Setvayajan: An Abandoned Conlang

Author: Barry J. Garcia

MS Date: 03-03-2020

FL Date: 06-01-2020

FL Number: FL-000069-00

Citation: Garcia, Barry J. 2020. «Setvayajan: An

Abandoned Conlang.» FL-000069-00, Fiat

Lingua,

2020.

Copyright: © 2020 Barry J. Garcia. This work is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

Fiat Lingua is produced and maintained by the Language Creation Society (LCS). For more information

about the LCS, visit http://www.conlang.org/

SETVAYAJAN

An Abandoned Conlang

Barry J. Garcia

March 2020

2

Contents

1 Why I Abandoned Setvayajan

2 Phonetics

.

2.1 Phonology . . . . . . . . .

.

2.1.1 Orthography . . .

2.1.2 Consonants . . . .

.

2.1.3 Vowels . . . . . . . .

.

.

2.2 Syllable Stress . . . . . . .

2.2.1 Word Stress . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

3 Nouns

3.1 Nouns

. . . . . . . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

3.1.1 Direct and Indirect Object Marking .

.

.

3.1.2 Determiners . . . .

.

3.1.3 Possession . . . . .

.

.

3.1.4 Plurals . . . . . . . .

.

.

3.1.5 Noun Derivation .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

4 Pronouns

4.1 Personal Pronouns

4.2 Demonstrative Pronouns .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. . . .

.

.

.

4.1.1 Non-Gendered Pronouns .

.

.

.

4.2.1 Demonstrative Adjectives .

.

.

.

.

Indefinite Pronouns . . . .

4.3.1 Existentials as Indefinite Pronoun Replacements .

.

Interrogative Pronouns . .

.

.

.

4.4.1

.

.

Interrogative Adjectives .

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

. .

. .

.

.

. .

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

4.5 Subject Dropping . . . . .

4.3

4.4

5 Modifiers

5.1 Modifier Placement . . . .

.

5.2 Modifier Formation and Derivation .

.

5.2.1 Other Derivational Affixes .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

3

7

9

. 10

. 10

. 12

. 13

. 14

. 14

15

. 15

. 15

. 16

. 18

. 18

. 20

23

. 23

. 25

. 26

. 27

. 28

. 28

. 29

. 30

. 30

33

. 33

. 34

. 34

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

4

6 Verbs

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

6.2 Tense and Aspect

. .

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

. .

. .

.

.

.

.

. .

. .

. .

6.3 Applicatives . . . . . . . .

6.4 Causatives . . . . . . . . .

6.4.1 Direct Causative .

6.4.2

.

6.1 The Infinitive . . . . . . . .

.

6.1.1 Gerund . . . . . . .

.

Imperative . . . . .

6.1.2

.

. . . . .

6.2.1 Tenses . . . . . . .

.

6.2.2 Aspects . . . . . . . .

.

.

.

Indirect Causative .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

6.5 Grammatical Mood . . . .

.

6.6 Participles . . . . . . . . .

.

6.7 Ditransitive Verbs . . . . .

6.8 Passive Voice And Intransitive Verb Conversion .

.

.

.

.

.

.

6.8.1 Passive Voice . . .

6.9 Reflexive Constructions

.

6.10 Verb Intensification . . . .

6.11 Verb Derivation . . . . . .

6.11.1 Affixation XXX . .

6.11.2 Compounding . . .

.

.

. .

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

7 Prepositions

8 Conjunctions

8.1 Conjunctions . . . . . . . .

.

8.1.1 Coordinating Conjunctions .

Subordinating Conjunctions .

8.1.2

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

9 Negation XXX

10 Subordinate Clauses

.

.

.

.

.

10.1 Relative Clauses . . . . . .

.

.

10.1.1 Direct And Indirect Objects In Relative Clauses

.

10.1.2 Adjectives As Subordinate Clauses .

.

.

.

.

.

10.2 Noun Clauses . . . . . . .

10.3 Adjective Clauses . . . . .

.

10.4 Sentences with Multiple Subordinate Clauses .

.

. .

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

11 Topicalization

12 Existentials

.

12.1 Ko – Existential . . . . . . .

12.2 ¯Az – Non-Existential

.

. . .

12.3 Existentials For ”It is” Constructions .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

CONTENTS

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

37

. 37

. 38

. 38

. 39

. 39

. 40

. 41

. 41

. 42

. 42

. 42

. 44

. 44

. 45

. 45

. 46

. 46

. 46

. 46

. 47

49

51

. 51

. 51

. 51

53

55

. 55

. 55

. 56

. 56

. 56

. 56

57

59

. 59

. 59

. 60

CONTENTS

13 Numbers

13.0.1 Cardinal Numbers .

.

13.0.2 Ordinal Numbers .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

14 Language and Culture

14.1 Sentence Final Discourse Particles .

.

14.2 Interjections . . . . . . . .

.

14.2.1 Main Interjections

.

14.3 Addressing People . . . .

.

14.4 Greetings and Farewells .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

14.4.1 Standard Greetings .

.

14.4.2 Informal Greetings .

.

.

14.4.3 Formal Greetings .

.

.

14.4.4 Farewells . . . . . .

.

.

. . . . . . .

.

.

14.5.1 Family Name . . .

14.5.2 Given Name . . . .

.

.

14.5.3 Hazum – House Name .

.

14.5.4 Name Format . . .

.

14.6 Apologizing . . . . . . . .

14.5 Setvai Names

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

15 Setvayajan Sound Changes

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

. .

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

15.0.1 First period (1,500 – 1,000 years ago)

.

15.0.2 Second period (1,000 – 650 years ago)

.

.

15.0.3 Third period, modern Setvayajan (650 – 345 years ago) .

15.0.4 Vowel and diphthong changes that happened consistently over all

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

15.1 Modern Sound Change Processes .

.

15.1.1 Phonotactics . . . .

. . . . . .

periods:

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

5

61

. 61

. 62

63

. 63

. 63

. 63

. 65

. 66

. 66

. 66

. 67

. 68

. 68

. 68

. 69

. 70

. 72

. 72

73

. 73

. 73

. 75

. 76

. 77

. 77

6

CONTENTS

Chapter 1

Why I Abandoned Setvayajan

The following document is Setvayajan as it stands at the point I decided to abandon the

project to work on a better, more systematic, and more cleanly designed version. I had

started the project in 2014, though put it down in a formal manner in 2015. At the time I

hadn’t really considered Setvayajan being entirely naturalistic, more of a Philippine and

Hindustani sounding artlang. David J. Peterson’s advocating for the naturalistic style of

conlanging struck a chord with me, and I decided halfway through to try to get Setvayajan

to that state while keeping what I’d already done.

Bad move. Because I hadn’t started off with a solid proto language first, I was working with

what was already there, and trying to retcon what was there into a naturalistic conlang.

There was also a strong drive to get words in modern Setvayajan that ”sounded right”,

and so I’d started off with the modern version in mind and worked backwards to a ”proto”

form to get what I wanted. This is fine for easter eggs, but for a lot of the words, it just

resulted in a total mess. What also really didn’t help was the list of sound changes were

largely ad-hoc (and some pushing into ”Hmm… I’m not so sure” territory), added on the

fly and poorly explained, so months later I’d look at them and then forget why a particular

rule was written as it was or get confused because I hadn’t been careful.

Grammarwise, all of it, and I do mean all of it was based on the modern form of Setvayajan,

not working from a proto language (because well, like I said, there was none). I actually

like much of the grammar (and I really don’t hate it), but it lacks the interplay that sound

changes and the proto language’s grammar can create to produce the modern language.

To sum it all up, a lack of good planning and the lack of a proto grammar ended up with

me in a constant cycle for years trying to clean up a total mess that could have been avoided

if I’d planned out the proto form first and then worked from there.

Read on to see the lurching, hulking, shambling mess that Setvayajan turned out to be.

7

8

CHAPTER 1. WHY I ABANDONED SETVAYAJAN

Chapter 2

Phonetics

9

10

2.1 Phonology

CHAPTER 2. PHONETICS

Setvayajan’s sound inventory consists of twenty three consonants, and seven vowels. All

consonants and five vowels are represented in the Latin orthography and native writ-

ing system. Two vowels are not represented by their own characters, being allophones.

The basic syllable structure is vowel, consonant-vowel, vowel-consonant, and consonant-

vowel-consonant.

2.1.1 Orthography

Orthography is the way a language is written. Here, what is meant by orthography is

the method in which Setvayajan is written in Latin letters. Setvayajan does have its own

writing system called Ranj¯al, which will be explained in its own chapter, but this section

explains how to write Setvayajan in our writing system.

The Latin orthography for Setvayajan is largely based on English spelling conventions for

the consonants, and M¯aori’s system of using macrons for writing long vowels. The use of

macrons (the long bar above the vowel) is simply an aesthetic and space saving method.

While the standard orthography calls for writing long vowels with a macron over the

vowel, the long vowels can also be written as doubled letters, but this is only used when

writing letters with macrons would not be possible (as in web addresses, for instance). I

find this to be unattractive, and it also leads English speakers to perceive certain doubled

vowels as entirely different sounds than intended. For example, English speakers see ee

as /i/, and oo as /u/).

