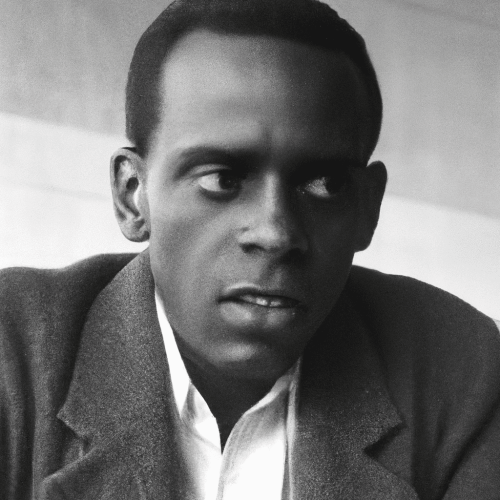

Frantz Fanon (1925—1961)

Frantz Fanon was one of a few extraordinary thinkers supporting the decolonization struggles occurring after World War II, and he remains among the most widely read and influential of these voices. His brief life was notable both for his whole-hearted engagement in the independence struggle the Algerian people waged against France and for his astute, passionate analyses of the human impulse towards freedom in the colonial context. His written works have become central texts in Africana thought, in large part because of their attention to the roles hybridity and creolization can play in forming humanist, anti-colonial cultures. Hybridity, in particular, is seen as a counter-hegemonic opposition to colonial practices, a non-assimilationist way of building connections across cultures that Africana scholar Paget Henry argues is constitutive of Africana political philosophy.

Tracing the development of his writings helps explain how and why he has become an inspirational figure firing the moral imagination of people who continue to work for social justice for the marginalized and the oppressed. Fanon’s first work Peau Noire, Masques Blancs (Black Skin, White Masks) was his first effort to articulate a radical anti-racist humanism that adhered neither to assimilation to a white-supremacist mainstream nor to reactionary philosophies of black superiority. While the attention to oppression of colonized peoples that was to dominate his later works was present in this first book, its call for a new understanding of humanity was undertaken from the subject-position of a relatively privileged Martinican citizen of France, in search of his own place in the world as a black man from the French Caribbean, living in France. His later works, notably L’An Cinq, de la Révolution Algérienne (A Dying Colonialism) and the much more well-known Les Damnés de la Terre (The Wretched of the Earth), go beyond a preoccupation with Europe’s pretensions to being a universal standard of culture and civilization, in order to take on the struggles and take up the consciousness of the colonized “natives” as they rise up and reclaim simultaneously their lands and their human dignity. It is Fanon’s expansive conception of humanity and his decision to craft the moral core of decolonization theory as a commitment to the individual human dignity of each member of populations typically dismissed as “the masses” that stands as his enduring legacy.

Table of Contents

Biography

Africana Phenomenology

Decolonization Theory

Influences on Fanon’s Thought

Movements and Thinkers Influenced by Fanon

References and Further Reading

Primary Sources

Secondary Sources

1. Biography

Frantz Fanon was born in the French colony of Martinique on July 20, 1925. His family occupied a social position within Martinican society that could reasonably qualify them as part of the black bourgeoisie; Frantz’s father, Casimir Fanon, was a customs inspector and his mother, Eléanore Médélice, owned a hardware store in downtown Fort-de-France, the capital of Martinique. Members of this social stratum tended to strive for assimilation, and identification, with white French culture. Fanon was raised in this environment, learning France’s history as his own, until his high school years when he first encountered the philosophy of negritude, taught to him by Aimé Césaire, Martinique’s other renowned critic of European colonization. Politicized, and torn between the assimilationism of Martinique’s middle class and the preoccupation with racial identity that negritude promotes, Fanon left the colony in 1943, at the age of 18, to fight with the Free French forces in the waning days of World War II.

