Dothraki Relative Clause Structure

Author: Caroline Elizabeth Melton

MS Date: 09-05-2019

FL Date: 02-01-2020

FL Number: FL-000065-00

Citation: Melton, Caroline Elizabeth. 2019. “Dothraki

Relative Clause Structure.” FL-000065-00,

Fiat Lingua,

February 2020.

Copyright: © 2019 Caroline Elizabeth Melton. This work is

licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

Fiat Lingua is produced and maintained by the Language Creation Society (LCS). For more information

about the LCS, visit http://www.conlang.org/

Stony Brook University

Dothraki as a Naturalistic Language

Evaluating HBO’s Game of Thrones’ Dothraki Case System and Relative Clauses

using Real World Analogs and Minimalist Syntax

Caroline Elizabeth Melton

LIN Comparative Analysis

Dr. Francisco Ordoñez

18 May 2014

Melton 1

“A naturalistic language is one that attempts as nearly

as possible to imitate the quirks and idiosyncrasies of natural language.”

David Peterson on developing Dothraki, 2013

Introduction

Since the Elvish of Tolkien’s Middle Earth and the Klingon of Roddenberry’s Enterprise-traveled stars, authors and

directors have sought constructed languages (conlangs) to give their fictional universes an added element of

realism. As the Internet grows, it continues to foster intense fandom of TV shows, movies, books and other

fantasy media, these fans find it increasingly tempting to immerse themselves in the worlds they love to watch and

read about, and this includes the languages of the characters. Within the last decade, Hollywood has taken

advantage of this fervor, having employed linguists for the purpose of making languages for their actors to speak

on camera and their fans to learn. One of the most notable of these linguists is David J. Peterson, a UC San Diego-

trained linguist who was hired by HBO’s Game of Thrones to create the languages described in the show’s source,

George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series, most notably Dothraki.1 While Martin’s original material was

lean, Peterson was able to create a fully usage language whose grammar he describes as “naturalistic” (“David

Peterson on developing Dothraki,” 2013). As a hobbyist who ascribes to create naturalistic languages, as a fan of

Game of Thrones, and as a student of linguistics, I am interested in objectively evaluating Dothraki as a naturalistic

language.

What is Naturalistic Language?

Peterson defines a naturalistic conlang as “one that attempts as nearly as possible to imitate the quirks and

idiosyncrasies of natural language.” (2013) In an attempt to find criteria with which to evaluate such behavior, an

objective analysis should start by comparing a grammar to the Universal Grammar (UG) (1a). However, linguists do

1 Peterson has since worked on several other languages on HBO’s Game of Thrones as well as on Syfy’s Defiance and Dominion,

on CW’s Star-Crossed, and for the novel The Zaanics Deceit by Nina Post. He has been independently conlanging since 2000.

(“About David J. Peterson,” 2013).

Melton 2

not have direct access to the UG. We can use in its stead the Greenberg linguistic universals. Greenberg (1963)

proposed a list of common properties by comparing the grammars of 30 languages. Referred to as Greenberg’s

linguistic universals, they number 1-45 and reflect what Greenberg hypothesized to be rules that natural language

cannot violate. For a more general evaluation, we might aim to compare the conlang to natural languages (1b) with

the conclusion that a natural language cannot exhibit behavior that violates the UG.

(1) A naturalistic conlang is one

a.

that obeys the Universal Grammar (UG).

b. whose behavior has analogs in natural language.

In studying natural languages, data can be acquired from real speakers, native or otherwise. While there are

speakers of Dothraki, they would be neither native speakers nor undeniably fluent and thus, that cannot be collected

in the same manner as a natural and living language. Fans of TV shows, book, and other media use the canon

convention in such circumstances. Information about storylines, histories, characters, and conlangs that is derived

from the original work is considered canon (short for canonical),2 and conversely fan-made derivations and official

but peripheral works (e.g. fan-written work and some movie tie-ins) are not canon. In place of real-world data, I

have adopted this convention where the relevant canon is what has been released by HBO’s Game of Thrones or

Peterson himself (via his blog Dothraki.com) as official. Only canonical Dothraki with be discussed in the analysis.

Gender, Number, and Case Systems

Dothraki nouns have one of two genders: animate and inanimate. While a noun’s gender can sometimes correlate

with grammatical animacy, this is not a reliable indicator. For example, while the animacy of ave ‘father’ and chifti

‘locust’ might be predicted, chiorikem ‘wife’ and hrazef ‘horse’ are inanimate. Although vizhadi ‘silver’ is inanimate,

so is mawizzi ‘rabbit’. As with natural language gender, the animate/inanimate distinction is lexical and not driven

by semantics. Gender affects the inflection the noun will take, where animate nouns inflect for case3 and number,

2 This convention derives from Biblical canon: the distinction between the books of the Bible commonly considered

sacred (the canon) and those that are attested to be false, misleading, or fraudulent (the Apocrypha).

