Vatum: A Growing Collection of Conlang Literature,

no. 1

Editor: Jack Bradley

MS Date: 06-29-2020

FL Date: 10-01-2020

FL Number: FL-00006D-00

Citation: Bradley, Jack, editor. 2020. «Vatum: A Growing

Collection of Conlang Literature, no. 1.”

FL-00006D-00, Fiat Lingua,

Copyright: © 2020 Jack Bradley, Chris Brown, Jeffrey

Brown, Anthony Harris, James Hopkins, Franc

Kravos. This work is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0

Unported License.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

Fiat Lingua is produced and maintained by the Language Creation Society (LCS). For more information

about the LCS, visit http://www.conlang.org/

ISBN 978-1-71679-571-8

Vatum

A Growing Collection of Conlang Literature

Summer, 2020

no. 1

Produced by lam ‘aj Se’vIr malja’

Edited by Jack Bradley

2

Contents

From the Editor

Jack Bradley

Swesware

Chris Brown

From the Valley of Life

to the Island of the Green

Scarab

James Hopkins

Our Solar System

Anthony Harris

Beltös Mythology

Jeffrey Brown

Niyolue’s Choice

Franc Kravos

Black Wolf, Red Robin

Hood and the Three Pigs

Chris Brown

3

4

6

8

18

52

72

83

4

From the Editor

Conlangers have made

some

incredibly

in-depth

languages with rich literature all their own. Within these pages is

a space where conlangers who regularly compose in their own

conlang(s) can present their writings as well as get inspired by the

work of others. It’s a place to share, to applaud, and to learn.

When I announced that I was looking for contributions for this

first edition of Vatum, there was no shortage of material.

Conlangers of all sorts volunteered their work and I thank every

one of this quarter’s five contributors with all of my heart for

entrusting me with their creations. Together, you have made

something incredibly special. You all blow me away with your

boundless talent (and patience!) My hope is that I’ll keep

receiving enough contributions to compile these showcases of

amazing literary work being done by conlangers everywhere

quarter after quarter into the foreseeable future. nItebHa’ maqonjaj!

-Jack Bradley

5

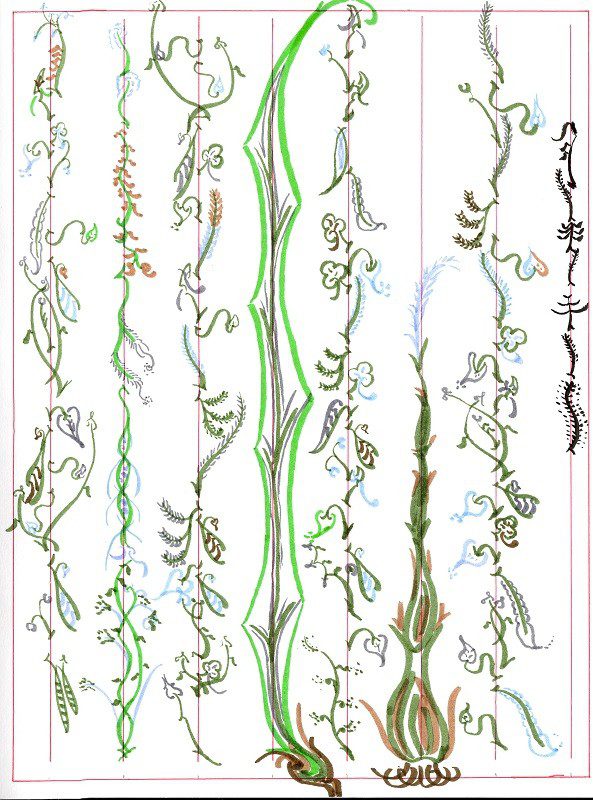

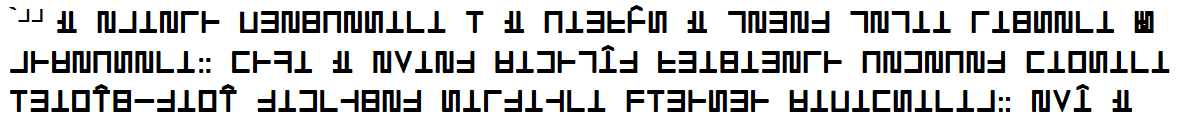

Swesware

Chris Brown (Dêne)

Denê folk of the world called Yeola love to compose

little bits of nature themed poetry. Here, Swesware is a winter

poem. They also delight in complicated pictorial scripts, of

which the Flower Script is an example.

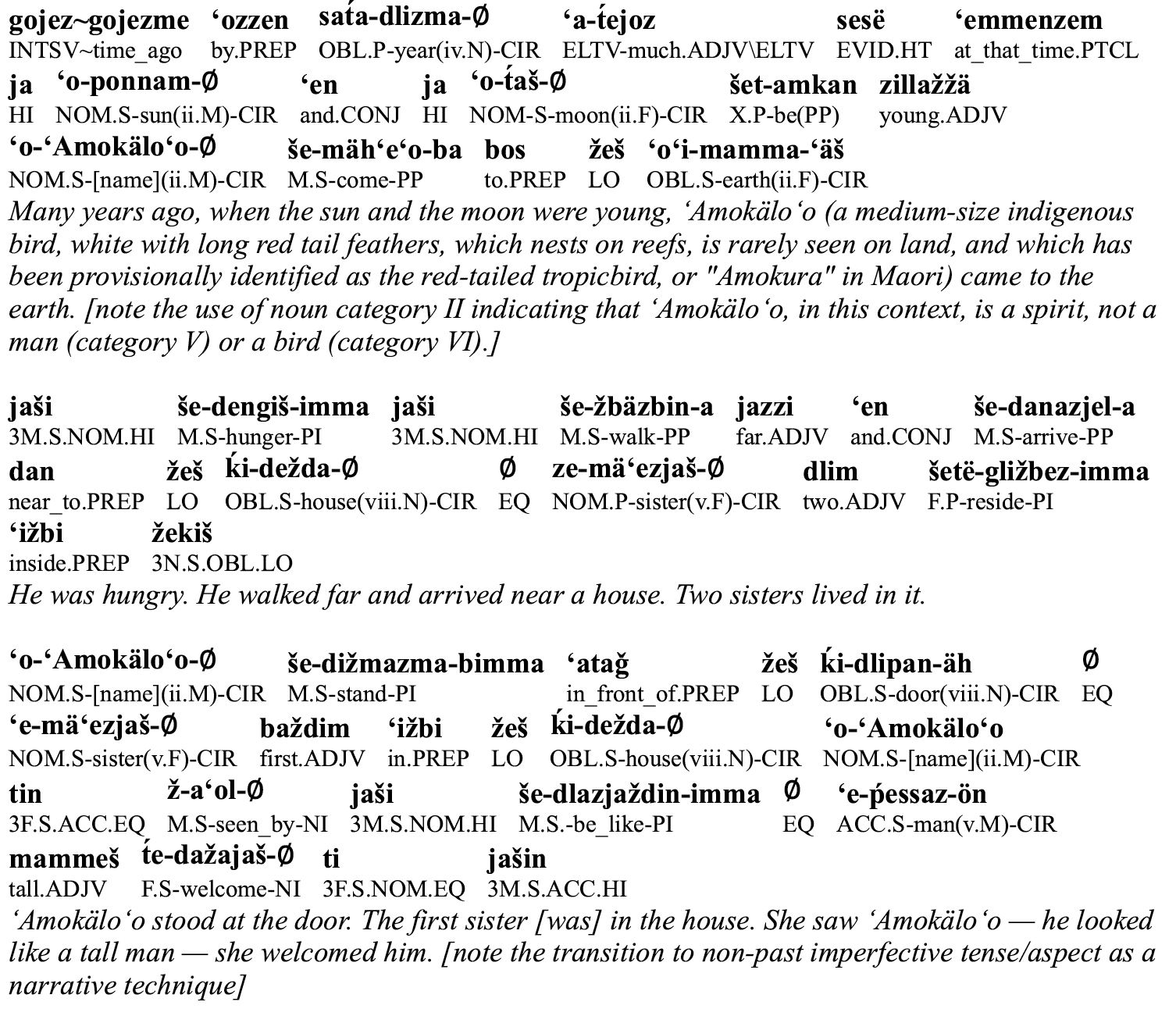

waylly na-moccanye surya pwe-herí sweswarocceng

sweswarenem Yeoles and en-derí harachanweste

le talghonye nimam and na-derí calamuravehers

esat endi sayano melle pwe-remanimonye wesenyas!

soft the cloak she snowed

in snow is Yeola shrouded

in fur-blanket is the girl sleeping

until her her Mother awakens!

6

7

From the Valley of Life to the Island of the Green Scarab

Gimlaay Zarideyna ta Karfeyese ta Shirit Shishaa

James Hopkins (Itlani)

The Itlani are great storytellers. The prazhendi, the

popular storytellers, will either generate new stories for pure

entertainment or re-tell old and well-known stories to inspire and

educate. Bellow is one such re-telling. It is a shorter and lighter

version of a part of the Prazhenú ta Vana, “Stories of the Origin”

well known and loved by all Itlani. This version was popularized

by An-Aylea. Many have grown up hearing her rendition.

[1] Iidova djatavit onyaru. Apuún kadimyava. Siarél

veykalyavel mogova arzenya raaréy. Vulbrugú kadimyaven.

Tendayunú ta visova Siarela klanaakriyaven. Dozhunú

panaifyaven, chadizhe byudemarizhe. Siarél mogese areylya

ra-vemyavel. Idatá, Rozh-Shpiláv

ta ebonova kimsiit

eylbrediese manukanavya veykalyavor.

8

[1] This I have heard. A disaster came. She-who-is-Blue decided not

to tolerate us anymore. Groundshakes came. Great waves wiped

across the surface of She-who-is- Blue. Great waters arose,

destroying much. She-who-is-Blue no longer wanted to be our nest.

Then, Rozh-Shpiláv decided to guide the people to a new home-

world.

[2] Franartantoilu, ta drunit bredí Drun seti ta versukan ta

dzevanzaa zumirit vey istonirit onyava. Ta fazhenit eyl ta

Itlantanarun onifyava. Itlán shtamishtaratyiva: Ushór Itlán.

Izaese ta Ravzhurit ebón, losh tamagit marfanit ebín, ta

Semeritanú vey ta Djiratanú, klanadepikyava. Ta tanto ta

Klanamisha kadimyava vey Rozh-Shpiláv

ta ebonovó

klanamanukanavyavor. Dini ta gimlaese ta zarideyna vutova

manukanavyavor, kiinizhe ruvivizhe dini ta Prazhenavá ta Vana

– iidova ishyari mog shey ta suuday. Shey iidova ta yastay mogit

ushelarun tilyari. Ruzay sheri ta perneyín ta ebontanarun

rachadizhe ruvyira.

[2] For a long time, the magenta planet Drun at the end of the travel-

9

portal had been watched and studied. It became the new nest of the

Itlani. It was renamed Itlán: Father Itlán. The Crane people along

with other friendly tribes, the Spruce Clan and the People of the

Whirlpools, moved there. The time of the Crossing came and Rozh-

Shpiláv guided the people across. He lead them to the valley of life,

as is told in the Stories of the Origin

– this we all know from our infancy. We learn this all from the

milk of our mothers. But little is said of the sufferings of the

people.

[3] TA GIMLA ZARIDEYNA shirit vey olutit onyava.

Varovfeynit onyava. Izá ta ebonú franarizhe anarakyaven,

loshdepikyaven, loshvadikyaven, loshetarashyaven. Ruzay,

ranti ta bakhna ta ebontanarun djamokrazhniya mabugyava

tadú khapanaifyaven izizá vey sheyzá vey layso ta chayantoit

ayzanenú ta Drunit Trela Rozh-Shpilava vutova degrimya

makayaven. Idatá ta Sanukír ta Drogosa mabugifyava.

[3] The Valley of Life was green and nourishing. It was mild and

gentle. For a long time the people were content there, they dwelt

together, they worked together, they grew together. But, when the

number of the people started to become too many disputes sprang

up here, there and everywhere and even the sweet smelling, sweet

tasting teachings of Rozh-Shpiláv’s Magenta Movement could not

10

extinguish them. It was then that the Age of Migration began.

[4] Ta min ebonú ta Gimlaay Zarideyna inubranya ra-

vemyaven ruzay ta tunkiú ta rozhreza djurova venyaven vey ta

heslaúd Rozh-Shpilava djurova amgalyava. Vey iíd ishyiva:

kulit akalalit bredí tashi ta min ebonavá ksevyava. Ta birafú ta

Drogosa gidanit vey franarit onyaren vey ras ta tantoova ras ta

shapova vutova iíz fidiriprazhenya lafiyari ruzay iküí chadit

anaravá ta perneyú ta ebontanarun akishtyaven.

[4] The three peoples did not want to leave The Valley of Life but

the needs of peace and tranquility required it and the wisdom of

Rozh-Shpiláv counselled it. And this is known: a whole explorable

planet lie before the three peoples. The adventures of the Migration

are great and long and we have neither the time nor the space to

tell out their stories but through many regions the sufferings of the

people were severe.

11

[5] TA GIMLA ZARIDEYNA anár

shasderevushit

mantabira onyara vey ta maka ta nasheyovó ekhdatya

shprunizhe safafivit onyava. Djufi-bolo, ta gimla stranit ta

rugesa, ta kutroa, ta tuhibroa, ta rafoa vey ta aktoa helistizhe

onyava vey ta kadjegú, ta madjuzú vey ta taraniú ta latsdiarun

palanaizhe ipulyaven. Ta ambáz, ta yast vey ta gisgís

palonyaven ruzay ta nasheyú afakyaven ra. Ta ebontanú

ardralit latseshkit birzaovó zhanya cheykopyaven. Ta muit

drogarú runese kiharya mabugyaven. Shatova run-pirenese

izaay proshyaven: Djurova Anso mishtaratyaven.

[5] THE VALLEY OF LIFE is a region of treeless highland and

the ability to cultivate crops was greatly limited. Nevertheless, the

valley was certainly rich in shrubs, sword- grass, red-grass,

mosses and lichens and the goats, the sheep and the cattle of the

farmers throve healthily. Meat, milk and cheese were plentiful

but the crops were not happy. The people had to find more

farmable land. The first pioneers began to move north. They

founded a city north-east of there: They called it Anso.

[6]ANSO dralit vey banadjinit shat onifyava. Shan gidanit

dozhlanan zamyiva. Ta ebontanú ta dozhlanova “Lusa Ansoa”

mishtaratyaven ruzay tsornitá idá kiinizhe “Pevlúsh Iyetea”

12

pilayira. Izá ta vul halanís arsefeshkit onyava vey izá ta banet

arurzit onyava. Anso etarashyava vey seti shey aulan arshmiit

onifyava.

[6] ANSO became a good and beautiful city. It was located along

a large body of water. The people called it “Anso Bay” but

nowadays it is known as the “Iyete Ocean”. The soil is more easily

planted there and the weather there is better. Anso grew and every

year became more prosperous.

[7] Lanlanizhe salú ta ebontanainen layso arrunese dzevyaven

vey ta Amarit Dzarovó klanamishyaven. Secha ta derevushú

pe iíd dzaravá etarashya ra-makayaren, ta amarró izá naryara.

Idakín ta dzarú amarit beylatsyaren. Iíd pientaizhe banadjinit

mashrá ta mosit Talorrovinavá onyara. Ta ebontanú djamó ta

dzaravá, dini naese drogyaven vey djurova “Na Mavivvula”

mishtaratyaven. Chadit drogarsalú

izá franar-anarakizhe

depikyaven. Iíd na dralit resh ta latsamín vey ta fahunosey ta

uridamarun onyava. Karizhe, ta yagusit drogarsalú gidanit

djurova

oglumese

“Djumdjeyelún”

maldjayaven.

13

mishtaratyaven vey

mishtaratyira.

tsorni-sáy “Djumdjeyelún Kesrea”

[7] Eventually groups of people travelled even further north and

crossed the Yellow Mountains. Although trees could not grow on the

mountains, the yellow-grass was dominant there. That is why the

mountains appear yellow. This is particularly beautiful during the

wondrous Pilgrimages of Talór (sunsets). The people journeyed

beyond the mountains, into the steppe and called it the “Mavivvúl

Steppe”. Many migratory groups settled there contentedly. This

grassland was good for the livestock and for hunting game. Finally,

various travelers reached a great fjord. They called it, “Narrow-

Deep” and now it is called the Great Narrow-Deep Fjord of Kesre.

[8] Franarit aulú ta zaradit ruzay zarideyneynit drogosaris

djamoyaven vey ta shprunudova ta ebontanarun chad-

lokoviilisa virmukaryiva. Ruzay Uramún-Tamú vutese ta

azova chokha dafarazhit onyavad: ta karfeyova ta shirit

shishaarun maldjaavit onyaven: mu ta oybanadjinit karfeyú

ta drunit bredia Itlán.

[8] Long years of difficult but life-filled migration passed and the

strength of the people was greatly tested by this ordeal. But the One-

Great-Friend, Uramún-Tamú, the Creator gave to them the jewel of

a reward: they had reached the isle of the green scarab: one of the

14

most beautiful islands of the magenta planet Itlán.

[9] TA KARFÉY TA SHIRIT SHISHAA dini ta zornastan ta

kubeyta onyara vey stranit ta notsia, ta braza, ta semeria, ta bulurza,

ta pilua, ta urua, ta sapruna vey ta lutana onyara. Dazhini djurit

amavá roeynadú, ta tsirstragú, ta doladamú, ta yovogú, ta

tuhibtsulaú vey ta koealír zhanyiren. Djurit oznatú djemarit ta

fardova, ta kevdoa vey ta istania onyaren vey dini djurit

derevushsalavá ta dakiuntasú, ta djoluntasú vey ta vorinú otrinizhe

kunyaren.

[9] THE ISLAND OF THE GREEN SCARAB is in the taiga

zone and is rich in pine, fir, spruce, birch, larch, alder, willow

and poplar trees. Among its animals are found grass- snakes,

fire-lizards, frogs, toads, red-wolves and white eagles. Its

rivers are full of salmon, trout, and seal and in its forests

brown-bear, black-bear and wolves roam free.

15

[10] Ruzay ta oykedit vey oyaleybit am ta karfeya ta shirit shishá-sá

onyara. Talvorit natunizhe shirit gurdzu – losh drunit brietín pe djurit

liravá vey narvamarit shumesha onyara. Mashrá ta urit harkazavá ta

Rumelosa ta derevushsalovó iküitaleayaren. Ta karfeyese djurit

mishtaratova dafaravit onyaren – vey daeshkizhe ta “Vuoti ta Shirit

Shishaarun” fidiri ta Fereshay Talór- Shirela dralpilaivit onyara vey iíz

djurova ra-prazhenyazhu shta. Vey ta anú ta Itlanit yoteyna ta aniena

ta shirit shishaa kadimyaren.

[10] But the most amazing and most dazzling animal is the green

scarab itself. It is a bioluminescent mostly green beetle – with

magenta spots on its wings and a bright yellow head. During the

short nights of the Leafing (Summer) they illuminate the forests.

They have given its name to the island – and of course the “Miracle

of the Green Scarabs” from the Book of Jewels is well known and

I will not re-tell it here again. And from the colors of the green

Scarab come the colors of the Itlani flag.

[11] Vey idaizhe brinkiyava u ta karféy ta Shirit Shishaa zhanyiva

vey depikyiva. Secha ta izait paleshát franarizhe kilikit samyava

Uramún-Tamú talvonit yazhtaova djureyre pabasyavad. Izá ta

Talruvarór Talór-Shirél kuteyryavor vey ayzanyavor. Izá ob ta

shuvekarun diniensiyiva. Izá natunshatún Pelesona vey Forokhena

16

kumenteryiva. Iidú ta prazhenú ta narena onyaren. Eshkizhe ranti

ta tanto vey ta muzhet dzavanyazhen iidovó ukhese ruvyazhu.

Shtashún!

[11] And so it happened that Green Scarab Island was found and

populated. Although the settlement there remained small for a long

time the Creator planned a glorious future for it. The Light-Speaker

Talór-Shirél would visit and teach there. An order of monks and

nuns would take root there. There the capital city of an Empire and

a Commonality would be established. These are the stories of

history. Perhaps when the time and interest prevail I will tell you

these. Until we see each other again!

17

Our Solar System

Ólves-Óñenyár

ólves-óñenyár

Tony Harris (Alurhsa)

The following is translated from a passage in an Alurhsa

children’s reader, intended to help children between the ages of 7

and 8 ½ Alurhsa years old learn about the planets of their solar

system. The language is suitable for young readers, but the

information is helpful for Terrans seeking to know more about this

fascinating civilization.

ólves-lúvá sóCô lòndrá. Lôñ gázá@e áySá

hìyán ìJäyá pel texná Còláznónyá ólves-

ánóñen Dá Zë yásmë vlóRyë óñen ólves-

óñenyárá. lòndrá ácëlô Sevánsán enegván Dá

lúvánán Zë þelnónÿ Dá Zë háZörónÿ. ólvë

áluRen órLályá Z’enegván Jú pólef ánegvâ

ólves-enesne@ëván, Dá Zë lúvánán pólef

Srëtâ ðiqenón, pólef Gelâ, Dá pólef áhìlâ

ólves-ánsígvâyón.

Ólves-lúvá sódlô Lòndrá. Lhôñ gázárre áyshá hìyán ìtsäyá pel

texná dlòláznónyá ólves-ánóñen ddá zhë yásmë vlórhyë óñen

ólves-óñenyárá. Lòndrá ácëlô shevánsán enegván ddá lúvánán

zhë thelnónÿ ddá zhë házhörónÿ. Ólvë álurhen órlhályá

zh’enegván tsú pólef ánegvâ ólves-enesnerrëván, ddá zhë

lúvánán pólef shrëtâ diqenón, pólef ghelâ, ddá pólef áhìlâ ólves-

ánsígvâyón.

18

Our sun is named Londra. It is a huge silver ball of fire

around which circle our homeworld and the other nine planets

of our solar system. Londra provides lifegiving energy and light

to the plants and animals. We Alurh also use the energy to

power our civilization, and the light to grow crops, to see, and

to heat our homes.

ólves-levíSá ánóñen Lôñ xrevná lòndráyá,

he eçe Lôñ Bìlá áváme ól delselká

nedelsáks dúvlen. ens úmáZëxná lòndrá

sáyô Tòsvì zánye hìyán çávin Lôñ zá@evá ól

áluRná zó denelsárenóxná.

Ólves-levíshá ánóñen lhôñ xrevná Lòndráyá, he eçe lhôñ bhìlá

áváme ól delselká nedelsáks dúvlen. Ens úmázhëxná Lòndrá

sáyô ttòsvì zánye hìyán çávin lhôñ zárrevá ól Álurhná zó

denelsárenóxná.

Our beautiful homeworld is the nearest to Londra, but even so it is over

one hundred and seventy five dúvlen away. Because of this Lòndrá

looks like just a small ball, although it is thousands of times larger than

Alurhna.

ólves-ánóñen sáyô óráñe þ ensá Zë skánáç.

Z’ásqám áluRnáyá zlúdelsá súçáme telámé

Z’álskenáxná, ávnáme álsken Zë kólexá. Zë

kólex sáyô ávnáme lúnye Dá Zë kámír sáyónyá

sín Dá sóyä Dá nává, póv delzyû Belkáren áv

áqáláren áv zólexár áv veskánþá. çávin

sáyónyá gázá@e ólves-íþlánó Dá ólves-

ávrídó, ñeyë dyár ávô Gelévrá Zë skánáç.

Ólves-ánóñen sáyô óráñethensá zhë skánáç.

Zh’ásqám

Álurhnáyá zlúdelsá súçáme telámé zh’álskenáxná, ávnáme

19

álsken zhë kólexá. Zhë kólex sáyô ávnáme lúnye ddá zhë kámír

sáyónyá sín ddá sóyä ddá nává, póv delzyû bhelkáren áv áqáláren

áv zólexár áv veskánthá. Çávin sáyónyá gázárre ólves-íthlánó

ddá ólves-ávrídó, ñeyë dyár ávô ghelévrá zhë skánáç.

Our homeworld looks multi-colored from space. The surface of

Alurhna is 80% covered with water, mostly ocean water. The ocean

looks mostly blue, and the land looks red and green and brown,

depending on whether it is forest or fields or mountains or desert.

