The Contemporary Esperanto Speech Community

Author: Adelina Solis

MS Date: 01-12-2013

FL Date: 01-01-2013

FL Number: FL-000010-01

Citation: Solis, Adelina. 2013. “The Contemporary

Esperanto Speech Community.”

FL-000010-01, Fiat Lingua,

Copyright: © 2013 Adelina Solis. This work is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

Fiat Lingua is produced and maintained by the Language Creation Society (LCS). For more information

about the LCS, visit http://www.conlang.org/

The Contemporary Esperanto Speech Community

by

Adelina Mariflor Solís Montúfar

1

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Introduction

1.1 Definitions

1.2 Political support for a universal language

1.3 A brief history of language invention

1.4 A brief history of Esperanto

1.5 The construction, structure, and dissemination of Esperanto

1.6 Esperanto and the culture question

1.7 Research Methods

Chapter 2: Who Speaks Esperanto?

2.1 Number and distribution of speakers

2.2 Gender distribution

Chapter 3: The Esperanto Speech Community

3.1 Terminology and definitions

3.2 Norms and Ideologies

3.3 Approach to language

Chapter 4: Why Esperanto?

4.1 Ideology-based reasons to speak Esperanto

4.2 Practical attractions to Esperanto

4.3 More than friendship

4.4 The congress effect

4.5 Esperanto for the blind

4.6 Unexpected benefits

Chapter 5: Esperantist Objectives

5.1 Attracting new speakers

5.2 Teaching Esperanto

Chapter 6: Conclusion

Works Cited

3

4

5

9

14

17

24

29

34

34

47

58

58

65

70

81

83

86

94

95

100

102

103

103

107

116

121

2

Chapter 1:

Introduction

When we think about invented languages, we may think of childhood games.

Children often generate a secret language to keep foes or adults from understanding,

but this childhood foray is more often a short-lived code based on the language

already spoken by all parties, rather than a true new language. We might also think of

hubris and high ideals and failure: history is littered with the tomes of constructed

languages that failed to attain the popularity their creators desired. However, as a

nineteen year old in a divided city, Ludwik Zamenhof did create a new language, one

that he hoped would bring the people of the world together on an equal plane. It

would break down linguistic barriers between people, and pave a path towards peace.

He was so impacted by the language-based social division around him that, along

with his language, which he released in 1887 under the pseudonym of Dr. Esperanto –

from the word in his invented language for ‘one who hopes’ – he created an ideology

of equality and brotherhood that he hoped all of his followers would embrace.

3

1.1 Definitions

First, let us set forth some terminology. A ‘universal language’, sometimes

also called ‘global’, ‘world’, or ‘international’, is one that is (intended to be) spoken

by every person on earth. There have been many attempts to designate, develop,

construct, or implement a language as a universal language. Proposed universal

languages usually fall within one of five approaches. The first is to use a pre-existing

natural language1, usually a language with political clout or many speakers, or the

native language of whoever is making the argument for its implementation. The

second:

To use two or more natural languages, either as zonal tongues to serve certain

areas of the earth, which would not give us an international language, but a

series of geographically separated international languages; or to be learned

bilingually or trilingually by all the peoples of the earth (Pei 1958: 96).

The third approach is to modify a natural language and output something more

standardized and easier to learn. Modifications may range from limiting the lexicon,

making the spelling phonetic, or simplifying the grammar. Fourthly, to combine

natural languages: “the mixture is sometimes simple, as when it is suggested that one

language be spoken without change, but be written with the script of another tongue”

(Pei 1958: 96). Franco-Venetian or pidgins are examples of this fourth class, but are

complex fusions of phonologies, grammars, and vocabularies.

Last and most numerous are the fully constructed tongues, which may come

close to the modified national language or the mixed language, or may utterly

depart from the natural tongues … these constructed tongues usually reveal a

blend of many natural languages combined with arbitrary features of grammar

and word-building (Pei 1958: 96).

1 A ‘natural language’ is defined in contrast to a constructed language. A similar term is ‘national

language,’ but some natural languages are not spoken by an entire nation, or do not have governmental

backing, so the latter term is insufficiently inclusive.

4

Languages in the third through fifth classes are commonly referred to as constructed

languages2. Other terms include planned, artificial, or invented languages, as the

languages come into existence through the work of a particular person, who either

completely fabricates language or knits together preexisting language elements

according to his or her aesthetic. In this paper, the terms ‘universal language’ and

‘constructed language’ will be used3 except when quoting an author with a different

preferred term. It is important to note that a language’s aim to become universal is not

necessarily to be at the expense of other languages. When this distinction is especially

important, the term ‘auxiliary language’ will be used.

1.2 Political support for a universal language

Enabling universal understanding has been a goal pursued by many, be they

language inventors, economists, or those in the political sphere. While language

inventors have motivations ranging from personal fame to facilitating trade or world

peace, those who support constructed languages have their own reasons to do so.

Political climate has often served as a push for a global language, be it natural or

constructed. Mario Pei explores this facet of universal language movements in his

2 For more on the significance and connotations of this and other terms, see Detlev Blanke’s, “The

Term ‘Planned Language’”.

3 Blanke concludes that ‘international language’ is the most appropriate term, but I feel that to call a

language ‘international’ does not convey the full scope of intended use. If a language were used in two

countries, it would still be international. Esperanto is intended to be used in all nations, therefore I

choose to call it and any other language with similar intent ‘universal.’

Blanke also concludes that ‘planned language’ is the most accurate or appropriate term but, for the

purposes of this paper, I disagree. I wish to emphasize the role of the creator. One option would be to

use the term ‘invented language,’ but I find that the word ‘invented’ obscures the sustained efforts of

the language creator. Instead, ‘constructed language’ best conveys both the presence of a creator and

the process of creation, or construction.

5

biased – if not outright propagandistic – book, One Language for the World. In the

chapter titled, ‘What a world language will do for us’, Pei uses a rhetoric common

among those advocating the adoption and implementation of a global language:

A world language for the future is for a future world of peace and

international cooperation, in which communications and the interchange of

ideas will have their fullest development. By itself, the world language can

never bring about such a world. But it can effectively aid in bringing it about,

through the removal of linguistic and even, to some extent, of ideological

misunderstandings, and through the creation of a healthy atmosphere wherein

men regard one another as fellow human beings (1958: 50-51).

He waxes on:

Short of a foolproof system for preventing war and ensuring perpetual peace,

coupled with freedom for the individual, the adoption of an international

language is the greatest gift with which we could collectively endow our

children and their descendants (Pei 1958: 60).

Pei’s opinion is clear, but what is his evidence? He asserts that the existence of a

universal language would enable a remarkably rapid transmission of information,

disseminated around the world in a single language rather than going through

countless tedious translations. He discusses how much easier life would be for

tourists and business travelers, who would be able to communicate with more than a

guidebook’s selection of phrases. Pei describes the time and effort required to learn

just one language, and how this investment often resembles a form of academic

roulette, to attempt to identify which people and therefore which language might

come into power and become worthwhile to study (1958: 21-23). Furthermore,

writing in 1958, six decades away from our present, Pei sees the pressing effects of

globalization or a shrinking world on our communicative needs (1958: 35).