3 The five cases in Dothraki are Nominative, Accusative, Genitive, Allative, and Ablative. These are discussed

further below.

but inanimate nouns only inflect for case (2). All adjectives, regardless of the gender of the noun they modify, inflect

for both case and number (3).

(2) The noun inflectional paradigms for verak ‘traveler’ and olta ‘hill.’ (Adapted from “Dothraki 101,” Peterson.)

Melton 3

Animate

Inanimate

Singular

Nominative

verak

Plural

veraki

Accusative

verakes

verakis

Genitive

veraki

Allative

verakoon

verakea

–

olta

olt

olti

oltaan

Ablative

verakoon

verakoa

oltoon

(3) The adjective inflectional paradigm for ivezh ‘wild.’ (Adapted from “Dothraki 101,” Peterson.)

Animate and Inanimate

Singular

ivezh

ivezha

Plural

ivezhi

Nominative

Accusative

Genitive

Allative

Ablative

Personal pronouns (4) reflect three persons and two numbers (singular and plural), which is consistent with

Greenberg’s 42nd linguistic universal (5). The second person have both familiar and formal forms, where the formal

form does not change depending on number. All of the personal pronouns inflect for cases.

(4) The personal pronoun inflectional paradigm. (Adapted from “Dothraki 101,” Peterson.)

First Person

Second Person

Third Person

Familiar

Formal

Singular

Plural

Singular Plural

Singular and Plural

Singular

Plural

Nominative

Accusative

Genitive

anha

anna

anni

kisha

kisha

kishi

yer

yera

yeri

yeri

yeri

Allative

anhaan

kishaan

yeraan

yerea

Ablative

anhoon

kishoon

yeroon

yeroa

shafka

shafka

shafki

shafkea

shafkoa

me

mae

mae

maan

moon

mori

mora

mori

morea

moroa

Melton 4

(5) Greenberg’s 42nd Linguistic Universal. (Greenberg, 1963.)

42. “All languages have pronominal categories involving at least three persons and two numbers.”

There is gender distinction in the third person singular; nominative 3rd person singular me is used for both animate

and inanimate antecendents. This is a violation of Greenberg’s 43rd linguistic universal, which states that

languages maintain a hierarchy of gender distinctions in nominals (6).

(6) Greenberg’s 43rd Linguistic Universal. (Greenberg, 1963.)

43. “If a language has gender categories in the noun, it has gender categories in the pronoun.”

Dothraki nominals inflect for five cases: nominative, accusative, genitive, allative, and ablative. Nominative is

assigned to the subjects of independent clauses (7a). Accusative is generally given to objects (7b), genitive to

possessors of nominals (7c), allative generally to thematic goals (7d), and ablative generally to thematic origins (7e).

(7) Nouns inflected for the five Dothaki cases. (Adapted from “Athchomar Chomakea!,” Peterson 2012.)

a.

Jan-o

dog-NOM.INA

‘The dog bit the horse.’

hrazef

ost

bite[PST] horse[ACC.INA]

b. Hrazef

horse[NOM.INA]

‘The horse bit the dog.’

ost

jan

bite[PST] dog[ACC. INA]

c.

d.

e.

lajak-i

Jan-o

warrior-GEN.ANI

dog-NOM. INA

‘The warrior’s dog bit the horse.’

hrazef

ost

bite[PST] horse[ACC.INA]

jad-aki

Kisha

1[PL.NOM] come-1PL.PRES

‘We come from the mountain(s).’

krazaaj-oon

mountain-ABL.INA

Kisha ver-aki

1[PL.NOM] travel-1PL.PRES

‘We are traveling to the mountain(s).’

krazaaj-aan

mountain-ALL.INA

In the example (7) above, the nominative jano ‘dog’ has a morpheme that the accusative jan ‘dog’ does not. The

nominative appears to carry inflection while the accusative has a null inflection. This is true for all accusative

Melton 5

inanimate nouns (as seen in 2 above). This paradigm violates Greenberg’s 38th linguistic universal (8) which notes

that if case systems have null case markers, they mark the nominative case.

(8) Greenberg’s 38th Linguistic Universal. (Greenberg, 1963.)

38. “Where there is a case system, the only case which ever has only zero allomorphs is the one which

includes among its meanings that of the subject of the intransitive verb.”

The Dothraki case system itself (nominative, accusative, genitive, allative, and ablative) appears to violate a tendency

noted by Blake (1994) where languages maintain a hierarchy of case (9). Dothraki has no dative case yet it has

ablative. It has no instrumental or vocative, yet has the allative. Either Dothraki does not follow this hierarchy and

is not naturalistic, or its existing cases are mislabeled and really behave more the conventional dative and

locative/prepositional cases.

