Langages planifiés entre fantasme et réalité

Auteur: Sara Salis

Date MS: 09-01-2017

Date FL: 12-01-2017

Numéro FL: FL-00004B-00

Citation: Salis, Sara. 2017. “Lingue pianificate tra fantasia

e realtà.” FL-00004B-00, Fiat Lingua,

2017.

droits d'auteur: © 2017 Sara Salis. Ce travail est sous licence

une attribution Creative Commons - Pas d'utilisation commerciale-

Aucun dérivé 3.0 Licence non transférée.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

Fiat Lingua est produit et maintenu par la Language Creation Society (LCS). Pour plus d'informations

à propos du LCS, visitez http://www.conlang.org/

SCUOLA SUPERIORE PER MEDIATORI LINGUISTICI

“ADRIANO MACAGNO”

Legalmente riconosciuta dal Ministero dell’Università e della Ricerca Scientifica

DD.DD. del 30 settembre 2005 e del 27 ottobre 2009

TESI DI DIPLOMA

DEPUIS

MEDIATORE LINGUISTICO

Equipollente ai Diplomi di Laurea rilasciati dalle Università al termine dei corsi

afferenti alla classe delle

LAUREE UNIVERSITARIE

DANS

MEDIAZIONE LINGUISTICA

Langages planifiés entre fantasme et réalité

RELATORE

Lingua Italiana

Prof. ssa Gonnet Anny Maria

RELATORE

Lingua Inglese

Prof. ssa Daly Sabrina

CANDIDATO

Salis Sara

Matr. est. 2014/P070

ANNO ACCADEMICO 2016-2017

Ringraziamenti

Ringrazio innanzitutto i miei genitori, che mi hanno sempre sostenuta e mi hanno

dato la possibilità di frequentare questa università.

Ringrazio tutti coloro che hanno creduto in me, in particolar modo la mia relatrice,

la professoressa Anny Gonnet, che fin dal primo giorno si è impegnata per rendere

questa tesi un progetto di cui vado molto fiera.

Ringrazio Guida, che ha gentilmente accettato di leggere la mia traduzione in

Anglais, insieme alla professoressa Daly.

Ringrazio le amiche conosciute durante questo percorso, che hanno condiviso con

me gioie e dolori dell’università, sessione dopo sessione. En particulier, un grazie a

Jessica che si è rivelata un’amica preziosa, sempre presente e pronta a sostenermi

in tutto.

Un ringraziamento speciale va infine a Emanuele, per essere stato sempre

cadeau, per avermi spronata durante il cammino e per avermi sostenuta nei

momenti più difficili.

Indice

Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………7

Capitolo 1. Lingue pianificate e lingue naturali …………………………………………………………………………….. 11

1.1 Definizioni ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 11

1.2 Lingue pianificate e lingue naturali: confronti ……………………………………………………..15

1.3 Lingue pianificate: classificazione …………………………………………………………………………………. 21

Capitolo 2. Nascita di una lingua …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 27

2.1 Processo di nascita e sviluppo di una lingua naturale …………………………………. 27

2.2 Processo di creazione e sviluppo di una lingua pianificata ……………………… 31

2.2.1 Una lingua pianificata per il mondo reale (esperanto) ……………………………….. 33

2.2.2 Una lingua pianificata per la finzione letteraria (alto valyriano)…………. 37

2.2.3 Confronto tra i due processi ……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 42

Capitolo 3. L’alto valyriano e il latino ………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 45

3.1 Evoluzione delle due lingue ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 45

3.1.1 Dal latino alle lingue romanze ………………………………………………………………………………………….. 47

3.1.2. Dall’alto valyriano al basso valyriano …………………………………………………………………………. 55

3.2 Analogie e differenze tra latino e alto valyriano ……………………………………………….. 61

Conclusione ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 73

Bibliografia ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 77

Appendice A ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 81

Introduction

“Nyke Daenerys Jelmāzmo hen Targārio Lentrot, hen Valyrio Uēpo ānogār iksan.

Valyrio muño ēngos ñuhys issa“. L’idea per questa tesi è scaturita da questa frase in

alto valyriano pronunciata da Daenerys Targaryen, personaggio di una delle più

famose serie televisive degli ultimi anni: Il Trono di Spade. La regina esiliata si

esprime in una lingua inventata, che non viene parlata in nessuna parte del mondo;

eppure,

ascoltando questa e molte altre frasi,

il suo sembra un idioma

estremamente reale, con suoni, grammatica, vocabolario e sintassi specifici.

Dopo aver studiato il modo in cui nascono le lingue e come i fenomeni sociali

influenzino profondamente i fenomeni linguistici, una domanda è sorta spontanea:

se una lingua richiede secoli per formarsi ed è così dipendente da elementi come la

cultura, la storia e la società, com’è possibile creare una lingua dal nulla?

Questo pensiero mi ha incuriosita a tal punto che ho iniziato a documentarmi,

trovando informazioni ancora più interessanti di quanto pensassi. Ho scoperto un

mondo quasi totalmente sconosciuto e più facevo ricerche, più i risultati mi

incuriosivano e creavano altre domande, finché ho ritenuto che potesse essere un

discorso abbastanza importante da poter essere trattato in sede di esame di laurea.

Ho iniziato a questo punto la ricerca di materiale specifico per poter scrivere una

tesi e la risposta alla mia domanda iniziale si è rivelata molto articolata. En fait,

prima di procedere spiegando il processo di creazione di una lingua pianificata,

sarà opportuno fare chiarezza riguardo alla terminologia corretta da utilizzare

nell’ambito delle lingue inventate.

Nel primo capitolo saranno proposte quindi varie definizioni e verranno presentate

le caratteristiche generali delle lingue, per capire se esse siano condivise sia dalle

lingue naturali sia da quelle inventate. Durante la ricerca di materiale, Toutefois,

sono sorte altre domande: per esempio, le lingue inventate sono tutte relegate

all’ambito letterario? Per poter rispondere, sarà riportata una classificazione delle

varie lingue inventate esistenti, in modo da avere una visione più completa

sull’argomento.

È nel secondo capitolo che sarà presentata la risposta alla domanda iniziale,

7

passando all’analisi del processo di creazione di una lingua inventata e

differenziandolo dal processo di nascita di una naturale. L’enfasi sarà posta, dans

particolare, su due lingue artificiali: l’esperanto, una Lingua Ausiliaria

Internazionale (LAI), e l’alto valyriano. Come si avrà modo di leggere nel corso del

capitolo, questi due idiomi sono nati per raggiungere due scopi diversi. Il primo,

creato dal dottor Zamenhof, ha come obiettivo quello di fungere da ponte tra

parlanti di varie lingue europee; questo offre loro la possibilità di comunicare in

una lingua piuttosto semplice e immediata senza dover ricorrere, per esempio,

all’inglese. Il secondo, creato da David J. Peterson, è invece nato con lo scopo di

dare voce a una popolazione immaginaria, senza che si noti, Toutefois, che si tratta di

una lingua inventata. Ho scelto di concentrarmi solo su queste due lingue perché si

può dire che siano una l’opposto dell’altra, sia per lo scopo sia per il metodo di

creazione. Ritengo che, per questo motivo, esse offrano spunti molto interessanti

su cui lavorare.

Nel terzo e ultimo capitolo, si cercherà infine la risposta a un’ulteriore domanda:

una lingua artificiale può essere considerata parimenti dignitosa quanto una

naturale? Si nota una certa semplicità innaturale, dovuta al fatto che quella data

lingua è stata creata anziché essersi sviluppata naturalmente? A tal proposito

verranno confrontate tra loro una lingua naturale tra le più importanti al mondo, il

latino, e la recente lingua che ha dato voce a Daenerys Targaryen, le Haut Valyrien.

Non solo saranno confrontate la grammatica, la fonologia e la morfologia, maman

saranno presi in considerazione anche tutti gli elementi esterni che concorrono a

influenzare una lingua, come la cultura o la storia del popolo. Ho scelto di

confrontare il valyriano con il latino innanzitutto perché le due lingue sono state

messe a confronto più volte nel passato; aussi, dopo qualche ricerca, ho trovato

parecchi punti in comune tra le due tanto da decidere di analizzarli più

accuratamente per verificare la loro veridicità. Enfin, ritengo che se il valyriano

risulterà simile al latino, una delle lingue più importanti e influenti al mondo, donc

questo lo collocherà indubbiamente sul medesimo piano rispetto a una qualunque

lingua naturale. passando all’analisi del processo di creazione di una lingua

inventata e differenziandolo dal processo di nascita di una naturale. L’enfasi sarà

posta, in particolare, su due lingue artificiali: l’esperanto, una Lingua Ausiliaria

8

Internazionale (LAI), e l’alto valyriano. Come si avrà modo di leggere nel corso del

capitolo, questi due idiomi sono nati per raggiungere due scopi diversi. Il primo,

creato dal dottor Zamenhof, ha come obiettivo quello di fungere da ponte tra

parlanti di varie lingue europee; questo offre loro la possibilità di comunicare in

una lingua piuttosto semplice e immediata senza dover ricorrere, per esempio,

all’inglese. Il secondo, creato da David J. Peterson, è invece nato con lo scopo di

dare voce a una popolazione immaginaria, senza che si noti, Toutefois, che si tratta di

una lingua inventata. Ho scelto di concentrarmi solo su queste due lingue perché si

può dire che siano una l’opposto dell’altra, sia per lo scopo sia per il metodo di

creazione. Ritengo che, per questo motivo, esse offrano spunti molto interessanti

su cui lavorare.

Nel terzo e ultimo capitolo, si cercherà infine la risposta a un’ulteriore domanda:

una lingua artificiale può essere considerata parimenti dignitosa quanto una

naturale? Si nota una certa semplicità innaturale, dovuta al fatto che quella data

lingua è stata creata anziché essersi sviluppata naturalmente? A tal proposito

verranno confrontate tra loro una lingua naturale tra le più importanti al mondo, il

latino, e la recente lingua che ha dato voce a Daenerys Targaryen, le Haut Valyrien.

Non solo saranno confrontate la grammatica, la fonologia e la morfologia, maman

saranno presi in considerazione anche tutti gli elementi esterni che concorrono a

influenzare una lingua, come la cultura o la storia del popolo. Ho scelto di

confrontare il valyriano con il latino innanzitutto perché le due lingue sono state

messe a confronto più volte nel passato; aussi, dopo qualche ricerca, ho trovato

parecchi punti in comune tra le due tanto da decidere di analizzarli più

accuratamente per verificare la loro veridicità. Enfin, ritengo che se il valyriano

risulterà simile al latino, una delle lingue più importanti e influenti al mondo, donc

questo lo collocherà indubbiamente sul medesimo piano rispetto a una qualunque

lingua naturale.

9

CAPITOLO 1

Lingue pianificate e lingue naturali

1.1 Definizioni

“Le lingue: insiemi, patrimoni di parole e regole d’uso propri di singole comunità

storiche in determinati periodi”: questa è la definizione data da Tullio De Mauro

(1988/1982, p. 8). L’autore si riferisce ovviamente agli idiomi parlati sulla Terra, il

che forse rende la definizione imprecisa; en fait, anche l’elfico di John Ronald Reuel

Tolkien potrebbe essere considerato una lingua vera e propria. Gli Elfi, nel mondo

fantastico creato dall’autore, sono a tutti gli effetti una comunità storica vivente in

un determinato periodo che si esprime mediante segni linguistici propri.

L’elfico di Tolkien è forse una delle lingue inventate più conosciute al mondo ma ce

ne sono moltissime altre che si potrebbero prendere in considerazione, come la

lingua kēlen, creata da Sylvia Sotomayor per motivi letterari nel 1980; si tratta di

una lingua caratterizzata dall’assenza di verbi e parlata dai Kēleni, popolazione

umanoide del pianeta Tērjemar. Un altro esempio è la lingua ayeri, progetto di

lingua pianificata di Carsten Becker che nell’anno 2003 ha cominciato, per motivi

puramente ludici, a dedicarsi alla codificazione di un linguaggio inventato. Anche il

klingon, ideato da Mark Okrand per Star Trek, è un esempio appropriato e ne

esistono molti altri ancora.

Un’altra lingua inventata, molto recente, è l’alto valyriano, pianificato insieme al

dothraki dal linguista David J. Peterson per la serie televisiva Il Trono di Spade,

basata sui libri dello scrittore americano George R.R. Martin Le Cronache del

Ghiaccio e del Fuoco.

Come l’elfico, l’alto valyriano è una lingua che non appartiene al nostro mondo ma

che viene parlata e scritta a Essos, il Continente Orientale nel quale si svolge parte

11

della storia raccontata della serie televisiva. Le differenze tra le lingue citate sopra

e quelle parlate sulla Terra, dette naturali, sono molteplici; ciò che differenzia

maggiormente le une dalle altre è chiaramente la loro origine in quanto essa

determina il loro futuro sviluppo. Le lingue pianificate sono frutto di un atto di

creazione consapevole e condividono quindi caratteristiche simili tra loro; Toutefois,

esse non sono soggette a continue variazioni grazie all’opera dei parlanti, viens

succede per le lingue naturali. Queste ultime, en fait, subiscono varie evoluzioni nel

corso del tempo, fino a divenire come le conosciamo oggi. Si intende quindi per

lingua naturale una qualunque lingua esistente al mondo che sia nata

spontaneamente e abbia subito fasi di evoluzione perché soggetta a variazioni e

mutamenti, vale a dire qualsiasi lingua parlata (Peterson, 2015). Silvia Luraghi

(2006/2013) puntualizza inoltre che essa deve essersi sviluppata in una comunità

di parlanti, essere trasmessa tra le generazioni, essere appresa quindi come lingua

materna, di prima socializzazione, dai nuovi parlanti.

Tornando alla definizione di lingua, per considerare dunque l’elfico, le Haut Valyrien

o il dothraki come lingue, potremmo parlarne in senso lato come di un complesso

sistema di comunicazione.

La comunicazione verbale umana avviene

correttamente nel momento in cui l’emittente che lancia il messaggio linguistico e il

ricevente che lo interpreta condividono un codice, grazie al quale è possibile

attribuire un significato alla realtà.

Per codice s’intende dunque […] l’insieme di corrispondenze, fissatesi per

convenzione fra qualcosa (insieme manifestante) e qualcos’altro (insieme

manifestato) che fornisce le regole d’interpretazione dei segni. Tutti i

sistemi di comunicazione sono dei codici […]. I segni linguistici

costituiscono il codice lingua (Berruto & Cerruti, 2011, p. 7).

È necessario specificare che esistono vari tipi di codice con caratteristiche che li

rendono estremamente diversi tra loro. Per esempio una lingua come l’italiano è

diversa dal linguaggio matematico, pur essendo entrambi codici; l’italiano è dotato

en fait, come tutte le lingue, di proprietà specifiche quali l’onnipotenza semantica,

la plurifunzionalità e la riflessività. L’onnipotenza semantica indica la capacità della

lingua di esprimere qualsiasi contenuto; con plurifunzionalità s’intende la

possibilità di adempiere a molte funzioni diverse; la riflessività, o funzione

12

metalinguistica, è infine la capacità della lingua di riflettere su se stessa. Inoltre il

codice linguistico è vivo e in continuo divenire varia nella dimensione diacronica a

opera dei parlanti, che ne possono modificare le regole. Le regole del codice

matematico, Plutôt, non sono modificabili. L’uso di un codice linguistico è creativo,

l’uso del codice matematico non lo può essere; il parlante è colui che garantisce la

vitalità di un codice linguistico e contribuisce a creare e mantenere le varianti

oppure a decretarne l’abbandono. Colui che usa il codice matematico ne condivide

le regole, ma non può modificarle.

Un altro termine utilizzabile per definire le lingue è quello di “lingue reali”, Que

comprende sia quelle naturali sia quelle pianificate, in quanto entrambe esistono e

sono nate o sono state create nel nostro mondo. Toutefois, per non focalizzare

l’attenzione esclusivamente sull’esistenza reale o meno di una lingua, occorre

sottolineare che storia ed evoluzione di un idioma nato naturalmente e parlato da

secoli sono diverse da quelle di un idioma che è stato creato artificialmente. L’alto

Valyriano, essendo una finzione, non ha subito i vari mutamenti come di solito

accade con le lingue naturali; esse sono infatti soggette a molti cambiamenti nel

corso del tempo (mutamento diacronico), tanto che, evoluzione dopo evoluzione,

ne possono anche nascere di nuove (basti pensare al passaggio dal latino alle

lingue romanze).

Per definire dunque in modo preciso un idioma come l’alto valyriano,

differenziandolo però da quelli del nostro mondo, occorre scegliere il modo

migliore, tra le varie proposte che troviamo in letteratura, con il quale possiamo

riferirci a esso.

A tale proposito, le tre che paiono essere più interessanti sono le seguenti:

Lingua pianificata: “Sistema linguistico completo definito per iscritto da un pia-

nificatore linguistico, detto glottoteta, per i fini più diversi”, come la definisce

Gobbo (2009, p. 70);

Lingua artificiale: “Lingua costruita consciamente per mezzo di una serie di con-

venzioni sia nelle regole che nel lessico”, come viene definita in Aga Magéra Di-

fúra (Albani & Buonarroti, 1994/2011, p. 46);

Lingua immaginaria: “Sistema di segni, spesso non codificati, appartenente ad

una comunità o popolo inesistenti, elaborato per fini non pratici, ma puramente

13

ludico-espressivi” (Albani & Buonarroti, 1994/2011, p. 194).

Ciascuna di queste definizioni è importante, poiché ci fornisce informazioni

diverse; la prima, oltre a specificare il concetto di lingua pianificata, introduce la

figura del glottoteta, diverso dal linguista in quanto quest’ultimo non crea le lingue,

bensì le studia scientificamente. Non necessariamente un glottoteta si occupa di

linguistica a livello professionale; alcune Lingue Ausiliarie Internazionali (Que

saranno trattate più avanti) sono infatti state create da glottoteti che erano medici,

ingegneri, matematici o sacerdoti. La definizione specifica, aussi, che una lingua

può essere creata per diversi fini, siano essi filosofici, di gioco, religiosi, letterari,

linguistici o scientifici; dans le cas du Haut Valyrien, il fine è letterario.

La seconda definizione permette di distinguere le lingue artificiali da quelle

naturali in quanto queste ultime, come specificato in precedenza, sono frutto di

un’evoluzione; le convenzioni non sono quindi stabilite consapevolmente da

qualcuno, mentre per gli idiomi artificiali è compito del creatore, o dei creatori,

elaborare consciamente queste convenzioni.

La terza infine spiega che una lingua immaginaria, creata esclusivamente per un

fine ludico, appartiene a una comunità anch’essa immaginaria.

Tra le tre denominazioni, pur essendo tutte condivisibili, quella di “pianificata” è la

più adeguata in quanto descrive in modo esauriente tutte le caratteristiche

fondamentali di questo tipo di lingue. Per questo motivo è quella che verrà

utilizzata in questa trattazione, imitando la scelta di Federico Gobbo (2009, p. 70) il

quale ritiene che questa sia la terminologia più adatta nonostante esistano appunto

varie denominazioni.

Finora l’attenzione è stata posta unicamente sulle lingue pianificate appartenenti a

comunità inesistenti, i cui creatori hanno perseguito un fine letterario. Toutefois,

secondo la definizione di lingua pianificata, è possibile che un glottoteta si ponga

come fine quello linguistico. Esistono infatti idiomi pianificati creati per essere

parlati e scritti in questo mondo da comunità esistenti, chiamati Lingue Ausiliarie

Internazionali (LAI), cioè “lingue per facilitare le relazioni scritte e orali tra

persone di lingue materne diverse” (Albani & Buonarroti, 1994/2011, p. 49)

oppure LIA, come preferisce definirle Umberto Eco.

Una LAI deve soddisfare determinate esigenze: innanzitutto non deve essere una

14

delle lingue nazionali già esistenti poiché, se così fosse, si favorirebbero i parlanti

della stessa. Essa deve essere, al contrario, il più neutra possibile, come afferma

Umberto Eco (1996/2006), riferendosi ai progetti di Lingue Internazionali

Ausiliarie fioriti agli inizi del XX secolo: "[…] analoga a quelle naturali, maman […]

sentita come neutra da tutti i propri utenti” (p.342). Non deve neanche essere una

lingua morta come il latino, nonostante ci sia stato un tentativo, fallito, di riportarlo

in vita con qualche modifica. Questo progetto ha il nome di Latino sine Flexione ed è

stato portato avanti dal matematico Giuseppe Peano, nel 1903, il quale lo

proponeva come lingua esclusivamente scritta e per la comunicazione scientifica,

come afferma Federico Gobbo (2009). Si trattava, come ricorda Umberto Eco

(1996/2006), di un latino semplificato, privo di declinazioni, per cui “[…] come per

altre lingue internazionali, […] vale la prova del consenso delle genti: il Latino sine

flexione non si è diffuso e rimane […] come mero reperto storico” (p. 348). Un autre

esigenza di una LAI è quella di “essere capace di servire alle relazioni abituali della

vita sociale, agli scambi commerciali e ai rapporti scientifici e filosofici” (Albani &

Buonarroti, 1994/2011, p. 49). Enfin, essa deve “essere di facile acquisizione per

tutte le persone d’istruzione elementare media e in particolare per le persone di

civilizzazione europea” (p. 49). Questa esigenza ha causato vari problemi per

quanto riguarda molti progetti di LAI proposti; è difficile realizzare una lingua di

facile apprendimento per tutti senza favorire una parte dei parlanti e senza

compiere scelte che rischiano di distruggerla. Un esempio è dato da ciò che è

accaduto al volapük, lingua creata dal tedesco Johann Martin Schleyer. Egli aveva

preso l’inglese come modello su cui basare la propria lingua pianificata; Toutefois,

per rendere l’apprendimento più semplice ai cinesi, aveva deciso di rimuovere la

“r” perché per loro tale lettera sarebbe stata molto difficile da pronunciare. Dans

questo modo però la lingua è diventata ardua da capire e apprendere anche per gli

europei, dunque il progetto non si è ulteriormente sviluppato, come specifica

Federico Gobbo (2009).

1.2 Lingue pianificate e lingue naturali: confronti

Dopo aver fatto chiarezza sulla terminologia più adatta da utilizzare, è bene cercare

di capire se una lingua pianificata possa essere considerata allo stesso livello di una

15

naturale; per fare ciò occorre chiarire se ci sono punti in comune tra loro.

Una prima differenza è già stata individuata in precedenza: l’origine. Mentre le

lingue naturali sono frutto di un processo di evoluzione della durata di secoli, le

pianificate nascono dall’atto di creazione del loro inventore. La ricerca di

caratteristiche comuni tra i due tipi di lingue, Mais, in questa parte della

traitement, sarà più dettagliata; in particolare verranno esaminate le proprietà

generali delle lingue, ovvero gli attributi che ogni idioma possiede.

Antonio Romano (2010) spiega in che cosa consistano queste proprietà generali;

prima, Mais, fa una breve introduzione nella quale spiega che qualunque sistema

linguistico si prenda in considerazione avrà delle componenti di base che si

potranno ritrovare in tutti gli altri: phonologie, morphologie, sintassi e lessico. ET

importante sottolineare che egli prende in considerazione solo le lingue naturali e

non quelle pianificate: sarà dunque mio compito capire se ciò che lui scrive sia

valido anche per queste ultime.

La prima proprietà che l’autore descrive è la plurifunzionalità linguistica (già

accennata in precedenza), che consiste nella possibilità della lingua di poter essere

utilizzata per parlare di ogni cosa, anche di se stessa (proprietà metalinguistica). Par

quanto riguarda le lingue naturali, la conferma dell’esistenza di questa proprietà

avviene ogni giorno, in quanto i parlanti conversano intorno a vari argomenti e, dans

qualche modo, riescono sempre a esprimere ciò che vogliono dire. È importante

notare che alcuni idiomi sono più precisi di altri: per esempio in inglese troviamo il

verbo to look up del quale, se preso in una certa accezione, in italiano non esiste un

corrispettivo. Tuttavia si può rendere il senso utilizzando la frase “fare una breve

visita a”. Differenze di questo genere si ritrovano anche in altri casi, spesso dovute

all’ambiente circostante e alla cultura del popolo. Prendendo in considerazione due

dialetti italiani, il piemontese e il siciliano, emergeranno infatti varie differenze

linguistiche legate all’ambiente. Piemonte e Sicilia si trovano uno all’estremo nord e

l’altra all’estremo sud dell’Italia, cioè a latitudini molto distanti tra di loro, donc

sono interessati da fenomeni atmosferici molto diversi tra loro. In piemontese ci

sono vari modi di denominare la neve: fioca, per esempio, è un termine che indica la

neve in generale, mentre patarass si riferisce in particolare alla neve tipica degli inizi

16

di marzo. In siciliano non troveremo questa differenza di termini così specifica, maman

sarà più facile incontrare diverse parole per definire il mare.

Per quanto riguarda le lingue pianificate, anch’esse sono caratterizzate da

plurifunzionalità linguistica, qualunque sia lo scopo della loro creazione. Se una

LAI non avesse questa proprietà sarebbe incompleta, dunque non sarebbe utile a

favorire la comunicazione internazionale. Riguardo invece le lingue pianificate per

mondi immaginari, come l’alto valyriano, bisognerà spendere qualche parola in più.

Essendo costruite per popoli inesistenti, che vivono in luoghi inesistenti e con una

cultura inesistente, queste lingue possono sembrare, di primo acchito, incomplete;

nel dothraki, per esempio, manca la parola “grazie”, ma questo non significa che

esso sia davvero incompleto. In siciliano non esiste un termine che indichi “la neve

tipica di marzo”, ma questo dialetto viene comunque considerato completo in

quanto in Sicilia questa parola non è necessaria. Anche al dothraki, donc, non

mancano parole fondamentali alla comunità per esprimersi, perché quelle che

possiede sono sufficienti alla comunicazione tra i parlanti. Nel caso della differenza

prima citata tra piemontese e siciliano, siamo in una situazione legata all’ambiente

e al fatto che i dialetti regionali italiani, pur essendo tutti idiomi romanzi

(neolatini), sono diversi tra loro. Tale diversità è dovuta alla storia linguistica

italiana: essa ha prodotto molte varietà di parlate, la cosiddetta Babele italica,

causata dalle vicende sociali, politiche e culturali della penisola, in cui la realtà e

culture, collegate dalla tradizione latina, sono state però segnate da divisioni e

allontanamenti (Gensini 1988/1992). I dialetti sono lingue parlate a livello locale

da comunità di parlanti che, al di là delle differenze regionali, condividono lo stesso

codice linguistico, quello dell’italiano standard. Per quanto riguarda invece la

differenza tra dothraki e alto valyriano, parliamo di due codici diversi parlati da

due distinte comunità che vivono nello stesso continente e nello stesso arco

temporale, ma che sono costituite da due società diverse caratterizzate da culture

différent. In alto valyriano, per esempio, esiste un termine per ringraziare

(kirimvose). Tale lingua è stata creata per lo stesso mondo fantastico di parlanti

dothraki, con la differenza che il popolo di Valyria ha un livello culturale

estremamente alto, a differenza del popolo dei Signori del Cavallo (altro nome per

indicare il popolo dei dothraki), in quanto la loro cultura ruota interamente attorno

17

a questi animali. Questo si riflette anche sulla lingua; per tradurre, per esempio,

“sono già stata qui” si userà il verbo dothralat, cioè cavalcare, e non essere, per cui

la frase tradotta letteralmente sarà “ho già cavalcato qui”, (anha ray dothra jinne

hatif ajjin). Continuando il ragionamento sulla mancanza di espressioni linguistiche

di cortesia in dothraki, evidentemente ciò è dovuto al fatto che, nella loro rozza

società, non sono previsti né cortesie né ringraziamenti.

Un’altra proprietà delle lingue è l’universalità: come scrive Romano (2010), ciò

significa che “non esiste […] gruppo umano, per quanto piccolo e/o isolato, che non

usi un sistema di comunicazione verbale (orale)” (p. 27). L’autore parla di “gruppi

umani” quindi, nonostante egli si riferisca solo agli uomini viventi sul pianeta Terra,

la sua spiegazione si può perfettamente adattare a qualunque essere umano

vivente in qualunque luogo. I Valyriani, pur essendo un popolo immaginario, Je suis

comunque persone e l’essere persona implica che si utilizzi un sistema di

comunicazione verbale orale, così come l’esistenza di una data lingua implica che

essa sia la forma di espressione di un popolo. Un idioma infatti non avrebbe senso

di esistere se non fosse utilizzato, anche in un mondo immaginario, da un popolo o

da una comunità.

Nel caso in cui uno scrittore volesse inventare una storia fantascientifica

ambientata nello spazio, con degli alieni come protagonisti, potrebbe avvalersi del

fatto che essi non sono umani; donc, potrebbero avere un sistema di

comunicazione diverso. Per esempio, sarebbe plausibile che le loro interazioni

potessero avvenire a un livello puramente mentale. A questo punto un qualsiasi

sistema linguistico orale sarebbe inutile, in quanto per la comunicazione sarebbe

sufficiente la mente, cosa che non può avvenire con gli umani, i quali necessitano di

un codice linguistico condivisibile per esternare i loro pensieri.

Parlando di universalità, l’autore specifica tra parentesi che il sistema di

comunicazione utilizzato dai gruppi umani per esprimersi è orale: perché non

scritto? La risposta porta alla terza proprietà delle lingue, ovvero la priorità del

parlato; en fait, mentre la comunicazione orale è usata da ogni essere umano, ciò

non vale per quella scritta. La veridicità di questa affermazione si può dimostrare

anche solo pensando alla storia. Quando nacque la scrittura gli uomini esistevano

ormai da migliaia di anni, ma ciò non significa che prima della scrittura essi non

18

fossero in grado di comunicare tra loro; semplicemente utilizzavano un sistema

esclusivamente orale o gestuale per interagire.

In questo caso per quanto riguarda le lingue pianificate c’è una differenza in quanto

esse si comportano esattamente al contrario: inizialmente il glottoteta scrive la

struttura della lingua e solo in seguito essa potrà dare voce a una comunità.

Affermando che un idioma può avere sia una versione orale che una scritta, était

individuata un’altra proprietà: la trasponibilità di mezzo, ovvero la possibilità di

trasporre la produzione verbale di ogni sistema linguistico secondo codici scritti e

vice versa. Le regole da rispettare per eseguire quest’operazione variano da lingua a

lingua: in italiano, per esempio, a ogni lettera corrisponde un suono. Viens

affermano G. Berruto e M. Cerruti (2011), alcuni sistemi di scrittura, tra cui quello

italiano, si basano sull’inventario fonematico della lingua stessa e “l’ortografia

dell’italiano […] riproduce le unità fonologiche con una certa fedeltà.

Néanmoins, non mancano casi in cui il rapporto biunivoco tra i suoni e i grafemi

viene a mancare” (p. 54). Succede quindi che esistano dei suoni la cui

rappresentazione grafica in italiano non è prevista (exemples: /e/~ /Ɛ/ , /o/~ /ͻ/) e

che lo stesso grafema serva a rappresentare fonemi diversi (es. “accétta” [aʹtː⨛etːa]

~ “accètta”[aʹtː⨛Ɛtːa]), o che occorrano combinazioni di grafemi per rappresentare

delle opposizioni fonematiche come, per esempio, “ch” e “gh” davanti a “i” ed “e”

(“china” [ʹkiːna] ~ “Cina” [ʹt∫iːna]), oppure che grafemi diversi rappresentino lo

stesso suono come “c”, caro, [ʹkaːro] e “q”, quadro [ʹkwaːdro]. Anche in russo, par

exemple, a ogni lettera corrisponde un suono. Al contrario, ciò non vale per

l’inglese o il francese la cui grafia è piuttosto lontana dalla fonia, per cui i suoni

corrispondono a sequenze di lettere e le lettere non sempre hanno delle

corrispondenze foniche. En conséquence, per tali lingue, le regole da seguire per

pronunciare correttamente le parole sono piuttosto complicate.

Nelle lingue pianificate questa proprietà è scontata in quanto, come già spiegato,

per esse c’è una priorità dello scritto sul parlato e non il contrario, donc

ovviamente una volta scritto l’idioma si potrà iniziare a parlarlo.

Un’altra caratteristica ancora di cui parla Antonio Romano (2010) è il

distanziamento; grazie a questa proprietà è possibile comunicare con altri esseri

19

umani anche intorno a referenti che non sono presenti nello spazio fisico in cui ha

luogo la conversazione o che si svolgono in un tempo cronologicamente lontano dal

momento conversazionale. Per parlare di un albero, non siamo costretti a indicarne

uno in modo da far capire al nostro interlocutore ciò a cui ci stiamo riferendo,

poiché lui sa che la parola “albero” si riferisce a qualcosa di preciso e, al solo

sentirla nominare, nella sua mente prenderà forma la sua idea di albero. Se non

scatta questo meccanismo, vuol dire che l’interlocutore non conosce il significato

della parola; sarà sufficiente spiegargli a che cosa essa si riferisce o fornirgli la

traduzione in una lingua che egli conosce affinché gli sia chiaro il concetto. Tutto

ciò è ovviamente possibile anche con le lingue pianificate: l’unica condizione

necessaria è sapere a che cosa pensare nel momento in cui ascoltiamo un dato

termine. A questo punto vale però la pena fare un breve accenno a un importante

glottologo che ha rivoluzionato la linguistica: Ferdinand de Saussure. È importante

citarlo in questo momento in quanto egli ci fornisce, come ricordano Berruto e

Cerruti (2011), i principi della nuova linguistica, chiamata generale, grazie al Cours

de linguistique générale; si tratta di un’opera postuma in cui i suoi studenti

dell’Università di Ginevra raccolsero, nel 1916, le sue lezioni. A partire da tali

principi, è possibile sottolineare una distinzione che farà più chiarezza sulla

proprietà linguistica del distanziamento.

Come puntualizzano Romano e Miletto (2010), De Saussure afferma che i segni

linguistique (ovvero gli elementi che due interlocutori si scambiano durante una

conversazione) possiedono due facce: il significante e il significato. Il primo è il lato

più materiale, il supporto del messaggio, e può essere vocale (costituito dai suoni

che gli interlocutori emettono), oppure alfabetico (basato sui grafi e sui grafemi). Il

secondo è immateriale e rimanda al concetto che la parola vuole trasmettere. ET

proprio grazie a quest’ultimo che è possibile il distanziamento in quanto le parole,

tramite il loro aspetto fisico (il significante) rimandano a un concetto in particolare

(il significato), dunque possono essere comprese anche senza che l’interlocutore

abbia a portata di mano o sott’occhio il referente designato.

Enfin, un’altra importante proprietà delle lingue è la trasmissibilità culturale:

come affermano Berruto e Cerruti (2011), consiste semplicemente nella capacità

delle comunità umane di trasmettere per tradizione alle generazioni future la

20

propria lingua. Di nuovo, è un discorso applicabile alle “comunità umane”, il che lo

rende quindi valido anche per le lingue pianificate in quanto, seppure in un mondo

fittizio, esse sono parlate da esseri umani tanto quanto le lingue naturali.

1.3 Lingue pianificate: classificazione

Fino a qui sono stati trattati due tipi di lingue pianificate: quelle costruite per scopi

letterari e le LAI, inventate invece con il fine di agevolare le conversazioni

internazionali e il dialogo universale, come ricordano Berruto e Cerruti (2011).

Esistono però anche altri motivi per cui questi idiomi vengono plasmati, a seconda

dei quali essi assumono caratteristiche diverse. Dunque per fare un po’ d’ordine

occorre classificare i vari tipi di lingua pianificata.

Esistono diversi modi per farlo, ognuno dei quali permette di concentrarsi

maggiormente su un aspetto in particolare: adottando per esempio una

classificazione in ordine cronologico, si presterà maggiore attenzione ai vari

contesti storici in cui le lingue in questione sono state sviluppate e alla loro

evoluzione nel tempo. Un’altra classificazione possibile prende in considerazione

gli idiomi a seconda del fine per cui sono stati creati; essendo il tipo di

catalogazione che offre una visione più completa sulle varie tipologie di lingue, Et

dunque quella presentata e analizzata qui di seguito.

Prima però è necessaria una premessa per spiegare la differenza tra lingue

cosiddette a priori, a posteriori e miste, secondo la letteratura (Gobbo, 2009;

Albani & Buonarroti, 1994/2011).

Una lingua a priori è un idioma completamente a sé stante, che viene cioè creato

senza prendere spunto da quelli naturali;

Una lingua a posteriori è esattamente l’opposto, ovvero è un idioma che viene

pianificato basandosi su fonologia, grammatica, sintassi e/o altre caratteristiche

di una lingua naturale;

Una lingua mista è un idioma pianificato che si ricava in parte basandosi su uno

naturale, in parte creandolo dal nulla.

