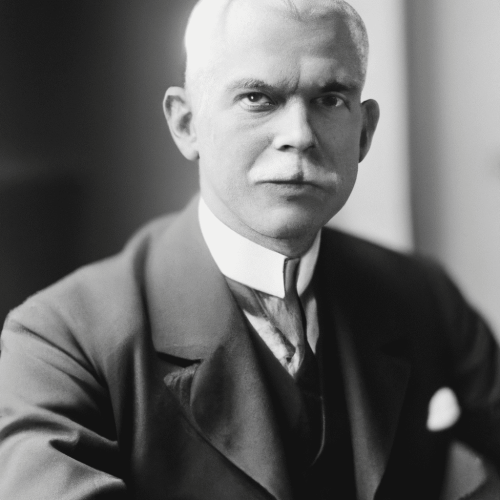

William Mitchell (1861—1962)

Sir William Mitchell was the first major philosopher to live in South Australia. He worked at Adelaide University from 1895 to 1940 primarily in the area of what is now known as cognitive science. His major work: Structure and Growth of the Mind is a treatise on philosophical psychology.

Mitchell anticipated the claims of Nagel, McGinn, and Chalmers and their emphasis on the nonreductive character of subjective experience. He also anticipated the themes associated with perceptual plasticity, developmental accounts of modularity, and connectionism.

Mitchell’s non-reductive view of experience is historically awkward to place between Australia’s 19th century idealism and 20th century radical materialism. Mitchell thought the mind was a structure reacting to the environment. These reactions constitute experiences, through which objects can be known, similar to idealism. Studying these experiences provide “direct” evidence (or data) of the mind. Mitchell also recommended the study of the brain, which provides “indirect” evidence of the mind. The (then) emerging sciences, such as neuroscience, provide an important but limited explanation of the mind. This distinguishes Mitchell from most present contemporaries.

Mitchell explains the growth of the mind through three kinds of content found in experience: feelings, interests, and actions. Experience begins by sensations or by what we feel, which develop into interests of various levels of perception, which in turn may result in action. Although some psychologists and philosophers, like Piaget and Nagel, later present accounts similar to the idea of mental growth, most contemporary accounts of mind focus on the indirect methods or on representational and computational functions of the brain. Contemporary accounts sympathetic to non-symbolic modal information processing may find interest in Mitchell’s work.

Table of Contents

Biographical Sketch

Scottish and Australian Philosophy, The Background

Idealism

Realism and Materialism

Psychology

Neuroscience

Contemporary Philosophy of Mind

Mitchell’s Philosophy of Mind

Contemporary Cognitive Science

Why Mitchell has been Forgotten

References and Further Reading

1. Biographical Sketch

William Mitchell was born in Inveravon in north Scotland in 1861, the son of a hill farmer. He was one of six children. Before he died in 1962 at the age of 101, he had distinguished himself both as Vice Chancellor (1916-1942) and later Chancellor (1942-48) at the University of Adelaide in South Australia. He held the Hughes Chair in English Language and Literature and Mental and Moral Philosophy, and was the first (and to date only) philosopher working within Australia to give the Gifford Lectures at the University of Aberdeen. This he did in 1924 and 1926. In 1927 he was knighted for his services to South Australia (Miller, 1929, p. 248).

In South Australia, Mitchell is remembered as an important figure at Adelaide University. He is certainly well-known for his contributions to scholarly life: this included obtaining grants for the University; founding the chair of biochemistry; spending large sums on library acquisitions; making many administrative contributions (the neo-Gothic Mitchell Building on North Terrace in Adelaide is named in his honour). However, he was also a first-rate philosopher. He published his first paper in Mind while still an undergraduate, and later, two discursive and wide-ranging books with MacMillan; the first entitled: Structure and Growth of the Mind (1907) ranged over issues in mind and content, philosophical psychology and neuroscience; the second The Place of Minds (1933) covered issues overlapping mind and the philosophy of physics, including the then relatively new area of quantum mechanics. The only copy of the third manuscript The Power of Mind—part of the trilogy—is said to have been lost during the London bombing raids. There are surviving manuscripts of this last book and proceedings of it as the last in the series of Gifford lectures—none of which, however, have ever reached print. There are also a number of shorter papers including: “Nature and Feeling”, “Universities and Life”, “Reform in Education”, “Christianity and the Industrial System”, “The Quality of Life”, and others, which were published as monographs by the Hassell printing company in Adelaide. Mitchell was also a regular contributor to the early editions of the Mind journal and regularly wrote shorter topical pieces for the Murdoch paper, The Advertiser, when it was a newspaper of some repute.

As a teacher and academic, Mitchell was highly regarded and something of a polymath, being engaged to teach economics and education as well as philosophy, psychology and literature. It might be disputed how much teaching he actually did in economics and literature—though a recent publication claims that he taught economics four evenings a week in addition to his other duties as professor of philosophy and a Vice Chancellor (“Economics at Adelaide”, 2003, p. 15). There is no doubt that he was a man of considerable energy. For this reason perhaps he described his chair, not as a chair but a sofa. He was also an unpretentious character. It is said, for example, that he didn’t have need for a room in his capacity of Vice Chancellor. If he wanted to see someone on an administrative matter, Mitchell would see them in his room. (Smart, 1962). Because of his considerable abilities as an academic, administrator, and intellectual/social commentator, Duncan and Leonard describe Mitchell as “the nearest approach to a philosopher-king the academic world has ever seen” (Duncan and Leonard, 1973, p. 78; Trahair, 1984, p. 52).

Mitchell always considered himself to be, first and foremost, a philosopher (Smart, 1962). He was, arguably, Australia’s first significant philosopher. Yet, curiously, he is not remembered at all as such. In academic terms, he is today a largely forgotten figure. The last serious discussion known to appear in print on Mitchell’s work was probably in Blanshard’s Nature of Thought in 1939; the last review of his books appeared in 1934 (Harvey and Acton wrote reviews in the same year; an earlier review by Hoernlé appeared in 1909); the last postgraduate dissertation in 1984 (Allen, 1984, see also Allen, 1995). No mention is made of Mitchell in contemporary philosophical writing (although see Boucher, in press). In Honderich’s Dictionary of Philosophy, Mitchell’s main work, Structure and Growth of the Mind, is described as the last remaining example of Australian idealism which “still survives” (Honderich, 1995, p. 67). If it survives at all, it certainly doesn’t survive by very much.

2. Scottish and Australian Philosophy, The Background

Although much had been written on early Scottish philosophical influences on the development of Australian philosophy, the focus of this work has centred mainly on the Sydney connection—particularly, the writing and influence of John Anderson, Challis Professor of Philosophy at the University of Sydney (1927-58). (See Anderson, et al., 1962; Anderson, 1980, 1982; Kennedy, 1995; Coombs, 1996; Baker, 1979, 1986; Mackie, 1962, 1977). In contrast to the Andersonian influence, little scholarly work had been undertaken on what impact, if any, Scottish traditions had on philosophical writing elsewhere in Australia.

