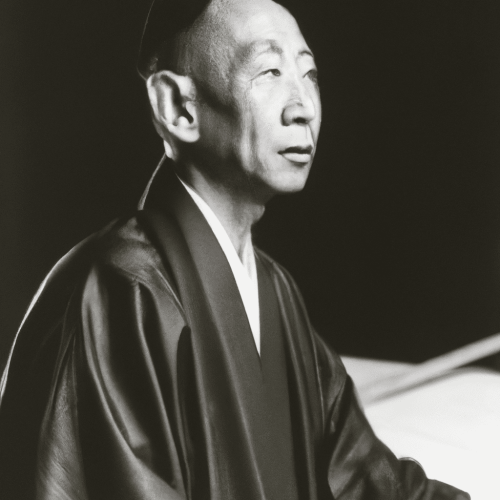

Mou Zongsan (Mou Tsung-san) (1909—1995)

Mou Zongsan (Mou Tsung-san) is a sophisticated and systematic example of a modern Chinese philosopher. A Chinese nationalist, he aimed to reinvigorate traditional Chinese philosophy through an encounter with Western (and especially German) philosophy and to restore it to a position of prestige in the world. In particular, he engaged closely with Immanuel Kant’s three Critiques and attempted to show, pace Kant, that human beings possess intellectual intuition, a supra-sensible mode of knowledge that Kant reserved to God alone. He assimilated this notion of intellectual intuition to ideas found in Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism and attempted to expand it into a metaphysical system that would establish the objectivity of moral values and the possibility of sagehood.

Mou’s Collected Works run to thirty-three volumes and extend to history of philosophy, logic, epistemology, ontology, metaethics, philosophy of history, and political philosophy. His corpus is an unusual hybrid in that although its main aim is to erect a metaphysical system, many of the books where Mou pursues that end consist largely of cultural criticism or histories of Confucian, Buddhist, or Daoist philosophy in which Mou explains his own opinions through exegesis of other thinkers’ in a terminology appropriated from Kant, Tiantai Buddhism, and Neo-Confucianism.

Table of Contents

Biography

Cultural Thought

Chinese Philosophy and the Chinese Nation

Development of Chinese Philosophy

History of Chinese Philosophy: Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism

Metaphysical Thought

Intellectual Intuition and Things-in-Themselves

Two-Level Ontology

Perfect Teaching

Criticisms

Influence

References and Further Reading

1. Biography

Mou was born in 1909, at the very end of China’s imperial era, into the family of a rural innkeeper who admired Chinese classical learning, which the young Mou came to share. At just that time, however, traditional Chinese learning was being denigrated by some of the intellectual elite, who searched frantically for something to replace it due to fears that their own tradition was dangerously impotent against modern nation-states armed with Western science, technology, bureaucracy, and finance.

In 1929, Mou enrolled in Peking (Beijing) University’s department of philosophy. He embarked on a deep study of Russell and Whitehead’s Principia Mathematica (then a subject of great interest in Chinese philosophical circles ) and also of Whitehead’s Process and Reality. However, Mou was also led by his interest in Whiteheadian process thought to read voraciously in the pre-modern literature on the Yijing (I Ching or Book of Changes), and his classical tastes made him an oddball at Peking University, which was vigorously modernist and anti-traditional. Mou would have been a lonely figure there had he not met Xiong Shili in his junior year. Xiong was just making his name as a nationally known apologist for traditional Chinese philosophy and mentored Mou for years afterward. The two men remained close until Mou later left the mainland. Mou graduated from Peking University in 1933 and moved around the country unhappily from one short-term teaching job to another owing to frequent workplace personality conflicts and fighting between the Chinese government and both Japanese and Communist forces. Despite these peregrinations, Mou wrote copiously on logic and epistemology and also on the Yijing. Mou hated the Communists very boisterously and when they took over China in 1949 he moved to Taiwan and spent the next decade teaching and writing in a philosophical vein about the history and future of Chinese political thought and culture. In 1960, once again unhappy with his colleagues, Mou was invited by his friend Tang Junyi, also a student of Xiong, to leave Taiwan for academic employment in Hong Kong. There, Mou’s work took a decisive turn and entered what he later considered its mature stage, yielding the books which established him as a key figure in modern Chinese philosophy. During the next thirty-five years he published seven major monographs (one running to three volumes), together with translations of all three of Immanuel Kant’s Critiques and many more volumes’ worth of articles, lectures, and occasional writings. Mou officially retired from the Chinese University of Hong Kong in 1974 but continued to teach and lecture in Hong Kong and Taiwan until his death in 1995.

