A Grammar of Eastern Classical Dryadic

Author: Jesse D. Holmes

MS Date: 06-06-2017

FL Date: 07-01-2018

FL Number: FL-000052-00

Citation: Holmes, Jesse D. 2017. “A Grammar of Eastern

Classical Dryadic.” FL-000052-00, Fiat

Lingua,

2018.

Copyright: © 2017 Jesse D. Holmes. This work is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

Fiat Lingua is produced and maintained by the Language Creation Society (LCS). For more information

about the LCS, visit http://www.conlang.org/

UNIWERSYTET WROCŁAWSKI

WYDZIAŁ NAUK HISTORYCZNYCH I PEDAGOGICZNYCH INSTYTUT

EUROPEAN CULTURES

JESSE D. HOLMES

A GRAMMAR OF EASTERN CLASSICAL DRYADIC

Praca lincencjacka napisana pod kierunkiem:

Prof. dr. hab. Mirosław Kocur

WROCŁAW 2017

1 Introduction

1.1 Extent of the Classical Dryadic Language

Contents

1.2 Typology

2 Phonology and Phonetics

2.1 Dryadic Physiology and Speech

2.2 Phonemes

2.2.1 Consonants

2.2.2 Vowels

2.3 Stress

2.4 Phonotactics

3 Writing System and Romanization

3.1 Classical Dryadic Alphabet

3.2 Romanization

4 Nouns and Pronouns

4.1 Plural Prefixes

4.2 Noun Cases

4.2.1 Relational and Essive Suffixes

4.2.2 Locative and Lative Suffixes

4.2.3 Vocative Suffixes

4.2.4 Genitive Suffixes

4.2.5 Other Suffixes and Adpositions

5 Adjectives and Adverbs

5.1 Adjectival Agreement

5.2 Forming Superlatives and Comparatives

5.3 Adverbs and Adverbial Suffixes

6 Verbs and TAM

6.1 Transitive Verbs and Nominal Tense

6.2 Intransitive Verbs, Participles, Negation, and Interrogatives

6.3 Irregularities and Dual-Transitive Verbs

6.4 Speech Levels and Honorifics

6.5 Aspectual and Modal Affixes and Verbal Prefixes

6.6 Emphatic Suffixes, Imperative Mood, Evidentiality, and Noun Clauses

7 Relative Clauses and Complex Sentences

7.1 Relative Clauses

7.2 Conjuction Words and Constructions

8 Vocabulary and Phrases

8.1 Differences of the Sacred Register

8.1.1 Pronouns, Nouns, and Adjectives

8.1.2 Verbs and TAM

8.1.3 Lexical Differences

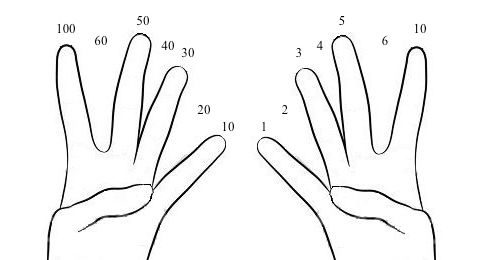

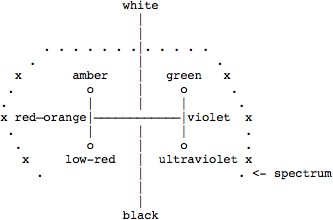

8.2 Numbers and Religion

8.3 Mimetic Words

8.4 Flowers, Plants, and Fungi

8.5 Animaplants

8.6 Family and Relations

8.7 Houses, Buildings, and Decor

8.8 Clothing and Ornaments

8.9 Body Parts

8.10 Speaking, Eating, and Gardening

8.11 Time, Seasons, Flavors, and Direction

8.12 Natural Bodies

8.13 Emotion and Moral

8.14 War, Government, and Clans

8.15 Entertainment, Music, and Art

8.16 Miscellaneous

9 Literature and Excerpts

9.1 Dryadic Myth: Song of the Universe

9.2 Dryadic Legend: Princess of Camellias

9.3 Short Story: The Flower King

9.4 Classical Dryadic Poetry

9.4.1 Song of the Dryads

9.4.2 Tree Never Grown

9.4.3 My Blossom in the Wind

9.4.4 A Future Together

1. Introduction

1.1. Extent of the Classical Dryadic Language

The Classical Dryadic language was a language spoken by the native,

humanoid inhabitants of Planet Eunomia approximately between the years 1000 BFC

(≈1400 CE)1 and 200 BFC (≈1950 CE), before eventually developing into the early

modern language variants, such as Middle Meliadic Dryadic, by the second century

BFC. The extent of the language encompassed much of the dryads’ domain2,

becoming the central language in the Golden Age of the dryads and the dominate

uniting force of the Meliadic Clan, subjugating most of the other more diverse dryadic

languages spoken in the area. A clear divide, however, existed between speakers west

of the Sphurathic Mountains and speakers to the east. The east, centered around the

forest of Asympusht and home to the Meliat Clan, formed the basis for standardized

writing and maintained itself as the primary written language of the dryads up until

the modern spelling reformations of 96 AFC (2182 CE). It is still used in religious

texts and literature from the classical period. The western variants, however, varied

greatly as they had taken in great influences from the previous languages spoken by

the dryadic tribes in that area. Very few texts survive that portray the spoken western

variants of Classical Dryadic using the standardized eastern orthography to convey its

sounds, usually in informal contexts such as personal letters or drawings of short

messages in the dirt.

Much of what we know about Classical Dryadic comes from analyzing

documents left over from the classical period and comparative methods using the

modern Dryadic languages and the languages spoken around the beginning of the first

century AFC. The written form of the language can still be seen in religious texts

decorating the walls and ceilings of Dryadic temples, and it is still studied in Eunomic

schools by both dryads and humans. Classical Dryadic is often compared to the use of

Latin and Greek in Europe prior to antiquity and well into modern years.

1 BFC (meaning “Before First Contact”) is a calendar era using Eunomic years to record the date based

on the arrival of humans to the planet Eunomia, its adverse being AFC (or “After First Contact”). In

parenthesis is the approximate equivalent in accordance with Earth years and the Earth calendar.

2 The biology of dryads, unlike humans, prevent them from living outside of specific environments,

and, prior to first contact, there was never incentive for them to populate their entire planet and

migrate; thus, the dryadic domain and the diversity among dryads are not as grand as they are for

humans on Earth.

1.2. Typology

Classical Dryadic is often typologically categorized as an agglutinative

language. It can also be classified as slightly fusional. Its morphosyntactic alignment

is ergative-absolutive; however, unlike most other known ergative-absolutive

languages where the absolutive case remains unmarked, in Classical Dryadic the

absolutive case is marked. Its primary writing system is a featural alphabet consisting

of 14 basic symbols that form the basis of a total of 29-31 letters3. It has no distinction

of gender or noun classification, it has no articles, and there are only two noun

numbers: singular and plural. It modifies and inflects nouns, adjectives, pronouns,

numerals, and verbs depending on their role in the sentence. Its many noun cases are

divided into 5 groups: morphosyntactic alignment/relation, location, motion to,

motion from, and TAM (tense-aspect-mood). There is also a clear distinction between

transitive and intransitive verbs, which affects the basic word order of a sentence.

The basic word order of Classical Dryadic is OVS when the verb is transitive,

and SV when the verb is intransitive. Adjectives can go before or after the noun they

modify; however, the former is most common. Possessive nouns follow the noun they

possess, and numerals always precede the noun. It is primarily a head-final language.

3 The exact amount of letters depends on what one considers a letter in the Dryadic alphabet; this will

be further looked at in section 3.1.

2. Phonology and Phonetics

2.1. Dryadic Physiology and Speech

The organs and structures used in the articulation of dryadic speech are very

similar to that of humans. The dryadic mouth, throat, and nasal cavity bear surprising

similarities with human anatomy and allow for the production of many similar

phonemes. These phonemes are not exact. Dryads lack a bridged nose and have a

much smaller nasal cavity, which changes the resonance of nasal consonants and

nasalized vowels. Their teeth-like structures are also made of a woody lignin

substance slightly affecting the quality of frication with dental fricatives. The most

striking difference is in the lungs. Unlike humans, who have full control over the

inflow and outflow of air in their lungs, dryads’ lungs act as independent structures.

Their breathing is entirely involuntary, bringing in and expelling air in periods of

equal length. This causes all dryadic languages to be spoken in a manor of alternating

pulmonic egression and ingression.

2.2. Phonemes

There are 6 vowels, 1 diphthong, and 25 consonant phonemes in Classical Eastern

Dryadic.

