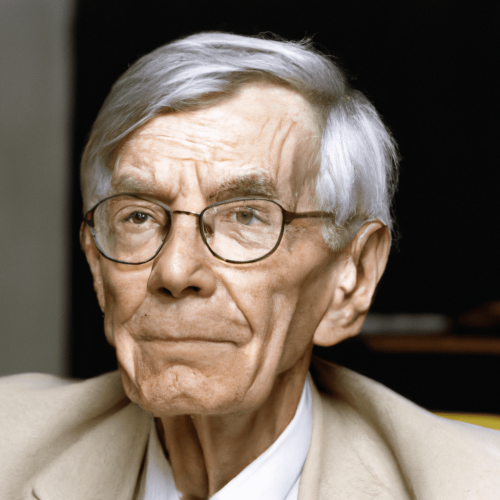

John Rawls (1921—2002)

John Rawls was arguably the most important political philosopher of the twentieth century. He wrote a series of highly influential articles in the 1950s and ’60s that helped refocus Anglo-American moral and political philosophy on substantive problems about what we ought to do. His first book, A Theory of Justice [TJ] (1971), revitalized the social-contract tradition, using it to articulate and defend a detailed vision of egalitarian liberalism. In Political Liberalism [PL] (1993), he recast the role of political philosophy, accommodating it to the effectively permanent “reasonable pluralism” of religious, philosophical, and other comprehensive doctrines or worldviews that characterize modern societies. He explains how philosophers can characterize public justification and the legitimate, democratic use of collective coercive power while accepting that pluralism.

Although most of this article will be devoted to TJ, the exposition of that work will take account of Political Liberalism and other later works of Rawls. TJ sets out and defends the principles of Justice as Fairness. Rawls takes the basic structure of society as his subject matter and utilitarianism as his principal opponent. Part One of TJ designs a social-contract-type thought experiment, the Original Position (OP), and argues that parties in the OP will prefer Justice as Fairness to utilitarianism and various other views. In order to understand the argument from the OP, one must pay special attention to the motivation of the parties to the OP, which is philosophically stipulated and provided with a Kantian interpretation. Part Two of TJ checks the fit between the principles of Justice as Fairness and our more concrete considered views about just institutions, thereby helping move us towards a reflective equilibrium that supports those principles. Part Three of TJ addresses the stability of a society organized around Justice as Fairness, arguing that there will be an important congruence in such a society between people’s views about justice and what they value. By the time he wrote Political Liberalism, however, Rawls had decided that an inconsistency in TJ called for recasting the argument for stability. In other ways, the argument of TJ rested on important simplifications, which had the effect of setting aside questions about international justice, disability, and familial justice. Rawls turned to these “problems of extension,” as he called them, at the end of his career.

Table of Contents

Biographical Sketch

Rawls’s Mature Work: A Theory of Justice (1971)

The Basic Structure of Society

Utilitarianism as the Principal Opponent

The Original Position

The Conditions and Purpose of the Original Position

The Motivations of the Parties to the Original Position

Kantian Influence and Interpretation of the Original Position

The Principles of Justice as Fairness

The Argument from the Original Position

Reflective Equilibrium

Just Institutions

Stability

Congruence

Recasting the Argument for Stability: Political Liberalism (1993)

Problems of Extension

References and Further Reading

1. Biographical Sketch

John Bordley Rawls was born and schooled in Baltimore, Maryland, USA. Although his family was of comfortable means, his youth was twice marked by tragedy. In two successive years, his two younger brothers contracted an infectious disease from him—diphtheria in one case and pneumonia in the other—and died. Rawls’s vivid sense of the arbitrariness of fortune may have stemmed in part from this early experience. His remaining, older brother attended Princeton for undergraduate studies and was a great athlete. Rawls followed his brother to Princeton. Although Rawls played baseball, he was, in later life at least, excessively modest about his success at that or at any other endeavor.

Rawls continued for his Ph.D. studies at Princeton and came under the influence of the first of a series of Wittgensteinean friends and mentors, Norman Malcolm. From them, he learned to avoid entanglement in metaphysical controversies when possible. Rawls’s doctoral dissertation (1950) already showed, however, that he would not be content to deconstruct our impulse to ask metaphysical questions; instead, he devoted himself to constructive philosophical tasks. Turning away from the then-influential program of attempting to analyze the meaning of the moral concepts, he replaced it with what was—for a philosopher—a more practically oriented task: that of characterizing a general method of moral decision making. Part of this dissertation work was the basis of his first published article, “Outline of a Decision Procedure for Ethics.” (1951). This was an early attempt to tackle the central question of Rawls’s mature theory: what sort of decision procedure can we imagine that would help us resolve disputed claims in a fair way?

Of equal significance to Rawls’s turn away from conceptual analysis and towards a more practical conception of moral philosophy was his encounter, during a year (1952-3) as a Fulbright Fellow in Oxford, with exciting, substantive work in legal and political philosophy, especially that of H.L.A. Hart and Isaiah Berlin. Hart had made progress in legal philosophy by connecting the idea of social practices with the institutions of the law. Rawls’s second published essay, “Two Concepts of Rules” (1955), uses a conception of social practices influenced by Hart to explore a kind of rule-utilitarianism. Compare TJ at 48n.. In Isaiah Berlin, Rawls met a brilliant historian of political thought—someone who, by his own account, had been driven away from philosophy by the aridity of mid-century conceptual analysis. Berlin influentially traced the historical careers of competing, large-scale values, such as liberty (which he distinguished as either negative or positive) and equality. Not long after his time in Oxford, Rawls embarked on what was to become a life-long project of finding a coherent and attractive way of combining freedom and equality into one conception of political justice. Cf. PL at 327. This project first took the form of a series of widely-discussed articles about justice published between 1958 and 1969.

After teaching at Cornell and MIT, Rawls took up a position in the philosophy department at Harvard in 1962. There he remained, being named a University Professor in 1979. Throughout his career, he devoted considerable attention to his teaching. In his lectures on moral and political philosophy, Rawls focused meticulously on great philosophers of the past—Locke, Hume, Rousseau, Leibniz, Kant, Hegel, Marx, Mill, and others—always approaching them deferentially and with an eye to what we could learn from them. Mentor to countless graduate students over the years, Rawls inspired many who have become influential interpreters of these philosophers.

The initial publication of A Theory of Justice in 1971 brought Rawls considerable renown. This complex book, which reveals Rawls’s thorough study of economics as well as his internalization of themes from the philosophers covered in his teaching, has since been translated into 27 languages. While there are those who would claim a greater originality for Political Liberalism, TJ remains the cornerstone of Rawls’s reputation.

2. Rawls’s Mature Work: A Theory of Justice (1971)

a. The Basic Structure of Society

The subject matter of Rawls’s theory is societal practices and institutions. Some social institutions can provoke envy and resentment. Others can foster alienation and exploitation. Is there a way of organizing society that can keep these problems within livable limits? Can society be organized around fair principles of cooperation in a way the people would stably accept?