After thoroughly addressing the present need for a universal language, Pei

considers past attempted solutions and then looks to future potential resolutions. In

6

his discussion of past attempts, Pei looks at Esperanto, which he calls “probably the

most famous and successful of all constructed languages” (1958: 161). At the time of

Pei’s writing, Esperanto was permitted to be “used internationally in telegrams, along

with Latin,” and, “in Gallup polls conducted in minor European countries, Esperanto

[turned] out to be the second choice for an international tongue, with English as the

first choice” (1958: 163). Pei mentions those who criticize Esperanto for not being

sufficiently universal, especially because of an excess of Germanic roots that do not

correlate to any other languages, but Pei also comments on its strengths. By “adopting

roots from different sources to distinguish between meanings of what is, even in

natural languages, the same word: piedo, for instance, is ‘foot’ as a part of the body,

but futo is ‘foot’ as a measure,” Esperanto “shows the beginnings of a system that

may prove to be the solution of its own troubles” (Pei 1958: 164). Pei does not

directly state it, but this is a clear reference to those in centuries past who sought a

logical language, free of the confusion of homonyms and the like.

Daniele Archibugi also addresses political issues relevant to linguistic

diversity in a 2005 article titled: The Language of Democracy: Vernacular or

Esperanto? A Comparison between the Multiculturalist and Cosmopolitan

Perspectives. He takes on Will Kymlicka’s assertion that “democratic politics is

politics in the vernacular,” and the complications that arise from this premise within

multilingual communities. While his approach is more analytical than persuasive,

Archibugi echoes some of Pei’s points regarding the reasons some kind of

overarching shared language would be beneficial.

The resurgence of the language problem in our era is the result of two

fundamental contemporary historical processes. The first has to do with the

7

increased interdependence between distinct communities… State political

communities have become increasingly permeable to trade flows, migrations,

mixed marriages, and tourism. The second phenomenon has to do with the

increased importance of individual rights, which has emerged both in a

broadening of rights in democratic states and in an increase in the number of

states in which democracy is in force (Archibugi 2005: 539).

He also provides specific figures indicating the problem – or at the very least, the

strain – caused by linguistic diversity. “Of the nearly 5,000 employees of the

European Parliament, 340 are translators and 238 are interpreters,” and as more

countries vie for membership, this number could as much as double (Archibugi 2005:

551). Furthermore:

As official languages have increased, so the translation procedure has grown

more complex: there are currently 20 x 19 = 380 possible language

communications (‘into’ and ‘from’), and finding interpreters capable of

translating, for example, from Portuguese to Slovak or Lithuanian to Maltese

and vice versa is often impossible, hence the recourse to ‘double translations’

(2005: 551).

Like many who address approaches to cross-linguistic communication, Archibugi

touches on the relevance of Esperanto. However, Archibugi views it as a noble but

failed attempt, not really a feasible option for the future. He concludes his paper

with, “rather than to choose today between the vernacular and Esperanto, it might be

more useful to support investment in education to allow individuals to improve their

language skills” (Archibugi 2005: 553). Pei, in contrast, ends his book with

instructions to the reader on how to move forward, closing emphatically with,

“wherever you are, if you believe in one language for the world, let your government,

the UN, and UNESCO know it!” (1958: 251). Both agree that linguistic diversity

makes life, international relations, intranational understanding, and political

representation difficult, and is an issue that needs to be addressed.

8

1.3 A brief history of language invention

Others also found problems with the state of world languages, and they took it

into their own hands to invent a language that would address the issues perceived. For

some, like John Wilkins, taking after George Dalgarno (Okrent 2009: 45-50), the

problem with language was its vagueness. For others, like Ludwik Zamenhof, the

problem was that languages were not culturally transcendent. It may be asked, were

these men linguists? Scholars? Most language inventors were educated, but they were

philosophers, nuns, feminists, mathematicians, and everything in between (Okrent

2009). Zamenhof was an optometrist with a good education and a big dream. What

connects all of these people was the seed of an idea that inevitably sprouts roots

potent enough to consume whoever begins to water it.

The annals of history reveal that the impetus to invent languages has been

around nearly as long as human language itself, though the motivations vary and

overlap. In her popular history, In the Land of Invented Languages, Arika Okrent

explores the histories of select languages from five hundred languages created over

nine hundred years, presumably five hundred among many more whose

documentation disappeared over the centuries. She describes the urge to invent and

redesign as, “at least as old and persistent as the urge to complain about language”

(Okrent 2009: 11). Several language inventors cited the noble cause of fixing the

problems with current language. Language is vague, ambiguous, redundant, full of

exceptions, and still leaves us unable to find the words we want. In short, language is

inefficient. Philosophers yearned for a perfect, unambiguous, logical language that

9

would unfetter the mind from the effects of imperfect language, freeing humans to

ponder the mysteries of existence at a higher level. This impetus to systematize

language is not as unfounded as it may seem. Up until the seventeenth century,

mathematicians represented relationships in a haze of words. The Pythagorean

Theorem, for example, was rendered by Sir Thomas Urquhart of Cromarty in the mid

1600s as:

The multiplying of the middle termes [sic] (which is nothing else but the

squaring of the comprehending sides of the prime rectangular) affords two

products, equall [sic] to the oblongs made of the great subtendent, and his

respective segments, the aggregate whereof, by equation, is the same with the

square of the chief subtendent, or hypotenusa (qtd in Okrent 2009: 31).

When this muddle was replaced with symbols and operators and equations,

relationships revealed themselves, and comparisons became much more possible.

Best of all, the new system was independent from spoken language and therefore

universally understandable. With such clarity and simplicity came innovation and

rapid progress; calculus and physics were developed. So, if a systematization of

mathematics could clear the haze and reveal so much that had been obscured by the

murk of words, it stood to reason that a systematization of language would yield

similarly profound results.

After working with scholar and language inventor George Dalgarno and

having his suggestions turned down, John Wilkins of London spent over a decade

working on his own attempt at one such pure language. He named it simply,

Philosophical Language, and described it as being “free from the ambiguity and

imprecision that afflicted natural languages. It would directly represent concepts; it

would reveal the truth” (Okrent 2009: 24). He intended to catalogue the universe, to

10

reduce everything to its essence under an elaborate system of classification. He had

an expansive tree, an Aristotelian hierarchy, that branched out into forty categories,

each with its own subsequent tree. Concepts were organized by meaning, from

general to specific. To get to ‘Beasts’, the node number twenty-eight of the forty, one

would have to correctly navigate down the tree as follows: Special (not general) >

creature (not Creator) > distributively (not collectively) > substances (not accident) >

animate (not inanimate) > species (not parts) > sensitive (not vegetative) >

sanguineous (not Exsanguineous) > Beasts. Clearly, Wilkins’ system was not

particularly simple, albeit perhaps remarkably comprehensive, nor was it as intuitive

as he hoped.

Entertaining was a bodily action, but shitting was a motion – so was playing

dice. While things as different as irony and semicolon were grouped together

(under discourse > elements), things as similar as milk and butter were placed

miles apart (milk with the other bodily fluids in “Parts, General,” and butter

with the other foodstuffs in “Provisions”) (Okrent 2009: 58).

One thing was to find the location of a concept in the tree, but still another was to find

the desired meaning of one word with many concepts. Wilkins provided an index for

English words, but the word ‘clear’ had twenty-five options. “Do you mean ‘not

mingled with another’? Then see ‘simple.’ Do you mean ‘visible’? Then see ‘right,’

‘transparent,’ or ‘unspotted.’ Do you mean ‘as refers to men’? Then see ‘candid’…”

(Okrent 2009: 60), and on and on. Wilkins’ language required absolute certainty of

intended meaning and eradicated redundancy by grouping synonyms together at the

tree’s endpoints. Then, the endpoints were denoted by a ‘word’ constructed from

information indicating the location of the word within the tree. However, one version

of ‘clear’ expanded to the meaning of its concept, transforms it into “a transcendental

11

relation of action belonging to single things pertaining to the knowledge of things, as

regards the causing to be known, being the opposite of seeming” (Okrent 2009: 64).