Below is the Latin orthography for Setvayajan. An explanation of the various sounds rep-

resented by these letters and digraphs is given in the sections on the consonants and vow-

els:

(cid:15) Consonants: b, d, f, g, h, ch, j, k, kh, l, m, n, ng, p, r, s, sh, t, th, v, y, z, zh

(cid:15) Vowels: a, ¯a, e, ¯e, i, ¯ı, o, ¯o, u, ¯u

The six digraphs ch, kh, ng, sh, th, and zh are explained below. Two digraphs, ch and sh,

are pronounced as they typically are in English, but the others may not be as obvious to

an English speaker:

(cid:15) ch – /(cid:217)/: This represents the same sound as in chime, but never to represent /S/ (as

in chef ). This is the only time the letter c is used in this orthography.

(cid:15) kh – /x/: This is the same sound as ch in the Scottish word loch , or the German word

nacht.

(cid:15) ng – /N/. This is the consonant sound at the end of sing. It is never followed by a

/g/ as in singer.

(cid:15) sh – /S/. Pronounced the same as in shine.

2.1. PHONOLOGY

11

(cid:15) th – /T/. Pronounced as the th in thing but never as in this

(cid:15) zh – /Z/. This is the sound represented by z in azure.

Few orthographies are perfect, and this system can be a bit troublesome, particularly with

regard to kh, sh, th and zh. Normally, a following h is pronounced separately, but here,

they represent four particular sounds; /x/, /S/, /T/, and /Z/. In order to represent two

separate consonants, an apostrophe is inserted:

(cid:15) k’h – /kh/

(cid:15) s’h – /sh/

(cid:15) t’h – /th/

(cid:15) z’h – /zh/

These four examples are the only instances in the Latin orthography when the apostrophe

is used in this manner. The apostrophe is never used for ”effect” as is so often seen in

western works of fantasy or sci-fi where it is a meaningless, and often excessively overused

decorative mark intended to make a word look ”exotic” or ”alien”. In Ranj¯al, this is not a

problem as it has very clear ways of distinguishing between these consonant sounds and

consonant clusters.

Diacritic Marking

In addition to the macron, Setvayajan’s orthography and uses an acute accent mark. The

acute accent mark is used to denote words where the syllable stress falls on a syllable

where it would not normally be expected. In Setvayajan, it generally appears in borrowed

words where the original stress is preserved, or in affixed words which do not result in

new, derived words.

12

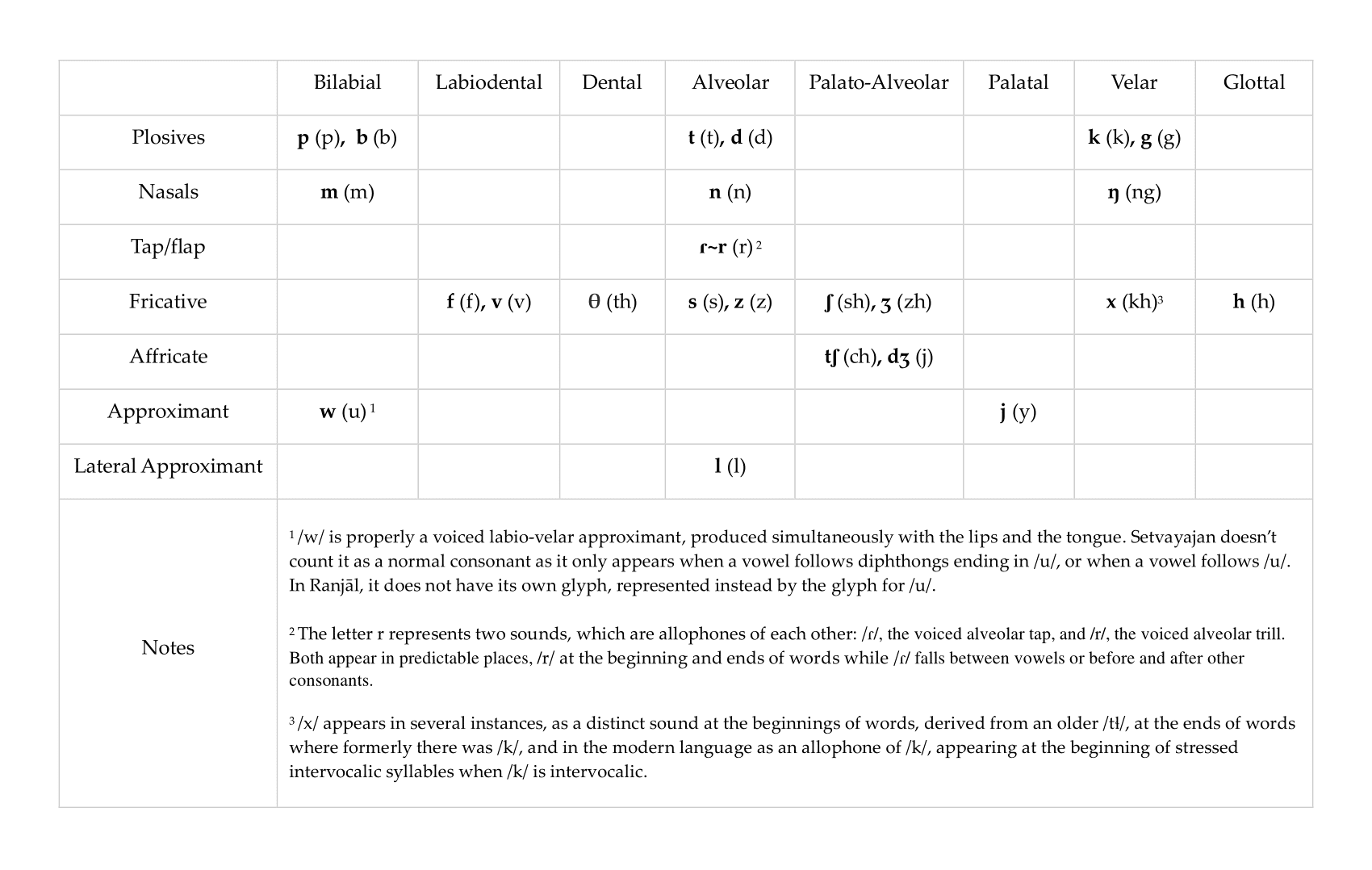

2.1.2 Consonants

CHAPTER 2. PHONETICS

Below is the consonant chart for Setvayajan. The twenty two phonemic consonants are

laid out in the chart based upon point of articulation (where the sound is produced in the

mouth) along the top row, with the manner of articulation (how the sound is produced in

the mouth) along the left most column.

Figure 2.1: Setvayajan Consonant Inventory

Where a two different sounds are separated by a comma, the left sound is unvoiced while

the right one is voiced. Letters that are bolded are the phonetic characters, while letters in

parentheses are the written representation of the sounds the phonetic letters represent.

Consonant Allophones

Setvayajan has few consonant allophones, and they are not indicated in writing. Their

appearance is regular and predictable:

(cid:15) /p/, /t/, and /k/ can become aspirated if they are part of a stressed, closed syllable.

(cid:15) In many dialects of Setvayajan, /k/ tends to become /x/ at the beginning of a stressed

syllable if it is intervocalic. This is not universal for all speakers.

(cid:15) /r/ is an allophone of /R/ and appears at the beginnings and ends of words.

2.1. PHONOLOGY

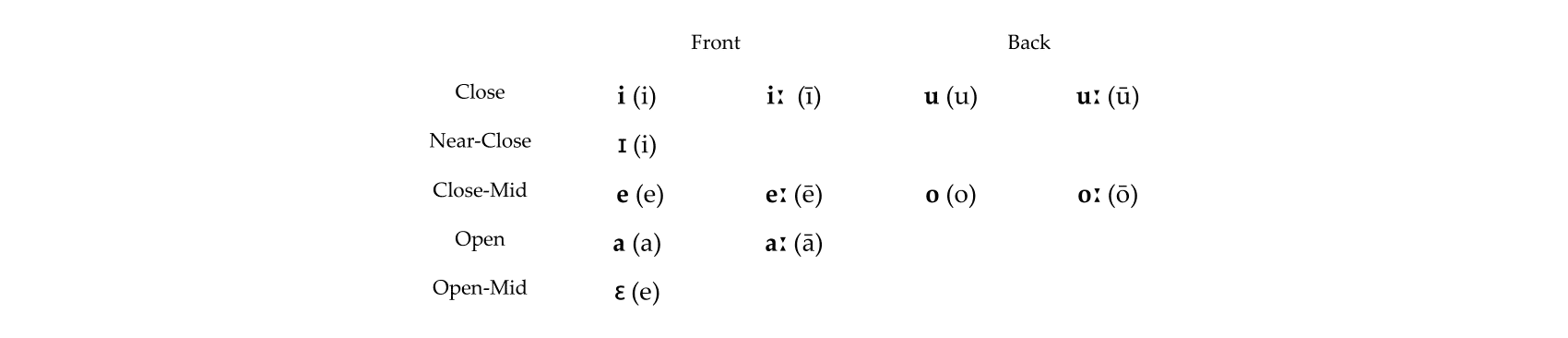

2.1.3 Vowels

13

The vowels are illustrated in the chart below. There are five vowels, and these are split

between short variants and long variants.

