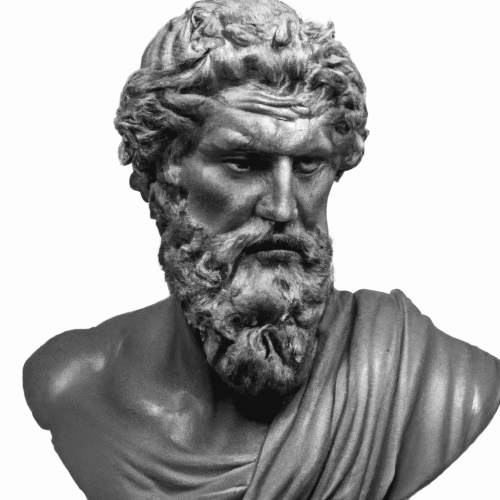

Thrasymachus (fl. 427 B.C.E.)

Thrasymachus of Chalcedon is one of several “older sophists” (including Antiphon, Critias, Hippias, Gorgias, and Protagoras) who became famous in Athens during the fifth century B.C.E. We know that Thrasymachus was born in Chalcedon, a colony of Megara in Bithynia, and that he had distinguished himself as a teacher of rhetoric and speechwriter in Athens by the year 427. Beyond this, relatively little is known about his life and works. Thrasymachus’ lasting importance is due to his memorable place in the first book of Plato‘s Republic. Although it is not quite clear whether the views Plato attributes to Thrasymachus are indeed the views the historical person held, Thrasymachus’ critique of justice has been of considerable importance, and seems to represent moral and political views that are representative of the Sophistic Enlightenment in late fifth century Athens.

In ethics, Thrasymachus’ ideas have often been seen as the first fundamental critique of moral values. Thrasymachus’ insistence that justice is nothing but the advantage of the stronger seems to support the view that moral values are socially constructed and are nothing but the reflection of the interests of particular political communities. Thrasymachus can thus be read as a foreshadowing of Nietzsche, who argues as well that moral values need to be understood as socially constructed entities. In political theory, Thrasymachus has often been seen as a spokesperson for a cynical realism that contends that might makes right.

Table of Contents

Life and Sources

Doctrines

Influence

References and Further Reading

Primary Sources

Secondary Sources

1. Life and Sources

The precise years of Thrasymachus’ birth and death are hard to determine. According to Dionysius, he is younger than Lysias, who Dionysius falsely believed to be born in 459 B.C.E. Aristotle places him between Tisias and Theodorus, but he does not list any precise dates. Cicero mentions Thrasymachus several times in connection with Gorgias and seems to imply that Gorgias and Thrasymachus were contemporaries. A precise reference date for Thrasymachus’ life is provided by Aristophanes, who makes fun of him in his first play Banqueters. That play was performed in 427, and we can conclude therefore that he must have been teaching in Athens for several years before that. One of the surviving fragments of Thrasymachus’ writing (Diels-Kranz Numbering System 85b2) contains a reference to Archelaos, who was King of Macedonia from 413-399 B.C.E. We thus can conclude that Thrasymachus was most active during the last three decades of the fifth century.

2. Doctrines

The remaining fragments of Thrasymachus’ writings provide few clues about his philosophical ideas. They either deal with rhetorical issues or they are excerpts from speeches (DK 85b1 and b2) that were (probably) written for others and thus can hardly be seen as the expression of Thrasymachus’ own thoughts. The most interesting fragment is DK 85b8. It contains the claim that the gods do not care about human affairs since they do not seem to enforce justice. Scholars have, however, been divided whether this claim is compatible with the position Plato attributes to Thrasymachus in the first book of the Republic. Plato’s account there is by far the most detailed, though perhaps historically suspect, evidence for Thrasymachus’ philosophical ideas.

In the first book of the Republic, Thrasymachus attacks Socrates’ position that justice is an important good. He claims that ‘injustice, if it is on a large enough scale, is stronger, freer, and more masterly than justice’ (344c). In the course of arguing for this conclusion, Thrasymachus makes three central claims about justice.

Justice is nothing but the advantage of the stronger (338c)

Justice is obedience to laws (339b)

Justice is nothing but the advantage of another (343c).