Western philosophical thought made an appearance in Australia long before Anderson arrived in New South Wales, yet it may be forever overshadowed by Anderson’s legacy. From approximately 1850 a small community of scholars—mostly of Scots origin—working against the considerable difficulties of time and distance (both among themselves and also between them and their colleagues in the northern hemisphere) managed to bring together a philosophical community in Australia, add to the then dominant idealist and quasi-religious debates which occupied the intellectual scene in America and Europe, and leave behind a number of manuscripts and assorted papers which provided the basis for the metaphysical and epistemological work of those that followed. These scholars included Barzillai Quaife, John Woolley, Charles Badham and Francis Anderson in Sydney; M. H. Irving, H. A. Strong, W. E. Hearn, Richard Hodgson, Alexander Sutherland and Henry Laurie in Melbourne; William Mitchell and John McKellar-Stewart in Adelaide; Elton Mayo and Scott Fletcher in Queensland; R. L. Dunbabin in Tasmania; and P. R. Le Couteur and A. C. Fox in Western Australia.

Any systematic survey of the earliest Australian philosophers and their ideas is beyond the scope of this article. For a comprehensive review, see, Grave, 1984. However, it is necessary to mention the background of those philosophers in broad terms before turning to the subject of this article—William Mitchell. Mitchell spanned two groups of philosophers having very different concerns: the idealist and “common-sense” philosophers who worked from the mid to late 1850s until the late nineteenth century; and, what might be called the realist and materialist revolutionaries beginning in Australia in the early twentieth century with fellow-Scot John Anderson, and later dominated by the work of J. J. C. Smart, U. T. Place, D. M. Armstrong, C. B. Martin, and others—a “school” now known internationally as “Australian Materialism” (all except Armstrong were based in Adelaide). Any understanding and appreciation of Mitchell’s work, must be understood in the context of these two very different traditions.

Mitchell was the product of an old and vibrant school of philosophy which had its roots in the Scottish traditions of idealism and “common-sense” philosophy. The dead hand of idealism and the consequences it had for philosophical realism was one of the influences which gave rise to Mitchell’s work. Other early Australian philosophers before, during and after Mitchell’s time also owe their foundations to these traditions. In brief, these influences can be summarised as follows: from the common-sense philosophers such as Thomas Reid (1710-1796), Mitchell accepts the arguments advanced against solipsism and anti-realism, and the idea that the mind may exhibit different information-processing hierarchies. From T. H. Green (1836-1882), Mitchell derived the idea that an uninterpreted sense datum was simply folly. From F. H. Bradley (1846-1924), Mitchell takes the idea that experience—at least initially—is a seamless unity of knower and known. From James Ward (1843-1925), Mitchell takes the important idea that organisms grow, and that an adequate explanation of mental activity must capture this. From William James (1842-1910), Mitchell adopts a version of realism. Each of these ideas are represented in one way or another in Mitchell’s thought.

However, there was another influence on Mitchell’s philosophical development: the challenges forced by the growing relevance of the physical sciences to philosophical speculation about mind. Developments in physics, psychology and neuroscience, for example, were considerable influences at the time Mitchell was working. Both these influences conspired, not intentionally but effectively, to bring about a materialist reaction to idealism that, for better or worse, shared more of its idealist ancestry than the materialism we know today. Consequently, this flavored Mitchell’s work in Australia during the same period. The implications of them for Mitchell’s thought are mentioned below.

a. Idealism

Mitchell is not an idealist in the strict sense, though he certainly came from the idealist tradition. Some of his more shaky arguments even turn on idealist assumptions. This should not be surprising. Mitchell’s views, after all, descend from the influence of the British idealists, T. H. Green and F. H. Bradley, among others, who endeavored to push the empiricist views of Locke and Hume closer to the views of the German idealists. On the other hand, Mitchell was also impressed by the arguments of his compatriots T. Reid, D. Stewart, J. Beattie, W. Hamilton—the Scottish “common sense” theorists, who attacked idealism and tried to outline a doctrine closer to what we would now call “realism”. While it should be acknowledged that idealism is a broad church, and can encompass a wide variety of positions, on balance, Mitchell’s views are best placed at the beginning of another tradition entirely.

Mitchell’s views demonstrate cautious materialist and non-doctrinaire realist themes—themes which have more in common with contemporary philosophical work (for example, current work in cognitive science) than with the idealist tradition; views which are also indicative of the region of the world in which he worked. His writing is best described as marking a transition between the idealist tradition which arrived on Australian soil in the early part of the nineteenth century, and the more radical materialist views which followed (especially in Adelaide)—but, strictly speaking, he belonged properly to neither tradition. There is no doubt that Mitchell wrote like an idealist—sometimes argued like one—but there is an ambiguity in his work which seems to indicate that he was attempting to stake out a position that, for the time, was genuinely original. If he was an idealist, he was only a methodological idealist.

b. Realism and Materialism

There is a light-hearted reason why Mitchell should not be seen as an idealist: for were it so, it would stand as an anomalous case to the oft-quoted remark of Armstrong (and quoted by Devitt, 1984, p. vii) that realism is born only of dry countries with harsh landscapes and strong sunlight, whereas anti-realisms are born of moist countries with misty air and green landscapes where the mind is allowed to wander. (Devitt even claims that a bastion of idealism still survives in Victoria where the sun doesn’t shine quite as much.) Since Mitchell spent most of his philosophical life in Australia—and in the very harsh climate of South Australia—it would be unfitting that, if he was an idealist, he would remain one for long. J. J. C. Smart remembers Mitchell regarding himself as a staunch realist. One recollection recalls Mitchell in conversation with a solipsist: “You know, the trouble with you, is that you think only minds exist”, and adding (under his breath) “and your mind at that.” (Edgeloe, 1993). Not the kind of remark an idealist would make. And, it is certainly not like an anti-realist to make claims such as the following: “No object is made mental, nor altered, by being felt, imagined, or known in any way” (PMW, p. 33) and: “When your ideas quarrel with mine, and when they agree, it is because they….grasp the same object as mine, and to find it independent of our grasp” (PMW, p. 45). Or, finally, his claim: “The room is….not affected by my perceiving it” (SGM, p. 60). If Mitchell is an idealist, he is an unusual one indeed. However, if he is a realist, as Mitchell himself claimed, we may see his pronouncements to the contrary as mere epistemological lapses—perhaps even forgivable ones given the preoccupation of early Australian philosophers with the idealist curse.

Just as Mitchell was no idealist or antirealist, it is also clear that he was no anti-materialist. There are a number of passages which indicate this. Here’s one example (recall that is was written before 1907):

When you try to picture the structure and the action of the mind, remember you are trying to picture the structure and action of the nervous system. In this way you will avoid the usual confusion of trying to picture a hybrid process consisting partly of visible movements and partly of invisible feelings (SGM, p. 7).