Rawls’s original thought is that equality, or a fair distribution of advantages, is to be addressed as a background matter by constitutional and legal provisions that structure social institutions. While fair institutions will influence the life chances of everyone in society, they will leave individuals free to exercise their basic liberties as they see fit within this fair set of rules. To carry out this central idea, Rawls takes as the subject matter of TJ “the basic structure of society,” defined (as he later put it) as “the way in which the major social institutions fit together into one system, and how they assign fundamental rights and duties and shape the division of advantages that arises through social cooperation.” PL at 258. Rawls’s suggestion is, in effect, that we should put all our effort into seeing to it that “the rules of the game” are fair. Once society has been organized around a set of fair rules, people can set about freely “playing” the game, without interference.

b. Utilitarianism as the Principal Opponent

Rawls explains in the Preface to the first edition of TJ that one of the book’s main aims is to provide a “workable and systematic moral conception to oppose” utilitarianism. TJ at xvii. Utilitarianism comes in various forms. Classical utilitarianism, the nineteenth century theory of Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill, is the philosophy of “the greatest good of the greatest number.” The more modern version is average utilitarianism, which asks us not to maximize the amount of good or happiness, but rather its average level in society. The utilitarian idea, as Rawls confronts it, is that society is to be arranged so as to maximize (the total or average) aggregate utility or expected well-being. Utilitarianism historically dominated the landscape of moral philosophy, often being “refuted,” but always rising again from the ashes. Rawls’s view was that until a sufficiently complete and systematic alternative is put on the table to compete with utilitarianism, its recurrence will be eternal. In addition to developing that constructive alternative, however, Rawls also offered some highly influential criticisms of utilitarianism. His critique of average utilitarianism will be described below. About classical utilitarianism, he famously complains that it “adopt[s] for society as a whole the principle of choice for one man.” In so doing, he suggests, it fails to “take seriously the distinction between persons.” TJ at 24.

c. The Original Position

Recognizing that social institutions distort our views (by sometimes generating envy, resentment, alienation, or false consciousness) and bias matters in their own favor (by indoctrinating and habituating those who grow up under them), Rawls saw the need for a justificatory device that would give us critical distance from them. The original position (OP) is his “Archimedean Point,” the fulcrum he uses to obtain critical leverage. TJ at 230-32. The OP is a thought experiment that asks: what principles of social justice would be chosen by parties thoroughly knowledgeable about human affairs in general but wholly deprived—by the “veil of ignorance”—of information about the particular person or persons they represent?

i. The Conditions and Purpose of the Original Position

The OP, as Rawls designs it, self-consciously builds on the long social-contract tradition in Western political philosophy. In classic presentations, such as John Locke’s Second Treatise of Civil Government (1690), the social contract was sometimes described as if it were an actual historical event. By contrast, Rawls’s social-contract device, like his earlier decision procedure, is frankly and completely hypothetical. While Rawls is most emphatic about this in his later work, for example, PL at 75, it is clear already in TJ. He insists there that it is up to the theorist to construct the social-contract thought-experiment in the way that makes the most sense given its task of helping us select principles of justice. Especially because of its frankly hypothetical nature, Rawls’s OP “carries to a higher level of abstraction the familiar theory of the social contract as found, say in Locke, Rousseau, and Kant.” TJ at 10.

The idea is to help justify a set of principles of social justice by showing that they would be selected in the OP. The OP is accordingly set up to build in the moral conditions deemed necessary for the resulting choice to be fair and to insulate the results from the influence of the extant social order. The veil of ignorance plays a crucial role in this set-up. TJ at sec. 23. It assures that each party to the choice is equally or symmetrically situated, with none enjoying greater power (or “threat advantage”) than any other. TJ at 116, 121. It also isolates the parties’ choice from the contingencies—the sheer luck—underlying the variations in people’s natural abilities and talents, their social backgrounds, and their particular society’s historical circumstances. About their society, Rawls has the parties simply assume that it is characterized by the “circumstances of justice,” which principally include (a) the fact that material goods are scarce, but moderately so and (b) that there is, within society, a plurality of worldviews—“conceptions of the good” —moral, religious, and secular. TJ at sec. 22.

It would be too fanciful to think of the parties to the OP as having the capacity to invent principles. The point of the thought experiment, rather, is to see which principles would be chosen in a fair set-up. To use the OP this way, we must offer the parties a menu of principles to choose from. Rawls offers them various principles to consider. Among them are his own principles (to be described below) and the two versions of utilitarianism, classical and average. The crux of Rawls’s appeal to the OP is whether he can show that the parties will prefer his principles to average utilitarianism.

Would rational parties behind a veil of ignorance choose average utilitarianism? The economist John Harsanyi argues that they would because it would be rational for parties lacking any other information to maximize their expectation of well-being. Harsanyi (1953) Since they do not know who they will be, they will therefore want to maximize the average level of well-being in society. Given Rawls’s opposition to utilitarianism, it would be ironic if Rawls’s thought experiment supported it. Because Rawls’s OP differs from Harsanyi’s choice situation in important ways, however, its parties will not prefer average utilitarianism to Rawls’s competing principles. The most crucial difference concerns the motivation that is attributed to the parties by stipulation. The veil deprives the parties of any knowledge of the values—the conception of the good—of the person into whose shoes they are to imagine stepping. What, then, are they to prefer? Since Harsanyi refuses to supply his parties with any definite motivation, his answer is somewhat mysterious. Cf. TJ at 152. Rawls instead defines the parties as having a determinate set of motivations.

ii. The Motivations of the Parties to the Original Position

The parties in the hypothetical OP are to choose on behalf of persons in society, for whom they are, in effect, trustees. PL at 76, 106. The veil of ignorance, however, prevents the parties from knowing anything particular about the preferences, likes or dislikes, commitments or aversions of those persons. They also know nothing particular about the society for which they are choosing. On what basis, then, can the parties choose? To ascribe to them a full theory of the human good would fly in the face of the facts of pluralism, for such theories are deeply controversial. Instead, Rawls suggests, we should ascribe to them a “thinner” or less controversial set of commitments. At the core of these are what he calls the “primary goods:” rights, liberties, and opportunities; income and wealth; and the social bases of self-respect. To give the parties a definite basis on which to reason, Rawls postulates that the parties “normally prefer more primary goods rather than less.” TJ at 123. This is the only motivation that TJ ascribes to the parties.

In their pursuit of the primary goods, the parties are defined as being “mutually disinterested:” each is motivated to obtain as many primary goods as he or she can and does not care if others attain primary goods. TJ at 12. The parties are motivated neither by benevolence nor by envy or spite. Many commentators think that this assumption of the parties’ mutual disinterest reflects an unattractively individualistic view of human nature, but, as with the motivations ascribed to the parties, the ascription of mutual disinterest is not intended to mirror human nature. The assumption of mutual disinterest reflects Rawls’s development of, and reaction against, both the sympathetic-spectator tradition in ethics, exemplified by David Hume and Adam Smith, and the more recent ideal-observer theory. The former tradition attempts to imagine the point of view of a fully benevolent spectator of the human scene who reacts impartially and sympathetically to all human travails and successes. The ideal-observer theory typically imagines a somewhat more dispassionate or impersonal, but still omniscient, observer of the human scene. Each of these approaches asks us to imagine what such a spectator or observer would morally approve.

