Tenata: A Constructed Language

Author: Lila Sadkin

MS Date: 06-01-2007

FL Date: 06-01-2015

FL Number: FL-00002D-00

Citation: Sadkin, Lila. 2007. «Tenata: A Constructed

Language.» FL-00002D-00, Fiat Lingua,

Copyright: © 2007 Lila Sadkin. This work is licensed under

a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-

NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

Fiat Lingua is produced and maintained by the Language Creation Society (LCS). For more information

about the LCS, visit http://www.conlang.org/

Tenata: A Constructed Language

Lila Sadkin

Introduction

Tenata (stress on the first syllable) is spoken in Southern

Korapan. Korapan is one of the countries on the continent

Atiensen. Tenata is a minority language on the continent, whose

name transliterates to Tinisen in Tenata, although the Tenata

people are not very involved in continental affairs, so the word

is rarely used. The Tenata people as a whole keep to themselves in

their region, although the network of villages is very dynamic,

and a person will usually have lived in several villages over her

lifetime.

Geographically, the area is mostly flatland, though there are

smaller mountains and forested areas in the east, and the climate

is temperate, with a fair amount of rain, lending itself

beautifully to agriculture. The region is dotted with variously-

sized villages, each predominantly self-sufficient, though they do

trade with each other, mostly for art and other specialties. Some

of the very small villages in an area will function as one

extended village. There is no central power in a village or any

collection of villages.

The main unit is a «collective» of people rather like a

family, but the word family is misleading here, because it does

not refer to relation by blood or marriage. The biological/marital

family does exist, but it isn’t the primary unit of identification

for an individual. A collective isn’t a fixed, permanant unit, but

rather changes from season to season. Each aspect of life’s tasks,

such as agriculture, production of household goods, and so forth,

are taken care of by a collective, which consists of the people

whose talents, knowledge, and ability equip them for the task at

hand. For example, during planting season a group will form around

each crop (in bigger villages) or a group of crops (in smaller),

and they will all live in the «collective house» until the

planting is completed. Planting is a community-wide affair and

other activities, aside from collective-internal recreation,

effectively cease. After all the planting for the season is done,

villages have a celebration which is also the dissolution of the

current collectives and the forming of new ones. Harvest season

works the same way. During the rest of the year, when there are

not community-wide tasks to do, most people live in the smaller

family-houses, rather than the collective-houses, though there are

still collectives that do various things such as taking care of

the animals, weaving, pottery, smaller gardening, academic

activities, and taking care of other aspects of life.

Young children generally stay with one of their parents in

the parent’s chosen collectives. Older children are free to choose

their own collective to participate in, and they are encouraged to

try out as much as they can to figure out what they have a passion

for.

The role of the elders is primarily education. They usually

«retire» when they feel ready, though retirement is not ceasing

work–it is a change from active participation in a collective

(though they certainly still can if they wish) to supervising and

instructing the children in the group as well as directing the

progress of the collective in general.

The impermanent nature of the collective is reflected in the

Tenata language, whose words are semantically flexible. The

speaker is free to use semantic suffixes and compounding to coax a

variety of shades of meaning from a single root. The language also

doesn’t make much distinction between nouns, verbs, adjectives,

and adverbs, choosing instead to pay more attention to the

difference between lexical (semantic) and grammatical categories.

Two important postulates in Tenata are validity and

responsibility. Validity appears predominantly as sentence-level

discourse particles. They indicate belief in the utterance and who

is doing the [non]believing. Responsibility appears in some of the

aspect morphemes in Tenata’s verbal inflection.

In Tenata, most parts of speech are bound. Compounding is

frequent and so words tend to be quite long. Sentences, on the

other hand, tend to be short. They have a minimum of three words

(occasionally two, within context that permits the dropping of

validity statements), and they rarely have more than fifteen,

although this is because of compounding.

Phonology

Tenata phonology is fairly simple. There are five phonemic

vowels and twenty-two phonemic consonants.

Vowels:

/i/ /e/ /a/ /o/ /u/

These have their traditional phonemic values.

Consonants:

/p/ /t/ /k/ /q/

/f/ /s/ /c/ /x/

/pf/ /ps/ /ts/ /tc/ /ks/ /kx/

/m/ /n/ /ny/ /ng/

/w/ /r/ /l/ /j/

Consonants are as in English except for the following:

/q/: uvular stop

/f/: bilabial fricative

/c/: palatal fricative

/x/: velar fricative

/ny/: palatal nasal

/j/: palatal glide

Stops are aspirated in stressed syllables, unaspirated

elsewhere.

Syllable Structure

A syllable has these possible forms:

CV(C)

[fricative][stop | glide]V(C)

[stop][glide]V(C)

Exceptions: /q/ and /x/ do not combine with any other

consonants.

A syllable can only end in a consonant if it’s the final syllable

in the morpheme: morpheme-internal syllable division always occurs

after a vowel, not after a consonant.

At morpheme boundaries, an additional unstressed vowel is

often inserted between morpheme-final and morpheme-initial

consonants, to break up clusters. This will always happen to

prevent the combination of two consonants with the same manner of

articulation, and often in other conditions as well, though

sometimes the two consonants remain adjacent. The inserted vowel

will always harmonize to the place of the preceeding vowel. In the

breakdowns for the examples, this vowel is indicated with .V.

Stress

The location of stress in a Tenata word depends on the

category of the word. Because Tenata’s parts of speech do not

correspond to English parts of speech, stress will be explained in

the section below.

The Categories of Tenata Summarized

Every Tenata sentence (with the exception of minimal answers

and other sentences within larger discourse structures) contains

at least three «words», or /-can-/. These three words must contain

the five parts of speech–/lume/, /teja/, /kowu/, /ngona/, and

/ruma/. Note: the previous words should actually be written with

hyphens, indicating that they are not free forms: /-lume-/, etc,

but for ease of reading they are written without the hyphens when

they are being used descriptively in the text.

In English, a complete sentence minimally consists of a noun

and a verb. Tenata does not make the same noun/verb distinction,

so a minimal sentence consists of a /-lumecan/, ‘semantic word’,

a /-ngonacan/, ‘verbal inflection word’, and /-rumacan/, ‘validity

word’.

What follows is an introduction to each category, and each

will be treated with more detail later.

/-lume-/ means ‘semantic root’ and so encompasses nouns,

verbs, adjectives, and adverbs. The same /lume/ can be used in any

of these categories, within semantic boundaries.

EXAMPLE: /-witena-/

noun: death

verb: to die

adjective: dead

adverb: deadly

EXAMPLE: /-kinya-/

noun: water

verb: to water

adjective: watery

adverb: in a water-like way, waterily, waterly

A /lume/ must always take /kowu/, function (case) prefixes, and

/teja/, categorical suffixes, to form a complete word that can be

used in a sentence.

/teja/ are categorical suffixes that always attach to /lume/.

They add further semantic information to the word and are never

optional. A particular /lume/ can take different /teja/ to

indicate different meanings, again within semantic boundaries.

EXAMPLE: /-kinya-/ ‘water’

/kinya.men/ ‘water.food’ «drinking water»

/kinya.mi/ ‘water.living’ «water» (not anthropomorphized,

often used when talking about a moving body of water such as a

river or stream)

/kinya.ci/ ‘water.human’ «water-demigod» (the person in

control of water)

/kinya.kim/ ‘water.building’ (used when speaking of

aquatic creatures’ living places)

There are also /teja/ that mean ‘art’, ‘tool’, ‘event’, and

others. More than one can also appear on a single /lume/ to make

further semantic distinctions.

/lume/ always have stress on their first syllable. In

compounds, the head of the compound, which is usually the final

/lume/, will have the primary stress.

/kowu/ are prefixes on /lume/ that mark functional roles in a

sentence, like case marking but with a few important distinctions.

These differences will be explained further in their own section.

There are nine /kowu/ and each /lume/ in a sentence must take one:

action, actor, recipient, beneficiary, purpose, direction,

location, instrument, auxiliary. Their functions will be explained

more thoroughly later. There is never stress on /kowu/.

/ngona/ are verbal inflection. They assemble to form a

separate word in a sentence. They collectively consist of mood and

three groups of contrasting aspects. The moods are indicative,

negative, interrogative, and hortative. The aspects are {for ones’

own benefit | for other’s benefit}, {intentional | accidental},

and {perfective | imperfective | habitual}. They are strung

together in this order, though the benefit and intention aspects

can be ommitted, and the benefit aspect can be replaced with a

pronoun, indicating the beneficiary (or maleficiary, with a

reversal suffix) directly. Stress in /ngonacan/ (the whole verbal

inflection word) is on the mood morpheme, word-initial.

