To What Extent do Constructed Languages Serve an

Important Purpose in Media?

Author: Eva Caston Bell

MS Date: 01-14-2022

FL Date: 05-01-2022

FL Number: FL-000080-00

Citation: Bell, Eva Caston. 2022. «To What Extent do

Constructed Languages Serve an Important

Purpose in Media?.» FL-000080-00, Fiat

Lingua,

2022.

Copyright: © 2022 Eva Caston Bell. This work is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

Fiat Lingua is produced and maintained by the Language Creation Society (LCS). For more information

about the LCS, visit http://www.conlang.org/

To What Extent do Constructed Languages Serve an Important Purpose in Media?

Eva Caston Bell

Abstract

This research project explored the extent

to which Constructed Languages serve an

important purpose in media. The study focused largely around the combination of prior

research conducted by language constructors and the experiences of those who consume

constructed languages within the types of media they exist in, such as film, television, and

literature. These experiences were collected through primary research in the form of a

survey which compiled the sentiments of over 200 conlang enthusiasts, and covered the

their varying

questions their own perspectives on learning a constructed language,

effectiveness dependent on the medium they existed in, and the constructed languages with

which they were most familiar, in order to gauge the way in which constructed languages

have the most extensive effects on those the reader or audience. Through the combination

of these differing perspectives, the project was able to investigate the prevailing function that

constructed languages serve within pop culture and media, and how this role has differed

since the establishment of online communities in the field. The most popular trend offered by

both conlangers and their fans was that constructed languages offer a sense of community

and collaboration between those who would not otherwise associate, while also providing

academic value to fiction and pop culture, a sentiment established more by those that

construct languages, rather than those that receive them. This therefore demonstrated the

role of the constructed language as a unifying presence of media, both commercial and

social, and a mode of expression for everyone involved in or affected by their presence.

It

investigate the purpose of constructed languages in the media that they

This project will

exist within, whether this be literature or film, television or radio; in almost every form of

entertainment someone, somewhere, has crafted a language for its consumers.

is

that boundaries are immediately established when discussing constructed

important

languages, as the term serves a variety of purposes. To achieve a cohesive response the

term ‘constructed language’ will be defined as a language that has been purposefully and

consciously created for a work of

fictional media, with the more common contraction

‘conlang’ also being used in reference. It is the centering of this project around the role of

conlangs in media that almost entirely eradicates commercial or political languages such as

Flamenhof’s ‘Esperanto’ from the study, as although they do serve important purposes –

perhaps, realistically speaking, more important than fictional conlangs – the effects they have

and those that are affected by them do not fall into the desired group of exploration. Instead,

this project will explore the rich culture of conlangers and the fans of their languages, and

how constructed languages have impacted their lives and the media they consume. This

exploration will be done through both a review of the research to date which has focused on

conlangs and the opinions of conlangers and conlang fans themselves. The relevance of this

research is greater today than ever before as online communities have experienced an

enormous surge in numbers in recent years, perhaps most recently in the wake of the

COVID-19 pandemic as many other forms of communication were cut off. These online

communities have allowed the growth of close-knit groups of like minded individuals with a

shared passion for a niche topic, one of which is language creation. The exploration into fan

culture is also especially important today as social media platforms such as Twitter, Tumblr

and Reddit are dominated by huge hoards of fan groups, or, ‘fandoms’ who connect with

each other through a shared love of a form of entertainment or media. Some of the most

prominent fandoms on these sites are those centred around fantasy series’ or literature,

such as ‘Game of Thrones’, ‘The Lord of the Rings’, or ‘The 100’, whose reddit platforms

have 2 million, 1 million, and 100,000 members, respectively. In almost all of the most

popular fantasy series, sagas and franchises, a common factor is evident: a constructed

language. While a fairly substantial amount of research has been conducted on the creation

of conlangs themselves, there has been limited research on the effects they have on the

people who consume the media they are present within, providing a clear path for the

investigation of this project. The majority of previous research has been conducted by

conlangers (those who construct languages) such as David J Peterson, Mark Rosenfelder,

and the Language Creation Society, although there is constant discourse and discussion in

online forums about the methods and pathways of constructing languages. However, this

increased popularity and discussion of conlangs has also led to increased scrutiny, with

conlanger David Peterson stating that “in order to meet the expectations of audiences

everywhere, we have to raise the bar for languages created for any purpose” (Peterson,

2015). Peterson provides a valuable insight into the changing nature of conlangs; what was

once a hobby done by individuals in their bedrooms has turned into an international

phenomenon that has changed the fantasy genre for good. A once mocked artform is now

the centre of thousands of fictional works, thus displaying a need to investigate how these

languages have affected those who come into contact with them, and therefore providing the

foundations of the desire to conduct a project on the true importance and purpose of the

constructed language.

Before delving into the complexities of constructed language, it is important to gain a better

understanding of natural languages, after all, they are the models on which conlangs are

based. The Oxford ‘ A Very Short Introduction to Languages’ by Stephen R Anderson

fiction. Anderson states that

“depending on the methodology of

provided an appropriate academic level on the topic, while also remaining concise. The first

few chapters covered the evolution of language, using Darwin’s theory of evolution to model

the progression of language. This proved to be a valuable perspective as it presented

language almost as a living being, a concept that particularly intriguing when looking at the

role of conlangs, suggesting that if they truly emulate natural language they could act almost

as an individual character in the work they appear in. However, this presentation of language

as a living, evolving being did also seem to challenge the extent to which a conlang could

ever truly emulate a natural language, as natural evolution could not be achieved within a

work of

language

categorisation, the outcome may change” (Anderson, 2012). Languages linked together in

one category can be completely unlinked by a different approach at sorting them. Although

this does not necessarily have much meaning in terms of conlangs, it does reinforce the

subjective nature of language, natural or constructed, and therefore the difficulty of being

able to accomplish a clear conclusion. This source provided a generous insight into the

complex world of linguistics, while aiding the contextual basis needed to understand any

accompanying academic journals containing further research on the topic, however due to

the nature of it being solely focussed on natural

languages, in itself it did not drive the

resultant thesis of the conclusion. Despite this, it did raise the question as to whether

conlangs could evolve. The answer seemed likely to lie within American linguist John