Figure 2.2: Setvayajan Vowel Inventory

For an English speaker, vowel length may seem like an exotic thing, but vowel length

does appear in English. Long vowels are allophones of short vowels in English, and most

English speakers don’t notice them. In Setvayajan on the other hand, vowel length is dis-

tinctive and differentiates the meaning between two otherwise identical words:

(cid:15) an – uncertainty particle

(cid:15) ¯an – hard, durable, tough

For an average English speaker unfamiliar with languages that distinguish between long

and short vowels to differentiate between otherwise similar words, the two words would

sound the same. Some listeners might notice the length difference, but would typically

not understand that the vowel length makes a difference in determining the meaning of

the word.

Vowel Allophones

There are only a handful of vowel allophones, which are not distinguished in writing in

Setvayajan. Not all dialects share the same allophonic rules for the vowels, and Setvayajan

spoken by speakers of dialects without these allophonic rules may sound odd to a non-

native speaker who is used to the standard dialect:

(cid:15) /e/ and /i/ are allophones of /E/ and /I/ which always appear in closed syllables

in the standard. Some dialects lack /E/ and /I/ entirely.

(cid:15) /a/ and /e/ often reduce to /@/ in unstressed syllables.

(cid:15) Stressed short /a/, /e/, and /i/ tend to be pronounced as /æ/, /E/, and /I/.

14

CHAPTER 2. PHONETICS

2.2 Syllable Stress

Setvayajan marks stress in a word based on syllable weight. This means that the heaviest

syllable will always take the stress in a word. The weight of a syllable is one of three types:

heavy, medium, and light. This weight is determined based upon the following factors:

(cid:15) Heavy syllables always end in unvoiced stops, geminate consonants, or they contain

long vowels.

(cid:15) Medium syllables end in consonants other than the unvoiced stops, or in a diph-

thong.

(cid:15) Light syllables are always open and always end in short vowels.

2.2.1 Word Stress

Stress marking is predictable in Setvayajan. For a Setvayajan speaker, assigning stress is

largely natural, and this pattern tends to be followed with non native languages for Set-

vayajan speakers. But for a learner of Setvayajan, the process may not be as transparent.

To keep it simple for the sake of explanation, the following pertains to words of no more

than three syllables:

(cid:15) If all syllables are of equal weight, the second to last (penultimate) syllable will take

the stress

(cid:15) If a word contains light syllables and at least one medium or heavy syllable, the

heaviest syllable will take the stress.

(cid:15) If a word contains at least two heavy syllables, or two medium syllables, the first

heavy or medium syllable will take the stress.

(cid:15) If there is at least one long vowel in the word, it will take the stress regardless of

whether another heavy syllable comes before it.

With longer words, the stress marking is more complex, but primary stress always falls on

the heaviest syllable in a word, or the penultimate syllable if all syllables are of the same

weight. Secondary stress is distributed to every other syllable out from the syllable with

primary stress.

Chapter 3

Nouns

3.1 Nouns

In Setvayajan, nouns may be derived from roots, from affixed roots, or compounded words.

Basic nouns tend to be roots while compounding and affixing are highly productive meth-

ods of deriving new words. Setvayajan tends to coin new words rather than borrow them.

Unlike English, nouns are marked for case, but rather than as an affix as in Latin, two case

marking particles are used.

3.1.1 Direct and Indirect Object Marking

Setvayajan marks direct and indirect objects using two marking particles. These particles

are placed before the nouns they mark. In addition to marking nouns for the direct and

indirect objects in a sentence, they can also act as a sort of generalized preposition. When

used in this way, context needs to be clear to ensure that the meaning of the sentence is

understood:

(cid:15) Kahinno kau tsaya ni tsuo. – I hit him on the head

In the above example, the marking particle ni is standing in for the preposition ran, which

in this case means on. Use of these particles to stand in for prepositions happens far more

with indirect objects because the choice of verb will often imply what preposition would

normally be used with the indirect object. If a preposition is used with the noun, the

particle is omitted:

(cid:15) Kahinno kau tsaya ran tsuo. – I hit him on the head

In this example, ran (meaning on) takes the place of the indirect marking particle ni. In

very colloquial varieties of Setvayajan, the word marking particles get dropped, and word

order becomes strictly fixed. When the direct and indirect object marking particles are

omitted, the word order becomes a strict verb-subject-object-indirect object word order. How-

ever, pronouns will still be used in their direct and indirect object forms.

(cid:15) Kahinno saro to isan vo sho. – The man hit the house with a rock.

15

16

CHAPTER 3. NOUNS

(cid:15) Kahinno saro isan sho. – The man hit the house with a rock.

The first example above is the standard form, while the second example is the colloquial

form with marking particles dropped. Most Setvayajan speakers consider this form of

object marker dropping to be incorrect at best, and a sign of poor education at word.

Direct Objects

When a direct object appears in a sentence, it is marked by the direct object marker to unless

the direct object is preceded by a preposition. When preceded by a preposition, the direct

object marker is dropped. When a preposition is not used, the to marker is always placed

immediately before the direct object. If the direct object is preceded by a modifier, the to

marker is placed before the modifier.

(cid:15) Miraino kau to isan. – I saw the house.

(cid:15) Miraino kau to mur gi isan. – I saw the red house.

Indirect Objects

Like direct objects, unless a preposition is used, indirect objects are preceded by the marker

ni. This marker gets used more often than the direct object marker as a stand-in for prepo-

sitions, but at the same time requires clear context for this purpose. In the same way as

for the to marker, if a modifier is used with the noun, ni is moved before the modifier.

(cid:15) Kahinno kau to atnal ni sho. – I hit the door with a rock.

(cid:15) Kahinno kau to skoi gi atnal vo sho. – I hit the tall door with a rock.

3.1.2 Determiners

Determiners help to determine what the noun or noun phrase is referring to. These include

articles, demonstratives, and interrogative determiners. Here, only the articles, quanti-

fiers, and the interrogative determiners will be discussed. Other determiners have their

own sections. In Setvayajan, they work like adjectives do, and come before the nouns they

determine.

Definite And Indefinite

By default, all nouns in Setvayajan can be either definite or indefinite, and definiteness or

indefiniteness is translated depending upon context. However, when a Setvayajan speaker

feels the need to specify something in particular, the demonstrative pronouns are used as

modifiers:

(cid:15) ban gi ts¯an – this tree

(cid:15) ras gi ts¯an – that tree

3.1. NOUNS

(cid:15) maz gi ts¯an – that tree there

17

In a similar way, if a Setvayajan speaker needs to specify indefiniteness, it uses the number

kal, meaning one:

(cid:15) kal gi ts¯an – a tree

(cid:15) kal gi isan – a house

(cid:15) kal gi saro – a man

Quantifiers

Quantifiers determine the amount of something. There are just four in Setvayajan:

(cid:15) sir – all, every

(cid:15) nith – many, much

(cid:15) siman – some

(cid:15) ¯al – litte, few

Siman can be used to mark indefiniteness, though this is used more specifically to indicate

an indefinite group of something:

(cid:15) siman gi ts¯an – some trees/trees

(cid:15) siman gi isan – some houses/houses

(cid:15) siman gi saro – some men/men

Interrogative Determiners

Interrogative determiners are used to ask questions. In English they are often called wh-

questions because all except how begin with wh-.In Setvayajan, they are all distinct and don’t

share a similar form:

(cid:15) mai – what, which

(cid:15) ao – when

(cid:15) n¯o – where

(cid:15) gyo – how

18

3.1.3 Possession

CHAPTER 3. NOUNS

Possession in Setvayajan was formed originally by the suffix -han. Over time, this suffix

expanded into three forms due to sound changes in the language, and the form used de-

pends on the final sound of the word it is suffixed to. While the possessive suffix comes

in three forms, the rules for which form to use are based around sound change rules for

/h/, and application to the noun is simple. In terms of word order for possessed nouns, the

possessed noun always precedes the possessor, and both are preceded by the direct and

indirect case markers when used.

(cid:15) Possession suffix rules:

– -han/-an/-yan

(cid:3) -han: follows any word ending in a vowel

(cid:3) -an: follows any word ending in voiceless stops

(cid:3) -yan: follows any word ending in consonants other than voiceless stop.

(cid:15) Examples:

– Isanyan saro. – The man’s house.

– Amuhan khakyath. – The khakyath’s meat.

– Kahinno h¯an to tsuohan saro. – The woman hit the man’s head.

– Ilevyan j¯al. – The town’s marsh.

– Byanyan s¯ath. – A person’s self.

Use of Possessives in Sentences

When used in complex sentences where case marking particles are used, the possessed

noun must follow the appropriate case markers, or take the type of case marker indicated

by the pronoun if followed by one:

(cid:15) Miraiyo kau to isanyan tsula. – I look at your house.

(cid:15) Makono kau to sengyan saro. – I cooked the man’s food.

3.1.4 Plurals

Setvayajan has a couple of pluralizing methods. The most basic is a plural like the En-

glish plural, a simple suffix added to the ends of nouns. Plurals of this type are the most

frequently encountered plural in the language.

