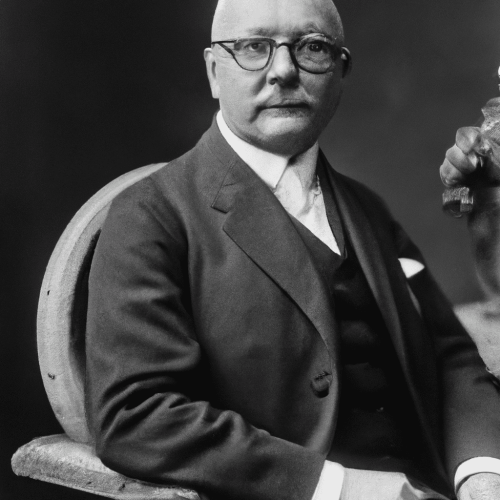

Harold Henry Joachim (1868—1938)

Harold Henry Joachim (1868-1938) was a minor idealist philosopher working in the neo-Hegelian tradition that dominated British philosophy at the end of the nineteenth century. At the time, this tradition was divided into two main camps: personal idealism and absolute idealism. Joachim was affiliated with the latter camp, whose most prominent representative was F. H. Bradley. Although Joachim has frequently been characterized as a mere disciple and promulgator of Bradley’s views, there are instances in which Joachim parts ways with Bradley, showing himself to be an independent and original thinker. These instances will be highlighted below.

Apart from a series of extensive commentaries on individual works by Aristotle, Spinoza and Descartes and an important English translation of Aristotle’s De Generatione et Corruptione, Joachim’s most important work was The Nature of Truth (1906), in which he argued for a coherence theory of truth on the basis of his idealist metaphysics. Joachim’s theory and others like it became a principal foil for G.E. Moore and Bertrand Russell as they began to break with the neo-Hegelian (a.k.a British Idealist) tradition, and to move toward what eventually became Analytic Philosophy. This dynamic between the neo-Hegelian tradition and the emerging Analytic tradition will be illustrated below by considering Bertrand Russell’s criticisms of Joachim’s theory of truth.

Table of Contents

Biography

The Influence of F.H. Bradley

Writings

The Nature of Truth

References and Further Reading

Primary Sources

Books

Articles

Secondary Sources

1. Biography

Harold Henry Joachim (1868-1938) was born in London on 28 May 1868, the son of Henry Joachim, a wool merchant, and his wife, Ellen Margaret (née Smart). Joachim’s father had come to England from Hungary as a child. Both sides of his family were musical—his uncle was the famous violinist, Joseph Joachim, and his maternal grandfather was the organist and composer, Henry Thomas Smart—and Joachim himself was a talented violinist: talented enough to stand in occasionally for absent members of his uncle’s quartet. Early in life Joachim had thought of becoming a professional violinist, but he seems to have been too intimidated by his uncle’s reputation. As a don at Oxford, however, he played frequently, organized his own amateur quartet, and was president of the University Musical Club. Musical examples and analogies appear frequently in his philosophical writings.

Joachim was educated at Harrow School and at Balliol College, Oxford, where he studied with the neo-Hegelian philosopher, R.L. Nettleship. He gained a first in classical moderations in 1888 and in literae humaniores in 1890. In 1890 he was elected to a prize fellowship at Merton College. He lectured in moral philosophy at St. Andrews University from 1892 to 1894, returned to Balliol as a lecturer in 1894, and in 1897 became a fellow and tutor in philosophy at Merton. In 1919 he moved to New College in consequence of his appointment to the Wykeham professorship of logic, a position he held until his retirement in 1935. In 1907 he married his first cousin, Elisabeth Anna Marie Charlotte Joachim, the daughter of his famous uncle. They had two daughters and one son. Brand Blanshard, who was one of his students, described him as ‘a slender man with a mat of curly reddish hair, thick-lensed glasses, a diffident manner, and a gentle, almost deferential way of speaking’ (Blanshard, 1980, p. 19). Joachim was elected fellow of the British Academy in 1922. He died at Croyde, Devon on 30 July 1938.

