconic belief that our languages sound “buzzing”) or devoiced everything, relying on

Davis to simply fill in the gaps if they were not pronouncing what they were saying correctly. This lead to

some horribly accented sentences such as:

“I do nod zee wad thy divviguldy iz! Hov vaz I do no thy glothes vere vlammable?”

(Spoken by Blue Tongue who not only voiced everything but spoke in archaic English!)

“Ha! Ash Tonkue sait you akset too many questions, XiXútsithí sa Qséxúnáx’hú! I’m

surpriset he titn’t kill you when you came to speak with him!” (Spoken by Dribbler, who

devoiced everything. The sounds such as ‘m, n, w, r’ and so on were also unvoiced.)

Finally, many dragons have a tendency to pronounce human sounds as if they were Srínawésin

sounds. Even Moonchild and Bloody Face had a tendency to do this when they were excited or on edge but

it was particularly strong with dragons such as Charred Oak, Rotten Teeth and Dawnglow. The typical

pronunciation of human sounds as draconic sounds is given below:

Human Phoneme

s

h

z

m

l

th

r

Draconic Pronunciation

/s:/

/χ/ Sometimes but not always

/s/ or /s:/

/n/ Sometimes but not always

/ł/

/θs/ Like a human with a lisp

/r/ “Rolled” like the Scottish English dialect

There are exceptions to all of these tendencies and all dragons are first and foremost individuals and

must be treated as such. I would suggest that if you ever have any interactions with a Sihá that you not

assume that it cannot speak any language you can speak and even if they cannot they are exceptionally

skilled at reading body language and along with their ability to hear heartbeats and a sense of smell that

rivals the greatest bloodhounds they are fully capable of knowing when someone is lying even if they cannot

understand the language that person is speaking at the time. I would also like to thank Howard Davis once again

for the information in this section. Taking a close look inside the mouths of possibly less-then-patient

dragons cannot have been very much fun.

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

Section III:

Morphology

3.1. Overview

Morphology is the way in which words are formed by various smaller units of meaning—called

morphemes—to make a meaningful word. For instance, the English word cat is singular and an English

speaker will understand this and know that to make it plural an –s must be attached to cat thus forming cats.

This is a fairly simple case as opposed to the plural form of man isn’t *mans but men. Complex

morphological forms in English include the use of the morpheme un- on certain verbs such as un+clog to

form the complex verb ‘unclog’ and the famous linguistic example of ‘antidisestablishmentarianism’ which

is found in almost every linguistics textbook dealing with morphology and is composed of a total of five

morphemes attached to a single root (anti+dis+ESTABLISH+ment+ary+an+ism). All human languages range

from the morphologically complex to relatively simple. On the complex side, Iñupiaq Eskimo and the

Peruvian Quechua languages:

Iñuqaqsaaginiaqtugut3

We intend to have people over in the future

Aparichimpullawaychehña!4

Please bring it to me right away (to more then one person)!

These two languages are agglunative or morphologically complex in nature, whereby roots have

various affixes attached to them in a predictable manner to form complex words, many of which can stand

for entire sentences in English. English, on the other hand, is relatively simple, each word in the above

example comprised of simple parts mostly without suffixes or prefixes (which do occur but with much,

much more rarely). Sometimes English is classified as an isolating language although a better example of

isolating languages would be Japanese, which relies on particles (separate words from the word they modify

such as English prepositions to, in, at etc.) to define the grammatical place of the word along with a few

suffixes attached to primarily verbs to denote past/present tense and so on:

Anata ga inu o shibafu ni mimasu ka?

Do you see the dog on the lawn?