It takes different forms depending on

whether the root word ends in a vowel, diphthong or consonant:

(cid:15) Root ending in a vowel or -au: -yu

– banta – boat > bantayu – boats

3.1. NOUNS

19

– ilau – flame > ilauyu – flames

– sori – star > soriyu – stars

(cid:15) Root ending in a consonant or diphthong (except -au): -u

– ¯asei – ice > ¯aseiu – ices

– h¯an – woman > h¯anu – women

– d¯ath – hill > d¯athu – hills

As a straightforward way to say ”two of something”, the dual number is largely restricted

to things perceived by the Setvai to come in pairs naturally, such as eyes. However, it is

on occasion used as a derivational affix, in which case it can create an unexpected change

in meaning from what is expected based on the root noun. When used for things that

the Setvai perceive as coming in pairs, it is not considered a derivational affix, taking two

forms depending upon whether the noun begins in a consonant or a vowel or diphthong:

(cid:15) ¯o-: for words beginning in consonants

(cid:15) ¯oy-: for words beginning in vowels or diphthongs

The form ¯oy- is used to prevent altering the initial vowel or diphthong of the noun. Be-

cause of the phonetic rules governing long vowels, if root contains a long vowel in the first

syllable, this long vowel is lost.

(cid:15) With nouns perceived as coming in pairs:

– ¯otana – hands

– ¯oyori – eyes

– ¯ocho – feet

(cid:15) With other nouns (and also modifiers), the affix used to derive new words:

– ¯o + ¯ınausu (child) > ¯oinausu – twin (hypercorrected to ¯oinausuyu to mean twins)

– ¯o + sitau (knife) > ¯ostau – a knife with two cutting edges, a kind of dagger

– ¯o + zhukh (ugly) > ¯ozhukh – horrendously ugly

(cid:15) With names or words referring to people, the implied meaning is ”that person and

their counterpart”, referring to someone in a relationship of some sort as the person

. This use is very colloquial and slangy use, however.

– ¯osaro – man and his spouse

– ¯oyata – animal and its mate

– ¯oy¯ınausu – child and their parent

20

CHAPTER 3. NOUNS

3.1.5 Noun Derivation

Setvayajan creates new nouns by two processes: compounding and affixing. While words

do get borrowed, Setvayajan speakers will more often coin a new word based on the mean-

ing of the original word, or create one by forming a compound. If a word is not easily

coined, created via compounding, or it’s shorter and simpler, then a Setvayajan speaker

may borrow the word instead. Borrowing is more prevalent if the word comes from a lan-

guage with status, such as Vos¯ath.

Compounding is probably the simplest of the two derivational methods. The base noun

is preceded by a word that modifies the base noun, whether it is another noun, modifier,

or verb root. New compounds often escape the initial effects of Setvayajan phonotactics,

but after a short period of time, the compound is perceived as a single word and regular

phonotactic processes begin to change the word.

Setvayajan is quite rich in affixes to derive new nouns. Most are suffixes, but there are a

handful of prefixes, and some infixes (affixes with go within the root word). Because af-

fixes create new words, the original root words can be obscured by phonotactic processes,

hiding the etymology. In the following list, if there are multiple versions of the affix, it

means the specific form is used depending on a preceding consonant or vowel. The first

version is the primary form, followed by possible changes due to phonotactics. See the

section on phonotactics for reference.

(cid:15) Place:

– Place described by the root, place of: -har, -yar (after consonants)

– Originating from (also used for abstract ideas of a similar vein): gau-, go-

– Where something happens regularly: -ten, -den

– Place intended for something: -ky¯o

– Something done at a specific place: -es

– Settlment, town: -j¯a

– Country name: -toza, -doza, -tsa, -dza

(cid:15) Time:

– Time something happens: -azin, -zin

– Time in which something is done: -ran, -dan

– Season something happens: -ivas, -vas

– Occurrence/event of something: -on

– Rite, ritual, ceremony: -tava, -tva

– An organized event based on the root: -rendan, -dendan

3.1. NOUNS

(cid:15) Role:

21

– Someone or something who does something as a role: -tan, -dan

– Someone or something that acts as or does something: -ho

– Someone who does something as a profession: -sin, -zin

– Someone or something associated with the root (inherent): -su

– Someone or something that uses the root in some way: -reyo, -deyo, -jo

– Someone or something that causes the root to happen or something to become

the root: te-, ch-

– Someone or something that replaces or imitates the root: -kren

(cid:15) Tool:

– Something used to perform an action: -ith

– Something used to measure or contain what’s referenced by the root: -nan

(cid:15) Result:

– An object or result of the root: -al

– Something made into what the root describes: -mur

– XXX something made out of what the root describes: -soi, -zoi

– Something in the form of or derived from the root: -v¯a

(cid:15) State:

– The state, quality or condition of something: -ro, -do

(cid:15) Act/Process or Verb based nouns:

– Based on verbal roots, can be translated to ”act of” though not always. Tends

to describe the process indicated by the root, but also used for simple verbal

nouns: -ram, -dam

(cid:15) Relationships:

– Persons or things in a relationship expressed by the root: -sem, -zem

– A reciprocal relationship based on the root: -um

(cid:15) Abstract nouns:

– Nouns based on an abstract idea or quality: -ar

Note: -ar is the preferred form for abstract ideas or qualities as nouns, rather

than the plain root.

22

CHAPTER 3. NOUNS

(cid:15) Collectives and Measurement:

– A group of things referenced by the root: -bara, -bra, -para, -pra, -vara, -vra

– A large number of things, generally uncountable: -ika

– A measured quantity of something: -shor, -zhor

(cid:15) Perjorative:

– Simple pejorative (often productive for insults): -rakh, -dakh

– Diminutive pejorative (implying a lesser version/quality): -dir, -tir, -zir

– Used with moods, feelings, and emotions to denote the negative opposite: kyo-

(cid:15) Miscellaneous Suffixed Affixes:

– Something done excessively or repeatedly: -bos, -pos, -vos

– Something done for the benefit of someone or something: -is

– Something incomplete, broken or not quite right: -maka, -ngka

– Doctrine or theory of something: -eth, -jeth

– Originating from, pertaining to: -ajan

– Honorific used at the end of given names: -le

(cid:15) Miscellaneous Prefixed Affixes

– Augmentative (a larger version): si-, sh-

– Without: iras-, irash-

– Someone or something that is: ya-

– Someone or something that is not: van-

– Two of something in a pair: ¯o-

– Resembles/similar to/like: ar-

(cid:3) Becomes infixed if the root begins in a consonant: kar ¯on – ”grasslike” (from

k¯on – ”grass”)

Chapter 4

Pronouns

Setvayajan pronouns are divided into personal, demonstrative, indefinite and interrog-

ative pronouns. There are forms for subject, direct object and indirect object pronouns.

Originally, these were all the same in form but marked with the to and ni markers. Over

time, the direct and indirect object markers became prefixed to them, often changing their

origin.

Originally, only the singular personal pronouns had polite forms. Later, politeness was

extended to all pronouns referring to people using the -le politeness suffix which was

originally used only with names when addressing people (it still keeps this function).

Formation was originally regular, but sound changes have caused changes in form, and

the origin of some of the polite pronouns is obscurred. Others are obvious by a final -l.

Sound changes also caused a few familiar and polite forms of the demonstrative pronouns

to merge, and to correct this, Setvayajan speakers added the -le politeness suffix to these

again (which whittled down to -l due to sound changes), creating regular polite forms.