We can divide Mou’s expansive thought into two closely related parts which we might call his “cultural” thought, about the history and destiny of Chinese culture, and his “metaphysical” thought, concerning the problems and doctrines of Chinese philosophy, which Mou thought of as the essence of Chinese culture.

2. Cultural Thought

a. Chinese Philosophy and the Chinese Nation

Like most intellectuals of his generation, Mou was a nationalist and saw his work as a way to strengthen the Chinese nation and return it to a place of greatness in the world.

Influenced by Hegel, Mou thought of the history and culture of the Chinese nation as an organic whole,, with a natural and knowable course of development. He thought that China’s political destiny depended ultimately on its philosophy, and in turn blamed China’s conquest by the Manchus in 1644, and again by the Communists in 1949, on its loss of focus on the Neo-Confucianism of the Song through Ming dynasties (960-1644). He hoped his own work would help to re-kindle China’s commitment to Confucianism and thereby help defeat Communism.

Along with many of his contemporaries, Mou was interested in why China never gave rise its own Scientific Revolution like that in the West, and also in articulating what the strengths were in China’s intellectual history whereby it outstripped the West. Mou phrased his answer to these two questions in terms of “inner sagehood” (neisheng) and “outer kingship” (waiwang). By “inner sagehood,” Mou meant the cultivation of moral conduct and outlook—at which he thought Confucianism was unequalled in the world—and he used “outer kingship” to encompass political governance, along with other ingredients in the welfare of society, such as a productive economy and scientific and technological know-how. Mou thought that China’s classical tradition was historically weak in the theory and practice of “outer kingship,” and he believed that Chinese culture would have to transform itself thoroughly by discovering in its indigenous learning the resources with which to develop traditions of science and democracy.

For the last thirty years of his life, all of Mou’s writings were part of a conversation with Immanuel Kant, whom he considered the greatest Western philosopher and the one most useful for exploring Confucian “moral metaphysics.” Throughout that half of his career, Mou’s books quoted Kant extensively (sometimes for pages at a time) and appropriated Kantian terms into the service of his reconstructed Confucianism. Scholars agree widely that Mou altered the meanings of these terms significantly when he moved them from Kant’s system into his own, but opinions vary about just how conscious Mou was that he had done so.

b. Development of Chinese Philosophy

As an apologist for Chinese philosophy, Mou was anxious to show that its genius extended to almost all areas and epochs of Chinese philosophy. To this end, He wrote extensively about the history of Chinese philosophy and highlighted the important contributions of Daoist and Buddhist philosophy, along with their harmonious interaction with Confucian philosophy in the dialectical unfolding and refinement of Chinese philosophy in each age.

Before China was united under the Qin dynasty (221-206 BCE), Mou believed, Chinese culture gave definitive form to the ancient philosophical inheritance of the late Zhou dynasty (771-221 BCE), culminating in the teachings of Confucius and Mencius. These were still epigrammatic rather systematic, but Mou thought that they already contained the essence of later Chinese philosophy in germinal form. The next great phase of development came in the Wei-Jin period (265-420 CE) with the assimilation of “Neo-Daoism” or xuanxue (literally “dark” or “mysterious learning”), from whence came the first formal articulation of the “perfect teaching” (concerning which see below). Shortly afterward, Mou taught, Chinese culture experienced its first great challenge from abroad, in the form of Buddhist philosophy. In the Sui and Tang dynasties (589-907) it was the task of Chinese philosophy to “digest” or absorb Buddhist philosophy into itself. In the process, it gave birth to indigenous Chinese schools of Buddhist philosophy (most notably Huayan and Tiantai), which Mou believed advanced beyond the Indian schools because they agreed with essential tenets of native Chinese philosophy, such as the teaching that all people are endowed with an innately sagely nature.