2.2.1. Consonants

Labial Dental Alveolar Palatal Velar Glottal

m

p b

f v

Nasal

Stop

Fricative

Approximate

Tap

Lateral

n

t d

θ ð

(l̪ )

(n)

ɲ

ʃ ʒ

j

(t) (d)

s z

ɾ

l

ŋ

k g

x ɣ

w

(h)

The dental /n̪ /, /t̪ /, and /d̪ / are retracted to the alveolar /n/, /t/, and /d/ in certain

consonant clusters, such as /st/, /zd/, /ʃt/, /ʒd/, /ɾt/, and /ɾd/.

stoñ [stõŋ] ‘to plant’, ‘to speak’

twel [t̪ ʷɛːl̪ ] ‘many’

In the some dialects of Eastern Classical Dryadic, speakers may pronounce the

/ɾ/ as /ʐ/ or /ʂ/ when preceded by a non-nasal bilabial consonant, or followed by /t̪ / or

/d̪ /, which in this case, would become /t/ and /d/.

bruñ [bɾũŋ] ~ [bʐũm] ‘to give’

artym [ˈhaɾt!̃m] ~ [ˈhaɾtʃʲə̃m] ~ [ˈhaʂtʃʲə̃m] ‘full-moon’, ‘one’

In these same dialects, when /ɾ/ is preceded by a nasal, the nasal becomes a

stop.

nruth [nɾuːθ] ~ [dɾuːθ] ‘beautiful’

In some dialects, and later on towards Middle Meliadic Dryadic, /t̪ i/ and /d̪ i/

are retracted to /ti/ and /di/, and in some cases even palatalized to become /tʃi/ and

/dʒi/. The same is true with /t̪ ʲ/ and /d̪ ʲ/ becoming /tʃ/ and /dʒ/.

andin [ˈhandĩn] ~ [ˈhandʒĩn] ‘peach-like fruit’

tiaroñ [ˈt̪ ʲaɾɔ̃ŋ] ~ [ˈtʃaɾɔ̃ŋ] ‘to rip’, ‘to pull apart’

The same phenomenon can also result in the palatalization of /si/ and /zi/ to

/ʃi/ and /ʒi/.

sichros [ˈsixɾɔs] ~ [ˈʃixɾɔs] ‘now’, ‘at this time’

The phoneme /l/ becomes fronted to a dental /l̪ / at the end of a word. This also

happens when /l/ proceeds a dental consonant and when /l/ proceeds a labial or velar

consonant while following an open or mid vowel such as /ɛ/, /ɔ/, or /a/.

ñwel [ŋʷɛl̪ ] ‘yes’, ‘such’, ‘true’

mil’dherys [mil̪ ˈðɛɾɨs] ‘sea creature’, ‘aquatic animaplant’

palgise [pal̪ ˈgisɛ] ‘quickly’

Vowels never begin a word; instead, all words that seem to begin with a vowel,

actually begin with the phoneme /h/.

2.2.2. Vowels

aeryth [ˈhaɪɾɨθ] ‘earth’, ‘soil’, ‘food’

elath [ˈhɛlaθ] ‘elath flower’, ‘eunomic lilac’

uthyr [ˈhuθɨɾ] ‘random’, ‘unpredictable’

Front Central Back

Close

Mid

Open

i

ɛ

u

ɔ

ɨ

(jə)

a

Diphthong

aɪː

The vowel /jə/ is a variation of /ɨ/ and can be found in certain dialects

palatalizing the consonant that precedes it.

izyn [ˈhiz!̃n] ~ [ˈhiʒʲə̃n] ‘strange’, ‘abnormal’

chwyn [xʷ!̃n] ~ [xɥə̃n] ‘sprout’, ‘child’

In one of its evolutionary branches containing Middle Meliadic Dryadic, /jə/

came to replace /ɨ/, palatalizing the consonants that come before it. Every vowel is

also nasalized when it precedes a nasal consonant.

chronzeñ [ˈxɾɔ̃nzɛ̃ŋ] ‘to love’

zuluñ [ˈzulũŋ] ~ [ˈzulũm] ‘perhaps’, ‘maybe’

2.3. Stress

The main stress of a root word in its null form is always on the penultimate

syllable. All root words in their null form can have no more than three syllables.

drís [ˈd̪ ɾis] ‘tree’, ‘word’

élos [ˈhɛ.lɔs] ‘nostril(s)’

sorélyñ [sɔ.ˈɾɛ.l!̃ŋ] ‘to comfort’, ‘to embrace’

When a root word is inflected with a case or TAM ending, the stress remains

on the penultimate syllable of the entire word.

dríse [ˈd̪ ɾi.sɛ] ‘to the tree/word’

drisíse [d̪ ɾi.ˈsi.sɛ] ‘from the tree/word’

elóse [hɛ.ˈlɔ.sɛ] ‘to the nostril(s)’

elosíse [hɛ.lɔ.ˈsi.sɛ] ‘from the nostril(s)’

crélen [ˈkɾɛ.lɛ̃n] ‘(it) doesn’t come/go’

creléno [kɾɛ.ˈlɛ̃.nɔ] ‘doesn’t (it) come/go?’

If a lexical suffix is attached to a root word, then the stress remains on the

penultimate syllable in both the null and inflected forms.

drísyph (dris + -yph)4 [ˈd̪ ɾi.sɨf] ‘young tree’, ‘sappling’

drísphe [ˈd̪ ɾis.fɛ] ‘to the young tree’

drisphíse [d̪ ɾis.ˈfi.sɛ] ‘from the young tree’

drísel (dris + -el)5 [ˈd̪ ɾi.sɛl̪ ] ‘dryad’, ‘sentient individual’

4 The suffix -yf indicates something young or juvenile.

5 The suffix -el indicates a sentient or conscious, usually humanoid, being. It can also be used to

indicated a ‘doer’ of something, similarly to the English suffix -er.

driséle [d̪ ɾi.ˈsɛ.lɛ] ‘to the dryad’

driselíse [d̪ ɾi.sɛ.ˈli.sɛ] ‘from the dryad’

When a lexical prefix is attached to a root word, then, if the root has one

syllable, the stress is on the last syllable. In all other cases, the stress remains on the

penultimate syllable.

zedrís (ze- + dris) [zɛ.ˈd̪ ɾis] ‘trees’, ‘words’, ‘language’

zedrísel (ze- + drisel) [zɛ.ˈd̪ ɾi.sɛl̪ ] ‘dryads’, ‘people’

shecréñ (she- + creñ) [ʃɛ.ˈxɾɛ̃ŋ] ‘to leave’

shethmiéryc (sheth- + mieryc) [ʃɛθ.ˈmʲɛ.ɾɨk̚ ] ‘yesterday night’

chrezhýl (chreth- + zhyl) [xɾɛ.ˈʒɨl̪ ] ‘tomorrow’

When a root word with a lexical prefix is inflected, the stress is on the

penultimate syllable unless the inflected word has two syllables, in which case the

stress would be on the last syllable.

zedríse [zɛ.ˈd̪ ɾi.sɛ] ‘to the tree’

zedriséle [zɛ. d̪ ɾi.ˈsɛ.l̪ ɛ]] ‘to the dryad’

shecrélen [ʃɛ.ˈxɾɛ.lɛ̃n] ‘(it) doesn’t leave’

shecreléno [ʃɛ. xɾɛ.ˈlɛ̃.nɔ] ‘doesn’t (it) leave?’

shethmiergíse [ˌʃɛθ.mʲɛɾ.ˈgi.sɛ] ‘since yesterday night’

chrezhlé [xɾɛ.ˈʒlɛ] ‘until tomorrow’

In the case of compound words, if the word has a total of two syllables then

the stress is on the penultimate syllable. The stress remains on the penultimate

syllable in its inflected forms as well.

mílaer (mil + aer) [ˈmi.laɪɾ] ‘water’

miláere [mi.ˈlaɪ.ɾɛ] ‘to the water’

milaeríse [mi.laɪ.ˈɾi.sɛ] ‘from the water’

If the compound word has three syllables – the first root in the compound

containing two syllables and the second root containing one syllable – then the

primary stress is on the first syllable and the secondary stress is on the third syllable.

When such a word is inflected, the stress moves to the penultimate syllable.

árzhy’drìs [ˈhaɾ.ʒɨ.ˌd̪ ɾis] ‘father’

arzhy’dríse [haɾ.ʒɨ.ˈd̪ ɾi.sɛ] ‘to the father’

arzhy’drisíse [haɾ.ʒɨ. d̪ ɾi.ˈsi.sɛ] ‘from the father’

If the compound words have three syllables, but the first root has one syllable

and the second root has two syllables, then the stress is on the penultimate syllable in

both in the null form and inflected forms.

bhzul’áryzh [vzu.ˈla.ɾɨʒ] ‘stupidity’

bhzul’árzhe [vzu.ˈlaɾ.ʒɛ] ‘to the stupidity’

bhzul’arzhíse [vzu.laɾ.ˈʒi.sɛ] ‘from the stupidity’

2.4. Phonotactics

A syllable in Classical Dryadic is structured as the following:

C(C)(C)V(C)

The following are all the viable onset consonants and consonant clusters in

Classical Eastern Dryadic. All words in Classical Dryadic must begin with a

consonant sound, specifically one of the primary consonants found to the left of the

chart below. The chart also lists every viable consonant cluster that can begin a

syllable or word in Classical Dryadic.

