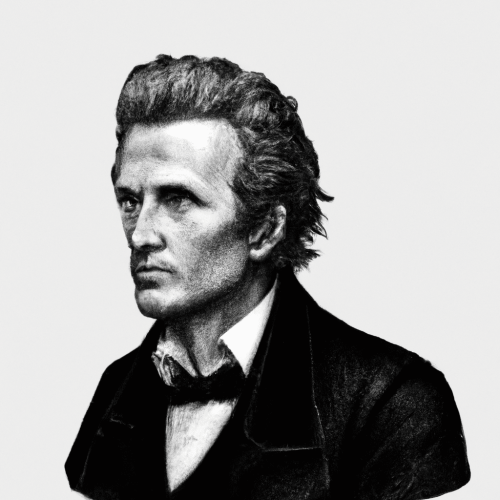

Søren Kierkegaard (1813—1855)

Søren Kierkegaard is an outsider in the history of philosophy. His peculiar authorship comprises a baffling array of different narrative points of view and disciplinary subject matter, including aesthetic novels, works of psychology and Christian dogmatics, satirical prefaces, philosophical “scraps” and “postscripts,” literary reviews, edifying discourses, Christian polemics, and retrospective self-interpretations. His arsenal of rhetoric includes irony, satire, parody, humor, polemic and a dialectical method of “indirect communication” – all designed to deepen the reader’s subjective passionate engagement with ultimate existential issues. Like his role models Socrates and Christ, Kierkegaard takes how one lives one’s life to be the prime criterion of being in the truth. Kierkegaard’s closest literary and philosophical models are Plato, J.G. Hamann, G.E. Lessing, and his teacher of philosophy at the University of Copenhagen Poul Martin Møller, although Goethe, the German Romantics, Hegel, Kant and the logic of Adolf Trendelenburg are also important influences. His prime theological influence is Martin Luther, although his reactions to his Danish contemporaries N.F.S. Grundtvig and H.L. Martensen are also crucial. In addition to being dubbed “the father of existentialism,” Kierkegaard is best known as a trenchant critic of Hegel and Hegelianism and for his invention or elaboration of a host of philosophical, psychological, literary and theological categories, including: anxiety, despair, melancholy, repetition, inwardness, irony, existential stages, inherited sin, teleological suspension of the ethical, Christian paradox, the absurd, reduplication, universal/exception, sacrifice, love as a duty, seduction, the demonic, and indirect communication.

Table of Contents

Life (1813-55)

Father and Son: Inherited Melancholy

Regina Olsen: The Sacrifice of Love

The Master of Irony and the Seductions of Writing

The “Authorship”: From Melancholy to Humor

The “Second Authorship”: Self-Sacrifice, Love, Despair, and the God-Man

The Attack on the Danish People’s Church

The “Aesthetic Authorship”

On the Concept of Irony and Either/Or

Fear and Trembling and Repetition

Philosophical Fragments, The Concept of Anxiety, and Prefaces

Stages on Life’s Way and Concluding Unscientific Postscript

The Edifying Discourses

Sermons, Deliberations, and Edifying Discourses

Direct and Indirect Communication

That Single Individual, My Reader

The “Second Authorship”

Works of Love

Anti-Climacus

The Attack on the Church

References and Further Reading

1. Life (1813-55)

a. Father and Son: Inherited Melancholy

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard was born on May 5th 1813 in Copenhagen. He was the seventh and last child of wealthy hosier, Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard and Ane Sørensdatter Lund, a former household servant and distant cousin of Michael Kierkegaard. This was Michael Kierkegaard’s second marriage, which came within a year of his first wife’s death and four months into Ane Lund’s first pregnancy. Michael Kierkegaard was a deeply melancholic man, sternly religious and carried a heavy burden of guilt, which he imposed on his children. Søren Kierkegaard often lamented that he had never had a childhood of carefree spontaneity, but that he had been “born old.” As a starving shepherd boy on the Jutland heath Michael had cursed God. His surname derived from the fact that his family was indentured to the parish priest, who provided a piece of the church (Kirke) farm (Gaard) for the family’s use. The name Kirkegaard (in older spelling Kierkegaard) more commonly means ‘churchyard’ or ‘cemetery.’ A sense of doom and death seemed to hover over Michael Kierkegaard for most of his 82 years. Although his material fortunes soon turned around dramatically, he was convinced that he had brought a curse on his family and that all his children were doomed to die by the age attained by Jesus Christ (33). Of Michael’s seven children, only Peter Christian and Søren Aabye survived beyond this age.

At age 12 Michael Kierkegaard was summoned to Copenhagen to work for his uncle as a journeyman in the cloth trade. Michael turned out to be an astute businessman and by the age of 24 had his own flourishing business. He subsequently inherited his uncle’s fortune, and augmented his wealth by some felicitous investments during the state bankruptcy of 1813 (the year, as Søren later put it, in which so many bad notes were put into circulation). Michael retired young and devoted himself to the study of theology, philosophy and literature. He bequeathed to his surviving sons Peter and Søren not only material wealth, but also supremely sharp intellect, a fathomless sense of guilt, and a relentless burden of melancholy. Although his father was wealthy, Søren was brought up rather stringently. He stood out at school because of his plain, unfashionable apparel and spindly stature. He learned to avoid teasing only by honing a caustic wit and a canny appreciation of other people’s psychological weaknesses. He was sent to one of Copenhagen’s best schools, The School of Civic Virtue [Borgerdydskolen], to receive a classical education. More than twice as much time was devoted to Latin in this school than to any other subject. Søren distinguished himself academically at school, especially in Latin and history, though according to his classmates he struggled with Danish composition. This became a real problem later, when he tried desperately to break into the Danish literary scene as a writer. His early publications were characterized by complex Germanic constructions and excessive use of Latin phrases. But eventually he became a master of his mother tongue, one of the two great stylists of Danish in his time, together with Hans Christian Andersen. Kierkegaard’s father is a constant presence in his authorship. He appears in stories of sacrifice, of inherited melancholy and guilt, as the archetypal patriarch, and even in explicit dedications at the beginning of several edifying discourses. Kierkegaard’s mother, on the other hand, never gets a mention in any of the writings – not even in his journal on the day of her death. His mother-tongue, though, is omnipresent. If we conjoin this fact with the remark in Concluding Unscientific Postscript (1846) that “… an omnipresent person should be recognizable precisely by being invisible,” we could speculate that the mother is even more present than the father, pervading all but the foreign language insertions in the texts. But whether or not there is any substance in this speculation, the invisibility of the mother and the treatment of women in general are indicative of Kierkegaard’s uneasy relationship with the opposite sex.

b. Regina Olsen: The Sacrifice of Love

Søren drifted into the study of theology at the University of Copenhagen, but soon broadened his study to include philosophy and literature. He started rather desultorily, and enjoyed a relatively dissolute time, even aspiring to cut the figure of a dandy. He ran up debts, which his father reluctantly paid, but eventually knuckled down to finish his degree when his father died in 1838. It seemed he was destined for a life as a pastor in the Danish People’s Church. In 1840, just before he enrolled at the Pastoral Seminary, he became engaged to Regina Olsen. This engagement was to form the basis of a great literary love story, propagated by Kierkegaard through his published writings and his journals. It also provided an occasion for Kierkegaard to define himself further as an outsider. For several years (at least since 1835) Kierkegaard had been dabbling with the idea of becoming a writer. The wealth he had inherited from his father enabled him to support himself comfortably without the need to work for a living. But it was not really enough to support a wife, let alone a wife and children. Furthermore, Kierkegaard harbored an undisclosed secret, something dark and personal, which he thought it his duty to confide to a wife, but which he dared not. Whether it was some sexual indiscretion, an inherited sexual disease, his innate melancholy, an egotistical mania to become a writer, or something else, we can only speculate. But when it came to the crunch, it seemed sufficient to make him break off the engagement rather than to reveal it to Regina. Thereafter, Kierkegaard frequently used marriage as a trope for “the universal” – especially for the universal demands made by social mores. Correlatively, becoming an “exception” was both a task and constantly in need of justification. The tortuous dialectic of universal and exception, worked out in terms of the sacrifices of love, subsequently informs much of Either/Or, Repetition, Fear and Trembling, Prefaces, and Stages on Life’s Way. A frequent foil for the trope of marriage as the universal is the figure of a young man “poeticized” by a broken engagement, who thereby becomes “an exception.” Only when the young man is “poeticized” in the direction of the religious, however, is there any question of his being a “justified exception.” Kierkegaard’s ultimate justification for breaking off his own engagement was his dedication to a life of writing as a religious poet, under the direction of divine Governance. As a measure of the importance the relationship to Regina had for his life, Kierkegaard adapted a line from Virgil’s Aeneid II,3 as “a motto for part of his life’s suffering”: Infandum me jubes Regina renovare dolorem (“Queen [Regina], the sorrow you bid me revive is unspeakable”).