Inflecting languages such as Old Irish or Latin are somewhat more complex then English, having a

few prefixes attached to some words but denoting grammatical meanings by a pattern of inflections of

specific word classes such as:

Téit ass íarum 7 a scíath slissen laiss 7 a bunsach 7 a lorg ánae 7 a líathróit5

Then he goes away, and his shield of boards with him, and his toy javelin and his driving stick and

his ball

Galba cum Lesbiâ in casâ parvâ habitat

Lesbia lives with Galba in a little cottage

3 From North Slope Iñupiaq Grammar: First Year, Third Edition Revised, Edna Ahgeak MacLean

4 From Introduction to Quechua: Language of the Andes, 2nd Edition, Judith Noble, Jaime Lacasa

5 This sentence is from the famous Irish story the Táin bó Cúailnge where the hero Cú Chulainn leaves his home to join the

boytroop of Emain Macha. The symbol ‘7’ is an Old Irish convention which stands for the word ocus ‘and’ and works similarly

to today’s ‘&.’

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

In the Old Irish case, téit ‘to go’ is an inflected verb meaning ‘he goes’ combining the 3rd Person ‘he’

with the present sense of the verb vs. ‘went.’ The various nouns in the sentence (scíath slissen laiss ‘board

made of shields,’ bunsach ‘toy javelin,’ lord ánae ‘driving stick’ and líathróit ‘ball’) are all inflected to show

their case (or the way in which they participate as actors in the sentence) as are the various nouns in the

Latin sentence, for instance the proper noun Galba is in the nominative case and so forth. These

morphological distinctions are important because, as you might have noticed from some of the examples in

Section II that Srínawésin is a highly agglunative language, adding multiple prefixes, infixes and suffixes

onto word roots to form various grammatical relationships and meaningful words. This leads to an

utterance which would in English be a full sentence while in the Dragon Tongue is a single word such as:

Náłírátháhéts nan!

He/she (another dragon) overwhelmed my enemy suddenly!

Generally speaking an affix (a prefix, infix or suffix) morpheme is added to the root morpheme

which serves as the core of the new complex word such as:

qsáni- (to change) + -ar (Class VII reflexive ending) = qsánir “the moon” (literally “it-changes-

itself”)

Or phrases such as:

sihá- (to be alike) + -éš (Class I reflexive ending) = sihéš “a dragon” (lit. “it-is-kindred-to itself”)

More complex forms are possible as in the case of plural forms:

qxénra- + -wé- (plural) + -in (Class V refl.) = qxénrawín “narwhal whales” (lit. they-are-narwhals-to

themselves)

And these new complex multi-morphemic words can then serve as the root of even more complex

constructions as further affixes can be added to elaborate and specify grammatical meaning:

łaxa- (past tense locative) + sihéš = łaxasihéš “the dragon (flying) overhead”

Or the addition of other verbal roots which serve as adjectival modifiers and noun prefixes to denote

a vocative quality:

xi- (vocative) + -łaxa + xé + wášá- + -qsáni- + -ré- + -ar = Xiłaxáxéwášáqsánirér! “O, innumerable

changing stars that were flying so far overhead!”

Thus, draconic words are built up by the addition of the various prefixes, infixes and suffixes onto

root forms, which then in turn can form the root of complex words by the addition of further affixes to the

complex root. Although this appears somewhat complicated, the ways in which these utterances are

constructed are extremely regular and once the pattern is understood it does not look quite as daunting as at

first blush it does. It is vital to remember that almost all draconic words (with almost no exceptions) are

formed of at least two separate morphemes. Thus a root is almost never heard spoken alone such as *sihá

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

“dragon” but except for a very few instances it will always be comprised of a root with at least one affix

appended: sihéš ‘a dragon.’6

These additions of the various affixes to the root word are governed by the phonological vowel

assimilation system detailed above in 2.6.1. through 2.6.4. above, thus when the root sihá- is appended with

the Class I reflexive ending –éš, the final ‘a’ is assimilated into the more robust ‘é’ vowel and the result is

sihéš ‘dragon.’ In the case of the root tsáhu- ‘(my) mother’ appended with the suffix –éš the more robust of

the two vowels is the final ‘u’ of the root and thus the vowel in –éš is assimilated into it but the resulting ‘u’

is voiced due to the influence of the voiced vowel in the suffix: tsáhúš ‘she is my mother.’