2. The Influence of F.H. Bradley

Joachim was a minor philosopher working within the neo-Hegelian idealist movement which dominated British philosophy at the end of the nineteenth century (cf. the article on Analytic Philosophy, section 1). Joachim’s contributions to neo-Hegelianism came late in the day, when the movement was already in decline, and this has meant that, although his work (especially the work he did before the First World War) was taken seriously when it appeared, it did not have the lasting significance that its initial reception suggested.

In Joachim’s day, Neo-Hegelianism was divided into two broad camps: the personal idealists, like J.M.E. McTaggart, who held that reality consisted of a multiplicity of inter-related individual spirits; and the absolute idealists, led by F.H. Bradley, who held that it consisted of a single, relationless, spiritual entity, the Absolute. Joachim belonged firmly in the absolutist camp.

There is no doubt that the strongest philosophical influence on Joachim was F.H. Bradley. T.S. Eliot, one of Joachim’s students, wrote that Joachim was ‘the disciple of Bradley who was closest to the master’ (Eliot, 1964, p. 9) and this seems to have been a widely held opinion. There is, indeed, a degree of truth in this, but it should not be exaggerated. Bradley and Joachim had a long professional association: Joachim’s most productive years as a philosopher were spent at Bradley’s college, Merton, where they had neighbouring rooms. (G.R.G. Mure (1961), reported that Joachim would shut the windows when Mure started to criticize Bradley, lest the great man hear.) Nonetheless, there does not seem to have been a close personal relationship between the two philosophers, for Joachim was diffident and Bradley was overbearing. Since Bradley did no teaching, students who went to Oxford to learn Bradley’s philosophy usually ended up learning it from Joachim (who probably did a better job of teaching it than Bradley would have done, for Joachim was, by all accounts, an able teacher). After Bradley’s death, it was Joachim who edited Bradley’s Collected Essays and who was responsible for completing Bradley’s famous final essay on relations which was included in that collection. A number of letters from Bradley to Joachim have been preserved, but only one from Joachim to Bradley (Bradley 1999).

Joachim’s reputation as Bradley’s closest acolyte was a mixed blessing. On the one hand, so long as Bradley remained a force to be reckoned with in philosophy, it ensured that Joachim’s work received careful attention; but once Bradley became a figure of mainly historical interest, Joachim’s own contributions to philosophy were largely forgotten.

While there is no denying Bradley’s influence on Joachim, it should not be thought that Joachim’s own philosophical writings were merely elaborations of Bradley’s position. In particular, the widely held view that Joachim’s most important original work, The Nature of Truth (1906), was an elucidation (or at most an extension) of Bradley’s views on truth, is a mistake, and one which has led to decades of misunderstanding about the theory of truth that Bradley actually held. Joachim’s theory is plainly one that is tenable only within a broadly Bradleian metaphysics, and at the time Joachim wrote no other such theory had been elaborated in detail. Nonetheless, Joachim himself was far too careful a commentator to suggest that the coherence theory of truth he put forward in The Nature of Truth was actually held by Bradley. Moreover, when Bradley himself started writing about truth (at about the time Joachim’s book was published), he made hardly any reference to Joachim. His collection of papers on the topic, Essays on Truth and Reality, contain exactly one reference to Joachim: he says merely that Joachim’s book is ‘interesting’ and that Joachim ‘did … well to discuss once more that view [which both of them rejected] for which truth consists in copying reality’ (Bradley, 1914, p.107). This is surely a case of damning by faint praise. And it is not insignificant that Joachim’s work on Bradley’s Nachlass (his posthumously published collected papers) mentioned above was assigned to him not by Bradley himself, but by Bradley’s sister, who was his literary executor. Thus there is no indication that Bradley thought his mantle should be passed to Joachim.