It is not unreasonable, therefore, to look for evidence of realist and materialist themes in Mitchell, given that he worked here and not in the misty green landscape of Scotland, and given such pronouncements as those above. It should certainly not be automatically assumed that his views are similar to the tradition from which he descended. I shall submit that Mitchell’s work should be reconsidered in the light of contemporary philosophical debates. Perhaps J. A. Passmore was only partly right when he described Mitchell’s work as articulating “an introduction to an Idealist philosophy for which the mind is the central ontological conception” (Passmore in McLeod, 1963, p. 146). While it is certainly true that, for Mitchell, the role of the mind is a pre-eminent consideration, this doesn’t by itself make him an idealist. The common qualification for being an idealist is that what is real is in some way confined or at least related to the contents of our minds (Honderich, 1995, p. 386). And the evidence for this in Mitchell’s writing is somewhat less clear.

c. Psychology

Aside from the Scottish idealist and common sense traditions, there were other influences which complicate the picture further. These influences indicate that Mitchell was a more sophisticated philosopher than previously thought. These influences came from the discipline of psychology. Mitchell was a near contemporary of the Swiss psychologist Piaget, who argued for an epistemology which was both dynamic and materialist—setting the stage for a later cybernetic approach to epistemology. (Piaget published his first substantial works in 1923, some 16 years after Mitchell’s SGM). Mitchell articulated a kind of early dynamic process philosophy of the structure and growth of the mind which anticipated some of Piaget’s account later to receive wide acclaim in the philosophy of psychology. There are considerable differences here, of course. Whereas Piaget aimed at a strictly empirical developmental psychology underpinned by the influence of some Aristotelian, Kantian and Hegelian philosophical conceptions (with empirical work predominating), Mitchell aimed at—in Passmore’s words—”a psychology which is in turn an introduction to philosophy” (Passmore, 1963, p. 145). That is, a psychology which leads to a new way of thinking philosophically about the mind. Indeed, for Mitchell, philosophy was a kind of psychology.

While there are differences between the two thinkers, there are also similarities: unlike the focus of contemporary philosophy of mind (which deals centrally with ontological questions such as what the mind is—how a neural state can be a representational state, for instance), both Mitchell and Piaget seemed more interested in how the mind grows (how the mind of an infant is different from the mind of an adult; a learned mind differs from one which exhibits “invincible stupidity”; how the minds of lower animals differ from those of primates; and so on.) It was, in other words, an entirely different philosophical agenda. The issue of what minds are was, for Mitchell and his contemporaries, subordinate to the issue of what minds do. Structure and Growth of the Mind is, broadly speaking, an attempt to outline the precise processes undergone by minds during different stages of their growth, and under different conditions. It might be considered a conceptual psychology—or an analytic phenomenology—of the stages of mental growth. And, the central category of this “psychology” was the category of experience. This way of looking at things is currently out of favor among philosophers of mind, though it does seem to be making a come-back (see for example, Karmiloff-Smith’s amalgamation of Fodorian modularity theory and Piagetian themes) (Karmiloff-Smith, 1992).

Other psychologists to influence Mitchell were Wundt, Helmholtz and Stumpf. Additional strong influences on his work come from ethology and related disciplines. For example, Mitchell approvingly cites Lubbock’s work on the senses of insects (Lubbock, 1888, cited in Mitchell, 1907, p. 39 passim) and Preyer’s and Münsterberg’s views about the behavior of lower animals. These influences seem to discredit the claim that Mitchell was an ontological idealist. He was more interested in a naturalist account of mind and content. And he was certainly more interested in evidence from emerging sciences than the inchoate ramblings of British and German idealists (there are no references to either in his books).

d. Neuroscience

Were Mitchell an antimaterialist of some conviction, we might expect rather less of this material to feature in his writings. Yet Mitchell devotes an entire chapter reviewing the then current work in neuroscience, and much of the rest of his work is sprinkled liberally with evidence from such sources. He looks at experiments involving prosthesis and brain bisection, conjectures about differently weighted neuronal paths in animals, and so on. He called this evidence the “indirect” method of understanding mind—indirect because it relied on evidence from the brain, not “direct” evidence from experience as it seems to us, that is, not phenomenological content. Moreover, Mitchell seemed to believe that any proper understanding of mind required an analysis in which evidence from both sources was required. He didn’t think that one needed to be subordinated to the other. Mitchell “saw in psychological and neurological inquiry alternative means of explanation—the philosophical being the more “direct”—rather than attempts to describe entities of a different ontological order” (Passmore, 1963, 147).

3. Contemporary Philosophy of Mind

In contemporary cognitive science, philosophers refer to the “easy” and the “hard” problem of consciousness. The “easy” problem consists in how brains might do things such as represent perceptions in thought in a neural or computational form. The “hard” problem consists in explaining how things seem to us in experience (the “what it is like” of consciousness) (Chalmers, 1996). Many contemporary cognitive scientists believe one can’t understand mind without an understanding of the “hard” problem, as this requires an understanding of “subjectivity”, or experience “from the inside.”

This distinction approximates Mitchell’s “indirect” and “direct” distinction to this extent: While the “indirect” method offers a potentially complete understanding of “the immediate physical correlates” (SGM, p. 450) of experience, only the direct method offers an understanding of what experience is like “from the inside”. Both approaches, according to Mitchell, are essential. While Mitchell did not have the conceptual resources to understand features of mind that we have today (courtesy of the modern computer and its binary method of information storage), he did have enormous faith that the indirect method would yield considerable insights; hence his emphasis on neuroscience. In the final chapter of SGM, Mitchell even sketches what an indirect account might look like—an account which has a startling resemblance to recent “connectionist” models (McClelland, 1999; McClelland and Rumelhart, 1986).

However, while he thought this important, he also thought that this could only ever be a “correlate” of mind as it is experienced by us. Thus, he argued for a cautious, non-reductive physicalism and rejected materialist accounts which promised more. One certainly can’t understand mind without both the “direct” and “indirect” methods according to him. Mitchell’s account of mind, to the extent that it makes a contribution to such views, is thus historically relevant to the debates in present day philosophy of mind.

It could even be argued, that Mitchell anticipated the views of contemporary theorists such as Thomas Nagel, Colin McGinn and David Chalmers—the “new mysterians”, as they are sometimes disparagingly called. These theorists argue, in very different ways, for the claims that: 1. the subjective quality of experience is essentially dissimilar from objective descriptions of brain states; and 2. the current brain sciences are limited in their application. They are united in their view that, while the evidence from the neurosciences is impressive, these results don’t tell us anything about consciousness properly so-called, even though they might tell us a good deal about associated problems to do with mentality (how a propositional attitude can be a representational state, and so on). They are also united in their regard for the importance, and non-reducibility of subjective experience.