Secondary Consonants

/m/

/p~b/

/f~v/

/n/

/t~d/

/θ~ð/

/s~z/

/ʃ~ʒ/

/ɾ/

/l/

/j/

/k~g/

/x~ɣ/

/w/

/m/

/p/

/b/

/f/

/v/

/n/

/t/

/d/

/θ/

/ð/

/s/

/z/

/ʃ/

/ʒ/

/ɾ/

/l/

/j/

/ŋ/

/k/

/g/

/x/

/ɣ/

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

/θf/

/ðv/

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

/sm/

/sp/

/sf/

/sn/

/st/

/zm/

/zb/

/zv/

/zn/

/zd/

/ʃm/

/ʃp/

/ʒm/

/ʒb/

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

/ʃn/

/ʃt/

/ʒn/

/ʒd/

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

/mɾ/

/ml/

/mj/

/pθ/

/ps/

/pʃ/

/pɾ/

/pl/

/pj/

/bð/

/bz/

/bʒ/

/bɾ/

/bl/

/bj/

/fθ/

/fs/

/fʃ/

/fɾ/

/fl/

/fj/

/vð/

/vz/

/vʒ/

/vɾ/

/vl/

/vj/

–

–

–

–

–

/sθ/

/zð/

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

/nɾ/

/tɾ/

/dɾ/

–

–

–

/nj/

/tj/

/dj/

/θɾ/

/θl/

/θj/

/ðɾ/

/ðl/

/ðj/

–

–

–

–

–

/ŋɾ/

–

–

–

–

–

–

/ʃj/

/ʒj/

/ɾj/

/lj/

–

/ŋj/

/ks/

/kʃ/

/kɾ/

/kl/

/kj/

/gz/

/gʒ/

/gɾ/

/gl/

/gj/

–

–

–

–

/xɾ/

/xl/

/xj/

/ɣɾ/

/ɣl/

/ɣj/

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

/mw/

/pw/

/bw/

/fw/

/vw/

/nw/

/tw/

/dw/

/θx/

/θw/

/ðɣ/

/ðw/

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

/ʃw/

/ʒw/

/ɾw/

/lw/

–

/ŋw/

/kw/

/gw/

/xw/

/ɣw/

–

–

/sj/

/sk/

/sx/

/sw/

/zɾ/

/zl/

/zj/

/zg/

/zɣ/

/zw/

/w/

/h/

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

The /s/ and /z/ consonant clusters featuring a secondary nasal, stop, or fricative

can also take on a trinary (semi-)consonant of either /j/ or /w/.

snwor [snʷɔɾ] ‘song’

zdwesh [zdʷɛʃ] ‘tendrils’

The nucleus of a Classical Dryadic syllable is fairly straightforward as it

simply one of the 6 vowels or the one diphthong found in the language: /a/, /ɛ/, /i/, /ɨ/,

/ɔ/, /u/, or /aɪ/.

The following consonants can act as a coda in Classical Dryadic, but only

when the syllable is at the end of the word: /p/, /f/, /t/, /θ/, /s/, /z/, /ʃ/, /ʒ/, /ɾ̥ /, /l̥ /, /k/,

and /x/. If the syllable is in the middle of a word and the subsequent syllable begins

with a voiced consonant (i.e. when forming a compound word), then the consonants

become voiced: /b/, /v/, /d/, /ð/, /z/, /z/, /ʒ/, /ʒ/, /ɾ/, /l/, /g/, and /ɣ/.

pwezbhel (pwes + bhel) [ˈpʷɛzvɛl̪ ] ‘deciduous leaf’

phiadh’zeñ (phiath + zeñ) [ˈfʲaðzɛ̃ŋ] ‘to love, befriend’

If the subsequent syllable begins with an unvoiced consonant, then the

consonants remain unvoiced, except in the cases of /z/ and /ʒ/, which become /s/ and

/ʃ/.

shic’stoñ (shic + stoñ) [ˈʃikstɔ̃ŋ] ‘to yell’

myth’sieruñ (myth + sier + -uñ) [mɨθˈsʲɛɾũŋ] ‘sympathetic’

If a syllable beginning with a vowel (technically /h/) is morphologically

placed or ‘glued’ after a syllable ending in a coda consonent (either through inflection

or word compounding), then the /h/ is dropped and the coda becomes voiced except in

the case of fricatives, which remain unvoiced.

phiet [fʲɛt̪

̚ ] ‘floor’

phiedol (phiet + -ol) [ˈfʲɛd̪ ɔl̪ ] ‘on/above the floor’

mieryc [ˈmʲɛɾɨk̚ ] ‘night’

mierguñ (mieryc + -uñ) [ˈmʲɛɾgũŋ] ‘at night’, ‘during the night’

The nasal consonants /m/, /n/, and /ŋ/ can also end a syllable at the end of a

word. When a syllable follows a nasal consonant, and it begins with a single unvoiced

consonant, then the nasal consonant nasalizes to the same articulation as the

consonant, and that consonant becomes voiced (with the exception of /s/ and /ʃ/).

chiambesh (chiam + pesh) [ˈxʲãmbɛʃ] ‘perfume’

creñgrim (crem + crim) [ˈkɾɛ̃ŋgɾĩm] ‘memory’

This voicing also happens when the single unvoiced consonant is a stop and is

preceded by a vowel.

dhebaeros (dhewa + paeros) [ðɛˈbaɪɾɔs] ‘circle’

sidoche (si- + toch + -e) [siˈd̪ ɔxɛ] ‘precisely, exactly’

There are no geminate consonants in Classical Dryadic, so when two of the

same consonant end up next to each other, one of them is dropped.

chel’snwor (chelys + snwor) [ˈxɛlsnʷɔɾ] ‘thunder’

nusho’mil (nushom + mil) [ˈn̪ uʃɔˌmil̪ ] ‘doubt’, ‘mistrust’

3. Writing System and Romanization

3.1. Classical Dryadic Alphabet

Classical Eastern Dryadic is written using a featural alphabet, originating from

a part-logographic part-abjad script that was used to write Ancient Dryadic. The

alphabet is written away from the writer, from bottom to top in lines going left to right,

mimicking the growth of plants6. The Ancient Dryadic script was originally written

on the ground, in dirt, sand, or mud, using a stick or one’s finger7; however, by the

time of the Classical Dryadic languages, the written language had transferred to

colorful paints on walls and stone (using a brush or using a finger), and eventually to

ink on parchment (usually with a brush).

Phonetically speaking, the Classical Dryadic alphabet can be broken into 14

separate components that comprise the written language. The components come

together to form 29 phonetic letters, 21 consonants, 2 semi-consonants, and 6 vowels,

which are displayed in the chart below.

Letters

Full Name

Short Name IPA Romanization

p

b

f

v

t

pesh ‘pollen’

pesh

/p/

leph pesh ‘deep pollen’

besh

/b/

p

b

thruch pesh ‘thin pollen’

phesh

/f/

ph

lephthruch pesh ‘deep-thin pollen’

bhesh

/v/

bh

tos ‘spore’

tos

/t/

t

6 For rendering and utility purposes, any written Dryadic in this grammar will be displayed left to right

like English using a modern Dryadic computer font except in the charts displaying individual letters.

7 Many of the remaining samples of Ancient Dryadic writting are preserved in hardened mud and clay.

d

T

D

k

g

h

G

S

Z

F

V

N

leph tos ‘deep spore’

dos

/d/

d

thruch tos ‘thin spore’

thos

/θ/

th

lephthruch tos ‘deep-thin spore’

dhos

/ð/

dh

cesta ‘pod’

cesta

/k/

leph cesta ‘deep pod’

gesta

/g/

c

g

thruch cesta ‘thin pod’

chesta

/x/

ch

lephthruch cesta ‘deep-thin pod’

ghesta

/ɣ/

gh

sun ‘leaf bud’

sun

/s/

leph sun ‘deep leaf bud’

zun

/z/

s

z

thruch sun ‘thin leaf bud’

shun

/ʃ/

sh

lephthruch sun ‘deep-thin leaf bud’

zhun

/ʒ/

zh

ñeltosyc ‘left sporangium’

ñel

/ŋ/

ñ

r

n

M

L

w

j

a

e

y

i

o

u

rintosyc ‘right sporangium’

rin

/ɾ/

nilbhel ‘unfurling leaf’

nilbhel

/n/

r

n

nizbhel ‘unfurled leaf’

nizbhel

/m/

m

lot ‘flower bud’

lot

/l/

l

wethych ‘sepal’

wethych

/w/

w

dwesh toscy ‘tendril of sporangium’

yot

/j/

y/i

dwesh a ‘tendril a’

a

/a/

dwesh e ‘tendril e’

dwesh y ‘tendril y’

dwesh i ‘tendril i’

dwesh o ‘tendril o’

dwesh u ‘tendril u’

e

y

i

o

u

/ɛ/

/ɨ/

/i/

/ɔ/

/u/

a

e

y

i

o

u

As seen above, the letters pesh, tos, cesta, and sun all act as bases for their

‘deep’, ‘thin’, and ‘deep-thin’ counterparts. By adding an extra node below the base to

the left side of the stem, the node acts as the lebhem or a ‘deepener’ or even a ‘voicer’,

which voices the consonant. Another diacritic, a sort of squiggly line called the

thrughem, ‘thinner’ or ‘fricator’, can be placed to the left of the letter to make it

fricative. The vowels are simply made up of 3 distinct letters, and the side of the stem

it rests on determines its pronunciation.