Although our cities and buildings look huge, none of them are visible

from space.

áluRná pelvrïtóyù, ten elevályá Còrâ, Dá

hólef Zë ser myává @ónyá eSnô lòndrán mele

Lôñ Zë blé, Dá hólef GìSnô lòndráç mele Lôñ

Zë ñevan. kálÿ áluRná Lôñ gázá@e hìyán, Zë

Geles te vëZô blén Tólevóyô, nálÿ hólef

ánZyáð ráme Lôñ mátës tye káláSénáyá máçisì,

mele Lôñ líñva tye senekáyá tye lyívá

kániltómá, Dá Lôñ vetës tye eskálváyá

veçisì. dwi blé vùn dwi ñevaná remónyá

Bóran, ten ányátályá delsáme ás tenÿ

sóCónyá Bór.

Álurhná pelvrïtóyù, ten elevályá dlòrâ, ddá hólef zhë ser myává

rrónyá eshnô Lòndrán mele lhôñ zhë blé, ddá hólef ghìshnô

Lòndráç mele lhôñ zhë ñevan. Kálÿ Álurhná lhôñ gázárre hìyán,

zhë gheles te vëzhô blén ttólevóyô, nálÿ hólef ánzhyádhráme

lhôñ mátës tye Káláshénáyá máçisì, mele lhôñ líñva tye Senekáyá

tye lyívá Kániltómá, ddá lhôñ vetës tye Eskálváyá veçisì. Dwi

blé vùn dwi ñevaná remónyá bhóran, ten ányátályá delsáme ás

tenÿ sódlónyá bhór.

20

Alurhna turns around and around, which is called rotating. When the

land where we are faces Londra it is daytime, and when it faces away

from Londra it is night. Because Alurhna is a huge ball, the part where

it is day changes, so when, for example, it is dawn in Kalashena in the

East, it is midnight in Seneka in the center of Kaniltom, and it is sunset

in Eskalva in the West. One daytime and one night make up a day,

which we divide into ten parts we call hours.

Zë yásmë údrës ten kelyô ólves-óñen Lôñ

Còznâ lòndrán. áluRná ontô zá@en Còleskván

pel lòndráyá, Dá Zë WòXrë te neLé pólef

kályâ úmáZën ontenán sóCô síznâ. áluRná

Còrô sedelselká-zlúdelsáxne gó dwi síznâ.

elñ ráyáyëv Zë cìrán gó ñevaná Zla móyëv íSâ

ñólyën Gelesán Zë síznâyá vëZáyëv. gó sílátá

síznâxná, LáskyeJáç ás Lányóenánÿ, Lôñ

Gelévrá Zë CòráZge. úmáZë sílátá síznâ, ó

znâ, sóCô LáskyeJvá. gó Zë yálexná sílátá

síznâxná, Lányóenáç ás LáskyeJánÿ, sùlme

Geyëv Zë léLán nvelán skánán, ne¿ï Zë yásmën

lòndráyón, Cáskúyádán, Dá lúskren. úmáZë

znâ sóCô LányeXvë.

Zhë yásmë údrës ten kelyô ólves-óñen lhôñ dlòznâ Lòndrán.

Álurhná ontô zárren dlòleskván pel Lòndráyá, ddá zhë shthòszrë

te nelhé pólef kályâ úmázhën ontenán sódlô síznâ. Álurhná

dlòrô sedelselká-zlúdelsáxne gó dwi síznâ. Elñ ráyáyëv zhë cìrán

gó ñevaná zhla móyëv íshâ ñólyën ghelesán zhë síznâyá

vëzháyëv. Gó sílátá síznâxná, lháskyetsáç ás lhányóenánÿ, lhôñ

ghelévrá zhë Dlòrázhge. Úmázhë sílátá síznâ, ó znâ, sódlô

lháskyetsvá. Gó zhë yálexná sílátá síznâxná, lhányóenáç ás

lháskyetsánÿ, sùlme gheyëv zhë lélhán nvelán skánán, ne¿ï zhë

21

yásmën lòndráyón, Dláskúyádán, ddá Lúskren. Úmázhë znâ

sódlô lhányeszvë.

The other motion that our planet does is to revolve around Londra.

Alurhna follows a big circle around Londra and the time it takes to

complete this is called a year. Alurhna rotates two hundred and eighty

times in one year. If you look at the sky at night you can tell what part

of the year you are in. For half the year, from Lhaskyets to Lhanyoen,

the Great Wheel is visible. This half year, or season, is called

Lhaskyetsva. For the other half of the year, from Lhányóen to

Lhaskyets, you will only see empty black space other than the other

Children of Londra, the Milky Way, and Triangulum. This season is

called Lhanyeszvë.

pólef Wálâ áluRnáç Zë yásmënÿ lòndráyónÿ

deyëS Zeznâ skánváRáxná. he neLené lesmel

qóráS póv hólef vánRáyëv. Wóváxne Lôñ

móvrá úmáZë? vëZô kálÿ kólf áluRná Còznô

lòndrán, Jú Còznónyá Zë yásmë lòndráyë. Dá

ñe Còznónyá gó sirá qóráSáxná. kálÿ Tòsnë

yásmë lòndráyë ávô Bìlává lòndráç ól

áluRná eref dyárs-Còznen, ó dyárs-síznâ,

ávô qórsává, nálÿ ánZyáðráme áluRná móvrô

vëZâ LáskyeJván gó Z’óñen ten bleSváyëv

ándzálâ vëZô enþá LányeXván Dá Lôñ eref

wóqe lòndráyá nálÿ Zë Wálës Lôñ qórsá. he

yáneres ens Zë Còznenán áluRnáyá delzyû

lórqává úsme óñen Lôñ siqe lòndráyá Dá Lôñ

lórqává Zë Wálës.

Pólef shthálâ Álurhnáç zhë yásmënÿ lòndráyónÿ deyësh zheznâ

skánvárháxná. He nelhené lesmel qórásh póv hólef vánrháyëv.

Shthóváxne lhôñ móvrá úmázhë? Vëzhô kálÿ kólf Álurhná

dlòznô Lòndrán, tsú dlòznónyá zhë yásmë lòndráyë. Ddá ñe

22

dlòznónyá gó sirá qórásháxná. Kálÿ ttòsnë yásmë lòndráyë ávô

bhìlává Lòndráç ól Álurhná eref dyárs-dlòznen, ó dyárs-síznâ,

ávô qórsává, nálÿ ánzhyádhráme Álurhná móvrô vëzhâ

lháskyetsván gó zh’óñen ten bleshváyëv ándzálâ vëzhô enthá

lhányeszván ddá lhôñ eref wóqe Lòndráyá nálÿ zhë shthálës lhôñ

qórsá. He yáneres ens zhë dlòznenán Álurhnáyá delzyû lórqává

úsme óñen lhôñ siqe Lòndráyá ddá lhôñ lórqává zhë shthálës.

In order to travel from Alurhna to the other Children of Londra you

must take a shuttle. But it will take a different amount of time

depending on when you leave. How is this possible? It happens because

just like Alurhna revolves around Londra, the other Children of Londra

also revolve around it. And they do not revolve in the same amount of

time. Because every Child of Londra is farther from Londra than

Alurhna, there revolutions, or years, are longer, so for example Alurhna

could be in Lhaskyetsva while the planet you want to visit might be in

Lhanyeszvë and therefore on the other side of Londra so the trip is long.

But another time because Alurhna’s revolution is shorter that same

planet might be on this side of Londra so the trip is shorter.

Zë sílává óñen Gel lòndráç Lôñ árïkan.

árïkan Lôñ nílísá zányevá ól áluRná Dá

Còznô lòndrán sùlme eldelsáL súçá

neLényá Lúdelselká zlúr

Bìláváme.

áluRnásá Bóran pólef TòCòznô lòndrán, he

Zë Bóran árïkaná Lôñ lórqává ól Z’áluRnáyá,

kálÿ Còrô nílísá qálsáváme. Zë Bóran

árikaná góyô zlúr Bóráxná vùn nestá peSárá.

nálÿ Zë síznân árïkaná Lôñ Lúdelselká

ksòndelsáL árïkansá Bóran.

Zhë sílává óñen ghel Lòndráç lhôñ Árïkan. Árïkan lhôñ nílísá

zányevá ól Álurhná ddá dlòznô Lòndrán sùlme eldelsálh súçá

23

bhìláváme. Nelhényá lhúdelselká zlúr Álurhnásá bhóran pólef

ttòdlòznô Lòndrán, he zhë bhóran Árïkaná lhôñ lórqává ól

zh’Álurhnáyá, kálÿ dlòrô nílísá qálsáváme. Zhë bhóran Árikaná

góyô zlúr bhóráxná vùn nestá peshárá. Nálÿ zhë síznân Árïkaná

lhôñ lhúdelselká ksòndelsálh Árïkansá bhóran.

The second planet from Londra is Arikan. Arikan is a little smaller

than Alurhna and orbits Londra only 43% further away. It takes three

hundred and eight Alurhnan days to complete a trip around Londra,

but the day on Arikan is shorter than the Alurhnan day, because it

rotates a little faster. The day on Arikan lasts eight hours and seven

tenths. So the year on Arikan is three hundred fifty three Arikan days.

yásmë lesmelës tye árïkaná Lôñ el Vájáyëv

éve ól tye áluRnáyá. kálÿ árïkan Lôñ zányevá

ól áluRná, Dá kálÿ Lôñ eSkï lesmelán

remenón, Z’óñentránsës árïkaná Lôñ leftává.

elñ Vájáyëv nestá kevi tye áluRnáyá, Vájáyëv

Tòsvì zílyev tye árïkaná.

Yásmë lesmelës tye Árïkaná lhôñ el llájáyëv éve ól tye

Álurhnáyá. Kálÿ Árïkan lhôñ zányevá ól Álurhná, ddá kálÿ lhôñ

eshkï lesmelán remenón, zh’óñentránsës Árïkaná lhôñ leftává.

Elñ llájáyëv nestá kevi tye Álurhnáyá, llájáyëv ttòsvì zílyev tye

Árïkaná.

Another difference on Arikan is that you weigh less than on Alurhna.

Because Arikan is smaller than Alurhna, and because it is made of

different materials, the gravity on Arikan is weaker. If you weigh seven

kevi on Alurhna, you weigh only six on Arikan.

tye árïkaná vìgô rehelSá Záfáren kólf xólyá

tye áluRnáyá he Z’árïkansá Lôñ clá fósá Dá

24

leftá. áluRen ñe móvrô Sevâ vá qórsáme veñ

Záfìráç ne¿á tye Zë veCávnáyá Welyáóná. vìgô

zánye elírá þeln te Srëtónyá tye Zë

hólexárá Dá Zë yásmá veCánþáyáóná, myává

léyô Zë ñórá álsken árïkaná. Zë þeln ávô

ávnáme lúnye ó vlónë Bésáxne Zë Bìyä ó Zë

sóyä ó Zë gaín ó Zë sín te Gelényá tye

áluRnáyá. árïkan Jú tôñ crêvá ól áluRná Dá

Zë bóyen te gevónyá vá deSónyá hìnâ

hìlánsáván hìnárán.

Tye Árïkaná vìgô rehelshá zháfáren kólf xólyá tye Álurhnáyá he

zh’Árïkansá lhôñ clá fósá ddá leftá. Álurhen ñe móvrô shevâ vá

qórsáme veñ zháfìráç ne¿á tye zhë vedlávnáyá shthelyáóná. Vìgô

zánye elírá theln te shrëtónyá tye zhë hólexárá ddá zhë yásmá

vedlántháyáóná, myává léyô zhë ñórá álsken Árïkaná. Zhë theln

ávô ávnáme lúnye ó vlónë bhésáxne zhë bhìyä ó zhë sóyä ó zhë

gaín ó zhë sín te ghelényá tye Álurhnáyá. Árïkan tsú tôñ crêvá

ól Álurhná ddá zhë bóyen te gevónyá vá deshónyá hìnâ

hìlánsáván hìnárán.

On Arikan there is a breathable atmosphere like we have on Alurhna

but the Arikan air is very thin and weak. Alurh cannot live there for

long without air tanks except in the low places. There are small native

plants that grow in the valleys and the other low areas, where the little

water on Arikan is found. The plants are mostly blue or purple instead

of the orange, light or dark green or red that are seen on Alurhna.

Arikan is also colder than Alurhna and the people who live there must

wear warmer clothing.

vìgô sedelsán Bìgeven tye árïkaná. Zë

zá@evá Bìgeven Lôñ áwnáliJ, te Lôñ Zë

tye

prëyevná

ólves-¿ámsá

Bìgeven

25

vìgô ksòndóvírá bóyen te

yáSóñenyá.

gevónyá áwnáliJán, Dá ksòndóvenyá tye

árïkaná. ávná Z’íþlánáóná Lôñ kaskámì kálÿ

ñe Lôñ móvrá el kórá bóyen geválnâ berkámì

tye árïkaná.

Vìgô sedelsán bhìgeven tye Árïkaná. Zhë zárrevá bhìgeven lhôñ

Áwnálits, te lhôñ zhë prëyevná bhìgeven ólves-¿ámsá tye

yáshóñenyá. Vìgô ksòndóvírá bóyen te gevónyá Áwnálitsán, ddá

ksòndóvenyá tye Árïkaná. Ávná zh’íthlánáóná lhôñ kaskámì

kálÿ ñe lhôñ móvrá el kórá bóyen geválnâ berkámì tye Árïkaná.

There are twenty-seven settlements on Arikan. The biggest settlement

is Awnalits, which is the first offworld settlement of our people. There

are five hundred thousand people who live in Awnalits, and five million

on Arikan. The cities are mostly underground because it is not possible

for so many people to live above ground on Arikan.

árïkan xô sílá kálzámán, lóran Dá Zíran. ñe

vìgô Záfáren ñó álsken tye dyárá, nálÿ ñeyë

gelv gevô vá. ñeyë gelv ne¿á ksònye zánye

kámìZánsá Bìgeven tye lóraná Dá ává Lúvá

tye Zíraná. órá speZáne Jelem qíëdónyá

úmáZëç sílá kálzámáç. Z’ásqám ávô CeSá Dá Zë

cìr ávô Tórsá nvel kólf Zë skán. Zë Bìgeven

ávô

Zë

kámìZónevár Dá yáSë bóyenár te neLényá

pólef fárónâ Zë kámìZáqárán gevónyá Zë

Bìgevenón.

kaskámì Dá

Tòsneme

sùlme

Árïkan xô sílá kálzámán, Lóran ddá Zhíran. Ñe vìgô zháfáren

ñó álsken tye dyárá, nálÿ ñeyë gelv gevô vá. Ñeyë gelv ne¿á

ksònye zánye kámìzhánsá bhìgeven tye Lóraná ddá ává lhúvá tye

26

Zhíraná. Órá spezháne tselem qíëdónyá úmázhëç sílá kálzámáç.

Zh’ásqám ávô dleshá ddá zhë cìr ávô ttórsá nvel kólf zhë skán.

Zhë bhìgeven ávô

sùlme zhë

kámìzhónevár ddá yáshë bóyenár te nelhényá pólef fárónâ zhë

kámìzháqárán gevónyá zhë bhìgevenón.

ttòsneme kaskámì ddá

Arikan has two moons, Loran and Zhiran. There is no atmosphere or

water on them, so there are no living things there. No living things

except for five small mining settlements on Loran and another three on

Zhiran. Many important metals come from these two moons. The

surfaces are rocky and the sky is always as black as space. The

settlements are entirely underground and only the miners and other

people who are needed to make the mining equipment work live in the

settlements.

Zë Lúvásá lòndráyë Lôñ kìsál. kìsál Lôñ

sùlme Lúvá elkátá zá@esi ól áluRná, Dá Còrô

clá lesqáváme. dwi Bóran kìsálá góyô

eldelsás Bóran áluRnáyá. Dá Zë síznâ kìsálá

góyô ává ól vlóRyë áluRnásáxná síznâxná kálÿ

Lôñ kìn Lúváxne Bìlává lòndráç ól áluRná.

ñe xô kálzámán. sóCô kìsál kálÿ vìgô órá

kámáZen máceSòná Dá preleksáZïná ber

Z’ásqámá te sáyónónyá Z’óñenyán kìS. úmáZë

kìS ásqám yánáSô órá lúvensán Dá dzónô

kìsálán Zë lúvósávná Zë cìrá ne¿ï lòndrán

Dá Zë CòráZge.

Zhë lhúvásá lòndráyë lhôñ Kìsál. Kìsál lhôñ sùlme lhúvá elkátá

zárresi ól Álurhná, ddá dlòrô clá lesqáváme. Dwi bhóran Kìsálá

góyô eldelsás bhóran Álurhnáyá. Ddá zhë síznâ Kìsálá góyô ává

ól vlórhyë Álurhnásáxná síznâxná kálÿ lhôñ kìn lhúváxne

bhìlává Lòndráç ól Álurhná. Ñe xô kálzámán. Sódlô Kìsál kálÿ

27

vìgô órá kámázhen máceshòná ddá preleksázhïná ber zh’ásqámá

te sáyónónyá zh’óñenyán kìsh. Úmázhë kìsh ásqám yánáshô órá

lúvensán ddá dzónô Kìsálán zhë lúvósávná zhë cìrá ne¿ï Lòndrán

ddá zhë Dlòrázhge.

The third Child of Londra is Kisal. Kisal is also only three quarters as

big as Alurhna, and rotates very slowly. One day on Kisal lasts forty

two Alurhnan days. And the year on Kisal lasts over nine Alurhnan

years because it is almost three times as far from Londra as Alurhna is.

It has no moon. It is called Kisal because there are many deposits of

milkstone and mineral salts on the surface which make the planet

appear white. This white surface reflects a lot of sunlight and makes

Kisal the brightest object in the sky except for Londra and the Great

Wheel.

Zë Záfáren kìsálá Lôñ clá fósá, Dá ðón

remónyá Záfen ten ñe ávrályá rehâ kólf Zë

sóyZem Dá Zë tvixáZem. Z’óñentránsës kìsálá

Lôñ sùlme zídelsás súçá Z’óñentránsës

áluRnáyá, nálÿ elñ Vájáyëv nestá kevi tye

áluRnáyá Zla Vájáyëv Tòsvì elká vùn Lúvátáyá

tye kìsálá. Jú hìvô zá@eme crê ens delzyû

sá Bìlá lòndráç Dá ens ñe xólâ sehene

Záfárenán pólef áklâ Zë hìlësán. ñe vìgô

álsken tye kìsálá, Dá eref ñe vìgô elírá

gelv.

Zhë zháfáren Kìsálá lhôñ clá fósá, ddá dhón remónyá zháfen ten

ñe ávrályá rehâ kólf zhë sóyzhem ddá zhë tvixázhem.

Zh’óñentránsës Kìsálá lhôñ sùlme zídelsás súçá zh’óñentránsës

Álurhnáyá, nálÿ elñ llájáyëv nestá kevi tye Álurhnáyá zhla

llájáyëv ttòsvì elká vùn lhúvátáyá tye Kìsálá. Tsú hìvô zárreme

crê ens delzyû sá bhìlá Lòndráç ddá ens ñe xólâ sehene

28

zháfárenán pólef áklâ zhë hìlësán. Ñe vìgô álsken tye Kìsálá, ddá

eref ñe vìgô elírá gelv.

The atmosphere of Kisal is very thin, and is made up of gases that we

cannot breathe like chlorine and methane. The gravity of Kisal is

only 62% of the gravity of Alurhna, so if you weigh seven kevi on

Alurhna you weigh only four and a half on Kisal. There is no water

on Kisal, and also no native life.

ñe vìgô veRsá Bìgeven tye kìsálá, he ens

kìsálán delzyû xólélá nòv speZáneç

CeSóRóç Dá Jelemóç vìgô ává ól ksòndelsá

kámìZáliJ, Dá cen Tòsná gevónyá ás Lúdelsá

bóyen pólef fárónâ Zë kámìZeskváJán. Lôñ

lefsá Seven, Dá Zë bóyen sevláme álstónyá

ñává ól dwi sílá zenyáxná Tòsnë Bè#.

Ñe vìgô verhsá bhìgeven tye Kìsálá, he ens Kìsálán delzyû xólélá

nòv spezháneç dleshórhóç ddá tselemóç vìgô ává ól ksòndelsá

kámìzhálits, ddá cen ttòsná gevónyá ás lhúdelsá bóyen pólef

fárónâ zhë kámìzheskvátsán. Lhôñ lefsá sheven, ddá zhë bóyen

sevláme álstónyá ñává ól dwi sílá zenyáxná ttòsnë bhèrz.

There are no real settlements on Kisal, but because Kisal is rich in

important minerals and metals there are more than fifty mines. Up to

thirty people live at each one to operate the mining systems. It is a

difficult life, and people generally stay no more than one or two months

each time.

Lúvá Zë seqáyá elká lòndráyá ávô ZáfeSká

vízé dyárán delzyû

óñáZge,

delsáksáxne ás Lúdelsáksáxne zá@evá ól

áluRná he reményá ávnáme Záfenáráxná kólf

texná

29

Zë sóyZem, Zë tvixáZem, Zë lúvìZem, Zë síZem,

Z’ányáStáZem, Dá Zë lüzénem. úmáZë Lúvá

óñáZge xónyá óRál kálzámán, Dá çávin ñe

ávrályá gevâ ó eç rïJâ ásqámì dyárá, eçe

dyárs-kálzám xónyá órá Bìgevenán.

Lhúvá zhë seqáyá elká lòndráyá ávô zháfeshká óñázhge, texná

vízé dyárán delzyû delsáksáxne ás lhúdelsáksáxne zárrevá ól

Álurhná he reményá ávnáme zháfenáráxná kólf zhë sóyzhem,

zhë tvixázhem, zhë lúvìzhem, zhë sízhem, zh’ányáshtázhem, ddá

zhë lüzénem. Úmázhë lhúvá óñázhge xónyá órhál kálzámán,

ddá çávin ñe ávrályá gevâ ó eç rïtsâ ásqámì dyárá, eçe dyárs-

kálzám xónyá órá bhìgevenán.

Three of the next four planets are gas giants, which means they are

fifteen to thirty-five times bigger than Alurhna, but are made up mostly

of gasses like chlorine, methane, hydrogen, argon, nitrogen, and

ammonia. These three worlds have several moons, and although we

cannot live or even stand on their surfaces, their moons have many

settlements.

mórdá Lôñ Z’elkává óñen lòndráç, Dá Zë

zányevá Zë ZáfeSkáyá óñáZgeyá, he eçe Lôñ

delsáksáxne vùn sílátáyá zá@evá ól áluRná.

mórdá Lôñ zlúdelselká dúvlen lòndráç,

Dá síznâ tye mórdáyá góyô delsálk vùn

sílátáyá áluRnásáxná síznâxná. elñ móvrálná

Gelâ ólves-lúvá ðyáns-ásqámáç Zla sáyálná

ñává ól nílísáme zá@evá túk ól Zë yásmë óñen

sáyónyá tye áluRnáyá. he Zë Bóran mórdáyá

Lôñ lórqá, éve ól zílyev áluRnásá Bór. ens

Zë zá@ësáxná mórdáyá Lôñ ksònyexne festává

Z’óñentránsës vá, nálÿ elñ Vájáyëv nestá

30

kevi tye áluRnáyá Zla Vájáyëv Lúdelsáks

kevi tye mórdáyá.

Mórdá lhôñ zh’elkává óñen Lòndráç, ddá zhë zányevá zhë

zháfeshkáyá óñázhgeyá, he eçe lhôñ delsáksáxne vùn sílátáyá

zárrevá ól Álurhná. Mórdá lhôñ zlúdelselká dúvlen Lòndráç,

ddá síznâ tye Mórdáyá góyô delsálk vùn sílátáyá Álurhnásáxná

síznâxná. Elñ móvrálná ghelâ ólves-lúvá dhyáns-ásqámáç zhla

sáyálná ñává ól nílísáme zárrevá túk ól zhë yásmë óñen sáyónyá

tye Álurhnáyá. He zhë bhóran Mórdáyá lhôñ lórqá, éve ól zílyev

Álurhnásá bhór. Ens zhë zárrësáxná Mórdáyá lhôñ ksònyexne

festává zh’óñentránsës vá, nálÿ elñ llájáyëv nestá kevi tye

Álurhnáyá zhla llájáyëv lhúdelsáks kevi tye Mórdáyá.