And there is at least one important respect in which Joachim would have wanted to disown Bradley’s mantle. Right at the end of his posthumously published Logical Studies he ventures a fundamental criticism of Bradley’s metaphysics for not being Hegelian enough. Bradley’s Appearance and Reality ends, famously, with a chapter called ‘Ultimate Doubts’. The title might seem ironical for a chapter in which he says that ‘our conclusion is certain, and … to doubt it logically is impossible’ (Bradley 1893, p. 459), but there is one respect in which the doubt is real. While Bradley maintains that he has proven that the Absolute is a perfect system in which ‘every possible suggestion’ has its logically ordained place, yet this ‘intellectual ideal’ is impossible for us to grasp: ‘The universe in its diversity has been seen to be inexplicable…. Our system throughout its detail is incomplete’ (ibid., p. 458). In this respect, Joachim maintains, Bradley’s Absolute differs from Hegel’s, and Hegel’s is much to be preferred (Joachim 1948, pp. 284-92). In this, Joachim sides with the many neo-Hegelian critics of Bradley who objected to his generally sceptical conclusions: indeed, Bradley himself described his book as ‘a sceptical study of first principles’ (Bradley 1893, p. xii). Such scepticism was not for Joachim, though there is nothing in his entire corpus which indicates how the Absolute might, in detail, be made explicable.

3. Writings

A complete list of Joachim’s philosophical publications appears at the end of this article. Here we will survey his most significant writings.

Joachim’s most important original work in philosophy was The Nature of Truth (1906), a defence of the coherence theory of truth. Truth was also the topic of three of the six papers he published in Mind. Joachim’s views on truth will be the subject of the next section, we will forego further commentary on them here.

Apart from his work on truth, almost all his other work consisted of scholarly studies of particular works of ancient or early modern philosophers. His first book was an important commentary on Spinoza’s Ethics (1901), and he followed this with two translations and commentaries (De Lineis Insecabilibus and De Generatione et Corruptione) for W.D.Ross’s edition of Aristotle’s works in English (1908, 1922). These Aristotle translations were probably his most enduring work. His translation of De Generatione et Corruptione remains in print, having been reprinted as recently as 1999, and it was for many years the standard translation, being superseded only in 1982 by C.J.F. Williams’ translation in the Clarendon Aristotle Series.

The only other works he published in his lifetime were three papers (two on scholarly points in ancient philosophy), his inaugural lecture as Wykeham professor (a work scathingly reviewed by Russell, 1920), a book review, and a letter to the editor of Mind.

Considerably more work appeared after his death than he had published in his lifetime. The posthumous works were based upon the meticulously written out lecture courses he had given at Oxford over many years. With one exception, Logical Studies (1948), the posthumous volumes were all scholarly studies of specific works of other philosophers: a commentary on Spinoza’s Tractatus de Intellectus Emendatione (1940), a study of Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics (1951), and a study of Descartes’ Rules for the Direction of the Mind (1957). In these commentaries, Joachim was concerned primarily with an exact explication de texte, and they are renowned for their meticulous attention to detail. Stuart Hampshire (1951, pp. 9-10) said that Joachim had written two of the three ‘most careful studies of Spinoza in English’. The carefulness of their exposition makes them well-worth reading even today, though the philosophical language in which they are couched and the philosophical presuppositions underlying it belong to the largely forgotten era of late nineteenth-century idealism. While they remain valuable commentaries, their neo-Hegelian ambiance can be intrusive: there are occasions where Joachim seems to suggest that if Spinoza had been a better metaphysician he would have been Bradley.

There is no doubt that Joachim found the close reading of classic philosophical texts especially congenial. He seems to have started the practice as an undergraduate under the guidance of J.A. Smith at Balliol. His relationship with Smith was close: starting in the 1890s, they frequently worked together on the interpretation of Greek philosophical texts and from 1923 to 1935 they gave a class each week during term devoted to the reading of selected texts from Aristotle (Joseph, 1938, pp. 417-20). During the vacations, Joachim prepared for these classes with extraordinary thoroughness. Smith recalled that he was often prepared to suggest improvements to the text, especially as regards punctuation. Indeed, T.S. Eliot (1938) credited his understanding of the importance of punctuation to Joachim’s exposition of the Posterior Analytics. Rather more surprising, Eliot also said that Joachim taught that ‘one should avoid metaphor wherever a plain statement can be found’. This is surprising because Joachim’s own works, like Bradley’s, are replete with metaphors, often in places where a plain statement is imperatively demanded. Indeed, his style seems to me a serious weakness, especially in his original philosophical work. Where argument is called for, he has a tendency to rhapsodize instead.