Against these theories, Rawls raises a number of objections, which can be boiled down to this: either they involve neglecting the separateness of persons (in roughly the same way that utilitarianism does when it adds up everyone’s happiness), TJ at 164, or, if they seek to avoid utilitarian aggregation, they will find that “benevolence is at sea as long as its many loves are in opposition in the persons of its many objects.” TJ at 166. In other words, all difficult questions of human conflict will be simply reproduced within the sympathetic spectator’s breast. Rawls was determined to get beyond this impasse. He suggests that the OP should combine the mutual-disinterest assumption with the veil of ignorance. This combination, he argues, will achieve the rough moral equivalence of universal benevolence without either neglecting the separateness of persons or sacrificing definiteness of results. TJ at 128.

As we will see, the definite positive motivations that Rawls ascribes to the parties are crucial to explaining why they will prefer his principles to average utilitarianism. Because the parties’ motivations are essential to the arguments bearing on this central philosophical contest, it is important to attend to Rawls’s rationale for giving this motivation to the parties.

The primary goods are supposed to be uncontroversially worth seeking, albeit not for their own sakes. Initially, TJ presented the primary goods simply as goods that “normally have a use whatever a person’s plan of life.” TJ at 54. Although this claim seems quite modest, philosophers rebutted it by describing life plans or worldviews for which one or another of the primary goods is not useful. These counterexamples revealed the need for a different rationale for the primary goods. At roughly the same time, Rawls began to develop further the Kantian strand in his view. These Kantian ideas ended up providing a new rationale for the primary goods.

iii. Kantian Influence and Interpretation of the Original Position

Rawls had long admired Immanuel Kant’s moral philosophy, making it central to his teaching of the subject. See CP essays 13, 16, 23. TJ aims to build on Kant’s central ideas and to improve on them in certain respects. TJ at sec. 41. By insisting, as against utilitarianism, on the “separateness of persons,” Rawls carries on Kant’s theme of respect for persons. Kant held that the true principles of morality are not imposed on us by our psyches or by eternal conceptual relations that hold true independently of us; rather, Kant argued, the moral law is a law that our reason gives to itself. It is, in this sense, self-chosen or autonomous law. Kant’s position is not that morality requires whatever Ms. Smith or Mr. Jones chooses to believe it does. Rather, his claim is that the rational (or vernünftig) nature that each person shares shapes a single moral law, valid for all: “the categorical imperative.”

Rawls suggests that the OP well models Kant’s central ideas. The OP is set up so that the parties reflect our nature as “reasonable and rational”—Rawls’s dual way of rendering the Kantian adjective vernünftig. Once it is so set up the parties are to choose principles. Their task of choosing principles thus models the idea of autonomy. In designing the OP, Rawls also aimed to resolve what he took to be two crucial difficulties with Kant’s moral theory: the danger of empty abstractness early stressed by Hegel and the difficulty of assuring that the moral law’s dictates adequately express, as Kant thought they must, our nature as free and equal reasonable and rational beings. Rawls addresses the issue of abstractness in many ways—perhaps most fundamentally by dropping Kant’s aim of finding an a priori basis for morality. Although Rawls’s use of the veil of ignorance keeps particular facts at a distance, he insists, as against Kant, that “moral theory must be free to use contingent assumptions and general facts as it pleases.” TJ at 44. Another feature that reduces the abstractness of Rawls’s view is his focus on institutions—on the basic structure of society. In this light, we can see his institutional focus as carrying forward Hegel’s insight that the idea of human freedom can achieve an adequately concrete realization only by a unified social structure of a certain kind.

The OP also addresses the second problem with Kant’s moral theory—the problem of expression. The OP, Rawls suggests, “may be viewed … as a procedural interpretation of Kant’s conception of autonomy and the categorical imperative within the framework of an empirical theory.” TJ at 226. To be autonomous, for Kant, is to act on a law that one gives oneself, a law adequate to one’s nature as a free and equal, reasonable and rational person. The parties to the OP, in selecting principles, implement this idea of autonomy. How they represent equality and rationality are obvious, for they are equally situated and are rational by definition. Reasonableness enters the OP not principally by the rationality of the parties but by the constraints on them—most especially the veil of ignorance. They are also constrained in ways not yet mentioned and that we shall not discuss further, such as “the formal constraints of the concept of right.” TJ at sec. 23. The veil also expresses (or “models”) a crucial aspect of our freedom, namely our freedom to endorse principles in a way that is not controlled by the historical contingencies of the society into which we are born. TJ at 225.

Rawls’s attempt to solve the problem of expression also led him towards a fuller articulation of the parties’ motivations, ascribing to them certain “highest-order interests.” An intermediate step in this direction is his characterization of our three highest-order powers, the “moral powers” that persons have as reasonable and rational beings. “The rational” corresponds to Kant’s “hypothetical imperative” with its directive to take effective means to one’s ends; “the reasonable” corresponds to Kant’s categorical imperative, the moral law that demands that we do the right thing, irrespective of what our ends are. To conceive of persons as reasonable and rational, then, is to conceive of them as having certain higher-order powers. On the side of the rational, there is, first, the power to frame our ends—our “conception of the good”—and to pursue it by selecting effective means to satisfying them. Second, we can also revise our ends when we see reason to do so. Third, on the side of the reasonable, we have the power or capacity to act from “an effective sense of justice:” we can do the right thing.

This Kantian conception of the powers of reasonable and rational persons directly supports Rawls’s later account of the motivations of the parties. The parties are conceived as having highest-order interests that correspond directly to these highest-order powers. Although the account of the moral powers was present in TJ, it is only in his later works that Rawls uses this idea to defend and elaborate the motivation of the parties in the OP.

Rawls’s account of the moral powers explains why it makes sense to postulate that the parties are motivated to secure the primary goods. In various, complicated ways, in his later work, Rawls defends the primary goods as being required for free and equal citizens to promote and protect their three moral powers. This is to cast the primary goods as items objectively needed by moral persons occupying the role of free and equal citizens. While the list of primary goods may not be a perfect or complete account of what is needed to support this aspect of moral personality, Rawls claims that it is the “best available” account that we can muster in the face of the fact of reasonable pluralism. PL at 188-9.

In addition to providing a new rationale for the primary goods, Rawls’s account of the moral powers also became, in his later work, a basis for elaborating the motivations ascribed to the parties. In Political Liberalism, Rawls describes the motivation as: “The parties in the original position have no direct interests except an interest in the person each of them represents and they assess principles of justice in terms of primary goods. In addition, they are concerned with securing for the person they represent the higher-order interests we have in developing and exercising our … moral powers and in securing the conditions under which we can further our determinate conceptions of the good, whatever it is.” PL at 105-6. Here, the motivation of the parties is importantly extended by postulating that these hypothetical beings care about the moral powers of persons in society and also, by extension, about those persons’ ability to pursue what they particularly care about or are committed to.