The lebhem, however, does not only determine the voicing of one consonant,

but also the voicing of an entire string of consonants. For instance, the previously

mentioned example in 2.4 with pwezbhel, the lebhem with the leph pesh in bhel would

be moved behind the sun in pwes.

cpweS + cveL

pwes (‘fallen’) + bhel (‘leaf’)

cpwezfeL

pwezbhel (‘deciduous leaf’)

Additionally, the example using the word zdwesh would be spelled as follows:

cztweF

zdwesh (‘tendrils’)

The letters are all placed on a poviath or ‘stem’ connecting all the letters of one

word or root word. All words begin with a shtol’poviath or ‘beginning stem’, and

words that end in vowels must end with an erys or ‘blossom’.

Letter/Character

Name

c

x

shtol’poviath

erys

It is often debated whether these two characters should be treated as letters

themselves or as punctuation, resulting in confusion as to whether there are 29 letters

or 31 letters in the Classical Dryadic alphabet. A break in the stem is used to indicate

most compound words or contractions:

carJy ‘driS

arzhy’dris (‘father’)

cers ‘seN

ers’señ (‘to blossom’, ‘to like’)

There are three primary symbols used for punctuation in Classical Dryadic.

The following chart displays the punctuation, its Dryadic name, and the English

equivalent:

Punctuation

Name

English Equivalent

,

.

:

dharomyph ‘small pause’

comma, semicolon

dharomyc ‘full pause’

period, exclamation or

question mark

chomyc ‘something that explains,

tells, or shares’

colon, quotation marks

The dharomyph is used to separate clauses or when separating individual

objects in a list, much like the English use of the comma. The dharomyc indicates a

full stop, usually the end of a complete sentence. The chomyc, however, can serve the

functions of both a colon and of quotation marks. It can be used to indicate a list of

objects, or to show that the following line of text is spoken aloud. The following

example sentence demonstrates the use of the three different kinds of punctuation:

cbex czedrisax cton cdaS , cNjer cdex

csjex czedrisax cstoM cbaS : cdux

cGrisex cg ‘arDelaex .

Be zedrisa ston das, ñier de sia zedrisa stom bas: du ghrise g’ardhelae.

I talked to her, but she told me that she really dislikes me.

(Lit. I talked to her, but she said to me this: I really dislike you!)

The dharomyc itself does not actually determine whether a sentence is

interrogative or exclamatory; that is done through suffixes and other cues in the

language itself. The dharomyc simply indicates the end of a complete sentence.

3.2. Romanization

The most popular and widely used romanization system of Classical Dryadic

is the Willis romanization, which was devised in 32 AFC by the human xenolinguist,

Enid J. Willis. Other systems of romanization were proposed by other linguists;

however, the Willis romanization proved the most effective at conveying both the

spoken and written language and eventually became the official romanization of the

Classical Dryadic language in scholarly work. The Willis romanization also proved

popular with native dryads as a method to write their own language using Latin

characters.

The Willis romanization uses 21 individual Latin characters: a, b, c, d, e, g, h,

i, l, m, n, o, p, r, s, t, u, w, y, and z. The letter h, however, is used with base

consonants to represent the thrughem or the ‘fricator’. This creates 8 diglyphs

representing a single sound: bh, ch, dh, gh, ph, sh, th, and zh. When two voiced

consonants are in a consonant cluster, they are both written as voiced using the Willis

romanization. Another less popular romanization, the Branson romanization or

Branson transcription, assigns each sound its own letter and gets rid of the diglyphs

used in Willis romanization. Willis also devised a transliteration system, called Willis

transliteration, which marks voiced consonants with a dot above the voiceless

consonant mimicking the use of the lebhem in Dryadic orthography and includes

other features that mimic the language’s orthography. The following chart shows the

letters of the Classical Dryadic alphabet and their respective transcriptions and

transliterations in the three systems previously mentioned:

Letters IPA Willis Rom. Branson Rom. Willis Trans.

p

b

f

v

/p/

/b/

p

b

/f/

ph

/v/

bh

p

b

f

v

p

ṗ

p

ṗh

t

d

T

D

k

g

h

G

/t/

/d/

t

d

/θ/

th

/ð/

dh

/k/

/g/

c

g

/x/

ch

/ɣ/

gh

S

/s/

Z

/z/

s

z

F

V

/ʃ/

sh

/ʒ/

zh

t

d

ç

c

k

g

h

ğ

s

z

š

ž

t

ṫ

th

ṫh

c

ċ

ch

ċh

s

ṡ

sh

ṡh

/ŋ/

/ɾ/

/n/

ñ

r

n

/m/

m

/l/

l

/w/

w

/j/

/a/

/ɛ/

/ɨ/

/i/

/ɔ/

y/i

a

e

y

i

o

N

r

n

M

L

w

j

a

e

y

i

o

ŋ

r

n

m

l

w

j

a

e

y

i

o

ŋ

r

n

m

l

w

y

a

ä

i

ï

o

/u/

u

u

/aɪ/

ae

ai/aj

ö

aä

u

e

a

The following example sentences show the three systems in use:

cpwezfelax cTela ‘Telax cnuCoN

caryM cnweTaL .

Spwezbhela thela’thela nushoñ arym nwethal.

Spwezvela çela’çela nušoŋ arym nweçal.

Spwäṡphela thäla’thäla nöshoŋ arim nwäthal.

(The autumn breeze softly tosses the deciduous leaves.)

cTaelax cpewaDax csmirinex carDesaf

chrosaf , csfuroL cfjulgoL cstoS

cwiM cbaS .

Thaela Pewadha smirine ardhesaph chrosaph, sphurol phiulgol stos wim bas.

Çaila pewaca smirine arcesaf hrosaf, sfurol fjulgol stos wim bas.

Thaäla päwaṫha smïrïnä arṫhäsaph chrosaph, sphörol phyölċol stos wïm ṗas.

(When the Great Peony came into the world, he resided upon a lush hilltop.)

Punctuation remains the same in all three systems; however, when using the

Willis romanization, especially in an informal setting, it is not uncommon to see the

use of question marks and exclamation marks in the place of a dharomyc, usually for

emphasis. Generally, the dharomyc is represented by a period, the dharomyph is

represented by a comma, and the chomyc is represented by a colon.

4. Nouns and Pronouns

4.1. Plural Prefixes

Classical Dryadic distinguishes between singular and plural nouns. The plural

form of most nouns is formed by attached the plural prefix s/z(e)- to the front of a

noun. If the noun begins with a single, unvoiced consonant, excluding s or sh, then the

prefix s- is used.

thoñyl ‘cave’ > sthoñyl ‘caves’

carys ‘shore’ > scarys ‘shores’

If it begins with a voiced consonant or a sonorants, excluding z, zh, or ñ, then

the prefix z- is used.

bwor ‘wall’ > zbwor ‘walls’

nweth ‘wind’ > znweth ‘winds’

If the noun begins with a vowel, then the noun remains unchanged and takes

on no prefix.

erys ‘blossom’ > erys ‘blossoms’

aeth ‘floor, level > aeth ‘floors, levels’

The prefix ze- is used in all other cases; when the word starts with s, sh, z, zh,

or ñ, and when the word begins with a consonant cluster.

shil ‘bed’ > zeshil ‘beds’

dris ‘tree, word’ > zedris ‘trees, language’

Some nouns are irregular and have no plural form. These nouns are commonly

used with numbers or other quantitative adjectives and act as ‘counting nouns’.

zhyl ‘day, days’ > twel zhyl ‘many days’

zbhel ‘step, stairs’ > clivuñ zbhel ‘some steps’

Few nouns still show traces of an archaic dual number prefix; however, these

nouns are now treated as a single entity instead of an actual dual noun.

cozhyl ‘two-day period’ > chrowa cozhyl ‘three two-day periods’

colun ‘two moon period, Dryadic month’ > dhel colun ‘two Dryadic months’

This archaic dual prefix can also serve as the plural form of some nouns. Most

such nouns are found in pairs of two.

ghas ‘hand’ > coghas ‘hands’

nrel ‘eye’ > conrel ‘eyes’

The plural and dual prefix historically originated from Ancient Dryadic

numerals. The ancient number two, [qɑluːjaɾ] in Proto-Dryadic (coyar in Classical

Dryadic), shortened to [qɑlu-] and eventually co- and fused with nouns to represent

the dual form, which was commonly used in Ancient/Pre-Classical Dryadic. The

ancient number three, [sɛpʰuːɾat̪ ʰ] in Proto-Dryadic (sphurath in Classical Dryadic),

shortened to [sɛ-] or se- and eventually s/z(e)- and fused with nouns to represent the

plural form.