After the war, he stayed in France to study psychiatry and medicine at university in Lyons. Here, he encountered bafflingly simplistic anti-black racism—so different from the complex, class-permeated distinctions of shades of lightness and darkness one finds in the Caribbean—which would so enrage him that he was inspired to write “An Essay for the Disalienation of Blacks,” the piece of writing that would eventually become Peau Noire, Masques Blancs (1952). It was here too that he began to explore the Marxist and existentialist ideas that would inform the radical departure from the assimilation-negritude dichotomy that Peau Noire’s anti-racist humanism inaugurates.

Although he briefly returned to the Caribbean after he finished his studies, he no longer felt at home there and in 1953, after a stint in Paris, he accepted a position as chef de service (chief of staff) for the psychiatric ward of the Blida-Joinville hospital in Algeria. The following year, 1954, marked the eruption of the Algerian war of independence against France, an uprising directed by the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) and brutally repressed by French armed forces. Working in a French hospital, Fanon was increasingly responsible for treating both the psychological distress of the soldiers and officers of the French army who carried out torture in order to suppress anti-colonial resistance and the trauma suffered by the Algerian torture victims. Already alienated by the homogenizing effects of French imperialism, by 1956 Fanon realized he could not continue to aid French efforts to put down a decolonization movement that commanded his political loyalties, and he resigned his position at the hospital.

Once he was no longer officially working for the French government in Algeria, Fanon was free to devote himself to the cause of Algerian independence. During this period, he was based primarily in Tunisia where he trained nurses for the FLN, edited its newspaper el Moujahid, and contributed articles about the movement to sympathetic publications, including Presence Africaine and Jean-Paul Sartre’s journal Les Temps Modernes. Some of Fanon’s writings from this period were published posthumously in 1964 as Pour la Révolution Africaine (Toward the African Revolution). In 1959 Fanon published a series of essays, L’An Cinq, de la Révolution Algérienne, (The Year of the Algerian Revolution) which detail how the oppressed natives of Algeria organized themselves into a revolutionary fighting force. That same year, he took up a diplomatic post in the provisional Algerian government, ambassador to Ghana, and used the influence of this position to help open up supply routes for the Algerian army. It was in Ghana that Fanon was diagnosed with the leukemia that would be his cause of death. Despite his rapidly failing health, Fanon spent ten months of his last year of life writing the book for which he would be most remembered, Les Damnés de la Terre, an indictment of the violence and savagery of colonialism which he ends with a passionate call for a new history of humanity to be initiated by a decolonized Third World. In October 1961, Fanon was brought to the United States by a C.I.A. agent so that he could receive treatment at a National Institutes of Health facility in Bethesda, Maryland. He died two months later, on December 6, 1961, reportedly still preoccupied with the cause of liberty and justice for the peoples of the Third World. At the request of the FLN, his body was returned to Tunisia, where it was subsequently transported across the border and buried in the soil of the Algerian nation for which he fought so single-mindedly during the last five years of his life.

2. Africana Phenomenology

Fanon’s contribution to phenomenology, glossed as a critical race discourse (an analysis of the pre-conscious forces shaping the self that organizes itself around race as a founding category), most particularly his exploration of the existential challenges faced by black human beings in a social world that is constituted for white human beings, receives its most explicit treatment in Peau Noire, Masques Blancs. The central metaphor of this book, that black people must wear “white masks” in order to get by in a white world, is reminiscent of W.E.B. Du Bois’ argument that African Americans develop a double consciousness living under a white power structure: one that flatters that structure (or some such) and one experienced when among other African Americans. Fanon’s treatment of the ways black people respond to a social context that racializes them at the expense of our shared humanity ranges across a broader range of cultures than Du Bois, however; Fanon examines how race shapes (deforms) the lives of both men and women in the French Caribbean, in France, and in colonial conflicts in Africa. Africana sociologist Paget Henry characterizes Fanon’s relation to Du Bois in the realm of phenomenology as one of extension and of clarification, since he offers a more detailed investigation of how the self encounters the trauma of being categorized by others as inferior due to an imposed racial identity and how that self can recuperate a sense of identity and a cultural affiliation that is independent of the racist project of an imperializing dominant culture.