On Mou’s account, in the Song through Ming dynasties (960-1644) Confucianism underwent a second great phase of development and reasserted itself as the true and proper leader of Chinese culture and philosophy. However, at the end of the Ming, there occurred what Mou taught was an alien irruption into Chinese history by the Manchus, who thwarted the “natural” course of China’s cultural unfolding. In the thinking of late Ming philosophers such as Huang Zongxi (1610-1695), Gu Yanwu (1613-1682), and Wang Fuzhi (1619-1692), Mou thought that China had been poised to give rise to its own new forms of “outer kingship” which would have eventuated in an indigenous birth of science and democracy in China, enabling China to compete with the modern West. Chinese culture, however. was diverted from that healthy course of development by the intrusion of the Manchus. Mou believed that it was this diversion which made China vulnerable to the Communist takeover of the 20th century by alienating it from its own philosophical tradition.

Mou preached that the mission of modern Chinese philosophy was to achieve a mutually beneficial conciliation with Western philosophy. Inspired by the West’s example, China would appropriate science and democracy into its native tradition, and the West in turn would benefit from China’s unparalleled expertise in “inner sagehood,” typified especially by its “perfect teaching.”

However, throughout Mou’s lifetime, he remained unimpressed with the actual state of contemporary Chinese philosophy. He seldom rated any contemporary Chinese thinkers as worthy of the name “philosopher,” and he mentioned Chinese Marxist thought only rarely and only as a force entirely antipathetic to true Chinese philosophy.

c. History of Chinese Philosophy: Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism

In his historical writings on Confucianism, Mou is most famous for his thesis of the “three lineages” (san xi). Whereas Neo-Confucians where traditionally grouped into a “School of Principle” represented chiefly by Zhu Xi (1130-1200) and a “School of Mind” associated with Lu Xiangshan (1139-1192) and Wang Yangming (1472-1529), Mou also recognized a third lineage exemplified by lesser-known figures as Hu Hong (Hu Wufeng) (1105-1161) and Liu Jishan (Liu Zongzhou) (1578-1645).

Mou judged this third lineage to be the true representatives of Confucian orthodoxy. He criticized Zhu Xi, conventionally regarded as the authoritative synthesizer of Neo-Confucian doctrine, as a usurper who despite good intentions depicted heavenly principle (tianli) in an excessively transcendent way that was foreign to the ancient Confucian message. On Mou’s view, that message is one of paradoxical “immanent transcendence” (neizai chaoyue), in which heavenly principle and human nature are only lexically distinct from each other, not substantially separate. It was because Mou believed that the Hu-Liu lineage of Neo-Confucianism expressed this paradoxical relationship most accurately and artfully that that he ranked it the highest or “perfect” (yuan) expression of Confucian philosophy. (See “Perfect Teaching” below.)

Because Mou wanted to revalorize the whole Chinese philosophical tradition, and not just its Confucian wing, he also wrote extensively on Chinese Buddhist philosophy. He maintained that Indian Buddhist philosophy had remained limited and flawed until in migrated to China, where it was leavened with what Mou saw as core principles of indigenous Chinese philosophy, such as a belief in the basic goodness of both human nature and the world. From Chinese Buddhist thought he adopted methodological ideas that he later applied to his own system. One of these was “doctrinal classification” (panjiao), a doxographic technique of reading competing philosophical systems as forming a dialectical progression of closer and closer approximations to a “perfect teaching” (yuanjiao), rather than as mutually incompatible contenders. Much as Mou discovered what he thought of as the highest expression of Confucian doctrine in the largely forgotten thinkers of the Hu-Liu lineage, he found what he thought of as their formal analog and philosophical precursor in the relatively obscure Tiantai school of Buddhism and its thesis of the identity of enlightenment and delusion.

Mou wrote far less about Daoism than Confucianism or Buddhism, but at least in principle he regarded it too as an indispensible part of the Chinese philosophical heritage. Mou focused most on the “Inner Chapters” (neipian) of the Zhuangzi, especially the “Wandering Beyond” (Xiaoyao you) and “Discussion on Smoothing Things Out”(Qi wu lun) and the writings of Wei-Jin commentators Guo Xiang (c. 252-312 CE) and Wang Bi (226-249 CE). Mou saw the Wei-Jin idea of “root and traces” (ji ben) in particular as an early forerunner of Tiantai Buddhist thinking central to its concept of the “perfect teaching.”