Rawls’s assumptions about the motivations of the parties involve frankly moral content and are justified on openly moral grounds, as he had always avowed. His aim remains, nonetheless, to assemble in the OP a series of relatively uncontroversial, relatively fixed points among our considered moral judgments and to build an argument on that basis for the superiority of some principles of justice over others.

d. The Principles of Justice as Fairness

“Justice as Fairness” is Rawls’s name for the set of principles he defends in TJ. He refers to “the two principles of Justice as Fairness,” but the second has two parts. These principles address two different aspects of the basic structure of society: the “First Principle” addresses the essentials of the constitutional structure. It holds that society must assure each citizen “an equal claim to a fully adequate scheme of equal basic rights and liberties, which scheme is compatible with the same scheme for all.” PL at 5. The second principle addresses instead those aspects of the basic structure that shape the distribution of opportunities, offices, income, wealth, and in general social advantages. The first part of the second principle holds that the social structures that shape this distribution must satisfy the requirements of “fair equality of opportunity.” The second part of the second principle is the famous—or infamous—“Difference Principle.” It holds that ”social and economic inequalities … are to be to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged members of society.” PL at 6. Each of these three centrally addresses a different set of primary goods: the First Principle concerns rights and liberties; the principle of Fair Equality of Opportunity concerns opportunities; and the Difference Principle primarily concerns income and wealth. (That the view adequately secures the social basis of self-respect is something that Rawls argues more holistically). TJ at 477-8.

e. The Argument from the Original Position

The argument that the parties in the OP will prefer Justice as Fairness to utilitarianism and to the various other alternative principles with which they are presented divides into two parts. There is, first, the question whether the parties will insist upon securing a scheme of equal basic liberties and upon giving them top priority. Secondly, assuming that they will, there remains the question whether social inequalities should be governed by Rawls’s “second principle,” comprising Fair Equality of Opportunity and the Difference Principle, or else should be addressed in a utilitarian way. Making the latter choice, and so inserting utilitarianism into a position subordinate to the First Principle, yields what Rawls calls a “mixed conception.” TJ at 107.

Each of these parts of the argument from the OP is considerably aided by the clarified account of the primary goods that emerges in Rawls’s later work and that has been set out above in the section on the motivation of the parties to the OP. Regarding the first part of the argument from the OP, the crucial point is that the parties are stipulated to care about rights and liberties. They further know, as a general fact about human beings, that the determinate persons on whose behalf they are choosing are likely to have firmly and deeply-held “religious, philosophical, and moral views.” PL at 311 They also have a higher-order interest in protecting these persons’ abilities to advance these conceptions. Accordingly, “they cannot take chances by permitting a lesser liberty of conscience to minority religions, say, on the possibility that those they represent espouse a majority or dominant religion.” PL at 311. Rawls admits that persons’ deeply-held views are not always set in stone, but he insists that not all circumstances in which they may change are morally acceptable. He argues that protecting one’s ability to exercise one’s highest-order power to change one’s mind about such things requires an adequate scheme of basic liberties. PL at 312-3. In addition, he argues that securing the First Principle importantly serves the higher-order interest in an effective sense of justice—and does so better than the pure utilitarian alternative—by better promoting social stability, mutual respect, and social unity. PL at 317-24.

The second part of the argument from the OP takes the First Principle for granted and addresses the matter of social inequalities. Its sticking point has always been the Difference Principle, which strikingly and influentially articulates a liberal-egalitarian socioeconomic position. While there are questions about Rawls’s precise formulation and implementation of the principle of Fair Equality of Opportunity, it is far less controversial, both in theory and in practice. It is the Difference Principle that would most clearly demand deep reforms in existing societies. The set-up of the OP suggests the following, informal argument for the difference principle: because equality is an ideal fundamentally relevant to the idea of fair cooperation, the OP situates the parties symmetrically and deprives them of information that could distinguish them or allow one to gain bargaining advantage over another. Given this set-up, the parties will consider the situation of equal distribution a reasonable starting point in their deliberations. Since they know all the general facts about human societies, however, the parties will realize that society might depart from this starting point by instituting a system of social rules that differentially reward the especially productive and could achieve results that are better for everyone than are the results under rules guaranteeing full equality. This is the kind of inequality that the Difference Principle allows and requires: departures from full equality that make some better off and no one worse off.

While this is the intuitive idea behind the Difference Principle, Rawls’s statement of the principle is more careful and precise. Three main refinements are worth noting. First, because the principle pertains to the basic structure of society and because the parties are comparing different societies organized around different principles, the expectations that matter are not those of particular people but those of representative members of broad social classes. Second, to make his exposition a little simpler, Rawls makes some technical assumptions that let him focus only on the expectations of the least-well-off representative class in a given society. (These assumptions—of “close-knitness” and “chain-connection”—enable him to ignore, for instance, the possibility of increasing the inequality between the rich and the middle-class without affecting those on the bottom. For those who find these simplifying assumptions too restrictive, Rawls offers a multi-tiered, or “lexical,” version of the Difference Principle. TJ at 72. Allowed by these simplifying assumptions to focus only on the least well off representative persons, the Difference Principle thus holds that social rules allowing for inequalities in income and wealth are acceptable just in case those who are least well off under those rules are better off than the least-well-off representative persons under any alternative sets of social rules. This formulation already takes account of the third refinement, which recognizes that the people who are the worst off under one set of social arrangements may not be the same people as those who are worst off under some other set of social arrangements. Cf. PL at 7n.

The Difference Principle requires society to look out for the least well off. But would the parties to the OP prefer the Difference Principle to a utilitarian principle of distribution? Here, Rawls’s interpretation of the OP matters. It took a while for commentators to grasp the degree to which Rawls’s characterization of the OP departed from the much simpler one favored by Harsanyi, from the point of view of which Rawls’s argument for the Difference Principle appeared to be a plain mistake. For parties like Harsanyi’s, it would be irrational to choose the Difference Principle. Harsanyi’s parties lack any determinate motivation: as Rawls puts it, they are “bare-persons.” TJ at 152. With nothing but the bare idea of rationality to guide them, they will naturally choose any principle that will maximize their utility expectation. Since this is what the principle of Average Utilitarianism does, they will choose it. Yet as we have seen, Rawls departs from Harsanyi’s version of the thought experiment by attributing a determinate motivation to the parties, while denying that an index of the primary goods provides an interpretation of what the parties conceive to be good. Rawls never defends the primary goods as goods in themselves. Rather, he defends them as versatile means. In the later theory, the primary goods are defended as facilitating the pursuit and revision, by the persons the parties represent, of their conceptions of the good. While the parties do not know what those conceptions of the good are, they do care about whether the persons they represent can pursue and revise them.

With this departure from Harsanyi in mind, we may finally explain why the parties in the OP will prefer the principles of Justice as Fairness, including the Difference Principle, to average utilitarianism. In laying out the reasoning that favors the Difference Principle, Rawls argues that the parties will have reason to use the “maximin” rule. The maximin rule is a general rule for making choices under conditions of uncertainty. It is markedly different from the rule of maximizing expected value, the more “averaging” sort of rule that Harsanyi’s parties employ. The maximin rule directs one to select that alternative where the minimum place is higher (on whatever the relevant measure is) than the minimum place in any other alternative. Applied to the theory of social justice, maximin is an approach “a person would choose for the design of a society in which his enemy is to assign him his place.” TJ at 133.

