Introduction, A Note on the Terminology and

Linguistic Methodology of This Paper, and Section I

Author: Madeline Palmer

MS Date: 01-17-2012

FL Date: 02-01-2012

FL Number: FL-000005-00

Citation: Palmer, Madeline. 2012. Introduction, A Note on

the Terminology and Linguistic Methodology

of This Paper, and Section I. In Srínawésin:

The Language of the Kindred: A Grammar

and Lexicon of the Northern Latitudinal

Dialect of the Dragon Tongue.

FL-000005-00, Fiat Lingua,

Copyright: © 2012 Madeline Palmer. This work is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

!

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

Fiat Lingua is produced and maintained by the Language Creation Society (LCS). For more information

about the LCS, visit http://www.conlang.org/

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

Srínawésin

The Language of the Kindred:

A Grammar and Lexicon of the

Northern Latitudinal Dialect

of the Dragon Tongue

(2nd Edition)

Based on notes written by Howard T. Davis

And

Organized and Adapted by Madeline Palmer

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

Introduction

By Madeline Palmer

If you are a rational person, at this point I would be willing to bet that you are thinking “Is this

serious? Is this really about a dragon language?” While I would not blame you if you were thinking that

right now, I assure you that in the years in which I have been working on this project I have gone from

incredulous, amused, curious, interested and finally to obsessed. So, is this serious? Is this paper really

about a dragon language? I can say without a doubt that this paper is indeed serious, it truly sets out to

describe in detail a fascinating and sophisticated language written down by a fellow linguistics student,

Howard T. Davis, who attended the University of New York between the years 1932 to 1937, apparently the

years that he wrote the notes upon which this paper is based. Is this paper really about a dragon language?

The rational and scientific part of my mind would definitely answer a resounding “no,” but it would also

not tell me to discard any information or evidence a priori without at least giving it a hearing. I do not

know if this language is actually spoken anywhere, much less by dragons, but it certainly is a tale that must

be told.

My involvement in this story begins as I was working on my dissertation as a graduate student. To

anyone who has worked as a graduate student you will understand what this means. Teaching

introductory classes to mostly uncaring students in order to help pay for your serious work, constant

grading of assignments, and research through countless papers in order to find a topic for your dissertation.

Add to this classes, meetings with your advisor, papers, writing, study, reading and sometimes if you are

lucky a little bit of food and even less sleep. While I enjoyed the work, it was often exhausting and those

rare times when I had a little bit of personal time I usually just slept. At one point during my studies, my

advisor suggested that I look through the files that the Linguistics Department kept of old dissertations,

papers, notes and other works published (or in the continual state of “about to be published”) by students

and faculty in the department in order to help me find an appropriate topic for my dissertation.

He let me into the file room, which I discovered was virtually a vault of papers going back to the

founding of the school, covering every conceivable subject with no observable order. He told me I had all

weekend if I needed and I ordered some food, rolled up my sleeves and started sifting through the

mountains of papers in front of me. My personal area of interest is Celtic Languages; Old Irish, Old,

Middle and Modern Welsh, Manx and Breton, in particular, and with the Gods of Academia assisting me I

managed to find a small section which had about twenty papers written on the subject. At this point I was

tired, angry and hungry once again so I grabbed the papers and took them home, hoping to catch a nap and

get back to work with a slightly clearer head. The next day, I started to work through the pile of papers I

had, shifting them into various piles and hoping to find at least a hint of something interesting I could turn

into a dissertation subject. At that point I came across a pile of old notes, about four hundred pages worth

bound in twine and written in a small, precise hand which I almost mistook for typewriter-print. I opened

the package up, which looked like it hadn’t been touched since it had originally been wrapped up, and

started to read.

I was instantly confused. Although it was in the section where the papers on Celtic Languages were

supposed to be kept, these notes were definitely not on a Celtic Language. It was a strange to say the least, a

language which the author called Srínawésin or ‘Many Words’, with even stranger sounds including a ‘qx’, a

word-initial ‘qs-’ sound, a long ‘s’ and what looked like a differentiation between voiced and unvoiced

vowels. The author had copious notes covering every possible subject in the language and included pages

and pages of dialogue between him and several of his sources but when I read his translations they were

particular, always involving hunting, prey animals, territorial disputes and other subjects that I don’t think

the most avid hunter in the world would want to discuss non-stop. The notes were not just on the

language, covering many social concepts and he wrote endless descriptions about the places where he had

met his sources and talked with them for hours, even going on several hunting trips with them. I was just

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

about to shrug, dismiss it as a misfiled anthropological paper from some Amazonian or Australian tribe or

another and put the whole thing down when I turned the page and saw one of the drawings he had done of

one of his “sources.” Although the drawing was quite good, unfortunately it was of a huge, horned dragon

with brilliant red scales and sulfurous yellow eyes, sprawling on a large stone and lazing in the sun.

I stared at the page for a good thirty seconds and then burst out laughing, at which point my

roommate came upstairs to see what I was laughing at after six hours of total silence. I shook my head,

wiped away my tears and waved her away, hardly able to tell her it was nothing and promptly put the

whole thing down. I suppose that laughing wasn’t the correct response, but I had just spent several hours

reading notes written by a man who was precise, methodical, and professional and who obviously didn’t

have much of a social life. In short, he was obviously a linguistics graduate student…albeit a disturbed and

confused one. I had wasted enough time and got back to the more serious linguistic work—work that

wouldn’t get me laughed out of the department. The next day I told some of my colleagues about what had

happened and we all laughed about it and my advisor simply said, “A lot of papers get shoved back there.

Who knows what else is back there?” We laughed and promptly forgot about it.

Well, they did at any rate. I found a dissertation subject on the Old Irish loan-words introduced

into Old Welsh through the various (mostly violent) contacts the Irish and Welsh had during those periods

and began work on it like a good student but one day I realized that when I had thrown the notes down on

my floor I had forgotten to gather them back up and take them back to the archives. At one point, when I

was working on a particularly difficult part of my dissertation I looked down and saw the drawing on the

floor and—deciding it was time for a beer and a laugh—took a break, grabbed a beer and began leafing

through the notes again. I have never really enjoyed the fantasy or science-fiction areas of fiction. I

vaguely remember reading The Hobbit as well as The Fellowship of the Ring as a child and although I enjoyed

The Hobbit all I can remember thinking “There sure is a lot of traveling in this book!” I never got past the

first two chapters of The Fellowship of the Ring and never attempted any of the other books in the series to

this day. I guess that I figured that watching the new movies was enough. And to be honest I didn’t even

really like those.

But, there I was, reading these notes written by a clearly disturbed individual and shaking my head

at the fact that there I was, reading them. Needless to say, they made a great deal more sense now that I

knew who it was that was supposed to be speaking this language and I even tried pronouncing some of the

dialogue to the best of my ability. Which was not very well at all because I had no idea which symbols

meant what or if I was even pronouncing them correctly—as correctly as one can pronounce an invented

language. At that point I began to leaf through the papers and discovered two interesting things. Firstly, I

learned the author was a man named Howard T. Davis who had originally attended school in Britain before

coming to NYU. Secondly, I found a page where he laid out the entire orthography of the language, how

he transcribed the sounds from his “sources” and the various phonological rules therein. With this page in

front of me, I started. The words were tongue-twisting and difficult, like a language comprised solely of

sentences such as “She sells sea shells down by the sea shore,” but with a bit of work and a lot of

concentration I managed to pronounce a few sentences.

It was a bit of fun and I quickly went got back to my more serious work. Over the next few days,

whenever I needed to take a break (and have a beer or three) I would sit down, leaf through the notes and

try some of Davis’ terribly twisting sentences. Unfortunately, he had changed the symbols he used to

represent the sounds several times throughout the years he had worked on the language so one symbol did

not always make the same sound and the same sound wasn’t always represented by the same symbol. So I

started what I now know was the beginning of a slippery slope and began to write down just a few notes of

my own to regularize his orthography and systematize it. After that, it was much easier to read through his

dialogues and I found myself able to pick out simple words and phrases as well as how some of the affixes

were attached to their words and other things that only a linguist would want to do with their spare time.