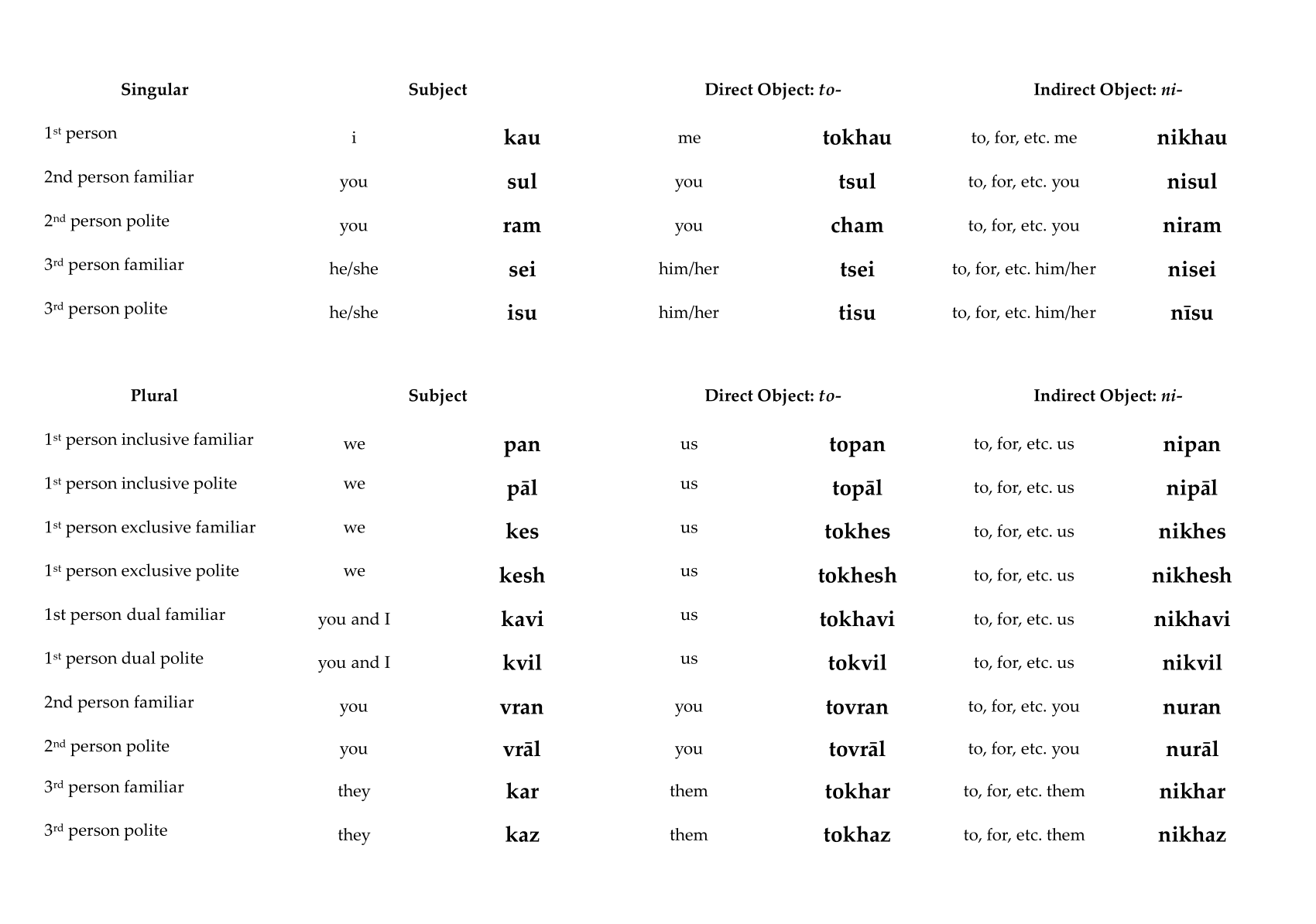

4.1 Personal Pronouns

The personal pronouns in Setvayajan are more complex than they are in English, as in some

instances there is no one to one correlation between Setvayajan and English pronouns.

Setvayajan pronouns also take into account politeness, requiring a specific pronoun based

upon the relative difference in social status between the speaker and the listener or those

the speaker is discussing.

Aside from the polite forms, you’ll notice some differences from what English has. There

is a first person dual form, which includes just the speaker and the listener but no one else.

This form is usually used in cases where the action happens simultaneously to both the

speaker and the listener, a shared experience. It is also used when the action is reciprocal

between the two.

The other major difference are the two forms of first person plural pronouns that are in-

clusive and exclusive. These forms are used to established who did what with the speaker.

23

24

CHAPTER 4. PRONOUNS

Figure 4.1: Setvayajan Personal Pronouns

The inclusive form is used to discuss things that the speaker and others did that also in-

clude the listener. The exclusive form is used to speak about things that the speaker and

others did, but not the listener.

The polite forms are numerous, and aside from the first person singular, there are polite

forms to match the familiar. These polite forms are used based upon the relative distance

socially between the speaker and those they are discussing. Politeness levels are not quite

as complex as they are in languages like Japanese or Javanese (there are no special word

forms aside from the pronouns for marking polite speech), but one must take into account

where they stand compared to where others stand. Usage of the familiar and polite pro-

nouns is explained below:

(cid:15) Familiar forms:

– Used by adults to speak to children

– Used among friends

– Used with those of equal social status

– Older people to younger people

4.1. PERSONAL PRONOUNS

25

– Superiors to subordinates

(cid:15) Polite forms

– Used by children to speak to adults

– Used among younger peer groups to older peer groups

– Used with those of unequal social status but not always one where the differ-

ence is great, such as classmates in more junior levels to more senior levels

– Among colleagues at work unless they have become friends or have equal status

– Younger people to older people

– Subordinates to superiors

– Between strangers (of about equal or older age)

– Non-native speakers to native Setvayajan speakers (non-native speakers are ad-

vised to use these forms)

4.1.1 Non-Gendered Pronouns

Setvayajan pronouns are genderless, which is why sei and isu are translated as he/she. These

pronouns say nothing about the gender of the person they are being used for other than

that one is speaking about a person. Without there being a gender distinction, it might

sound like these pronouns can be used for talking about things, where we would use it in

English. This is not permitted as these pronouns are used strictly for discussing people.

How does Setvayajan discuss things without having to name them all of the time if there

is no pronoun for it? It resorts to using demonstrative pronoun:

(cid:15) Suvaru kau tofan. – I’m eating it (this)

(cid:15) Suvaru kau chas. – I’m eating it (that)

(cid:15) Suvaru kau tomaz. – I’m eating it (that there)

A more formal way of using the demonstratives sees them used as demonstrative adjec-

tives linked to the noun kor, meaning thing. For this construction, the direct object marker

to is omitted because the demonstrative adjectives are used in their direct or indirect object

forms and so to is unnecessary:

(cid:15) Suvaru kau tofan gi kor. – I’m eating it (this thing)

(cid:15) Suvaru kau chas gi kor. – I’m eating it (that thing away from me)

(cid:15) Suvaru kau tomaz gi kor. – I’m eating it (that thing out of reach from me)

26

CHAPTER 4. PRONOUNS

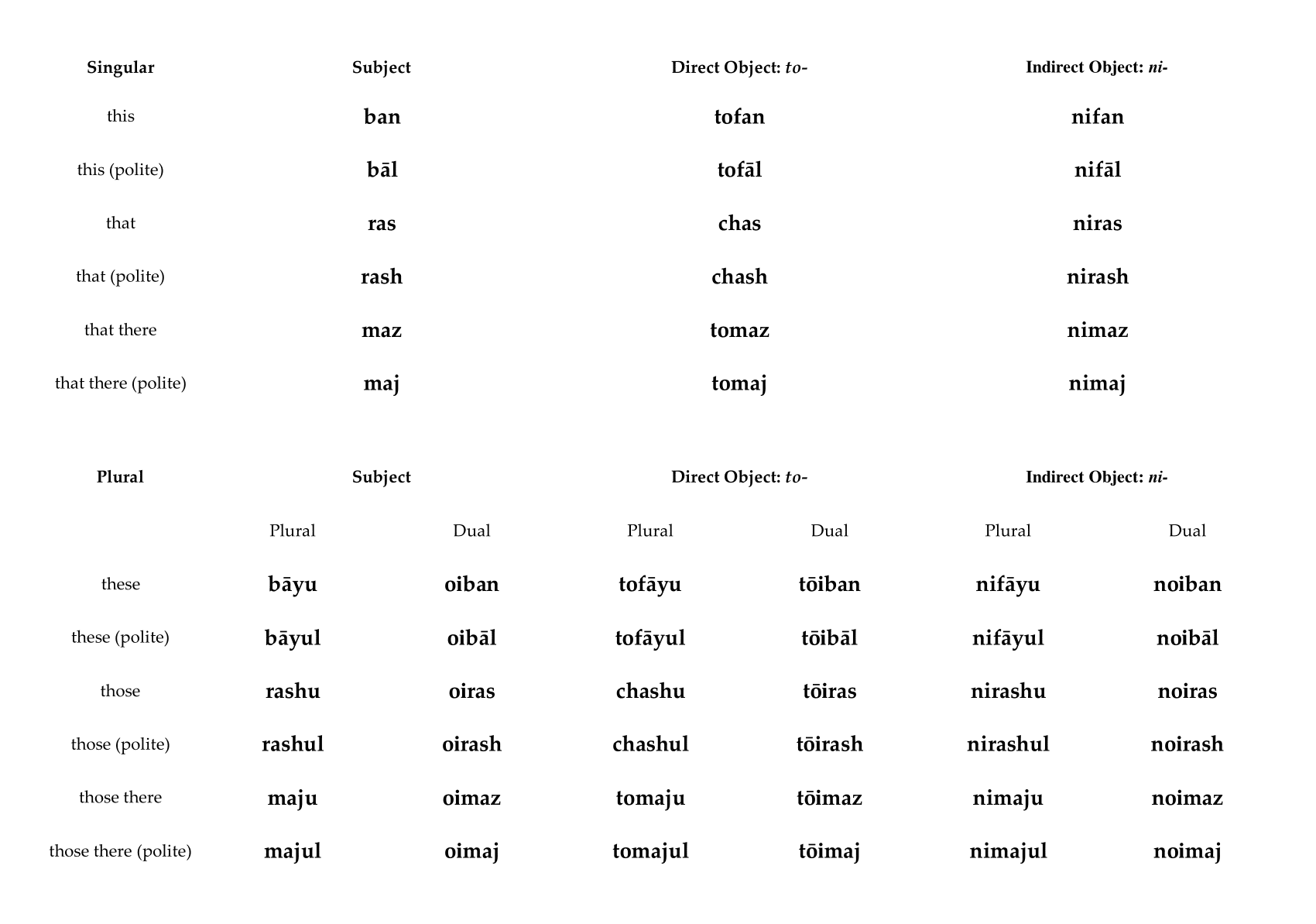

4.2 Demonstrative Pronouns

Demonstratives are words which ”point out” what someone is referring to based upon the

distance between the speaker relative to the listener and whatever they are discussing.