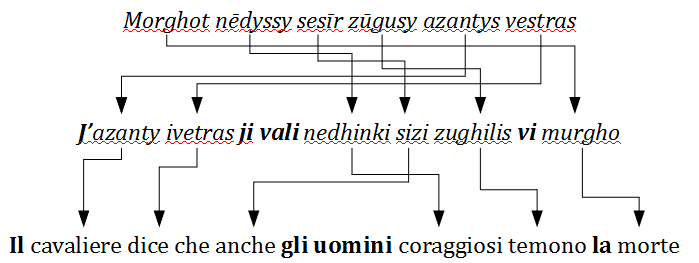

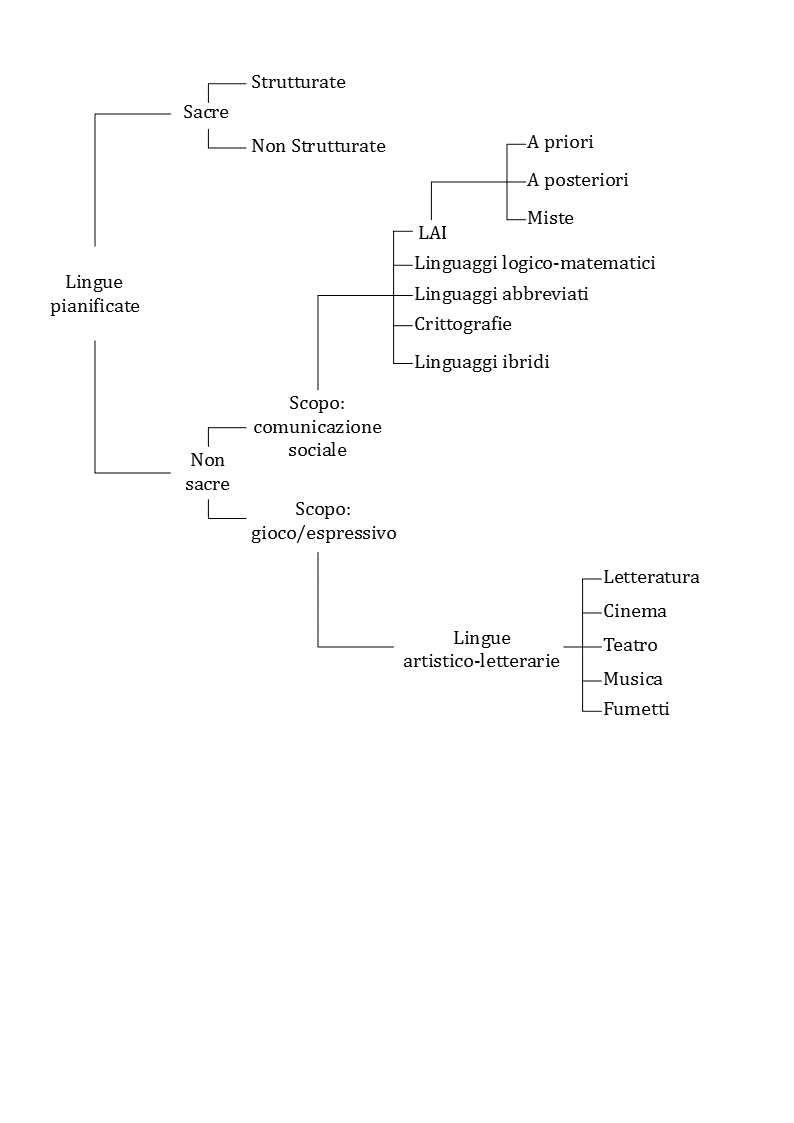

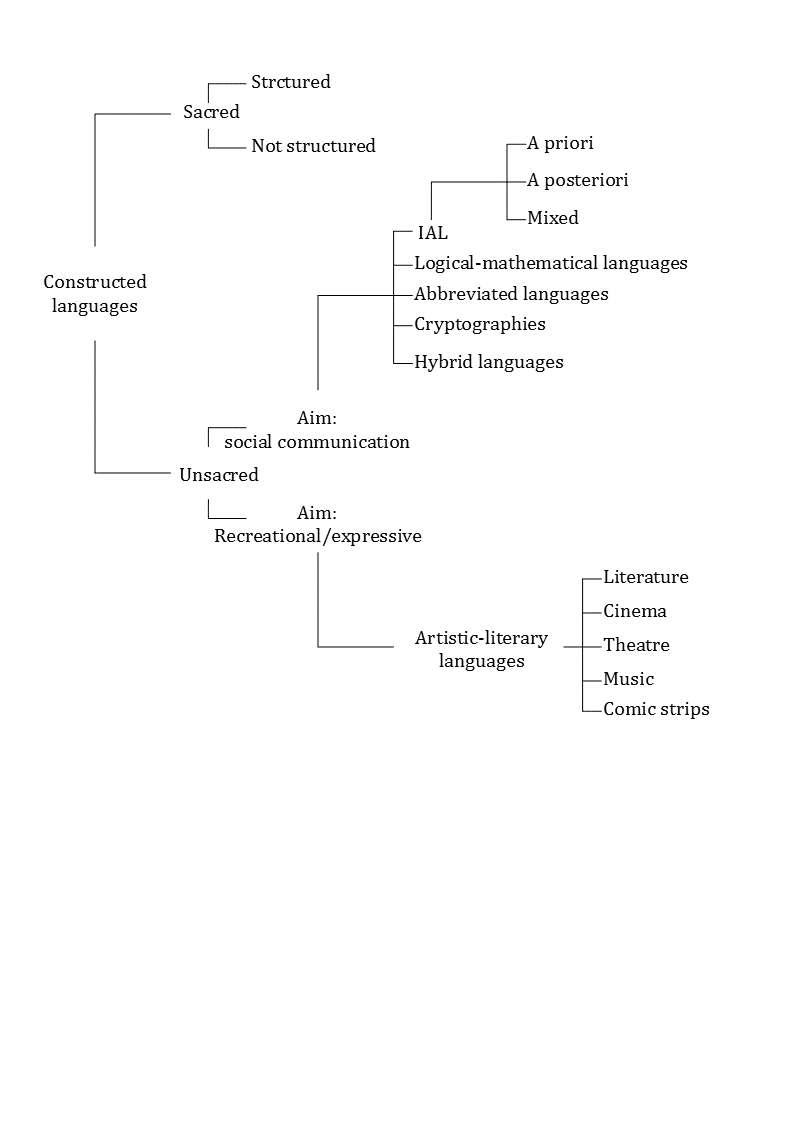

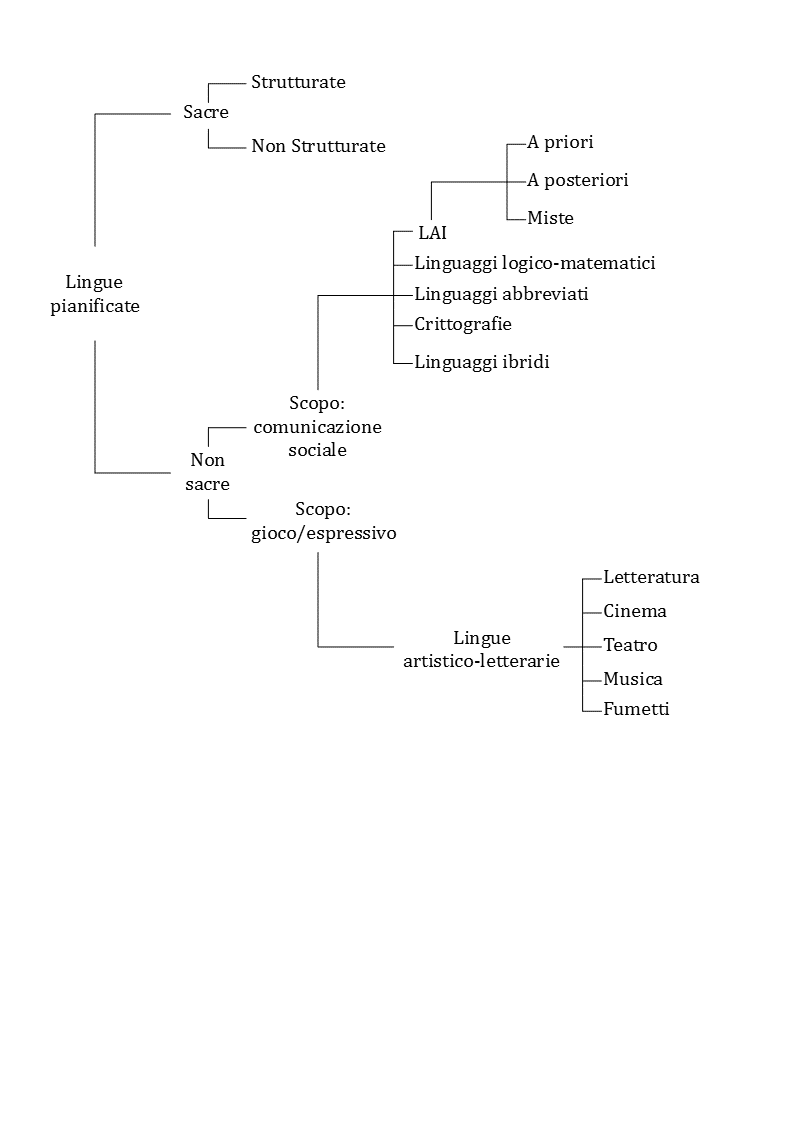

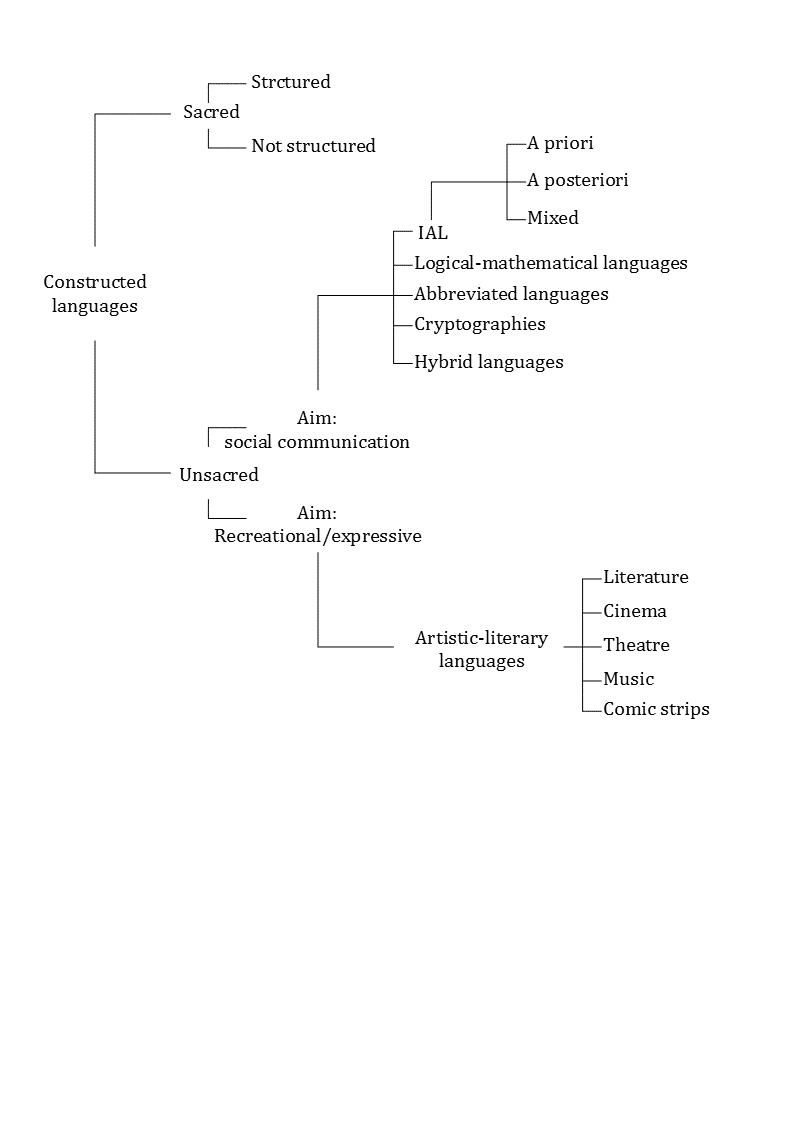

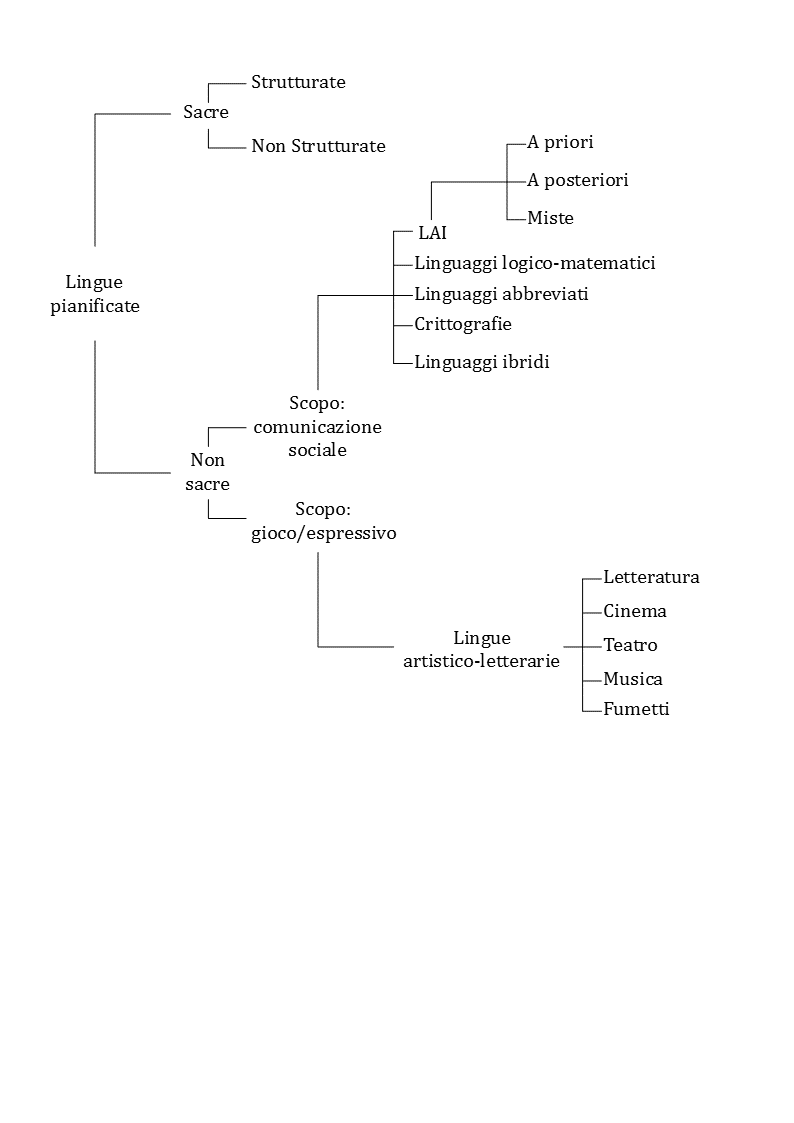

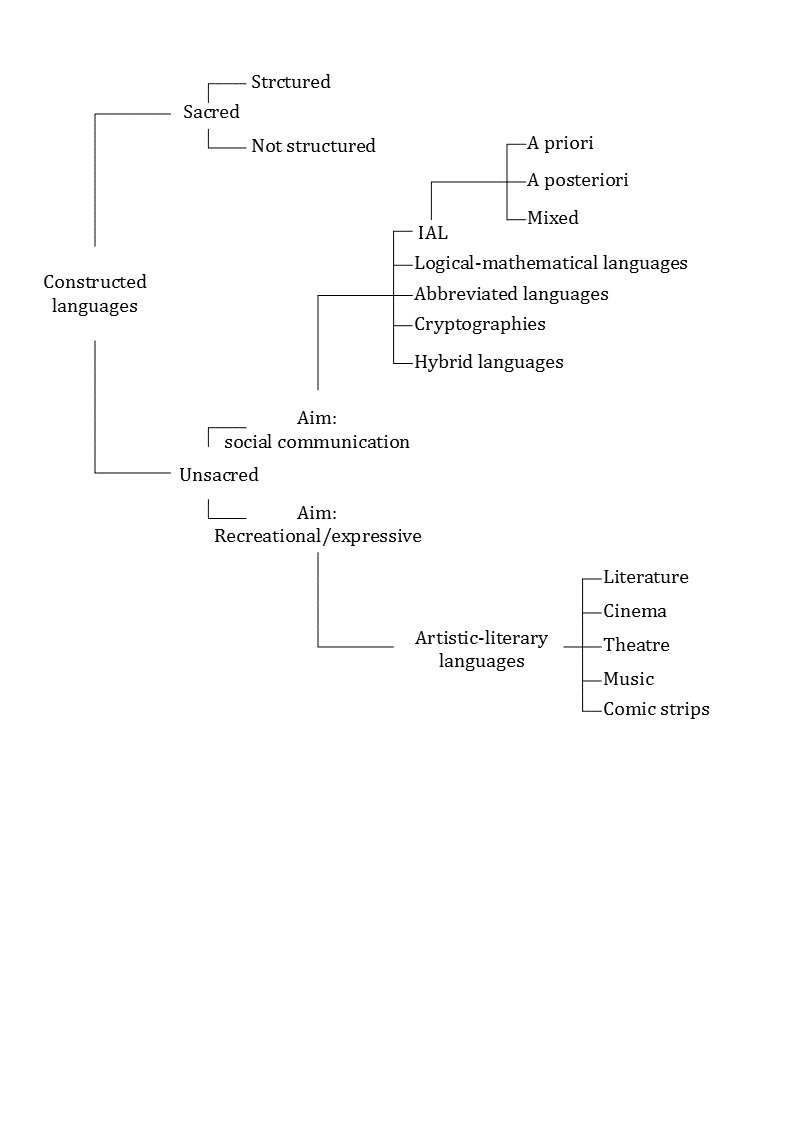

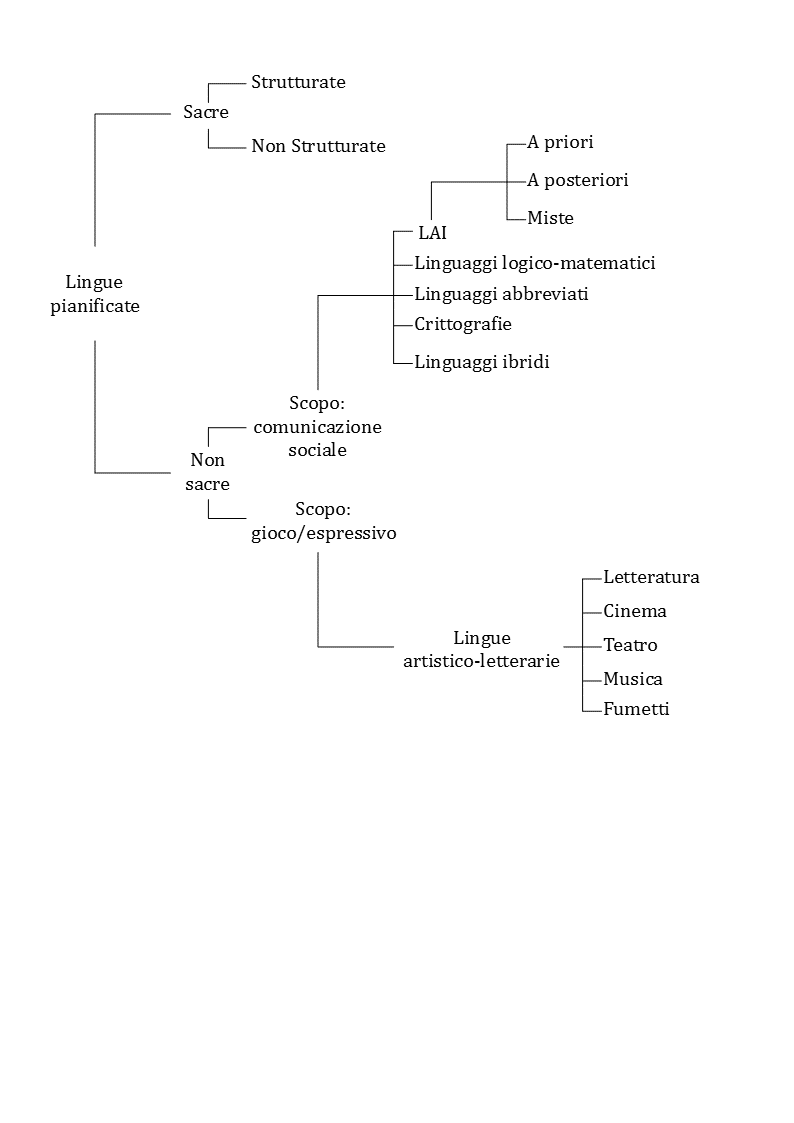

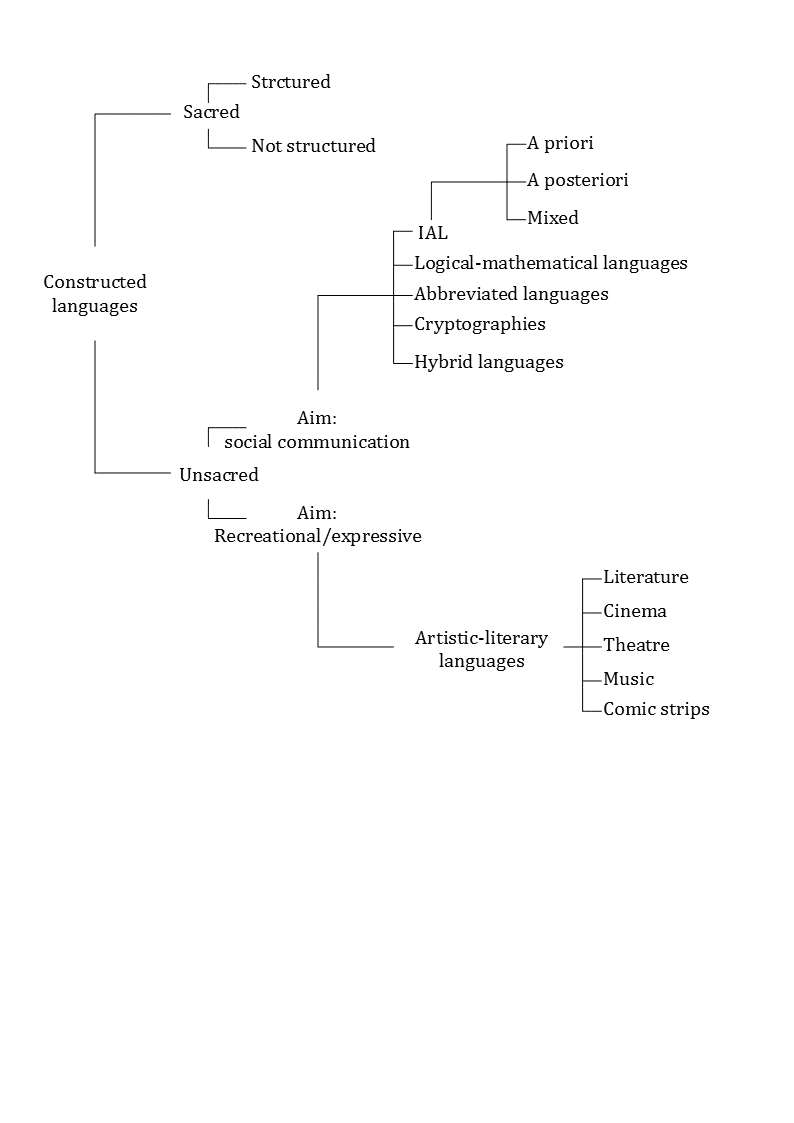

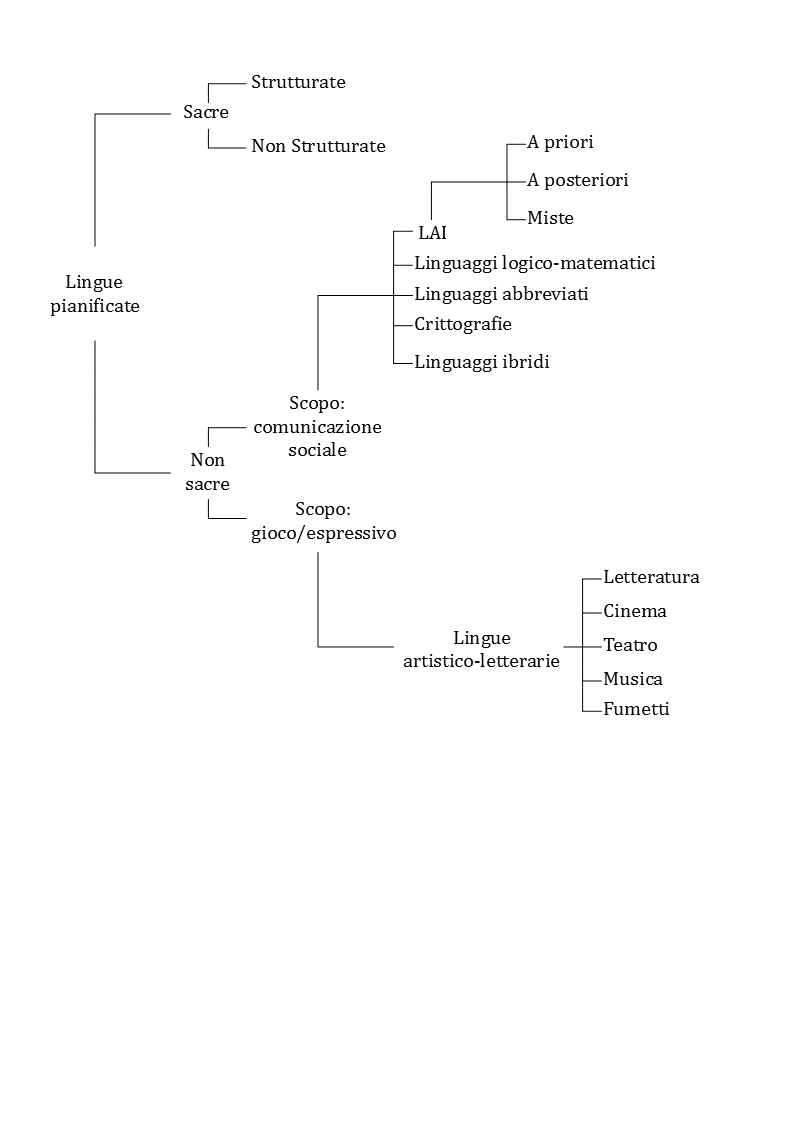

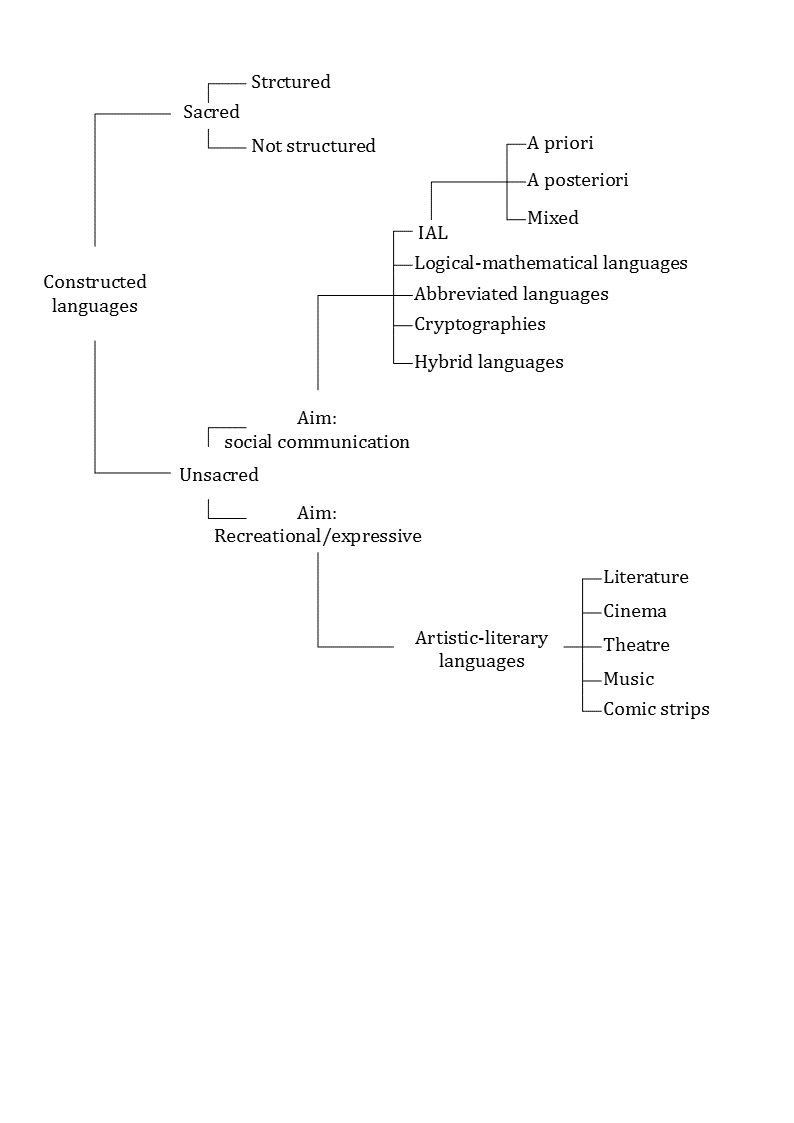

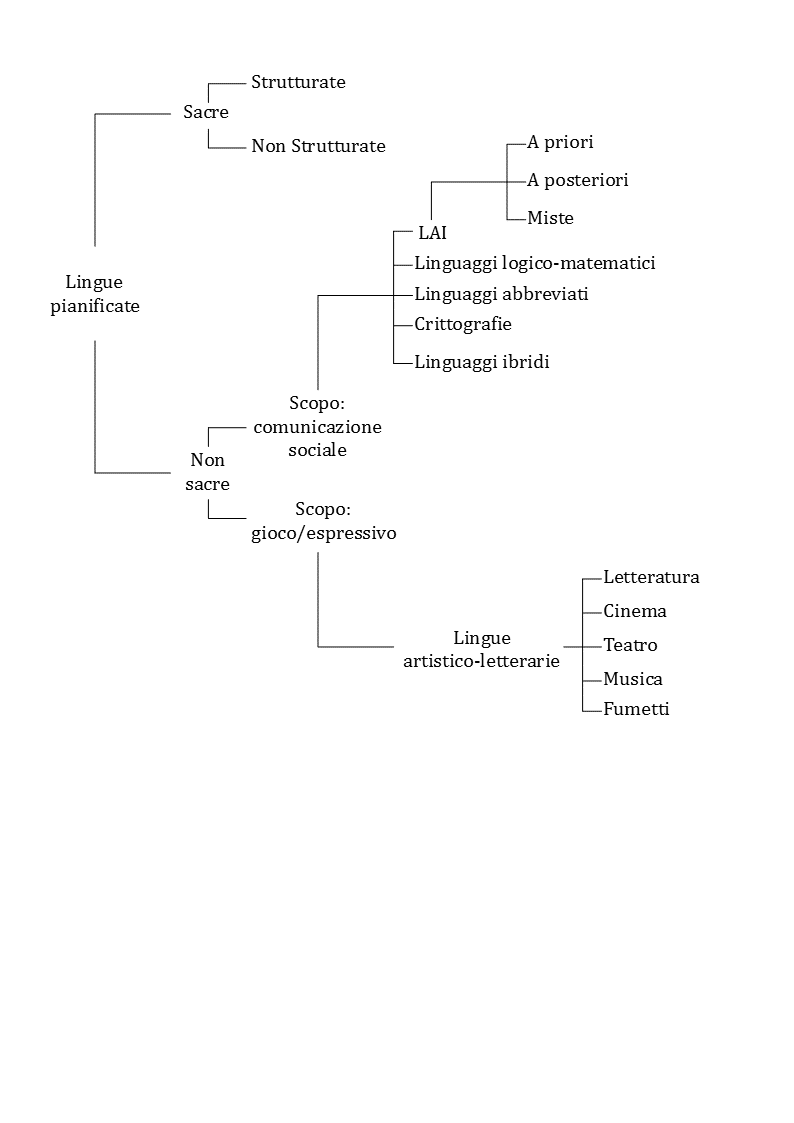

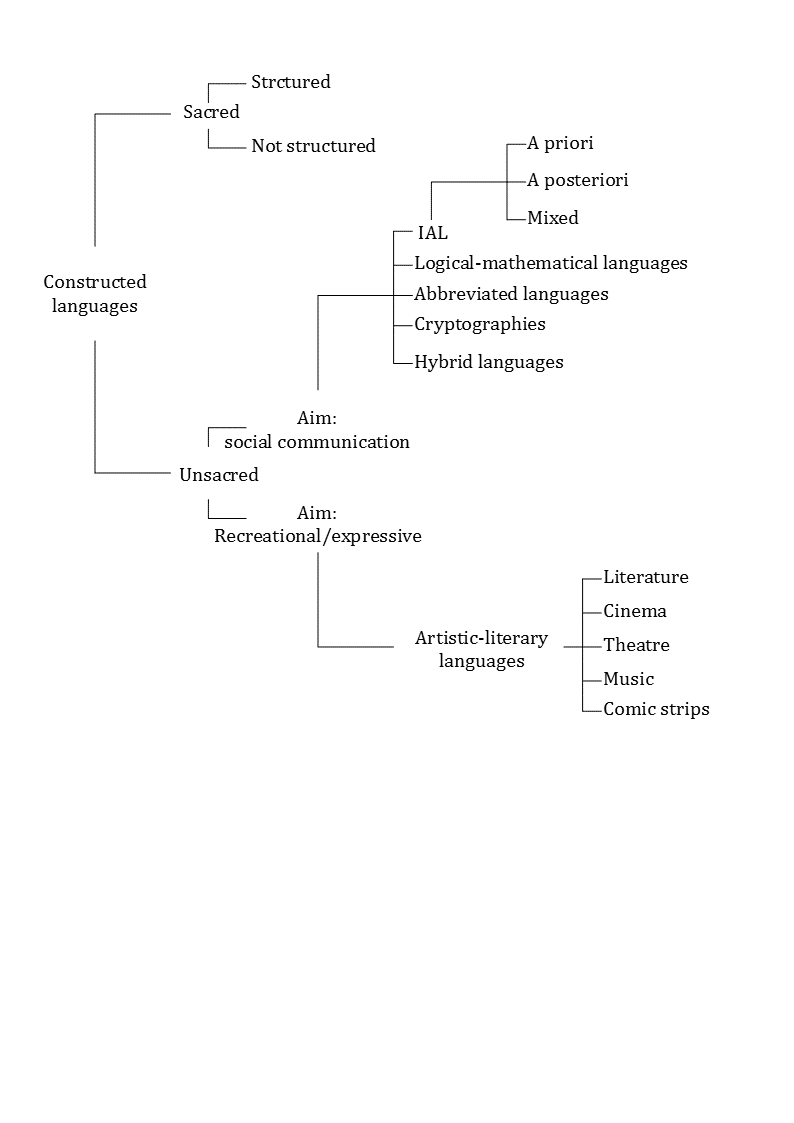

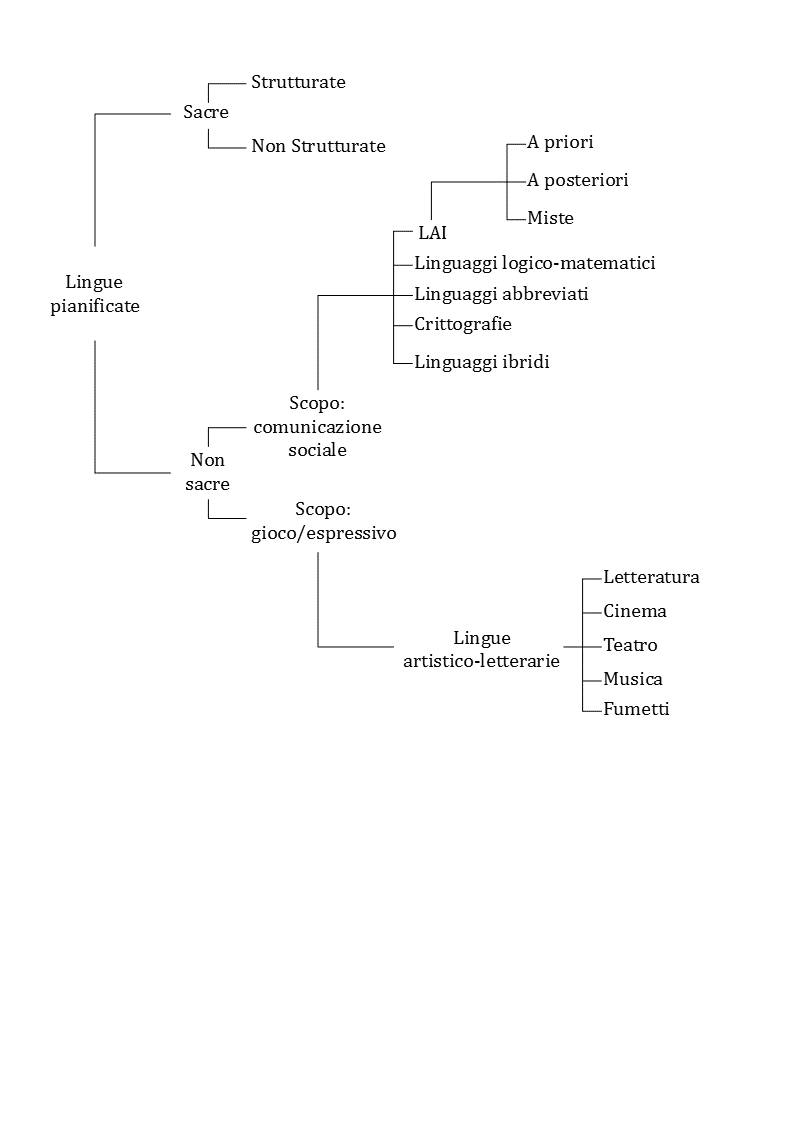

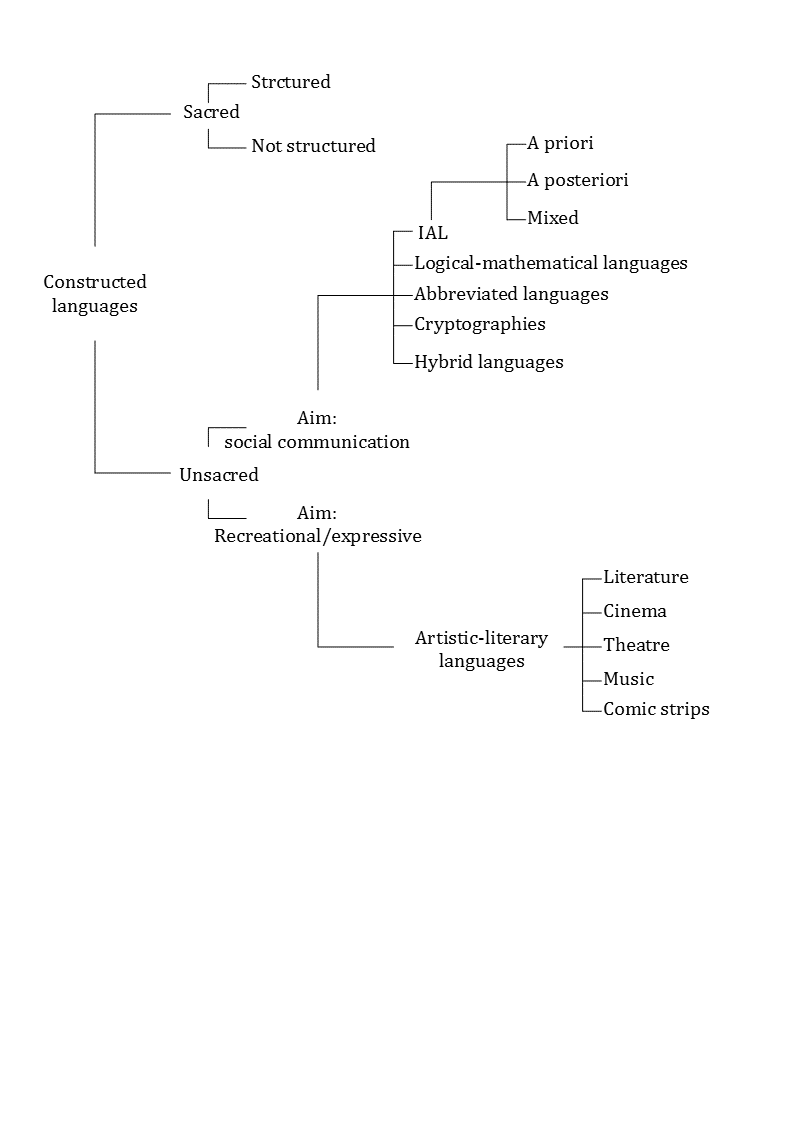

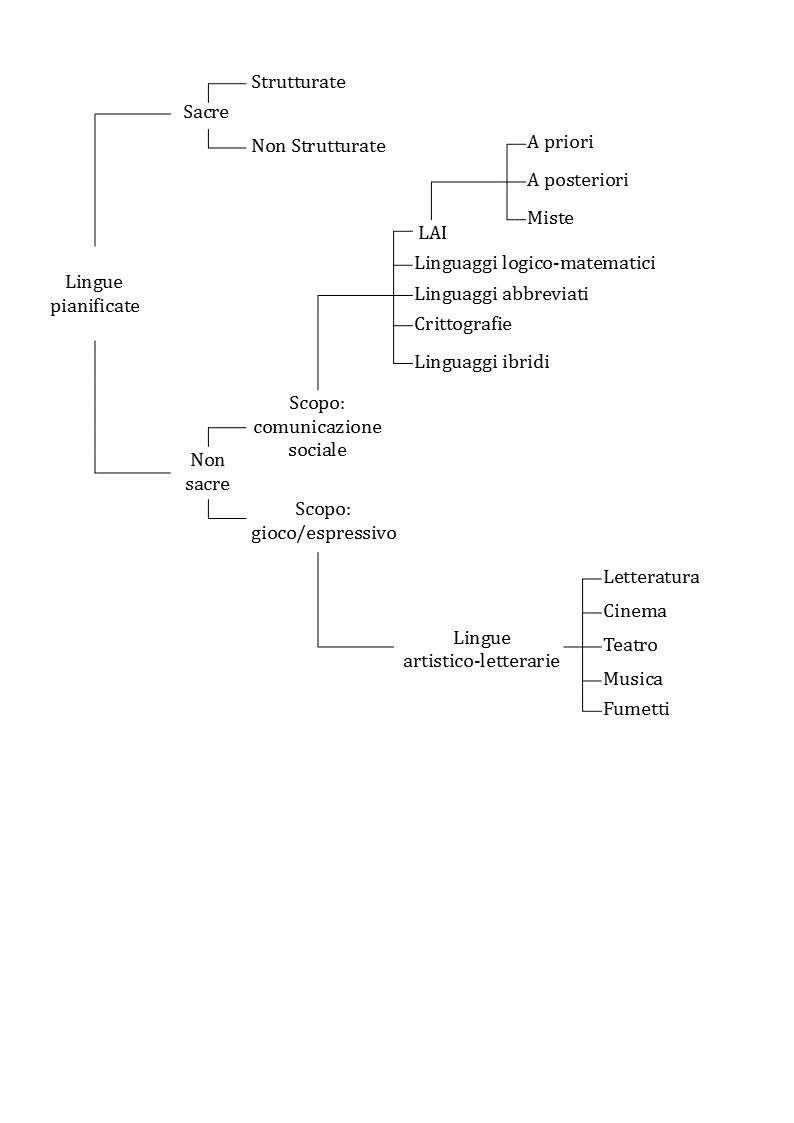

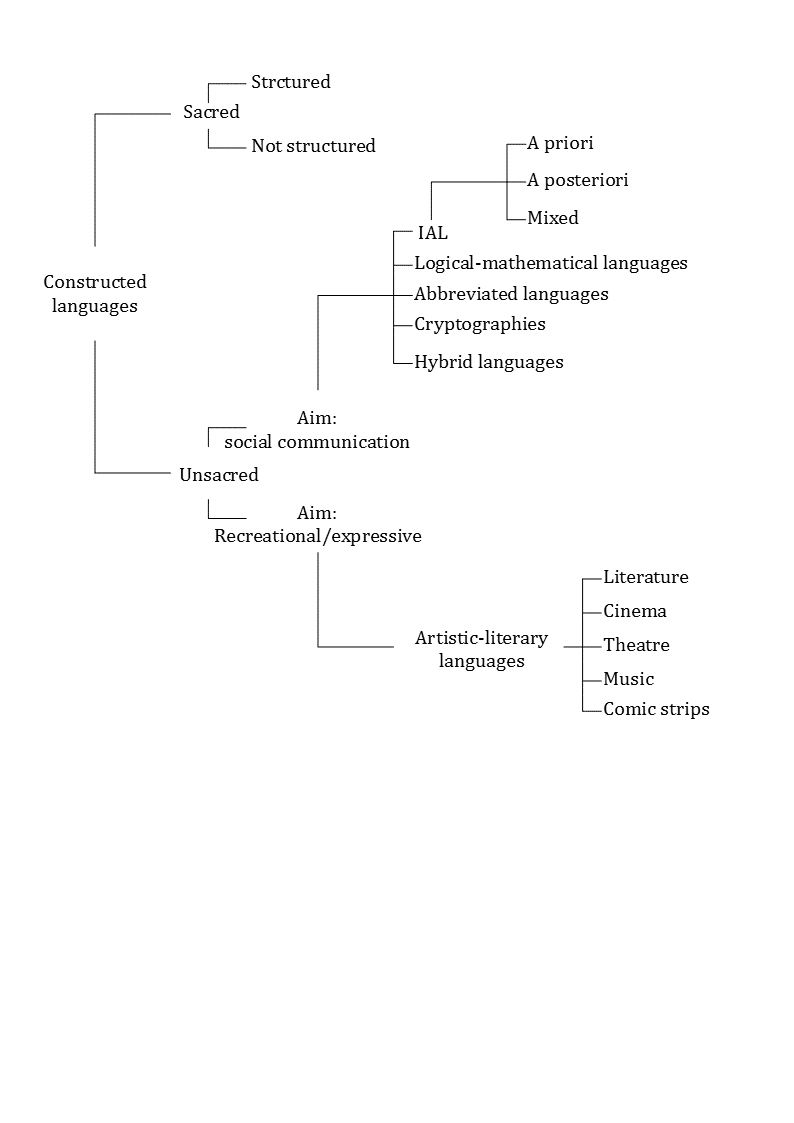

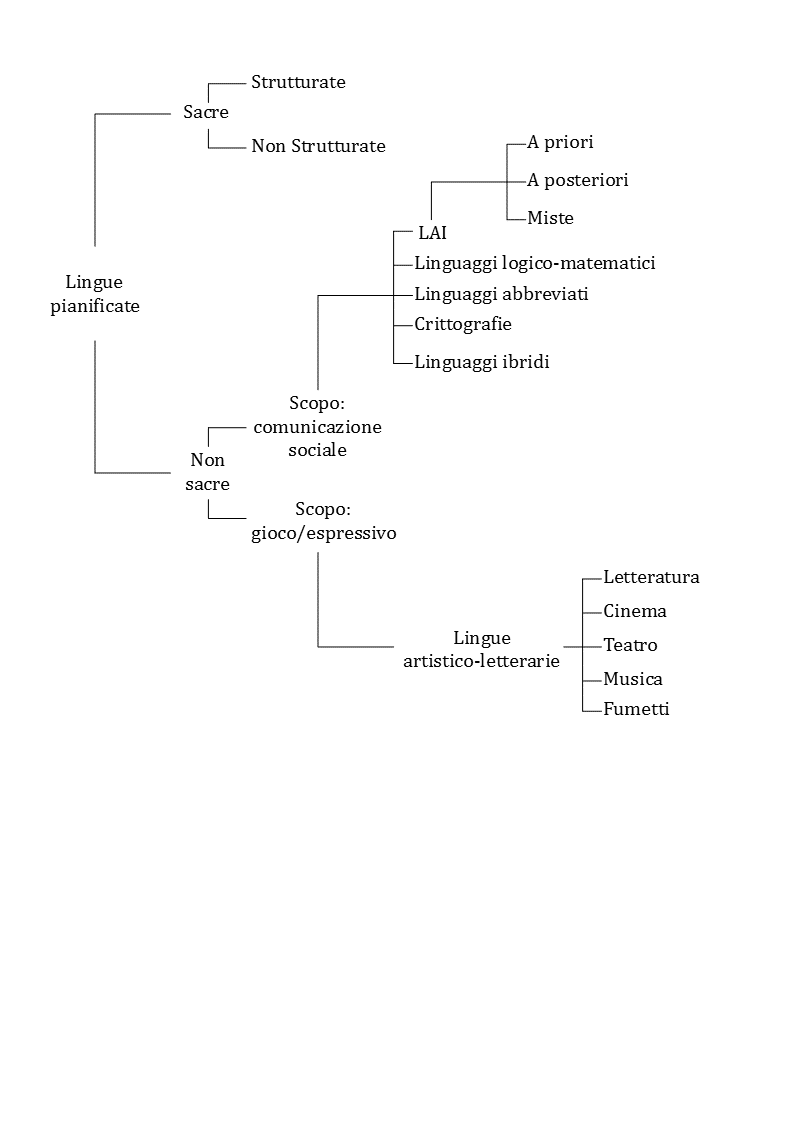

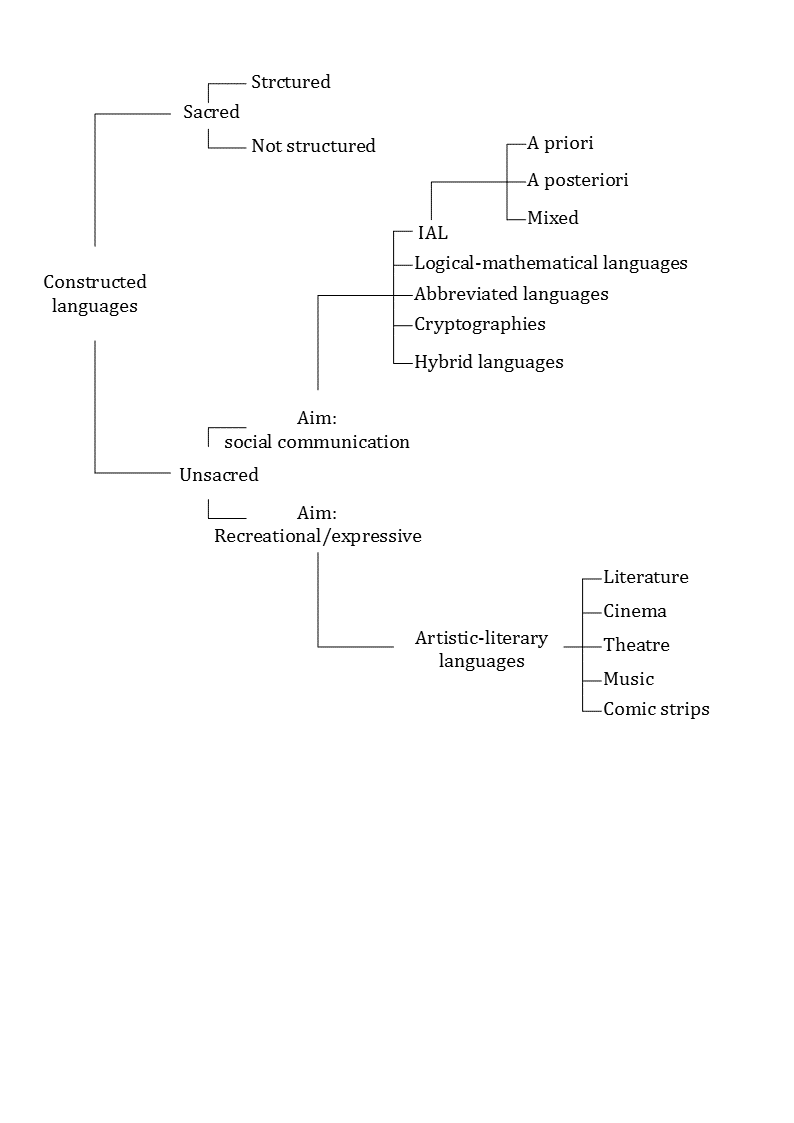

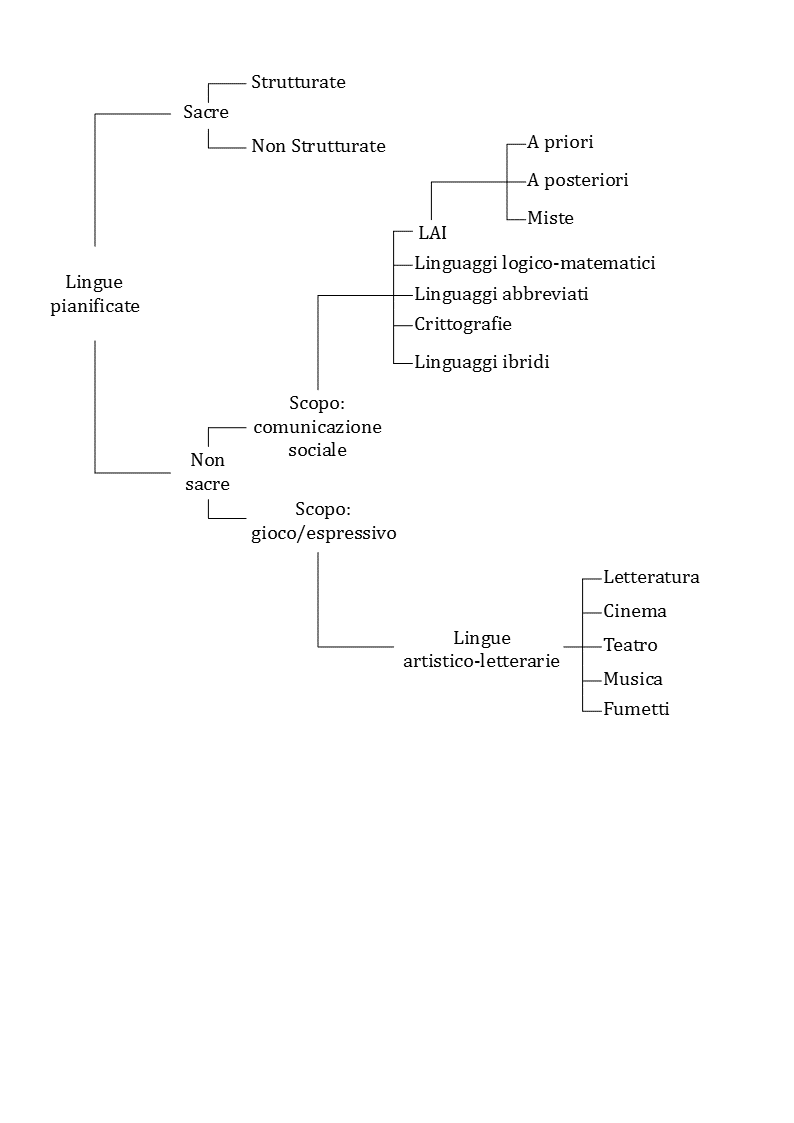

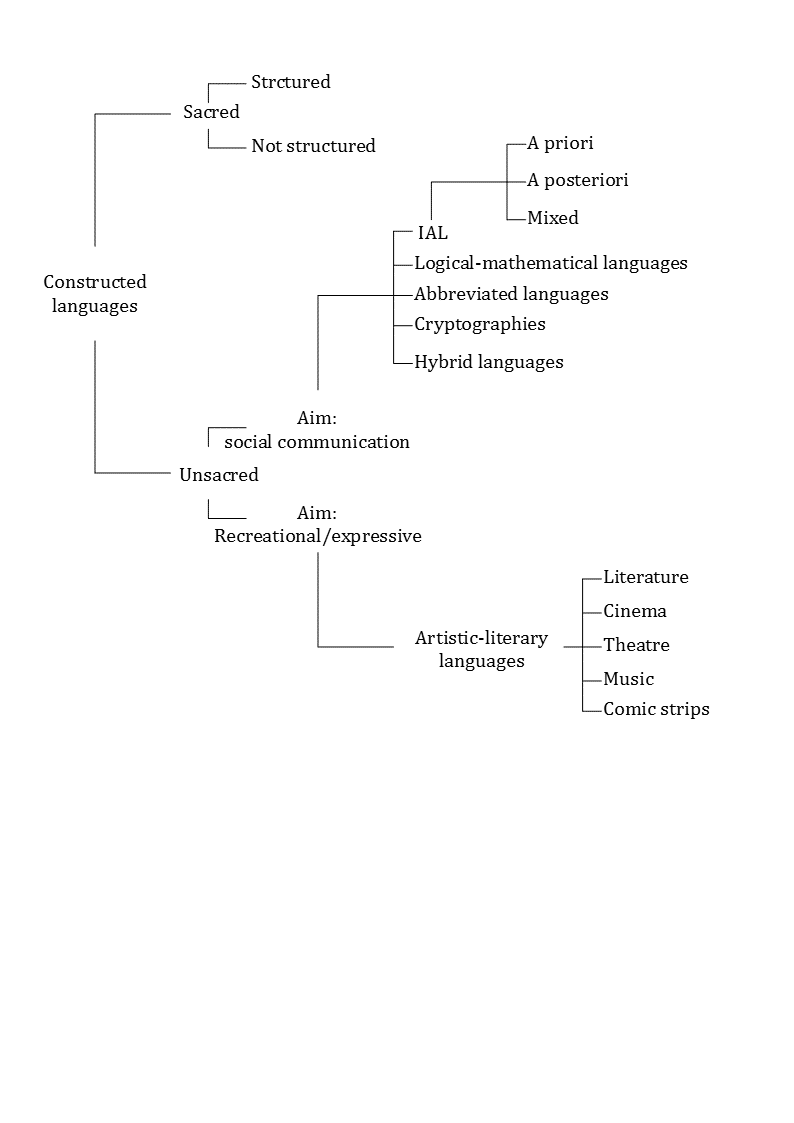

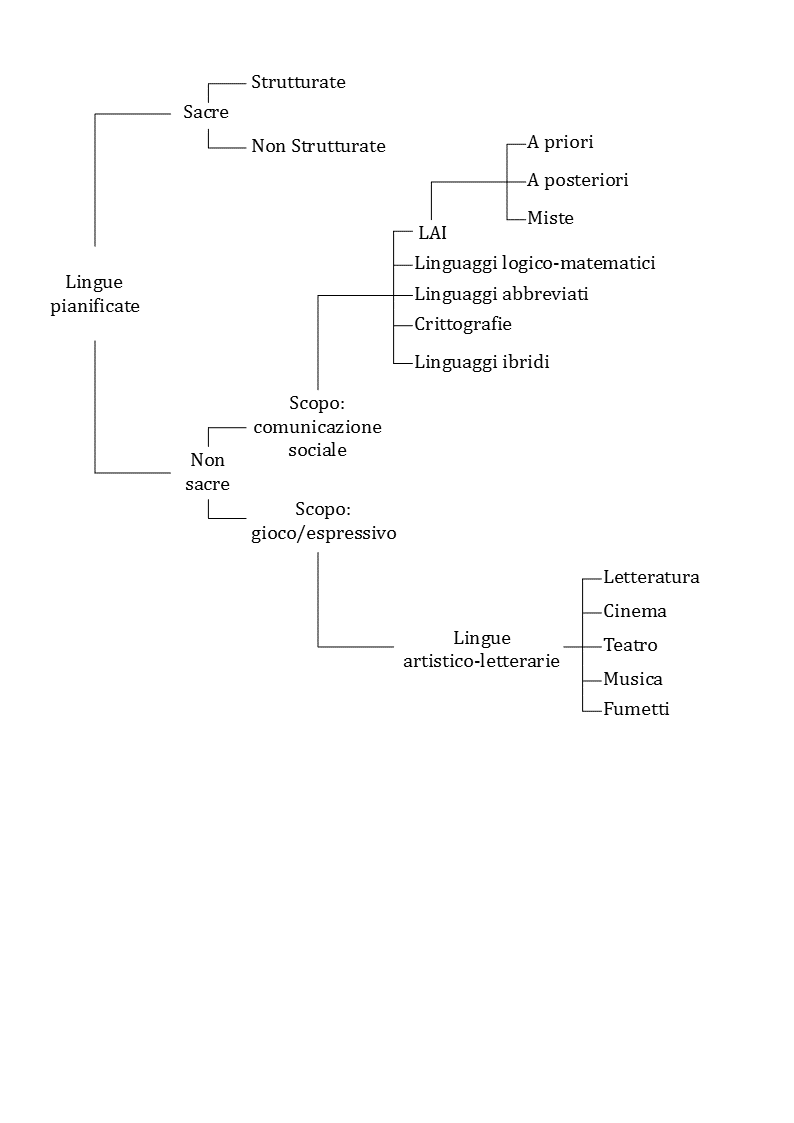

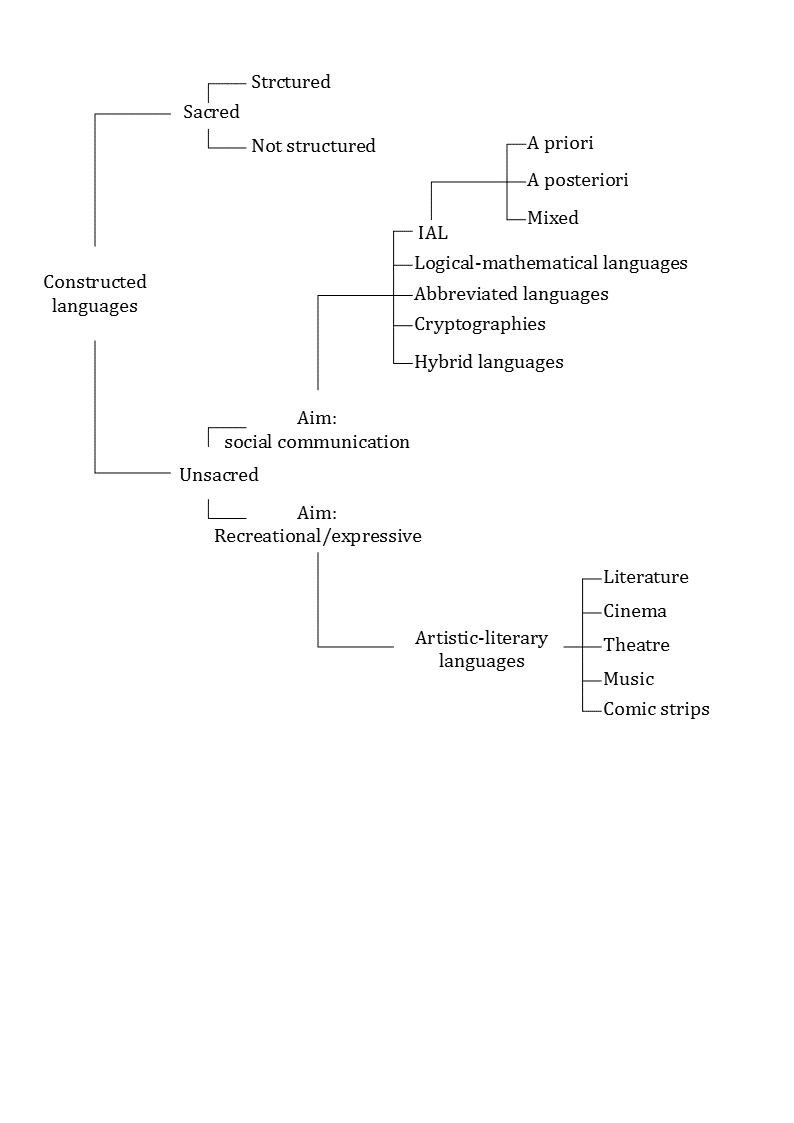

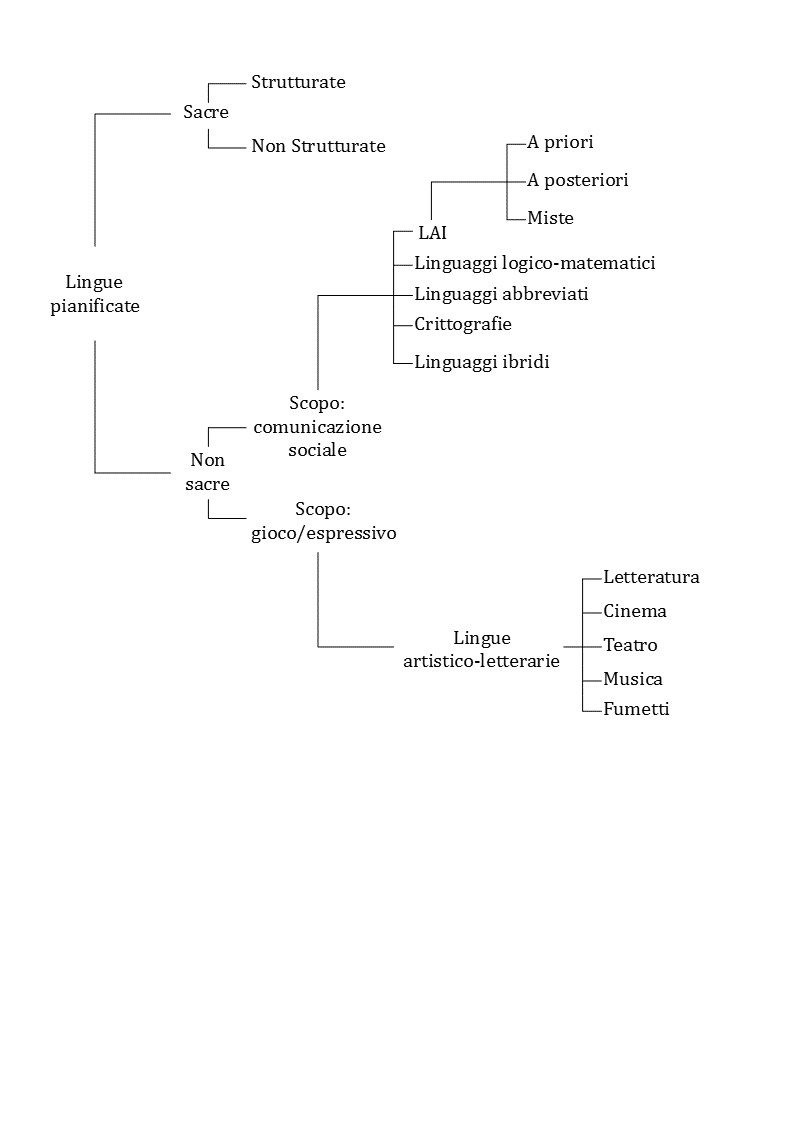

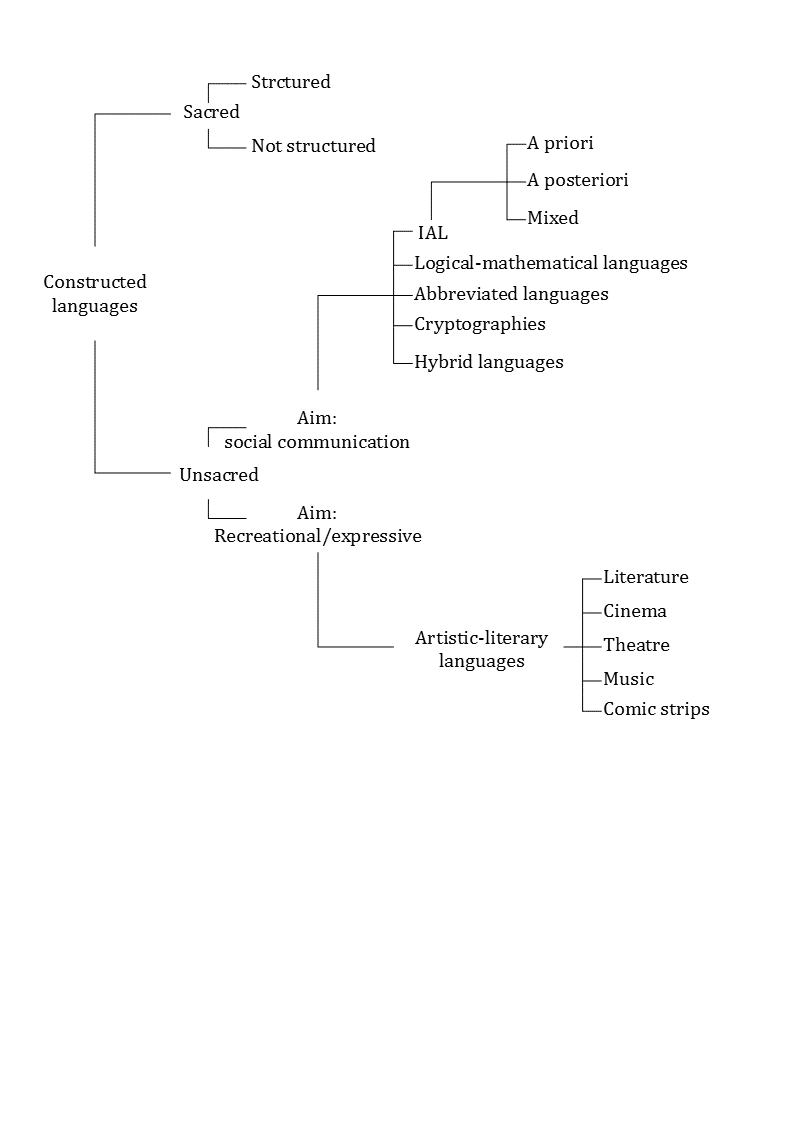

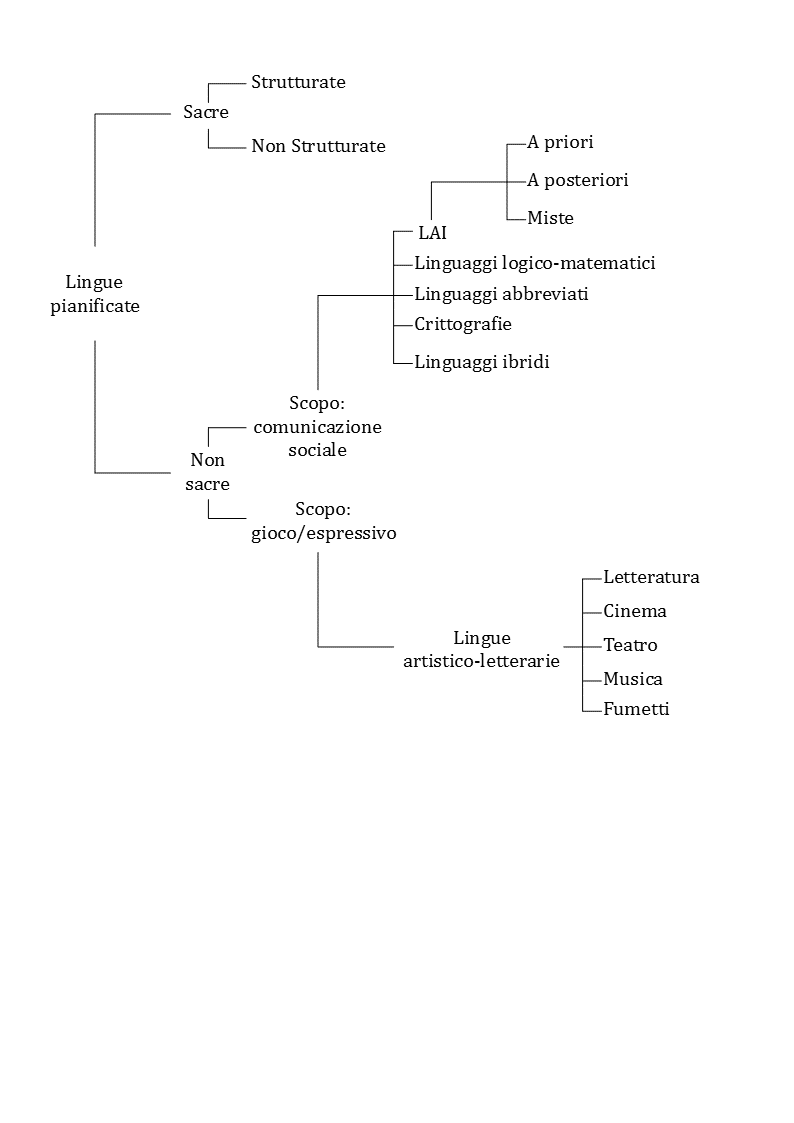

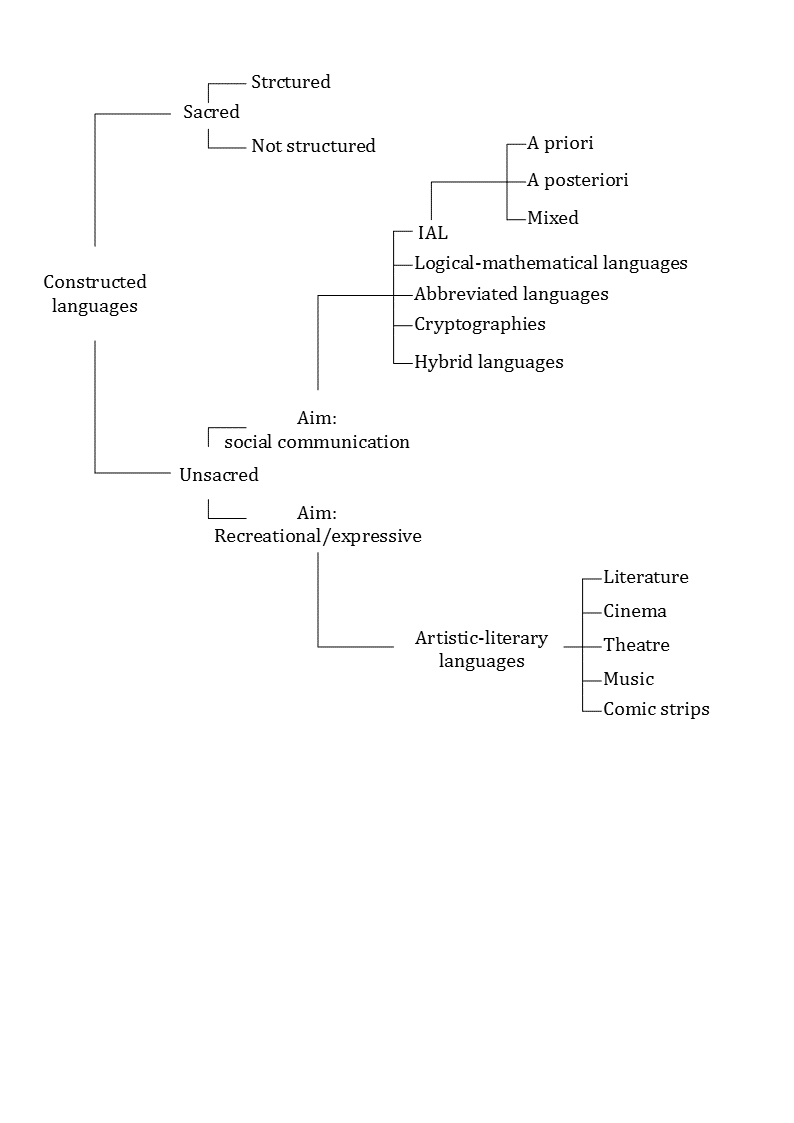

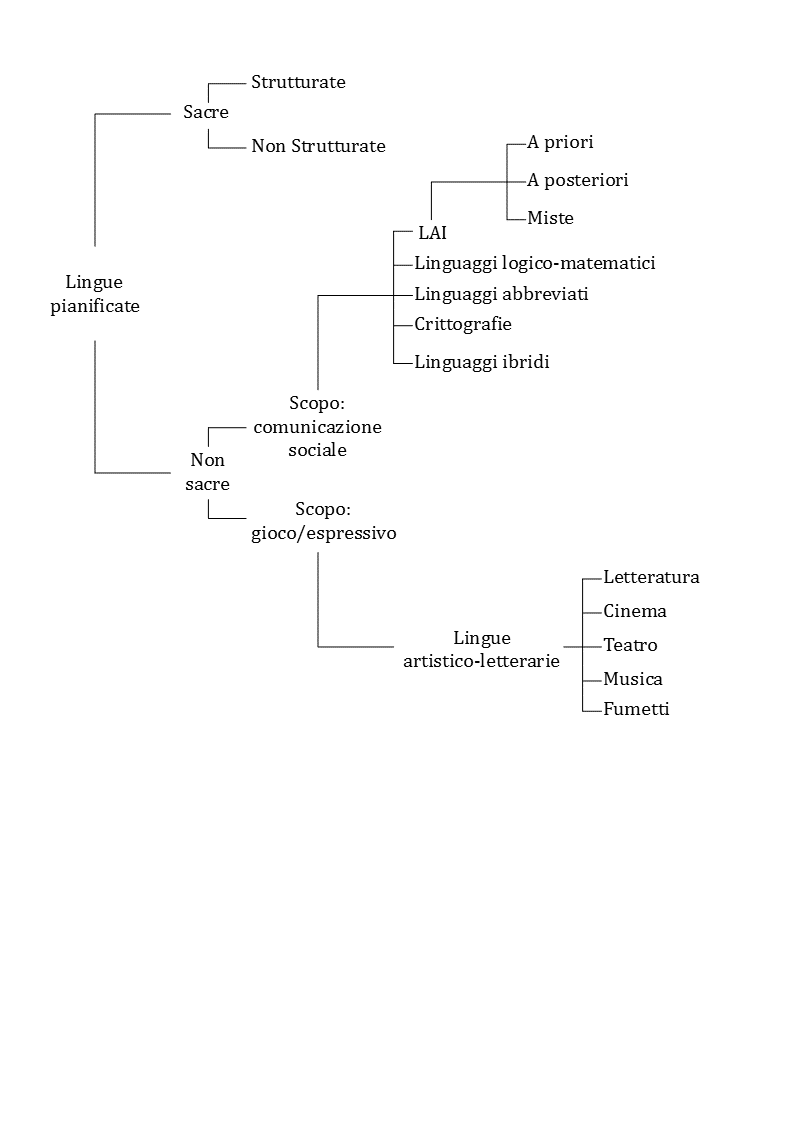

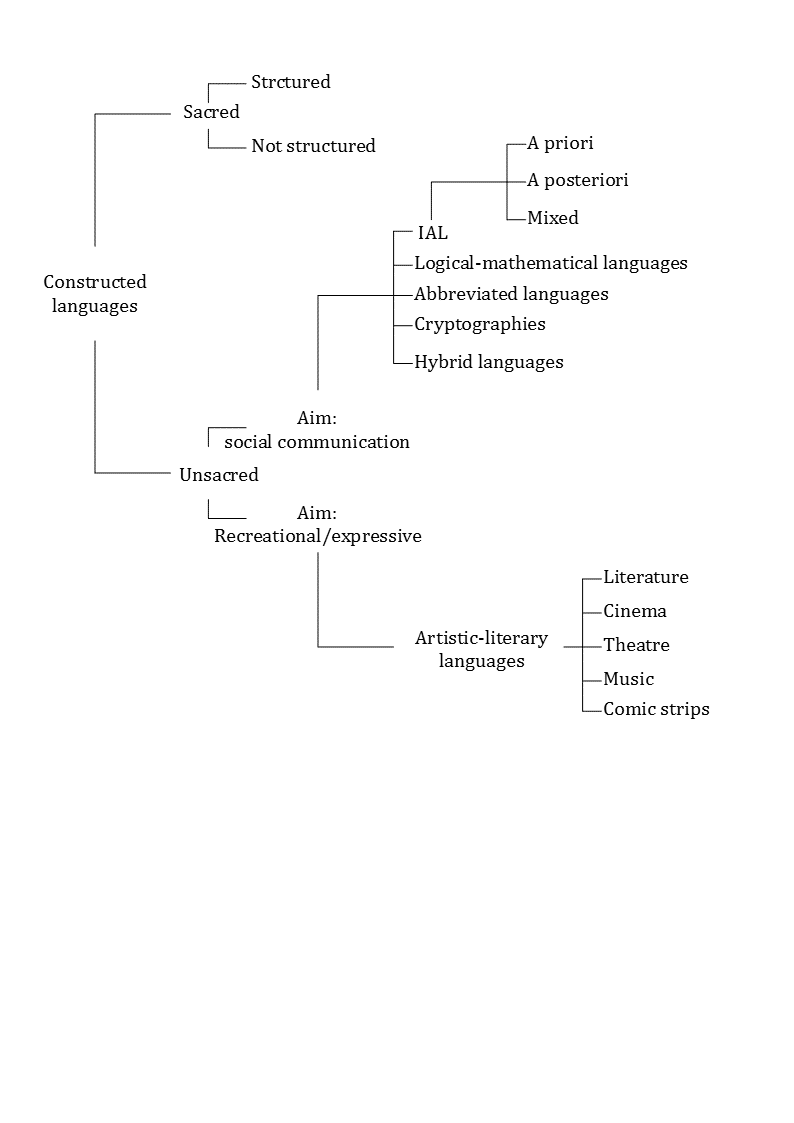

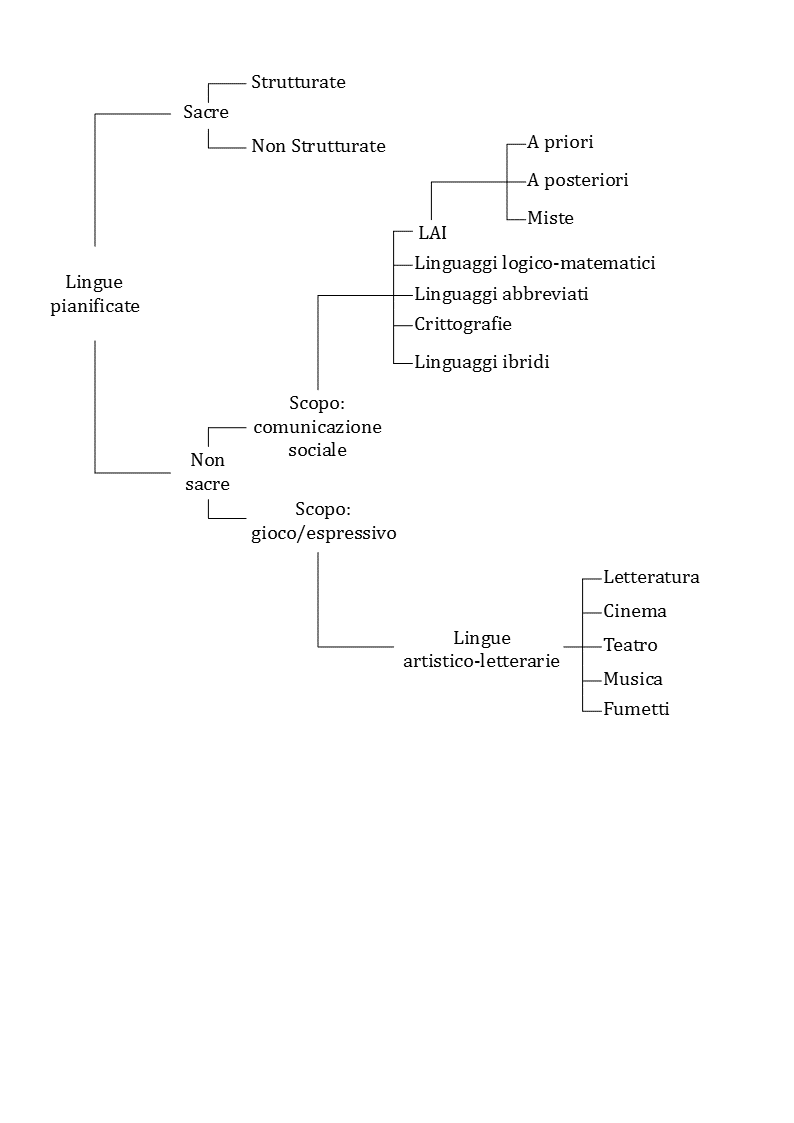

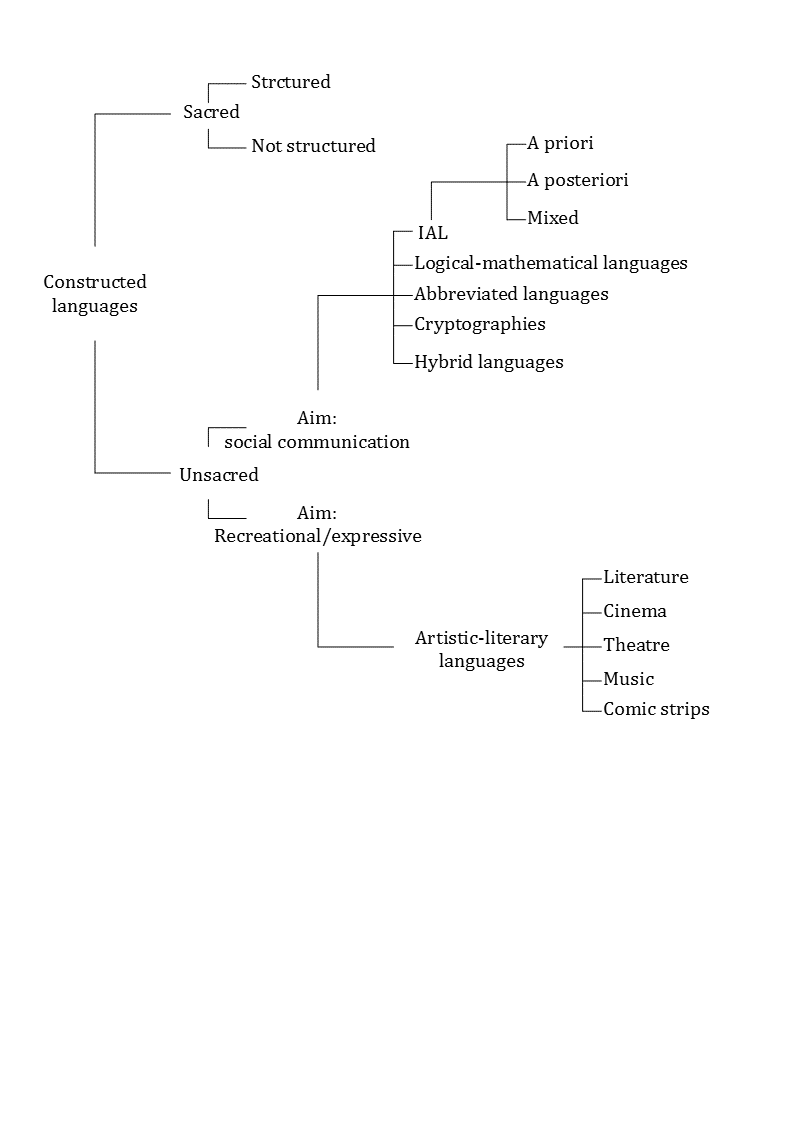

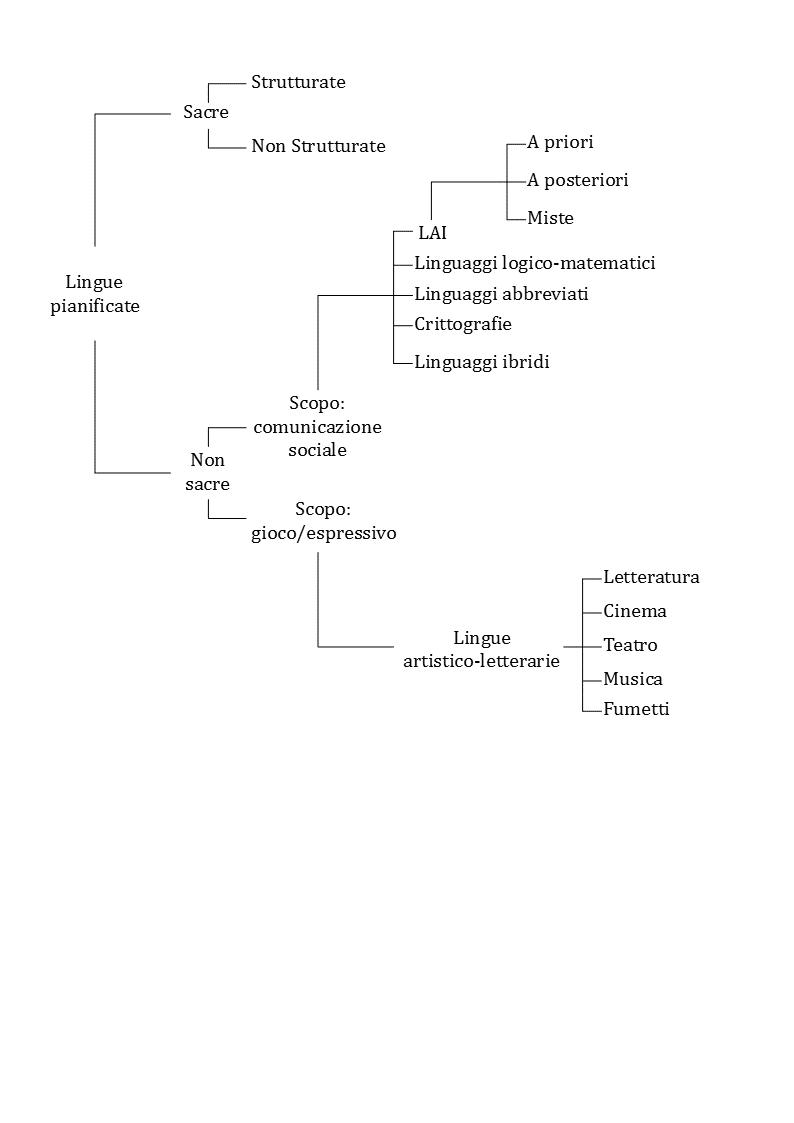

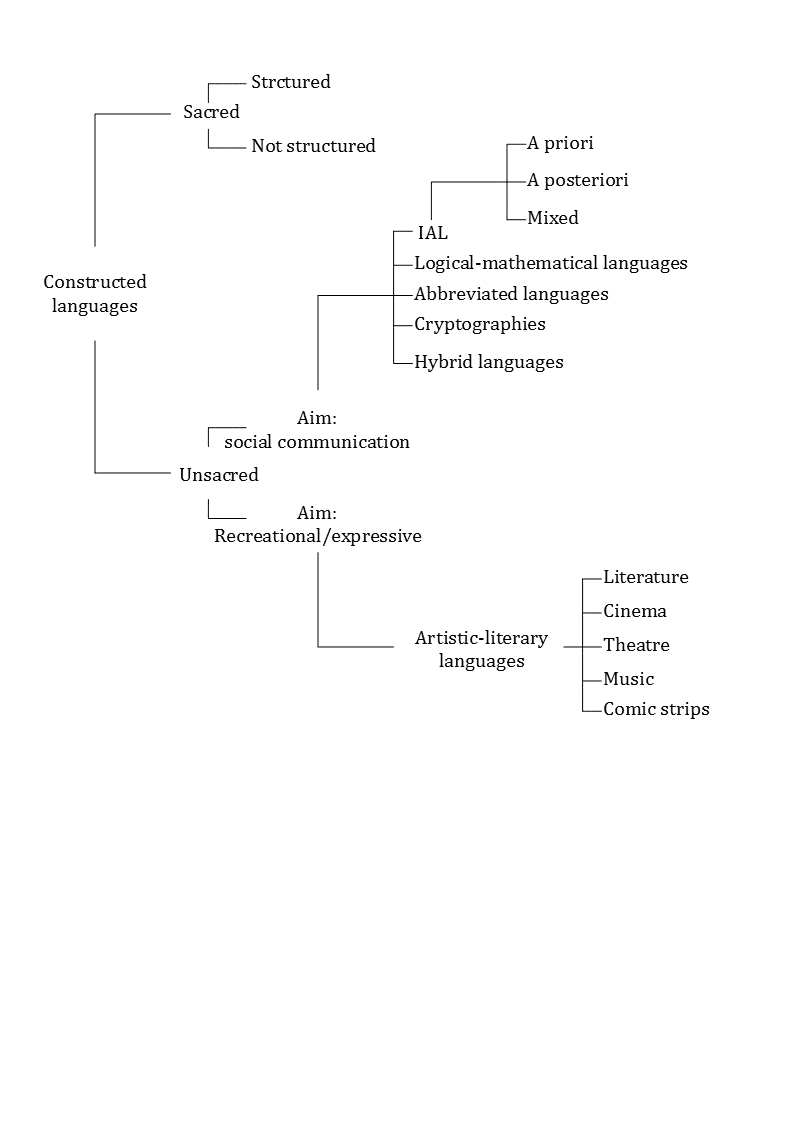

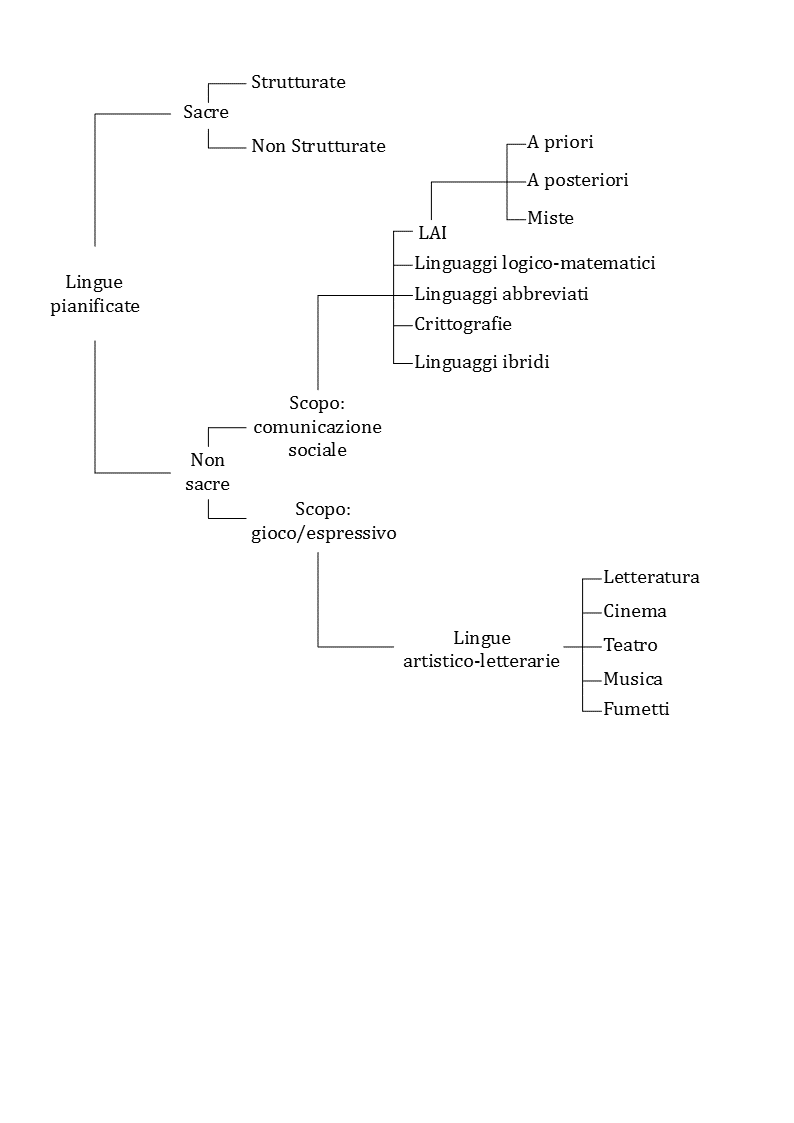

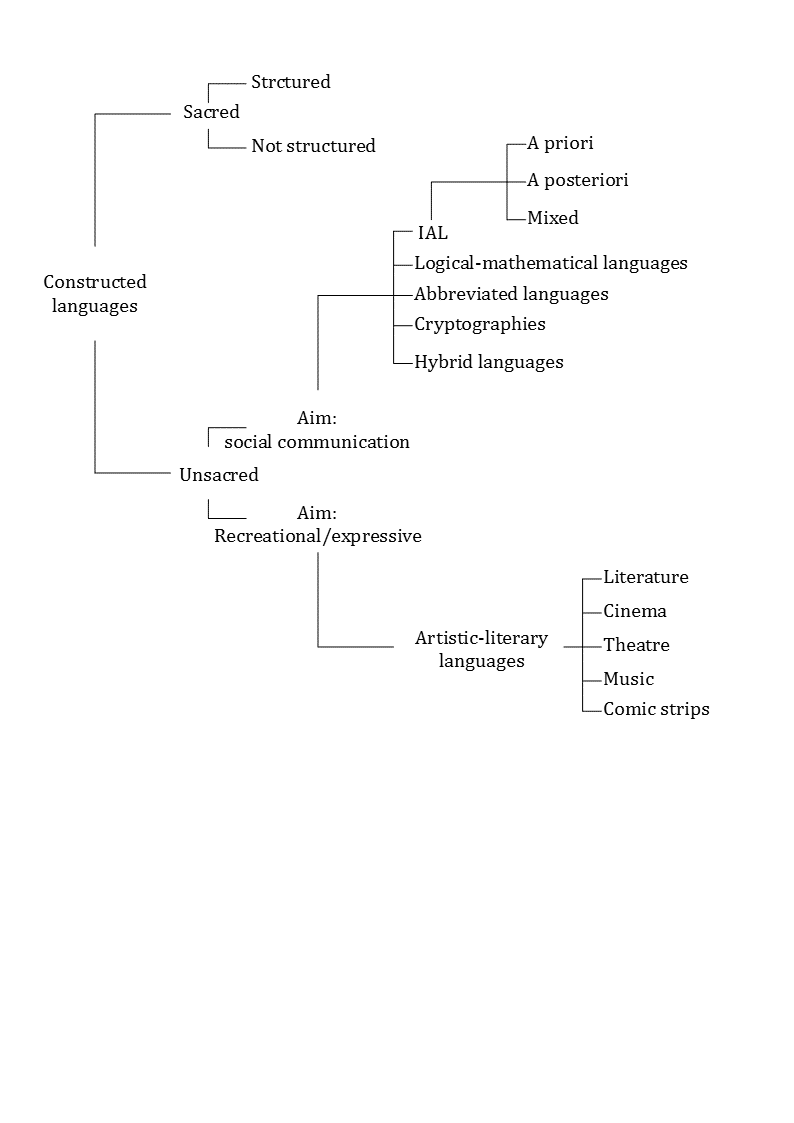

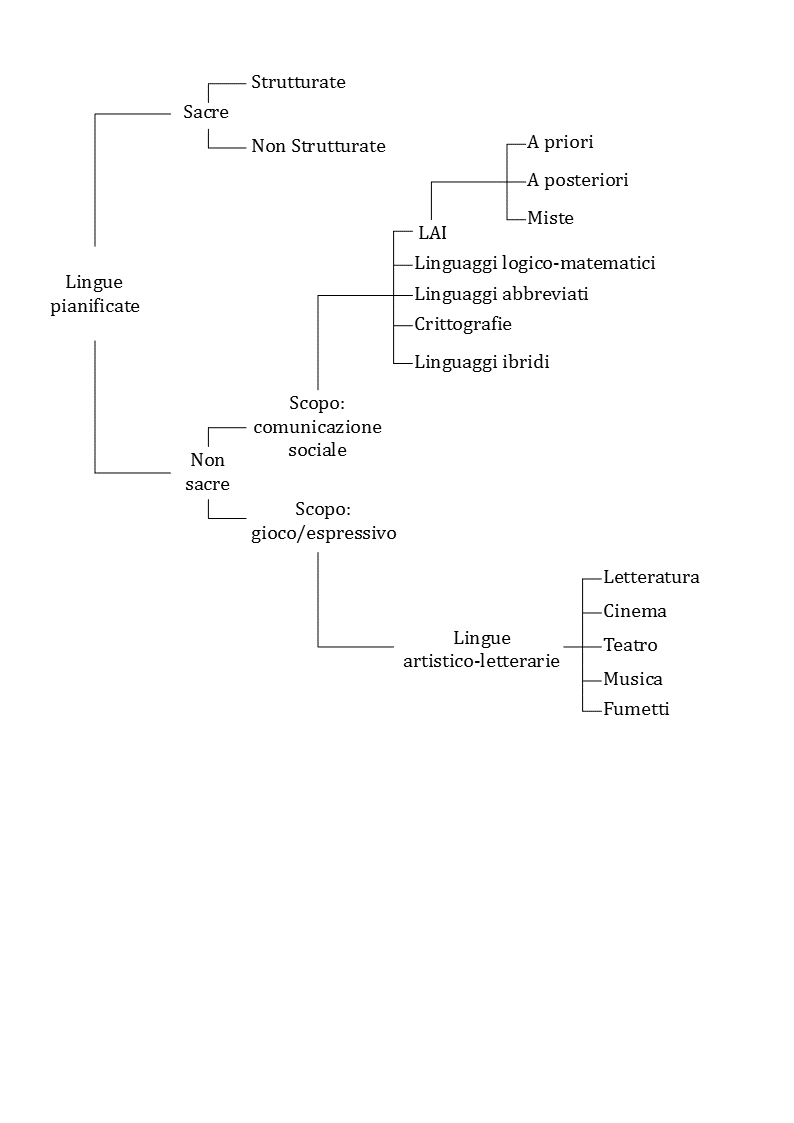