Even with the benefit of exactitude in intended expression, to construct a sentence

with its fully expanded true meaning yields an incomprehensible quagmire, nothing

near the clarifying simplicity yielded in mathematical systematization. Though it

initially gained favor with the king and was slated to be translated into Latin,

Wilkins’ oeuvre, like so many before it, fell into obscurity, never attaining the

intellectually revolutionizing effects of which Wilkins dreamt.

Wilkins was an exception in his time, not because of his linguistic endeavors,

but because of their profundity. In the age of reason, it seemed as though every

gentleman had his own sketch of a constructed language, if only because it was in

vogue and good for the ego. This gentlemanly dabbling, however, rarely resulted in

much more than a flighty lexicon at best. Sir Thomas Urquhart of Cromarty described

his language, Logopandecteision, whose name literally means “gold out of dung,” as

“a most exquisite jewel, more precious than a diamond inchased in gold, the like

whereof was never seen in any age,” but he had more praise for what his language

was allegedly capable of than details about how exactly it would do it (Okrent 2009:

27-28). In regards to this array of efforts, Mario Pei asserts:

The main contribution of the seventeenth century to the solution of the

international language question is fundamentally that it called attention to the

problem and established a principle which the interlinguists of future centuries

would make use of, the principle of departing from the illogicity of the natural

languages (1958: 90-91).

It may be more appropriate to assert that the play in logical language construction

bore negligible fruit, except that it suggested a possible path for future peoples

12

frustrated by the absence of a global language. They could look beyond the

implementation of a natural language, and explore constructed languages with

systematized regularity, as was the case with Esperanto, a planned language that

found considerable success within the limited scope of success enjoyed by planned

languages at large, which I will later discuss.

Other creative minds in more recent years have produced fictional languages

to more fully develop fantasy worlds. J. R. R. Tolkien, though known for his book

series, The Lord of the Rings, purportedly created his expansive mythology to create a

world for his languages, and not the other way around (Okrent 2009: 283). He said,

“nobody believes me when I say that my long book is an attempt to create a world in

which a form of language agreeable to my personal aesthetic might seem real. But it

is true” (Okrent 2009: 283). Whatever the motivation for people to undergo the

remarkable task of developing a constructed language – ostensibly a much more

involved task than perceived when the inventors began, few to no languages can be

said to have found the popularity their creators hoped. A handful of these languages

have found a sustained following or had a brief period of popularity. Klingon and

Na’avi, two languages created for Hollywood characters, have yielded an invested

population that often urges the creator to take the language far beyond his original

intent or expectation, forming groups on the Internet that dissect language samples to

codify the grammar and phonology. However, these languages represent an

anomalous rationale and outcome.

The Internet now serves as a network for the modern equivalent of

seventeenth-century gentleman dabblers. Okrent describes the growing number of

13

online forums for ‘artlang’4 or ‘conlang’5. Here, language enthusiasts can get

feedback on their creations. As always, the impetus behind conlanging comes in

many forms:

Toki Pona, a language of simple syllables that uses only positive words, is

intended to promote positive thinking; … Brithenig was designed as “the

language of an alternate history, being the Romance language that might have

evolved if Latin speakers had displaced Celtic speakers in Britain. … The

urge to push features to their limits is also found in languages like Aeo, which

uses only vowels, and (the self-describing) AllNoun (Okrent 2009: 288).

The contemporary inventors Okrent describes seem to have mostly self-indulgent

motivations, not seeking to right some linguistic wrong or create something practical.

They want to play with language, and test the limits of what constitutes a language.

Whether they be inspired by a ‘what if’ world or the idiosyncrasies found in natural

languages, the languages that populate these forums indicate that perhaps a lesson has

been learned from the slew of failed historic attempts to resolve world problems via

language invention.

1.4 A brief history of Esperanto

In the midst of this history of language invention, peppered with failure and

salted with personal interest, Esperanto emerged. In 1887, under the name of Dr.

Esperanto, Ludwik Zamenhof published the guide to his language, now known as

Esperanto, but its origins were much earlier. Ludwik Zamenhof began inventing his

language as a teen in culturally and linguistically divided Bialystok, now in Poland,

4 Art language

5 Constructed language

14

where Russians, Poles, Germans, Jews, and others coexisted in space but not in spirit.

He wrote in his journal:

In that city, more than anywhere, a sensitive person might feel the heavy

sadness of the diversity of languages and become convinced at every step that

it is the only, or at least primary force which divides the human family into

enemy parts. … I was taught that all men were brothers, while at the same

time everything I saw in the street made me feel that men as such did not

exist: only Russians, Poles, Germans, Jews and so forth. … I kept telling

myself that when I was grown up I would certainly destroy this evil (qtd in

Okrent 2009: 94, 95).

Home life taught him Russian, Yiddish, and Hebrew; Polish and perhaps Lithuanian

he learned on the street; Latin, Greek, French, and German, he learned in school.

However, this multilingualism served as a further reminder of division that

surrounded him. He wrote:

No one can feel the misery of barriers among people as strongly as a ghetto

Jew. No one can feel the need for a language free of a sense of nationality as

strongly as the Jew who is obliged to pray to God in a language long dead,

receives his upbringing and education in the language of a people that rejects

him, and has fellow-sufferers throughout the world with whom he cannot

communicate (qtd in Janton 1993: 24).

Of the myriad language inventors before him, Zamenhof’s experiences may be said to

have given him the noblest intentions and the most profound connection to the cause

of universal language.

He was not an ivory-tower linguist, out of touch with the concrete problems

arising from, and expressed by, language differences… he saw the creation of

an international language as simply a first step toward a more general goal of

peace… directed at all those who suffered or were oppressed by language

discrimination (Janton 1993: 25).

Consequently, the nobility of his intentions went beyond the creation of a language.

In his conception, the practice of Esperanto was to be bound to an ideology of

respect, one that would cultivate the fraternity Zamenhof aspired to inspire between

15

all humankind. Zamenhof realized that conflict was not just about language; it

stemmed from religion, class, and capital. It stemmed from power. This was part of

why he felt that his language was better suited to being a language of the world than

some other natural language. The difficulty of natural languages is such that only

those with leisure and financial resource can take up the task of learning one,

resulting only in “an international language for the higher social classes”, not really a

universal language at all (Zamenhof, qtd in Janton 1993:29). Instead, with Esperanto,

“everyone, not just the intelligent and the rich, but all spheres of human society, even

the poorest and least educated of villagers, would be able to master it within a few

months” (qtd in Janton 1993: 29). But Zamenhof’s aspirations went beyond universal

linguistic understanding. He wrote to Alfred Michaux:

My work for Esperanto is only part of this idea. I never stop thinking and

dreaming of the other part, … This plan (which I call “Hillelism”) involves

the creation of a moral bridge by which to unify in brotherhood all peoples

and religions, without creating any newly formulated dogmas and without the

need for any people to throw out their traditional religions. My plan involves

creating the kind of religious union that would gather together all existing

religions in peace and into peace (qtd in Janton 1993: 31).

Again, as with the intended paradigm for the use of Esperanto, he focuses not on

replacing existing beliefs, but on creating a common ground. Though Hillelism,

which was later renamed homaranismo, was sometimes called a religion, it was more

about generating “a ‘neutrally human’ doctrine … toward the common aspirations of

all people. It sought to put the concept of humanity above those of nation, ethnic

group, race, class, and religion” (Janton 1993: 32). Zamenhof described it as a means

of “communicating with people of all languages and religions on a basis that is

neutrally human, on principles of common brotherhood, equality and justice” (qtd in

16

Janton 1993: 31). Still, this second column of Esperantism, which could in fact be the

central one, as the ideologies that it puts forth are the ideologies that led to the

creation of the language, were often downplayed so as not to make Esperanto the

language too political or controversial. “His ideals, particularly his views on religious

ecumenism, were at odds with many of the more practical and down-to-earth

bourgeois commercial types who adopted his language” (Tonkin 2008: 4), and so

Esperanto was presented as a practical tool with “an optional yet fundamental

philosophy” (Janton 1993: 35). Still, Zamenhof knew that those who expressed

passionate commitment found their passion in the ideals of it, not in the practicality of

it (Janton 1993: 35).