3. Metaphysical Thought

In his metaphysical writings, Mou was mainly interested in how moral value is able to exist and how people are able to know it. Mou hoped to show that humans can directly know moral value and indeed that such knowledge amounts to knowledge par excellence. In an inversion of one of Kant’s terms, he called this project “moral metaphysics” (daode de xingshangxue), meaning a metaphysics in which moral value is ontically primary. That is, a moral metaphysics considers that the central ontological fact is that moral value exists and is known or “intuited” by us more directly than anything else. Mou believed that Chinese philosophy alone has generated the necessary insights for constructing such a moral metaphysics, whereas Kant (who represented for Mou the summit of Western philosophy) did not understand moral knowing because, fixated on theoretical and speculative knowledge, he wrong-headedly applied the same transcendentalism that Mou found so masterful in the Critique of Pure Reason (which supposes that we know a thing not directly but only through the distorting lenses of our mental apparatus) to moral matters, where it is completely out of place.

a. Intellectual Intuition and Things-in-Themselves

For many, the most striking thing about Mou’s philosophy (and the hardest to accept) is his conviction that human beings possess “intellectual intuition” (zhi de zhijue), a direct knowledge of reality without resort to the senses and without overlaying such sensory forms and cognitive categories as time, space, number, and cause and effect.

As with most of the terms that Mou borrowed from Kant, he attached a much different meaning to ‘intellectual intuition.’ For Kant, intellectual intuition was a capacity belonging to God alone. However, Mou thought this was Kant’s greatest mistake and concluded that one of the great contributions of Chinese philosophy to the world was a unanimous belief that humans have intellectual intuition. In the context of Chinese philosophy he took ‘intellectual intuition’ as an umbrella term for the various Confucian, Buddhist, and Daoist concepts of a supra-mundane sort of knowing that, when perfected, makes its possessor a sage or a buddha.

On Mou’s analysis, though Confucian, Buddhist, and Daoist philosophers call intellectual intuition by different names and theorize it differently, they agree that it is available to everyone, that it transcends subject-object duality, and that it is higher than, and prior to, the dualistic knowledge which comes through the “sensible intuition” of seeing and hearing, often called “empirical” (jingyan) or “grasping” (zhi) knowledge in Mou’s terminology. However, Mou taught that the Confucian understanding of intellectual intuition (referred to by a variety of names such as ren, “benevolence,” or liangzhi, “innate moral knowing”) is superior to the Buddhist and Daoist conceptions because it recognizes that intellectual intuition is essentially moral and creative.

Mou thought that people regularly manifest intellectual intuition in everyday life in the form of morally correct impulses and behaviors. To use the classic Mencian example, if we see a child about to fall down a well, we immediately feel alarm. For Mou, this sudden upsurge of concern is an occurrence of intellectual intuition, spontaneous and uncaused. Furthermore, Mou endorsed what he saw as the Confucian doctrine that it is this essentially moral intellectual intuition that “creates” or “gives birth to the ten thousand things” (chuangsheng wanwu) by conferring on them moral value.

b. Two-Level Ontology

Through our capacity for intellectual intuition, Mou taught, human beings are “finite yet infinite” (youxian er wuxian). He accepted Kant’s system as a good analysis of our finite aspect, which is to say our experience as beings who are limited in space and time and also in understanding, but he also thought that in our exercise of intellectual intuition we transcend our finitude as well.

Accordingly, Mou went to great pains to explain how the world of sensible objects and the realm of noumenal objects, or objects of intellectual intuition, are related to each other in a “two-level ontology” (liangceng cunyoulun) inspired by the Chinese Buddhist text The Awakening of Faith. In this model, all of reality is said to consist of mind, but a mind which has two aspects (yixin ermen). As intellectual intuition, mind directly knows things-in-themselves, without mediation by forms and categories and without the illusion that things-in-themselves are truly separate from mind. This upper level of the two-level ontology is what Mou labels “ontology without grasping” (wuzhi cunyoulun), once again choosing a term of Buddhist inspiration. However, mind also submits itself to forms and categories in a process that Mou calls “self-negation” (ziwo kanxian). Mind at this lower level, which Mou terms the “cognitive mind” (renzhi xin), employs sensory intuition and associated cognitive processes to apprehend things as discrete objects, separate from each other and from mind, having location in time and space, numerical identity, and causal and other relations. This lower ontological level is what Mou calls “ontology with grasping” (zhi de cunyoulun).

