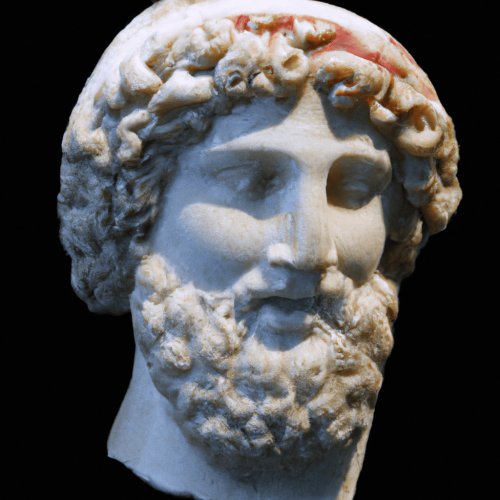

Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite (fl. 500 C.E.)

Dionysius is the author of three long treatises (The Divine Names, The Celestial Hierarchy, and The Ecclesiastical Hierarchy) one short treatise (The Mystical Theology) and ten letters expounding various aspects of Christian Philosophy from a mystical and Neoplatonic perspective. Presenting himself as Dionysius the Areopagite, the disciple of Paul mentioned in Acts 17:34, his writings had the status of apostolic authority until the 19th century when studies had shown the writings denoted a marked influence from the Athenian Neoplatonic school of Proclus and thus were probably written ca. 500. Although the attribution of authorship has proven to be a falsification, the unknown author (hereafter referred to as Ps-Dionysius) has not lost his credibility as an articulate Athenian Neoplatonist expressing an authentic Christian mystical tradition. Indeed with eloquent poetic language and strong exposition of ideas, the Dionysian corpus ranks among the classics of western spirituality.

Table of Contents

History and Development of Christian Platonism up to Pseudo-Dionysius

Mystery Schools, Gnosticism, Hermeticism, and the “Platonic Underground”

The Works of Dionysius the Areopagite

The Divine Names (13 Chapters)

The Mystical Theology (5 Chapters)

The Celestial Hierarchy (15 Chapters)

The Ecclesiastical Hierarchy (7 Chapters)

The Epistles (10 Letters)

The Dionysian Influence

Philosophy

Mysticism

Occultism (Esoteric traditions of Alchemy, Hermetism, Kabbalah)

References and Further Reading

1. History and Development of Christian Platonism up to Pseudo-Dionysius

Born within a 500-year old Graeco-Roman culture, Christianity received a pervasive influence from the then 400-year old Platonist tradition very early on. Despite the official outlawing of so-called pagan philosophy in the 6th century, Platonism or Neoplatonism, continued to maintain a dynamically evolving influence for the ensuing thousand years within the sphere of Christianity and beyond that, interest in Platonism is waxing strong today. In general, the prominent early Christian Platonists were men already possessing a classical Graeco-Roman culture and schooled in the Middle Platonic tradition and who would subsequently convert to Christianity thus bringing their background and knowledge to the service of their new faith. Already, Philo of Alexandria (20 BC – 40 AD) had developed an extensive Middle Platonic interpretation of the Jewish scriptures (scriptural symbology, logos theology, moral philosophy, etc.). With the solid framework provided by Philo, Alexandria became the home of the first Christian Platonists: Clement (160 – 220) and Origen (185 -253) who both in their own way crafted a considerable system of correspondences between Platonism and Christianity. The influence of Neoplatonism can be seen with the Cappadocian fathers Basil (330-379), Gregory Nazianzus (329 – 389), and Gregory of Nyssa (331/40 – ca. 395); as well as Synesius of Cyrene (373? – 414). Origen’s influence continued with the fathers of the Egyptian desert, Macarius (295 – 386), Evagrius Pontus (345 – 399), and John Cassian (+350). The Neoplatonic influence appears in the Latin Church with Marius Victorinus (281/291- ?), Ambrose (354 – 450), Augustine (354 – 430), and Boethius (460? – 524). Philiponus (fl. 500?) is a Christian Neoplatonist who studied with the last teachers of the pagan Athenian school.