Figure 4.2: Setvayajan Demonstratives

Setvayajan’s demonstratives are split three ways; near, away, and distant. English has a two

way distinction which is why the translation of maz and maj is that there, though translating

them as just that suffices. When to use maz and maj depends upon how far away something

is from the speaker. Generally speaking, if the object requires getting up or travel, then

maz and maj are used. There aren’t guidelines as to when to use which, and usage can even

vary between two speakers next to each other and their estimation of how near the object

is. There are also plural forms for the regular plural, and also for items that come in pairs

(dual). The dual is used much less often than the plural, but it is important to know the

forms for it. In addition there are direct and indirect object forms which are irregular and

must also be learned as well.

4.2. DEMONSTRATIVE PRONOUNS

27

4.2.1 Demonstrative Adjectives

Like the interrogative pronouns, the demonstrative pronouns can also be used as adjec-

tives. Like other adjectives, they are linked to their following noun or pronoun with the

gi linking particle:

(cid:15) Ban gi ts¯an. – This tree.

(cid:15) Ras gi sho. – That rock.

(cid:15) Maz gi isan. – That house (there).

When used as modifiers, they don’t take the sa- derivatonal affix, but they must be followed

by the linking particle gin. Also, when the noun they modify is the object or indirect object

of the sentence, the demonstratives take their direct or indirect object forms instead of the

subject form being preceded by the direct or indirect object particles:

(cid:15) Miraino kau chas gi isan. – I saw that house.

(cid:15) Suvano kau to seng maz gi isan. – I ate food at that house (there).

However, when a preposition is used, the subject form is used instead:

(cid:15) Suvano kau to seng de maz gi isan. – I ate food at that house.

28

CHAPTER 4. PRONOUNS

4.3 Indefinite Pronouns

Indefinite pronouns refer to non-specific things, beings, and places. Setvayajan’s indefinite

pronouns started out quite regular but over time, they experienced phonetic changes that

helped to reduce their length and obscure their origin. These changes were not at all

regular across all of the indefinite pronouns, as some of them were altered to level out with

similar indefinite pronouns or two indefinite pronouns from becoming the same word.

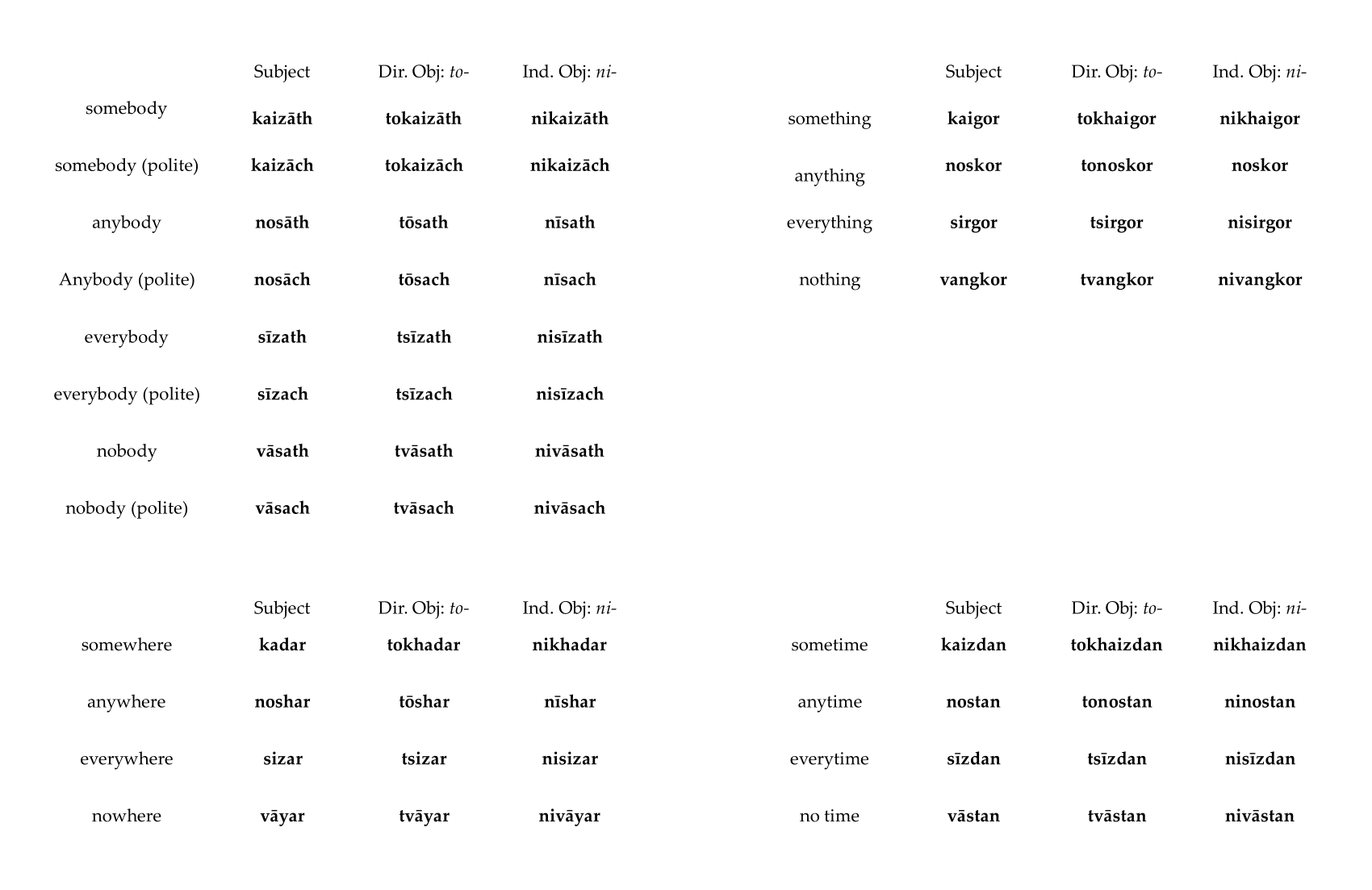

Figure 4.3: Setvayajan Indefinite Pronouns

4.3.1 Existentials as Indefinite Pronoun Replacements

Setvayajan allows the positive and negative existentials ko and ¯az to act as pseudo-indefinite

pronouns. This use is contextual based upon the verb and the agent of the verb. Even so,

at times the meaning can be ambiguous, though context of the conversation should still

clarify what is meant. For these, they are placed before the conjugated verb:

(cid:15) Ko suvano kau. – I ate something.

(cid:15) ¯Az rahano kau. – I cut nothing/no one.

If the statement is to be made negative, then the verb must have the negating prefix va-

added:

4.4. INTERROGATIVE PRONOUNS

29

(cid:15) Ko vasuvano kau. – I didn’t eat anything.

(cid:15) ¯Az varahano kau. – I didn’t cut anything/anyone.

The previous examples would require a preceding statement in order to give proper con-

text for their use (unless the speaker was intentionally trying to be as ambiguous as pos-

sible). Here’s a more proper example:

(cid:15) Ko liha gi seng, ko suvano kau. – There was a lot of food, I ate everything.

For more on the existentials, please see section 8.7.

4.4 Interrogative Pronouns

Interrogative pronouns are used to ask questions. In English, these are usually called wh-

words, however in Setvayajan, they do not share a common initial sound as they do in

English. Setvayajan’s interrogative pronouns are a bit different than English in that there

are familiar and polite forms. Another difference between Setvayajan and English is that

the interrogative pronouns are not used as relative pronouns.

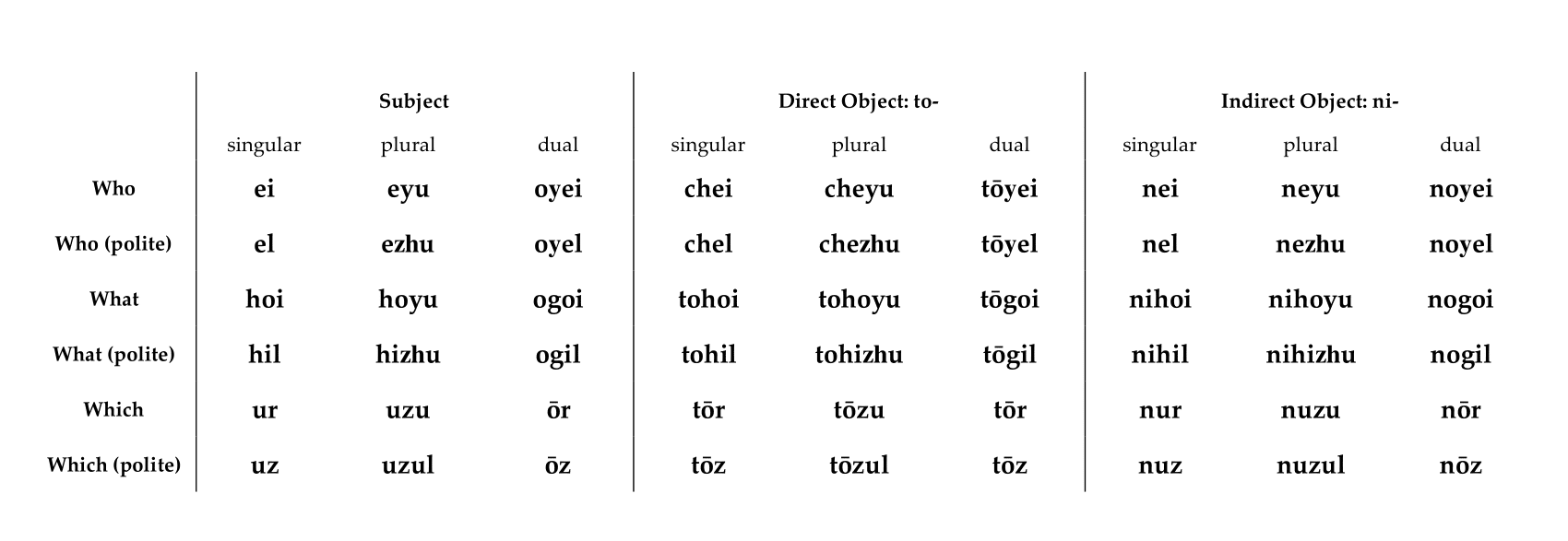

Figure 4.4: Setvayajan Interrogative Pronouns

The three basic interrogatives have polite forms in addition to their basic forms. These