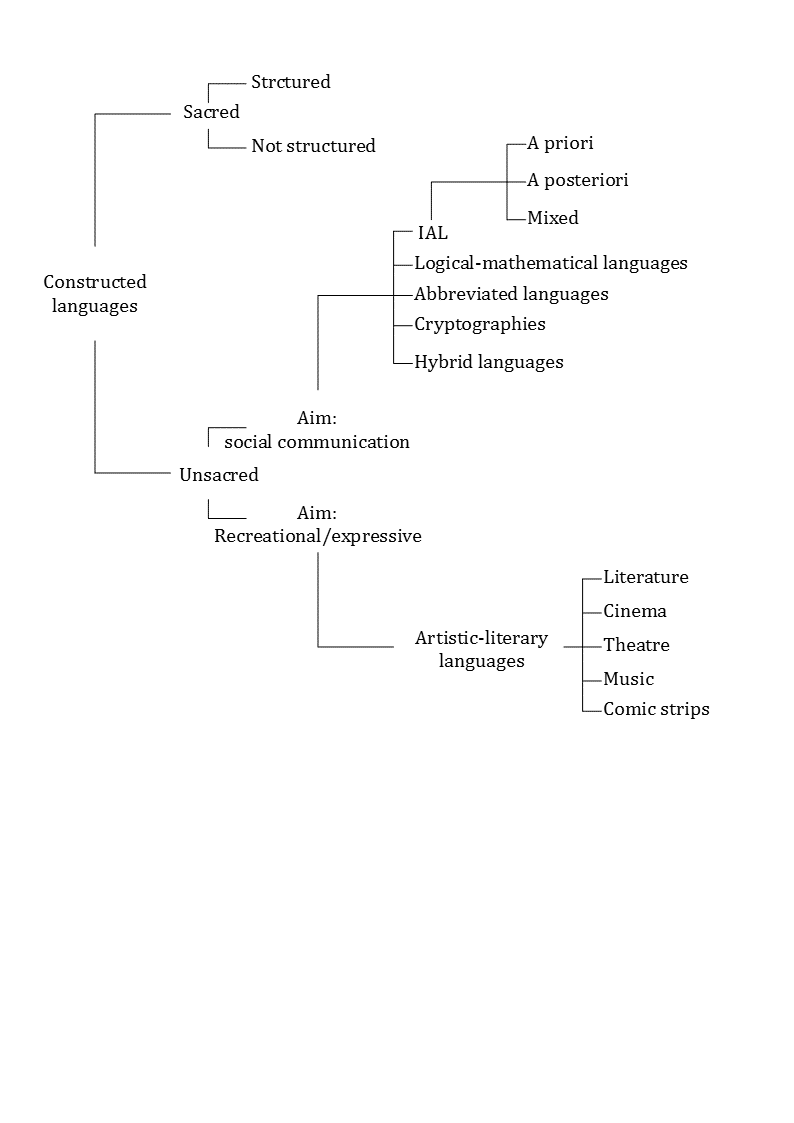

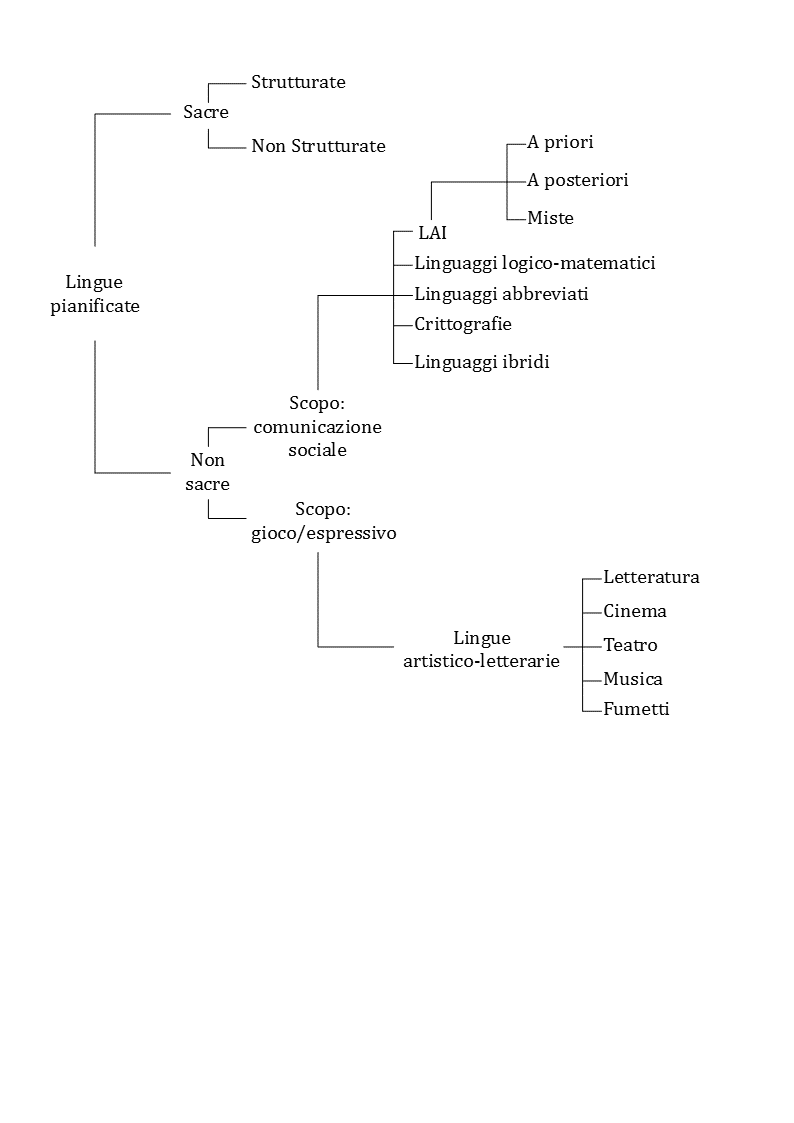

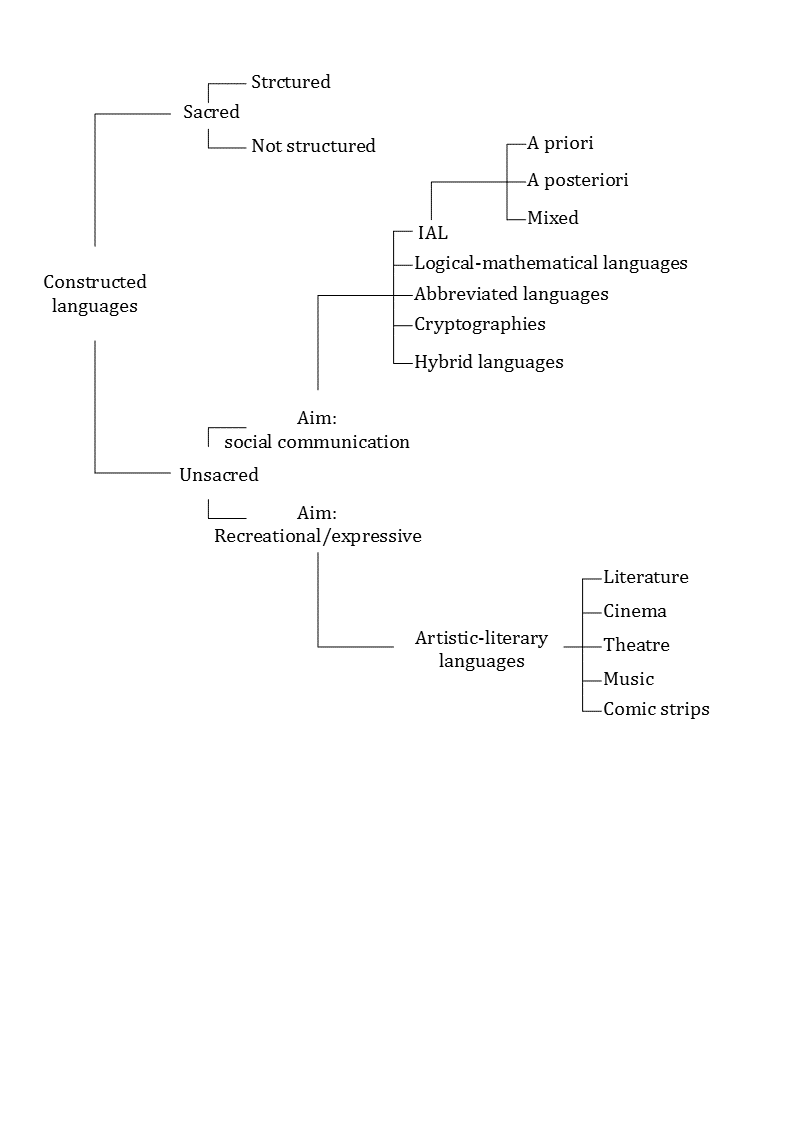

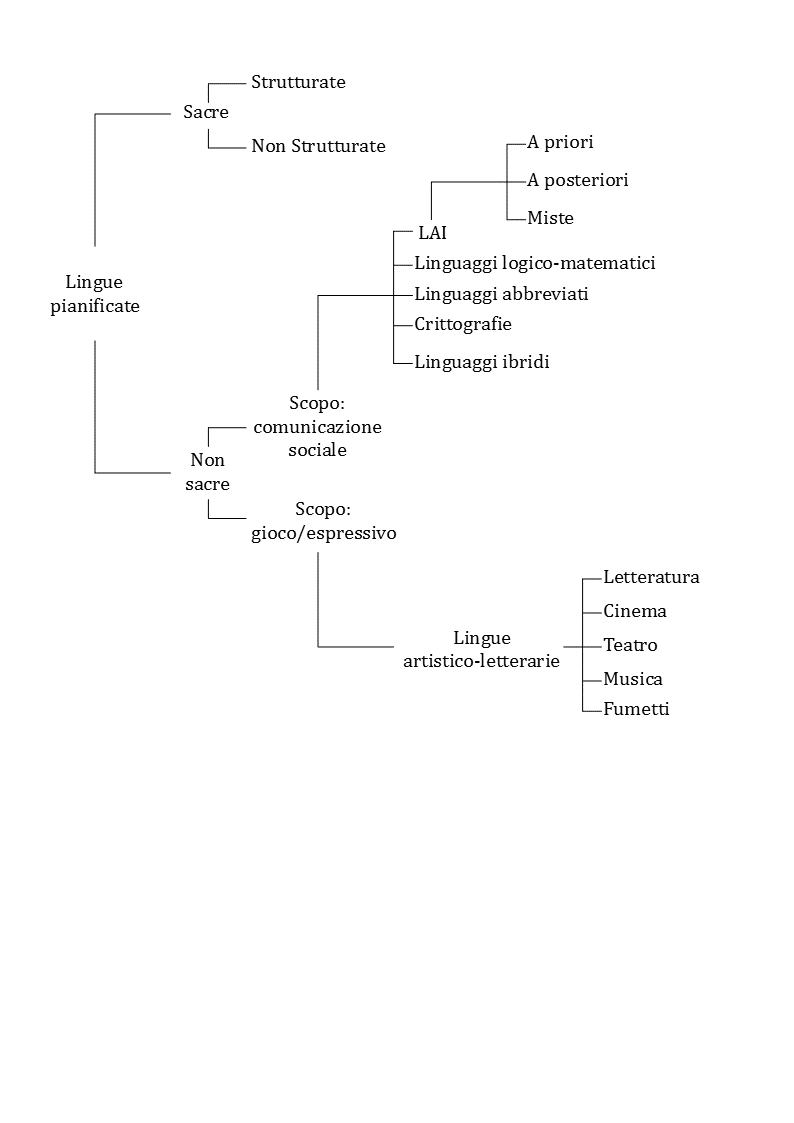

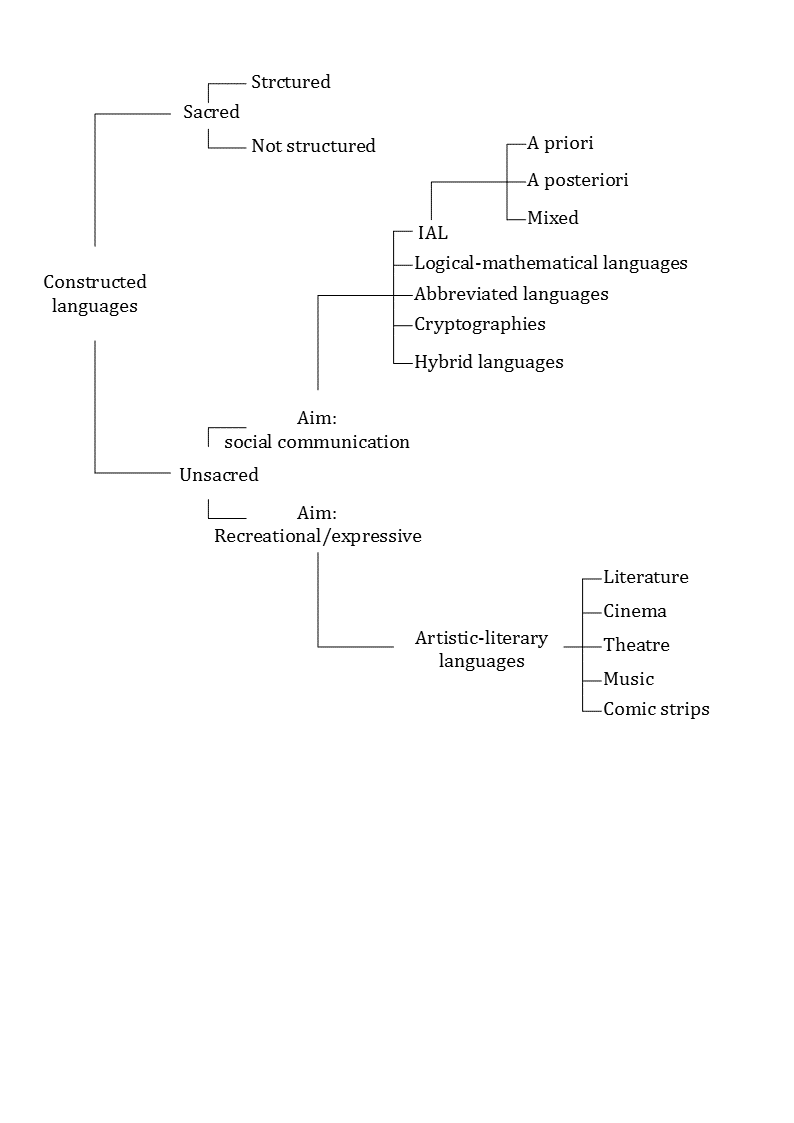

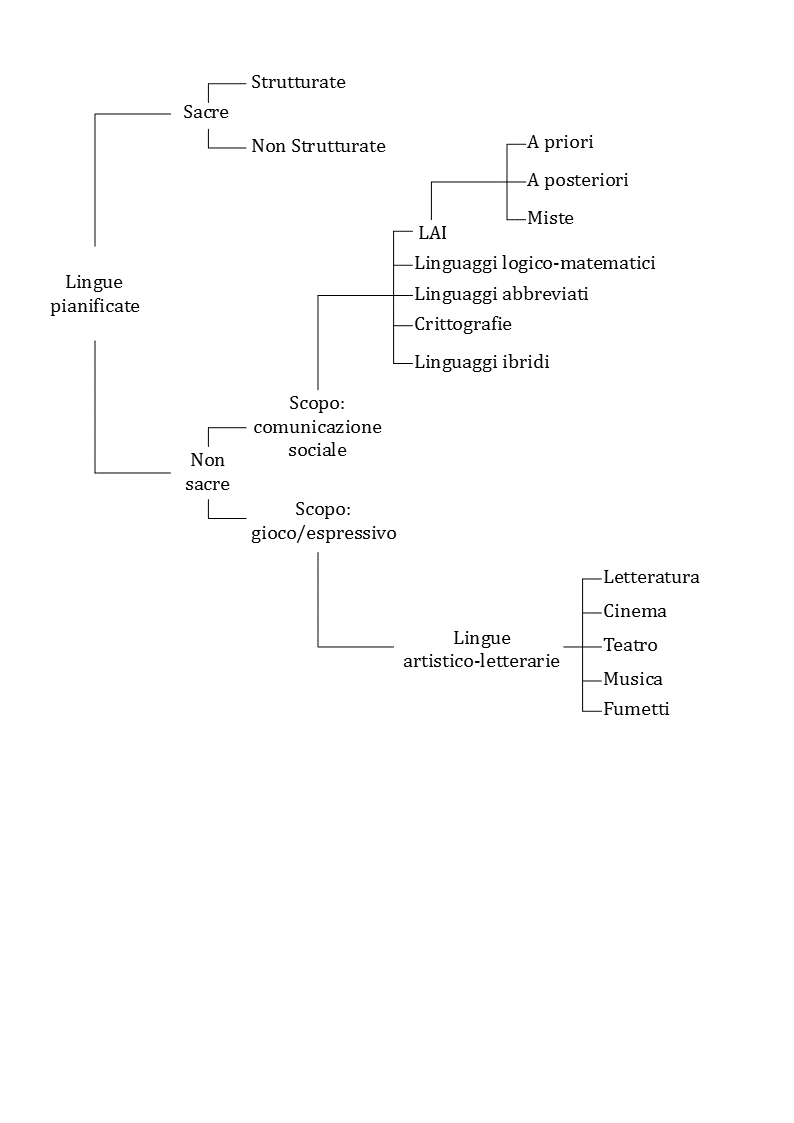

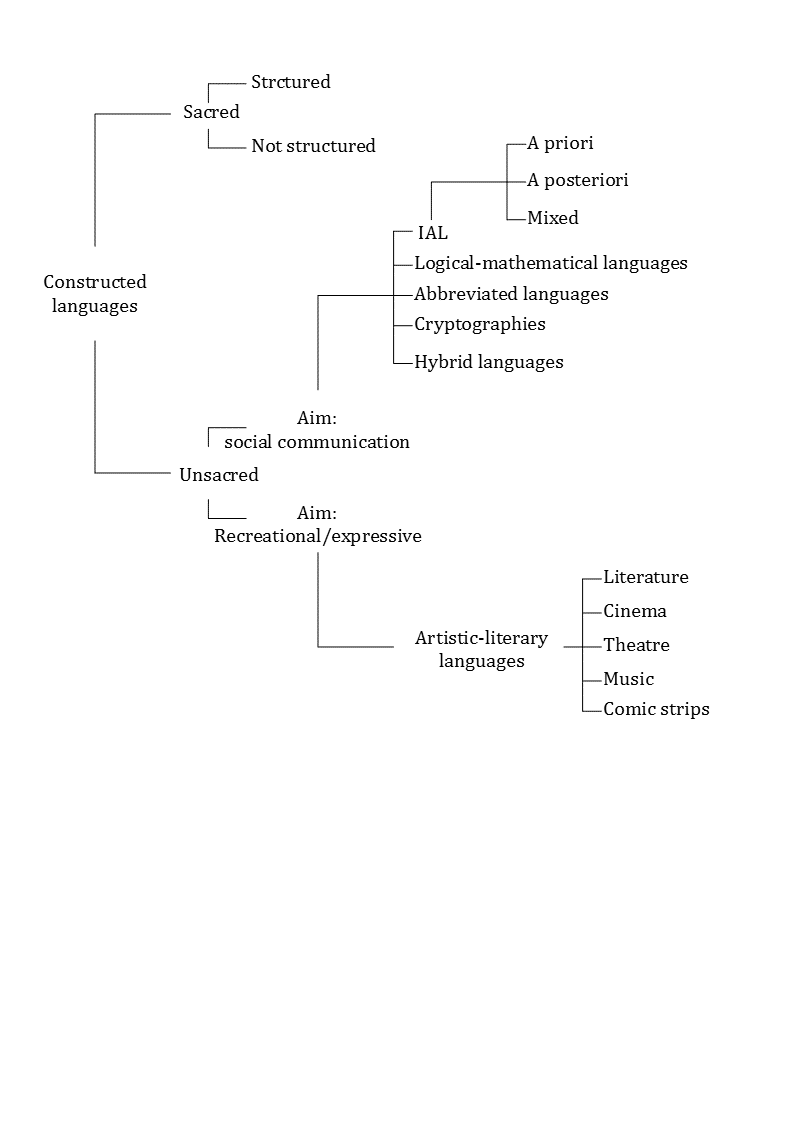

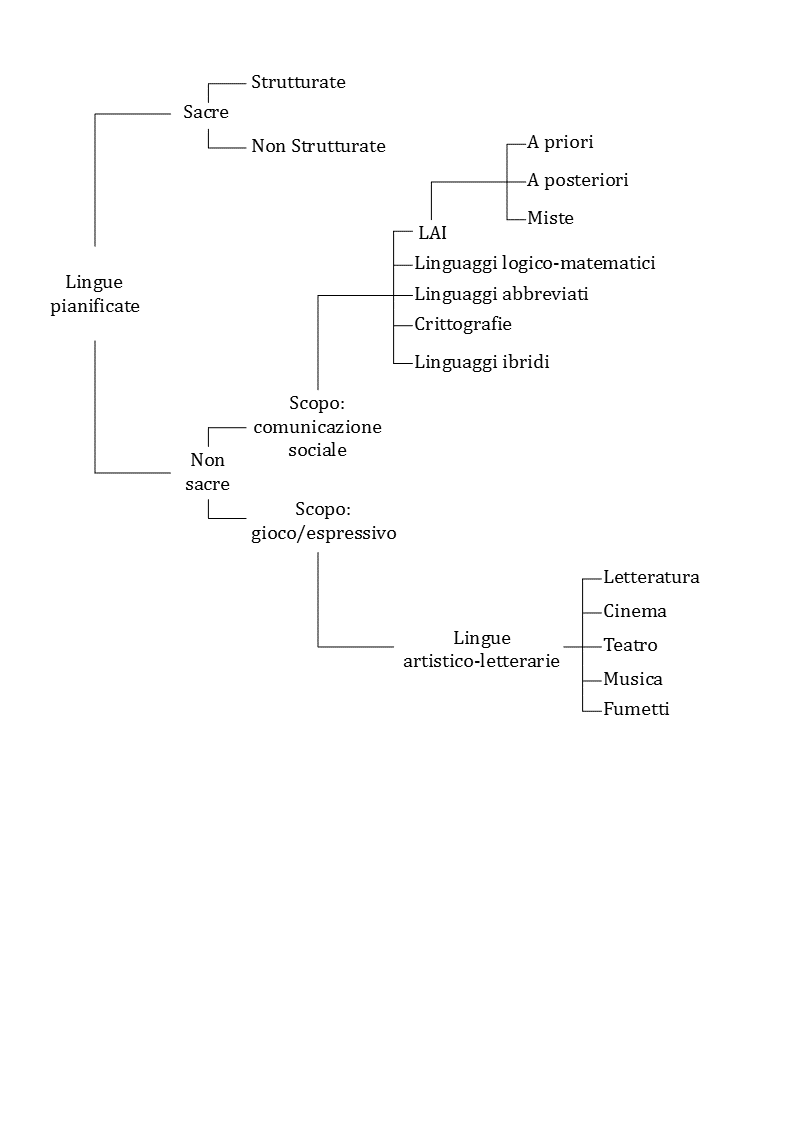

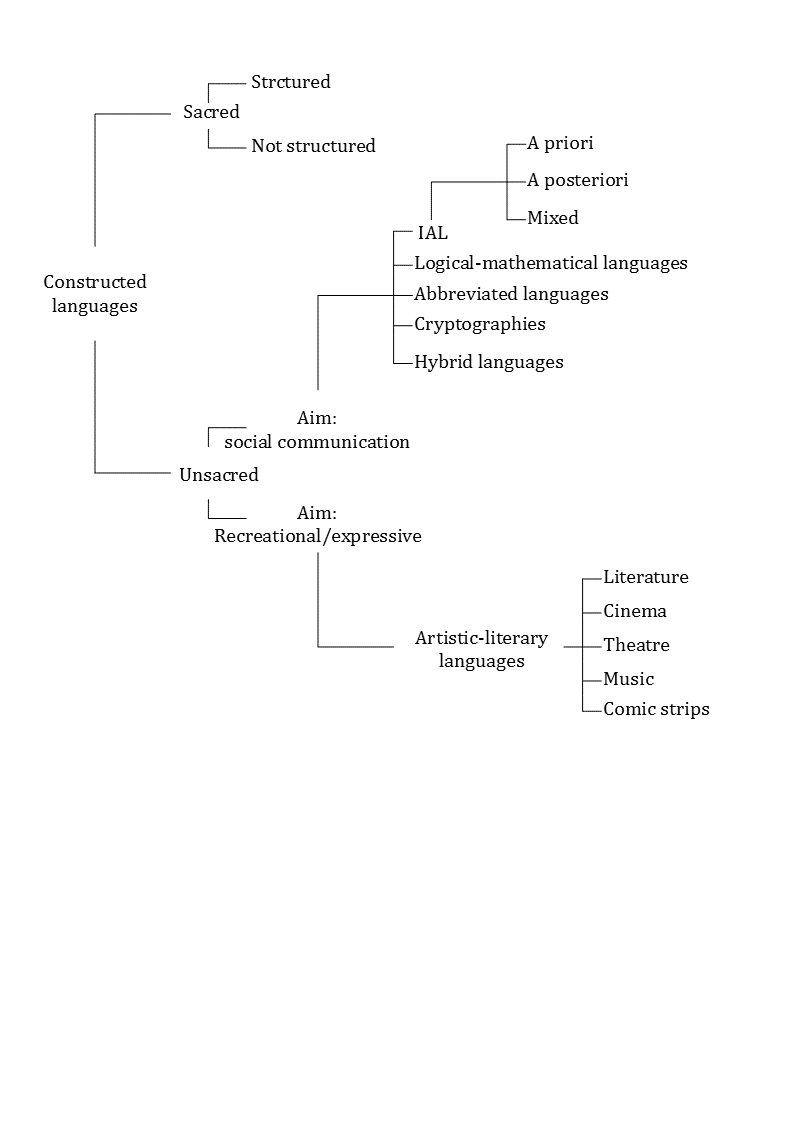

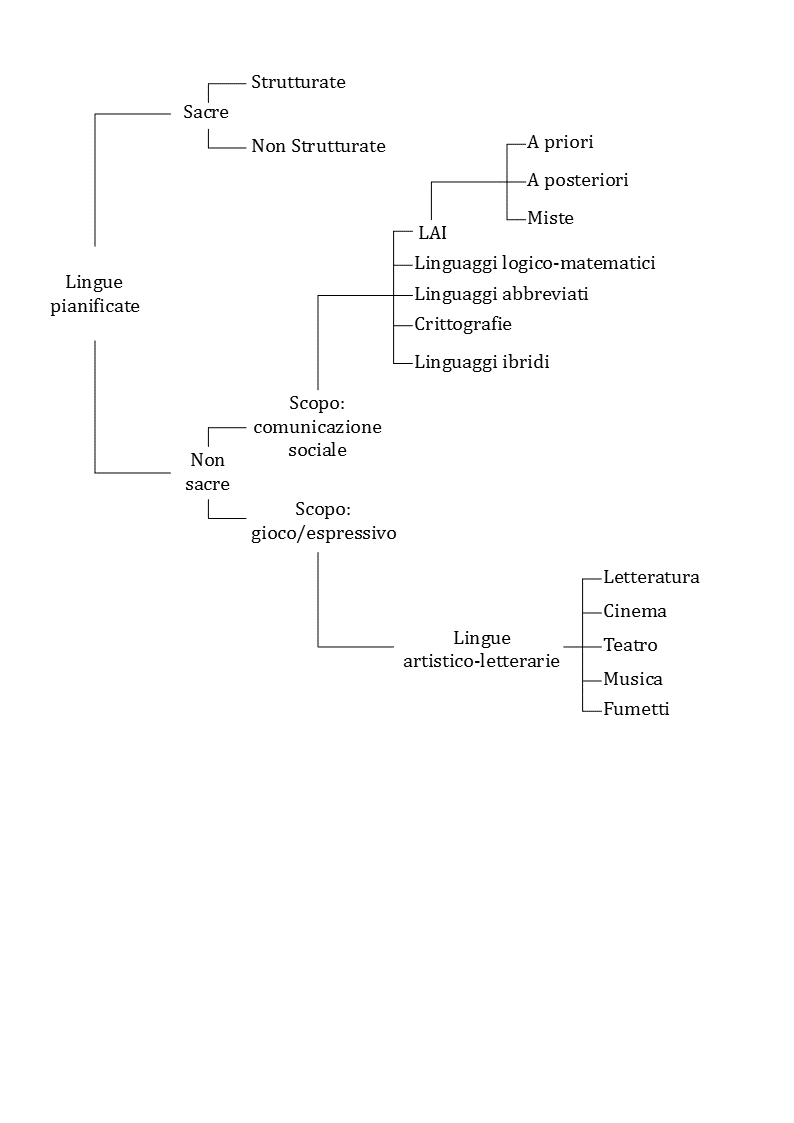

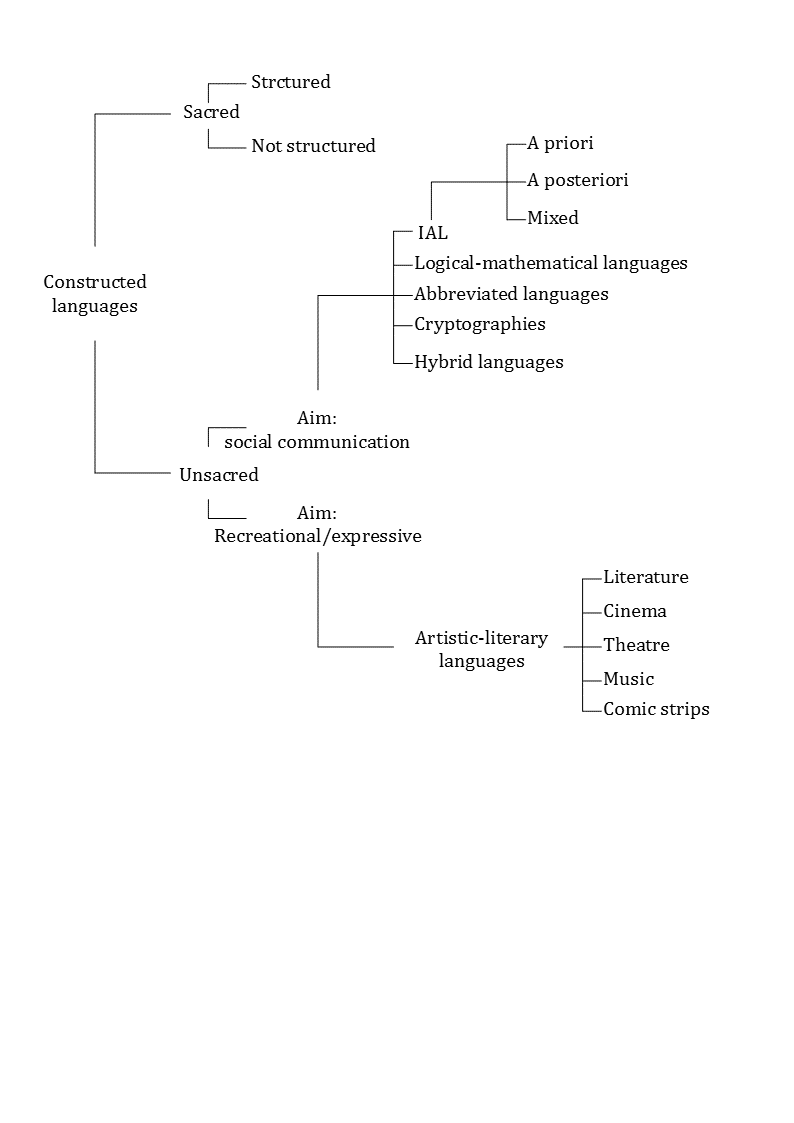

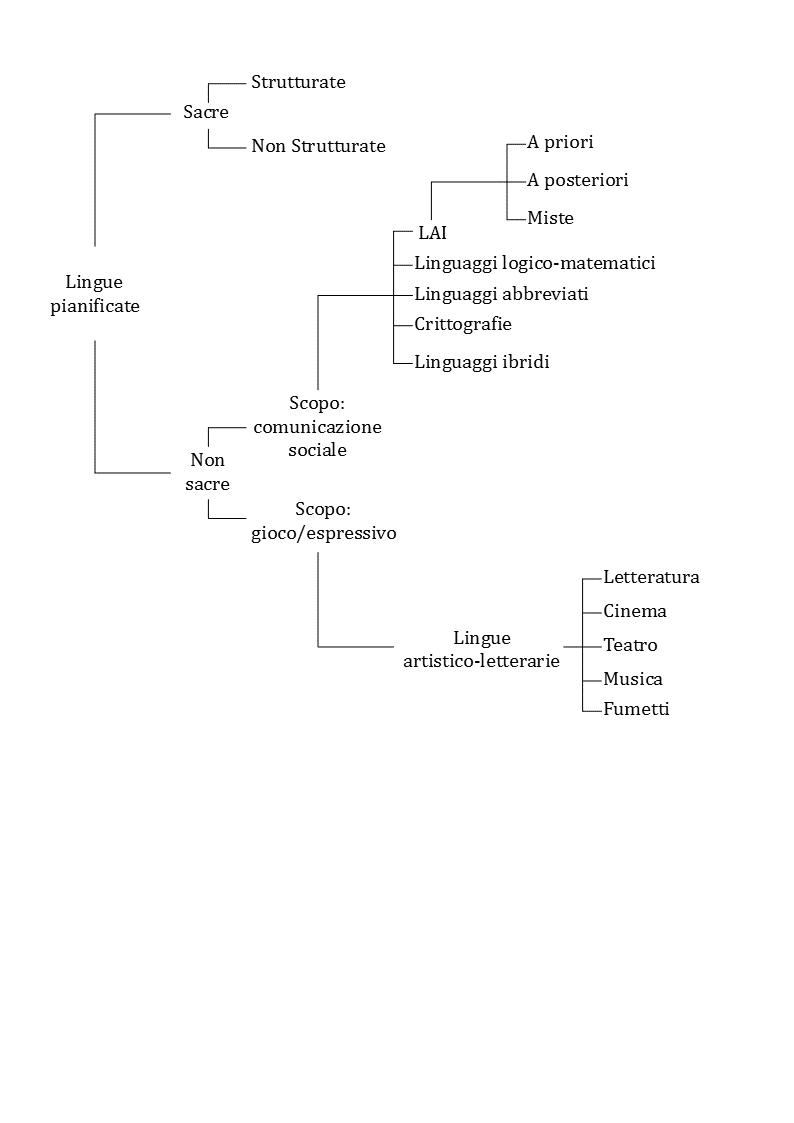

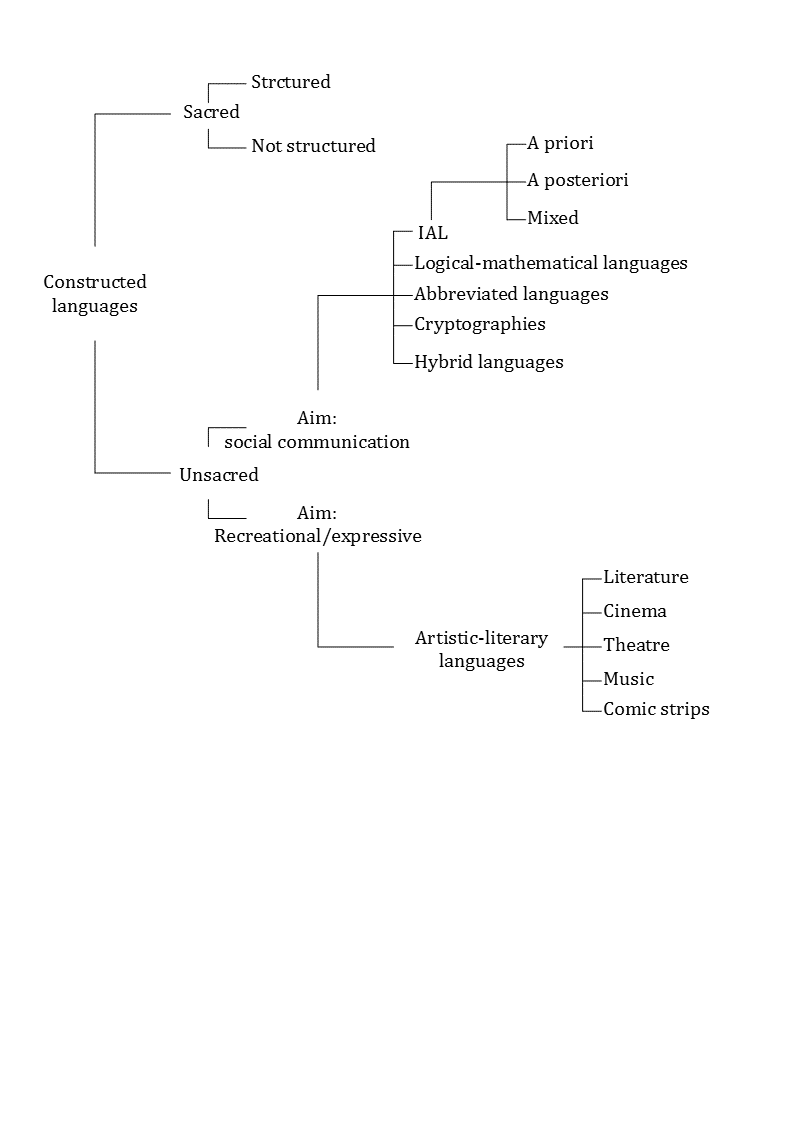

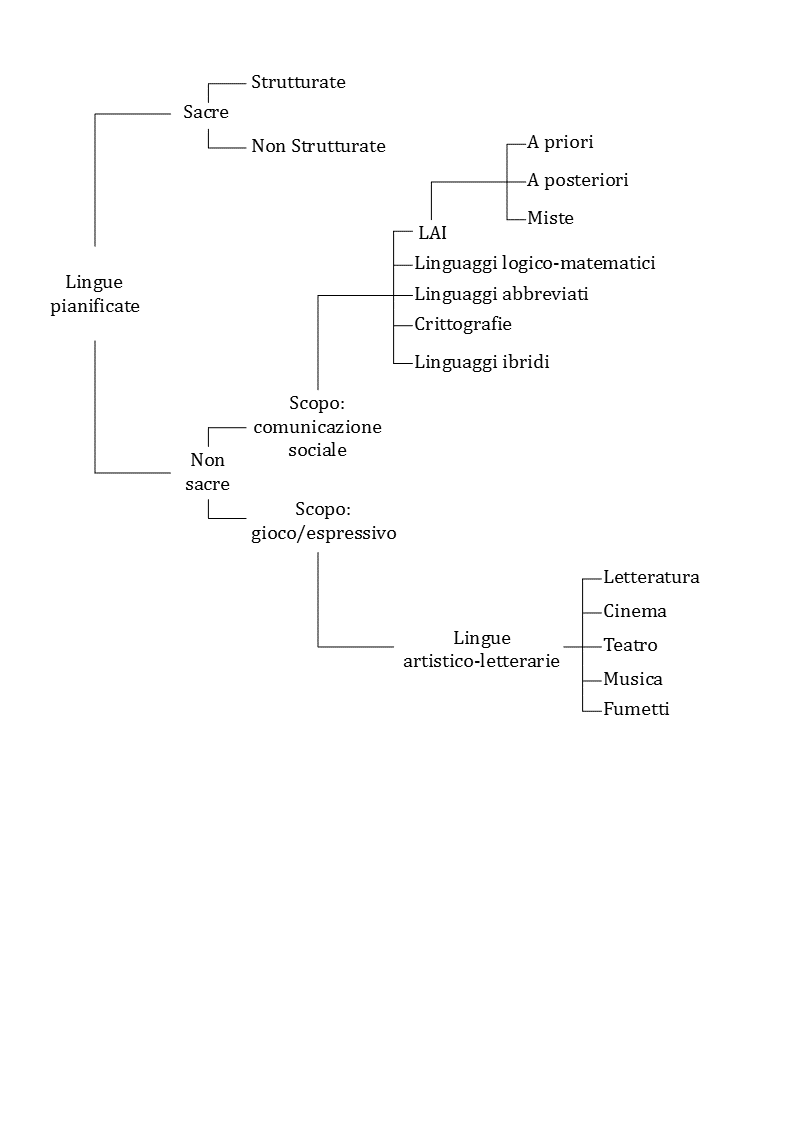

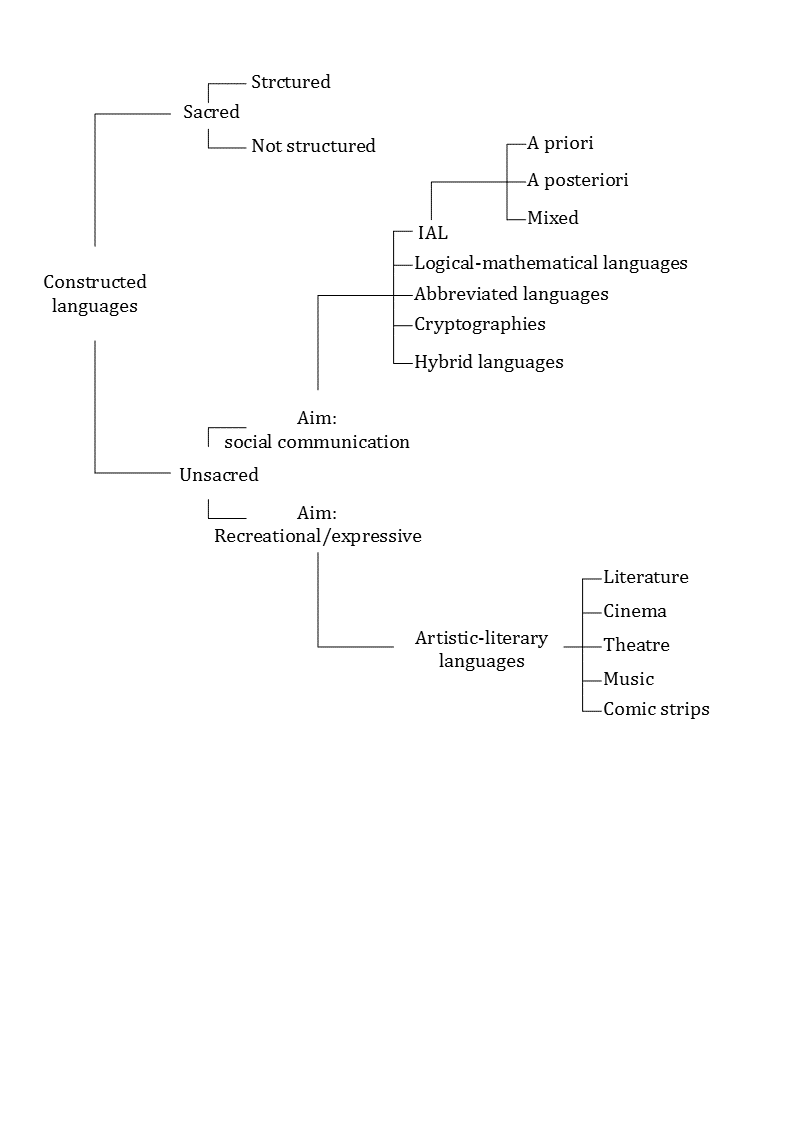

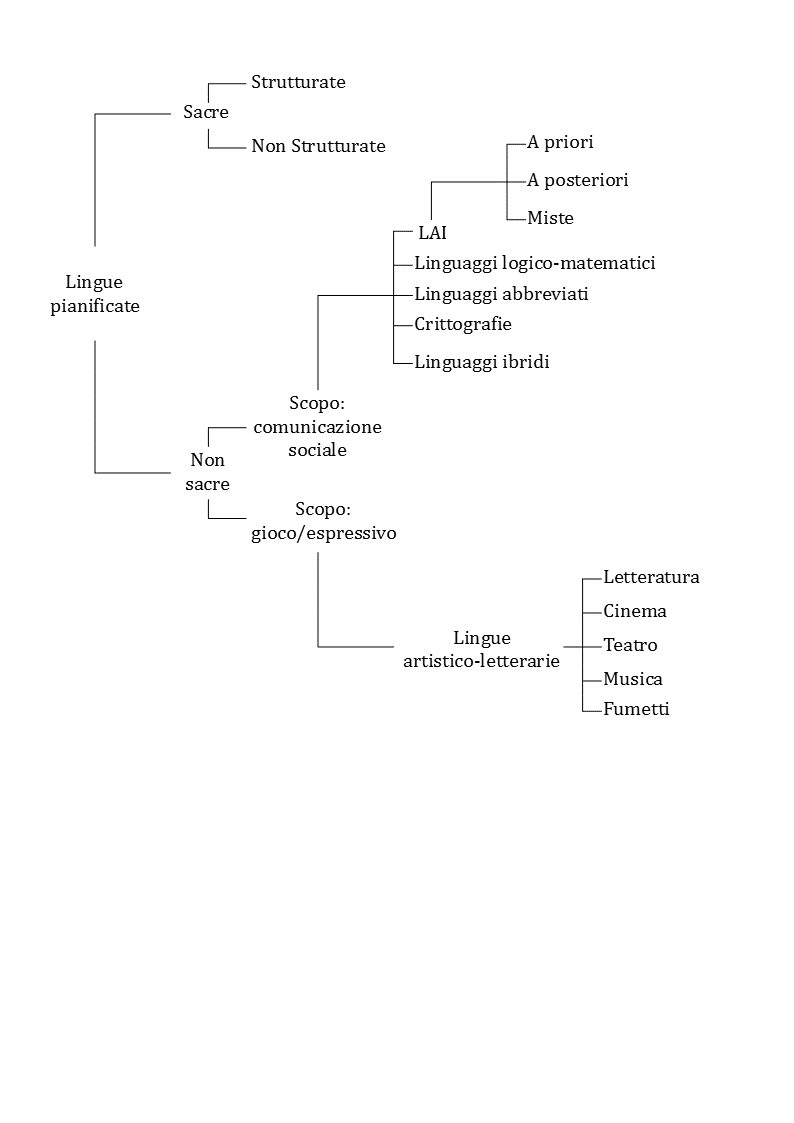

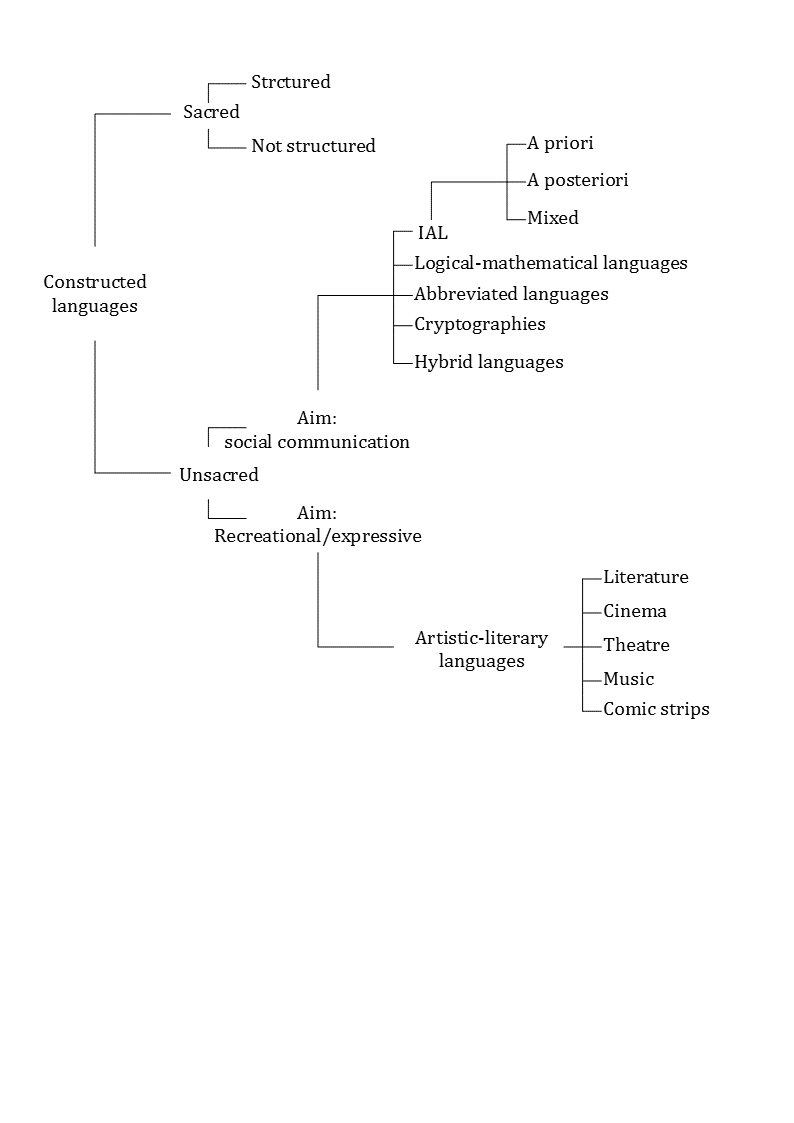

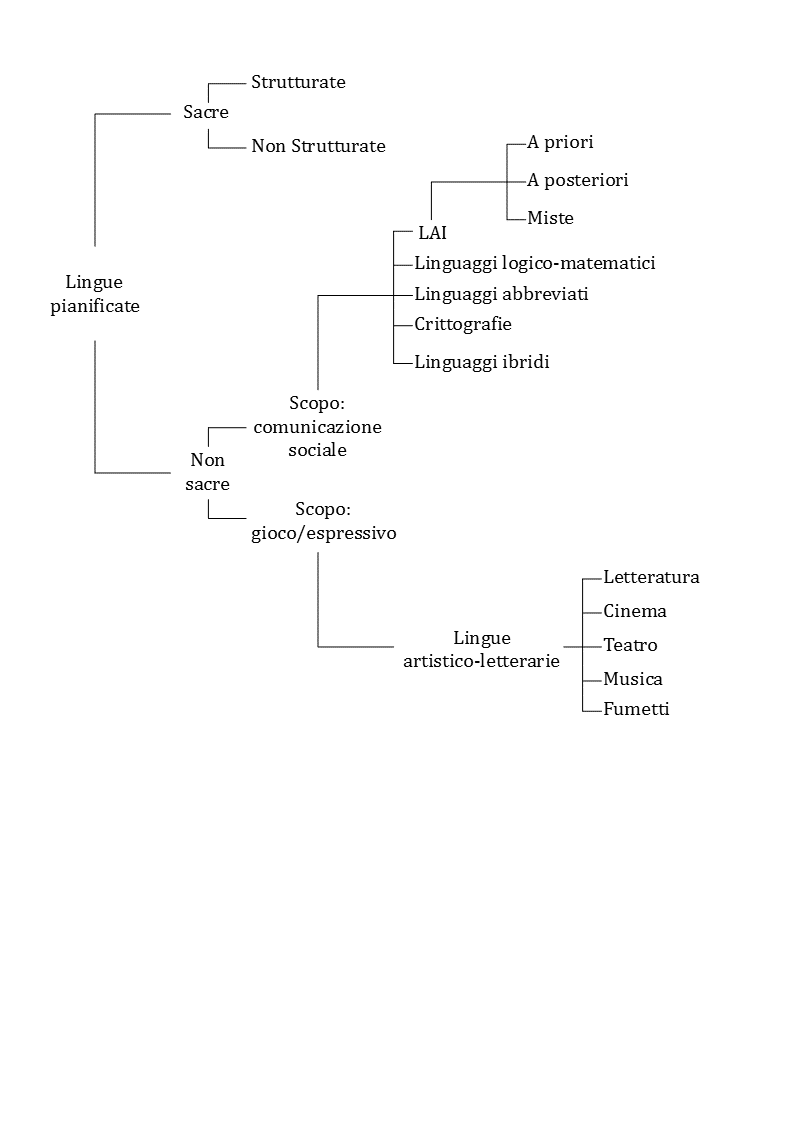

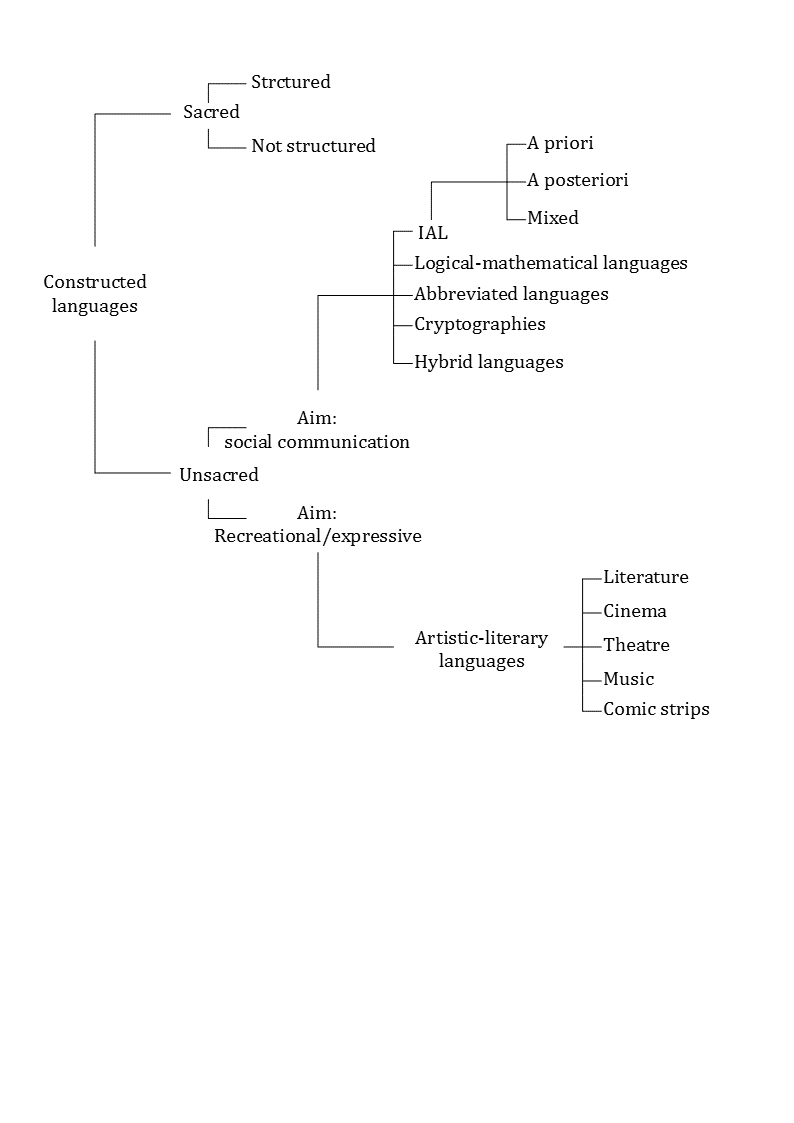

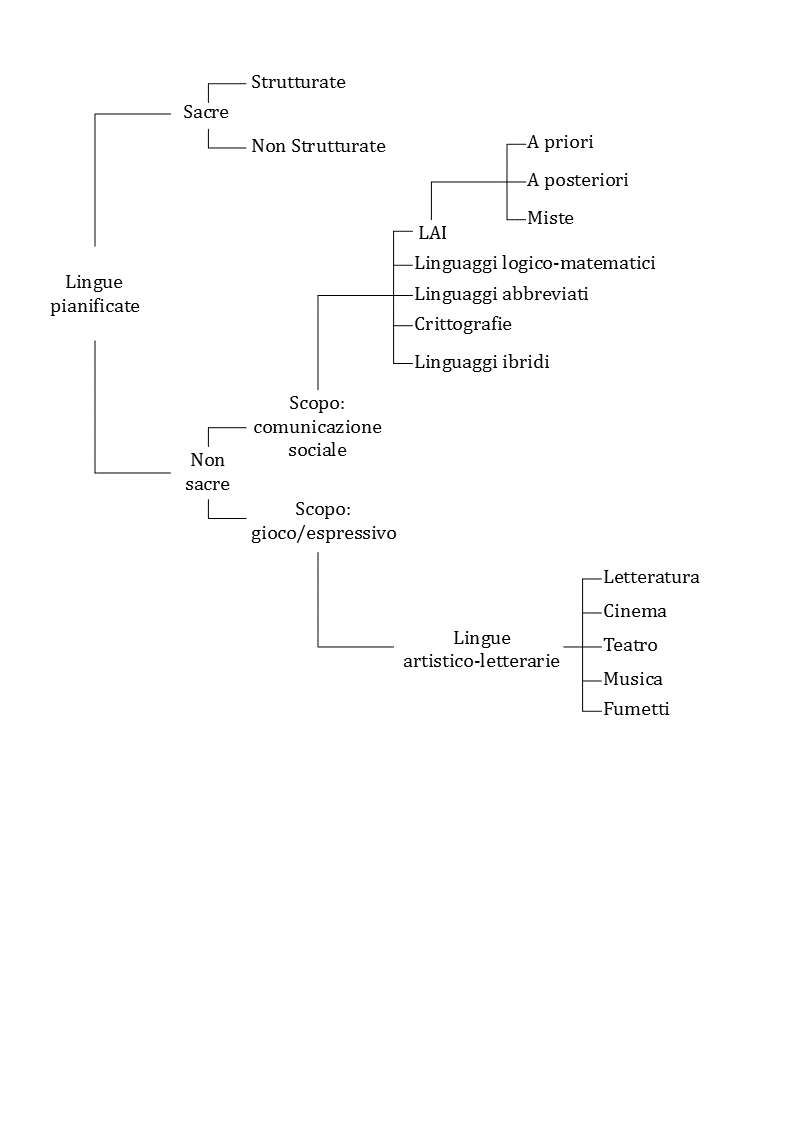

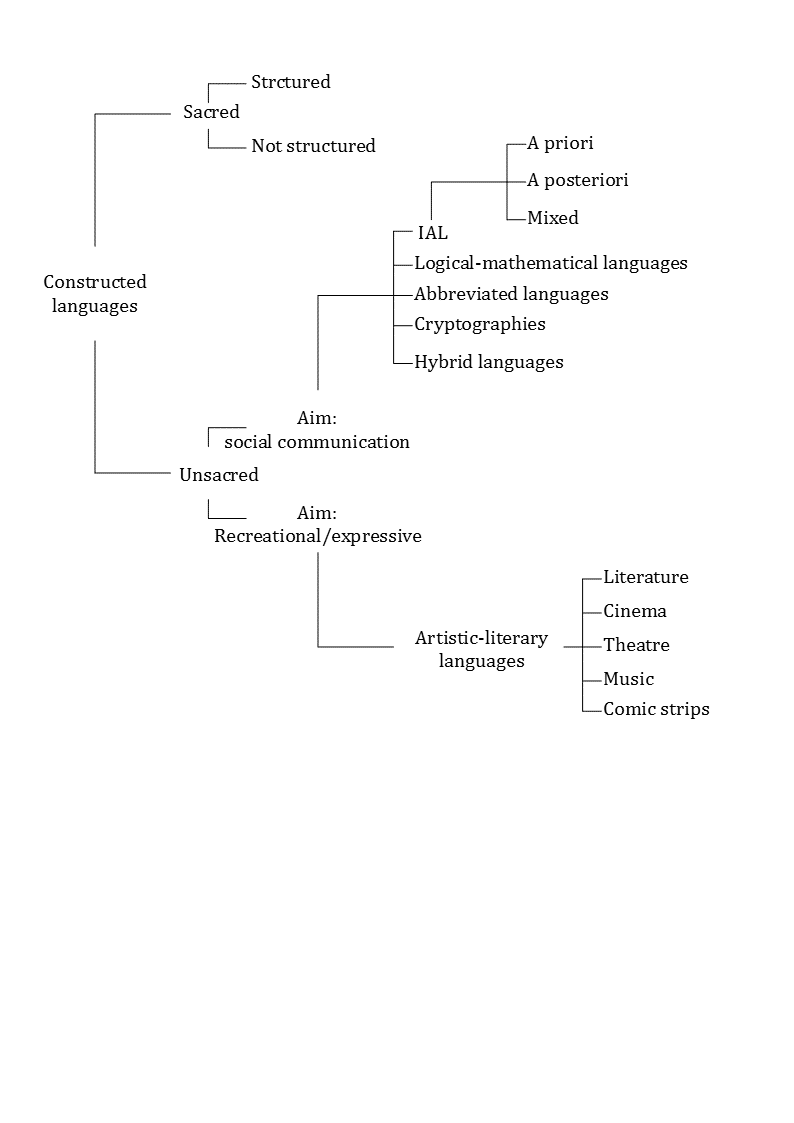

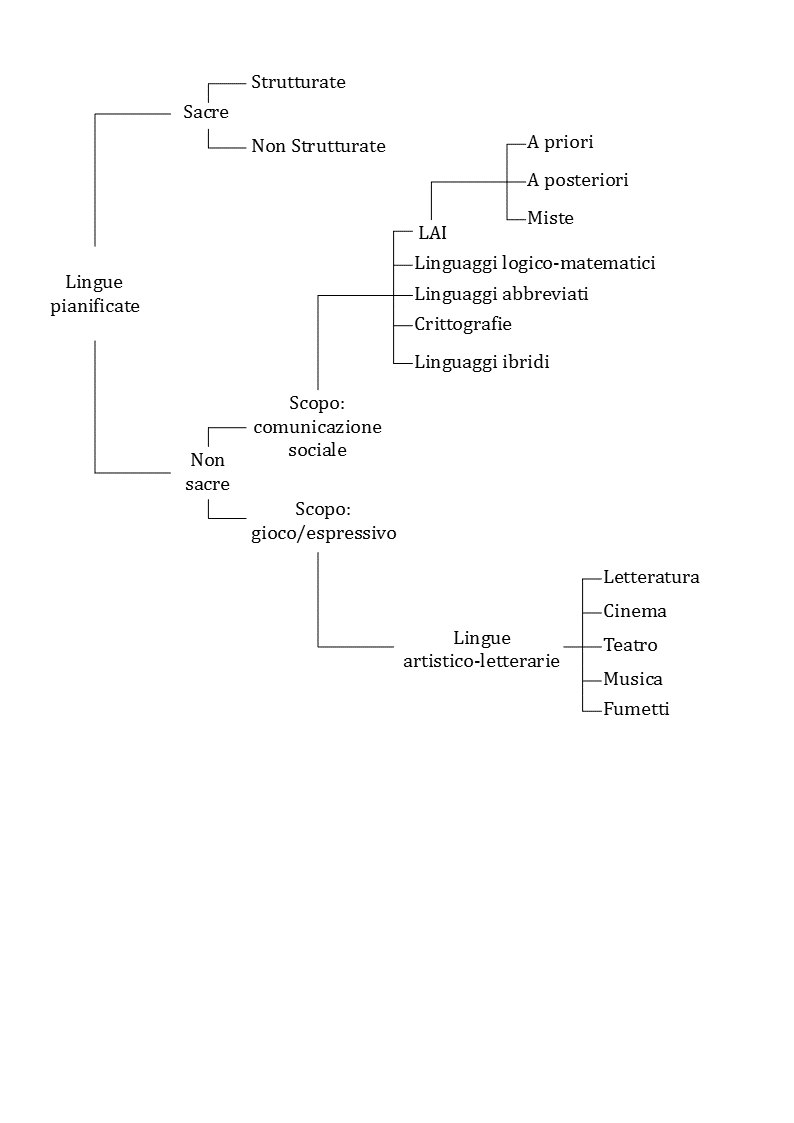

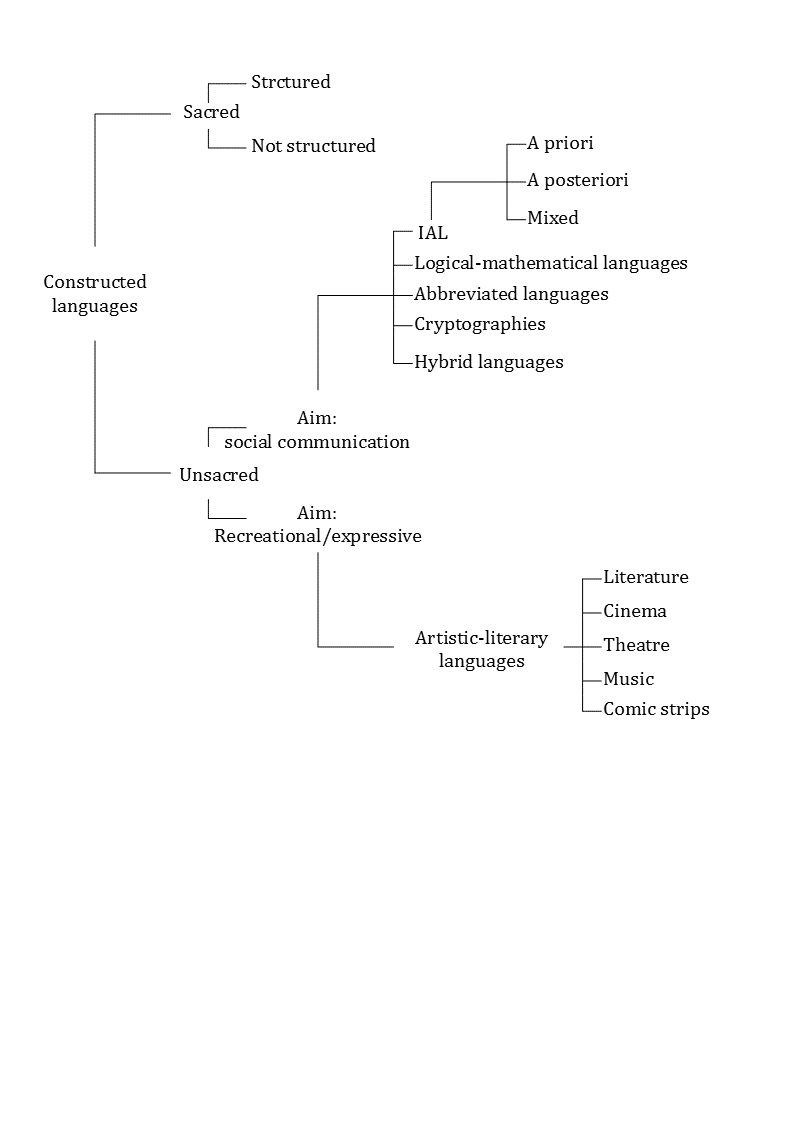

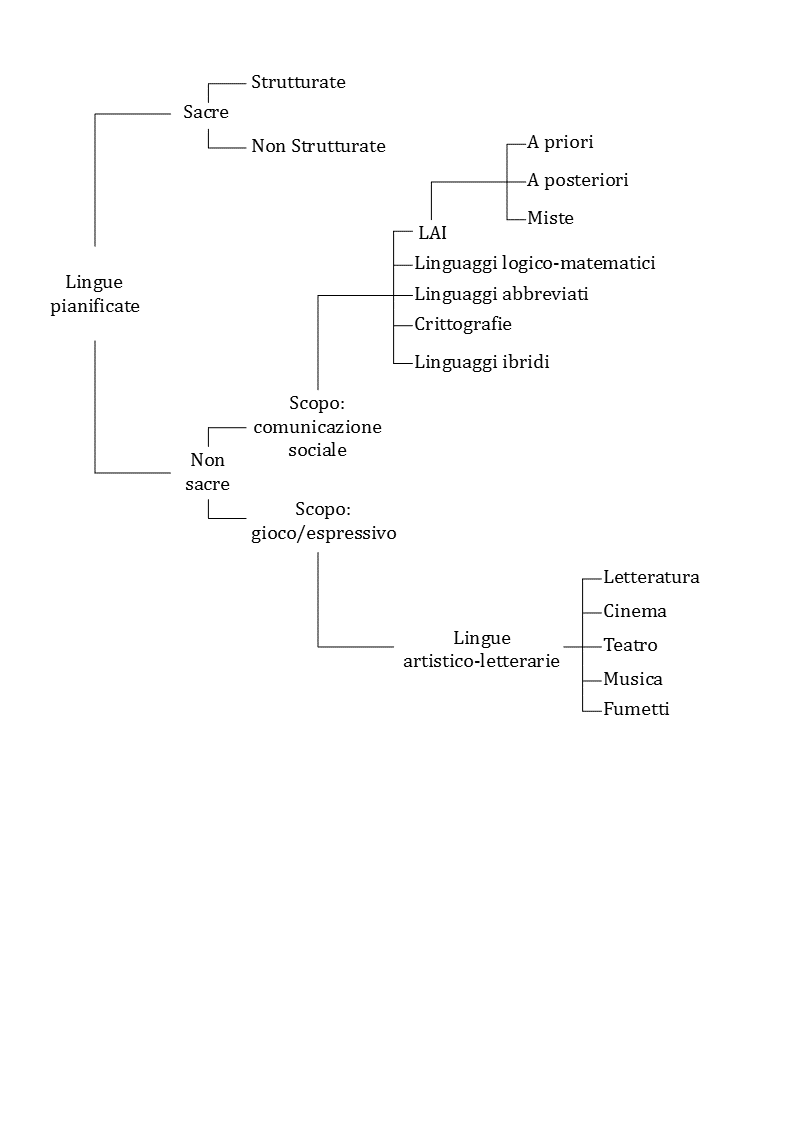

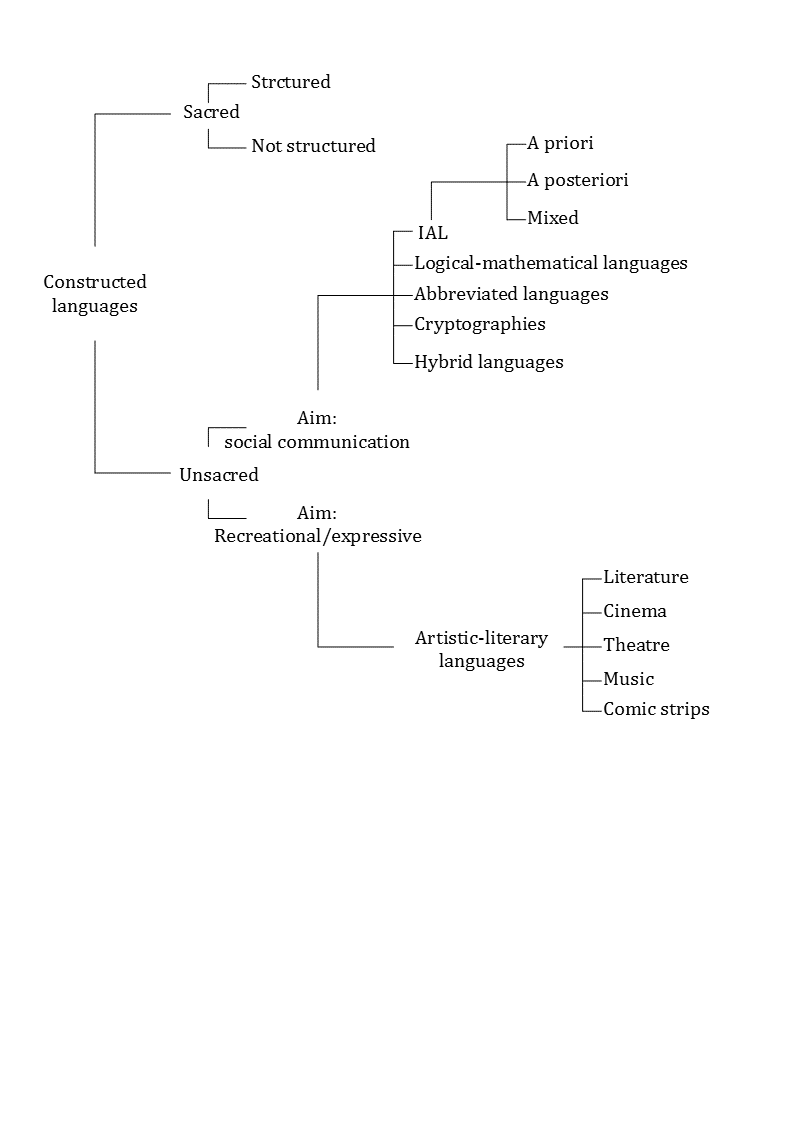

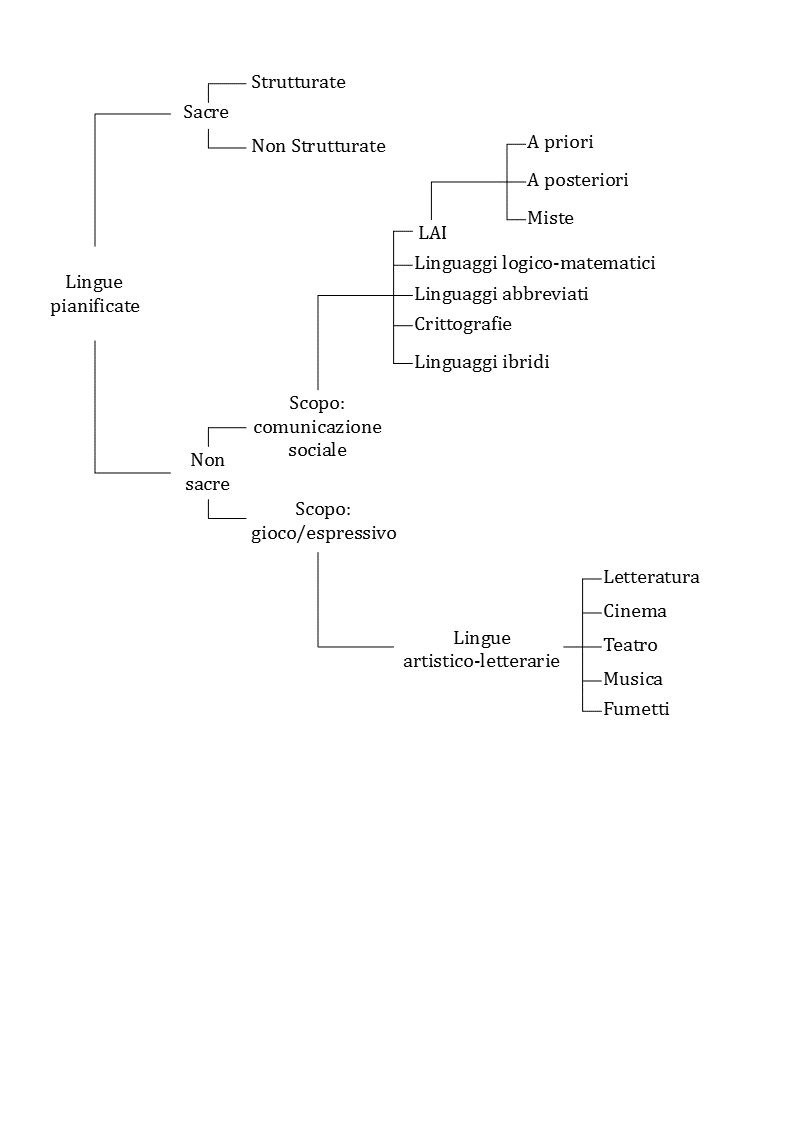

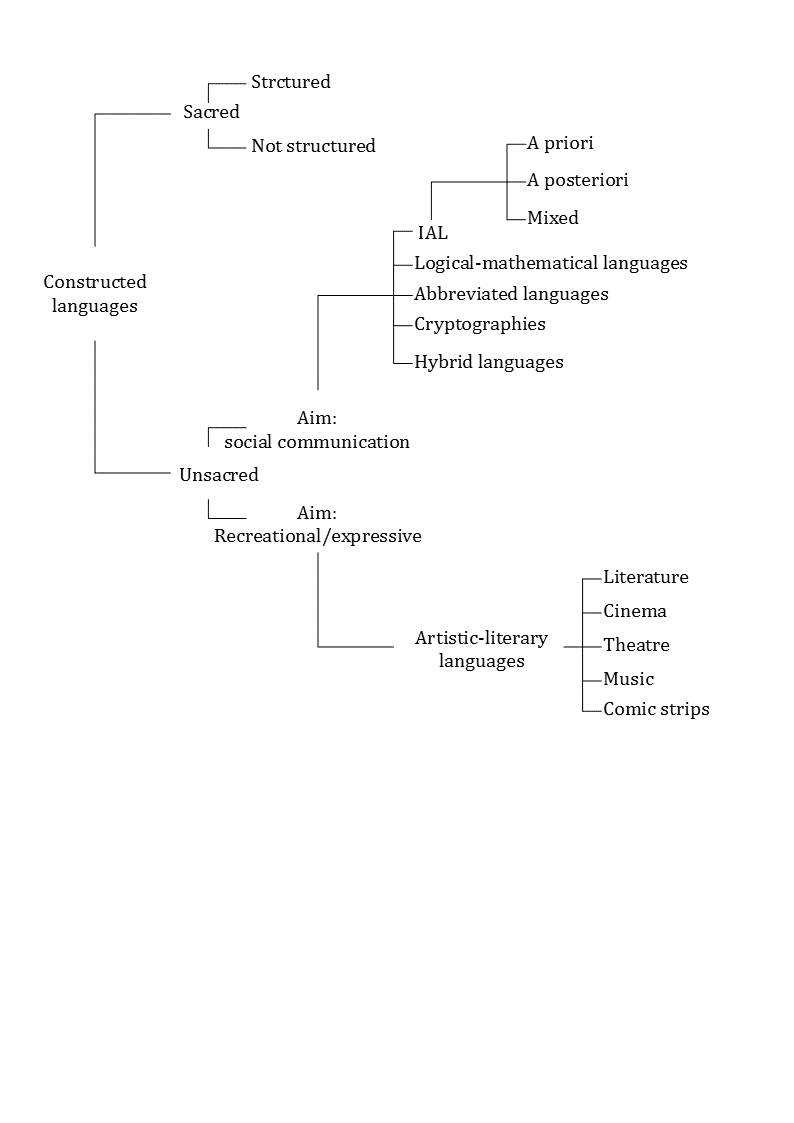

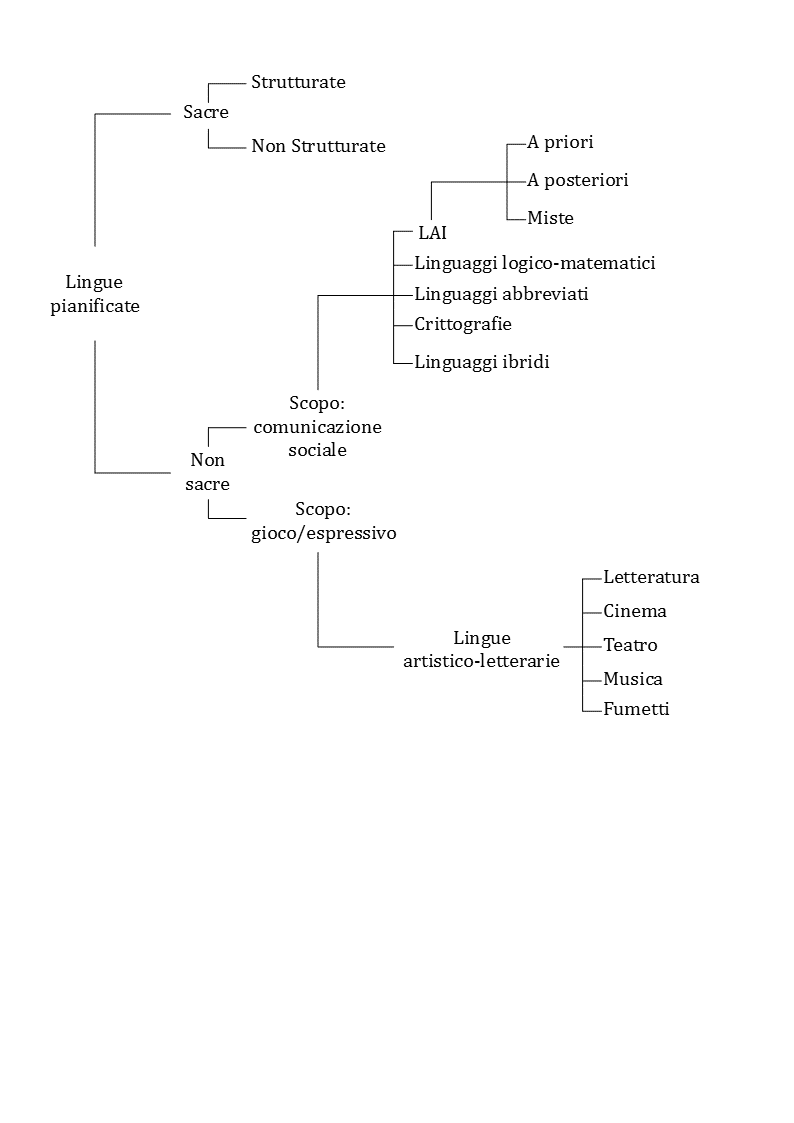

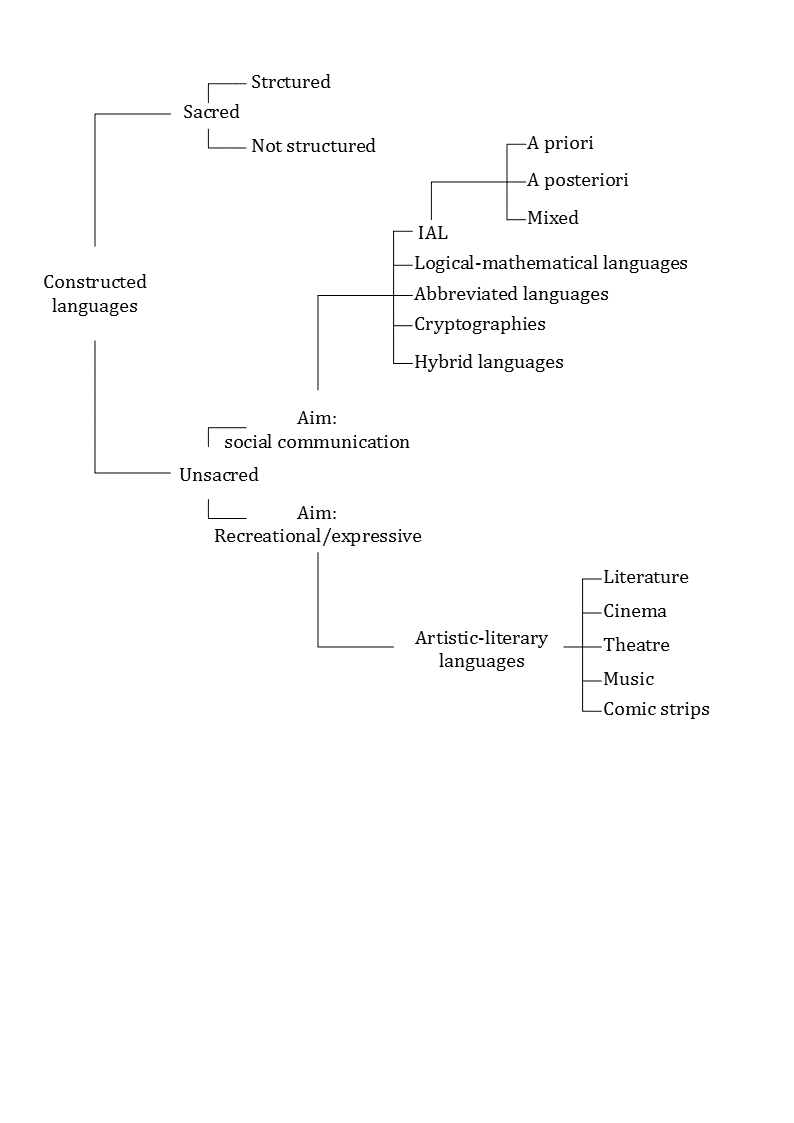

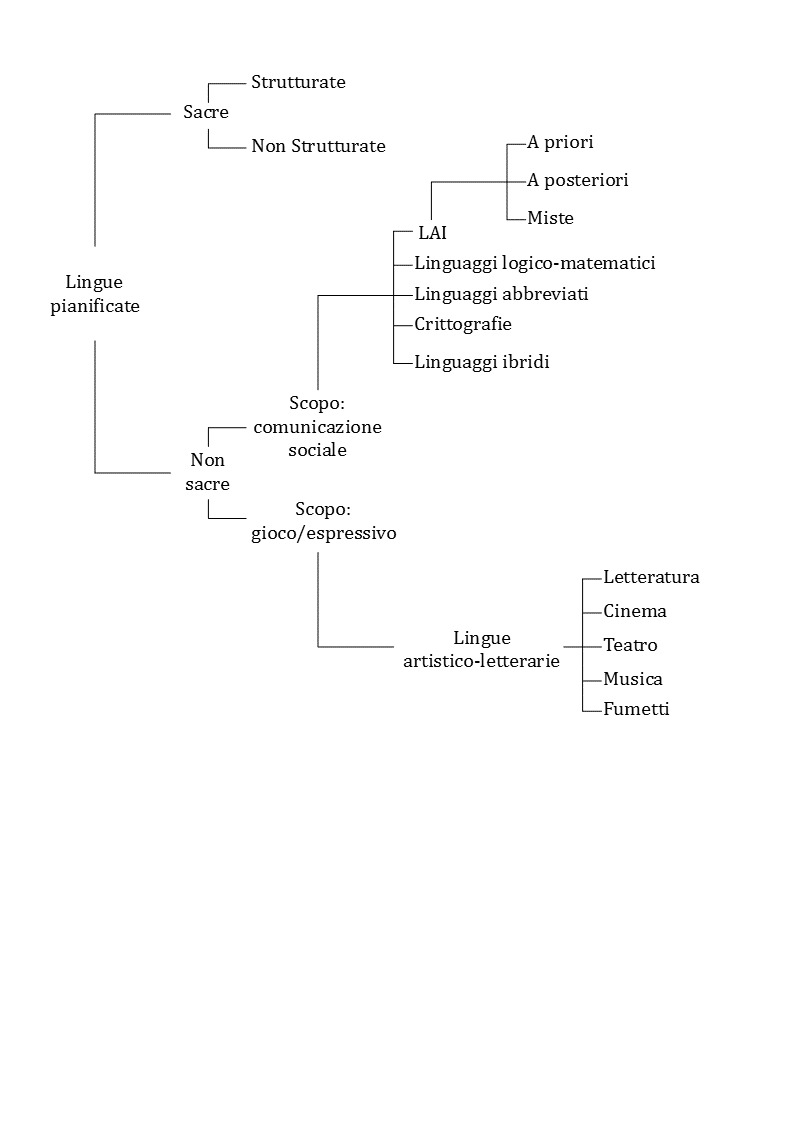

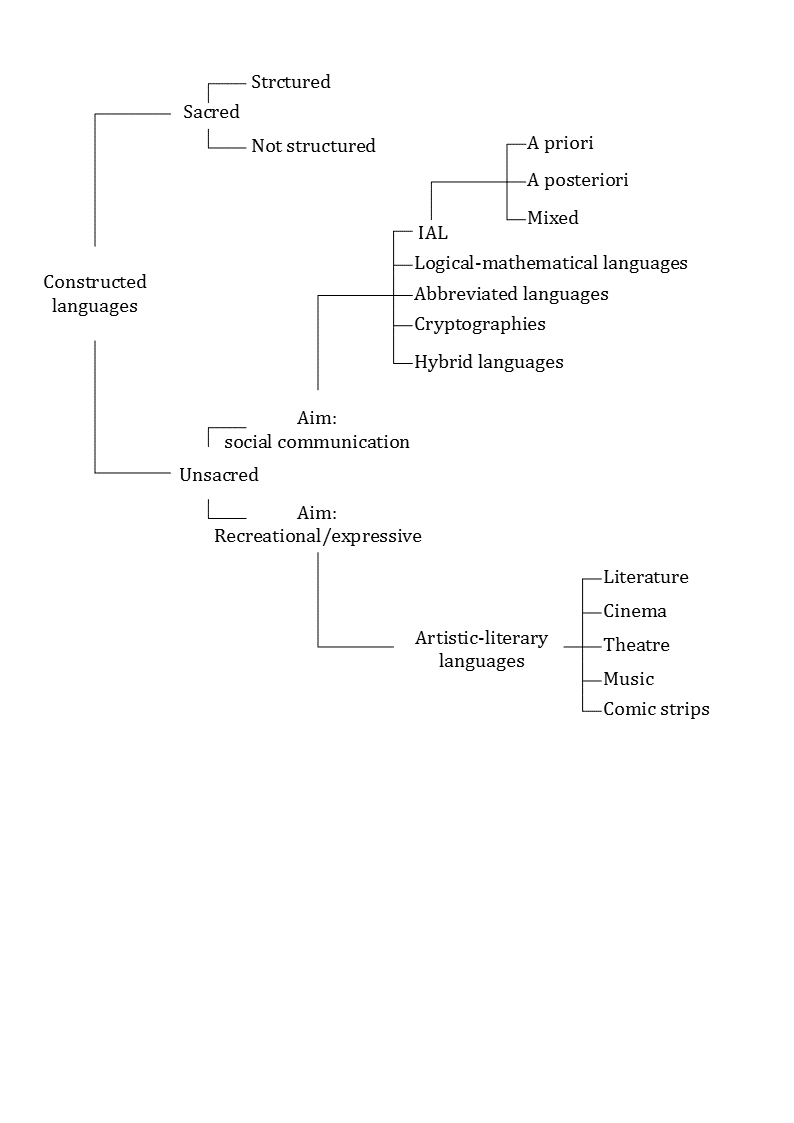

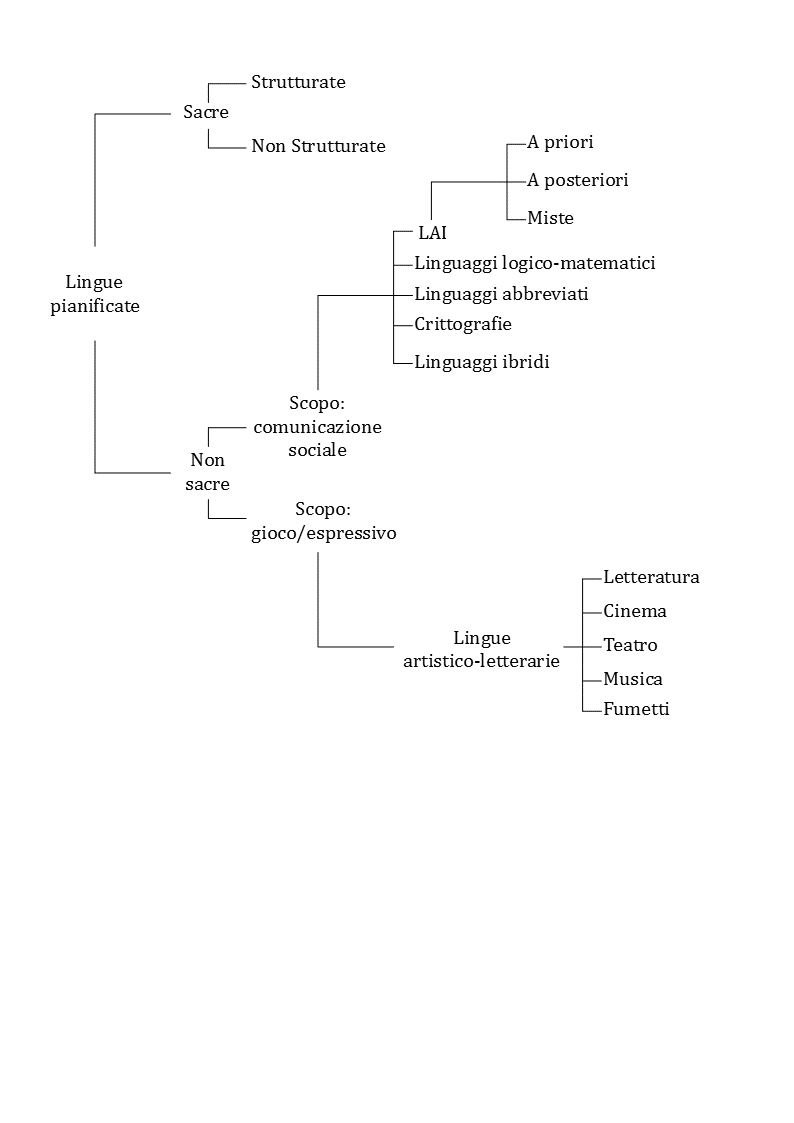

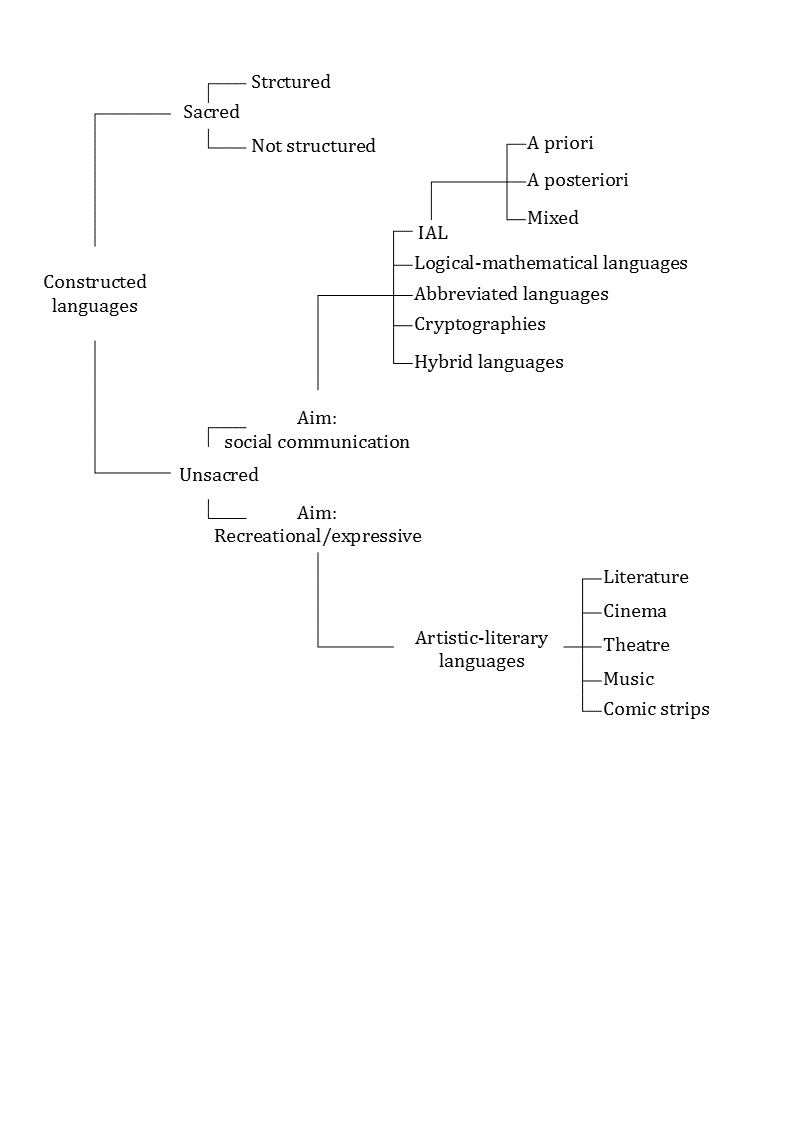

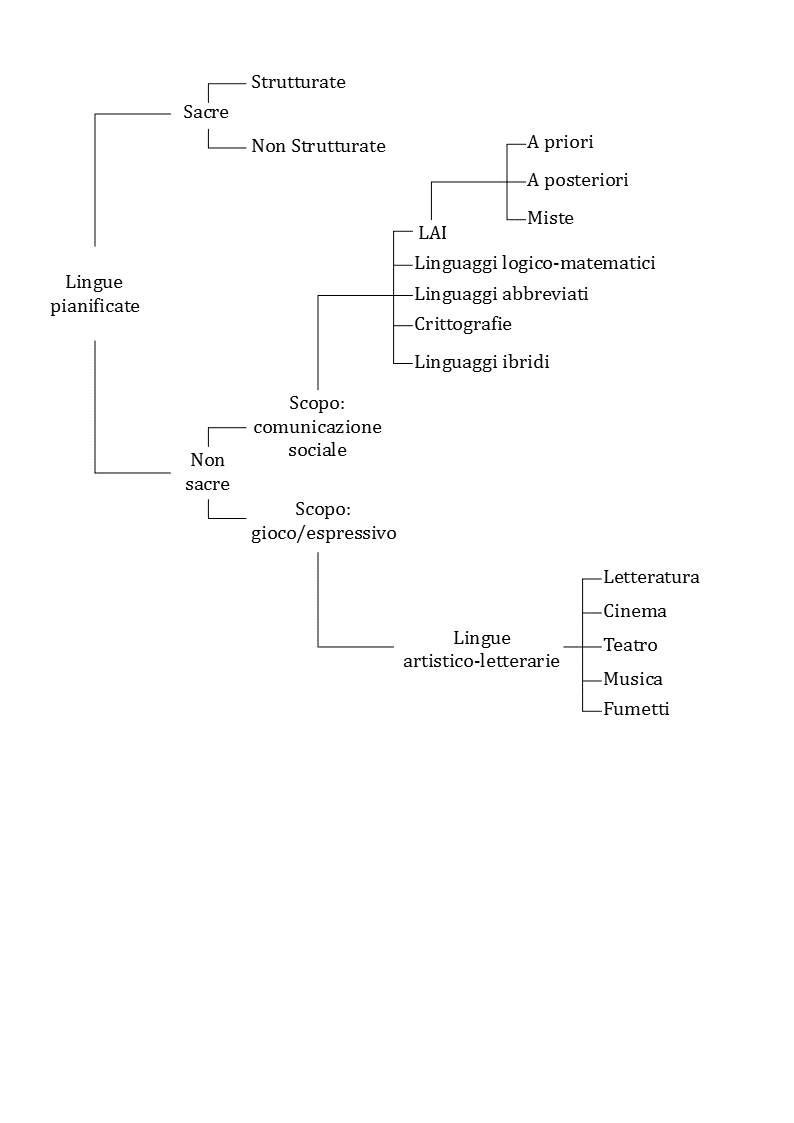

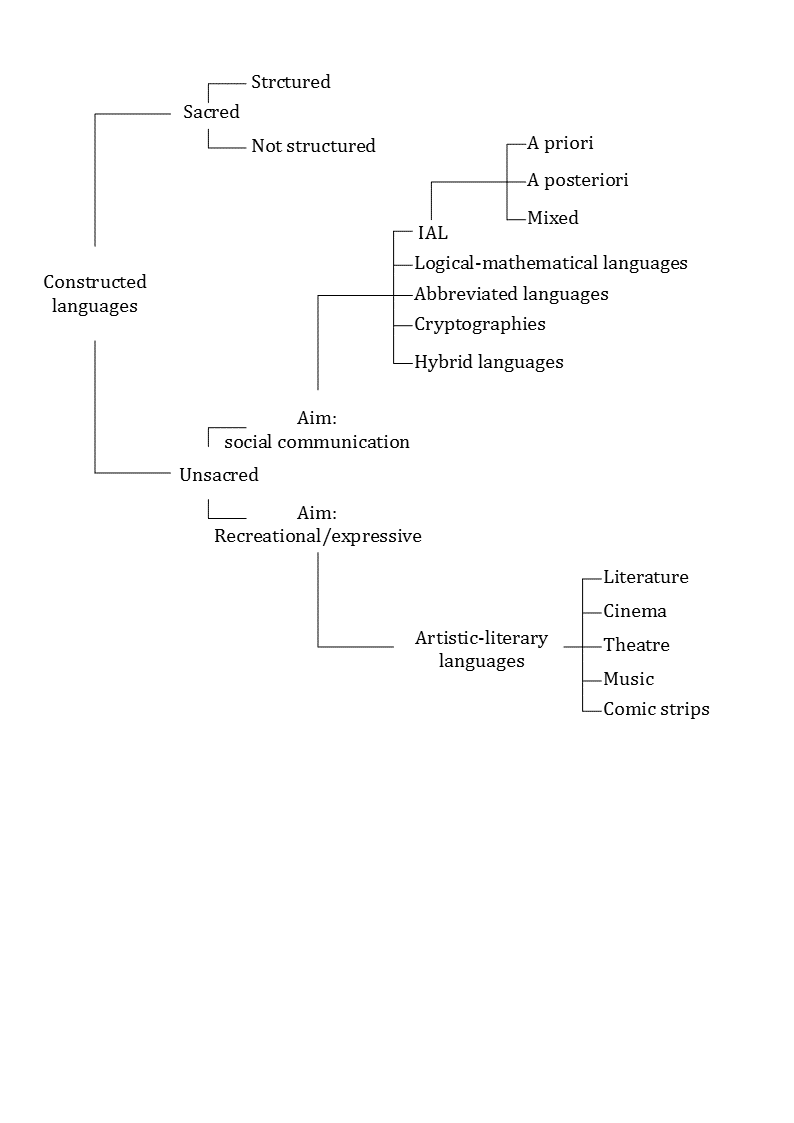

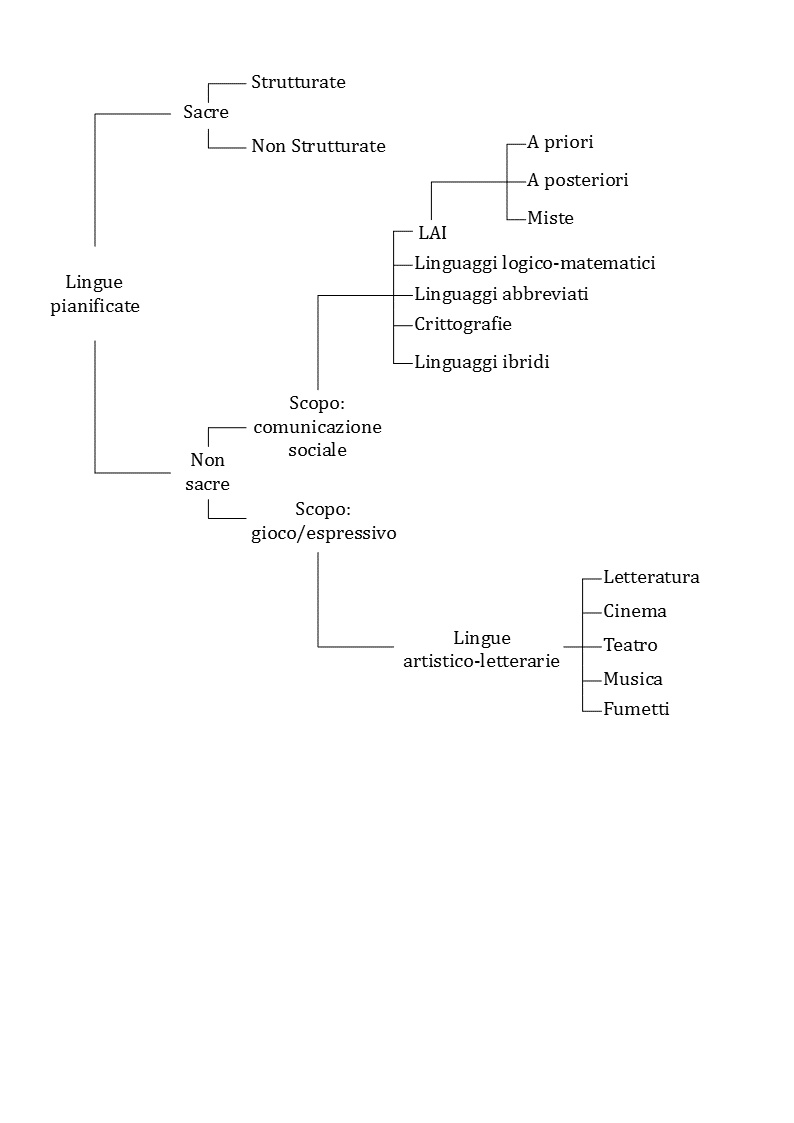