Unfortunately for me, note-taking is a bit of a compulsion and my “just a few notes” began to turn into an

analysis of how the language was formed, which was strange to say in the least. For the next several weeks

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

whenever I had the chance or needed a break from writing (and couldn’t sleep because my head was so full

of Old Irish mutations, syncopes, habitual past tenses of substantive verbs and other things), I would sit

down and flip through his notes, laugh at the craziness of what he had done and jot down some interesting

points I found in his work.

He constantly referred to two of his main “sources,” the crimson male dragon he had drawn whom

he called Bloody Face and a beautiful female dragon with pearlescent white scales named Moonchild. He

included diagrams, drawings, scratched notes in virtually every free space in his papers, recording

dialogues, lists of words and strange little notes like “blackthorn berries apparently moderately poisonous to

dragons.” He included little biological facts, interesting tidbits and other things which made me think that

not only was this poor man lonely, but that he had some sort of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and

simply wrote down virtually every idea which popped into his head—all of which happened to be about his

imaginary dragon-friends. Despite that, however, he was quite creative and his characters (as I began to

think of them) possessed definite personalities and quirks or their own. Bloody Face was mostly calm and

patient, slow to act but once he did it was with passion and speed. He tended to be a little kinder and less

confrontational then other dragons, preferring to sit and watch events unfold until he was ready to act. But

when he did, he often lived up to his name. Moonchild, on the other hand, was “Xúqxéha sa nuna sa

sráhéš’n” or ‘always lived with fire and wind,’ constantly in motion and never quite happy where she was at

the moment. She was also a bit of a bitch, condescending and a little rude towards Davis although he wrote

in his notes that to her this was a sign of endearment. She and Bloody Face were neighbors and friends

(Davis seemed to think they were both tsiháhíwéš ‘looking at each other as possible mates’) and bickered

like an old married couple.

One beautiful fall day, with the leaves falling outside, I sat reading his notes by the window and

laughed when I read one of the little snide comments that Moonchild directed towards Bloody Face. At

that point I stopped and several things occurred to me. Firstly, without my knowing it, I had begun to

think of these two characters as real and when I laughed I had said aloud “That is so something that

Moonchild would say!” The second—and frankly more frightening thing—was that I was no longer

reading the translation Davis had written…I was, in fact, reading the original Srínawésin text and understood

it. This was a disturbing fact and I was about to put the whole thing down when I had my third troubling

realization. Next to me (now mostly unused and unread because I obviously no longer needed them) were

my “just a few notes” on Davis’ work, which had now grown to almost two hundred pages, about half of

Davis’ original! I grabbed my notes and his, wrapped them up and put them in my desk, hoping that I was

not becoming crazy like Howard obviously had been and walked away. For a while.

Every once in a while, I would look at my desk and realize that I had put a significant amount of

work into those notes and inevitably I opened up my drawer and started looking through our combined

notes and shook my head in amazement. I had spent hours analyzing this language, writing down every

vocabulary word I could find, generating lists of affixes attached to roots, noting grammatical points and

had, without realizing it, become close to fluent in a draconic language. An invented draconic language. That

was hardly the worst part. Not only had I begun to think of Bloody Face and Moonchild as “real” but part

of me was even beginning to debate with my skeptical, scientific, evidence-oriented mind on whether Davis

might not have made all this up. Obviously, this thought had snuck up on me and I was unaware of it even as

I began to think about it. But, what if this wasn’t some lonely person creating his own private little

universe with its own language? The notes he included covered every conceivable aspect of the draconic

lifestyle and had an anthropological—or should I say dracological—consistency to it which would be hard to

simply make up. Davis himself did not appear to have any training as an anthropological linguist and the

way in which the language operated grammatically had some strange (and to my limited knowledge) unique

parts to it. Could this, in fact, be real? Was Davis serious? Could his “sources” actually be real sources to

a real language?

To this day I do not know how to answer those questions. There is a consistency to his work which

defies easy dismissal but frankly I do not want to consider the impact this might have on my worldview. I

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

can accept many things but I’m not sure that I am quite ready to accept the existence of dragons. But,

regardless of my conclusion, I had in front of me literally weeks’ worth of my own (unintentional) work as

well as apparently years’ worth of Davis’ exacting notes as well. Honestly, I am unsure of what I think

about what Davis wrote or what he implied in his work, but I hate to see all that effort sit in a dark, unused

file in the NYU Linguistics Department, only taken out periodically by mistake by some grad student

looking for ideas who would have a laugh and quickly re-file it for the next poor sap to run across. I feel

that Davis, for all his strange quirks and obviously unusual mind, deserves a little better then that. And,

for my part, I must say that after realizing all the work that I did on Srínawésin, I could not consign my

efforts into that same, dusty file. So, after long hours of typing up an arraigning my own notes into a

readable form, I can present Howard Davis’ work to whoever would like to take advantage of it. Any and

all mistakes in this paper are my own and should in no way reflect upon Howard Davis’ scholarship or

ingenuity or upon his “sources.” They are due only to my misunderstanding, mistakes or inability to

understand his notes.

Honestly, I would like to think that this paper can be useful to someone, somewhere. I could find

very little information on Davis himself, he had attended school at NYU for several years as a linguistics

student, but never graduated, never submitted a finalized dissertation (I get the feeling that his notes were

the unfinished form of his dissertation, in which case he was probably laughed right out of the department)

and I couldn’t find any more information on him through the school or state databases. I hope that

wherever he his, in the unlikely case he is still alive, he does not take issue with my adapting and putting

his work out into the world, but I do not think it should remain unread. This is his work, and in a way it

has become mine so I hope this paper is read as such. Read it as you will. If you think this is a bizarre habit

of a disturbed individual (or individuals, I suppose I must say!), the ravings of a lunatic or an interesting

hypothetical linguistic flight of fancy, you are welcome to it. If you think that this paper might possibly be

true, I welcome you to that as well, to this day I am still not sure where I stand on the issue. I just hope my

and Davis’ work can be useful and that someone will be interested in what he started and what I have

continued. I take no ownership of this language, I firmly consider it to be Davis’ own (or for the more

credulous side of me, owned by the actual speakers of this language, if they do exist). I invite anyone to

read it, enjoy it, despise it, think about it, use it or do nothing with it.

I am simply glad it is not sitting in a shelf somewhere.

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

A Note on the Terminology and

Linguistic Methodology of This Paper

This paper, first and foremost, is a linguistic one and although it has information on the culture and

society of dragonkind it still deals primarily with Srínawésin, the Dragon Tongue. I have done my best to

make the terminology in this paper accessible to not just linguists but anyone who might be interested in

the draconic language. I done my best, but unfortunately there is a limit to which a grammar may be

couched in non-technical terminology, so this paper has many linguistic terms and symbology which will

be unknown to many readers. Whenever a particular technical term arises, I do my best to explain it in

laymen’s terms without being either too complex (which will not help in understanding) or simplify the

situation too greatly. Sections of the text which are very interesting from a cultural or “dracological”

perspective but are not all that useful for actually speaking the language are marked with a ‘§’ symbol.

These sections reveal interesting insights on the ways in which the Shúna construct their language and

interact with their world, but for a speaker just wanting to learn to speak they are not as helpful as the

grammatical sections. Additional symbols used in the paper and their meanings are given below:

Symbol

/ /

[]

*

•

◊

†

( )

( )

#

Meaning

Indicates the pronunciation of a word according to the International Phonetic

Alphabet (IPA). For instance, the English word She would be represented as

/∫i:/

Indicates a grapheme or written symbol which represents a particular spoken

sound. For instance, [sh] in English is the way the IPA symbol /∫/ is written

in Standard English.

This symbol indicates that the phrase it is attached to is either ungrammatical or

has never been attested to by a native speaker. Thus, the ungrammatical

English sentence “*Me see the dog” is marked as such.

Indicates that a verb root has an Inherently Possessed subject or object

Indicates that a verb root has two forms, one singular, and the other plural

Specifies that the verb root is an Intentional Actor

In English translations of the Srínawésin original the ( ) indicates that the

bracketed word was not written or spoken explicitly but can be assumed from

the context.

