Is a Collaborative Conlang Even Possible?

Author: Gary J. Shannon

MS Date: 07-20-2012

FL Date: 09-01-2012

FL Number: FL-00000C-00

Citation: Shannon, Gary J. 2012. «Is a Collaborative

Conlang Even Possible?» FL-00000C-00, Fiat

Lingua,

September 2012.

Copyright: This work is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0

Unported License.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

Fiat Lingua is produced and maintained by the Language Creation Society (LCS). For more information

about the LCS, visit http://www.conlang.org/

Is a Collaborative Conlang Even Possible?

Gary J. Shannon

The hobby of constructing artificial languages is the admittedly odd pursuit of a

small handful of individuals who, aside from this strange avocation, could probably pass

for normal in the society of their fellow humans. But as satisfying as this activity might

be when done in secret, it seems it should be all the more interesting when shared with

others. In fact, the first constructed languages were meant to be shared with the whole

world. The idea of one universal language for all of mankind goes back to the Biblical

account of the Tower of Babel, but one of the first practical attempts to construct such a

language also became one of the earliest collaborative conlang projects of which we have

any knowledge.

In the mid 1880’s a constructed language called Volapük, the creation of a

German priest, Johann Martin Schleyer, became all the rage in France. Both the

intellectuals and the working class people were caught up in the enthusiasm for “A new

Golden Age of brotherhood, unencumbered by the chains of Babel”[1]. One could

frequently overhear Volapük being spoken in the streets of Paris. In 1888 alone 182

Volapük textbooks were published. By 1889 there were 25 regularly published magazines

in or about Volapük, and at the third International Volapük congress in Paris in May 1889

everyone, down to the waiters in the dining hall, spoke Volapük.

But beneath this appearance of strength and vitality was a foundation that was

falling apart. Factions were coalescing around mutually incompatible goals and intentions

for the language. Some wanted a “rich and perfect” language suitable for the highest of

literary forms, while others favored a simpler more practical Volapük for science and

commerce. The Dutch polymath Auguste Kerckhoffs, as secretary of the French

Association for the Propagation of Volapük, was asked to submit all questions about the

language to the International Academy of Volapük where each issue would be deliberated

and decided upon. Instead, he submitted a complete published grammar, or rather his own

vision of what the grammar of Volapük should be. Meanwhile, Schleyer, as inventor of

the language insisted that his decisions must always be final regardless of the preferences

of the Academy.

Tensions mounted and, in spite of the support and enthusiasm of the hundreds of

thousands of correspondents involved with the language, the whole project collapsed

almost overnight. In 1889 there were approximately 200,000 active Volapük

correspondents and 283 clubs around the world, but by 1891 the number of active clubs

and associations dropped to only four and by 1902 the list of registered correspondents

had fallen to 159.