There is an obvious tension among these three claims. It is far from clear why somebody who follows legal regulations must always do what is in the interest of the (politically) stronger, or why these actions must serve the interests of others. Scholars have tried to resolve these tensions by emphasizing one of the three claims at the expense of the other two.

First, there are those scholars (Wilamowitz 1920, Zeller 1889, and Strauss 1952) who take (1) as the central element of Thrasymachus’ thinking about justice. According to this view, Thrasymachus is an advocate of natural right who claims that it is just (by nature) that the strong rule over the weak. This interpretation stresses the similarities between Thrasymachus’ arguments and the position Plato attributes to Callicles in the Gorgias.

A second group of scholars (Hourani 1962, and Grote 1850) emphasizes the importance of (2) and contends that Thrasymachus advocates a form of legalism. According to this interpretation, Thrasymachus is a relativist who denies that justice is anything beyond obedience to existing laws.

A third group (Kerferd 1947, Nicholson 1972) argues that (3) is the central element in Thrasymachus’ thinking about justice. Thrasymachus therefore turns out to be an ethical egoist who stresses that justice is the good of another and thus incompatible with the pursuit of one’s self-interest. Scholars in this group view Thrasymachus primarily as an ethical thinker and not as a political theorist.

In addition, there is a group of scholars (A.E. Taylor 1960, and Burnet 1964) who read Thrasymachus as an ethical nihilist. According to this view, Thrasymachus’ project is to show that justice does not exist. Burnet writes in this context: ‘[Thrasymachus] is the real ethical counterpart to the cosmological nihilism of Gorgias.’

Others (Barney 2004 and Johnson 2005) have stressed that Thrasymachus should not be read as a philosopher who offers precise definitions of justice, but rather as a sociologist or political scientist who offers empirical observations that amount to a cynical commentary on those who follow a traditional, Hesiodic conception of justice.

Finally, there are a number of scholars who claim that Thrasymachus is a confused thinker. Cross and Woozley (1964) contend, for example, that Thrasymachus advances different criteria for justice ‘without appreciating that they do not necessarily coincide.’ This claim has been renewed by Everson (1998). J.P. Maguire (1971) argues that only some of the arguments in book I of the Republic are Thrasymachus’ own, while other ideas are falsely attributed to Thrasymachus by Plato in order to prepare the ground for his own arguments.

3. Influence

In spite of the disagreement about how to interpret Thrasymachus’ arguments in book I of the Republic, his ideas have been influential in ethical and political theory. In ethics, Thrasymachus’ ideas have often been seen as the first fundamental critique of moral values. Thrasymachus’ insistence that justice is nothing but the advantage of the stronger seems to support the view that moral values are socially constructed and are nothing but the reflection of the interests of particular political communities. Thrasymachus can thus be read as a foreshadowing of Nietzsche, who argues as well that moral values need to be understood as socially constructed entities. In political theory, Thrasymachus has often been seen as a spokesperson for a cynical realism that contends that might makes right. This view frequently associates Thrasymachus with the arguments Thucydides attributes to the Athenians in their negotiations with the island of Melos (History of the Peloponnesian War, Chapter XVII). Thrasymachus is therefore frequently portrayed as an early version of Machiavelli who argues in The Prince that the true statesman does not recognize any moral constrains in his pursuit of power. In the scholarship on Socrates, Thrasymachus is sometimes seen as an interlocutor who shows the limits of the Socratic elenchus. C.D.C. Reeve (1988) argues, for instance, that the conversation between Socrates and Thrasymachus illustrates that Socratic questioning cannot benefit a person like Thrasymachus, who categorically denies that justice is a virtue. Reeve contends that this limit of the elenctic method provided the impetus why Plato proceeded to modify Socrates’ ethical principles in the remaining books of the Republic.

4. References and Further Reading

a. Primary Sources

Diels, Hermann. Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker. Rev. Walther Kranz. Berlin: Weidmann, 1972-1973.

Plato. Republic. Trans. G.M.A. Grube (rev. C.D.C. Reeve). Indianapolis: Hackett, 1992.