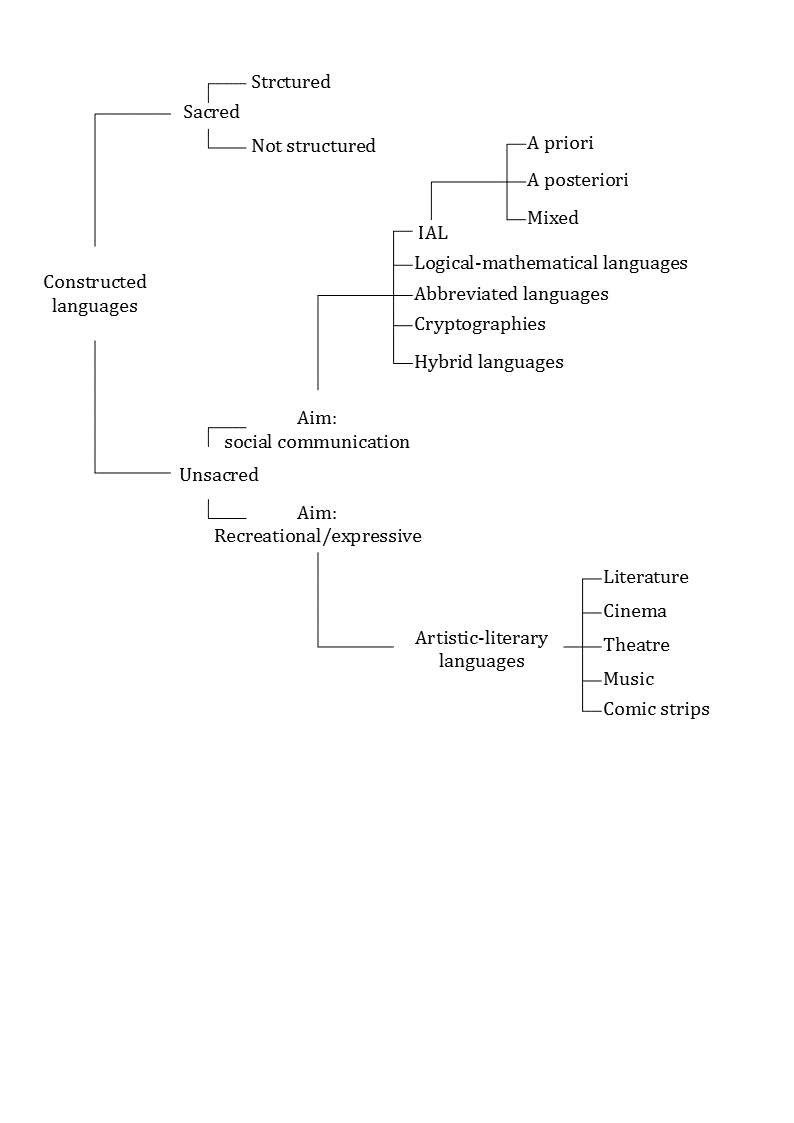

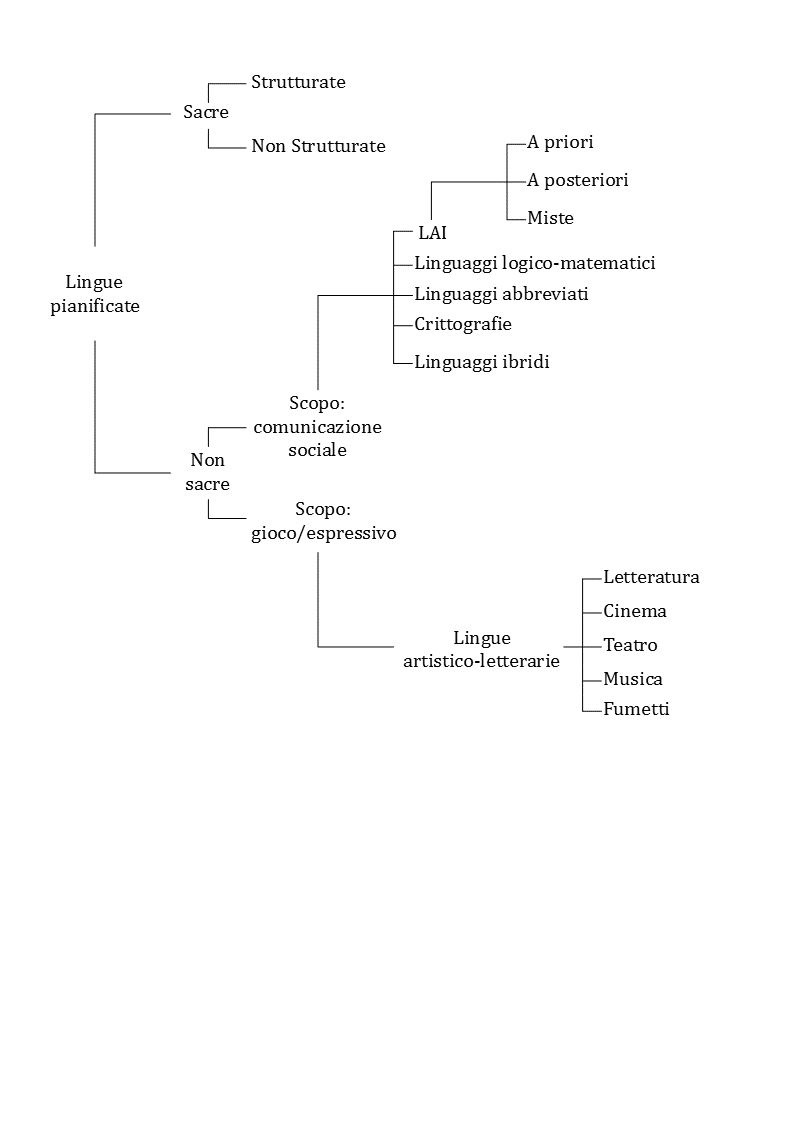

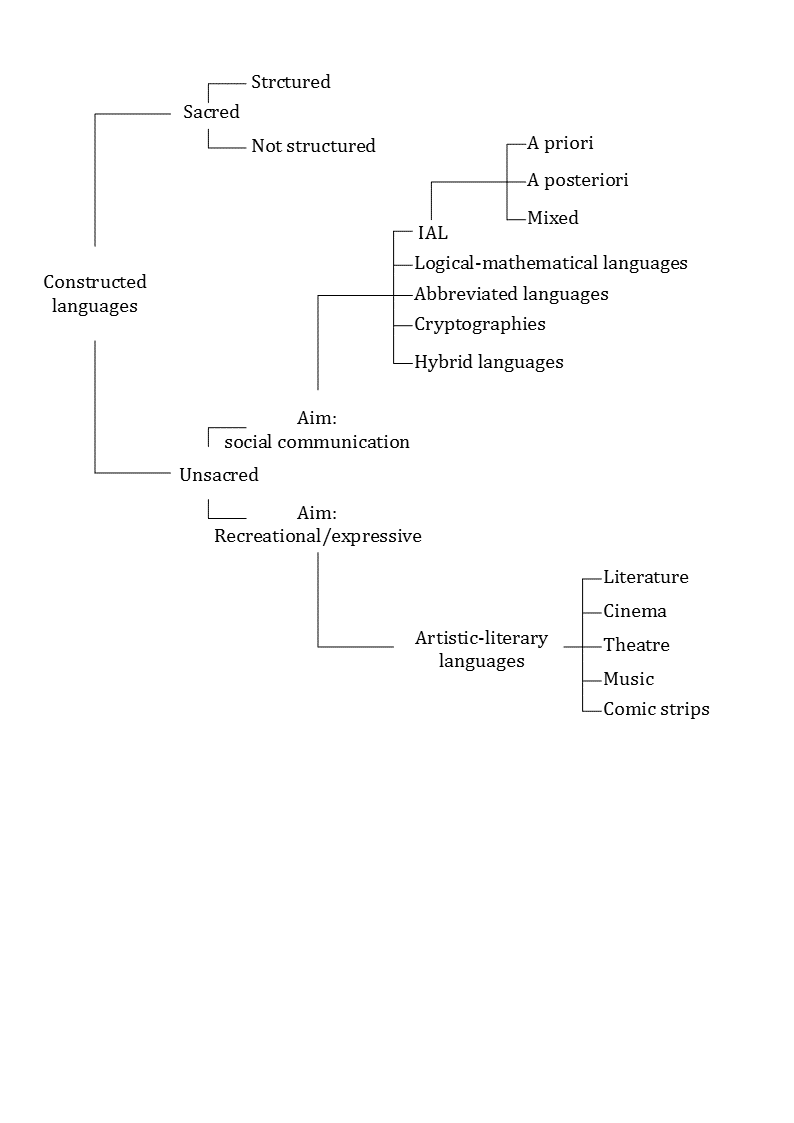

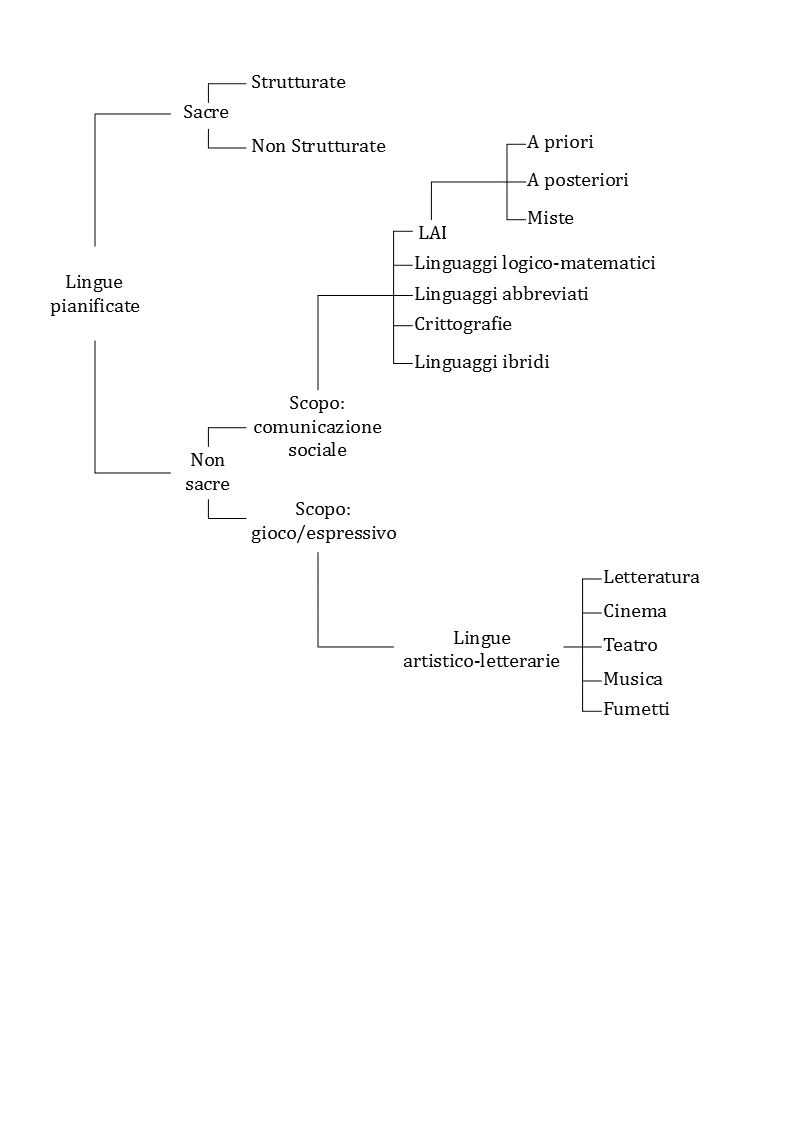

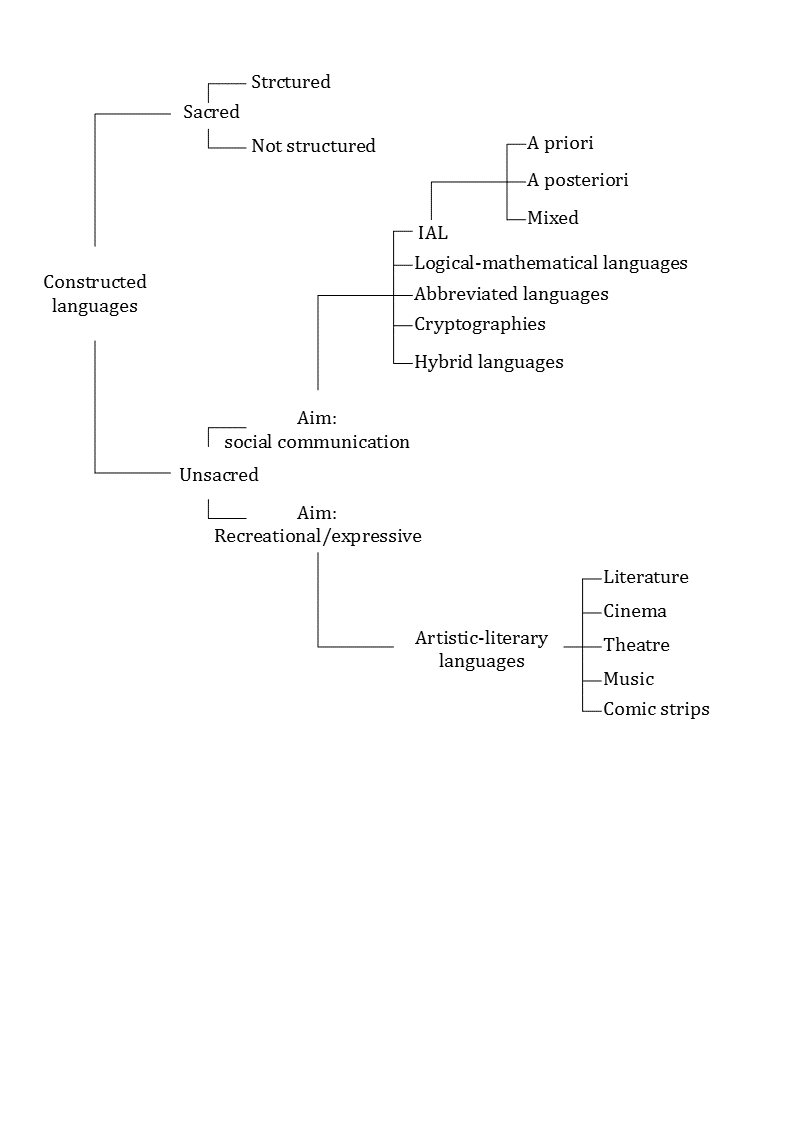

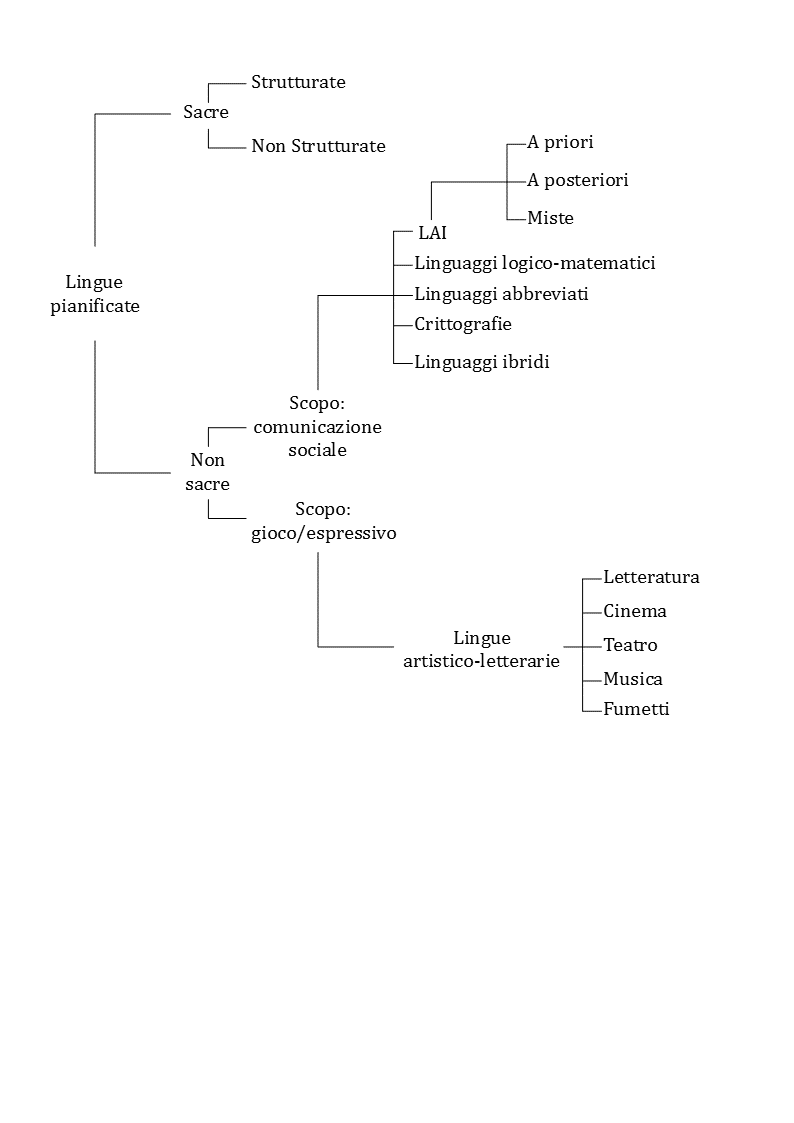

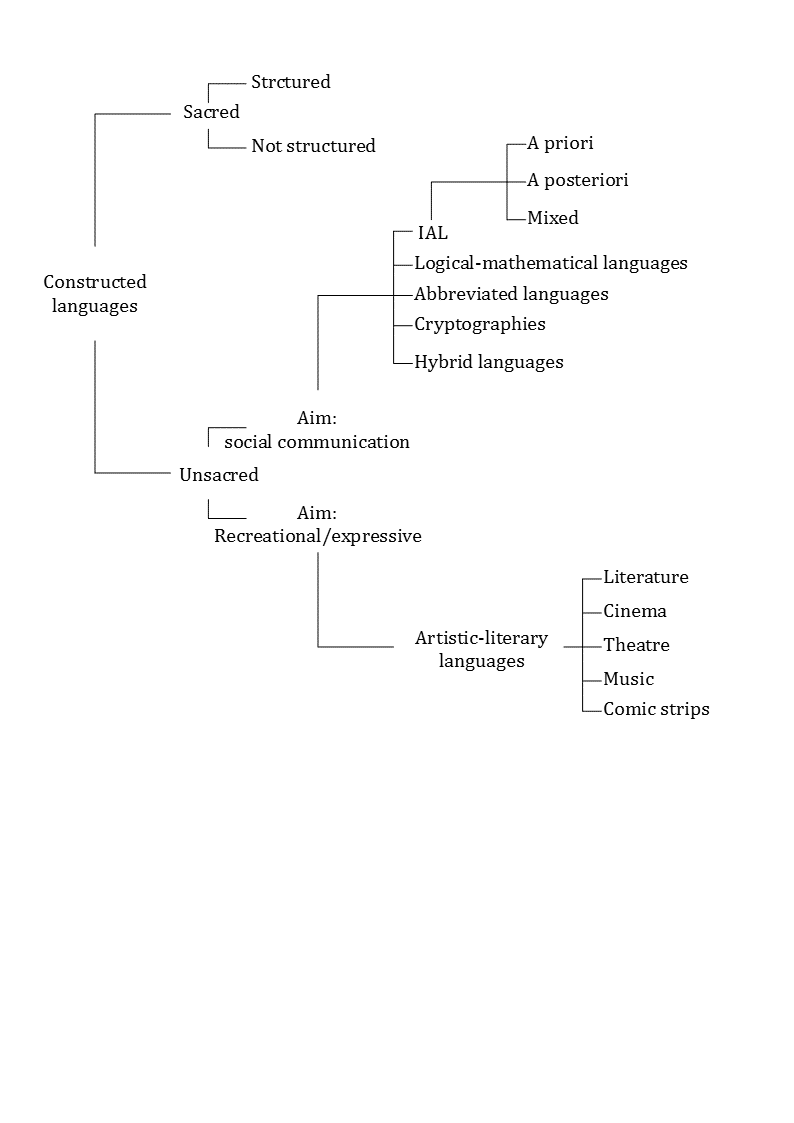

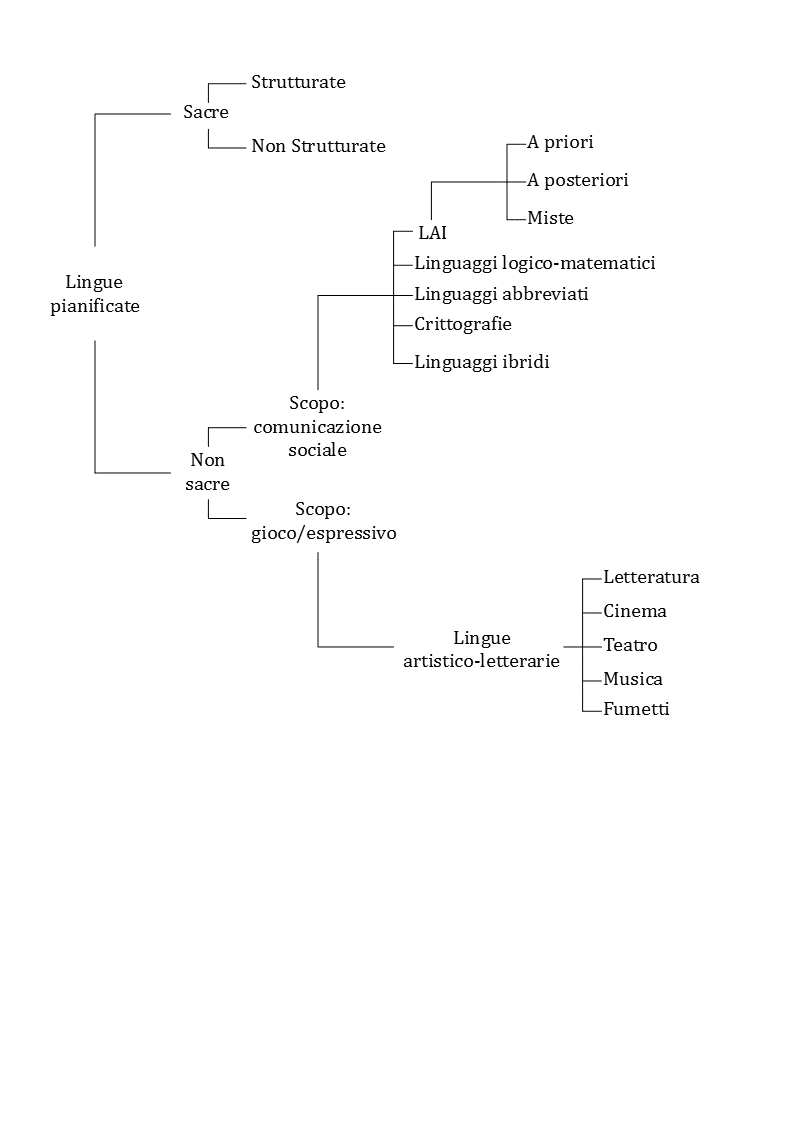

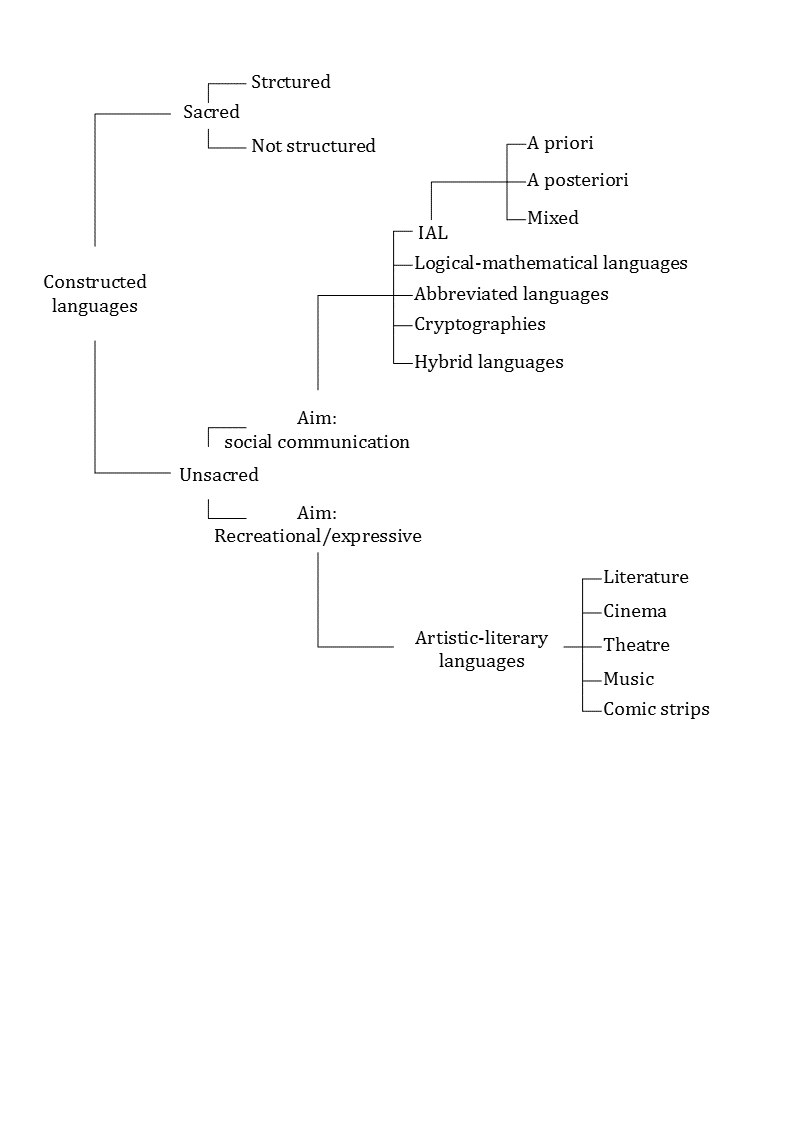

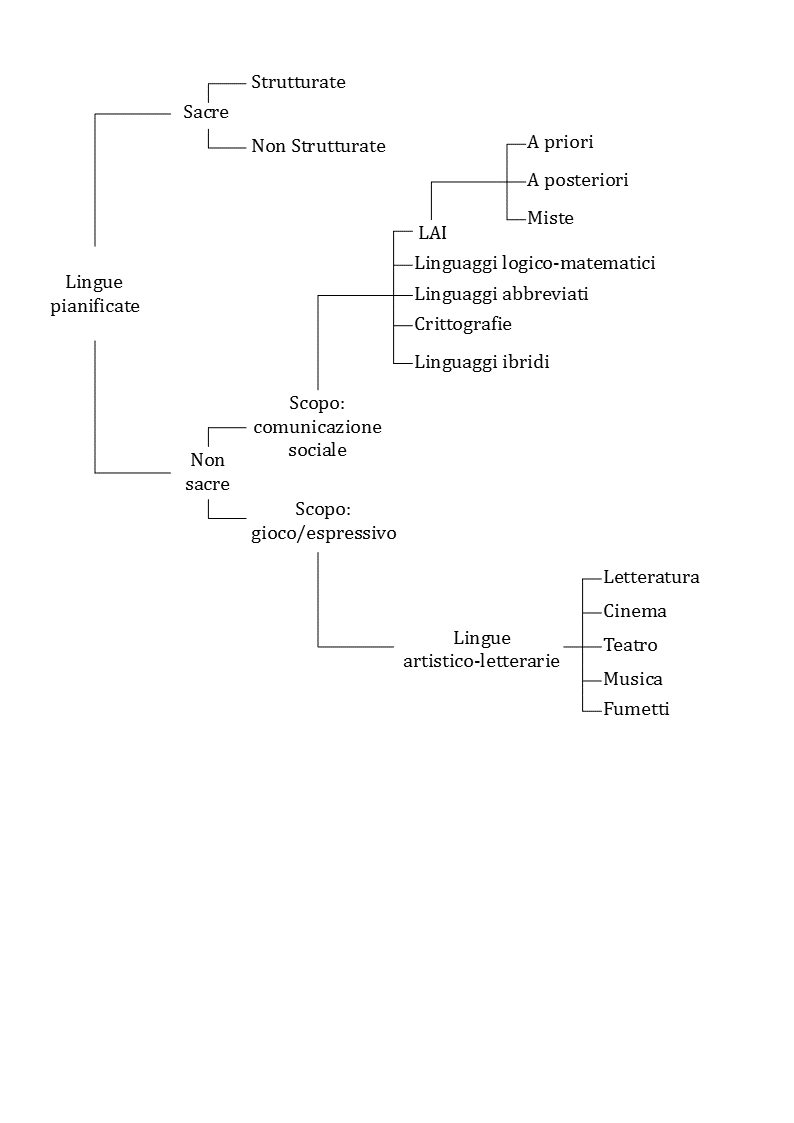

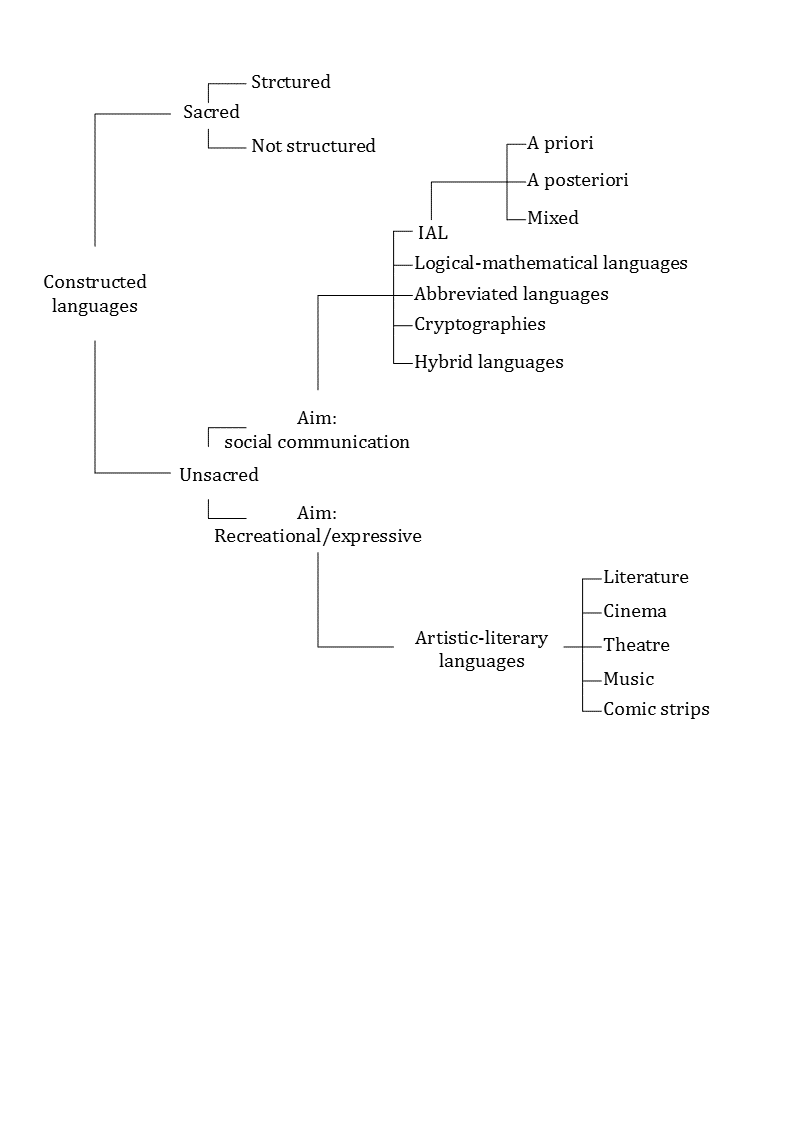

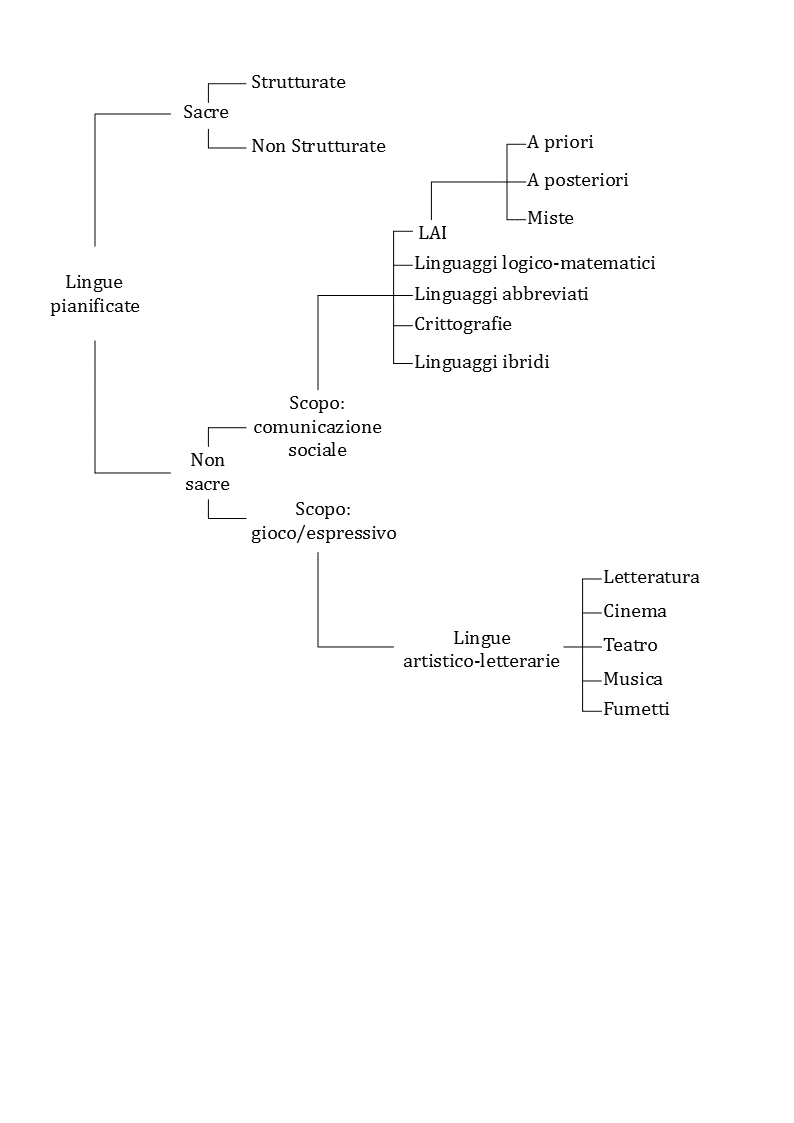

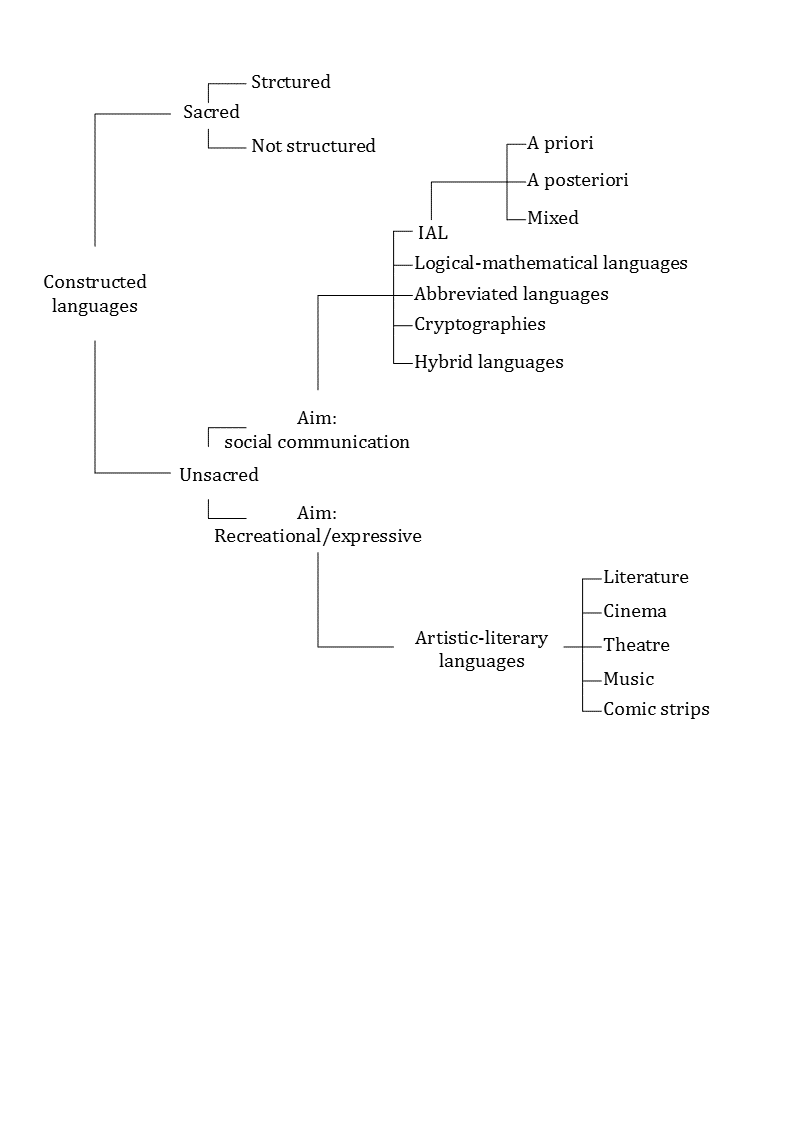

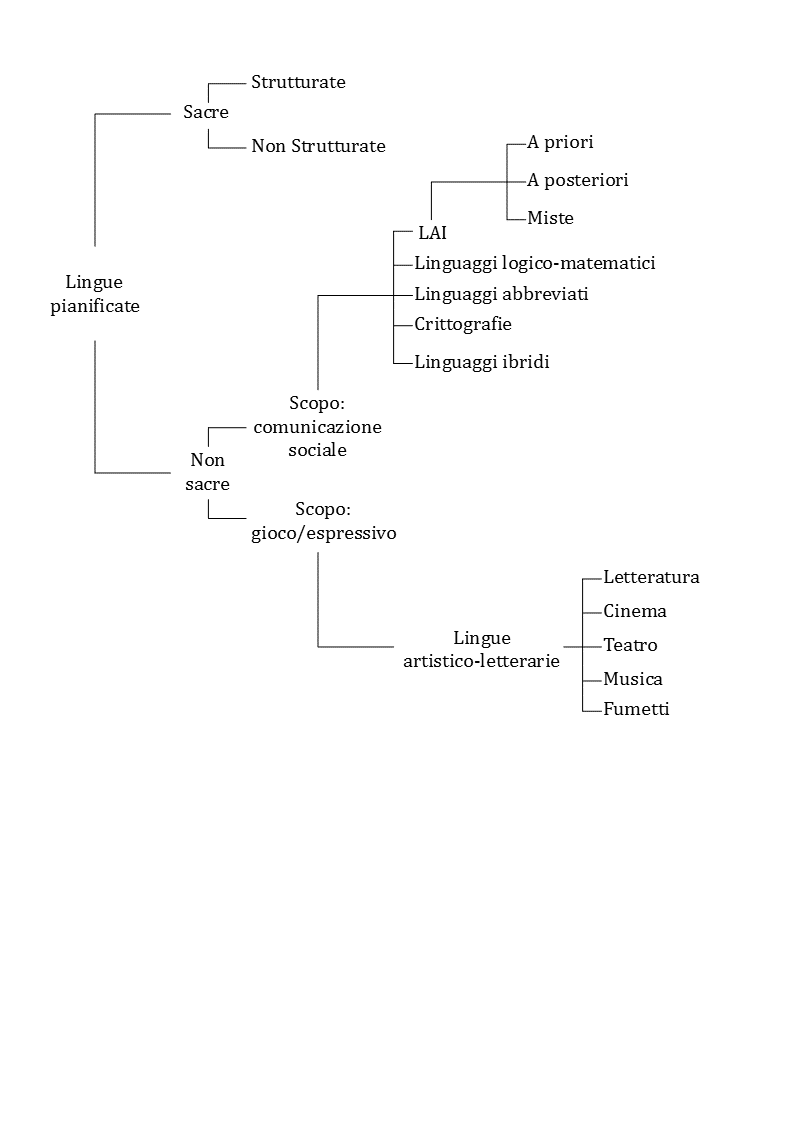

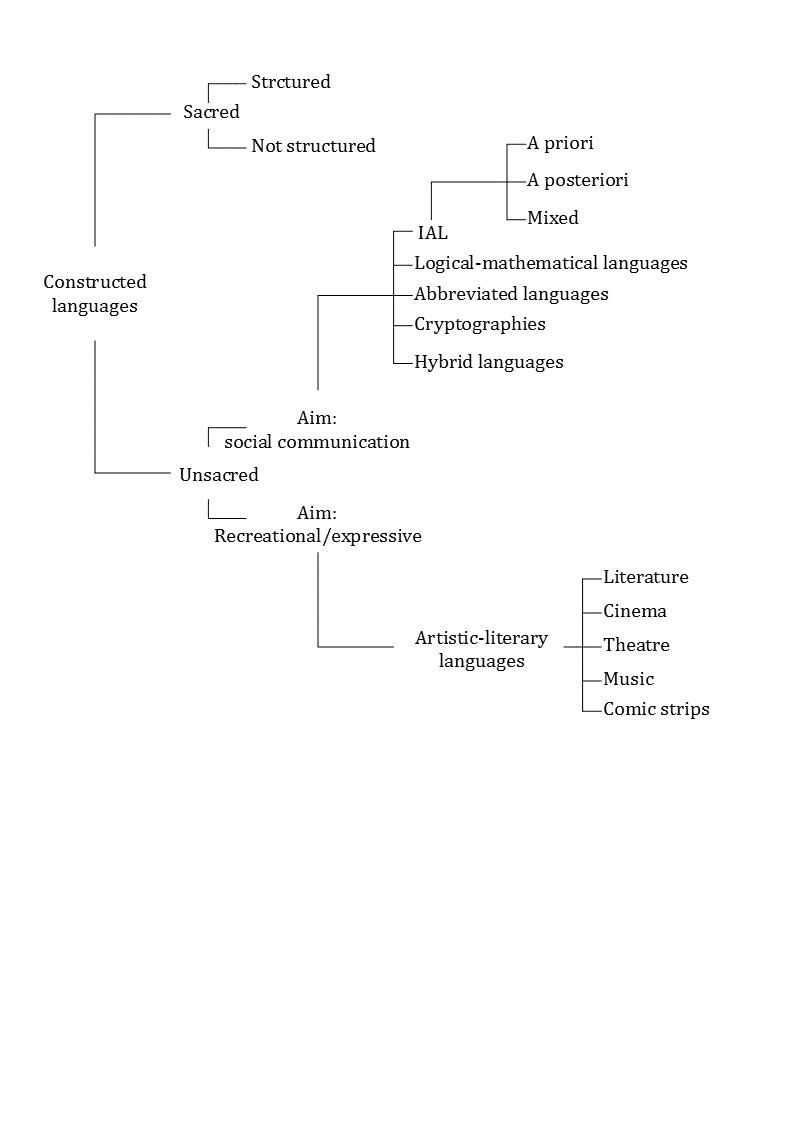

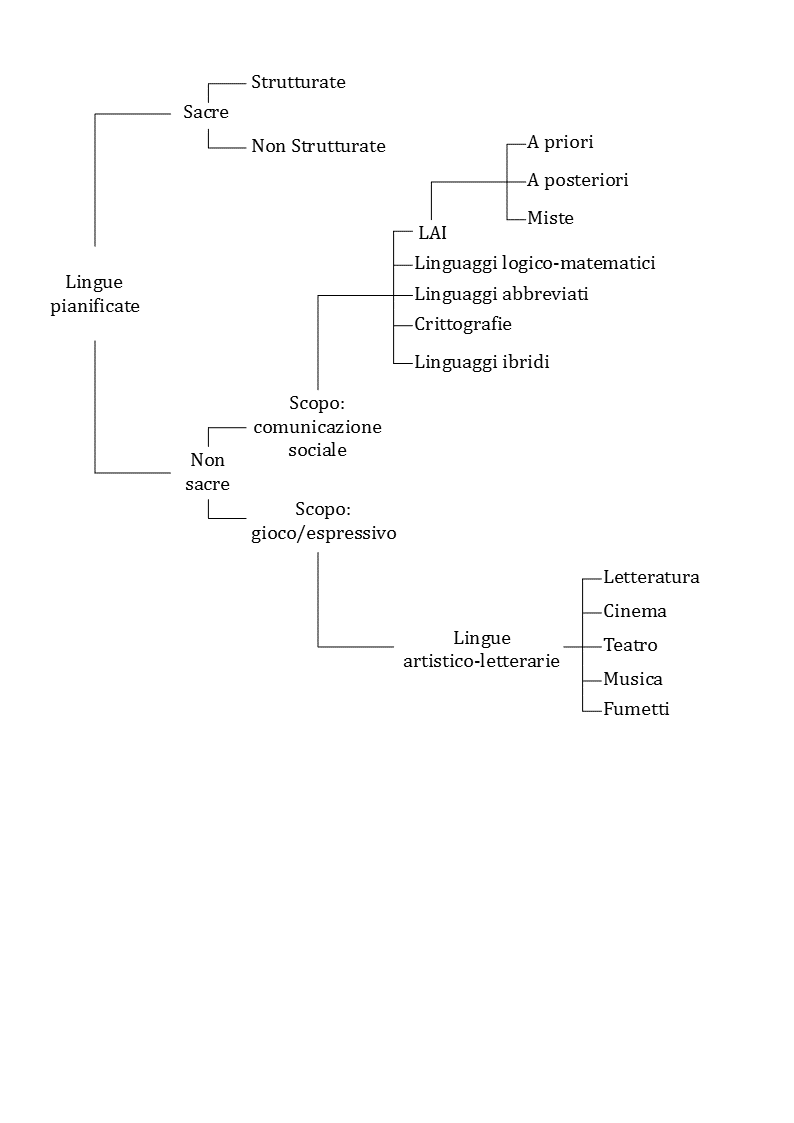

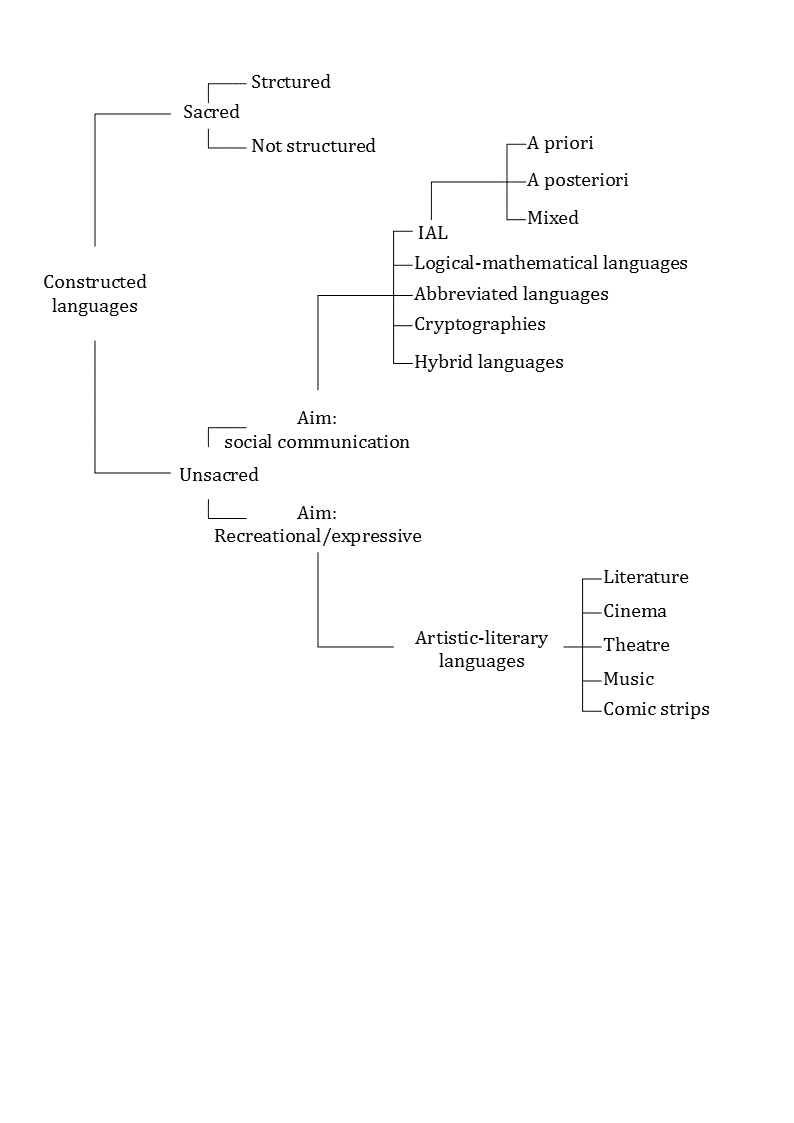

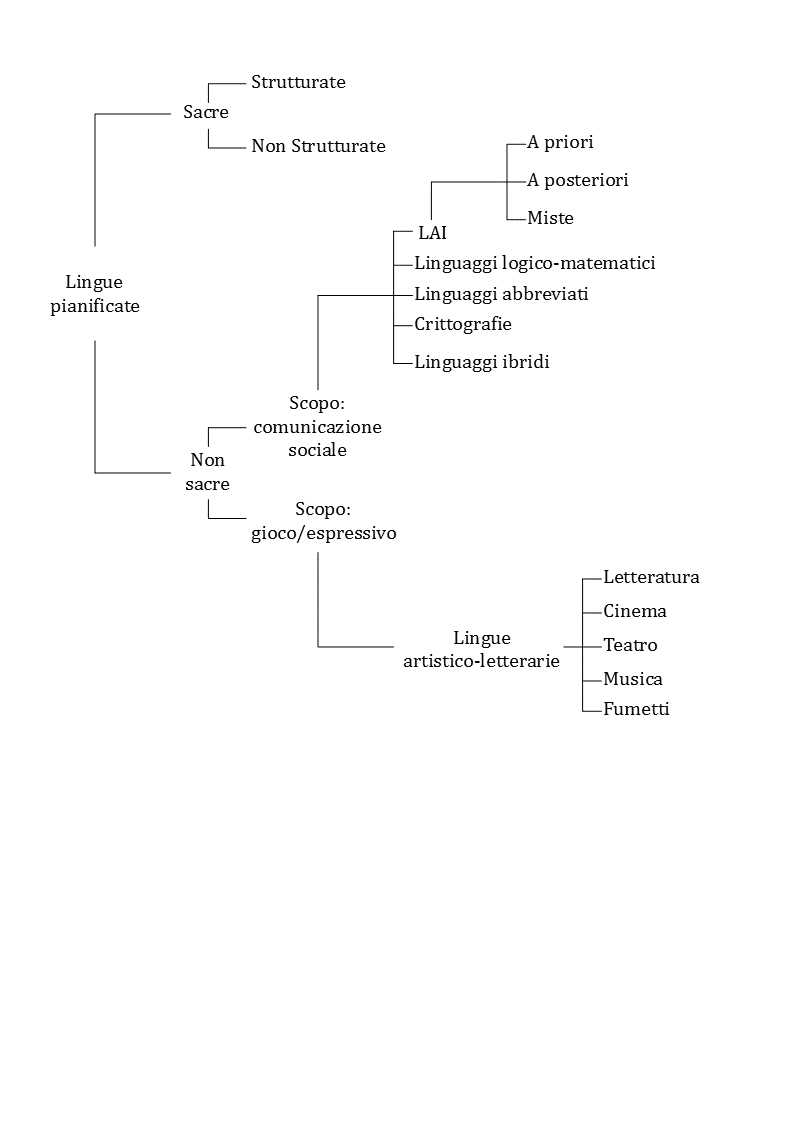

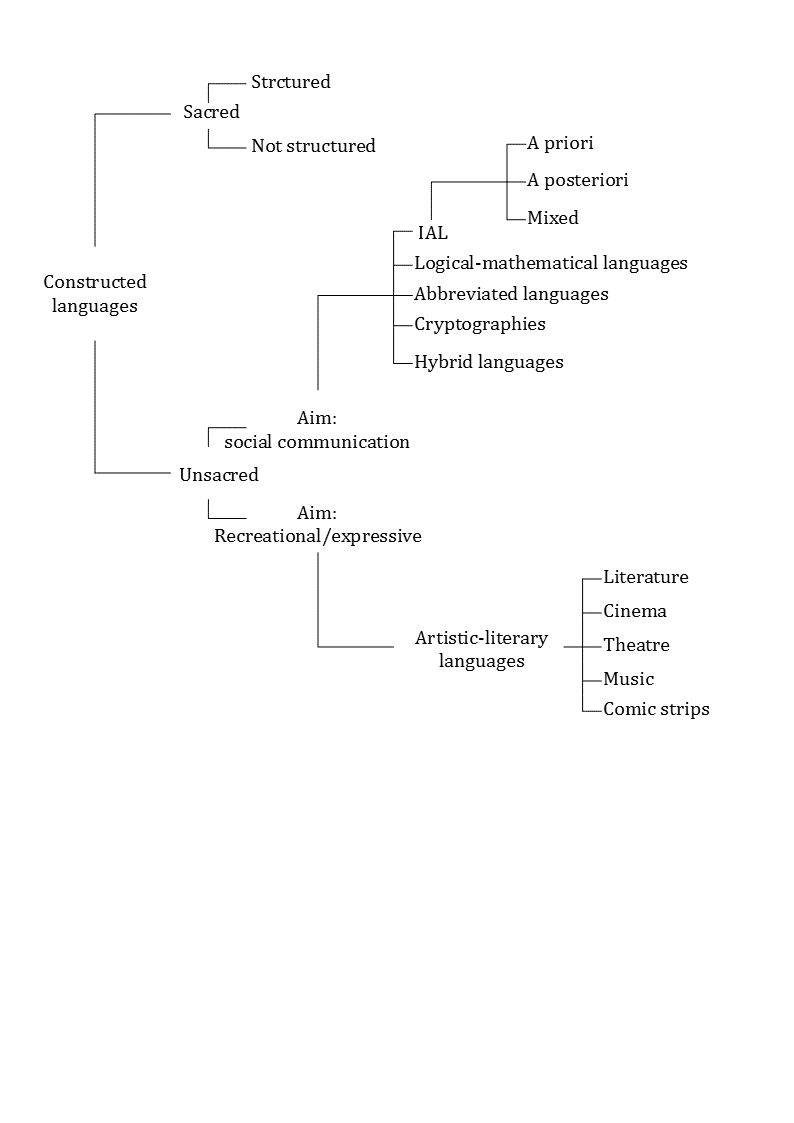

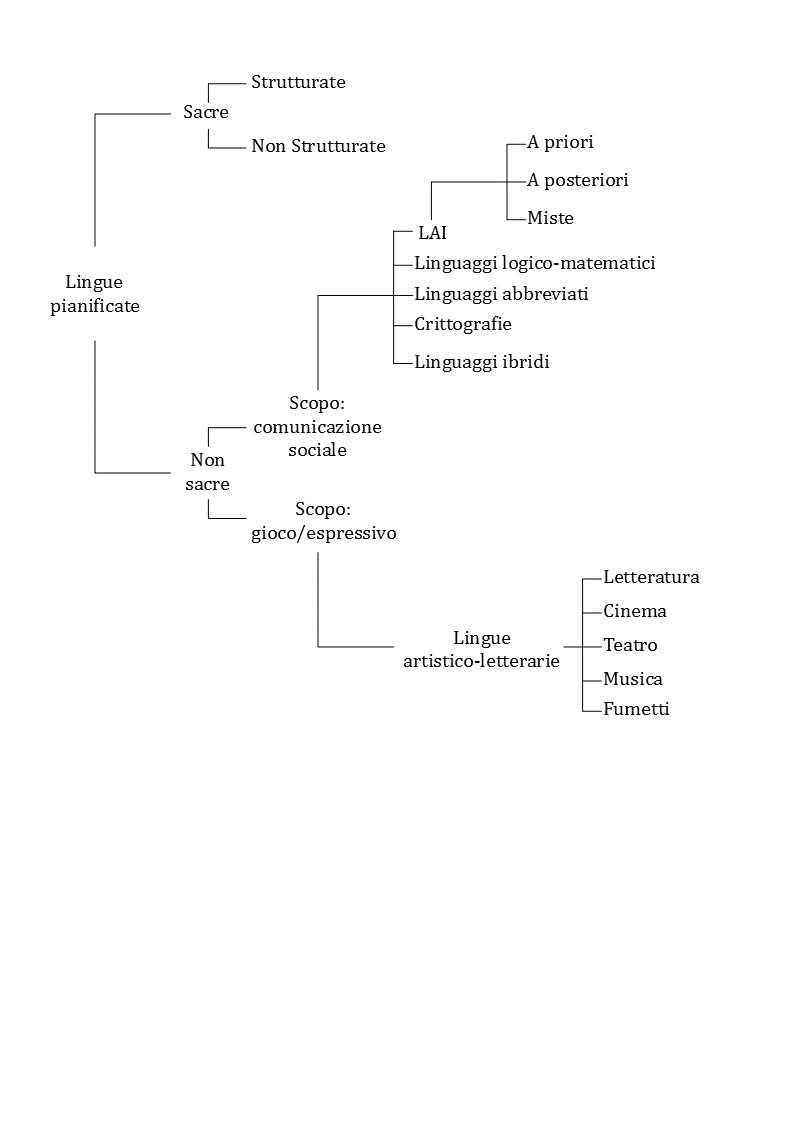

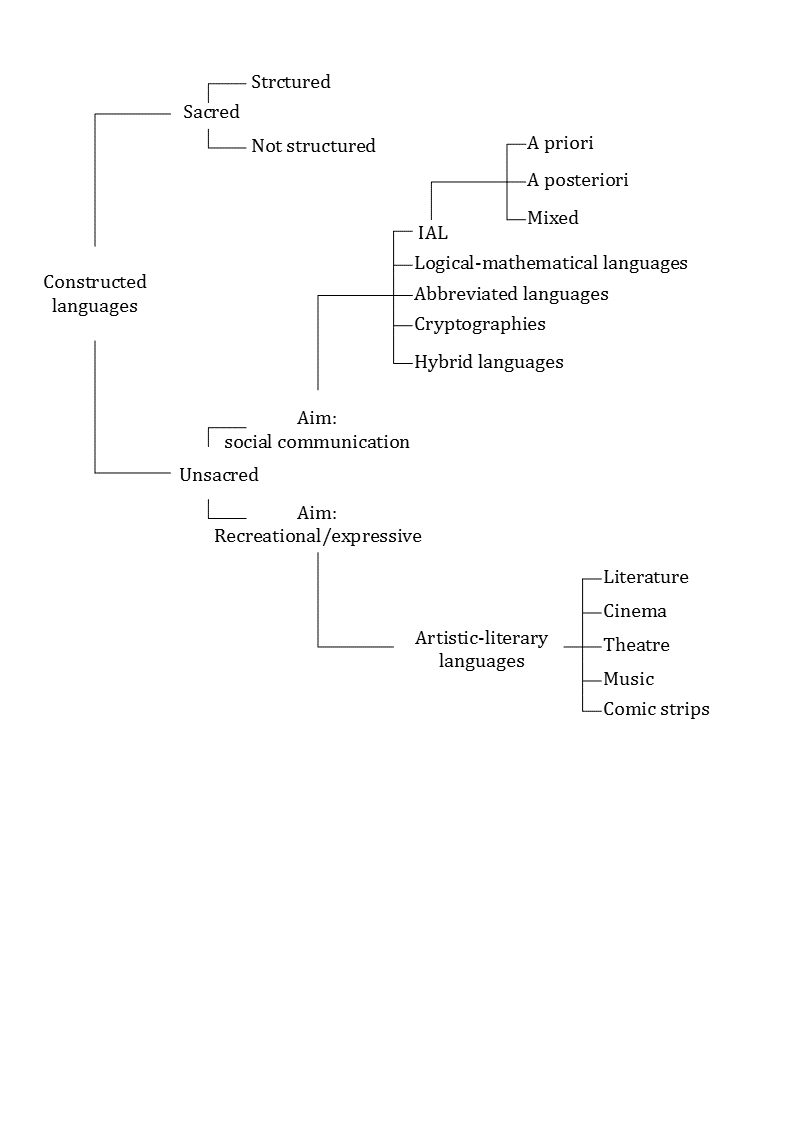

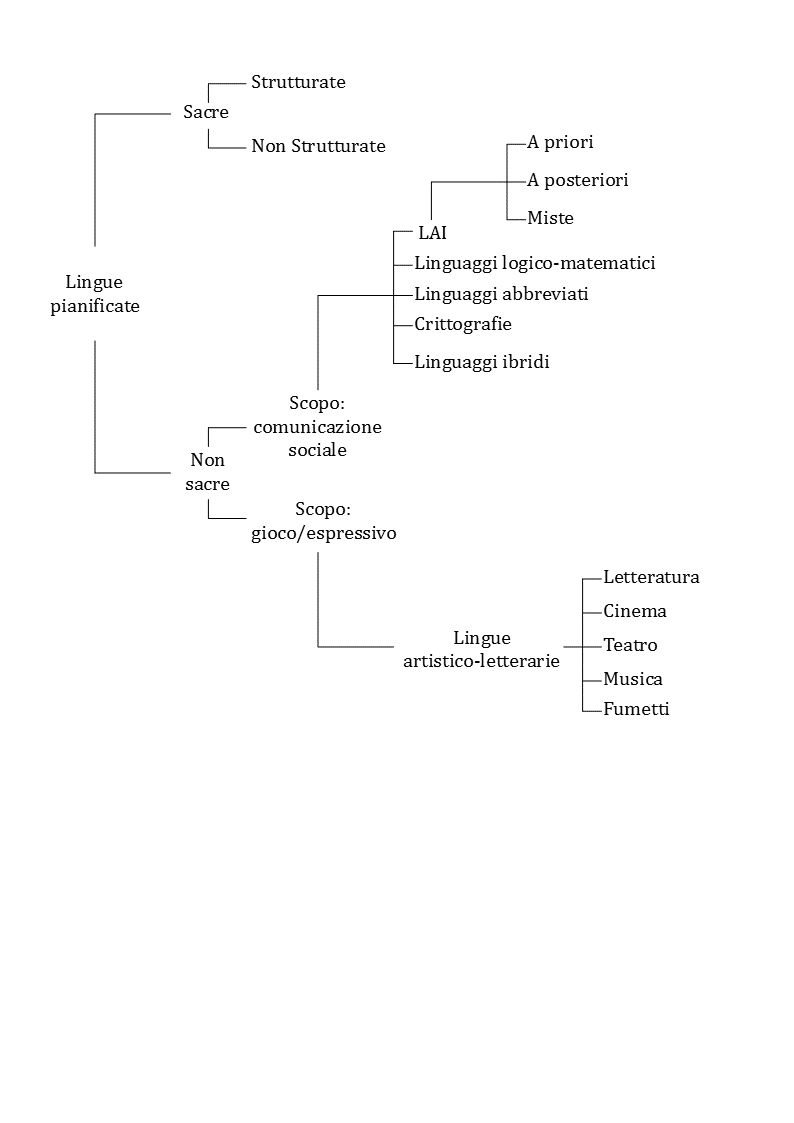

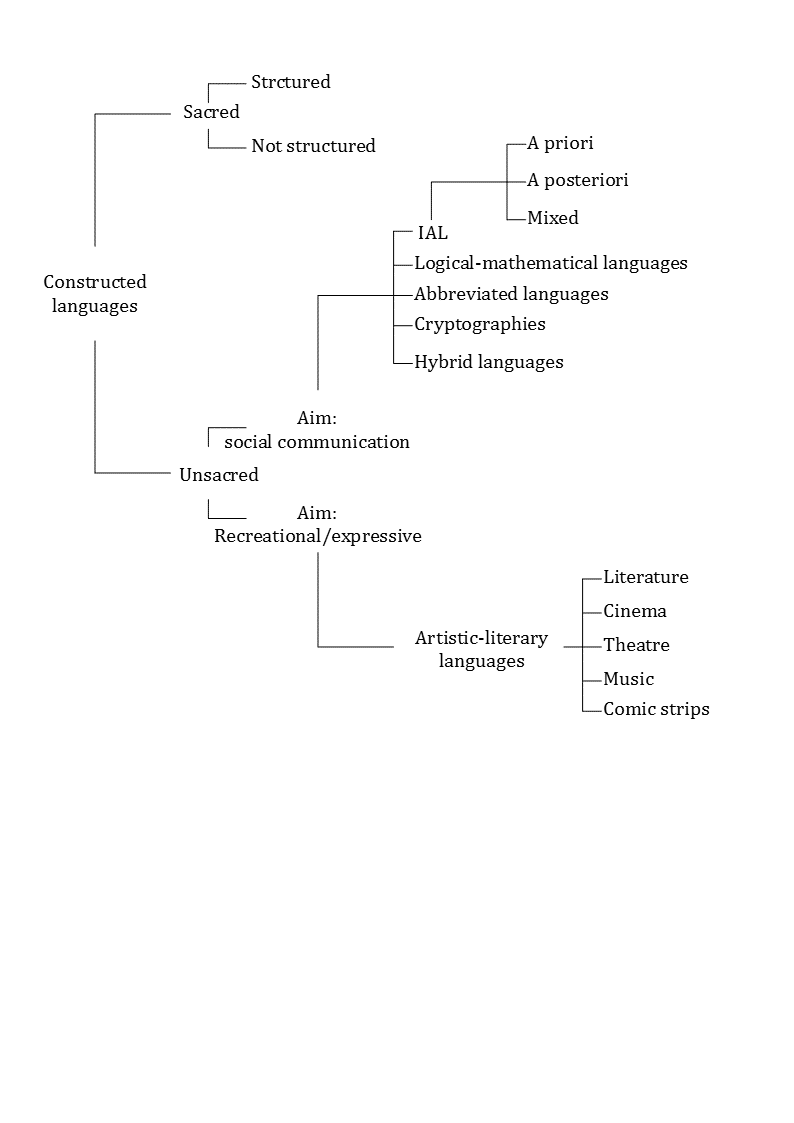

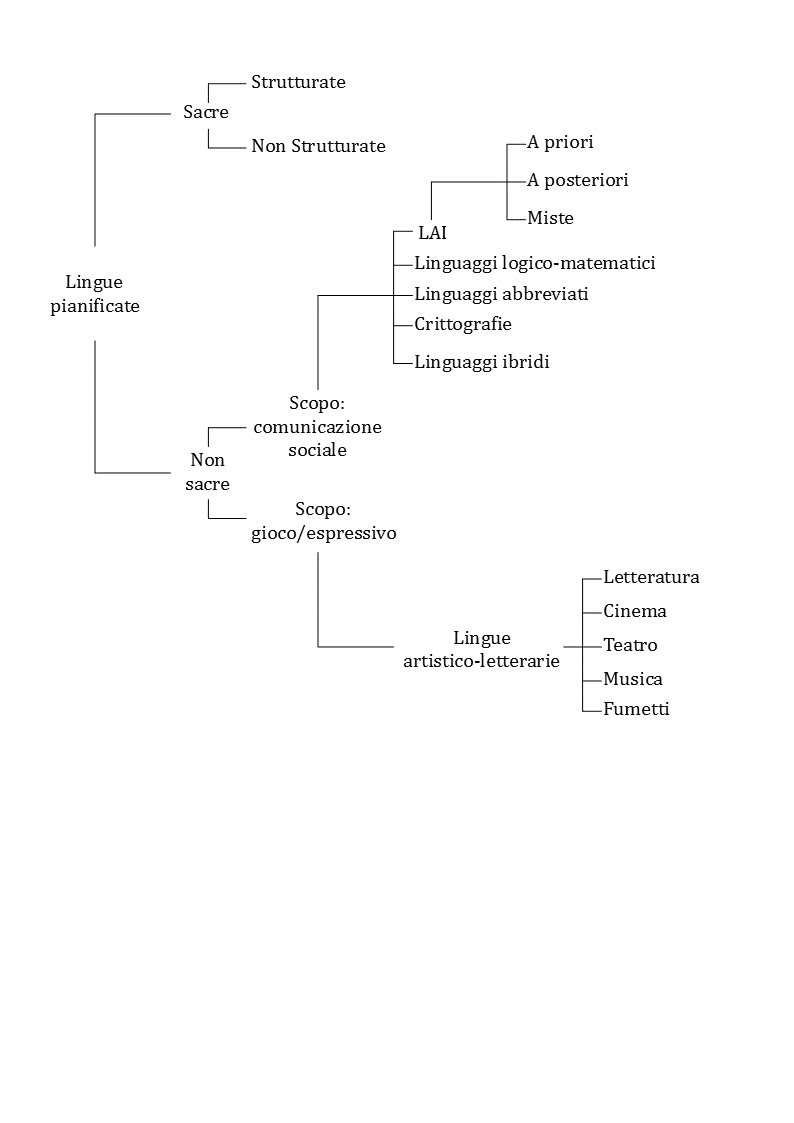

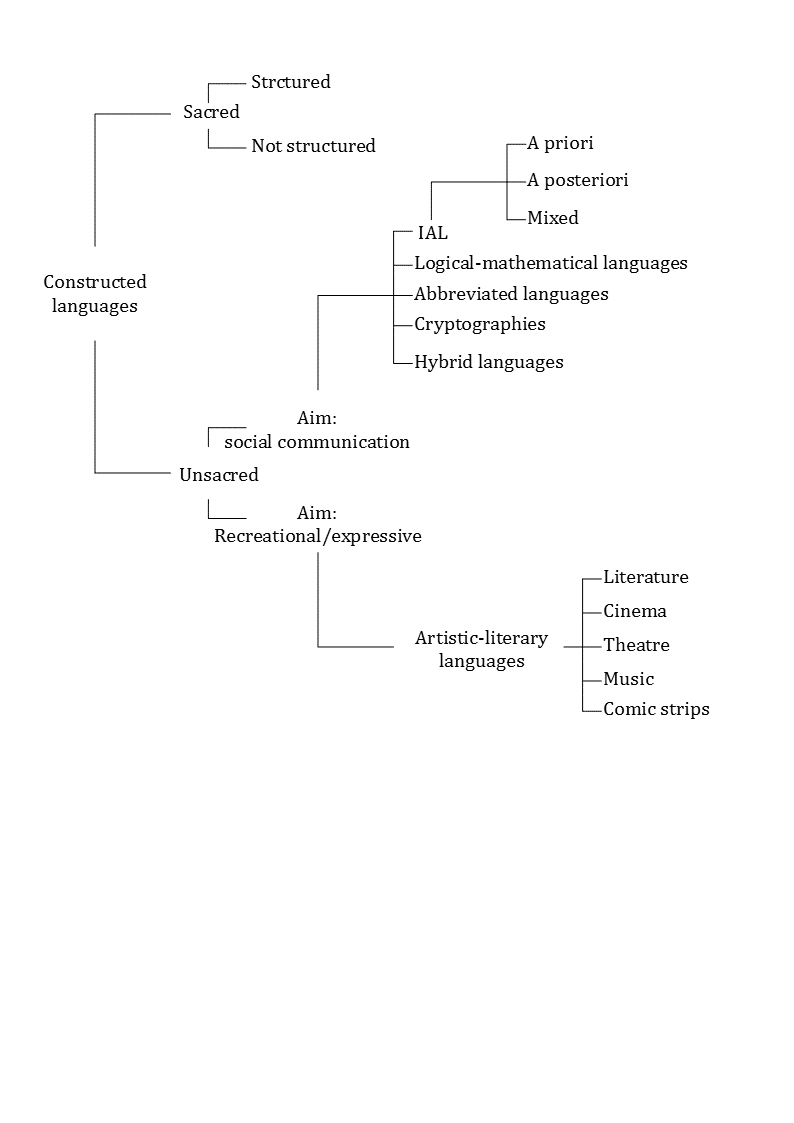

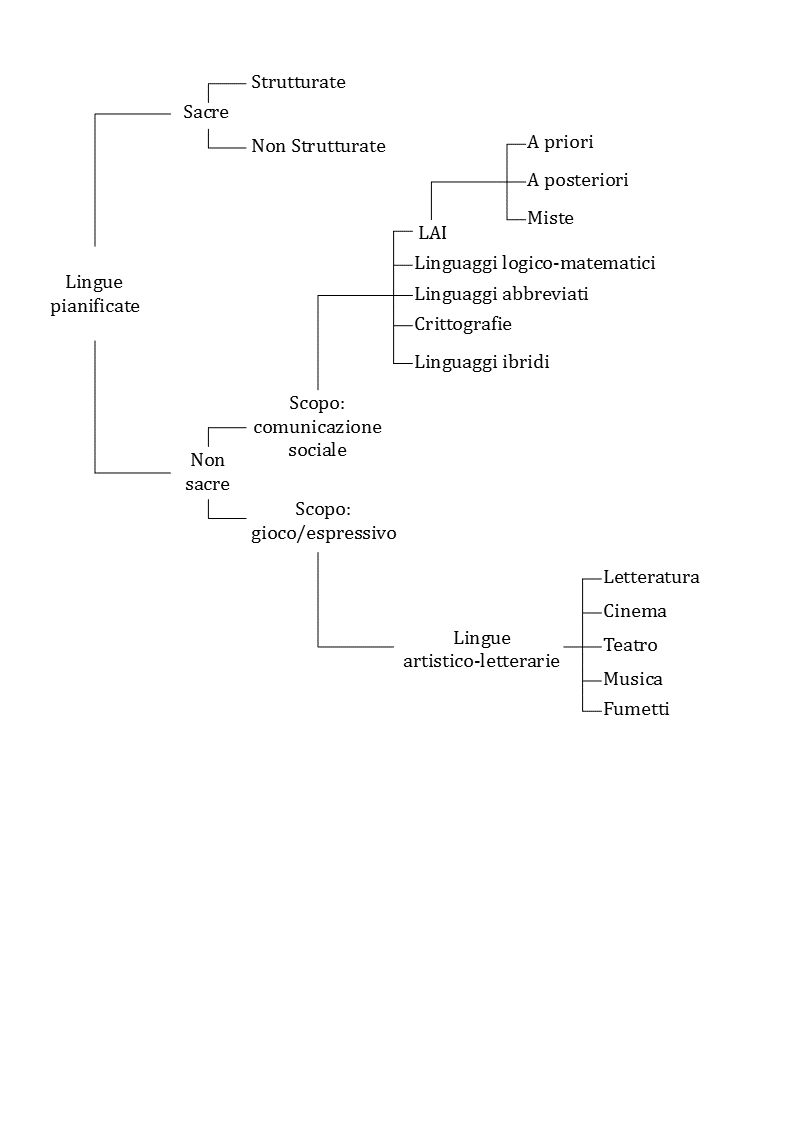

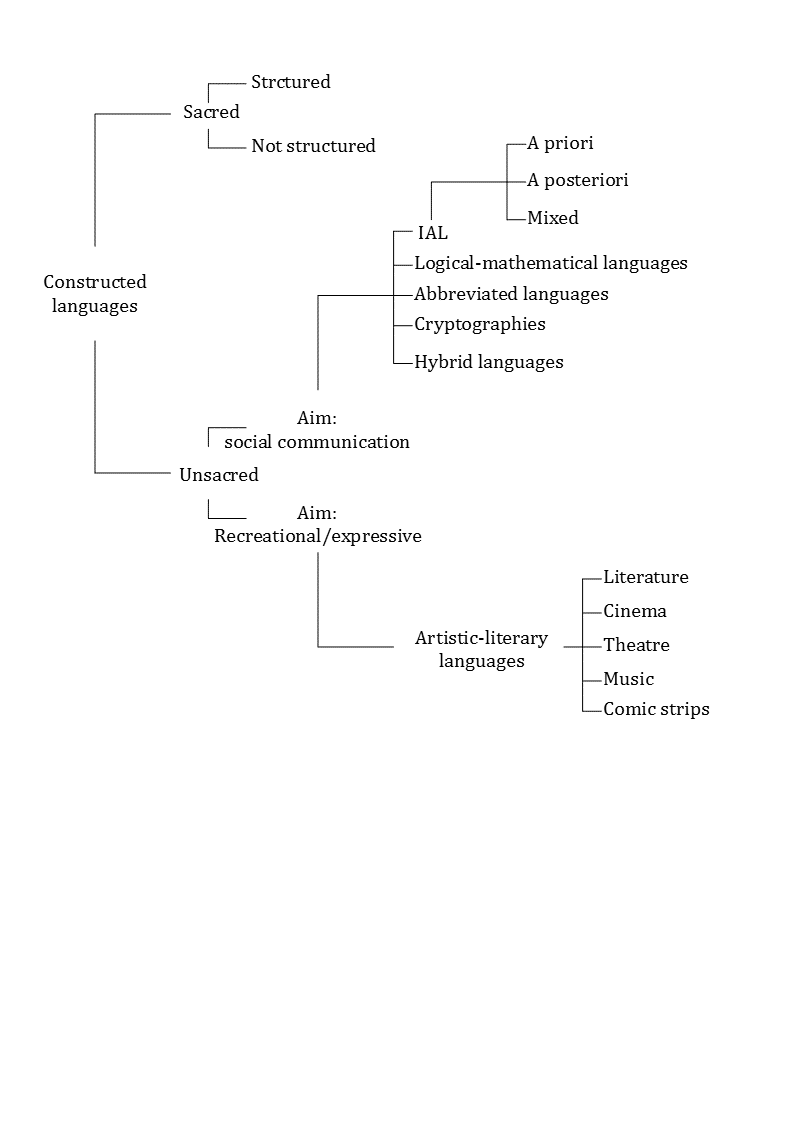

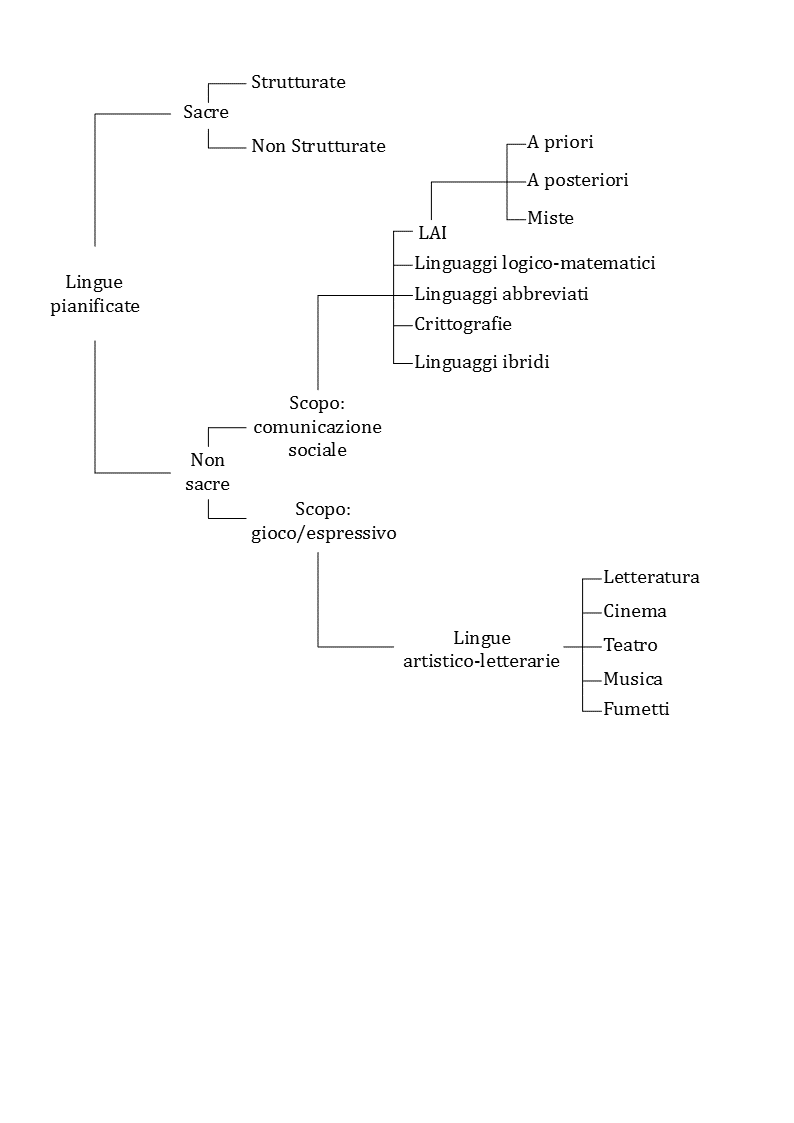

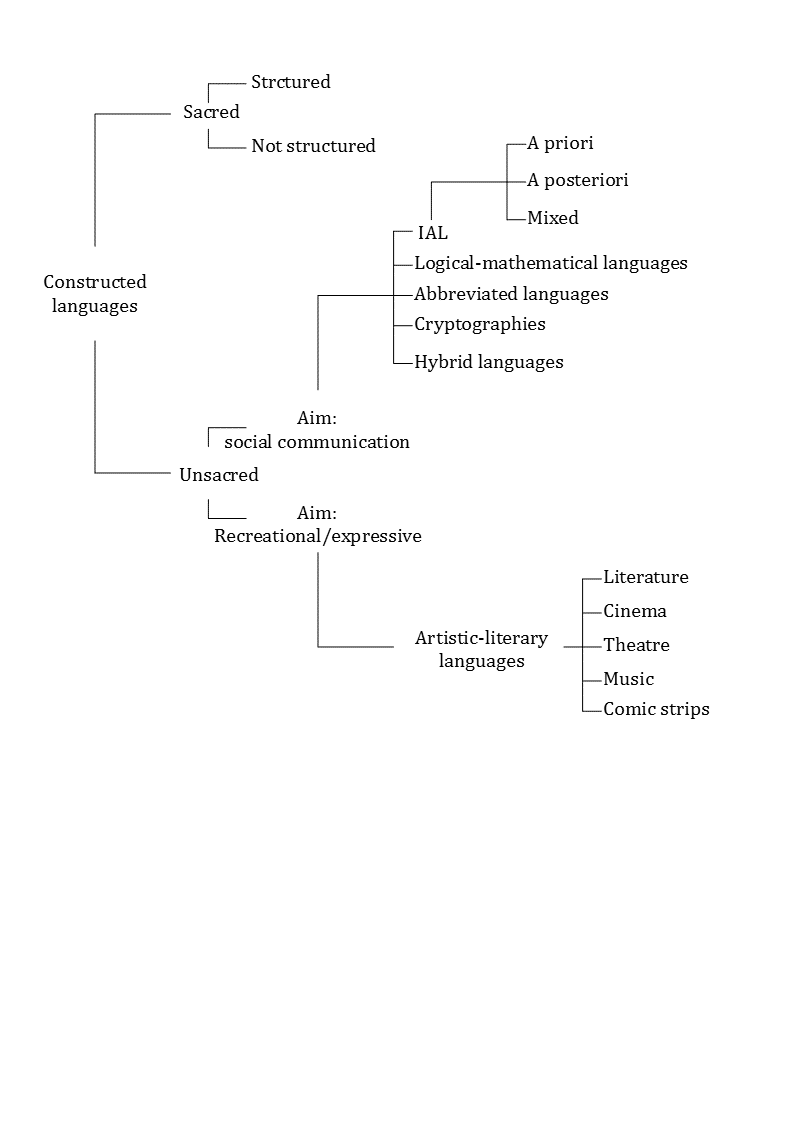

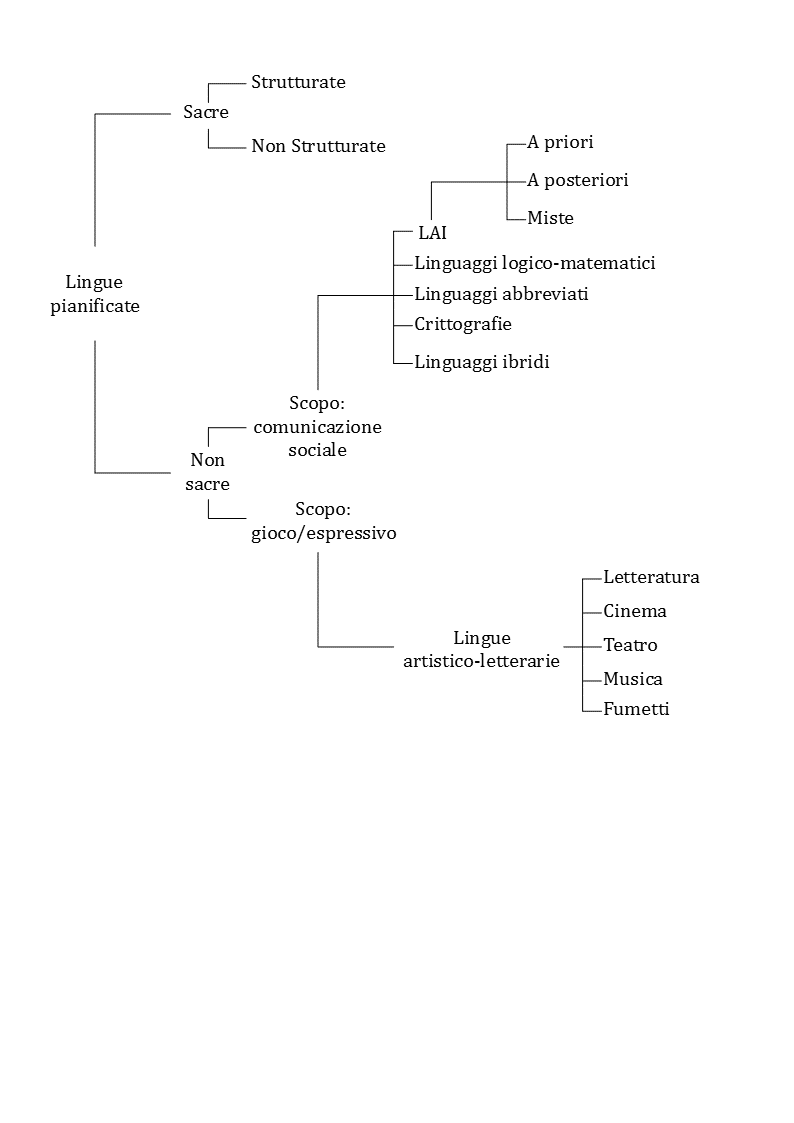

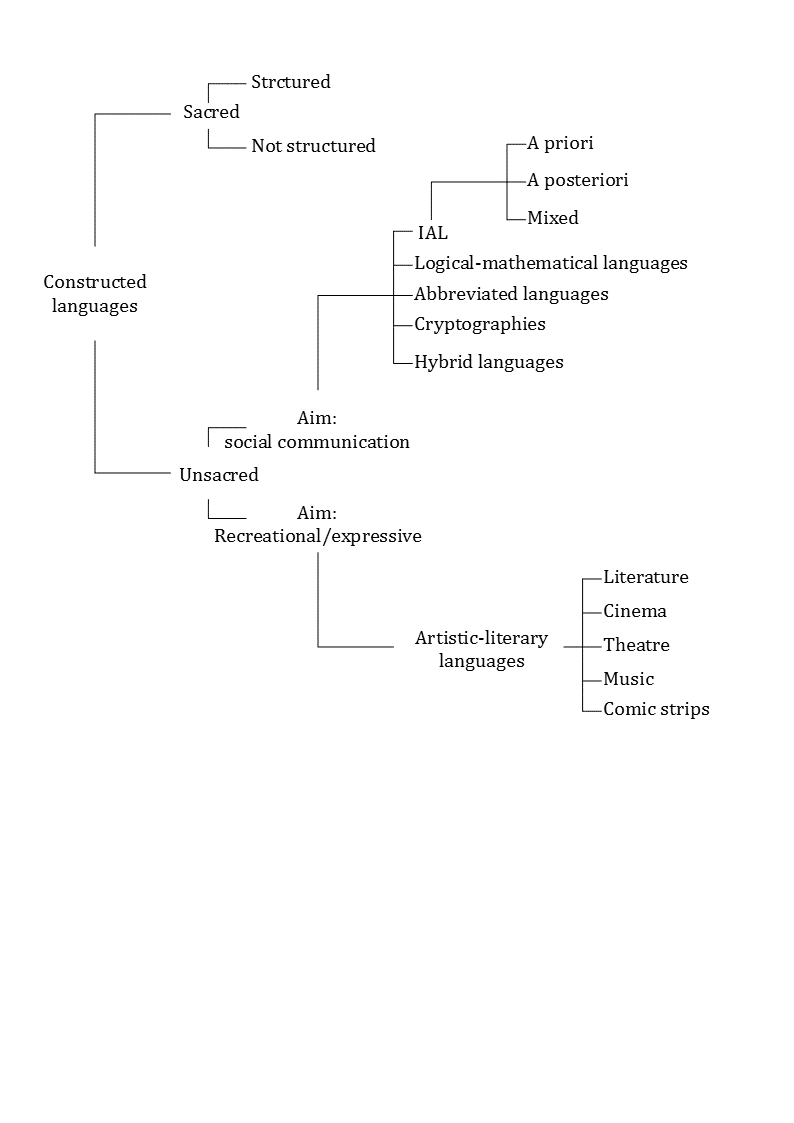

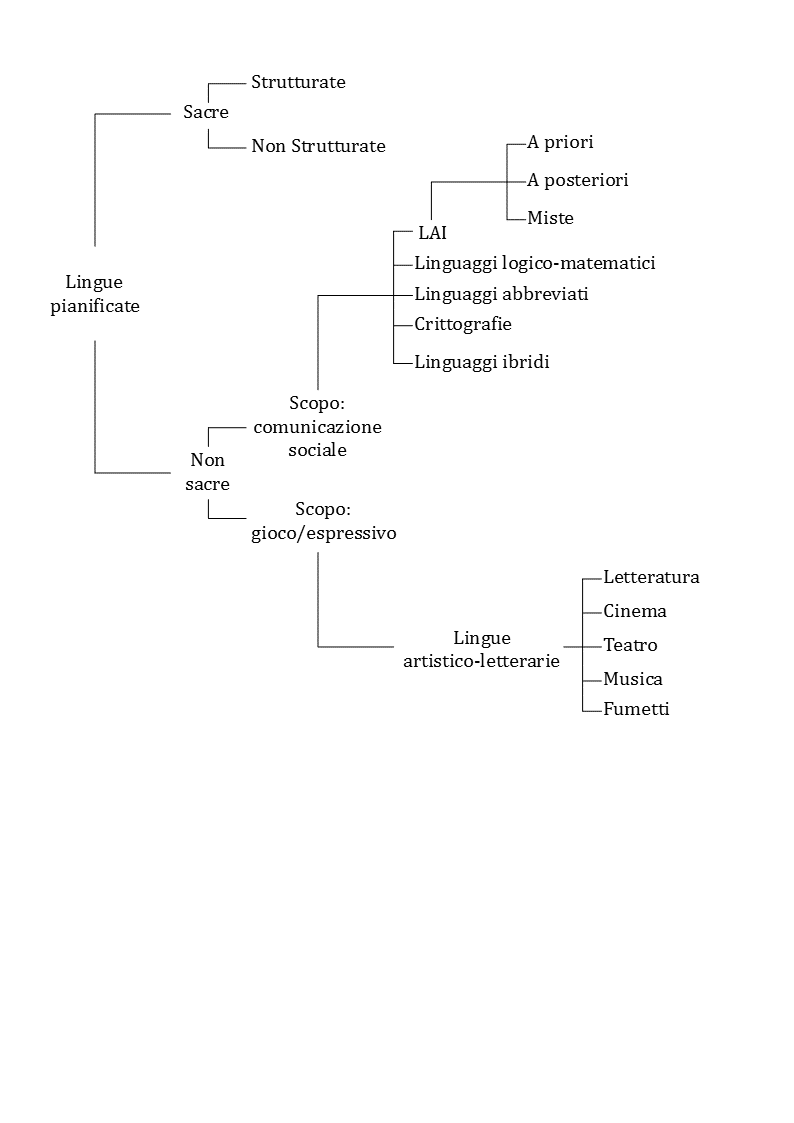

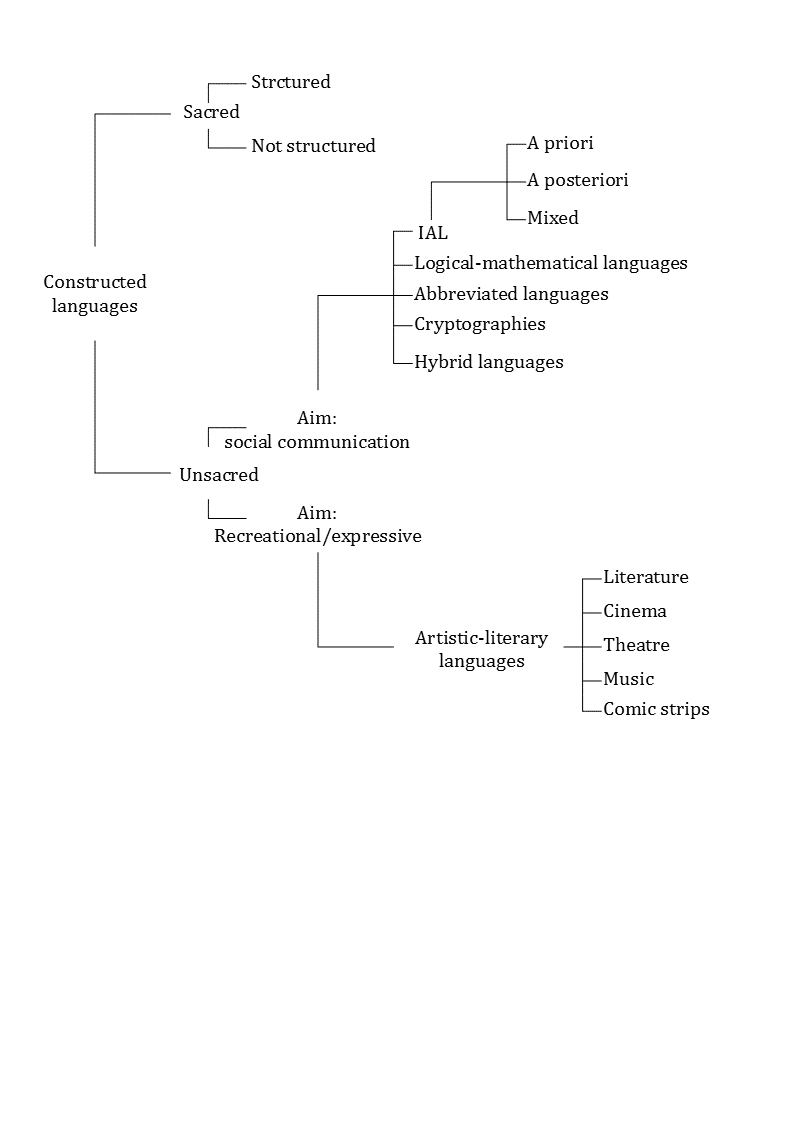

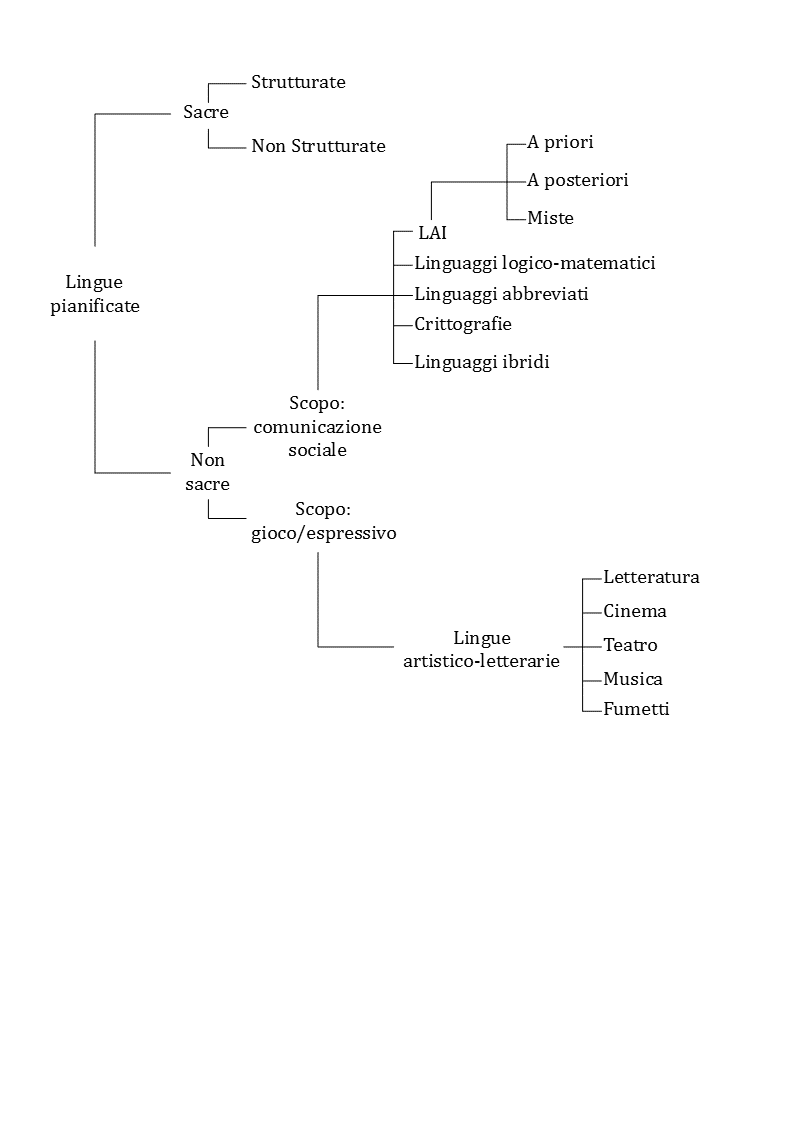

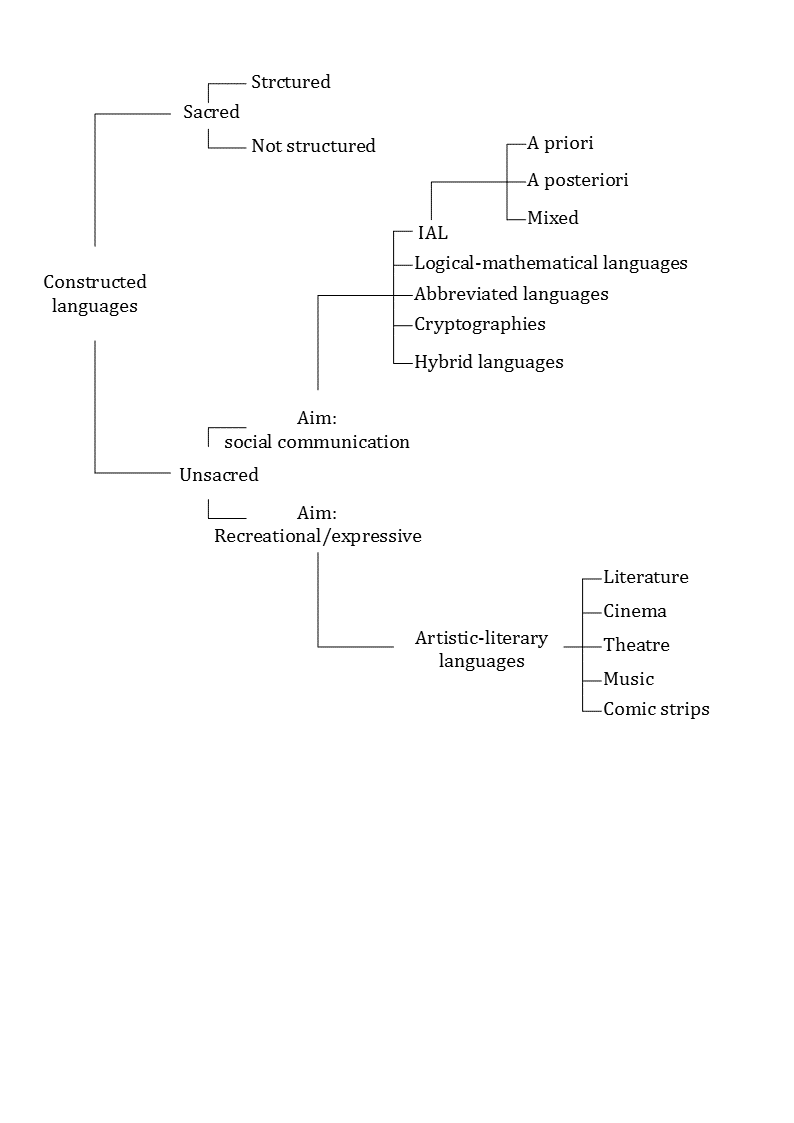

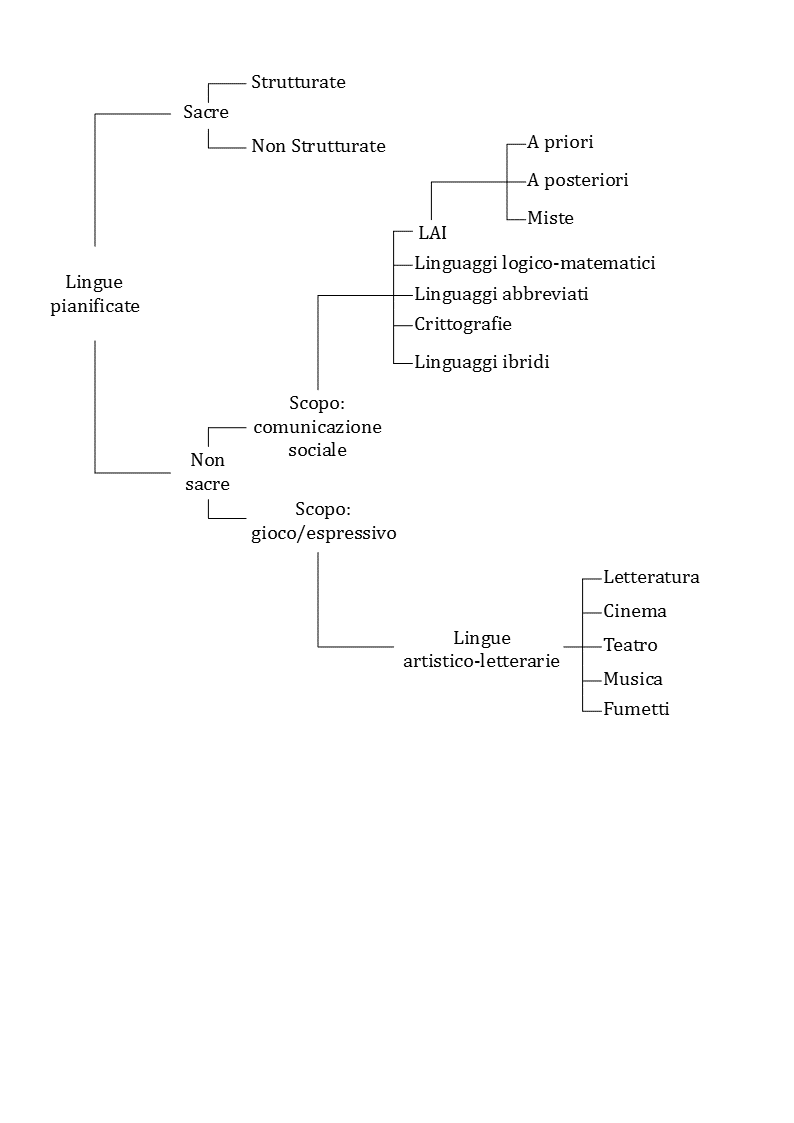