In Srínawésin examples the ( ) indicates that the bracketed section can but

does not always occur. For example, the root qxné(hi)- can occur as either qxné-

or qxnéhi-.

This sign simply means that the word or root to which it is attached to in the

grammar or lexicon is considered to be pejorative, rude, crude or otherwise

combative in nature.

Additionally, because verb-roots in Srínawésin can be derived into adjectives, nouns, true-verbs,

adverbs and so forth I employ a slight differentiation of use when writing a root in this paper. If a root

(without any affixes attached to it) is written syáhu- for example is it to be understood as representing true-

verb or a noun-verb meaning. If the root is written –syáhu it is to be understood as an adverbial or adjectival

meaning. However, if the root has any affixes attached to it, such as –syáhur this indicates that it is a noun-

verb or a true-verb which is not yet complete and requires additional prefixes in order to become a complete

thought. In general, if a draconic word has a hyphen attached to it, it requires an affix to make it a

grammatically functioning word.

When a word, phrase or sentence is analyzed in this paper, the verb-roots of the various words are

indicated by capitalization to assist in parsing (i.e. tsisyáhur analyzed as tsi+SYÁHU+ar).

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

Table of Contents

For

Section I

§Section I: The Kindred………………………………………………………………………………..………………………………………8

§1.1. How Dragons Came to Be…………………………….……………………………………………………………………..8

§1.2. Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………10

§1.3. The Shúna……………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………………10

§1.3.1. Physical Characteristics…………………………………………………………………………………………10

§1.3.2. Geographic Distribution of the Kindred………………………………………………………………….13

§1.3.3. Draconic “Society”………………………………………………………………………………………………..13

§1.3.3.1. Draconic Names……………………………………………………………………………………….14

§1.3.4. Mindset and Worldview……………………………………………………………………………………….16

§1.3.4.1. The Hunt & Predatory Relationships………………………………………………………..16

§1.3.4.2. Amorality……………………………………………………………………………………………….17

§1.3.4.3. Sráhahen and the Natural World……………………………………………………………….20

§1.3.4.4. Cosmology……………………………………………………………………………………………..21

§1.3.5. Draconic Time……………………………………………………………………………………………………..22

§1.2.5.1. The Kindred’s Concepts of “Time”……………………………………………………………23

§1.4. Srínawésin “Many Words” or The Language of the Kindred…………………………………………………25

§1.4.1. Particularities of the Dragon Tongue……………………………………………………………………..25

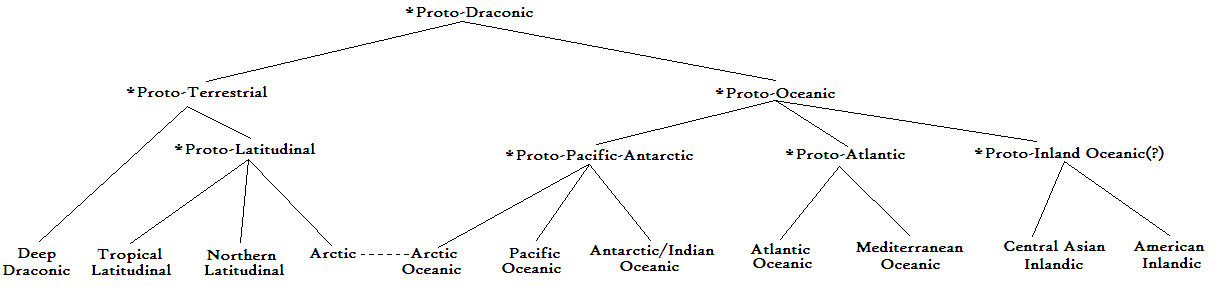

§1.4.2. Dialects and the History of Srínawésin………………………………………………………………….26

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

§Section I:

The Kindred

§1.1. How Dragons Came to Be

I think the best way to begin this paper is with the legend of how dragons came to be in their own

words (the English translation follows on the next page):

Saxenqxéyéwéhen áqxúqxéhawésu’łán tsixenyasuwéhen narúqxéhawésu wix. Saxenqxéyéwéhen

áqxúrúrínsu’łán tsixenyasuwéhen narúrúrínsu wix. Saxenqxéyéwéhen aqxútsúhúqx’łán tsixenyasuwéhen

narútsúhúqx wix. Saxenqxéyéwéhen áqxúnunanárárésin’łán tsixenyasuwéhen narúnunarésin wix.

XúSłéxuTsúhúr shushúnéš thésúsłéxur, shuŠúriwášár, shuTsúhú sa Qsuwér, shuŠátha sa

Yánáhanráqx háła. XúXałirXniyaha shushúnéš thésúxałirha, shuYaweQxéhasu, shuŠáthí sa Tséyaha,

shuRúnáréha níxínxnúyaha’łá. Xútsithí sa sułuthwísu háła, xútsithí sa šéhawísu shuhasawísu háłán

xášiširésin anunarésin átsisa xátsaxésiwésu ašawaqxéhawésu annełusarúrínáqx háłasa’łán xásuqxísnarésu

aháłirésu narúrúrínrésu háłán xáqxéharéshasúrésin awenurésin háłán xáqsáni

sa hałiwałarésin

anunaqxéharésin’łá. Xáéhešéhar aSłéxur xáhaTsúhúr anneXniya nixaXałirha háłán xáwqšéhaha háłán

sashúnuwísu háłasa sarúrínwéxésiwésu aqxéhawésu nasa shán nasa sałéšésiwéha annenunanáráwésin

axniyawéha háłasa’łán saxenráhínwéhen anneraha sa shátséš’łá.

Sashátsásułuthwéhen aTsúhúr xaháSłéxur aXniyaha nixaXałirha háłán

satsayatsuwéhen

tsanqxeyasułuthwéqx háła. Áqxúsa hashusuwéqx ashátsáqx háłasa hatsaqxéhá aQsáhi sa Tséyaha háłán

sayaqxísnaha annesa hahusnawésu asewewésu háłasa łananixaqxéhasu nasa sashátsášathawésu háłasa’łán

xátsithí sa tsatsitsíha’łá. Áqxúsa sasrešu sa tsatsitsíwéqx háłasa sarúrín sa shátsánunar aTsúhú sa

Qsuwér’łán sayaswínar anneqxéhatsitsíwésu annesewewésu narúsa saxésiwésu aháłiwésu háłasa’łán

sashátsáshususin axahánunasin’łá. Satsashałewéhen tsanwáłehúsharéha słáhahasawísu’łán saháxuwéqx

słáhaqxéhasu słáharúrínsu háła, słáhaháłisu słáhaxniyaha’łá, słáhanunasin słáhałusashusur’łá. Saháxuwéqx

natsúhútsitsíqx nałusarúrínwér narúsa naháłáthwéqx háłasa’łá.

Sahúráwésin anunawésin’łá, sahašesin awenusin háłán sareshúwésu asíthrawésu háławx saháłáthwéqx

háłán saxésiwéš shaŠáthíwéš qsansráháqx’łá. Sasłéwá sa sráhašáwáwets’łá, annenatsa sa raha sa síthrawésu,

annesłaša sa qxéhawésu, annešerná sa rúnáwéha, annewárá sa qxíqsewéha słáhahítsáqx słáhaháníqx’łá.

Saxenqsłanéwéhen aTsúhúr xaháSłéxur aXniyaha nixaXałirha annesa tsanrúnha sa síthrawésu sasrasínwéš’łá

tsanshéšusin saqsúławéš háłán saeheswathíwéts anneXałirha nixasraníha háłasa háłán saqxełatsewéts

annewanałrén annewanałréx annewanałrín háłán sahítsá sa qxeqsuwéwéts’łá. Asusawísu sahałín sa

shátsášáwáwéhen annesa saháłáthwéth áwíxuhánwéth qsárhítsewéqx qsasa’łá. Axuhánsusawéth tsaranawéth

háłán átsisa sasrešu sa qxéhawénunaha aXniyaha niXałirha šáxuhánéth háłán sasrešu sa úxtsitsíha háłasa

átsisa sasrešu sa úxnunar aTsúhúr xaháSłéxur annenunarúrínwésin šáxuhánéth háłán sasrešu sa úxshusur

háłása’łá.