2. Mystery Schools, Gnosticism, Hermeticism, and the “Platonic Underground”

In accordance with his Neoplatonic background, Ps-Dionysius adopts the initiation language of the Mystery religions. Basically, the Mystery religions can be considered as the esoteric counterpart to the exoteric popular religions. The symbols and mythology of popular cults of worship are thought to contain an esoteric meaning which reveal a deeper mystical knowledge. The pledge of secrecy being integral to the Mystery religions, comparatively little information about them has come down to us. There seems to be a stock of similar myths, symbols, and ritual common to all of them and their influence was pervasive in both the Pagan and Christian world:

The Soul was the one subject, and the knowledge of the Soul the one object of all the ancient Mysteries. In the ‘Fall’ of PISTIS-SOPHIA, and her rescue by her Syzygy, JESUS, we see the ever-enacted drama of the suffering and ignorant Personality, which can only be saved by the immortal Individuality or rather by its own yearning towards IT (H. P. Blavatsky, “Commentary on the Pistis-Sophia,” in Collected Writings, Vol. XIII, The Theosophical Publishing House, Wheaton: 1982, p. 40).

The Neoplatonic schools at this period can be considered to represent a middle ground between the pagan esoteric cults [Hellenic Mysteries, Oriental Mystery cults (Mithraism, Attis), Hermetism, Greek alchemists (Zosimos)] and the popular state forms of religious worship. Whether a Christian Neoplatonist such as Ps-Dionysius played a similar mediating role between the exoteric forms of Judeo-Christianity (popular Roman Catholic state religion) and esoteric Christianity (Gnosticism, Arianism, Docetism) would be a matter of conjecture, but what is interesting is how the Dionysian corpus formulates a creative philosophical synthesis that reflects a more open Christian position in a period when all the above-mentioned religious movements where in a very dynamic state of ferment and conflict which saw the rise of Christianity and the waning of Paganism.

3. The Works of Dionysius the Areopagite

There are five works ascribed to Dionysius: The Divine Names, The Mystical Theology, The Celestial Hierarchy, The Ecclesiastical Hierarchy and his Epistles. All of these works are interrelated and, taken together, form a complex whole. Paul Rorem gives a very good overview of how these works unfold:

The point here is that not all affirmations concerning God are equally inappropriate; they are arranged in a descending order of decreasing congruity. Affirmative theology begins with the loftier, more congruous comparisons and then proceeds “down” to the less appropriate ones. Thus, as the author reminds us, The Theological Representations [not extant] began with God’s oneness and proceeded down into the multiplicity of affirming the Trinity and the incarnation. The Divine Names then affirmed the more numerous designations for God which come from mental concepts, while The Symbolic Theology [not extant] “descended” into the still more pluralized realm of sense perception and its plethora of symbols for the deity. This pattern of descending affirmations and ascending negations can be interpreted in terms of late Neoplatonism’s “procession” from the One down into plurality and the “return” of all back to the One. In the “return,” not all negations concerning God are equally appropriate; the attributes to be negated are arranged in an ascending order of decreasing incongruity, first considering and negating the lowest or most obviously false statements about God and then moving up to deny these that may seem more congruous. Thus the first to be denied are the perceptible attributes, starting with The Mystical Theology, Chapter 4, which therefore previews the two subsequent treatises on perceptible symbols, The Celestial Hierarchy and The Ecclesiastical Hierarchy. Chapter 2 of the former work will continue the theme of negating and transcending symbols, namely, interpreting first the most incongruous of the perceptible symbols attributed to the celestial, whether to the angels or to God. The anagogical or uplifting method of interpretation in these two treatises incorporates into itself the principles of negative theology. Both the spatial, material depiction of the angels in the scriptures and also the temporal, sequential images of God in the liturgy must be transcended in the ascent from the perceptible to the intelligible. Thus, “as we climb higher,” Chapter 5 of The Mystical Theology denies and moves beyond all our concepts or “conceptual” attributes of God and concludes by abandoning all speech and thought, even negations. (Pseudo-Dionysius, The Complete Works, New York: Paulist Press 1987, p.140 note).

a. The Divine Names (13 Chapters)

Chapter 1 Dionysius the Elder to Timothy the Fellow Elder: What the goal of this discourse is, and the tradition regarding the divine names. A general introduction in which God is considered omniscient, beyond all human understanding and description and therefore can only be expressed through symbols, names which are found in the scriptures. One can approach the truth of God through contemplation of the Divine Symbols. The conception of God is a philosophical one, akin to the One, or the Good of Neoplatonism, and not anthropomorphic Old Testament God of popular theology.

Chapter 2 Concerning the unified and differentiated Word of God, and what the divine unity and differentiation is.