1.5 The construction, structure, and dissemination of

Esperanto

Unlike other language inventors, who clung to the rules of their language,

Zamenhof released his sixteen rules of grammar and welcomed innovation within the

framework. He did not seek to micromanage others’ attempts to combine his roots to

produce more words and expand his original lexicon. After 1889, by which point

Zamenhof had published two books on Esperanto as well as a supplementary third

publication, “from [that] point on, he considered the language not as his own property

but as belonging to everyone. Its development would depend on all friends of the

‘sacred idea’” (Janton 1993: 27). Moreover, “he submitted proposals for reform to the

Esperantists, accepted their verdict, and always regarded himself a simple user of

Esperanto among all the others” (Janton 1993: 30).

17

He freely submitted the language to the criticism of his correspondents and to

the readers of La Esperantisto, the earliest Esperanto magazine. … its articles

examined various modifications and reforms in the language, some of which –

including the suppression of certain consonants, abandonment of the

accusative ending and adjectival agreement, and modification of certain

suffixes – show that Zamenhof was willing to depart radically from his

original conception (1993: 41, 42).

Still, Zamenhof wanted to protect his language from arbitrary change, and a language

whose grammar was under constant revision would prove difficult to learn. Indeed,

the failure of Volapük6, a similar language movement that preceded Esperanto by

eight years, demonstrated the perils of incessant revision (Janton 1993: 42 and Jordan

1997: 41). The downfall of Volapük redirected enthusiasts to Esperanto, and these

new members boosted its numbers but brought with them their zeal for language

revision. In 1894, the defected Volapükists contributed to a rising pressure for reform

of Esperanto, but when Zamenhof submitted a list of proposed reforms to be voted on

by readers of La Esperantisto, the majority of the votes opposed the reforms (Jordan

1997: 42, 43). The first international Esperanto congress in 1905 designated

Zamenhof’s publication, the Fundamento de Esperanto, “which perpetuated the

language in its 1887 form,” as the official model of the language (Jordan 1997: 43

and Janton 1993: 42). Henceforth, the language’s rules were to be held constant.

Here, I will reproduce the famous ‘Sixteen Rules’ of Esperanto, as presented

in Pierre Janton’s Esperanto: Language, Literature, and Community7:

1. There is no indefinite, and only one definite article, la, for all genders,

numbers, and cases.

2. Nouns are formed by adding –o to the root. For the plural, -j must be

added to the singular. There are two cases: the nominative and the

6 For more on the history of Volapük, see Bernard Golden’s “Conservation of the Heritage of

Volapük.”

7 For an analysis of Esperanto linguistics see Janton’s Chapter 3: “The Language”.

18

objective (accusative). The root with the added –o is the nominative, the

objective adds an –n after the –o. Other cases are formed by prepositions.

3. Adjectives are formed by adding –a to the root. The numbers and cases are

the same as in nouns. The comparative degree is formed by prefixing pli

‘more’; the superlative by plej ‘most’. ‘Than’ is rendered by ol.

4. The cardinal numerals do not change their forms for the different cases.

They are: unu, du, tri, kvar, kvin, ses, sep, ok, naŭ, dek, cent, mil. The tens

and hundreds are formed by simple junction of the numerals. Ordinals are

formed by adding the adjectival –a to the cardinals. Multiplicatives add

the suffix –obl; fractionals add the suffix –on; collective numerals add –

op; for distributives the word po is used. The numerals can also be used as

nouns or adverbs, with the appropriate endings.

5. The personal pronouns are: mi, vi, li, ŝi, ĝi (for inanimate objects and

animals), si (reflexive), ni, vi, ili, oni (indefinite). Possessive pronouns are

formed by suffixing the adjectival termination. The declension of the

pronouns is identical with that of the nouns.

6. The verb does not change its form for numbers or persons. The present

tense ends in –as, the past in –is, the future in –os, the conditional in –us,

the imperative in –u, the infinitive in –i. Active participles, both adjectival

and adverbial are formed by adding, in the present, -ant-, in the past -int-,

and in the future -ont-. The passive forms are, respectively, -at-, -it-, and –

ot-. All forms of the passive are rendered by the respective forms of the

verb esti (to be) and the passive participle of the required verb. The

preposition used is de.

7. Adverbs are formed by adding –e to the root. The degrees of comparison

are the same as in adjectives.

8. All prepositions take the nominative case.

9. Every word is to be read exactly as written.

10. The accent falls on the penultimate syllable.

11. Compound words are formed by the simple junction of roots (the principal

word standing last). Grammatical terminations are regarded as

independent words.

12. If there is one negative in a clause, a second is not admissible.

13. To show direction, words take the termination of the objective case.

14. Every preposition has a definite fixed meaning, but if it is necessary to use

a preposition, and it is not quite evident from the sense, which it should

be, the word je is used, which has no definite meaning. Instead of je, the

objective without a preposition may be used.

15. The so-called foreign words (words that the greater number of languages

have derived from the same source) undergo no change in the international

language, beyond conforming to its system of orthography.

16. The final vowel of the noun and the article may be dropped and replaced

with an apostrophe.

19

In his paper, “Variation on Esperanto,” Bruce Arne Sherwood looks at the

morphology of Esperanto. Aside from grammatical endings, such as those denoting

part of speech or tense, almost all other morphemes are free. This makes Esperanto

highly productive. Take, for example, kato ‘cat’ and katido ‘kitten’, and hundo ‘dog’

and hundido ‘puppy’. Ido is not –ido; it can stand alone, and its meaning is

‘offspring’. Sherwood also explores the rather undefined field of proper Esperanto

pronunciation. “Good pronunciation also reflects the phonological character of

Esperanto, distinguishing among all the phonemes, minimizing allophony, and

conserving the strict relation between pronunciation and orthography” (Sherwood

1982: 7). In another sense, “good pronunciation is geographically neutral, not

manifesting regional or national peculiarities and making it difficult to identify the

speaker’s nationality” (Sherwood 1982: 7). Sherwood indicates that mild national

accents are acceptable or even sometimes enjoyed so long as the accent does not

obstruct meaning, “but it appears that speakers do recognize and prize an

international or nonnational pronunciation style” (1982: 7). Sherwood lauds the five-

vowel sound system of Esperanto for minimizing the effect of national accent:

Intelligibility for such a sound system is more resistant to destruction by

national accents than is, say, English as spoken by foreigners. For example, a

slight error in vowel height in English can change “beat” to “bit”, whereas

such an error in Esperanto must be much larger before timo ‘fear’ is confused

with temo ‘theme’ (Sherwood 1982: 5).

With this vowel system, international Esperanto communication is insulated from

confusion that might be caused by accent interference.