Fanon dissects in all of his major works the racist and colonizing project of white European culture, that is, the totalizing, hierarchical worldview that needs to set up the black human being as “negro” so it has an “other” against which to define itself. While Peau Noire offers a sustained discussion of the psychological dimensions of this “negrification” of human beings and possibilities of resistance to it, the political dimensions are explored in L’An Cinq, de la Révolution Algérienne and Les Damnés de la Terre. Fanon’s diagnosis of the psychological dimensions of negrification’s phenomenological violence documents its traumatizing effects: first, negrification promotes negative attitudes toward other blacks and Africa; second, it normalizes attitudes of desire and debasement toward Europe, white people, and white culture in general; and finally, it presents itself as such an all-encompassing way of being in the world that no other alternative appears to be possible. The difficulty of overcoming the sense of alienation that negrification sets up as necessary for the black human being lies in learning to see oneself not just as envisioned and valued (that is, devalued) by the white dominant culture but simultaneously through a perspective constructed both in opposition to and independently from the racist/racialized mainstream, a parallel perspective in which a black man or woman’s value judgments—of oneself and of others of one’s race—do not have to be filtered through white norms and values. It is only through development of this latter perspective that the black man or woman can shake off the psychological colonization that racist phenomenology imposes, Fanon argues.

One of the most pervasive agents of phenomenological conditioning is language. In Peau Noire, Fanon analyzes language as that which carries and reveals racism in culture, using as an example the symbolism of whiteness and blackness in the French language—a point that translates equally well into English linguistic habits. One cannot learn and speak this language, Fanon asserts, without subconsciously accepting the cultural meanings embedded in equations of purity with whiteness and malevolence with blackness: to be white is to be good, and to be black is to be bad. While Peau Noire focuses on the colonizing aspects of the French language, L’An Cinq, on the other hand, offers an interesting account of how language might enable decolonization efforts. Fanon describes a decision made by the revolutionary forces in Algeria in 1956 to give up their previous boycott of French and instead start using it as the lingua franca that could unite diverse communities of resistance, including those who did not speak Arabic. The subversive effects of adopting French extended beyond the convenience of a common language; it also cast doubt on the simplistic assumption the French colonizers had been making, namely, that all French speakers in Algeria were loyal to the colonial government. After strategically adopting the colonizer’s language, one entered a shop or a government office no longer necessarily announcing one’s politics in one’s choice of language.

Fanon’s critical race phenomenology is not without its critics, many of whom read Peau Noire’s back-to-back accounts of the black woman’s desire for a white lover and the black man’s desire for a white lover as misogynistic. According to these critiques, typically offered from a feminist point of view, the autobiography of Mayotte Capécia, a Martinican woman who seeks the love of a white man, any white man it seems, is treated by Fanon (who describes it as “cut-rate” and “ridiculous”) with far less respect than the novel by René Maran, which describes the story of Jean Veneuse, a black man who reluctantly falls in love with a white Frenchwoman and hesitates to marry her until he is urged to do so by her brother. Although Fanon is unequivocal in his statement that both of these discussions serve as examples of “alienated psyches,” white feminists who make this charge of misogyny point to his less sympathetic account of Capécia as evidence that he holds black women complicit in the devaluing of blackness. Where it is found at all in the work of black feminist writers, this allegation tends to be more tentative, and tends to be contextualized within a pluralist inventory of phenomenological approaches. Just as Fanon selects race as the founding category of phenomenology, a feminist phenomenology would focus on gender as a founding category. In this pluralist framework, Fanon’s attention to race at the expense of gender is arguably more explicable as a methodological choice than a deep-seated contempt for women.

3. Decolonization Theory

The political dimensions of negrification that call for decolonization receive fuller treatment in L’An Cinq, de la Révolution Algérienne and Les Damnés de la Terre. But Fanon does not simply diagnose the political symptoms of the worldview within which black men and women are dehumanized. He situates his diagnosis within an unambiguous ethical commitment to the equal right of every human being to have his or her human dignity recognized by others. This assertion, that all of us are entitled to moral consideration and that no one is dispensable, is the principled core of his decolonization theory, which continues to inspire scholars and activists dedicated to human rights and social justice.