4.2. Noun Cases

The Classical Dryadic language has a rich case system, similar to that of

Caucasian languages on Earth. Many of these cases, however, are formed through the

combination of 20 basic case suffixes. These basic ‘building’ suffixes are divided into

three groups: relational/essive suffixes, locative suffixes, and lative suffixes. The final

group is the vocative group, which is independent of the other case endings. The

following chart displays all the basic suffixes and their use:

Case

Suffix

Use

Null

–

– The normal, unmarked form of a noun

Absolutive

-a

– The object of a transitive verb

– The subject of an intransitive verb

Genitive

-i/y

– The possessor of another noun

Instrumental

/Comitative

-u

– An instrument or means of doing something

– Being in company of someone/something

Carrative

-wen

– The lack of something

Comparative

-on

– A comparison with something

Essive-

modal

-uñ

Adessive

-aph

– A temporary state of being

– Concerning something/someone

– A general location, at something

– Around or near something

Abessive

Inessive

-is

-in

– The absence of something

– Located inside something

Extraessive

-och

– Located outside something

Superessive

-ol

– Located above something

Subessive

-oph

– Located under something

e

v

i

s

s

E

/

l

a

n

o

i

t

a

l

e

R

e

v

i

t

a

c

o

L

Antessive

-ath

– Located in front or before something

Postessive

-us

– Located behind or after something

Apudessive

-ech

– Located next to or beside something

Intrative

-uñ

– Located between two of something

Allative

-e

– Motion to something

e

v

i

t

a

L

e

v

i

t

a

c

o

V

Ablative

Perlative

Informal

-ise

-ith

-ae

Formal

-ayoñ

– Motion from something

– Motion through or along something

– Addressing someone familiar or younger

– Addressing someone unfamiliar

– Addressing someone of respect

Vulgar

-izhem

– Addressing someone/something of annoyance

4.2.1. Relational and Essive Suffixes

The first set of suffixes expresses morphosyntactic relation and states of the

noun or pronoun. The following charts display the three personal pronouns of

Classical Dryadic and their plural counterparts in each of the relational and essive

cases:

Null Abs Gen Inst/Com Car Comp Ess-M

1st S.

da

da

di

1st Pl.

zda

zda

zdi

2nd S.

ga

ga

gi

2nd Pl.

zga

zga

zgi

3rd S.

ba

ba

bi

3rd Pl.

zba

zba

zbi

du

zdu

gu

zgu

bu

zbu

dwen

don

duñ

zdwen

zdon

zduñ

gwen

gon

guñ

zgwen

zgon

zguñ

bwen

bon

buñ

zbwen

zbon

zbuñ

In the following example, the noun durym is used to demonstrate the suffixes

attached to a noun and their approximate translation to English.

Singular

Plural

durym

zdurym

durma

zdurma

English

house(s)

house(s)

durmy

zdurmy

of the house(s)

Null

Abs

Gen

Inst/Com

durmu

zdurmu

with the house(s)

Car

durmwen zdurmwen without the house(s), houseless

Comp

durmon

zdurmon

as/like the house(s)

Ess-M

durmuñ

zdurmuñ

as/concerning the house(s)

Notice that in this example, the y in the final syllable of the noun is dropped

when a suffix is added. This happens when the final syllable of a noun has the vowel

y surrounded on both sides by single consonants (not consonant clusters). This

‘disappearing y’ can reappear in other words, which have a second disappearing y,

usually from taking on a lexical suffix and then a case suffix.

durmyc (durym + -yc) > durimga ‘furniture’

ghorsyph (ghorys + -yph) > ghorispha ‘a type of instrument’

The penultimate syllable is stressed; however, the vowel y is fronted to i as

shown in the examples above.

4.2.2. Locative and Lative Suffixes

The locative and lative suffixes are used to the determine location, motion to,

motion from, and motion through something, and, thus, fill the role most adpositions

would in English. These suffixes can further combine to form even more suffixes,

specifying to where, from where, or through where the motion occurs.

Essive Lative Ablative Perlative

Ad-

Ab-

In-

-aph

-is

-in

-e

ise

-ise

–

-ith

–

-ine

-inise

-inith

Extra-

-och

-oche

-ochise

-ochith

Super-

-ol

-ole

-olise

-olith

Sub-

-oph

-ophe

-ophise

-ophith

Ant-

-ath

-athe

-athise

-athith

Post-

-us

-use

-usise

-usith

Apud-

-ech

-eche

-echise

-echith

Intra-

-uñ

-uñe

-uñise

-uñith

The locative suffixes can also combine with each other to form more specific

locations or postpositional suffixes.

In-

Extra- Super-

Sub- Ant- Post- Apud-

Ab-

-inis

In-

Extra-

-ochis

–

–

–

–

Super-

-olis

-olin

-oloch

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

-olech

Sub-

-ophis -ophin -ophoch

–

–

Ant-

-athis

-athin

-athoch

-athol

-athoph

Post-

-usis

-usin

-usoch

-usol

-usoph

Apud-

-echis

Intra-

-uñis

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

-ophech

-athech

-athoph

–

–

These compounded abessive suffixes are often used to clarify or reiterate

information on ‘when something is located away’ or ‘when it is not where it is

expected to be’, usually in agreement or disagreement with a question. For example:

Durmaph wiñ galno? “Are you at home?”

Dalen, durmis win dal. “No, I am away from home.”

Durmoch wiñ galno? “Are you outside the house (but still at home)?”

Dalen, durmochis win dal. “No, I am away from home (and thus not outside).”

The other compound suffixes are used to specify exactly where something is

located in relation to the object. Here are some examples:

Drisoph “under the tree (general)”

Drisophin “in the shade of the tree” or “the bottom of the tree (in its trunk)”

Drisophoch “underneath the tree (where its roots are)”

Durmath “at the front of the house (general)”

Durmathin “at the front (of the inside) of the house”

Durmathoch “in front of the house (outside)”

When the entire locative phrase fills a semantic or relational role in the

sentence or phrase, these locative suffixes can also be combined with the relational

and essive suffixes. For example:

Ibhinon eghros wim bal. “It is moist like the inside of (someone’s) mouth.”

Thoñlathocha gzan dal. “I see the way into the cave (the front from the outside).”

Thoñlathina gzan dal. “I see the way out of the cave (the front from the inside).”

The following is a chart showing the basic locative suffixes combined with the

relational and essive suffixes. The locative suffixes may also be compounded in

addition to taking on a relational/essive suffix as seen in the previous example.

Abs Gen

Inst/Com

Car

Comp Ess-M

In-

-ina

-iny

-inu

-inwen

-inon

-inuñ

Extra-

-ocha

-ochy

-ochu

-ochwen

-ochon

-ochuñ

Super-

-ola

-oly

-olu

-olwen

-olon

-oluñ

Sub-

-opha -ophy

-ophu

-ophwen -ophon -ophuñ

Ant-

-atha

-athy

-athu

-athwen

-athon

-athuñ

Post-

-usa

-usy

-usu

-uswen

-uson

-usuñ

Apud-

-echa

-echy

-echu

-echwen

-echon

-echuñ

Most of the time these compounded suffixes fill the role of noun phrases and

adpositional phrases that would consist of several words in English, thus condensing

them into a single word.

4.2.3. Vocative Suffixes

The vocative case in Classical Dryadic has three distinct registers: formal,

informal, and vulgar. The formal is primarily used when addressing someone of

higher social order (i.e. one’s Mother, the eldest sister, an unknown foreign sister, etc).

The informal, is used in all other occasions (i.e. a friend, a younger sister, a daughter,

etc). The vulgar register is used when one is angry or displeased with someone and

similar to the use of the English word ‘fuck(ing)’ with a noun as an interjection. The

following are examples of each registers with approximated English translations:

Csalayoñ! “Dear Mother!”

Sworelayoñ! “Dear Sister!” or “Princess!”

Chwynae! “My child!”

Ghuvelae! “My sister!”

Adhmelizhem! “Stupid pig!” or “Piece of shit!”

Gruzhbhizhem! “Damned fiend!” or “Son of a bitch!”

In some instances the vulgar register suffix can be replaced with the informal

suffix in order to lessen its intensity or to retain some respect, as the vulgar ending is

deemed as extremely taboo. Typical nouns and even nouns that are often used with

the formal register can also take on the vulgar suffix in rare instances.

Adhmelizhem! > Adhmelae! “Piece of crap!”

Gruzhbhizhem! > Gruzhbhae! “Son of a gun!”

Chwynae! > Chwynizhem! “Damned child!”

Csalayoñ! > Csalizhem! “Damned Mother!”

4.2.4. Genitive Suffixes

When a noun is in its genitive form and is possessing another noun, the

genitive noun takes on certain suffixes that agree with the case marking of the

primary noun. The genitive suffix, however, does not agree with every suffix in a

compound lative or locative suffix on the possessed noun; it only agrees with the final

suffix.