McWhorter’s work for TedEd, in which he states that Tolkien “charted out ancient and newer

versions of Elvish” (McWhorter, 2019) in order to mimic the evolution and progression

mapped by natural languages. McWhorter seems to be suggesting that unlike his linguistic

predecessors, Tolkien crafted entire histories or, as he referred to them, ‘mythologies’

through which his languages developed dialects, families and irregularities as a result of

migrating peoples, mingling tribes and the effects of centuries of passing time. From Tolkien

a new life was given to constructed languages, they were no longer an attempted vessel of

communication as were the International Auxiliary Languages of the nineteenth century such

as ‘Esperanto’ or Schleyer’s ‘Volapuk’, nor were they a jumble of foreign sounding words

heard in early film and television like ‘Danger Man’ or ‘Thoroughly Modern Millie’ in cases

where writers couldn’t find the time to assemble any real sort of vocabulary. Tolkien wasn’t

simply creating a collection of words to highlight the otherness of a character, he was

creating entire societies, histories, cultures, all dependent on and revolving around

constructed languages. It is within Tolkien’s legacy that answers to the question surrounding

the true purpose of conlangs in media begin to form.

Furthermore, Jessica Sams, conlanger and lecturer of linguistics at Stephen F. Austin State

University, states that “a solid language cannot be created in a vacuum”, continuing Tolkien’s

view that languages cannot be separated from the world and culture in which they are

spoken. However, as well as promoting the notion that conlangs aid the complexity of the

media they exist within in terms of the consumer, Sams also puts forward the perspective

that the existence of a conlang is key to understanding the world that is being created from

the position of the author. Her belief that “[the author] can’t create a language until they

understand the world it’s being spoken in” (Sams, 2016) appears to apply in both directions,

meaning that a deeper knowledge of the world one creates is required before creating a

language for its people. Perhaps, therefore, conlangs serve a purpose to the creators more

so than the consumers as they allow them to acquire an understanding of the world they are

creating that they wouldn’t have otherwise had. The words of a conlanger provide a perhaps

more enlightening outlook than some more third-party research. Sams’ perspective

correlates with that of the current frontrunner of fantasy languages, David J Peterson, in

terms of the suggestion that conlangs function more for their creators than their consumers.

Peterson’s book, ‘The Art of Language Invention’ details the history of conlang, from its

twelfth century religious beginnings in Hildegard von Bingen’s ‘Lingua Ignota’ (‘Unknown

Language’ in latin), to sixteenth century philosophical languages that strove to amend issues

concerning “the arbitrary association between form and meaning” (Peterson, 2015), to the

rise of ‘artlang’ in the twentieth century, the branch of constructed languages that exist in the

fictional arts. He, like Sams and Tolkien, is of the mindset that conlangs develop both the

world and characters of a piece of work. Peterson also recalls a time before the internet in

which the only people he could share his interests in language creation with were friends

and family, neither of whom, he says, were particularly interested. Peterson’s recollection

suggests that social media has provided a new lease of life for constructed languages as

groups of like-minded individuals are readily available. Though this is the case for all niche

points of interest, it must ring especially true for fans of constructed languages, as online

groups have come together and added to languages beyond their source material in many

cases, (a notable one being ‘Na’avi’, the conlang of the ‘Avatar’ films) something that before

the internet would most likely not have been able to occur. Peterson also states that with the

internet comes intense scrutiny for creators, as those eagle-eyed fans who notice errors can

congregate in forums and on social media platforms and unpick, stitch-by-stitch, scenes and

chapters that they have watched or read countless times together. This provides incentive to

creators to make sure that

the media they are putting out into the world, such as a

constructed language, is fully functional and correct, as it will more than likely be examined

under the microscope of the media. This image of close examination by fans also implies

that conlangs are not just trivial features of books or film, but are grounds for academic and

intellectual interest. This viewpoint of conlangs serving as academic property also supports

Sams mentioning in her interview that following classes on language creation, she had

multiple students admit

they were finally able to understand elements of natural

languages they were learning, with examples being Spanish tenses or cases in Russian.

Perhaps, then, the ever-growing presence of conlangs in commonly consumed media will

see a surge in an improved interest and ability to learn natural languages. Another purpose

of conlangs put

forward by Peterson is the ability to create phonaesthetic characters,

describing in his chapter on ‘sounds’ how with the tribe of sword-wielding, horse-riding

warlords, the Dothraki, he paired ‘harsh’ and ‘guttural’ sounds to add to the brutal nature of

their way of living. Further exploration into the concept of phonaesthetics can be found in a

journal by David Crystal, and the ideas he promotes are fascinating. Crystal starts with a

look into phonaesthetics via actors’ adopted stage names. While men often reject gentler

sounds like ‘m’ and ‘l’ (Maurice Micklewhite took on the moniker of Michael Caine), women

often do the reverse, with Norma Jean Baker becoming Marilyn Monroe. While a lot can be

said for these actors simply not liking their given names, it must also be considered that this

change in identity and sonic image was an attempt to phonaesthetically rebrand themselves.

This suggests that outward perception is heavily affected by how a word or name sounds,

allowing conlangers to therefore influence the perception of a group of speakers to the

outside world. Sounds condition what we see. From this, it is implied that phonaesthetics can

be read almost as a form of psychological conditioning; authors can completely shape the

way we perceive a character simply through the sounds of their language. Our perception of

morality can be altered through the use of either euphonic or cacophonic sounds.

languages that many would consider to be cacophonic are highly

Commonly,

saturated by guttural sounds, with this trope being so common that many current conlangers

consider it to be quite cliched. It must be remembered that euphony and cacophony are