/ruma/ are validity statements or discourse particles, and

indicate validity according to someone. They consist of two parts,

person and validity judgment. Person can be the speaker, subject,

a marked referent /lume/, common knowledge, a pronoun, or a fully-

inflected /lume/. Validity is true, unknown, or false, with

unknown being an end to itself, not a question left dangling, such

as the English «maybe.» /ruma/ is the last word in a sentence and

usually in conversation carries across sentences until it’s

changed. /ruma/ can also be suffixed onto /lume/, after /teja/,

particularly if the rest of the sentence is carrying a

different /ruma/. The stress in /rumacan/ is on the person, again

word-initial.

In addition to these five major categories, there are also

/feni/, conjunctions, and /jeso/, pronouns. /feni/ are the only

category in Tenata that can stand alone:

EXAMPLE: /-kajimekim tin -mosilimen/ «houses and fields»

Here the /feni/, /tin/, stands alone, without suffixes. They can

also be attached to /lume/. More examples are in the /feni/

section below.

/feni/ hold a special place in writing, and are often used in

writing where they aren’t used in speech, because the tokens for

them are repeated in writing where they aren’t in speech, and so

form aesthetically pleasing designs. /jeso/ can act in most

positions in a sentence, in place of /lume/ or in the /ngona/,

verbal inflection, or /ruma/, validity statement. /jeso/ are

further explained in their own section below.

There is also one morpheme, /x/, which is a reversal suffix.

It can attach to /lume/, /teja/, /ngona/, and /ruma/ and reverse

their meaning. It is most frequently used with /teja/ and /ngona/.

EXAMPLES:

/lume/: /-coref-/ ‘light’ /-coref.e.x-/ ‘dark,

extinguish’

/teja/: /-mi/ ‘living’ /-mi.x/ ‘not living’

/ngona/: /-xo/ ‘for one’s own benefit’ /-xo.x/ ‘for one’s

own detriment’

/ruma/: /-tus/ ‘true’ /-tus.u.x/ ‘not true’ This is

semantically different than /-tom/ ‘false’. /-tusux/ is more

uncertain and indicates an impermanent state: «Well, it’s not true

now, but maybe later it will be.»