Case

Suffix

Example

Null

Abs

Gen

Ins/Com

Car

Comp

Ess-M

-i/y

-ia

-i(i)

-iu

-iu

-ion

-iuñ

erys drisely

ersa driselia

ersy driseli

ersu driseliu

erswen driseliu

erson driselion

ersuñ driseliuñ

Ad

Ab

In

-iaph ersaph driseliaph

-isy

-iin

ersis driselisy

ersin driseliin

Extra

-ioch

ersoch driselioch

Super

-iol

ersol driseliol

Sub

Ant

Post

-ioph ersoph driselioph

-iath

ersath driseliath

-ius

ersus driselius

Apud

-iech

ersech driseliech

Intra

-iuñ

ersuñ driseliuñ

All

Abl

Per

-ie

erse driselie

-(is)ie ersise drisel(is)ie

-iith

ersith driseliith

e

v

i

s

s

E

/

l

a

n

o

i

a

l

e

R

e

v

i

t

a

c

o

L

e

v

i

t

a

L

Inform

e

v

i

t

a

c

o

V

Form

Vulgar

-y

-y

-y

drisely ersae

drisely ersayoñ

drisely ersizhem

As seen in the chart above, the genitive form of a noun always follows the

noun that it possesses, except in the vocative cases. The reason the -is is optional in

the ablative form is because it is technically of a compound construction of the

abessive suffix combined with the allative suffix. In the null form, -i is used instead of

-y whenever the noun or pronoun has only one syllable in its genitive null form, most

likely through a disappearing y in the nucleus of its non-genitive null form.

4.2.5. Other Affixes and Adpositions

The infix -odh- is used to express ‘too’ or ‘also’, and is commonly infixed to

nouns and pronouns (before the case endings). The overall meaning of the sentence

and what is implied can change depending on which word it affixed to.

Dodhe win durmal. “I, too, have a house (you aren’t the only one).”

De win durmodhal. “I also a house (on top of the other thing I mentioned).”

Dodha mile crevial. “I, too, would like to go to the sea.”

Da milodhe crevial. “I would also like to go to the sea.”

Due to the extensive use of locative and lative suffixes in Classical Dryadic,

there are not many adpositions. The most common of these is the preposition, dho,

which combines with the genitive and absolutive forms of a noun to express either

causality or intent. When dho is used with a noun taking on the genitive suffix, then it

expresses causality or, more specifically, that the noun causes someone or something

else to do or be something non-volitionally. This is often translated as the phrase

‘because of’ in English.

Dho ñury aery, ers’señ zlotalen.

“The flowers do not blossom because of the winter weather.”

Dho gi, sichrosus de wiñ ghela shestol ebhalen.

“Because of you, I can no longer fall asleep.”

When dho is used with a noun taking on the absolutive suffix, then it

expresses intent and shows that the referent of the noun receives the benefit of the

situation expressed by the clause and, in most cases, is volitional or intended.

Dho ga, csale zedrisa ston das. “I spoke to Mother for you.”

Dho itra milaera, milbhishe crel win dal.

“I am going to the river for some fresh water.”

The use of dho will be discussed further in relation to dependent clauses in

Classical Dryadic and verbal phrases.

5. Adjectives and Adverbs

5.1. Adjectival Agreement

Adjectives take on agreement suffixes much like the genitive forms of nouns

take on extra endings in agreement with the noun they possess; however, unlike

genitive nouns, the adjective always precedes the noun it modifies. The following

chart displays all of the adjectival endings with each case and an example of an

adjective modifying a noun.

e

v

i

s

s

E

/

l

a

n

o

i

a

l

e

R

e

v

i

t

a

c

o

L

e

v

i

t

a

L

Case

Suffix

Example

Null

Abs

Gen

–

-a

bhzul dris

bhzula drisa

-i/y

bhzuly drisy

Ins/Com

Car

Comp

Ess-M

-u

-u

-on

-uñ

bhzulu drisu

bhzulu driswen

bhzulon drison

bhzuluñ drisuñ

Ad

Ab

In

-aph bhzulaph drisaph

-is

-in

bhzulis drisis

bhzulin drisin

Extra

-och

bhzuloch drisoch

Super

-ol

bhzulol drisol

Sub

Ant

Post

-oph bhzuloph drisoph

-ath

bhzulath drisath

-us

bhzulus drisus

Apud

-ech

bhzulech drisech

Intra

-uñ

bhzuluñ zedrisuñ

All

Abl

Per

Inform

e

v

i

t

a

c

o

V

Form

Vulgar

-e

-ise

-ith

–

–

–

bhzule drise

bhzulise drisise

bhzulith drisith

bhzul drisae

bhzul drisayoñ

bhzul drisizhem

When modifying a noun that takes on a compounded suffix, the adjective

agrees with only with the final suffix. If it modifies a noun with an agreeing genitive

suffix other than the genitive null form, then it takes on the same suffix as the noun.

Bhzulne durmine da cres. “I entered the large house.”

Spwezbhela ghria drisia nwethith zeral.

“The fallen leaves of the barren tree flutter through the wind.”

5.2. Forming Superlatives and Comparatives

To form the superlative and comparative forms of an adjective, suffixes

coming from certain locative suffixes are attached to the end. The superessive suffix

is used for the superlative, and a combination of the superessive and abessive suffixes

is used for comparatives. The reverse can be used as well with the subessive suffix,

taking on the meaning of “less” or “least”. The following chart displays the suffixes

and examples of their usage:

Suffix

Use

Example Translation

-ol

Superlative

swarol

sweetest

-olis

Comparative

swarolis

sweeter

-oph Anti-superlative

swaroph

least sweet

-ophis Anti-comparative swarophis

less sweet

These suffixes are not in agreement with a noun and are in the null form;

therefore, if they modify a noun they must take on an agreement suffix.

Sphurola drisa gzan das. “I saw the greenest tree.”

Chwerolisin aerthin wadha mreston das. “I replanted the seed in richer soil.”

When using an adjective to compare one noun to a second noun, the second

noun takes on the essive-modal suffix, and the adjective can take on either the

superlative or comparative form. The following example demonstrates this

construction:

Guñ dachol(is) win dal. “I am taller than you.”

Pustochuñ twelise ghwinol(is) wim pustinal.

“Inside the forest is much safer than outside the forest.”

Zbhaluñ nruthoph(is) wiñ zbhermal. “Leaves are less pretty than petals.”

In such a construction the superlative form of the adjective is used more often

since the comparativeness can be implied from context.

5.3. Adverbs and Adverbial Suffixes

In order to form an adverb in Classical Dryadic, the ablative suffix is added to

the end of an adjective.

palyc “quick” > palgise “quickly”

sphur “green, good” > sphurise “greenly, well”

That adjective is then most commonly placed in front of the primary verb of

the sentence; however, its placement is not entirely absolute, as it can also be placed

anywhere in the sentence as long as it comes before the verb.

Zedrisa sphurise stom bal. “He speaks well.”

Palgise ga crevae! “Go quickly!”

A second adverbial suffix exists, -eph; however, it is considered fairly archaic

and is rarely used. It is mainly used with higher registers or speech levels, which will

be further discussed in the next chapter.

Zedrisa sphureph stom baloñ. “He speaks well.”

Palgeph ga crevayoñ! “Go quickly!”

Other adverbs may be formed from nouns through certain affixes, the most

common of which being the instrumental, carative, essive-modal, and the comparative

suffixes.

Arzhu peghos win dal. “I am very tired.”

Psomwen pses win das. “I was helplessly lost.”

Chrethmierguñ ghela ston dalen. “I will not sleep tomorrow night.”

Zuluñ ge win du elvise crel eval. “Perhaps you can come with me.”

Aertha bia pethchon flon das. “I accidentally ate her food.”

The essive-modal suffix may also be used to form adjectives from nouns,

which then may take on an adverbial suffix such as the ablative suffix.

Gruthchuñise ñures win di ghuvelas. “My sister was dangerously injured.”

Milaerolin siera ñul’cholsuñise zlegzan das.

“I dispairingly stared at myself in (the reflection on) the water.”

6. Verbs and TAM (Tense-Aspect-Mood)

6.1. Transitive Verbs and Tense Endings

In Classical Dryadic, there is a clear syntactical distinction between transitive

verbs and intransitive verbs. When the main verb is intransitive, then the sentence is

verb final. When the verb is transitive, the sentence is subject final, the verb is placed

before the subject, and everything else precedes the verb. Every verb, both transitive

and intransitive, has the infinitive ending -ñ. This ending is also used as a linking

suffix for transitive verbs. This linking suffix nasalizes to -ñ, -n, or -m according to

the first phoneme of the subject noun phrase that follows it. The subject noun then

takes on a tense ending; -(a)l for non-past and -(a)s for past.

Infinitive

Linking

First Phoneme

Tense

Ending

Ending

of Subject

Ending

Example

Translation

c, g, ch, gh, ñ, s,

-ñ→

-ñ

z, sh, zh, w, l, r,

-(a)l/s

a, e, y, i, o, u

-ñ→

-n

t, d, th, dh, n

-(a)l/s

-ñ→

-m

p, b, ph, bh, m

-(a)l/s

bzhañ gal

you do (it)

bzhañ gas

you did (it)

bzhan dal

I do (it)

bzhan das

I did (it)

bzham bal

s/he does (it)

bzham bas

s/he did (it)

When a noun is the subject of a transitive verb and takes on a tense ending as

shown above, then any genitives or adjectives modifying the noun must come before

the noun. The linking ending of the verb than nasalizes to the beginning sound of

whichever word comes first in the subject noun phrase. Genitives and adjectives

modifying a transitive subject noun are in their null-forms, unless the subject noun

has a locative suffix (which comes before the tense suffix), in which case they would

take on the locative suffix.