As the French title suggests, L’An Cinq (published in English as A Dying Colonialism) is Fanon’s first-hand account of how the Algerian people mobilized themselves into a revolutionary fighting force and repelled the French colonial government. The lessons that other aspiring revolutionary movements can learn from Fanon’s presentation of the FLN’s strategies and tactics are embedded in their particular Algerian context, but nonetheless evidently adaptable. In addition to describing the FLN’s strategic adoption of French as the language of communication with its sympathetic civilian population, Fanon also traces the interplay of ideological and pragmatic choices they made about communications technology. Once the French started suppressing newspapers, the FLN had to rethink their standing boycott of radios, which they had previously denounced as the colonizer’s technology. This led to the creation of a nationalist radio station, the Voice of Fighting Algeria, that now challenged colonial propaganda with what Fanon described as “the first words of the nation.” Another of the fundamental challenges they issued to the colonial world of division and hierarchy was the radically inclusive statement the provisional government made that all people living in Algeria would be considered citizens of the new nation. This was a bold contestation of European imperialism on the model of Haiti’s first constitution (1805), which attempted to break down hierarchies of social privilege based on skin color by declaring that all Haitian citizens would be considered black. Both the Algerian and Haitian declarations are powerful decolonizing moves because they undermine the very Manichean structure that Fanon identifies as the foundation of the colonial world.

While L’An Cinq offers the kinds of insights one might hope for from a historical document, Les Damnés de la Terre is a more abstract analysis of colonialism and revolution. It has been described as a handbook for black revolution. The book ranges over the necessary role Fanon thinks violence must play in decolonization struggles, the false paths decolonizing nations take when they entrust their eventual freedom to negotiations between a native elite class and the formers colonizers instead of mobilizing the masses as a popular fighting force, the need to recreate a national culture through a revolutionary arts and literature movement, and an inventory of the psychiatric disorders that colonial repression unleashes. Part of its shocking quality, from a philosophical perspective, is alluded to in the preface that Jean-Paul Sartre wrote for the book: it speaks the language of philosophy and deploys the kind of Marxist and Hegelian arguments one might expect in a philosophy of liberation, but it does not speak to the West. It is Fanon conversing with, advising, his fellow Third-World revolutionaries.

The controversy that swirls around Les Damnés is very different from the one Peau Noire attracts. Where feminist critiques of Peau Noire require a deep reading and an analysis of the kinds of questions Fanon failed to ask, those who find fault with Les Damnés for what they see as its endorsement of violent insurgency are often reading Fanon’s words too simplistically. His argument is not that decolonizing natives are justified in using violent means to effect their ends; the point he is making in his opening chapter, “Concerning Violence,” is that violence is a fundamental element of colonization, introduced by the colonizers and visited upon the colonized as part of the colonial oppression. The choice concerning violence that the colonized native must make, in Fanon’s view, is between continuing to accept it—absorbing the abuse or displacing it upon other members of the oppressed native community—or taking this foreign violence and throwing it back in the face of those who initiated it. Fanon’s consistent existentialist commitment to choosing one’s character through one’s actions means that decolonization can only happen when the native takes up his or her responsible subjecthood and refuses to occupy the position of violence-absorbing passive victim.

4. Influences on Fanon’s Thought

The first significant influence on Fanon was the philosophy of negritude to which he was introduced by Aimé Césaire. Although this philosophy of black pride was a potent counterbalance to the assimilation tendencies into which Fanon had been socialized, it was ultimately an inadequate response to an imperializing culture that presents itself as a universal worldview. Far more fruitful, in Fanon’s view, were his studies in France of Hegel, Marx, and Husserl. From these sources he developed the view that dialectic could be the process through which the othered/alienated self can respond to racist trauma in a healthy way, a sensitivity to the social and economic forces that shape human beings, and an appreciation for the pre-conscious construction of self that phenomenology can reveal. He also found Sartre’s existentialism a helpful resource for theorizing the process of self construction by which each of us chooses to become the persons we are. This relation with Sartre appears to have been particularly mutually beneficial; Sartre’s existentialism permeates Peau Noire and in turn, Sartre’s heartfelt and radical commitment to decolonization suggests that Fanon had quite an influence on him.