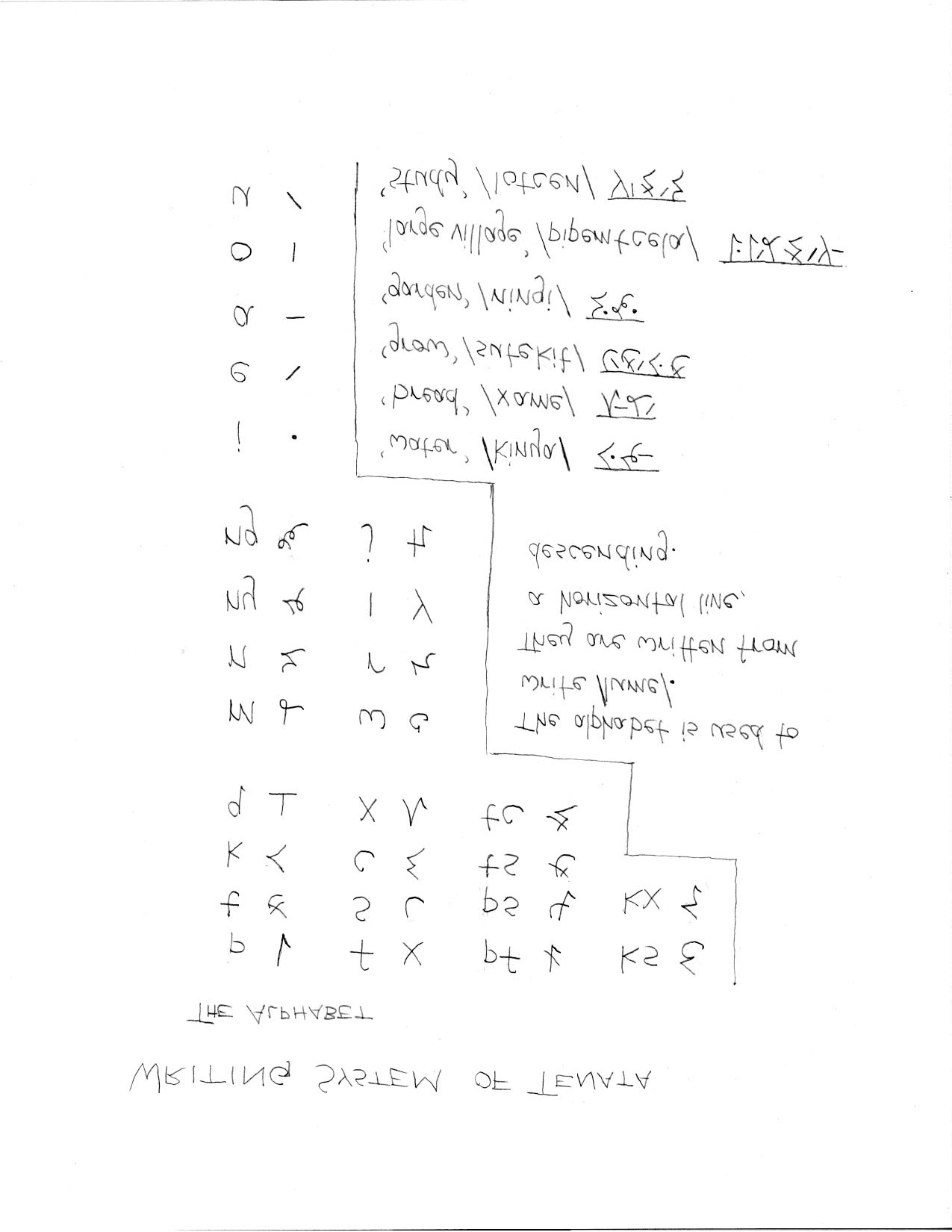

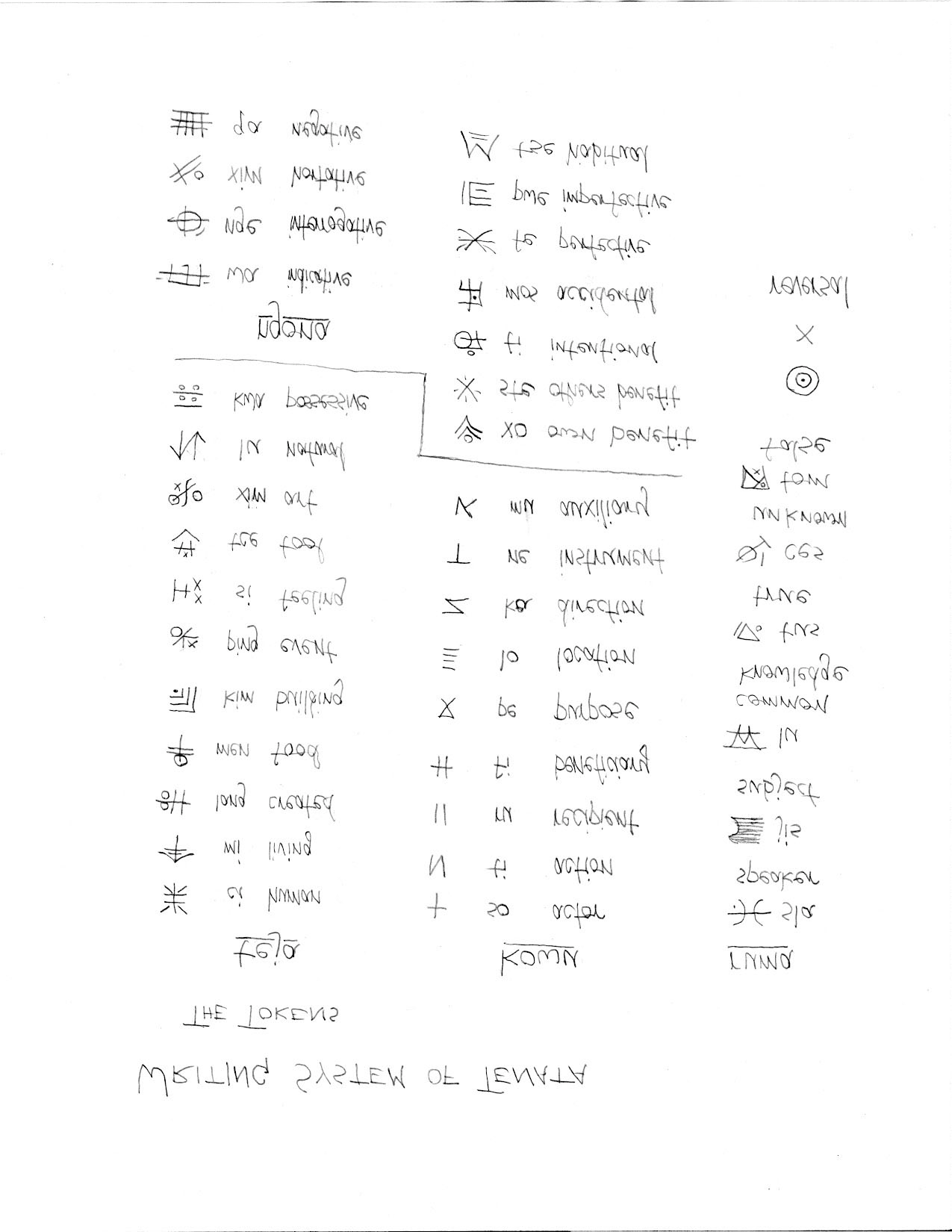

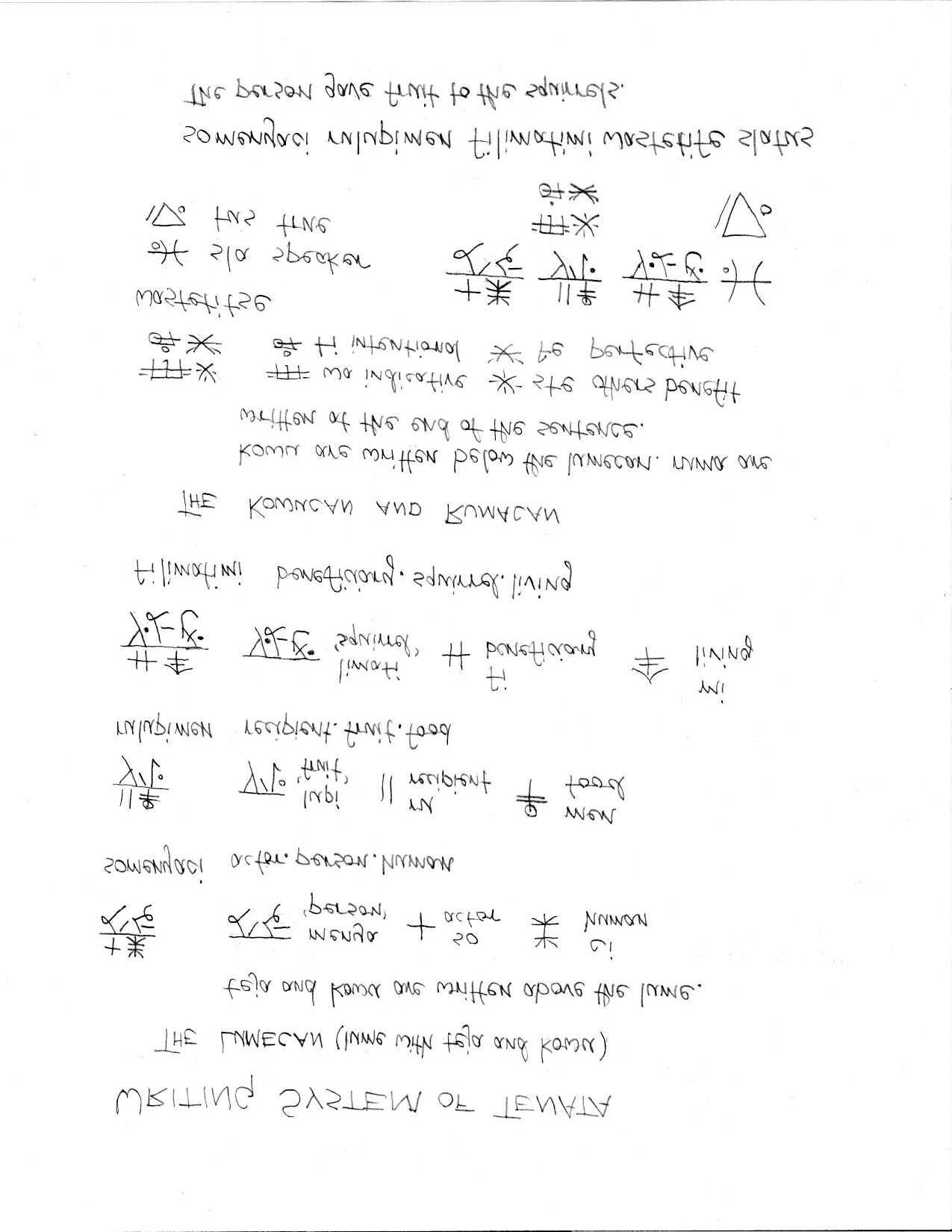

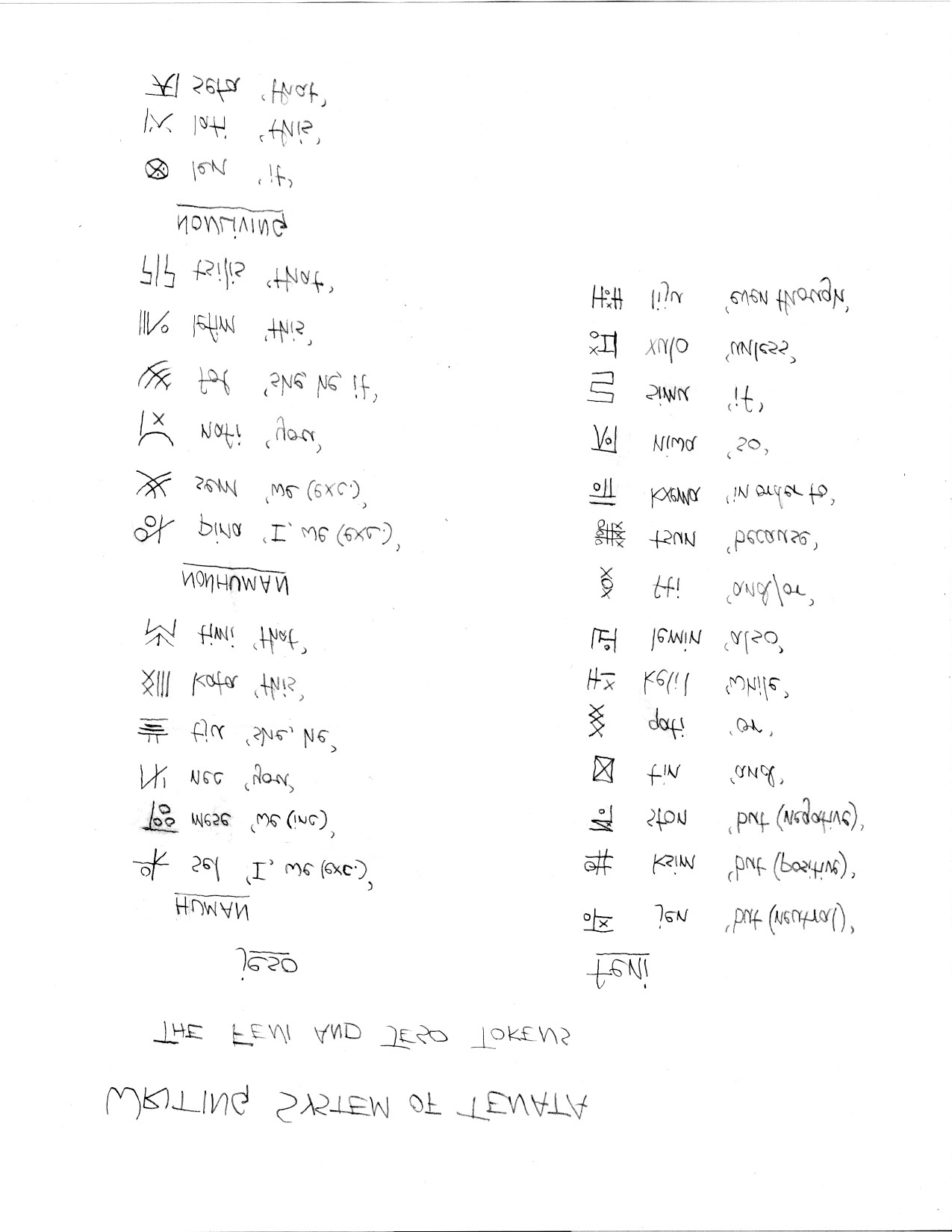

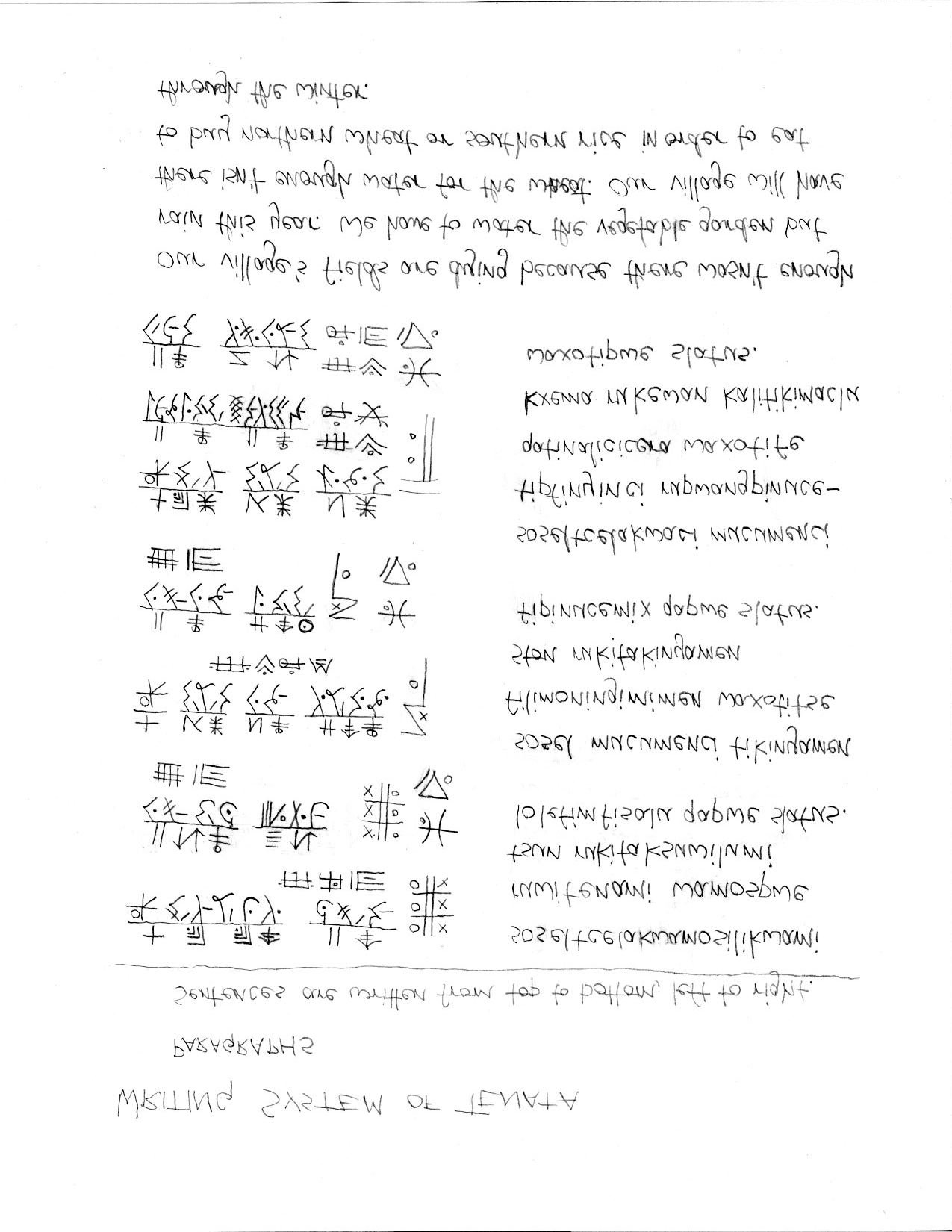

Writing System

Tenata has a two-part writing system that reflects the

distinction between lexical or semantic and grammatical

categories. /lume/ are written with a phonemic alphabet, while the

rest of the language, /teja/, /kowu/, /ngona/ and /ruma/, as well

as /feni/ and /jeso/, are written with unique, unanalyzable

tokens. The language is not written in single lines but rather in

blocks that correspond to sentences. Tenata writing does not

always correspond directly to speech. /feni/ are very frequently

repeated in writing, while they do not repeat in speech (except in

very stylized recitations), and the /kowu/ and /teja/ are often

repeated when a /feni/ is bound to a /lume/. A token can also

repeat to fill space when the writing is serving in an artistic

position. The Tenata people treat writing as art, and they take

the time to make even the most mundane writings beautiful. The

blocks are usually written in columns from left to right, but this

can be changed to fit circumstances, such as over doorways, which

is a common place to see writing. Note: the writing system is

detailed at the end of this paper.

/teja/ Categorical Suffixes

/teja/ bring subtlety to the language. They can act like

gender by linking words together in a phrase, but they are

different from grammatical gender in that a word, or more

precisely a /lume/, does not belong to a particular /teja/. Also,

unlike grammatical gender, they carry their own semantic meaning

that modifies the /lume/ rather than being assigned according to

the meaning of the root. The most commonly-made distinctions that

are made are human, living, humanmade, food, nature, and

building/living space.

/-mi/ living

/-ci/ human

/-men/ food

/-lang/ humanmade

/-lu/ nature

/-kim/ living space

Other frequent /teja/ are /-xin/, art; /-tcje/, tool; and /-ping/,

event. The /teja/ class is a partially open one. /lume/ can

become /teja/ when they are frequently used as the final /lume/ in

a compound.

EXAMPLE: The /lume/ /-menin-/ ‘food’ at some point became

the /teja/ /-men/ ‘food’. Interestingly, the /lume/ was not lost,

so this results in the word /-menin.i.men/.

There is also a /teja/ that is used in possessive phrases.

Possession is formed by compounding, which is explained later, and

also requires the /teja/ /-kwa/ which indicates being

possessed. /-kwa/ is also the /teja/ that is used as a citation

form for /lume/. Being possessed is a natural state in Tenata

thought, and possessives are very common where in English

possessives are highly marked. Certain /lume/ almost always appear

with this /teja/.

EXAMPLES:

/-fisan-/ ‘help’ /-fisan.kwa/ ‘help.poss.’