None of the “new mysterians” are dualists by fiat (although many of them openly espouse dualism); they are, rather, unconvinced that a materialist theory of mind in its present form will do the job. Materialism can’t be said to be false—indeed, Nagel states this much explicitly (Nagel, 1979, pp. 175-6). Chalmers, likewise, exhibits a reluctance to say that materialism can’t at present do the job required, and advocates a monism which is “broader”. So it seems that the new mysterians are not hostile to materialism—only unwilling to take it seriously as a complete theory of mind (this point is not often stressed in the literature). The theory of mind they argue for would have to offer an account of the subjective character of experience without attempting to eliminate, reduce or otherwise distort the “what it is like” of phenomenal experience. To paraphrase Chalmers, the right theory of consciousness will have to “feel the problem [of subjective experience] in its bones”. One can, perhaps, describe the new mysterians, in a very liberal mood, as very cautious materialists (so cautious as to support dualism or panpsychism). And, in this sense, Mitchell was one too—though he doesn’t reach such radical conclusions.

The other point worth noting is that Mitchell also anticipated the views of some contemporary cognitive scientists, especially those theorists who are somewhat sympathetic to the claims of the new mysterians but who don’t wish to be tarred with the same “new mysterian” brush.

Where is the evidence that Mitchell anticipated such views? Briefly, though not conclusive evidence on its own, some of his remarks about mind do see him articulating a position which has similarities with some of these more recent theorists:

A mind and its experience are realities that are presentable to sense as the brain and its actions. In that respect the mind and experience are not parallel with nature, but part of it. And, on the other hand, the facts of nature, including the brain, whenever they are phenomena, are not parallel with mental phenomena, but part of them (SGM, p. 23).

In one sense, it is easy to see why the American idealists in the 1930s embraced such comments (see Blanshard, 1939, for extensive reference to Mitchell’s writing). On one reading they seem to suggest that Mitchell thought the brain might be a product of minds: whenever brain states are “phenomenal” states, they are mental phenomena, he seems to say. Given his outright rejection of idealism, and his own insistence that he was a realist, other interpretations of his remarks seem called for. Another, more benign reading is that Mitchell was arguing a similar line to that of Thomas Nagel’s “Dual Aspect” theory: According to Nagel’s account, “both the mental and the physical properties of a mental event are essential properties of it—properties which it could not lack” (Nagel, 1986, p. 48). This too can be a way of interpreting Mitchell’s assertion above. This reading makes no such commitment to idealist doctrines and seems to suggest that Mitchell was trying to outline a kind of non-reductive account in which mental and physical states both feature in a more inclusive account of mind—a “fundamental” theory incorporating both. This too is the emphasis in the theories of Chalmers and McGinn (Chalmers, 1996; McGinn, 1983). Mitchell’s account also bears close similarities to Sellars’ articulation of the “manifest” and the “scientific” images (Sellars, 1963).

Gone are the days, it seems, of either being a realist and materialist, or an idealist and/or dualist, and shunning the possibility of intermediate positions. Now, it seems, empirically-minded philosophers seriously entertain alternative accounts; theories of which Anderson, no doubt, would have disapproved (Cantwell-Smith, 1996; Marshall, 2001). Chalmers is an example of an Australian who has attempted to stake out such an account, though there are others: Keith Campbell and Frank Jackson are examples of contemporary Australian dualists or qualiaphiles, as they are called; though Jackson has recently undergone a change of heart. In any case, a kinder face of Australian materialism can be seen emerging in the late twentieth century, and this probably began with Mitchell. What seems clear from Mitchell’s work is that this trend began long before Anderson’s arrival in Australia, but was overlooked. It is certainly true that Mitchell, unlike Anderson and those materialists that followed him, took consciousness as a phenomenon to be explained in its own terms, not reduced, eliminated or ignored.

I previously outlined the Scottish traditions and Australian traditions which helped to shaped Mitchell’s work. In a later section, I shall suggest that Mitchell’s work has surprising application to current trends in cognitive science. His work thus deserves serious study by contemporary philosophers of mind. I shall briefly outline the central elements of Mitchell’s ideas here before continuing.

4. Mitchell’s Philosophy of Mind

Mitchell’s philosophical contributions have, as their focus, the nature of mind and experience. Particularly, he is interested in the growth of the mind; and, to a lesser extent, its ontology. He does make contributions to the philosophy of science and education; but these fall naturally out of his philosophy of mind. It remains to introduce in general outline what these contributions are and how they differ from present-day theories.

The key elements of Mitchell’s thought are easy enough to state in general terms: experience is the crucial element of our mental lives; or, to put it another way: “mental activity is central in experience” (Miller, 1929, p. 249). As I have suggested, Mitchell is a forerunner of what we now call the “New Mysterians”, who regard conscious subjective experience as a crucial, ineliminable feature of our lives. For Mitchell, it was no different. We are happy or depressed; we worry and at other times we are elated; we feel pains and pleasures. This kind of experience is fundamental to our mental and physical lives, and cannot to be reduced or eliminated.

However Mitchell is not merely interested in such conscious experiences. He recognizes that not all experience is conscious, but is nonetheless important to the growth of the mind. Experience, for Mitchell, covers everything from qualia to high-level intentional content at various levels. There is no principled epistemic divide to be drawn between these levels on Mitchell’s account. One learns about the mind primarily by studying experience directly as we live it (the “direct” approach); and secondarily, by studying the mind indirectly by means of the emerging sciences of the mind, for example, neuroscience (the “indirect” approach). Knowledge acquired by means of the direct approach aids in directing attention to relevant features of the indirect approach (thus, an adequate neuroscience might be directed to features of interest by means of contentful phenomenal experience).

The action of mind is always action on an occasion. The occasion is the moment and conditions under which an experience happens and the content that such conditions bring about. The occasion is a stimulus property (either mental, physical or environmental). Experience is what the mind, the “reacting structure”, does in reaction to its environment (a definition which is sufficiently vague to cover all aspects of content). Not everything about the mind is always involved on an occasion, only the activity which the occasion calls forth (so, for example, low-level modular-type processing, which do not seem to involve higher level concepts, is consistent with the concept of an occasion).

The organism aims to resolve occasions in order to achieve pragmatic and experiential ends. Thus, we focus our eyes to achieve a better view, etc. However this also occurs at higher levels. So, for example, our concepts are deployed in making sense of more complex experiences. Organisms start off by resolving low-level instinctual experiences, and then move to higher, more satisfactory levels of experience, though this is not so for all creatures on which there might be evolutionary and experiential constraints. As the idea of resolving experiences is a key to Mitchell’s account, this leads to an account which demands levels of experiential content.

There are three main levels of content according to Mitchell: sensory, perceptual and cognitive intelligence. These levels are represented in the following diagram.