c. The Master of Irony and the Seductions of Writing

During the period of his engagement Kierkegaard was also busy writing his Master’s dissertation in philosophy, On the Concept of Irony: with constant reference to Socrates (1841). This was later automatically converted to a doctorate (1854). Kierkegaard had petitioned the king to write his dissertation in Danish – only the third such request to be granted. Usually academic dissertations had to be written and defended in Latin. Kierkegaard was allowed to write his dissertation in Danish, but had to condense it into a series of theses in Latin, to be defended publicly in Latin, before the degree would be awarded. Almost immediately after his dissertation defense, Kierkegaard broke off his engagement to Regina. He then undertook the first of four journeys to Berlin – his only trips abroad apart from a brief trip to Sweden. During this first trip to Berlin Kierkegaard completed most of the first volume of Either/Or (much of the second volume already having been completed).

Throughout the second half of the 1830s Kierkegaard had aspired to become part of the pre-eminent literary set in Copenhagen. This centered on Professor J.L. Heiberg, playwright, philosopher, aesthetician, journal publisher, and doyen of Copenhagen’s literati. Heiberg had been credited with introducing Hegel’s philosophy to Denmark, though in fact there had already been lectures on Hegel by the Norwegian philosopher Henrik Steffens among others. Nevertheless, the fact that Heiberg gave Hegel’s work his imprimatur accelerated its acceptance into mainstream Danish intellectual life. By the end of the 1830s Hegelianism dominated Copenhagen’s philosophy, theology and aesthetics. Of course this engendered some resistance, including that from Kierkegaard’s professors of philosophy F.C. Sibbern and Poul Martin Møller. One of Hegelianism’s most illustrious local exponents was Kierkegaard’s archrival H.L. Martensen (professor of theology at Copenhagen University, later Bishop Primate of the Danish People’s Church). Martensen, just five years senior to Kierkegaard, was firmly entrenched in the Heiberg literary set, and anticipated at least one of Kierkegaard’s pet literary projects – an analysis of the figure of Faust. In his journals, as part of his practice at becoming a writer, Kierkegaard had been fascinated with three great literary figures from the Middle Ages, who he thought embodied the full range of modern aesthetic types. These figures were Don Juan, Faust, and the Wandering Jew. They embodied sensuality, doubt and despair respectively. Martensen’s publication on Faust pre-empted Kierkegaard’s budding literary project, though the latter eventually found expression in the first volume of Either/Or (1843). Meanwhile, Kierkegaard continued to seek Heiberg’s seal of approval. His first major breakthrough was an address to the University of Copenhagen’s Student Association on the issue of freedom of the press. This was a satirical conservative riposte to a previous address in favor of more liberal press laws, and was the first broadside by Kierkegaard in a long career of lambasting the popular press, especially insofar as it supported political agitation for democracy. In this instance, however, it seemed motivated more by a desire to showcase his wit and erudition than by any deeper engagement with the political issues. The freedom of the press had been severely undermined by King Frederik VI’s ordinance of 1799, and was threatened with full censorship by his press legislation of 1834. The Society for the Proper Use of Press Freedom was formed in 1835 to combat this development. Kierkegaard followed up his speech with an article in Heiberg’s paper, The Copenhagen Flying Post (1836). The article, published pseudonymously, was so clever and polished that some people mistook it for the work of Heiberg himself. This amounted to his calling card for invitation to the Heiberg literary salon. Kierkegaard followed this with further pseudonymous articles on the same topic. But his first monograph was a 70-page review of Hans Christian Andersen’s novel, Only a Fiddler. This too was a strategic move to break into the inner sanctum of Heiberg’s circle. Andersen was emerging as a major talent in Danish letters, having published poetry, plays and two novels, which had almost immediately been translated into German. Only a Fiddler was on a topic dear to Kierkegaard’s heart – genius. Andersen’s prime claim was that genius needs nurturing, and can succumb to circumstance and disappear without trace. Kierkegaard, in his book-length review From the Papers of One Still Living (1838), disagreed stridently, maintaining that the spark of genius could never be extinguished, but only augmented by adversity. Furthermore, he developed a theory of the novel in which he asserted that to be worth its salt, a novel had to be informed by a “life-view” and a “life-development.” He criticized Andersen’s novel for its dependence on contingent features from Andersen’s own life, rather than being transfigured by a mature philosophy of life with clarity of purpose. He contrasted Andersen’s novel unfavorably in this respect with the novel by Heiberg’s mother, Thomasine Gyllembourg, A Story of Everyday Life. Kierkegaard was to return to Gyllembourg as a novelist in his review of her Two Ages in A Literary Review (1846). He was also to write a review of the work of Heiberg’s wife Louise, Denmark’s leading actress, in The Crisis and A Crisis in the Life of an Actress (1848).

d. The “Authorship”: From Melancholy to Humor

Neither the articles in Heiberg’s papers, nor the monograph on Andersen as novelist had gained Kierkegaard secure membership of Heiberg’s circle – though he was an occasional visitor there. With the breaking of his engagement to Regina, the completion of a major academic book (The Concept of Irony), his decision to devote himself to writing, and the trip to Berlin both to audit Schelling’s lectures (along with Karl Marx, Jacob Burckhardt and other luminaries) and to concentrate on his new literary project (Either/Or), Kierkegaard was about to embark on what he later, retrospectively, called his “authorship.” This was eventually to comprise all the “aesthetic” pseudonymous works from Victor Eremita’s Either/Or to Johannes Climacus’s Concluding Unscientific Postscript, the Edifying Discourses under Kierkegaard’s own name (up to 1846), and Two Ages: The Age of Revolution and the Present Age: A Literary Review (by S. Kierkegaard). In short, these were the works published between Kierkegaard’s first and final visits to Berlin.