Beyond disseminating the set of rules, Zamenhof provided writing samples,

which yielded insights into the intended syntax of the language. He supplemented the

20

rules with six “specimens of international language”: the Lord’s Prayer; a portion of

the Book of Genesis; a letter in Esperanto; two original poems, Mia penso (My

thought) and Ho, mia kor’ (Oh, my heart), and a translation of Heine’s poem, Mir

träumte von einem Königskind, which became En sonĝo princinon mi vidis (Tonkin

2008: 3). In addition to the Fundamento and these original supplements, Zamenhof

translated a large body of preexisting literature to “refin[e] Esperanto by tackling the

difficulties and subtleties of natural languages” (Janton 1993: 92). Zamenhof began

with Hamlet in 1894, and gradually processed several European linguistically diverse

masterworks, as well as the complete Old Testament (Janton 1993: 92). Through

these translation projects, Zamenhof drastically expanded the original lexicon, but

according to Humphrey Tonkin, he also injected Esperanto with cultural legitimacy

and tradition: “the existence of literary works in a language is a guarantee that it has a

life of its own, and that it is connected to the cultural past: it declares that Esperanto is

not a code, but rather a work of art grounded in earlier works of art” (2008: 4). The

choice to translate the daunting and monolithic Hamlet was particularly significant:

The late nineteenth-century Hamlet of Central and Eastern Europe was no

indecisive weakling, but the very epitome of the seeker after truth. …

Examine the independence movements of Central Europe and Hamlet is never

very far away. Thus Zamenhof begins his linguistic movement – … with a

revolutionary statement, a statement that at one blow might silence those who

suggest that his language has no life. … It was a brilliant move: it gave the

early Esperantists a sense of cultural dignity, and above all it linked them with

the elite cultures of Europe (Tonkin 2008: 6).

Zamenhof translated several other dramas, and Tonkin asserts that this efficiently

generated a written model of the language, as well as a model of natural speech

(2008: 4). Furthermore, it firmly rooted Esperantists in a tradition of literature, be it

translated or original, and provided “opportunities for linguistic experiment, and a

21

sense of cultural solidarity” (Tonkin 2008: 9). Indeed, by 1993, it was estimated that

10,000 works had been translated into Esperanto (Janton 1993: 93). Now, according

to the President of the Quebec Esperanto Society, “there [are] 50,000 books in

Esperanto and CDs from classical music to rap” (Normand). But the contemporary

strength of Esperanto is proven by more than its prolific literary production8. Because

it has now been in existence for over 100 years, there have been several generations

of Esperantists. People have met through Esperanto, fallen in love, had Esperanto as

their only common language, and consequently raised their children to speak

Esperanto. A 1968 study located 150 families where Esperanto was the language of

the home, and this information, coupled with Esperanto marriage notices in Esperanto

periodicals, lead Bruce Sherwood to estimate the existence of between one thousand

and two thousand native speakers9 of Esperanto in 1982 (1982: 2). Esperanto has

started to become a natural language.

Needless to say, Esperanto has not attained the level of use that Zamenhof

envisioned. Still, the language – albeit among a relatively small community of

speakers and enthusiasts – has carved a place for itself in modern society. The

international library in Parma, Italy, houses Esperanto periodicals among its

collection of international literature. Facebook, a popular social networking website,

offers an Esperanto option among language settings. Wikipedia, a popular Internet

encyclopedia, can be read in Esperanto. Because Wikipedia is based entirely on user

contribution, this means that all of Wikipedia’s Esperanto content has been generated

8 For more on the history of Esperanto literature, see Jukka Pietiläinen’s “Current trends in literary

production in Esperanto”

9 For more on Esperanto as a natural language, see Jouko Lindstedt’s study, “Native Esperanto as a

Test Case for Natural Language”.

22

by Esperantists who wish to have the option to spread and receive information in

Esperanto, rather than in their native language, and felt so motivated that they took

the time to translate or produce the content themselves. Ubuntu, a computer operating

system, can be installed in Esperanto. Similarly to the Wikipedia case, for Ubuntu to

be available in Esperanto, someone had to take the time to generate an additional

Esperanto interface. Interesting to note is that Ubuntu is named after a Southern

African ethical ideology, and the principle roughly translates as “humanity towards

others” or “the belief in a universal bond of sharing that connects all humanity”

(About the Name). This ideological overlap may be coincidence, or it may point to

why Ubuntu programmers created an Esperanto interface.

Just like contemporary constructed languages, Esperanto has taken advantage

of the Internet to create forums, disseminate information, and recruit new enthusiasts.

Mark Fettes, in “Interlinguistics and the Internet”, describes how, originally, the

spread of languages like Esperanto and Volapük was made possible by “the

development of efficient postal and transportation systems in 19th-century Europe”

(1997: 1). Now, however, with the Internet, “rapid, low-cost, many-to-many

communication across political and geographical boundaries,” is possible, which

augments the spread of constructed languages (Fettes 1997: 1). Furthermore, it

“lowers, though it does not remove, one of the greatest barriers to research into

Esperanto: its invisibility to the uncommitted” (Fettes 1997: 2), and, ostensibly,

makes it easier for the curious to access resources that might draw them in.

1.6 Esperanto and the culture question

23

Aside from the linguistic criticism Esperanto faced in its earlier years, and the

offshoot language projects organized by disgruntled dissenters10, Esperanto’s

relationship to culture has been a point of contention. Esperanto is intended to be

culturally neutral, but some critics claim that it is not neutral enough. “Seventy-five

percent of the lexemes in Esperanto come from Romance languages, primarily Latin

and French; 20 percent come from Germanic languages; the rest include borrowings

from Greek (mostly scientific words), Slavic languages, and, in small numbers,

Hebrew, Arabic, Japanese, Chinese, and other languages” (Janton 1993: 51).

Furthermore, because the lexicon of Esperanto continues to grow, there is dispute

about whether it is becoming overly Latinized (Sherwood 1982: 3, 4). Still, “the

continued strength of the Esperanto movement in Asia is likely to ensure that the

needs of non-European speakers will not be neglected” (Sherwood 1982: 4). Bruce

Sherwood calls the fact of this European lexical base “one of the few truly well-

founded criticisms of Esperanto” (1982: 4). Because its linguistic foundation is so

heavily European as opposed to global, linguistic determinists argue that Esperanto is

necessarily embedded with European cultural values. Esperanto has tense

transformations absent in many Asian languages; its sound inventory contains sounds

foreign to Asian languages, and its phonology allows for consonant clusters

disallowed in Asian and other languages, so some assert that Esperanto is less

linguistically egalitarian than it claims. These are certainly additional hurdles for an

Asian would-be speaker of Esperanto, such as the l-r distinction that is difficult for

native speakers of Japanese (Sherwood 1982: 6), but these are not necessarily

10 See David Jordan’s section, “Id and Ido” and Okrent pages: 109, 116, 143, 144, for more on related

projects

24

prohibitive difficulties. Sherwood suggests that Asian Esperantists may not have as

much difficulty as might be expected because, “almost all Japanese study English

before they study Esperanto, and this may be the case with some Chinese

Esperantists, too, with the result that their use of Esperanto may be colored by

English (and the Latin vocabulary of English)” (Sherwood 1982: 4). In the present

context, “the large number of Latin roots … is more of an advantage than a

disadvantage if we bear in mind that English, so far the most universal of the national

languages, draws over half its words from the Romance languages” (Janton 1993:

51). At the very least, to learn Esperanto is like learning any natural language, but

with a broader scope of utility.

While Esperanto is attacked for being insufficiently neutral, others assume

that an artificial language cannot have a real culture, and consequently believe that

Esperanto lacks some intrinsic value held by natural languages. Arthur Aughey cites

Michael Oakeshott, who calls Esperanto “one of those rationalist projects with which

the history of modern Europe is littered” (1992: 9). The problem with this “joke”,

Esperanto, is: “language is not just communication of the utilitarian kind, but the

expression of the identity and the cultural unity of a people. Language is not about

calculations of convenience, but is the expression of something akin to the ‘national

soul’” (Aughey 1992: 9). Esperanto is a product, and its practicality is not enough of

a draw to compensate for the devaluing effects of being seen as existing in a cultural

vacuum.