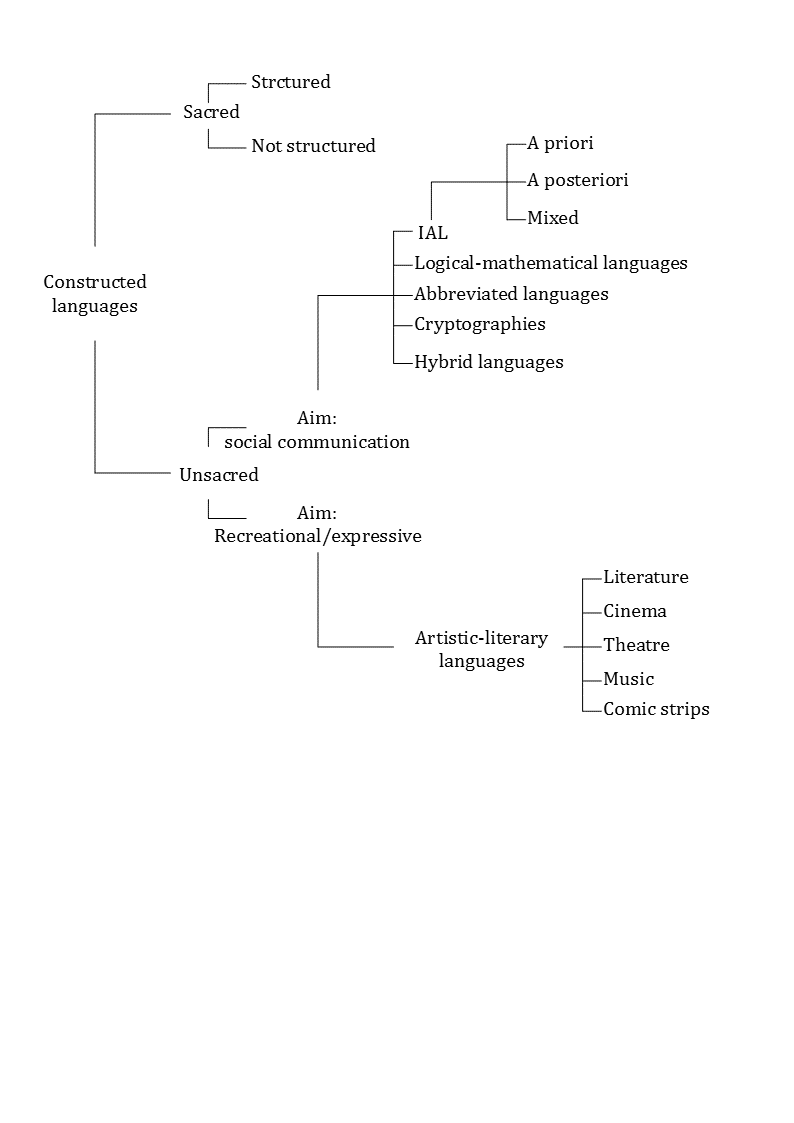

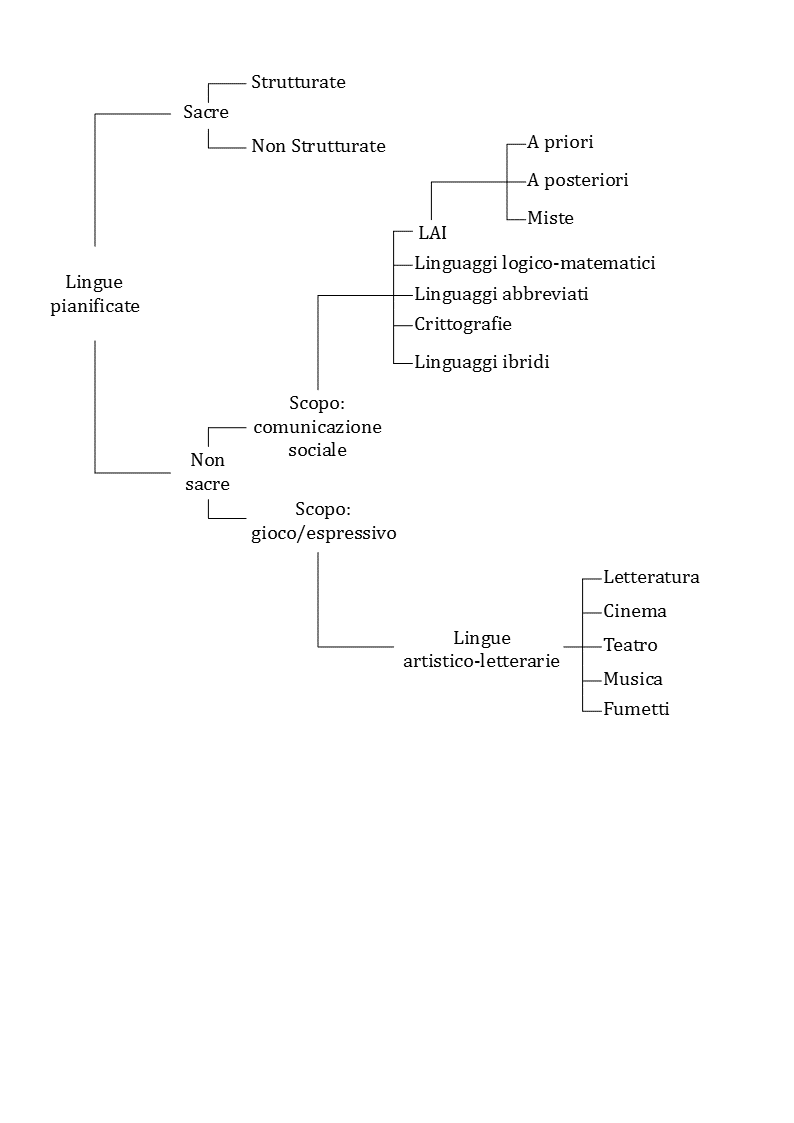

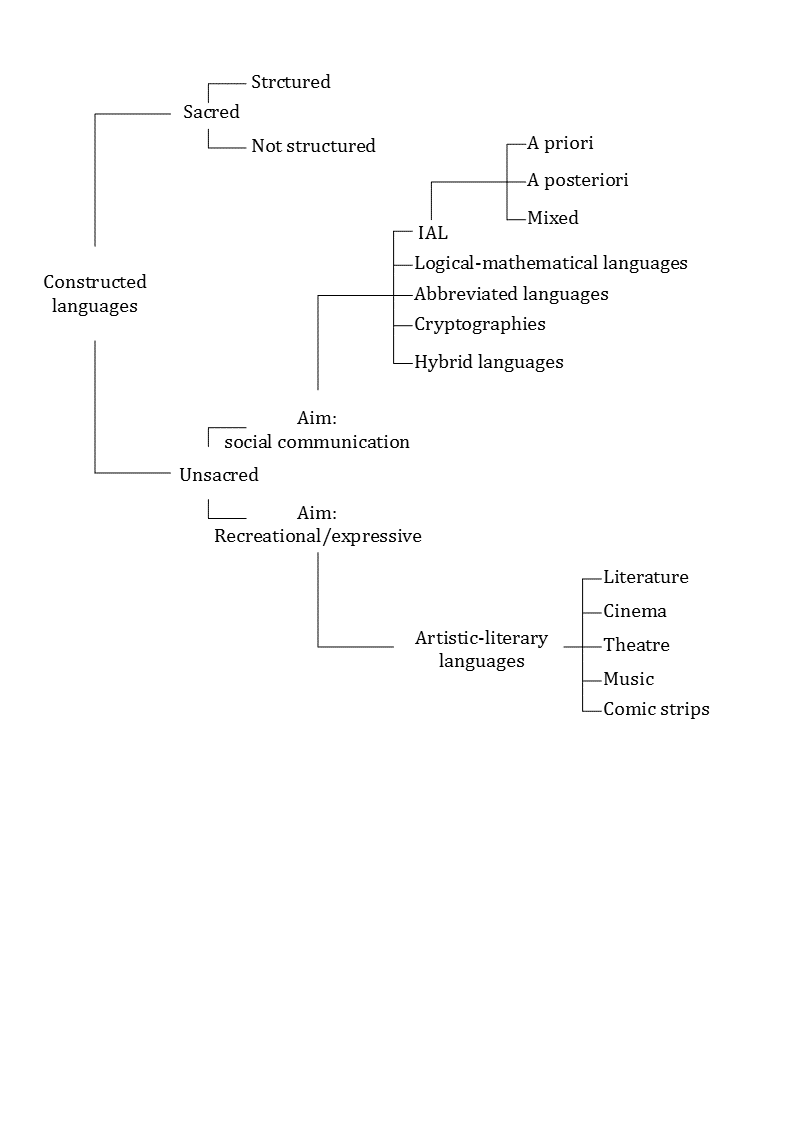

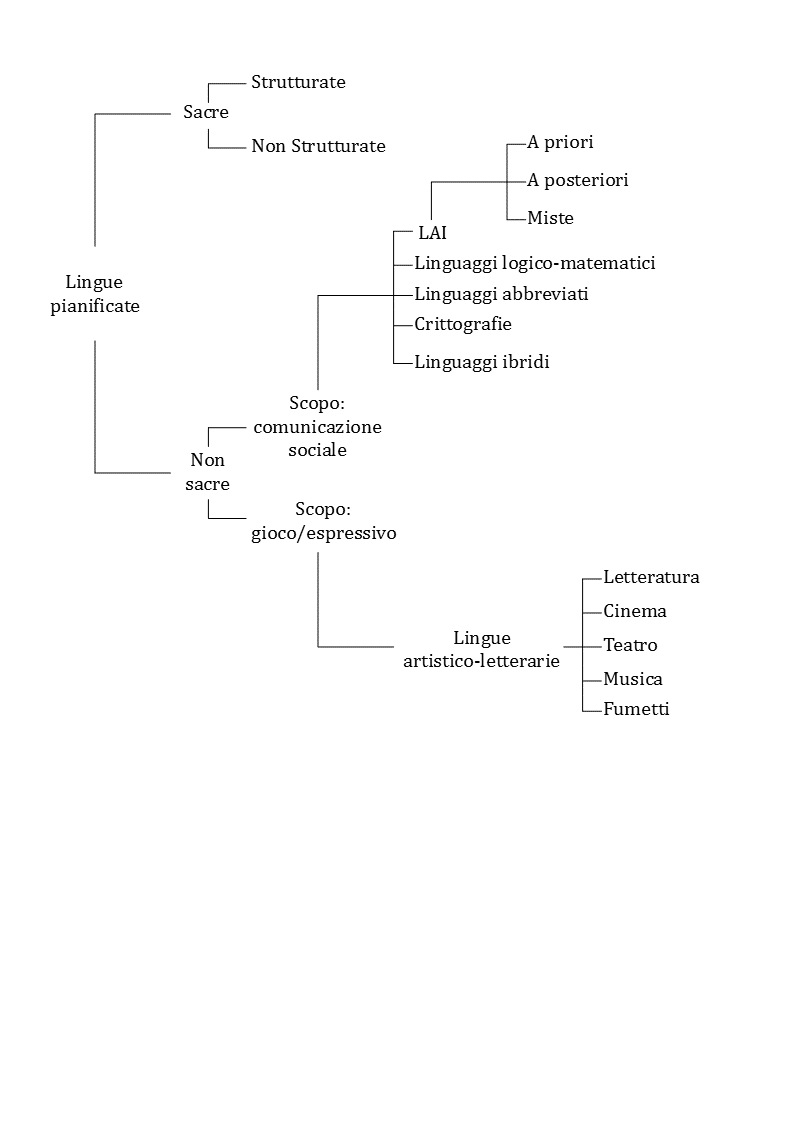

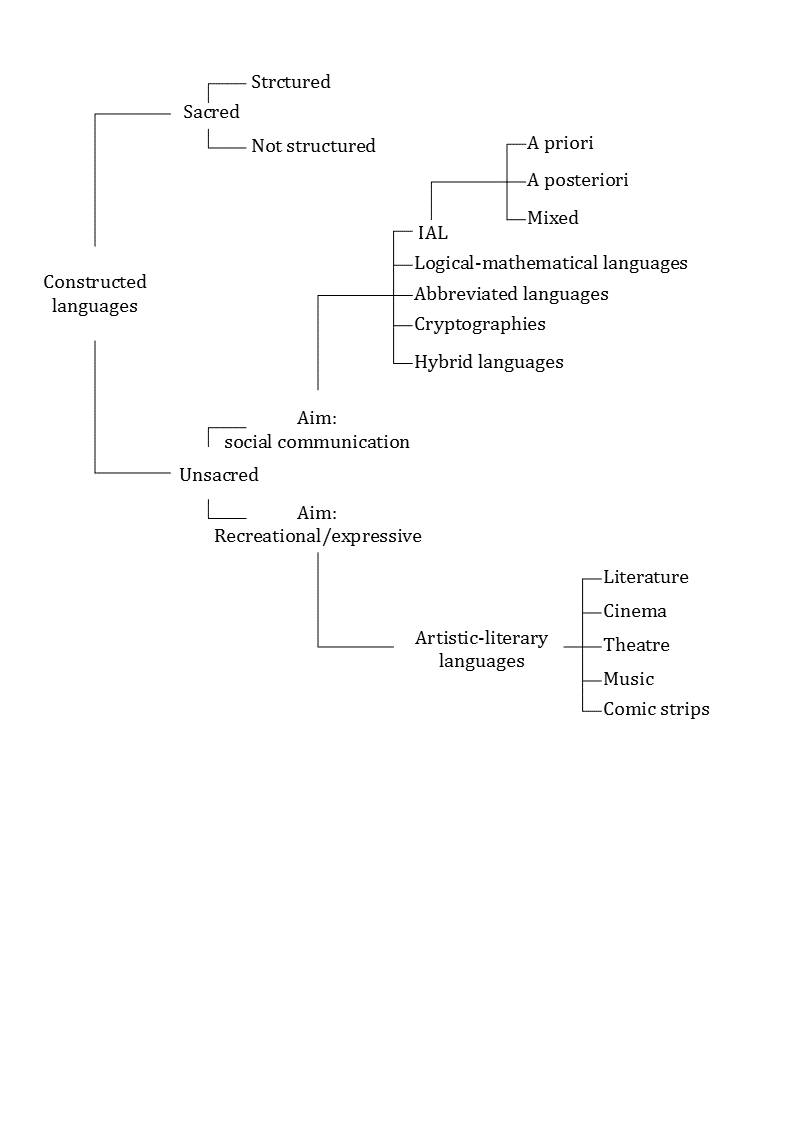

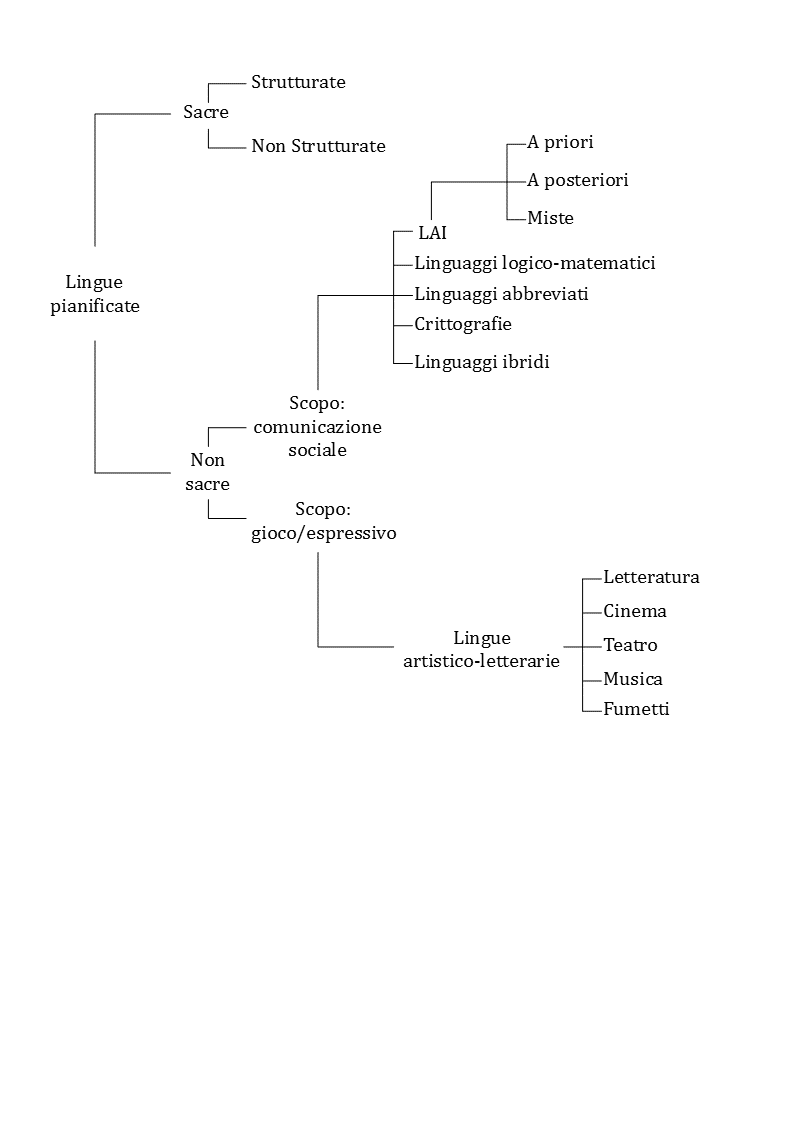

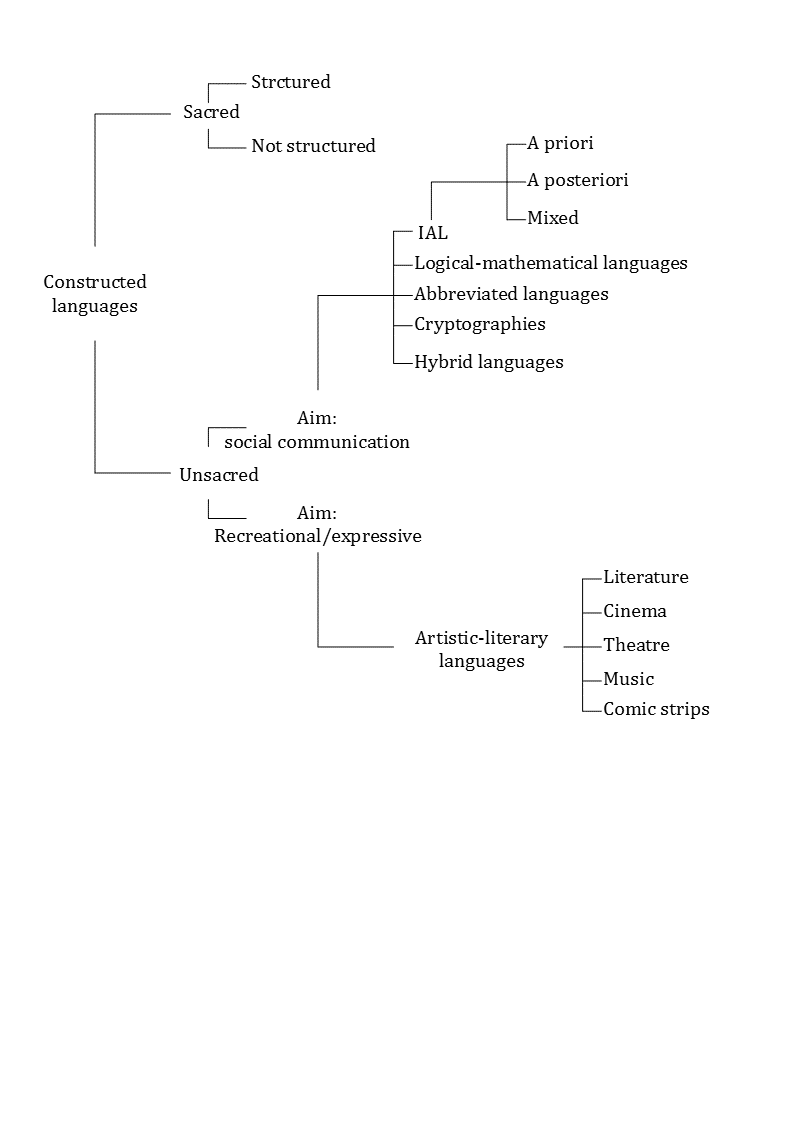

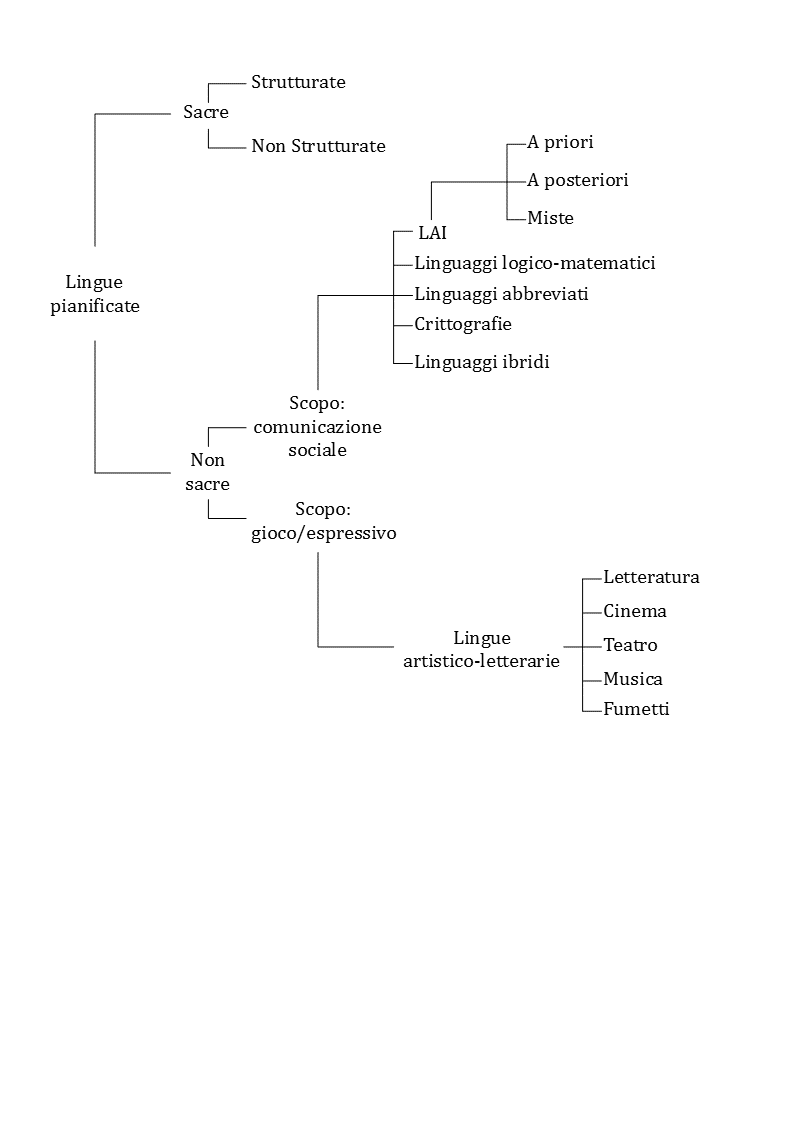

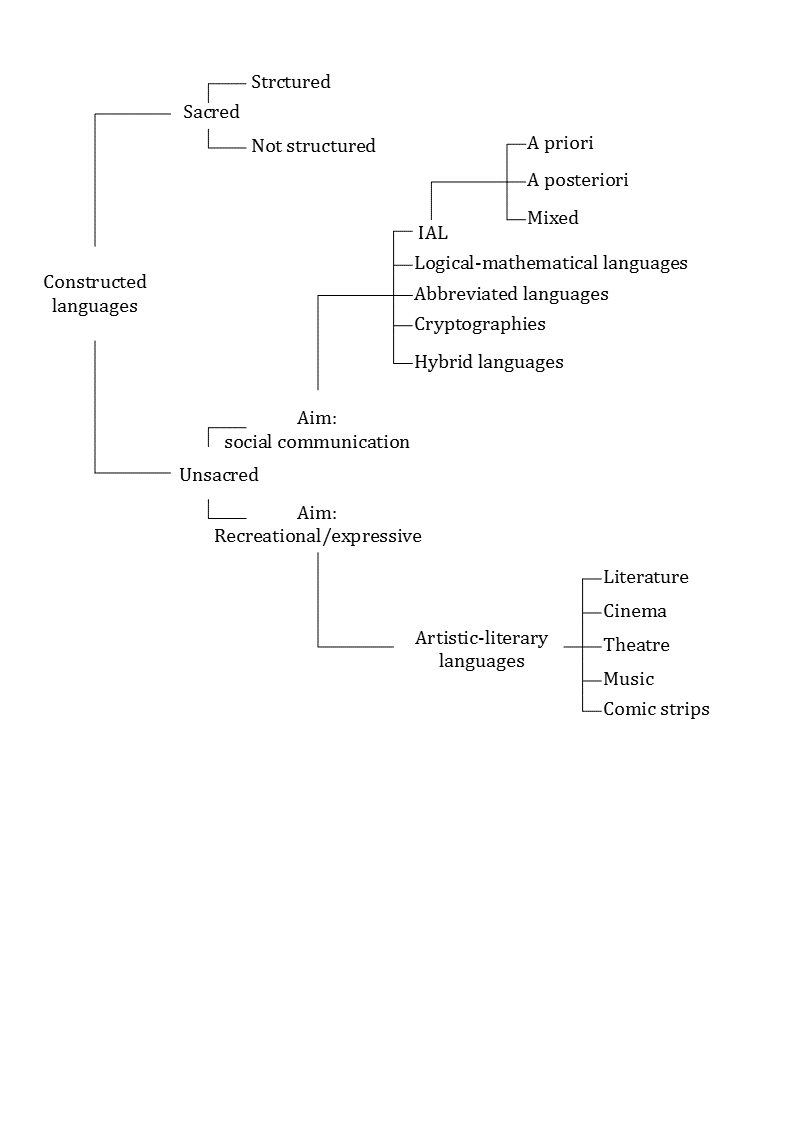

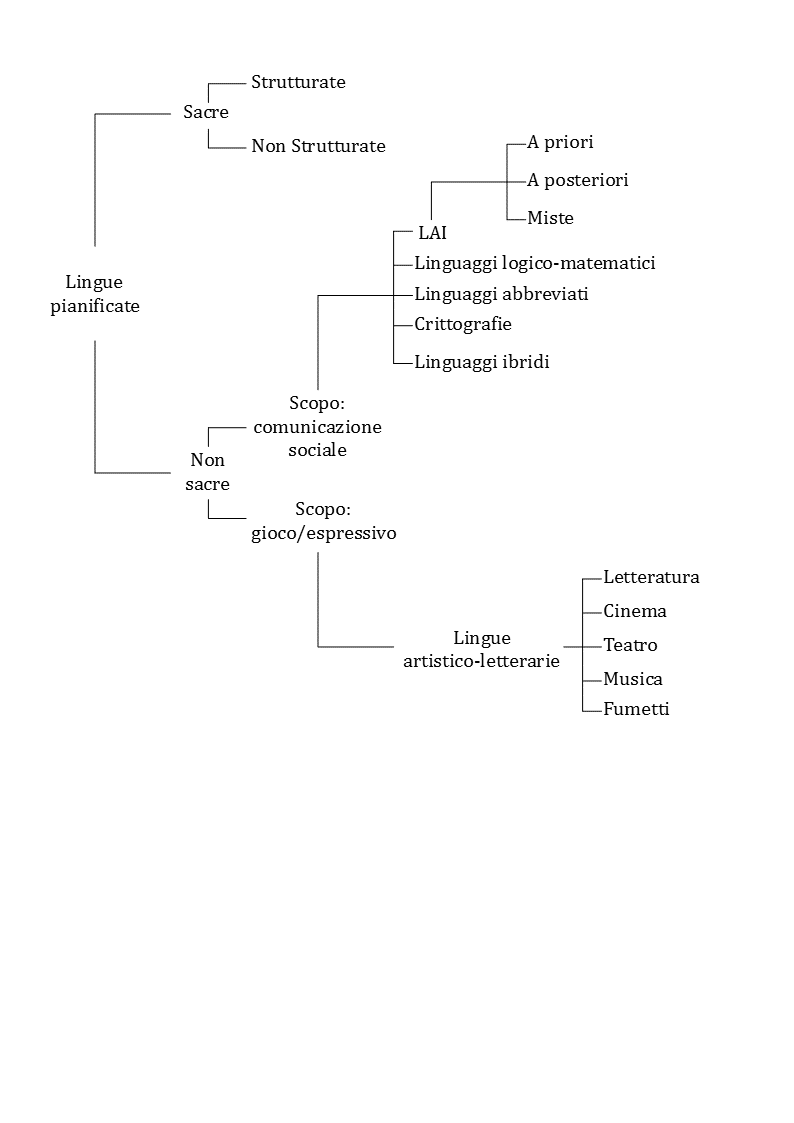

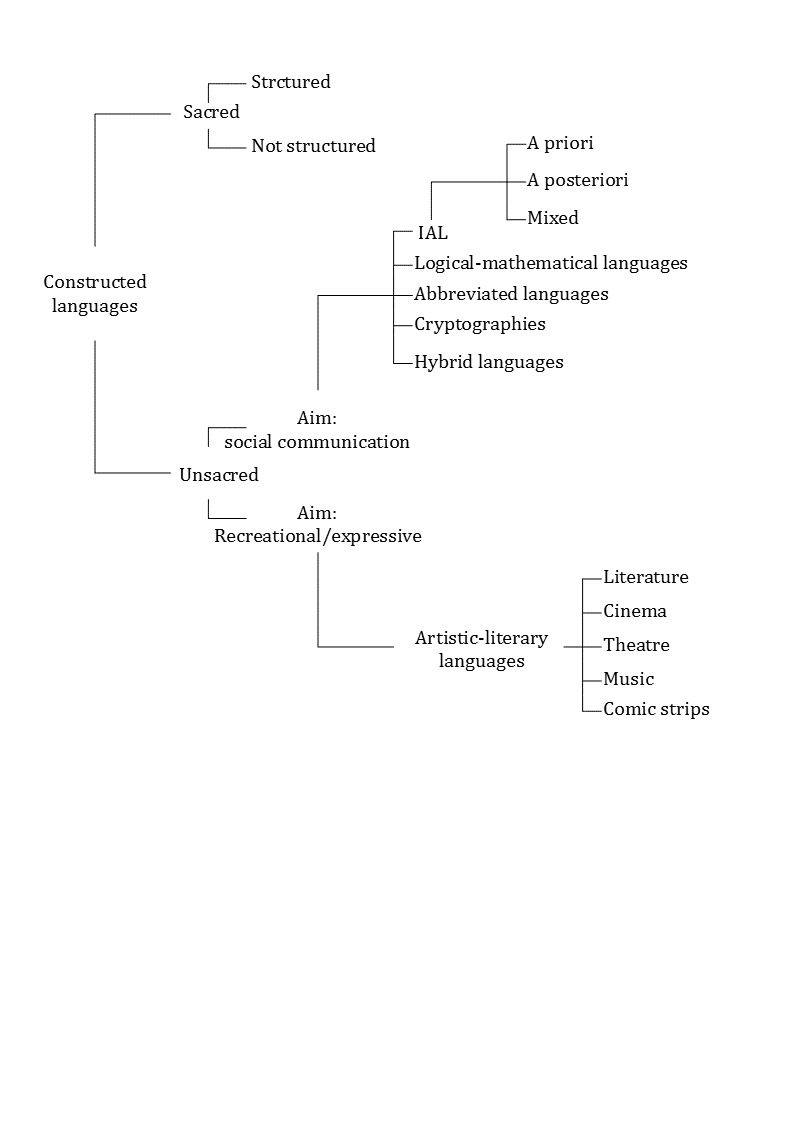

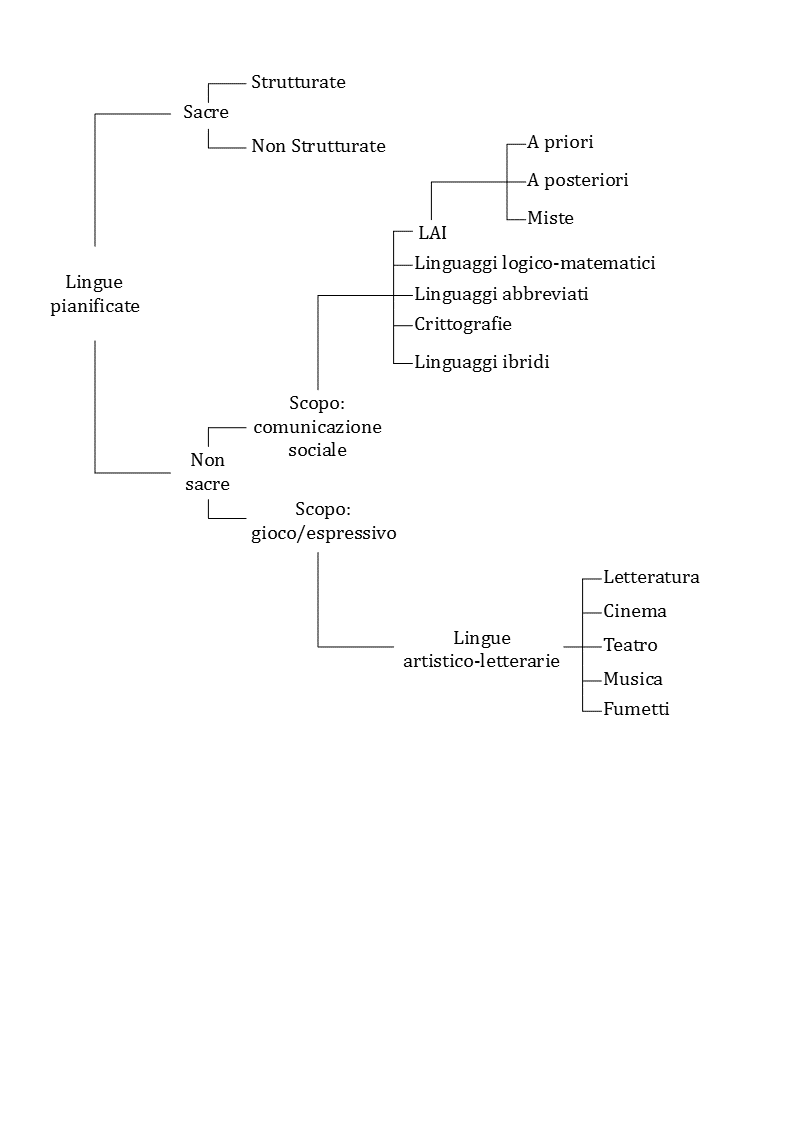

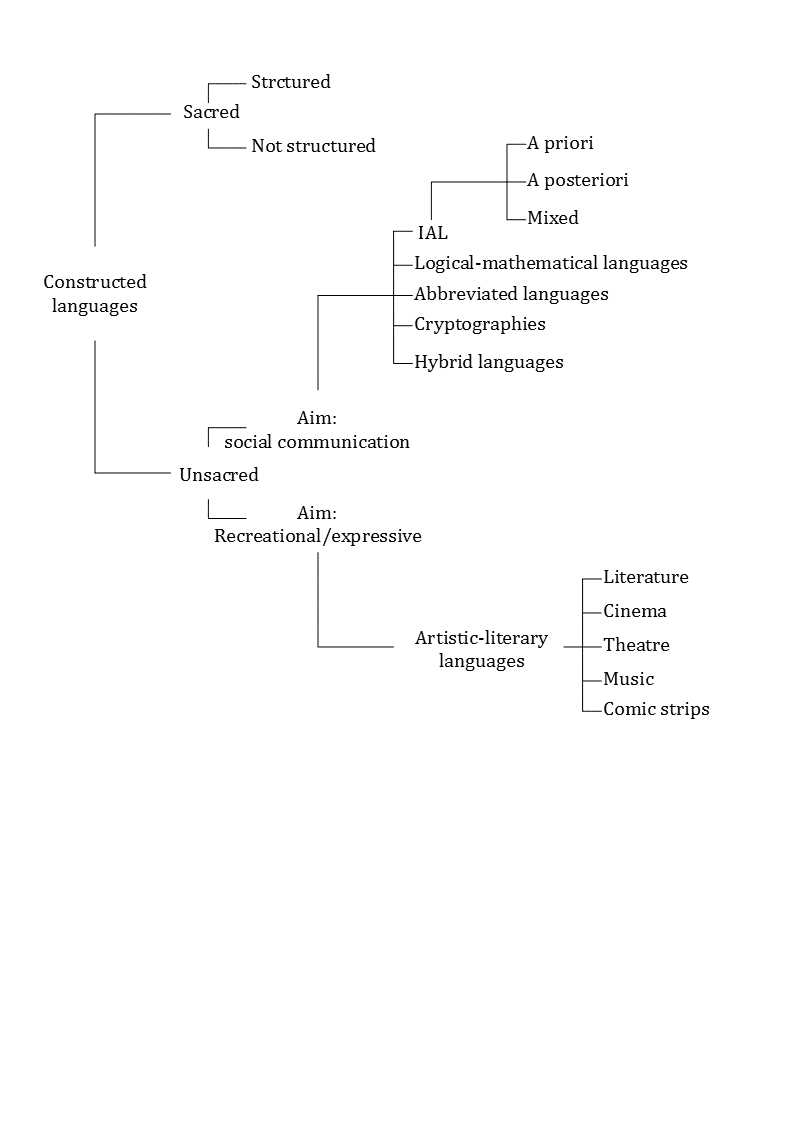

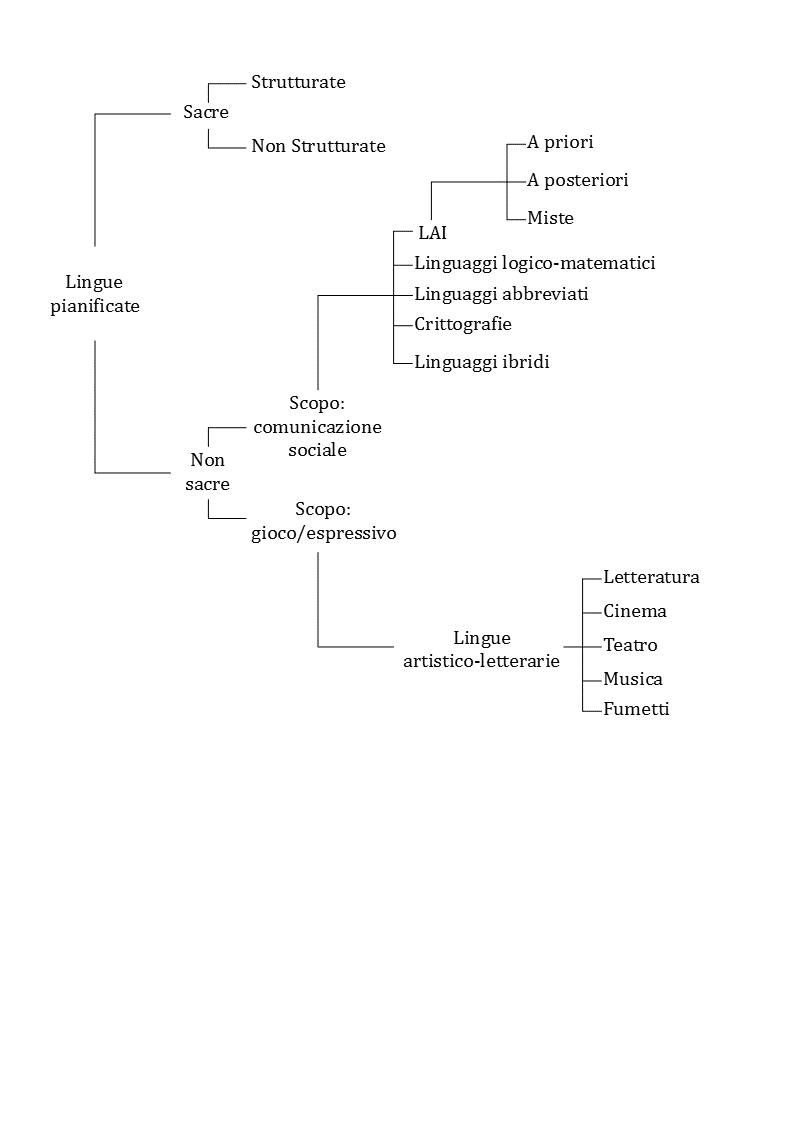

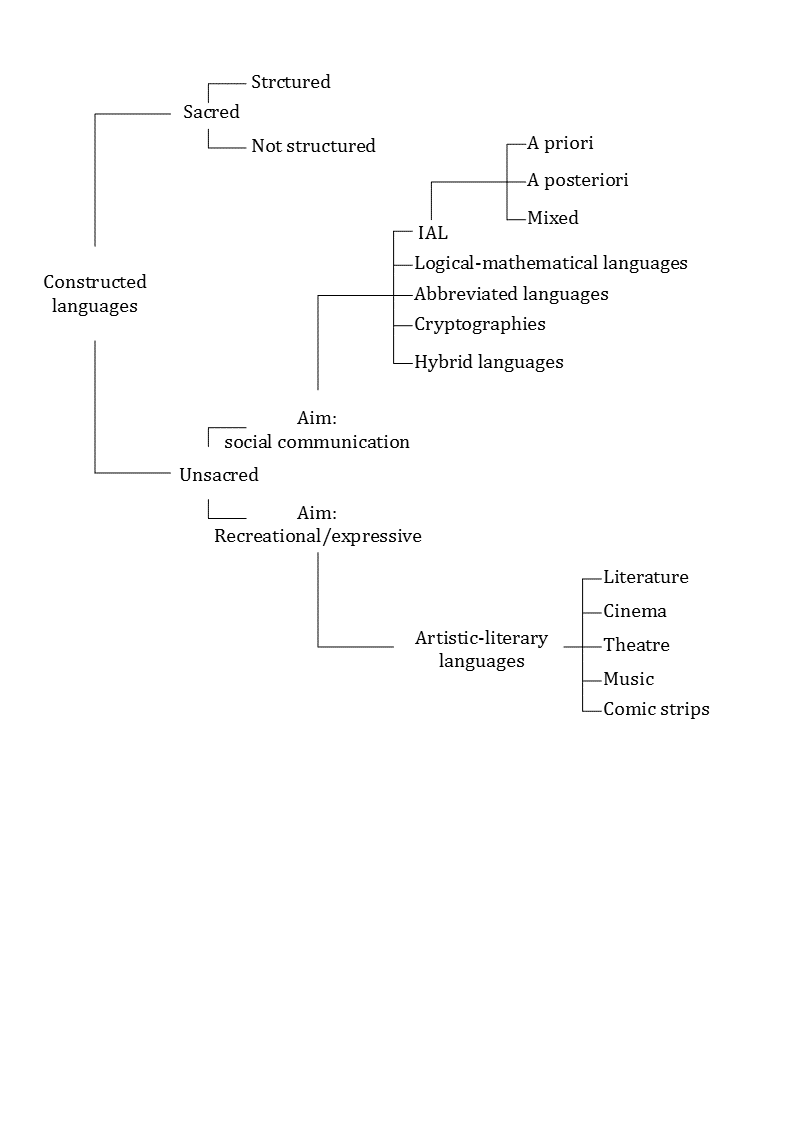

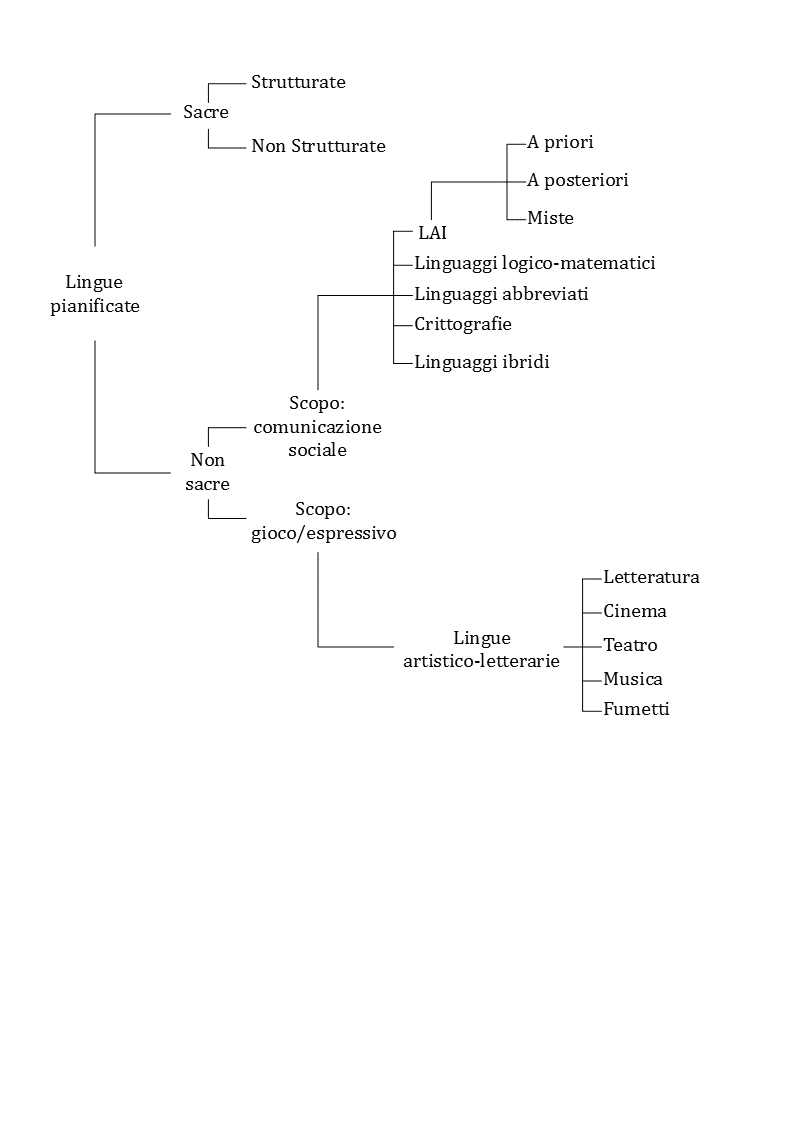

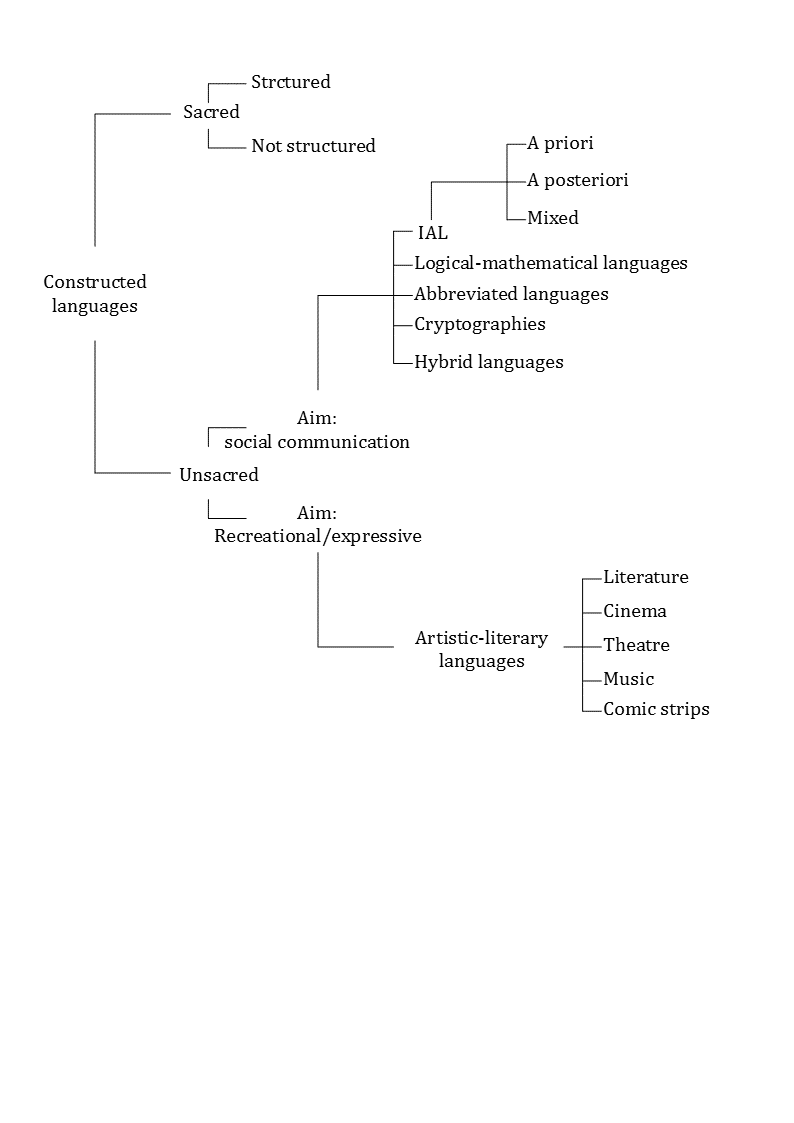

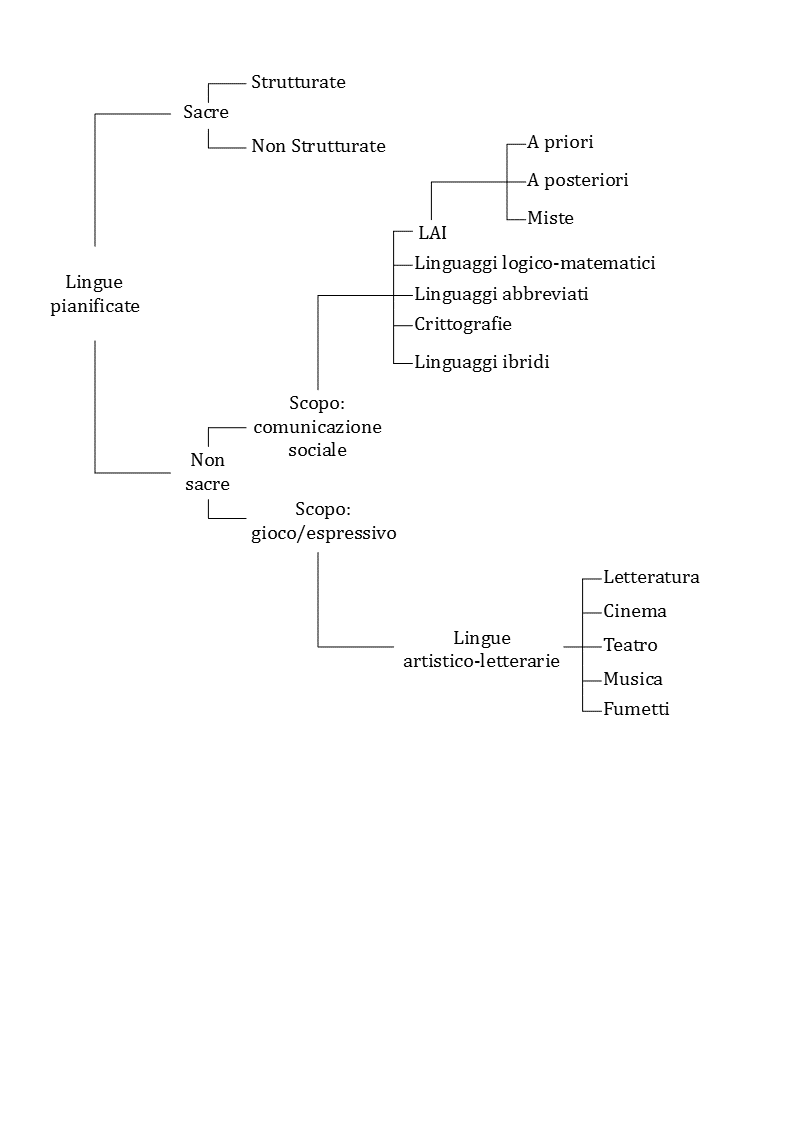

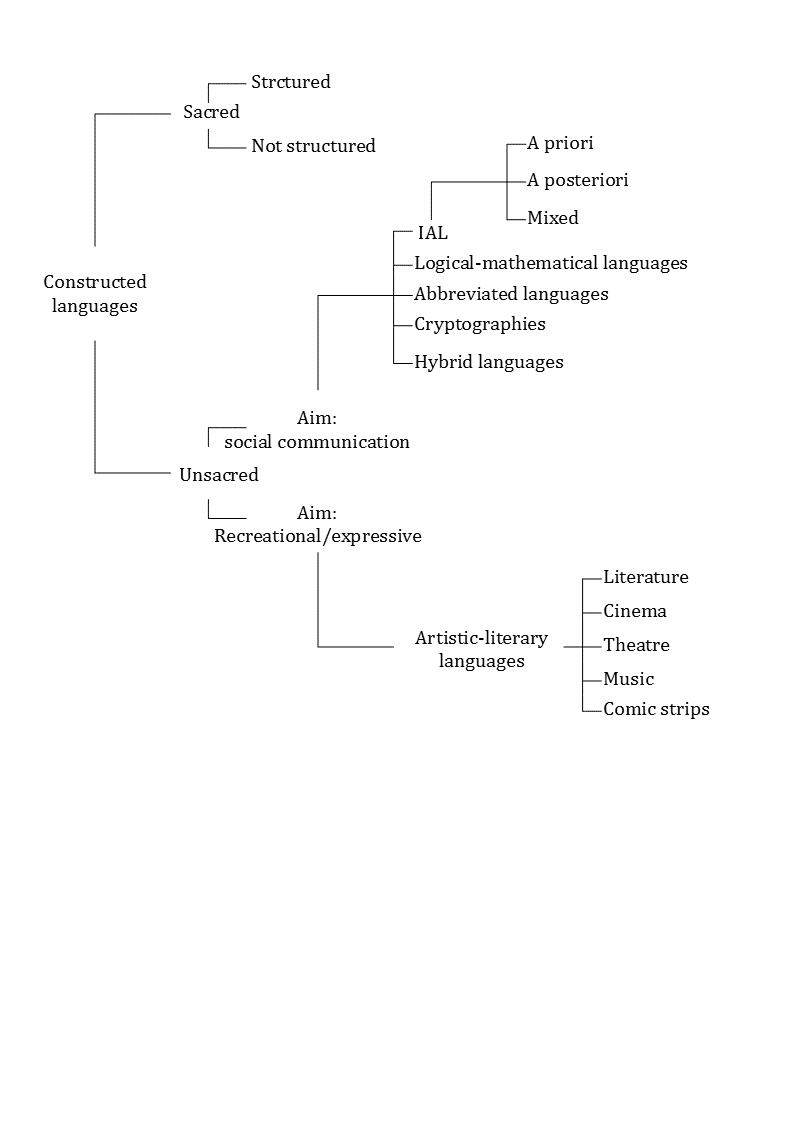

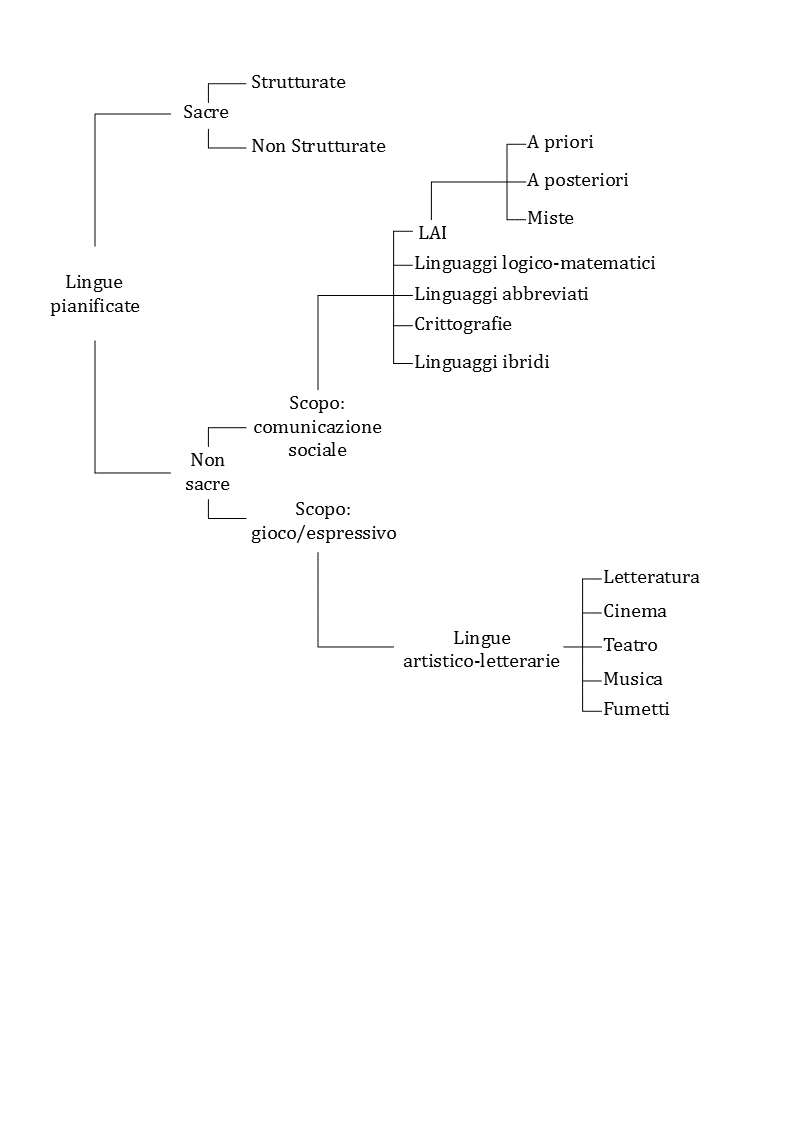

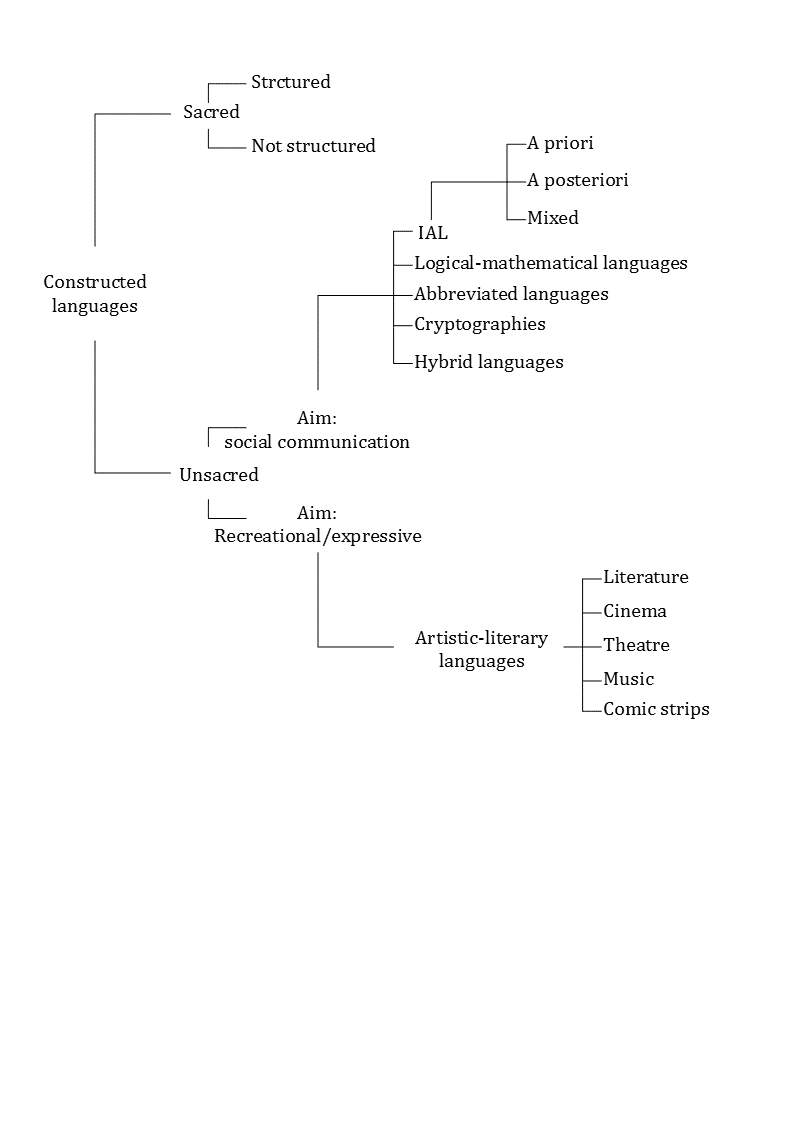

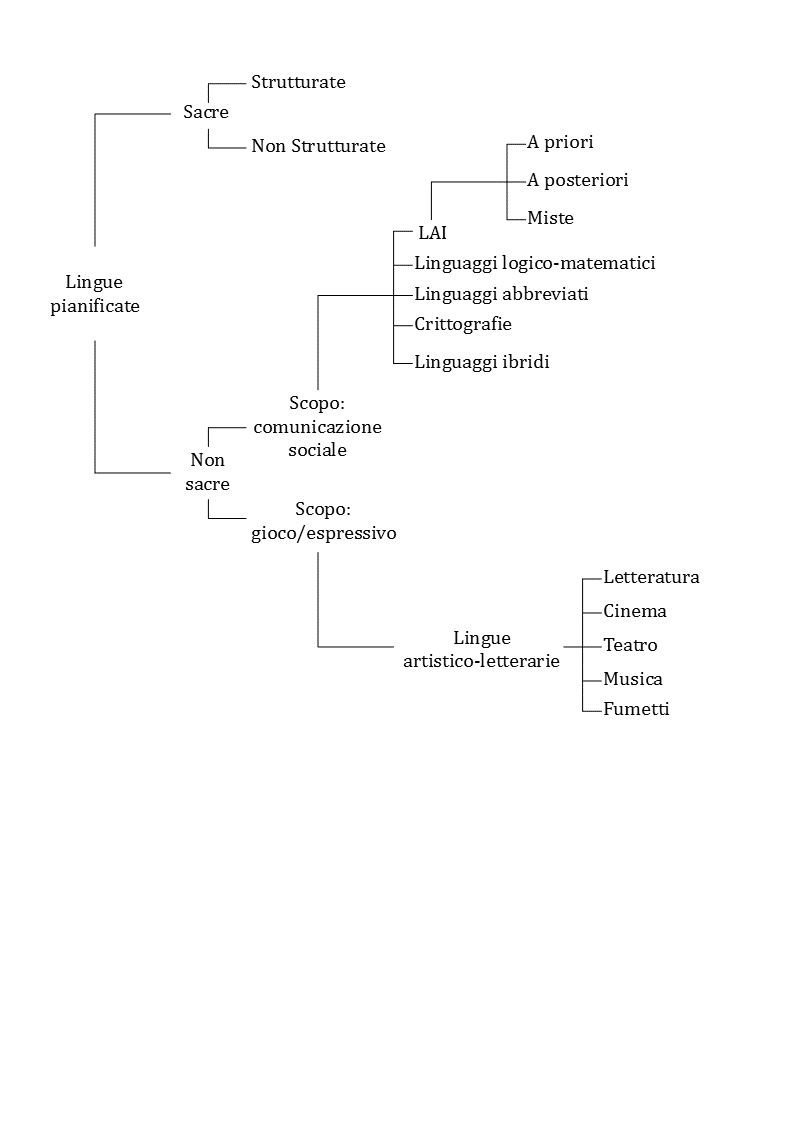

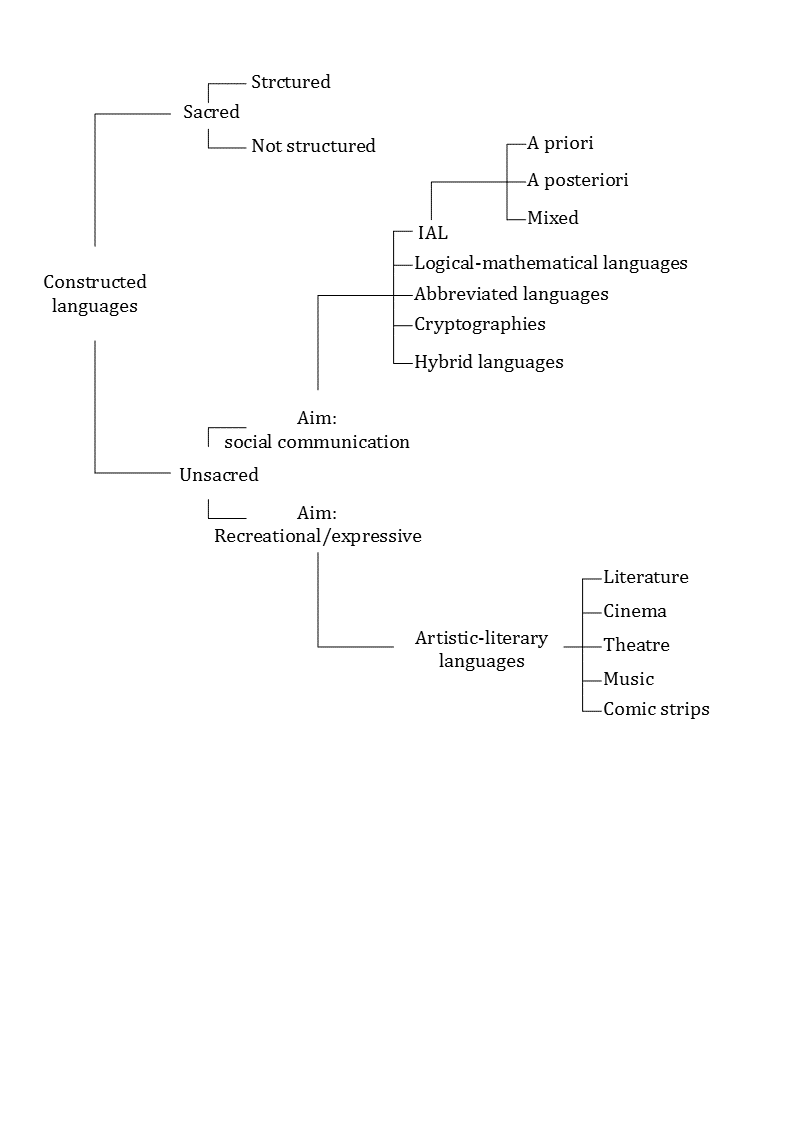

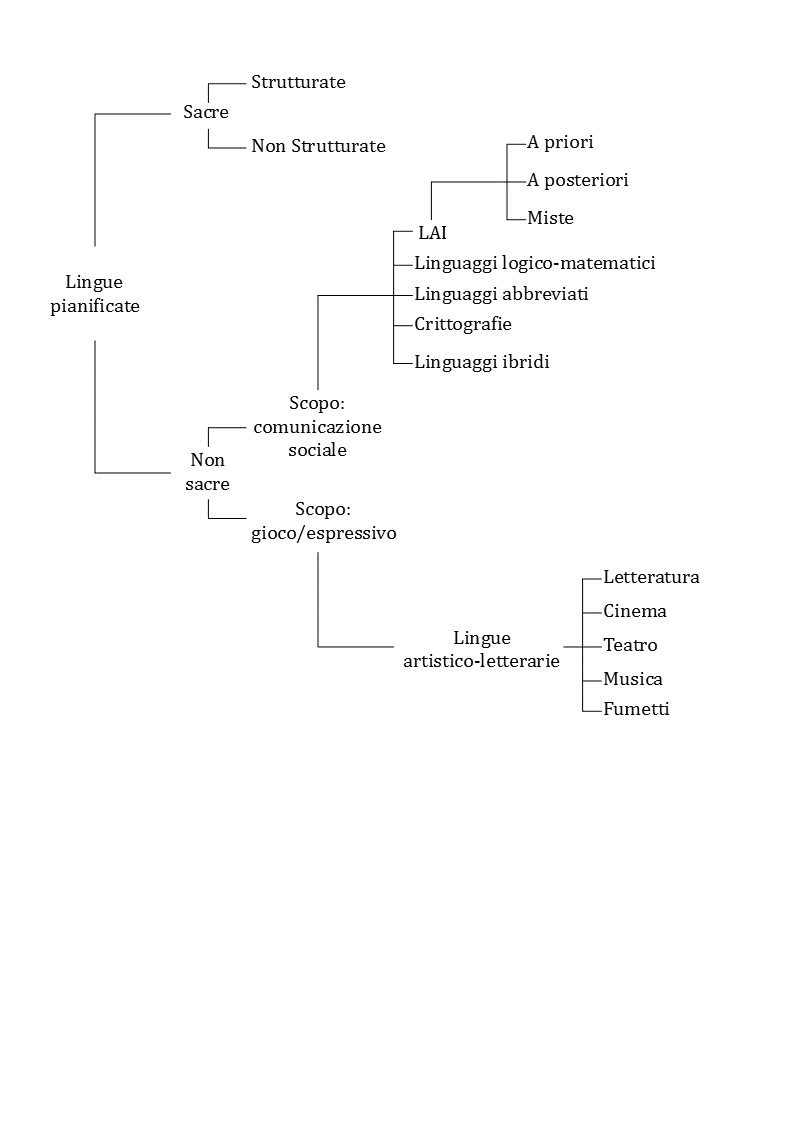

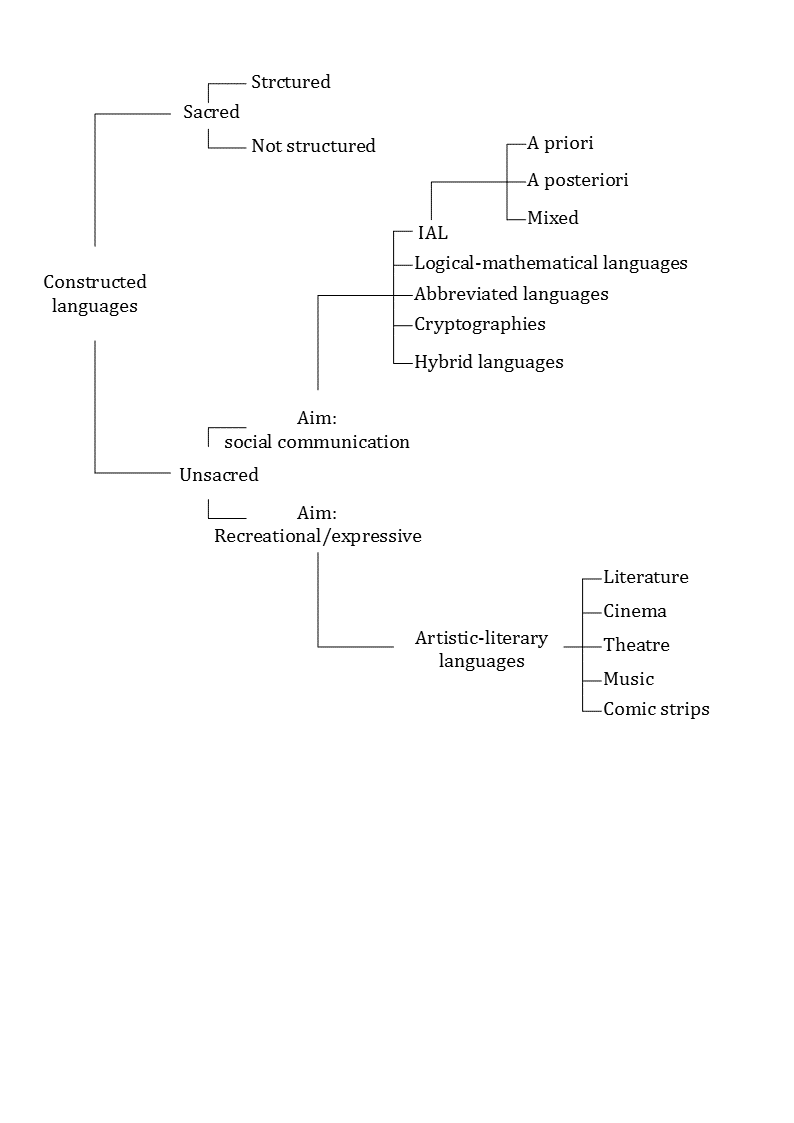

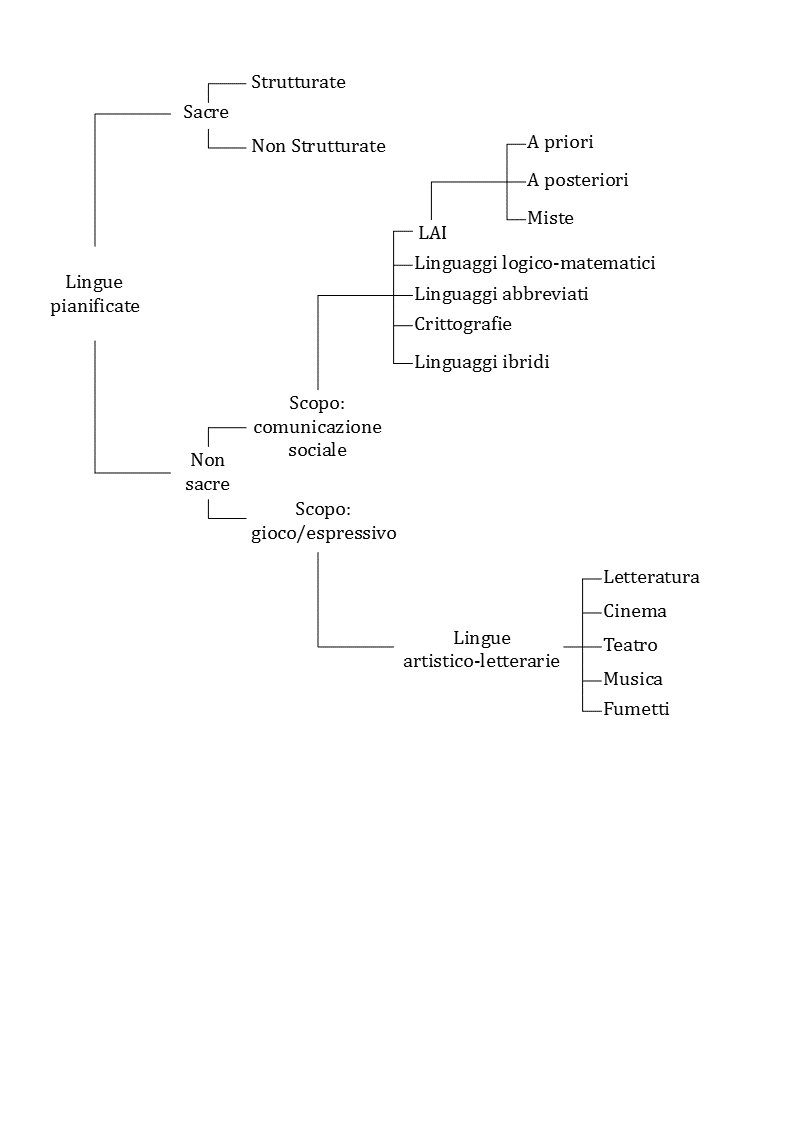

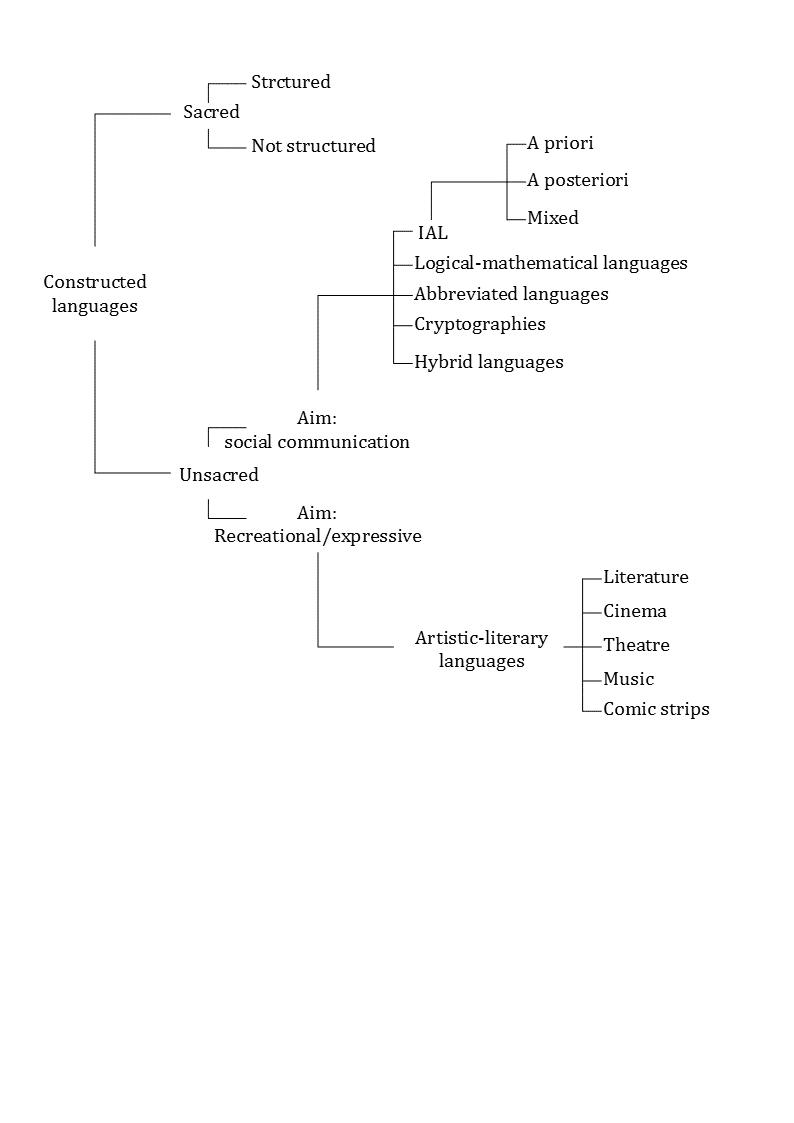

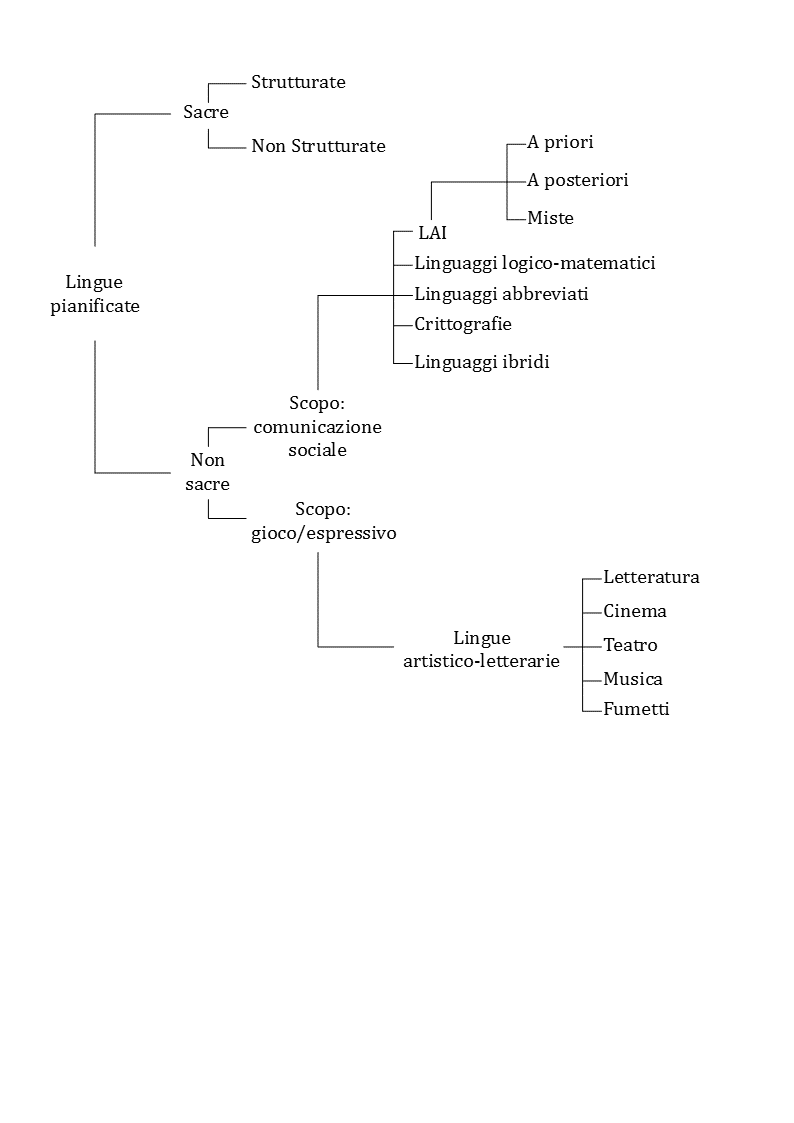

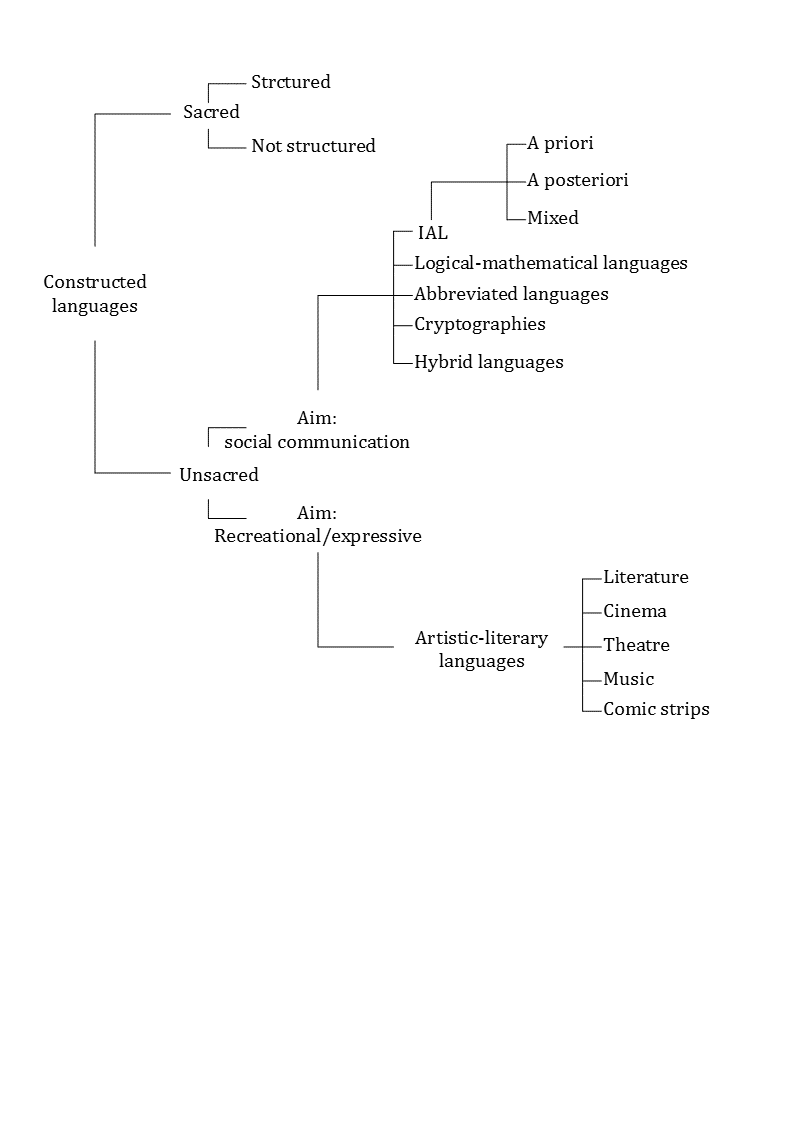

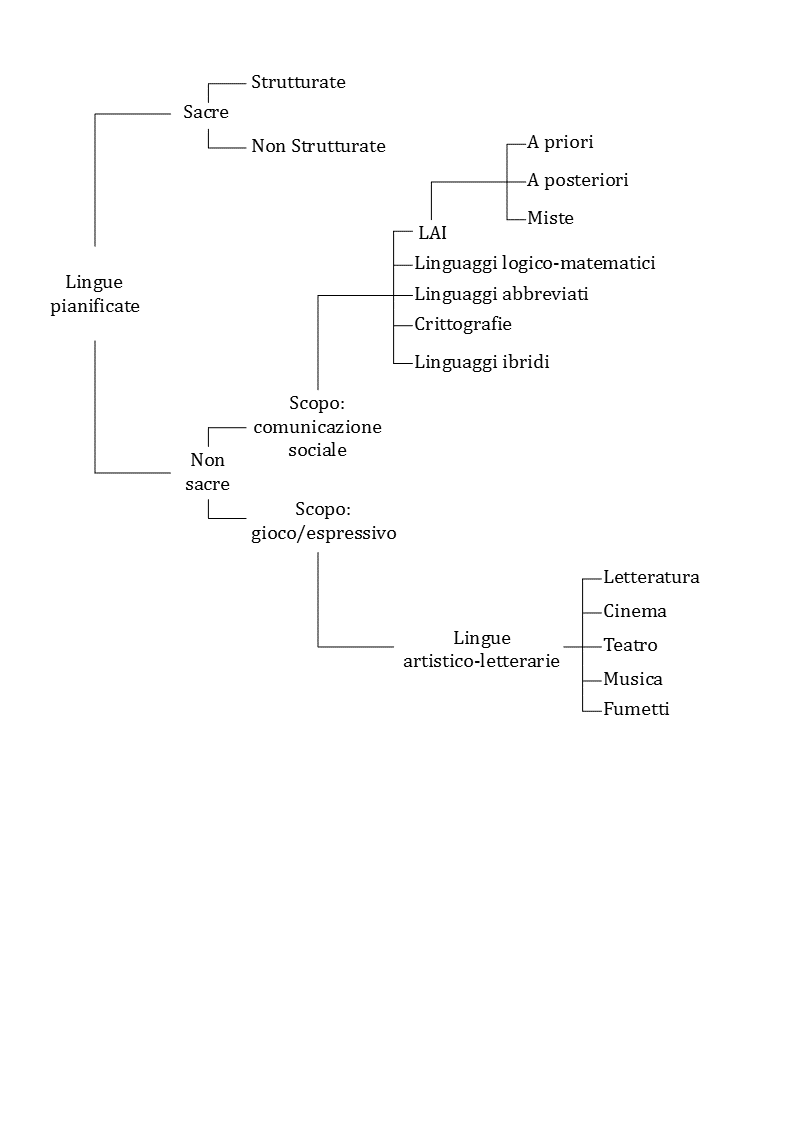

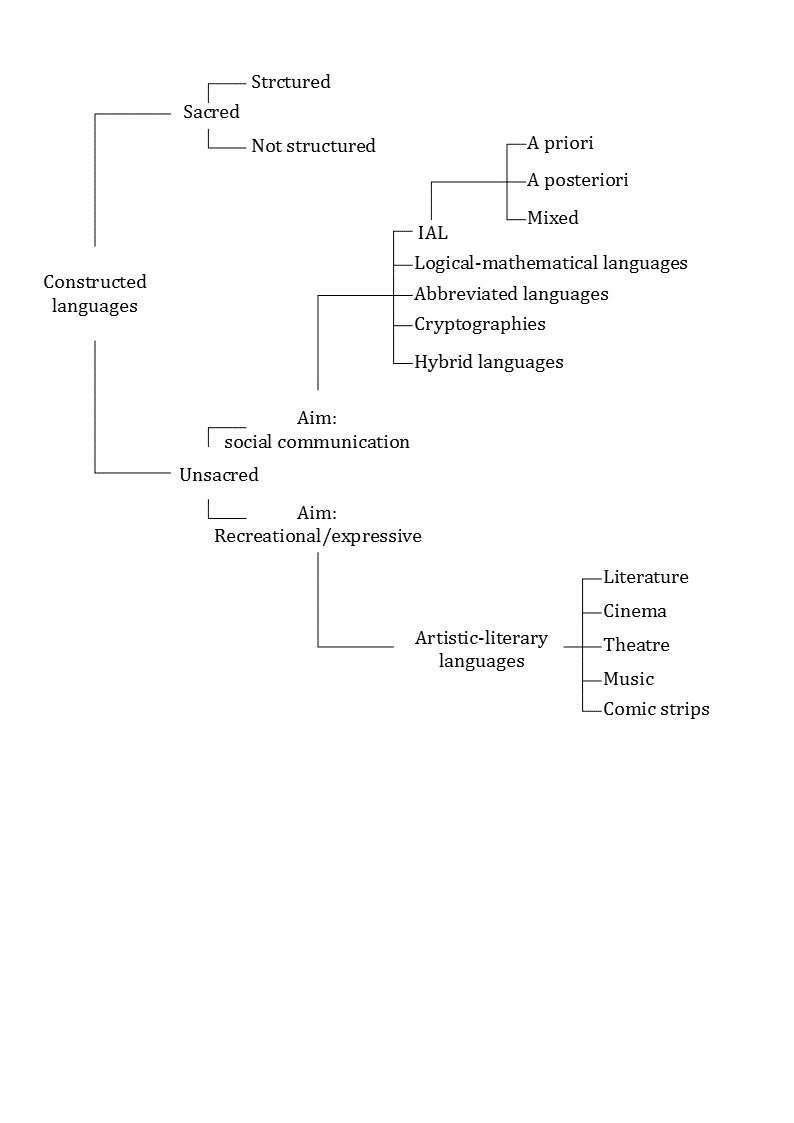

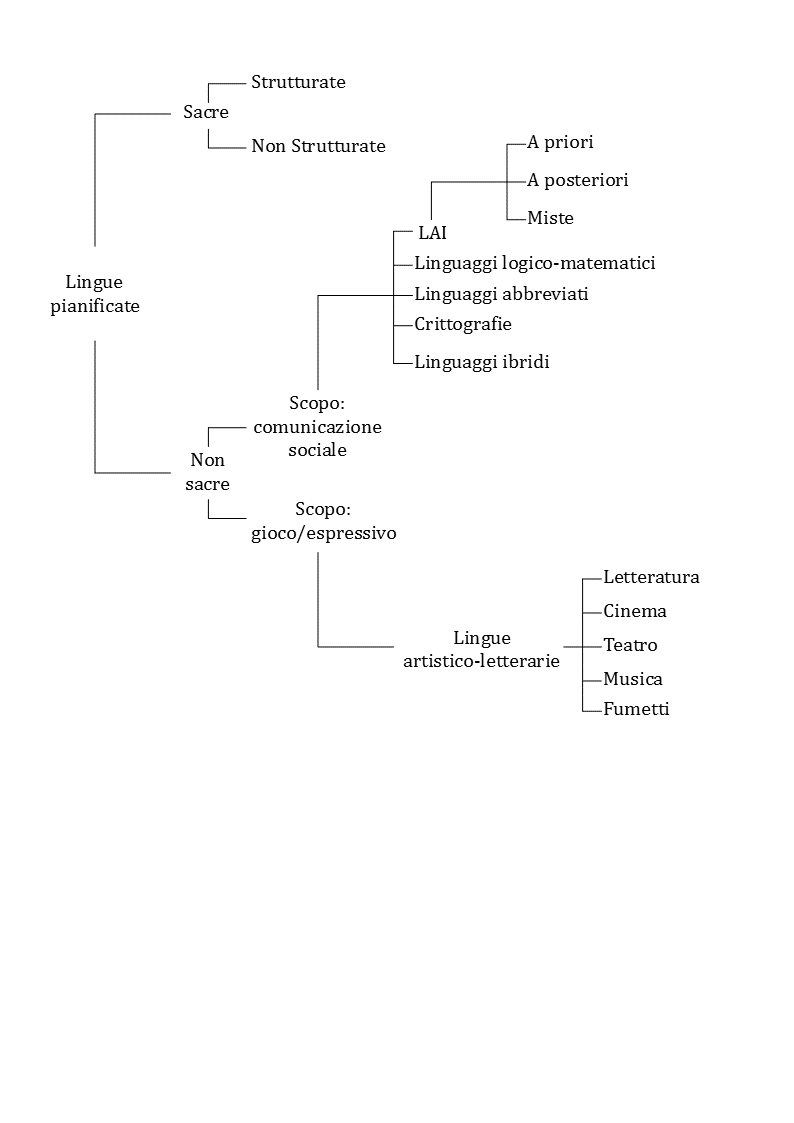

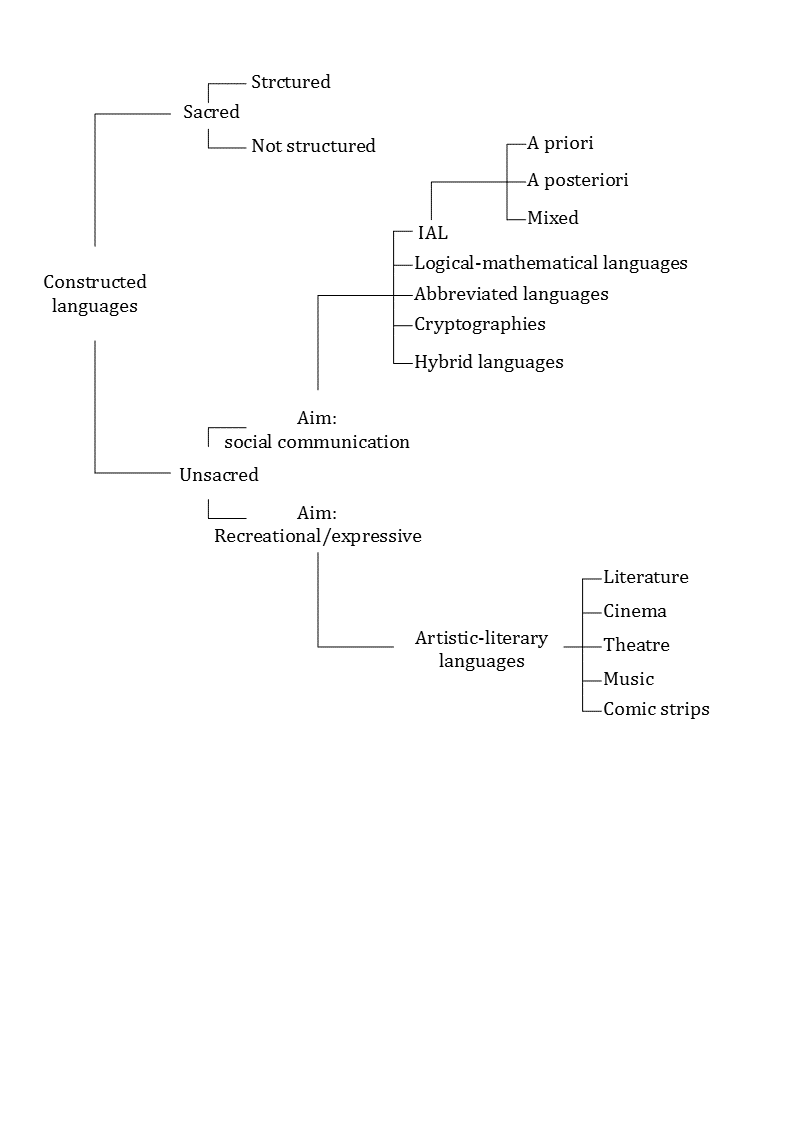

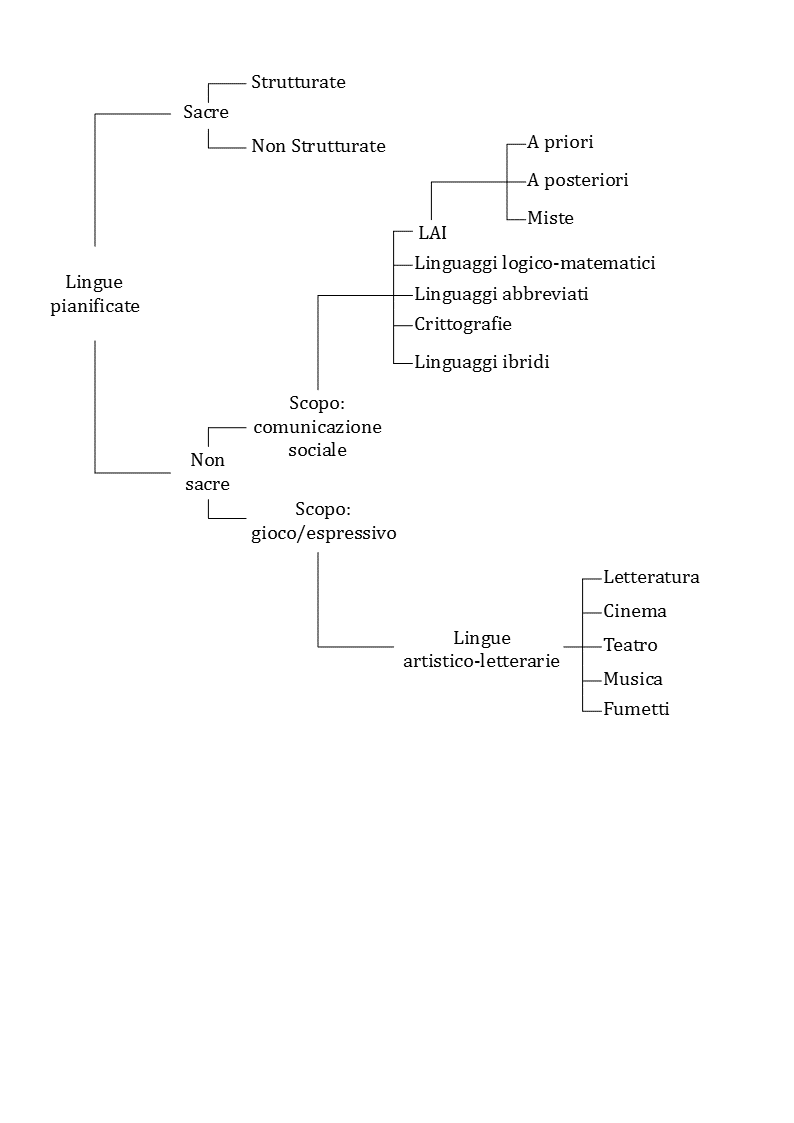

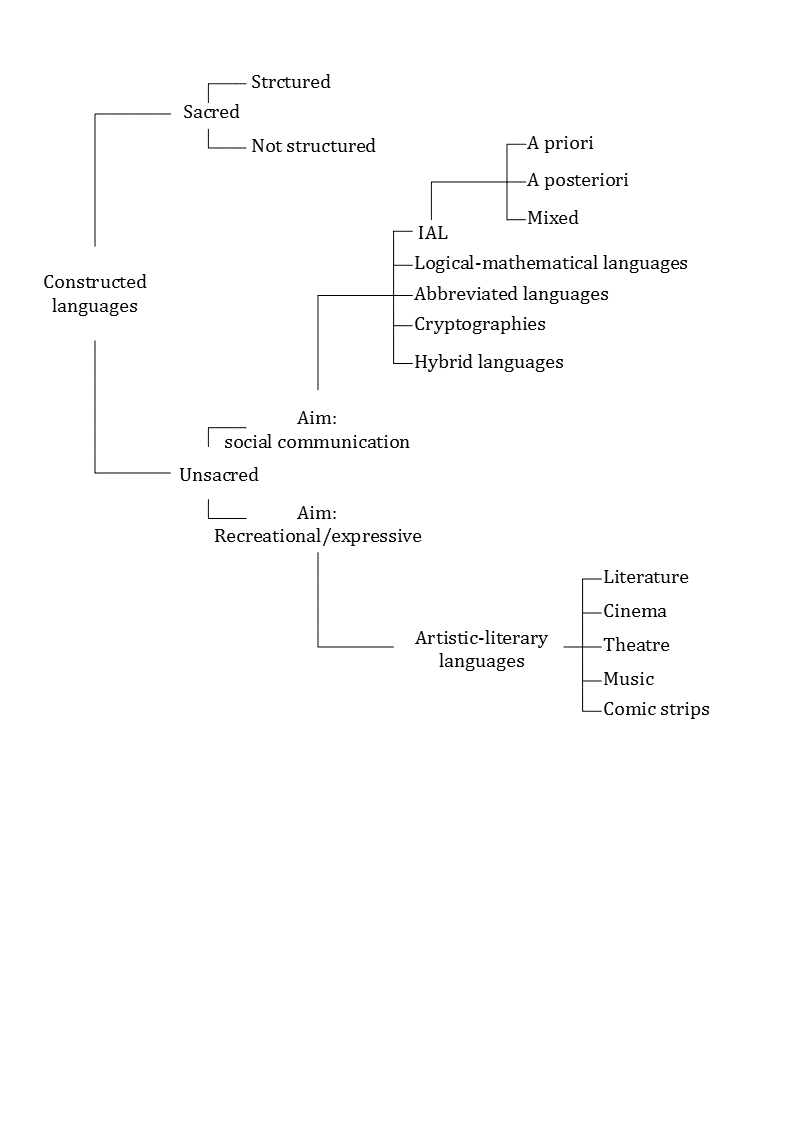