Either/Or burst upon the Copenhagen reading public with great force. It was immediately understood to be a major literary event. It was also regarded as scandalous by some, since its first volume portrayed the cynical, bored aestheticism of the modern flâneur, culminating in “The Seducer’s Diary.” Many, including Heiberg, took this to be a thinly disguised account of Kierkegaard’s own treatment of Regina Olsen. Most of the reviews, including Heiberg’s, concentrated on the scurrilous content of the first volume of the book. But other reviews read the two-volume work as a whole, and discovered the edifying and ethical framework in which the aesthetic point of view was to be assessed. Nevertheless, Heiberg’s review deeply offended Kierkegaard, and marked the point at which his relationship to Heiberg changed from aspiring associate to embittered critic. Hereafter in the “authorship” Heiberg became the target of unrelenting satire. He and Martensen were the main representatives of Danish Hegelianism, which is attacked at various points in the “authorship” – particularly in Prefaces (1844) and in Concluding Unscientific Postscript. It is worth noting that Hegel himself comes in for much less criticism, and much more positive endorsement, in Kierkegaard’s work than is commonly assumed. It is the Christian Hegelianism of Danish intellectuals that is the main target of his critiques. The “authorship” comprises two parallel series of texts. On the one hand are the pseudonymous works, which purportedly follow a dialectical trajectory of existential “stages” from the aesthetic, through the ethical, to the religious, and ultimately to the paradoxical religious stage of Christian faith. On the other hand are the Edifying Discourses, which are published under Kierkegaard’s own name, which resemble sermons on biblical texts, and which are addressed to a readership already presumed to be Christian. The pseudonymous authorship starts with an existential type modeled on the German Romantic aesthete – the ironic, urbane flâneur whose main concern is to avoid boredom and to maintain a cerebral spectator’s interest in life and its sensuous pleasures. Ironically, this aesthete is beset with melancholy. His greatest happiness is his unhappiness, as the section of Either/Or entitled “The Unhappiest One” concludes. Although boredom is stated to be the negative motivation for the aesthete’s actions, at a deeper level we can discern that it is escape from melancholy and despair that are the real motivators. As part of the dialectical framework of the “authorship,” Kierkegaard says there are also intermediate states between the discrete existential stages. These he calls “confinia” or border areas. Between the aesthetic and ethical stages lies the confinium of irony. Between the ethical and religious stages lies the confinium of humor. Humor is defined as “irony to a higher power” – so it does not wear its meaning on its sleeve. It is also to be understood as an inclusive, magnanimous state of affirming “both/and” (both the aesthetic and the ethical, both the tragic and the comic) rather than the ethically exclusive “either/or.” The author of Concluding Unscientific Postscript, Johannes Climacus is a self-professed “humorist” in this sense. Although he purports to give the reader the truth about Christianity, he also “revokes” all he has said in that book. The religious humorist purports to go beyond the aesthetic and the ethical by choosing the religious exclusively, yet by virtue of the absurd, gets the aesthetic and the ethical back again within the religious. In terms of his own psychological economy, Kierkegaard seems to have been struggling to lose his melancholy and have it at the same time. It seems to have served him as an essential motor of aesthetic productivity, but was also a constant source of suffering from which he sought escape. For a long time Kierkegaard reconciled himself to his life of aesthetic self-indulgence as an author with the idea that it was all for a limited time. Once his “authorship’ was complete, he would retire from writing and become a country pastor ministering to the souls of simple folk. Authorship was both a demonic temptation and a means of self-justification as an exception to the universal demands of society’s ethics. But just as he was on the point of completing the “authorship,” Kierkegaard managed to provoke an attack on himself by the press, which demanded further work as an author in response.

e. The “Second Authorship”: Self-Sacrifice, Love, Despair, and the God-Man

Kierkegaard provoked an attack on himself by the journal The Corsair. The journal, edited by the talented Jewish author Meïr Goldschmidt, specialized in ruthless satirical attacks on contemporary Danish authors. Yet, perhaps because of the esteem in which Goldschmidt held him, Kierkegaard had been spared. Kierkegaard found this favorable treatment offensive (partly out of vanity, ostensibly because of his ongoing critique of the press’s influence on public opinion). So he publicly challenged The Corsair to do its worst. It did. It launched a series of attacks on Kierkegaard, more personal than literary, and focused on his odd appearance and his relationship with Regina. In some wicked caricatures it portrayed him with one trouser leg shorter than the other, with a sway back, and riding on a woman’s (Regina’s) back with stick in hand. These caricatures made a laughing stock of Kierkegaard in Copenhagen, to the extent that he was mocked in the street and had to give up his habit of walking around the inner city to talk with all and sundry.

But it galvanized him to begin a “second authorship.” This time the edifying discourses under his own name were supplemented with works by the pseudonym Anti-Climacus. Anti-Climacus represents an idealized Christian point of view – one that Kierkegaard professed is higher than he had been able to achieve in his own life. The only other pseudonyms to appear in this “second authorship” were Inter et Inter, author of The Crisis and A Crisis in the Life of an Actress, and “H.H.” author of “Two Ethical-Religious Essays.” In addition the “second authorship” comprises: Works of Love (1847), The Sickness Unto Death (1849), Practice in Christianity (1850), as well as various edifying discourses, including Edifying Discourses in Various Spirits (1847), The Lily of the Field and the Bird of the Air (1849), Three Discourses at the Communion on Fridays (1849), Two Discourses at the Communion on Fridays (1851), and For Self-Examination (1851). He also published a retrospective self-interpretation of his writings to date, On My Work as an Author (under his own name – 1851). In addition Kierkegaard wrote various works at this time which he decided not to publish. The most significant of these are: The Book on Adler and The Point of View for My Work as an Author. The former gives a detailed analysis of the “phenomenon” of Adolph Adler, a pastor in the Danish People’s Church who claimed to have had a divine revelation. He was deemed mad by the church authorities and pensioned off. Adler had been a leading Hegelian in the 1840s, but on Kierkegaard’s analysis ends up being “a Satire on Hegelian Philosophy and the Present Age.” Kierkegaard makes an immanent critique of Adler’s writings to demonstrate their confusion and the absence of revelation. Kierkegaard published only the addendum to The Book on Adler as “The Difference between a Genius and an Apostle” in “Two Ethical Religious Essays.” The Point of View for My Work as an Author sets out Kierkegaard’s (retrospective) interpretation of his authorship. It is subtitled: “A Direct Communication, Report to History.” It explains in direct terms the dialectic of indirect communication, but Kierkegaard was uncertain whether its directness at that time was dialectically correct for the authorship and refrained from publishing it. The “second authorship” reintroduces various concepts from the “aesthetic authorship,” but “transfigured” by the light of Christian faith. One of the most significant of these is “despair,” which is a transfigured version of “anxiety.” Both concepts are illuminated by reference to the notion of sin, and both are constitutive of the dialectic of selfhood. Only by acknowledging our ultimate dependence on God’s grace is it possible to overcome despair, and to become a self (paradoxically by becoming as “nothing” before God). Another concept transfigured in the “second authorship” is “love.” In the “aesthetic authorship” “love” is understood in pagan terms, primarily as eros – or desire. Desire is preferential, based on a lack (we only desire what we don’t have, according to Plato’s Symposium), and is ultimately selfish. Christian love is understood as agape. It is self-sacrificing, directed to the neighbor (without personal preference), is conceived as a spiritual duty rather than a psychological feeling, and comes as a gift from God rather than from the attraction between human beings. Its only perfect model is in the person of Jesus Christ, the God-man. We can see in the journey from eros in the “aesthetic authorship” to agape in the “second authorship” a personal attempt by Kierkegaard to sublimate his selfish desire for Regina into a self-sacrificing universal duty to love the neighbor. On his own terms this is impossible for a human being to achieve alone. It is only possible if love as agape is received as a gift by the grace of God.

f. The Attack on the Danish People’s Church

The “authorship” and “second authorship” had been governed by Kierkegaard’s elaborate method of “indirect communication.” This method, inspired by Socrates and Christ, is designed to elicit self-examination from the reader in order to start the process of existential transfiguration that is entailed by Christian faith. It is designed to make it harder for the reader to appropriate the text objectively and dispassionately. Instead, the text is folded back on itself, layered with riddles and paradoxes, and designed to be a mirror in which the way the reader judges the text amounts to a self-judgment on the reader. The different works in the “authorships” are related to one another dialectically, so that a reader has to traverse a complicated journey to arrive at the threshold of Christian faith. The method of indirect communication requires meticulous attention to each word, and to the dialectical trajectory of the whole oeuvre. At times, the subtlety of the method nearly drove Kierkegaard to distraction, and he had to rely on the intervention of “Governance” [Styrelse], to let him know whether it was appropriate to publish the works he had written. On the Point of View for My Work as an Author: A Report to History, and The Book on Adler, failed to get Governance’s stamp of approval for publication.

But ultimately Kierkegaard began to think that this elaborate method of indirect communication, and his obsession with linguistic detail were temptations to the demonic. Besides, time was running out and some direct, decisive intervention in Danish church politics was necessary. This was precipitated by the death of the Bishop Primate of the Danish People’s Church, J.P. Mynster (1854). Mynster had been the family pastor in Michael Kierkegaard’s day, and Søren Kierkegaard had always had a filial respect for him. But when the new Bishop Primate elect, H.L. Martensen, announced that Mynster had been “a witness to the truth” Kierkegaard could not restrain himself. He launched a stinging attack on the established church in a series of articles in the newspaper Fædrelandet [The Fatherland], and by means of a broadsheet called The Instant [or more literally “The Glint of an Eye”](1855) and in a series of other short, sharp pieces including This Must Be Said, So Let It Be Said (1855), and What Christ Judges of Official Christianity (1855). On September 28th 1855 Kierkegaard collapsed in the street. A few days later he was admitted to Frederiksberg Hospital in Copenhagen, where he died on November 11th.