(9) Blake’s Hierarchy of Case. (Blake, 1994.)

Nominative à accusative/ergative à genitive à dative à locative/prepositional à ablative à

instrumental à vocative à others

Syntax of Case-Marked Relative Clauses

Relative clause formation offers many cross-linguistic variations. Most languages can relativize the subject of a

clause, fewer can relative the object, and still fewer can relativize other relations to the verb like thematic

instruments, goals and origins. English allows relativizations on all of these structures (10).

(10) English Relative Clause Structures.

Nominative/subject

‘The dog that bit the horse’

Accusative/object

‘The dog that the horse bit’

Genitive/possessor

‘The warrior whose dog bit the horse’

Allative/goal

‘The mountain that we travel to’

Ablative/origin

‘The mountain that we come from’

Melton 6

English relative clauses move the noun being relativized and the remaining information usually retains the order of

the independent clauses. The same is true in Dothraki (11), whose independent clause structure is SVO like English

(12). The result is that Dothraki relative clauses have a structure that looks like English (13). The subject of the

relative clause moves first to spec of TP and then out of the relative clause and into the head of the commanding

phrase. This internal movement is consistent with the independent clause structure as should be expected (14). The

movement out of the phrase triggers nominal marking on the clause relativizer fin ‘that/which’ which allows the

subject which has been relative to bare the case it receives in the matrix clause.

(11) An independent clause Dothraki. (Adapted from “Relative Clauses in Dothraki,” Peterson 2011.)

Mahrazh

warrior[NOM.ANI]

‘The warrior saw me.’

anna

tih

see[PST] 1[SG.ACC]

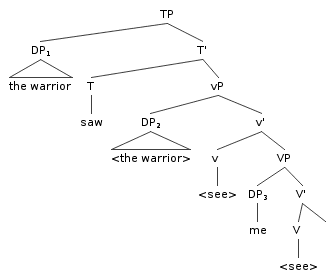

(12) Independent clause structure in English and Dothraki. (Adapted from “Relative Clauses in Dothraki,”

Peterson 2011.)

‘The warrior saw me’

(13) A subject relative clause in Dothraki. (Adapted from “Relative Clauses in Dothraki,” Peterson 2011.)

Mahrazh

warrior[ANI]

‘The warrior that saw me’

fin

that[SG.NOM.ANI]

anna

tih

see[PST] 1[SG.ACC]

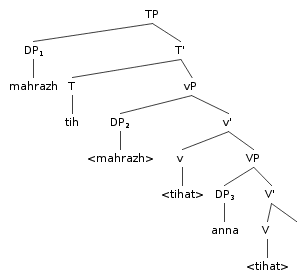

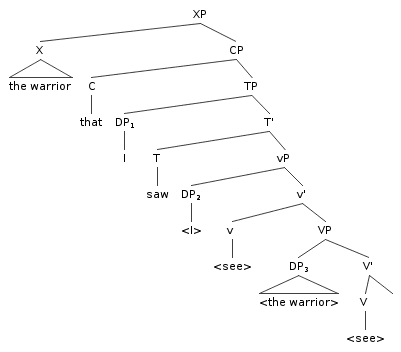

(14) Subject (nominative) relativization in English and Dothraki. (Adapted from “Relative Clauses in Dothraki,”

Peterson 2011.)

‘The warrior that saw me’

Melton 7

Accusative-marked objects may be relativized in English. In doing so, the internal structure of the relative clause

remains in place and only the object moves out into the matrix clause (15). Both the relative clause and the matrix

clause orders remain SVO.

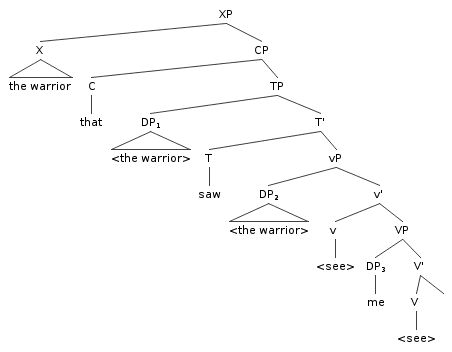

(15) Object (accusative) relativization in English.

‘The warrior that I saw’

In the fictional history of the Dothraki language, historical Dothraki was VSO. As it changed to a SVO structure in the

independent clauses, it retained the historical VSO structure in the relative clauses (“Relative Clauses in Dothraki,”

2011). As a result, when objects are relativized, the clause structure is different from that of the subject structure

Melton 8

(16) and its movement is inconsistent with minimalist syntactic structures. Such a system where movement in an

independent clause results in SVO order but within the relative clause, either the subject’s movement is restricted

(17a) or the verb is forced to move to a spec of XP between CP and TP (17b) is has no know analog in natural language.