forms are used when talking about not only people of a higher status than the speaker,

but for what and which objects which are held in high esteem:

(cid:15) Suvano ei to seng? – Who ate the food? (familiar)

(cid:15) Suvano el to seng? – Who ate the food? (polite)

(cid:15) Suvano hoi to seng? – What ate the food? (familiar)

(cid:15) Suvano hil to seng? – What ate the food? (polite)

(cid:15) Suvano ur to seng? – Which ate the food? (familiar)

30

CHAPTER 4. PRONOUNS

(cid:15) Suvano uz to seng? – Which ate the food? (polite)

When the interrogative pronouns are used, they are treated in the same manner as per-

sonal pronouns, following the normal placement of subjects, objects, and indirect objects:

(cid:15) Suvayo ei chas? – Who is eating that?

(cid:15) K¯amano sei gau tohoyu? – What did he talk about?

(cid:15) Tadavathyo sei t¯or? – Which will she sell?

4.4.1 Interrogative Adjectives

The interrogatives can also be used as adjectives as they are in English. They are linked to

their nouns in the same way as any other adjective:

(cid:15) Hoi gi isan? – What house?

(cid:15) Uzu gi ts¯anyu? – Which trees?

– Alternately, the plural ending -yu can be omitted from ts¯an, as plurality is stated

by uzu:

(cid:3) Uzu gi ts¯an? – Which trees?

(cid:15) Ei gi maz? – Who’s that over there?

Notice that in English, the interrogative pronoun normally comes at the very beginning of

the sentence (though, English isn’t absolutely strict about this). In Setvayajan, the normal

way of using them is as was explained to treat them as the personal pronouns are treated.

However, if the interrogative pronoun is intended to be emphasized, they will always come

before the verb, but the translation can change:

(cid:15) Ei suvayo t¯am? – Who is eating that?

(cid:15) Gau tohoyu k¯amano sei? – Of what did he speak?

(cid:15) T ¯or tadavathyo sei? – Which will she sell?

4.5 Subject Dropping

Subject dropping refers to the practice of omitting already established subjects of sen-

tences. Because direct and indirect objects are always marked, either through the direct

and indirect object particles or by prepositions, this allows the subject pronouns which

are not marked, to be omitted. Subject dropping is standard practice and for Setvayajan

speakers it feels odd to hear an already established subject to be mentioned in every sen-

tence while the subject is the topic of conversation. In fact, Setvayajan speakers introduce

a new topic by introducing a subject after the verb in a new sentence.

4.5. SUBJECT DROPPING

31

(cid:15) Makono saro to ama, suvano (sei) chas. – The man cooked the meat, (he) ate it.

(cid:15) Miraino kali to saro, miraino (sei) de tsaya. – The woman saw the man, (she) looked at

him.

(cid:15) Usavno ata de svati, demo, (ora) skara t¯or usavno. – The animal walked to the river, (it)

walked along it later.

In the above examples, the subject pronouns (in italics) have all been dropped. They’ve

been established in the first part of each sentence and so there is no need to mention them

again in the second part of each sentence. In very colloquial Setvayajan, if a following

clause or sentence is talking about the previous clause or sentence, the subject, direct ob-

ject, and indirect object can be dropped, leaving a bare verb and sometimes a following

preposition. This construction can be very vague and confusing and is considered im-

proper. It is avoided in all but the most informal of situations:

(cid:15) Makono saro to ama, suvano (sei t ¯or). – The man cooked the meat, (he) ate (it).

(cid:15) Miraino kali to saro, miraino (sei) de (tsaya). – The woman saw the man, (she) looked

at (him).

(cid:15) Usavno ata de svati, usavno (ora) skara (t ¯or) demo. – The animal walked to the river,

later, (it) walked along (it).

The interesting thing about this construction is that Setvayajan permits prepositions to

remain without standing before nouns or pronouns. Of course, as explained, this is very

colloquial and is not permitted in standard or even normal Setvayajan conversation. Keep

in mind that in standard sentences, prepositions cannot sit at the end of sentences because

they will always be required to precede a noun or pronoun.

32

CHAPTER 4. PRONOUNS

Chapter 5

Modifiers

Setvayajan doesn’t make a distinction in a formal sense between adjectives and adverbs

and in fact, there isn’t a suffix that generally marks adverbs. Because there isn’t a real

distinction between adjective and adverb except by the word being modified, it is more

accurate to call all describing words modifiers instead. However, to simplify things in this

document where appropriate, adjective and adverb will be used to clarify when necessary.

Modifiers can come from a variety of sources; roots, nouns, compound words, or affixes.

WWhat signifies that a modifier is being used is the linking particle gi, which is placed

between the modifier and the modified word.

(cid:15) Mur gi isan. – The red house.

(cid:15) Suvano gi reko kau. – I ate quickly.

5.1 Modifier Placement

There are certain standard rules for modifier placement. Typically, in a verbless sentence,

adjectives normally come before nouns and pronouns. When used in a sentence with

verbs, adjectives tend to come after the noun or pronoun except in certain set phrases or

names for things. With adverbs, things are a little bit trickier. Most commonly, the adverb

comes after the verb and before the subject, object, or indirect object. When an auxiliary

verb is used, adverbs sit between the infinitive and the conjugated verb, linked to the

infinitive. However, if the speaker wants to emphasize the adverb, most commonly done

with adverbs of time, the adverb is placed before the verb:

(cid:15) Mur gi isan. – The red house.

(cid:15) Miraino kau to isan gi Mur. – I saw the red house.

(cid:15) Suvaru gi reko kau. – I eat quickly.

(cid:15) Suvath gi reko metaru kau. – I want to eat quickly.

(cid:15) Demo gi tasuvaru kau. – Later, I’ll eat.

33

34

CHAPTER 5. MODIFIERS

While the placement described is standard, Stevayjan allows some leeway, especially for

poetic purposes, but also if the speaker thinks it sounds better, and only if the meaning is

clear. It’s not uncommon for a sentence like Suvaru gi reko kau to be rearranged as Suvaru

kau gi reko, but this works only because reko in the context of that sentence means quickly.

5.2 Modifier Formation and Derivation

While roots that aren’t modifiers can be turned into modifiers by the linking particle, the

standard way to indicate that a non-modifier root is being used as a modifer is to use the

prefix sa-, s-. This prefix takes two forms depending upon the initial sound of the root.

For roots that begin in consonants, it takes the form sa-. If the root begins in vowels or

diphthongs, it becomes s-.

(cid:15) sa- + k¯on (grass): sak¯on – grassy

(cid:15) sa- + dal (strength): sadal – powerful

(cid:15) sa- + hing (spice): sahing – spiced, seasoned

The sa-, s- prefix is a newer method of forming modifiers. An older, alternate method used

the existential ko (there is, there are) as a prefix, ko-. As the prefix sa-, s- increased in use,

modifiers using ko- were reduced to a handful of modifiers with different meanings than

what they originally had. Originally it had stopped being a productive affix except with

roots that begin with sa- or s¯a-, although it is seeing a resurgence in colloquial speech:

(cid:15) Old ko- modifiers:

– ko + unai (joy): k¯onai – joyful > excited

– ko + inom (rest): kinom – rested > unconscious

– ko + k¯on (grass): kok¯on – grassy > overgrown

(cid:15) Sa roots with ko-:

– ko- + sato (to be acquainted): kosato – acquainted with, known to someone

– ko- + saka (cycle): kosaka – cycled, completed

– ko- + s¯ath (person, being): kos¯ath – human

5.2.1 Other Derivational Affixes

There are a number of affixes used to derive modifiers aside from the sa/s- affix. These

affixes sometimes can be used to form nouns in addition to being used to create modifiers.