The parties to Rawls’s OP are not “bare-persons” but “determinate-persons.” TJ at 152. They care about the primary goods and the highest-order moral powers, but they also know, in effect, that the primary goods that they are motivated to seek are not what the persons they represent ultimately care about. Accordingly, the parties will give special importance to protecting the persons they represent against social allocations of primary goods that might frustrate those persons’ ability to pursue their determinate conceptions of the good. If the parties knew they had in hand an adequate sketch of the good, they might use that to assess the gamble they face, choosing in a maximizing way like Harsanyi’s parties. But Rawls’s parties instead know that the primary goods that they are motivated to seek do not adequately match anyone’s conception of the good. Accordingly, it is rational for them to take a cautious approach. They must do what they can to assure to the persons they represent have a sufficient supply of primary goods for those persons to be able to pursue whatever it is that they do take to be good.

f. Reflective Equilibrium

Although the OP attempts to collect and express a set of crucial constraints that are appropriate to impose on the choice of principles of justice, Rawls recognized from the beginning that we could never just hand over the endorsement of those principles to this hypothetical device. Rather, he foresaw the need to “work from both ends,” pruning and adjusting things as we go. TJ at 18. That is, we need to stop and consider whether, on reflection, we can endorse the results of the OP. If those results clash with some of our more concrete considered judgments about justice, then we have reason to think about modifying the OP.

Alternatively—and this is what Rawls means by working “from both ends”—instead of modifying the OP, we might decide that the argument from the OP gives us good reason to modify the considered judgments of justice with which its conclusions clash. Eventually, we may hope that this process reaches a “reflective equilibrium.” If it does, Rawls wrote, “we shall find a description of the initial situation that matches our considered judgments duly pruned and adjusted.” Ibid.

The reflective equilibrium has been an immensely influential idea about moral justification. It is not a full theory of justification. When it was introduced, however, it suggested a different approach to justifying moral theories than was being commonly pursued. The idea of reflective equilibrium takes two steps away from the sort of conceptual analysis that was then prevalent. First, working on the basis of considered judgments suggests that it is not necessary to build moral theories on necessary or a priori premises. What matters, rather, is whether the premises are ones that “we do, in fact, accept.” TJ at 19. Rawls characterizes considered judgments as simply judgments reached under conditions where our sense of justice is likely to operate without distortion. TJ at 42. Second, the sort of pruning and adjusting that Rawls assumes will be involved in the search for reflective equilibrium implies that theories need not aim for a perfect fit with theory-independent “data.” Whereas the practitioners of conceptual analysis had raised to a fine art the method of generating counterexamples to a general theory, Rawls writes that “objections by way of counterexample are to be made with care.” TJ at 45. Checking a theory’s fit with one’s more concrete considered judgments is only a way-station on the route to reflective equilibrium. Reaching it might involve revising some of those more concrete judgments. A third novel idea about justification thus emerges from this picture: it involves arguments built in various different directions at once. The resulting justification, as Rawls puts it, “is a matter of the mutual support of many considerations.” TJ at 19, 507.

Eventually, the hope is that each person will reach a reflective equilibrium that coincides with every other person’s. Since it is up to each person, however, to determine which arguments are most compelling, Rawls stresses that the reader must make up his or her own mind, rather than trying to predict or anticipate what everyone else will think. TJ at 44.

g. Just Institutions

Part Two of TJ aims to show that Justice as Fairness fits our considered judgments on a whole range of more concrete topics in moral and political philosophy, such as the idea of the rule of law, the problem of justice between generations, and the justification of civil disobedience. Consistent with the idea of reflective equilibrium, Rawls suggests pruning and adjusting those judgments in a number of places. One of the thorniest such issues, that of tolerating the intolerant, recurs in PL. In addition to serving its main purpose of facilitating reflective equilibrium on Justice as Fairness, Part Two also offers a treasure trove of influential and insightful discussion of these and other topics in political philosophy. There is hardly space here even to summarize all the worthwhile points that Rawls makes about these topics. A summary of his controversial and influential discussion of the idea of desert (that is, getting what one deserves), however, will illustrate how he proceeds.

As we have seen, Rawls was deeply aware of the moral arbitrariness of fortune. He held that no one deserves the social position into which he or she is born or the physical characteristics with which he or she is endowed from birth. He also held that no one deserves the character traits he or she is born with, such as his or her capacity for hard work. As he wrote, “The natural distribution is neither just nor unjust; nor is it unjust that persons are born into society at some particular position. These are simply natural facts. What is just and unjust is the way that institutions deal with these facts.” TJ at 87.

In Part Two, Rawls sets out to square this stance on the moral arbitrariness of fortune with our considered judgments about desert, which do hold that desert is relevant to distributive claims. For instance, we tend to think that people who work harder deserve to be rewarded for their effort. We may also think that the talented deserve to be rewarded for the use of their talents, whether or not they deserved those talents in the first place. With these common-sense precepts of justice, Rawls does not disagree; but he clarifies them by responding to them dialectically. TJ at sec. 48. He questions whether these common-sense claims are meant to stand independently of any assumptions about whether or not the basic institutions of society—especially those institutions of property law, contract law, and taxation that, in effect, define the property claims and transfer rules that make up the marketplace—are just. It is unreasonable, Rawls argues, to say that desert is a direct basis for distributional claims even if the socio-economic system is unfair. It is much more reasonable to hold, he suggests, that whether one deserves the compensation one can command in the job marketplace, for instance, depends on whether the basic social institutions are fair. Are they set up so as to assure, among other things, an appropriate relationship between effort and reward? It is this justice of the basic structure that is Rawls’s topic.

Rawls’s alternative proposal is that the common-sense precepts about desert generally presuppose that the basic structure of society is itself fair. When they are qualified in line with this presupposition, Rawls supports them. To prevent the unqualified and the qualified claims from being confused with each other, however, he uses the term “legitimate expectations” as a term of art to express the claims of desert appropriately so qualified. A crucial idea of Justice as Fairness is that fundamental principles of justice must be respected for the rules of social cooperation to be fair, and that when they are, we should allow the free operation of the market largely to determine people’s legitimate expectations. (This dialectical clarification of the moral import of desert, however, did not satisfy all commentators. See Robert Nozick (1974).

h. Stability

In pursuing his novel topic of the justice of the basic structure of society, Rawls posed novel questions. One set of questions concerned what he calls the “stability” of those societies whose institutions live up to the requirements of a given set of principles of justice. The stability of the institutions called for by a given set of principles of justice—their ability to endure over time and to re-establish themselves after temporary disturbances—is a quality those principles must have if they are to serve their purposes.. TJ at 398-400. Unstable institutions would not secure the liberties, rights, and opportunities that the parties care about. If any set of institutions realizing a given set of principles were inherently unstable, that would suggest a need to revise those principles. Accordingly, Rawls argues, in Part Three of TJ, that institutions embodying Justice as Fairness would be stable – even more stable than institutions embodying the utilitarian principle.