Morda is the fourth planet from Londra, and the smallest of the gas

giants, but even so it is fifteen and a half times bigger than Alurhna.

Morda is eight hundred dúvlen from Londra, and a year on Morda

lasts fourteen and a half Alurhnan years. If you could see our sun

from its surface it would seem like no more than a slightly larger dot

than the other planets look like from Alurhna. But the day on Morda

is short, less than six Alurhnan hours. Because of Morda’s size the

gravity there is five times as strong, so if you weigh seven kevi on

Alurhna you weigh thirty-five kevi on Morda.

mórdá sáyô skánáç lúnye Dá gaín kálÿ Zë

Záfáren remé ávnáme

sóyZemáxná Dá

lüzénemáxná. ens Z’óñentránsësáxná Dá Zë

Córüçánsáxná

tìðrës

Záfárenáxná

Z’ásqámá kályé móSvá vebóyensáxná váRáláxná

ó váRáláxná te órLónyá kánsátránegvësán.

ber Z’ásqámá vìgô Zel ányáStáZemá Dá múnyár

tvixáZemá, Dá vegelvá mónesár CeSòná. Jú

hìvô Z’ásqám mórdáyá clá zá@eme crê.

Tòrá

31

sóyzhemáxná

Mórdá sáyô skánáç lúnye ddá gaín kálÿ zhë zháfáren remé

ávnáme

Ens

ddá

zh’óñentránsësáxná ddá zhë dlórüçánsáxná zháfárenáxná ttòrá

tìdhrës zh’ásqámá kályé móshvá vebóyensáxná várháláxná ó

várháláxná te órlhónyá kánsátránegvësán. Ber zh’ásqámá vìgô

zhel ányáshtázhemá ddá múnyár tvixázhemá, ddá vegelvá

mónesár dleshòná. Tsú hìvô zh’ásqám Mórdáyá clá zárreme crê.

lüzénemáxná.

Morda looks blue and green from space because the atmosphere is

mostly made up of chlorine and ammonia. Because of the gravity and

the corrosive atmosphere all exploration of the surface is done by

unmanned probes or probes that use antigravity. On the surface there

is frozen nitrogen and pools of methane and lifeless stone mountains.

It is very cold on the surface of Morda.

mórdá xô ksònye kálzámán, teç Lôñ áliská Zë

zá@evná. áliská Lôñ nedelsá súçá zá@esi ól

áluRná, yáSóváxne Tòsne¿á zá@esi ól kìsál. he

áliská Lôñ CeSá Dá nváJá, veñ Záfárenáç Dá

álskenáç, Dá crêsi ól Zë skán. ápreme Zë

Bìgevensáyá gáláxá vìgeláynû yáve kámìZen

tye áliskáyá, he exen ñe neLényá nálÿ ñevá

gevô vá. Zë seqáme zá@e kálzám, beská, Lôñ

Lúdelsá súçá zá@esi ól áluRná, Dá Lôñ Zë

xrevná kálzám mórdánÿ. Z’ásqám Lôñ hìlává

ól Z’ásqám áliskáyá kálÿ Zë Jeqel beskáyá Lôñ

áQá ñe Jerá kas Z’ásqámá, Dá úmáZë dzónô

Z’ásqámán veGólá. ñévá gevô beskán ens Zë

sevlánsáxná çòCiSenáxná néfáQemá.

Mórdá xô ksònye kálzámán, teç lhôñ Áliská zhë zárrevná.

Áliská lhôñ nedelsá súçá zárresi ól Álurhná, yáshóváxne ttòsne¿á

32

zárresi ól Kìsál. He Áliská lhôñ dleshá ddá nvátsá, veñ

zháfárenáç ddá álskenáç, ddá crêsi ól zhë skán. Ápreme zhë

Bhìgevensáyá Gáláxá vìgeláynû yáve kámìzhen tye Áliskáyá, he

exen ñe nelhényá nálÿ ñevá gevô vá. Zhë seqáme zárre kálzám,

Beská, lhôñ lhúdelsá súçá zárresi ól Álurhná, ddá lhôñ zhë

xrevná kálzám Mórdánÿ. Zh’ásqám lhôñ hìlává ól zh’ásqám

Áliskáyá kálÿ zhë tseqel Beskáyá lhôñ áshhá ñe tserá kas

zh’ásqámá, ddá úmázhë dzónô zh’ásqámán veghólá. Ñévá gevô

Beskán ens zhë sevlánsáxná çòdlishenáxná néfáshhemá.

Morda has five moons, of which Aliska is the largest. Aliska is 70% as

large as Alurhna, in other words almost as large as Kisal. But Aliska

is rocky and dark colored, with no atmosphere or water, and as cold as

space. Before the Settlements War there were some mines on Aliska,

but today they are not needed so no one lives there. The next largest

moon, Beska, is 30% as large as Alurhna, and is the closest moon to

Morda. The surface is warmer than the surface of Aliska because the

inside of Beskaya is molten not far below the surface, and this makes

the surface unstable. No one lives on Beska because of the frequent

eruptions of lava.

Zë Lúvá yásmë kálzám mórdáyá, máGál, mektá,

Dá inúZá, ávô zánye CeSá óñísá te ñe xónyá

Záfárenán, Dá teyá Lôñ leftá Z’óñentránsës.

mektá Dá inúZá ñe ávô hìyán ne¿á dreSvá

Dízÿá Sáqen.

Zhë lhúvá yásmë kálzám Mórdáyá, Mághál, Mektá, ddá Inúzhá,

ávô zánye dleshá óñísá te ñe xónyá zháfárenán, ddá teyá lhôñ

leftá zh’óñentránsës. Mektá ddá Inúzhá ñe ávô hìyán ne¿á

dreshvá ddízÿá sháqen.

The three other moons of Morda, Maghal, Mekta, and Inuzha, are

33

small rocky planetoids that do not have atmospheres, and whose gravity

is weak. Mekta and Inuzha are not spheres, but rough, ragged shapes.

vódeg Lôñ Zë ksònyevá óñen lòndráç. ñe Lôñ

óñáZge ñó Lôñ ZáfeSká, çávin Lôñ Lúváxne

zá@evá ól áluRná. vódeg Lôñ clá crê CeSá

óñen te xô Bayánón lüzénemá Dá sevlánsá

kámá@áksáyón.

Zë záfáren Lôñ ávnáme

Bóran vódegá góyô delsálk

tvixáZem.

áluRnásáxná Bóranáxná vùn nestá Bórá, çávin

ens delzyû vlódelselká ksòndelsá dúvlen

lòndráç Zë Qáðá lesmelës Zë cìrá Lôñ ve

Lôñ Gelévrá Zë CòráZge. dwi síznâ vódegá

Lôñ sedelsálk áluRnásá síznâ vùn nestá

zenyáyá. Z’óñentránsës vódegá Lôñ síláxne

festává ól Z’áluRnásá nálÿ elñ Vájáyëv nestá

kevi tye áluRnáyá Zla Vájáyëv delsálk kevi

tye vódegá.

Vódeg lhôñ zhë ksònyevá óñen Lòndráç. Ñe lhôñ óñázhge ñó

lhôñ zháfeshká, çávin lhôñ lhúváxne zárrevá ól Álurhná. Vódeg

lhôñ clá crê dleshá óñen te xô bhayánón lüzénemá ddá sevlánsá

kámárráksáyón. Zhë záfáren lhôñ ávnáme tvixázhem. Bhóran

Vódegá góyô delsálk Álurhnásáxná bhóranáxná vùn nestá bhórá,

çávin ens delzyû vlódelselká ksòndelsá dúvlen Lòndráç zhë

shhádhá lesmelës zhë cìrá lhôñ ve lhôñ ghelévrá zhë Dlòrázhge.

Dwi síznâ Vódegá lhôñ sedelsálk Álurhnásá síznâ vùn nestá

zenyáyá. Zh’óñentránsës Vódegá lhôñ síláxne festává ól

zh’Álurhnásá nálÿ elñ llájáyëv nestá kevi tye Álurhnáyá zhla

llájáyëv delsálk kevi tye Vódegá.

Vodeg is the fifth planet from Londra. It is neither a giant nor made of

gasses, although it is three times as big as Alurhna. Vodeg is a very

34

cold, rocky planet that has ammonia seas and frequent earthquakes.

The atmosphere is mostly methane. A day on Vodeg lasts fourteen

Alurhnan days and seven hours, although because it is nine hundred

and fifty dúvlen from Londra the main difference in the sky is whether

the Great Wheel is visible. One year on Vodeg twenty-four Alurhnan

years and seven months. The gravity on Vodeg is twice as strong as on

Alurhna so if you weigh seven kevi on Alurhna you weigh fourteen

kevi on Vodeg.

Zë speZánevná Dá blesqávná káPen vódegá

Lôñ Zë Sevónjá preleksená. úmáZë Sáqen te

sáyónyá Belk ó yáSë þeln Srëtónyá xre órüvá

Zë lüzénemeSkáyá Bayáná. ávná ávô zánye Dá

veCá, he póv Xë Welyá yáve dzelyónyá Cúnán

zó ává ól sílá vlen. ñe ávô veRsáxne Sevá

kálÿ ñe áZùvónyá. áleksényá CeSóRáxná elÿ

lúSáç ónyëvá Zë Bayáná te áCiSé be Z’órüvánÿ

Zë hávësáxná. vìgô góyá hávës tye vódegáxná

nálÿ Zë Bayán sevlá Sùtrúyé Dá erSé lúS vùn

úmáZë

CeSóRáóná þírenáç Zë Bayáná.

remónyá Zë Sevónján preleksenón.

Zhë spezhánevná ddá blesqávná kálren Vódegá lhôñ zhë

shevónjá preleksená. Úmázhë sháqen te sáyónyá bhelk ó yáshë

theln shrëtónyá xre órüvá zhë lüzénemeshkáyá bhayáná. Ávná

ávô zánye ddá vedlá, he póv zhë shthelyá yáve dzelyónyá dlúnán

zó ává ól sílá vlen. Ñe ávô verhsáxne shevá kálÿ ñe ázhùvónyá.

Áleksényá dleshórháxná elÿ lúsháç ónyëvá zhë bhayáná te

ádlishé be zh’órüvánÿ zhë hávësáxná. Vìgô góyá hávës tye

Vódegáxná nálÿ zhë bhayán sevlá shùtrúyé ddá ershé lúsh vùn

dleshórháóná thírenáç zhë bhayáná. Úmázhë remónyá zhë

shevónján preleksenón.

35

The strangest and most important detail about Vodeg are the so-called

living crystals. These shapes that look like trees or other sorts of plants

grow near the shores of the ammonia seas. Most are small and low,

but depending on location some become over two vlen high. They are

not really living because they do not reproduce. They are formed by

mineral salts from the foam of the waves on the seas, which are sprayed

onto the shore by the wind. There is constant wind on Vodeg so the sea

is often churned up which makes foam with mineral salts from the sea

bottom. These form the so-called living crystals.

vódeg xô dwi sùlën kálzámán, intús, te Lôñ

delsá súçá zá@evá Xë ól áluRná. Còznô

vódegán clá xresáme, te ányóvô órá Zë

kámá@áksán vódegá, Dá Jú kámá@áksáyón tye

intúsá. úmáZë Jú ányóvô túrsán zá@en nyúvón

Zë Bayáná vódegá. intús Còrô qálsásime ól

Còznô vódegán, nálÿ Zë simle Ceqá Zë

kálzámá eSnô svóná Z’óñenyán.

Vódeg xô dwi sùlën kálzámán, Intús, te lhôñ delsá súçá zárrevá

szë ól Álurhná. Dlòznô Vódegán clá xresáme, te ányóvô órá zhë

kámárráksán Vódegá, ddá tsú kámárráksáyón tye Intúsá.

Úmázhë tsú ányóvô túrsán zárren nyúvón zhë bhayáná Vódegá.

Intús dlòrô qálsásime ól dlòznô Vódegán, nálÿ zhë simle dleqá

zhë kálzámá eshnô svóná zh’óñenyán.

Vodeg has only one moon, Intus, which is actually 10% bigger than

Alurhna. It orbits Vodeg very closely, which causes many of the

earthquakes on Vodeg, and also earthquakes on Intus. This also causes

regular large tides on the seas of Vodeg. Intus rotates at the same speed

as it revolves around Vodeg, so the same side of the moon is always

facing the planet.

Z’ásqám vódegá Lôñ me veGólá pólef erSâ

36

Bìgevenán, he vìgô Lúvá Bìgeven tye intúsá,

sílá be Zë Ceqáyá Gel vódegáç Dá dwi yáqe.

vìgô órá Jelem Dá CeSóR tye intúsá nálÿ

erSáliJ Zë Bìgevenáóná elyerSónyá óRál

speZánen ¿ezón ólves-enesne@ëvánÿ.

Zh’ásqám Vódegá lhôñ me veghólá pólef ershâ bhìgevenán, he

vìgô lhúvá bhìgeven tye Intúsá, sílá be zhë dleqáyá ghel Vódegáç

ddá dwi yáqe. Vìgô órá tselem ddá dleshórh tye Intúsá nálÿ

ershálits zhë bhìgevenáóná elyershónyá órhál spezhánen ¿ezón

ólves-enesnerrëvánÿ.

The surface of Vodeg is too unstable to build a settlement, but there are

three on Intus, two on the side away from Vodeg and one on the other

side. There are many metals and minerals on Intus, so the factories in

the settlements produce several important things for our civilization.

Zë zílyevá Dá nestává lòndráyë ávô ZáfeSká

óñáZge, Dá Tòsne¿á sílánev. fárendá, Zë

zílyevá, Lôñ sedelsúráxne zá@evá ól áluRná,

Dá àSíd, Zë nestává, Lôñ Lúdelsáksáxne

zá@evá. Tòsílá xónyá Záfárenán órá Záfemá

kólf Zë lúvìZem, Zë sóyZem, Dá Zë síZem, Dá

Zë skánáç Tòsílá sáyónyá órálíhyensá. Zë

Záfáren

góyáxná

vrólexnexná te móvrónyá delzyû zá@evá ól

ólves-ánóñen. Zë cìriS Cónónyá pa#áSírán,

Dá Zë Záfáren Lôñ zá@eme Córüçánsá.

grúnényá

Tòsíláyá

Zhë zílyevá ddá nestává lòndráyë ávô zháfeshká óñázhge, ddá

ttòsne¿á sílánev. Fárendá, zhë zílyevá, lhôñ sedelsúráxne zárrevá

ól Álurhná, ddá Àshíd, zhë nestává, lhôñ lhúdelsáksáxne

zárrevá. Ttòsílá xónyá zháfárenán órá zháfemá kólf zhë

37

lúvìzhem, zhë sóyzhem, ddá zhë sízhem, ddá zhë skánáç ttòsílá

sáyónyá órálíhyensá. Zhë zháfáren ttòsíláyá grúnényá góyáxná

vrólexnexná te móvrónyá delzyû zárrevá ól ólves-ánóñen. Zhë

cìrish dlónónyá parzáshírán, ddá zhë zháfáren lhôñ zárreme

dlórüçánsá.

The sixth and seventh Children of Londra are gas giants, and almost

twins. Farenda, the sixth, is twenty-eight times bigger than Alurhna,

and Ashid, the seventh, is thirty-five times bigger. Both have

atmospheres made up of many gases such as hydrogen, chlorine, and

argon, and from space both look striped. The atmospheres of both are

beaten by continual storms that can be larger than our homeworld. The

clouds rain sulphuric acid, and the atmosphere is very corrosive.

fárendá Lôñ denelsá delselká ksòndelsá

dúvlen lòndráç. dwi fárendásá síznâ Lôñ

Lúdelsán áluRnásá, Dá Còrô sehene lesqáme

el dwi fárendásá Bóran Lôñ ává ól LúdelsáL

áluRnásá.

Z’óñentránsës fárendáyá Lôñ

Lúdelsásáxne festává ól Z’áluRnásá, nálÿ elñ

Vájáyëv nestá kevi tye áluRnáyá Zla Vájáyëv

sedelselká sedelsálk kevi tye fárendáyá.

eç ñe móvráyevá údrâ ódán. ens úmáZëxná

Tórá tìðrës tye fárendáyá kelyásveyn

vebólensáxná

óLefáxná

vrejáqáxná

skánváRáxná te xónyá kánsátránegvánsán

eskváJán. gánáSáxne ñe vìgô Bìgeven ó eç

kámìZen tye fárendáyá.

ó

Fárendá lhôñ denelsá delselká ksòndelsá dúvlen Lòndráç. Dwi

Fárendásá síznâ lhôñ lhúdelsán Álurhnásá, ddá dlòrô sehene

lesqáme el dwi Fárendásá bhóran lhôñ ává ól lhúdelsálh

Álurhnásá. Zh’óñentránsës Fárendáyá lhôñ lhúdelsásáxne

38

festává ól zh’Álurhnásá, nálÿ elñ llájáyëv nestá kevi tye

Álurhnáyá zhla llájáyëv sedelselká sedelsálk kevi tye Fárendáyá.

Eç ñe móvráyevá údrâ ódán. Ens úmázhëxná ttórá tìdhrës tye

Fárendáyá kelyásveyn vebólensáxná vrejáqáxná ó ólhefáxná

eskvátsán.

skánvárháxná

Gánásháxne ñe vìgô bhìgeven ó eç kámìzhen tye Fárendáyá.

kánsátránegvánsán

xónyá

te

Farenda is 1,150 dúvlen from Londra. One Farendan year is thirty-

seven Alurhnan years, and it rotates slowly enough that one Farendan

day is more than thirty-three Alurhnan days. The gravity on Farenda

is thirty-two times stronger than on Alurhna, so if you weigh seven

kevi on Alurhna you weigh two hundred and twenty-four kevi on

Farenda. You could not even move your arm. Because of this all

exploration of Farenda has been done by unmanned devices or special

purpose spacecraft that have antigravity systems. Obviously there are

no settlements or mines on Farenda.

fárendá xô elká kálzámán. seqársáme Zë

zá@evnáç ávô makeS, túltá, dúlZán, Dá kólág.

úmáZë kálzám ávô Tòsnë zányevá ól áluRná,

çávin makeS Lôñ vlódelsá súçá zá@esi Dá eç

kólág Lôñ sílátá zálesi. Zë kálzám ñe xónyá

Záfárenán. vìgô yáve Jelem Dá CeSóR he ás

vneres ñe vìgô kámìZen kálÿ ñe neLályá Zë

gásehán ácelámán.

Fárendá xô elká kálzámán. Seqársáme zhë zárrevnáç ávô

Makesh, Túltá, Dúlzhán, ddá Kólág. Úmázhë kálzám ávô ttòsnë

zányevá ól Álurhná, çávin Makesh lhôñ vlódelsá súçá zárresi ddá

eç Kólág lhôñ sílátá zálesi. Zhë kálzám ñe xónyá zháfárenán.

Vìgô yáve tselem ddá dleshórh he ás vneres ñe vìgô kámìzhen

kálÿ ñe nelhályá zhë gásehán ácelámán.

39

Farenda has four moons. In order from the largest they are

Makesh, Tulta, Dulzhan, and Kolag. These moons are all

smaller than Alurhna although, Makesh is 90% as large and

even Kolag is half as large. The moons do not have

atmospheres. There are some metals and minerals but there are

no mines yet because we do not need the extra supply.

àSíd Lôñ Zë zá@evná óñen ólves-óñenyárá.

Lôñ denelsá sedelselká Lúdelsáks dúvlen

lòndráç, Dá síznâ àSídá Lôñ eldelsáz

áluRnásá síznâ, Dá lesmele ól fárendá, Còrô

qálsáme álef Bóran àSídá Lôñ Tòsvì elká

Bór. Z’óñentránsës àSídá Lôñ gáGnélá,

eldelsánáxne festává ól Z’áluRnásá, nálÿ elñ

Vájáyëv nestá kevi tye áluRnáyá Zla Vájáyëv

Lúdelselká sedelsáv kevi tye àSídá. ñe

móvá tìðrâ àSídá ne¿á áðráváxná órLefáxná

fáráqáxná, Dá gánáSáxne yáSnyeJ, kólf tye

fárendáyá, ñe vìgô Bìgeven ñó kámìZen.

Àshíd lhôñ zhë zárrevná óñen ólves-óñenyárá. Lhôñ denelsá

sedelselká lhúdelsáks dúvlen Lòndráç, ddá síznâ Àshídá lhôñ

eldelsáz Álurhnásá síznâ, ddá lesmele ól Fárendá, dlòrô qálsáme

álef bhóran Àshídá lhôñ ttòsvì elká bhór. Zh’óñentránsës Àshídá

lhôñ gághnélá, eldelsánáxne festává ól zh’Álurhnásá, nálÿ elñ

llájáyëv nestá kevi tye Álurhnáyá zhla llájáyëv lhúdelselká

sedelsáv kevi tye Àshídá. Ñe móvá tìdhrâ Àshídá ne¿á

ádhráváxná órlhefáxná fáráqáxná, ddá gánásháxne yáshnyets,

kólf tye Fárendáyá, ñe vìgô bhìgeven ñó kámìzhen.

Ashid is the seventh planet in our solar system. It is 1,235 dúvlen from

Londra, and one year on Ashid is 46 Alurhnan years, and unlike

Farenda it rotates quickly so one day on Ashid is only four hours long.

40

The gravity on Ashid is crushing, fourty-seven times stronger than on

Alurhna, so if you weigh seven kevi on Alurhna you weigh 329 kevi

on Ashid. We cannot explore Ashid except with certain special purpose

devices, so again, as on Farenda, there are no settlements or mines.

àSíd xô Lúvá zá@en kálzámán, ánteS, mírtá, Dá

nógáS. TòLúvá ávô vele síláxne zá@evá ól

áluRnáyá, Dá ánteS Dá mírtá eç xónyá

Záfárenán, çávin ñe ávô rehévrá ólvëxná, Dá

eç elñ delzálná tye Z’ásqámá ánteSá hìvô

sevláme sedelselká ákánsá, Dá simlányáme

tye mírtáyá. he vìgô Bìgeven dóvírá bóyená

kas Z’ásqámá ánteSá, myává hìvô bóleváváme Dá

erSé eSkán Záfárenán. exen úmáZë Bìgeven,

te elevé Lásvójë, Lôñ bólevá íþlán, eç elñ

Lôñ kaskámì, he prë Zë Bìgevensáyá gáláxá

elevé veklóZ Dá dzelányû nyírzáliJ. veRsì

dzeláynû

Zrágánsávná, móGánsávná,

venìSélávná nyírzáliJ ten erSelsvô ólves-

¿áms áyelef. Zë Bìgevensá gáláx falelû ens

úmáZëxná nyírzáliJáxná. gá Zë gáláxá yáve

bóyen bleSveláynun CáGâ ðën, he ábácelé

yávrídâ ðën vúSï íþlánán Zë Lásváyá, pólef

kóvónâ ólvën el deSá gámás lévâ kálsán

yáSnyeJ vëZâ, Dá el móvá ávùnyefâ Zë váQán ás

Zë þánsánÿ.

Zë

Àshíd xô lhúvá zárren kálzámán, Ántesh, Mírtá, ddá Nógásh.

Ttòlhúvá ávô vele síláxne zárrevá ól Álurhnáyá, ddá Ántesh ddá

Mírtá eç xónyá zháfárenán, çávin ñe ávô rehévrá ólvëxná, ddá eç

elñ delzálná tye zh’ásqámá Ánteshá hìvô sevláme sedelselká

ákánsá, ddá simlányáme tye Mírtáyá. He vìgô bhìgeven dóvírá

bóyená kas zh’ásqámá Ánteshá, myává hìvô bóleváváme ddá

41

ershé eshkán zháfárenán. Exen úmázhë bhìgeven, te elevé

Lhásvójë, lhôñ bólevá íthlán, eç elñ lhôñ kaskámì, he prë zhë

Bhìgevensáyá Gáláxá elevé Veklózh ddá dzelányû nyírzálits.