Saxuhánwéqsáthir annesa shaŠáthíwéš saháłáthwéš rałúhíntsewéth háłása háłán xúthšáwáwéts

ushúnéš unnexúxuqxéhar unnexúxurúrínar’n xúqsániwér rúxéhášér nwán xwáłsháthunwéts unneTsitsír

qxuhasar nwán xwáłsháthunwéts qxuxúxurúrínar unneQsánir nun. RúxéthésúSłéxur xaháqsáthir xúnxéhášér

xúsráhar shuraha sa Tsitsír tsuntsitsísin nux xúsułúth sa qsánir shuShusu sa Rúrín sa Xúxur nwán xúsułúth

sa sráhar uwéQsánir húnaTsitsír rúxéhášáer nu. UxúSłéxur xahásułuthar unneŠáthíwéš thésúhíntsewéth

xúthšáwáwéts nwán xwáłsháthunwéts qxuhasawér unneShátsár nun.

háłán

tsaqxéhawéreshúha

Hux saranaqx ałanin sa xúxúqx qsawx sashusu sa rusu sa hunłúqx háłán satsasułuthha aXałirha háłán

satsaqxéhaha

xyáséSłéxur

xahánunashusuwésin’łá. Tsitsayatsuha łinanixasułuthwéqx híłán tsíxétsaqxéhá tsinsa tsitséyaha híłasa háłán

tsitsaqsáheha innesa tsiháłátháqx axán tsixésíš shithésúsłatséš híłasa’łá. Xúsráharísu shushúnéš shusa xútsithí

sa qxéqsáthiwéts unnehasarén unnehasaréx unnehasarín nusa urúnha sa síthrawésu urúrínrésu uqsusérésin

uhasharésin uxúłunwésin shusánurísu słúhanása sa Šúriwášár słúhahátha sa Xałirqsáhiha háłán qsúrXałirha

tsusráháqx uxúxuhunłúqx.

xúqxéqsuwéwéts’án

UšithésúXałirha

xúxenshúnuwéts’án xútséyawéš’án xúqsuławéš słúhaSłéxur xahánunarésin nuhún!

xúsráhawéš nwán

xúxutsitsíha

shushúnéš

tsaxinix

háłasa

xyasa

sa

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

The Kindred were born of fire and will one day be returned to the flames. The Kindred were born of

ice and one day will be returned to the ice. The Kindred were born of darkness and will one day be returned to

the darkness. The Kindred were born from the roaring winds and one day will be returned to the winds.

The Night Mother is the Mother of the Kindred; she is the Glittering Span, the Dark Hunter, the

Black Yawning Mouth. The Earth Father is the Father of the Kindred; he is the Flaming Heart, the Old

Sleeper, the Sleeping Place of the Innumerable Mountains. They always coil ‘round each other, always

encircling themselves as the innumerable winds continually hissed as burning rock met frozen void and steam

became frost and lightning chased flame and burning winds mercurially leapt upon boiling water. The Mother

of the Night curled around the Earth Father and he around her and where the frosts met the flames and where

the earth met the roaring winds they mated and made a great clutch of eggs.

The Night Mother and Earth Father wrapped around the eggs and kept them safe within their coils.

When the eggs grew cold the Old Sleeper breathed fire upon them and banished the frost that grew upon them

with his flames and always kept them warm. When the eggs grew too warm the Dark Hunter blew her icy

breath on them, mixing warm flames and frosts until steam came forth and she cooled them with her breath.

For many long life-ages of the world they kept them between themselves, and the eggs lay between fire and ice,

between boiling water and earth, between the wind and the void. They lay in the warm darkness and the icy

void and then they burst forth and hatched.

Winds thundered, lightning danced and the seas trembled but the eggs hatched and the Elders came

forth into the world. The Elders beheld the world with wonder, looking on the great and cool seas, the rushing

flames, the mighty mountains and the wide open plains with delight and desire. The Night Mother and Earth

Father intently watched as the Elders dove into the deep seas, flew in the stormy skies and searched the depths

of the Father and soon they found an abundance of large and small prey creatures and fish to eat and they

hunted well. But when the pair looked back to the clutch of eggs they saw that several had not hatched there

among the broken shells. A pair of unhatched eggs were dead, one because the Earth Father had breathed too

much fire upon it and had heated it up too much, the other one because the Night Mother had breathed too much

of her icy breath upon it and had cooled it down too much.

The Night Mother swallowed the broken shells from which the Elders had emerged and the dead,

unhatched eggs and from that time the Kindred have seen and shall always see the fiery egg which we call the

Sun and the icy egg we call the Moon. The Great Sun moves through our Mother’s belly and across and

through the unreachable vault of the sky every year but the cold, icy egg changes quickly through the sky and

the Moon moves much faster then the Sun. The broken eggs of the Elders are now always seen next to the

Mother’s coils and they are called by the Kindred “the Clutch of Celestial Eggs.”

But the remaining egg was not dead but only cold and sickly therefore the Father coiled around it and

breathed fire upon it, stoking his fires to that he could keep it warm from the Mother’s cold breath. He still

guards it within his coils and breathes on it deep within him while he sleeps and waits for it to hatch and for

our hatch-mate to come forth. The Shúna, the innumerable large prey animals, the innumerable small prey

animals, the fish we eat, the deep seas, the ice, the rains, the weather, the skies and all other things live between

the Glittering Span above and the Old Father below and beneath the Father is the fiery but sickly egg. The

Kindred live, hunt, mate and sleep upon our Father and fly with our mother’s breath as we always have and we

always shall!

This legend was related to Howard Davis by a dragon named Black Honey and occurs again in

Section VIII with more explanation and grammatical specification. But this short story is the world which

the dragons live in the language they use and have used for uncounted æons. It is a fascinating piece of

oral-literature, an insight to their mindset and beliefs, an explanation of how they came to be, a picture of

how they continue to view their world and a small section of this rich and remarkably expressive language.

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

§1.2. Introduction

Before anyone can truly begin to understand the complex and unique language presented in Howard

Davis’ notes I think they must understand the equally sophisticated society which he presents as

underlying the language, as well as the speakers who speak it and the methods and ways in which they deal

with one another and their world. If there was one aspect of Davis’ notes that might make me believe that

he might be telling the truth it would be his many hundreds of pages of notes, diagrams and drawings on

his subjects and the world in which they live in. One day I would like to take the sections of his notes

dealing with these sections and write an anthropological/dracological paper on the “society” he describes.

By attempting to publish this paper, I have already committed a form of professional suicide, so I suppose

that an extra nail in the coffin hardly seems to be out of place. This section will cover most of the non-

linguistic information he detailed about the dragons themselves, physical characteristics, the way in which

they interact with their world, their prey and one another, as well as the mindset and worldview which

guides their actions and which must be understood in order to understand these ancient creatures.

§1.3. The Shúna

The dragons presented in Davis’ notes are truly incredible creatures and he presents many

descriptions of them as well as portraits of many of his most “reliable sources.” In their own language they

refer to themselves individually as Sihá, which means ‘Kindred, One Who Is Similar.’ The plural form of

the word is Shúna or ‘The Kindred, Those Who are Alike,’ and both these terms are synonymous in this

paper with “dragon, dragons,” and “Kindred.” This section covers the Shúna as they are presented in

Davis’ notes, physical characteristics, geographic distribution, society, worldview and concept of time. As I

stated before, you may consider this information as factual or as fantastic as you would like, this is what is

presented in Howard’s notes and I cannot attest to the factuality of his claims. Nor can I prove them to be

wrong.