‘harsh’

that

completely subjective, with what sounds nice to one ear sounding offensive to another. It is

also probable that the characterisation of guttural sounds as ‘harsh’ and often used by a

barbaric speaker is demonstrative of the intense westernisation of today’s media as to an

arabic speaker, for example, the guttural, throaty sounds of a language like Dothraki would

emulate common sounds of their language, whereas to a speaker of a latin language these

guttural sounds are alien to our common practises of speech. Through Peterson’s analysis it

seems unfortunately likely that there is a distasteful

link between the trope of a guttural

conlang and the natural languages that house those sounds, although it could be argued

that this allows better scope for social commentary within the fantasy genre. If the purpose of

conlangs first presented in this review is considered, in which the function of creating a

landscape, phonaesthetics can play a

fictional

language is to enhance the physical

meaningful role as not only do they enhance the creation and reception of characters, but

they can also help authors explore more deeply the physical geography of their land, thus

enabling them to worldbuild with more substance and structure. In his journal on language

evolution and climate Dr Caleb Everett noticed that language features develop in clusters,

with similar features developing in clusters in similar geographical landscapes. For example,

in the 6 highest altitude areas in the world there is an overrepresentation of ejectives, which

only feature in about 20% of the world’s languages. Ejectives are easier to enunciate at

higher altitudes as the air is thinner, so the force required to pronounce a sound is 26% less

than at sea level. Ejectives may also help reduce water vapour

loss as they are

non-pulmonic and so don’t require exhalation. This helps combat dehydration and altitude

sickness. There have also been links found between sonority (loudness) and climate. The

sonority of languages spoken in hot climates is generally higher as people are more likely to

be spending time outside, whereas people are more likely to be in closer proximity to each

other in colder regions. Lower sonority often also means that the mouth is not opened as

widely, preserving heat. However, areas of dense vegetation have the opposite effects in hot

and cold climates, respectively. While in a hot climate, dense vegetation obscures the

landscape, causing people to come closer together to speak, and so sonority is reduced,

whereas vegetation in cold climates provides protection from windchill, and so heat does not

have to be so intensely preserved. While it must obviously be kept in mind that correlation

does not

these statistics do point towards the fact that geographical

landscape affects language. While this also is probably not common knowledge of the

average fantasy reader or watcher, the incorporation of such features by a conlanger may

enable a subconscious, or perhaps scientific, association to certain regions, enhancing the

ability to worldbuild. This source, similar to the Oxford Short History, is focussed on natural

languages rather

research into natural

languages is hugely helpful when investigating conlangs as in order to construct a language

one must have a substantial knowledge of

It’s also

compelling to think that conlangers do incorporate elements such as those mentioned by

Everett, as even if they go largely unnoticed by the general public, language enthusiasts are

almost certain to pick them up. This concept of a sense of community between conlangers

language construction. True communities of

may also serve as another

conlangers came together for the first time online, firstly on a listserv forum, but as the

community grew various branches tailed off and before long an entire network of conlangers

was in full session. According to Peterson, it is on these sites populated solely by conlangers

that he has encountered the most impressive conlangs, not in wider media. We must then

language creation is not necessarily designed to meet the needs of its

consider that

linguistics and language history.

than conlangs. However,

imply causation,

remains that

function of

it still

consumers but is instead conducive to maintaining a sense of validation and purpose among

conlangers.

Though at least something of interest can be found in each source, the current research into

conlangs does appear to be lacking the perspective of a certain demographic: the fans. In

order to judiciously form any sort of conclusion this perspective seems something that this

topic is desperately in need of. I had reached out to Peterson by email early in my research

in order to obtain the direct perspective of a conlanger, but found that there was no real

equivalent contact in terms of conlang fans. After my conversation with Peterson, however,

there was a particular response that stood out to me; this was his conclusion that the only

aspect of real languages that could not be emulated by one that was constructed was the

aspect of mass communication, of ‘volume of speakers’. Peterson states that the fact

constructed languages are not – generally – used for communicative purposes was their only

limitation, all other linguistic aspects could be constructed. It seems natural to acquire the

opinions and experiences of someone who has learnt, for speaking purposes, a constructed

language. The majority of sources would suggest that the language with the largest reach

and therefore the highest likelihood that someone has learnt a decent amount of it was one

of Tolkien’s. Societies of Elvish speakers have before been interviewed and reported on, but

to actually locate and contact one of these is not as easy a task as articles covering such

groups may have you believe. An article by Justin Parkinson (2005) provides the account of

Zainab Thorp, a teacher who had run after school sessions – with much success – for

students interested in learning Elvish, describing how they “struggle through vocabulary and

verb tables” (Parkinson, 2005), but also how valued and enjoyed the sessions were. Thorp

states that she thinks the choice made by the pupils to voluntarily extend their learning

beyond the (non-fictional) curriculum “breaks the idea that education should simply be aimed

at getting a job”. An interest in constructed languages therefore enriches and expands

regulated learning. However, one criticism is that this article was unfortunately published in

2005, meaning that these schoolchildren would be well into adulthood, inciting doubt into the

slim possibility that they had retained much, or any, of their Elvish prowess. To find an

organisation more active than an early 2000s Elvish class, the most obvious option is the

Elvish Society,

found at elvish.org, a website filled with research, dictionaries and

manuscripts on Tolkien’s languages, though it still lacks a specific port of contact for the main

society itself. The Elvish Society does however list contacts for societies at both the

University of Oxford and the University of Cambridge, and while the latter appeared to be

fairly dormant, the Oxford website lists a very up to date term card, suggesting that sessions

are currently in action.

Finding the voice of Constructed Languages

I emailed the society, but after a few weeks of no reply and the awareness that the university

year was essentially over, I abandoned my efforts. Instead, I decided to take my research

elsewhere, namely Reddit. I created a google form with questions surrounding the personal

relevance of constructed fictional languages and posted it onto several forums on Reddit that

I thought would house members who were familiar with constructed languages, including

‘r/gameofthrones’, ‘r/conlangs’, ‘r/the100’, ‘r/startrek’, and ‘r/tolkienfans’. I felt that this would

be the most effective way of conducting a questionnaire due to the ability to get perspectives

of fans of multiple different conlangs, as I suspected that attitudes would be different from

fandom to fandom. It quickly became apparent that this was indeed the most effective

approach to gathering information as within half an hour I had already accumulated almost

twenty responses. Twelve hours later, I had almost two hundred responses. The results were

as follows:

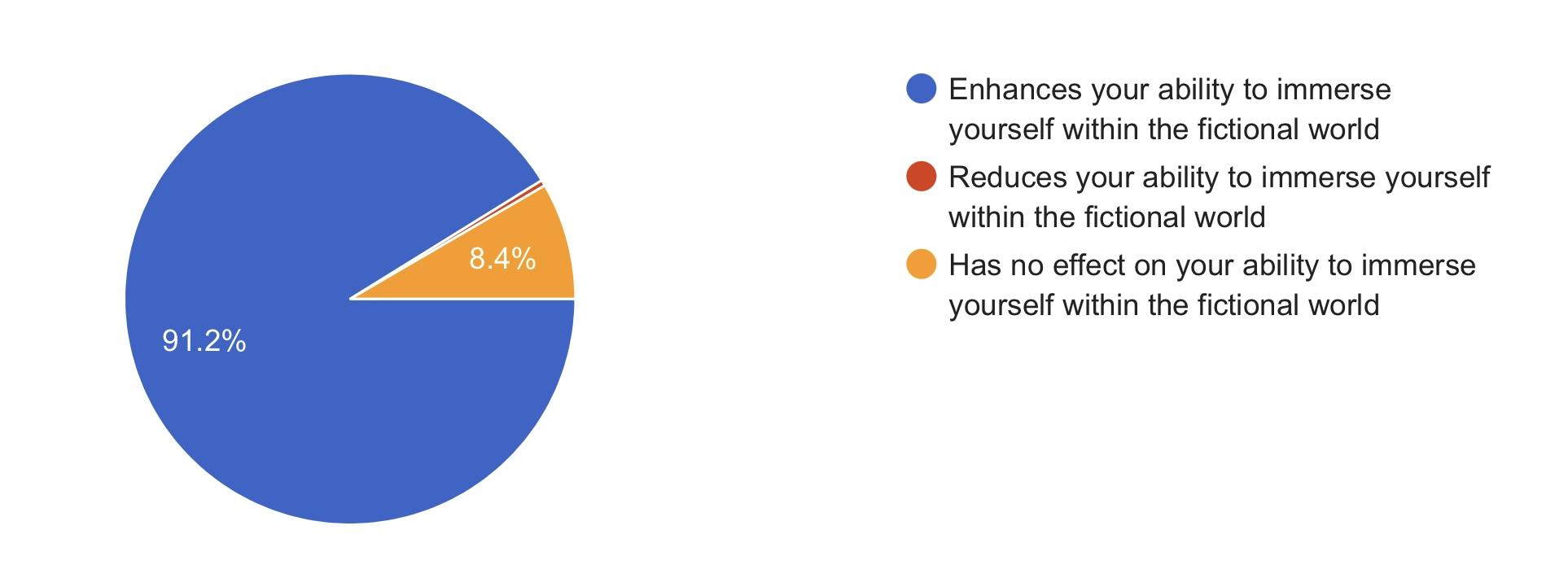

On the effect the presence of a constructed language in a piece of media has on the

consumer according to respondents:

Figure 1

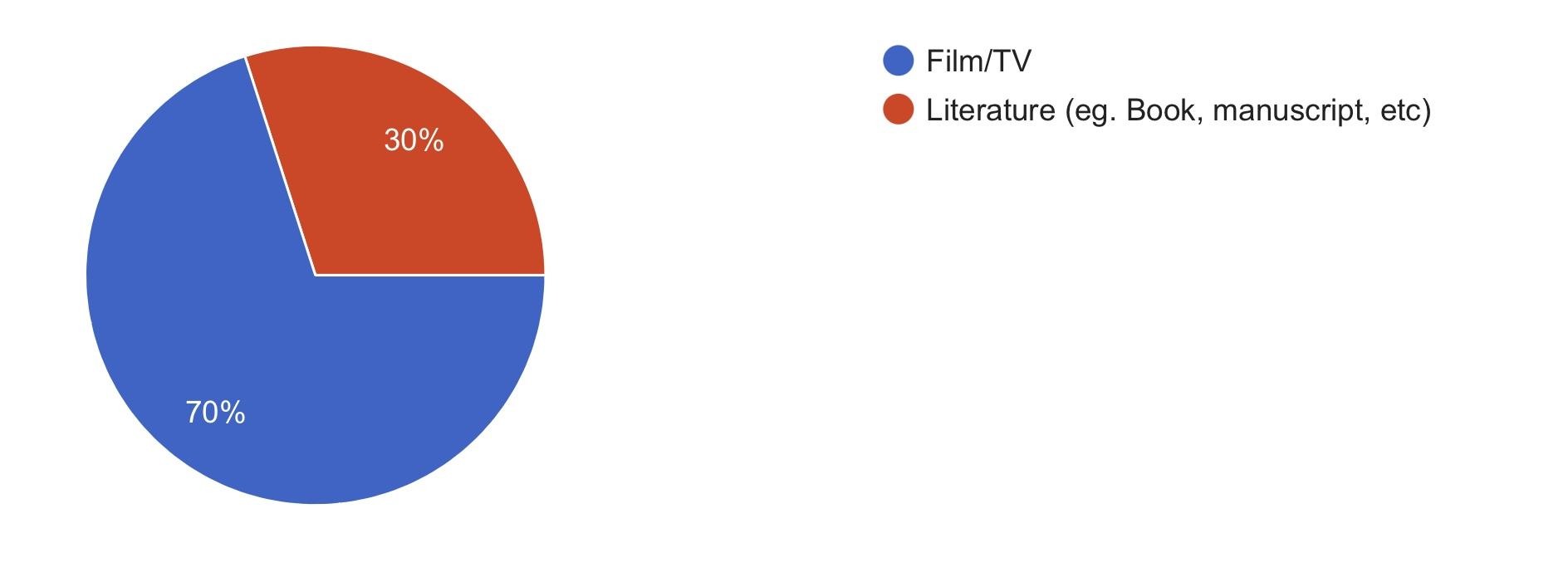

On the form in which a constructed language is more effective according to respondents:

Figure 2

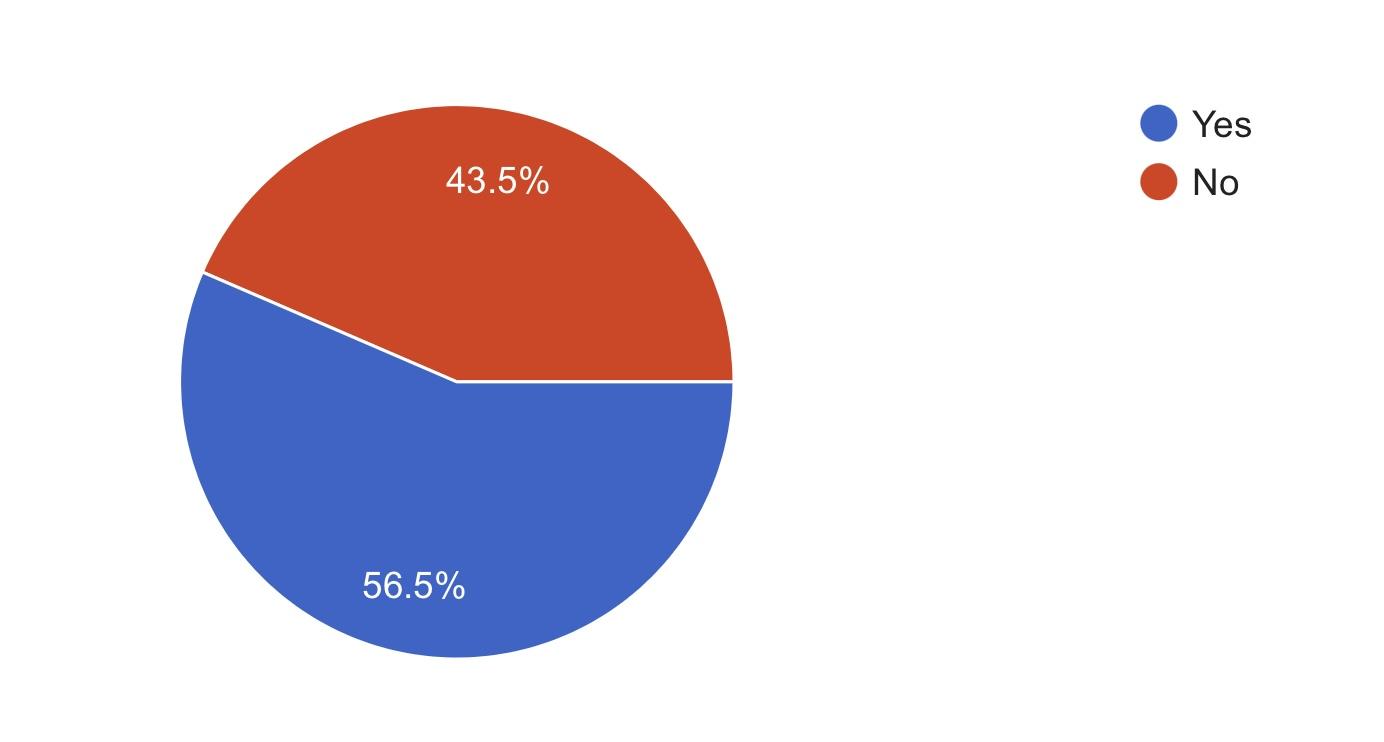

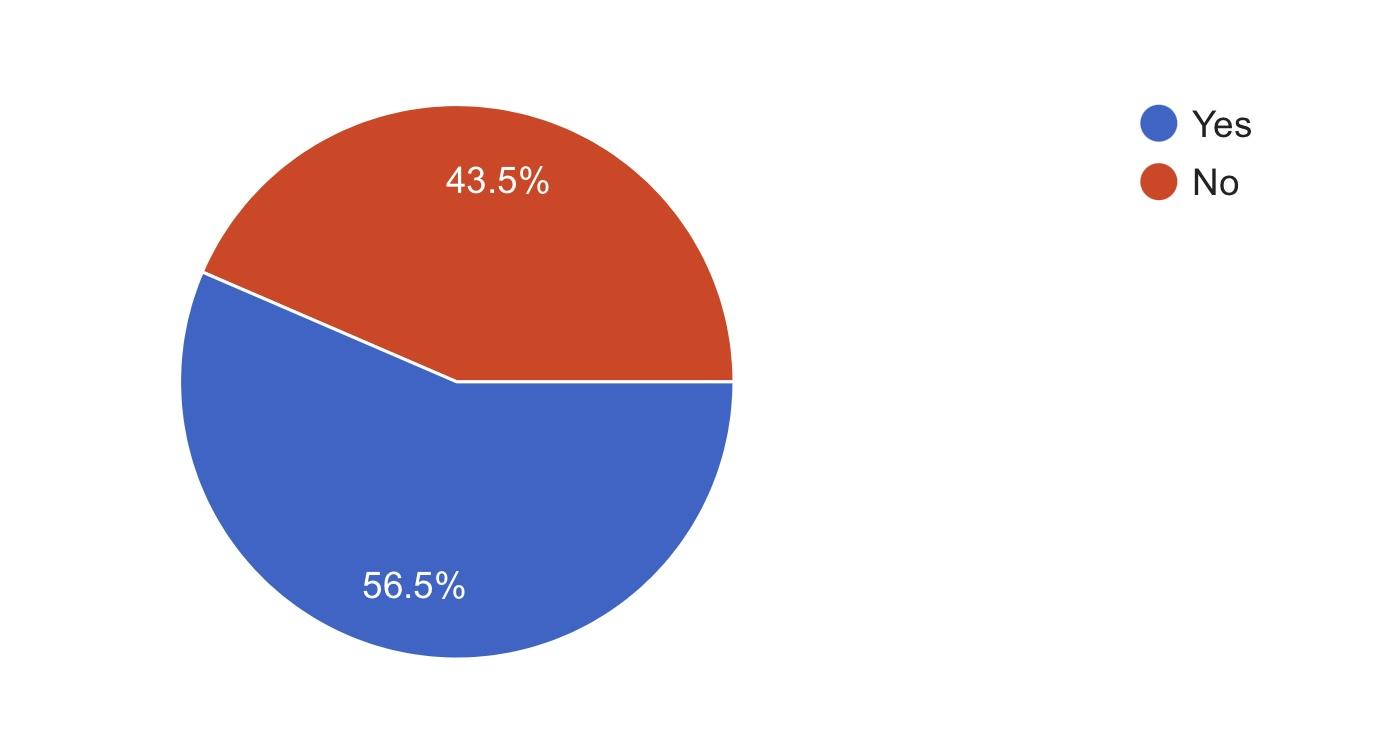

On whether respondents have considered learning a constructed language:

Figure 3

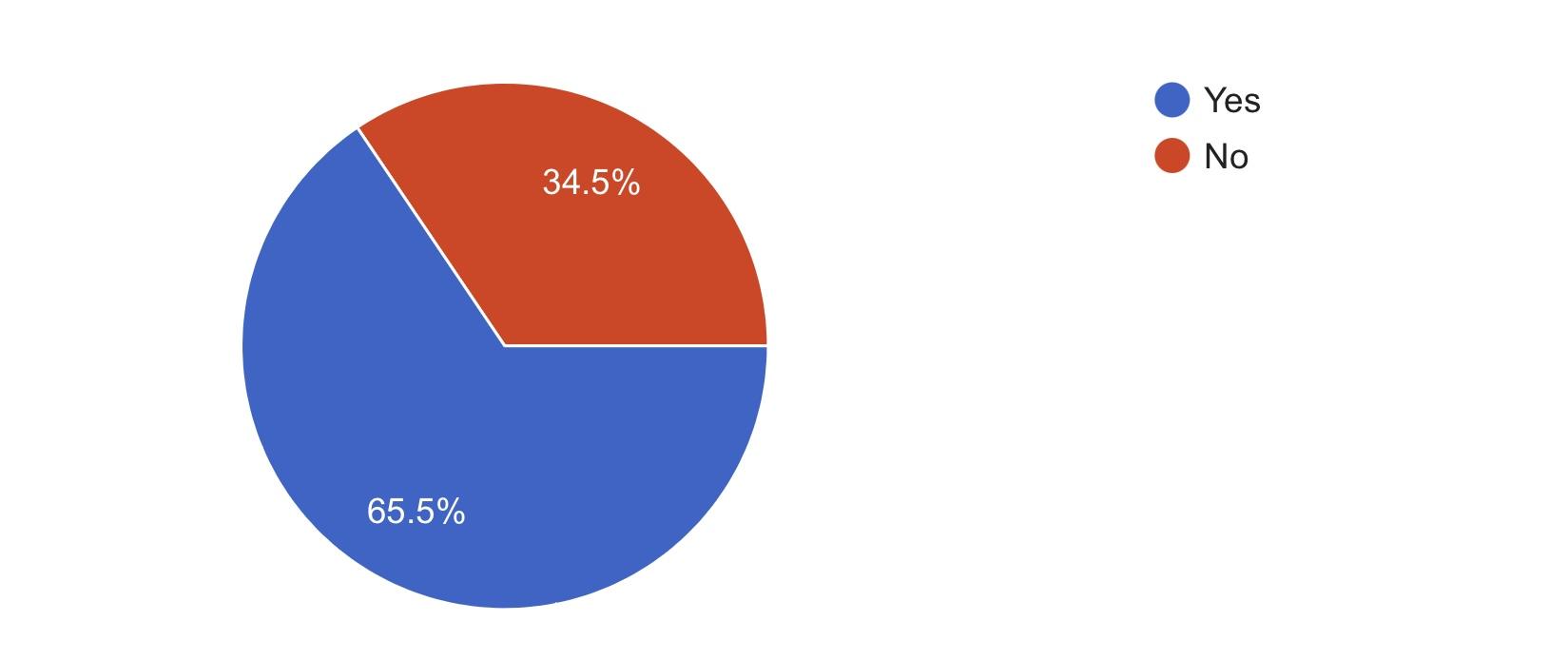

On whether respondents have attempted to learn a constructed language:

Figure 4

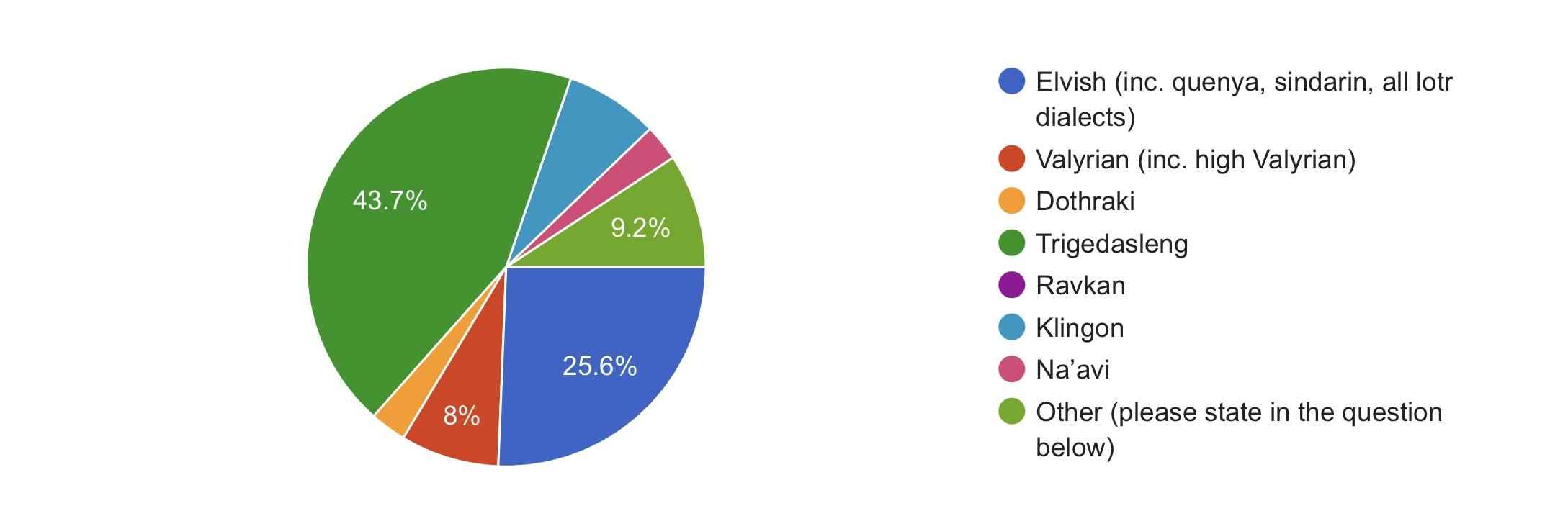

The constructed language with which respondents are most familiar:

Figure 5

languages play in personal lives and fandoms, one of the most

On the role that fictional

common responses was the unification of fandoms, with their respective conlangs acting as

a form of identity. One example was made of phrases like ‘Valar Morghulis’ acting almost as

a slogan and form of communication between fans of ‘Game of Thrones’. Another response

that provided an insight displaying the communicative function of conlangs within fandoms

was a respondent (and fan of

they had had conversations in

‘The 100’) stating that

Trigedasleng with another fan in a comment section of a social media platform. Other

responses came from conlangers who described the invaluable role that language creation

played in their lives, both as a hobby and an escape from reality as they further explored

their own fictional worlds. Generally, respondents agreed that the presence of a constructed

language within a piece of media allowed more depth and development of the fictional world

it exists in, as well as serving to create a more complex image of the cultures in said world.