The Neoplatonic concept of emanation finds its counterpart in the “divine procession.” Jesus Christ is considered to be a mystery that is beyond human contemplation.

Chapter 3 The power of praying, concerning the blessed Hierotheus, piety and our theology. Here the author speaks of his teacher Hierotheus and refers to a work of his entitled “Elements of Theology” which is not extant.

Chapter 4 Concerning “God,” “Light,” “Beautiful,” “Love,” “Ecstasy,” and “Zeal” and that evil is neither a being, nor from a being, nor in beings. Here begins the metaphysical explanations of the Divine Names taken from the scriptures. Also explained is the mystical concept of “yearning” for union with the Good and the Beautiful. The philosophical explanation of evil is evidently much more Platonic than the anthropomorphic concept of evil as expressed by the conventional church dogma. (The parallels on the discussion of evil to the De Malorum Subsistentia of Proclus provided the initial clues in proving the pseudonymous authorship.)

Chapter 5 Concerning “Being” and also concerning paradigms. The metaphysical causes of Being are discussed.

Chapter 6 Concerning “Life.” The transcendent, absolute, eternal nature of life is dealt with.

Chapter 7 Concerning “Wisdom,” “Mind,” “Truth,” “Faith.” The basis of a divine, transcendent wisdom where humans derive their intelligence and understanding through participation with the Divine Mind is discussed.

Chapter 8 Concerning “Power,” “Righteousness,” “Salvation,” “Redemption,” and also inequality. This chapter deals with the ordering of the universe according to divine laws by which a transcendent order maintains the dynamic harmony of all things.

Chapter 9 Concerning greatness and smallness, sameness and difference, similarity and dissimilarity, rest, motion, equality. It is shown how the fundamental unity of God can be seen in the multiplicity of the universe at the macrocosmic and microcosmic levels.

Chapter 10 Concerning “Omnipotent,” “Ancient of Days,” and also concerning “Eternity” and “Time.” This chapter deals with the philosophical aspects of time and eternity.

Chapter 11 Concerning “Peace,” and what is intended by “being itself,” “power itself” and things said in this vein. The intelligent harmony which brings things together in a communion of concord is discussed.

Chapter 12 Concerning “Holy of Holies,” “King of Kings,” “Lord of Lords,” “God of Gods.” Holy of Holies deals with Purity; Kingship, with law and order; Lordship, stability through possession of the Good and the Beautiful, God, Providence which sees everything.

Chapter 13 Concerning “Perfect” and “One.” Here is a synthesis of the whole work, returning to the idea of the One as discussed in Neoplatonic terms.

b. The Mystical Theology (5 Chapters)

Chapter 1 An explanation of Ps-Dionysius’ negative theology in which one rises to high levels of divine contemplation by defining God by what it is not because it is beyond assertion and denial.

Chapter 2 How one should be united to, and attribute praises to the cause of all things which is beyond all things.

Chapter 3 What are the affirmative theologies and what are the negative. The higher we rise towards the transcendent, the more language fails to describe it.

Chapter 4 That the supreme cause of every perceptible thing is not itself perceptible. The negative theology begins by denying it all formal existence perceptible by the senses.

Chapter 5 It is stated that the supreme Cause of every conceptual thing is not itself conceptual. We are to apprehend it by rising to the highest concepts and then going beyond where neither assertion nor denial can be attributed to it.

c. The Celestial Hierarchy (15 Chapters)

Chapter 1 That every divine illumination, descending with goodness and according to different modes to the object of its providence, remains nonetheless simple, and indeed unifies what it illumines. The treatise begins with an explanation of the value of the symbol as a representation of spiritual essences.

Chapter 2 It is appropriate to reveal the mysteries of God and of heaven with symbols without resemblance. Here it is explained that the many images and symbols in the Bible are not meant to be taken at dead letter face value. As man is incapable of contemplating Divine Truth directly, our divinely inspired ancestors have left us symbols adapted to our capacity of understanding which help us to raise our consciousness to the understanding and contemplation of the divine truths; the second function of the symbol is that it also serves as a veil to these sacred truths for those who it would be imprudent to reveal these things to. The value of the symbol therefore depends on the person’s capacity to penetrate its secrets.