§1.3.1. Physical Characteristics

In all the sketches that Davis draws, the notes on the physical characteristics of his sources,

drawings and other information he includes one fact glares through his notes: The single greatest

similarity between all the Shúna is their dissimilarity with each other. It seems almost that each

single member of the race is a sub-race in-and-of themselves and the children of two dragons often

have no similarity whatsoever with either their parents or each other. Bloody Face’s scales are a

deep crimson shade with darker hues along the points of his scales, while Moonchild’s are an

incredible pearlescent sheen of white that Davis describes as “shimmering like oil on water.” A

dragon named Scatterlight had utterly black scales which reflected light much like Moonchild’s and

which gave her name. But shading and color are by far not the only differences. Some have no

wings, some have only wings and no other limbs, some have no limbs whatsoever, others such as

Moonchild and Bloody Face have the classic “heraldic” body-form with four legs and wings, some

are wyvern-like with two wings and only two legs. Davis records meetings with a sea dragon

named Wave of the Sea with no limbs but who was covered with spines, webbing and seaweed and

whose scales had a shimmering bioluminescence like a deep-sea fish.

He notes that physical characteristics of an individual have virtually nothing to do with that

of their parents or even their siblings, but seem more dependant on the environment in which the

Sihá is hatched. For instance, Frost Song (whom Davis met only once and was unfortunate enough

to witness another dragon named Ash Tongue kill her in a Šnarír or ‘Blood Hunt’ of vengeance for

some type of wrong) much preferred colder temperatures, glaciers, snow and ice and had

glimmering ice-like scales and deep blue eyes. Her body temperature was so cold it actually burnt

Davis simply by touching her scales and she hated any temperature above freezing. Despite this,

her parents were both “classic” dragons and loved heat (one of which lived in Gobi desert

originally), sitting in the sun and the long, hot days of summer. Frost Song apparently was born

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

during the beginning of one of the past Ice Ages and quickly adapted to the temperatures of the

north, eventually being unable to live in anything else. From Davis’ notes is seems that each Sihá is

a kind of a blank-slate when born, capable of adapting themselves to whatever conditions they find

themselves in, at least when they are young. A dragon born near the ocean or sea can just as easily

slip into the water and eventually turn into a sea-drake as can become an ice-dragon like Frost Song

or the more classic type like Moonchild and Bloody Face. The sheer adaptability evidenced by the

Shúna explains their ability to survive and thrive throughout the long ages of the world; they are

capable in a single generation of becoming virtually a completely different species.

This also explains (if one would care to) the extreme variation in draconic forms in

mythologies throughout the world as well as the variation in dwellings, tendencies and habits. They

simply do not have a single, racial set of physical characteristics without variation. This mutability

apparently only applies to the first several thousand years of their life, they are able to match the

environment perfectly during their adolescence but upon becoming an adult they seem locked in

their physical forms and unable to change. However, Davis notes that he never got an acceptable

answer if the Shúna are capable of adapting themselves after adulthood and hypothesized that given

long enough stretches of time they were capable of performing the same feat.

Despite the huge variation in size, shape, nature and environment of the Shúna, they do have

a set of physical similarities which seem to apply across the race. It appears that most of the Sihá

are capable of dwelling underwater for as long as they desire, are utterly immune to cold (some

because their natural body temperatures are so blazingly hot and others because they are so

incredibly cold!), and are without variation predatory carnivores. They are all scaled and Davis notes

that not only are their scales incredibly hard (he said he was never able to get a sample for testing)

but notes a little-known feature of their scales: they are without exception razor-sharp along their

edges. He writes that running your hand along a dragon’s side from head-to-tail would cause no

difficulty (if the Sihá allowed it, that is!) but from tail-to-head would slice your hands to shreds in

moments. He also notes that in most “classical” dragons, their scales are incredibly hot,

uncomfortable at minimum and often painful to the touch, a result of their searing internal body

temperatures.

The Shúna that Davis met ranged from a mere ten feet long to up to four-hundred feet from

nose to the tip of the tail. They come in all shapes (winged, serpentine, heraldic etc.) but all those

he met had horns, razor-sharp teeth and equally deadly claws. Moonchild’s claws were ghostly

white, almost translucent, while Bloody Face’s were pitch black but both were capable of cutting

steel with ease and both seemed to be of the same material despite their coloration differences.

Some dragons can apparently breathe fire as in the stories, others venom, poison and other equally

unpleasant things and some cannot breathe anything lethal whatsoever except for extremely bad

breath (which Howard describes as a combination of rotting meat, death and bile). Davis notes that

every dragon he met was capable of striking with blurring speed, much like a striking cobra,

although not all of them could move themselves with great speed. The top speed of the “average”

running dragon appears to be about as fast as a sprinting horse or slightly faster, but their ability to

turn and maneuver is not always very good. The larger dragons are incredibly strong, able to crush

rock and stone with their bare hands and easily capable of ripping trees from their roots and hurling

them hundreds of feet. Bloody Face repeatedly warned Howard the danger of draconic blood (on

the rare occasion he and Moonchild got into a “tussle” there was a little bit of blood involved),

which is deadly poisonous, apparently a single drop is capable of turning several thousand gallons

into a liquid which will kill almost anything which drinks out of it. Whatever venom is in their

blood, the Shúna also have a version of it in their saliva and claws, and a single scratch from either

is capable of causing terrible pain and often death. Although with their impossible strength, speed,

razor-sharp edges covering their entire bodies and their other abilities, I don’t see many getting

away with just a scratch.

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

They also possess the most amazing eyesight Davis had ever witnessed. He notes on one

occasion coming upon Bloody Face and Moonchild sitting on a hill in the summer sunshine and

gazing off onto the sea as if they were watching something. When he asked what they were looking

at, they replied they were watching several fishing boats out on the water. Davis strained as hard as

he could but could hardly make out a tiny dot on the horizon, much less tell they were fishing boats.

Just when he thought he was amazed enough Moonchild snorted and said (in English as Davis

wasn’t fluent in Srínawésin at this point):

Moonchild:

Bloody Face:

Moonchild:

Bloody Face:

Hah! All they caught was some greasy cod!

[snorts] No, look, they got a few salmon too.

Where?

Right there in the net they just pulled up, next to the human with the

blue eyes.

Needless to say Howard was astonished that not only could they see that those tiny little

dots were fishing boats but to be able to tell cod from salmon at that distance, much less to be able to

tell the eye color of one of the fishermen was absolutely incredible. He estimated that the boats were

at least fifteen miles out to sea and quickly scrawled in his notes: “I suppose that’s why no one sees

dragons anymore. They see us first!” I cannot really comment on the factuality of this assumption

although it does make a great deal of sense.1

Although there are a great deal of physical variations among the Shúna, there are two things

which they all posses without exception. Davis never met a stupid dragon. They were all, extremely

intelligent, a fact that Davis notes again and again. Most were capable of speaking in several human

languages as easily as Srínawésin, although they much preferred to speak their own language given

the choice. They were all intelligent, devious and extremely difficult to trick, second-guess or con.

This makes a great deal of sense given their extremely long life-span and Howard notes that “There

are very few tricks which they haven’t seen and most of which they invented.” Bloody Face, in fact

was extremely adept at Chess, Go, Checkers, two games I have never heard of called Merels or

Nine-Men’s’ Morris, and Fox and Geese, as well as several ancient games which are no longer

played called Ludus Latrunculôrum, Fidchell, Gwyddbwyll, Âlea Evangeliî, Hnefatafl, Tablut and

others. Howard himself was a good chess-player (according to his own account) but he had a

terrible time winning even a single game against the dragon (who apparently favored the King’s

Gambit). Moonchild distained such games but Davis notes she was just as intelligent as Bloody

Face, capable of speaking English (Old, Middle and Modern varieties), Latin, Welsh, Irish, German,

French, Breton, Old Norse, Danish, Dutch, Gallic Celtic, Russian, Finnish, Hungarian and a

language neither I nor Davis had never heard of called Eusgrae (possibly a form of Proto-Basque?),

which she claimed was spoken across Europe “only a short while ago,” in addition to speaking

Srínawésin. And those were what she could think of “off the top of her head.”

The second characteristic all the Shúna had in Davis notes was their predatory nature. Not

only were they predators in terms of they were incapable of eating anything other then meat, but

they were predators to their very bones. In fact, he never met one, no matter what the “race” or size

that did not make him feel like he was a very little fish swimming with some very hungry piranha.