The sensory level is roughly equivalent to instinct. Some organisms remain at this level and advance no higher. As Mitchell defines it, the course of instinctive action is: “the power of pursuing an infinite variety of courses, directed throughout by present sensation” (SGM, p. 194). Thus, we resolve our eyes to focus; cup or fix our ears; sniff with our noses. The next level is perceptual intelligence or “interest” which is equivalent to content which already comes with the power to anticipate further experiences (for example, we simply “see” a display of objects and know how to react; we don’t have to infer our course of action). This has a number of levels (feeling, practical and cognitive interests). Some organisms—some humans—even remain at these levels. The last level is cognitive intelligence which is influenced by rules, language and principles, and it helps differentiate the expert from the non-expert. Thus, in Hanson’s sense:

There is a ‘linguistic’ factor in seeing….Unless there were this linguistic element, nothing we ever observed could have relevance for our knowledge. We could not speak of significant observations: nothing seen would make sense, and microscopy would only be a kind of kaleidoscopy. For what is it for things to make sense other than for descriptions of them to be composed of meaningful sentences? (Hanson, 1975, p. 25).

Mitchell differs from Hanson in regarding the higher level conceptual intelligence as containing features of the lower levels as well. Thus, while at higher levels there is a “linguistic factor in seeing”, this is not all there is. Cutting across this tripartite division of forms of intelligence, which constitute broad bands or levels of content, is a distinction between the functions and forms of experience: feeling, interest and action. Each of these typify the kinds of content that organisms are interested in at particular moments.

On the metaphysics of mind, Mitchell has an interesting case to put. He believes the capacity to experience allows an inference to the notion of mind (Allen, 1984, p. 7). This is rather different from some current approaches which regard to the capacity to experience as a reason to deny the existence of mind (for, example, Dennett’s 1988, 1991, and Churchland’s views, 1979, 1984, 1986). By complete contrast, Mitchell thinks that the very structure of experience is evidence that mind exists (otherwise there would be no evident structure).

However, he does not argue for a faculty-based account of mind, nor the notion of “self” as an ontologically legitimate entity. This, to Mitchell, is an invalid inference. Rather, the working of the mind is a process due to various faculties, but they themselves are not processes and not an experience; rather, the relationship defines nominal entities which stand for what experiences are produced on an occasion. A faculty means, for Mitchell, merely the capacity to produce or the capacity to have, an experience of a certain kind (Miller, 1929, p. 249). Thus, Mitchell is no defender of a literal faculty-based psychology—unlike Fodor, who has recently tried to resuscitate the idea (Fodor, 1983). Rather, his account more closely resembles a defense of some kind of early dynamic process account, recently featured in the literature as “interactivist-constructionist” models (Christensen and Hooker, 1999; van Gelder, 1998, 1999; Port and van Gelder, 1995).

What of Mitchell’s position regarding the metaphysical relation of subject and object? Mitchell claims that in every experience there is differentiation of subject and object. But it does not follow that there is always an experience of difference between two subjects of experience (for example, we can be so absorbed in an experience we can forget the object) (Jackson, 1977). Rather, this differentiation is a product of the mind’s growth. Nor can we infer from one entity to the other qua self-subsistent entities (Miller, 1929, p. 249). For Mitchell, experience involves an implicit two-factor relation: experience helps in the analysis of the two factors in relation, and experience would be impossible without these factors. But, at the same time, experience begins as mere feeling or sensation without the division into subject and object; i.e., as an undifferentiated whole. In this sense, and only this sense, Mitchell follows Bradley. Experience does not, at least initially, consist of ourselves feeling something (for this involves higher-level thought—thought which is part of the later growth of the mind); rather, it is feeling as such, or—as Mitchell calls it—mere sensation; not somebody’s feeling or a feeling of something. Experience contains diversity, but a diversity which is prior to relations (Passmore, 1984, p. 62-3).

Why develop this apparently bizarre idea of mere experience as a non-relational whole? The answer to this is possibly the same as why others, such as Bradley, developed it. Mitchell was writing at a time of considerable Humean influence. Hume, of course, took the opposite assumption to that of Bradley and Mitchell. Instead of regarding experience as an undifferentiated whole, from which distinctions between subject and object arise, Hume took the opposite assumption, a skeptical attitude. He thought of experience as comprising a disconnected “bundle” of sensations on which we impose conventions of regularity and association. On Hume’s account, the “self,” and the subject of experience and action, disappears.

Mitchell, like his Scottish forebears, rejected this assumption as irrational and counterintuitive. Like Bradley, he attempted to ground an account of experience which more closely mirrored the unity, coherence and completeness which we really do find in our conscious lives. Unlike Bradley’s Hegelian musings about the Absolute, however, Mitchell was more interested in an account of the growth of the mind from its undifferentiated feeling to the stock of mental constructions and concepts which we know in experience. In other words, he aimed to construct “a psychology which is in turn an introduction to philosophy” (Passmore, 1984, p. 145).

Thus, Mitchell’s metaphysics is complex, descended from the Scottish common-sense views, British empiricism, and idealist metaphysics. He has idealist sympathies in so far as objects can only be understood or known as the subject of experiences. However, he does not confine objects as mental products in our heads, and he sees objects qua objects as part of a dynamical exchange between organisms and the world which makes experience possible (for a recent account that is similar, see Cantwell-Smith, 1996). In this latter sense, Mitchell can be understood as a die-hard realist. Though if “idealism” is interpreted generously enough to allow for the existence of independent external material objects—as perhaps it should be—he could also be considered an idealist of some conviction.

This point is often confused in the literature. E. M. Miller points out the confusion, and Mitchell’s attitude to it, very clearly indeed:

An idealism that denies external reality is no true idealism. The experience of the real is admitted. What the idealist wants to know is the nature and meaning of reality; and as to its nature and meaning there may be and is a great variety of opinions. No one in his senses doubts the existence of material objects. What brings about endless trouble is the confusion of material existence with the assertion of the existence of a material reality independent of mind. We cannot be conscious of something which is out of consciousness, and if we are conscious of anything, we know somewhat of it. This fact is a necessity of knowledge, and to assert its independence of the relations under which it is experienced as an object of consciousness is to assert nothing. We are not aware of anything to which consciousness does not testify. In a like manner we know mental facts as distinct from physical facts or processes. We may speak of mental processes as internal and of physical processes as external; but neither internality nor externality is applicable to mental processes as such. They are entirely different from the physical. They are not coordinate, to use Mitchell’s words….and “their correlation does not mean identity of nature” (Miller, 1930, p. 10).

The latter remark, that the mental is defined in terms that are neither internal nor external, captures the point that, for Mitchell, the exchange between subject and object is crucial to the nature of mind. For convenience, we refer to the “internal” and “external” (or subject and object), but the mental is not coordinate with either; and though they are often correlated, this does not amount to a relationship of identity. (Compare, the onset of spring and bees: they are coordinate facts, and there is a high correlation between them, but they are certainly not identical.)

5. Contemporary Cognitive Science

Now let us look briefly at the kind of environment current in contemporary philosophy of mind. I shall make a few points about how Mitchell differs from the contemporary discussions, and where he has sympathies. Obviously in an article of this length I can only gesture in the direction of Mitchell’s position on the issues.