Ideally, every response to the final question would have been shared as they each had a

unique and nuanced perspective on the meaning of fictional languages from those that are

most closely connected to them, but there were too many to include individually. Perhaps the

most surprising result of the survey was that Trigedasleng, referred to as ‘Trig’ by fans, had

been more widely learnt and consumed than much more historical languages (Tolkien’s) or

languages from franchises with more of a cult following (GOT), considering The 100 only

premiered in 2014. However, according to Peterson, who states that “there was no amount

of interest in any of [his] work that rivalled Trigedasleng” (Peterson, 2021) and others on

Reddit, this seems as if it could be due to the similarity of Trigedasleng to English, after all it

is supposed to be an evolved version of American English post-apocalypse. Peterson has

also stated previously that Valyrian would take roughly 50 weeks to learn, Dothraki about 26,

and Trig just 5. This may lead to the promotion of the thought that conlangs (and their

resultant popularity) serve almost as foils for our own language. They are almost a gateway

drug into linguistics masked by science fiction or fantasy, a linguistic sheep in fantastical

wolf’s clothing, if you will. It’s almost impossible, though, when watching content such as

‘The 100’ not

to decode the conversations in Trigedasleng, and

Peterson’s stoic placement of its origins within the American English dialect create an

entrancingly familiar set of vocabulary. To give an example, we can use the name of one of

the post-apocalyptic ‘grounder’ tribes, ‘Trishanakru’. The word can be broken down as

follows:

Firstly the ‘kru’ part is simply ‘crew’ and is a suffix used for all the tribes in the series, another

example being ‘skaikru’, used for the 100 themselves as they came down from space (the

sky), so are effectively labelled ‘sky crew’. Next, ‘tri’ means ‘tree’, with another tree-dwelling

tribe being called ‘trikru’ (‘tree crew’). Peterson next draws in visualistic, contextual, and

geographical details to his language creation; the Trishanakru inhabit a forest covered in

bioluminescent fungi, creating what could almost be described as ‘shiny’ trees, thus ‘trishana’

= ‘shiny trees’. It is words like this that allow us to see how Trigedasleng has developed from

the modern american English familiar to us, and likely part of what made ‘The 100’ as a

series so popular as legions of viewers attempted to decipher the origins of words and

phrases. Perhaps this investigative, revelatory aspect of conlangs is a function that many

have not yet considered, as the majority of those enthusiastic in the linguistic elements of

media like ‘The 100’ and similar shows fail to acknowledge that their interests may lie more

broadly in etymology.

least attempt

to at

Another interesting aspect of the survey was not in the results, but the comments on the post

it was uploaded on. Given the subjective and personal relationship between a conlang, the

consumer, and the piece of media in which it exists, a prominent factor in their investigation

is variation, and so to question multiple different conlang subgroups, in this case reddit

forums, seems essential. Though, as one might expect, different fandoms have different

relations to their respective conlangs, again due to the intense variety of constructed

languages, there were also widely different outlooks on the survey itself. The comments from

fans of media in which a conlang is present, such as those on r/gameofthrones or r/the100,

were largely the same and generally positive, with an encouraging amount of interest shown

in my findings. However, the comments on r/conlangs were far more critical of both the

intentions for the survey and the construction of the survey itself. In response to a user who

referred to the survey as ‘lacking nuance’ it was explained that the questionnaire was simply

to assess the opinions on conlangs of those familiar with them in any format, rather than

those necessarily equipped with extensive knowledge and understanding of

language

creation. This immediate contrast in reaction between fans of conlangs and creators does

suggest that they serve very different purposes depending on one’s relation to them. This

was an expected result, but the hostility of conlangers towards an attempt to conduct

It should be noted that the

research on their work could not have been anticipated.

conlangers responding to the survey were not professionals but amateurs,

for whom

conlanging is merely a hobby, so it was not a situation in which their patented corporate

property was at risk of exploitation. This reaction of amateur conlangers is indicative of

corroboration with the aforementioned point of conlangs serving an intellectual purpose for

their creators, rather than existing to be distributed alongside reams of fantasy literature and

film. Peterson’s experience of conlanging forums would also suggest this, as he states that

the most impressive conlangs he has been exposed to have not been for commercial

consumption but

intellectual stimulation and enjoyment. This attitude towards

conlangs is likely to come from the recent boom in members of the language creation

community due to the radical introduction of social media into the quotidian experience of a

two decades. While this explosion in

large proportion of

popularity is vastly considered to be a positive in terms of the emergence of new talent and

experiences within the conlanging process, a sense of frustration at the influx of interest

since conlangs gained popularity within the media must be understood on behalf of creators

who have been in the community since the beginning. This need of some conlangers to

seemingly ‘gatekeep’

their interest from others also aligns with conlangs acting as a form of

identity, and while I had originally considered this identification to be present within the

fandom culture rather than the creators, it seems that whether people are hearing, learning,

or producing conlangs, they become part of their character.

the population over the last

rather

Limitations to the methodology

I do accept that there are limitations to my findings as the sample population I surveyed were

those who I thought I would be able to obtain workable information from, and, holistically

speaking, the sample size of 239 respondents is quite small. If I were to conduct the survey

a second time, I might try to access a wider audience and perhaps try to target forums of

lesser-known media or conlangs as they might house more personal relationships between

fans and content, as opposed to the mass, and therefore in some ways more detached,

following of cult media such as ‘Game of Thrones’ or ‘Lord of the Rings’. However, overall

my findings can cohesively exist alongside the current research on the field. Purposes of

conlangs such as means of identification or enhanced worldbuilding put forward in the

articles I read continue throughout the results of my survey. The presence of such a variety

of purposes, yet purposes established from multiple sources and perspectives, reflects on

the extensive importance of conlangs within media as they can be conditioned to strengthen

so many aspects of the media they exist within, from the characters themselves to the

reception of a piece of work by the public.