c. Perfect Teaching

On Mou’s view, all of the many types of Chinese philosophy he studied taught some version of this doctrine of intellectual intuition, things-in-themselves, and phenomena, and he considered it important to explain how he adjudicated among these many broadly similar strains of philosophy. To that end, he borrowed from Chinese Buddhist scholasticism the concept of a “perfect teaching” (yuanjiao) and the practice of classifying teachings (panjiao) doxographically in order to rank them from less to more “perfect” or complete.

A perfect teaching, in Mou’s sense of the term, is distinguished from a penultimate one not by its content (which is the same in either case) but by its rhetorical form. Specifically, a perfect teaching is couched in the form of a paradox (guijue). In Mou’s opinion, all good examples of Chinese philosophy acknowledge the commonsense difference between subject and object but also teach that we can transcend that difference through the exercise of intellectual intuition. But what distinguishes a perfect teaching is that it makes a show of flatly asserting, in a way supposed to surprise the listener, that subject and object are simply identical to one another, without qualification.

Mou developed this formal concept of a perfect teaching from the example offered by Tiantai Buddhist philosophy. He then applied it to the history of Confucian thought, identifying what he thought of as a Confucian equivalent to the Tiantai perfect teaching in the writings of Cheng Hao (1032-1085), Hu Hong, and Liu Jishan. Though Mou believed that all three families of Confucian philosophy—Confucian, Buddhist, and Daoist—had their own versions of a perfect teaching, he rated the Confucian perfect teaching more highly than the Buddhist or Daoist ones, for it gives an account of the “morally creative” character of intellectual intuition, which he thought essential. In the Confucian perfect teaching, he taught, intellectual intuition is said to “morally create” the cosmos in the sense that it gives order to chaos by making moral judgments and thereby endowing everything in existence with moral significance.

Mou claimed that the perfect teaching was a unique feature of Chinese philosophy and reckoned this a valuable contribution to world philosophy because, in his opinion, only a perfect teaching supplied an answer to what he called the problem of the “summum bonum” (yuanshan) or “coincidence of virtue and happiness” (defu yizhi), that is, the problem of how it can be assured that a person of virtue will necessarily be rewarded with happiness. He noted that in Kant’s philosophy (and, in his opinion, throughout the rest of Western philosophy too) there could be no such assurance that virtue would be crowned with happiness except to hope that God would make it so in the afterlife. By contrast, Mou was proud to say, Chinese philosophy provides for this “coincidence of virtue and happiness” without having to posit either a God or an afterlife. The argument for that assurance differed in Confucian, Buddhist, and Daoist versions of the perfect teaching, but in each case it consisted of a doctrine that intellectual intuition (equivalent to “virtue”) necessarily entails the existence of the phenomenal world (which Mou construed as the meaning of “happiness”), without being contingent on God’s intervention in this world or the next or on any condition other than the operation of intellectual intuition, which Mou considered available to all people at all times.

In arguing for the historical absence of such a solution to the problem of the perfect good anywhere outside of China, Mou did acknowledge that Epicurean and Stoic philosophers also tried to establish that virtue resulted in happiness, but he claimed that their explanations only worked by redefining either virtue or happiness in order to reduce its meaning to something analytically entailed by the other. However, some critics have argued that Mou’s alternative commits the same fault by effectively collapsing happiness into virtue.

4. Criticisms

Mou has often been accused of irrationalism due to his doctrine of the direct, supra-sensory intellectual intuition, which states that people can apprehend the deeper reality underlying the mere phenomena that are measured and described by scientific knowledge. Mou has also been ridiculed because he did not so much present positive arguments in favor of his main metaphysical beliefs as propound them as definitive facts, presumably known to him through a privileged access to sagely intuition.