But, given the common belief that language and culture are almost symbiotic,

is it really possible for Esperanto to be cultureless? Esperanto cites cultural neutrality

25

as part of its appeal to the masses, and while this is not to be confused with

culturelessness, if the term culture is ambiguous, cultural neutrality is more so. When

Zamenhof set out to create his language, one of hope for the world, he had a rigorous

ideology of brotherhood and peace – albeit one he consented to make ‘optional’ for

his followers – embedded in it. If Esperanto’s cultural neutrality were to manifest by

equally representing or including all cultures, favoring none above another, this

would align with its theme of equality. Cultural neutrality might also intend to refer to

not adopting a particular nation-specific culture but, from this interpretation,

Esperanto is still criticized for linguistically favoring European languages and

therefore propagating European ideologies, absorbing cultural elements via linguistic

styling.

Esperanto speakers themselves firmly contend that Esperanto has a culture.

Lernu!, “a multilingual website which aims to inform Internet users about Esperanto

and help them to learn it, easily and free of charge,” has a page dedicated to the

culture of Esperanto (About Esperanto). Tonkin describes the early construction of

Esperanto culture via literary translation and production. Arika Okrent describes the

“distinctly Victorian flavor” of the ceremonies that take place even in contemporary

Esperanto congresses (2009: 117). She puts forth the equation, “forced tradition +

time = real tradition,” and argues that part of the reason Esperanto succeeded where

other, very similar, projects failed, was because of this cultural injection: “people who

may not have been inspired to learn a language in order to use it for something would

learn a language in order to participate in something” (Okrent 2009: 117). Oakeshott

may have seen Esperanto as a utilitarian artifice, but many others claim that it has

26

developed its own culture, and consider this part of why Esperanto found relative

success:

Although many Esperantists tried, even while Zamenhof was still alive, to

eliminate from Esperanto any hint of ideology, the very name of the language

encapsulated idealistic aspirations and served to inspire enthusiasm in

generation after generation. We can certainly look at Esperanto from a purely

linguistic point of view, but no purely linguistic examination of the

phenomenon can explain its uniquely powerful attraction, its energizing

powers, and its rich diversity (Janton 1993: 27).

Esperanto’s cultural foundation was painstakingly laid by Zamenhof’s writings and

translations. From this deliberately formed foundation, over a century of speakers and

dreamers has laid down bricks, building a rich, cohesive culture.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis asserts that an individual’s language influences

the structure of thoughts and, consequently, the perception of and interaction with the

world. Though the strength of this correlation is widely contested, it would not be

unreasonable to say that the learned culture linked to a language – not the structure of

the language – could impact a speaker’s interaction with the world. As members of a

speech community, Esperanto speakers have a particular, internal set of norms of use

for their shared language, but the effect of their language ideology is also relevant to

their interactions beyond the speech community.

Membership in the Esperanto community is officially defined in accordance

with the decisions made in the Bolougne Declaration, but to know the grammar of a

language is not the same as cultural competency, or functionality within the speech

community. Today, we know who the speech community was supposed to be:

everyone. We know what the speech community’s ideology was supposed to be:

universal brotherhood and equality. Histories of the development of Esperanto

27

abound. There have been several studies concerning the grammar of Esperanto and

the development of Esperanto as a natural language. But, relatively few studies have

been made regarding the Esperanto speech community at large, now, over a century

after its inception11. We know the dream and we know the beginnings, but we want to

know today’s reality.

So, the questions I will address are:

1) Who comprises the Esperanto speech community?

2) What are the norms adhered to and ideologies held by members of the

speech community?

3) Why are people members of the speech community?

4) What are the objectives of the speech community?

The existence of a speech community can be hard to establish, but an observable trait

of a speech community is a shared language ideology: the social and political values

embedded in the language. Consequently, analysis will focus on shared norms and

ideologies as evidence of the Esperanto speech community.

1.7 Research Methods

To conduct this study, I solicited participants through a personal contact

involved in the Esperanto community, who distributed my request for participants

through an Esperanto electronic mailing list. Those interested then contacted me and

11 Among notable recent studies, La rondo familia. Sociologiaj esploroj en Esperantio was conducted

by Nikola Rašic’s over the course of sixty years, and completed in 1994. While this study was

published in Esperanto, it has been written about and cited in subsequent English-language articles and

studies. Another recent study is “Standardization and self-regulation in an international speech

community: the case of Esperanto” by Sabine Fiedler, published in 2006. For more, see the section,

“the Esperanto movement and speech community,” in Humphrey Tonkin’s article, “Recent Studies in

Esperanto and Interlinguistics: 2006,” published in Language Problems & Language Planning in 2007.

28

in some cases passed on my solicitation to their own contacts within the community.

Ultimately, this resulted in thirteen participants (organized by chronology of

interviews):

Chart 1.1: Participants

Participant

Age

Location

Country of Esperanto

Acquisition, if different from

current location

Randy

Normand

Jim

Zdravka

Joshua

Helm

stevo

Jorge/Kior

Jerry

Tatyana

Will

Joel

Yevgeniya

41 Atlanta, Georgia, USA

54 Montreal, Quebec, Canada

37 Atlanta, Georgia, USA

58 Montreal, Quebec, Canada

29 Oakland, California, USA

73 Uppsala, Sweden

55

55

68 Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA

53 Ukraine

25 Madison, Wisconsin, USA

32 Montreal, Quebec, Canada

32 Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Cincinnati, Ohio, USA

Recife, Brazil

France

Croatia

USA

Ukraine

Jorge was interviewed via textual chat using Google Chat. stevo preferred to answer

questions in written form, via email. All other interviews were conducted via

telephone or Skype and lasted from thirty minutes to an hour. All calls were recorded

for audio and later transcribed. Participants were offered $10 USD in compensation,

though some declined or requested that I make a donation to an Esperanto

organization instead.

Interviews were conducted in a semi-structured format, with a flexible set of

questions and a few demographic questions. Questions asked included:

1. Have you read the participant consent form and do you agree to participate?

29

2. What name or pseudonym may I use as your name in my Thesis?

3. Please tell me the story behind you and Esperanto. When did you develop an

interest in it? How did you find out about it? How old were you? How old are

you now? How long have you been speaking/studying it? Have you ever been

more or less active than you are now?

4. What made you interested in Esperanto?

5. What do you know about the history of Esperanto or its creator? Did this

knowledge play a part in your interest in Esperanto, or did you learn about this

after becoming interested/active?

6. What method(s) did you use to learn Esperanto?

7. How would you describe your level of proficiency in Esperanto? Are you

equally confident speaking, listening, and writing? How comfortable or fluent

are you in the language?

8. What is your native language? Do you speak any other languages? What is

your level of proficiency in those? How does your study of Esperanto

compare to that of any other languages you may have studied?

9. What do you know about any constructed languages other than Esperanto, or

derivatives of Esperanto? Have you ever been interested in any of them? Why

or why not? Why do you prefer Esperanto? Do you?

10. How often do you use Esperanto? In what contexts? Do you participate in any

Esperanto conversation groups or other Esperanto organizations? Do you

subscribe to any Esperanto publications or do you read literature in

Esperanto?

11. Have you ever been to any Esperanto conventions or gatherings? How many

people attended? Have you ever traveled to meet other Esperanto speakers or

interacted with Esperantists outside of this group? What was it like?

12. What do you consider a good accent? Do you find a difference in the

Esperanto (pronunciation) of people with a different first language? Have you

ever had a hard time understanding someone’s Esperanto? Was it because of

their accent or for some other reason?