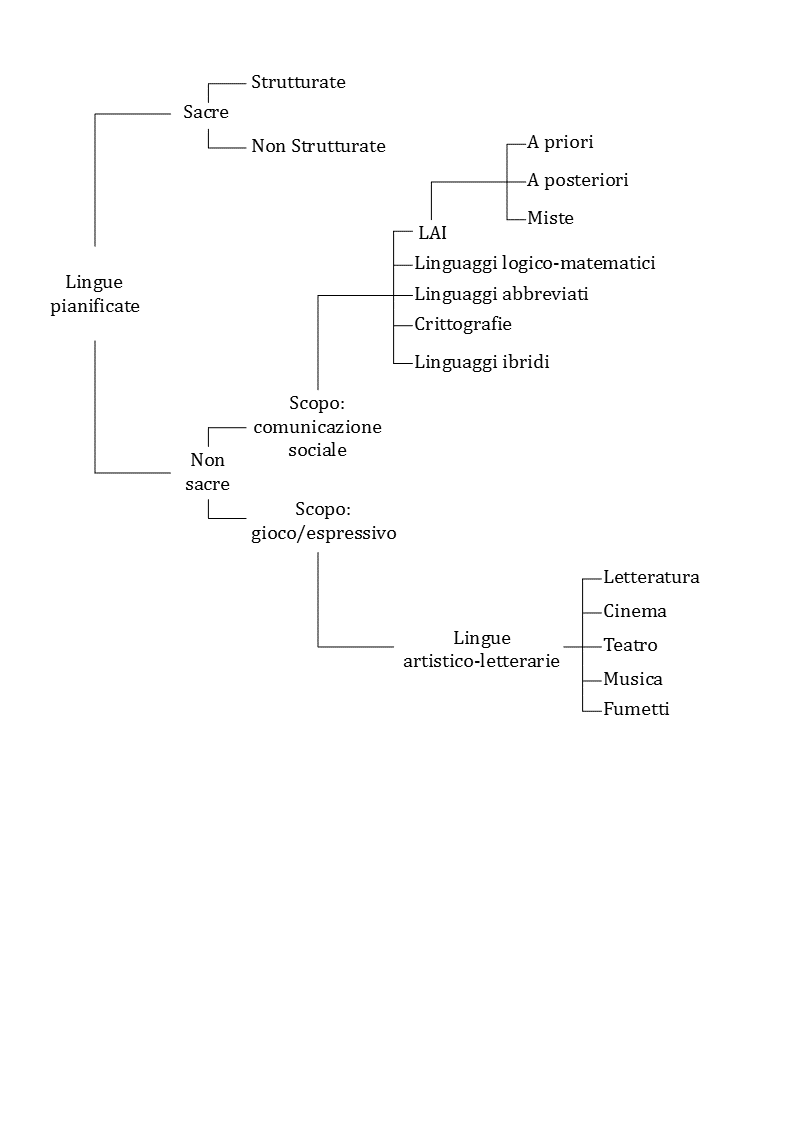

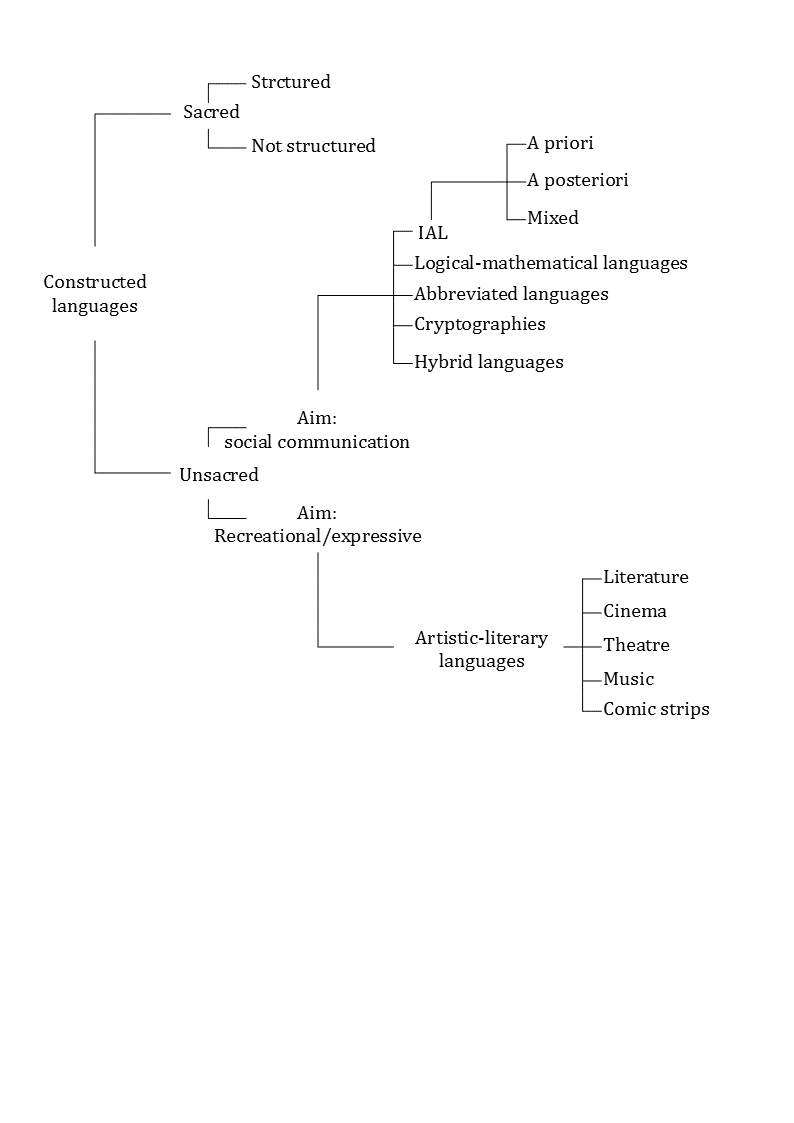

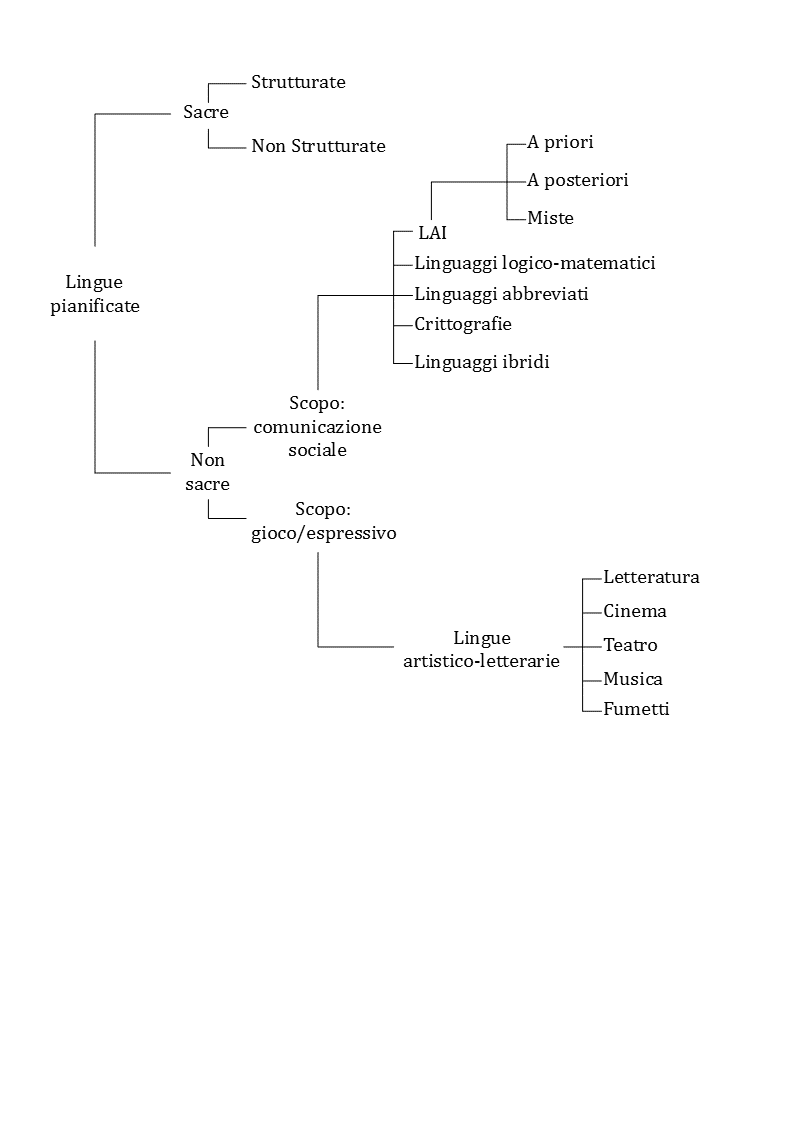

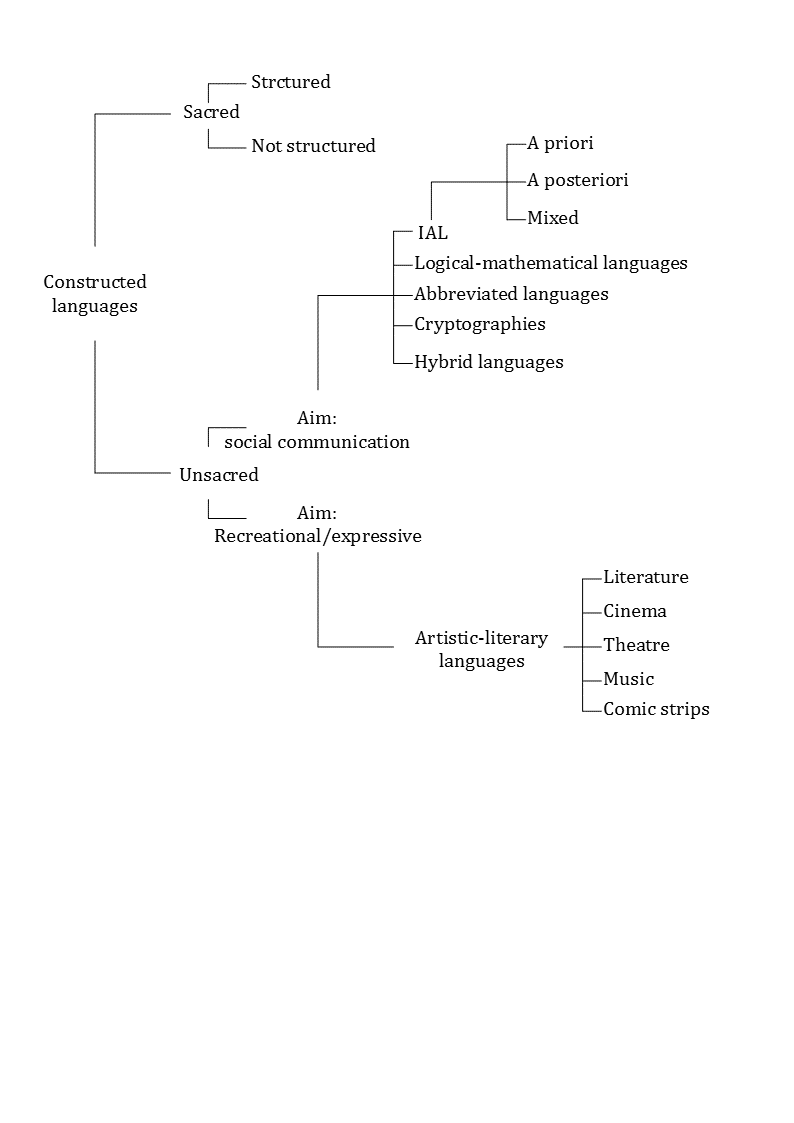

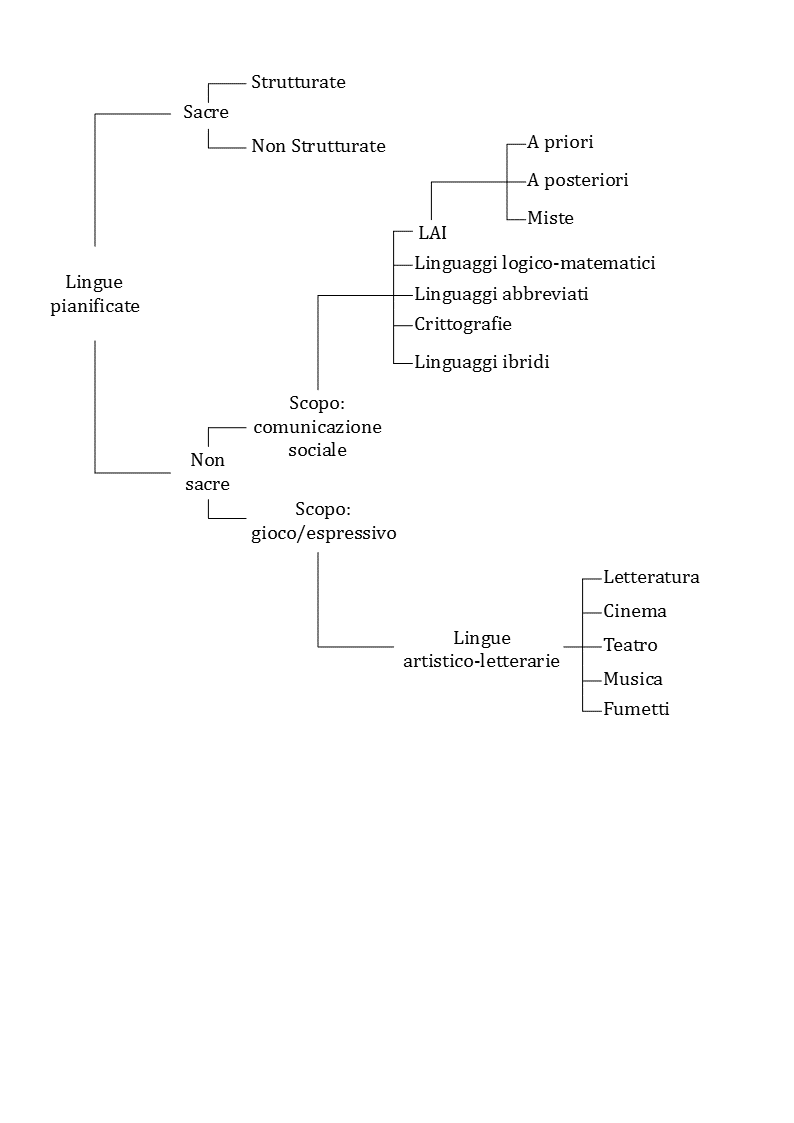

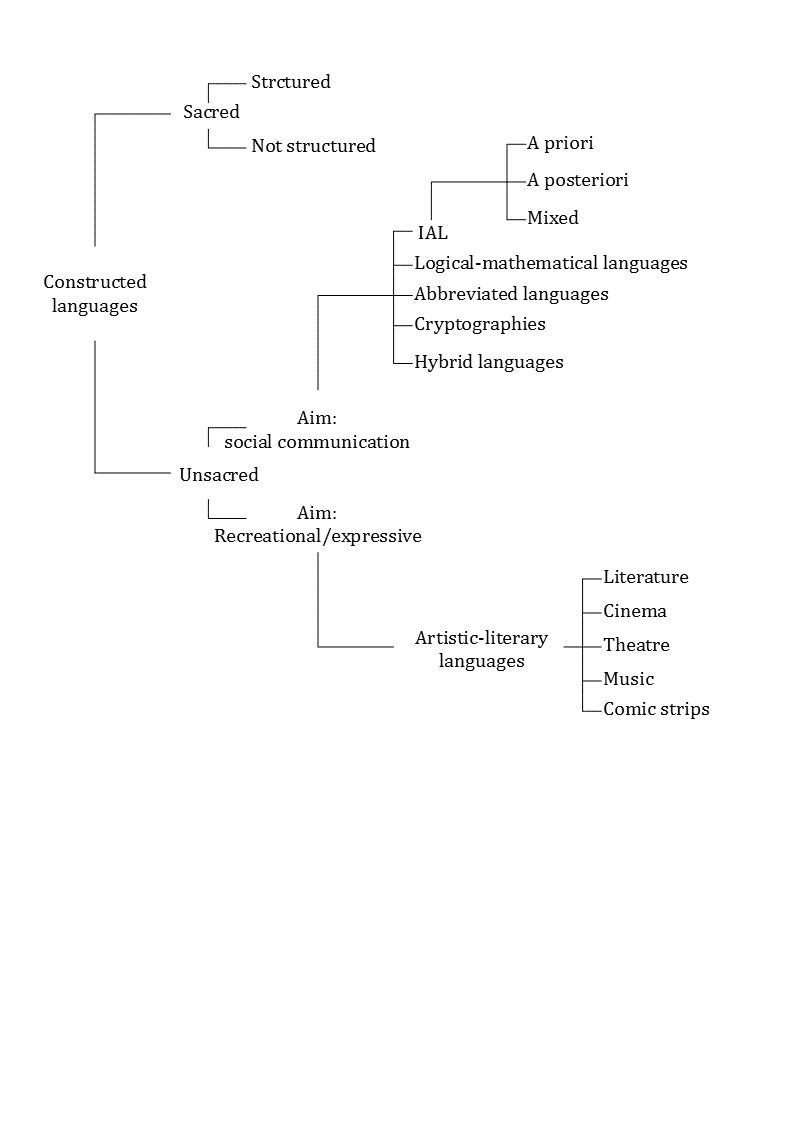

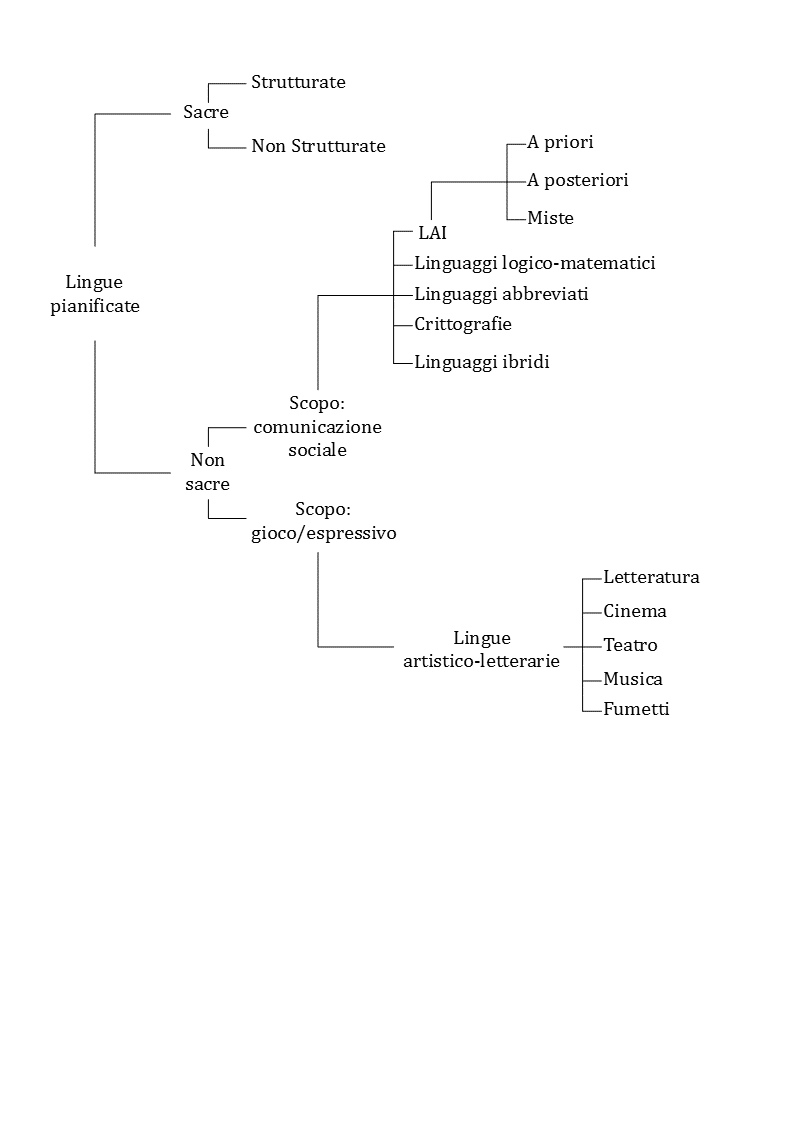

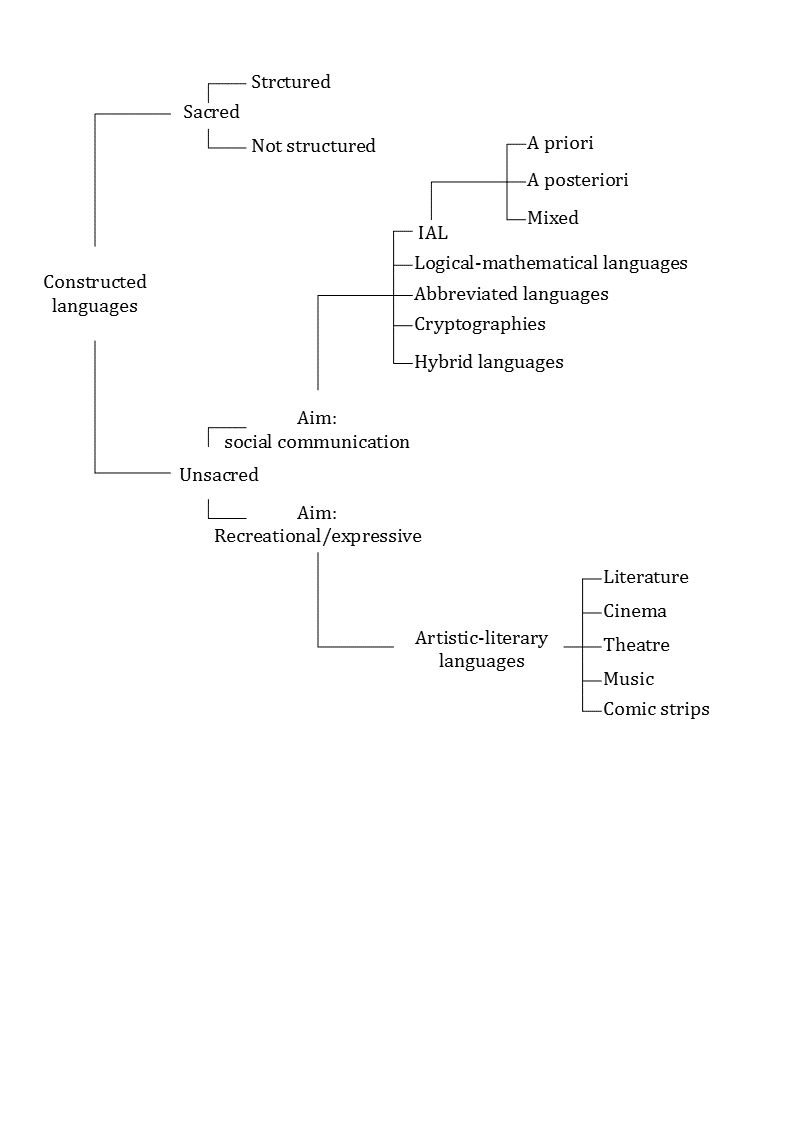

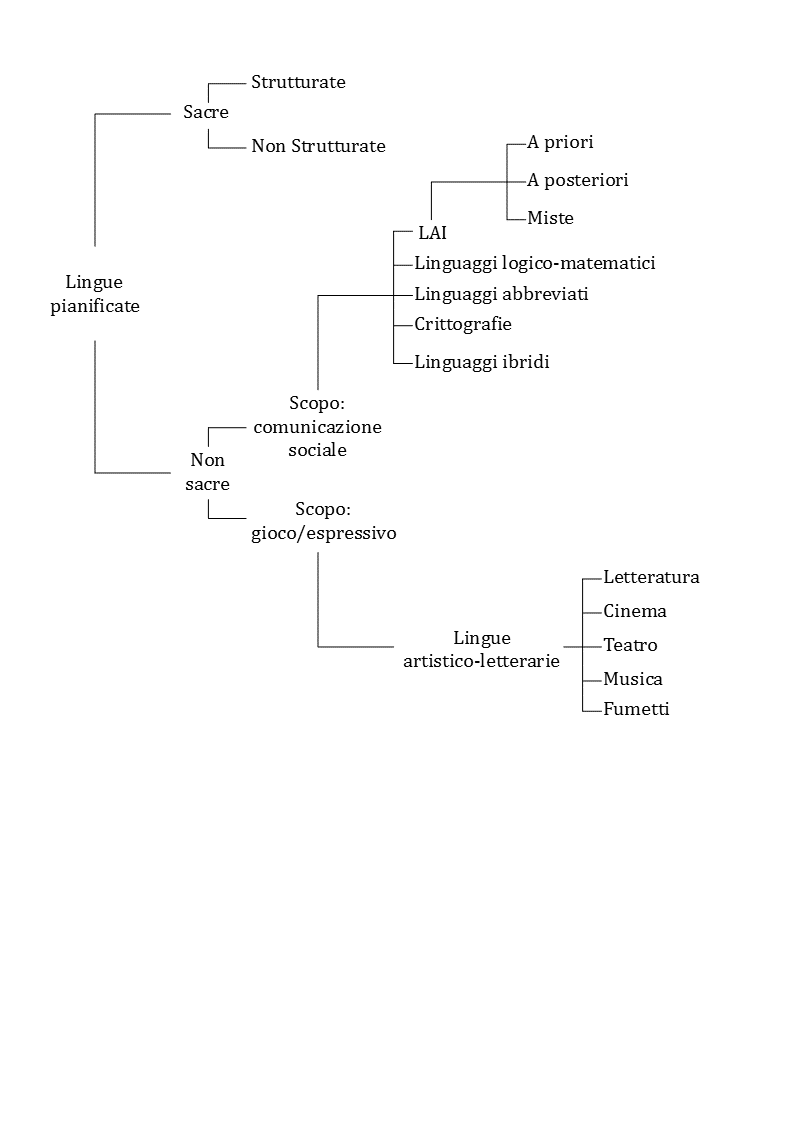

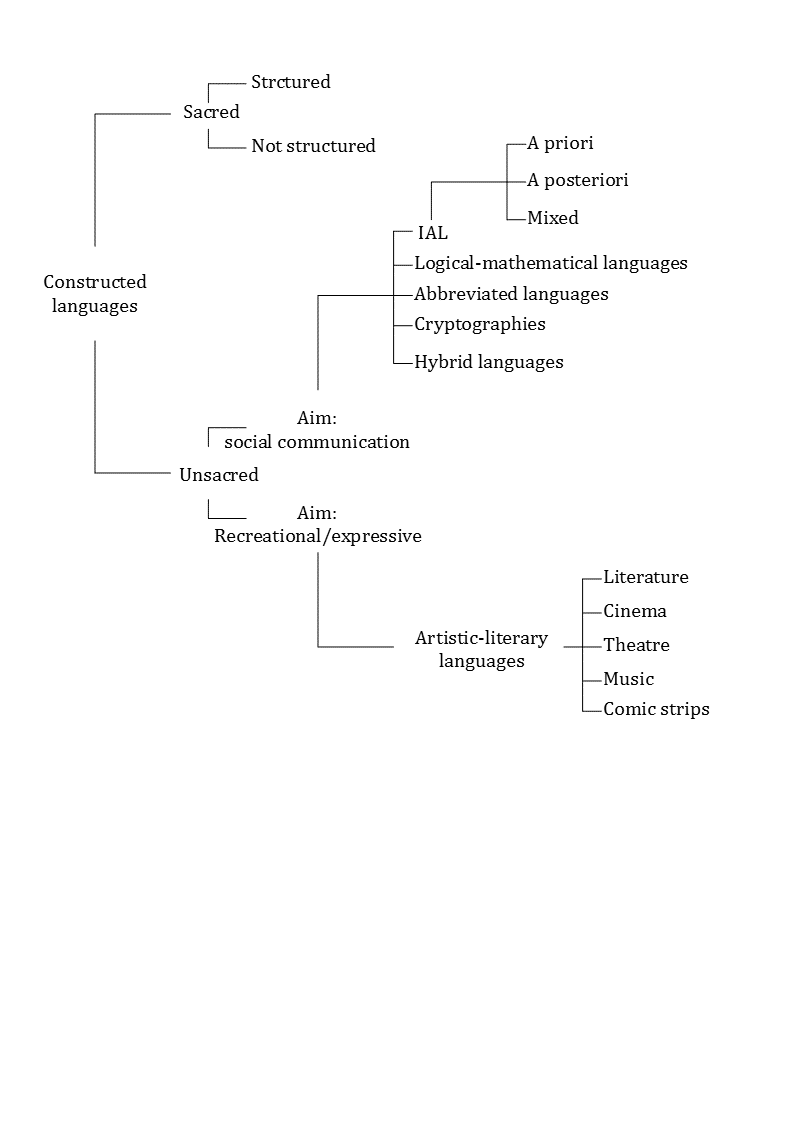

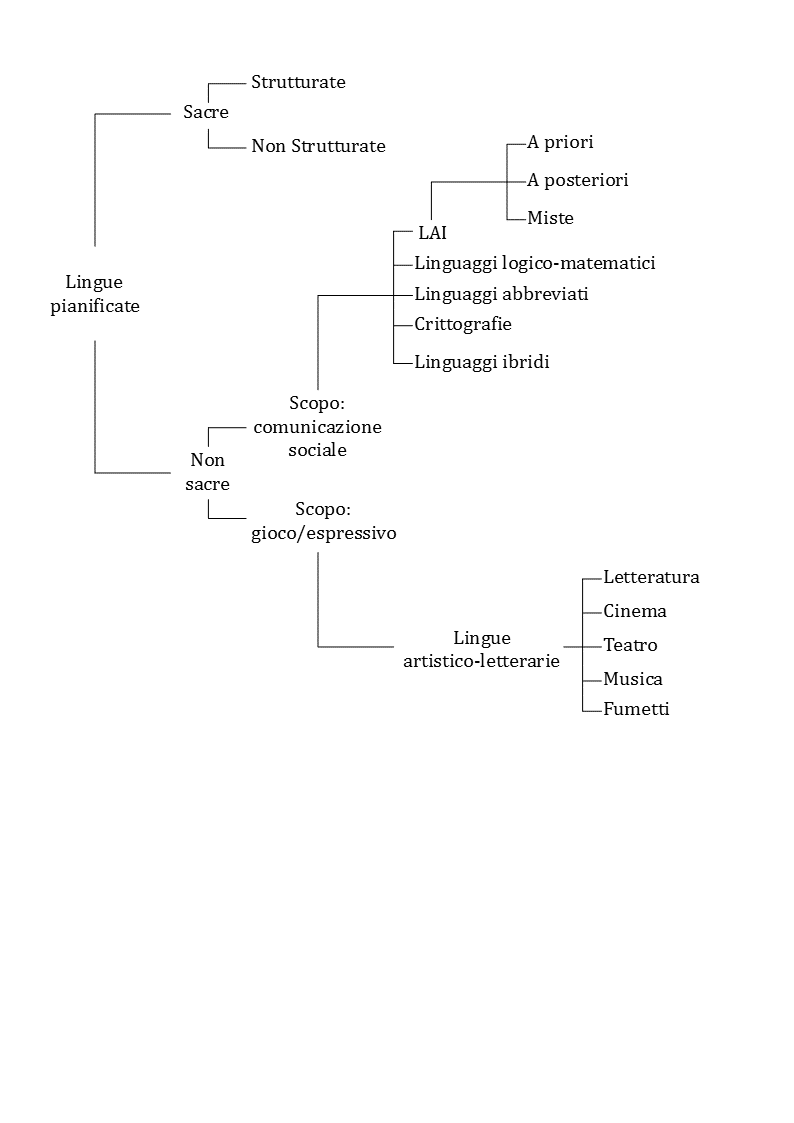

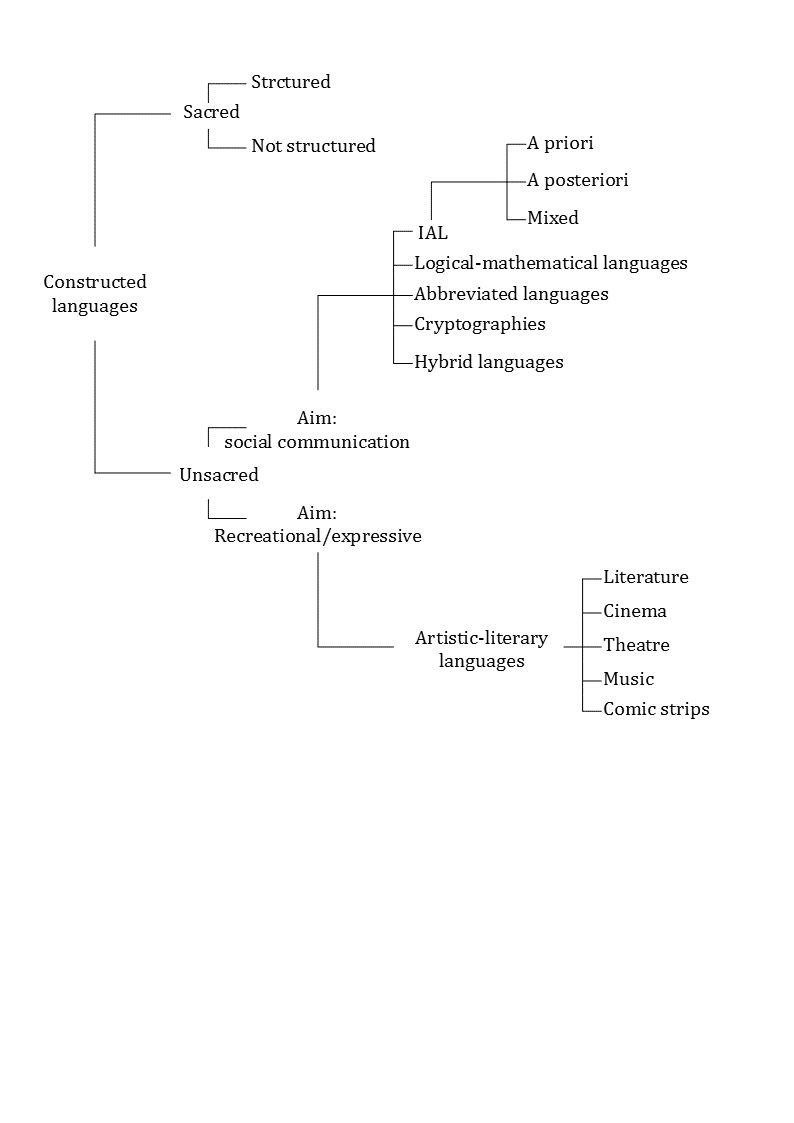

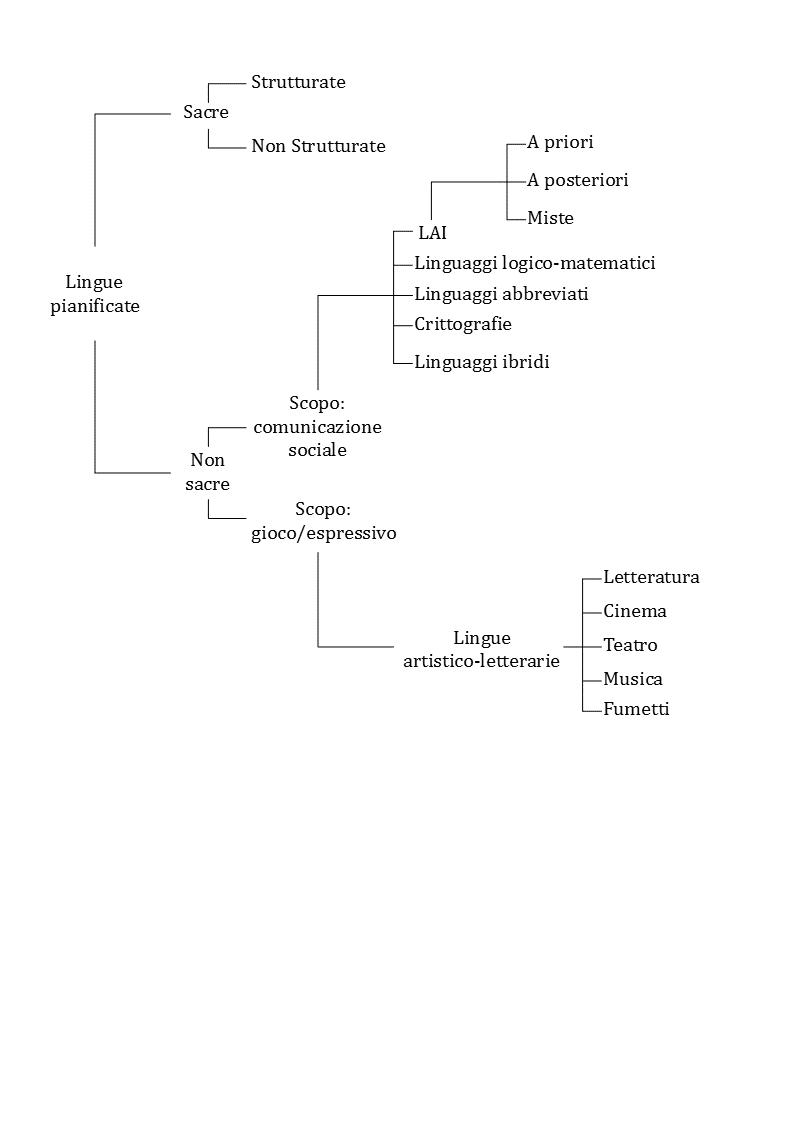

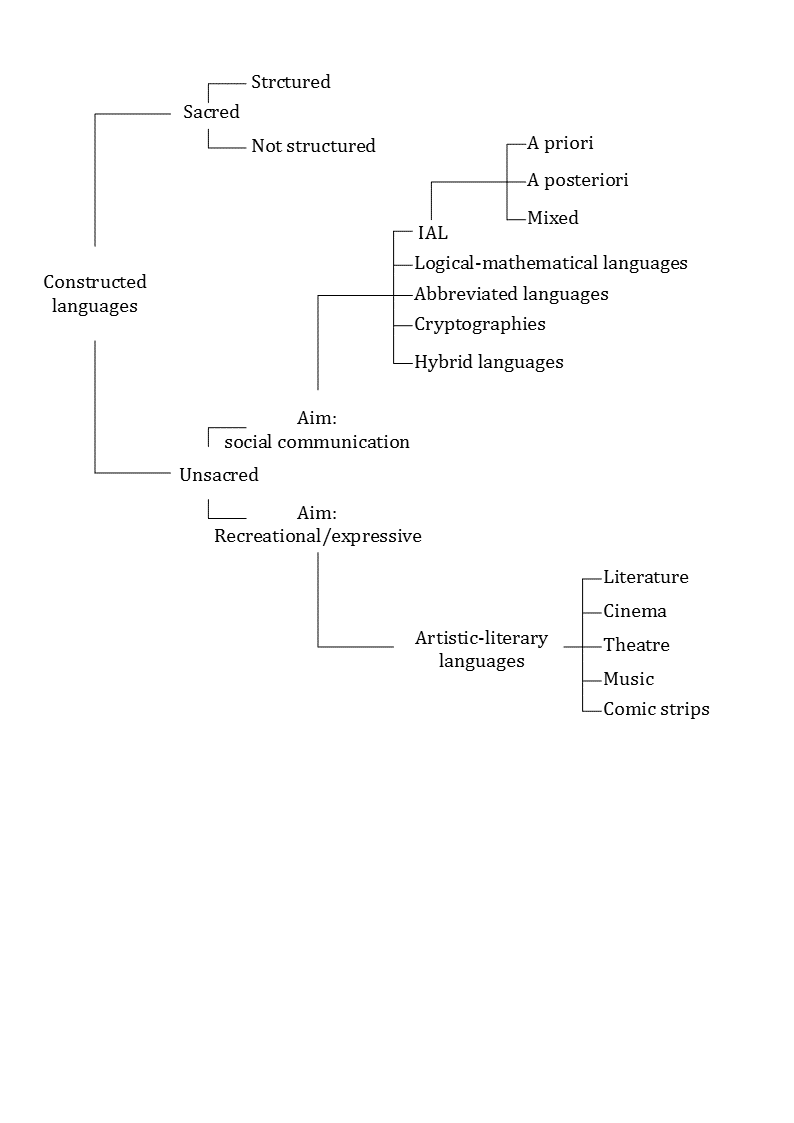

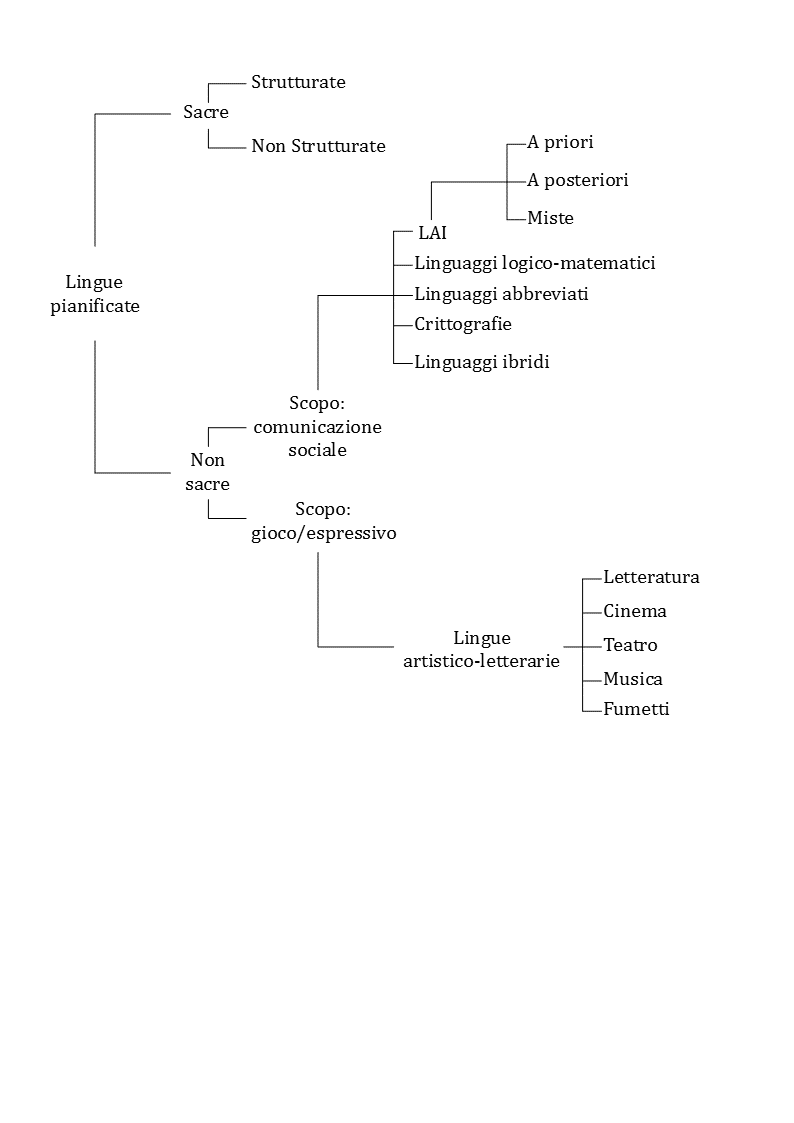

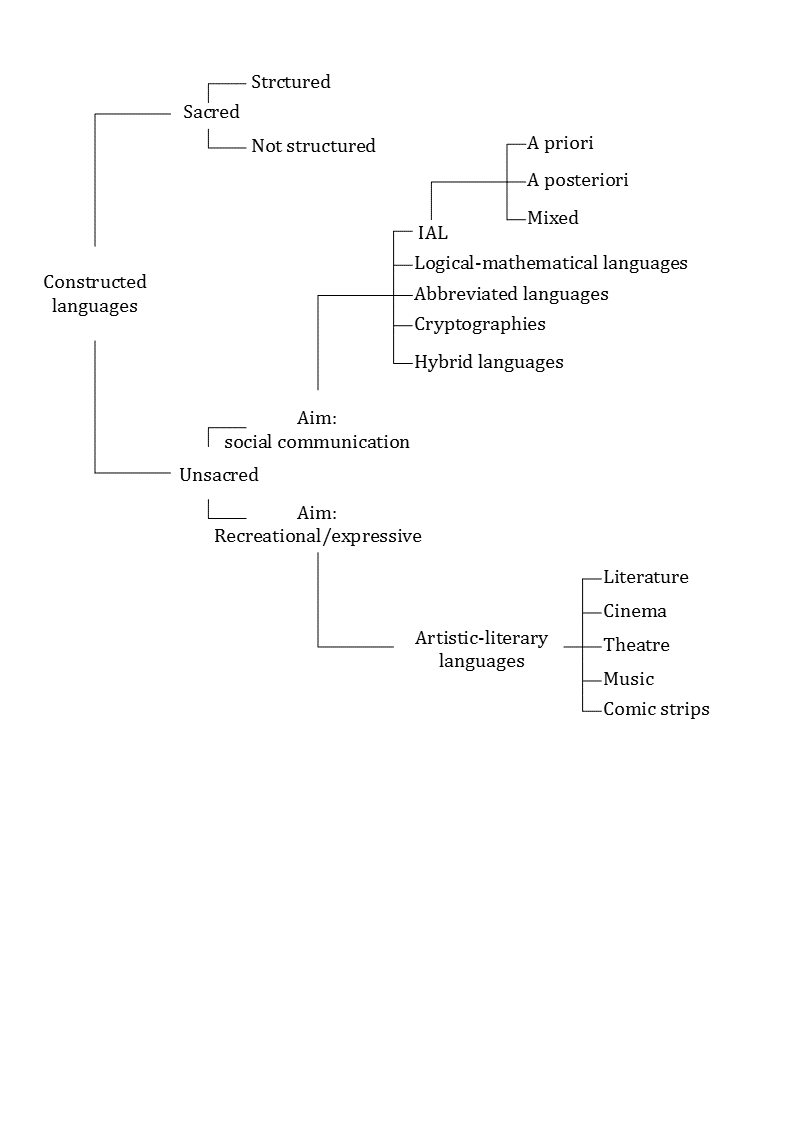

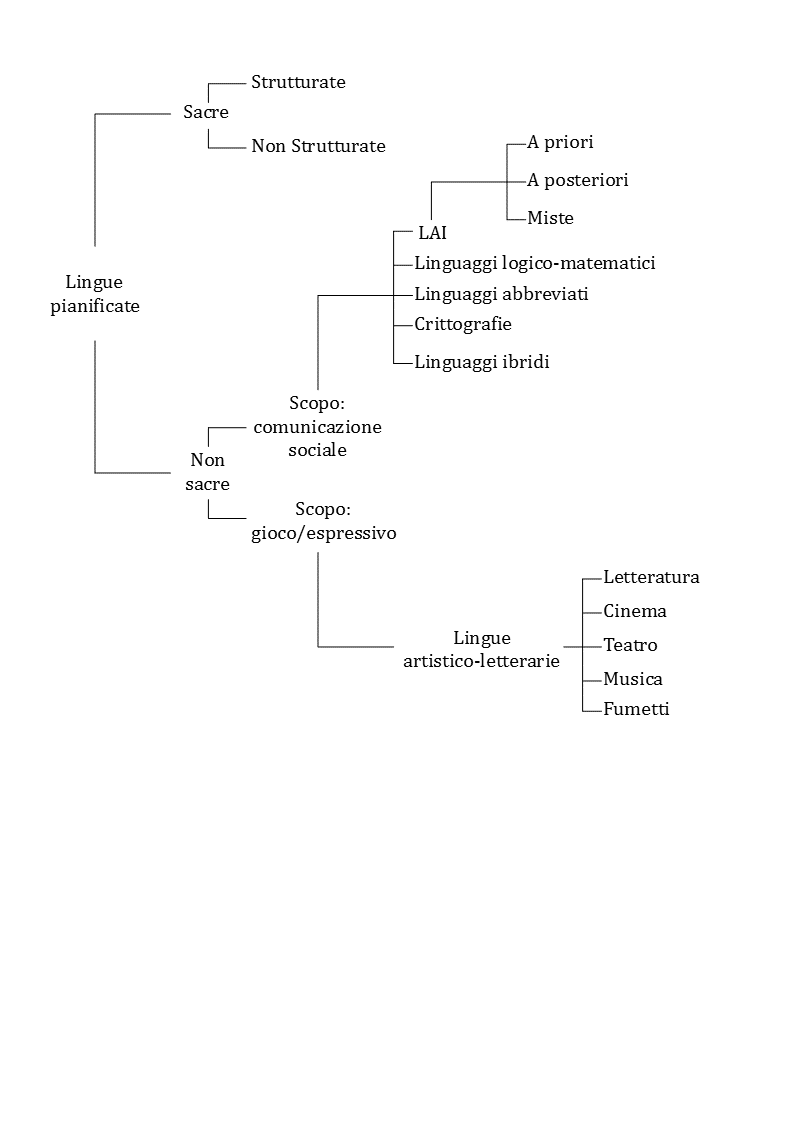

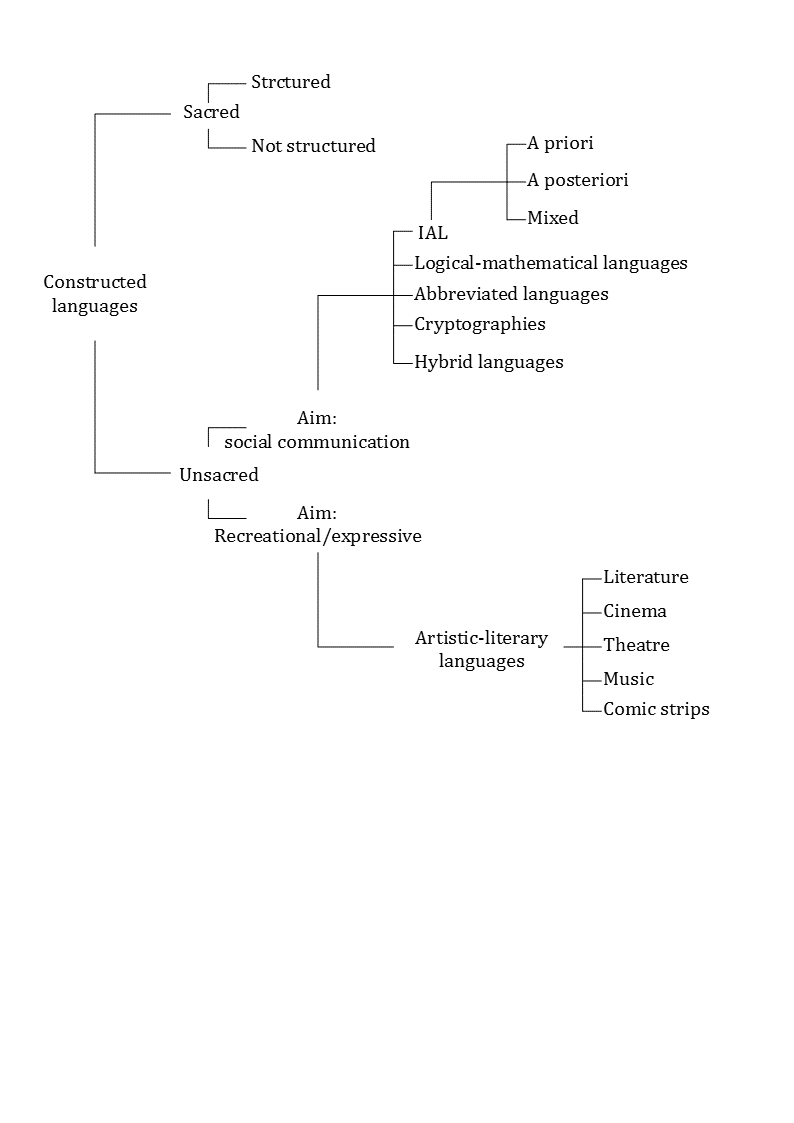

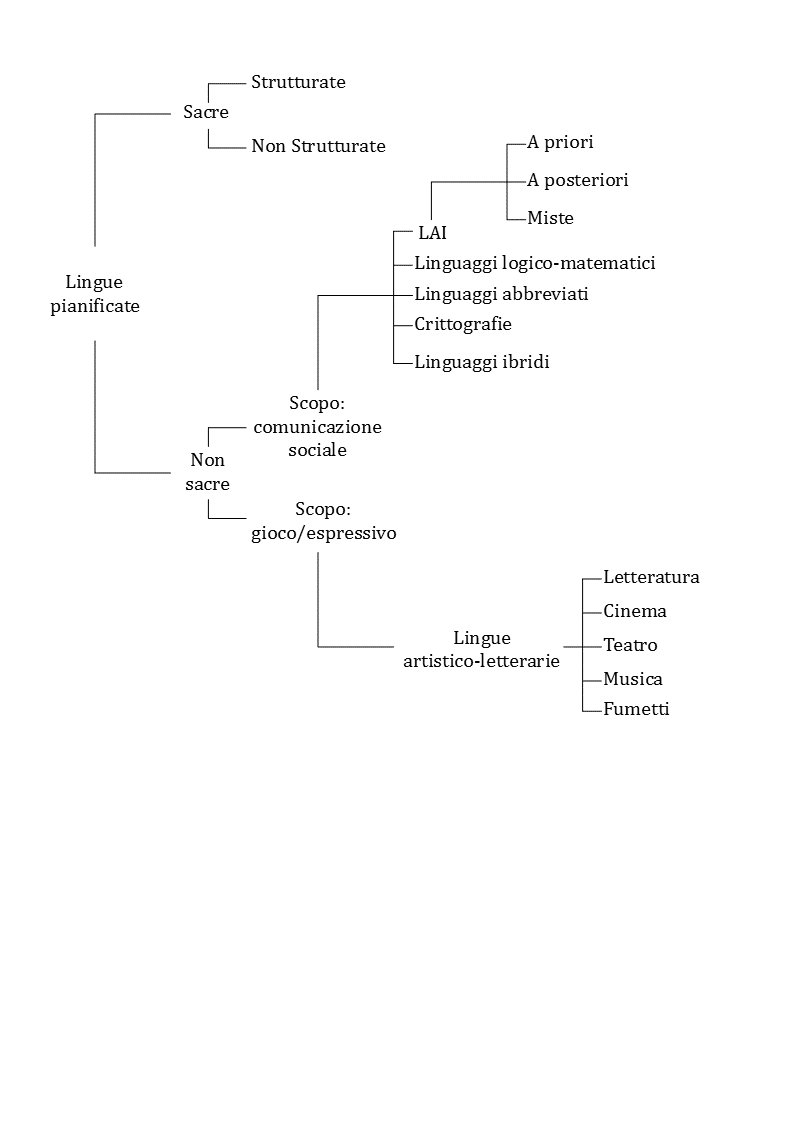

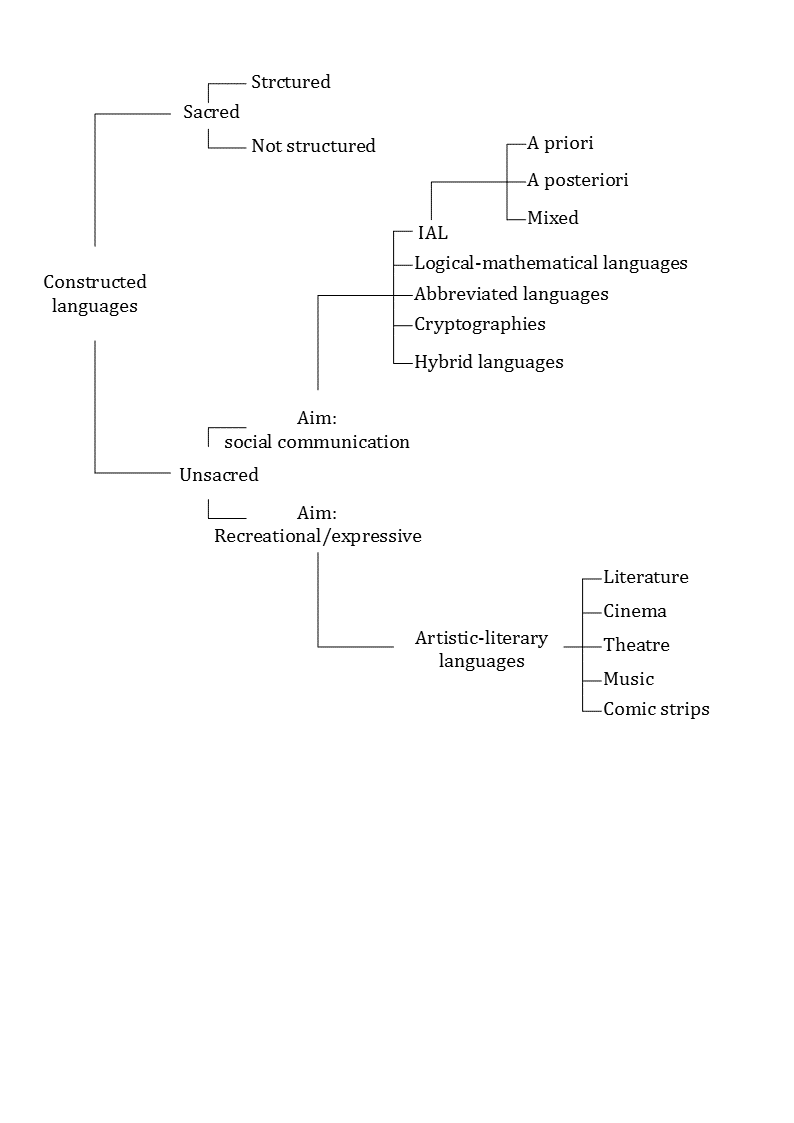

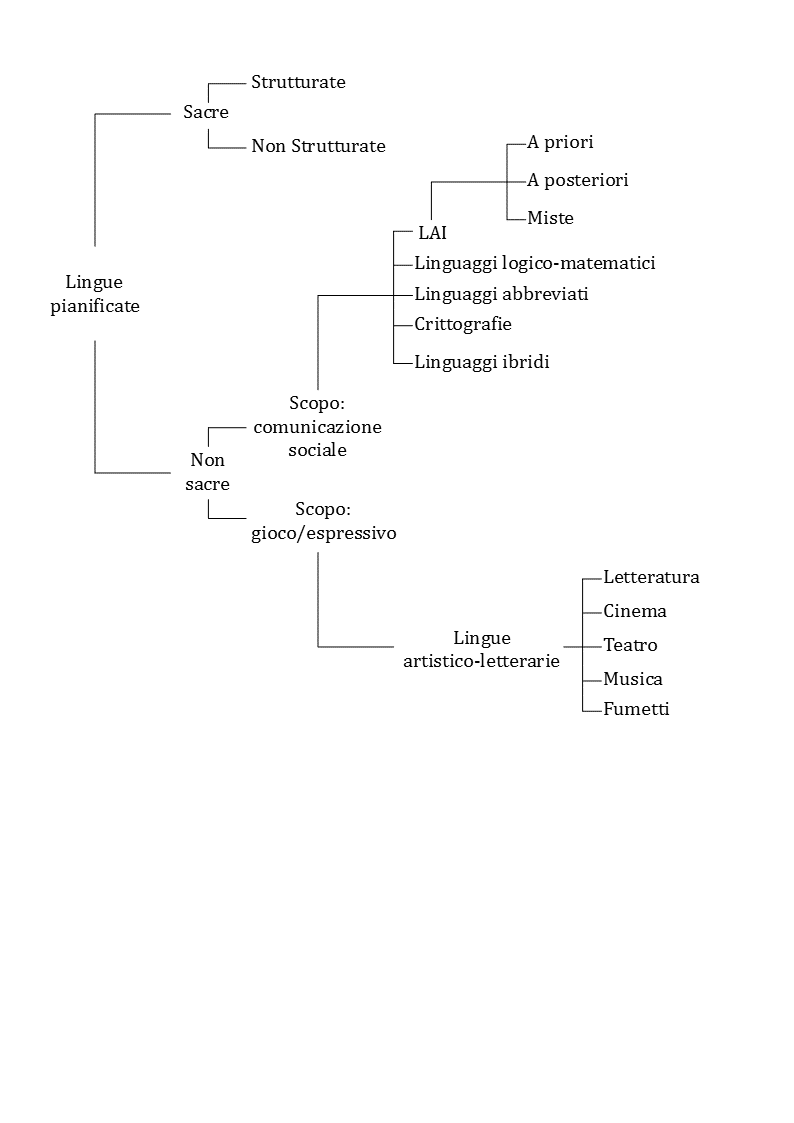

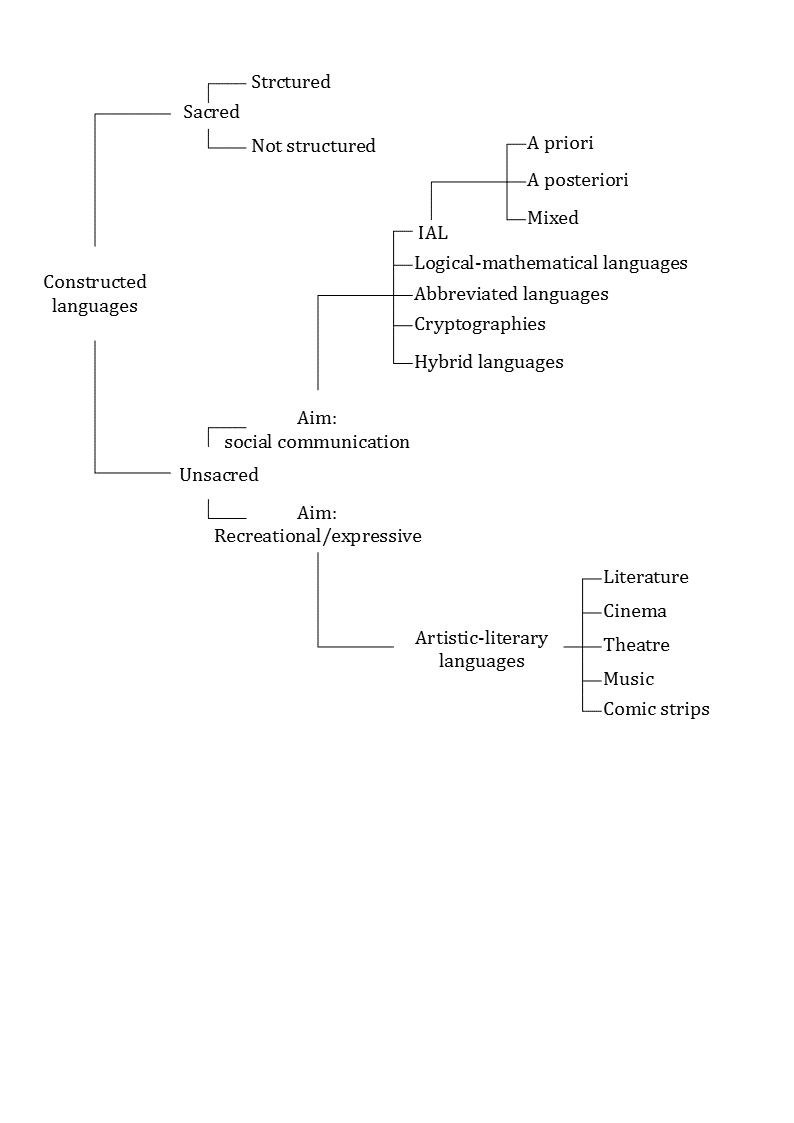

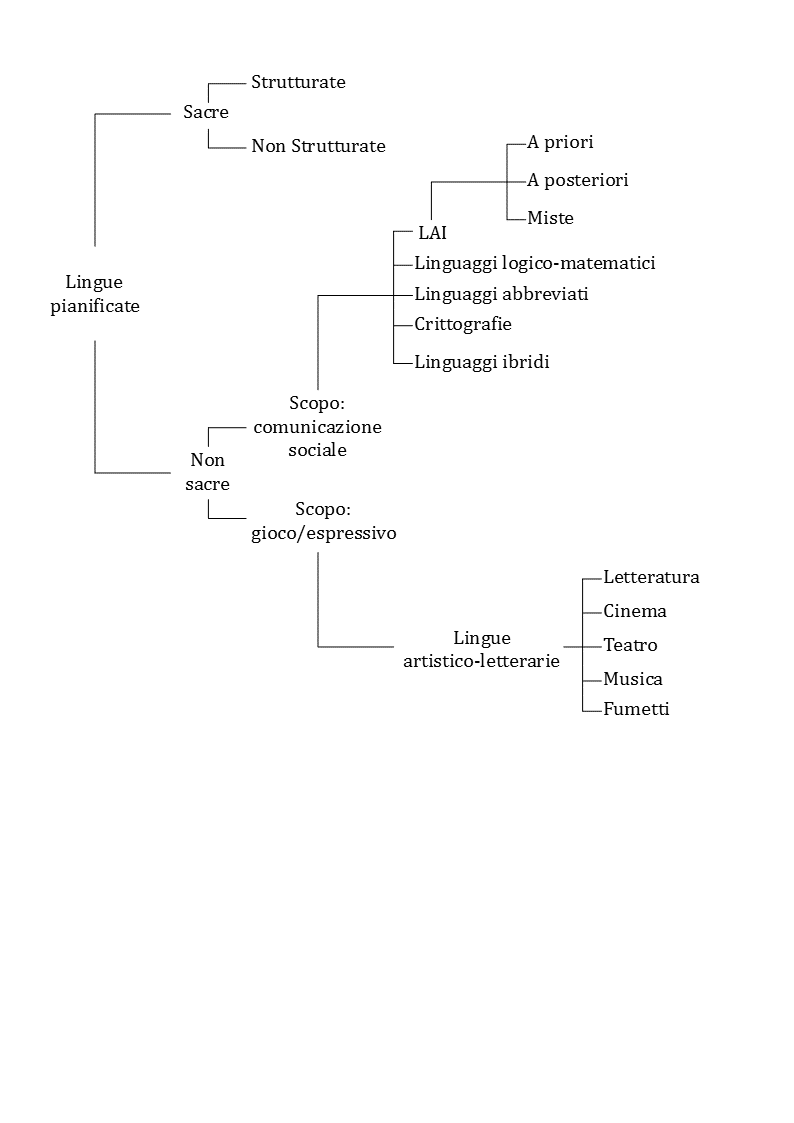

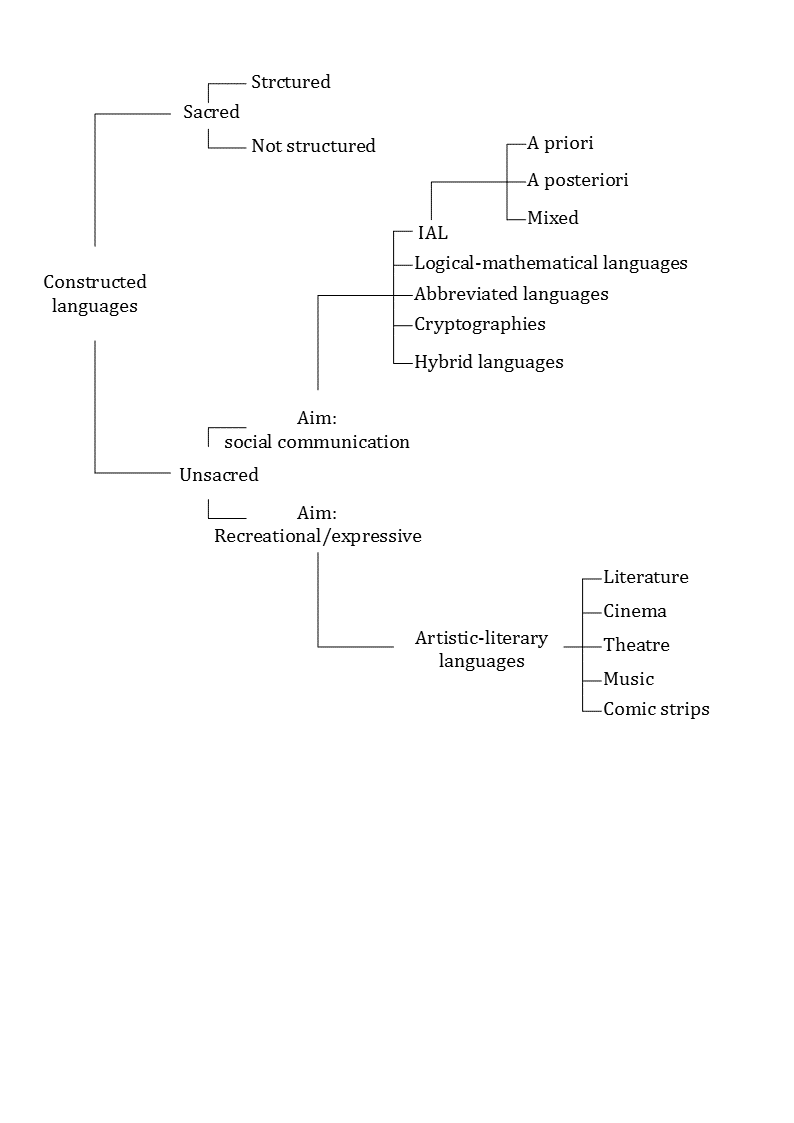

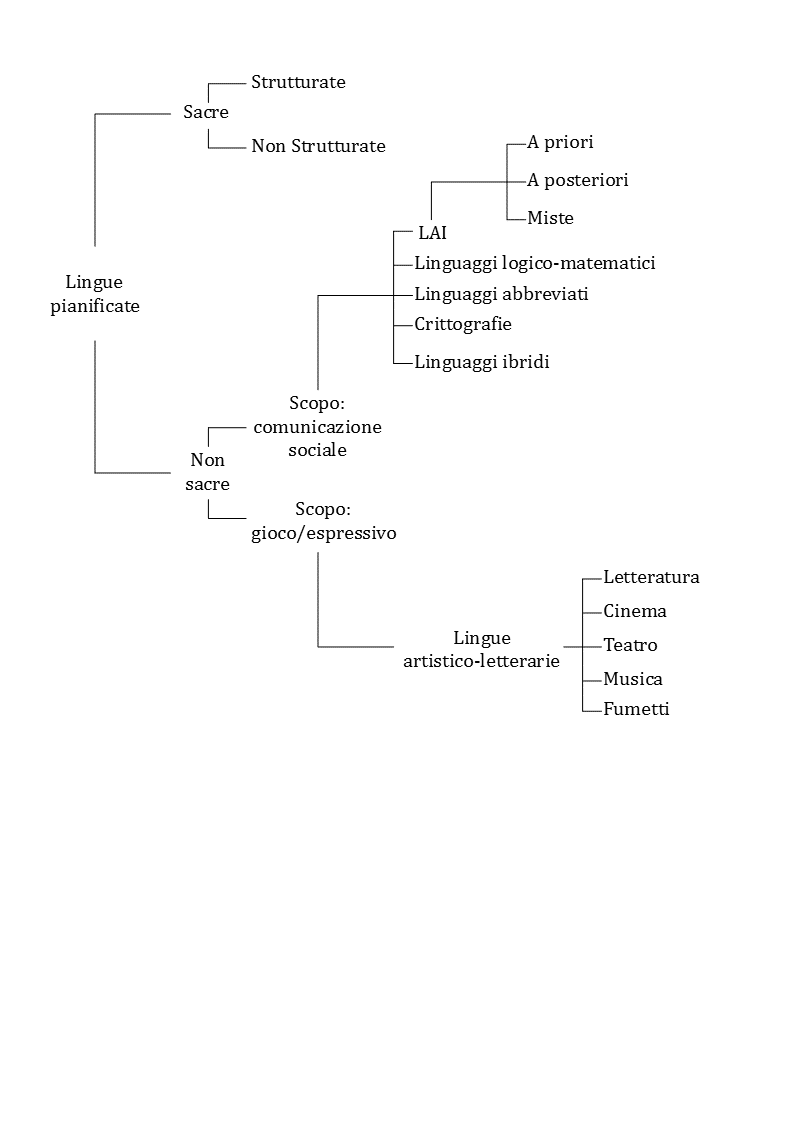

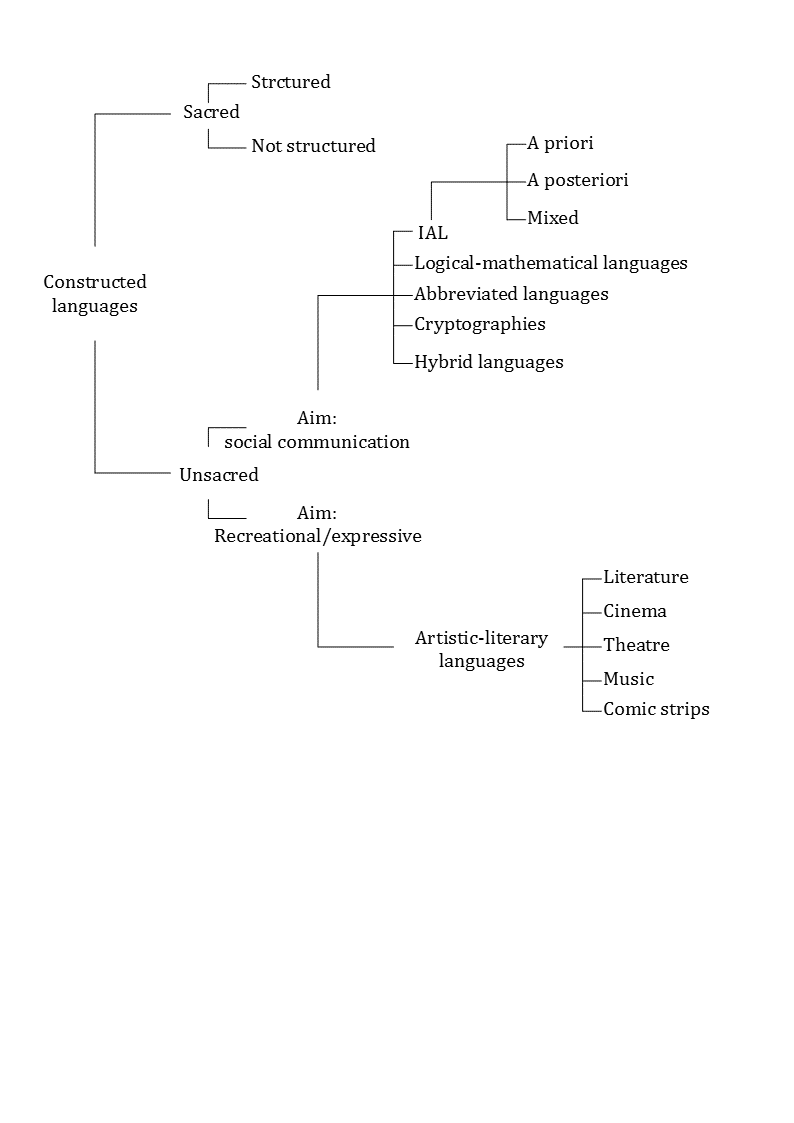

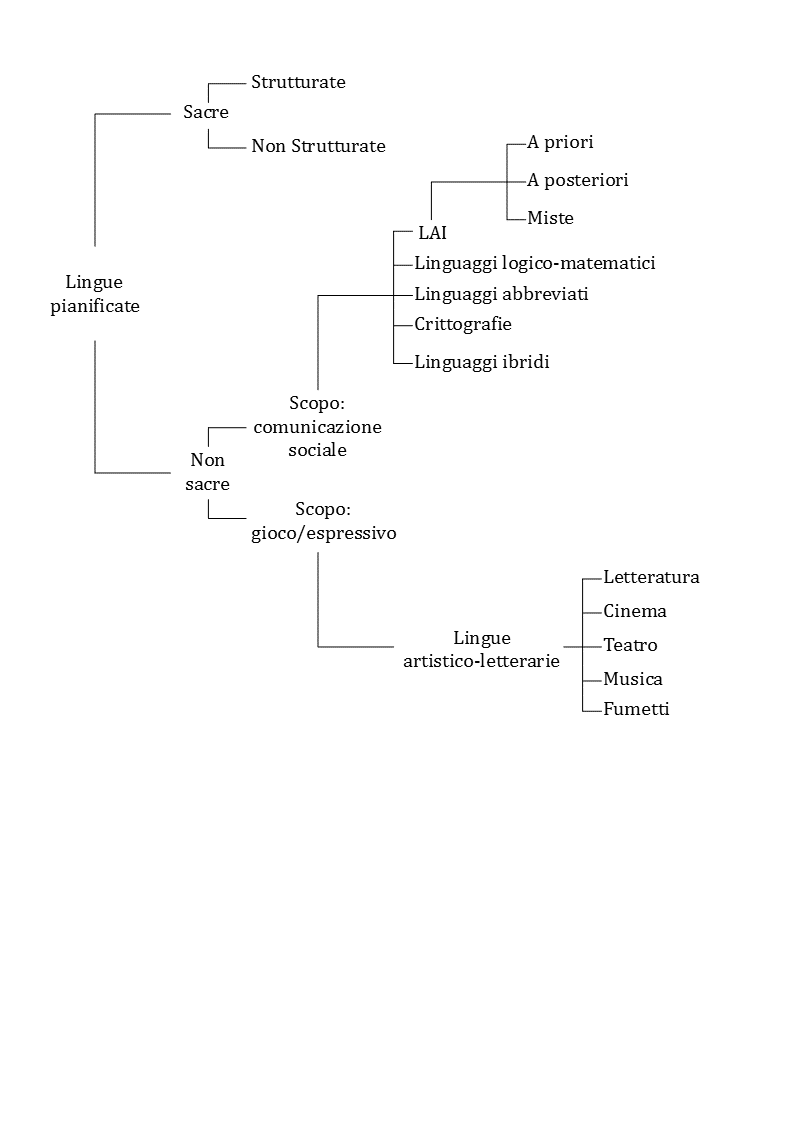

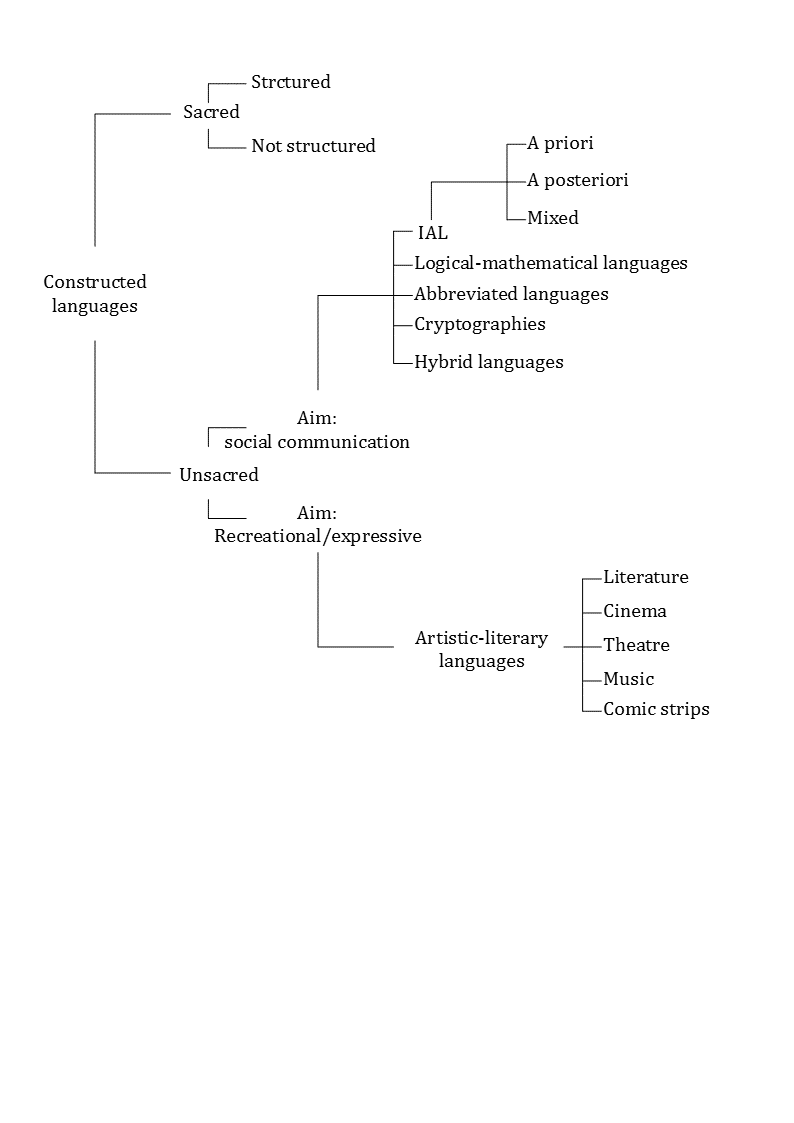

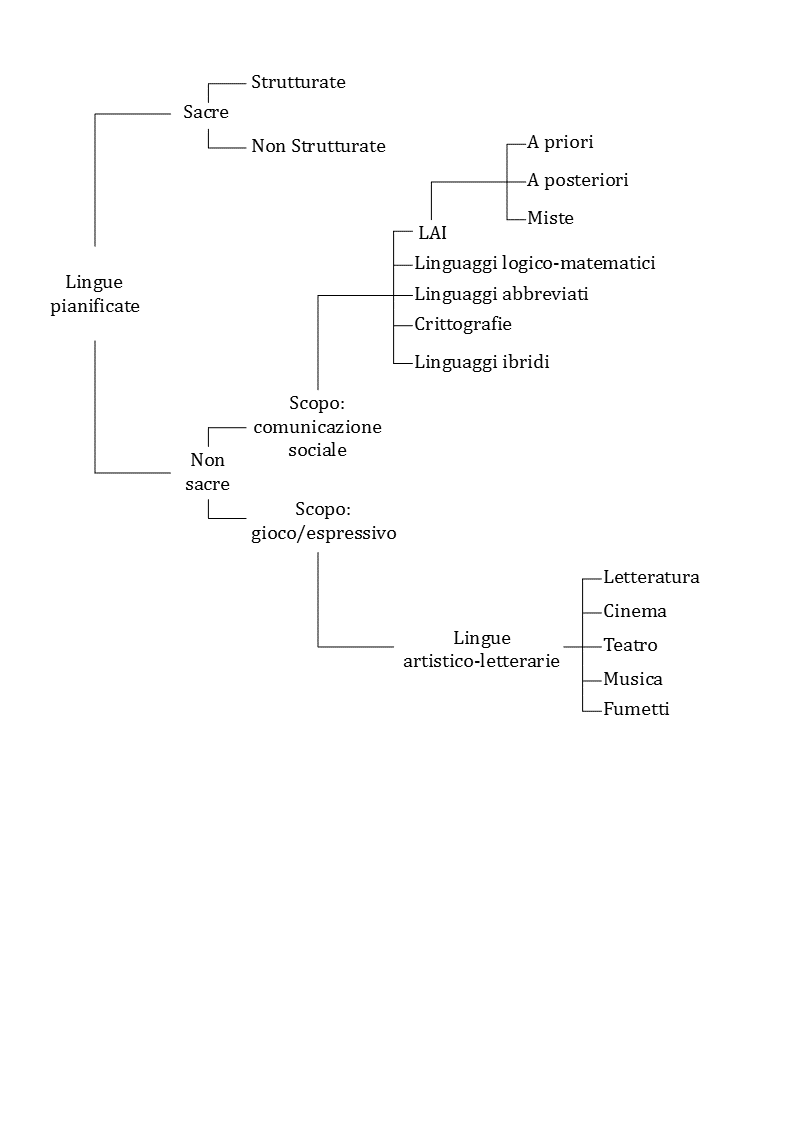

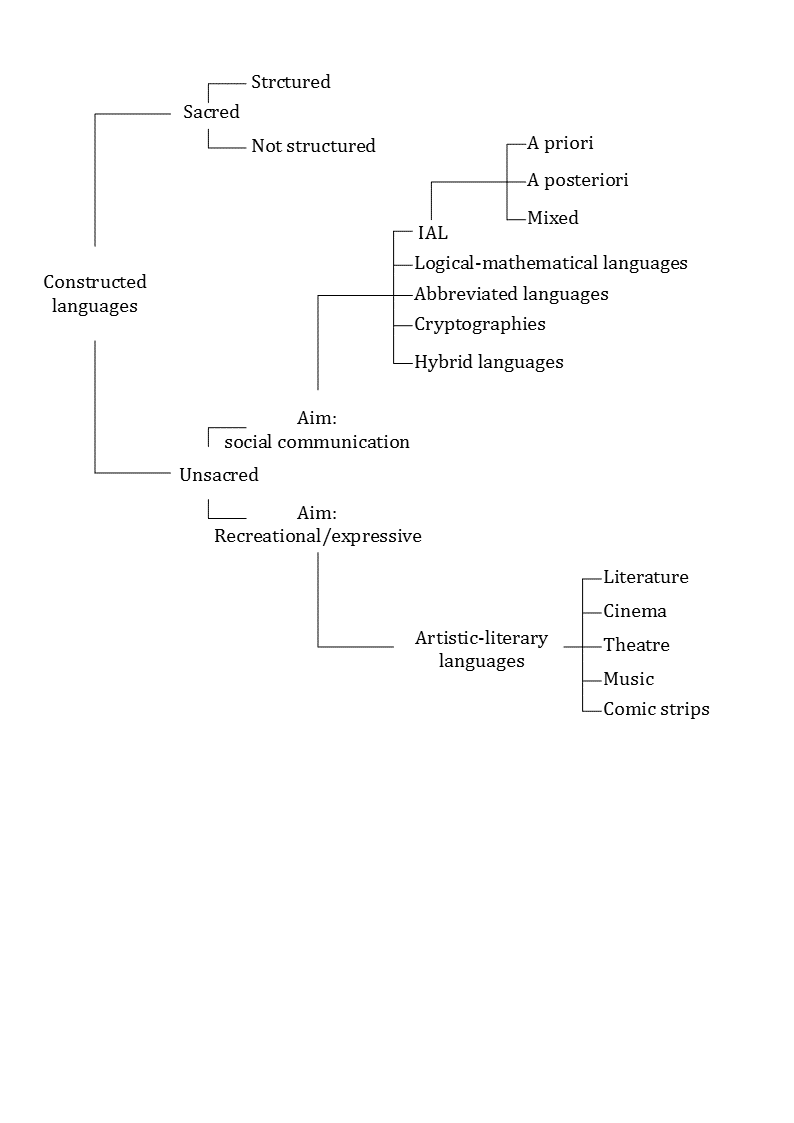

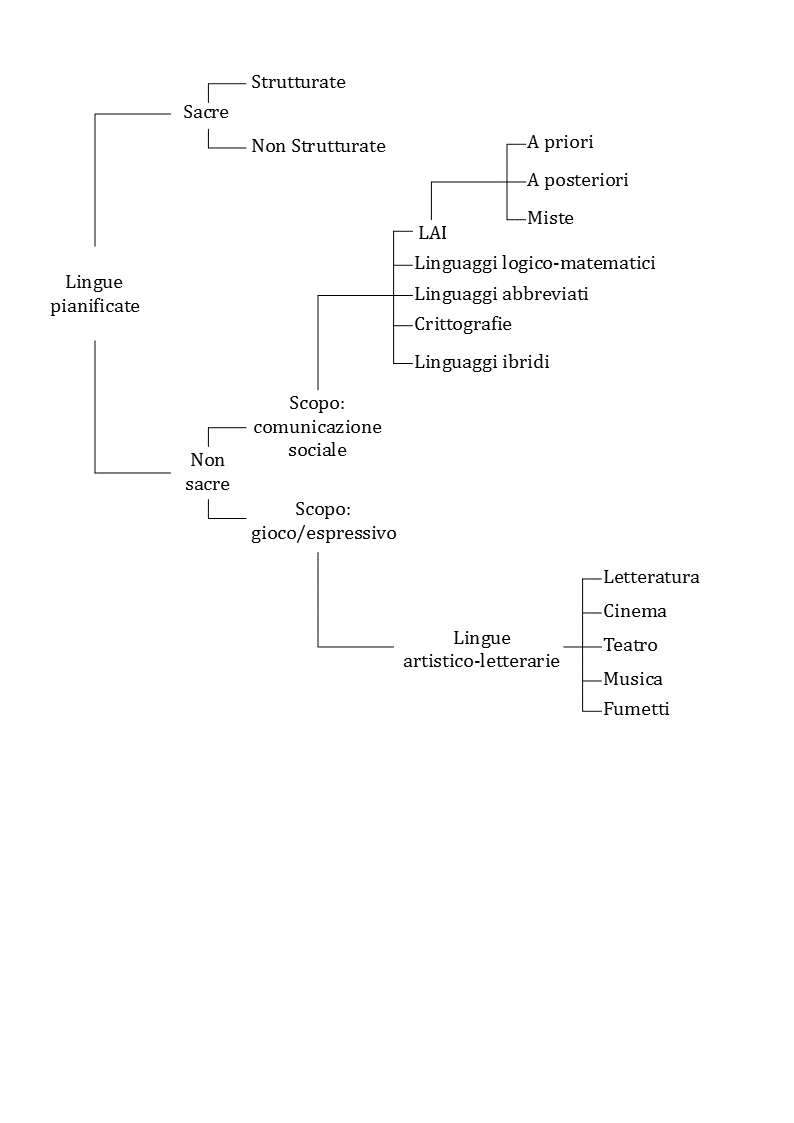

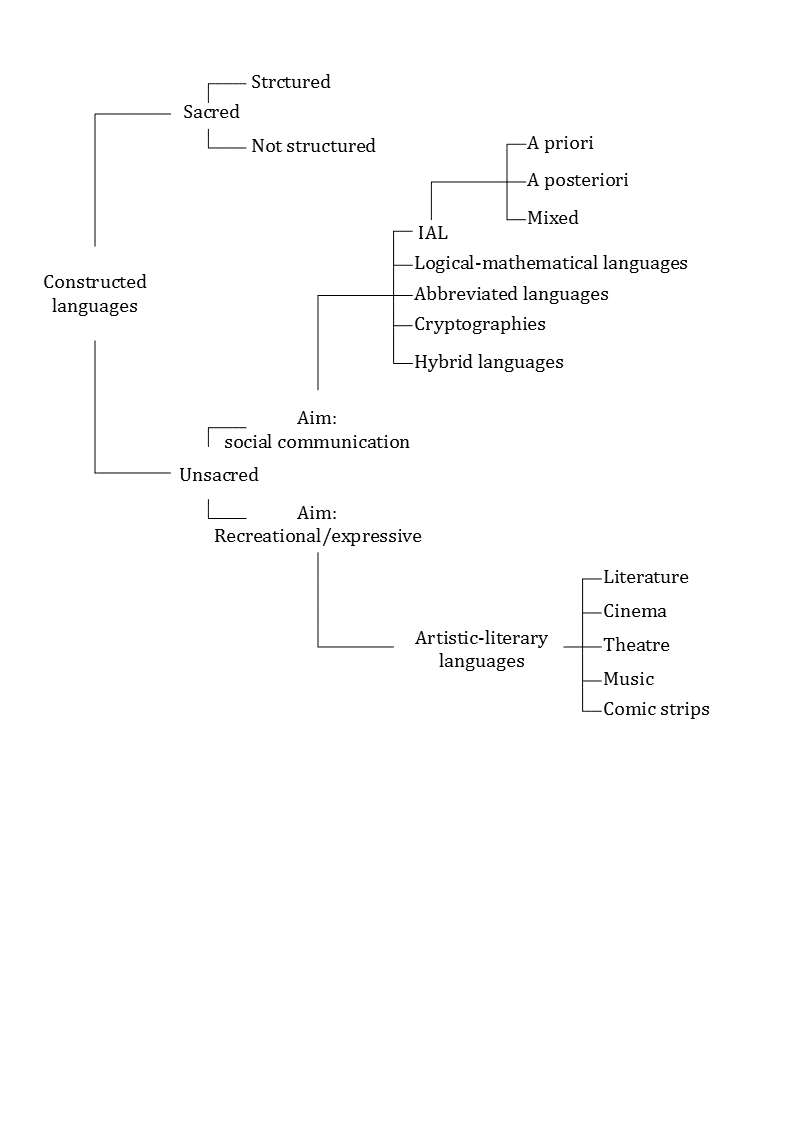

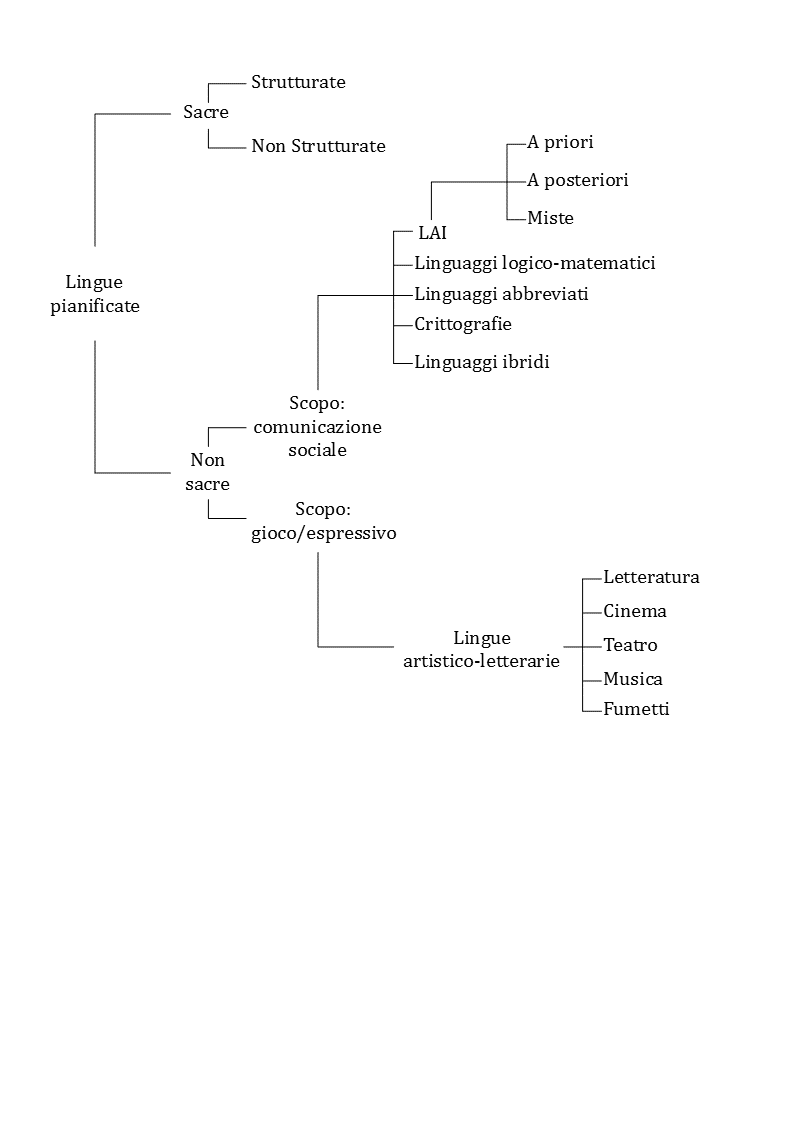

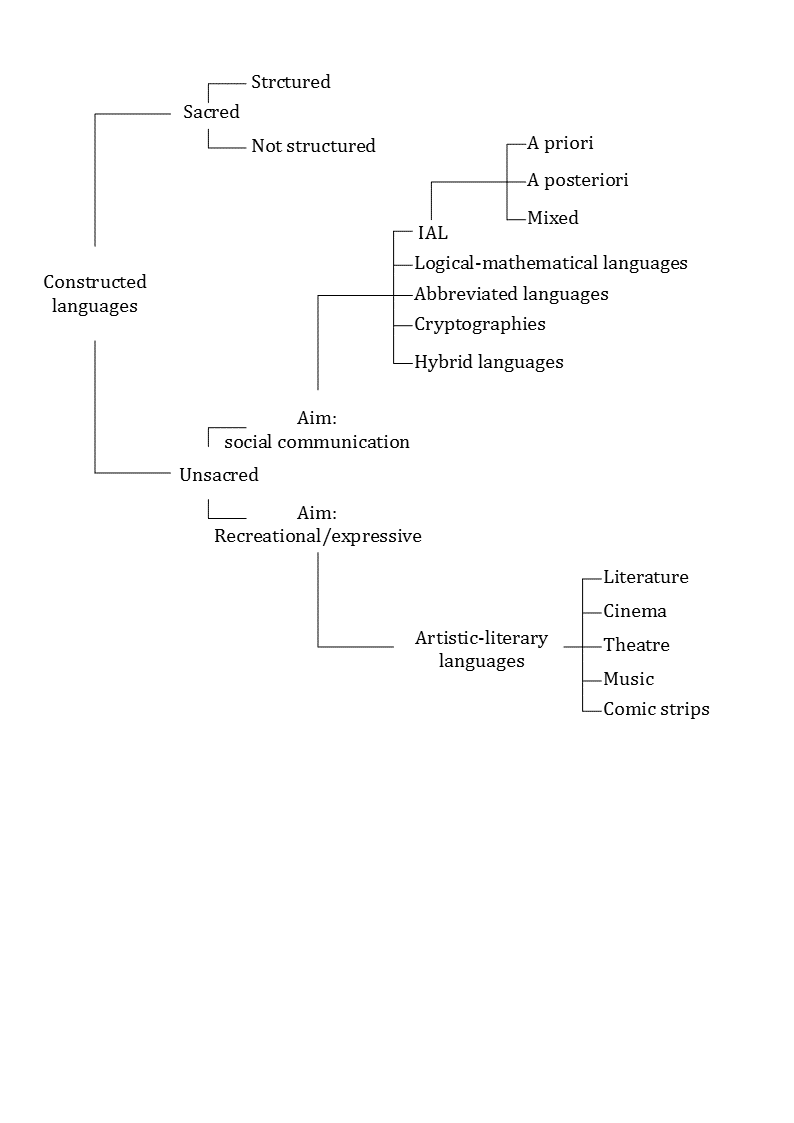

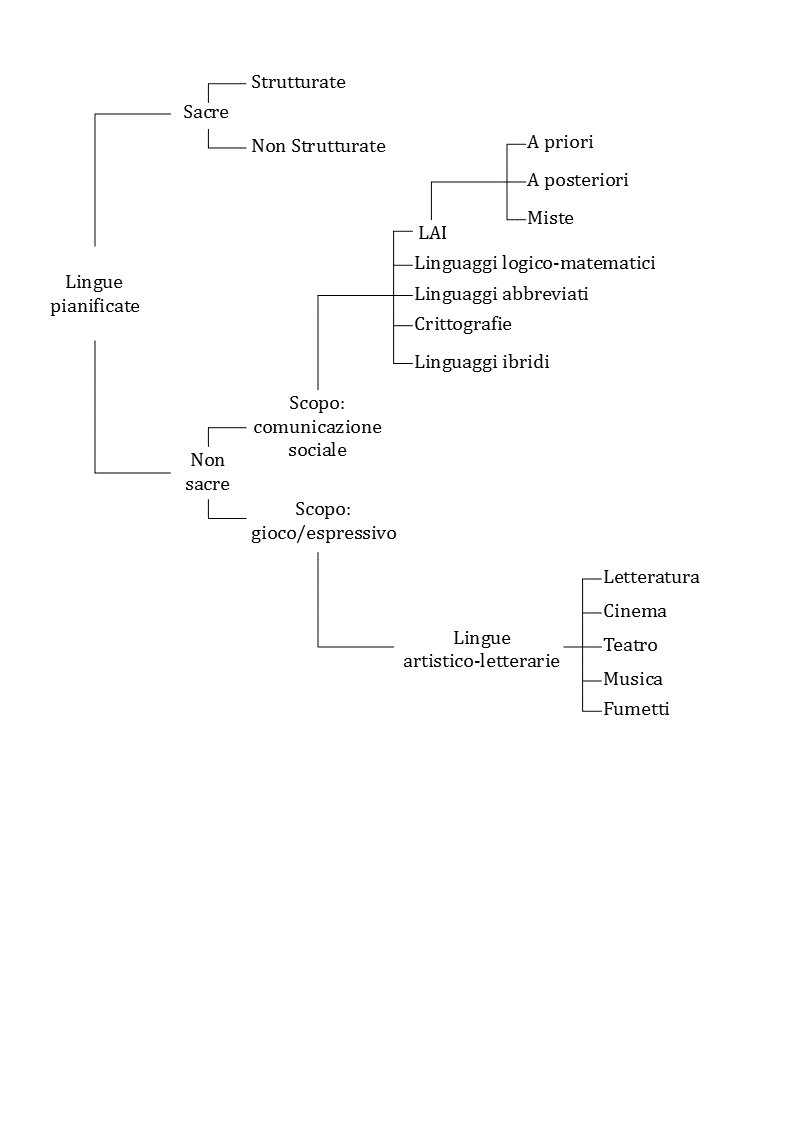

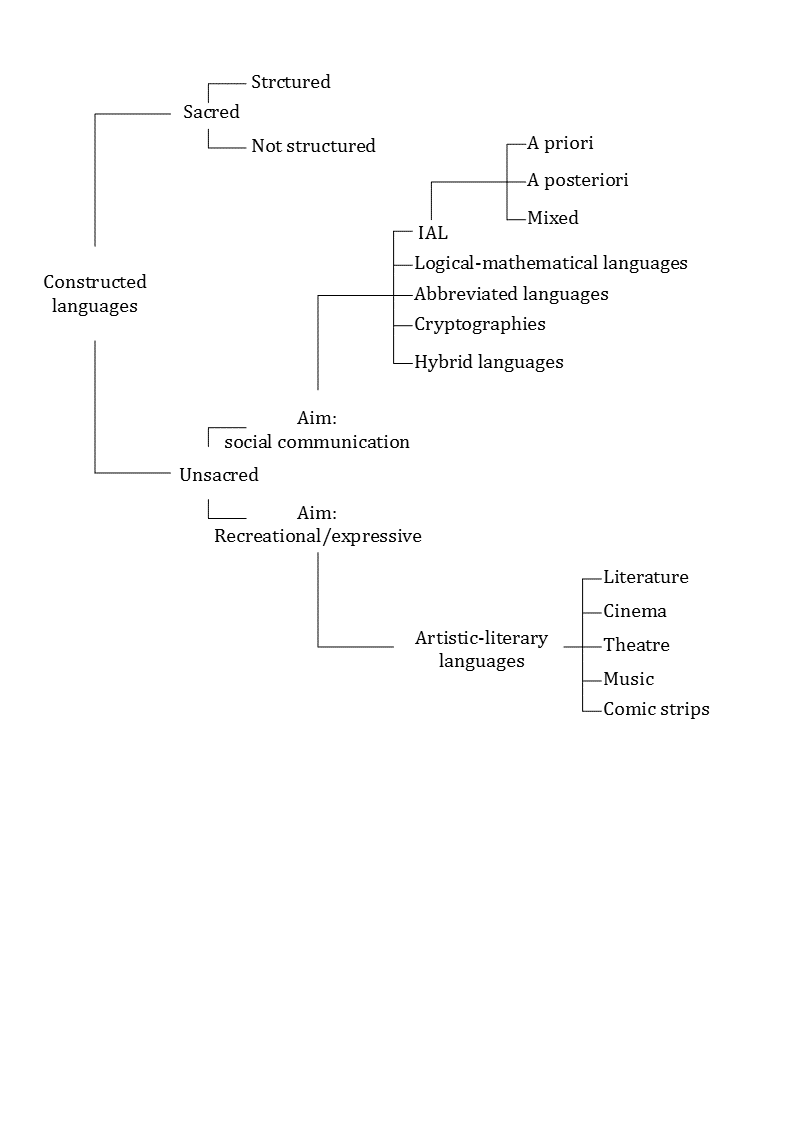