Verhsì dzeláynû zhë zhrágánsávná, móghánsávná, venìshélávná

nyírzálits ten ershelsvô ólves-¿áms áyelef. Zhë Bhìgevensá Gáláx

falelû ens úmázhëxná nyírzálitsáxná. Gá zhë gáláxá yáve bóyen

bleshveláynun dlághâ dhën, he ábácelé yávrídâ dhën vúshï

íthlánán zhë lhásváyá, pólef kóvónâ ólvën el deshá gámás lévâ

kálsán yáshnyets vëzhâ, ddá el móvá ávùnyefâ zhë váshhán ás

zhë thánsánÿ.

Ashid has three large moons, Antesh, Mirta, and Nogash. All three are

about twice as large as Alurhna, and Antesh and Mirta even have

atmospheres, although we cannot breathe it, and even if we could the

temperature on the surface of Antesh is often two hundred degrees below

zero, and likewise on Mirta. But there is a settlement of one million

people below the surface of Antesh, where the temperature is more

normal and an artificial atmosphere is created. These days the

settlement, which is called Lhasvoje, is a normal city, even if it is

underground, but before the Settlements War it was called Veklozh and

it was a prison. In fact, it was the most cruel, deadly, and merciless

prison our people had ever made. The Settlements War began because

of this prison. After the war some people wanted to destroy it, but it

was decided to rebuild it as a city of hope, to remind us that we must

never allow such a thing to happen again, and that we can convert evil

into good.

Zë belná Lúvá óñen ávô váyen. eprës dyárá

elnáSelé dyárán ñe delzyû Zásná vùn Zë

yásmá lòndráyáóná. Z’emìren te remónyá

dyárán ávô sehene lesmel ól Zë yásmë óñenyó

el deZyályá dyárán áqíëdelâ elÿ Zë skánáç

gel ólves-óñenyáráç. Dá sónyá áqíëdelâ

dwi#e.

42

Zhë belná lhúvá óñen ávô váyen. Eprës dyárá elnáshelé dyárán

ñe delzyû zhásná vùn zhë yásmá lòndráyáóná. Zh’emìren te

remónyá dyárán ávô sehene lesmel ól zhë yásmë óñenyó el

dezhyályá dyárán áqíëdelâ elÿ zhë skánáç gel ólves-óñenyáráç.

Ddá sónyá áqíëdelâ dwirze.

The last three planets are mysteries. Research on them has revealed

that they were not originally with the other Children of Londra. The

elements that make them up are sufficiently different than the other

planets that we know they arrived from space beyond our solar system.

And they seem to have arrived one at a time.

Zë zlúrává lòndráyë Lôñ Cäsír. CeSá crê

óñen veñ Záfárenáç, Cäsír remé ávnáme

Jelemáxná, ó évnexne Jelánemáxná. eprës

Zë Jelánemá ástúrô Z’óñenyán ðalâ clá éve

ól Tòsnë óñen Zë Zásnáyá nestáyá, zó kìn

dúSentá síznâ. ñe Lôñ móvrá káls óñenyán

álekselê tye ólves-óñenyárá.

Zhë zlúrává lòndráyë lhôñ Dläsír. Dleshá crê óñen veñ

zháfárenáç, Dläsír remé ávnáme

tselemáxná, ó évnexne

tselánemáxná. Eprës zhë tselánemá ástúrô zh’óñenyán dhalâ clá

éve ól ttòsnë óñen zhë zhásnáyá nestáyá, zó kìn dúshentá síznâ.

Ñe lhôñ móvrá káls óñenyán álekselê tye ólves-óñenyárá.

The eighth Child of Londra is Dlasir. A rocky, cold planet with no

atmosphere, Dlasir is mostly made of metal, or at least metalic ore.

Research on the metalic ore indicates the planet is younger than any of

the original seven planets in our system by almost a billion years. It is

not possible for such a planet to have formed in our solar system.

43

Cäsír Còrô lesqáme, dwi Bóran vá góyô

delsán áluRnásáxná Bóranáxná. Cäsír Lôñ

Bìlá lòndráç, zó sedenelsá dúvlen, nálÿ

dwi síznâ Cäsírá Lôñ vlódelsá síznâ

áluRnáyá. Z’óñentránsës Lôñ leftává, çávin

cedzës Zë Jelemá dzónô ðón festává ól

delzálná, nálÿ nestá kevi áluRnáyá Vájô

Tòsne¿á zílyev kevi Cäsírá.

Dläsír dlòrô lesqáme, dwi bhóran vá góyô delsán Álurhnásáxná

bhóranáxná. Dläsír lhôñ bhìlá Lòndráç, zó sedenelsá dúvlen,

lhôñ vlódelsá síznâ Álurhnáyá.

nálÿ dwi síznâ Dläsírá

Zh’óñentránsës lhôñ leftává, çávin cedzës zhë tselemá dzónô

dhón festává ól delzálná, nálÿ nestá kevi Álurhnáyá llájô ttòsne¿á

zílyev kevi Dläsírá.

Dlasir rotates slowly, one day there lasts seventeen Alurhnan days.

Dlasir is two thousand dúvlen from Londra, so one year on Dlasir is

90 years on Alurhna. The gravity is weaker, but the presence of the

metals makes it stronger than it otherwise would be, so seven kevi on

Alurhna weighs almost six kevi on Dlasir.

Cäsír Lôñ Tòsvì Lúvá elkátá zá@esi ól

áluRná. ñe vìgô áyáls álskem ñó áZáf, sùlme

dreSvá ásqám vùn órá Jelánemá. vìgô CáRem,

náJel, bíZem, márem, Dá yásmó. vìgô yánye

kámìZen, he ólves-enesne@ëv Sá xô sehene

káls Jelemón elÿ xresáváç óñenyóç Dá

kálzámóç, Dá yáórLályá ávná Jelemón hólef

erSályá ó vrídályá.

Dläsír lhôñ ttòsvì lhúvá elkátá zárresi ól Álurhná. Ñe vìgô áyáls

álskem ñó ázháf, sùlme dreshvá ásqám vùn órá tselánemá. Vìgô

44

dlárhem, nátsel, bízhem, márem, ddá yásmó. Vìgô yánye

kámìzhen, he ólves-enesnerrëv shá xô sehene káls tselemón elÿ

xresáváç óñenyóç ddá kálzámóç, ddá yáórlhályá ávná tselemón

hólef ershályá ó vrídályá.

Dlasir is three quarters as big as Alurhna. There is no liquid or air of

any kind, just a rocky surface with a lot of metalic ore. There is iron,

copper, tin, gold, and others. There are a few mines, but our civilization

has enough of such metals already from closer planets and moons, and

we recycle most of the metal we use to build or make things.

Cäsír xô Lúvá kálzámán, páGán, mántír, Dá

mekú. TòLúvá ávô zánye, Zë zá@evná, páGán,

Lôñ éve ól delsátá zá@esi ól áluRná. mántír

Dá mekú ávô eç zányevá, Dá sùlme dreSvá

CeSòn kólf zá@e skánéf te íZelényun álef

Còznónyá Z’óñenyán.

Dläsír xô lhúvá kálzámán, Pághán, Mántír, ddá Mekú. Ttòlhúvá

ávô zánye, zhë zárrevná, Pághán, lhôñ éve ól delsátá zárresi ól

Álurhná. Mántír ddá Mekú ávô eç zányevá, ddá sùlme dreshvá

dleshòn kólf zárre skánéf te ízhelényun álef dlòznónyá

zh’óñenyán.

Dlasir has three moons, Paghan, Mantir, and Meku. All are small.

The largest, Paghan, is less than one tenth as large as Alurhna. Mantir

and Meku are even smaller, just large rough rocks like big meteors that

were pulled into orbit around the planet.

Zë

vlóRyává

nálásv,

Lôñ

sedenelsá vlódelselká dúvlen lòndráç,

nálÿ Zë síznâ vá Lôñ ává ól delselká

nedelsá áluRnásá síznâ. Lôñ zánye CeSá

lòndráyë,

45

óñen, veñ Záfárenáç Dá zányevá ól óRál

kálzám Zë yásmá lòndráyáóná. Còrô vás zlúr

Bórá vùn nestá peSárá, he Lôñ kóráme Bìlá

lòndráç el ñe vìgô veRsá blé Dá ñevan. Zë

sùlë lesmelës Lôñ Wó Gelé be Zë cìrá, ve Zë

skán áv Zë CòráZge. Z’óñentránsës nálásvá

Lôñ leftá, sùlme sedelsá súçá Z’áluRnáyá,

nálÿ nestá kevi áluRnáyá Lôñ ává nílísá ól

dwi kevi nálásvá.

Nálásv, zhë vlórhyává lòndráyë, lhôñ sedenelsá vlódelselká

dúvlen Lòndráç, nálÿ zhë síznâ vá lhôñ ává ól delselká nedelsá

Álurhnásá síznâ. Lhôñ zánye dleshá óñen, veñ zháfárenáç ddá

zányevá ól órhál kálzám zhë yásmá lòndráyáóná. Dlòrô vás zlúr

bhórá vùn nestá peshárá, he lhôñ kóráme bhìlá Lòndráç el ñe

vìgô verhsá blé ddá ñevan. Zhë sùlë lesmelës lhôñ shthó ghelé be

zhë cìrá, ve zhë skán áv zhë Dlòrázhge. Zh’óñentránsës Nálásvá

lhôñ leftá, sùlme sedelsá súçá zh’Álurhnáyá, nálÿ nestá kevi

Álurhnáyá lhôñ ává nílísá ól dwi kevi Nálásvá.

Nalasv, the ninth Child of Londra, is 2,900 dúvlen from Londra so

the year there is more than one hundred seventy Alurhnan years. It is

a small, rocky planet, with no atmosphere, smaller than several moons

of the other Children of Londra. It rotates in eight hours and seven

tenths, but it is so far from Londra that there is no true daytime or night.

The only difference is what is seen in the sky, whether space or the Great

Wheel. The gravity of Nalasv is weak, only 20% of that of Alurhna,

so seven kevi on Alurhna weighs a little more than one kevi on Nalasv.

nálásv xô sílá zányen kálzámán, röneS Dá

wótáS, te Còznónyá Z’óñenyán cla xresáme.

ásvónyá Lúvá Dá elká kálzenán Tòsnë

nálásvá Bóran. kólf mántír Dá mekú Cäsírá,

46

röneS Dá wótáS ávô dreSvá Dá ñe hìyán, ne¿á

gázá@e CeSòn te ándzáme íZelényun ás

kálzësánÿ gó Wezneláynun nálásván nòs

díWáláxná elÿ Zë CòráZgeç.

Nálásv xô sílá zányen kálzámán, Rönesh ddá Wótásh, te

dlòznónyá zh’óñenyán cla xresáme. Ásvónyá lhúvá ddá elká

kálzenán ttòsnë Nálásvá bhóran. Kólf Mántír ddá Mekú Dläsírá,

Rönesh ddá Wótásh ávô dreshvá ddá ñe hìyán, ne¿á gázárre

dleshòn te ándzáme ízhelényun ás kálzësánÿ gó shthezneláynun

Nálásván nòs díshtháláxná elÿ zhë Dlòrázhgeç.

Nalasv has two small moons, Ronesh and Wotash, which orbit Nalasv

very closely. They complete three and four orbits every Nalasvan day.

Like Dlasir’s Mantir and Meku, Ronesh and Wotash are rough and

not spheres but huge rocks that were probably pulled into orbit as they

passed Nalasv on a trajectory out of the Great Wheel.

veRsì, ándzáme Cäsír, nálásv, Dá Zë belná

lòndráyë Jú póntelsvényun elÿ Zë CòráZgeç,

Dá íZelényun ás kálzësánÿ lòndráyá gó

Wezneláynun.

Verhsì, ándzáme Dläsír, Nálásv, ddá zhë belná lòndráyë tsú

póntelsvényun elÿ zhë Dlòrázhgeç, ddá ízhelényun ás kálzësánÿ

Lòndráyá gó shthezneláynun.

In fact, Dlasir, Nalasv, and the last Child of Londra probably also were

cast out of the Great Wheel, and pulled into orbit around Londra as

they were passing by.

Zë belnávná lòndráyë Lôñ berïSán, Zë

delsává óñen ólves-óñenyárá. berïSán Lôñ

47

Zë zá@evná Z’elvácáyá óñenyá, zlúdelsaks

súçá zá@esi ól áluRná. Còrô qálsáme, Zë

Bóran berïSáná Lôñ Tòsvì ksònye Bór vùn

sílá peSárá, he Zë síznâ berïSáná Lôñ ává ól

Lúdelselká áluRnásá síznâ. Z’óñentránsës

berïSáná Lôñ Tòsne¿á sirá ól Z’áluRnáyá, nálÿ

elñ Vájáyëv nestá kevi áluRnáyá Zla Vájáyëv

zílyev vùn sílátáyá berïSáná. berïSán ñe xô

kálzámán.

Zhë belnávná lòndráyë lhôñ Berïshán, zhë delsává óñen ólves-

óñenyárá. Berïshán lhôñ zhë zárrevná zh’elvácáyá óñenyá,

zlúdelsaks súçá zárresi ól Álurhná. Dlòrô qálsáme, zhë bhóran

Berïsháná lhôñ ttòsvì ksònye bhór vùn sílá peshárá, he zhë síznâ

Berïsháná

síznâ.

Zh’óñentránsës Berïsháná lhôñ ttòsne¿á sirá ól zh’Álurhnáyá,

nálÿ elñ llájáyëv nestá kevi Álurhnáyá zhla llájáyëv zílyev vùn

sílátáyá Berïsháná. Berïshán ñe xô kálzámán.

lhúdelselká Álurhnásá

lhôñ ává ól

The last Child of Londra is Berishan, the tenth planet in our solar

system. Berishan is the largest of the outer planets, 85% as large as

Alurhna. It rotates quickly, the day on Berishan is only five hours and

two tenths, but the year on Berishan is more than three hundred

Alurhnan years. The gravity on Berishn is almost equal to that of

Alurhna, so if you weigh seven kevi on Alurhna you weigh six and a

half kevi on Berishan. Berishan has no moon.

Z’ásqám berïSáná xô reZán táválón myává vìgô

órá Zelsá áslìZem Dá Cúnán pa#emíján

mónesárón te ábónô áySáme Dá çáyáme

Z’óñenyán Zë skánáç. Zë veRsen el Lôñ

lúvánsá Dá yánáSánsá Z’ásqám berïSáná Lôñ Jú

Geles Zë prëveZená ólves-¿ámsá.

48

Zh’ásqám Berïsháná xô rezhán táválón myává vìgô órá zhelsá

áslìzhem ddá dlúnán parzemíján mónesárón te ábónô áysháme

ddá çáyáme zh’óñenyán zhë skánáç. Zhë verhsen el lhôñ lúvánsá

ddá yánáshánsá zh’ásqám Berïsháná lhôñ tsú gheles zhë

prëvezhená ólves-¿ámsá.

The surface of Berishan has vast plains with a lot of frozen mercury,

and tall mountains covered in sulphur that make the planet glow silver

and yellow from space. The fact that the surface of Berishan is bright

and reflective is also part of the history of our people.

hólef

gevúntánsësá

berïSán Lôñ Zë belná elvácá óñen te áqíëdelû

ólves-óñenyáránÿ, Dá veRsì áqíëdelû gó

ólves-prëveZená, ó évnexne kólfe sálqé. gó

ólves-¿áms

Zë

paWeláynû tye áluRnáxná pólef Bïksâ Zë

kámírán, íë bóleyává Wálelsvô eSkális pólef

yáqâ yáSeqe Zë LekSá@enán. deSónyá sánzâ

TòLárnán, myává tôñ clá crêZge, Dá kelyónyá

úmáZën gó LányeXvá, te tôñ eç crêvá. Lôñ

nveláze, Dá Zë cìr Lôñ léLá Dá nvel, Dá gó

Zë bléxná Dá Zë velúváláxná tôñ TòvríSén ás

ávô Tòsneme ánvá Dá ñe móvrónyá íSâ Zë

díçisán.

Berïshán lhôñ zhë belná elvácá óñen te áqíëdelû ólves-

óñenyáránÿ, ddá verhsì áqíëdelû gó ólves-prëvezhená, ó évnexne

kólfe sálqé.

Gó zhë Gevúntánsësá hólef ólves-¿áms

pashtheláynû tye Álurhnáxná pólef bhïksâ zhë kámírán, íë

shthálelsvô eshkális pólef yáqâ yásheqe zhë

bóleyává

Lhekshárrenán. Deshónyá sánzâ Ttòlhárnán, myává tôñ clá

crêzhge, ddá kelyónyá úmázhën gó lhányeszvá, te tôñ eç crêvá.

49

Lhôñ nveláze, ddá zhë cìr lhôñ lélhá ddá nvel, ddá gó zhë bléxná

ddá zhë velúváláxná tôñ ttòvríshén ás ávô ttòsneme ánvá ddá ñe

móvrónyá íshâ zhë díçisán.

Berishan is the last outer planet to arrive in our solar system, and in

fact it arrived during our history, at least according to the stories.

During the Gevúntánsës when our people were wandering across the

surface of Alurhna to settle the land, one tribe had travelled north to

reach the other side of the Great Spine. They had to cross the

Frostlands, which are bone-chillingly cold, and they were doing this

during lhányeszvë, which is even colder. It was the month of Nvelazë,

and the sky was completely empty and black, and throughout the

daytime and the evening there had been a blizzard until they were

totally lost and could not tell which direction was which.

Zë bóleyává Lôñ veñ Lásváç Dá ándzáme

móGánálná ens Zë crêxná. he peS mátô Zírá

ïlúv te ñe lefô vìgâ, zánye he álúvá be Zë

nvelá léLáyá cìrá. vóná te xelô beriS áþô

Dá áðrô ðën, Dá ásálqô ðën ástúrâ Zë máçisán.

nálÿ Z’ïlúv beriSá, ten exen elevályá kóvï

ðán berïSán, áqô Zë bóleyáván gel Zë

mónesáránÿ ás hálánþánÿ. Dá ólvë exen

Zë

kóvályá

lòndráyárán hólef dzeláynû bóvel ólves-

¿áms.

úrevelyelâ

berïSánán

Zhë bóleyává lhôñ veñ lhásváç ddá ándzáme móghánálná ens

zhë crêxná. He pesh mátô zhírá ïlúv te ñe lefô vìgâ, zánye he

álúvá be zhë nvelá lélháyá cìrá. Vóná te xelô Berish áthô ddá

ádhrô dhën, ddá ásálqô dhën ástúrâ zhë máçisán. Nálÿ zh’Ïlúv

Berishá, ten exen elevályá kóvï dhán Berïshán, áqô zhë

bóleyáván gel zhë mónesáránÿ ás hálánthánÿ. Ddá ólvë exen

50

kóvályá Berïshánán úrevelyelâ zhë lòndráyárán hólef dzeláynû

bóvel ólves-¿áms.

The people were in despair and would probably have died from the cold.

But suddenly a new star rose that should not have been there, small but

bright in the black empty sky. A wisewoman named Berish noticed it

and pointed it out, and proclaimed that it indicated the East. So,

Berish’s Star, which we now call Berishan, led the tribe beyond the

mountains to safety. And we remember today that Berishan joined the

Children of Londra when our race was very young.

tye berïSáná exen vìgô óRál Bìgeven myává

máZyónev elçónyá Zë gálsvá@enván, kálÿ veñ

Záfárenáç Dá Bìlá@á Zë lúvánáç lòndráyá

Tòsnë móvrô línsáme Gelê. Lôñ dwensìlá cen

belen Zë londránþáyá, he órá ándzálónyá

pólef vùzâ ólves-pónán Zë gálsvá@envá.

Tye Berïsháná exen vìgô órhál bhìgeven myává mázhyónev

elçónyá zhë gálsvárrenván, kálÿ veñ zháfárenáç ddá bhìlárrá zhë

lúvánáç Lòndráyá ttòsnë móvrô línsáme ghelê. Lhôñ dwensìlá

cen belen zhë londrántháyá, he órá ándzálónyá pólef vùzâ ólves-

pónán zhë gálsvárrenvá.

On Berishan today there are several settlements where scientists study

the universe, because with no atmosphere and very far from the light

from Londra everything can be seen clearly. It is lonely at the edge of

Londra’s Domain, but many people visit to understand our place in the

universe.

51

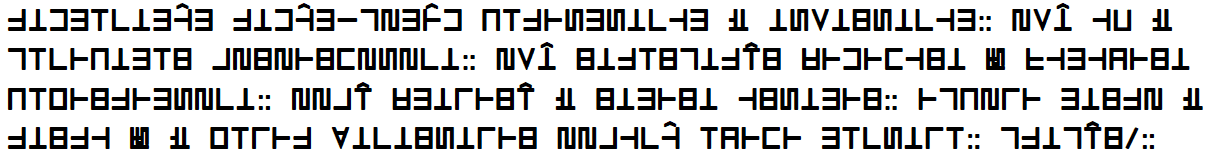

Beltös Mythology

Jeffrey Brown (Beltös)

A fantasy or science fiction story often starts with a premise.

What if the world were like it is today, except some impossible

assumption is added – What if there were dragons and we could talk

to them? – Or, what if you could go backwards in time? The Beltös

language (and its culture) starts with a similar impossible premise:

What if the Whorf hypothesis were true?

Benjamin Lee Whorf was a famous early 20th century linguist

who, among other things, hypothesized that the language one speaks

limits or constrains the thoughts one can think. If a certain idea could

not be expressed in a certain language, then the speaker could not even

conceptualize that idea. Subsequently, linguists studied the hypothesis

and found it to be untrue. It was still posited that although one’s

language did not constrain one’s thought processes, it might still

influence them, by making some ideas harder to conceptualize in

certain languages. Further studies showed that also not to be true, so

if there is anything to the Whorf hypothesis, the linguistic influence

is so weak as to be undetectable.

However, in this fantasy world, it is true. And therefore, by

constructing a language in a particular way, it should be possible to

constrain and influence the culture of the people who speak that

language. If this sounds similar to the plot of the science fiction novel,

52

The Languages of Pao, you are correct. However, the author, Jack

Vance never specified exactly what any of those languages were like.

Beltös is such a language.

Before we construct a language to limit thought, we should

consider what type of culture we want. The main idea for Beltös is to

eliminate every possible means of confrontation. The culture is a

peaceful one, where no altercation, no argumentation, no

disagreement, nor even any cruel or sarcastic comments are possible

to express. This leads to the most important restriction of Beltös:

There is no negation.

Really. None.

There is no word for “no.” There is no word for “not.” There

is no word nor morpheme to express “un-” or “anti-”.

Surely, you might think, one can express opposites simply by

using the antonym of what has been expressed. If one wished to

negate: “He is tall,” then one can simply state: “He is short.” Yet,

that actually is not true. “Tall” and “short” are positive attributes of

objects; to say that a person is short is not necessarily demeaning or

pejorative or negative in any way. Similarly, the negative of “black”

is not “white,” it is “non-black”; and red or blue or any color is

equivalently negating to the attribute of black.

53

Every negative word, any concept that could be construed as

negative or diminishing or cruel, has been ruthlessly stripped from the

vocabulary. Only in the most roundabout way, using the most

inconvenient and indirect phrasing, is it possible for a speaker even to

express the faintest glimmer of disagreement or disapprobation.

I hope you, dear Reader, enjoy some of the fables that make

up the Beltös mythology.