As mentioned above, only one of Joachim’s posthumous books was a work of original philosophy. This was his Logical Studies (1948), edited by L.J. Beck from the fully written-out lectures Joachim delivered as Wykeham professor from 1927 to 1935. Although Beck in the Preface reports Joachim’s opinion that these are ‘the fullest written expression of his own philosophical opinion’, they are, frankly, disappointing. It is indeed astonishing that material like this should have been taught as logic at a major university as late as the 1930s. Although it was no doubt inevitable that the major advances in formal logic of the previous fifty years would not have featured in the lectures of Oxford’s professor of logic, it is notable that he did not cover any of the main topics of traditional logic either – topics like induction and deduction, names, propositions, inference, and modality; the sort of material to be found in W.E. Johnson’s Logic, which came out about the time Joachim took up his chair. The material Joachim covers is much more concerned with metaphysics and epistemology than with logic.

The work contains three studies. The first deals with the question ‘What is Logic?’ After a long discussion, Joachim concludes that it is ‘the Synthetic-Analysis or Analytic-Synthesis of Knowledge-or-Truth’ (1948, p. 43). It is impossible to make adequate sense of this cumbersome phrase without an extended discussion of the metaphysics of Absolute Idealism, but such a discussion falls beyond the scope of this article (see the articles on Analytic Philosophy and G.E. Moore for brief descriptions of the metaphysics of Idealism). Suffice it to say that, by ‘Synthetic-Analysis or Analytic-Synthesis’, Joachim meant a certain kind of mental activity that was simultaneously analytic and synthetic:

… it brings out, makes distinct, the items of a detail by bringing out and making distinct the modes of their connexion, the structural unity (plan) of that whole, of which they are the detail; in a word, so far as it is a two-edged discursus, analysing by synthesizing and synthesizing by analysing. (p. 38)

and that, by ‘Knowledge-or-Truth’, he meant reality and mind considered together as an internally-related whole:

It is truth … in the sense of reality disclosing itself and disclosed to mind – to any and every mind; and, being truth, it is also and eo ipso knowledge – i.e. the whole theoretical movement, the entirety of cognizant activities, wherein the mind (any and every mind qua intelligent) fulfils and expresses itself by co-operating with, and participating in, the disclosure. (p. 55)

Any greater clarity on these matters is, as already stated, impossible to achieve without a protracted discussion of Idealist metaphysics; but even with such a discussion there remain questions about the ultimate cogency of these views.

The second (and longest) study is an attack on the distinction between immediate and mediate (or, as Joachim puts it, discursive) knowledge. The bulk of the study is taken up with an attack on the notion of the given (a datum), whether derived from introspection, sense-experience or conceptual intuition, on which immediate knowledge could be founded. The final study concerns truth and falsehood, and reprises the views he set forth in The Nature of Truth. Joachim’s views on truth as presented in both of these texts will be considered in the next section.

4. The Nature of Truth

By far, Joachim’s most important contribution to philosophy was his book The Nature of Truth (1906), in which he defends a coherence theory of truth. Even so, nowadays the book is probably best known for having provoked a long response from Bertrand Russell (Russell, 1907), in which Russell set forth most of what have become the standard arguments against coherence theories of truth.

Joachim’s book had four chapters: the first was a critique of the correspondence theory of truth; the second a critique of Russell’s and Moore’s early identity theory of truth ‘as a quality of independent entities’ (see the article on G.E. Moore, section 2b); the third put forward Joachim’s own coherence theory; and the fourth dealt with the problem of error. The third part of Joachim’s Logical Studies dealt with essentially the same material in the same order, but from a slightly different point of view.