Critics also frequently question the relevance of Mou’s philosophy, both to the Confucian tradition from which he took his inspiration, as well as to Chinese society. They point out that Mou’s thought (as well as that of other inheritors of Xiong Shili’s legacy in general) inhabits a far different social context than the Confucian tradition with which he identifies. With Mou and his generation, Chinese philosophy was detached from its old homes in the traditional schools of classical learning (shuyuan), the Imperial civil service, and monasteries and hermitages, and was transplanted into the new setting of the modern university, with its disciplinary divisions and limited social role. Critics point to this academicization as evidence that, despite Mou’s aspirations to kindle a massive revival of the Confucian spirit in China, his thought risks being little more than a “lost soul,” deracinated and intellectualized. The first problem with this, they claim, is that Mou reduces Confucianism to a philosophy in the modern academic sense and leaves out other important aspects of the pre-modern Confucian cultural system, such as its art, literature, and ritual and its political and career institutions. Second, they claim, because Mou’s brand of Confucianism accents metaphysics so heavily, it remains confined to departments of philosophy and powerless to exert any real influence over Chinese society.

Mou has also been criticized for his explicit essentialism. In keeping with his Hegelian tendency, he presented China as consisting essentially of Chinese culture, and even more particularly with Chinese philosophy, and he claimed in turn that this is epitomized by Confucian philosophy. Furthermore, he presents the Confucian tradition as consisting essentially of an idiosyncratic-looking list of Confucian thinkers. Opponents complain that even if there were good reasons for Mou to enshrine his handful of favorite Confucians as the very embodiment of all of Chinese culture, this would remain Mou’s opinion and nothing more, a mere interpretation rather than the objective, factual historical insight that Mou claimed it was.

5. Influence

In Mou’s last decades, he began to be recognized together with other prominent students of Xiong Shili as a leader of what came to be called the “New Confucian” (dangdai xin rujia) movement, which aspires to revive and modernize Confucianism as a living spiritual tradition. Through his many influential protégés, Mou achieved great influence over the agenda of contemporary Chinese philosophy.

Two of his early students, Liu Shu-hsien (b. 1934) and Tu Wei-ming (b. 1940) have been especially active in raising the profile of contemporary Confucianism in English-speaking venues, as has the Canadian-born scholar John Berthrong (b. 1946). Mou’s emphasis on Kant’s transcendental analytic gave new momentum to research on Kant and post-Kantians, particularly in the work of Mou’s student Lee Ming-huei (b. 1953), and his writings on Buddhism lie behind much of the interest in and interpretation of Tiantai philosophy among Chinese scholars. Finally, Mou functions as the main modern influence on, and point of reference for, the intense research on Confucianism among mainland Chinese philosophers today.

6. References and Further Reading

Angle, Stephen C. Sagehood: The Contemporary Significance of Neo-Confucian Philosophy. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Angle, Stephen C. Contemporary Confucian Political Philosophy. Cambridge: Polity, 2012.

Asakura, Tomomi. “On Buddhistic Ontology: A Comparative Study of Mou Zongsan and Kyoto School Philosophy.” Philosophy East and West 61/4 (October 2011): 647-678.

Berthrong, John. “The Problem of Mind: Mou Tsung-san’s Critique of Chu Hsi.” Journal of Chinese Religion 10 (1982): 367-394.

Berthrong, John. All Under Heaven. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994.

Billioud, Sébastien. “Mou Zongsan’s Problem with the Heideggerian Interpretation of Kant.” Journal of Chinese Philosophy 33/2 (June 2006): 225-247.

Billioud, Sébastien. Thinking through Confucian Modernity: A Study of Mou Zongsan’s Moral Metaphysics. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2011.

Bresciani, Umberto. Reinventing Confucianism: The New Confucian Movement. Taipei: Taipei Ricci Institute for Chinese Studies, 2001.

Bunnin, Nicholas. “God’s Knowledge and Ours: Kant and Mou Zongsan on Intellectual Intuition.” Journal of Chinese Philosophy 35/4 (December 2008): 613-624.

Chan, N. Serina. “What is Confucian and New about the Thought of Mou Zongsan?” in New Confucianism: A Critical Examination, ed. John Makeham (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), 131-164.

Chan, N. Serina. The Thought of Mou Zongsan. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2011.