Interlinear Gloss Key:

https://www.temenia.org/Beltos/glosses/Gloss-Key.html

Beltös Culture:

https://www.temenia.org/Beltos/Culture.html

Beltös Grammar:

https://www.temenia.org/Beltos/Grammar.html

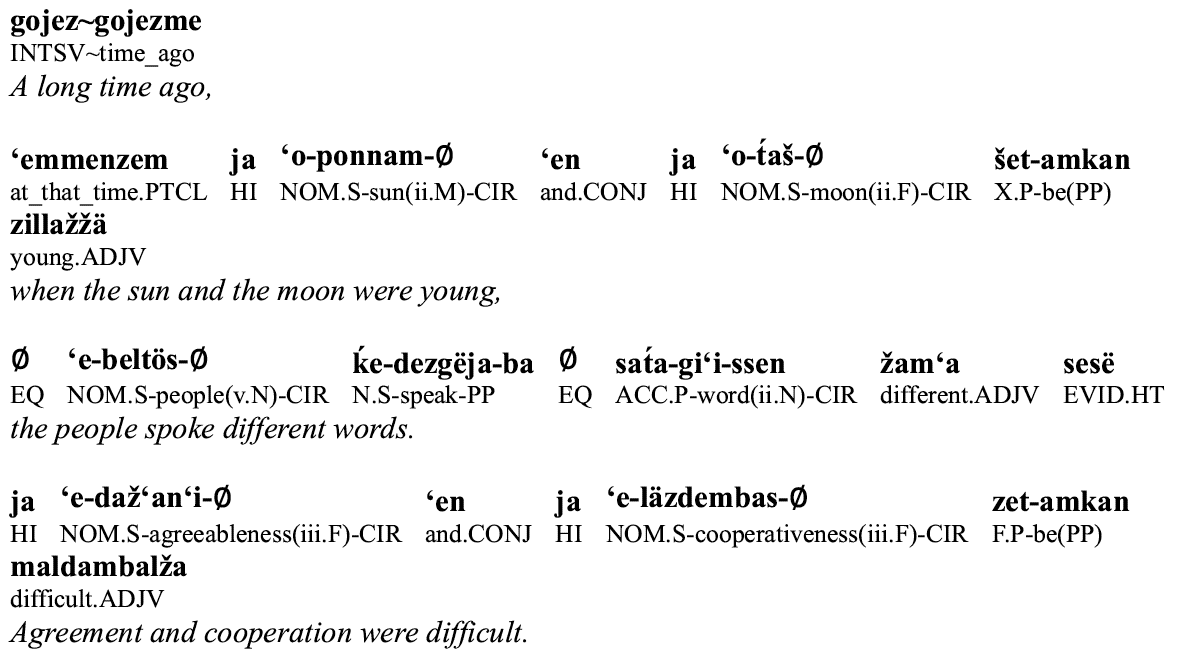

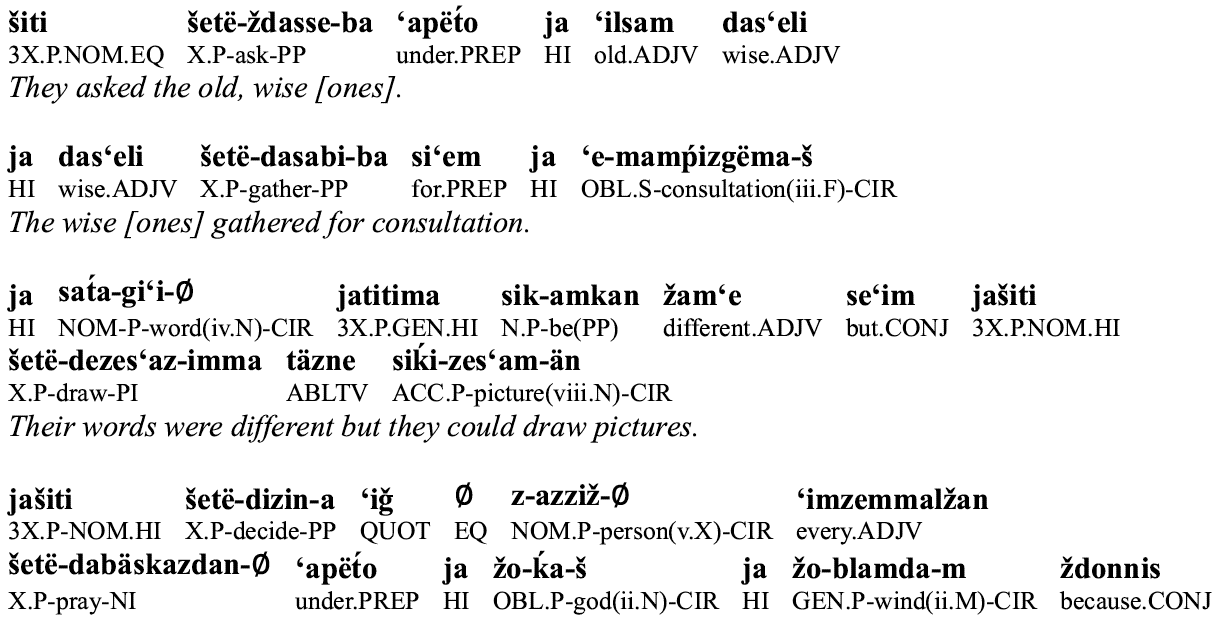

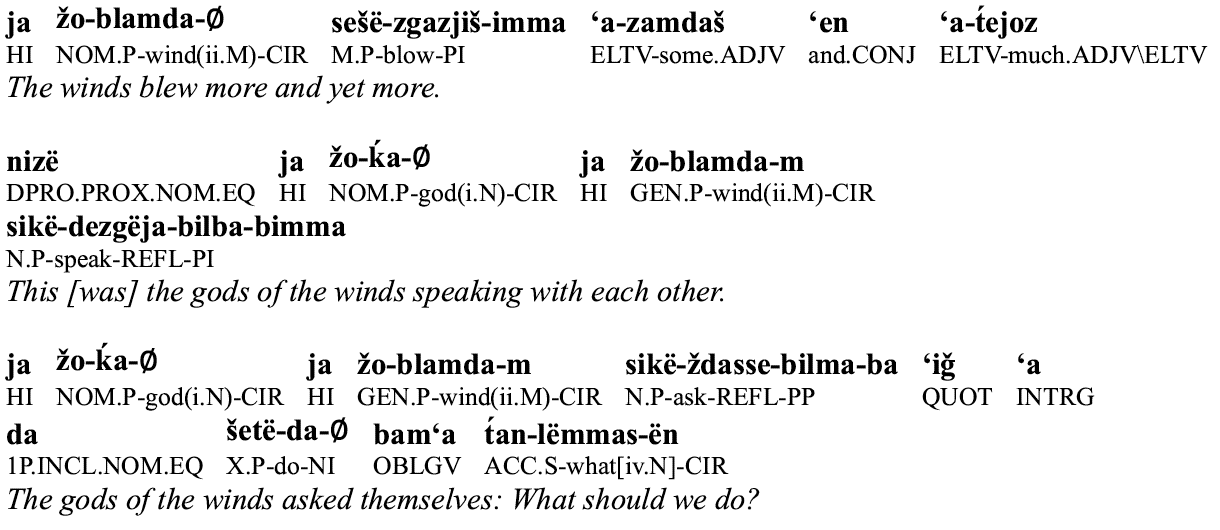

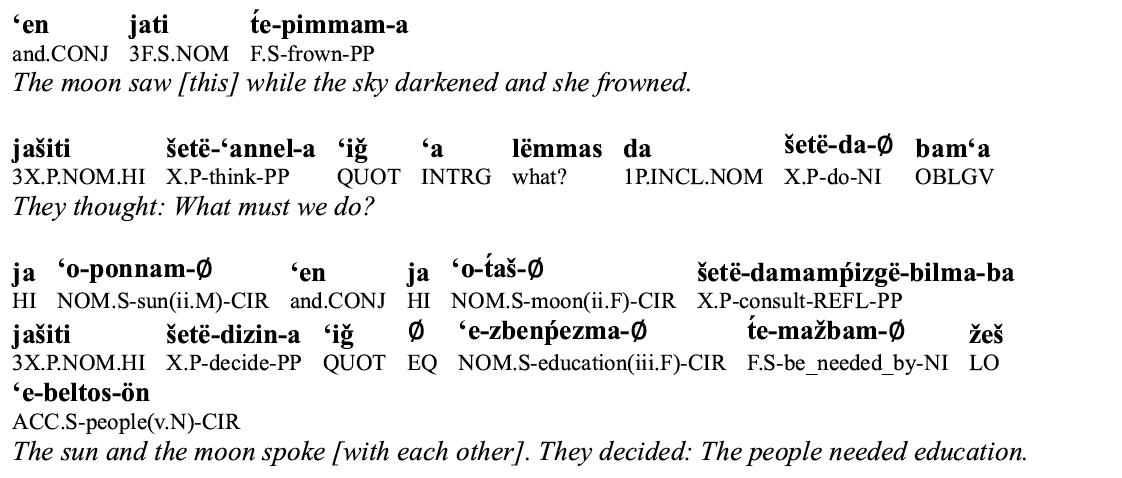

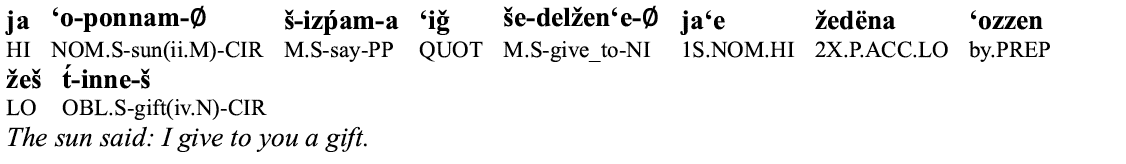

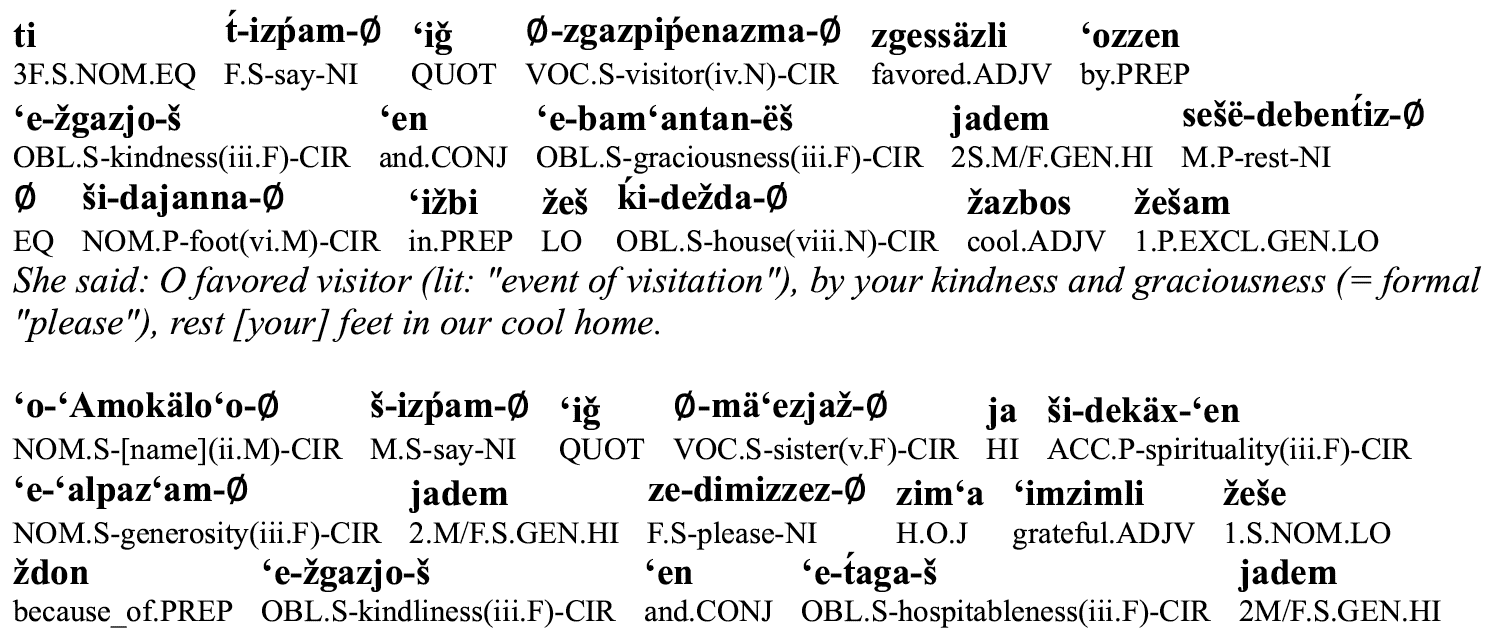

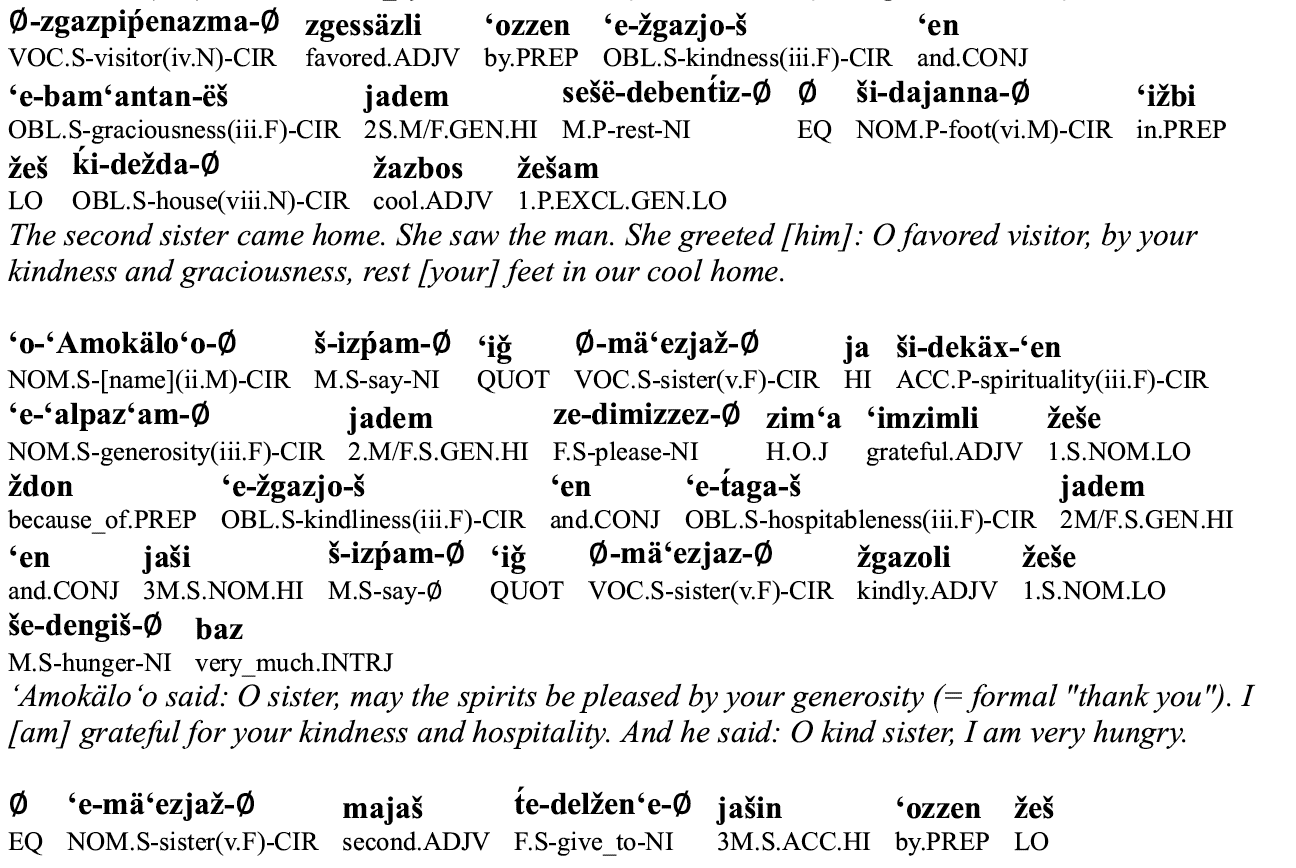

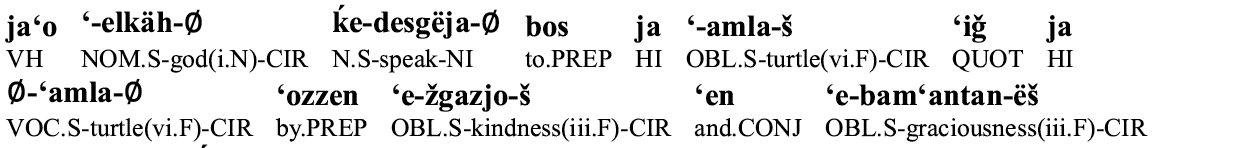

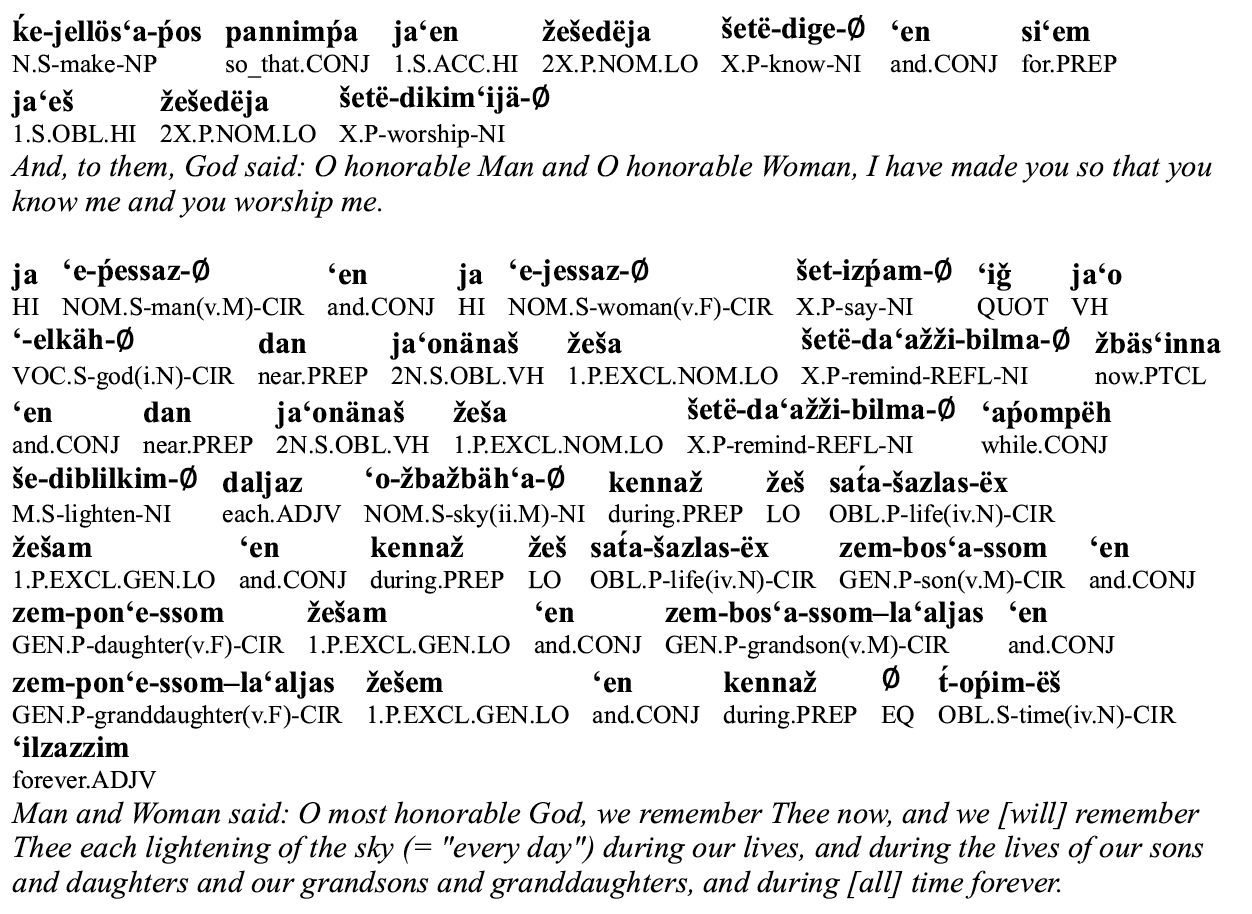

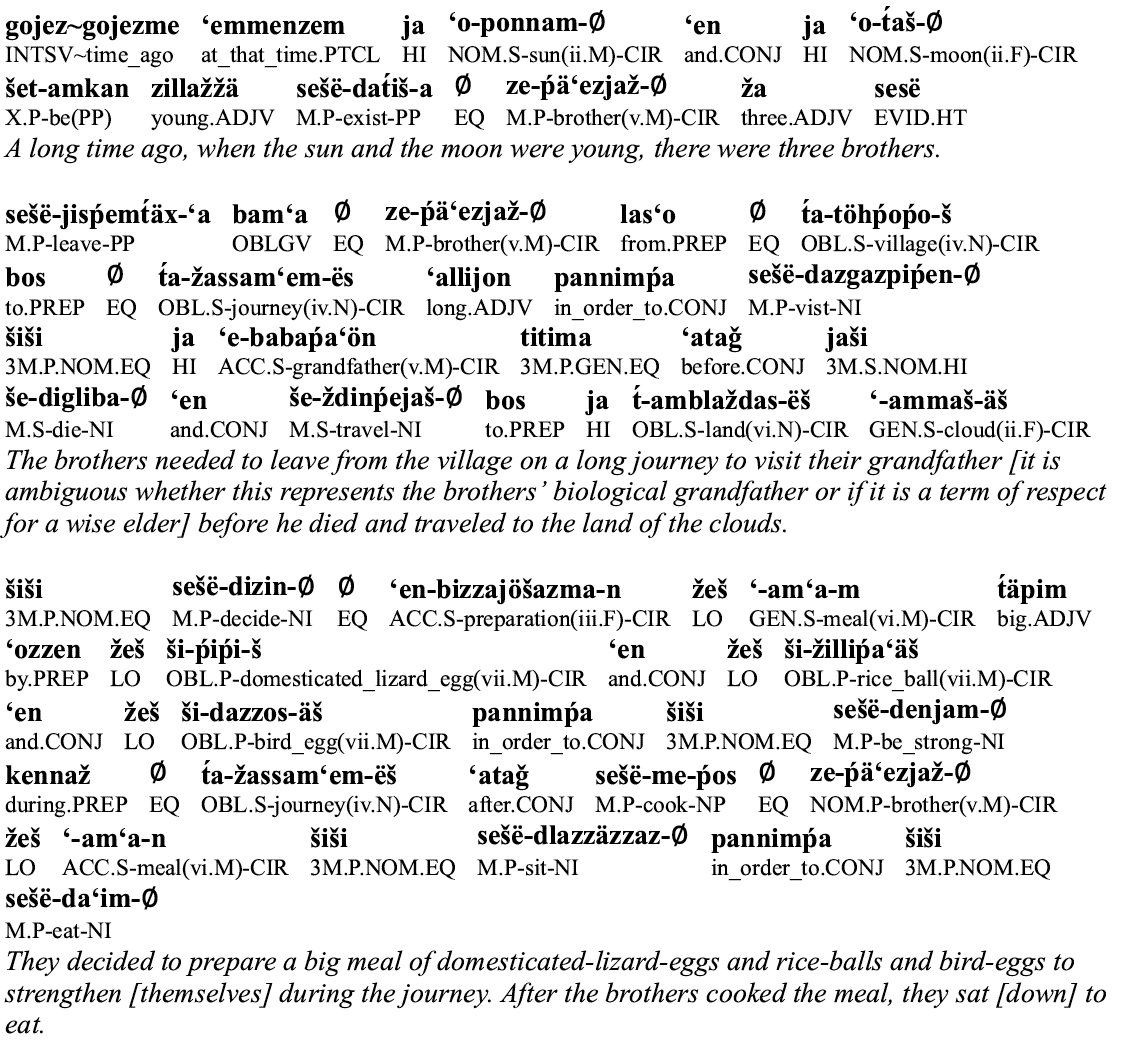

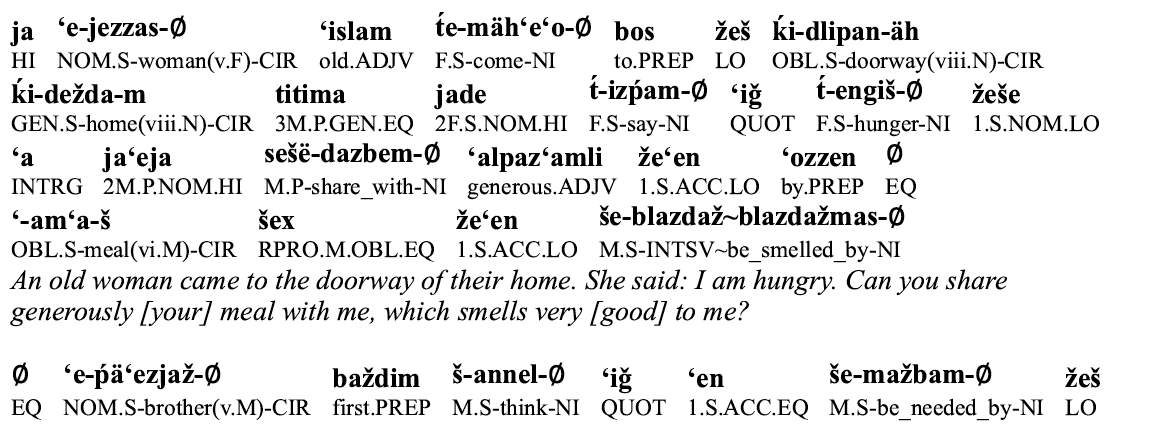

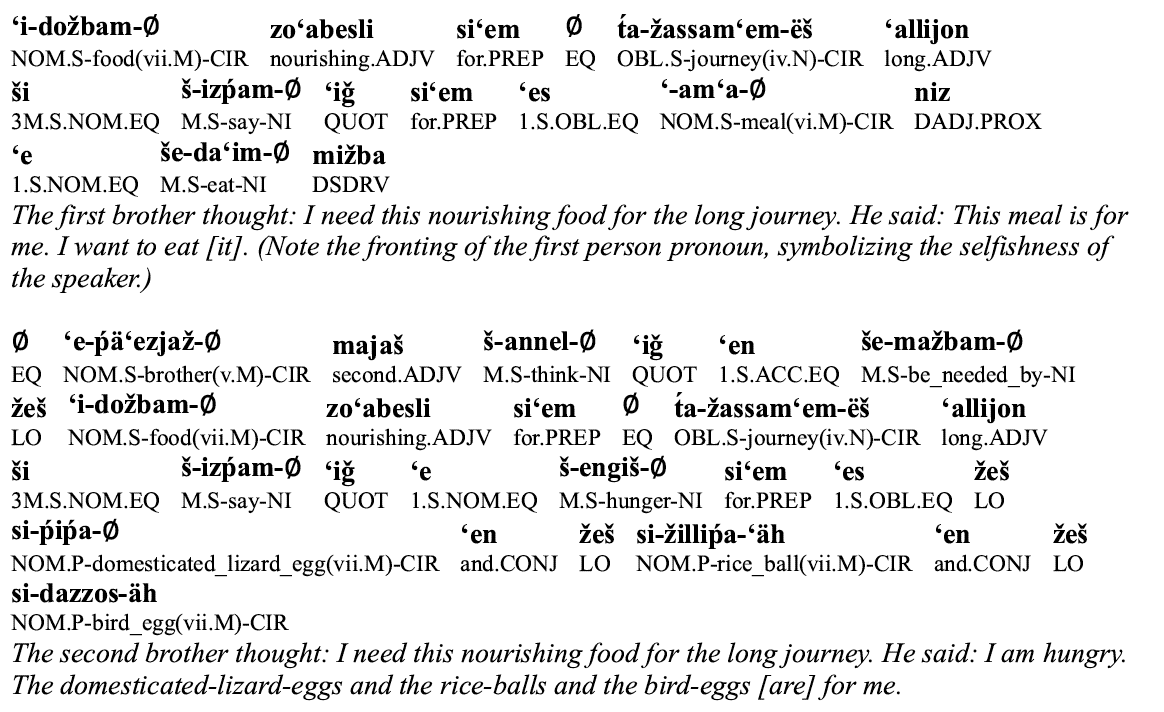

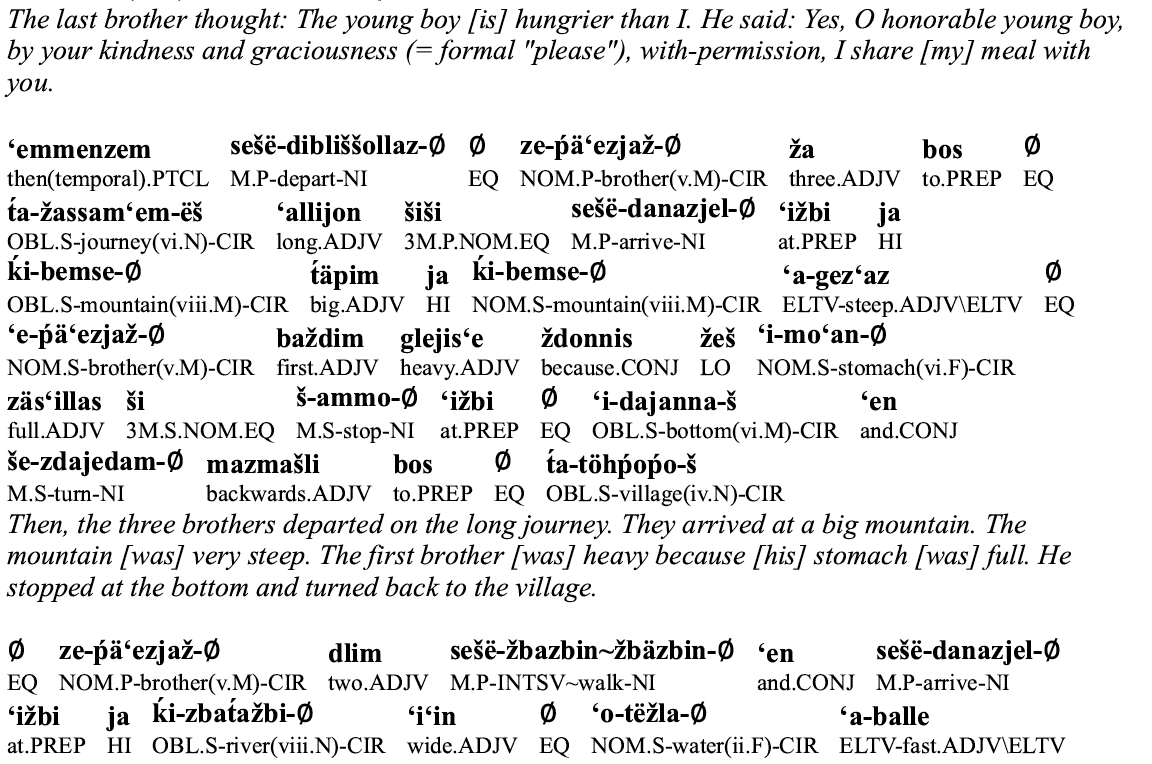

Myth 1

54

55

56

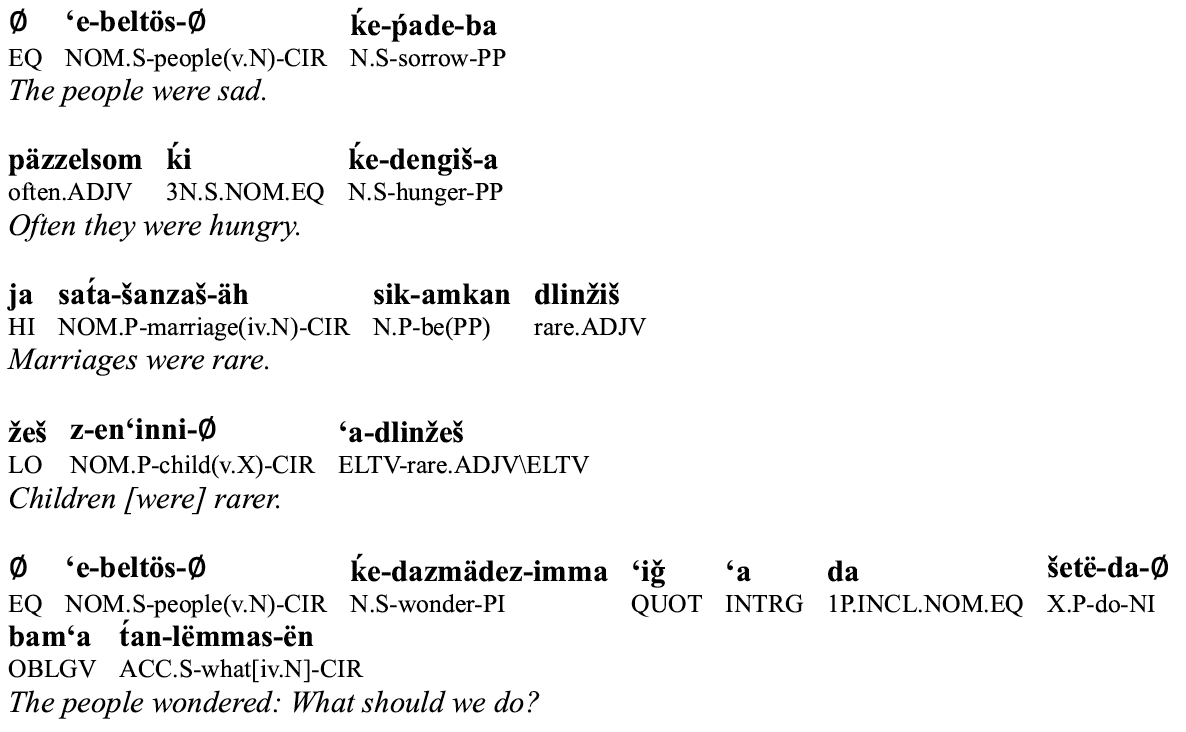

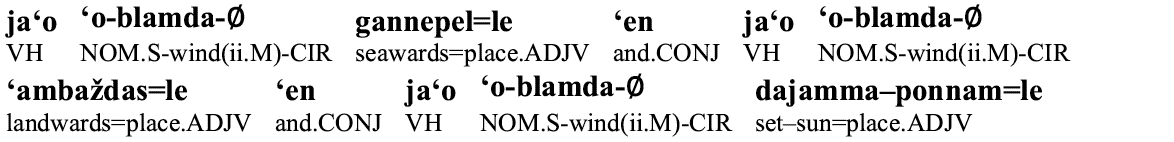

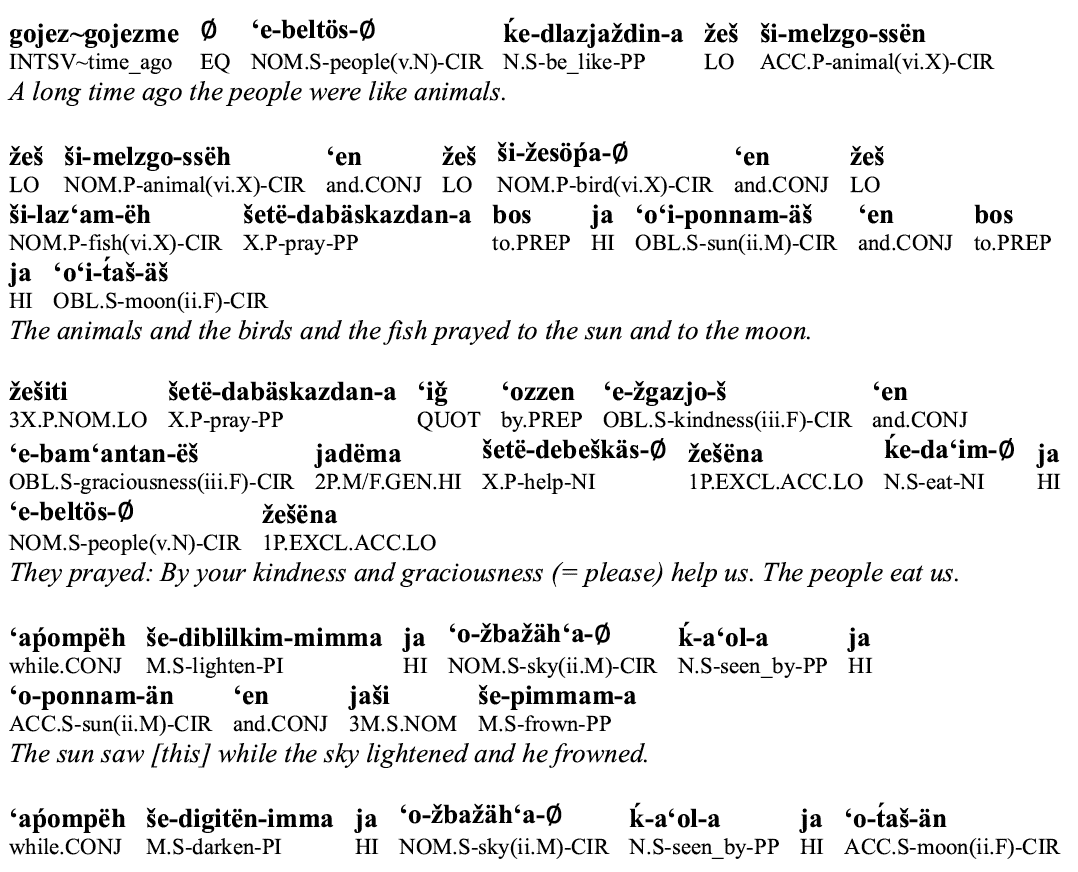

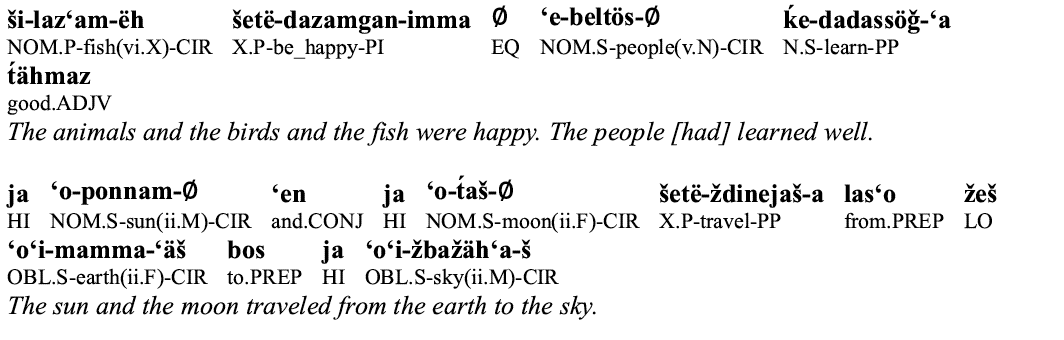

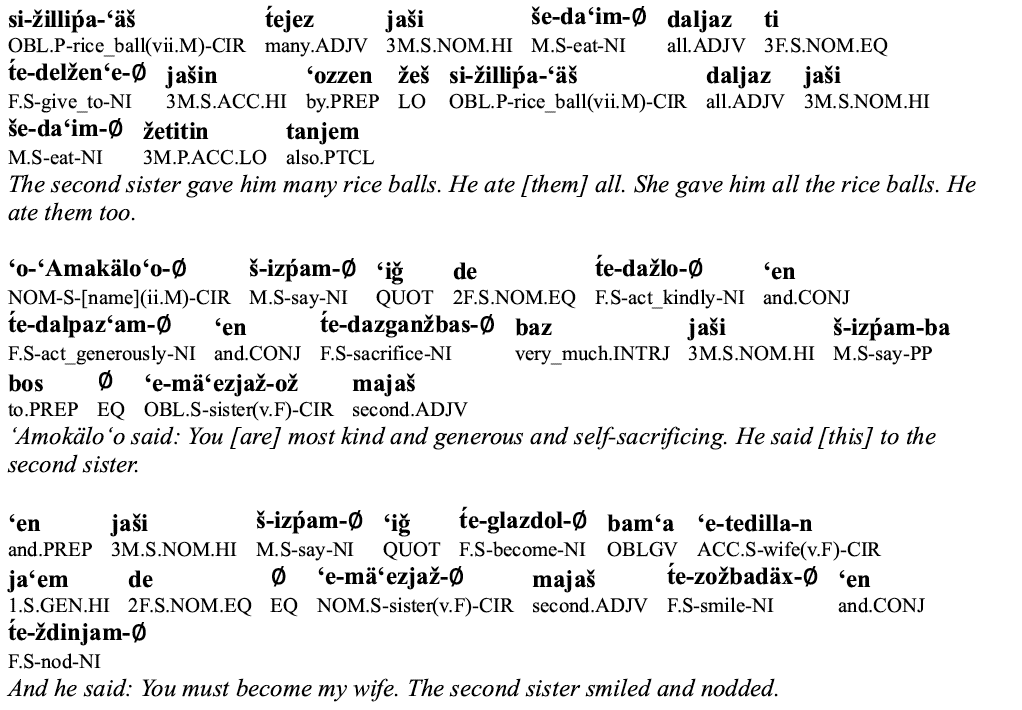

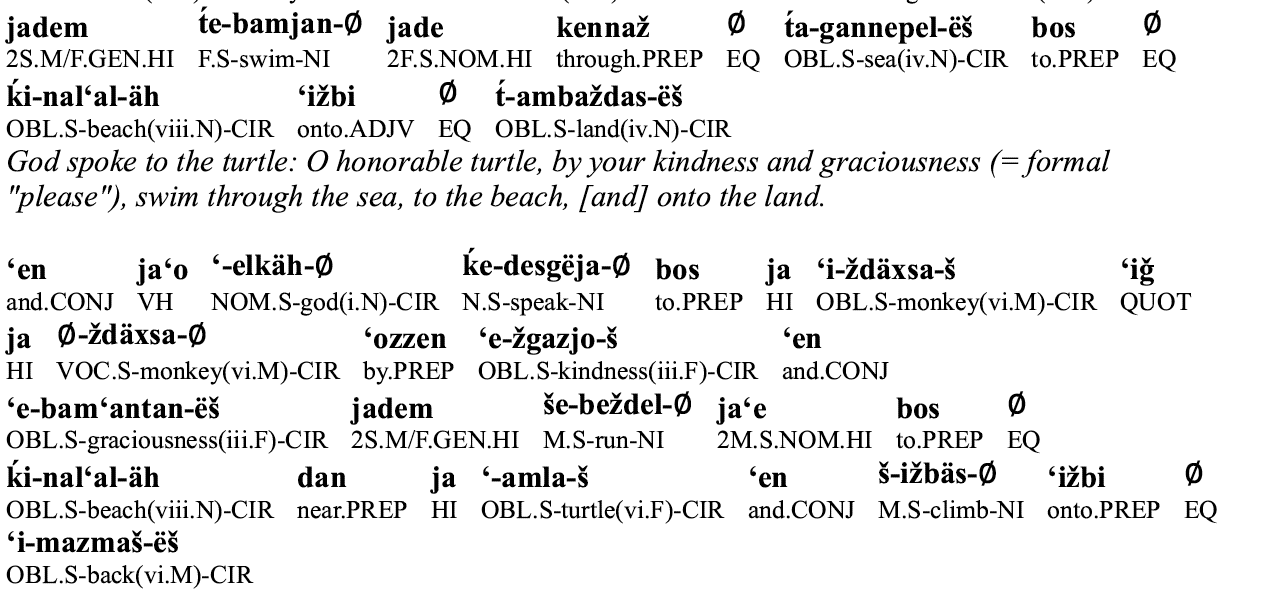

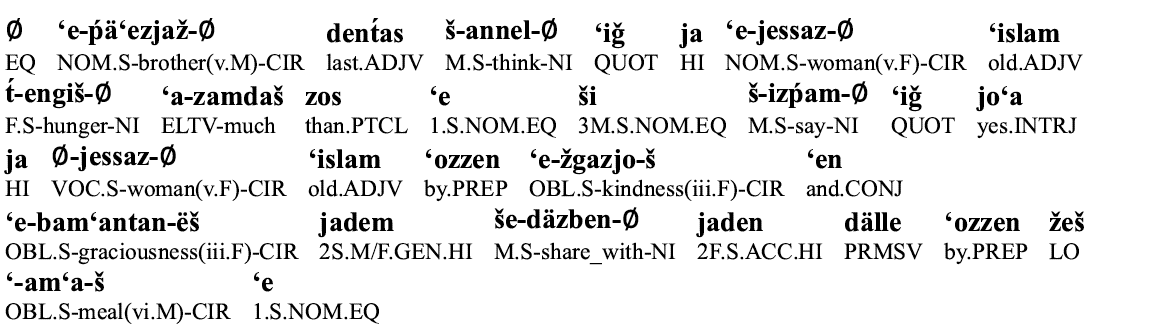

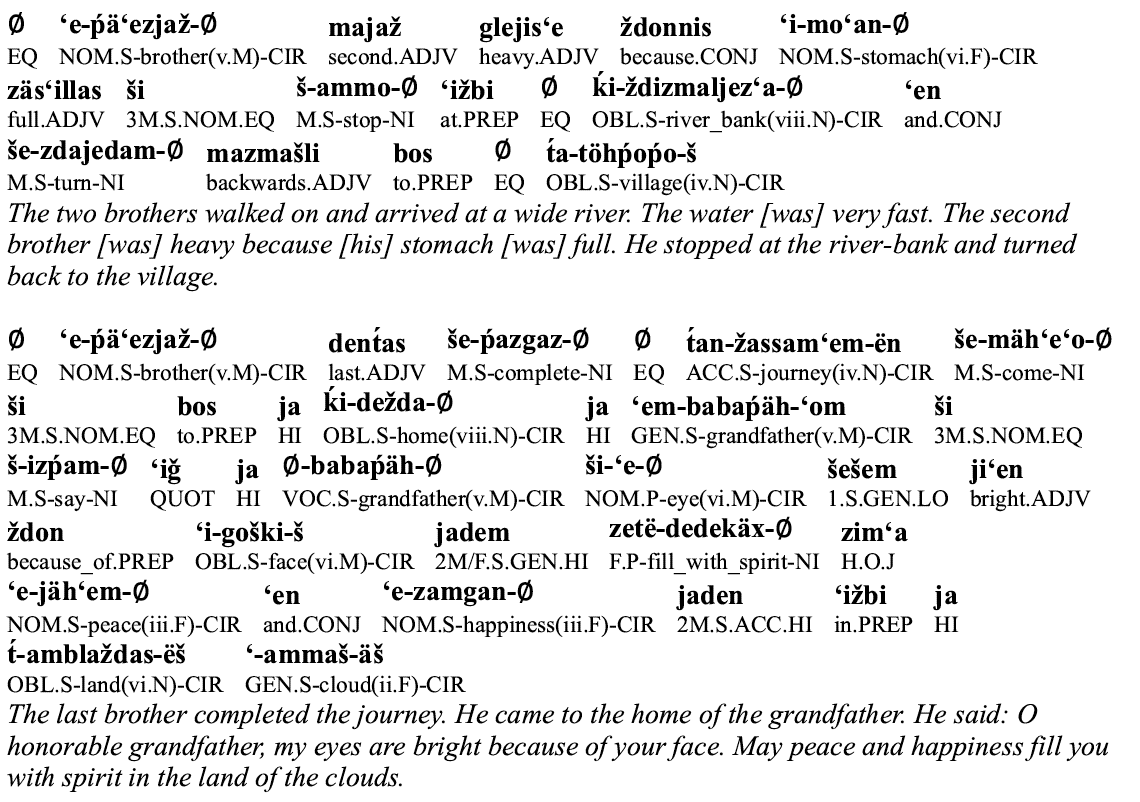

Myth 2

57

58

59

60

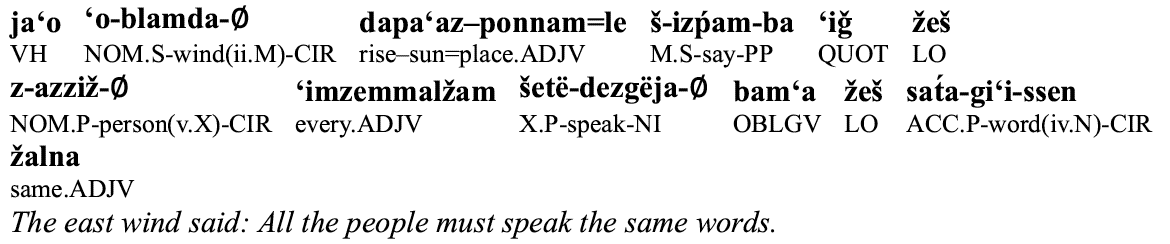

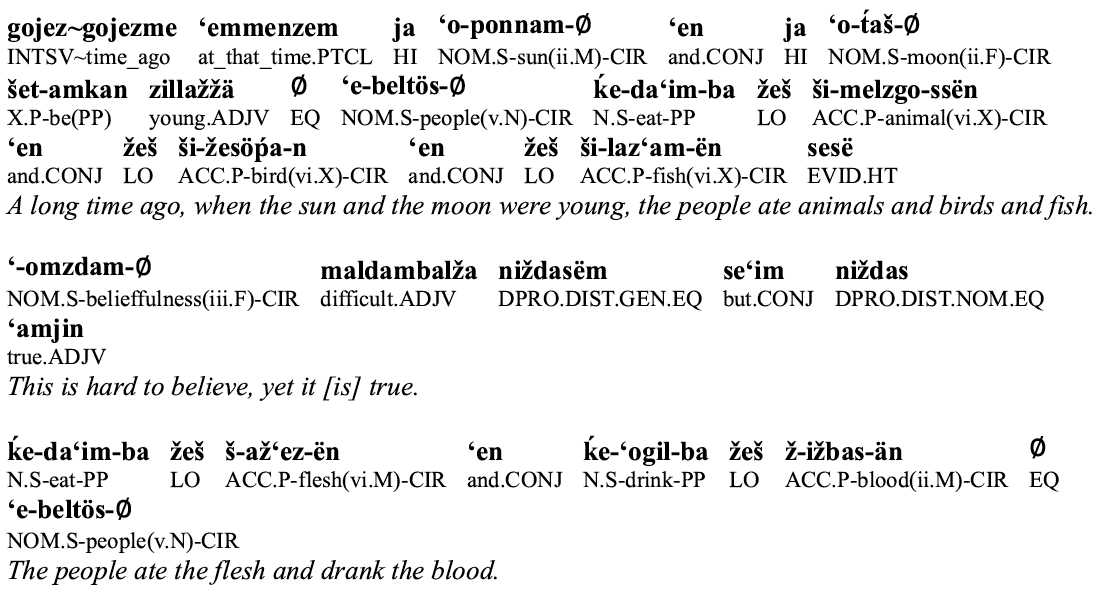

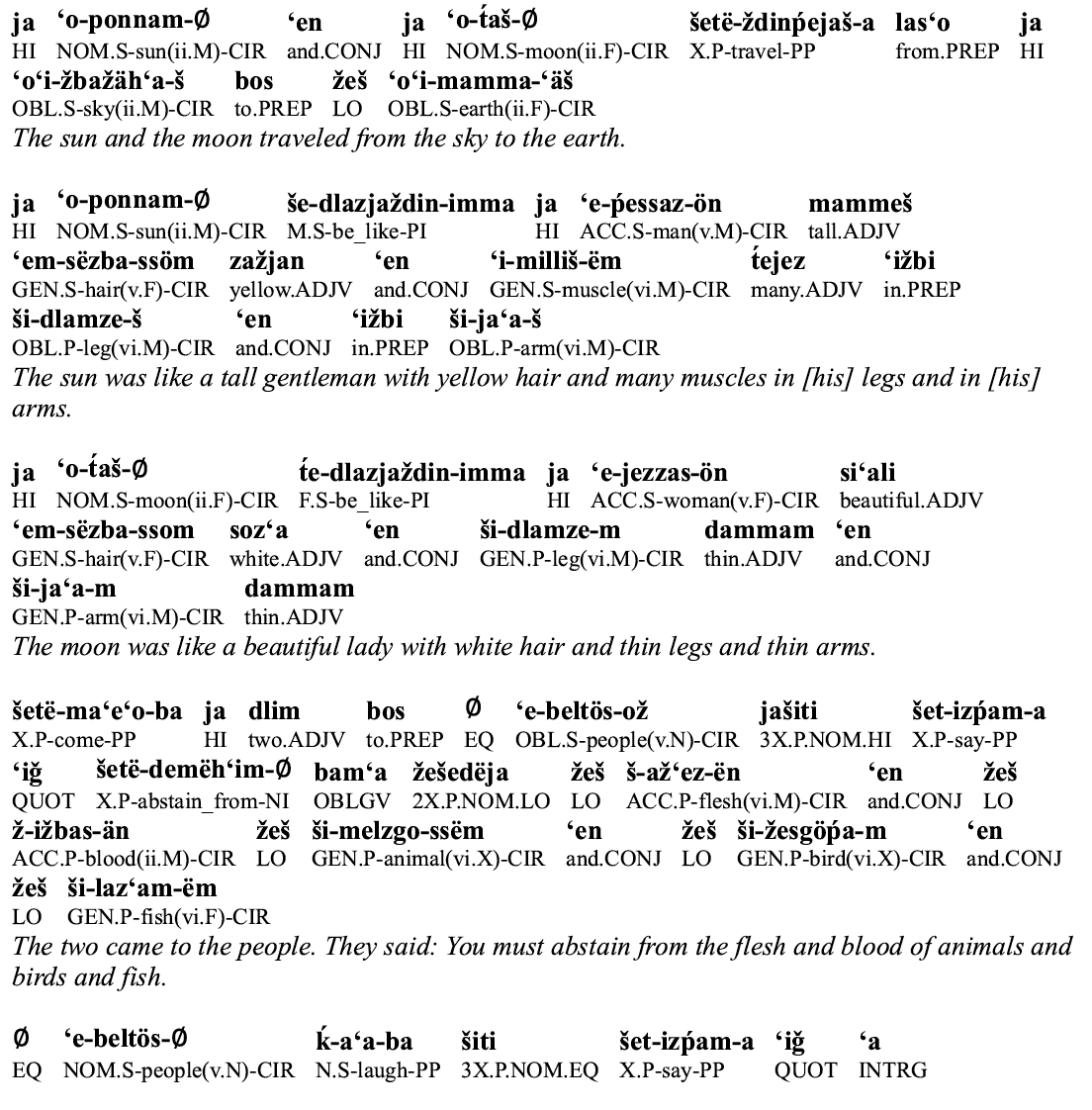