From this report, it is suggested by the evidence displayed that one overarching purpose is

made clear in both the current research and the survey undertaken in the primary research,

and this is unification. It would be hard to think of another element in pieces of appropriate

media that provides the means for such intense intrigue and fascination. With the

consideration of the accounts of Sams and Peterson in addition to the survey, there is the

implication that to discuss conlangs in terms of ‘unifying’ encompasses many other forms of

their importance and purpose; They bring together groups of people in all directions, those

that construct them, those who study them, even those who criticise them. They are a vessel

through which fans can connect and learn, whether this learning be in terms of linguistics or

simply the lore of the fiction they love. Constructed Languages are also universal. So much

of today’s media is created for western entertainment, with consumers in other parts of the

world often having to watch or read dubbed or translated versions, respectively. Conlangs

provide ground that everyone, and at the same time no one, can understand. In a world

where so much can be lost

in translation, constructed languages act almost as our

signposts. Earlier in this essay there was mention of International Auxiliary Languages

(IALs), specifically Esperanto. The aim of these languages was to provide international

communication regardless of a person’s native language. By most accounts, the concept of

the IAL was a failure as people were reluctant to discard the identity of their native tongue.

However, in a time where so many have found a form of identity within fandom or fictional

work, this concept of a universal language has almost been reborn within fiction. Where IALs

lacked history and culture, conlangs provide centuries of legend, lore and myth. The internet

has allowed for entire generations to be globally connected via pop culture, and with so

much of this finding territory within the realm of the fantasy genre (Forbes Magazine listed

the premiere of ‘Game of Thrones’ as one of the defining pop culture moments of the

2010s), conlangs have inevitably been at the very heart of fan culture and will remain there

for the foreseeable future.

This essay has looked at the extent to which constructed languages serve an important

purpose in media. The concept of a constructed language is not new to today’s audiences,

but in the recent age of the internet has obtained a previously unheard of significance. Even

though it would be uncommon to encounter a fluent speaker of a language created within

fiction, it seems more unlikely to encounter someone who had never heard of one at all,

illustrating the universality of both conlangs and the fan culture that promotes them. Their

importance, however, extends beyond their

familiarity, as they have frequently been

referenced as a point of academic and intellectual interest for both fans and professionals of

the field, though the importance of conlangs as an educational entity is much more common

among those who more avidly follow and consume them.

It was also noted by both

conlangers Sams and Peterson, and linguist McWhorter, as well as the results of the primary

research that conlangs serve to enhance the media they exist within, enriching both the

characters and the setting of a novel, film, or whatever form of entertainment they are

housed within. The combined mood of the research conducted on constructed languages

indicates that this is the most important conscious purpose of a conlang in terms of the

author or director’s intention when deciding to include them in their work. However, it can

widely be said that providing a means of communication and unification is the most

important received purpose of constructed languages, as no other fictional element has quite

the same effect on an audience.

Reference list

Anderson, S.R. (2012). Languages : a very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Carus, A.W. (2016). The utility of constructed languages. [online] History and Philosophy of

the

Language

Sciences.

Available

at:

[Accessed 27 Jul.

2021].

Condis, M. (2016). Building Languages, Building Worlds: An Interview with Jessica Sams.

Resilience: A Journal of the Environmental Humanities, 4(1), p.150.

Everett, C., Blasí, D.E. and Roberts, S.G. (2016). Language evolution and climate: the case of

desiccation and tone. Journal of Language Evolution, [online] 1(1), pp.33–46. Available at:

https://academic.oup.com/jole/article/1/1/33/2281884 [Accessed 21 Jul. 2021].

https://www.facebook.com/thoughtcodotcom (2019). Phonaesthetics: Word Sounds and

Meanings.

[online]

ThoughtCo.

Available

at:

https://www.thoughtco.com/phonaesthetics-word-sounds-1691471 [Accessed 21 Jul. 2021].

Language Creation Society. (n.d.). Language Creation Society | Welcome to conlang.org.

[online] Available at: https://conlang.org [Accessed 17 May 2021].

McWhorter, J.

(2019). Transcript of “Are Elvish, Klingon, Dothraki and Na’vi real

languages?”

TED.

Available

at:

https://www.ted.com/talks/john_mcwhorter_are_elvish_klingon_dothraki_and_na_vi_real_la

nguages/transcript [Accessed 7 Aug. 2021].

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology. (n.d.). How to build a language. [online]

Available at: https://news.mit.edu/2019/constructed-languages-linguistics-1218 [Accessed 17

May 2021].

Peterson, D.J. (2015). The art of language invention : from Horse-Lords to Dark Elves, the

words behind world-building. New York, New York: Penguin Books.

Rahmanan, A.B.Y. (2019). The Most Defining Pop Culture Moments of the Past Decade.

[online]

Forbes.

Available

at:

https://www.forbes.com/sites/annabenyehudarahmanan/2019/12/24/the-most-defining-pop-cu

lture-moments-of-the-past-decade/?sh=3778872b67dd [Accessed 24 Aug. 2021].

The Lit Nerds. (2019). Deconstructing the Constructor: An Interview with Mark Rosenfelder.

[online]

Available

at:

https://thelitnerds.com/2019/06/03/deconstructing-the-constructor-an-interview-with-mark-ro

senfelder/ [Accessed 17 May 2021].

www.elvish.org.

(n.d.). The Elvish Linguistic Fellowship.

[online] Available

at:

https://www.elvish.org [Accessed 7 Aug. 2021].

www.youtube.com.

(2015). Do Mountains Alter

Speech?

[online] Available

at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PBz-JT00MZs [Accessed 21 Jul. 2021].