In Logical Studies Joachim approached the topic through an investigation of the nature of judgements (or propositions) as the bearers of the predicates ‘true’ and ‘false’. He first rejects, on grounds drawn mainly from the first chapter of Bradley’s Principles of Logic, the view that a proposition is a mental fact which represents an external reality (this is the sort of view that gives rise to the correspondence theory of truth). Bradley’s argument, which Joachim repeats, was that beliefs, considered purely naturalistically as mental states, could not be considered to represent or be about anything outside themselves, any more than any other natural state could.

Secondly, he attacks the view that a proposition is an objective, mind-independent complex—the view which underlies the Russell-Moore identity theory. Against the Russell-Moore view, he has two objections: first, that the theory can give no account of how the mind can access the proposition; second, that the theory is forced to postulate false propositions as having the same mind-independent complexity as true ones. There is an interesting shift of emphasis here from his treatment in The Nature of Truth. In that earlier work, Joachim emphasized the first objection and based it firmly in his neo-Hegelian doctrine of internal relations—for which he was roundly criticized by Russell (1907; see below). In Logical Studies, the doctrine of internal relations is more or less ignored, and Joachim concentrates on the strangeness of Russell’s and Moore’s propositions, especially the strangeness of false propositions.

The third view, which Joachim endorses, is the idealist view in which the judgement is, to put it entirely in his own words, ‘the ideal expansion of a fact – its self-development in the medium of the discursus which is thought, and therefore through the co-operative activity of a judging mind’. A judgement is true ‘because, and in so far as, it stands or falls with a whole system of judgements which stand or fall with it’ (Joachim, 1948, p. 262).

This account, though lacking a good deal in precision, is actually clearer than that given in The Nature of Truth, where readers are bewildered by a variety of different accounts, and are left to work out for themselves how these might be regarded as descriptions of a single concept of truth rather than of several different concepts. It is worth quoting a few of Joachim’s differing statements from The Nature of Truth, since it will give a taste of the exegetic difficulties involved in his work. In one place he says that anything is true which is ‘a “significant whole”, or a whole possessed of meaning for thought’ (Joachim 1906, p. 66). Later he says that truth is a ‘process of self-fulfilment’ and ‘a living and moving whole’ (ibid., p. 77). Again later he says that it is ‘the systematic coherence which characterizes a significant whole’ and ‘an ideally complete experience’ (ibid., p. 78).

All of this is considerably less helpful than it might be, though it does serve to introduce what can be taken as the central notion of Joachim’s theory, that of a ‘significant whole’. Unfortunately, Joachim gives two different accounts of even that central notion: on pages 76 and 78 it is ‘an organized individual experience, self-fulfilling and self-fulfilled’; on p. 66, however, ‘A “significant whole” is such that all its constituent elements reciprocally involve one another, or reciprocally determine one another’s being as contributory features in a single concrete meaning.’

This latter account is clearer and more helpful in understanding his actual view. The idea that all the elements of a significant whole ‘reciprocally involve’ one another amounts to the claim that the intrinsic properties of each part determine the intrinsic properties of all the others. It is the intrinsic properties of each element that are determined because Joachim, in common with other neo-Hegelians, subscribes to a doctrine of internal relations, according to which relations are grounded in the intrinsic properties (or ‘natures’, to use Joachim’s word) of their terms. So the relations of the various parts are determined once the intrinsic properties are.