2. The “Aesthetic Authorship”

a. On the Concept of Irony and Either/Or

Although Kierkegaard explicitly leaves On the Concept of Irony out of his “authorship,” it functions as an important preface to that body of work. According to the theory of existential stages contained in the authorship, irony functions as a “confinium” [border area] between the aesthetic and the ethical. But it also functions as a point of entry to the aesthetic. As Kierkegaard argues in On the Concept of Irony, irony is a midwife at the birth of individual subjectivity. It is a distancing device, which folds immediate experience back on itself to create a space of self-reflection. In Socrates it is incarnated as “infinite negativity” – a force that undermines all received opinion to leave Socrates’ interlocutors bewildered – and responsible for their own thoughts and values. That is, Socratic irony forces his interlocutors to reflect on themselves, to distance themselves critically from their immediate beliefs and values.

Although the aesthetic can consist in immediate immersion in sensuous experience, as in the case of Don Juan, Kierkegaard’s most developed portrait is of the reflective aesthete in Either/Or volume 1. Faust is the first example of a reflective aesthete. He is lost in reflective ennui and craves a return to immediate experience. This is the basis of his attraction to Margarete, who embodies innocent immediacy. At its most extreme, the aesthete is unhappily and utterly self-alienated by means of temporal dislocation. “The Unhappiest One” – an echo of Hegel’s “unhappy consciousness” – hopes for that which can only be remembered, and remembers that which can only be hoped. He or she lives only in the modality of possibility and never in the modality of actuality, and therefore fails to be self-present. Yet, by means of reflective self-knowledge, the prudent rotation of moods and the arbitrary focus of interest, this “unhappiness” can be transformed into the greatest happiness for the aesthete. The “infinitizing” element of possibility becomes the realm of freedom, where even the most banal events can be “poeticized” by aesthetic sensibility. Actuality is transformed into nothing more than an occasion for generating reflective possibilities, rather than being an obstacle or a task. Johannes the seducer need see only a dainty ankle descending from a carriage to reconstruct the whole woman – just as Cuvier reconstructs the whole dinosaur from a single bone. The reconstruction, in the case of Johannes however, is not for the sake of knowing what’s real, but is for the sake of his own aesthetic titillation. If the actual doesn’t fit Johannes’ reflective desires, he manipulates it and himself until he generates a story that satisfies him. His seduction of Cordelia is not aimed at mere sexual consummation, but more at narrative consummation – she is to be used as an occasion, and manipulated in whatever ways Johannes deems necessary, to become the character in the story of seduction he has predetermined. But this detachment from the actual, by self-centered immersion in reflective possibility, is exactly what On the Concept of Irony had accused the German Romantics of achieving with their use of irony. The first volume of Either/Or just gives us a more developed version, artistically construed from the point of view of German Romantic irony. On the Concept of Irony had already argued for the necessity to go beyond immersion in irony, or mere possibility – to become a “master of irony,” so that irony could be used strategically for ethical and religious ends. The title Either/Or presents us with a choice between the aesthetic and the ethical. The first volume is written from the point of view of the reflective aesthete, who has run astray in possibility. Although its main theme is love, this is conceived selfishly as erotic desire. The papers that comprise volume 1 are written ad se ipsum [to himself]. The aesthete’s brilliant pyrotechnics are demonically self-enclosed, ironically cutting him off from genuine communication. The second volume, on the other hand, is written by a judge, who advocates transparency and openness in communication. It is written in the form of letters, as a direct communication to the aesthetic author of the first volume. The letters implore him to realize the limitations of his demonic self-enclosure, and to embrace his ethical duties to others. Whereas the paradigm of love in volume 1 is seduction, the paradigm of love in volume 2 is marriage. Marriage is a trope for the universal claims of civic duty. It requires an open, intimate, transparent, honest relation to an other. Yet the first section of volume 2 argues for the aesthetic validity of marriage. Judge Wilhelm wants to persuade the aesthete that ethical love is compatible with aesthetic love – that love in marriage does not exclude sensual enjoyment and love of beauty as such, but only the selfishness of lust for “the flesh.” The latter is a category excluded by Christianity. It pertains to the body and psyche, to the exclusion of spirit, which is the definitive Christian category. Yet the claims of the judge ring hollow. Either/Or is presented as a whole book, edited by Victor Eremita (the victorious hermit). It presents us with a radical, exclusive choice between the aesthetic and the ethical, yet the judge tries to show their compatibility in marriage. The final word of the book belongs neither to the aesthete, the judge, nor even to the pseudonymous editor, but to an anonymous parson. His sermon, “The Edification Which Lies In The Fact That In Relation To God We Are Always In The Wrong,” alerts the reader to the impossibility of escaping sin through ethics. The assumption shared by both the aesthete and the ethicist is that love can provide a means for ascent to the divine. Whereas erotic desire provides a means for the aesthete to ascend to a state of reflective possibility unconstrained by actuality, in which he becomes his own creator-god, the judge conceives ethical love to be a dialectical advance on aesthetic selfishness – in the direction of God. The whole pseudonymous authorship, from Either/Or to Concluding Unscientific Postscriptcan be read as a parody of the notion of a scala paradisi by means of which humans can ascend to the divine. The original model for this ladder to paradise is Plato’s account of love [eros] in the Symposium. But the model is appropriated by many subsequent writers, including Augustine and Johannes Climacus, a sixth century monk from Mt. Sinai, who wrote a book called Scala Paradisi. Kierkegaard borrows this name for his pseudonymous author of Philosophical Fragments and Concluding Unscientific Postscript. But it is in order to parody the notion that humans can ascend to the divine under their own power. Each of the pseudonymous books in the “authorship” makes a gesture of movement from human to divine, whether by means of the aesthetic sublime, ethical virtue, the religious leap of faith, or philosophical dialectics. But in each case the apparent movement is “revoked” in some way. Ultimately Kierkegaard endorses the Lutheran view that human beings are radically dependent on God to descend to us. Human beings have no inherent capacity for transcending their own immanence, but are completely reliant on God’s grace to connect with alterity.

b. Fear and Trembling and Repetition

The next two books in the pseudonymous authorship, Fear and Trembling and Repetition, are supposed to represent a higher stage on the dialectical ladder – the religious. They are supposed to have moved beyond the aesthetic and the ethical. Fear and Trembling explicitly problematizes the ethical, while Repetition problematizes the notion of movement. Fear and Trembling reconstructs the story of Abraham and Isaac from the Old Testament. It tries to understand psychologically, ethically and religiously what Abraham was doing in obeying an apparent command from God to sacrifice his son. It apparently concludes that Abraham is “a knight of faith” who is religiously justified in his “teleological suspension of the ethical.” The ethic in question here is the civic virtue championed by Judge Wilhelm in Either/Or – corresponding to Hegel’s Sittlichkeit [customary morality]. The end for which this ethic is suspended is the unconditional command of God. But such obedience raises difficult epistemological questions – how do we distinguish the voice of God from, say, a delusional hallucination? The answer, which induces fear and trembling, is that we can only do so by faith. Abraham can say nothing to justify his actions – to do so would return him to the realm of human immanence and the sphere of ethics. The difference between Agamemnon, who sacrificed his daughter Iphigenia, and Abraham is that Agamemnon could justify his action in terms of customary morality. The sacrifice, however painful, was demanded for the sake of the success of the Greek military mission against Troy. Such sacrifices, for purposes greater than the individuals involved, were intelligible to the society of the time. Abraham’s sacrifice would have served no such purpose. It was unjustifiable in terms of prevailing morality, and was indistinguishable from murder. The ineffability of Abraham’s action is underscored by the pseudonym Kierkegaard chose as author of Fear and Trembling, namely, Johannes de silentio. But while Fear and Trembling is supposed to have moved beyond the aesthetic and the ethical, its subtitle is “a dialectical lyric.” Although its subject matter is ineffable and its author silent, it effuses aesthetically on its theme. It ends with an “Epilogue” that asserts that, as far as love and faith go, we cannot build on what the previous generation has achieved. We have to begin from the beginning. We can never “go further.”