13. Sometimes people feel like the language they use affects what they can

express or how they express things. Some multilingual people feel like one

language can more accurately convey certain thoughts or feelings. Have you

experienced any of this with Esperanto?

30

14. Would you call yourself an Esperantist? What does that mean to you? Do you

feel different when you are around other Esperanto speakers?

15. Do you think Esperanto has any flaws? Is there anything (about the

community or the language itself) that you dislike or wish were different?

16. I have read that some people are concerned about too many new words being

added to Esperanto instead of using pre-existing roots, or that the new roots

draw too much from languages like English. Have you noticed this? What are

your thoughts? Is this really an issue?

17. How do you think non-Esperantists perceive you given your membership in

this group? Positively or negatively? How do people react when they find out

you speak Esperanto? Do you have any anecdotes about this? Do you usually

tell people, is it something people find out about you organically, or do you

avoid revealing this about yourself? Do you think outside perceptions of

Esperanto/Esperantists are positive or negative, accurate or inaccurate? How

so?

18. Women in Esperanto?

19. Do you have a significant other? Does he/she speak Esperanto? Would you

take a partner who does not speak Esperanto? Would you encourage him/her

to learn it? Have you ever thought about whether you would teach it to any

children you may have?

20. Have you ever been more or less active than you are now? Do you continue to

study Esperanto? Do you think you will continue your involvement in the

future?

Demographic Questions

1. What level of education have you attained or do you intend to attain?

2. What was your field of study?

3. What is your current occupation?

4. How old are you?

5. What is your city of residence?

As interviews were conducted, new questions arose from certain responses, and these

questions were either interview specific (e.g. Tell me more about the language you

constructed.) or incorporated into the body of questions for future interviews (e.g.

How many people were at the congresses you attended?). Most participants permitted

31

me to use their full name or their first name; three elected a pseudonym. For

consistency, I use only their first names or pseudonyms here.

There were a few difficulties encountered during the process. While this was

not a prohibitive difficulty, it was sometimes challenging to arrange a mutually

suitable interview time, given that there was often a time difference between my

location and the participants’, some as great as nine hours. Because I do not speak

Esperanto, I was limited to interviewing participants who speak a language that I do

speak.12 One person suggested that I contact a mailing list for Esperanto families, but

warned me that a request not in Esperanto would not be well-received. For some

participants who were not native English speakers, interview questions were abridged

to accommodate their language comfort level. Joel and Yevgeniya were interviewed

together, which sometimes yielded interesting exchanges between the two, but

sometimes caused the second respondent’s reply to be an affirmation of the first,

rather than a personal expression.

Overall, participants were very enthusiastic about participating, and expressed

curiosity about the outcome of my research. They admitted that they had never given

much thought to some of the questions, like how they personally defined the term

12 During the interviewing process, I was made hyperaware of the privilege I was born into by having

English as my native language. There I was, talking to people about this culturally neutral language

that is supposed to bring the world together, using exactly the kind of language of power that the

language was invented as a reaction against. Some respondents asked me if I spoke Esperanto, and I

would reply that I wanted to but had not yet progressed enough to conduct the interviews in said

language. Even without Esperanto, I was able to interview several people from around the world

whose first language was not English. I thought about what it would be like if I did not speak English

or some other major world language. Although many Esperantists have studied several national

languages, I would likely be severely limited in access to respondents until I learned Esperanto myself.

I felt particularly guilty, so to speak, when I interviewed Zdravka, the Croatian wife of a French-

Canadian Esperantist. While she was very capable of expressing herself in English, she was noticeably

uncomfortable in the language. Part of the idea of Esperanto is to put people on equal footing when

communicating. No one is speaking his or her native language. Yet, my inability to speak Esperanto

required that she use a language that was not her preference, and made it hard for me to communicate

my apologetic gratitude for her participation.

32

“Esperantist,” but valued the push to do so. Because of the semi-structured nature of

the interviews, participants were encouraged to say whatever they wanted, whether or

not it addressed the question being asked. While many apologized for “babbling” or

going off on tangents, I often found these moments the most insightful. It was often

from these moments that I realized that there were other questions I should consider

adding to my original corpus.

33

Chapter 2:

Who Speaks Esperanto?

“People who get interested in this type of thing, like Esperanto, Ido, or any of

the constructed languages, are a little bit crazy.”

– Jerry

“Ordinary people don’t know much about conlangs; many don’t even know

they exist. In general, conlangers are considered as dreamers, wackos and the

like.”

-Jorge

2.1 Number and distribution of speakers

A main problem facing anyone conducting a study of Esperanto is the need to

provide a rough count of its speakers. Numbers range from tens of thousands to tens

of millions, often depending on whether the researcher is opposing or promoting

Esperanto. Renato Corsetti, in 1996, presents estimates ranging between 50,000 and 8

to 15 million (1996: 265). Müller and Benton, writing in 2006, estimate that

Esperanto speakers number more than 100,000 (2006: 173). Fiedler, also writing in

34

2006, cites estimates ranging from 500,000 to 3.5 million (2006: 74). Ulrich Becker

explains the difficulty behind generating an accurate count:

Most of the speakers of Esperanto are unknown and do not appear in any kind

of statistics. It is not possible to count people who have studied, say, French,

unless they become members of a linguistic or cultural francophone society or

study the language in school. The same is true for Esperanto. One can count

only members of local, regional, national, and international organizations and

subscribers to periodicals. … The relatively small number of some ten

thousand active members of the Esperanto community … does not reflect the

actually much larger number of people who speak Esperanto, who use it only

sporadically, and do not appear in any sort of statistics (2006: 272-273).

Becker calls this a “twilight zone in the statistics” (2006: 273). But, researchers are

not the only ones who have trouble finding Esperanto speakers. Despite the networks

that connect active Esperantists to each other, it can be difficult to find a way in13.

Joel, who studied Esperanto on his own, recalls, “little by little I uncovered that …

there were indeed people who spoke this language … and that there were

organizations and there were conventions.” Like an anthill, once the concealing

surface is brushed away, an enormous, bustling community is uncovered. For

speakers, that means sudden access to conversation groups, pen-pals, literature, travel

accommodations, and more. For a researcher, however, that means insight, but still an

incomplete picture.

Because speakers cannot be accurately counted, their distribution can also not

be accurately measured. However, as Becker indicates, membership in Esperanto

13 When I began my research, I found a few local listings and thought it would be easy to get in touch

with at least a handful of Esperanto enthusiasts. The contact information I found, however, turned out

to be a dead end. Websites had expired and emails bounced back. Could it be that these Esperanto

groups had fallen apart, or was it that they had just fallen away from publicizing themselves on the

Internet? Either way, I feared I was about to experience what most Esperanto researchers assert:

Esperantists are hard to find. However, networking revealed a sure contact, and after an email to him,

my inbox was suddenly flooded with messages from potential participants, and I no longer worried

whether my entire thesis might collapse in the absence of participants. Within the next few days I was

receiving emails from as far as Canada, Switzerland, and a kibbutz in Israel.