Arzhy’snwora zem vzul chwynal. “The small child laughed.”

Aertha sphen drisy zbhermas. “The tree’s leaf touched the ground.”

Cra bin di ghasusas. “The back of my hand hit the rock.”

The copula and auxiliary verb, wiñ (‘to be’ or ‘to exist’), which is used to

connect the subject with a predicate adjective, null noun, or locative noun, is always

treated as a transitive verb.

Ghir win nrazal. “The sand is dry.”

Sworel pusty win di ghuvelal. “My sister is the princess of the forest.”

Rozhiscin win das. “I was in the garden.”

The auxiliary and semi-transitive verb, dhwoñ (‘to become’), which is used

solely with adjectives, is also treated as a transitive verb.

Swarise dhwoñ aeral. “Spring is come.” (“The air becomes sweet.”)

Chlebhise dhwom milaeras. “The water cooled down.” (“The water became cold.”)

A similar verb, ardheñ (‘to grow’, ‘to become’, ‘to like’), which can take on the

meaning ‘to become’ as used with nouns, is generally treated as an intransitive verb;

however, in certain constructions, when it acts as an auxiliary verb, it is treated as a

transitive verb. This will be further looked at in a later section.

Transitive verbs can be used in their infinitive forms with the verb zeñ in order

to form causative sentences.

Be zedrisa ston da zeñ csalas. “Mother made me speak to him.”

Phthaena ledhoryn da zeñ ñul aeral. “The cold air made me close the door.”

Alternitively, the preposition dho with a noun in its genitive form can be used

to form a causative sentence.

Dho csaly be zedrisa ston das. “Because of mother, I spoke to him.”

Dho ñuly aery phthaena ledhoryn das. “Because of the cold air, I closed the door.”

6.2. Intransitive Verbs, Participles, Negation, and Interrogatives

Intransitive verbs, as previously mentioned, always come at the end of the

sentence in the past and non-past tenses. They lose their infinitive endings and take on

a tense ending.

Infinitive Tense Ending Example Translation

Non-Past

Past

-ñ→

-ñ→

-l

-s

da crel

I go/come

da cres

I went/came

The past and present participles of both transitive and intransitive verbs are

formed in the same manner.

Infinitive Tense Ending Example Translation

Present Particple

-ñ→

Past Participle

-ñ→

-l

-s

bzhal

doing

crel

going/coming

bzhas

done

cres

gone/come

The participles can then be combined with the verb wiñ to express the stative

passive voice and continuous aspect. The terminative prefix le- is optionally attached

to the past participle denoting a result or termination of an action; this distinguishes

whether it is stative or dynamic (more verbal prefixes will be discussed later).

Lebzhas wim bal. “It is done/over.”

Du (le)gzas wiñ gas. “You were (already) seen by me.”

Du elbhise (le)gzas wiñ gas. “You were seen together with me.”

Durmoch anul win dal. “I am sitting outside the house.”

Csalu zedrisa stol wim bas. “She was talking with Mother.”

The past participle can also be combined with the verb ardheñ (treated

transitively) to form the dynamic passive voice.

Shelunuñ (le)boras ardheñ swadhmelas. “The fruits were picked last month.”

Dusuñ mierguñ (le)rwes ardheñ zbhalal. “The petals get covered in dew every night.”

Haemu (le)bis ardheñ wilbhal. “The roof is getting hit by rain.”

Du (le)gzas ardheñ gas. “You were being watched by me.”

To negate a sentence, the suffix -en is placed after the tense ending. This

applies to both transitive and intransitive verbs.

Da mile cresen. “I did not go to the sea.”

Durmaph win dalen. “I am not at home.”

When forming a yes/no question, the suffix -o is placed at the end of the

sentence, and, when asking a negative question, the e in the -en is dropped.

Ga mile creso? “Did you go to the sea?”

Ga mile cresno? “Didn’t you go to the sea?”

Durmaph wiñ galo? “Are you at home?”

Durmaph wiñ galno? “Aren’t you at home?”

How to reply ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to such a question depends on the transitivity of the

verb. If the verb is intransitive, then the verb is repeated with the tense ending, either

non-negated for ‘yes’ or negated for ‘no’. If the verb is transitive, however, then the

pronoun of the subject is said with a tense ending; without the negative ending it

means ‘yes’ and with a negative ending it means ‘no’.

Ga mile cresno? ‘Did you go to the sea?’ > Cresen. ‘No.’

Durmaph wiñ galo? ‘Are you at home?’ > Dal. ‘Yes.’

“Wh…” questions are based around the inflection of the pronoun clibha. Such

questions do not take the interrogative suffix, as it is implied from the use of the

pronoun. The word clibha can also be used as an adjective to express ‘which’.

Clibha bzhañ gal? ‘What are you doing?’

Clibhe ga crel? ‘To where are you going?’

Clibhise ga crel? ‘From where do you come?’

Clibhu bhdhwores wiñ gal? ‘How are you called?’ (‘What is your name?’)

Di wiñ clibha durmal? ‘Which house is yours?’

Clibhin pustin sphureñ gal? ‘In which forest do you live?’

Most intransitive verbs can be made causative by simply treating them as

intransitive verbs.

Da durme cres. > Durme da crethañ csalas.

“I went home.” > “Mother made me go home.” (“Mother moved me home.”)

Ba zlurys. > Ba zluryn das.

“She died.” > “I made her die.” (“I killed her.”)

Zbherma zeral. > Zbherma zeran nwethal.

“The leaves flutter.” > “The wind makes the leaves flutter.”

Some intransitive verbs, however, require the use of the prepisition dho with a

noun in its genitive form to form a causative sentence.

Da znalys. > Dho gi da znalys.

“I jumped.” > “You made me jump.” (“I jumped because of you.”)

Wuryl wim bal. > Dho di wuryl wim bal.

“She is crying.” > “I made her cry.” (“She is crying because of me.”)

6.3. Irregularities and Dual-Transitive Verbs

When a verb in its infinitive form ends with a syllable containing the vowel y,

the y changes to i if a tense ending replaces the infinitive ending.

luryñ ‘to get/sit up’ > luril/s

Ba aerthise luris. “He got up off the ground.”

Two types of irregular verbs exist in Classical Dryadic – those that end in -elñ

and those ending in -ebhñ (both pronounced -uñ). Their transitive linking form is the

same as their infinitive form except for the nasalization of the ending. When put in

their intransitive past and non-past forms the infinitive ending is removed and

replaced with -u followed by the tense ending. This is also true for the construction of

the participles of such verbs. The following chart demonstrates this using two dual-

transitive, irregular verbs, bebhñ (to break) and belñ (to pull/stretch), which are

pronounced the same in their infinitive and linking forms.

Infinitive

Linking Non-Past Past

Trans

bebhñ

bebhñ(/n/m)

bebhul

bebhus

Intrans

bebhñ

–

bebhul

bebhus

Trans

Intrans

belñ

belñ

belñ(/n/m)

belul

bebhus

–

belul

belus

Some verbs, as seen briefly above, can act as both transitive and intransitive,

often changing their meaning. Some examples of this are soryñ, chlebhyñ, creñ, etc.

Milaera soryñ zhor soral. “The summer sun warms the water.”

Da soril. “It is warm.” (“I feel warm.”)

Cedhiuna crem bas. “He moved the box.”

Laerthe ba cres. “He went to the temple.”

6.4. Speech Levels and Honorifics

Classical Dryadic society was extremely hierarchical and the language reflects

this through its six distinguished speech levels or registers which are determined

based on who is talking to whom. These speech levels are primarily expressed

through suffixes placed at the end of the sentence after the tense endings. The highest

register is even further distinguished through separate vocabulary.

Level

Suffix

Use

High

Sacred

-aroñ

with deities, fathers, sacred trees

Formal

-oñ

with mothers, elder sisters, warriors, strangers

Mid

Informal

–

with one’s self, friends, younger sisters, writing

Low

Subordinate

-ish

with saplings, inferiors (mother > daughters)

Vulgar

-izhem

with someone/something that angers you

The highest register, also called the ‘sacred register’, uses the suffix -aroñ. It is

primarily used when talking indirectly to deities, natural forces, father trees, or trees

revered as sacred and is commonly used in religious dialogue and rituals.

Artymisayoñ, bhedu s’arzha phsethameph thaelsebhayaroñ.

(Dear Artymis, guide me with your light.)

The next highest register is the formal register, which uses the suffix -oñ. It is

used when talking to one’s mother, elder sisters, warriors or other high-class dryads,

and strangers from another clan.

Csalayoñ, nezhluñ milbhishe da creloñ.

(Today I will go to the river, Mother.)

The middle or informal register takes on no suffix and is used when talking to

oneself, friends, younger sisters, and when writing.

Norbhalae, sichros cliva bzhañ gal?

(What are you going to do now, Norbhal?)

The middle-lower register, or subordinate register, uses the suffix -ish and is

used primarily by someone of higher standing talking down to someone of lower

standing, for example a mother talking to her daughters.

Di chwynae, clibhe aerthe ga crelish?

(Whither do you go, my child?)