5. Movements and Thinkers Influenced by Fanon

The pan-Africanism that Fanon understood himself to be contributing to in his work on behalf of Third World peoples never really materialized as a political movement. It must be remembered that in Fanon’s day, the term “Third World” did not have the meaning it has today. Where today it designates a collection of desperately poor countries that are the objects of the developed world’s charity, in the 1950s and 1960s, the term indicated the hope of an emerging alternative to political alliance with either the First World (the United States and Europe) or the Second World (the Soviet bloc). The attempt to generate political solidarity and meaningful political power among the newly independent nations of Africa instead foundered as these former colonies fell victim to precisely the sort of false decolonization and client-statism that Fanon had warned against. Today, as a political program, that ideal of small-state solidarity survives only in the leftist critiques of neoliberalism offered by activists like Noam Chomsky and Naomi Klein.

Instead, the discourse of solidarity and political reconstruction has retreated into the academy, where it is theorized as “postcolonialism.” Here we find the critical theorizing of scholars like Edward Said and Gayatri Spivak, both of whom construct analyses of the colonial Self and the colonized Other that, implicitly at least, depend on the Manichean division that Fanon presents in Les Damnés.

Thinkers around the globe have been profoundly influenced by Fanon’s work on anti-black racism and decolonization theory. Brazilian theorist of critical pedagogy Paulo Freire engages Fanon in dialogue in Pedagogy of the Oppressed, notably in his discussion of the mis-steps that oppressed people may make on their path to liberation. Freire’s emphasis on the need to go beyond a mere turning of the tables, a seizure of the privileges and social positions of the oppressors, echoes Fanon’s concern in Les Damnés and in essays such as “Racism and Culture” (in Pour la Révolution Africaine) that failure to appreciate the deeply Manichean structure of the settler-native division could lead to a false decolonization in which a native elite simply replace the settler elite as the oppressive rulers of the still exploited masses. This shared concern is the motivation for Freire’s insistence on perspectival transformation and on populist inclusion as necessary conditions for social liberation.

Kenyan author and decolonization activist Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o also draws on ideas Fanon presents in Les Damnés. Inspired mainly by Fanon’s meditations on the need to decolonize national consciousness, Ngũgĩ has written of the need to get beyond the “colonization of the mind” that occurs in using the language of imposed powers. Like Fanon, he recognizes that language has a dual character. It colonizes in the sense that power congeals in the history of how language is used (that is, its role in carrying culture). But it can also be adapted to our real-life communication and our “image-forming” projects, which means it also always carries the potential to be the means by which we liberate ourselves. Ngũgĩ’s last book in English, Decolonizing the Mind, was his official renunciation of the colonizer’s language in favor of his native tongue, Gĩkũyũ, and its account of the politics of language in African literature can fruitfully be read as an illustration of the abstract claims Fanon makes about art and culture in Les Damnés and Pour la Révolution Africaine.

Maori scholar Linda Tuhiwai Smith takes up Fanon’s call for artists and intellectuals of decolonizing societies to create new literatures and new cultures for their liberated nations. Applying Fanon’s call to her own context, Tuhiwai Smith notes that Maori writers in New Zealand have begun to produce literature that reflects and supports a resurgent indigenous sovereignty movement, but she notes that there is little attention to achieving that same intellectual autonomy in the social sciences. Inspired by Fanon’s call to voice, she has written Decolonizing Methodologies, a book that interrogates the way “research” has been used by European colonial powers to subjugate indigenous peoples and also lays out methodological principles for indigenous research agendas that will not reproduce the same dehumanizing results that colonial knowledge production has been responsible for