Even those which he counted as friends could be dangerous when provoked and they all had a

disturbing tendency to stare at him during their discussions, making him feel like “a mouse asking a

cat questions.” Their predatory natures come up again and again in his notes and in their language,

1 The word ‘dragon’ in English originally stems from the Greek word drak- or ‘sharp sighted’ which in turn is derived from the

strong aorist stem derkesthai and even further back to the Proto-Indo-European stem *derk- ‘to see.’ The original meaning of the

Greek usage from which ‘dragon’ comes from appear to be something like ‘one with the sharp or deadly sight,’ which appears to

be an accurate description if Davis’ story is at all true. This information is from Etymonline.com.

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

in the vocabulary, the way they refer to others, how they think about motion and space and a host of

other things, not to mention that several of his sources repeatedly threatened to kill (and not eat

him—the ultimate disgrace) if he asked another stupid question. I believe that despite all the variety

amongst the Shúna, the reason they refer to themselves as ‘Those Who are Alike’ appears to come

not from their physical (dis)similarities, but rather other factors such as their highly intellectual

natures, predatory mindset, shared stories and above all their language.

§1.3.2. Geographic Distribution of the Kindred

Davis describes the geographic distribution of the Kindred in simple terms: Everywhere.

Apparently they have lived on the earth as long as it has existed and have spread—due to their

remarkable mutability—to every inch of the globe. They dwell in lakes, inland seas, and the darkest

depths of the deepest ocean, mountains, glaciers, plains, deserts, jungles, forests, caves and even in

the deepest places of the earth, miles beneath our feet. I find this more then a little disturbing, even

though the rational part of my mind says that it could not possibly be true, the more credulous part

of me still worries.

§1.3.3. Draconic “Society”

“Society” usually means groups of people interacting, fighting, trading and so forth even if it

is on a small, tribal level. Humans are without much exception extremely social, living in groups

ranging from small tribes to huge empires and our societies and languages evolved to suit this kind

of living. The society of the Shúna is conditioned by their biologic natures just as our societies are

conditioned by ours. While humans are all very social and naturally operate within groups of

varying sizes, dragons are the very definition of solitary in the extreme. Partially this is due to their

large size and even larger appetites, dragons consume a large amount of food and their large

territories are essential otherwise they would simply hunt everything edible to extinction within a

few years. The pressure a single dragon can create on any environment is extreme and the only way

not to hunt themselves out of a food source is to live solitary lives with territories spanning large

areas. Mated pairs of dragons (the largest number of dragons Davis ever encountered for any period

of time is two, any more and they would create a catastrophic depopulation of their territory just to

feed themselves) need larger areas, or areas with more resources just to stay alive. Łišáqx or

“hunting territory” is vital to the thought process of dragons and once they have defined an area that

is their łišáqx they will defend it from all threats, either draconic or otherwise, usually to the death.

This is because the loss or destruction of their łišáqx could quite simply lead to their death through

starvation. Draconic “society” is, therefore, is not at all like human society, at least the “average”

human society.

From the descriptions in Davis’ notes, I would liken draconic society to be more like the way

big cats in the Amazon operate with one another then a human society. For both big cats and

dragons, life is solitary for the most part, defined by large hunting territories which they range,

constantly on the search for food. Life is the hunt, the prey and the territory a hunter ranges in. As

long as everyone stays outside of each other’s hunting lands amicable relationships are possible, but

the moment one attempts to take over another’s land or steals food, this is a direct threat and must

be met one way or the other, usually violently. Dragons’ live solitary lives and like it that way,

other dragons are far away in their own lands and meetings (discussions, fights, gossiping) are

almost always held at the edges of two dragons’ territories, an intrusion is interpreted as an invasion

and often leads to violent consequences. All relationships are “long-distance” and except for mated

pairs and hatchlings, dragons will never live with others or interact with one another for more then

an extremely short period of time.

All draconic relationships fall on a continuum between enemy and family. All other Shúna

are, by definition, possible threats in the beginning and dragons will treat others with suspicion and

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

dislike, at least at first. Once an amicable (or at least non-hostile) relationship is forged and

territories are marked out and respected by both parties—therefore there is little need to impinge on

another’s food and less chance of a fight—they may be considered to be “neighbors” rather then

enemies. Dragons may live next to one another for their entire lives and never be anything else to

one another then neighbors. But, often, when two Sihá live next to one another and enjoy each

others’ (periodic) company and there is sufficient reason to do so, they will become “allies or

friends.” Allies will help one another if the other’s territory is invaded but other then that and

periodic visits to chat being another dragon’s friend does not really differ much from being a

neighbor.

Although dragons are intensely solitary creatures they do live “together” with the various

dragons around and near them. Although hunting territory is strictly marked off and rarely if ever

breached (lest there be a serious altercation), a dragon will always know the dragons whose łišáwéqx

border with their own as well as the general conditions and dispositions of dragons’ territories

beyond their immediate sphere. One of the most important distinctions made within the draconic

language is the division and categorization of one’s neighbors into several broad classes: family

members, allies and friends, enemies, and strange or new dragons—the latter two categories

representing a majority of the draconic population from an individual’s standpoint. These

classifications of one’s neighbors are one literally of life and death due the inherently amoral

mindset of dragons.

Therefore, the word “society” can only loosely be ascribed to the Shúna. Rather, they live to

hunt and to do as they will within their territories and in a loosely-knit, extremely fluid world

beyond these territories by which all other relations with other Shúna are couched in terms of

providing protection to one’s lands and maintaining alliances which will allow one to keep one’s

lands. Dragons will almost never work in any group setting, almost never cooperate with others,

either of their own kind or others, although there are extreme examples where a Sihá might work

with others for a short period of time (always to protect one’s own and lands).

§1.3.3.1. Draconic Names

Dragon names come in a variety of forms but each dragon possesses a name like any

other “person.” In fact, they typically possess several names; the name given to them by

various human chronicles and the names given to them by their various other neighbors.

Although they will typically answer to such names when dealing with the others, these are

not in any way their “true” names, the names they think of themselves as and the names

they use with each other. These names are rarely, if ever, told to Qxnéréx2 and their use is

considered to be extremely private and special, which is the primary reason they prefer not to

tell their younger neighbors their real names. While Davis is certainly not the first person to

know a Sihá by their true names, there are very few who are trusted enough for the Kindred

to share their names with. I hope none of Davis’ sources take exception to my publishing of

their names.

Draconic names depend on the circumstances. Usually, when a Sihá is a qxéyéš or

hatchling, they are given a designation by their parents, one which is usually only used to

separate them from the others. Names are always descriptive in nature and usually

diminutive; an example might be the name Sruthax which means ‘male-rabbit’ for a hatchling

that particularly enjoys the taste of rabbit, makes rabbit-ish sounds or otherwise behaves like

a male-rabbit. Eventually, all hatchlings become słáhúš or ‘adults’ and they will usually take

another name at that time. This name might be given to them by others, be taken by

2 This term is the most common draconic name for humans. The root qxné(hi)- means ‘to annoy, to chatter, to speak in an

annoying way,’ and as a noun it means something like ‘The Chatterers,’ apparently a reference to the way our language sounds as

well as our habits of saying things which need not be said.

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

themselves or otherwise applied, but two things always occur. First, the dragon makes the

final decision as to what they prefer to be called (and woe to those who refuse to do so to

their face) and these adult names are always descriptive in nature, often referring to an event,

a distinguishing feature or so on. Sometimes they are ‘known’ by another name by their Sihá

neighbors and usually this name is pejorative in nature, referring to some distasteful aspect

about the victim, although a Sihá will always use another dragon’s preferred name when

actually speaking to the individual—unless they want a fight.