Chapter 3 In what does the Hierarchy consist of and what is its use. The notion of hierarchy is that seeing that not everyone can equally directly contemplate and participate in the supreme cause, there is therefore a great chain of hierarchies emanating from the most spiritual origins down to the most material planes. To undertake the divine ascension, there are intermediaries for every level of reality like the steps on a ladder. The higher hierarchies, receiving a more direct illumination, can transmit that light to the lower hierarchies at the level they are able to perceive it and the higher hierarchies also serve as an accessible image of the transcendent, an example for the hierarchy immediately below, whose members can contemplate in order to rise to a higher level. The closer a hierarchy is to the source of divine light, the greater the degree of purity and simplicity and resemblance to the source.

Chapter 4 What the names given to the angels signify. An interesting point concerning the hierarchies is that no human being can directly contemplate the ultimate Source. Even Moses did not have a direct vision of God but rather a vision adapted to his level of perception. It is shown how the incarnation of Christ was done in accord with the hierarchical order of angels.

Chapter 5 Why are all the celestial essences distinctly called angels. On the hierarchical scales the angels are at the lowest degree of the hierarchy. This is because the higher levels contain all the illumination and power of the lower levels; but the lower do not have the same level of participation with the higher. Therefore the term angel is used because, in a sense, it is the lowest common denominator.

Chapter 6 What is the first order of the celestial essences, what is the middle order and what is the inferior order.

All the names of the hierarchies appear in the scriptures. They are divided into three groups of three hierarchies each:

First – Seraphim, Cherubim and Thrones

Second – Dominions, Virtues and Powers

Third – Principalities, Archangels and Angels

Chapter 7 Of the Seraphim, the Cherubim and the Thrones and of the first hierarchy that they constitute. The meaning of the first three angelic hierarchies are as follows:

Seraphim – Fire, “Those who burn”

Cherubim – Messengers of knowledge, Wisdom

Thrones – Seat of God

Chapter 8 Of the Dominions, the Virtues and the Powers and the middle hierarchy that they constitute. The meaning of the second order of the hierarchies are as follows:

Dominions – Justice

Virtues – Courage, Virility

Powers – Order, Harmony

Chapter 9 Of the Principalities, the Archangels and the Angels and of the last hierarchy that they constitute. The meaning of the third order are as follows:

Principalities – Authority

Archangels – Unity

Angels – Revelation, messengers

Chapter 10 Recapitulation and conclusion concerning the proper ordering of the angelic hierarchy. Each order, therefore has in itself three orders – first, middle and last. It is said that none of the orders are totally perfect; all the hierarchies thus mutually participate in a constant march, striving towards perfection.

Chapter 11 Why all the celestial essences receive in common the name of the celestial powers. The celestial powers have three qualities – essence, power and act.

Chapter 12 Why do the highest of high priests receive the name of angels. Why are priests called angels? Because although the lower orders do not participate of the higher orders per se, the illuminations of the higher orders do radiate all the way through to the lowest orders in a gradually decreasing brightness, therefore it can be said that the lower can receive the light of the higher in an indirect manner.

Chapter 13 Why is it said that it is the Seraphim that purified the prophet Isaiah. In the Bible, when Isaiah was purified by a Seraphim, it is not to be understood that he was in direct contact with such an immeasurably high order; what is meant is that the illuminating properties and powers of the order of the Seraphim had descended through the several intermediary orders to purify Isaiah. It is a question of opacity and translucency in regards to the light. Light shines and its rays can pass through substances depending on its degree of translucency, will reflect more or less of the light. This analogy applies to human consciousness in relation to divine light.

Chapter 14 What does the number attributed to the angels signify. It is stated that there are an immeasurable number of angels in every order, and therefore a truly infinite number of angels are acting in the various planes of the universe. There is an angel overlooking the welfare of every nation as well.

Chapter 15 What are the figurative images of the angelic powers. This chapter discusses the various symbols in reference to the angelic functions such as fire; man; infant; sacred clothes and instruments; air, wind and clouds; metals and stones; animals.

d. The Ecclesiastical Hierarchy (7 Chapters)

Chapter 1 What is the tradition of the ecclesiastical hierarchy and what is its purpose. It is explained how the tradition began initially with a divine transmission of sacred symbols and forms which were thereafter transmitted to succeeding generations.

Chapter 2. 1 The rite of illumination.

The goal of the hierarchy is “greatest likeness and union with god through obedience of the commandments and doing the sacred acts.” And the first initiation is the divine birth, meaning birth to a spiritual life.