Bertrand Russell, in his critique of Joachim’s theory, argues that Joachim’s version of the coherence theory of truth entails and is entailed by the doctrine of internal relations:

It follows at once from [the doctrine of internal relations] that the whole of reality or of truth must be a significant whole in Mr. Joachim’s sense. For each part will have a nature which exhibits its relations to every other part and to the whole; hence, if the nature of any one part were completely known, the nature of the whole and of every other part would also be completely known; while conversely, if the nature of the whole were completely known, that would involve knowledge of its relations to each part, and therefore of the relations of each part to each other part, and therefore of the nature of each part. It is also evident that, if reality or truth is a significant whole in Mr. Joachim’s sense, the axiom of internal relations must be true. Hence the axiom is equivalent to the monist theory of truth. (Russell 1907, p. 140)

Russell’s argument is swift, but, when unpacked fully, can be shown to be valid (see Griffin 2008). Russell, of course, rejects the doctrine of internal relations, which he goes on to criticize at length, but he also has several other criticisms to make of the theory which are independent of the theory of relations.

One serious problem faced by all coherence theories of truth is that of eliminating the possibility of there being two distinct significant wholes, i.e., two competing, but equally coherent, systems of propositions, for then the theory would entail that there were two incompatible sets of truths. Joachim tries to avoid this by requiring that a significant whole which constitutes truth must have ‘absolutely self-contained significance’ (Joachim 1906, p. 78); he maintains that there can be only one such significant whole, the Absolute itself.

It is hardly certain that this follows, but, even if it does, the result is still problematic. If the Absolute is the only significant whole, then only what is part of the Absolute can be true. Now, as we have seen, Joachim (at least in his late work) rejects the ineffability with which Bradley shrouded the Absolute. And yet he also rejects the possibility that the significant wholes into which we compose our actual beliefs ever coincide exactly with the Absolute. It follows then—and Joachim accepts the implication—that all our actual beliefs are false. But he holds also that they are all, also, to some degree true, since each to some degree coheres with the others. This ‘degrees of truth’ doctrine is the expected, if somewhat counter-intuitive, consequence of a coherence theory of truth: since coherence comes in degrees, so, too, must truth (Joachim, 1948, pp. 262-3). It seems, then, that all our beliefs are more or less true, according as they form significant wholes which come more or less close to coinciding with the Absolute. This is certainly an intelligible view, but ultimately it does not look like a coherence theory: truth simpliciter consists in the coincidence of belief with the Absolute, and ‘coincidence’ here looks very much like another name for correspondence; coherence is merely a measure of verisimilitude, the degree to which beliefs approach coincidence with the Absolute.

Nor is it a theory which would have Bradley’s acceptance, for Bradley’s argument for the claim that it is logically impossible to doubt his account of the Absolute, rests on the claim that any idea ‘which seems hostile to our scheme … [is] an element which really is contained within it’ (Bradley, 1893, p. 460), that the Absolute contains every possible ‘idea’. But if this is the case, then, on Joachim’s theory of truth, either all beliefs are absolutely true or else the Absolute is not absolutely coherent.

Joachim is thus faced with two problems: (i) the problem of accounting for error in a theory in which every belief is to some degree true; and (ii) the problem (as Joachim puts it, 1948, pp. 266-9) of deciding whether, given that the Absolute must be absolutely coherent, our beliefs are true because they are stages in an unending dialectical movement towards the Absolute or because they are part of the timelessly complete Absolute itself.

Joachim’s response to (i), in The Nature of Truth, is to claim that error consists in ‘an insistent belief in the completeness of my partial knowledge’ (1906, p. 144): ‘[t]he erring subject’s confident belief in the truth of his knowledge distinctively characterizes error, and converts a partial truth into falsity’ (ibid., p. 162). This is hardly satisfactory. Russell’s rebuttal is too brief and too amusing not to quote:

Now this view has one great merit, namely, that it makes error consist wholly and solely in rejection of the monistic theory of truth. As long as this theory is accepted, no judgment is an error; as soon as it is rejected, every judgment is an error…. If I affirm, with a ‘confident belief in the truth of my knowledge’, that Bishop Stubbs used to wear episcopal gaiters, that is an error; if a monistic philosopher, remembering that all finite truth is only partially true, affirms that Bishop Stubbs was hanged for murder, that is not an error. (Russell 1907, p. 135)

As regards (ii), in The Nature of Truth Joachim finds the problem insoluble: ‘We must be able to conceive the one significant whole, whose coherence is perfect truth, as a self-fulfilment, in which the finite, temporal, and contingent aspect receives its full recognition and its full solution as the manifestation of the timeless and complete’ (1906, p. 169). But ‘the demands just made cannot be completely satisfied by any metaphysical theory’ and we must recognize ‘that certain demands both must be and cannot be completely satisfied’ (p. 171). Moreover, as he goes on to point out, since the coherence theory cannot satisfy these demands, it cannot itself be coherent, and thus cannot be true (p. 176). This is a somewhat surprising end to his discussion.