Examples of draconic names in Davis’ papers include:

Angry Face

Shadow

Hathá sa Snaréš

Háqsáqx

Húqsa sa Šáwéqx White Eye

Moonchild

Qsánir sa Qxéyéš

Qsírwanéš

Under the Claw

Wátsí sa Qxítsúqx Ash Tongue

Ríhán sa Wanáqx

Sewe sa Swéhésin

Słáya sa Snáréš

Słáyayánéš

Šátha sa Qxúhusu

Obsidian Claw

Frost Song

Bloody Face

Blood Drinker

Black Honey

Tsitsír xahኳisar

Tswensłéxusu Uqxéhasu

Tsuwášáréšáwéts

Xinunashasúts

Xiyanawášéts

Xíhúréš

Xuqsúłéš Rútháhéwésin

Xuqxátsitsústets

Xuthayá sa Tseyéš

Xutsithí sa Qxéxúnáx

at Something

Tear of the Sun

Born of Fire

Star Gazer

Windchaser

Scatterlight

Dribbler

Stormflyer

Bone Digger

Longsleeper

Always Scratching

And so forth. Sometimes dragons’ names change for various reasons, often

nicknames applied by others slowly stick until the dragon takes this as their true-name. A

good example is a dragon in Scandinavia called Jadescale who had a habit of hibernating for

so long he began to be called Longsleeper by his fellows and eventually he merely adopted the

name and uses it as his true-name. This rarely happens for the most part but it does

sometimes occur. These names can also be given to those who are not dragons. When

Howard first met Bloody Face (an occasion which he does not unfortunately record for I

would be really interested on how this happened) the dragon called him Qxnéx ‘human’ or

Ritsłáx ‘My little prey-neighbor’—implying they lived in proximity to one another.

Eventually the dragon learned his name and called him simply Howard (which he usually

pronounced as Hawarts) or Sayax ‘My little prey-friend.’

After several years, Bloody Face introduced him to Moonchild but when they met

Bloody Face introduced him as:

“TsiHawartsax, xiQsánir sa Qxéyéš. Xutsithí sa qxéxúnáx nihú!”

(This is Howard, Moonchild. He’s always scratching at something!)

The description ‘always scratching at something’ was apparently a reference to Davis’

habit of always scribbling notes down whenever he was talking with one of the Sihá, and

from that moment on, Always Scratching at Something was Howard’s draconic name (a fact

that he was extremely proud of both because he had a dragon-name but also because he felt it

was a testament to his dedicated (I would say compulsive) note-taking) and whenever he

interacted with the Shúna they always referred to him by that name. Apparently Howard’s

“fame” among the Shúna as a qxnéx who spoke Srínawésin spread beyond the immediate

population which he worked with and whenever dragons speak of Howard Davis they still

call him Xutsithí sa Qxéxúnáx ‘Always Scratching at Something.’

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

§1.3.4. Mindset and Worldview

The Shúna’s mindset is about as foreign to that of humans as can possibly be understood.

The human mind and the way we look at the world are conditioned by who and what we are, highly

social creatures who operate in groups. For most of our history we were prey animals of larger

creatures and only periodically hunted or scavenged for meat. Only in “recent” history (the past

several hundred thousand years or so) have we moved into dedicated hunting, agriculture, animal

husbandry and technology which have allowed us to become the “dominant” species on the earth.

Just as our worldview is based on biological and sociological facts, the draconic mindset is based on

their biology, society and who and what they are. Davis at one point notes that: “Dragons live on

the same planet as us but in a totally different world.” An introduction to their “world” as written

or recorded by Davis is below.

§1.3.4.1. The Hunt & Predatory Relationships

Dragons are predators.

The difference between humans and the Shúna mostly revolves around this simple

fact. I do not believe that any human, a hunter who hunts for all their food, the most

competitive athlete or the most vicious serial killer can truly be called a predator. A predator

is not just a hunter, but a creature who obtains all their food by hunting. If a predator does

not hunt and stalk their prey, they will die and there are no second chances. At best, humans

can be described as part-time hunters, we can and often do eat many other foods and even in

the most hunting-based society such as the Iñuit in Alaska and Canada, there are other food

sources to be found.

This is not true of the Shúna. They are carnivores who cannot eat anything but meat

and their lives depend solely on their ability to take prey. Xwaxínáqx or ‘The Hunt’ is the

central point of their lives at all times, it conditions the way they look at the world, they way

they move, think, act, and the way they speak. Xwaxínáqx is such a part of their minds the

word is synonymous with “Life” and a dragon that isn’t hunting in one way or another is

probably sleeping—and dreaming about hunting. If a dragon were to look at a forest or a

stretch of grassland, they would see hundreds of possible ambush sites, xéryuqx or ‘prey-

trails,’ locations where small prey might hide or have their burrows, the lay of the land, the

wind and the possible ways scents might be blown on the wind to hide their location or to

help them track prey without being seen. They understand the atmosphere in a direct,

personal way—as many of them can fly—and have words such as súhu- ‘to dive out of the sun

onto a prey animal,’ hełáthsu ‘a forest with too much cover for prey animals when seen from

the air,’ hushisu ‘an open forest which doesn’t have very much brush and so one can move

silently, but without much cover,’ snésu ‘a snowy forest which shows prey well from the air.’

Almost aspect of their minds and language involves around hunting and the Hunt

conditions every relationship they have in every possible way. Dragons seem to believe

there are only two types of relationships in the world: predator and prey. This works out

nicely for them, of course, because nothing I am aware of would be foolish enough to try and

hunt a dragon. Except for other dragons. The Predator-Prey relationship extends to inter-

Shúna relationships, all other dragons are—by definition—threats in some way to every other

dragon. Two dragons who live next to one another will generally attempt to form at least a

general understanding of where territorial boundaries are and for the most part they are

respected, but in times of difficulty, all bets are off and neighbors will willingly invade

another’s lands to hunt, causing bloody fights for territory. A new or strange Sihá is a threat

and is considered as such until some general understanding can be reached.

There are several exceptions to the “All dragons are dangerous to all others” rule.

Firstly, family members (to a certain extent) will not turn on one another, no matter how

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

bad the hunting is. This does not mean they will cooperate for food, but they will not attack

one another (see §1.3.4.2. Amorality below for a further description of inter-familial

relations). Secondly, sayawéš and tsítsíwéš ‘Allies’ will not attack one another or invade one

another’s territory, although in extremely difficult situations this will sometimes happen.

Except for these two exceptions all other Shúna are competitors at best and outright threats at

worst to be dealt with accordingly, there is simply no middle ground.

This constant Predator-Prey mindset would be extremely stressful to a species that

were not so prepared for a life of constant confrontation. A Sihá has very little to fear from

almost any other creature on this earth, not even the largest predator is willing to tackle even

the smallest Sihá, most species simply instinctively know better then to do that. Davis notes

with some humor that the instinct to fear dragons is as universal as the instinct to fear fire—

which makes some sense in this context. Although extremely large predators (Davis never

notes whether the Kindred and dinosaurs ever interacted) might be willing to defend their

prey from a Sihá, the thought of attacking one of them for food is highly unlikely. Their

speed, impenetrable scales, vicious poison, deadly breath, razor-edged claws and incredible

strength are hardly the most dangerous aspect of these predators. Their minds are devious

and deadly, capable of planning far in advance of even most humans, and certainly farther

then the most audacious predator and every predator on this planet who might have a chance

on taking a Sihá knows this as instinctively as they know to sleep at night. And even if

another predator was successful there appears to be no animal on earth other then another

Sihá which is immune to dragon-venom. Even if they took a Sihá, they would die a horrible

death by merely tasting their blood. Even other Kindred dislike the concept of attacking

another, although not for moralistic reasons, but simply because a dragon is an incredibly

dangerous foe, even to another dragon and few of the Kindred are capable of slaying a

neighbor outright without being severely wounded in the process…and thus possible prey for

another neighbor.

§1.3.4.2. Amorality

If an individual human were to behave as a dragon does for any length of time, within

a week they would almost certainly be diagnosed as a psychotic and be placed within an

institution to “protect society.” The reason for this is quite simple: as humans define

behavior, dragons demonstrate all the classical signs of a psychotic. The Kindred’s sense of

morality is utterly alien from humans in almost every imaginable way, and this leads to

many unfortunate misunderstandings between dragons and qxnéréx. Throughout all human

languages the most common word used to describe dragons is evil. Their morality is

exceedingly different and such a worldview simply does not work within the social

framework of humans because they are not human. But, then again if an ant were to behave

as the normal human does (possessing a sense of self, viewing the survival of it and a small

group of its own as more important then the whole, stealing from others, attempting to breed

to the detriment of the entire colony and so on) it would almost certainly be classed as

psychotic and would be destroyed to “protect the colony.” I do not argue that dragons are

more advanced then us, merely that their sense of right and wrong is extremely different and

can easily be judged as “evil” if it is not viewed in context, just as ants’ society must be

judged in context.