35

organizations can be used as an indication, though it must be emphasized that

numbers generated that way are in no way comprehensive. In 1985, membership in

the Universal Esperanto Association was 82% European (Fettes 1996: 55). In 2006,

“the Universal Esperanto Association (UEA), the largest international Esperanto

organization, shows that the national associations have a total of some 23,254

members, while the UEA itself has 7,075 individual members in 119 countries”

(Becker 2006: 272). According to Esperanto-USA, in 2008 there were 633 registered

members, with an average of 11.7 members per state (Membership by State):

36

Chart 2.1.1: Published Esperanto-USA Membership,

by State, in 2008

State

Alabama

Alaska

Arizona

Arkansas

California

Colorado

Connecticut

Delaware

District of Columbia

Florida

Georgia

Hawaii

Idaho

Illinois

Indiana

Iowa

Kansas

Kentucky

Lousiana

Maine

Maryland

Massachusetts

Michigan

Minnesota

Mississippi

Missouri

Montana

Registered

Members

4

4

13

7

111

12

5

2

2

18

11

2

3

16

10

4

1

2

2

5

22

18

16

11

2

12

2

State, continued

Nebraska

Nevada

New Hampshire

New Jersey

New Mexico

New York

North Carolina

North Dakota

Ohio

Oklahoma

Oregon

Pennsylvania

Puerto Rico

Rhode Island

South Carolina

South Dakota

Tennessee

Texas

Utah

Vermont

Virginia

Washington

West Virginia

Wisconsin

Wyoming

Unknown addresses

Other countries

Total

Registered

Members

7

6

5

11

8

48

15

0

21

7

14

14

1

1

3

1

8

35

5

2

11

31

1

16

2

24

19

633

Research participants primarily reside in the United States: Atlanta, Georgia

(2); Oakland, California; Cincinnati, Ohio; Milwaukee, Wisconsin; Madison,

Wisconsin. Other participants reside in Montreal, Quebec, Canada (4); Sweden,

Brazil, and the Ukraine. Two of the Quebec residents were originally from Croatia

37

and the Ukraine14. Most of the participants have interacted with Esperantists from

other countries, either through sustained correspondence, personal travel, travel using

Pasporta Servo, or while attending Esperanto conventions. Through these means,

participants have interacted with Esperanto speakers from over 25 other countries,

including: Tanzania, South Africa, Nigeria, Mexico, Cuba, Chile, Korea, Vietnam,

Hong Kong, China, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Nepal, Belgium, Slovenia, Russia,

Bulgaria, Germany, Hungary, the United Kingdom, Poland, Portugal, and France.

Almost all participants, when speaking of Esperantists who were foreign with respect

to themselves, mentioned interacting with Esperantists from Japan and Brazil.

Another indication of the geographic spread of Esperanto speakers comes from the

website of Pasporta Servo, a networking service for Esperanto-speaking travelers,

which claims 1450 hosts from over 91 countries (Internacional Hospitality Service).

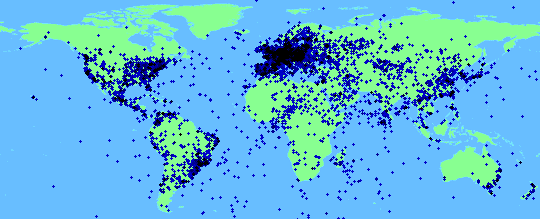

Figure 2.1.1: Lernu! Map of Registered Users (“Map”)

According to Bruce Arne Sherwood, “the highest density of speakers (as a

fraction of the total population) is found in East European countries, but West Europe

contributes the largest fraction of movement leadership” (1982: 1). It is logical that

14 See Chart 1.1

38

Europe has a particularly high density of Esperanto speakers, both because it is the

region where Esperanto originated, and because so many languages are spoken in

close proximity to one another. People are more likely to hear about Esperanto, and

more likely to see that it has immediate practical value. Still:

There are significant Esperanto activities in Asia, in Japan, China, South

Korea, and Vietnam. Numerically small but active groups of Esperanto

speakers are found in the Americas, particularly in Brazil, Canada, and the

United States. There are few speakers in Africa or the Middle East, except for

Iran and Israel (1982: 1,2).

While Europe might be, in terms of numbers, the locus of Esperanto activity,

other regions have notable Esperanto histories, particularly, Asia and Brazil. Because

I have nothing new to add to existing literature on this topic, I will not delve deeply

into the history of Esperanto in Asia, though, according to Ulrich Lins, “shedding

light on it in the East Asian context is particularly interesting because nowhere

outside Europe and the Americas has Esperanto been disseminated as much as it has

in China, Japan, and Korea” (2008: 47)15. Similarly, Mark Fettes points to

Esperanto’s “long history in Asia,” which is “often neglected in discussions of its

cultural and social significance” (2007: 15). Esperanto made its first appearance in

Japan in 1906, but it the radicalizing political climate of the late 1920s and early

1930s was particularly influential in its development. Left-leaning Esperantists

“sought to make use of Esperanto for a world revolution, and Ōshima Yoshio wanted

to “justify the Esperanto movement within the framework of Marxist theory”

15 For a frame of reference, consider the following: according to a ten-year survey from 1991 to 2000,

a Japanese publishing house published the highest number of pages of Esperanto text: 11,047. During

the same period, a Chinese publishing house, Ĉina Esperanto-Eldonejo, published the fifth-highest

number of titles: 47, but the second-highest number of pages: 9,152. In contrast, the US publishing

house with the highest number of Esperanto titles published 30, ranking tenth, and did not rank in the

top ten for number of pages (Becker 2006: 286).

39

(Hiroyuki 2008: 186). From Ōshima’s writings, Saitō Hidekazu developed a criticism

of linguistic imperialism, criticizing Japan’s language policy as a means of oppressing

“the working masses and the ethnic groups in the colonies” (Hiroyuki 2008: 187).

Then, in the late 1930s, Japanese police started persecuting left-wing Esperantists,

and center and right-wing Esperantists stepped forward, proposing Esperanto as a tool

to minimize “unnecessary hostilities of ethnic groups under Japanese rule” (Hiroyuki

2008: 187). After World War II, the political environment changed again:

It became less possible to dream of a world revolution or the “unification” of

Asian peoples under Japanese hegemony. … Whereas the prewar movement

consisted mainly of intellectuals from the upper and upper-middle classes, the

postwar democratization of the society and equitable redistribution of wealth

extended its composition to lower economic groups. The rank and file in the

postwar movement felt little need for a theoretical grounding for their

“beloved language.” For most of them, a vague commitment to

internationalism and pacifism was enough (Hiroyuki 2008: 187).

In the early 1900s in China, anarchists and reformists viewed Esperanto as a tool that

could contribute to China’s new place in the world, making it “a pioneer of a world

revolution bringing western and eastern cultures together” (Lins 2008: 48, 49).

However, in 1928, after the Kuomintang came to power and “began to deal more

harshly with anarchists,” Esperanto shifted from being “a device for obtaining

western knowledge” to a means for spreading China’s propaganda to the West (Lins

2008: 48). Ultimately, “the welfare of Chinese Esperantism was always tied to

political factors, whether the Esperantists wanted it or not,” and “Esperanto is back

where it started, dependent on the idealism of individuals” (Müller and Benton 2006:

184).

In “Esperanto, an Asian Language?” Mark Fettes examines Esperanto in Asia,

and its potential future there. “Every year for the past quarter-century, the so-called

40

Komuna Seminario has brought together young people from Japan, South Korea, and

more recently China, to explore their similarities and differences” (Fettes 2007: 14).

Participants are self-motivated, not compelled, invited, or organized by any

governmental or institutional force. They convene not merely to speak Esperanto, the

language they choose to share, but to share their perspectives on important cross-

national issues. Fettes quotes Kitagawa Hisasi, a participant in the first Seminario

who, at the conclusion of the meeting and discussion, “felt that the young Koreans

whom [he] met in the Seminario were all brothers and sisters in our human family,

with whom [he] would willingly remain friends” (Fettes 2007: 16). Rather than being

used in formal settings, Esperanto in modern Asia is used “for purposes that might

best be described as aesthetic: forging friendships, making music, discovering new

ways of looking at the world,” while English occupies the business sphere (Fettes

2007: 17). Still, Fettes observes that, “from the earliest years of Esperanto in Asia, the

language was associated with modernization, technical rationalism, and social