1. Contemporary accounts of mind have no account of how and why minds grow. With few notable exceptions (Karmiloff-Smith, Piaget, Vygotsky) this is true. Most philosophers are more interested in ontological questions: What is consciousness?; What is a representational state?; What is a pain?, Are representations computational states?; and so on. They are less interested in the developmental question. Mitchell, by contrast, is concerned with the growth of the mind as the primary metaphysical issue.

2. Contemporary accounts assume that the computational processes of mind are central. The computational account, or—as it is known—the representational theory of mind (RTM) is dominant in the current literature. Computations performed over amodal, structured symbolic expressions tokened in a neural form is considered to be the main processing mechanism for cognitive states. There are a number of variations on how this is supposed to be achieved, but the metaphor of the mind as a computational system is widespread. Contemporary accounts which stress the processing of non-symbolic, modal, perceptual information is now making an appearance in the cognitive science literature, but this is a minority view (Barsalou, 1999). Mitchell is sympathetic with the modal-format account, which makes him rather contemporary.

3. Contemporary accounts subordinate the phenomenal features of mind to their representational/computational features. Many cognitive scientists are principally interested in how brains represent the world in thought. Phenomenological features of experience are an infuriating problem for computational accounts because they seem to resist explanation in the terms of the RTM. If qualia occur at all—and there is much dissension on the question—they are considered to be another form of representational capacity. Thus, the RTM allows for a variety of representational formats. However, it is not clear how neurally encoding—regardless of format—can capture the “what it is like” of phenomenal experience. Mitchell’s account attempts to outline a variety of representational formats employed by the organism at various stages of its cognitive growth.

4. Contemporary accounts assume the “indirect” (neurophysiological) approach to be the best, or only, approach. Contemporary accounts generally assume that the advancing neurosciences will eventually shed insight on questions of consciousness, representation and cognition. There are some who claim that there is an “explanatory gap” and that we are cognitively prevented from crossing it (McGinn, 1991; Levine, 1983). Mitchell agrees that the indirect approach is essential but only in conjunction with the direct approach. This is in line with others who, while they regard the direct approach as valuable, claim that it plays a subordinate role to first person experiential perspectives (Nagel, 1974; Jackson, 1990; Chalmers, 1996). This kind of position is now gaining currency again, long after Mitchell originally proposed it (Edelman, 1992; Flanagan, 1992, 1995; Overgaard, 2001; van Gulick, 1993; see Davies, 2003).

5. Contemporary accounts assume that an epistemology of content is subordinate to an ontology of mind. Contemporary accounts are less interested in epistemological concerns; when they are, it is usually expressed in terms of how minds represent the world in thought in computational terms. However, this already assumes an ontology of mind. Mitchell’s approach is to construct an epistemological account from which an ontology of mind is derived as an inference. The central issue is not what minds are—the key question is how we have the experiences we do. Since experience has structure there must be minds. From the epistemological agenda an “indirect” account of the nature of mind follows.

6. Why Mitchell has been Forgotten

The reasons for the lack of interest in Mitchell’s philosophical work are fourfold: first, Mitchell’s work is historically badly poised. As I have already mentioned, he dealt with themes and ideas at the cross-over point between the death of idealism and “common-sense” philosophy, and the rise of Australian materialism and realism. This virtually ensured that his work sat uncomfortably between scholarly periods, but belonged properly to neither.

Second, his style of writing was poor. Even taking into account the stylistic conventions of the time—and allowing for the difficulty of the philosophical concepts he was engaged with—his work is badly written, often divorced of clear central themes, lacking in detailed exegesis and often ponderous in delivery. (A professor of classics at Adelaide at the time “used to say that he could never understand Mitchell’s books until he had translated them into Latin”.) (Duncan and Leonard, 1973, p. 19; Grave, 1984, p. 22). True enough, obscurity of style is no barrier to greatness (e.g., Wittgenstein). But in Mitchell’s case there were other factors in addition to stylistic obscurity that conspired to defeat him. Moreover, this estimation of Mitchell’s writing was not an individual complaint, but, by and large, consensual: reviewers of Mitchell’s first book complained about the difficulty “in focussing to a definite view the central conceptions upon which the work as a whole rests” (Kemp-Smith, 1908, p. 333). It was also criticized for its “obscurity”, its “somewhat oracular style” (Acton, 1934, p. 245) and even its “undeniable dreariness”. One reviewer pointed out that, while reading it, one always has to “retrace one’s steps and grope for the context”. The same complained that, because of “no contour or difference in emphasis”, reading the book was like “swimming under water with never a chance to come up and look about” (Perry, 1908, p. 45). Norman Kemp-Smith, a philosopher later famous for his extremely clear exposition of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, even had the audacity to suggest that Mitchell’s work could have been “condensed to half its present size” without loss, and complained about his “obscurity” and “constant digression into….side issues” (Kemp-Smith, 1908, p. 332). Everybody, except Mitchell himself, found his work virtually impenetrable.

Third, Mitchell’s perspective on the issues of the day was unconventional and is hard to understand even with the hindsight of trends and developments in the late twentieth century. A number of his views are simply unfashionable: for instance, the emphasis taken in both his writing and his classes was that psychology “is the proper introduction to philosophy”; a view certainly not popular today notwithstanding recent interest in a return to “philosophical psychology” (see Gold and Stoljar, 1999).

Fourth, Mitchell made no allowances for the reader: his second book was premised on the reader having read and digested the first; however the first book assumes an acquaintance with the themes and concerns of nineteenth century thought not merely in philosophy, but also in developmental psychology, neuroscience, physics and biology. Thus, for the contemporary reader Mitchell’s writing is now almost beyond reach. His second book, universally regarded as harder to read than the first, presupposes a detailed knowledge of quantum mechanics and other areas of physics very fresh for the time. Not only this, but Mitchell makes no attempt to connect his ideas with the debates which were current at the time in the literature and “never ties his reflections to a specific philosophical controversy” (Passmore, 1962; 1963, p. 145). To make matters worse, Mitchell never provided indexes to his books, and gives no summaries, recapitulations of points, nor linguistic “signposts” to aid the unwitting reader. It is this kind of inconsiderate authorship which helps explain V. A. Edgeloe’s cryptic remark that Structure and Growth of the Mind was, “for more than a quarter of a century….a textbook over which university students, in Adelaide at least, sweated” (Edgeloe, 1966, p. 536).

There is no excuse for such obscurity these days, but in the colonies during the late nineteenth century, things were different. Another reason for Mitchell’s obscurity is the factor of academic isolation to which I have already alluded. J. A Passmore has highlighted this point in relation to his two works Structure and Growth of the Mind and The Place of Minds:

Both books are, very obviously, the products of a solitary thinker. When Mitchell went to South Australia, contacts between Adelaide and the eastern states were rare, voyages to Europe or America even rarer. Few Australian philosophers as much as met Mitchell, and his influence in Australia has not been extensive (Passmore, 1963, p. 145).