/so.tju ru.fisan.kwa fi.sel/

«She helps me.» A more literal translation: «She gives

her help to me.»

More than one /teja/ can be used on a /lume/.

EXAMPLE: /-nitil-/ ‘berry’

/-nitili.mi.men/ ‘berry.living.food’ This would be

berries still on the bush, but that will be eaten. It contrasts

with /nitilimi/ which are berries on the bush but that won’t be

used as food, or /nitilimen/ which are berries for eating that

have already been picked.

EXAMPLE: /-numela-/ ‘forest’

/-numela.mi.kim/ ‘forest.living.building’

/kowu/ Function Prefixes

/kowu/ mark the functional role of each /lume/ in a sentence.

Any /lume/ (within semantic restrictions) can fill any role in a

sentence, and each role is marked with a prefix. A /lume/ can only

take one /kowu/. There are eight basic roles in Tenata, as well as

an auxiliary role.

actor

action

/so-/

/ti-/

recipient

/ru-/

beneficiary

/fi-/

purpose

location

/pe-/

/lo-/

direction

/ka-/

instrument

/ne-/

auxiliary

/mu-/

These labels work better for Tenata than the traditional labels

used to describe, for example, the Latin case system: nominative,

accusative, genitive, and so forth, because the uses of these are

not identical. The biggest difference is that action is not marked

any differently than any other function, and /ti-/, action, isn’t

required in a sentence. Another important point is that they are

always referring to the action of the clause, rather than

modifying other /lume/. Modification is done with compounding

rather than with /kowu/, and will be discussed later. Note: The

following examples are not full sentences, as they lack /ngona/,

verbal inflection, and /ruma/, validity.

/so-/, actor

The /lume/ marked /so-/ carries out the action in a sentence,

whether or not /ti-/ is present. Most sentences have this /kowu/

on one of its /lume/, but there are exceptions: the actor can be

omitted if it is the same over multiple sentences. This is very

commonly done in storytelling. This /kowu/ is essentially

equivalent to the subject case. The actor tends to appear near the

beginning of the sentence.

/ti-/, action

The action in a sentence looks just like any other /lume/,

taking the /ti/ prefix and a suitable categorical suffix. More

abstract actions will often take /-kwa/, the possessed suffix,

or /-ping/, the event suffix. A sentence does not have to have

a /lume/ marked /ti-/–the action in a sentence can be indicated

by the other elements in the sentence, through the “natural

states” in Tenata, explained below. The /lume/ marked with /ti-/

is usually the last /lume/ in the sentence.

/ru-/, recipient

Recipient in Tenata is the recipient of the action in a

sentence.

EXAMPLE: /so.limati.mi ru.kelmi.mi ti.pseta.mi/

‘actor.squirrel.living recipient.tree.living

action.climb.living’

“The squirrel climbed the tree.”