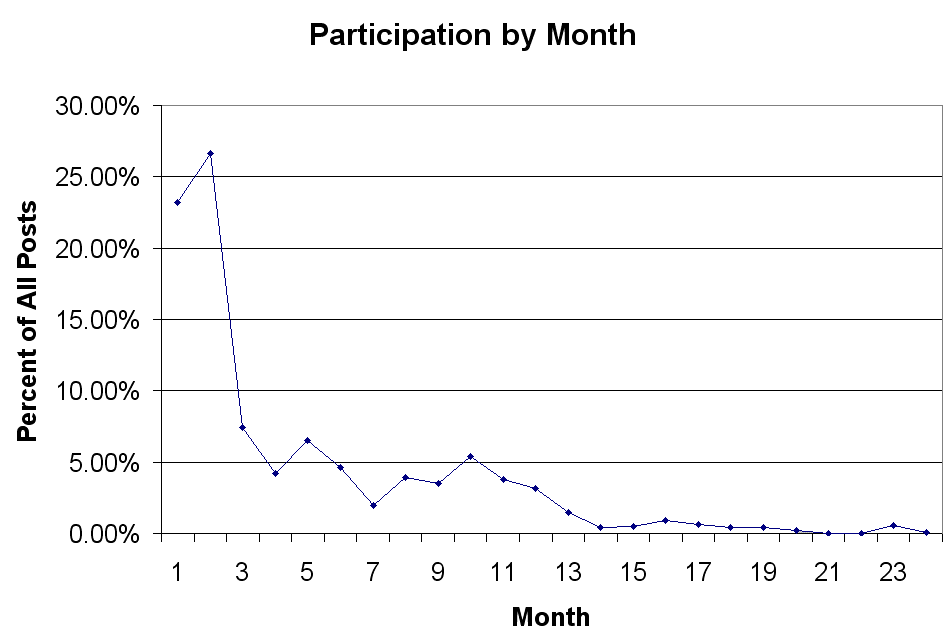

Since the beginning of the Internet, we have seen the same life cycle play out time

and again, and apparently for the same reasons. The short lifespan of collaborative

projects can be seen in the posting activity the groups and forums formed around various

collaborative projects from the past. The activity on these groups follows a nearly

identical pattern in all of the prior projects for which data is available. [2] The graph

1

below shows the number of posts per month for each of the first 24 calendar months of

the life of seven representative projects. [3]

The monthly post numbers were tallied as a percentage of the total number of

posts for each forum so that the averages would not be skewed by the couple of

languages that had an overall higher number of participants throughout their lifespan.

Regardless of the number of participants in each project, however, half of the total posts

ever made for that project were made in the first two months, followed by a sharp drop

off in the third month. Beyond the third month participation continued to drift downward

until the one or two posts per month were often nothing more than spam not related to the

conlang project.

Although the time scale is much compressed due to the high speed of modern

communication, the general shape of the curve matches that described for Volapük over a

century ago.

What are the reasons for the failure of such collaborative projects to have any

longevity? There seem to be a number of significant reasons, and any given conlang

project might stumble at a different point in its life cycle depending on a variety of

factors.

The earliest failures are those that don’t attract enough initial participants to keep

things rolling. Real life has a habit of intruding on one’s hobbies, and there are times

when any given group member might not have the time to participate. For a project with

2

a large enough membership the occasional absence of one or two members would not

adversely effect the group’s level of activity, but if there are only three or four people in

the whole group and two of them have real-life duties that take them away from the group

for a week or two, the project will almost certainly die for lack of participation.

Assuming there are enough interested people to sustain activity, the next hazard is

disagreements about features of the language. Conlanging, being a normally solitary

pursuit, has made conlangers accustomed to calling all the shots themselves. But if some

participants are pushing the project in one direction while other members are pulling it in

a different direction, something’s got to give. If there are enough participants it may

happen that the two factions split apart and launch two different dialects of the conlang.

Examples of this failure mode include the Esperanto/Ido split and even the rift between

the relatively obscure language Lingua Sistemfrater (Frater) and Bartlett’s revised

Frater2. With a smaller number of participants the two factions may not split. Instead

members may simply abandon the project. I’m reminded of one post made by a member

of the Kalusa project: «Ack! I go away for three weeks, and return to find Kalusa

defeated! Oh well. It had a good run. …[addressing certain contributors]… Looks like

you’ve successfully driven everyone off, including me.» Some members suggested

(although I was not able to verify this) that one of the most active “factions” was, in fact,

a single person posting under multiple user names.

If the project survives disagreements the next hazard is the loss of frontiers.

Conlangers are, by definition, interested in creating languages, but it does not follow that

they are interested in using a language that is mature enough that it no longer presents

any significant problems to be solved. When a language reaches a certain level of

usability the design process begins to wind down. Once a painting is finished the artist

sets it aside, and once a conlang is complete it is only natural that a conlanger would set it

aside. Of course a conlang can never be complete in the sense that a painting is complete,

but it can reach a point where only the boring rote tasks remain, such as filling out the

lexicon with names for common tools, food items, plants, animals, colors, weather

phenomena and so on.