Repetition begins with a discussion of the analysis of motion by the Eleatic philosophers. It goes on to distinguish two forms of movement with respect to knowledge of eternal truth: recollection and repetition. Recollection is understood on the model of Plato’s anamnesis – a recovery of a truth already present in the individual, which has been repressed or forgotten. This is a movement backwards, since it is retrieving knowledge from the past. It can never discover eternal truth with which it was previously unacquainted. In contrast, repetition is defined as “recollection forwards.” It is supposed to be the definitive movement of Christian faith. The pseudonym Constantin Constantius congratulates the Danish language on the word “Gjentagelse” [repetition], which more literally means “taking again.” The emphasis in the Danish, then, is on the action involved in the repetition of faith rather than on the intellection involved in recollection. Christian faith is not a matter of intellectual reflection, but of living a certain sort of life, namely, imitating [repeating] the life of Christ. Despite this verbal analysis of the difference between recollection and repetition, the characters in Repetition fail to achieve religious repetition. The pseudonymous author fails in his attempt to repeat a journey to Berlin, and the “young man” who has been “poeticized” by love seems to move in the direction of the religious, but ultimately gets no further than religious poetry. He becomes obsessed with Job, the biblical paradigm of repetition. He substitutes the book of Job for the beloved he has rejected, even taking it to bed with him. But in the end the “young man” turns out to be no more than a fiction invented by Constantius as a psychological experiment. He falls back into the realm of aesthetics, of mere possibility, a figment for the psyche rather than the spirit.

c. Philosophical Fragments, The Concept of Anxiety, and Prefaces

In June 1844 Kierkegaard published three pseudonymous books: Philosophical Fragments, The Concept of Anxiety, and Prefaces. Philosophical Fragments, the first book by the pseudonym Johannes Climacus, tackles the question of how there can be an historical point of departure for an eternal truth. This picks up from Constantius’ discussion of the difference between repetition and recollection. But Johannes uses the perspective and vocabulary of philosophy, rather than Constantius’ aesthetic irony. He introduces the paradox of the Christian incarnation as the stumbling block for any attempts by reason to ascend logically to the divine. The idea that the eternal, infinite, transcendent God could simultaneously be incarnated as a finite human being, in time, to die on the cross is an offense to reason. It is even too absurd an idea for humans to have invented, according to Climacus, so the idea itself must have a transcendent origin. In order for humans to encounter transcendent, eternal truth other than through recollection, the condition for reception of that truth must also have come from outside. If we have Christian faith, it is Christ as teacher who is the condition for receiving this truth – and he is conceived, precisely, as an incursion of the transcendent deity into the realm of human immanence. There can be no ascent to this truth by reason and logic, contra Hegel, who tries to demonstrate that “universal philosophical science” ultimately reveals “the Absolute.”

The emphasis Climacus places on the paradox of the Christian incarnation, together with his assertion that this causes offense to reason, have prompted many to the view that Kierkegaard is an “irrationalist” about Christian faith. Some take this to mean that his view of faith is contrary to reason, or transcendent of reason – in either case, exclusive of reason. Others have sought to find means of reconciling Climacus’ claims with some more extended notion of reason. It is important in considering these issues to distinguish Kierkegaard’s position from that of his pseudonym, and to take into account the point of view from which this consideration is made. Kierkegaard’s main aim in having Climacus make these claims is to undermine the idea that philosophical reason can be used as a scala paradisi. His principle target is Hegelianism, but he is also trying to distinguish pagan (especially Platonic) epistemology from Christian epistemology. We must also bear in mind that under the influence of Christian faith, all experience is transfigured (“everything is new in Christ”). This includes the experience of reason, as well as ethics and aesthetics. Ethics, for example, might be teleologically suspended in faith, but is recouped within Christian faith – though it comes to have another meaning. It is no longer merely customary morality, but is the morality sanctioned by Christian love, which is deontological, centered on spirit rather than sympathy, self-sacrificing, and is mediated by God (the “third” in every love relation). Similarly aesthetics is transfigured under Christian faith, from self-serving reflections confined to the realm of possibility, to the beauty inherent in altruistic self-effacing acts of love. Reason itself comes to have another meaning under Christian faith, so that it no longer takes offense at the paradox, but recognizes its necessity given the exigencies of relating the transcendent to the immanent without reduction. Reason is recontextualized within existence, rather than being elevated to absorb the whole of existence. Prefaces: Light Reading for Certain Classes as the Occasion May Require reinforces the polemic against Hegel’s speculative ladder of reason. Although much of its content is devoted to satirical broadsides at J.L. Heiberg, H.L. Martensen, and the popular press in Copenhagen, its starting point is the paradox of philosophical prefaces articulated in the preface to Hegel’s The Phenomenology of Spirit. Hegel’s assumption is that a philosophical work should be a sort of Bildungsroman – a narrative by means of which the reader’s consciousness is dialectically developed in the course of reading. If we assume the reader is to learn something from the process of reading the book, then he or she will not be in a position to understand the conclusions of the book until they have worked their way through the content. By the time they reach the end they will be conditioned by what they have read to understand the conclusion. But a preface presents the conclusions to the book at the outset. It is really an anticipatory postface rather than a preface. The reader will really only be able to understand it after having read the book. It is meant for orientation of the reader on embarking on the voyage of self-development represented by the book. But if it is a direct bridge into the book, the subject matter itself, then it is really part of the book rather than a preface. If, on the other hand, it stands radically outside the book, then it can’t be a bridge into the book and is redundant. This gap between preface and book parallels the gap Hegel draws between “particular philosophical sciences” (such as aesthetics, and history of philosophy) and “universal philosophical science” (logic). The former must be used as a contingent starting point, commensurate with the limited knowledge of the reader, as a point of induction into logic. The particular can retrospectively be subsumed within the universal, but cannot be expanded to become the universal. It has been claimed, in accordance with this position, that if the reader understands the preface to Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, he or she understands the whole of Hegel’s philosophy. But the condition for understanding the preface is already to understand the whole of Hegel’s philosophy. The pseudonymous author of Prefaces, Nicholas Notabene, is a pedant whose wife has forbidden him to be an author. He takes an author to be a writer of books, and with cunning sophistry decides to write nothing but prefaces “which are not the prefaces to any books.” Notabene’s prefaces are analogues of human immanence – no amount of expansion will make them bridges to the transcendent. All human immanence is a “preface” to the divine. Only once the divine has come to us (in the incarnation or through direct revelation) can we retrospectively understand the status of our prefatory lives as mere prefaces. For Kierkegaard there is only one book – the bible. We are never “authors” of books, but only readers of “the old familiar text handed down from the fathers.” On the same day as he published Prefaces Kierkegaard also published On the Concept of Anxiety by Vigilius Haufniensis [Watchman of the Harbor – namely, Copenhagen]. Its subtitle is “A Simple Psychologically Orienting Deliberation on the Dogmatic Issue of Hereditary Sin.” It is supposed to be a serious counterweight to the “light reading” of Prefaces. But it forms part of the same polemic against immanent human efforts to reach the divine. From the points of view of psychology and theological dogmatics it elaborates the theme of the sermon appended to Either/Or – that against God we are always in the wrong. Sin is inescapable. Sin ultimately consists in being outside of God. Only Jesus Christ, the God-man, is not in sin. Sin consciousness comes into being as part of human psychological development. It is absent from the innocent immediacy of childhood. It awakens with sexual desire – when we want to possess another. Desire is here understood as a lack that we want to fill. Possession, or incorporation of the other, is thought to be the way to fulfill the desire. In erotic love it feels as though part of ourselves is outside of us, and needs to be reintegrated (as in Aristophanes’ explanation of love in Plato’s Symposium). This is the beginning of self-alienation and the loss of innocent immediacy. Self-alienation is a necessary stage on the way to becoming a self. A self is a synthesis of finite and infinite, temporal and eternal, body and soul, held together by spirit. Only with the diremption of these aspects of the self, through self-alienation, does spirit arise. But spirit can only achieve the synthesis of self if it acknowledges its absolute dependence in this task on God (“the power that posits it”). Long before it gets to this stage, the person feels anxiety in the face of self-alienation. Anxiety is an ambivalent state, “a sympathetic antipathy and an antipathetic sympathy.” It is the intimation of the delights of freedom, but also of the dread responsibility that is a consequence of freedom. Like vertigo, it is the simultaneous fascination and fear of the abyss – a hypnotic possibility of falling that induces the dizziness to actually fall. The main arena for the exercise of freedom is in becoming a self. But this requires alienation from one’s immediate sensate being, taking ethical responsibility for one’s relations to other people, and acknowledgement of one’s ultimate dependence on God. Each of these entails risk – and hence anxiety. One of the risks involved is the possibility of falling prey to the demonic. A key definition of this notion is “self-enclosed reserve” [Indesluttethed] – a state in which the individual fails to relate to an other as other, but returns into him or herself in narcissism or solipsism. Kierkegaard feared that his convoluted, indirect writing could be his own form of the demonic, and ultimately opted for more direct forms of communication.