The climbing happened to the tree, it was done to the tree by the

squirrel. Tenata actions always act upon something: a /lume/

marked /ti-/ cannot act as an intransitive verb. While /ti-/ isn’t

required in a sentence, /ru-/ always is. It is the inflection that

will appear on a sentence containing one /lume/:

EXAMPLE: /ru.ksuwi.lu/

‘recipient.rain.nature’

“It rains” or “There is rain” or “Rain was given.”

EXAMPLE: /so.pinuce.mi ru.kewan.men/

‘actor.wheat.living recipient.nourishment.food’

«The wheat gives/has nourishment» or «The wheat is

nourishing.»

«A is B» sentences are formed with the /ru-/ prefix.

EXAMPLE: /so.sel ru.menya.ci/

‘actor.I recipient.person.human’

«I am a person.»

/ru-/ is not equivalent to direct object or accusative case,

because there are circumstances in which a /lume/ marked with

/ru-/ acts as the “verb” in the sentence as well as its direct

object. This is the Tenata “natural state.” A /-lumetejacan/

(compound of /lume/ and /teja/ with a categorical suffix /-can/,

meaning ‘language’ or ‘word,’ which translates roughly to ‘word’

itself) can act as a noun and a verb simultaneously, where the

verb is the natural state, or the expected action of the noun.

Rivers flow, food is eaten, plants grow. When there isn’t an

identifiable «verb» in a sentence it is usually the natural state

of the recipient, marked /ru-/, such as in the following

sentences. There is no word that means “give” or “have” in Tenata.

This is another aspect of natural states, relating to the state of

possession that /lume/ rest in. In a sentence without a /lume/

marked /ti-/, the action is often “give” or “have.»

EXAMPLE: /so.menya.ci ru.kinya.men/

‘actor.person.human recipient.water.food’

“The person drinks water.”

EXAMPLE: /so.menya.ci ru.ningi.mi.men/

‘actor.person.human recipient.garden.living.food’

“The people grow a garden” or “The people have a garden”

or “The people garden.”

/fi-/, beneficiary

The beneficiary in a Tenata sentence is whom the action

affected or was directed toward. This includes the English

indirect object:

EXAMPLE: /so.menya.ci ru.ninigi.mi.men fi.tsofi.mi/

‘actor.person.human recipient.garden.living.food

beneficiary.birds.living’

“The people grow a garden for the birds.”

/fi-/ also works differently within the Tenata framework,

where it acts more like the English direct object:

EXAMPLE: /so.menya.ci ru.kinya.men fi.kelmi.mi/

‘actor.person.human recipient.water.food

beneficiary.trees.living’

“The person waters the trees.”

In the English sentence, “person” is the subject, “waters” is the

verb and “trees” is the direct object. In the Tenata sentence,

“person” is the subject, “water” is the object, and “trees” is the

beneficiary of the hidden action, “give.” A better translation

would be “The person gives water to the trees.” This differs from

the following sentence:

EXAMPLE: /so.ksuwi.men ti.kinya.men ru.pinuce.mi/

‘actor.rain.food action.water.food

recipient.wheat.living’

“The rain waters the wheat.”

In this sentence, “rain” is the subject, “waters” is the action,

and “wheat” is the recipient of the action. The rain is performing

the action of watering, rather than giving, while the person in

the previous example was giving. /so.menya.ci/ /ru.pinuce.mi/

/ti.kinya.men/ ‘actor.person.human’ ‘recipient.wheat.living’

‘action.water.food’ “The person waters the wheat” is also

grammatical, but the /ti-/ /ru-/ construction is less common than

the /ru-/ /fi-/ construction for sentences in which the subject is

providing something for something else’s benefit.

/pe-/ purpose

/pe-/ indicates the purpose of the action. A sentence with a

word marked with /ti-/ is more likely to have an accompanying

/pe-/ word, while sentences utilizing natural states, those with

only /ru-/, are less likely to include /pe-/, purpose. /lume/ that

take /pe-/ often also take the /teja/ /-ping/, event.

EXAMPLE: /so.tju ru.xame.men.lang pe.tcesala.ping/

‘actor.she recip.bread.food.created purpose.party.event’

“She made bread for the party.”

Aside from the /pe- -ping/ construction, there is also another

interesting aspect to this sentence. “bread” is marked with

/-men/, food, and /-lang/, created. This determines that the

natural verb in the sentence is “make” because the /-lang/ is

included. Bread is of course a humanmade thing, and so in other

contexts /-lang/ is usually not specified, but in this case, the

making is the reason for the sentence, so /-lang/ is used. The

sentence /sotju ruxamemen petcesalaping/ would mean “She brought

bread to the party.”

/lo-/ location

/lo-/ indicates the location of an action. It is only used

for static locations, such as “in the field” or “between the

houses” or “under the table.” It cannot be used for such locations

as “toward the river” or “around the tree” or “into the room,”

which include movement and are indicated with the direction

/kowu/, /ka-/.

EXAMPLE: /so.tju ru.limo.mi ti.situ.mi lo.ningi.lang/

‘actor.she recip.vegetables.living action.plant.living

location.garden.created’

“She planted vegetables in the garden.”

/lo-/ is also used to mark time in a sentence. The time

/lume/ will be marked with /lo-/.

EXAMPLE: /so.tcela.ci ru.pinuce.men ti.nyufim.ping

lo.lefim.i.fuceli.lu/

‘actor.village.human recip.wheat.food

action.harvest.event location.this.V.week.nature’

«The village harvests the wheat this week.»

/ka-/ direction

/ka-/ indicates the direction of the action. The presence

of /ka-/ indicates some sort of movement, and often marks the

/lume/ where the action ended up, rather than the static place

where the action started and finished, as marked by /lo-/.

EXAMPLES:

/so.sel ru.lesune.ping ka.tsipe.mi/

‘actor.I recip.walk.event direction.stream.living’

«I walked to the stream.»

/so.tsofi.mi ru.xulin.ping ke.tipa.lu/

‘actor.bird.living recip.fly.event direct.up.nature’

«The bird flies upwards.»

/ne-/, instrument

/ne-/ marks the instrument with which the action is

performed. It is also used to mark the attitude of the actor

toward the action or the quality of the action.

EXAMPLES:

/so.menya.ci ru.cu.mi ne.nyexom.tcu ti.situ.mi/

‘actor.person.human recip.seed.living instr.stick.tool

action.plant.living’

«The person planted seeds with a stick.»

/so.tsofi.mi ti.finge.lang ru.perami.kim ne.kxeneny.mi.x/

‘actor.bird.living action.build.created

recip.nest.building instr.straw.living.reversal’

«The bird built a nest with straw.»

/ne.sunyu.si so.masafi.ci ru.tju.fipemu.kwa.lang

ti.nestasa.lang/

‘instr.difficulty.feeling actor.child.human

recip.they.clothing.poss.created action.clean.created’

«With difficulty, the children washed their clothes.»

This example shows the flexibility of word order in Tenata. Any

/kowu/ at the beginning of the sentence except /so-/ and /ru-/ are

marked.

/mu-/, auxiliary

The auxiliary marks secondary actions in a sentence, such as

«want», «must», «like», «think», and other similar constructions.

When it is used, more attention is called to the word than if it

were compounded with the main action in the sentence, which is the

other way to form these kinds of sentences. /mu-/ often matches

with the /teja/ /-kwa/.

EXAMPLE: /so.masafi.ci mu.cumen.kwa ru.nipem.ci/

‘actor.child.human aux.need.poss recip.sleep.human’

«The children need to sleep.»

/mu-/ can also be used on other /lume/, where it indicates a

marginal association to the action. It is kind of like an

afterthought, «and besides» or «oh, and by the way,» and in this

case it usually appears before /ngonarumacan/, verbal inflection

and validity, at the end of the sentence.

EXAMPLE: /ru.tiqami.men ti.nyufimi.men fi.sel

mu.si.lestiku.men/

‘recip.herbs.food action.harvest.food benef.I

aux.one.tomato.food’

«Pick some herbs for me. Oh, and a tomato.»

Compounding

Compounding is very frequent and serves two important

purposes in Tenata. One is modification. /lume/ are not

specifically nouns or adjectives, verbs or adverbs. They can be

used as modifiers by compounding. The modifiers preceed the

head /lume/. The stress for a compound goes on the head /lume/,

though the other /lume/ may keep secondary stress on their first

syllable. Secondary stress is more likely to be significant in

longer compounds or less frequently occurring compounds, to help

distinguish the individual /lume/.