A case in point is Larry Sulky’s Ilomi which went public in November of 2005.

One month into the project Larry posted a proposal that the members divide up the

Universal Language Dictionary [4] and each tackle the job of coining words to fill in a

particular lexical category. Through the remainder of that month and halfway into the

next there were a few discussions on grammatical matters, but it was clear that the focus

had moved on to vocabulary building. The language was not complete, by any measure,

but it was clearly ready to be released “into the wild”. It was time for the engineers to

stand down and turn the project over to the user community. Only there was no user

community, so when the builders and tinkerers stood down a month later there was

nobody left to carry on.

What would it take, then, for a collaborative conlang project to achieve vitality

and longevity? Clearly each of the hazards mentioned above would have to be avoided.

First, the number of people involved in the project would have to be reasonably large.

3

Second, the structure of the project should be such that it is resilient in the face of

disagreements, and can accommodate diverse points of view without fracturing. And

finally, there would have to be a user group; people who were more interested in using

the language than in tinkering with it.

Rather than tackling each issue separately, we should consider how the three

problems are, in fact, three facets of the same single issue. That issue is nothing more nor

less than the very reason for the existence of language in the first place. Each of the

hazards discussed above can be addressed from the perspective of this single question:

Why language?

Languages do not prosper because people are interested in language, they prosper

in the service of some greater, or at least more urgent or more desirable end. A language

wins over users for reasons having nothing to do with phonology or syntax, but rather to

fulfill some immediate social need, whether in the market, among friends and family, to

gain status or power, or in service of political, religious, or artistic pursuits. The

discussions among typical users of the language are not «Should verbs inflect for number

of arguments?» but the more mundane: «Help! The goat has fallen into the well.»

It follows that for a conlang to prosper it must occur in a context that has a larger

purpose. The use of the language would need to be a small part of a larger system of

experiences and rewards. As an example, within the community of Star Trek fans, social

status accrues to those who can speak Klingon. In the real world knowing the local

language means being able to buy and sell chickens and cabbages, or plan a picnic, or

help build a bridge. In an online virtual world like Everquest, World of Warcraft, or

Second Life, rewards such as status or power might accrue to those who learn and use the

«native language» of that world. In each case there is some desirable reward for mastering

the language in question.

Although creating and organizing a large physical community in the real world is

out of the question, online communities are a viable alternative. Virtual online worlds

typically have tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of citizens. The online

world Second Life has a population of some 18 million. No matter how interesting or

innovative a collaborative conlang project might appear to linguists, it’s hard to imagine

such a project ever attracting even 18 participants, let alone 18 million.

For a conlang to maintain a large community the language itself must remain

intact. When a person first learns to speak German it would never occur to them to

suggest ways of «improving» or changing the vocabulary or grammar of the German

language. The language is a given; stable, and immutable. Yet who can approach a

conlang for the first time without soon discovering ways in which the language can be (or

even should be) modified and «improved». My own experience with Esperanto is a case

in point. Within the first few weeks of beginning my study of Esperanto I had discovered

a dozen or more things that were clearly «wrong» with the language, and that urgently

needed to be «fixed». When the language itself is seen as something artificial and

arbitrary, this urge to tinker with the language is quite natural, especially to conlangers.

4

But that way lies fragmentation of the community as factions split off to champion one

variant over another as was seen in 1889 with Volapük.

Yet if the language is seen as cast in stone then it is no longer a conlang project,

but a dead language. In order for a language to survive intact through its early formative

stages it must be capable of absorbing change without fracturing into splinter groups.

This is not so much a function of the language itself, but of the community of users. That

community must tolerate diversity, which means that some other «glue» beyond the new

language must hold that community together. The perceived rewards for maintaining

community solidarity must outweigh the perceived rewards for disrupting the community

merely for the sake of promoting a variant language. Continuity also means that there

cannot be any single person or group of people who are seen as the ultimate authority on

proper usage. Such authority, by resisting or prohibiting innovation, invites rebellion.