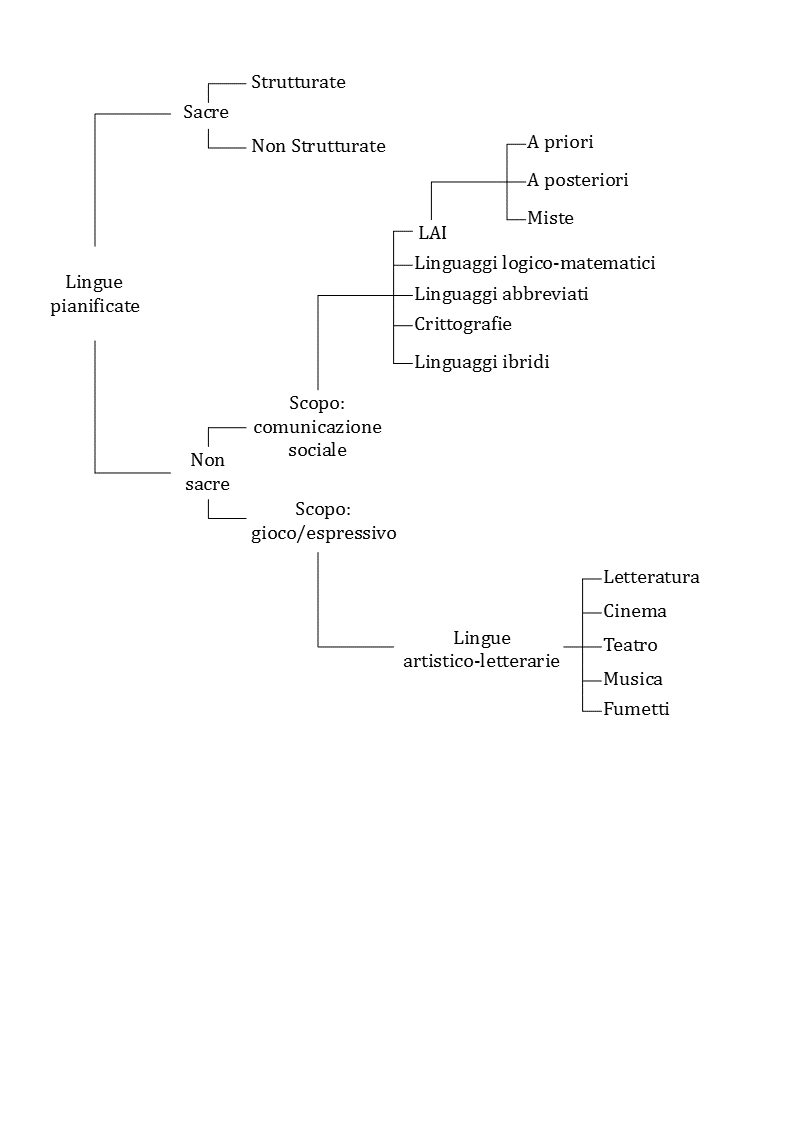

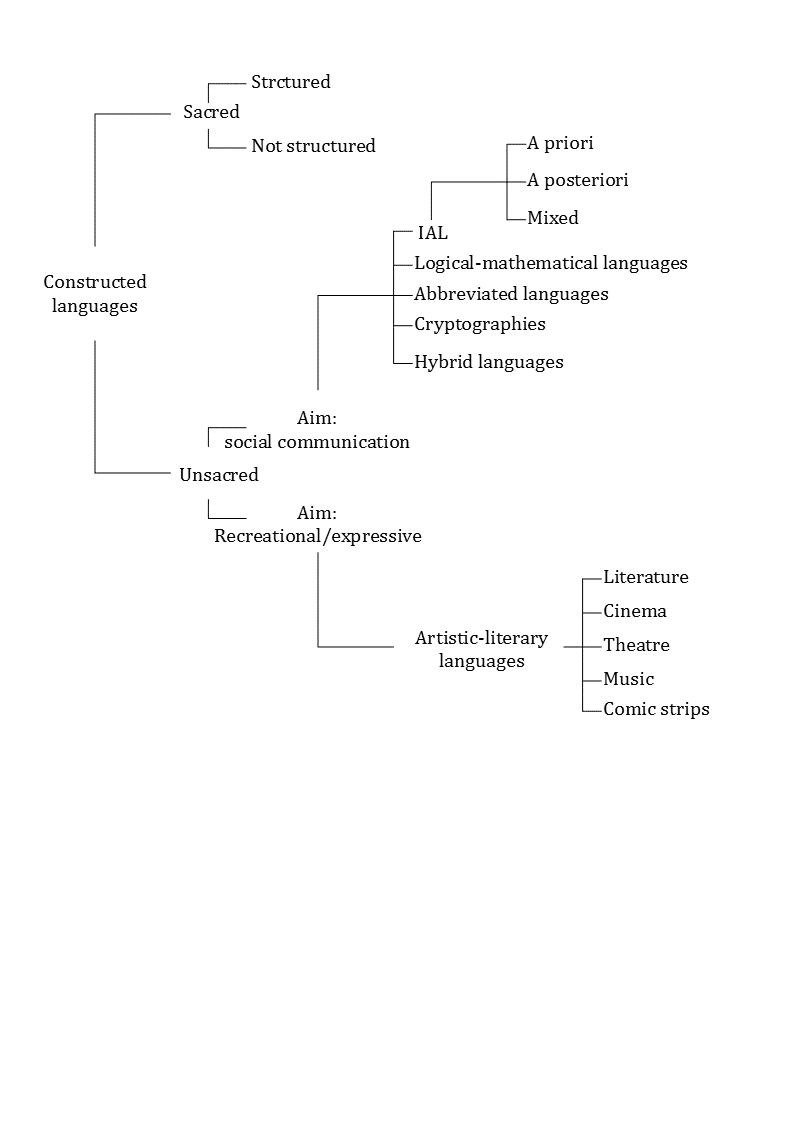

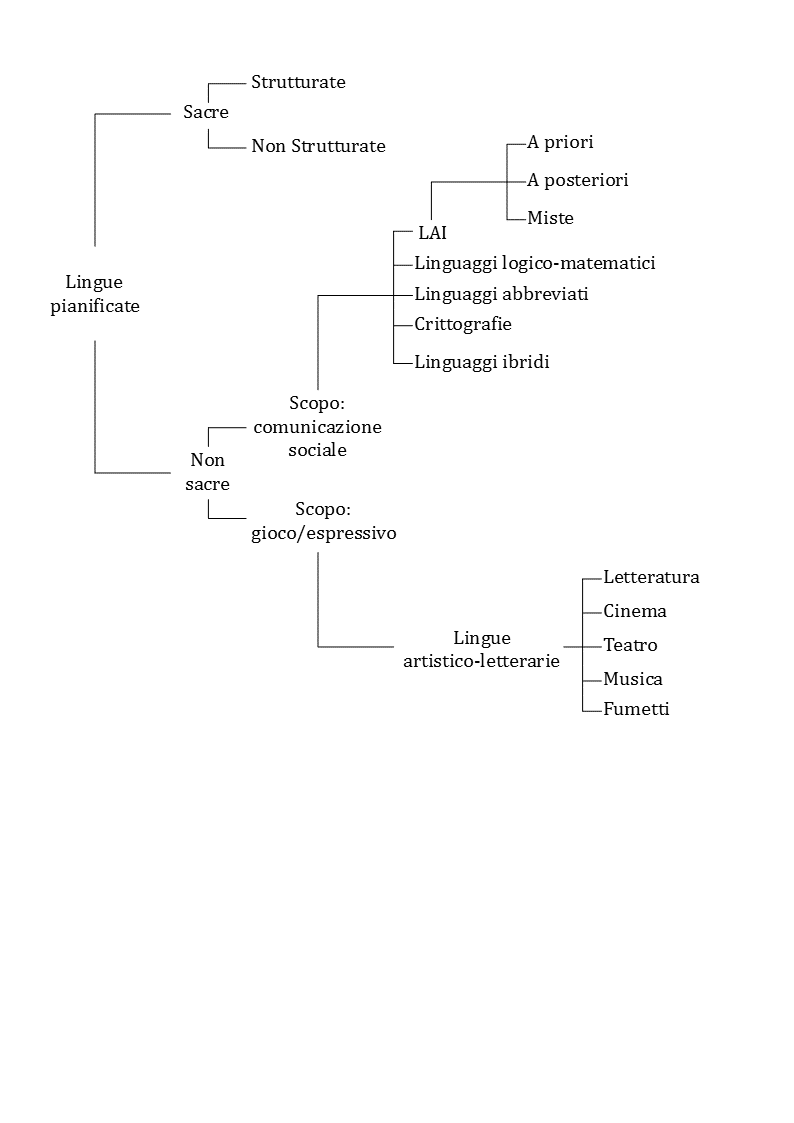

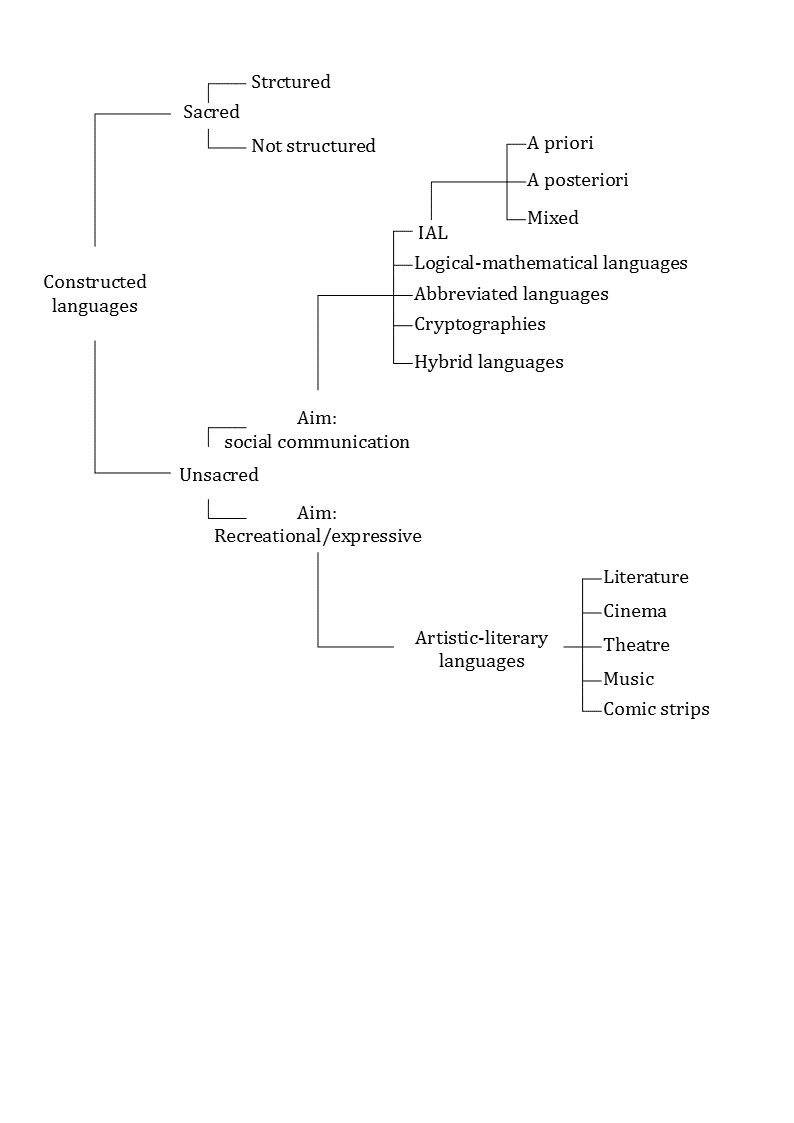

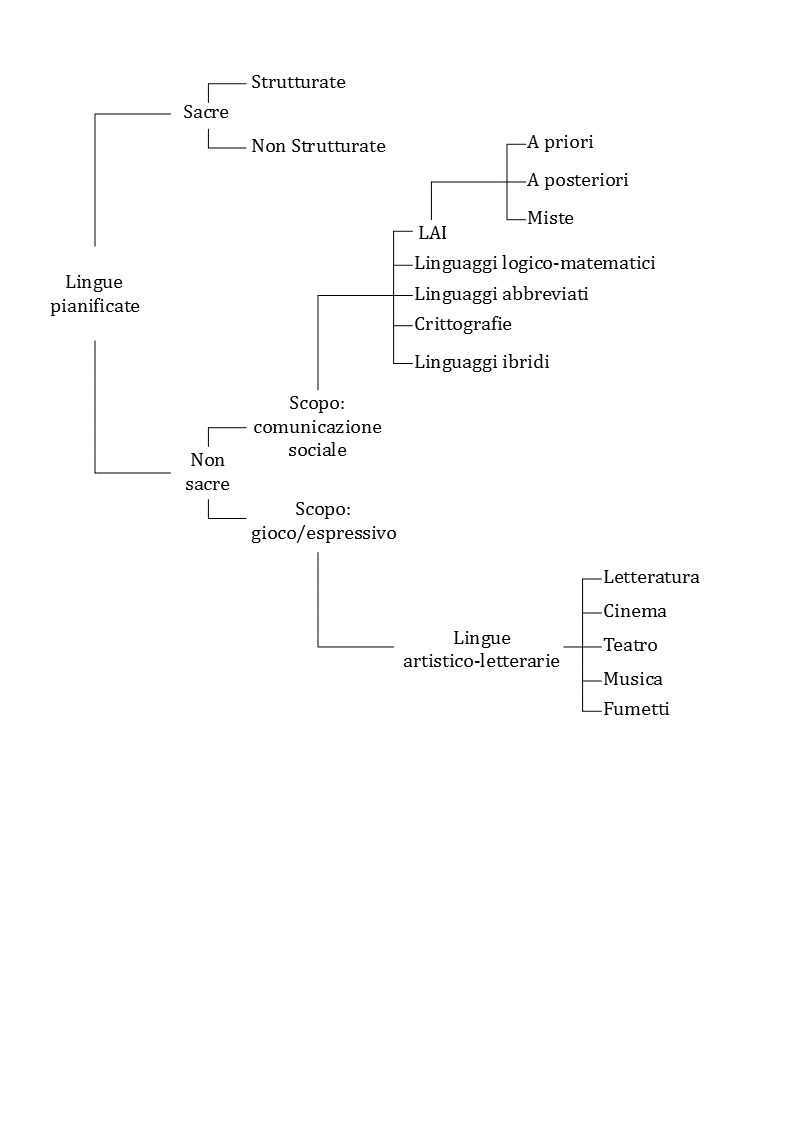

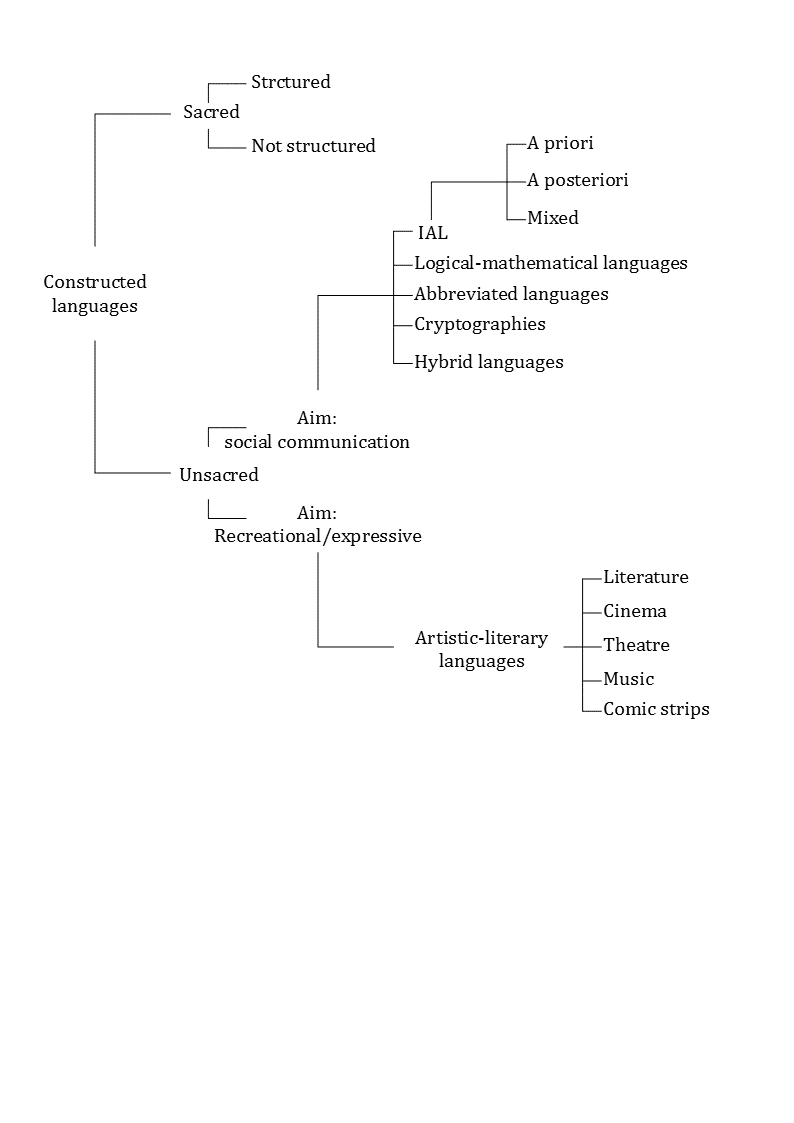

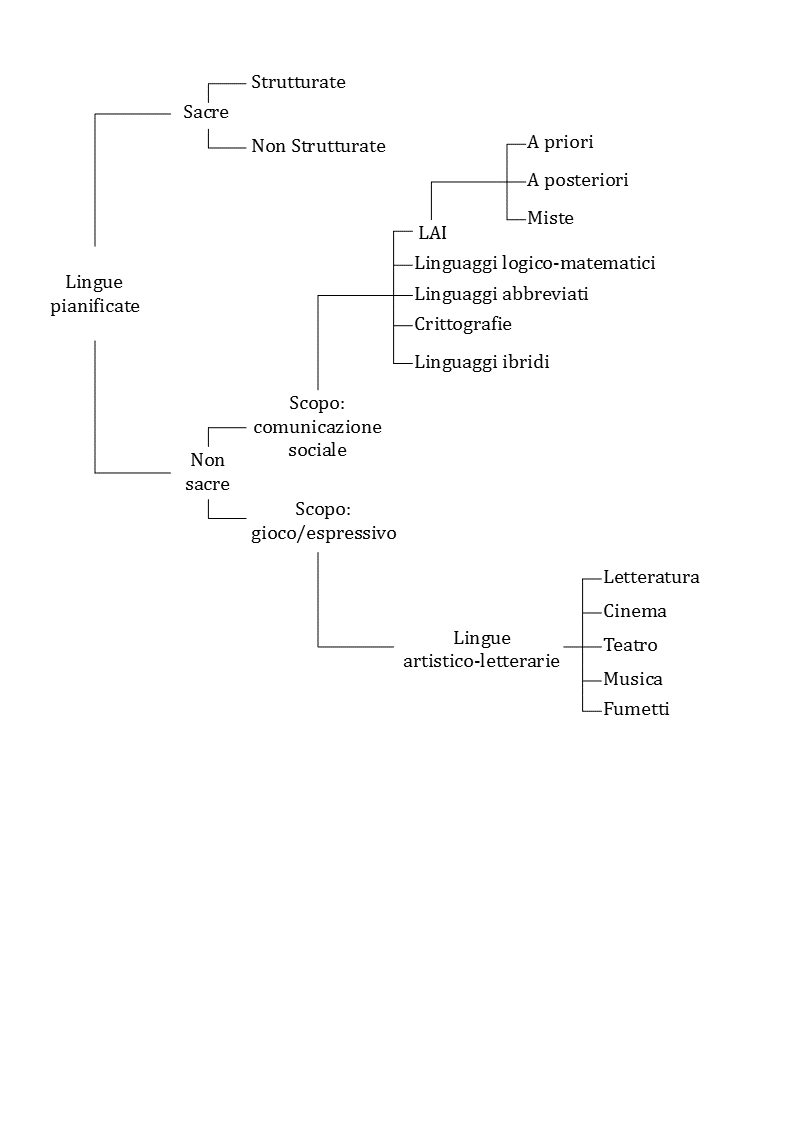

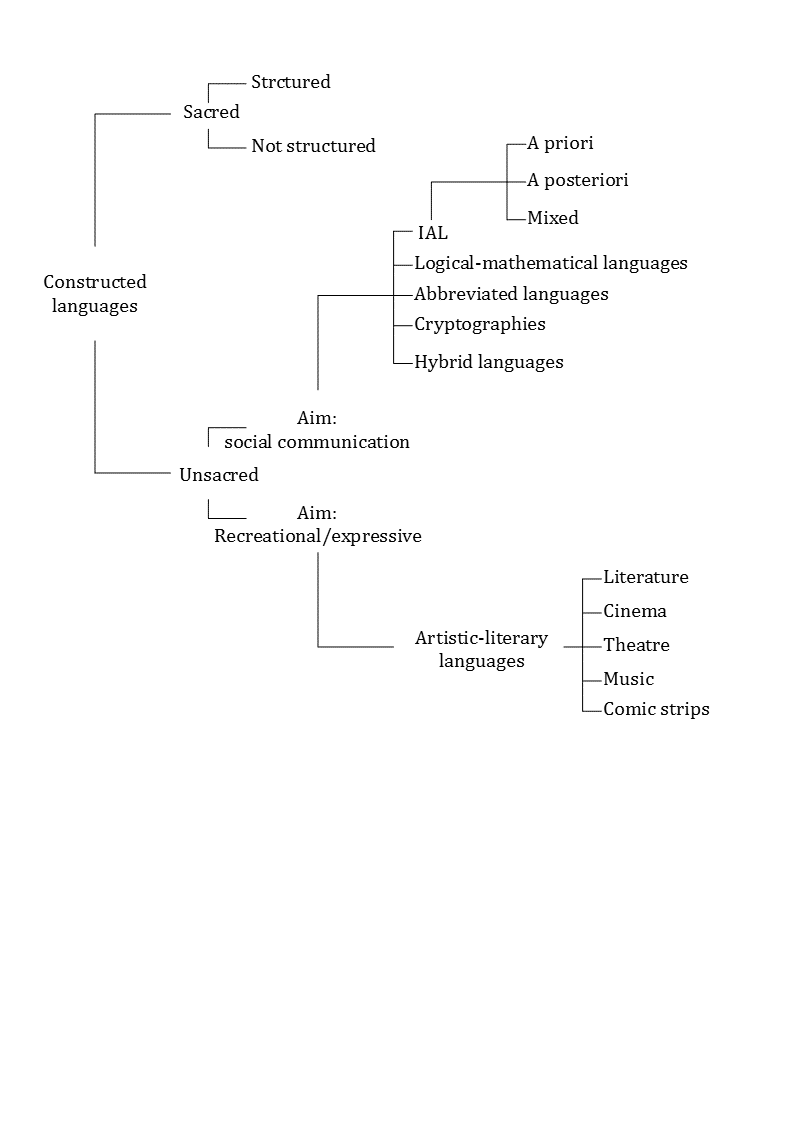

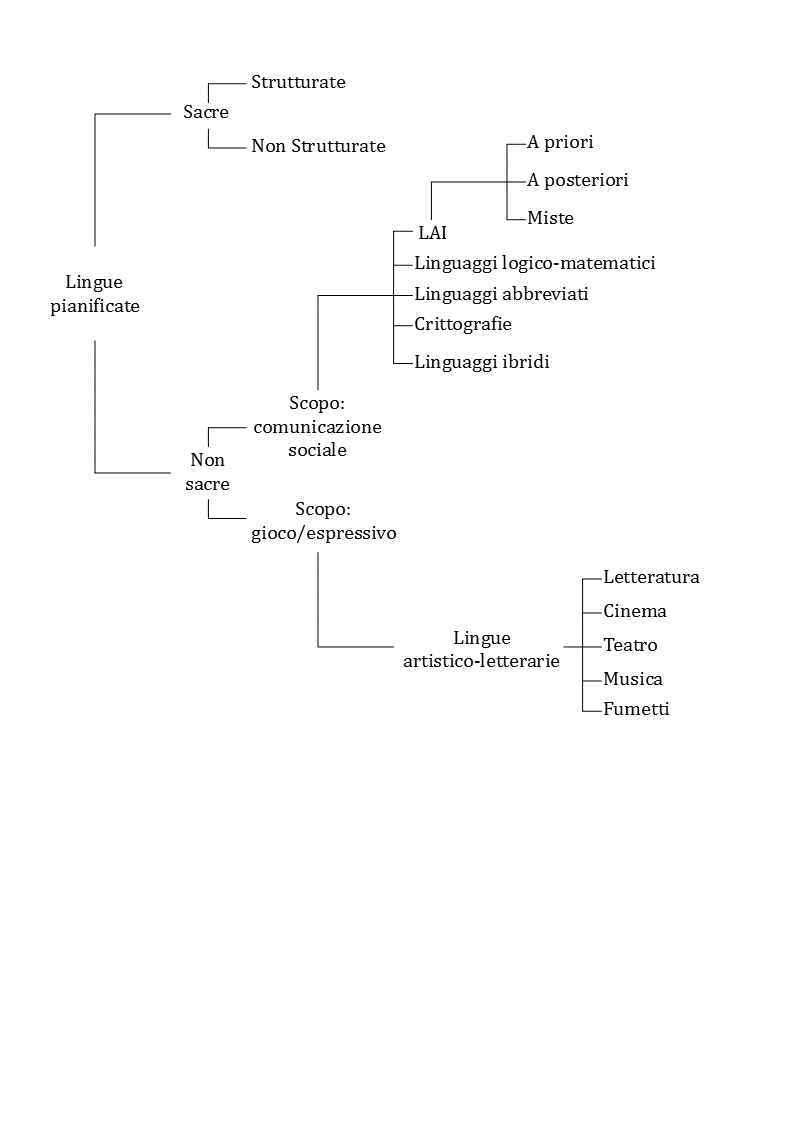

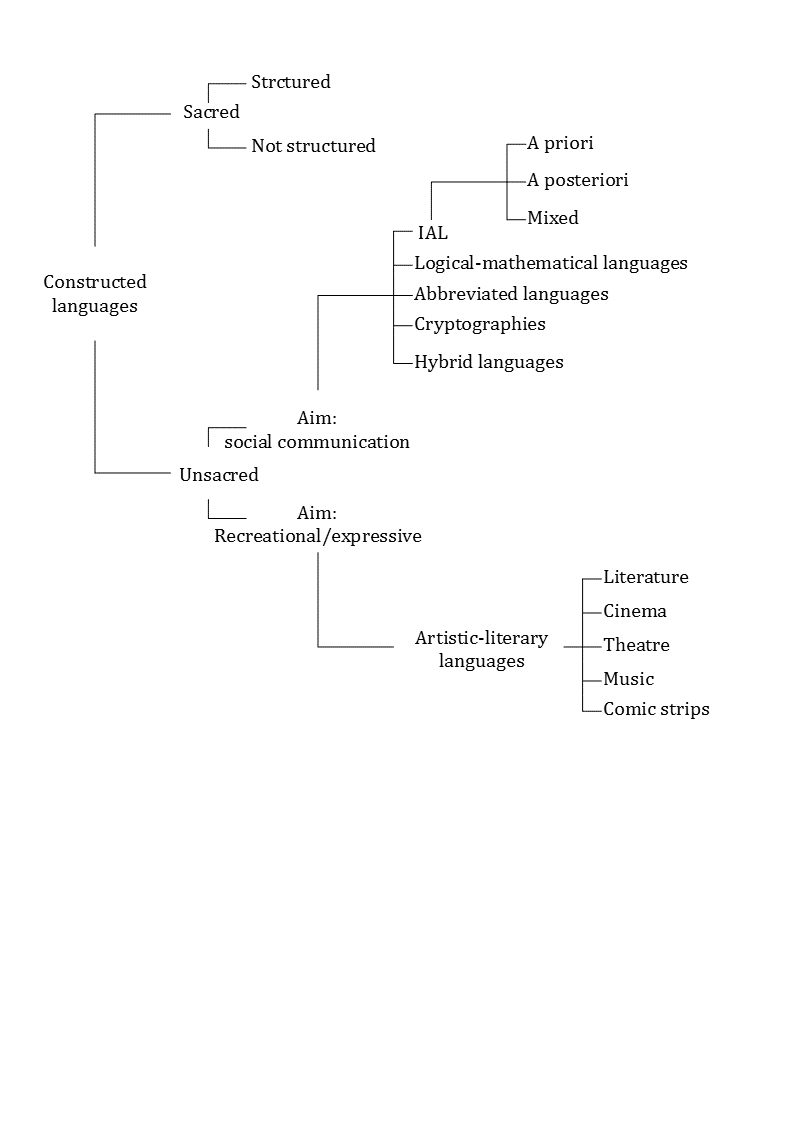

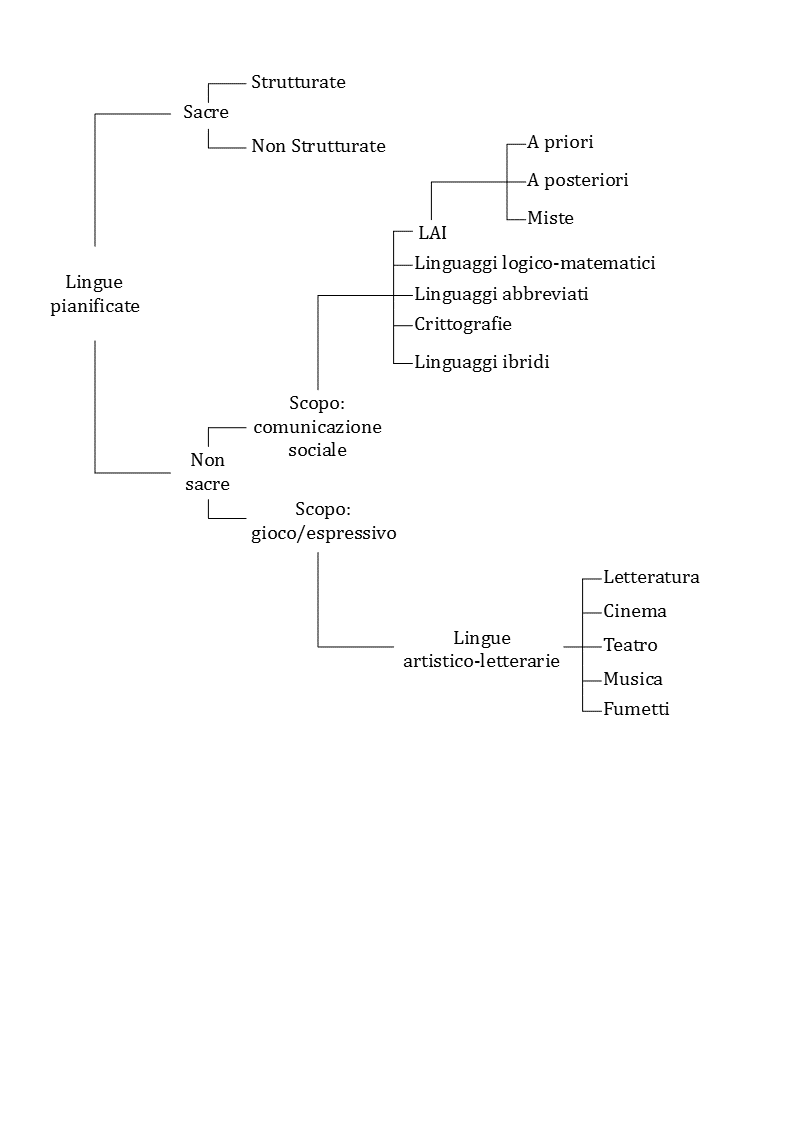

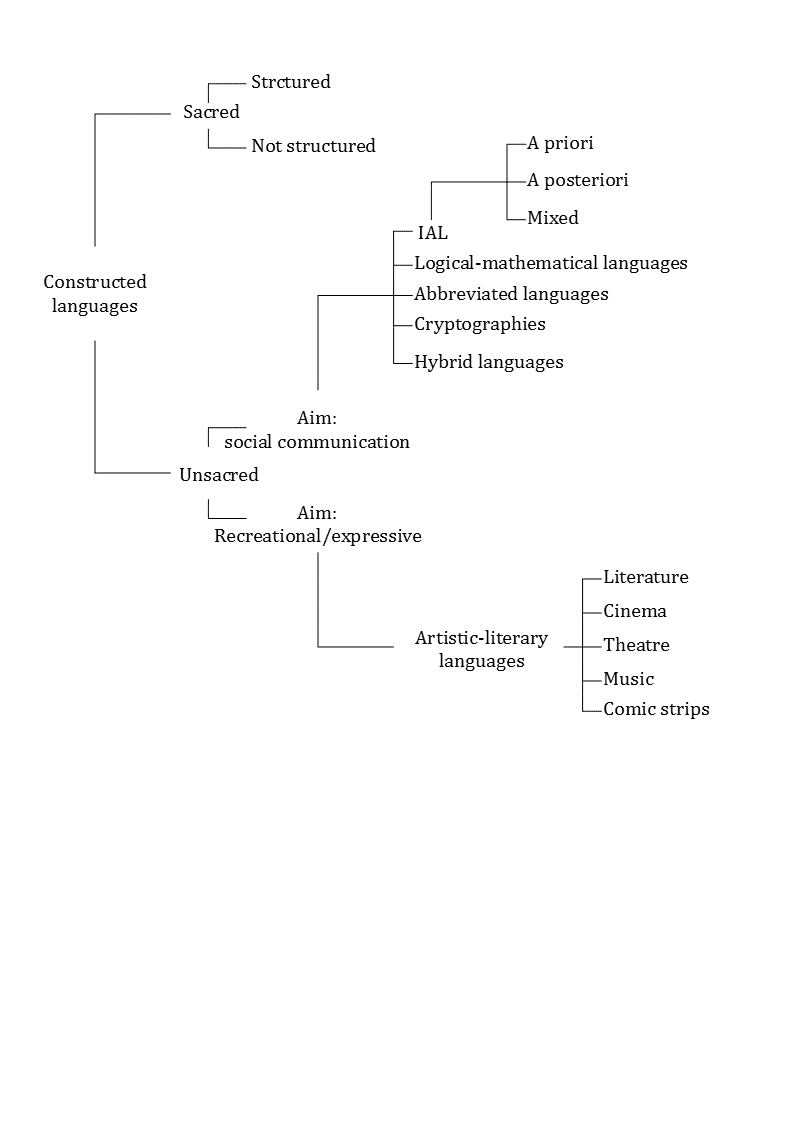

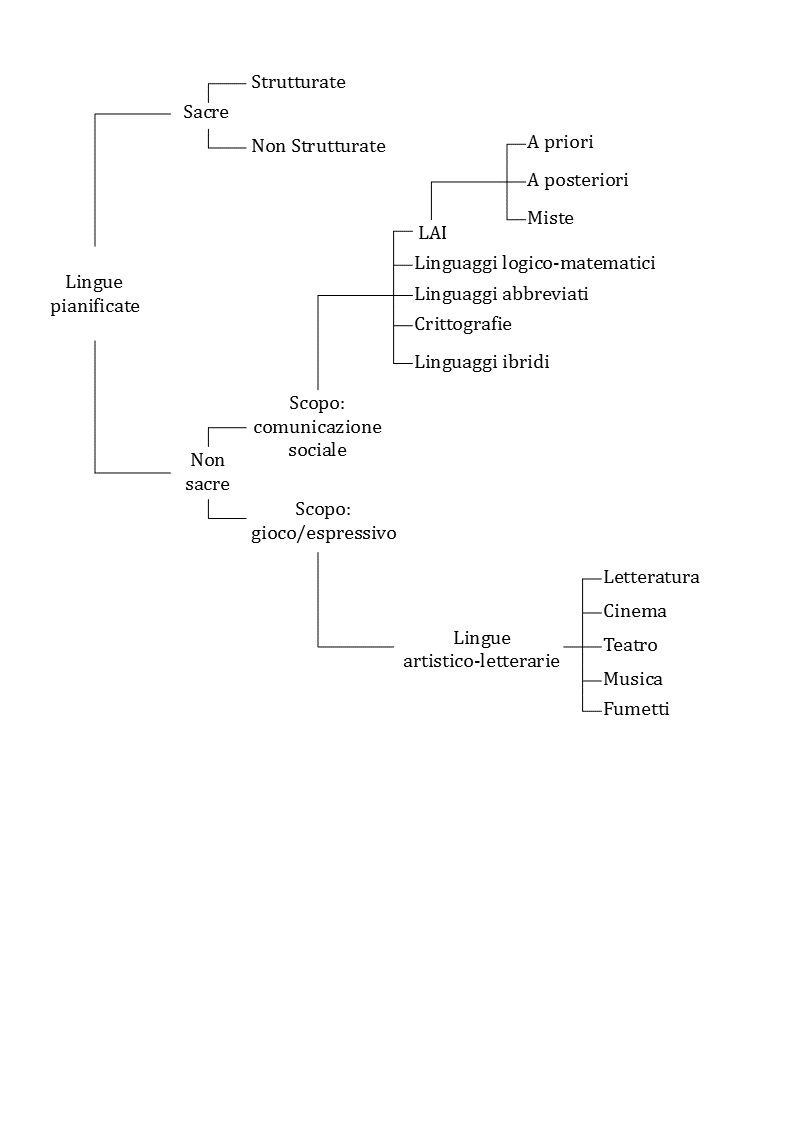

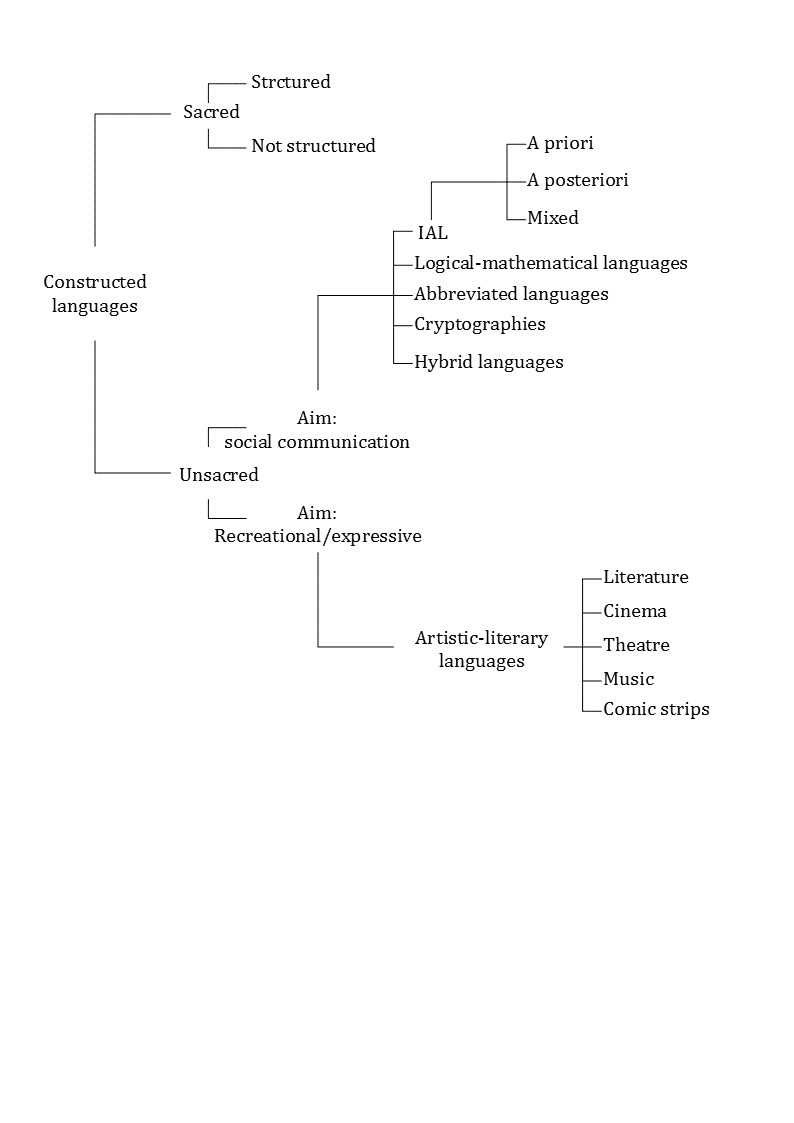

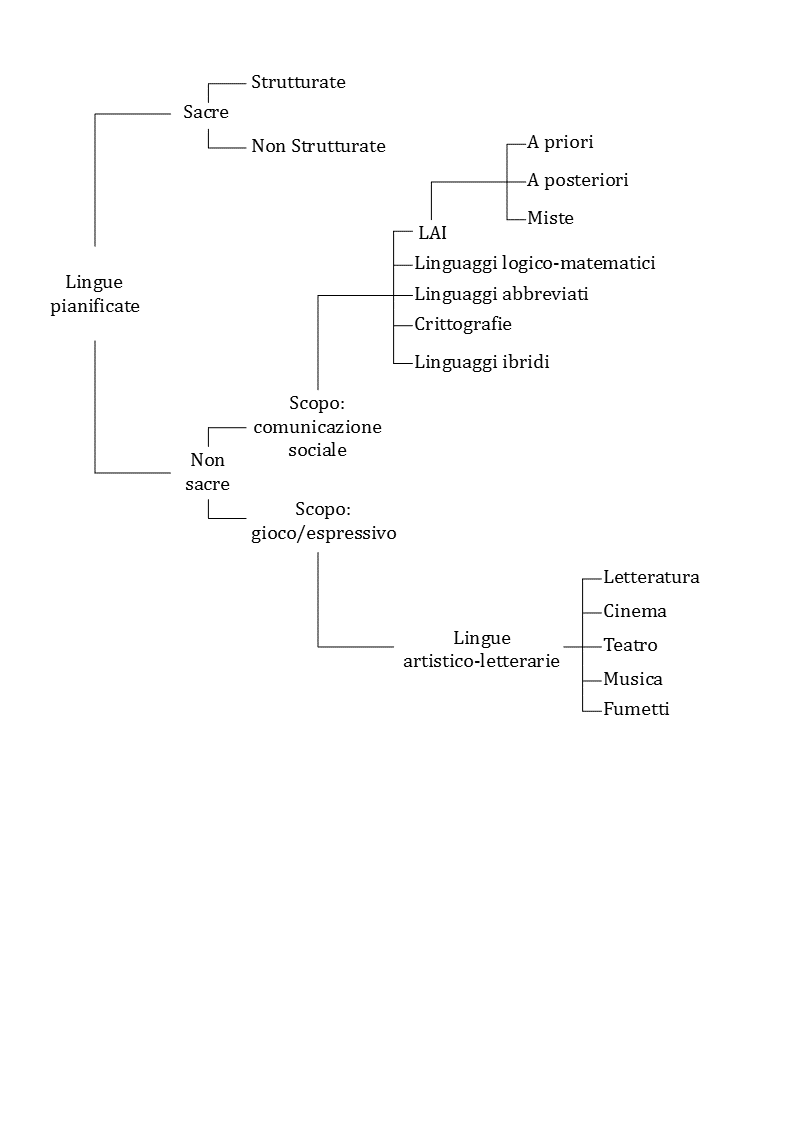

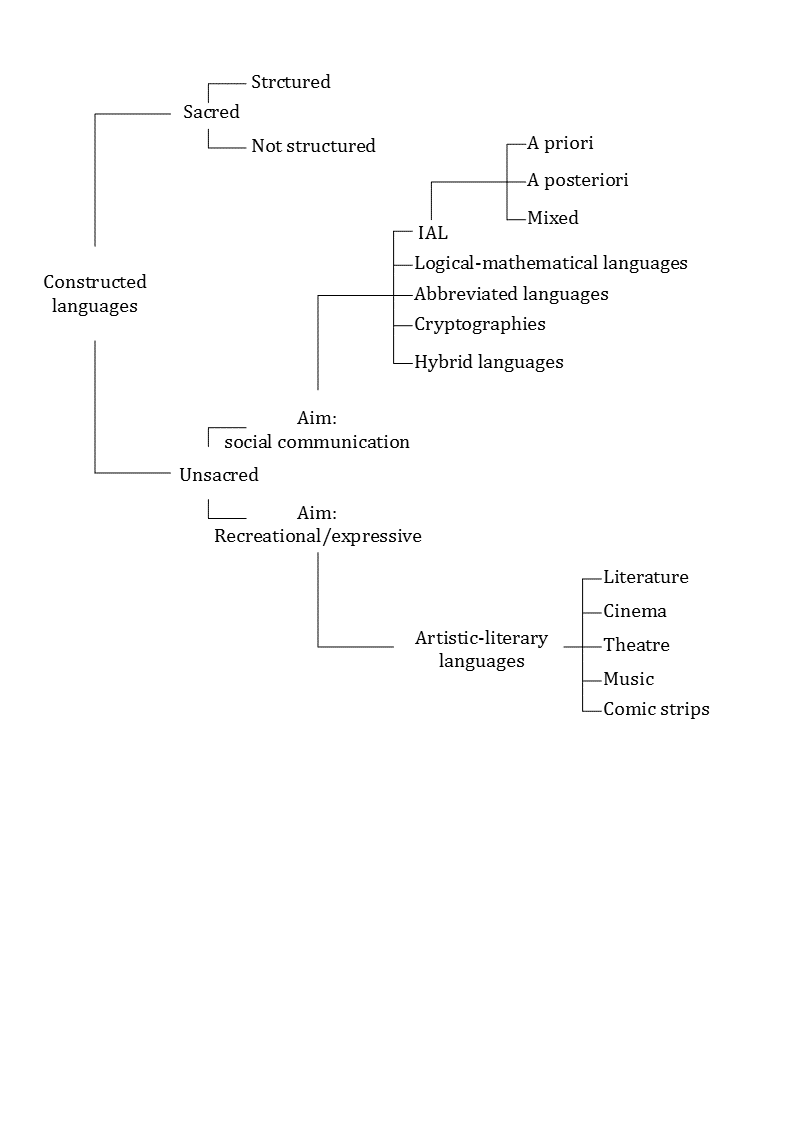

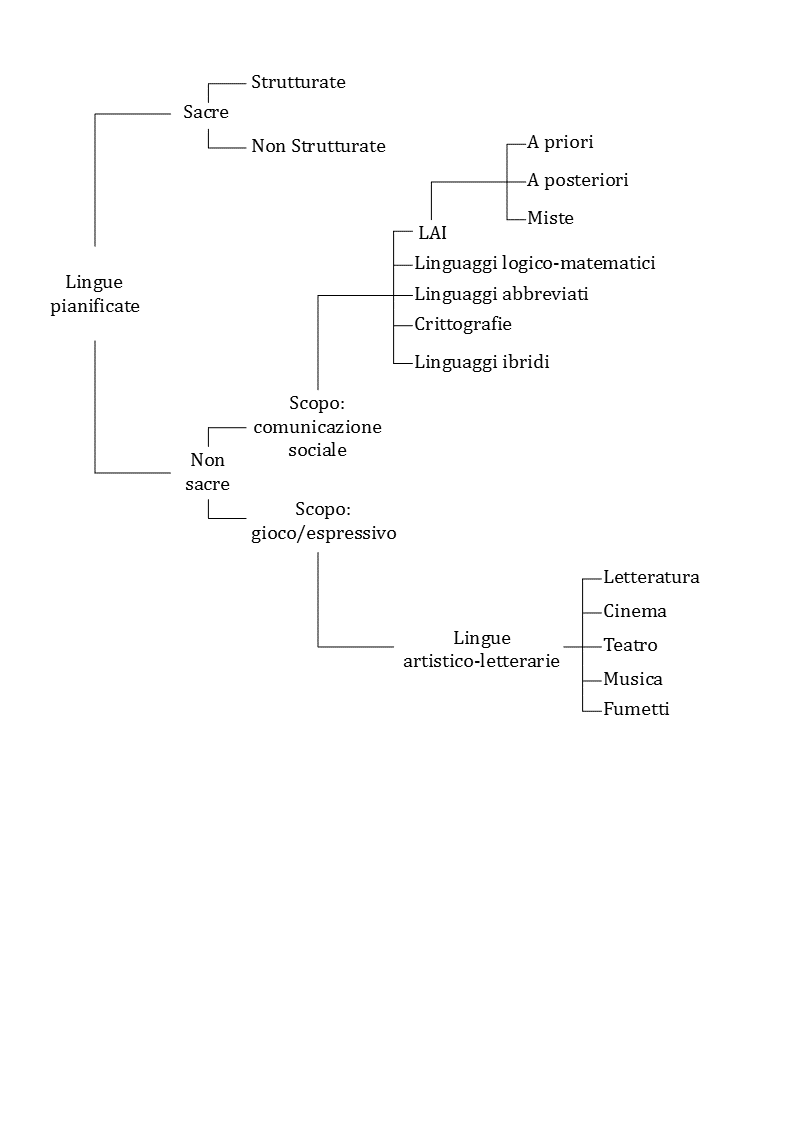

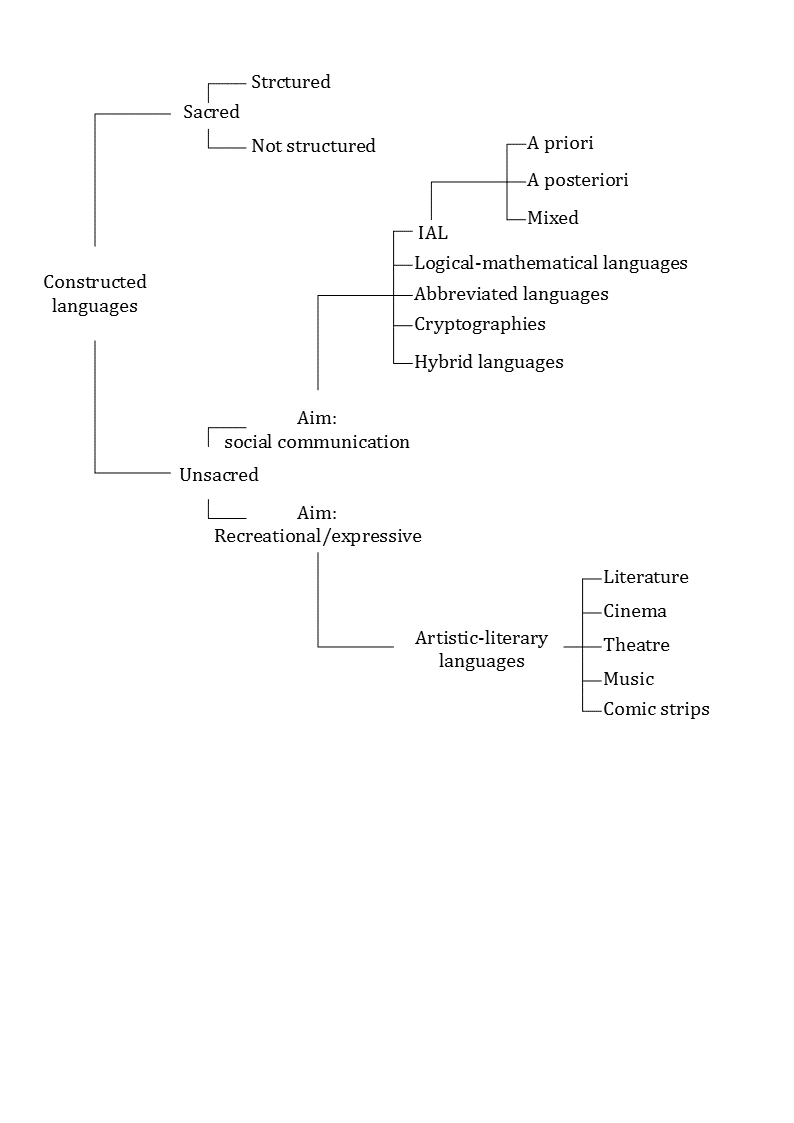

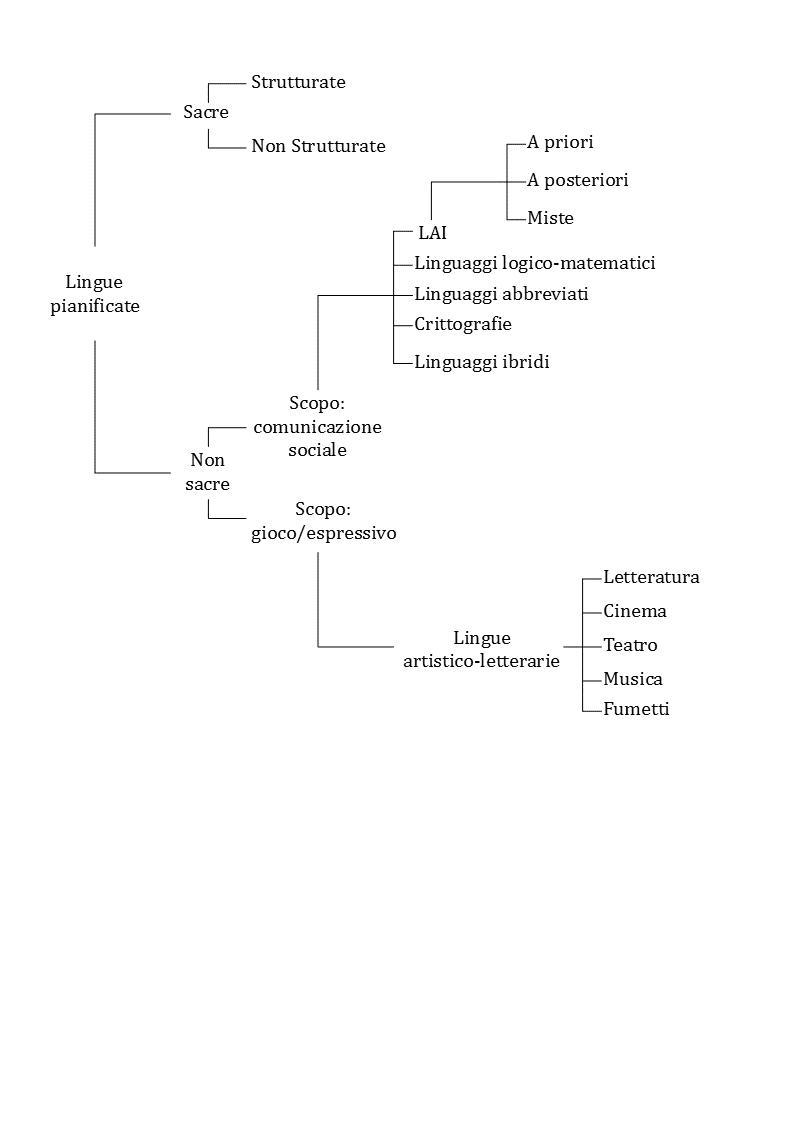

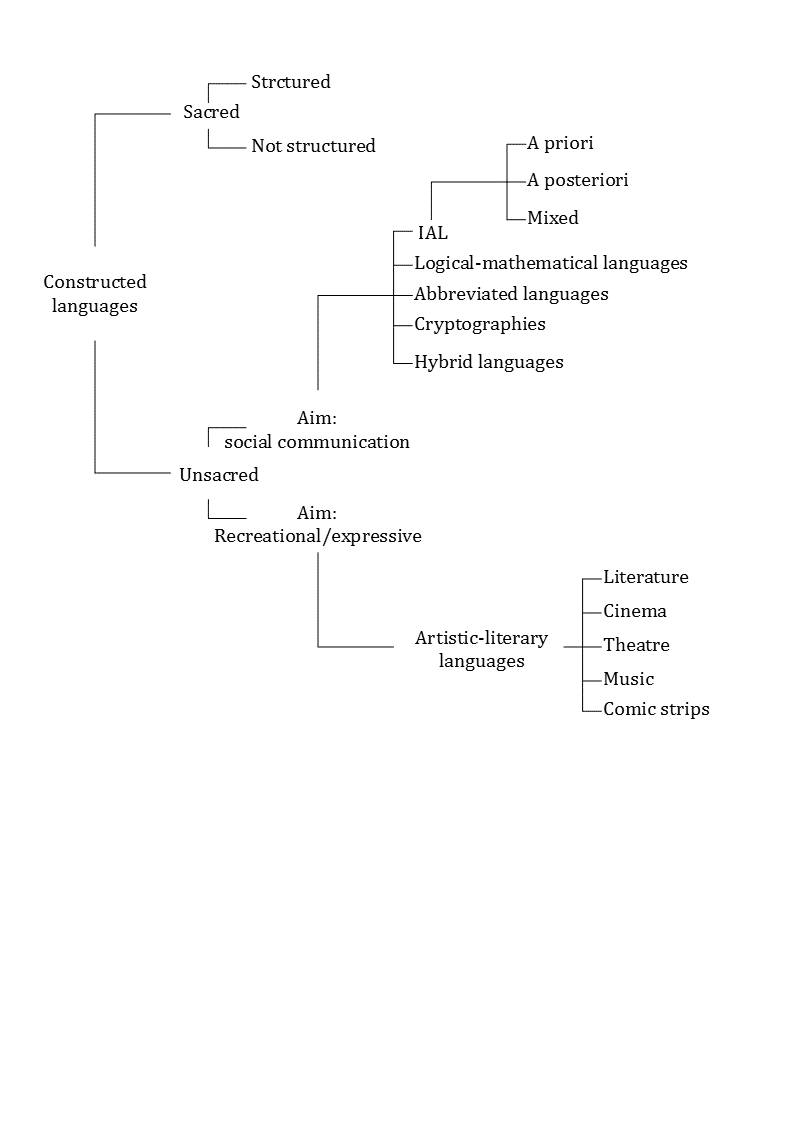

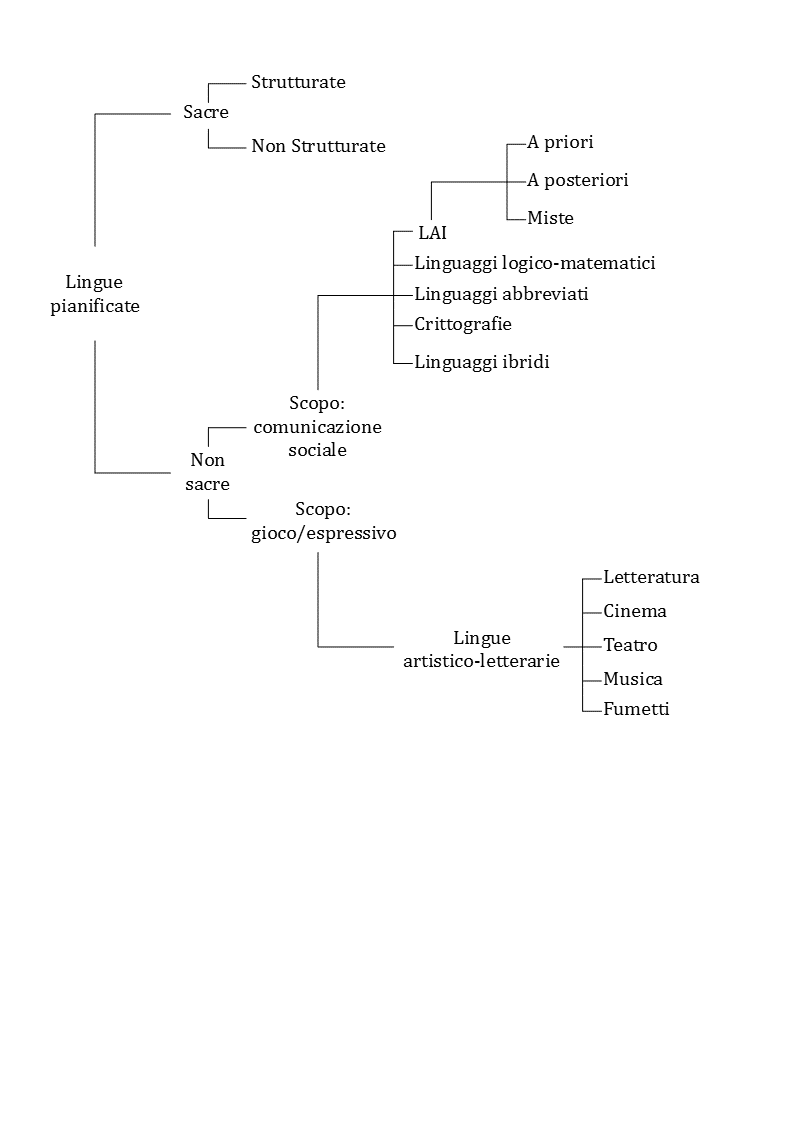

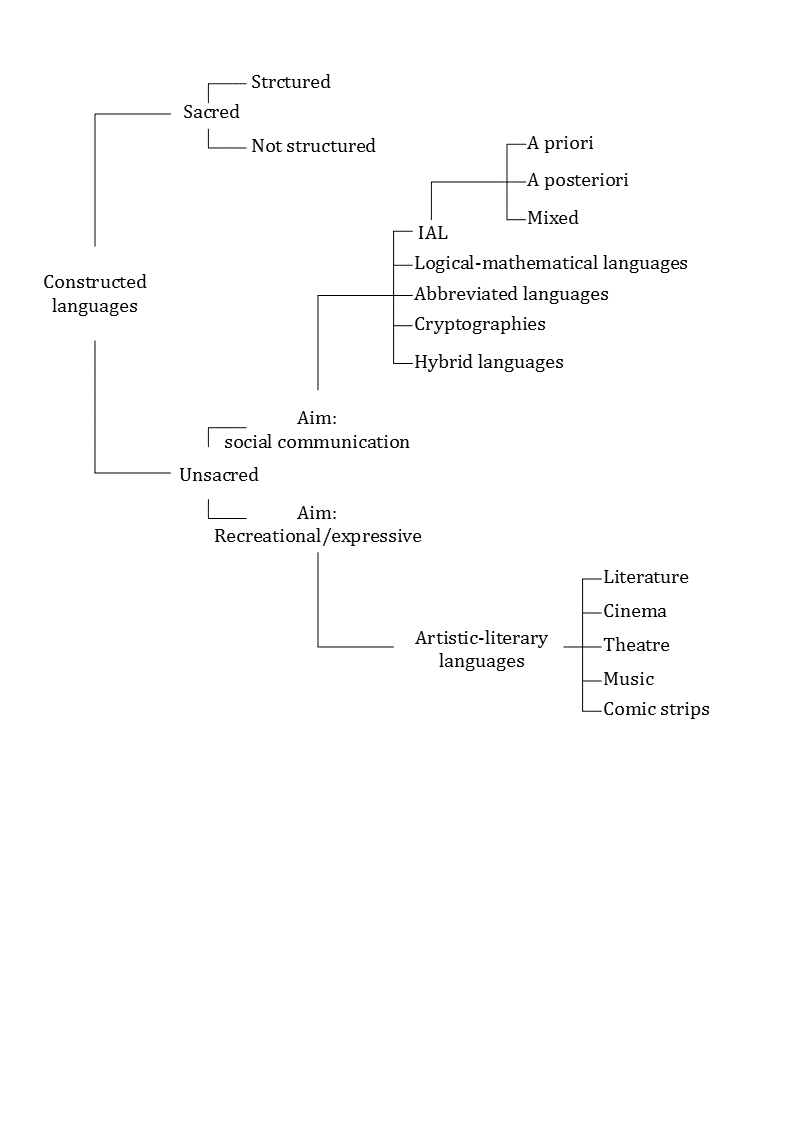

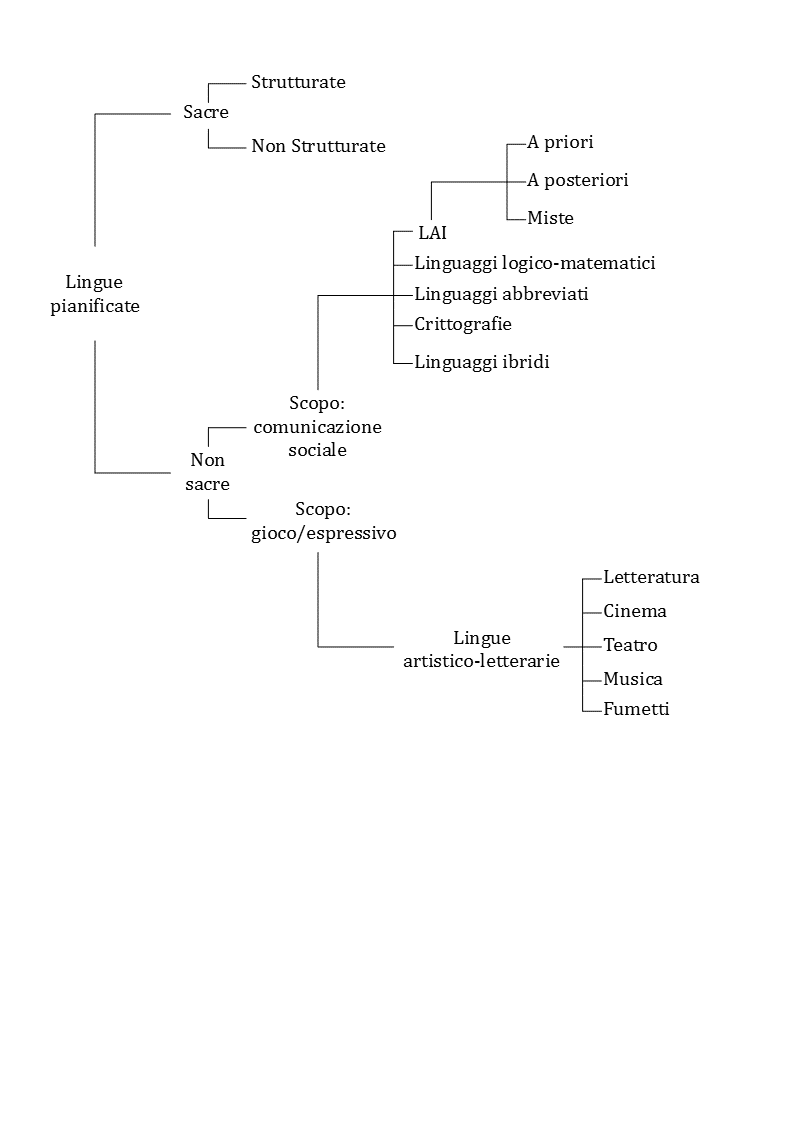

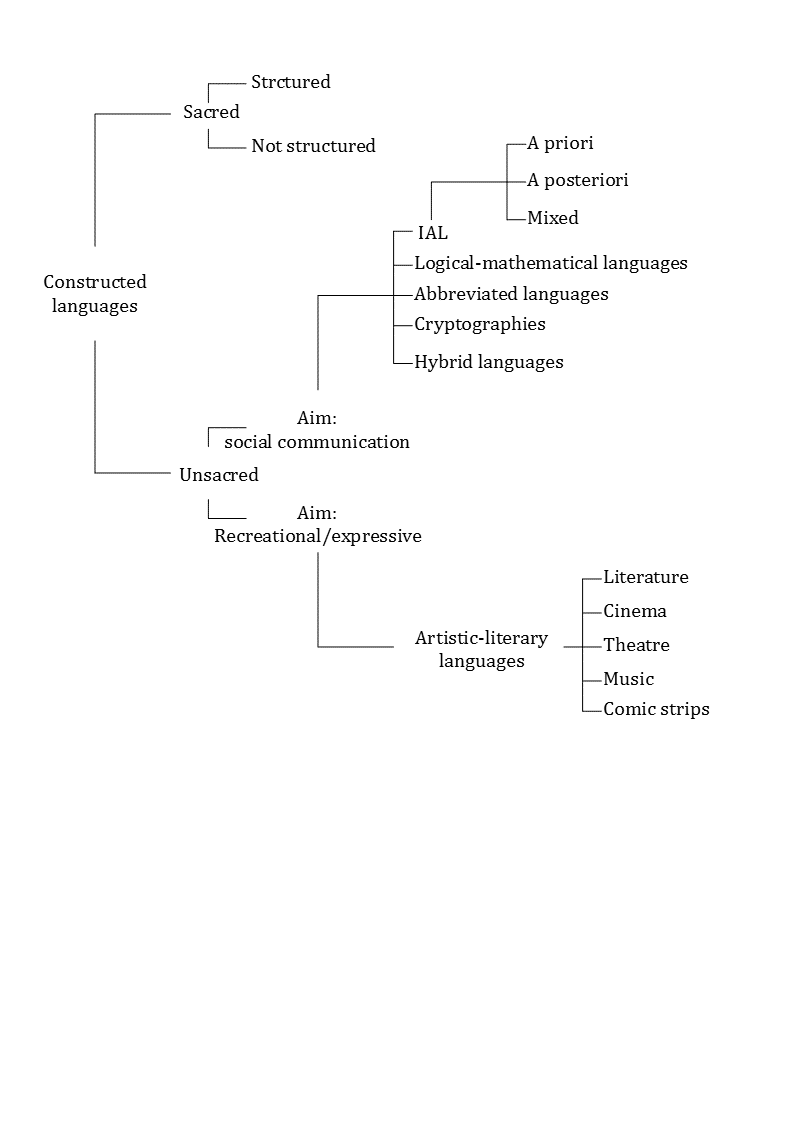

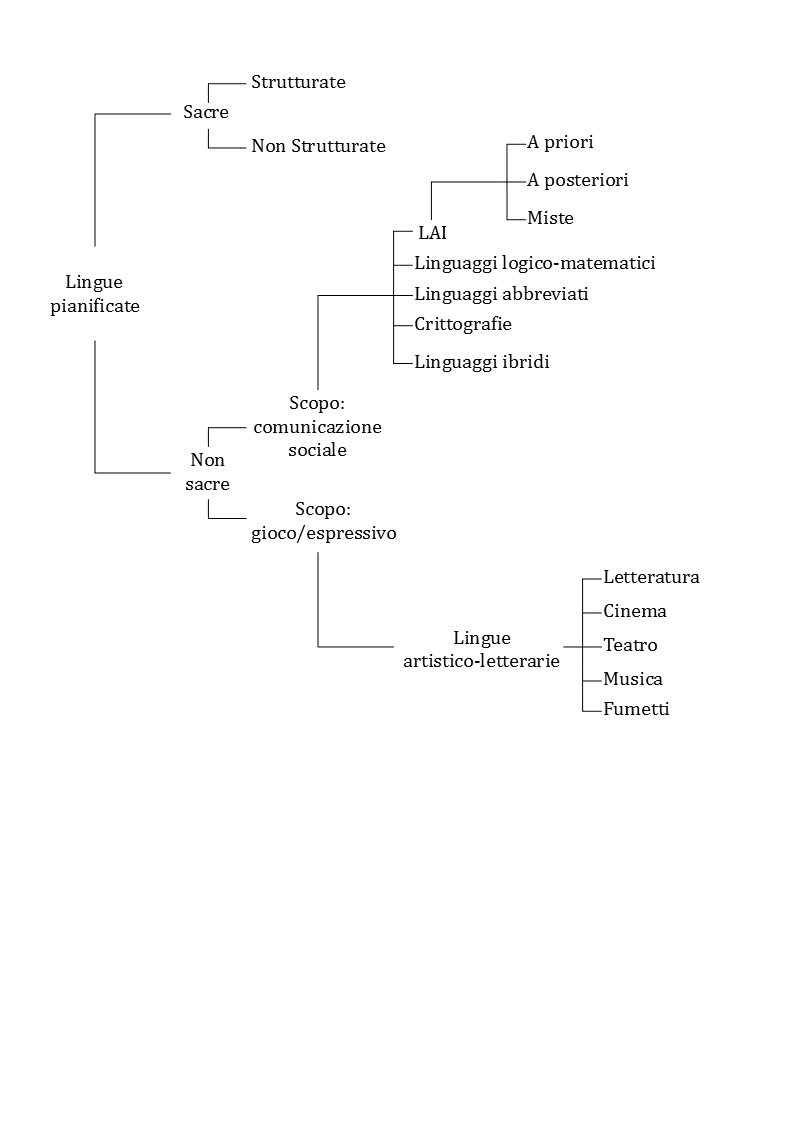

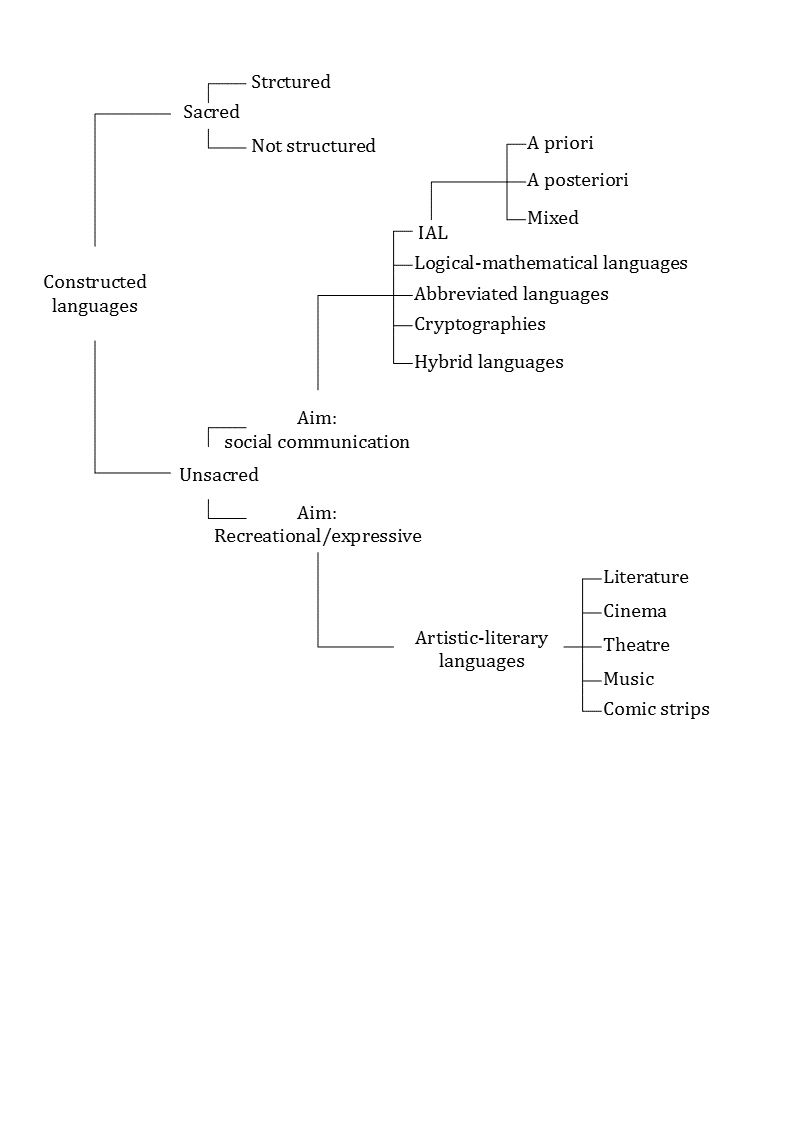

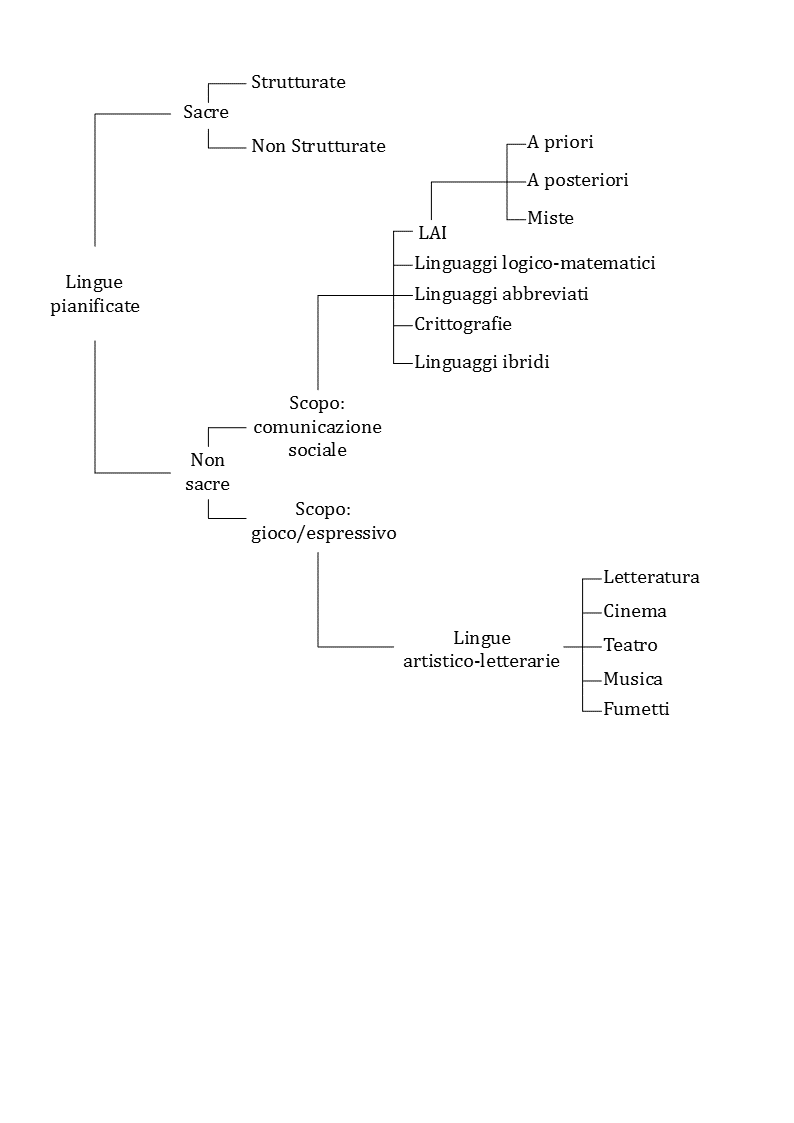

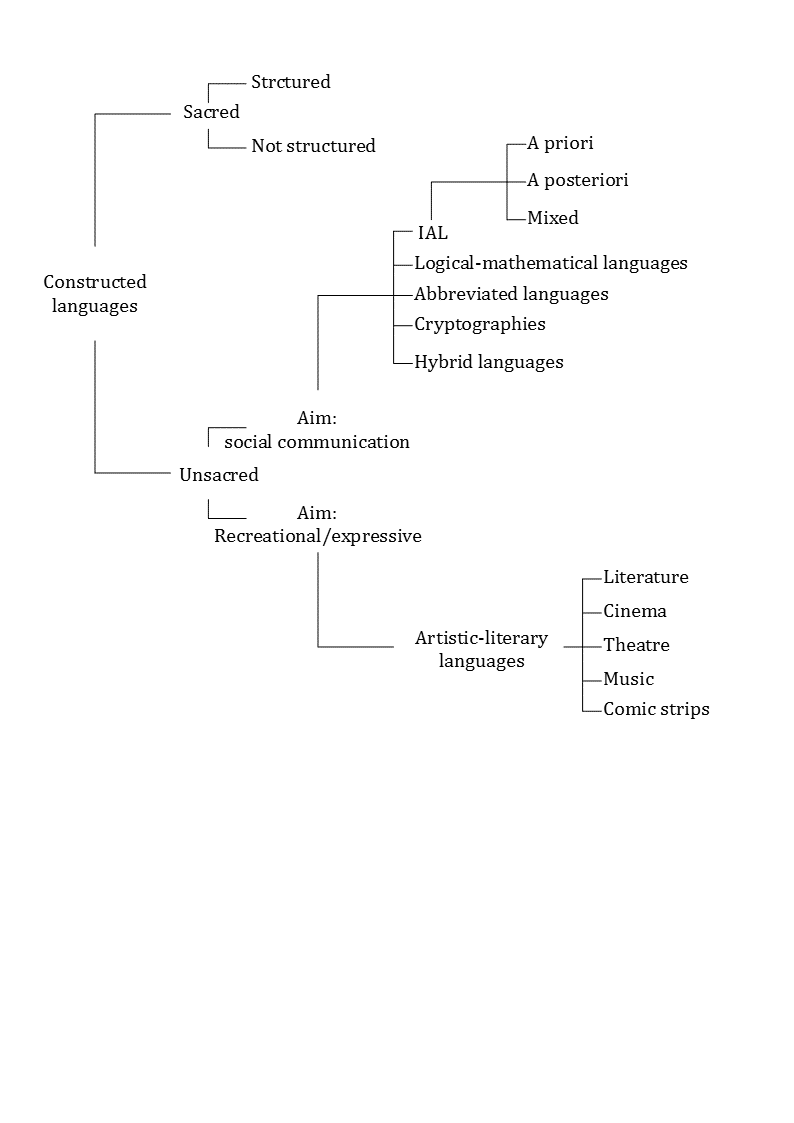

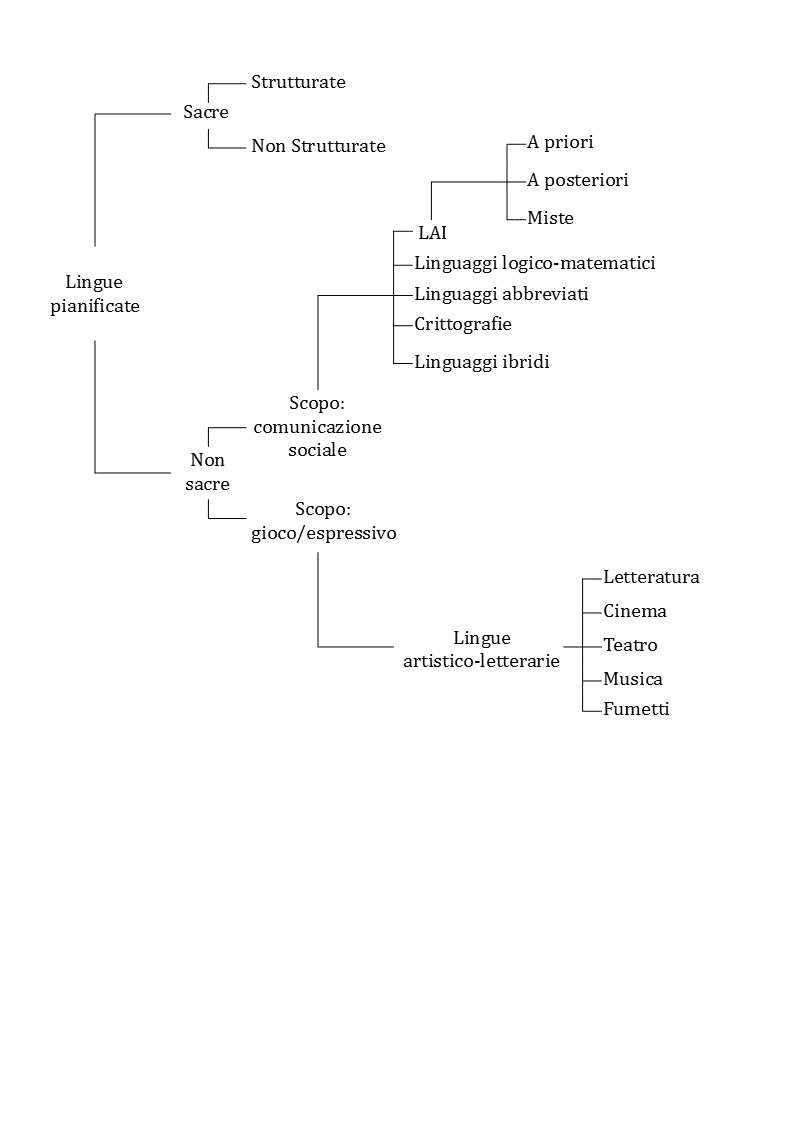

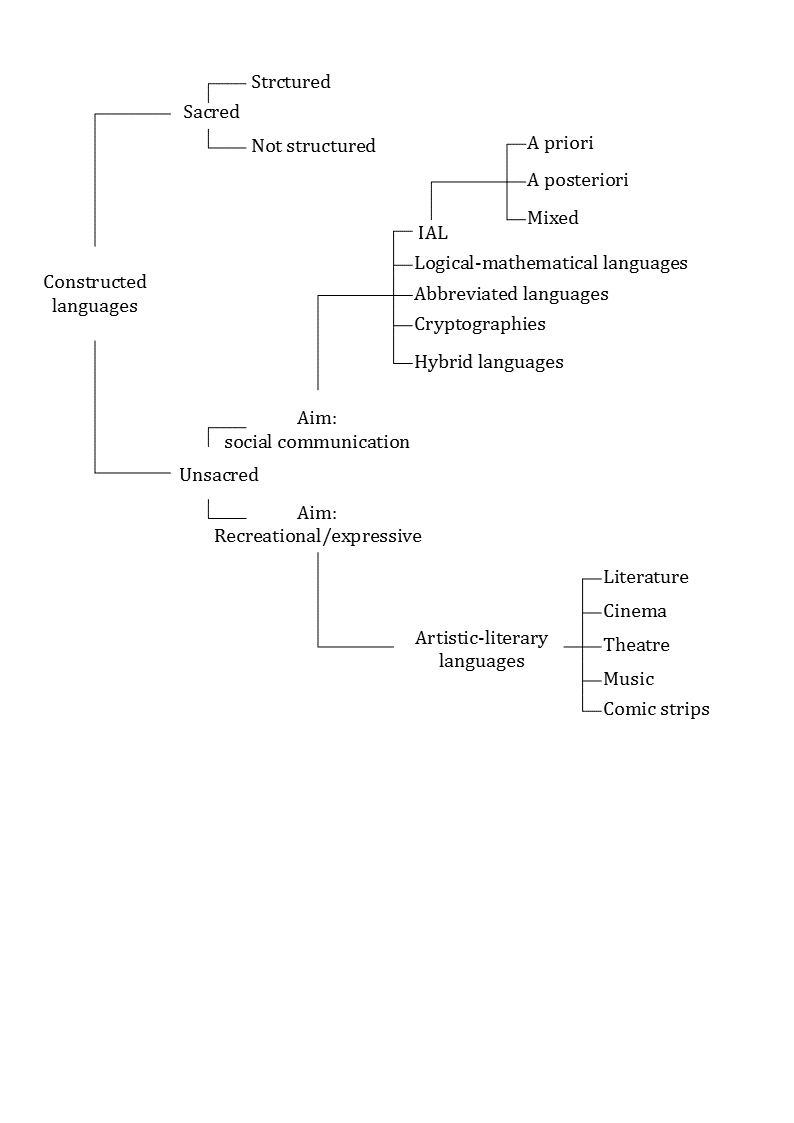

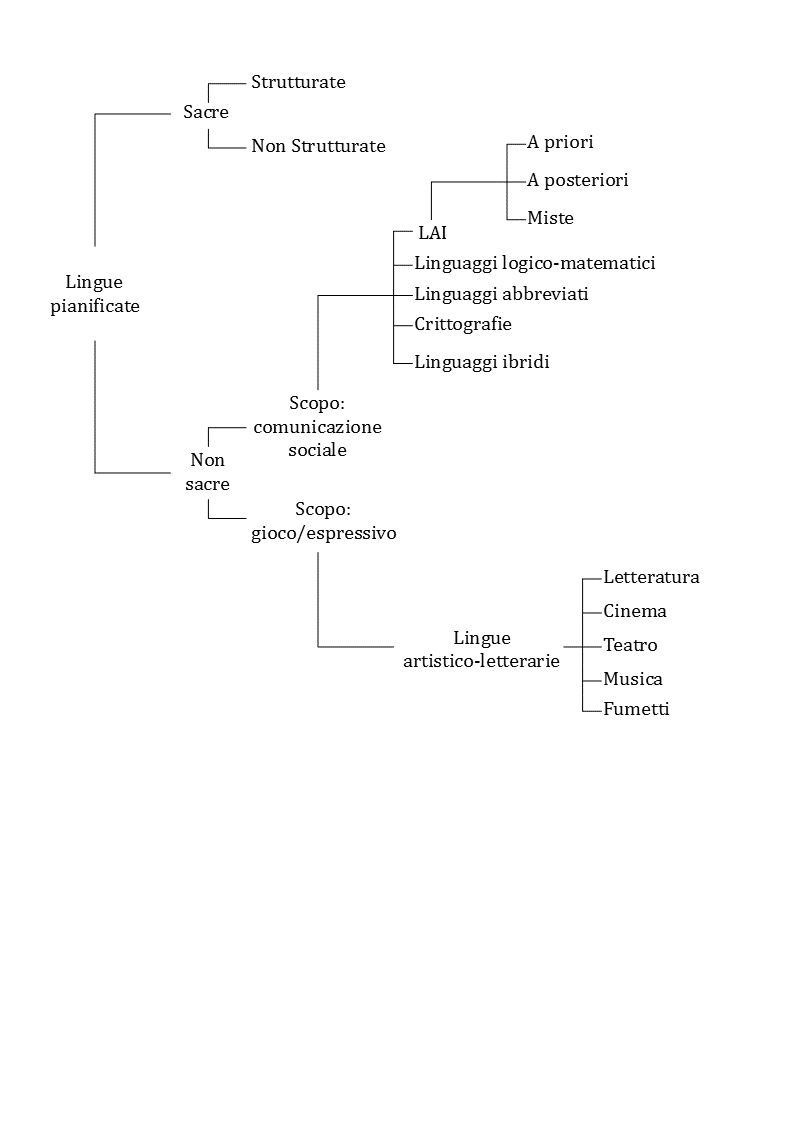

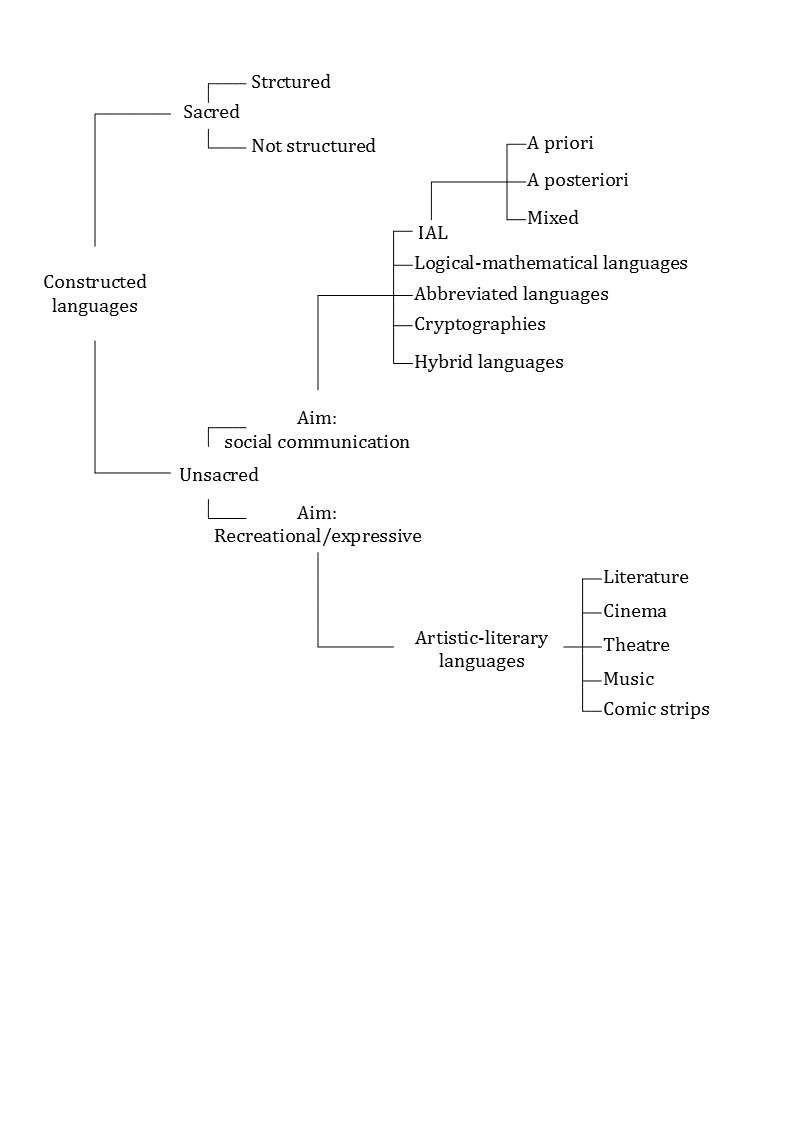

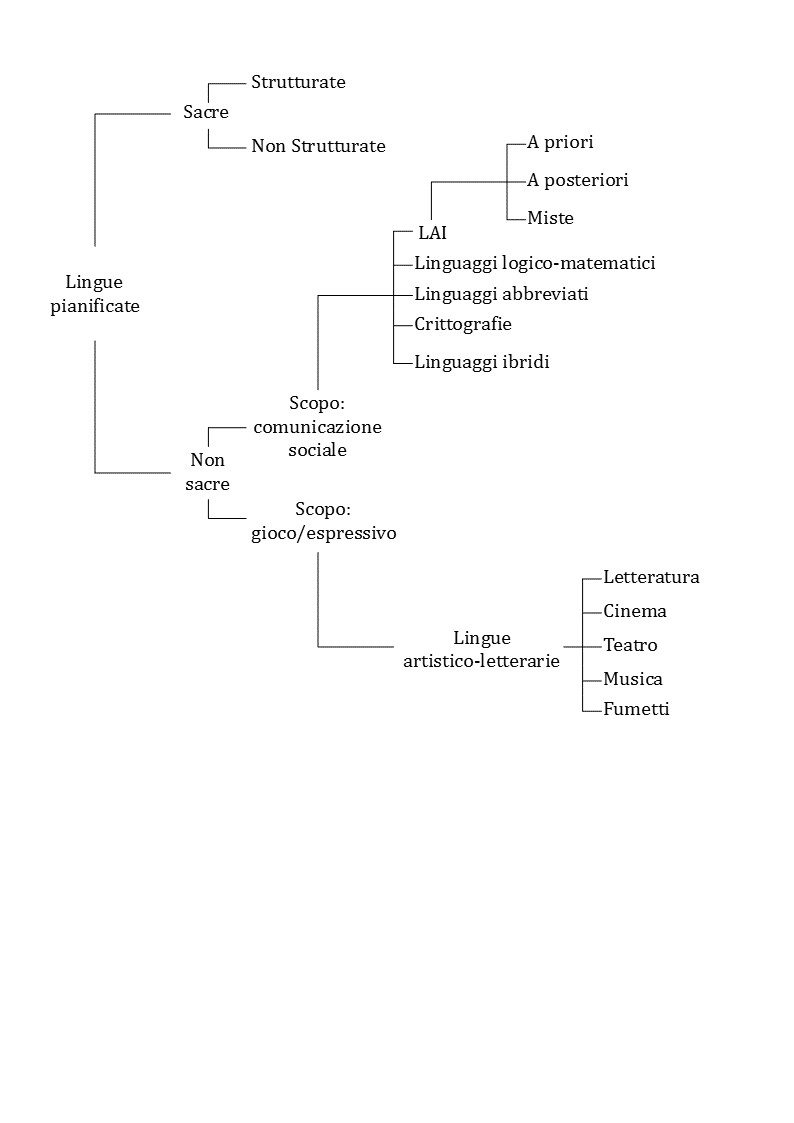

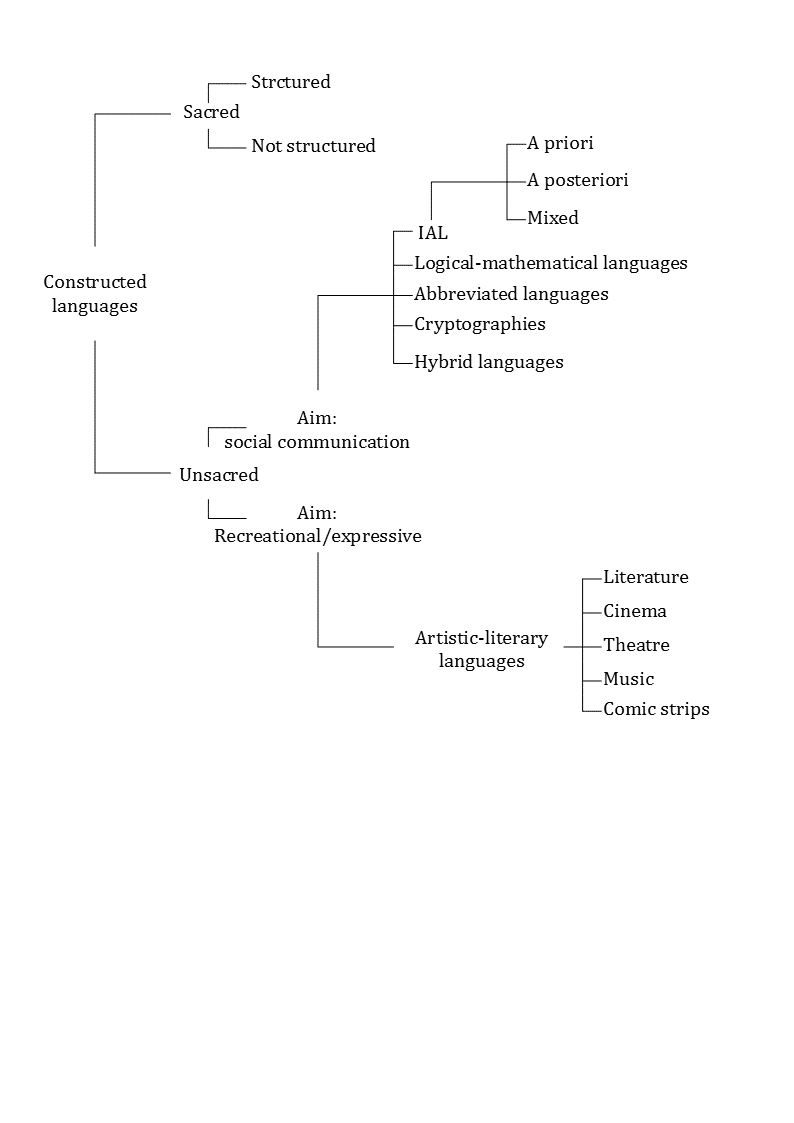

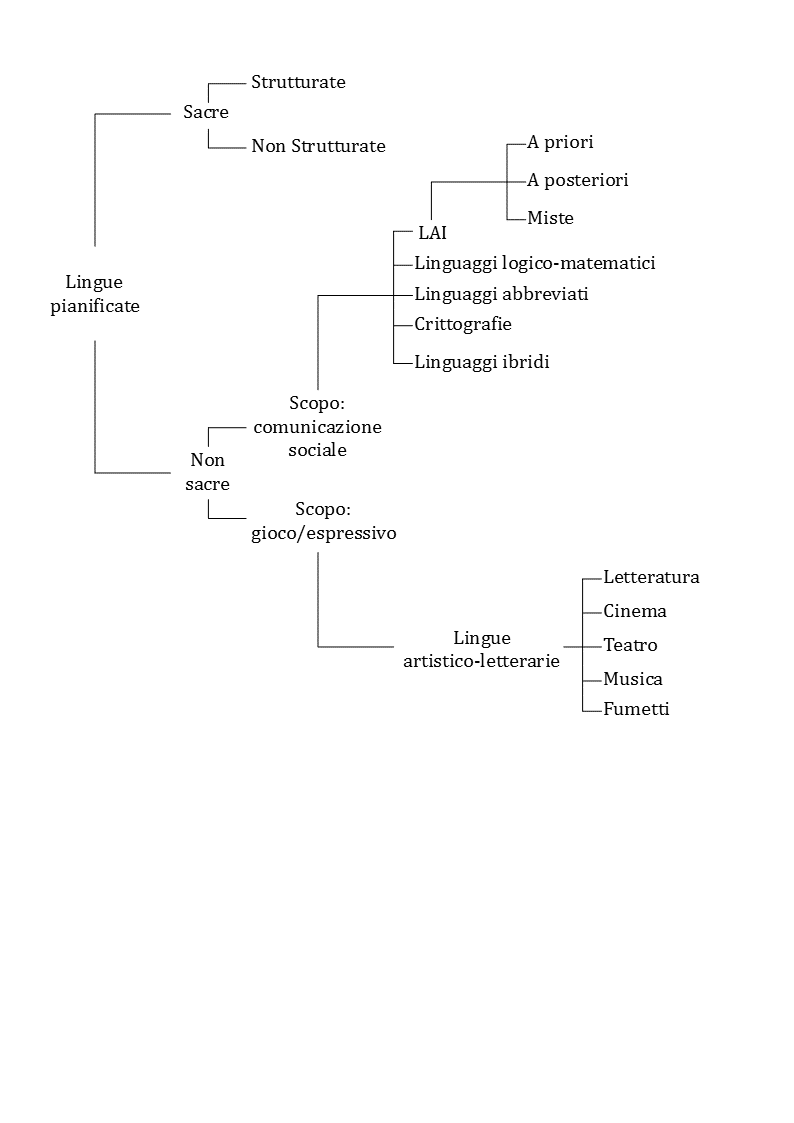

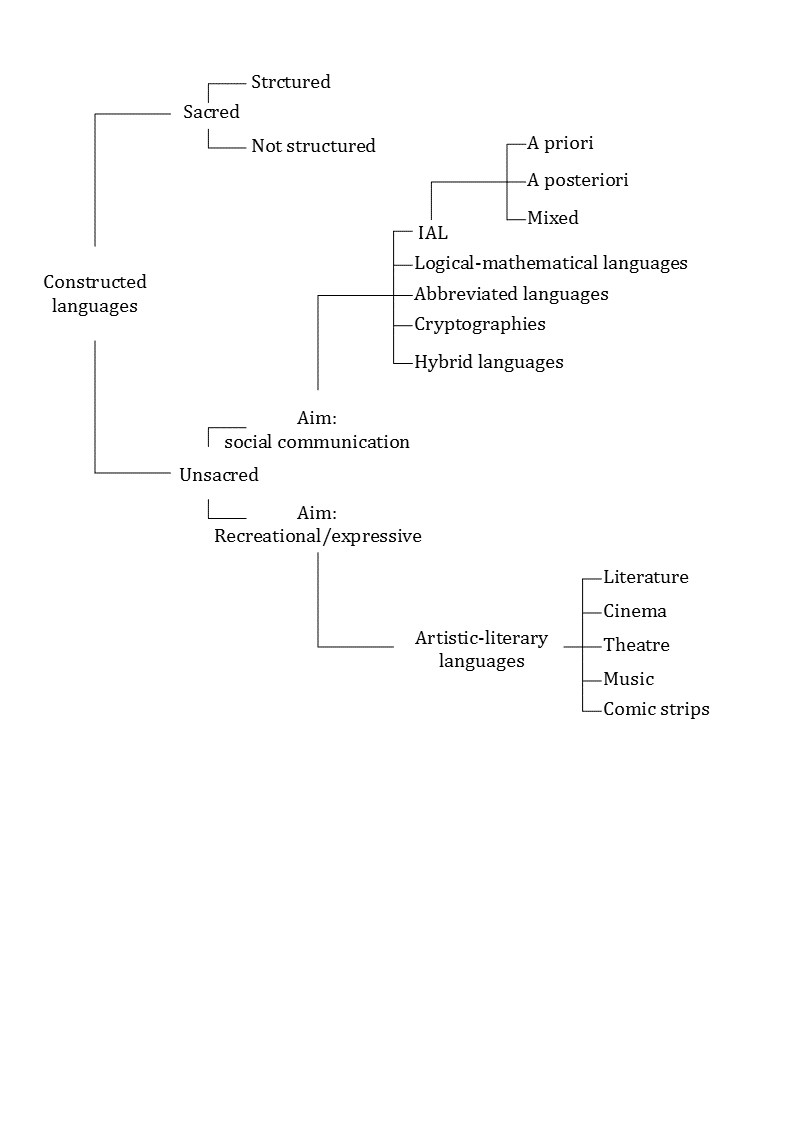