The behavior can therefore be considered unnaturalistic.

(16) A subject relative clause in Dothraki. (Adapted from “Relative Clauses in Dothraki,” Peterson 2011.)

Mahrazh

warrior[ANI]

‘The warrior that I saw’

fines

that[SG.ACC.ANI]

anha

tih

see[PST] 1[SG.NOM]

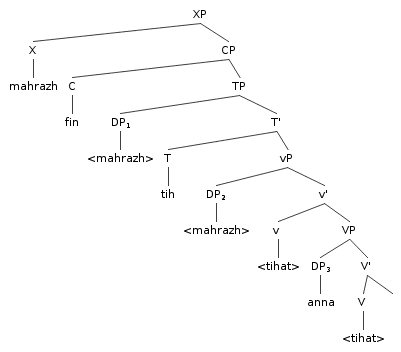

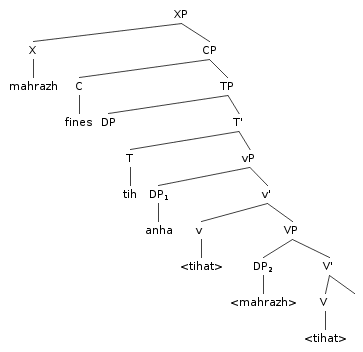

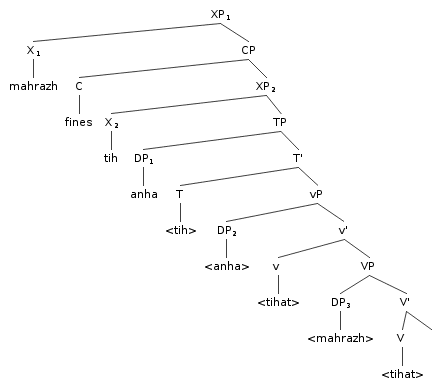

(17) Two hypotheses of object (accusative) relativization in Dothraki. The leftmost tree (a) disallows internal

movement of the subject of the relative clause to spec of TP. The rightmost tree (b) forces the verb of the

relative clause to move up from T to somewhere between CP and TP. (Adapted from “Relative Clauses in

Dothraki,”Peterson 2011.)

‘The warrior that I saw’

(a)

(b)

What happens within these Dothraki object relativizations also happens with genitive, allative, and ablative

structures (18).

(18) Genitive, allative, and ablative relative clauses in Dothraki. (Adapted from “Relative Clauses in Dothraki,”

Melton 9

Peterson 2011.)

a. Mahrazh

fini

that[SG.GEN.ANI]

warrior[ANI]

‘The warrior whose arakh I saw’

anha

tih

see[PST] 1[SG.NOM] arakh[ACC.INA]

arakh4

b. Mahrazh

warrior[ANI]

‘The warrior who I gave an arakh to’

finnaan

that[SG.ALL.ANI]

anha

azh

give[PST] 1[SG.NOM] arakh[ACC.INA]

arakh

c. Mahrazh

warrior[ANI]

‘The warrior who I am stronger than’

finnoon

that[SG.ABL.ANI]

ahajanak

strong[COMP]

anha

1[SG.NOM]

Conclusion

The gender, number, and case systems of Dothraki have some analogs in natural language, but also break some

universal rules as stated by Greenberg (1963) and others. Dothraki relative clause structures break universals that

minimalist syntax cannot represent. While Peterson explains these violations within the fictional history of the

language, they have no correspondence in natural language and lead me to conclude that Dothraki is, at least in

someways, unnaturalistic. While no one should fault Peterson for taking artistic license in creating a language

which will really only have life in a fictional universe, I maintain that calling it a naturalistic conlang is a valid

statement.

4 An arakh is a curved sword which has no English name.

Melton 10

References

Blake, Barry J. “Case.” Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1994.

“David Peterson on developing Dothraki” www.ed.ted.com. Web. 8 May 2014.

Greenberg, Joseph. “Some Universals of Grammar with Particular Reference to the Order of Meaningful

Elements.” Universals of Language (1963): 110-13.

Peterson, David. “About David J. Peterson.” Dothraki: A Language of Fire and Blood. 28 March 2013.

Dothraki.com. Web. 8 May 2014.

Peterson, David. “Athchomar Chomakea!” Dothraki: A Language of Fire and Blood. Dothraki.com. 14 September

2012. Web. 17 May 2014.

Peterson, David. “Dothraki 101.” Dothraki: A Language of Fire and Blood. Dothraki.com. Web. 17 May 2014.

Peterson, David. “Relative Clauses in Dothraki.” Dothraki: A Language of Fire and Blood. Dothraki.com. 13 October

2011. Web. 8 May 2014.