There were yet further reasons for the neglect of Mitchell’s work. At around the time Mitchell’s work was beginning to be discussed, a new philosophical star was on the rise. Wittgenstein had emerged on the scene and, along with the influence of Rylean behaviorism, this presented a potent philosophical cocktail. Subjective states and discussions about sui generis conscious states fell into philosophical abeyance. Under the influence of Wittgenstein and behaviorism, issues concerning mind and consciousness began to be seen as no longer topics for fruitful philosophical discussion, but rather avoided or smothered under linguistic analysis. This remained the case well into the latter half of the twentieth century.

7. References and Further Reading

Acton, H. B., (1934), “The Place of Minds in the World. Gifford Lectures at the University of Aberdeen 1924-26,” (Review), Mind, Vol. 43, No. 170, pp. 243-245.

Allen, H. J., (1984), Mitchell’s Concept of Human Freedom. Masters Dissertation: University of Adelaide.

Allen, H. J. (1995), An Exposition of Selected Aspects of the Philosophy of the Late Sir William Mitchell. Unpublished manuscript: University of Adelaide.

Anderson, J., Cullum, G., Lycos, K., (eds.) (1962), Studies in Empirical Philosophy. Sydney: Angus and Robertson.

Anderson, J., (1980), Education and Inquiry. (ed.) D. Z. Phillips. Oxford: Blackwell.

Anderson, J. (1982), Art and Reality: John Anderson on Literature and Aesthetics. Marrickville, NSW: Hale and Iremonger.

Baker, A.J., (1979), Anderson’s Social Philosophy. Hong Kong: Angus and Robertson Publishers.

Baker, A.J., (1986), Australian Realism: The Systematic Philosophy of John Anderson. U.K.: C.U.P.

Barsalou, L. W., (1999), “Perceptual Symbol Systems”, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22, pp. 577-660.

Blanshard, B., (1939), The Nature of Thought. London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd. (Two Volumes).

Boucher, D. (in press) “Sir William Mitchell” in Dictionary of Twentieth Century British Philosophers. Bristol, UK.: Thoemmes Press. http://www.thoemmes.com/dictionaries/20entries.htm

Cantwell-Smith, B., (1996), On the Origin of Objects. A Bradford Book. Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T. Press.

Chalmers, D., (1996), The Conscious Mind. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Christensen, W. D. and Hooker, C.A., (2000), “An Interactivist-Constructivist Approach to Intelligence: Self Directed Anticipative Learning”, Philosophical Psychology, 13, pp. 5-45.

Churchland, P. M., (1979), Scientific Realism and the Plasticity of Mind. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Churchland, P. M., (1984), Matter and Consciousness. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press

Churchland, P. M., (1986), “Some Reductive Strategies in Cognitive Neurobiology”, Mind, 95, no. 379, pp. 279-309.

Coombs, A., (1996), Sex and Anarchy: The Life and Death of the Sydney Push. Ringwood, Victoria: Viking.

Cussins, A., (1992), “Content, Embodiment and Objectivity: The Theory of Cognitive Trails”, Mind 101: pp. 651-688.

Davies, W. M., (1996), Experience and Content: Consequences of a Continuum Theory. Aldershot, UK: Avebury.

Davies, W. M. (1999) “Sir William Mitchell and the New Mysterianism“, Australasian Journal of Philosophy, Volume 77, No. 3, September 1999: pp. 253-257.

Davies, W. M. (2001) “Sir William Mitchell”, SA’s Greats: The Men and Women of the North Terrace Plaques. J. Healey (ed), Historical Society of South Australia Publication.

Davies, W. M. (2003) The Thought of Sir William Mitchell 1861-1962: A Mind’s Own Place. Studies in the History of Philosophy, Volume 73. Edwin Mellen Press: Lewiston, USA.

Dennett, D. C. (1988), “Quining Qualia”, Consciousness in Contemporary Science. A. Marcel and E. Bisiach, Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Dennett, D. C. (1991), Consciousness Explained. Boston: Little, Brown and Co.

Devitt, M., (1984), Realism and Truth, UK: Basil Blackwell.

Duncan, W. G. K., and Leonard, R. A., (1973), The University of Adelaide, 1874-1974. Rigby, The Griffin Press, Adelaide. See especially Chapter 7, “The Mitchell Era”.

“Economics at Adelaide” (2003), Lumen magazine, University of Adelaide: Adelaide. (URL: http://www.lumen.adelaide.edu.au/2003winter/page15/ [accessed 10/2/04]

Edelman, G., (1992), Bright Air, Brilliant Fire, NY: Basic Books.

Edgeloe, V. A., (1966), Australian Dictionary of Biography. Volume 10, 1891-1939, “Sir William Mitchell”, Melbourne University Press: Melbourne, pp. 535-537.

Edgeloe, V. A., (1993), Servants of Distinction: Leadership in a Young University 1874-1925. University of Adelaide Foundation: Educational Technology Unit.

Flanagan, O., (1992), Consciousness Reconsidered. Cambridge, Mass: MIT/Bradford.

Flanagan, O., (1995), The Science of the Mind. 2nd Ed., Cambridge, Mass: MIT/Bradford.

Fodor, J. A., (1983), Modularity of Mind: An Essay in Faculty Psychology. Cambridge, Mass: MIT/Bradford.

Franklin, J., (2000), Corrupting the Youth: A History of Philosophy in Australia. Paddington, Macleay Press.

Gold, I. and Stoljar, D., (1999), “A Neuron Doctrine in the Philosophy of Neuroscience”, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 22, pp. 809-869.

Grave, S., (1984), A History of Philosophy in Australia. Hong Kong: University of Queensland Press.

Hanson, N. R., (1975), Patterns of Discovery: An Enquiry into the Conceptual Foundations of Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Harvey, J. W., (1934), “The Place of Minds in the World: Gifford Lectures at the University of Aberdeen 1924-26,” (Review), Journal of the British Institute of Philosophical Studies, Vol. 8, No. 33, pp. 103-106.

Hoernlé, R. F. A., (1909), “Structure and Growth of the Mind” (Critical Notice) Mind, New Series, XVIII, pp. 255-264.

Honderich, T., (ed.) (1995), The Oxford Companion to Philosophy, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jackson, F., (1977), Perception: A Representative Theory. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Jackson, F., (1990), “Epiphenomenal Qualia”, Mind and Cognition: A Reader. William Lycan (ed) UK: Basil Blackwell.

Karmiloff-Smith, A., (1992), Beyond Modularity: A Developmental Perspective on Cognitive Science. Cambridge, Mass: MIT/Bradford.

Kemp-Smith, N., (1908), “Review of Structure and Growth of the Mind”, The Philosophical Review, Vol. XVII, No. 3, pp. 332-339.