While there will always be those who would wish to set themselves up as the final

authority, the «common folk» must outnumber, and thus overwhelm the criticisms of the

self-appointed “elite guardians of linguistic correctness». Linguistic anarchy must prevail.

Ain’t no other way to keep the language alive.

Any changes to the language should come about not as the result of discussions,

negotiations, or planning by a central governing body, but as the result of spontaneous

innovation and experimentation by the «common folk» while using the language to

discuss ordinary daily matters quite unrelated to linguistics. These innovations might

extend what is already considered «proper» or they might violate the established «rules».

Either way the survival of the innovation depends solely upon whether that innovation is

picked up and used by other speakers of the language, not upon that feature’s

“correctness” or lack thereof. Language features are, in other words, not engineered, but

used into existence.

In addition to such grass-roots random mutations, there might also be certain

respected «literary figures» who would be in a position to introduce innovations or

refinements in their writing. Again, they would not write about linguistics in general or

the language in particular, but would use their innovations in their writing on other

subjects.

Having addressed the three major hazards that bring about failure of collaborative

projects, however, we seem to have arrived at a point where we are no longer discussing

a constructed language at all. There is no designer or builder, and nothing about the

language is “constructed”. We are, in other words, describing an online contact language

or pidgin. In that case the «conlang project» would not be to design a language, but to

engineer an environment in which a language could be born and evolve in the same way

that all languages have been born and evolved. This would not be a «constructed

language», at all, but a «created language».

Natural languages are never invented out of whole cloth, but evolve and descend

from pre-existing parent languages. A language might descend from a single parent or it

might be result of the blending of two or more parent languages as in the case of pidgins

5

and other contact languages such as Tok Pisin or Chinuk Wawa. For a created language

to evolve in a naturalistic manner within a large community of users there would have to

be a parent language from which it could descend. This language would serve as the

starting point from which alterations and modification could be explored in daily use. If,

however, the parent language were to be a well-established and completely functional

natural language there would be no incentive for innovation since the language would

already be usable as it stands. In that case the language would evolve no faster than

natural languages do, and we might as well just observe natural language evolution «in

the wild.»

On the other hand, if the parent language were to be well defined, but far too

simplistic in its initial state to support normal social and commercial intercourse, there

would be good reason for the user community to «push the envelope» and introduce

innovation in vocabulary and grammar. A good candidate for such a proto-language

would be Sonja Elen Kisa’s Toki Pona with its vocabulary of only 123 words. [5] The

culture of Toki Pona, however, is quite different from the purpose we are exploring here.

Toki Pona is, by declaration, a simple language that is meant to remain simple and

uncontaminated. That is the fundamental guiding principle of its design, and to violate

that principle is considered heresy by the user community. The language has over

600,000 Google hits, and a user group far more active than any collaborative created

language project we’ve discussed so far [6]. On the other hand, having a grammar and

vocabulary cast in stone for all time is a distinguishing feature of a dead language, which

also runs contrary to our purposes.

In its defense, the Toki Pona forums web site does have a forum for «Tinkerers

Anonymous». [7] To quote the forum header, «Some people can’t help making changes to

‘fix’ Toki Pona. This is a playground for their ideas.» This, however, is still a roped-off

and quarantined arena for discussing proposed changes, not using them. Using

innovations outside this sandbox is still frowned upon. In addition, Toki Pona is governed

by copyright and Creative Commons License, which also limits its release into the wild

as a proto-language. It’s takes little imagination to speculate on what might happen to,

say, French if someone where to successfully copyright the language itself.

While Toki Pona itself would not be suitable for the reasons mentioned above,

something along those general lines would be a suitable proto-language for our purposes.