In addressing the question of stability, Rawls never leaves behind the perspective of moral justification. Stability of a kind might be achieved by arranging a stand-off of opposing but equal armies. The results of such a balance of power are not of interest to Rawls. Rather, the stability question he asks concerns whether, in a society that conforms to the principles, citizens can wholeheartedly accept those principles. Wholeheartedness will require, for instance, that the reasons on the basis of which the citizens accept the principles are reasons affirmed by those very principles. PL at xlii. If stability can be grounded on such wholeheartedly moral reasons—as opposed to ulterior reasons—then it is “stability for the right reasons.” PL at xxxix. In TJ, the account of stability for the right reasons involved imagining that this wholeheartedness arose from individuals being thoroughly educated, along Kantian lines, to think of fairness in terms of the principles of Justice as Fairness. Cf. PL at lxii. As we will see, he later came to think that this account violated the assumption of pluralism.

The imaginative exercise of assessing the comparative stability of different principles would be useless and unfair if one were to compare, say, an enlightened and ideally-run set of institutions embodying Justice as Fairness with the stupidest possible set of institutions compatible with the utilitarian principle. In order to standardize the terms of comparison, Rawls discusses only the “well-ordered societies” corresponding to each of the rival sets of principles. His notion of a well-ordered society is complex. See CP at 232-5. The gist of it is that the relevant principles of justice are publicly accepted by everyone and that the basic social institutions are publicly known (or believed with good reason) to satisfy those principles.

Assessing the comparative stability of alternative well-ordered societies requires a complex imaginative effort at tracing likely phenomena of social psychology. As Rawls comments, “One conception of justice is more stable than another if the sense of justice that it tends to generate is stronger and more likely to override disruptive inclinations and if the institutions it allows foster weaker impulses and temptations to act justly.” CP at 398. In order to address the first of these issues, about the strength of the sense of justice, Chapter VIII develops a rich and somewhat original account of moral education. Drawing upon empirical research in developmental psychology, Rawls describes the gradual development of individuals’ senses of justice as involving three stages: the morality of authority, which is fostered in families; the morality of association; and the morality of principles. He argues that each of these stages of moral education will work more effectively under Justice as Fairness than it will under utilitarianism. TJ at chap. 8. He also argues that a society organized around the two principles of Justice as Fairness will be less prone to the disruptive effects of envy than will a utilitarian society. TJ at secs. 80-81.

i. Congruence

As we have seen, the veil of ignorance disconnects the argument from the OP from any given individual’s full conception of the good. The final question addressed by TJ attempts to reconnect justice to each individual’s good, not in general, but within the well-ordered society of Justice as Fairness. A stable society is one that generates attitudes, such as are encapsulated in an effective sense of justice, that support the just institutions of that society. If, in the well-ordered society, having those attitudes is also a good for the persons who have them, then there is a “match between justice and goodness” that Rawls calls “congruence.” TJ at 350.

In order to address this question of congruence, TJ develops an account of the good for individuals. Chapter VII of TJ, in fact, develops a quite general theory of goodness—called “goodness as rationality”—and then applies it to the special case of the good of an individual over a complete life. Rawls starts from the suggestion that “A is a good X if and only if A has the properties (to a higher degree than the average or standard X) which it is rational to want in an X, given what X’s are used for, or expected to do, and the like (whichever rider is appropriate).” TJ at 350-1. This idea, developed in dialogue with the leading alternatives from the middle of the 20th century, still repays attention. To work out this suggestion for the case of the good for persons, Rawls influentially developed and deployed the notion of a “life plan.” A rational plan of life for an individual, he argued, is answerable to certain principles of “deliberative rationality.” These Rawls sets out in a low-key way that masks the power and originality of his formulations. TJ at 359-72.

Rawls’s argument for congruence—that having an effective sense of justice built around the principles of Justice as Fairness will be a good for each individual—is a complex and philosophically deep one. It appeals to at least four types of intermediate good, each of which may be presumed to be of value to just about everyone: (i) the development and exercise of complex talents (which Rawls’s “Aristotelian Principle” presumes to be a good for human beings), TJ at 374, (ii) autonomy, (iii) community, and (iv) the unity of the self. Rawls’s argument for congruence is spread out across many sections of TJ. Some of its main threads are pulled together by Samuel Freeman in his contribution to The Cambridge Companion to Rawls. Freeman (2003). With regard to autonomy, to supplement the positive argument flowing from the Kantian interpretation of the OP, Rawls argues that the type of objectivity claimed for the principles of Justice as Fairness is not at odds with the idea of the autonomous establishment of principles. TJ at sec. 78. He further argues that Justice as Fairness supports the kind of tightly-knit community he calls “a social union of social unions,” marked by the shared purpose or “common aim of cooperating together to realize their own and another’s nature in ways allowed by the principles of justice.” TJ at 462. If Rawls is right about the congruence of goodness and justice, these “ways” are hardly trivial. (Not long after TJ was published, it came under attack by a set of critics who identified themselves as “communitarians,” see for example MacIntyre (1984) and Sandel (1998). Ironically, the communitarian critique focused largely on Parts One and Two of TJ, giving short shrift to the powerful articulation of this ideal of community in Part Three.) Finally, regarding the unity of the self, Rawls criticizes the Procrustean sort of unity that could come from attaching oneself to a single “dominant end.” He notes the advantages of a conception of the unity of the self that hangs, instead, on the regulative status of principles of justice. TJ at secs. 83-85. The cumulative effect of these appeals to the development of talent, autonomy, community, and the unity of the self is to support the claim of Justice as Fairness to congruence. In a well-ordered society corresponding to Justice as Fairness, Rawls concludes, an effective sense of justice is a good for the individual who has it. In TJ, this congruence between justice and goodness is the main basis for concluding that individual citizens will wholeheartedly accept the principles of justice as fairness.

3. Recasting the Argument for Stability: Political Liberalism (1993)

Rawls has the parties to the OP assume that the society for which they are choosing principles is in the “circumstances of justice,” which include the presence of a plurality of irreconcilable moral, religious, and philosophical doctrines. But his argument for the comparative stability and the congruence of Justice as Fairness, imagines a well-ordered society in which everyone is brought up in ways deeply informed by the adherence by all adults to the same principles of justice. Accordingly, his discussion of stability and congruence in Part Three of TJ is at odds with the assumption of pluralism. In his second book, Political Liberalism [PL], he set out to rectify this “serious problem.” PL at xvii.