d. Stages on Life’s Way and Concluding Unscientific Postscript

Like many of Kierkegaard’s pseudonymous works, Stages on Life’s Way repeats elements from earlier pseudonymous works. In particular, it repeats the device of nesting narrators within narrators, it repeats characters from Either/Or and Repetition, and it “repeats” “The Seducer’s Diary” in “Quidam’s Diary.” The latter was originally conceived at the same time as “The Diary of the Seducer” but was to differ by having the seducer undermined by his own depression once he had won the girl. Stages also repeats the idea built up over the sequence of pseudonymous works that human existence can be conceived as falling into distinct “stages” or “spheres,” which are related in a dialectical progression. Stages repeats the same stages that have already been traversed in the preceding works, apparently without making any progress.

It is another example of the false ladder to paradise, exemplified by Plato’s ladder of eros. The first major section of Stages, “In Vino Veritas,” borrows its title from Plato’s Symposium and is modeled explicitly on that work, both structurally and thematically. It consists in a group of men at a banquet, each discoursing in turn on the nature of (erotic) love. This section of the book is followed by “Some Reflections on Marriage” by Judge Wilhelm, to give an ethical perspective on love. This is followed by “Quidam’s Diary,” which is supposed to follow a trajectory from erotic love to religious consciousness. But Quidam’s diary is framed by the words of Frater Taciturnus (a distorted repetition of Johannes de silentio), in which he tells us that Quidam’s diary was retrieved from the bottom of a lake. It was enclosed in a box with the key locked inside – a symbol of the demonic. Later Frater Taciturnus tells the reader explicitly that Quidam is demonic “in the direction of the religious.” Furthermore, like the “young man” from Repetition, Quidam is only a fiction invented by Frater Taciturnus to illustrate a point. As we read through Stages it looks as though we are progressing from the aesthetic, through the ethical to the religious. But Frater Taciturnus pulls the ladder out from under our feet in his “Letter to the Reader.” He even suggests that there might not be any reader, in which case he is content to talk to himself – i.e. return demonically into himself, rather than relate himself earnestly to an actual other. Concluding Unscientific Postscript repeats these movements of Stages. It proclaims itself to be only a postscript to the Philosophical Fragments, which any attentive reader of that book could have written, and contains an extensive review of the pseudonymous authorship to date. The self-proclaimed humorist, Johannes Climacus takes up the problematic of Philosophical Fragments of whether there can be an historical point of departure for eternal truth. He seems to conclude that since it is impossible to demonstrate the objective truth of Christianity’s claims, the most the individual can do is to concentrate on the how of appropriation of those claims. This issues in the extensive discussion of inwardness and subjectivity, which is usually taken as the basis for the accusation that Kierkegaard is an “irrationalist.” Climacus, but not Kierkegaard, proclaims that “truth is subjectivity” (as well as “subjectivity is untruth”). Climacus also makes a distinction between two types of religiousness: “Religiousness A” and “Religiousness B.” The former is the pagan conception of religion and is characterized by intelligibility, immanence, and recognition of continuity between temporality and eternity. Religiousness B is dubbed “paradoxical religiousness” and is supposed to represent the essence of Christianity. It posits a radical divide between immanence and transcendence, a discontinuity between temporality and eternity, yet also claims that the eternal came into existence in time. This is a paradox and can only be believed “by virtue of the absurd.” The distinction between “Religiousness A” and “Religiousness B” is another expression of the distinction between recollection and repetition, or between eros and agape, or between immanence and transcendence. It is supposed to mark the gulf between Christianity and all other forms of faith. The paradox of the Christian incarnation is presented as an offense to reason, which can only be overcome by a leap of faith. But even a leap is under the control of the individual. It might take more courage and induce more anxiety than the steady step-by-step ascension of a ladder. One is out over 70000 fathoms. But Climacus is a humorist. Humor is characterized as a means of “revoking” existence. Although Climacus writes about Christian faith, he doesn’t live it. He represents in the modality of possibility what can only be experienced in the modality of actuality. At the end of Concluding Unscientific Postscript, Climacus explicitly revokes everything he has said – though he is careful to add that to say something and revoke it is not the same as never having said it at all. That is, at the end of the pseudonymous scala paradisi, the pseudonymous author proclaims that what he has said is misleading – because it presents a continuity between immanent human categories of thought and the divine in the form of analogy. But there is no analogy to the divine. It is sui generis. It is “the book” to human life as “preface.”

3. The Edifying Discourses

a. Sermons, Deliberations, and Edifying Discourses

Simultaneously with the publication of the aesthetic pseudonymous works, Kierkegaard published a series of works he called “Edifying Discourses” [Opbyggelige Taler]. These were written under his own name and most of them were dedicated “To the Late Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard, Formerly a Clothing Merchant Here in the City, My Father.” Although they typically take a New Testament theme as their point of departure, Kierkegaard explicitly denies that they are sermons. This is because he had not been ordained, and so wrote “without authority.” They are also addressed to “that single individual” and not to a congregation.

Kierkegaard distinguishes his “edifying discourses” as a genre from other works he calls “deliberations” [Overveielser]. Edifying discourses “build up” whereas deliberations are a “weighing up.” Edifying discourses presuppose Christian faith and terminology as given and understood, and build on that. They are meant to augment the faith and love of the Christian reader. Deliberations, while they may ostensibly deal with the same subject matter, imply that the reader stands outside the matter being weighed. But this is in a particular sense. In weighing something on a scale, we measure two weights against one another. In deliberating, the reader weighs the temporal significance of the subject matter against its eternal significance. The deliberation, as a type of writing, weighs into the reader’s balance of temporal and eternal with polemical force. It is meant to turn the normal, worldly view topsy-turvy. Works of Love is subtitled “Some Christian Deliberations in the Form of Discourses.” It has the polemical, topsy-turvy nature of deliberation, but contains within it the form of the discourse. Furthermore, one of the explicit themes of these discourses is edification. But because of the framework of deliberation, the discourses about edification are not necessarily for edification. They don’t presuppose an understanding of the Christian categories, but are meant to lead the reader to an understanding – through deliberation. The earlier pseudonymous book, The Concept of Anxiety is subtitled “A Simple Psychologically Orienting Deliberation on the Dogmatic Issue of Hereditary Sin.” Like Works of Love it is a serious weighing up of various Christian concepts, in a manner designed to provoke readers to rethink the relation between the temporal and eternal in their lives. Kierkegaard uses yet other related genres besides deliberations and edifying discourses. The pseudonym Anti-Climacus uses the subtitles “A Christian Psychological Exposition [Udvikling] for Edification and Awakening” (The Sickness Unto Death) and “For Awakening and Making Inward” (Practice in Christianity). These are written from an idealized Christian point of view, so not only presuppose an understanding of the Christian categories, but seek to raise the level of awareness to the highest level of Christian faith.

b. Direct and Indirect Communication

Kierkegaard struggled to find appropriate means of communication that would address the inward nature of Christian faith. He thought his contemporaries had too much (objective) knowledge, which needed stripping away, before they could achieve awareness of individual inwardness. Everything was made too easy for people, with the press providing ready-made opinions, popular culture providing ready-made values, and speculative philosophy providing promissory notes in place of real achievements. Kierkegaard’s task as a communicator was, initially, to make things more difficult. In order to do this, he devised a method of indirect communication. This was designed to confront the reader with paradox, contradiction, and difficulty by means of refraction of the narrative point of view through pseudonyms, prefaces, postscripts, interludes, preliminary expectorations, repetitions, irony, revocation and other devices that obscure the author’s intention. These devices are meant to undermine the authority of the author, so any “truths” contained in the text cannot merely be learned by rote or appropriated “objectively.” Instead, the text is meant to supply a polished surface in which the reader comes to see him or herself. The manner in which the reader appropriates the text, understands it, and judges it will disclose more about the reader than about the text.