3.2. Root Forms

Srínawésin, like all languages, has rules on the various phonemes which can appear in relation to

one another, the order in which they may appear and what syllabic structure can comprise a verb-root. For

instance, in English the greatest number of consonants which can typically begin a word is three and they

are usually spl or spr such as splash or spring. Russian and many Slavic languages have different rules which

allow such names as Dmitri where in English the consonant cluster dm is not allowed to begin a syllable but

may come in contact between syllables such as in madmen. By far the most common root forms in the

Dragon Tongue are CVCV-, or consonant—vowel—consonant—vowel. These roots are always composed

of two syllables: CV-CV-. Examples include:

Sihá- (si-há)

Súná- (sú-ná)

Háqsa- (há-qsa)

Xítsa- (xí-tsa)

“to be alike”

“to interfere, to bother”

“to smell like a female deer”

“to change with the seasons”

It is important to note in the latter two cases that as qs and ts are affricates and thus regarded as a

single consonant these roots still maintain the CV-CV- form and are pronounced as indicated, há-qsa and

xí-tsa. These type of forms are never pronounced as CVC-V, or *sún-a or *háqs-a. There are exceptions to

the root structure, primarily falling into two categories: consonant clusters beginning a syllable (CCV-CV)

and two consonants inclosing a single vowel in either of the two syllables of a root (CVC-CV or CV-

CVC). Examples of the first type include words such as:

Sneyé- (sne-yé)

Qsłášu- (qsłá-šu)

“to mark out a boundary, to separate”

“to be (your) neighbor”

(CCV-CV)

(CCV-CV)

Once again, the sound represented by qs is regarded as a single sound and not two thus it obeys the

form given above. Examples of the second type occur in such words as:

Šerná- (šer-ná)

Husún- (hu-sún)

“to be strong, to make strong”

“to scheme against, to plot”

(CVC-CV)

(CVC-CV)

A slightly rarer form is when the standard use of the word tends to leave off the final syllable of the

root such as:

Qxné(hi-) (qxné-)

Xna(qsé-) (xna-)

“to insult by talking like a child to…”

“to crawl, to creep”

6 In this paper the use of ‘Shúna’ and ‘Sihá’ conform to standard English usage, appearing without the usual suffixes; ordinarily

they would appear as –shúnéš and –sihéš.

There is at least one word in Davis’ dictionaries which has a root form of (CCVC-CV):

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

Snarhé- (snar-hé)

“a saltwater iceberg”

(CCVC-CV)

This form is only attested once so I am not sure how often this form appears but it seems to be quite

rare. A slightly less rare form of roots is the vowel-initial root forms (V-CVC) such as:

Ítsin- (í-tsin-)

Úrun- (ú-run-)

Úsun- (ú-sun-)

“a ravine with steep sides”

“blue, blue sky”

“some, something, general thing”

The vowel-initial roots are extremely rare and Davis notes that sometimes they are spoken by older

dragons with an initial y- and with the first vowel unvoiced (so the examples above would be yitsin-, yurun-

and yusun-). He postulates that for various reasons the initial y- has been dropped and the now-initial

vowel becomes voiced to compensate, rendering the forms above. In all the vowel-initial roots he

discovered the first vowel was always voiced, most likely due to this process. He specifies that this is only a

hypothesis however, as he could never speak with very many truly ancient dragons. All of the above verb-

root-forms appear to hold true for all the Latitudinal dialects of the Dragon Tongue although Davis could

not give very good information on any of the other draconic languages he had little or no contact with.

3.3. Derivational Structure

As noted in 1.3.1. Particularities of the Dragon Tongue, all roots are inherently verbal and thus can take

verbal endings. Thus, the root sihá- means “to be alike” and forms the base of the “noun” Sihéš “a dragon”

or “one who is alike (to me).” Aspects of the verbality of all roots are given below in 4.1. Verb Overview

but for now it suffices to say that all roots are essentially verbs even if they used as what we would call

“nouns.” Exceptions to this are particles such as the productive particle sa as well as disjunctive sentence

modifiers which translate into English as and, but, so, if and so on.

How can a language have only verbs? Aren’t nouns required? Root forms are certainly used in a way

we would understand as a noun, such as subjects, objects, locations and so forth, but these same words can

also stand alone as an entire phrase having a quasi-noun/verb meaning such as:

Bloody Face: Háqseqsáthits náqxíxináqx’?