PL clarifies that the only acceptable way to rectify the problem is to modify the account of stability and congruence, because pluralism is no mere theoretical posit. Rather, pluralism has been endemic among the liberal democracies since the 16th century wars of religion. Moreover, pluralism is a permanent feature of liberal or non-repressive societies. It does not rest on irrationality. On the contrary, within a wide range such pluralism is “reasonable” and will not be erased by people’s attempts to cooperate reasonably. That is because a series of intractable “burdens of judgment” all but preclude reasoned convergence on fundamental and comprehensive principles about how to live. PL at 54-8. Accordingly, Rawls takes it as a fact that the kind of uniformity in fundamental moral and political beliefs that he imagined in Part Three of TJ can be maintained only by the oppressive use of state force. He calls this “the fact of oppression.” PL at 37. Since he also—unsurprisingly—holds that oppression is illegitimate, he refrains from offering fundamental and comprehensive principles of how to live. In this way, his insistence on the fact of oppression prompts a marked scaling back of the traditional aims of political philosophy.

The seminal idea of PL is “overlapping consensus.” In an overlapping consensus, each citizen—no matter which of society’s many “comprehensive conceptions” he or she endorses—ends up endorsing the same limited, “political conception” of justice, each for his or her own reasons. The principal role of the overlapping consensus is to replace TJ’s description of wholehearted acceptance. Unlike TJ’s description, the overlapping consensus conceptually reconciles wholehearted acceptance with the fact of reasonable pluralism.

Part of this newer approach is the distinction between “comprehensive conceptions,” which address all questions about how to live, and “political conceptions,” which address only political questions. This distinction has proven somewhat troublesome. The “domain of the political,” as Rawls calls it, is not completely distinct from morality. In concerning himself only with the political, he is not setting aside all moral principles and turning instead to mere strategy or Realpolitik. On the contrary, a political conception “is, of course, a moral conception,” but it is a moral conception that concerns itself only with the basic structure of society. PL at 11. Further, a political conception is one that may be developed in a “freestanding” way, drawing only upon the “very great values” of the political, rather than being presented as deriving from any more comprehensive moral or religious doctrine. PL at 139. A corollary of this approach is that such a political liberalism is not wholly neutral about the good. PL at 191-3. While Justice as Fairness is one such political conception, in PL Rawls makes a point of stressing that it is just one member of the broader family of views he refers to as the “reasonable liberal political conceptions.”

Armed with the idea of an overlapping consensus on a reasonable political conception, Rawls could have contented himself with describing the historical and sociological grounds for hoping that a reasonable overlapping consensus on a political liberalism might be reached. Hope is indeed the leitmotif of PL. E.g PL at,40, 65, 172, 246, 252, 392. But because Rawls never drops his role as an advocate of political liberalism, he must go beyond such disinterested sociological speculation. He must find and describe ways of advocating this view that are compatible with his full, late recognition of the fact of reasonable pluralism. This attempt is what makes PL so rich, difficult, and interesting.

The difficulty is this: to advocate Justice as Fairness or any other political liberalism as true would be to clash with many comprehensive religious and moral doctrines, including those that simply deny that truth or falsity apply to claims of political morality, as well as those that insist that political-moral truths derive only from some divine revelation. To preserve the possibility of an overlapping consensus on political liberalism, it might be thought that its defenders must deny that political liberalism is simply true, severely hampering their ability to defend it. To cope with this difficulty, Rawls pioneered a stance in political philosophy that mirrored his general personal modesty: a stance of avoidance. Using the “method of avoidance,” Rawls neither asserts nor denies such truth claims. CP at 395. “The central idea,” he writes, “is that political liberalism moves within the category of the political and leaves philosophy as it is.” PL at 375. Perhaps defending political liberalism as the most reasonable political conception is to defend it as true; but, again, Rawls neither asserts nor denies that this is so.

Developing a compelling freestanding presentation of political morality may be possible if we may draw upon a shared set of relevant moral ideas implicit in the “background culture” of democratic societies. PL at 14. Foremost among such shared ideas is the idea of fair cooperation among free and equal citizens. Much of PL is accordingly devoted to recasting the earlier argument for Justice as Fairness in terms that are “political, not metaphysical.” Many of the revisions concern the arguments for various features of the OP. Although these revisions occupy much of PL, they need not be covered further here, as most of them have been already anticipated in the above exposition of TJ. To have structured the exposition in this way is to have sided with those who see considerable unity in Rawls’s work, for example, Wenar (2004). One important change, however, is that PL goes to considerably further lengths to show that the values to which the view appeals are political, rather than being tied up in any particular comprehensive doctrine. For instance, that citizens are thought of as free is defended, not by general metaphysical truths about human nature, but rather by our widely shared political convictions. “On the road to Damascus Saul of Tarsus becomes Paul the Apostle. Yet such a conversion implies no change in our public or institutional identity.” PL at 31. On the contrary, our political rights ought not to vary with such changes. To think of political rights in this way is to think of citizens as free, in a relevant, political sense.

Instead of seeing a fundamental unity to Rawls’s work, some commentators emphasize what they take to be PL’s new focus on political legitimacy, as distinct from political justice, for example, Estlund (1998) and Dreben (2003). It is certainly true that Rawls prominently deploys a “liberal principle of legitimacy” that was not present in TJ. This principle states that

[O]ur exercise of political power is proper and hence justifiable only when it is exercised in accordance with a constitution the essentials of which all citizens may reasonably be expected to endorse in the light of principles and ideals acceptable to them as reasonable and rational. PL at 217; cf. 137.

This principle thus appears to connect Rawls’s view to that of others working in political and democratic theory who lean on the notion of “reasons that all can accept,” for example, Gutmann and Thompson (1996). Rawls, however, leans more heavily than most on the notion of reasonableness. This is apparent in a late essay, where he writes that “our exercise of political power is proper only when we … reasonably think that other citizens might also reasonably accept those reasons [on which it is based].” CP at 579.

These further qualifications hint at the relatively limited purpose for which Rawls appeals, within PL, to this principle of legitimacy. The principle is part of his account of “public reason” in pluralist societies. This account answers the question: how can we, in political society, reason with one another so as to set priorities and make political decisions, given the fact of reasonable pluralism and the burdens of judgment that make it permanent? Finding reasons that we reasonably think others might accept is a crucial part of the answer. The demand that we do so makes up the core of the duty of civility that binds citizens acting in any official capacity. Rawls’s limits on public reasoning have been highly controversial, but it is important to remember that they form part of his revised thought experiment about stability. The overall question of PL is similar to that of Part Three of TJ: what grounds do we have for thinking that a political liberalism would be stable? In this context, Rawls’s duty of civility may be seen as contributing his defense of the following conditional claim: if citizens of a pluralist society would abide by such restraints of civility, and if a political liberalism were the object of an overlapping consensus, then that political liberalism would be stable.

To this observation, some of the critics of Rawls’s account of public reason reply that accepting this kind of restraint on public dialogue would be too high a price to pay for a stable liberalism. See Richardson & Weithman vol. 5 (1999). Yet in his last essay on the subject, “The Idea of Public Reason Revisited” (in LP as well as CP), Rawls introduced qualifications to his duty of civility that have mollified some. To begin with, he emphasizes that this stricture is not meant to restrict public discussion in the “background culture” in any way, but only to constrain certain official interactions. He further introduces a “proviso” that allows one to rely, even in official contexts, on reasons dependent on one or another comprehensive doctrine, so long as “in due course” one provides “properly public reasons.” CP at 584. Even this revised account of civility remains highly debatable. Still, it should make a difference to the debate whether we consider the restriction only as part of a hypothetical consideration of the stability of a given well-ordered society (specifically, one that has reached overlapping consensus on some political liberalism) or rather as a doctrine about what civility requires in our society, here and now.