EXAMPLE: /-tcela-/ ‘village’ /-nalic-/ ‘south’

/-nalicitcela-/ «southern village» or «village to the

south of here»

EXAMPLE: /-fipemu-/ ‘clothing’ /-nestasa-/ ‘clean’

/-litiwa-/ ‘dry’

/-nestasalitiwafipemu-/ «clean, dry clothing»

EXAMPLE: /-nestasa-/ ‘clean’ /-kotse-/ ‘busy’

/-kotsenestasa-/ «busily cleaning»

EXAMPLE: /-kotse-/ ‘busy’ /-soxang-/ ‘use’ /-x-/

reversal /-soxangax-/ ‘useless’

/-soxangaxakotse-/ «uselessly busy» or «unnecessary

busywork»

Compounding is also used for possessives. The possessor

precedes the possessed, and the whole compound takes the /teja/

/-kwa/ to indicate possession.

EXAMPLE: /-kelmi-/ ‘tree’ /-feja-/ ‘leaf’

/-kelmifeja-/ «tree leaves»

/-kelmifejakwa/ «tree’s leaves»

EXAMPLE: /-menya-/ ‘person’ /-kajime-/ ‘house’

/-menyakajime-/ «person house»

/-menyakajimekwa/ «person’s house»

A compound word, whether it’s a possessive or a modified

phrase, still takes /kowu/ and /teja/, just like a single /lume/.

They function just like a single /lume/ in a sentence, filling any

role available semantically.

EXAMPLES:

/so.nec ru.nestasa.litiwa.fipemu.lang/

‘actor.you’ ‘recip.clean.dry.clothing.created’

«You have clean dry clothing.»

/so.nira.limati.mi ru.foning.lupi.men ne.pipem.sunyu.si

ke.folo.weta.kwa.kim ti.jasan.pesali.men/

‘actor.small.squirrel.living recip.fruit.food

instr.large.difficulty.feeling direct.it.home.poss.building

action.slow.carry.food’

«The small squirrel slowly carried the sweet fruit to its

home with much difficulty.»

/jeso/

/jeso/ are pronouns and demonstratives. Tenata has three

categories of pronouns and demonstratives: human, nonhuman, and

nonliving. The first two categories are divided into four persons,

while the third has only one person.

Human

/sel/ ‘I, we exclusive’

/mese/ ‘we inclusive’

/nec/ ‘you’

/tju/ ‘she/he’

/kata/ ‘this’

/timi/ ‘that’

Nonhuman

/pina/ ‘I, we exc.’

/sem/ ‘we inc.’

/nafi/ ‘you’

/fol/ ‘she/he/it’

/lefim/ ‘this’

/tsilis/ ‘that’

Nonliving

/len/ ‘it’

/lati/ ‘this’

/seta/ ‘that’

/jeso/, when replacing /lume/ in a sentence, must take /kowu/

just like the /lume/. However, they do not need to take /teja/, as

the basic categories of human, nonhuman, and nonliving, are

already marked. However, the nonhuman and nonliving demonstratives

often do take /teja/, especially if they are used to replace

/lume/ marked /-men/ or /-lang/, as these are frequently used

categories, and especially when they take the /kowu/ /ru-/,

because the meaning of the sentence can change depending on the

/teja/.

EXAMPLES:

/so.sel ru.len.men/

‘actor.I recip.it.food’

«I ate it.»

/so.mese ru.len.lang/

‘actor.we recip.it.created’

«We made it.»

Tenata has a strong storytelling culture, and this is where

the ‘I’, ‘we’, and ‘you’ nonhuman pronouns are used extensively.

Most stories are told in first person, from the perspectives of

the characters in the story, rather than in third person, about

the characters, although storytellers will often interject their

own thoughts into the story during the telling, and make comments

on them with /ruma/.

EXAMPLES:

/so.pina lo.mosili.lang ti.sutekit.imi/

‘actor.I(nonhuman) location.field.created

action.grow.living’

«I grew in the field.»

/so.nec ru.pina.men ti.nyufimi.men/

‘actor.you(human) recip.me.food action.harvest.food’

«You harvested me.»

/so.pina ru.weta.kim lo.kelmi.mi ti.finge.lang/

‘actor.I recip.home.building location.tree.living

action.build.created’

«I built a home in the tree.»

/ngona/ Verbal Inflection

/ngona/ are verbal inflection, and they form a separate word

in a sentence. /ngona/ includes aspect and mood, but, notably, not

tense. Time is indicated with time /lume/ and not marked with

verbal inflection at all. In discourse it’s often mentioned once

and not again until it changes. Sometimes, if it’s semantically

significant, it will be mentioned more often, and it’s more

commonly used in stories, which often have a more structured,

formal tone. /ngona/ can be ommitted in speech if they are

identical in a series of sentences, in which case the last one

would include the /ngona/. They will rarely be ommitted in

writing. Note: The following examples, unlike the previous ones,

are complete, fully-inflected sentences.

Mood

Tenata has four moods:

/wa-/ indicative

/nge-/ interrogative

/xim-/ hortative

/qa-/ negative

One of these is always the first morpheme in the /-ngonacan/, or

verbal word. They can occasionally be the only /ngona/ present in

a sentence, but it’s more rare and usually only in storytelling.

They otherwise will always have aspect morphemes suffixed to them.

/wa-/ indicative

/wa-/ is naturally by far the most frequent mood. It is used

for statements of fact, opinion, and speculation alike, although

the /ruma/ used with each of these will differ.

/nge-/ interrogative

/nge-/ is used for questions in which the action of the

sentence is being questioned. /rume/ is used for other kinds of

questions, where it is not the /lume/ marked /ti-/ or /ru-/ that

is being questioned.

/xim-/ hortative

/xim-/ is used for asking someone to do something. It

replaces an imperative mood, because Tenata culture does not give

orders. It can be translated as an imperative, but it’s definitely

not ordering but encouraging. The Tenata people will confirm that

they cannot force anyone to do anything, so /xim-/ is a hortative

mood.

/qa-/ negative

/qa-/ is used to form a negative sentence, negating the

action in a sentence. Individual words can be negated with the

reversal suffix, /x/, but whole sentences are negated by using the

negative mood.

EXAMPLES:

Sotsofimi ruxamemen waxotitse slatus.

so.tsofi.mi

ru.xame.men

actor.bird.living

recipient.bread.food

wa.xo.ti.tse

sla.tus

ind.own-benefit.intent.habitual

speaker.true

«The bird eats bread.»

Sonec rukewanmen fimasafaci ngetjutife nectus.

so.nec

ru.kewan.men

actor.you

recip.nourish.food

fi.masaf.a.ci

benef.child.V.human

nge.tju.ti.fe

nec.tus

inter.they.intent.perf

you.true

“Did you feed the children?”

Somasafici tipesalikwa ruxamemen kakajimekim ximinectife

nectus.

so.masaf.a.ci

ti.pesali.kwa

ru.xame.men

actor.child.V.human action.carry.poss

recip.bread.food

ka.kajime.kim

xim.i.nec.ti.fe

nec.tus

direct.house.build hort.V.you.intent.perf

you.true

«Child, please bring the bread to the house.»

Ruksuwilu qapwe mesetus.

ru.ksuwi.lu

qa.pwe

mese.tus

recip.rain.nature

neg.imperf

we.true

“There hasn’t been rain.”

Aspect

Tenata has three categories of aspect. The members of a

category cannot appear together in one /ngonacan/, so at most one

from each category can be used.

Benefactive

/-xo-/ for one’s own benefit (refers to the actor in the

sentence)

/-ste-/ for other’s benefit

A pronoun can be used here in place of one of these to

directly indicate the benefactor.

Intention

/-ti-/ intentional

/-mos-/ accidental, incedental

Completion

/-fe-/ perfective

/-pwe-/ imperfective

/-tse-/ habitual

/-nic-/ unrealized (action has not actually occurred,

used as hypothetical or desired)

Aspect is applied in this order, although they may all not be

present. The most commonly omitted is benefactive, followed by

intention. Completion is rarely omitted.

EXAMPLES:

Sosel rupsomlang titifamlang waxoxomosfe slatus.

so.sel

ru.psom.lang

ti.tifam.lang

actor.I

recip.book.created action.lost.created

wa.xo.x.o.mos.fe

sla.tus

ind.owb.reverse.V.accidental.perf speaker.true

«I lost the book (accidentally, to my own detriment).»

Soqasefelang kakwaxilang ruwaksiping wamosfe slatus.

so.qasefe.lang

ka.kwaxi.lang

actor.glass.created

direct.floor.created

ru.waksi.ping

wa.mos.fe

sla.tus

recip.fall.event

ind.incident.perf

speaker.true

«The glass fell on the floor.»