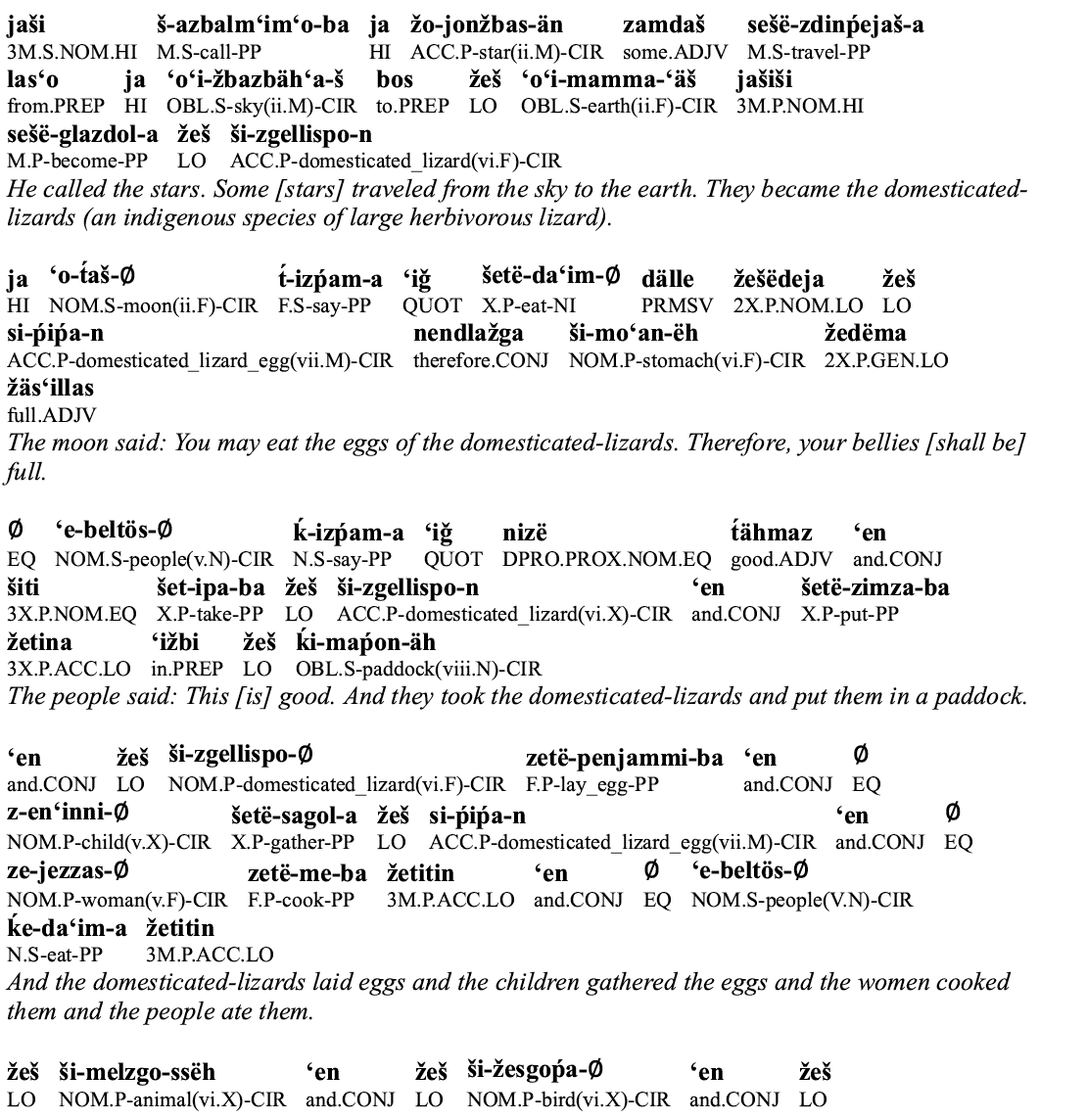

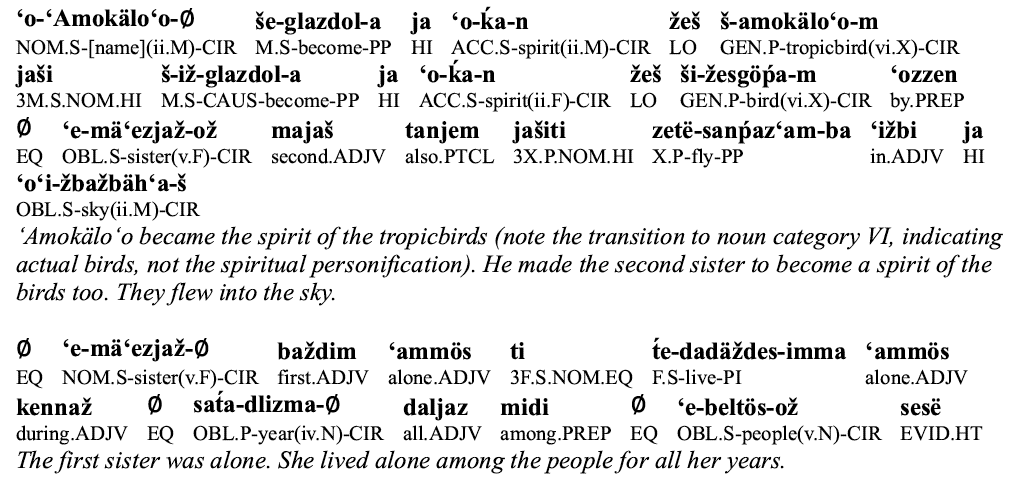

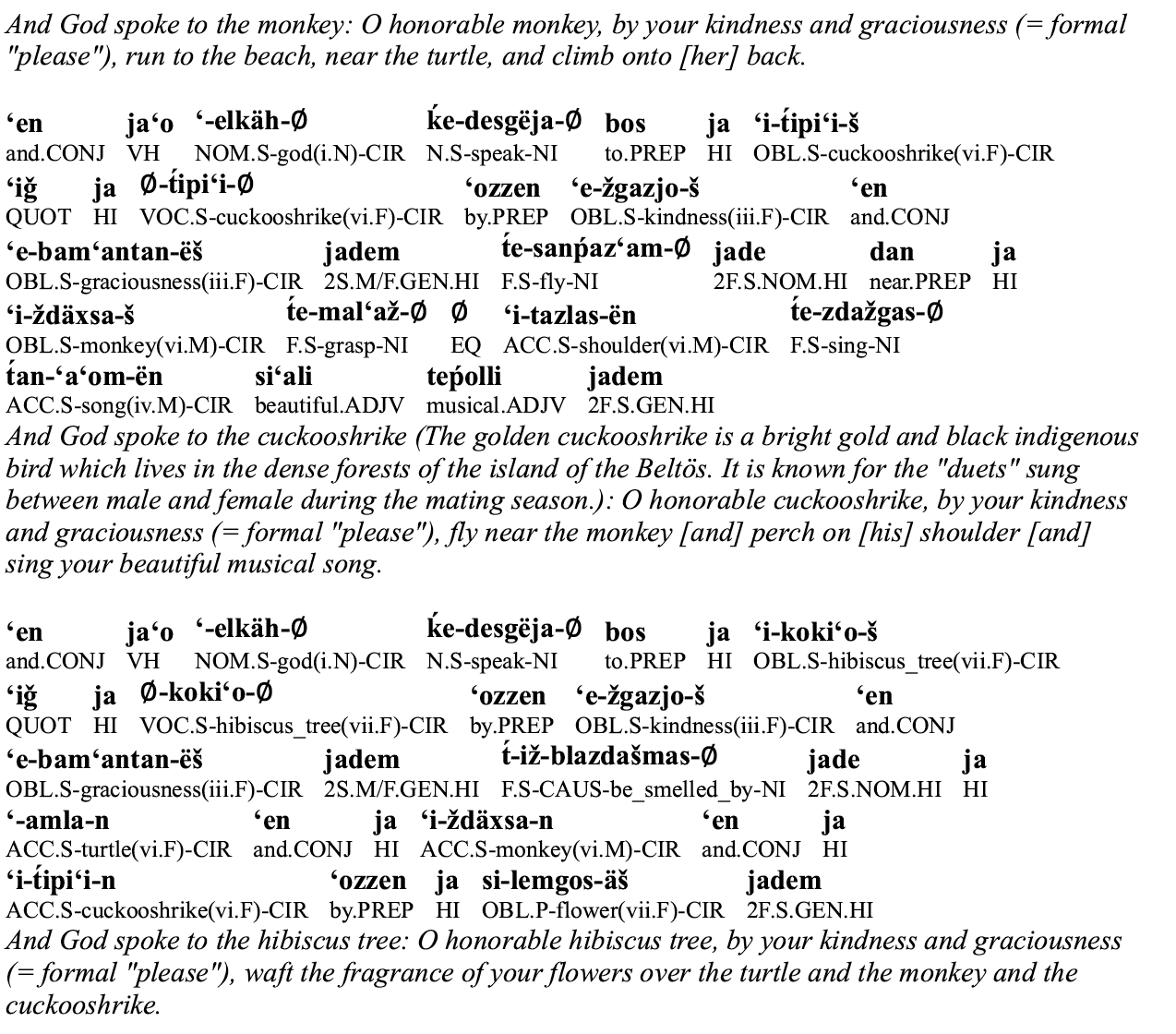

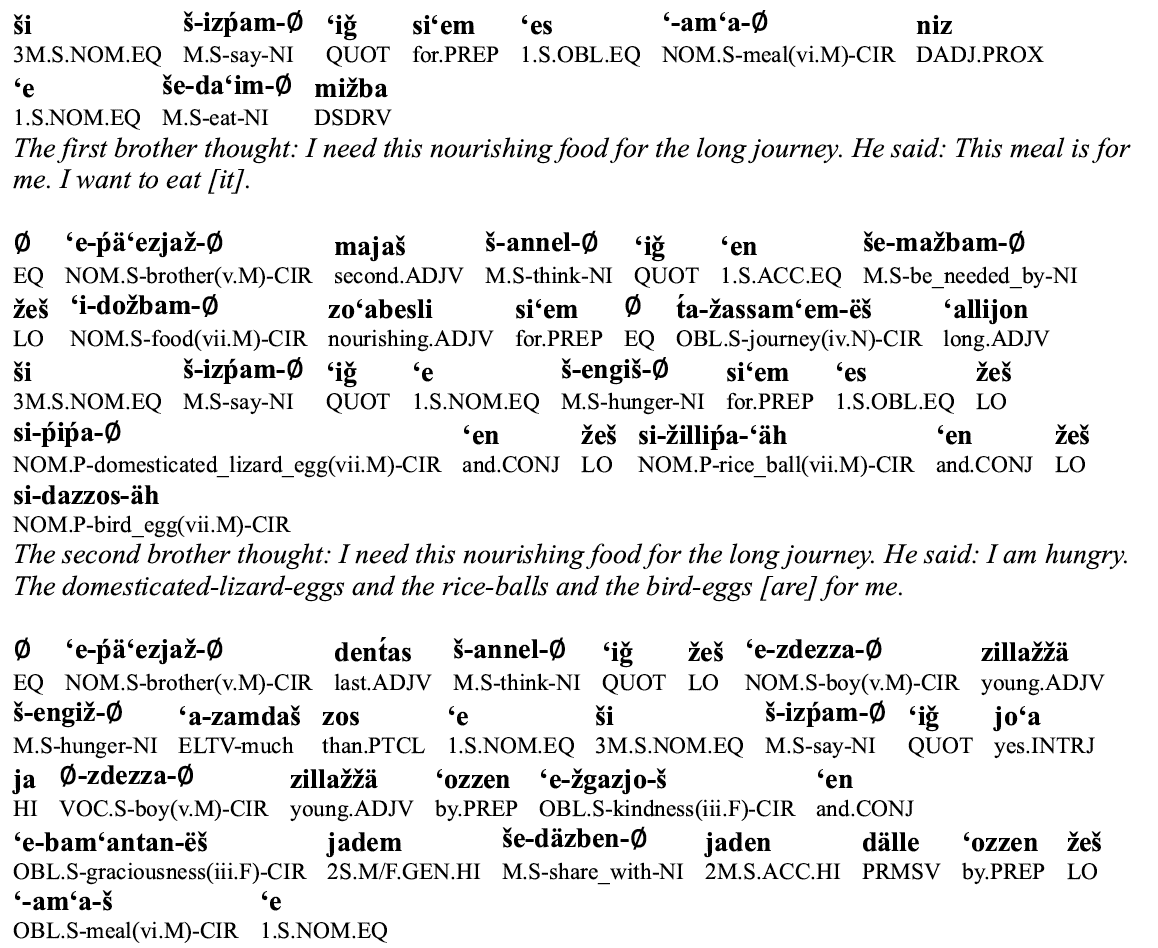

Myth 3

61

62

63

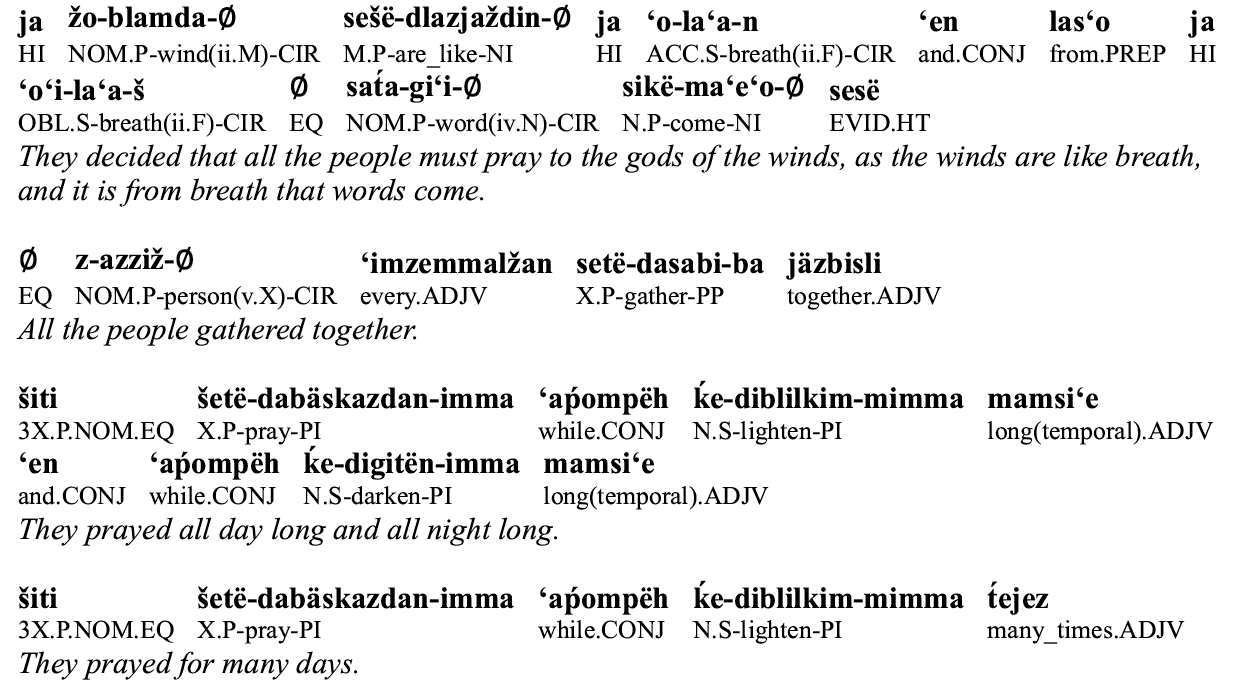

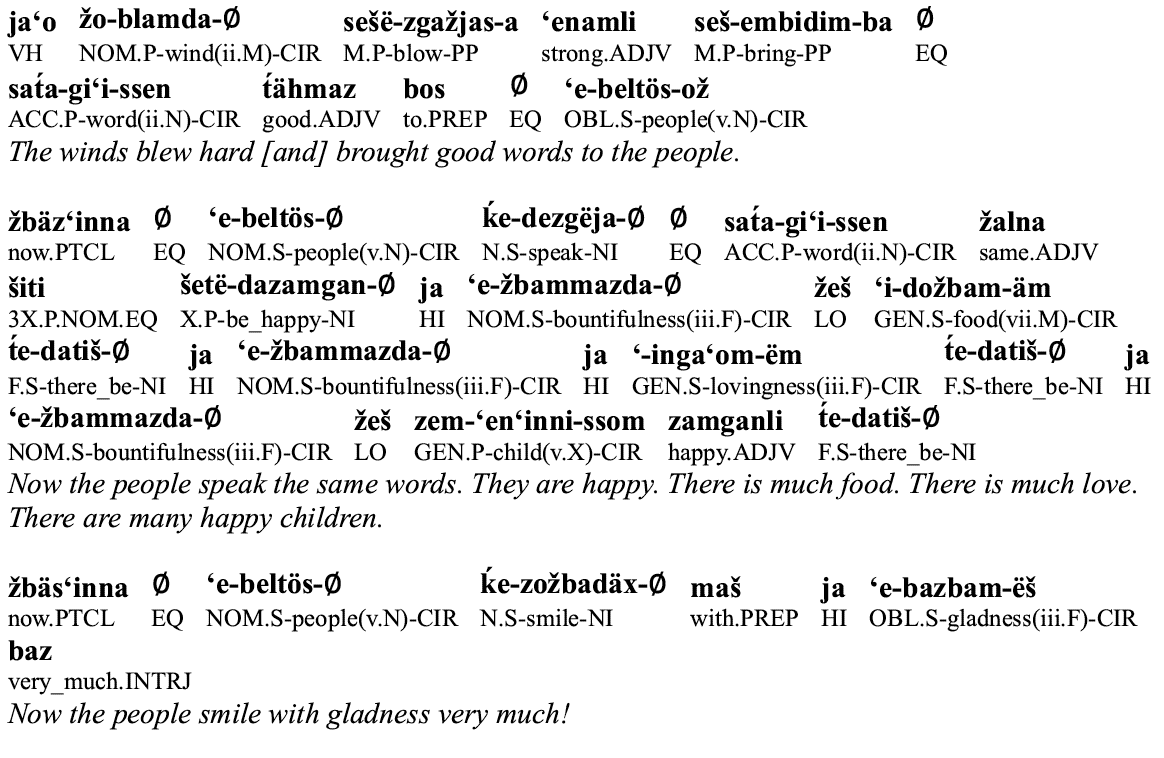

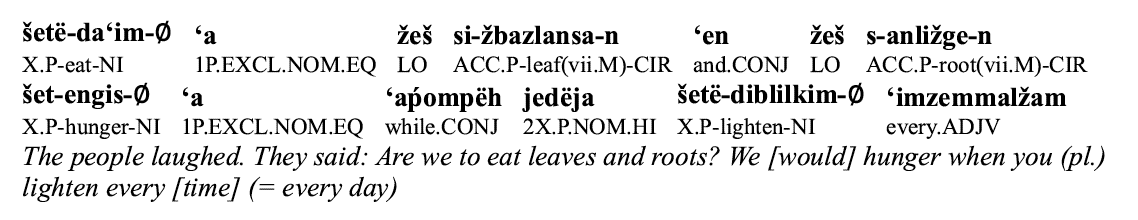

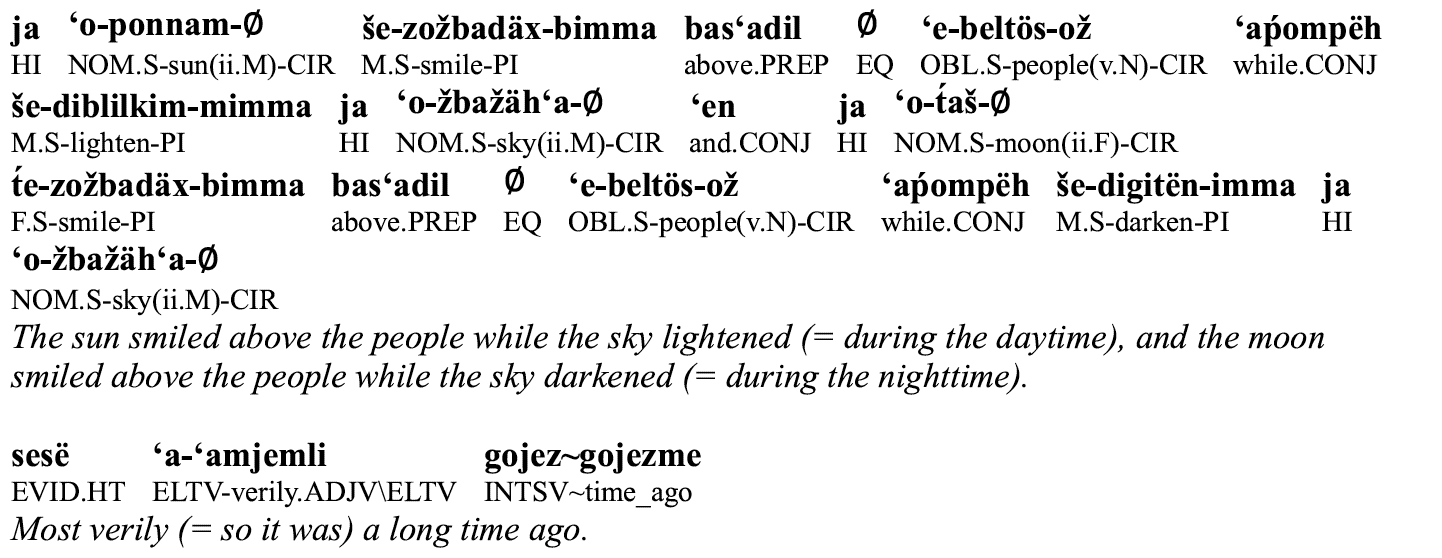

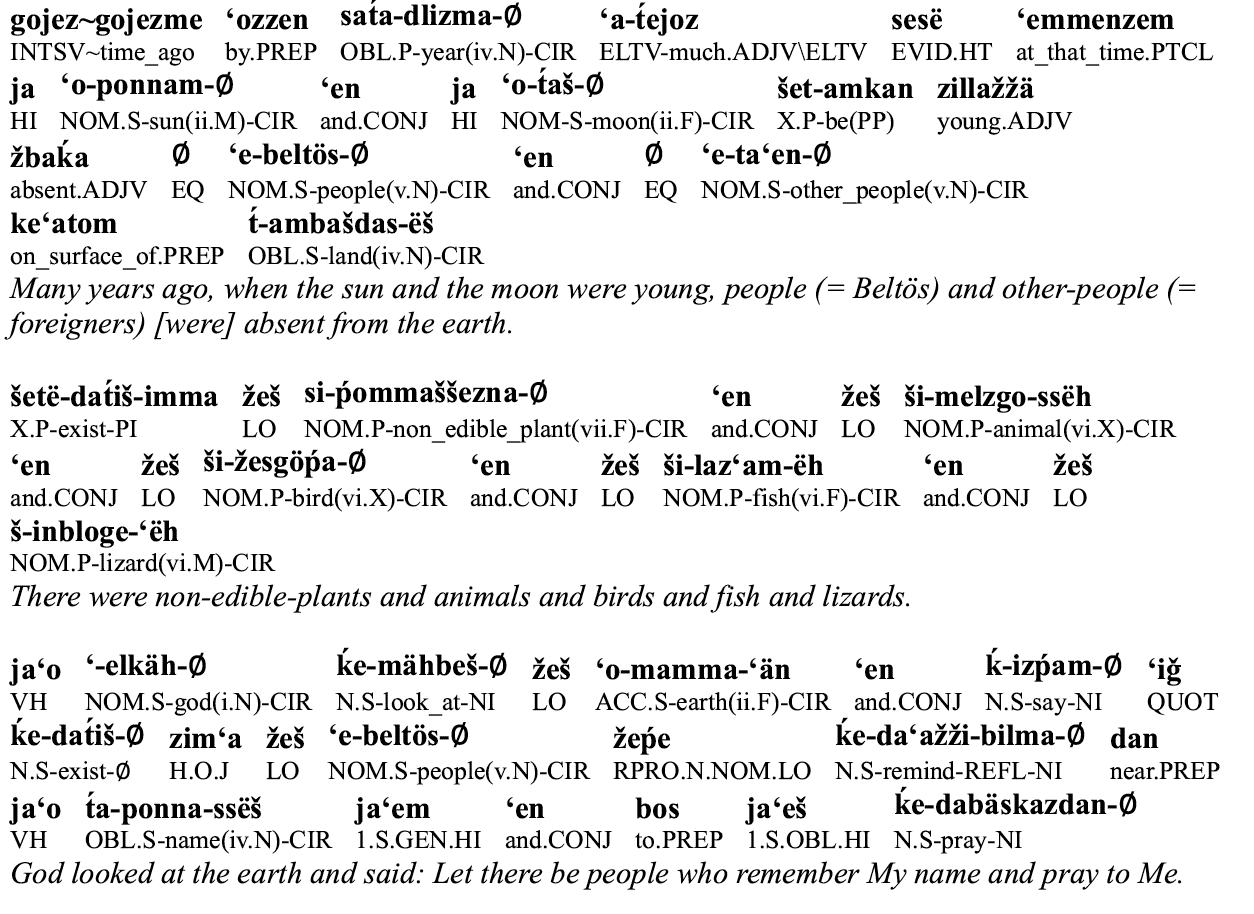

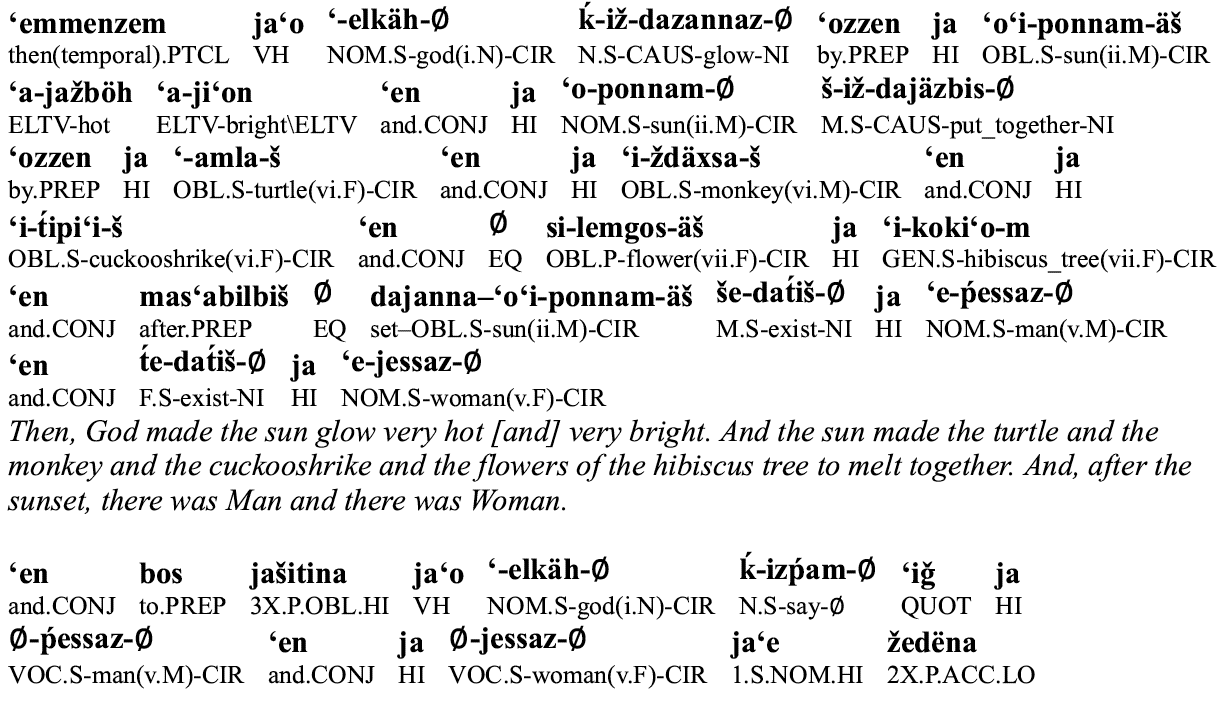

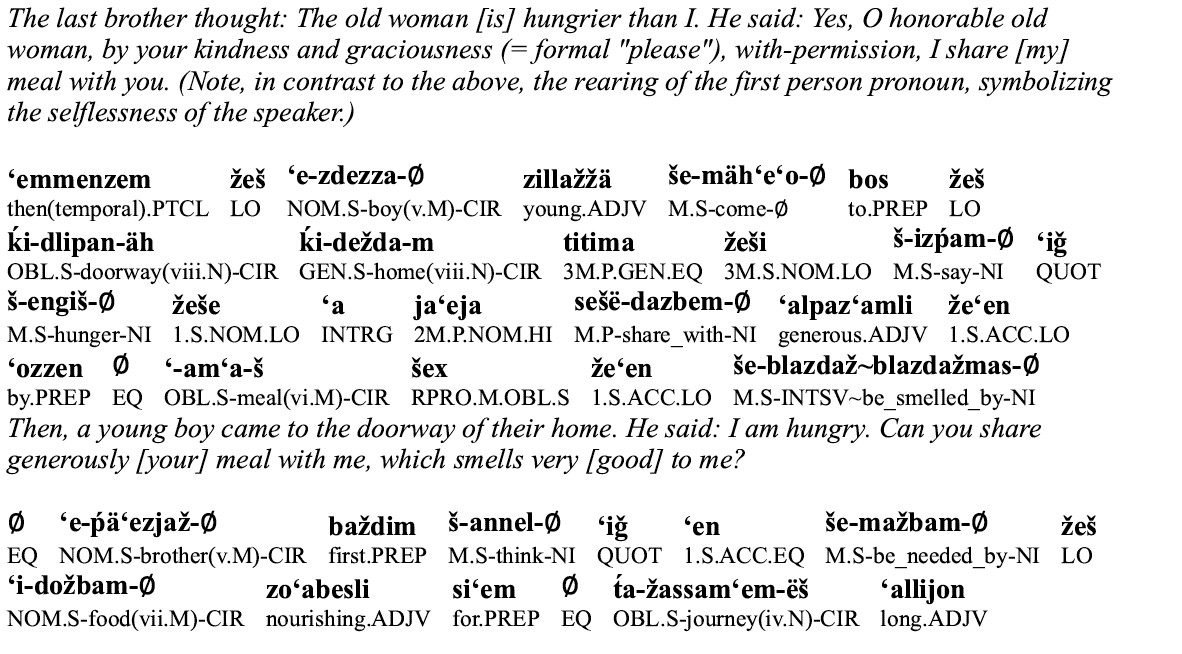

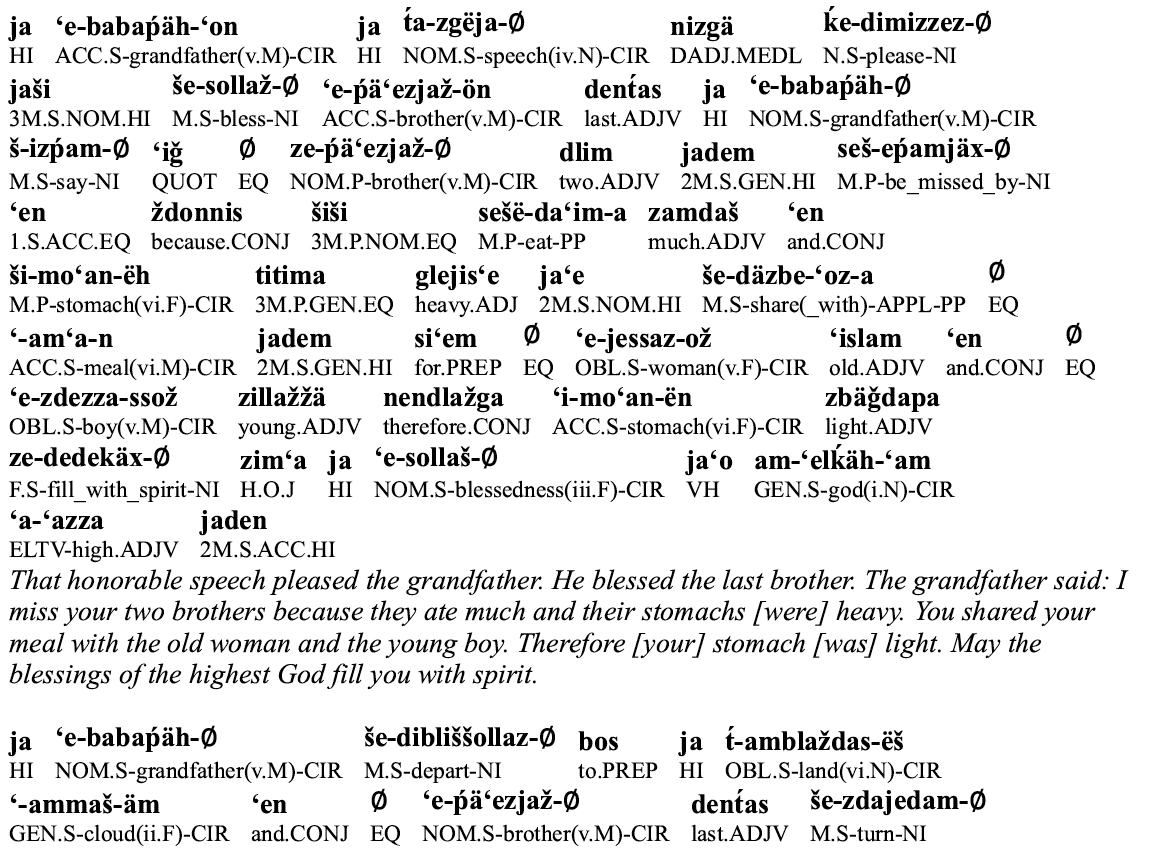

Myth 4

64

65

66

Myth 5

67

68

69

70

71

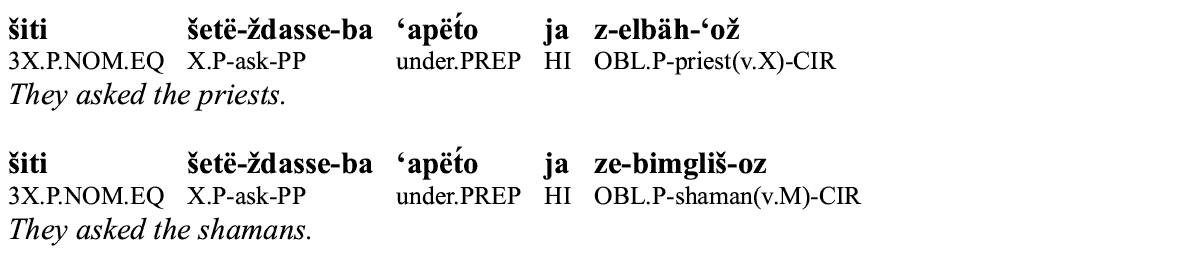

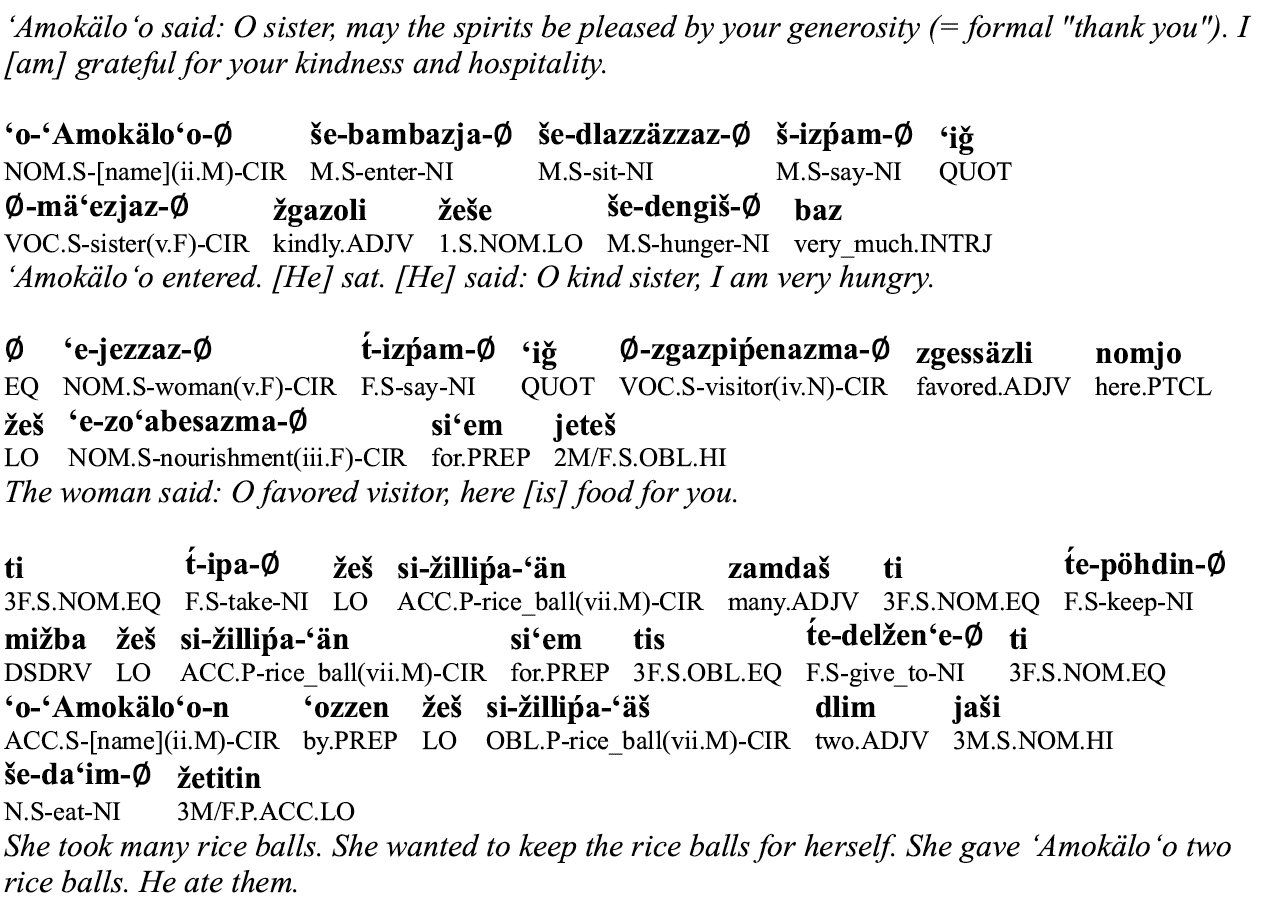

Niyolue’s Choice

Niyuer tanivana

Franc Kravos (Sudanian)

Sudanian1 is the first constructed language I’ve made,

spoken by the Sudanian nation. The idea was first conceived

when I was in fourth grade. It was then too that I created my

first conworld called Sudania, a supercontinent in an alternate

reality containing of Australia, Madagascar, South Asian

archipelago, New Zealand, Oceania and a part of Antarctica.

The main idea is: what if humans had to share their world with

another intelligent life form? And that life form is the Sudanian

species. They aren’t humans but are humanoid. As a species