In Logical Studies he is slightly, but only slightly, more sanguine. There, as we have seen, he appeals, over Bradley’s head, to the Hegelian dialectic to reconcile the timeless ideal with the temporal approximation. But how this effect is achieved he doesn’t say.

5. References and Further Reading

a. Primary Sources

The following list includes all Joachim’s philosophical writings.

i. Books

A Study of the Ethics of Spinoza (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1901).

The Nature of Truth (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1906).

De Lineis Insecabilibus (translation, with full footnotes) in The Works of Aristotle, ed. by W.D. Ross, vol. 6 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1908.

Immediate Experience and Mediation. Inaugural Lecture. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1919).

De Generatione et Corruptione. (translation, with a few footnotes.) in The Works of Aristotle, ed. by W.D. Ross, vol. 2 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1922).

Aristotle on Coming-to-be and Passing-away. A revised text of the De Generatione et Corruptione with introduction and commentary. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1922).

Spinoza’s Tractatus De Intellectus Emendatione: A Commentary (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1940).

Logical Studies, ed. by L.J. Beck (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1948).

Aristotle: The Nicomachean Ethics. A Commentary, ed. by D.A. Rees (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1951).

Descartes’ Rules for the Direction of the Mind, ed. by Errol Harris (London: Allen and Unwin, 1957).

ii. Articles

1903. ‘Aristotle’s Conception of Chemical Combination’, The Journal of Philology, vol. 29, pp. 72-86.

1905. ‘“Absolute” and “Relative” Truth’, Mind, vol. 14, n.s., pp. 1-14.

1907. Review of Dr. S.R.T. Ross’s edition of Aristotle’s De Sensu et Memoria. (Text and Translation, with Introduction and Commentary: Cambridge University Press, 1906.) Mind, vol. 16, n.s., pp. 266-71.

1907. ‘A Reply to Mr. Moore’, Mind, vol. 16, n.s., pp. 410-15.

1909. ‘Psychical Process’, Mind, vol. 18, n.s., pp. 65-83.

1911. ‘The Platonic Distinction between “True” and “False” Pleasures and Pains’, Philosophical Review, vol. 20, pp. 471-97.

1914. ‘Some Preliminary Considerations on Self-Identity’, Mind, vol. 23, n.s., pp. 41-59.

1919. ‘The “Correspondence-Notion” of Truth’, Mind, vol. 27, n.s., pp. 330-5.

1920. ‘The Meaning of “Meaning”’ (Symposium), Mind, vol. 29, n.s., pp. 385-414.

1927. ‘The Attempt to conceive the Absolute as a Spiritual Life’, The Journal of Philosophical Studies, vol. 2, pp. 137-52.

1931. ‘“Concrete” and “Abstract” Identity’ (Letter), Mind, vol. 40, n.s., p. 533.

b. Secondary Sources

Blanshard, Brand (1980), ‘Autobiography’, in P.A. Schilpp (ed.), The Philosophy of Brand Blanshard (Chicago: Open Court), pp. 2-185.

Bradley, F.H. 1893, Appearance and Reality. A Metaphysical Essay (Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2nd edn., 9th impression, 1930).

The work which most strongly influenced Joachim’s philosophy.

Bradley, F.H. (1914), Essays on Truth and Reality (Oxford: Clarendon Press).