What did you usually eat here in this part of your territory?

Moonchild: Annehawawéx’n.

(I usually ate) female goats.

Verb roots serve as the basis of the many words derived from the root, all with related meanings

(These are related to their draconic speakers although sometimes they seem to be strange associations to

us). For instance, the verb root tsitsí- ‘to warm’ is a particularly productive root. When used as an

intransitive verb it means ‘is warm,’ while when used as a transitive verb it means ‘to make warm,’ or in a

reflexive sense ‘to make oneself warm.’ Additionally it can be used in an adjectival sense (which is very

similar to the intransitive usage) ‘is warm,’ and it may be used adverbially with the meaning ‘hotly, warmly,

angrily.’ When used as a noun-verb the meaning of the root tsitsí- depends on what class it is used with. If

placed under Class VII, or ‘celestial object’ it becomes tsitsír ‘the sun,’ while if used in Class VIII or ‘aerial

phenomena’ it becomes tsitsísin or ‘a year’ as in the yearly cycle of cold to warm and then back again. It can

also be used in Class XII or ‘parts of a larger whole’ to become tsitsíqx ‘a day’ as in a unit of the larger cycle

of the year. Derivations of tsitsí- include:

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

Intransitive Verb: Tsitsitsíha išawaha’n

Transitive Verb:

Reflexive Verb:

Adj.

Adv.

Noun

Saentsitsíts iQsánir sa Qxéyéš’n

Tsitsitsí’n

Xitsitsí sa qxéhasu’hú

Satsitsí sa enqxítsúts ahaséš’łá

the stone is warm

Moonchild makes him/her/you angry/warm

I am warm (to myself)

O, warm fire!

I heard she/he spoke angrily to you/her/him

Class VII

Class VIII

Class IX

Class XII

-tsitsír

-tsitsísin

-tsitsísu

-tsitsíqx

the sun

a year

warmth (from a fire), hot air, heat

(one) day

Thus, the root serves as the basis of all these derivations and although all these words share the same

general meaning as the root itself, the specific meaning of the derived form is based on the various affixes

which accompany it to show how the speaker intends the word to be understood both in terms of semantics

as well as grammatical class. The ways in which quasi-nouns, adjectives, adverbs, transitive and

intransitive verbs will be covered specifically in the sections below, however it is important to know that

while these roots can become any of these derived forms, they will all share the same general meaning as the

original root.

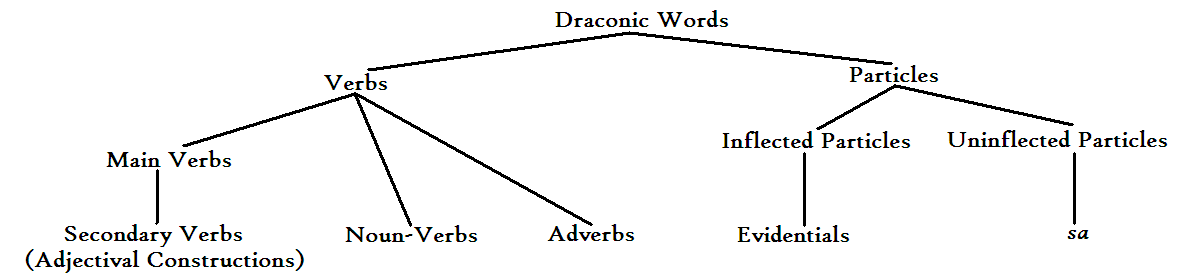

3.4. Particles

The other major component of the Dragon Tongue are particles which are different then verb roots

in that they do not take affixes and thus do not form derivations of the original particle. Although there are

far fewer particles then verb roots, these items are also inherently verbal (although it does not always seem

so) they are used primarily as connecting words between other verbs, either which are a verbal phrase all

their own or between larger verbal structures such as sentences and the like. Unlike the verb roots,

particles derive from the original particle depending on whether or not they are inflected or not. Inflected

particles include the evidentials (shown in 8.3. Evidential Sentence Enclitics) while the single non-inflected

particle is the very productive sa particle. The derivational structure of all draconic words is shown in the

below diagram:

3.5. Inflection of Affixes

One of the biggest differences in the overall structure of the Dragon Tongue and the languages of

humans is its approach to tense. Take the following examples from human languages, all translations of

the same sentence (the present tense verbs are indicated by the bold sections):

English:

German:

Japanese:

Welsh:

Old Irish:

The dragon sees the person

Der Drache sieht den Mann

Ryû ga hito o mimasu

Mae’r ddraig yn gweld y dynol

Fégaid in fer in ndrac

Now look at these same sentences again placed in the past tense (the past tense verbs are again

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

indicated by the bold sections):

English:

German:

Japanese:

Welsh:

Old Irish:

The dragon saw the person

Der Drache sah den Mann

Ryû ga hito o mimashita

Oedd yr ddraig yn gweld y dynol

Fégais in fer in ndrac

In all of the above cases the past tense is indicated by a modification of the verb, either by inflection,

the addition of affixes, the change of an auxiliary verb, and change of position of the main verb or other

modifiers. This is true of every human language I am aware of: tense is indicated by some modification of the

verb as the verb is the “holder of the tense,” so to speak. Now, the question is if every word in Srínawésin

is inherently verbal where is the tense expressed? The present and past versions of the same sentence would

appear as below when spoken by a dragon (tense markers are indicated by bold):

Srínawésin (Present):

Srínawésin (Past):

Sínšáwéts inneqxnéx isihéš ni

Sáýnšáwéts anneqxnéx asihéš na

As you can see, tense markers are not expressed by the main verb alone in either the present or past

tenses (Sínšáwéts and Sáýnšáwéts respectively) but are woven throughout the sentence, appearing in all four

separate words. This answers the question of where tense falls in a language that is comprised wholly by

verbs: Everywhere! This is because since every word in Srínawésin is verbal and verbs are inherently linked

to the expression of past and present, tense is expressed throughout the sentence by inflecting most of the affixes in

terms of tense. As Srínawésin has three tenses, past, present/future and a cyclical time meaning, each affix

will therefore come in three separate forms, i.e. in Past, Non-Past and Cyclical inflections. As far as I am

aware, this system of tense being expressed throughout an utterance is one which is found in the Dragon

Tongue alone and is a product of the inherent verbality of all draconic words. The concept of inflecting the

various affixes for tense is one of vital importance and is always used and is an integral part of forming an

understandable utterance, so always be aware of the inflection of affixes.

One important facet of inflecting affixes is that they all must agree with one another within a

clause, i.e. being Past, Non-Past or Cyclical tense throughout the clause or utterance. Therefore, the sentence

below is incorrect:

*Sáýnšáwéts inneqxnéx asihéš ni

This is because the various expressions of tense clash, expressing the past in Sáínšáwéts and asihéš

while the present in inneqxnéx and ni! While tense must agree within the context of all the affixes within a

clause, tense may switch between the clauses in order to form such sentences as:

Saqxnéhišáwéts aSłáya sa Snaréš nán tsišathíx ni!

Bloody Face saw the human and now he’s running away!

Although the marking of tense on these affixes is both a sentential and clausal aspect of the language

it is also morphological as the root morphemes are expressed in different ways depending on the tense of

the clause, sentence or utterance they are a part of. Luckily the Dragon Tongue is extremely regular in how

it effects these inflections on its affixes, the vowel a (and á) are considered to be Past Tense vowels within

the inflectional paradigm while i (and í) are considered to be Non-Past Tense vowels. The third “Cyclical”

tense uses u (and ú) to indicate tense but for specifics see 4.3. Draconic Tenses. Thus, variations between

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

two sentences which are identical except for their tense the only variations will be between the vowels of

the affixes, as in:

Tsaháqsałášír ayúšíł wáx

Tsiháqsałášír iyúšíł wíx

The bear was probably killing the deer

The bear is probably killing the deer

It is important to note that the inflection of affixes usually only occurs on prefixes and not on

suffixes.