Part of the method of indirect communication was to juxtapose two series of texts: the pseudonymous texts and the “edifying discourses.” The latter were published under Kierkegaard’s own name, and were co-extensive with the pseudonymous authorship. They are evidence that he was a religious author from the outset. The indirect method of the pseudonymous works is often convoluted, obscure, and a combination of personal confession and obfuscation (of those confessions). The whole of the pseudonymous authorship from Either/Or to Concluding Unscientific Postscript can be read as a parody of Hegel’s Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences – an enormously baroque conceit that threatens to become demonic in its obscurity and labyrinthine complexity. This complexity is balanced by the relatively simple thematic variations on biblical texts to be found in the edifying discourses. The latter were direct communications – but addressed only to Christians who could understand them. The indirect works, on the other hand, were designed to seduce or deceive into the truth those who stand outside it – such as the Danish Hegelians and their followers. By parodying Hegel’s Encyclopedia, Kierkegaard was undermining the whole system on which the Danish Hegelians placed so much faith. He supplemented his parody of Hegel with more specific jibes at particular Danish Hegelians throughout the “authorship.” Kierkegaard continued to write edifying discourses in conjunction with the “second authorship,” to accompany the works of the pseudonym Anti-Climacus. After the “second authorship” he wrote Christian discourses that were more polemical and strident than the edifying discourses. They were equally “direct” – being published under his own name, but addressed different emotions and values.

c. That Single Individual, My Reader

Kierkegaard’s edifying discourses are addressed to “that single individual, my reader.” When he first used this address he meant it to apply to Regina Olsen. But he came to see that it had a wider application. He had polemicized from his earliest writings against the press, and against cultural and political tendencies to “level” individuals into homogeneous masses. His term of loathing for the depersonalized, de-individualized instrument of leveling was “the crowd.” It corresponds to Nietzsche’s notion of “the herd” and to Heidegger’s notion of “das Man.” One subset of “the crowd” that especially attracted Kierkegaard’s ire was “the reading public.” This was the anonymous mass, consumer of the secondhand literary opinion of “reviewers.” Most reviewers, in Kierkegaard’s opinion, were hasty, ill-informed panderers to public opinion, so that reviewers and public fed off each other in a vicious circle. Reviews were even written without the reviewer having read the book, then circulated through gossip by “the reading public” as final judgment on the book. The anonymous circulation of public gossip is the antithesis of serious engagement with truth on a personal level.

Christianity addresses the single individual. Its truths, according to Kierkegaard, must be appropriated inwardly, seriously and with infinite passion. Just as we cannot die another’s death, we cannot live another’s faith. Existing inwardly in passion as an individual is a prerequisite for Christian faith. Having Christian faith is a prerequisite for understanding the edifying discourses. So the edifying discourses are addressed to each single individual. The pseudonymous works in the aesthetic authorship often have letters addressed to the reader too. But, as in the case of the letters of Constantine Constantius and Frater Taciturnus, they turn out to be soliloquies addressed to themselves more than direct, open communications to a reader posited as genuinely other.

4. The “Second Authorship”

a. Works of Love

Works of Love was written under Kierkegaard’s own name. Its subtitle places it within the genre of “Christian deliberations” – i.e. polemical weighings-up of Christian notions. It does not presuppose an existential understanding of Christian love, as it would were it an “edifying discourse,” but challenges the reader to open him or herself to the specifically Christian understanding of love. For a reader who understands love principally in terms of eros, the Christian notion of love as agape is counterintuitive. Whereas eros is a preferential feeling of desire, agape is a spiritual duty to serve the neighbor (without discrimination in terms of preference). Whereas eros is ultimately selfish, aimed at satisfying the lover’s desire, agape is selfless, requiring self-sacrifice. Whereas eros is often built on the visual objectification of the beloved, agape requires the individual to become “transparent” and “as nothing” before God. Whereas eros is typically a relation between two people, agape always involves God as the “third” in the relation.

Works of Love concentrates not so much on the understanding of love as such, but on the understanding of works of love. Love will be known as the fruit of these works of love. Since God is love, it can only be known through the existential commitment of Christian faith. This faith is only lived in the attempt to imitate the life of Christ. Christ’s life was itself God’s principal work of love for human beings. It is only through this work of love that we can know God as love. The only true work of love is helping someone else achieve autonomy through Christian love. But if that person sees that he or she was dependent on some other human being to achieve autonomy, that autonomy will be undone. The human author of a work of love must disappear in the act of love, so that only the love is perceived and only God is recognized as its author. This presents Kierkegaard with a difficult task in writing Works of Love. If it helps its readers achieve autonomy through an understanding of Christian love, and the readers recognize Kierkegaard to be the author, it will fail to be a work of love. Kierkegaard has to disappear as author in order for the book to function as a work of love. He resorts to the device of the dash [Tankestreg] to achieve his disappearance. He explicitly talks about this use of the dash during the course of Works of Love, and ends the penultimate section of the book with a dash (unfortunately omitted from the English translation). The conclusion that follows the dash is a presentation of the words of the Apostle John. As an Apostle, John presents the word of God. The word of God is a record of the life of Christ, which is God’s work of love. So God’s word is the work of love. Kierkegaard, by means of the dash, erases his ego as an author to allow the word of God to shine through – thereby preserving Works of Love as a work of love.

b. Anti-Climacus

Anti-Climacus is the pseudonymous author of two of Kierkegaard’s mature works: The Sickness Unto Death (1849) and Practice in Christianity (1850). As his name indicates, Anti-Climacus represents the antithesis of Johannes Climacus. As we have seen, Climacus derives his name from the monk who wrote Scala Paradisi, thereby embracing the idea that it is possible for human beings to ascend to heaven under their own power. The “aesthetic” authorship, culminating in Concluding Unscientific Postscript, explores a number of possible modes of scaling heaven – by means of erotic love, the Babel tower of aesthetic poetry, ethical works, or speculative reason. All are found wanting. Having established the absolute nature of transcendence through repeated parodies of these vain attempts in the aesthetic authorship, Kierkegaard proceeds to show through Anti-Climacus how various aesthetic concepts are transfigured from an ideal Christian point of view.