Bradley, F.H. (1999) The Collected Works of F.H. Bradley, vols. 4 and 5, ed. by Carol A. Keene (Bristol: Thoemmes)

Contains Bradley’s letters to Joachim, but only one of Joachim’s to Bradley.

Connelly, James and Rabin, Paul (1996), ‘The Correspondence between Bertrand Russell and Harold Joachim’, Bradley Studies, 2, pp. 131-60.

Transcribes most of the extant correspondence between Joachim and Russell; most of it connected with the theory of truth.

Eliot, T.S. (1938), ‘Prof. H.H. Joachim’ The Times, 4 August 1938.

Eliot, T.S. (1964), ‘Preface’ to Eliot, Knowledge and Experience in the Philosophy of F.H. Bradley, (New York: Farrar, Straus).

This was Eliot’s Harvard doctoral dissertation completed in 1916 and written under Joachim’s supervision.

Eliot, T.S. (1988) The Letters of T.S. Eliot, vol. 1, 1898-1922, edited by Valerie Eliot (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich).

Eliot’s letters from Oxford, especially to his former Harvard professor, J.H. Woods, contain much information about Joachim’s classes.

Griffin, Nicholas 2008, ‘Bertrand Russell and Harold Joachim’, Russell: The Journal of Bertrand Russell Studies, n.s. 27, pp.

A survey, biographical and philosophical, of Joachim’s relations with Russell, his most persistent critic.

Hampshire, Stuart (1951), Spinoza (Harmsworth: Penguin).

Joseph, H.W.B. (1938), ‘Harold Henry Joachim, 1868-1938’, Proceedings of the British Academy, 24 (1938), pp. 396-422.

The best published source for biographical information about Joachim.

Khatchadourian, Haig 1961, The Coherence Theory of Truth: A Critical Examination (Beirut: American University)

A careful critique of a number of coherence theories of truth, including Joachim’s.

Moore, G.E. (1907), ‘Mr. Joachim’s Nature of Truth’, Mind, n.s. 16 (1907), pp. 229-35.

Reply to The Nature of Truth.

Mure, G.R.G. (1961) ‘F.H. Bradley – Towards a Portrait’, Encounter, 16: pp. 28-35.

Mure, G.R.G. and Schofield, M.J. (2004), ‘Joachim, Harold Henry (1868-1938)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press).

Rabin, Paul (1997), ‘Harold Henry Joachim (1868-1938)’, presented at the Anglo-Idealism Conference, Oxford, July 1997.

A good compilation of biographical information about Joachim from various sources; unfortunately never published.

Russell, Bertrand (1906), ‘What is Truth?’, The Independent Review (June, 1906), pp. 349-53.

Review of Joachim’s The Nature of Truth.

Russell, Bertrand (1906a), ‘The Nature of Truth’, Mind, 15 (1906), pp. 528-33.

Reply to Joachim’s criticisms of Russell’s early identity theory of truth.

Russell, Bertrand, (1907) ‘The Monistic Theory of Truth’ in Russell’s Philosophical Essays (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1968; 1st edn. 1910), pp. 131-46.

The most important critique of Joachim’s coherence theory of truth.

Russell, Bertrand (1920), ‘The Wisdom of our Ancestors’, The Collected Papers of Bertrand Russell, vol. 9, Essays on Language, Mind and Matter, 1919-26, edited by John G. Slater (London: Unwin Hyman, 1988), pp. 403-6.

Review of Joachim’s inaugural lecture.

Vander Veer, Garrett L. 1970, Bradley’s Metaphysics and the Self (New Haven: Yale University Press), pp. 81-90.

An unusual discussion of Joachim as a critic of Bradley, based on the final pages of Logical Studies.

Walker, Ralph (2000), ‘Joachim on the Nature of Truth’ in W.J. Mander (ed.), Anglo-American Idealism, 1865-1927 (Westport, Ct.: Greenwood Press, 2000), pp. 183-97.

One of the few recent articles on Joachim’s coherence theory of truth.

Author Information

Nicholas Griffin

Email: [email protected]

McMaster University

Canada