they are peaceful, connected with nature, freedom loving and

highly intelligent. After I designed the continent and its native

species, I named its places too. Then, I lost interest until high

school, when I made the phonology and phonotactics of

Sudanian out of those place names. It has now been three years

since I made the actual language.

The language itself has a writing system—an abugida.

However, as of this time, I still have not devised a way of

writing it on the computer. Therefore, what I present here is

the latinization.

1(This language can also be called Sudanese, a derivation from the Italian word for south.

To avoid ambiguity regarding the demonym Sudanese, this article uses the name Sudanian

throughout.)

72

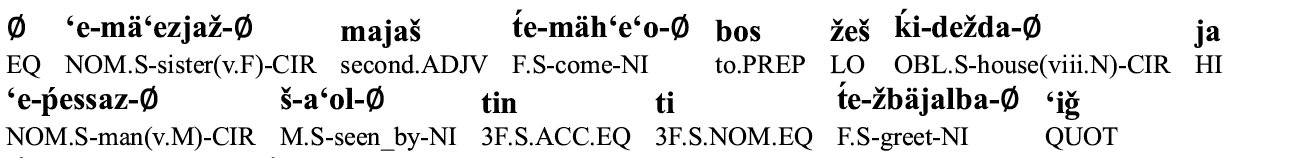

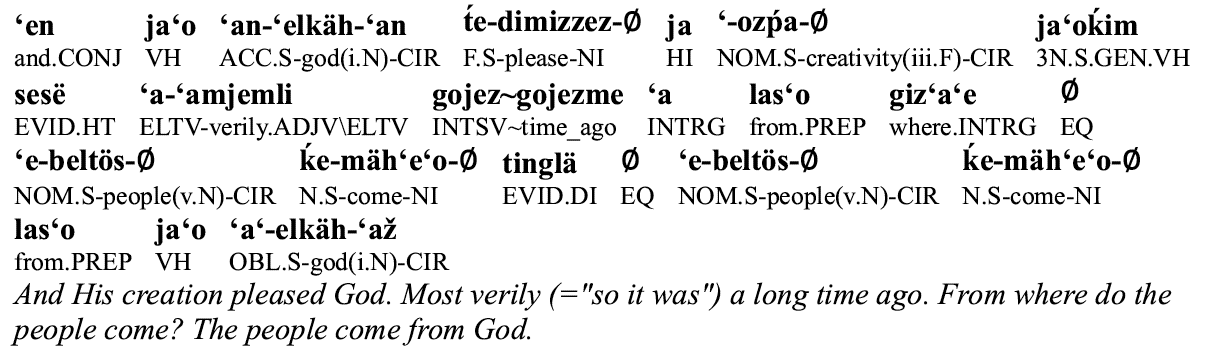

Labial

Coronal

Velar

Glottal

Stops

Fricatives

Nasals

Approximants

P[p]

F[f]

M[m]/V[v]

T[t]/D[d] G[g]/K[k]

S[s]/Z[z]

N[n]

R[ɾ]/RR[r]

Y[j]

H[h]

Front Central Back

U[u]

I[i]

E[e]

A[a]

Close

Mid

Open

The letter X is pronounced like [ks]. A doubled

consonant reprensents gemination (NN, YY, ZZ, SS). There are

only two exceptions to this. The first is RR which is

pronounced like postalveolar trill. The second is XX which is

pronounced like [ksks]. Sudanian is a stress language and

the first vowel of the word is always stressed unless the vowel

is doubled. If we double a vowel like this UU, AA, EE, II means

that the stress is on that vowel e.g. DUVAA. When there is an

apostrophe in between two vowels that means that you make

a small break and then say the vowel again e.g. GA’AX.

Sudanian is a SOV (subject, object, verb) language and

adjectives come after a word.

The short story below has been written in English and

then it has been translated into Sudanian. It talks about a

planet that has been invaded by an alien species, which has

73

been destroying it and enslaving the native population. We

follow the story around queen Niyolue (Niyuer in Sudanian)

who is trying her best to help her people.

The story, an important one for the Sudanian nation,

demonstrates their worry that humans will destroy their

beautiful home. In this alternate reality, humans and the

Sudanian try to have good relations with each other, but the

humans often disrespect that bond. Queen Niyolue represents

the nation suffocating in worry, the Katherines represent

humans, and the nation represents the Sudanian secret wish of