2.2 A postulant who wishes to enter the spiritual life has a sponsor who presents him to the hierarch. The postulant goes through various ritual gestures including being anointed with oil and immersed in water three times. It is a baptism.

2.3 This is a practical applications of the symbols. The rituals are not merely functional gestures but are meant to convey actual transformation processes in the candidates consciousness. For example, the immersion in water symbolizes a dissolution of the old material way of life to reemerge into the spiritual which is further symbolized by putting on bright new clothes and fragrant ointments. Firm opposition to whatever hinders our communion, brave resolution in striving to uplift oneself and a will for victory over the forces of death and destruction is stressed.

Chapter 3.1 The rite of the synaxis.

Or the Eucharist. What these initiation operations do is by granting communion, it gives the participants an inner unity by gathering together the divided and scattered fragments of our consciousness.

3.2 Mystery of the synaxis or communion. The Eucharist is the ritual re-enactment of the last supper.

3.3 A symbolic explanation of the Eucharist is explained as well as the value of Christ’s example that we should strive to imitate. There is also different levels of participation in the ceremonies according to one’s level of purification, clarity of vision, and freedom from fantasies.

Chapter 4.1 The ritual of ointment and what is perfected by it. The ointment is the third of the three holy sacraments explained.

4.2 Mystery of the sacred ointment. This consists in consecrating the sacred ointment used for almost all the sacraments of sanctification and rites of consecration.

4.3 Perfecting and consecrating with ointment – symbolizes a visitation of the Divine Spirit.

Chapter 5.1 Concerning the clerical orders, powers, activities, and consecrations. Here are three orders which are a reflection of the triple order of the celestial hierarchy. And these orders have a further triple division. Furthermore they have a triple power of purification, illumination and perfection.

1- Hierarchs – Sanctification of clerical orders, consecration of ointment and rite of purification and consecration of the Holy butter.

2- Priests – Illumination

3- Deacons – Purification

5.2 The mystery of the clerical consecrations of the three orders. The various rites of consecration of the three orders are explained.

5.3 The hierarch does not work the consecration through his own personal authority but is rather an intermediary for the Divine Powers.

Chapter 6.1 Concerning the orders of those being initiated. Various categories of candidates who will approach the mysteries are detailed:

1- The three orders of candidates receiving direct instruction (incubation, instruction).

2- Those who fell away and are returning to the church.

3- Those who are weak, fearful and require strengthening.

4- Those who have lived a life of sin and need sanctification.

5- Those who are attentive to the spiritual life but lack firmness in practice.

There is then an intermediate level – those ready to enter upon the path of contemplation; candidate priests for illumination.

There is also the order of monks – they are considered purified and have complete power and holiness in its own activities within the hierarchies.

6.2 Mystery of the consecration of a monk. The monastic profession and tonsure is explained.

6.3 Renunciation of all activities in act and thought that distract from the sacred life is stressed. The correspondence of purification, illumination and perfection with the celestial hierarchies is explained.

Chapter 7.1 The rite for the dead. Dying is called a sacred rebirth.

7.2 Mystery regarding those who died sacredly. The rites are explained for those who belong to the orders.

7.3 The rewards are not equal for all. One will live in a state of blessedness in the afterlife corresponding to the degree of saintliness one has achieved in material life. This treatise closes on a point concerning baptism of children. The idea of baptism at a young age is that it is considered good to develop sacred habits at a young age and the baptism is effected only if it is agreed that the child be entrusted to a spiritual parent who will afterwards provide them with a religious education.

e. The Epistles (10 Letters)

Letter 1 – To the monk, Gaius– Deals with negative theology.

Letter 2 – To the monk, Gaius– Is a discussion on the Good.

Letter 3 – To the monk, Gaius– Deals with the mystery of Jesus.

Letter 4 – To the monk, Gaius– Of the transcendent character of Jesus; the humanity of Jesus is emphasized.

Letter 5 – To Dorotheus, deacon– Deals with negative theology.

Letter 6 – To Sosipater, Priest– Denis is against the denunciation of cults who express a different point of view than Christianity.

Letter 7 – To Polycarp, a hierarch– Regarding a discussion with Apollophanes, a sophist, Ps-Dionysius counsels not to refute his opinions but simply establish the truth as clearly as he can and let the validity of his explanations stand for themselves. There is a reference to the Mithraic cult as well as to various Christian miracles.