Sotju rupanecemen wamecetipwe slatus.

so.tju

ru.panece.men

actor.she

recip.cook.food

wa.mece.ti.pwe

sla.tus

ind.we.intent.imperf

speaker.true

«She’s cooking for us.»

/ruma/ Validity Statement

The validity statement in Tentata indicates what the speaker

knows about the truth of her words. There are two parts in any

/rumacan/, person and validity.

Person:

/lu-/ common knowledge

/sla-/ speaker

/jis-/ subject (the actor in the sentence)

Pronouns can also be used to directly indicate

who is providing the validity statement.

Validity: /-tus/ true

/-ces/ unknown (an end in itself, not an

unanswered question, as with English “maybe”)

/-tom/ false

The /rumacan/ usually appears at the end of the sentence or

clause. If it is moved to the beginning of the sentence, it’s a

marked construction and indicates that the /ruma/ is different

than would have been expected.

EXAMPLES:

Sotju rukinyamen fiqetimi wastetife slatus.

so.tju

ru.kinya.men

fi.qeti.mi

actor.she

recip.water.food

benef.flower.living

wa.fe

sla.tus

ind.perfective

speaker.true

“She watered the flowers (I saw her do it).”

Slatom sotju rukinyamen fiqetimi wastetife.

sla.tom

so.tju

ru.kinya.men

speaker.false actor.she

recip.water.food

fi.qeti.mi

wa.fe

benef.flower.living ind.perfective

“I think she didn’t water the flowers (like she was

supposed to).”

This example in English uses an auxiliary verb, ‘think,’ while the

Tenata expresses this through /ruma/. The /rumacan/ is at the

beginning of the sentence, which makes the doubt of the statement

stronger.

Sotju rukinyamen fiqetimi wastetife jistus slatom.

so.tju

ru.kinya.men

fi.qeti.mi

actor.she

recip.water.food

benef.flower.living

wa.fe

jis.tus

sla.tom

ind.perfective

subject.true

speaker.false

“She says she watered the flowers (I don’t believe her).”

Like the previous example, the auxiliary verb ‘says’ is

represented by /ruma/, in this case /jistus/. In English, an

intonation pattern would be used to indicate disbelief: «She SAYS

she watered the flowers.»

sotju rukinyamen fiqetimi wastetife slaces

so.tju

ru.kinya.men

fi.qeti.mi

actor.she

recip.water.food

benef.flower.living

wa.fe

sla.ces

ind.perfective

speaker.unknown

“She watered the flowers (but I can’t confirm that she

did).”

/ruma/ can also be used within a word, when there is a

separate /rumacan/ referring to the whole sentence, but a

particular part of it is different. /-tus/, /-ces/, and /-tom/ can

be suffixed to a /lume/, after /teja/, to indicate the belief

about that part of the sentence. This is how questions that are

not questioning the action but one of the other /lume/ in the

sentence are formed. The thing in question is marked with the

questioner’s belief about it, and indicates what answer is

expected.

EXAMPLES:

Sonececes tipanecmen petcesalaping wastetife nectus.

so.nece.ces

ti.panec.men

actor.you.unknown

action.cook.food

pe.tcesala.ping

purpose.party.event

wa.ste.ti.fe

nec.tus

ind.other-benefit.intent.perf

you.true

“Did you cook for the party?” (Someone cooked, was it

you?)

Sonec tipanecmen petcesalapingtom wastetife nectus.

so.nec

ti.panec.men

actor.you

action.cook.food

pe.tcesala.ping.tom

purpose.party.event.false

wa.ste.ti.fe

nec.tus

ind.other-benefit.intent.perf

you.true

“Did you cook for the party?” (Why did you cook? I don’t

think it was for the party.)

/ruma/ can also be used along with the interrogative mood. In

this case it appears on the action /lume/ and it indicates the

expected answer.

EXAMPLE:

Sonec tinestasalangtus runecefipemukimlang ngexotife

nectus.

so.nec

ti.nestasa.lang.tus

actor.you

action.clean.created.true

ru.nece.fipemu.kwa.lang

recip.you.clothing.poss.created

nge.xo.ti.fe

nec.tus

inter.own-benefit.intent.perf

you.true

“Did you wash your clothes? (I think you did.)”

/feni/ Conjunctions

/feni/ are conjunctions. They can act in two ways, linking

two or more /lume/ together, in which case they are bound in

between the linked /lume/. These two lume must have the same

/teja/. They can also link phrases containing more than one

/lume/, or complete sentences, including /ngona/ and /ruma/, and

in this case the /feni/ stands alone between the two phrases or

sentences.

EXAMPLE: /-qeti-/ ‘flower’ /-limo-/ ‘vegetable’ /tin/

‘and’

/-qetitinilimomi/ «flowers and vegetables»

In this example, note that the compound takes the /teja/ /-mi/,

‘living’. Though /-limo-/ might be able to take the /teja/ /-men/,

‘food’, in the case of direct linking, the two /lume/ must take

the same /teja/. If two words do not share the same /teja/, they

must be linked with independent /teja/.

EXAMPLE: /-qeti.mi tin -limo.men/

‘flower.living and vegetable.food’

«flowers and vegetables»

In this example, the conjunction stands alone. In writing, there

would be at least two /tin/ written, and even three. They would

surround the linked words, and often would be written larger than

the /lume/. There is a lot of flexibility in how they are written,

adding interest to the already artistic script.

EXAMPLE: /ru.kinya.men fi.kelmi.mi tin ru.lestiku.men

ti.nyufimi.men/

‘recip.water.food benef.tree.living and

recip.tomato.food’ action.plant.food’

«water the trees and plant the tomatoes»

In this example two phrases are linked without their /ngona/ or

/ruma/, so they must take the same ones:

sonec mufisanaci rukinyamen fikelmimi tin rulestikumimen

tinyufimping ximimesetife nectus

so.nec

mu.fisana.ci

ru.kinya.men

actor.you

aux.help.human

recip.water.food

fi.kelmi.mi

tin ru.lestiku.mi.men

benef.tree.living

and recip.tomato.living.food

ti.nyufim.ping

ximi.mese.ti.fe

nec.tus

action.plant.event hort.we.intent.perf

you.true

«Will you help water the trees and plant the flowers?»

There are four different /feni/ that translate as ‘but’:

/jen/ ‘but (neutral), but not (this but not that)’

EXAMPLE: /-tsofi.jen.cesiton.mi/

‘bird.but.fish.living’

«birds but not fish»

EXAMPLE: /ru.fipemu.lang ti.nestasa.lang jen

ru.limo.mi ti.kinya.men/

‘recip.clothing.created action.clean.created but

recip.vegetables.living action.water.food’

«wash clothes but not water the vegetables»

/ksim/ ‘but (positive)’

EXAMPLE:

Ruksuwilu qapwe ksim sotsetalang rukinyamen wapwe

lutus.

ru.ksuwi.lu

qa.pwe

ksim

recip.rain.nature

neg.imperf

but

so.tseta.lang

ru.kinya.men

wa.pwe

actor.well.created recip.water.food

ind.imperf

lu.tus

common-knowledge.true

«It hasn’t rained, but the wells have water.»

/ston/ ‘but (negative)’

EXAMPLE:

Sosel rumolilisi wapwe ston rumeninimen qapwe

slatus.

so.sel

ru.molili.si

wa.pwe

actor.I

recip.hunger.feeling

ind.imperf

ston

ru.menini.men

qa.pwe

but

recip.food.food

neg.imperf

sla.tus

speaker.true

«I’m hungry but don’t have food.»

Text with Translation/Analysis

Here is a line-by-line translation of a Tenata narrative.

This is in a casual speech style, which can be identified by

/ngonarumacan/ being occasionally dropped where they are the same

as in previous sentences. First is the Tenata with morphemes

marked, the English morpheme-by-morpheme, and an English gloss.