To put it simply, “morality” is a concept utterly foreign to the Kindred. It not that

they think about concepts of good and evil and simply act in an evil way, the whole concept

is totally alien to them and they simply do not consider it whatsoever. They understand the

concepts of good and bad (in a non-moral way like we would think about a food dish as either

good or bad not as good or evil) but their understanding of the words is totally different. They

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

simply take for granted what is good for one is certainly not good for another (meat is good

for them, not so good for the caribou the meat happens to be on when they find it), in fact,

inherent to their mindset is that what is good for one is always bad for another, a product of

their predatory natures. The thought of universal and non-relative Good is about as alien to

them as the Hunt is to us. There is no such thing as Good and Evil in the draconic mind, it

is not a consideration and they have no interest in it.

This mentality is not directed at non-Shúna only, but extends to the Kindred as well.

Howard notes a long conversation he had with Bloody Face and Moonchild a part of which

involved a story they told him about when a new dragon, Frost Song, came to the vicinity

and settled in. She occupied a stretch of land to the north (from the context I believe this

whole story was set in Great Britain, Scotland in particular) which was unclaimed. Another

Kindred in the area by the name of Stormflyer lived nearby and both Frost Song and

Stormflyer did not like each other and did not become allies or friends. Eventually, Frost

Song began to “Saenwásúts anneXuqsúłéš Rútháhéwésin’ła” or ‘Challenged Stormflyer for

control of her hunting territory.’ She began to incur on Stormflyer’s lands, hunting

periodically and leaving the carcasses as challenges to the other Sihá. Stormflyer was too

weak to challenge Frost Song directly and had no friends or allies in the area and did nothing

to show that this behavior was unacceptable. Finally, encouraged by the non-action of the

other female, Frost Song made a direct attack on Stormflyer and chased her right out of her

own lands (but did not attempt to kill her outright) and settled into the combined territories

as her own.

Davis recorded the entire conversation and it is a fascinating exchange between the

two mindsets and it is instructive to present it in its entirety (Srínawésin version is

presented in 8.4. Dialogue between Bloody Face, Moonchild and Howard Davis below):

“That’s terrible. What did everyone else do?”

Davis:

Bloody Face: “What do you mean?”

Davis:

Moonchild:

Davis:

Moonchild:

Davis:

“Didn’t anyone try and stop Frost Song? She was picking on Stormflyer

without a reason! Didn’t anyone have a problem with that?”

“A problem? The problem was with Stormflyer! The fool!”

“What!?”

“She allowed Frost Song to come into her land and take her prey and did not

stop her. She lost her own land, Frost Song didn’t take it. Why would anyone

want to stop that?”

“I thought you said that Stormflyer wasn’t strong enough to fight Frost

Song?”

Bloody Face: “Hah! If she had put up a fight, Frost Song wouldn’t have pushed too far. Not

even she would have wanted a fight to the death with another Sihá, she’s not

that smart, but she isn’t a fool.”

“Besides, even if she (Stormflyer) was weaker then her (Frost Song) and

couldn’t face her, she should have gone to another in the area and forged an

alliance. ‘Fight an invasion by going to a friend’s,’ I always say.”

Moonchild:

“So no one did anything?”

Bloody Face: “As if any of the others to the north would want to be her ally!”

Davis:

Bloody Face: “They were annoyed with Frost Song. She had a territory twice as big as

anyone else’s. She better beware of the others. I wouldn’t mind flying north

and taking some of those lands for myself!”

“Indeed! Great fishing, many seals and even some walrus—”

Moonchild:

Bloody Face: “No the walruses are all gone. Ever since…” [Looks at Davis] “..the Qxnéréx

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

Davis:

came to the Jagged Isle and hunted them away.”

“So let me get this straight. You don’t have a problem with what Frost Song

did?”

“No.”

“And you would do it to another Sihá if you had the chance?”

“Absolutely.”

Both:

Davis:

Both:

Bloody Face: “If someone is so foolish to allow another to take one’s land, they deserve to be

chased off just like Stormflyer.”

That, in a nutshell, is the mentality of the Shúna. Most dragons will periodically

challenge their neighbors in subtle ways, hunting on their lands, leaving the bodies as a

challenge, ranging over their territories and simply seeing what will happen. If the

challenged dragon does nothing and does not respond this is considered to be a virtual

invitation to take the territory from them and the weaker dragon will usually retreat rather

then fight to the death. If the challenged Sihá refuses to give in (and most will not give up

easily) they retaliate by hunting on their opponent’s land and leaving the bodies. Most

Kindred will stop once their challenge is met with a reply, neither side will want to engage in

an actual fight if they can help it. Very rarely, real fights break out and Davis notes that it is

almost always because one side is either vastly stronger then the other or in the rare situation

of a Šnarír or ‘Blood Hunt.’ A Šnarír is a hunt of vengeance, usually caused by some terrible

wrong in the past and will end in the death of one of the dragons.

Other then that, if a dragon does not defend their land it is “their fault” they lost it—

if being at “fault” is even a concept a Sihá might recognize. Further in the conversation,

Howard asks the pair how they could not care, given that Frost Song was likely to keep

attacking until she had the entire island as her territory. They laughed and shook their heads

at this thought (this was fairly early in their relationship with the human). The response

was that if she tried it again the challenged dragon would almost certainly go to an ally for

help and even a foolish dragon would not want to fight two Shúna, no matter how powerful.

Even if she succeeded again all the others in the area would likely take this as a warning sign

and if she tried a third time they would likely band together as a whole and simply slay her

outright in one of the few instances where the Shúna will cooperate in groups. Interestingly,

there is no morality attached to any of this, it was not “right” or “wrong” for Frost Song to

take Stormflyer’s land and it was not “right” or “wrong” for Stormflyer to not fight back,

only foolish. The other dragons who might band together would not do so out of some social

sense of “maintaining order,” but rather because they would be fully aware that if they didn’t

act with the others it, they might be next.

This is the moral—or amoral—world the Shúna live in, morality simply isn’t a

concern of theirs and does not enter into their thought processes. From Davis’ descriptions,

certain dragons such as Bloody Face, who has been around younger races for a long time,

have a vague conception of what humans speak of when we talk about Good and Evil, but

this is not a part of his worldview or daily life. It seems similar to the fact that I have a

vague understanding that the Oort Cloud surrounds this solar system and periodically sends

comets our way, but it is not a part of my life or anyone else’s—except perhaps astronomers.

“Amoral” therefore seems a better description of the Kindred then “evil,” although perhaps a

better and more immediate description would be “dangerous.” The Shúna have a sense of

humor (a very odd and twisted one if Davis’ notes are any indication), but the moment a

threat is perceived to their hunting territory, their livelihood and their life (all of which are

Srínawésin: The Language of the Kindred

roughly synonymous) they will act swiftly, viciously and without compunction against

human, animal or Sihá.

§1.3.4.3. Sráhahen and the Natural World

The Shúna do not possess a sense of religion as we know it. They do not really

possess a creation story per se, at least not in terms humans might consider a creation story.

They have legends where they came from and how the world came to be but neither of these

have any commandments, explanations of why the world is the way it is, social obligations

set down by the gods or anything which is so common in the creation stories of the qxnéréx.

They do not worship anything or even have a sense of an afterlife or anything remotely

resembling religious practice, or belief systems. Despite this, the Shúna in Davis’ notes seem

to have a profound sense of reverence for the world around them and a deep love of it which

he had not seen matched in any human religion. While many religions seek a balance with

the world and appreciate its beauty and respect it, the draconic mindset is one of profound

and deep devotion to the world, the wind, the water, the fire, the earth and the animals which

are their food. This reverence is extremely different then ours as it is shorn of all social

mores and commentary and extorts the Sihá towards no actions or implies any sort of

punishment or rewards. In fact, rewards and punishments are entirely foreign concepts to

them, both being simply swéríwéqx or ‘consequences.’

All religious systems of the qxnéréx are based upon our nature, our social nature.