Kennedy, B., (1995), A Passion to Oppose: John Anderson, Philosopher. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

Levine, J., (1983), “Materialism and Qualia: the Explanatory Gap”, Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 64: pp. 354-361.

Lubbock, J., Sir (1888), On the Senses, Instincts and Intelligence of Animals. London: Kegan Paul.

Mackie, J. L., (1962), “The Philosophy of John Anderson“, Australasian Journal of Philosophy, Volume, 40, No. 3, December, pp. 265-282.

Mackie, J. L., (1977), “Fifty Years of John Anderson“, Quadrant .77, July.

McGinn, C., (1983), The Subjective View: Secondary Qualities and Indexical Thoughts. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

McGinn, C., (1991) The Problem of Consciousness. Oxford, Blackwell.

McClelland, J., Rumelhart, D. E., et al, (1986), Parallel Distributed Processing: Explorations in the MicroStructure of Cognition. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

McClelland, J., (1999), “Cognitive Modelling, Connectionist”, in R. A. Wilson and F. C. Keil, The MIT Encyclopedia of the Cognitive Sciences.

McLeod, A. L., (1963), The Pattern of Australian Culture. Melbourne University Press: Melbourne, (especially J. A. Passmore’s contribution: “Philosophy”, pp. 131-169).

Marshall, P. D., (2001), “Transforming the World Into Experience: An Idealist Experiment”, “Journal of Consciousness Studies”, 8, No. 1, pp. 59-76.

Miller, E. M., (1929), “The Beginnings of Philosophy in Australia and the Work of Henry Laurie“, Part 1, Australasian Association of Psychology and Philosophy, Vol VII, No. 4, pp. 241-251.

Miller, E. M., (1930), “The Beginnings of Philosophy in Australia and the Work of Henry Laurie“, Part 2, Australasian Association of Psychology and Philosophy, Vol VIII, No. 1, pp. 1-22.

Mitchell, W and Ledingham, M., (1890-1977), Papers of Sir William Mitchell and Sir Mark Ledingham. Unpublished MS.

Mitchell, W., (1895), The Advertiser, 19/12/1895

Mitchell, W., (1895), “Reform in Education”. International Journal of Ethics. October.

Mitchell, W., (1898), “What is Poetry?: A Lecture given to the South Australian Teachers Union”. Southern Cross Print.

Mitchell, W., (1903), Lectures on Materialism. (Extension lectures—Syllabus of Three) Adelaide: Thomas and Co.

Mitchell, W., (1907), Structure and Growth of the Mind. London: Macmillan and Co., Ltd.

Mitchell, W., (1908), “Discussion: Structure and Growth of the Mind”, The Journal of Philosophy, Psychology and Scientific Methods, 5, pp. 316-321.

Mitchell, W., (1909), Lecture on the Rate of Interest. Adelaide: Vardon and Sons. Institute of Accountants in South Australia.

Mitchell, W., (1912), Christianity and the Industrial System. Issued by the Methodists Social Service League. Adelaide: Hussey and Gillingham Ltd.

Mitchell, W., (1917), Lecture on the Two Functions of the University and their Cost. Adelaide: Hassel and Son Press.

Mitchell, W., (1918), “The National Spirit”, The Advertiser, 19/12/1918.

Mitchell, W., “Mitchell Archives”. A Collection of Newspaper clippings, photographs, articles, letters, lectures and notebooks.

Mitchell, W., (1925), “The Place of the Mind”, Syllabus of the Gifford Lectures. First Series. UK: University of Aberdeen.

Mitchell, W., (1926), “The Power of the Mind”, Syllabus of the Gifford Lectures. Second Series. UK: University of Aberdeen.

Mitchell, W., (1927), Jubilee Celebrations 1876-1926. Adelaide (Preface).

Mitchell, W., (1929), Nature and Feeling, University of Queensland John Murtagh MacCrossan Lectures. Adelaide: Hassel and Son Press.

Mitchell, W., (1929), “How Far Nature is Intelligible”, University of Adelaide Public Lectures, July 30th and August 6th 1929. Lecture Advertisement: Adelaide: Hassel Press.

Mitchell, W., (1931), Letter on the University and Education to the Committee on Public Education. Adelaide: Hassel and Son Press.

Mitchell, W., (1933), The Place of Minds in the World. Gifford Lectures at the University of Aberdeen, 1924-1926. First Series. London: MacMillan and Co., Ltd.

Mitchell, W., (1934), “The Quality of Life”, Proceedings of the British Academy, XX. Annual British Academy Henrietta Herz Lecture. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mitchell, W., (1937), Universities and Life. Introductory Address. Australian and New Zealand Universities Conference. Adelaide: The Hassell Press.

Nagel, T., (1974), “What is it like to be a Bat?”, Philosophical Review, LXXXIII, pp. 435-451.

Nagel, T., (1979), Mortal Questions. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Nagel, T., (1986), The View from Nowhere. New York: Oxford University Press.

Overgaard, M., (2001), “The Role of Phenomenological Reports in Experiments on Consciousness”, Psycholoquy, 12, No. 029. [http://www.cogsci.soton.ac.uk/]

Passmore, J., (1962), “John Anderson and Twentieth Century Philosophy”, in J. Anderson, Studies in Empirical Philosophy.

Passmore, J., (1977), “Fifty Years of John Anderson“, Quadrant, 21. July.

Passmore, J., (1984), A Hundred Years of Philosophy. UK: Penguin, Chaucer Press.

Perry, R. B., (1908), “Structure and Growth of the Mind” (Review), Journal of Philosophy, Psychology and Scientific Method, 5 pp. 45-48.

Port, R. F., and van Gelder, T., (1995), Mind as Motion: Explorations in the Dynamics of Cognition. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Sellars, W., (1963), “Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind”, in Science, Perception and Reality. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Smart, J. J. C., (1962), “Sir William Mitchell K. C. M. G. (1861-1962)”, Australasian Journal of Philosophy, Volume, 40, No. 3, December, pp. 259-263.

Smart, J. J. C., (1989), “Australian Philosophers of the 1950s”, Quadrant, Volume, 33, No. 6, June: pp. 35-39.

Sprigge, T. L. S., (1983), A Vindication of Absolute Idealism. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Trahair, R. C. S., (1984), The Humanist Temper: The Life and Work of Elton Mayo, New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books.

van Gelder, T., (1998), “The Dynamical Hypothesis in Cognitive Science”, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 21 (5), pp. 615-627.

van Gelder, T., (1999), “Revisiting the Dynamical Hypothesis”, Preprint Series, University of Melbourne Philosophy Department.

van Gulick, R., (1993), “Understanding the Phenomenal Mind: Are we all just Armadillos?”, in Consciousness: Psychological and Philosophical Essays, M. Davies and G. W. Humphreys (eds), Oxford: Blackwells.

Author Information

W. Martin Davies

Email: [email protected]

The University of Melbourne

Australia