So where does that leave us? We would need, first and foremost, to discover an

overarching higher goal or greater purpose to serve as the justification for the existence of

the user community. That purpose would also need to support some justification for

needing a new language. One could imagine a group of “super villains” intent on taking

over the world wanting a secret language to use among themselves, but that scenario is

neither realistic nor wholesome and productive. Another higher purpose might revolve

around SETI and attempts to communicate with extra-terrestrials using a special

language, but it seems that’s the kind of language that should be engineered. Fans of the

occult might fancy themselves inventing a language of magic, or “intuitively

rediscovering” the lost language of Atlantis. Science fiction fans might become

6

enthusiastic about a fictional alien language that was entirely in the public domain, rather

than being the tightly controlled property of some movie studio or book publisher. Such

fantasies aside, however, discovering an overarching context that meets the necessary

criteria could well be the most difficult part of the entire process.

Once a suitable pretext is found the project structure would need to be designed. It

seems unlikely that a collaborative created language project could ever prosper using the

established techniques of the individual conlanger. In order for the project to succeed the

founders of the project would need to be willing to relinquish all control over the project,

and allow anarchy to reign. Such a project could only happen in the public domain, free

of all procedural and institutional fetters.

That very requirement, however, goes contrary to the inclinations of the average

conlanger who wants to build a language of his or her own, to his or her own

specifications. A project of this sort seems to fall more readily into the category of

experimental linguistics, where the founders of the project are reduced to passive

observers and documenters of the process. They are, in other words, forced from being

prescriptivists into being descriptivists, the very antithesis of conlanging. This would be

especially odious to the conlanger if his creation took on features he strongly disliked.

The ultimate irony of all this is that, whatever the design of the project, it’s unlikely that

this is the kind of undertaking that a «true conlanger» would be interested in.

In summary then, given all the requirements we’ve touched on, what would a

successful collaborative language creation project look like. Here is one possible set of

design specifications. Note that these are not goals for the design of the language, but

goals for the design of an environment in which a language can be created by non-

linguist participants.

1. Some overarching purpose must exist which is served by the language. This could be

social, commercial, artistic, religious, or whatever. The only requirement is that it be

something which is inherently interesting and engaging to sufficient number of people to

support a vibrant and growing community of participating users. Users should come from

a variety of different language backgrounds so that the new language does not tend

toward a relexification of some single language such as English.

2. The culture of the overarching purpose must be one that encourages loyalty and

tolerates linguistic diversity. A participant should never feel the need to leave the

community or to form a splinter group because of linguistic differences of opinion. The

goal is for such linguistic diversity to eventually even out as a «standard» emerges of its

own accord. Until that occurs there is no right and wrong way to say anything in the

language.

3. Participants may join and leave the group any time they feel like it. There are no

commitments to make.

7

4. The web sites and forums used by the user community should be accessible to people

of any linguistic background. Newcomers should be gently introduced to the proto-

language in their own native language, but beyond that, participation in the group should

be a total immersion experience. No languages other than the conlang itself are allowed

within the group. This forces use, which, in turn, forces growth and evolution.

5. The seed language, or initial proto-language from which the conlang is to evolve

should be simple enough that it can be learned quickly, and easily used and expanded

upon by anyone who has even the most basic familiarity with it.

6. The proto-language should be fun to use and play with so that people will enjoy

writing things in the language. This is necessary because it is usage, not authority that

will drive the evolution of the language.

7. There should be a minimum set of initial grammar rules that describe the proto-

language, but these rules are to be considered as nothing more than preliminary

suggestions. Once the language is minimally usable, those rules and guidelines fade away

to be replaced entirely by whatever becomes common usage.

8. If a new rule of grammar is proposed, it can be discussed, among participants, but the

final arbiter is common usage. If people begin to use this new grammatical principle then

it will, by definition, be a part of the language. There is nobody with the authority to veto

or sanction any new grammatical idea. It is either used by the community or not. The

proper way to advocate for a given grammatical principle is to showcase it in a piece of

prose or poetry that others will want to read for its own sake.

9. No grammar rules will be written down by any “official” body. Grammar is taught and

learned by example only. If anyone wishes to write down the rules of grammar as they

exist in common usage it will be understood that these are descriptive only, and will not

constitute a prescriptive grammar. The structure of the overarching organization may be

fixed and governed by rules and regulations, but linguistically, anarchy must be allowed

to prevail.