Chan, Wing-Cheuk. “Mou Zongsan on Zen Buddhism.” Dao: A Journal of Comparative Philosophy 5/1 (2005) : 73-88.

Chan, Wing-Cheuk. “Mou Zongsan’s Transformation of Kant’s Philosophy.” Journal of Chinese Philosophy 33/1 (March 2006): 125-139.

Chan, Wing-Cheuk. “Mou Zongsan and Tang Junyi on Zhang Zai’s and Wang Fuzhi’s Philosophies of Qi : A Critical Reflection.” Dao: A Journal of Comparative Philosophy 10/1 (March 2011): 85-98.

Chan, Wing-Cheuk. “On Mou Zongsan’s Hermeneutic Application of Buddhism.” Journal of Chinese Philosophy 38/2 (June 2011): 174-189.

Chan, Wing-Cheuk and Henry C. H. Shiu. “Introduction: Mou Zongsan and Chinese Buddhism.” Journal of Chinese Philosophy 38/2 (June 2011): 169-173.

Clower, Jason. The Unlikely Buddhologist: Tiantai Buddhism in the New Confucianism of Mou Zongsan. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2010.

Clower, Jason. “Mou Zongsan on the Five Periods of the Buddha’s Teaching. Journal of Chinese Philosophy 38/2 (June 2011): 190-205.

Guo Qiyong. “Mou Zongsan’s View of Interpreting Confucianism by ‘Moral Autonomy’.” Frontiers of Philosophy in China 2/3 (June 2007): 345-362.

Kantor, Hans-Rudolf. “Ontological Indeterminacy and Its Soteriological Relevance: An Assessment of Mou Zongsan’s (1909-1995) Interpretation of Zhiyi’s (538-597) Tiantai Buddhism.” Philosophy East and West 56/1 (January 2006): 16-68.

Kwan, Chun-Keung. “Mou Zongsan’s Ontological Reading of Tiantai Buddhism.” Journal of Chinese Philosophy 38/2 (June 2011): 206-222.

Lin, Chen-kuo. “Dwelling in Nearness to the Gods: The Hermeneutical Turn from MOU Zongsan to TU Weiming.” Dao 7 (2008): 381-392.

Lin, Tongqi and Zhou Qin. “The Dynamism and Tension in the Anthropocosmic Vision of Mou Zongsan.” Journal of Chinese Philosophy 22/4 (December 1995): 401-440.

Liu, Shu-hsien. “Mou Tsung-san (Mou Zongsan)” in Encyclopedia of Chinese Philosophy, ed. A.S. Cua. New York: Routledge, 2003.

Mou, Tsung-san [Mou Zongsan]. “The Immediate Successor of Wang Yang-ming: Wang Lung-hsi and his Theory of Ssu-wu.” Philosophy East and West 23/1-2 (1973): 103-120.

Neville, Robert C. Boston Confucianism: Portable Tradition in the Late-Modern World. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2000.

Stephan Schmidt. “Mou Zongsan, Hegel, and Kant: The Quest for Confucian Modernity.” Philosophy East and West 61/2 (April 2011): 260-302.

Shiu, Henry C.H. “Nonsubstantialism of the Awakening of Faith in Mou Zongsan.” Journal of Chinese Philosophy 38/2 (June 2011): 223-237.

Tang, Andres Siu-Kwong. “Mou Zongsan’s ‘Transcendental’ Interpretation of Huayan Buddhism.” Journal of Chinese Philosophy 38/2 (June 2011): 238-256.

Tu, Wei-ming. Centrality and Commonality: An Essay on Confucian Religiousness. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1989.

Tu, Xiaofei. “Dare to Compare: The Comparative Philosophy of Mou Zongsan.” Kritike 1/2 (December 2007): 24-35.

Zheng Jiadong. “Mou Zongsan and the Contemporary Circumstances of the Rujia.” Contemporary Chinese Thought 36/2 (Winter 2004-5): 67-88.

Zheng Jiadong. “Between History and Thought: Mou Zongsan and the New Confucianism That Walked Out of History.” Contemporary Chinese Thought 36/2 (Winter 2004-5): 49-66.

Author Information

Jason Clower

Email: [email protected]

California State University, Chico

U. S. A.