In the United States, Fanon’s influence continues to grow. Feminist theorist bell hooks, one of those who notes the absence of attention to gender in Fanon’s work, nonetheless acknowledges the power of his vision of the resistant decolonized subject and the possibility of love that this vision nurtures. Existential phenomenologist Lewis R. Gordon works to articulate the new humanism that Fanon identified as the goal of a decolonized anti-racist philosophy. Gordon is one of the Africana–and Caribbean–focused scholars in American academia who has been involved in founding today’s most prominent Africana-Caribbean research network, the Caribbean Philosophical Association, which awards an annual book prize in Frantz Fanon’s name. The Frantz Fanon Prize recognizes excellence in scholarship that advances Caribbean philosophy and Africana-humanist thought in the Fanonian tradition.

In Paris, the heart of the former empire that Fanon opposed so vigorously in his short life, his philosophy of humanist liberation and his commitment to the moral relevance of all people everywhere have been taken up by his daughter Mireille Fanon. She heads the Fondation Frantz Fanon and follows in her father’s footsteps with her work on questions of international law and human rights, supporting the rights of migrants, and championing struggles against the impunity of the powerful and all forms of racism.

6. References and Further Reading

a. Primary Sources

Fanon, Frantz. L’An Cinq, de la Révolution Algérienne. Paris: François Maspero, 1959. [Published in English as A Dying Colonialism, trans. Haakon Chevalier (New York: Grove Press, 1965).]

Fanon, Frantz. Les Damnés de la Terre. Paris: François Maspero, 1961. [Published in English as The Wretched of the Earth, trans. Constance Farrington (New York: Grove Press, 1965).]

Fanon, Frantz. Peau Noire, Masques Blancs. Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1952. [Published in English as Black Skin, White Masks, trans. Charles Lam Markmann (New York: Grove Press, 1967).]

Fanon, Frantz. Pour la Révolution Africaine. Paris: François Maspero, 1964. [Published in English as Toward the African Revolution, trans. Haakon Chevalier (New York: Grove Press, 1967).]

b. Secondary Sources

Cherki, Alice. Frantz Fanon: A Portrait. Trans. Nadia Benabid. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2006.

A biography of Fanon by one of his co-workers at the Blida-Joinville hospital in Algeria and fellow activists for Algerian liberation.

Gibson, Nigel C. Fanon: The Postcolonial Imagination. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2003.

An introduction to Fanon’s ideas with emphasis on the role that dialectic played in his development of a philosophy of liberation.

Gibson, Nigel C. (ed.). Rethinking Fanon: The Continuing Dialogue. Amherst, NY: Humanity Books, 1999.

A collection of some of the enduring essays on Fanon, with attention to his continuing relevance.

Gordon, Lewis R. Fanon and the Crisis of European Man: An Essay on Philosophy and the Human Sciences. New York: Routledge, 1995.

An argument in the Fanonian vein that bad faith in European practice of the human sciences has impeded the inclusive humanism Fanon called for.

Gordon, Lewis R., T. Denean Sharpley-Whiting, and Renée T. White (eds.). Fanon: A Critical Reader. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1996.

Essays on Africana philosophy, neocolonial and postcolonial studies, human sciences, and other academic discourses that place Fanon’s work in its appropriate and illuminating contexts.

Hoppe, Elizabeth A. and Tracey Nicholls (eds.). Fanon and the Decolonization of Philosophy. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2010.

Essays by contemporary Fanon scholars exploring the enduring relevance to philosophy of Fanon’s thought.

Sekyi-Out, Ato. Fanon’s Dialectic of Experience. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996.

A hermeneutic reading of all of Fanon’s texts as a single dialectical narrative.

Zahar, Renate. Frantz Fanon: Colonialism and Alienation. New York: Monthly Review Press, 1974.

An analysis of Fanon’s writings through the concept of alienation.

Author Information

Tracey Nicholls

Email: [email protected]

Lewis University

U. S. A.