10. An automated dynamic dictionary and concordance should be maintained online with

entries drawn from the corpus of all contributed writings. This dictionary will not

prescribe words and definitions, but will only describe how the words are being used in

the corpus. Any participant may submit a word to the automated dictionary were it is

added, without the need for review or approval by any higher authority.

11. No idea proposed, or word coined, or principle put into actual use by a particular

writer is inherently superior or inferior. Posterity will judge it to be more useful or less

useful, and no amount of arguing, bickering, or flaming will change the judgment of

posterity. It is not for us to decide what is best for the language. It is for us only to put it

to practical use and let posterity pass judgment by what they keep and what they change.

8

12. While individual writers may certainly copyright their own original works in the

language, no word or grammatical feature of the language may be copyrighted or claimed

as the exclusive property of any person.

In conclusion, then, for a community of users to create a new language requires

that the creation of this novel language be incidental to some higher shared purpose. So

strictly speaking a collaborative conlang project cannot be successful. If a novel language

is to be created, in service of some higher purpose, then it must be created by a

community of non-conlanger language users who have some practical, social, or

ideological reasons for wanting to use that language.

How, then, could a conlanger participate in such a project? Perhaps the only practical

contribution a conlanger could make would be to design some minimal proto-language

along the lines of David Peterson’s Wasabi [3], and then find a way to fire up the

enthusiasm of a large number of potential users for participating in the “birth of a New

World Language”, and turn this community of users loose to do its own thing, with their

only mission being to become evangelists “to help the whole world understand each

other”. But this is not conlanging, or even auxlanging. I’m not even sure what to call

something like that.

FOOTNOTES

———

[1] Kahn, David, The Codebreakers, Scribner 1967.

[2] The projects for which data was collected are: Universal Language (Oct. 2000),

KuJoma aka KuJomu (Mar. 2002), Madjal (Jun. 2004), Ilomi (Nov. 2005), Kalusa (May

2006), Pandumia (Nov. 2007), and Tak aka Lese, aka Minujaninya (Oct. 2008). Data for

Madjal, Kalusa, and Tak is no longer online, but as I am the originator of those projects, I

have the data offline.

[3] Numerous other collaborative conlang projects have been brought to my attention

including David Peterson’s Wasabi project (http://dedalvs.com/wasabi.html), and

Kenakoliku (http://colla.conlang.org/). The first was a one-time classroom based project

and the second, an online bulletin board based group effort whose recent posting activity

appears to be following the classical pattern with these most recent 2010 posting numbers

to an ongoing word creation thread: Apr: 99 posts by 9 people; May: 12 posts by 4

people; Jun: 4 posts by 2 people, July: 1 post by 1 person.

[4] http://www.uld3.org/uld27/index.html and

http://tech.groups.yahoo.com/group/elomi/message/374

[5] http://en.tokipona.org/wiki/What_is_Toki_Pona%3F

[6] http://groups.yahoo.com/group/tokipona/ maintained an active membership with

number of posts averaging between one or two per day to 10 or 12 posts per day. In late

2009 the traffic moved to a dedicated forum at http://forums.tokipona.org/ where 87

members have made nearly 7,000 posts.

[7] The follow message is posted at the top of the forum by the creator of Toki Pona:

9

Tinkerers Anonymous

As the inventor of the Toki Pona language and author of its official website, I have a very

specific vision for my creative work. While I am open to ideas and suggestions, I

unfortunately don’t have the extra time to discuss and give attention to everyone’s ideas of

how to «improve» Toki Pona according to their differing scopes and creative visions.

There will always be people who will want to adapt Toki Pona in one way or another to

better suit their personal goals. Of course you are welcome to invent such derivative

works if you follow the Toki Pona website’s licence. I have created this forum jan nasa li

wile ante e toki pona as a playground for these people’s ideas.

Sonja Elen Kisa

10