This is followed by the entire Tenata, and finally the entire

English.

so.sel

actor.I

ka.sel.kawasa.kwa.ci

to.my.friend.poss.human who in.south.village.building

tja lo.nalici.tcela.kim

ti.weta.ci

action.home.human

wa.ti.pwe

ind.int.imperf

ti.tsili.ci

action.visit.human

lo.lani.ngixe.lu

in.before.day.nature

wa.xo.ti.fe

ind.owb.int.perf

sla.tus

speaker.true

«Yesterday I visited my friend who lives in a small village south

of here.»

so.tju.tin.cemo.kwa.ci

actor.she.and.family.poss.human

ru.qeti.mi

recip.flowers.living

fi.xaja.tcela.ci

benef.whole.village.human

ti.sutekiti.mi

action.grow.living

wa.tju.ti.pwe

ind.they.intent.imperf

«She and her family grow flowers for the whole village.»

ru.finyu.wen.lu

recip.summer.mid.nature ind.imperf

wa.pwe

niwa

so

ru.tju

recip.she

so.pipem.kotse.mi

actor.much.busy.living

wa.xo.ti.pwe

ind.owb.int.imperf

sla.tus

speaker.true

«It is midsummer, so she is very busy.» (much business has her)

so.qeti.mi

actor.flowers.living

ru.linpa.si

recip.readiness.feeling

pe.nyufim.ping

for.harvest.event

lo.tenyami.finyu.ngixi.lu

in.every.summer.day.nature

tin.lemin

and.also

ru.ksulim.qeti.mi

recip.night.flowers.living

pe.nyufim.ping

for.harvest.event

wa.ste.ti.pwe

ind.otb.int.imperf

tju.tus

she.true

«Flowers were ready to be picked and there were also night-

blooming flowers to pick.»

so.sel

actor.I

ru.fisan.ci

recip.help.human

fi.tju

benef.her

ne.xaja.sel.nyafa.kwa

instr.all.my.ability.poss

wa.ste.ti.pwe

ind.otb.int.imperf

sla.tus

speaker.true

«I helped her as best as I could.»

so.sel

actor.I

ru.witele.kwa

recip.permission.poss

pe.qeti.nyufim.ping

for.flower.harvest.event

qa.pwe

neg.imperf

ksim

but

ru.witele.kwa

recip.permission.poss

pe.kijana.tin.menin.pesali.lang

for.basket.and.food.carry.made

wa.pwe

ind.imperf

sla.tus

speaker.true

«I’m not allowed to pick flowers but I can carry baskets and

food.»

so.kise.ping

actor.work.event

ru.xasasin.ping

recip.fast.event

tsun

because

ne.sel.fisan.ping

inst.I.help.event

tju.tus

she.true

«She said the work went faster because I helped.»

so.tju

actor.she

mu.cumen.ci

aux.need.human

ru.nyufim.ngeste.mi.x

recip.harvest.part.live.reverse

ti.lunong.ping

action.set-aside.event

pe.litiwa.ping

for.dry.event

niwa

so

so.sel

actor.I

ru.ksulim.sengen.men

recip.night.meal.food

ti.panec.men

action.cook.food

kelil

while

so.tju

actor.she

ru.kise.ping

recip.work.event

wa.ste.ti.fe

ind.otb.int.perf

sla.tus

speaker.true

«She had to set aside part of the harves to dry, so I cooked

dinner while she worked.»

so.sel.tin.tju

actor.I.and.she

ru.pilifi.ci

recip.talk.human

«We talked.»

so.tsili.ping

actor.visit.event

ru.nucija.ping

recip.wonderful.event

wa.sel.mos.fe

ind.I.unint.perf

sla.tus

speaker.true

«The visit was wonderful for me.»

Sosel kaselkawasakwaci tja lonalicitcelakim tiwetaci watipwe

titsilici lolaningixelu waxotife slatus. Sotjutincemokwaci

ruqetimi fixajatcelaci tisutekitimi watjutipwe. Rufinyuwenlu wapwe

niwa rutju sopipemkotsemi waxotipwe slatus. Soqetimi rulinpasi

penyufimping lotenyamifinyungixilu tinlemin ruksulimqetimi

penyufimping wastetipwe tjutus. Sosel rufisanci fitju

nexajaselnyafakwa wastetipwe slatus. Sosel ruwitelekwa

peqetinyufimping qapwe ksim ruwitelekwa

pekijanatinimeninipesalilang wapwe slatus. sokiseping

ruxasasinping tsun neselfisanping tjutus. Sotju mucumenci

runyufimngestemix tilunongping pelitiwaping niwa sosel

ruksulimsengenmen tipanecmen kelil sotju rukiseping wastetife

slatus. Soseltintju rupilifici. Sotsiliping runucijaping

waselmosfe slatus.

Yesterday I visited my friend who lives in a small village south

of here. She and her family grow flowers for the whole village. It

is midsummer, so she is very busy. Flowers were ready to be picked

and there were also night-blooming flowers to pick. I helped her

as best as I could. I’m not allowed to pick flowers but I can

carry baskets and food. She said the work went faster because I

helped. She had to set aside part of the harvest to dry, so I

cooked dinner while she worked. We talked. The visit was wonderful

for me.

Endnote: On Conlangs

Constructed languages, or conlangs, are an interesting way to

explore linguistics. Linguistics approaches languages from the top

down, beginning with an existing human language and analyzing it,

breaking it down into its component parts. Furthermore, the

different areas of linguistics often work separately from one

another, so that we have studies of phonology, morphology, and

syntax that exist as separate entities rather than working

together to form a holistic view of a language. Sociolinguistics

seems even farther removed from these other areas, so that in

traditional theoretical linguistics, a language is pulled out from

its cultural context and loses its connection to its speakers.

Conlanging takes a different approach to language. Rather

than breaking down a language, it creates one from the bottom up,

starting with the basic components of language and using them to

create a unique system. The goal of conlanging is often to create

a fully-functioning language, but it can also be used more

limitedly, to explore a linguistic concept in a simple way,

because natural languages are very complex, so it is often

difficult to isolate one particular feature. A conlang can solve

this problem by being more simple than a natural human language so

that the feature in question is made clear.

A conlang is also often part of a con-world or a con-culture,

reinforcing the tie between language and culture. A conlang can

also explore linguistic ideas that do not exist in human

languages, and so expand linguistic boundaries, as in Amy

Thomson’s The Color of Distance, where shapes and patterns replace

sound and color is emotional intonation in an alien language.

Conlanging can complement linguistics by providing a different

perspective from which to explore language.

My purpose in creating this conlang, Tenata, was to explore a

language structure that was different from English and the other

familiar Indo-European languages. I began by identifying English

linguistic postulates that I did not want to have in Tenata. The

main ones that I wanted to try to eliminate were number, sex-based

gender, the absoluteness of ‘to be,’ and ranking/hierarchy. But a

language can’t be merely the absence of something, so the next

step, which actually occurred simultaneously, was creating a set

of linguistic principles to work from. One of the first things

that I wanted to do was to dissolve the lines between the parts of

speech that we too often take for granted. I initially wanted to

have a non-sex-based gender system. This evolved into /teja/,

which is not gender, but instead is a flexible categorizing

system. I found that this fits well with the flexibility of the

/lume/ system, and led me to another pervasive aspect of Tenata:

liquidity, or the way the language in my mind flows into sentences

rather than being blocks that are lined up just so. As I

continued, my writing system reflects this by being non-linear and

having its own rules that are related to but also in ways

different from the spoken language. Finally, I wanted to explore

the language from its own point of view, rather than imposing

English categories on a language that doesn’t have the same

categorical distinctions. This is how I settled on using Tenata

words to describe the language.

The whole conlanging process is a non-linear one. I found

myself going back to things I had thought were finished and

needing to change them because of a change I had made in a

different part of the grammar. The process emphasizes how language

is a complete system that needs to have all its parts working

together simultaneously in order to work. In conlanging, I can’t

decide that I want to work on my verbs first, and then I’ll do the

nouns, because in order to test my verbal paradigm I need

complements. The language needs to be imagined as a whole system

before the system can be built, and this requires a detour from a

linear way of thinking. This project has certainly influenced the

way I approach language and linguistics, and I believe that my

understanding of the way languages work has been enriched by this

process.

Bibliography

Meyers, Walter E. Aliens and Linguists: Language Study and Science

Fiction. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1980.

Elgin, Suzette Haden. A First Dictionary and Grammar of Láadan,

Second Edition. Madison, WI: The Society for the Furtherance

and Study of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Inc., 1988.

Elgin, Suzette Haden. Native Tongue. New York: The Feminist Press,

2000.

Elgin, Suzette Haden. The Judas Rose. New York: The Feminist

Press, 2000.

Elgin, Suzette Haden. Earthsong. New York: The Feminist Press,

2000.

Le Guin, Ursula K. Always Coming Home. Berkeley and Los Angeles,

CA: University of California Press, 2001.

Cherryh, C.J. Foreigner. New York: DAW, 2004.

Thomson, Amy. The Color of Distance. New York: Ace, 1995.

Silver, Shirly, and Wick R. Miller. American Indian Languages:

Cultural and Social Contexts. Tuscon, AZ: University of

Arizona Press, 2000.

Hardman, MJ. Aymara. N.p.: LINCOM EUROPA, 2001.

Rosenfelder, Mark. The Language Construction Kit. 1996.

http://www.zompist.com/kit.html