Letter 8 To Demophilus, a monk– This is the longest of the letters and concerns a monk who turned away a repenting sinner who wished to return to the church. Ps-Dionysius disapproves of the monk’s actions and extols the virtue of meekness, kindness and tolerance in which reason governs anger. There are also many details concerning the practical functioning of the ecclesiastical hierarchy and the authority and respect that the respective ranks should command. The letter ends with a personal relating of a miraculous vision of a certain Carpos illustrating the mercifulness of Jesus.

Letter 9 To Titus, Hierarch– A question concerning the symbolism of the mixing bowl and food and drink as spiritual nourishment is dealt with.

Letter 10 To John the theologian– In this letter, words of comfort and support to an exiled apostle are conveyed.

4. The Dionysian Influence

The Dionysian corpus has had an wide influence on various aspects of Christian thought. The following list is divided into three general currents of influence: philosophy, mysticism and occultism. By no means comprehensive, this list aims to simply give a general overview of some prominent thinkers in the Christian Platonist tradition. The three categories are very general and the categorization loose, as many people on this list could easily overlap into several categories.

a. Philosophy

Maximus Confessor (580 – 662), Alcuin (730 – 806), John Scotus Eriugena (fl. 850), Michael Psellus (1018 – 1096), Hugh of St-Victor (+1141), Richard of St-Victor (+1173), Thomas Aquinas (1125 – 1274), Thiery of Chartres (fl. 1142 -1150), Robert Grosseteste (1175 – ca. 1225?) Bonaventure (1221 – 1274), Gemisthos Plethon (ca. 1370? – 1450), Nicholas of Cusa (1401 – 1464), Denis the Carthusian (1402 – 1471), Marsilio Ficino (1433 – 1499), Lefebvre d’Etaples (1436 -1520), Thomas Vaughan (1622 – 1666).

b. Mysticism

Bernard of Clairvaux (1091 -1153), Hildegarde of Bingen (1098 – 1179), Jacopone da Todi (1128 – 1306), Meister Eckhart (1260 – 1327), John Tauler (1300 -1361), Henry Suso (ca. 1295 – 1365), John Ruysbroeck (1293 – 1381), Henry de Mayle (ca. 1360 – 1415), Catherine of Sienna (1347 -1380), Jean Gerson (1363 – 1409), Francisco de Orsuna (+1540), Teresa of Avila (1515 – 1582), John of the Cross (1515 – 1582), Augustine Baker (1575 -1641), unknown author of the Cloud of Unknowing (ca. 1350 – 1395)

c. Occultism (Esoteric traditions of Alchemy, Hermetism, Kabbalah)

Albert the Great (1206 – 1240), Roger Bacon (1210/14 – ca. 1292), Dante (1265 – 1321), Ramon Lully (1232 – 1316?), Johannes Reuchlin (1455 -1522), Johannes Trithemius (1462 -1516), Pico de la Mirandola (1463 – 1494), Francesco Giorgi (1466 -1540), Cornelius Agrippa (1486 – 1534), John Dee (1537 -1608), Giordano Bruno (1548 – 1600), Robert Fludd (1574-1637) Jacob Boehme (1575 – 1624), William Law (1686 -1761), Eckhartausen (1752 -1803), Louis-Claude de St-Martin (1743 -1803), William Blake (1757 -1827).

5. References and Further Reading

Dillon, John, The Middle Platonists, Duckworth, Great Britain, 1977.

Ferguson, Everett (ed.), Encyclopedia of Early Christianity, Garland Publishing, New York, 1990.

Finan, Thomas; Twaney, Vincent (eds.), The Relationship between Neoplatonism and Christianity, Four Courts Press, Dublin, 1992.

Luibheid, Colm (transl.), Pseudo-Dionysius: The Complete Works, Paulist Press (Classics of Western Spirituality), New York, 1987.

Livraga, Jorge Angel, Manuel d’Introduction aux philosophies d’orient et d’occident, Nouvelle Acropole, France.

O’Leary, Dominic J., Neoplatonism and Christian Thought, State University Press, New York, 1982.

Underhill, Evelyn, Mysticism, Meridian, Noonday Press, New-York, 1955.

Yates, Frances A., Giordano Bruno and the Hermetic Tradition, Routledge and Kegan Paul, London. 1964.

Author Information

Mark Lamarre

Email: [email protected]

U. S. A.