4. Problems of Extension

The modesty and restraint we have noted in Rawls’s general approach is also revealed in the way he set aside a number of difficult questions that properly arise within his self-assigned topic. Complicated as his view is, he was keenly aware of the many simplifying assumptions made by his argument. “We need to be tolerant of simplifications.” TJ at 45-6. His most prominent simplifications are the following two: the assumption (“for the time being”) that society is “a closed system isolated from other societies,” TJ at 7, and that “all citizens are fully cooperating members of a society over a complete life.” CP at 332; cf. PL at 20. These simplifications set aside questions about international justice and about justice for the disabled. An additional simplifying assumption implicit in the account of moral development in Part Three of TJ, is that families are just and caring. Relaxing each of these three simplifying assumptions gives rise to important and challenging “problems of extension” for a Rawlsian view.

In The Law of Peoples [LP] (1999), Rawls relaxes the assumption that society is a closed system that coincides with a nation-state. Once this assumption is dropped, the question that comes to the fore is: upon what principles should the foreign policy of a decent liberal regime be founded? Rawls first looks at this question from the point of view of ideal theory, which supposes that all peoples enjoy a decent liberal-democratic regime. At this level, with reference to a rather thinly-described global original position, Rawls develops basic principles concerning non-intervention, respect for human rights, and assistance for countries lacking the conditions necessary for a decent or just regime to arise. These principles govern one nation in its relations with others. He next discusses the principles that should govern decent liberal societies in their relations with peoples who are not governed by decent liberalisms. He articulates the idea of a “decent consultation hierarchy” to illustrate the sort of non-liberal society that is owed considerable tolerance by the people of a decent liberal society. In a part of the book devoted to non-ideal theory, Rawls impressively defends quite restrictive positions on the right of war and on the moral conduct of warfare. Surprisingly, questions of global distributive justice are confined to one brief section of LP. In that section, Rawls treats quite dismissively two earlier attempts to extend his theoretical framework to questions of international justice, those of Beitz (1979) and Pogge (1994). Drawing on the ideas of TJ, these philosophers had developed quite demanding principles of international distributive justice. In LP, Rawls instead favors a relatively minimal “duty of assistance,” with a definite “target and a cut-off point.” LP at 119.

As to justice for the disabled, Rawls never attempted an extension of his theory. He did direct some brief remarks to the topic in Political Liberalism, noting that the view generates a salient distinction between those whose disabilities permanently prevent them from being able to express their higher-order moral powers as fully cooperating citizens and those whose do not. PL at 183-6. While Rawls limited himself to this observation, Norman Daniels’ work on justice and health care may be viewed as an attempt to extend Rawls’s view in the direction the observation indicates. Daniels (1985). Nussbaum argues that Rawlsian social-contract theory is a deeply flawed basis for addressing questions of justice for the disabled and cannot be well extended to deal with them. Nussbaum (2005).

Responding to critics, Rawls did briefly address justice within the family in “The Idea of Public Reason Revisited.” CP at 595-601; LP at 156-164. He writes that he had “thought that J. S. Mill’s landmark The Subjection of Women … made clear that a decent liberal conception of justice (including what I have called Justice as Fairness) implied equal justice for women as well as men,” but admits that he “should have been more explicit about this.” CP at 595. He there affirms that “the family is part of the basic structure” and is subject to being regulated by the principles of political justice. The laws defining the rights of marriage, divorce, and the ownership and inheritance of property by families and family members are presumably all part of the basic structure of society, as are provisions of the criminal law protecting the basic rights of family members not to be abused.

In the case of the family as in economic transactions, Rawls’s stance illustrates once more how his focus on institutional justice structures his attempt to reconcile freedom and equality. Egalitarian concerns are addressed at the institutional level by assuring that protection for the appropriate rights and liberties is assured by the basic structure of society. Freedom is preserved by allowing individuals to pursue their reasonable conceptions of the good, whatever they may be, within those constitutional constraints.

5. References and Further Reading

Principal Works by John Rawls:

A Theory of Justice, rev. ed., Harvard University Press, 1999 [cited as TJ].

Political Liberalism, rev. ed., Columbia University Press, 1996 [cited as PL].

Collected Papers, ed. Samuel Freeman, Harvard University Press, 1999 [cited as CP].

The Law of Peoples, Harvard University Press, 1999 [cited as LP].

Lectures on the History of Moral Philosophy, ed. Barbara Herman, Harvard University Press, 2000.

Justice as Fairness: A Restatement, ed. Erin Kelly, Harvard University Press, 2001.

Lectures on the History of Political Philosophy, ed. Samuel Freeman, Harvard University Press, 2007.

Two useful gateways to the voluminous secondary literature on Rawls are the following:

Henry S. Richardson and Paul J. Weithman, eds., The Philosophy of Rawls (5 vols., Garland, 1999).

Samuel Freeman, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Rawls (Cambridge University Press, 2003).

On Rawls’s Life

Thomas Pogge, “A Brief Sketch of Rawls’s Life,” in Richardson & Weithman, eds., Vol. 1, pp. 1-15.

Other Works Cited:

Beitz, Charles. 1979. Political Theory and International Relations. Princeton University Press.

Daniels, Norman. 1985. Just Health Care. Cambridge University Press.

Dreben, Burton. 2003. On Rawls and Political Liberalism. In Freeman, 2003: 316-346.

Estlund, David. 1998. The Insularity of the Reasonable. Ethics 108: 252-75.

Gutmann, Amy and Dennis Thompson. 1996. Democracy and Disagreement. Harvard University Press.

Harsanyi, John C. 1953. Cardinal Utility in Welfare Economics and in the Theory of Risk-Taking. Journal of Political Economy 61: 453-5.

MacIntyre, Alasdair. 1984. After Virtue, 2d ed. (1st ed. 1981) (University of Notre Dame Press).

Nozick, Robert. 1974. Anarchy, State, and Utopia. NY: Basic Books.

Nussbaum, Martha C. 2005. Frontiers of Justice: Disability, Nationality, Species Membership (Harvard University Press).

Okin, Susan. 1989. Justice, Gender, and the Family. NY: Basic Books.

Pogge, Thomas. 1994. An Egalitarian Law of Peoples. Philosophy and Public Affairs 23: 195-224.

Sandel, Michael. 1998. Liberalism and the Limits of Justice, 2d ed. (1st ed. 1982) (Cambridge University Press).

Richardson, Henry S. 2006. Rawlsian Social Contract Theory and the Severely Disabled. Journal of Ethics 10: 419-462.

Urmson, J. O. 1950. On Grading. Mind 59: 526-29.

Wenar, Leif. 2004. The Unity of Rawls’s Work. Journal of Moral Philosophy 1: 265-275.

Author Information

Henry S. Richardson

Email: [email protected]

Georgetown University

U.S.A.