Finally, the lowest register, otherwise known as the ‘vulgar register’, expressed

with the suffix -izhem, is used when one is angry or disgusted at someone. This

register is considered extremely taboo and disrespectful, and its use is thus limited in

everyday discourse.

Gruzhbhizhem, csala gia gruzyn dalizhem!

(Bastard, I will burn your mother!)

These speech level suffixes combine with other suffix endings. The following

chart shows some of the basic combinations of tense suffixes and speech level

suffixes. Notice, for instance, the e in the negative suffix -en disappears with the

addition of an extra ending suffix. Furthermore, many of the speech level suffixes do

not have a separate interrogative form.

Non-Past/Past

Aff

Neg

Int

Int-Neg

Sacred

-laroñ

-lnaroñ

-laroñ

-lnaroñ

Formal

Informal

-saroñ

-snaroñ

-saroñ

-snaroñ

-loñ

-soñ

-l

-s

-lnoñ

-snoñ

-len

-sen

-loñ

-soñ

-lo

-so

-lnoñ

-snoñ

-lno

-sno

Subordinate

-lish

-lnish

-sish

-snish

-lish

-sish

-lnish

-snish

Vulgar

-lizhem

-lnizhem

-lizhem

-lnizhem

-sizhem

-snizhem

-sizhem

-snizhem

Along with speech levels, Classical Dryadic also utilizes an honorific infix, –

tha-, which is placed on primary verbs. This honorific infix is only used when the

subject of the verb is a person of honor or respect (i.e. a mother, elder sister, etc.).

This also holds true when a pronoun is the subject of the verb, and the pronoun refers

to a person of honor or respect.

Rozhiscin ga gzathañ csalas. “Mother saw you in the garden.”

Ge zedrisa stotham babhial. “She wishes to speak to you.”

Some verbs, however, are irregular have entirely separate honorific forms or

counterparts and do not take on the honorific infix. These include verbs such as wiñ,

ardheñ, bruñ, and zeñ, which respectively have the honorific forms ithañ, chliseñ,

duthañ, and thañ.

Durme cres wim bal. > Durme cres itham bal. (She has gone home.)

Du sphurise g’ardhel. > Du sphurise ga chlisel. (I like you a lot.)

De ersa brum bas. > De ersa dutham bas. (She apologized to me.)

Du ers’señ gal. > Du ersa thañ gal. (I love you.)

6.5. Aspectual and Modal Affixes and Verbal Prefixes

Classical Dryadic utilizes special affixes that denote modality and aspect and

combine with the previously mentioned tense and speech level affixes. The following

chart denotes these affixes:

Affix

Construction

Meaning

Volition

-bhia- N/V + -(a)bhia- + -l/s(en)

to want to

Obligation

-ya-

N/V + -(a)ya- + -l/s(en)

to have to, to ought to

Recent-Perfect/

Simplicative

-ium

N/V + -l/s(n) + -ium

just, only, simply

Prospective

-iuch

N/V + -l/s(n) + -iuch

to be about to

The volition affix denotes a desire or intention to do something and the

obligation affix denotes a necessity to do something or something that should be

done; they are both placed before the tense suffix.

Ge bhemila nuston dabhial. (I would like to tell you a secret.)

Ge clibhda duthañ csalabhias. (Mother wanted to give you something.)

Dusa zedrisa chelse ardheyal. (All trees must grow upwards.)

Durme mrecrem bayas. (She had to return home.)

The recent-perfect/simplicative suffix expresses that something recently took

place in the past, or that something merely is in a specific state or simply happens in

the present (and in some cases the past). The prospective suffix expresses anticipation

for a future situation. If the situation is referred to in the past, then the situation did

not come to pass. Both the recent-perfect/simplicative suffix and the prospective

suffix are placed after the tense suffix (but before the speech level suffix).

Durme lecres win dasium. (I have just arrived at home.)

Arzhu peghos win dalium. (I’m just so tired.)

Ba gzan dabhiasnium. (I simply didn’t want to see her.)

Aertha phlon daliuch. (I am about/going to eat dinner.)

Da cru bim basiuch. (She was about to hit me with a stone.)

Classical Dryadic also has several verbal prefixes which can function as both

derivational and inflectional prefixes:

Prefix

Meaning

Example (creñ)

Durative

ze-

lasting for only a certain amount of

time or temporarily

zecreñ

(to go for a

walk/moment)

Quietive

nu-

denoting an action done quietly or

nucreñ

calmly, possibly in secret

(to sneak/tiptoe)

Repetitive

mre-

Terminative/

Perfective

Inceptive/

Inchoative

le-

she-

denoting an action happening once

mrecreñ

again, repeating an action

(to return)

finishing or bringing something to an

lecreñ

end

(to arrive)

starting something or beginning a

shecreñ

new action

(to leave/depart)

Interminative

zle-

something that is ongoing or endless

zlecreñ

(to never return)

The terminative/perfective prefix is often used with the past participle,

especially in passive constructions.

Durme lecres win dal. (I am come home/I have arrived at home.)

Lebzhas win thuñmal. (The work is complete/done.)

Lebzhas ardhen thuñmal. (The work is being done.)

Oftentimes the addition of this prefix is optional and may be left off. The

prefix, in these instances, is thus used for emphasis on the completion of the action or

event.

Du elbhise (le)gzas ithañ csalas. (Mother was seen together with me.)

Csalu de (le)stos ardheñ zedrisas. (I was being spoken to by Mother.)

6.6. Emphatic Suffixes, Imperative Mood, Evidentiality, and Noun Clauses

Classical Dryadic utilizes special emphatic suffixes which are further used in

the construction of the imperative and an evidentiality suffix. These three suffixes and

their formulations are seen below:

Emphatic

Imperative

Indirectivity

Construction N/V + -(a)l/s +…

N/V +…

N/V + -(a)l/s +…

Sacred

Formal

Informal

Subordinate

-ayaroñ

-(a)bhayaroñ

-arayaroñ

-ayoñ

-(a)bhayoñ

-arayoñ

-ae

-ish

-(a)bhae

-(a)bhish

-arae

-arish

Vulgar

-izhem

-(a)bhizhem

-arizhem

The emphatic suffix is used when placing emphasis on the verb or action

being performed and when making an assertion. It can sometimes help to denote a

future activity that the speaker is certain will or will not happen. The suffix can also

be used when answering yes or no to emphasize or assert one’s answer.

Gu elbhise crelnae! “I will NOT go with you.”

Ba gzañ gasno? “Didn’t you see it?” > Dasnae! “No! I did not.”

The imperative is used for expressing commands or requests, including the

giving of permission and prohibition. The imperative mood is always used with the

emphatic suffix; however, the actual imperative mood is expressed through the

affixation of -(a)bh- in its construction.

Dwen ga shecrebhnae! “Don’t leave without me!”

De ñwela zedrisa stoñ gabhnish. “Do not speak to me like that.”

Ers’sen dabhayoñ. “I’m sorry.” (“Please allow me to blossom.”)

The evidentiality or indirectivity suffix, which also uses the emphatic suffix in

its construction, is used to show that evidence exists for a statement. It is usually used

for stating something that is expected to be known or that it is obvious.

Shiera du ghrise ardhelarae! “I hate fire (and you know this)!”

De zedrisa stom babhialnarae! “He doesn’t want to speak to me (and you know this)!”

This suffix may also be used to create an indirect quotational clause or a noun

clause, when pairing it with verbs such as ston (to say/think), ñrun (to know), arzhin

melyñ (to hope), arzha (sieria) ghreñ (to worry), etc. When using speech level

suffixes, they apply only to the final or main verb, not to the verb that is part of the

quotational or noun clause, which takes on the neutral or informal emphatic suffix.

Csale zedrisa stom balarae stom bas. “She said that she will speak to Mother.”

Dusa sphurise ardhelarae arzhin melyn dal. “I hope everything will be fine.”

Ga zlurilarae ghren di arzhal. “I worry that you will be killed.”

The neutral or informal interrogative suffix can also be used to create an

indirect quotational clause or a noun clause, when paired with verbs such as ston (to

ask), ñrun (to know), arzhin ardheñ (to wonder), arzha ghreñ (to worry), etc.

Mile da crebhialo de stom bas. “She asked me if I wanted to go to the sea.”

Zdu elbhise aertha flom balo ñruñ galo? “Do you know if she will eat with us?”

Nezhluñ csala gzañ zdalo arzhin ardhen dal. “I wonder if we will see mother today.”

Emphatic suffixes can also be attached directly to adjectives to form an

interjection, usually to make an exclamation about something observed or to offer a

quick response to something.

Emphatic Suffix Example

Sacred

Formal

Informal

Subordinate

-ayaroñ

sphurayaroñ

-ayoñ

sphurayoñ

-ae

-ish

sphurae

sphurish

Vulgar

-izhem

sphurizhem

The following are some examples of adjectives commonly used with an

emphatic suffix and their approximate English equivalents.

Sphurae. “Nice!” “Well then.” “Okay.”

Ñwelae. “True.” “I agree.” “Yeah!”

Ghrae. “Ew!” “That’s not good.” “Uncool.”

7. Relative Clauses and Complex Sentences

7.1. Relative Clauses