The central notions explored in The Sickness Unto Death are “despair” and “the self.” In this respect it is a Christian repetition of the central themes of The Concept of Anxiety, with “despair” supplanting “anxiety.” Both explore the task of becoming a self from the points of view of psychology and Christian faith. Both invoke sin as the greatest obstacle to becoming a self. Yet paradoxically, becoming conscious of sin is a prerequisite for faith and selfhood. Anti-Climacus distinguishes between “human being” and “self.” The human being is a synthesis, of infinite and finite, temporal and eternal, freedom and necessity, body and soul. The self, on the other hand, is the process of relating these elements of synthesis to one another. The self is the task of maintaining the proper equilibrium of the synthesis. But this task is beyond the capacity of a mere human being alone. Willing to be a self is itself a form of despair. Not willing to be a self is also a form of despair. Being unaware of the possibility of being a self is also a form of despair. The only antidote to despair is Christian faith. Faith provides the missing element in the synthesis, namely, an acknowledgement of God as the necessary underpinning of the self-relation. But to become aware of God, one first has to become aware of one’s absolute difference from God. This is the function of sin-consciousness. Sin-consciousness presupposes God-consciousness. The ultimate form of despair is despairing over one’s sin, and thereby failing to accept God’s forgiveness. Only through the movement of faith can God’s grace be received and accepted, thereby acknowledging God’s absolute alterity as well as our absolute dependence on God to be selves. Practice in Christianity complements The Sickness Unto Death thematically. It deals with the appropriate Christian response to divine grace, and with healing through penitence. But it also repeats some of the themes of Philosophical Fragments and Concluding Unscientific Postscript. In particular it revisits the themes of offense and the historical point of departure for eternal truth. The latter is explored under the rubric of becoming contemporary with the absolute. Christian faith is the only means for the immanent, temporal human being to have contact with the transcendent, eternal truth, since that faith consists in believing that Christ was the incarnation of God. That faith consists not merely in intellectual belief, but in willingness to imitate the life of Christ to the utmost of one’s powers. Anti-Climacus catalogues various ways in which we might take offense at someone claiming to be the “God-man.” In the process he discusses the necessity for God, as transcendent, to use a method of indirect communication. The God-man needs to be “incognito” – to arrive in the unrecognizable form of a servant. He needs to suffer, to be spurned, to avoid any possible direct revelation of His exalted status. Only by means of indirect communication, rather than by direct revelation, will the individual come to relate to the God-man through faith. The possibility of faith is the obverse of the possibility of offense. Offense is underscored by means of the Almighty’s lowly incognito and indirect method of communication.

c. The Attack on the Church

Kierkegaard came to think that perhaps indirect communication should be the exclusive provenance of the God-man. He came increasingly to regard his own indirection, and his love affair with language, to be demonic temptations. When the Bishop Primate of the Danish People’s Church, his father’s old pastor J.P. Mynster, died in January 1854, Kierkegaard felt free to attack the established church more directly and stridently. He had suppressed some critical and potentially offensive writings while Mynster was still alive. But he was precipitated into a full frontal attack when the new Bishop Primate, H.L. Martensen, Kierkegaard’s old rival, publicly described the late Mynster as “a witness to the truth.” Kierkegaard had respected Mynster as a pastor and a man, but found his administration of the church wanting. Mynster had steered the church into closer relations with the state, and had shored up the values of “Christendom” rather than “Christianity.” The former was a phenomenon of cultural history; the latter was the vehicle of passionate, inward individual faith. Given the leveling tendencies of “the present age,” Christendom as a cultural phenomenon was on a collision course with Christian faith. It threatened to replace “the single individual” with “the crowd” (under the guise of “the congregation”), struggle with mediation, revolution with reflection, and works of love with the welfare state. Worst, it threatened to usurp eternal truth with temporal gossip. Therefore, to call its chief spokesman a “witness to the truth” provoked an extreme reaction from Kierkegaard.

His discourses changed from gentle edifications to strident calls to arms. He moved from a position of “armed neutrality” with respect to church politics, to one of decisive intervention in “the instant.” “The Instant” [Øieblikket – literally ‘the glint of an eye’] was Kierkegaard’s final frenetic publication. The Concept of Anxiety had identified “the instant” as the point of intersection of time and eternity. It is the moment of decision, the moment of transfiguring vision, the moment of contemporaneity with Christ. It was also the moment to let go of indirect communication and to speak directly. “The Instant” was the name of a broadsheet Kierkegaard published to continue his attack on the state church. He published ten issues between its inception in May 1855 and the last in September 1855, when he collapsed and was admitted to hospital. But to speak directly, having spoken for so long indirectly, is not the same as the “objective” direct communication he originally resisted. It was not a direct communication about eternal truth, but a timely intervention in contemporary politics. It was a verbal act, rather than a measured contribution to literature. Another important part of the “second authorship” consists in the self-reflections Kierkegaard wrote on his own work as an author. In 1851 he published On My Work as an Author, but had also written several other works that were only published posthumously. These include The Point of View for my Work as an Author: A Report to History (1859), Armed Neutrality, or My Position as a Christian Author in Christendom (1880), and “Three Notes Concerning my Activity as an Author” (1859). He also withheld from publication The Book on Adler, an extended study of Adolph Adler, a prominent Hegelian and pastor in the Danish People’s Church. Adler claimed to have received divine revelation, but Kierkegaard’s analysis of his writings tries to demonstrate Adler’s confusion. Adler becomes, in Kierkegaard’s words, “a Satire on Hegelian Philosophy and the Present Age.” Kierkegaard also used Adler’s case to distinguish between “a genius” and “an apostle.” Another work, also published posthumously, was “The Ethical and Ethico-religious Dialectic of Communication” (1877). Kierkegaard agonized over whether to publish these direct communications about his own strategies of communication and how he saw his activity as an author. Of particular concern was how these direct writings would affect the complex dialectic of direct and indirect communications he had set up in his “authorships.” Ultimately he relied on the guidance of “Governance” [Styrelse] to decide whether or not to publish – much as Socrates had relied on the warnings of his daimonion about whether to engage people in philosophical cross-examination. Retrospectively, Kierkegaard regarded his activity as an author to have been under the direction of Governance. He had not had a clear view at the outset about the structure of his authorships, but had come to see that what he had been directed to write was what was required for a religious poet in the present age. He was a writer who overflowed with ideas – far too many to write down. Therefore Governance had to sit him down like a schoolboy, and make him write as though he were writing “a work assignment.” In much the same way as he disappeared under the dash in works of love, Kierkegaard “disappears” in these accounts of his own activity as a writer under the sign of “Governance.”

5. References and Further Reading

Kierkegaard’s Writings

Danish

Breve og Aktstykker vedrørende Søren Kierkegaaard, ed. Niels Thulstrup, Copenhagen: Munksgaard, 1953-4.

Søren Kierkegaards Papirer, ed. P.A. Heiberg, V. Kuhr & E. Torsting, second edition Niels Thulstrup, Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 1968-78.

Søren Kierkegaards Samlede Værker, ed. A.B. Drachmann, J.L. Heiberg & H.D. Lange, second edition, Copenhagen: Nordisk Forlag, 1920-36.

Søren Kierkegaards Skrifter, ed. N.J. Cappelørn, et.al., Copenhagen: Gad, 1997-.

English Kierkegaard’s Writings volumes 1-XXVI, ed. & trans. H.V. Hong, et.al. Princeton University Press: 1978-2000.

Commentary

Cappelørn, Niels Jørgen, Hermann Deuser, et.al. (eds), Kierkegaard Studies Yearbook 1996-, Berlin & New York: Walter de Gruyter, 1996-

Ferreira, M. Jamie, Love’s Grateful Striving: A Commentary on Kierkegaard’s Works of Love, Oxford University Press, 2001

Garff, Joakim, SAK: Søren Aabye Kierkegaard: en biografi, Copenhagen: Gad, 2000

Hannay, Alastair, Kierkegaard: A Biography, Cambridge University Press, 2001

Hannay, Alastair & Gordon Marino (eds), The Cambridge Companion to Kierkegaard, Cambridge University Press, 1998

Kirmmse, Bruce, Encounters With Kierkegaard, Princeton University Press, 1996

Kirmmse, Bruce, Kierkegaard in Golden Age Denmark, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990

Mackey, Louis, Points of View: Readings of Kierkegaard, Tallahassee: Florida State University Press, 1986

Malantschuk, Gregor, Kierkegaard’s Thought, ed. & trans. H.V. Hong & E.H. Hong, Princeton University Press, 1971

Pattison, George, Kierkegaard: The Aesthetic and the Religious, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992

Perkins, Robert L (ed.), International Kierkegaard Commentary, Macon: Mercer University Press

This is a series of anthologies of essays, with each volume designed to accompany the volumes comprising Kierkegaard’s Writings, op.cit.

Author Information

William McDonald

Email: [email protected]

University of New England

Australia