(cid:15) -ajan, -jan: Originating from, pertaining to: setvayajan – of the Setvai, relating to the

Setvai

5.2. MODIFIER FORMATION AND DERIVATION

35

(cid:15) san-: having a large quantity of the root: sanvisai – gorgeous

(cid:15) -soi, -zoi: made of: kalisoi – golden

(cid:15) gaw-, go-: originating from: gojin – from mountains

(cid:15) sa-, s-: abundance, fullness: sunai – joyful

(cid:15) dil-, ju-: likeness, similarity to: jujin – mountain-like

(cid:15) va-, v-: not, similar to ”un/in” in English: vaksai – unholy

(cid:15) ras-, raz-, rash-: lacking, without: razdal – weak

(cid:15) -y¯a. -ya: shaped, shaped like: talay¯a – crystal shaped

36

CHAPTER 5. MODIFIERS

Chapter 6

Verbs

Setvayajan verbs are the first part of the sentence unless negated, preceded by adverbs or

if a noun or pronoun is topicalized. They are formed from roots and conjugated through

affixes. These affixes are applied in a regular order, which is the easy part of verb con-

jugation in Setvayajan. On the other hand, knowing which affix to use is often the most

difficult part.

(cid:15) The order of affixes on the verb root is applicative – causative – verb root – aspect –

tense

Setvayajan doesn’t allow for shifting these elements around, but their use is straightfor-

ward. Although it is theoretically possible to have every single category applied to a verb

root, it is unlikely to be encountered frequently. The most commonly encountered combi-

nations are root – tense, or root – aspect – tense.

6.1 The Infinitive

The infinitive in Setvayajan developed originally as a nominalization of the verb root.

While the infinitive in Setvayajan is used to form the dictionary form of the verb (the base

form), in addition it is also used to form the gerund, the imperative, and to allow verbal

roots to stand on their own as finite verbs. Setvayajan also uses the infinitive to form verb

phrases consisting of the infinitive followed by an auxiliary verbs.

In Setvayajan, the infinitive, gerund and the imperative all share the same suffix, -soi. It’s

important to note that words ending in -soi

(cid:15) Infinitive: k¯amasoi – to speak

(cid:15) Gerund: am k¯amasoi – the speaking

(cid:15) Imperative: K¯amasoi sula! – Speak!

37

38

6.1.1 Gerund

CHAPTER 6. VERBS

Gerunds in Setvayajan are verbal nouns that name the action, rather than the result of

the action. They describe the verb as a noun. In translation into English, they would be

translated with the -ing suffix. In form, they take the same ending as the infinitive, -soi.

These are then treated as a noun, and can take other affixes as necessary:

(cid:15) Ezosoyan kau. – My thinking.

(cid:15) Am rahasoi. – The cutting.

As with any noun, they also take the direct and indirect object markers if they take that

role within a sentence:

(cid:15) Sanasoyan tokau. – I have my dreaming.

While they are a type of verbal noun, they’re different from basic verbal nouns in that they

can also act in a verbal way:

(cid:15) Rahasoi to kari kai tsaya. – Cutting fruit for him/her.

6.1.2 Imperative

In short, imperatives are commands. In forming the most basic imperative, it can appear

as the infinitive as they share the same form, but intonation and context clarifies that what

is said is in fact the imperative and not the infinitive. As the imperative can only be a

command from a speaker to the listener or listeners, the firse person singular pronouns

cannot be used, but because the first person plural pronouns also include listeners, they

are used with the imperative. Second person familiar pronouns are not usually used if it is

understood that the imperative is being used, but when using the imperative with people

of higher social status, the polite pronouns must always be used.

While the familiar form of the pronoun is usually omitted, they can be added if the intent

may be unclear, or if the speaker believes the imperative may be mistaken for the infinitive

or the gerund. When the second person familiar pronouns are used, they emphasize that

the speaker is talking to the listener, and are always placed before the verb. The second

person polite pronouns are never put before the verb as this is seen as rude):

(cid:15) Sul suvasoi! – You eat!

(cid:15) Suvasoi ram! – You eat! (polite)

When the first person plural pronouns are being used with the imperative, a slight change

in translation happens. Because they include the speaker, the meaning changes to some-

thing more like ”let’s…”, but the meaning can also be a more literal ”We…”

(cid:15) Suvasoiru pan. – Let’s eat. or ”We eat.”

6.2. TENSE AND ASPECT

6.2 Tense and Aspect

39

Tense and aspect describe the timeline upon which the verb happens. Tense tells when

the action occurred, while aspect tells how the action relates to the flow of time. Aspect

is not the same as tense in that the aspects can happen at any point on the timeline: past,

present, and future.

6.2.1 Tenses

Setvayajan has three tenses: past, present and future. While the three tenses are formed

by suffixes, Setvayajan speakers will often omit the present tense suffix if context allows

and if the verb is obvious. Many times, the present tense suffix is used to mean right now.

(cid:15) Past: -no: suvano – ate

(cid:15) Present: -ru: suvaru – eat

(cid:15) Future: ta- -ru: tasuvaru – will eat

All three tenses can appear in more than one form due to sound changes involving /R/

when it comes into contact with a preceding consonant. These forms can appear to be

irregular, though with an understanding of the sound changes, they are actually quite

regular.

Past Tense:

The past tense takes the suffix -no:

(cid:15) aten + -no: atenno – opened

(cid:15) saka + no: sakano – cycled

(cid:15) uram + no: uramno – touched

Present Tense:

The present tense takes the suffix -ru/-du/-tu depending upon the final sound of the verb

root. The rule for determining this is:

(cid:15) Any word ending in a vowel or diphthong use -ru

(cid:15) When /R/ follows /s/ and /S/, -ru becomes -tu

(cid:15) When /R/ follows /l/, /n/, /z/ and /Z/, -ru becomes -du

(cid:15) If the previous syllable contains /R/, -ru becomes -du

Examples:

40

CHAPTER 6. VERBS

(cid:15) ato + -ru: atoru – resting

(cid:15) h¯aros + -ru: h¯arostu – honoring, celebrating

(cid:15) sanan + -ru: sanandu – shaking, trembling

(cid:15) vora + -ru: voradu – sending, transmitting

Future Tense:

The future tense is unique in that it is a circumfix (it surrounds the root), and it is thought to

have the same origin as the verb root etam (go, going), reduced to ta-. As with the present

tense suffix, -ru in the future tense also experiences changes depending upon the final

sound or syllable of the root word.

(cid:15) ta + ato + -ru: t¯atoru – will rest

(cid:15) ta + h¯aros + -ru: tah¯arostu – will honor/celebrate

(cid:15) ta + sanan + -ru: tasanandu – will shake/tremble

(cid:15) ta + vora + -ru: tavoradu – will send/transmit

6.2.2 Aspects

The aspects in Setvayajan are six in number: cessative, continuous, habitual, inceptive,

inchoative, and perfective. They originated from auxiliary verbs which eventually became

reduced and then affixed to the root verb. XXX These aspects clarify how the verb relates

to the flow of time, giving a little more information about the state of the action of the

verb.

(cid:15) Cessative: -kar – The cessative indicates that the action has stopped/finished hap-

pening. It can be used for both dynamic actions and those that relate to states.

(cid:15) Continuous: -ne – The continuous indicates that an action is ongoing. When trans-

lating verbs marked by the continuous with a tense suffix, the sense is progressive,

though when used with the past tense it can also mean a habitual action.

(cid:15) Habitual: -ri – The habitual indicates that an action is performed by the agent rou-

tinely. When used with the past tense affix, it translates to ”used to”

(cid:15) Inceptive: -sa – The inceptive indicates that a dynamic action is starting to happen.

It is not used for actions that describe a state, or those which are ongoing.

(cid:15) Inchoative: -to – The inchoative on the other hand is used to indicate that a state has

begun to happen to something.

(cid:15) Perfective: -li – The perfective indicates that he action has completed at some point

in time. When translating verbs marked by the perfective with tense suffix, the sense

is ”had/have/will have”

6.3. APPLICATIVES

6.3 Applicatives

41

The applicatives were derived from prepositions and work to move an indirect object

into direct object position. The original direct object (if there was one) is usually deleted,

though it can still be added to the sentence in order to clarify context if needed. The ap-

plicatives are most useful with intransitive verbs, because they can turn the verb transitive.

However, when used with transitive verbs, the original direct object can be dropped in fa-

vor of the indirect object, or the verb then takes two direct objects becoming ditransitive.

Because of the way applicatives work, they can replace some prepositions, as long as the

context is clear. They also have had a history of being used to create new verbs, though

these have been worn down over time phonologically, creating a ”double applicative”, in

a sense.

For example, the verb root jokas means stare. While not apparent, this root contains the

de- applicative and the root okas (observe/watch). The original meaning would have been

observe/watch toward something. In modern Setvayajan, jokas can take the de- applicative,

creating dejokas – stare at.

(cid:15) Locative (happens at a place): ran- – The indirect object is a location

(cid:15) Directional (happens toward something): de-, dey- – The indirect object is where the

action is directed.

(cid:15) Benefactive (happens for someone or something): kai-, kay- – The indirect object has

something done for or on its behalf

(cid:15) Instrumental/Comitative (happens with a tool or with someone): vo- – The indirect

object is a tool used or is someone the action happens with.

6.4 Causatives

Causatives are used to indicate that the direct object has undergone some sort of action