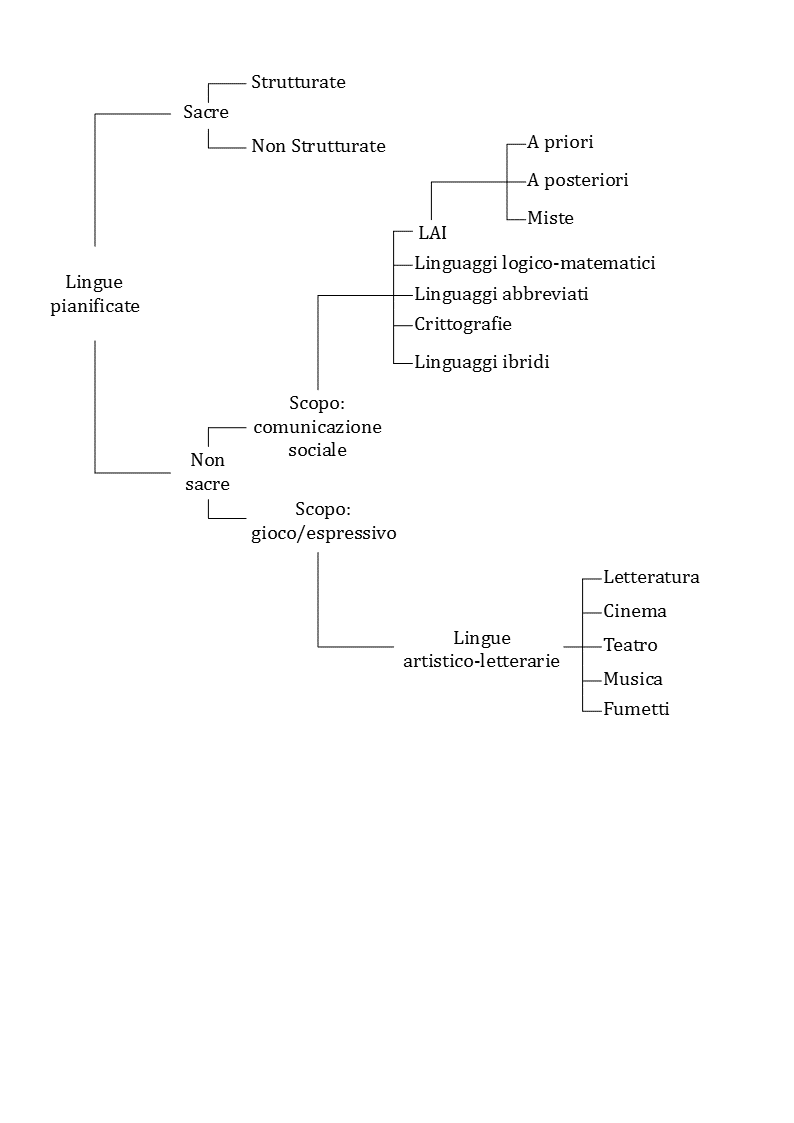

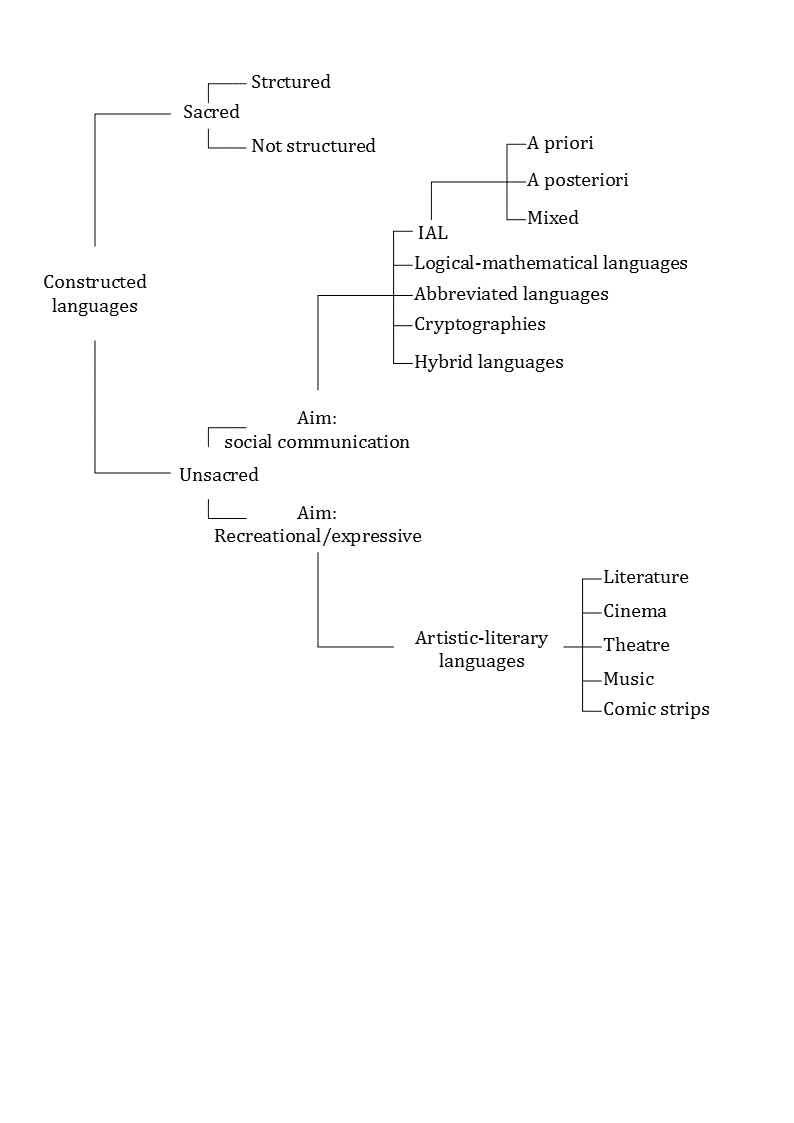

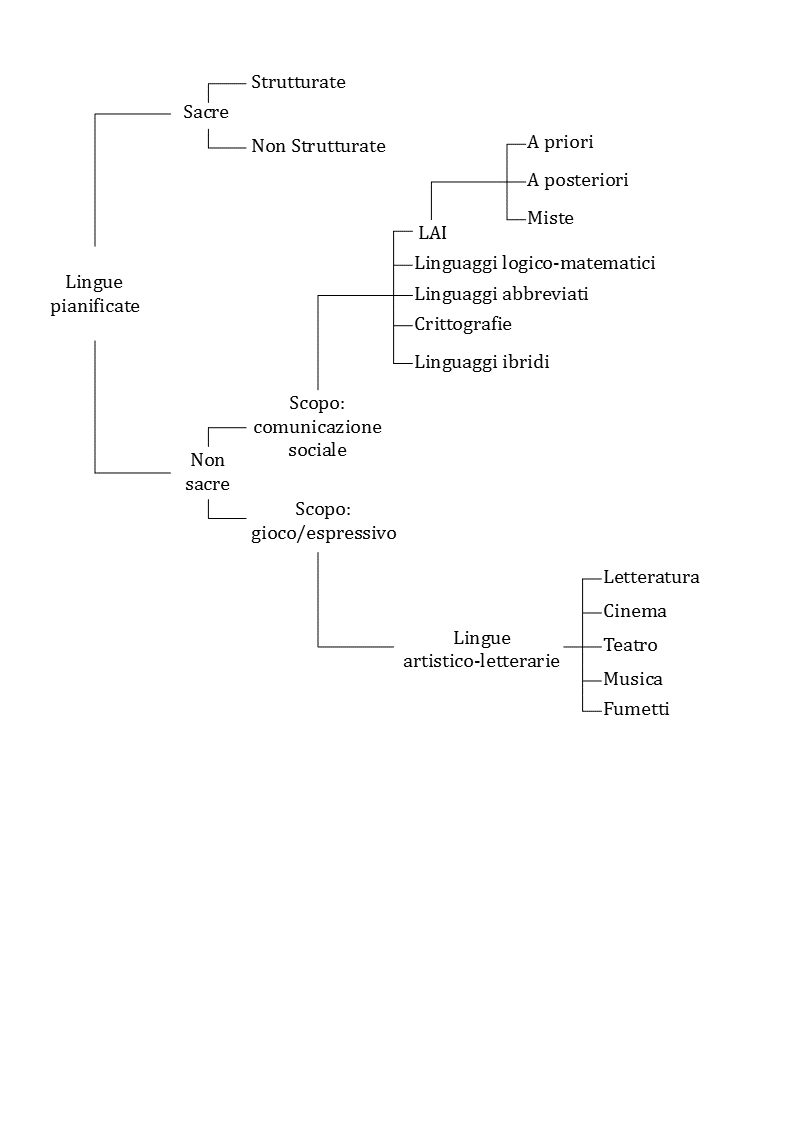

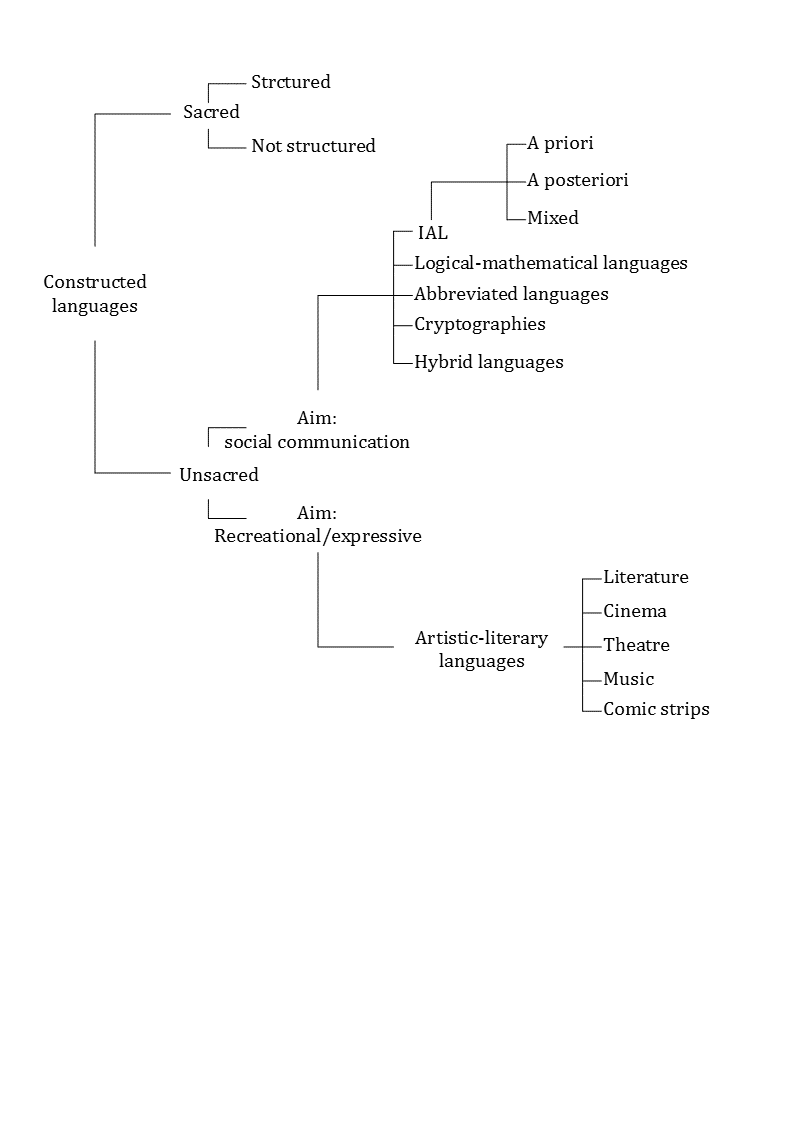

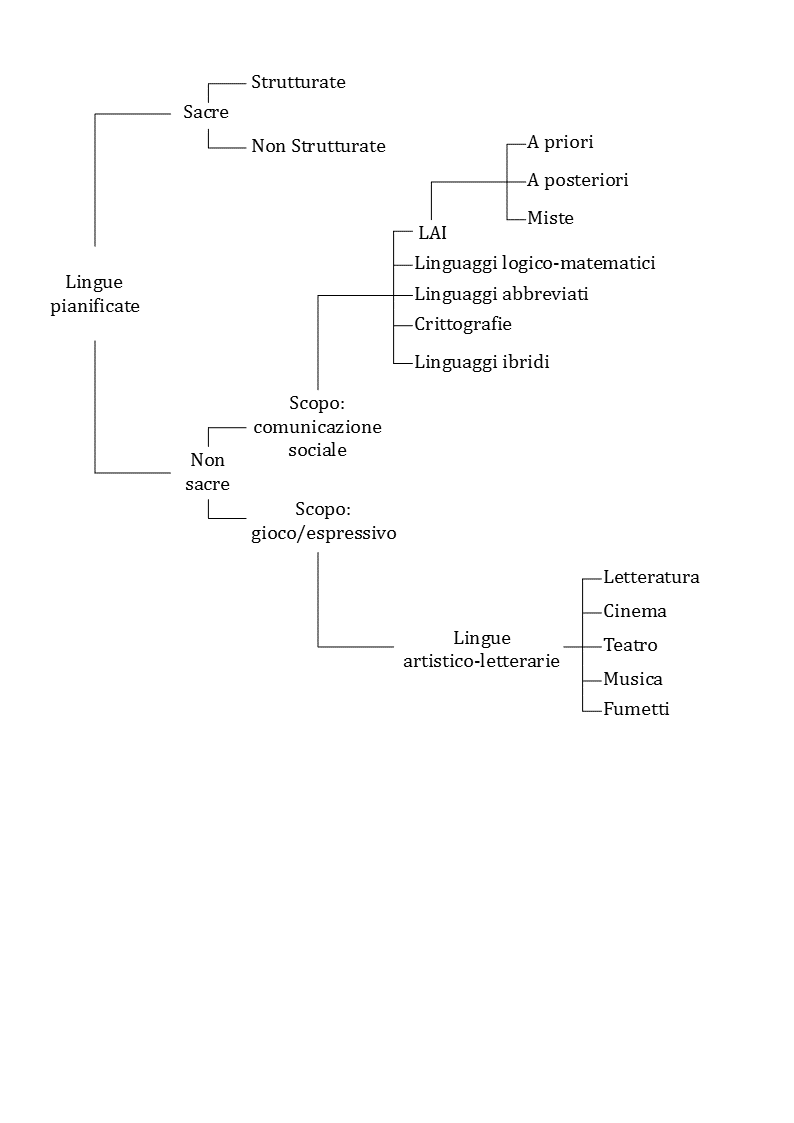

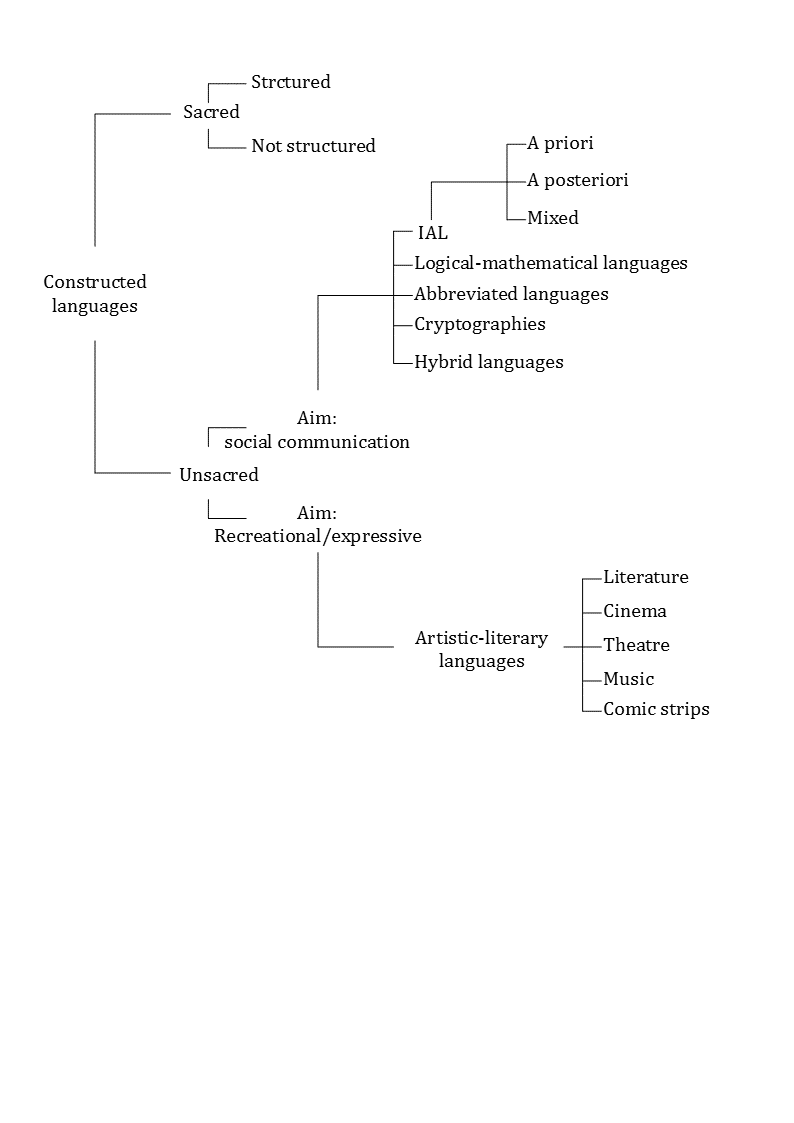

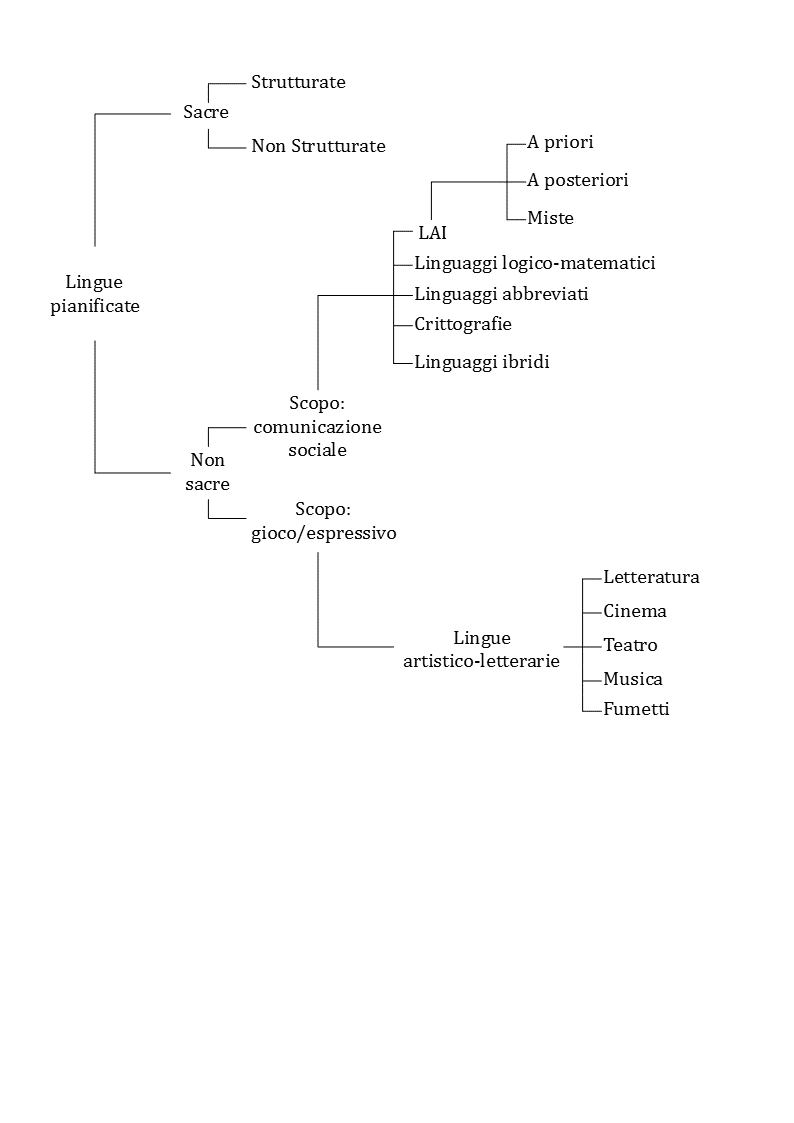

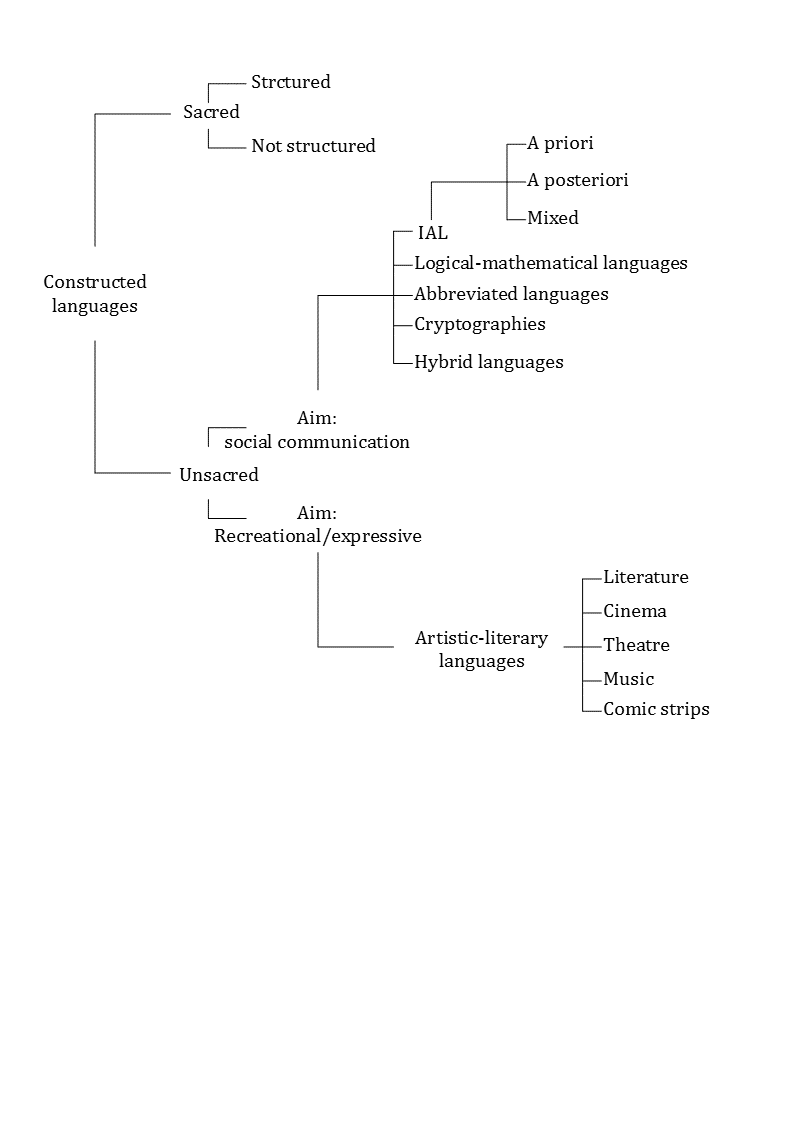

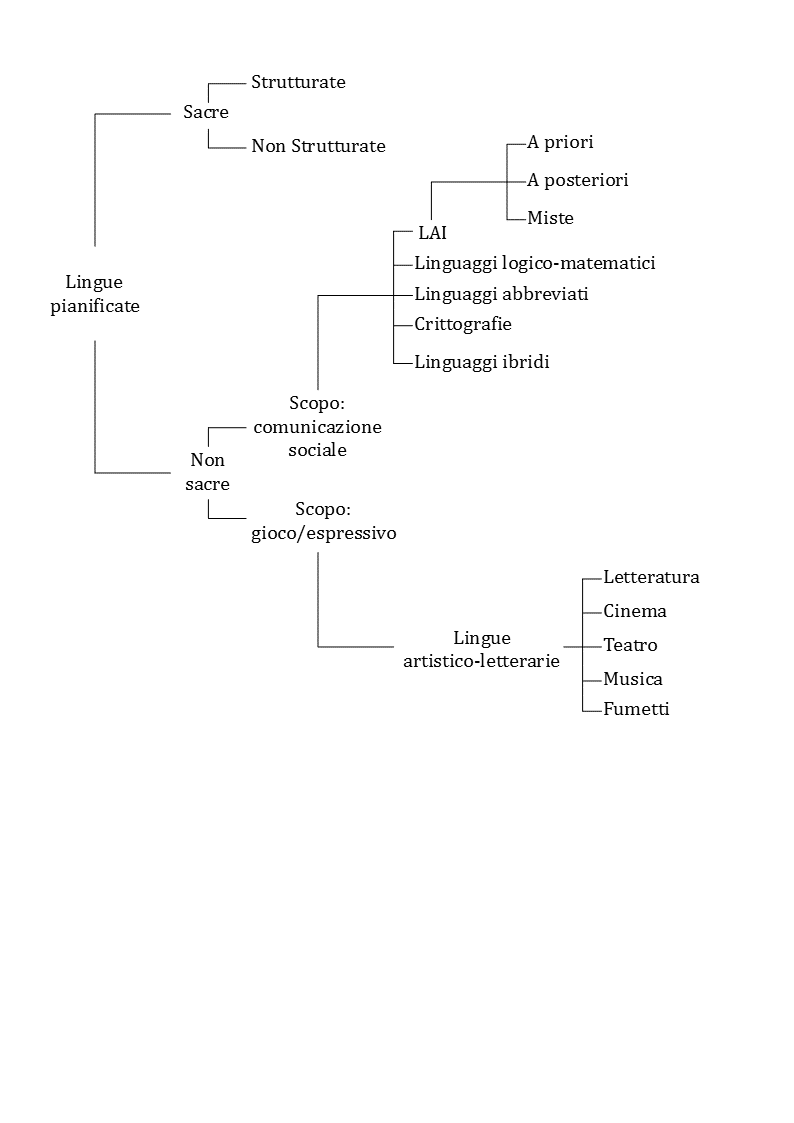

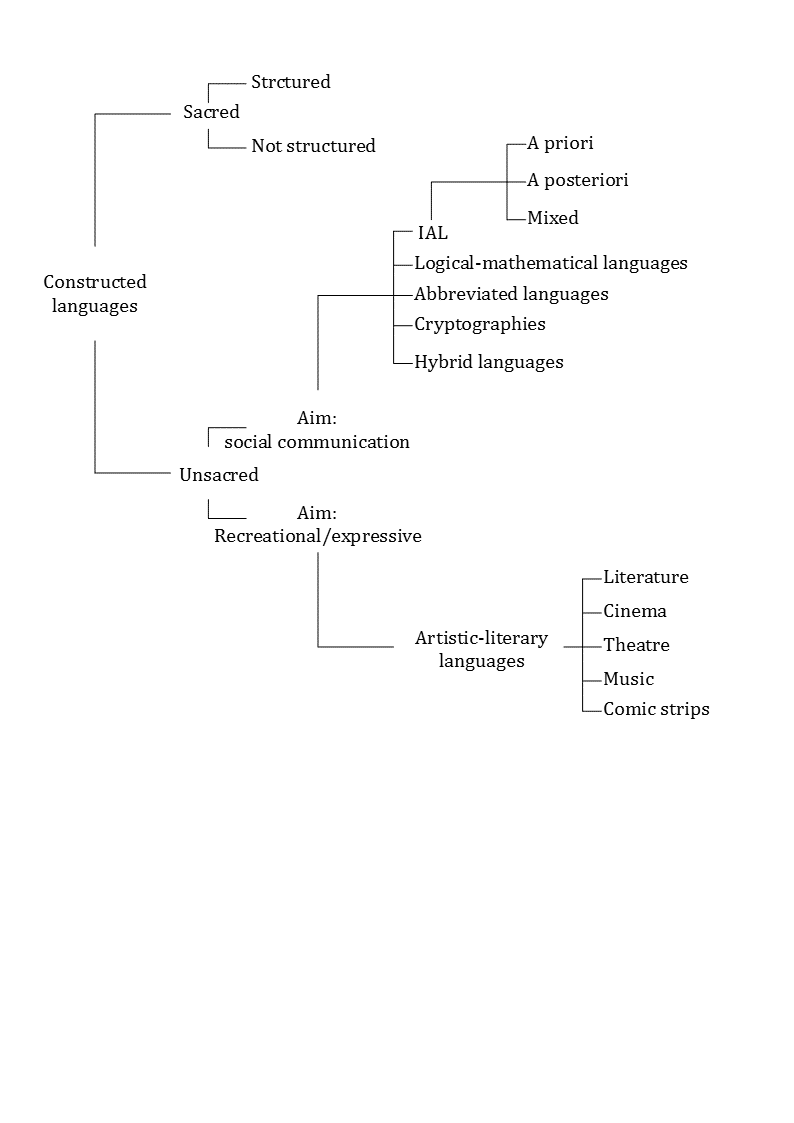

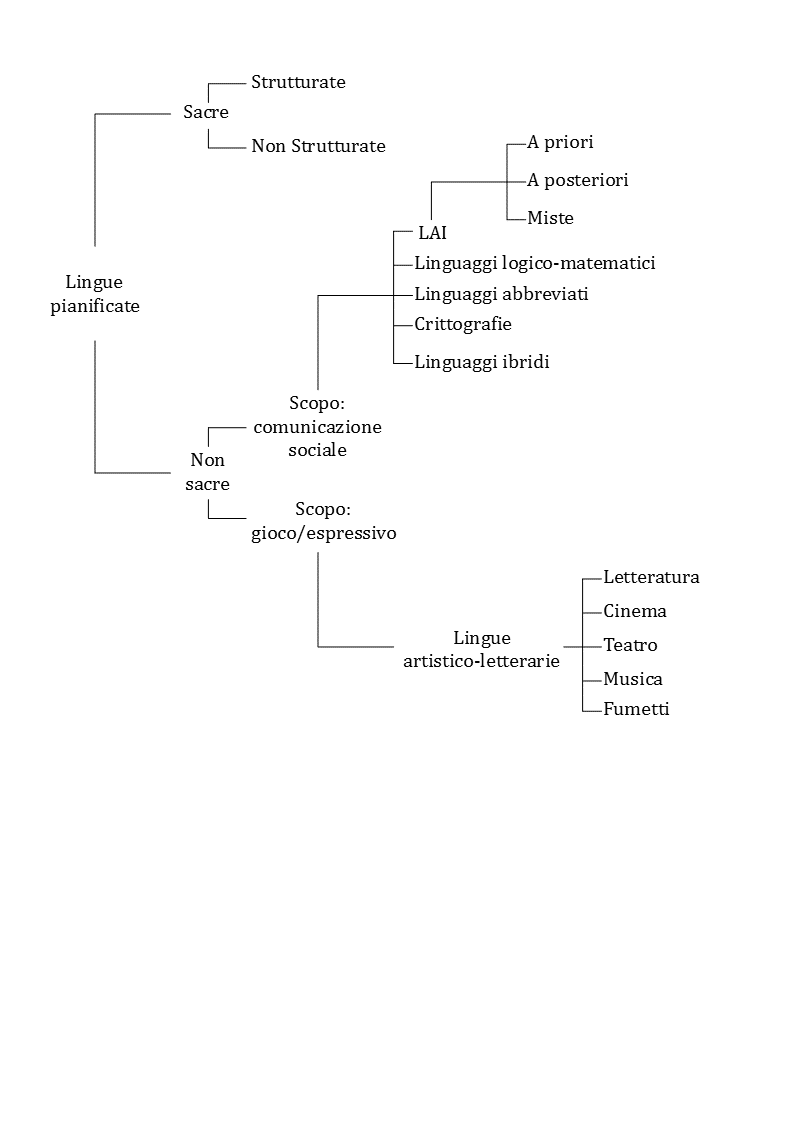

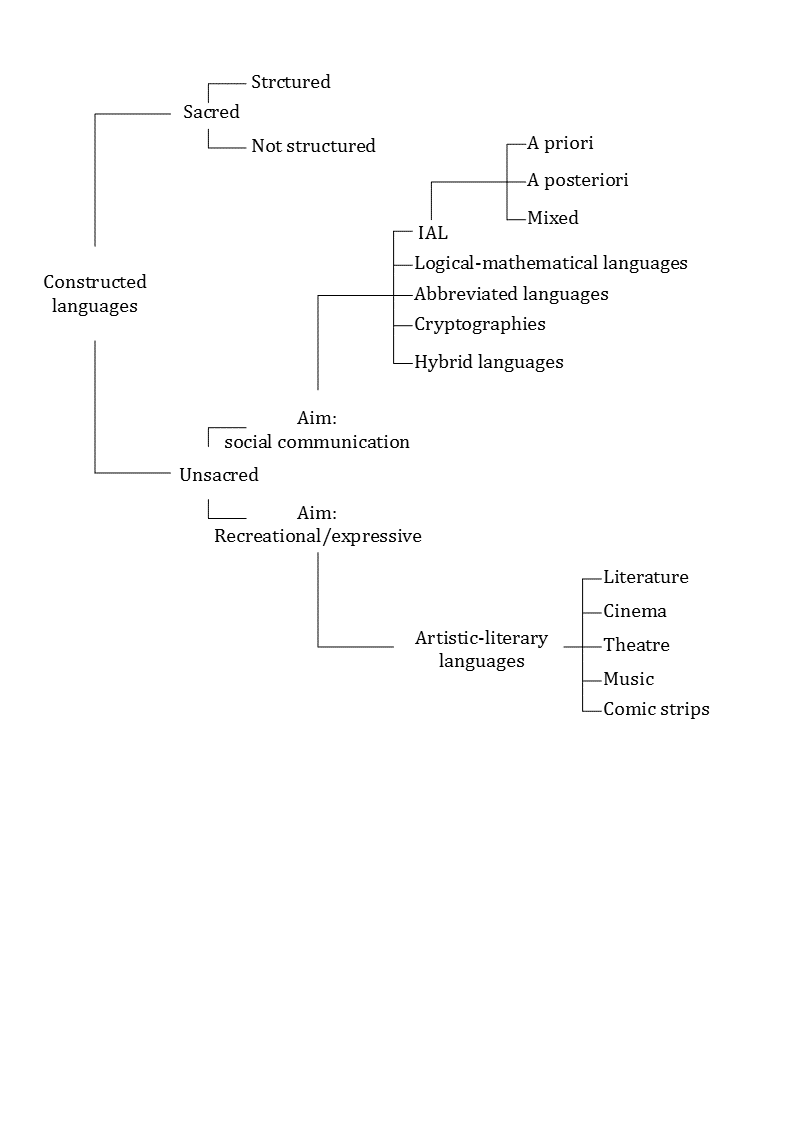

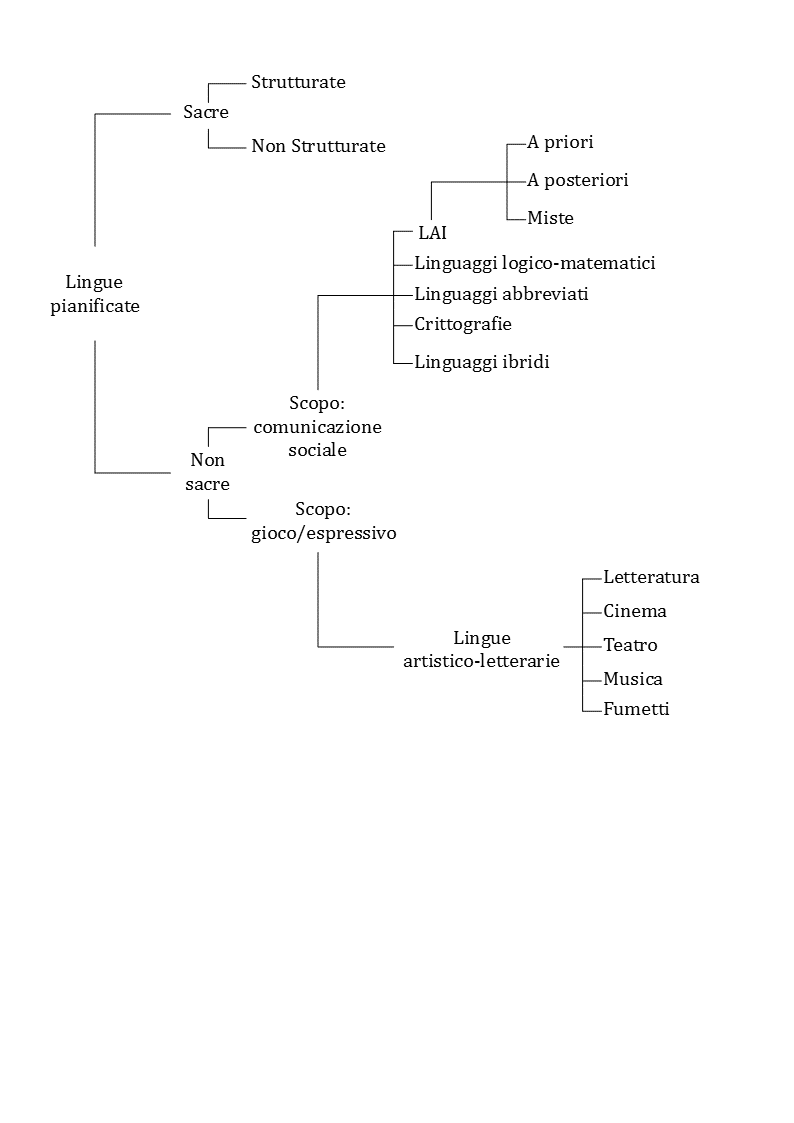

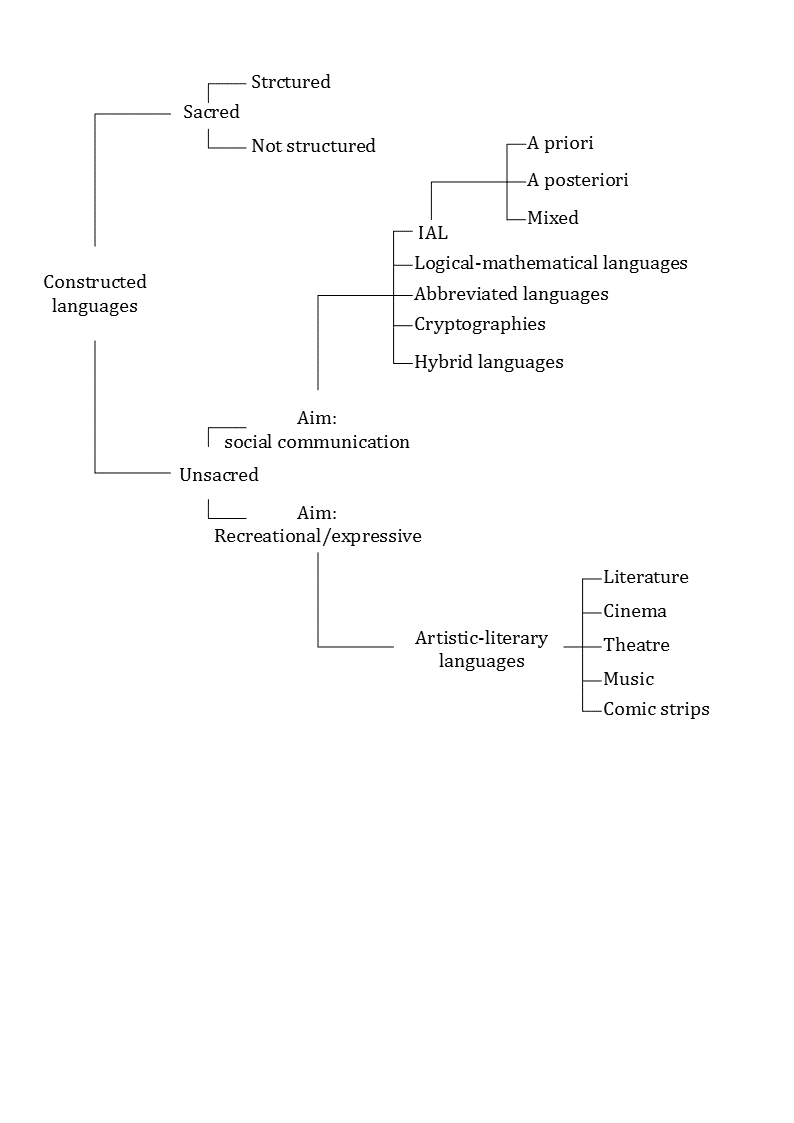

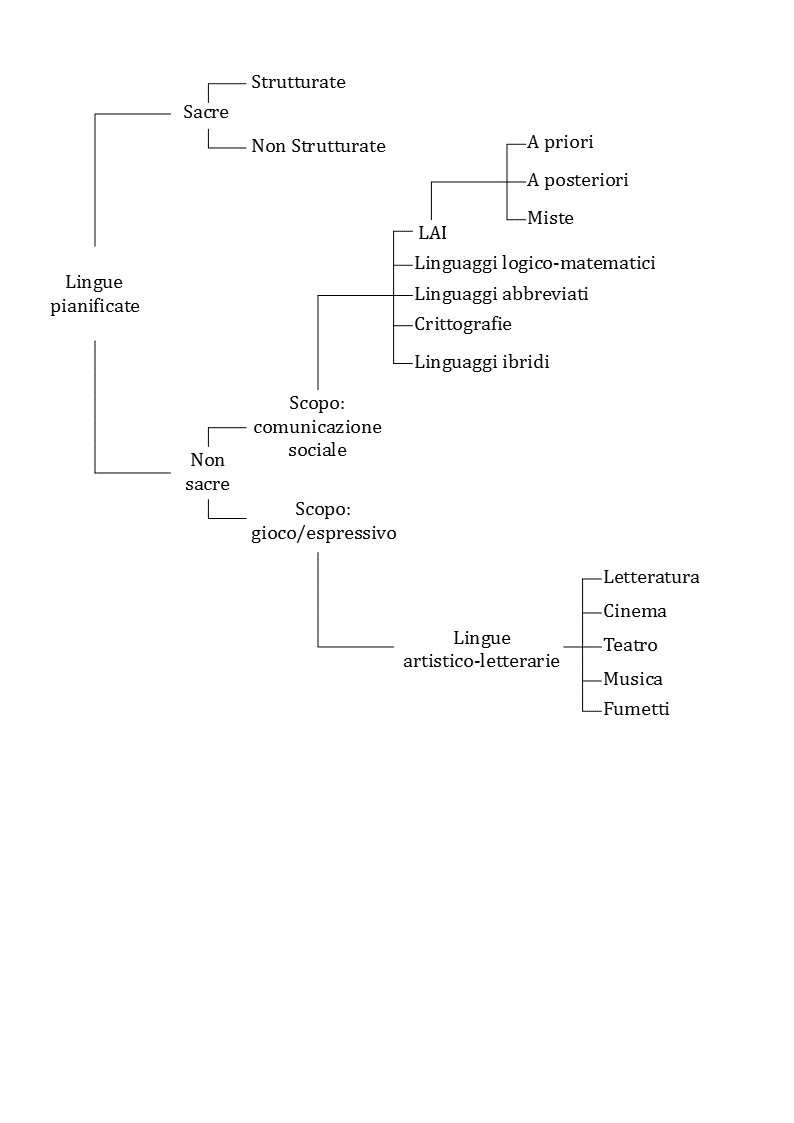

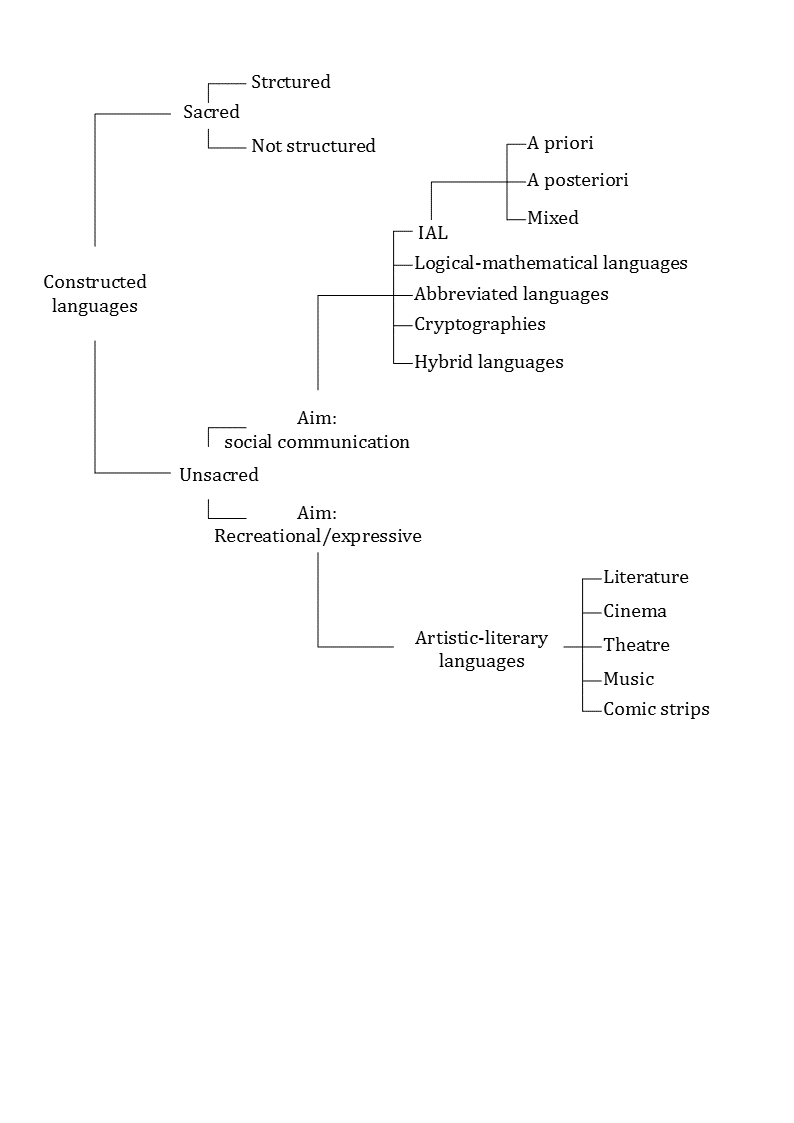

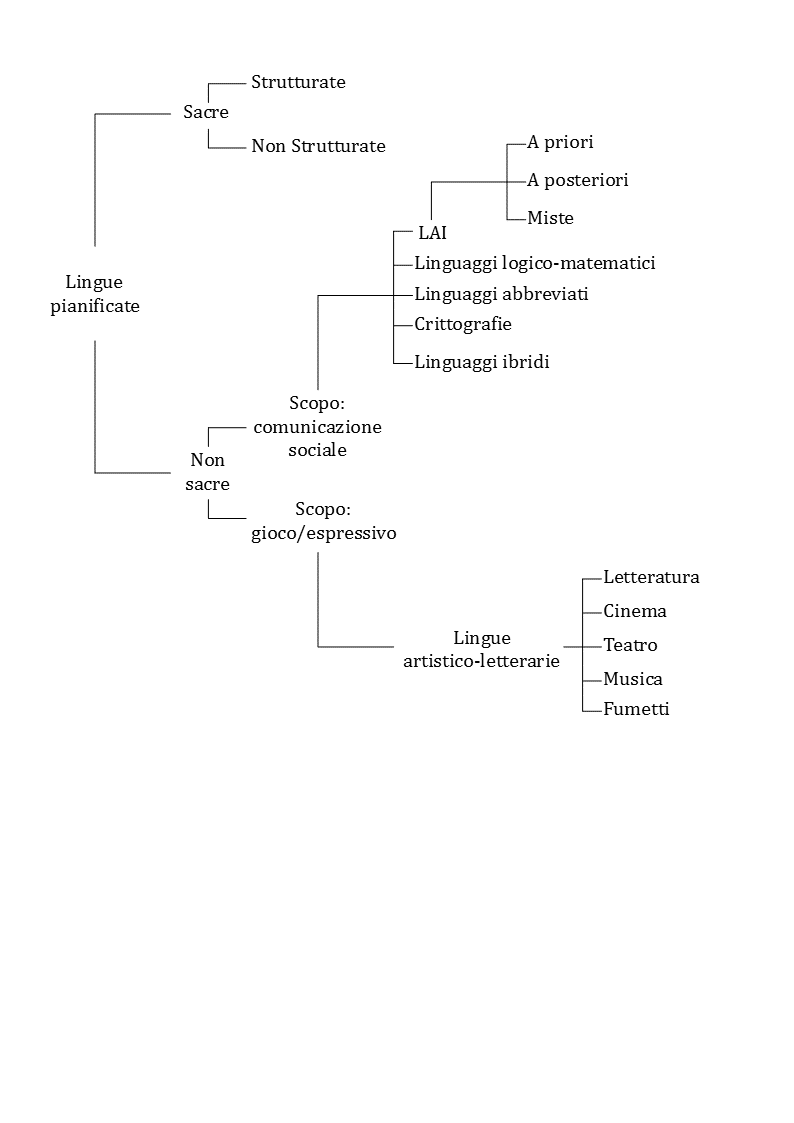

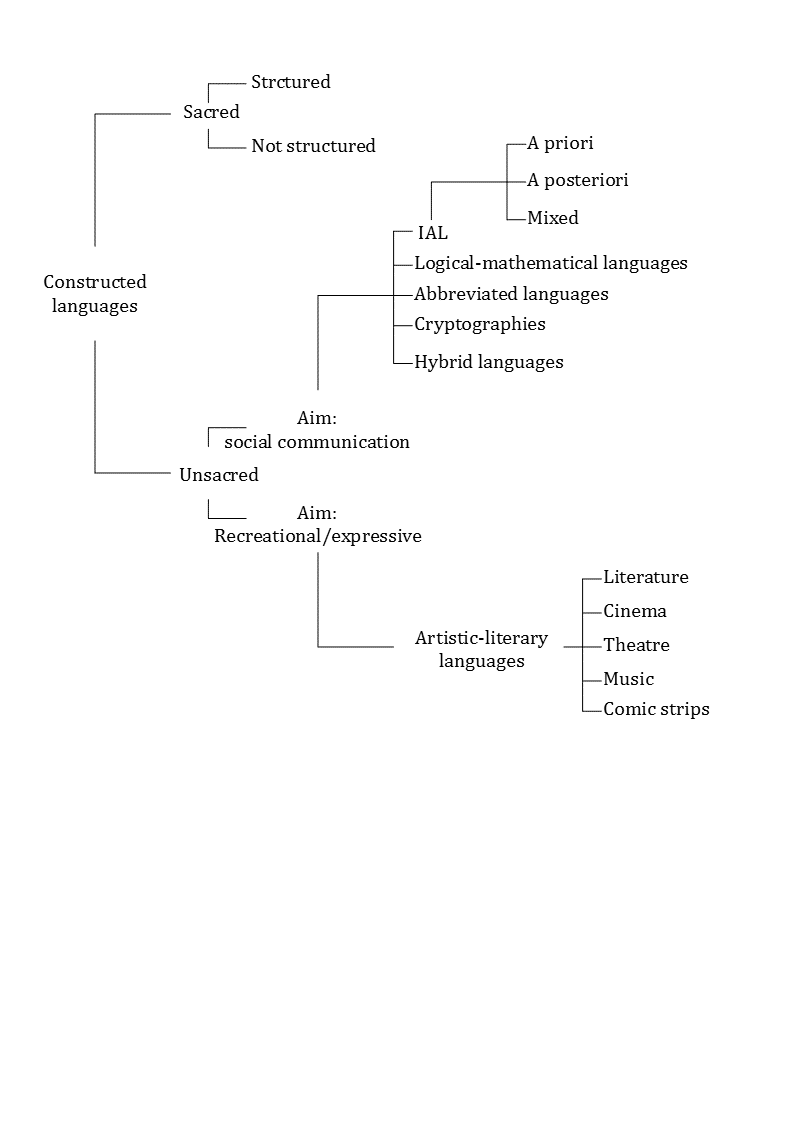

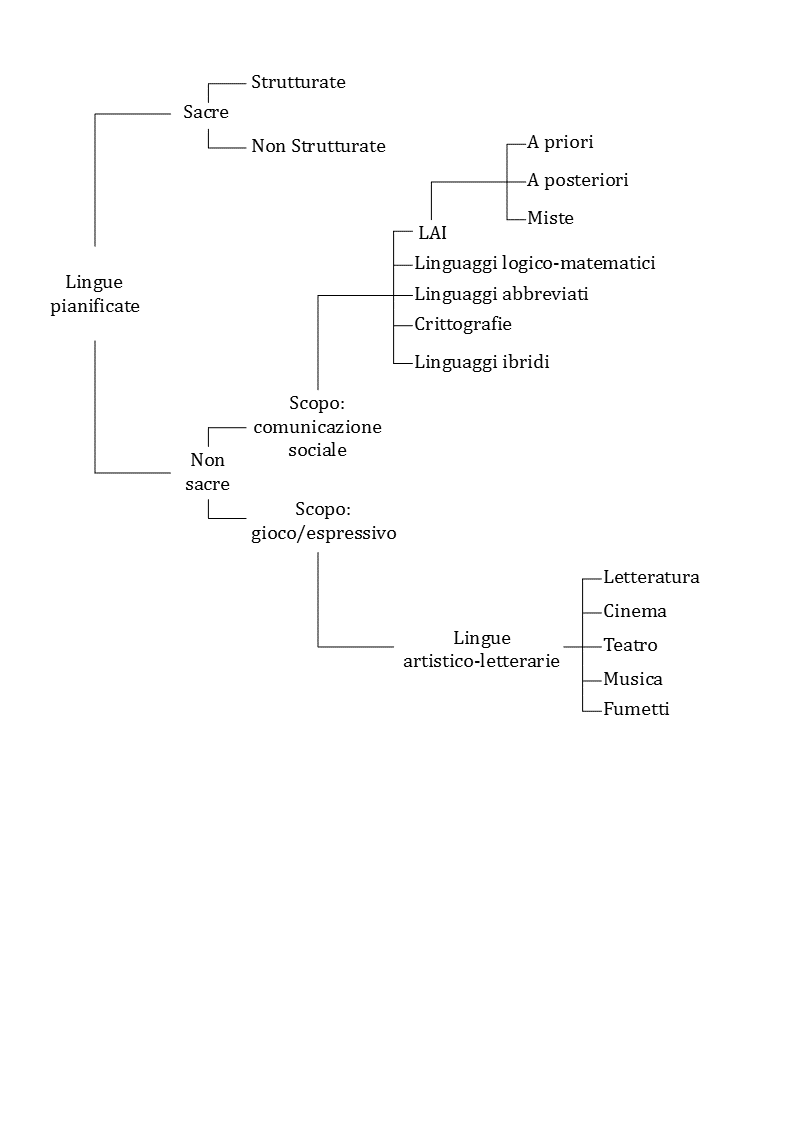

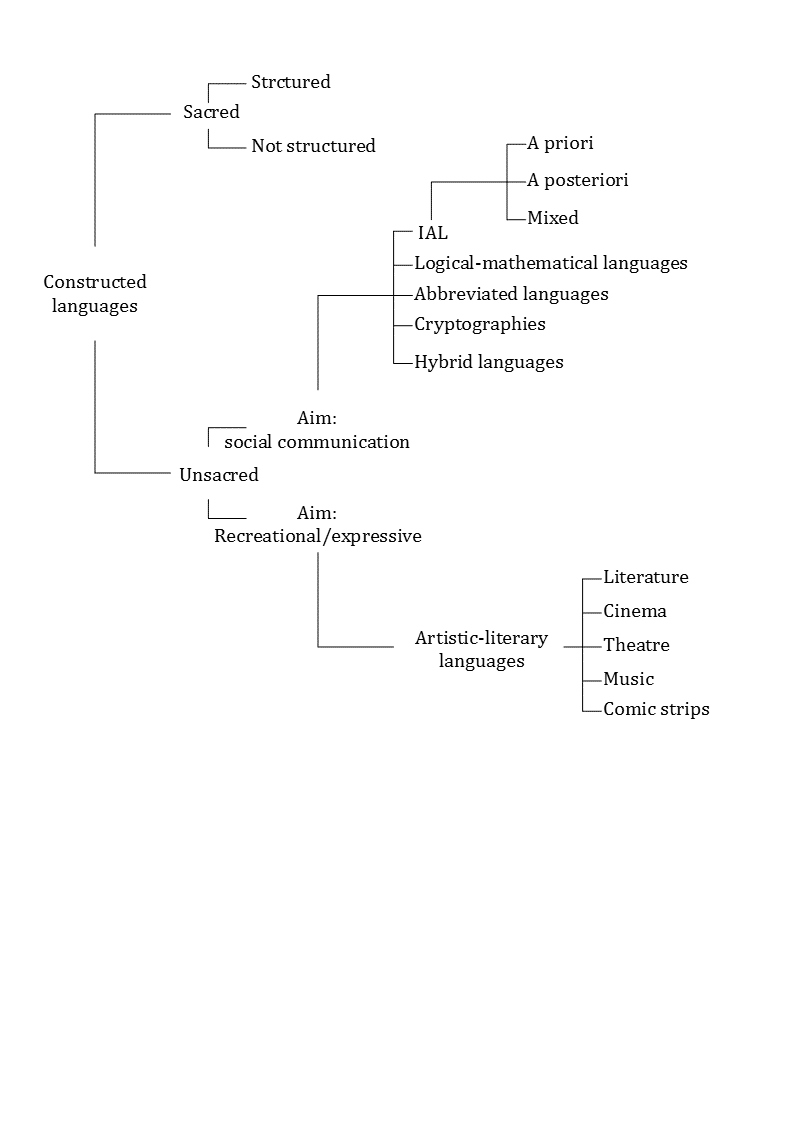

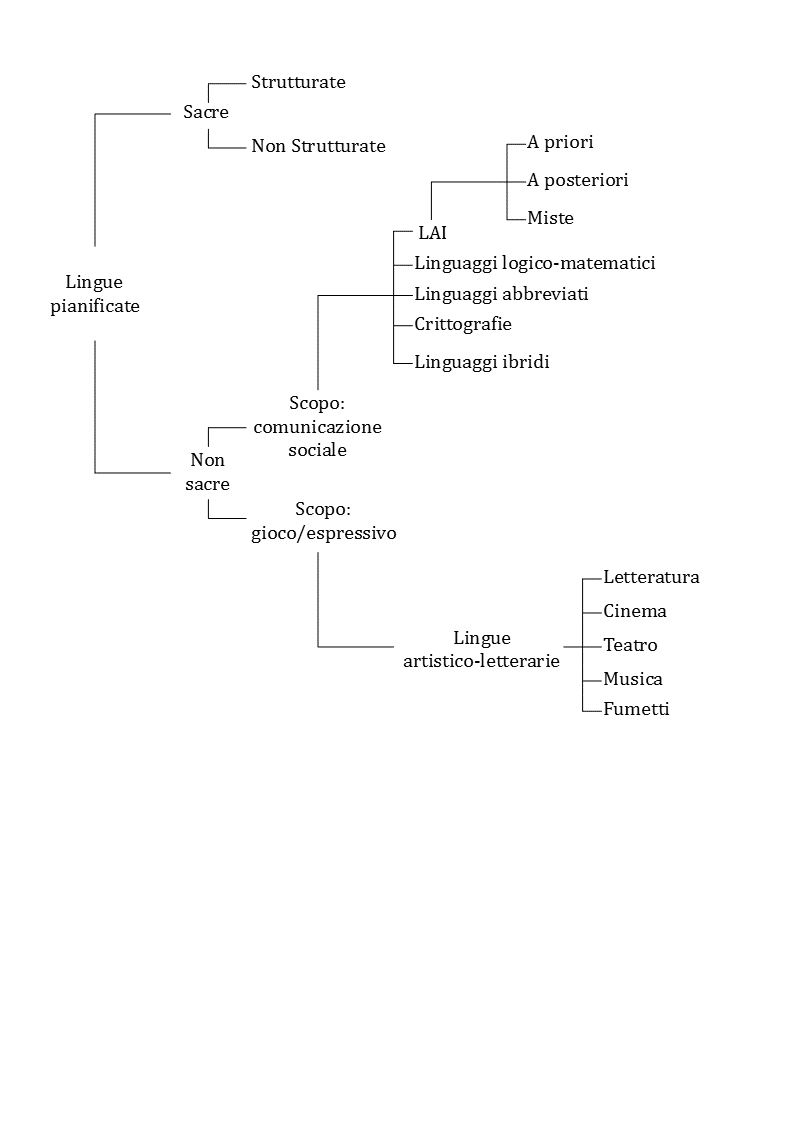

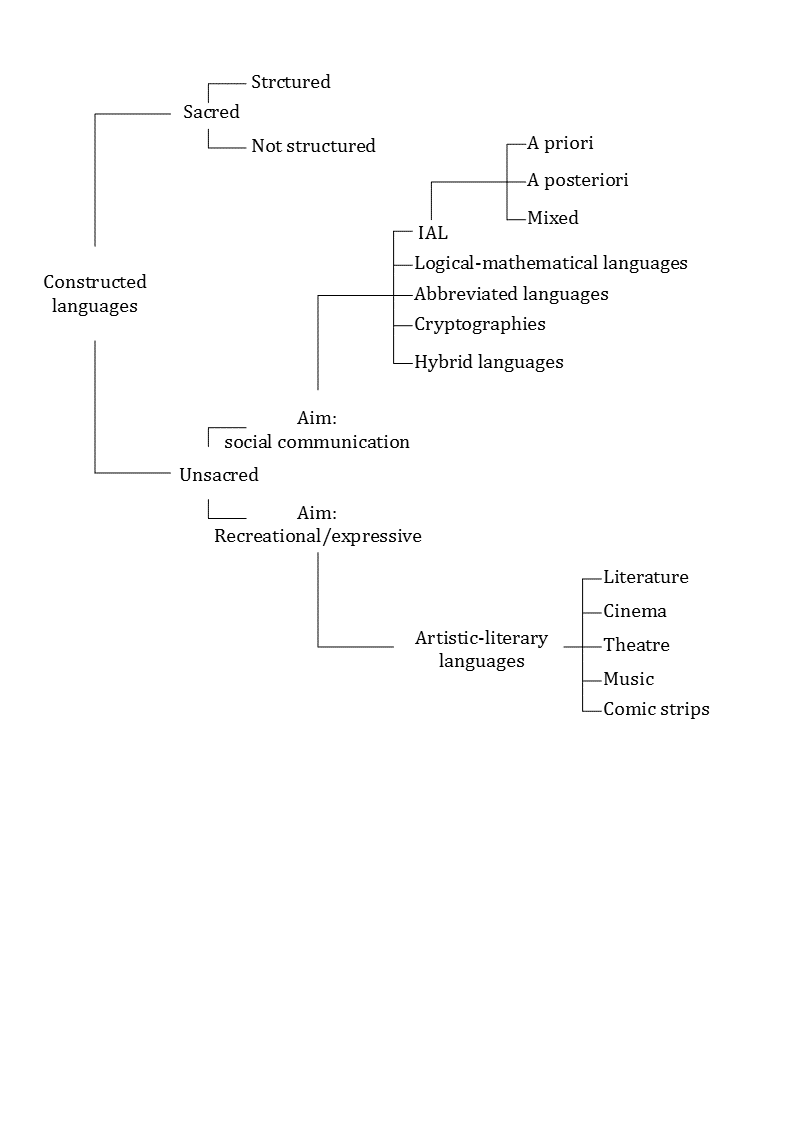

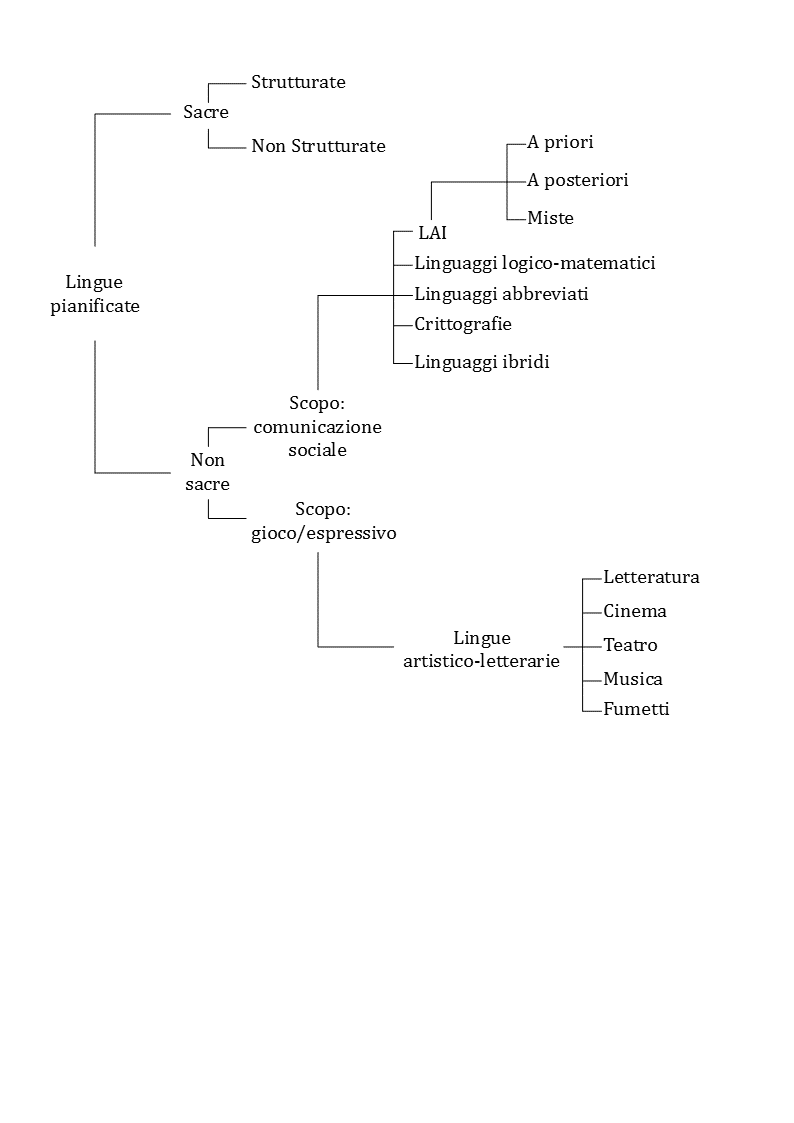

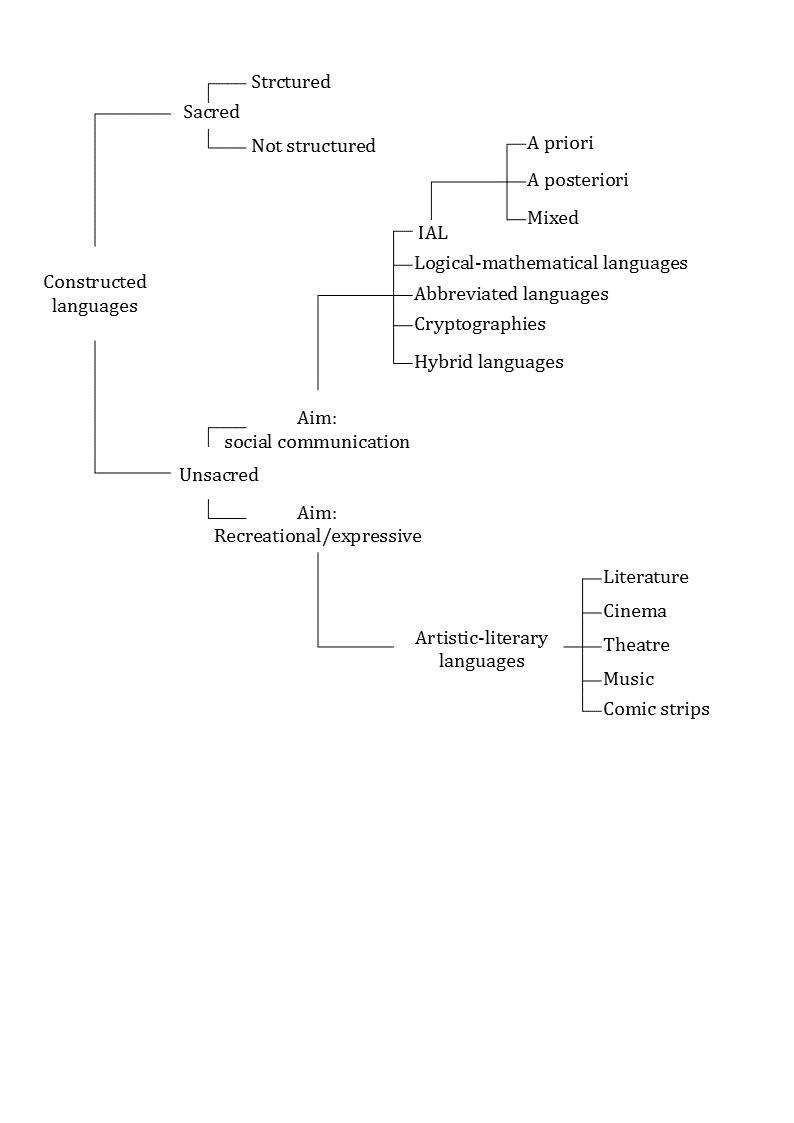

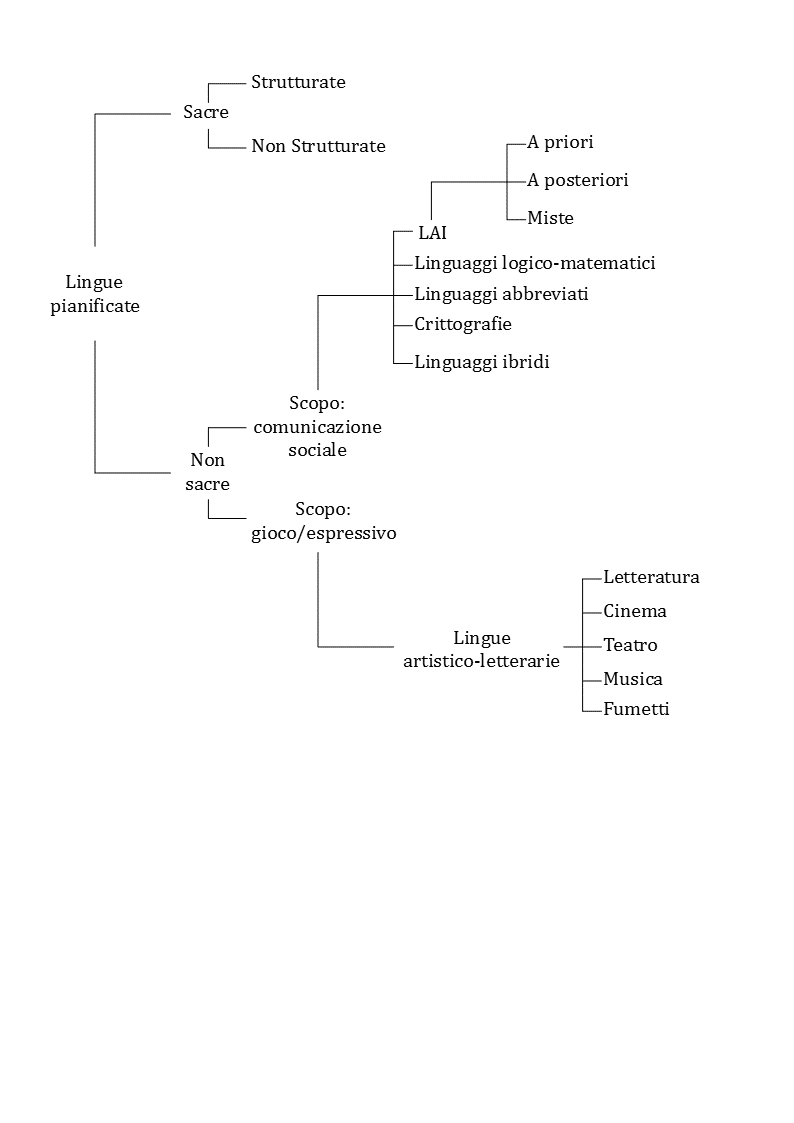

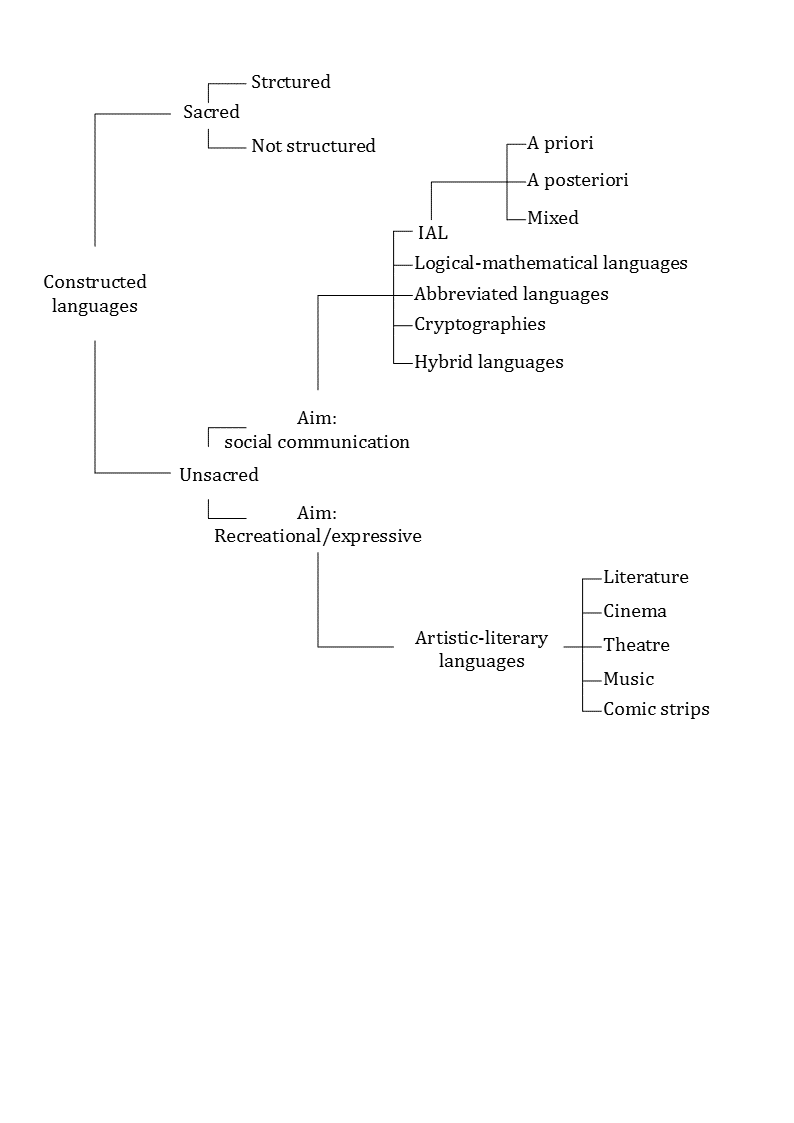

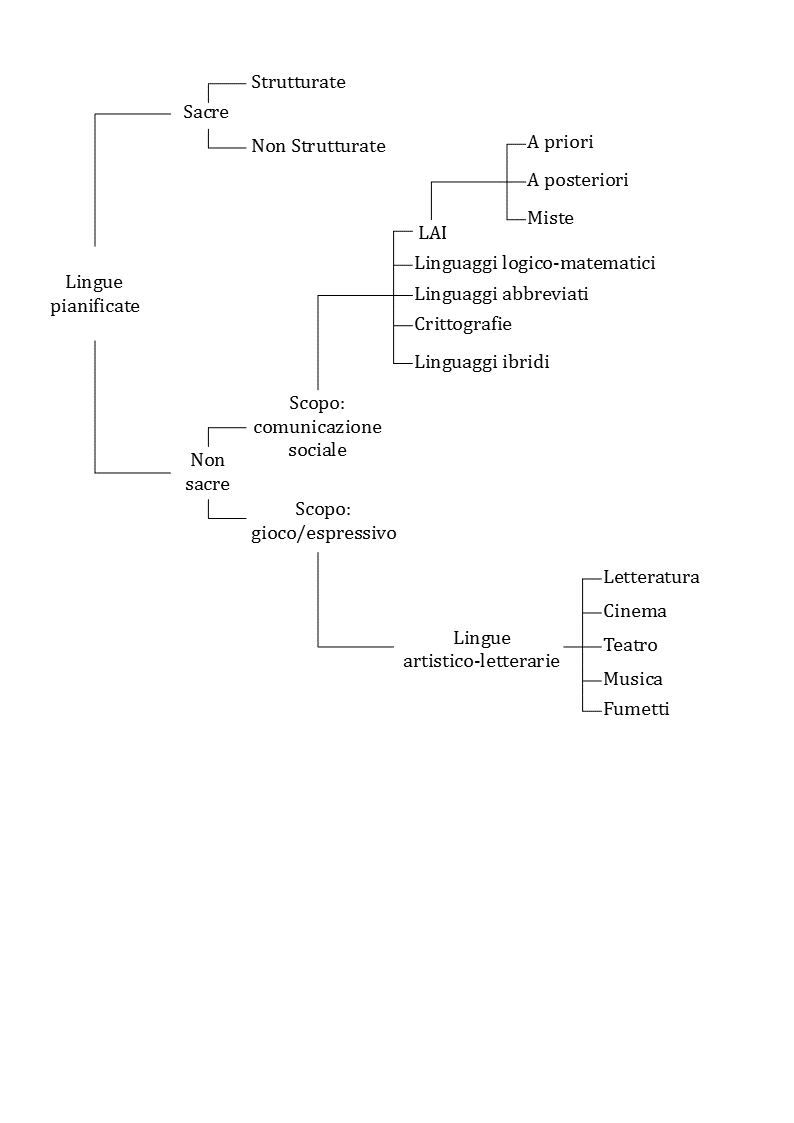

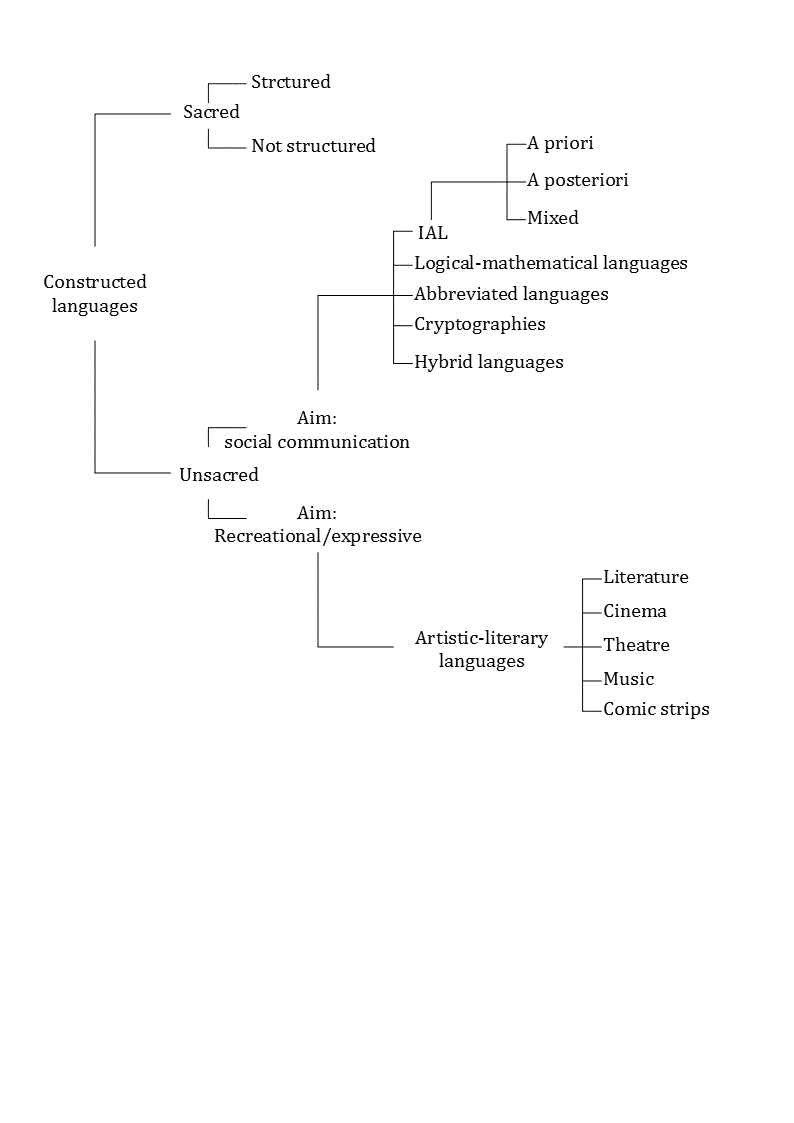

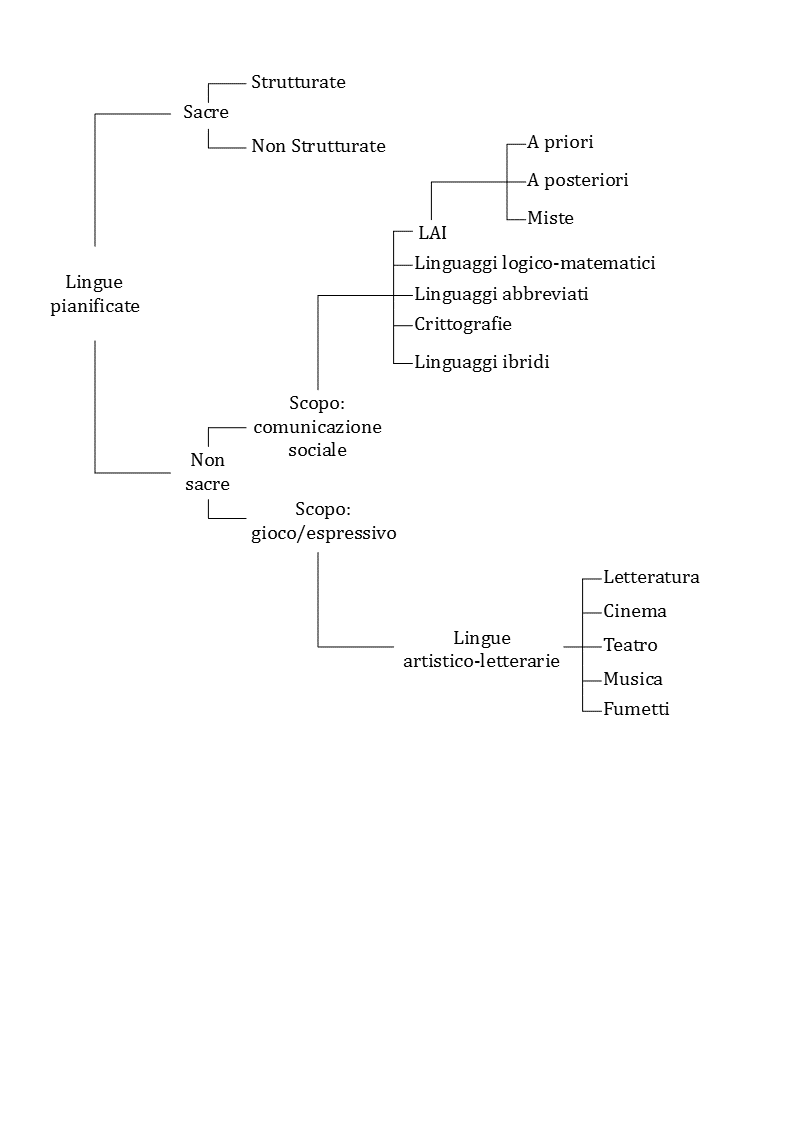

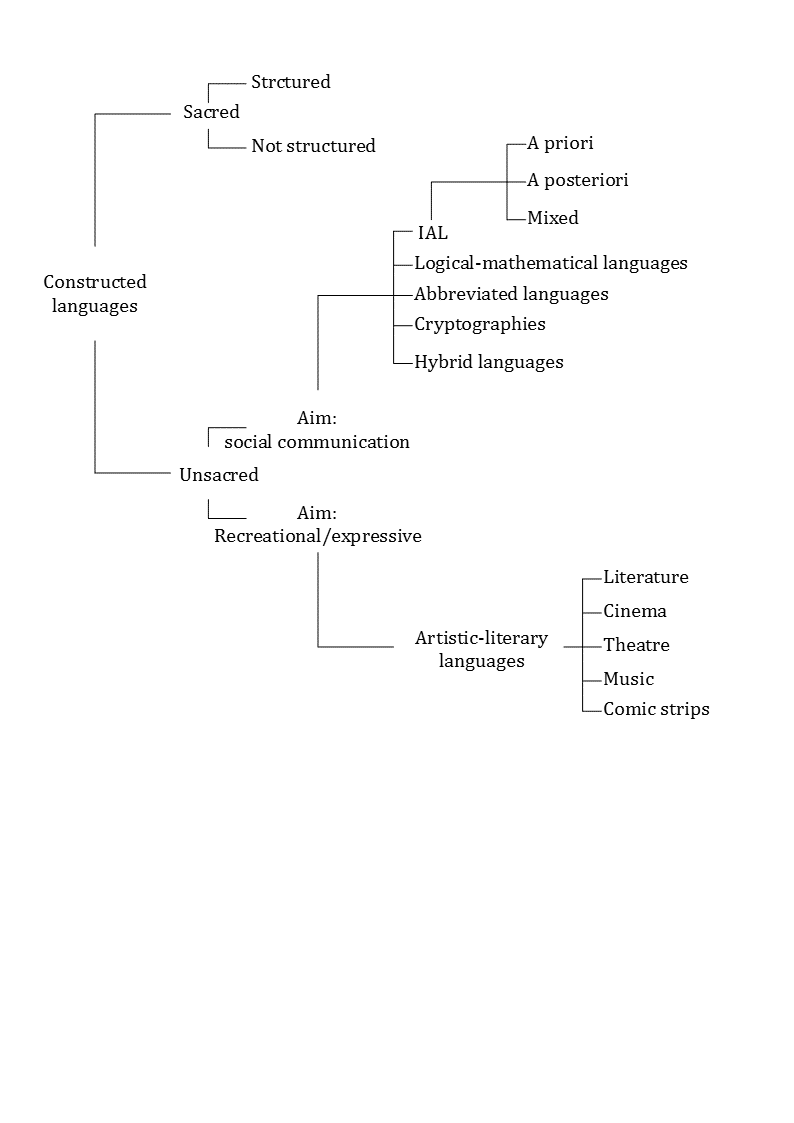

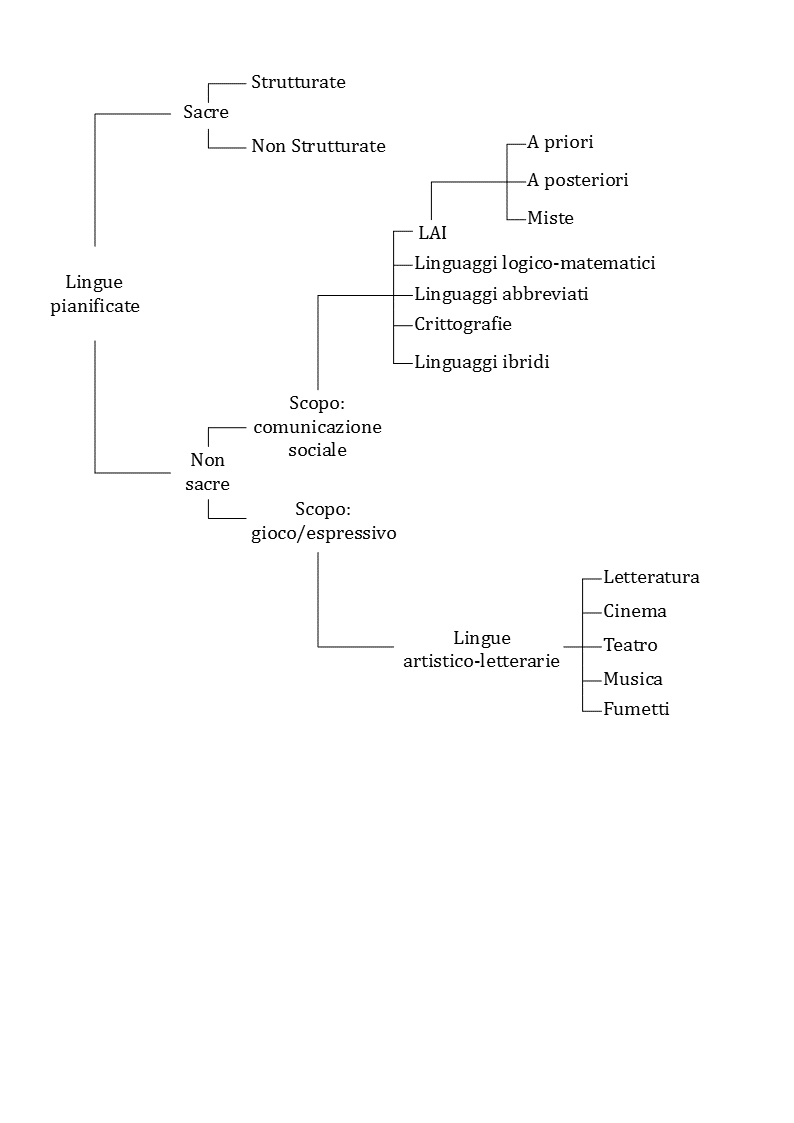

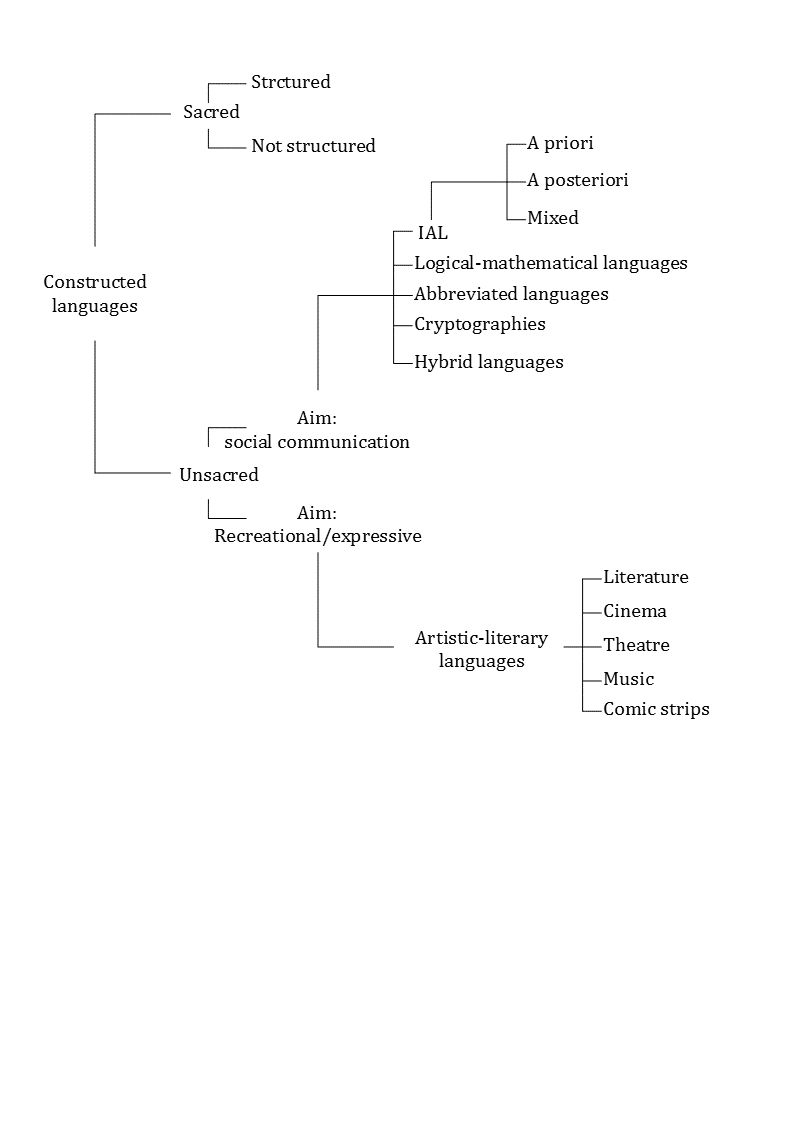

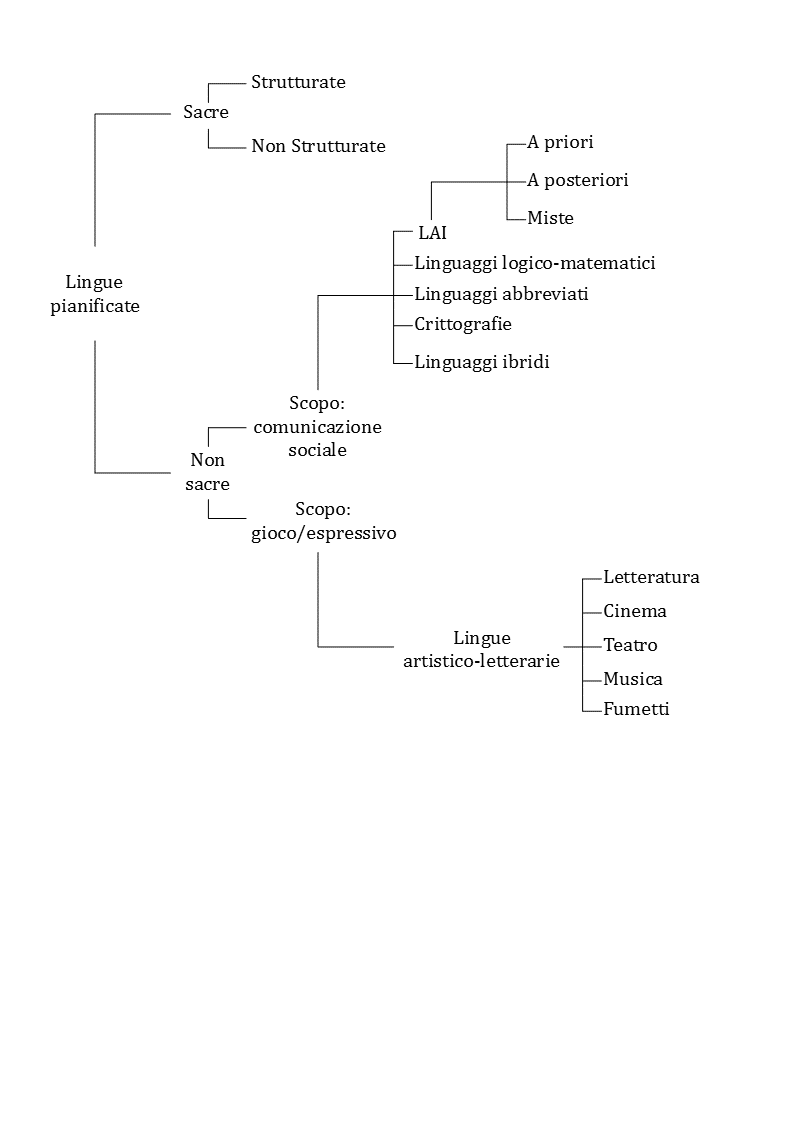

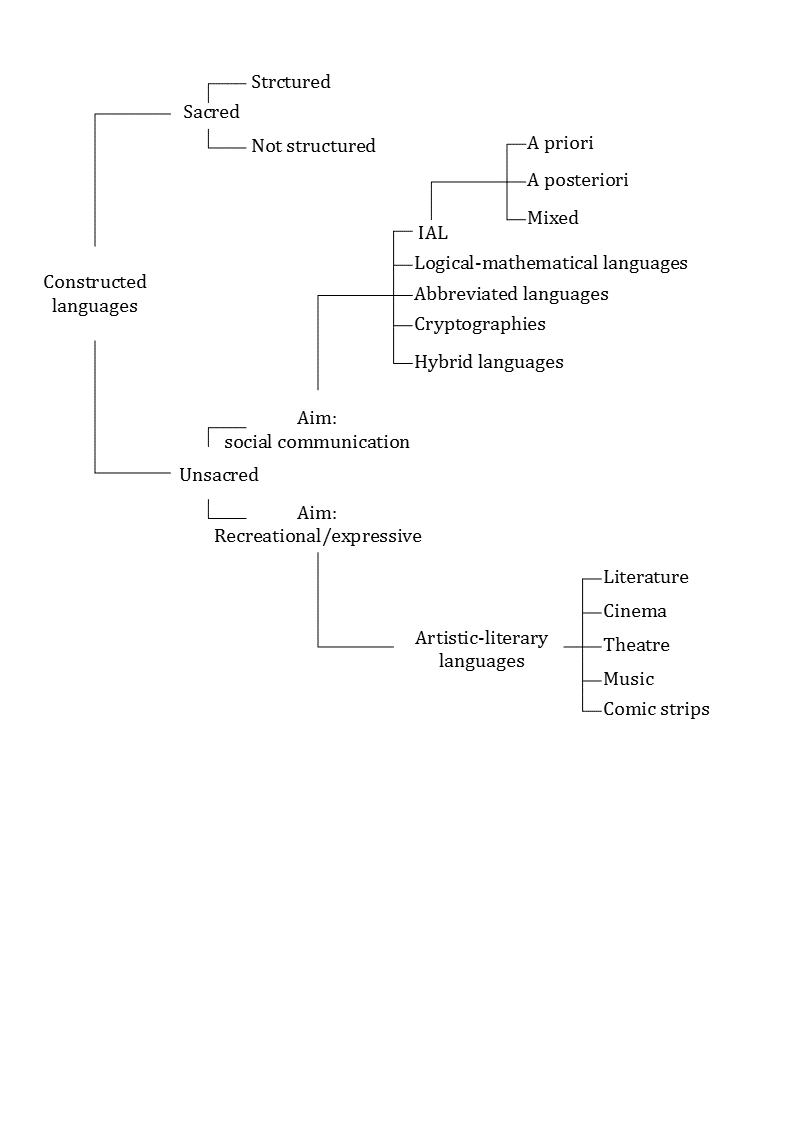

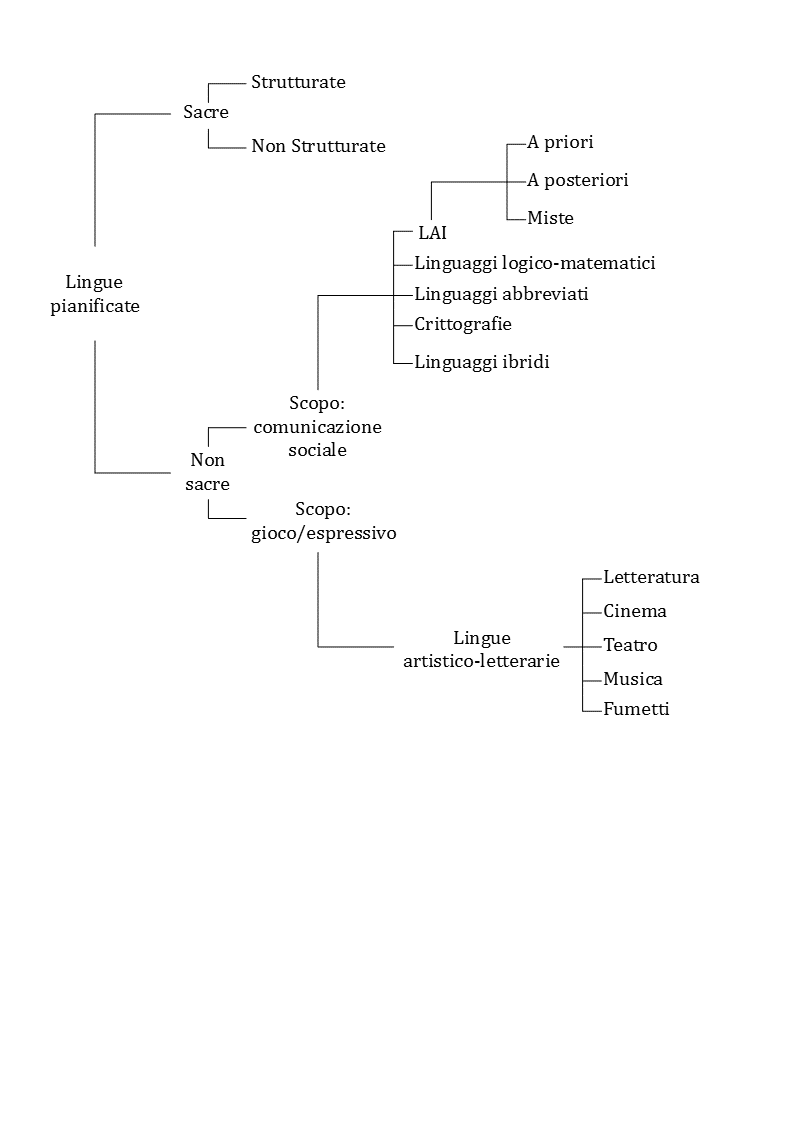

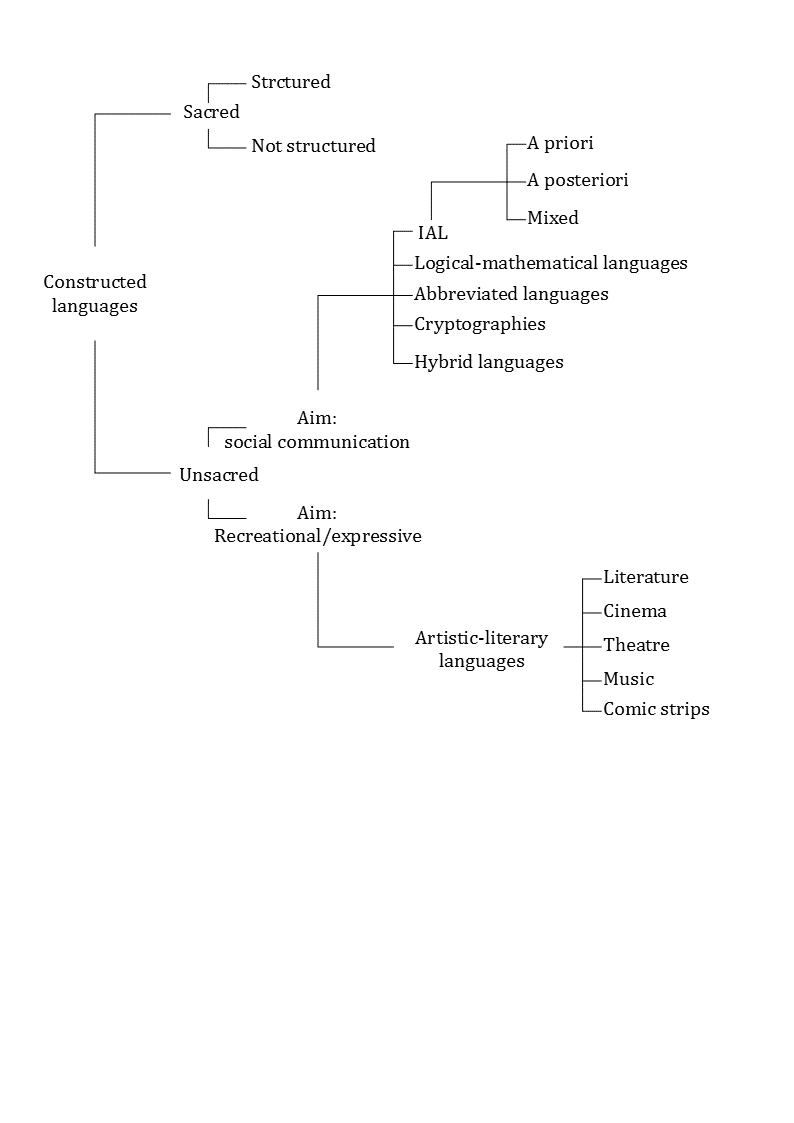

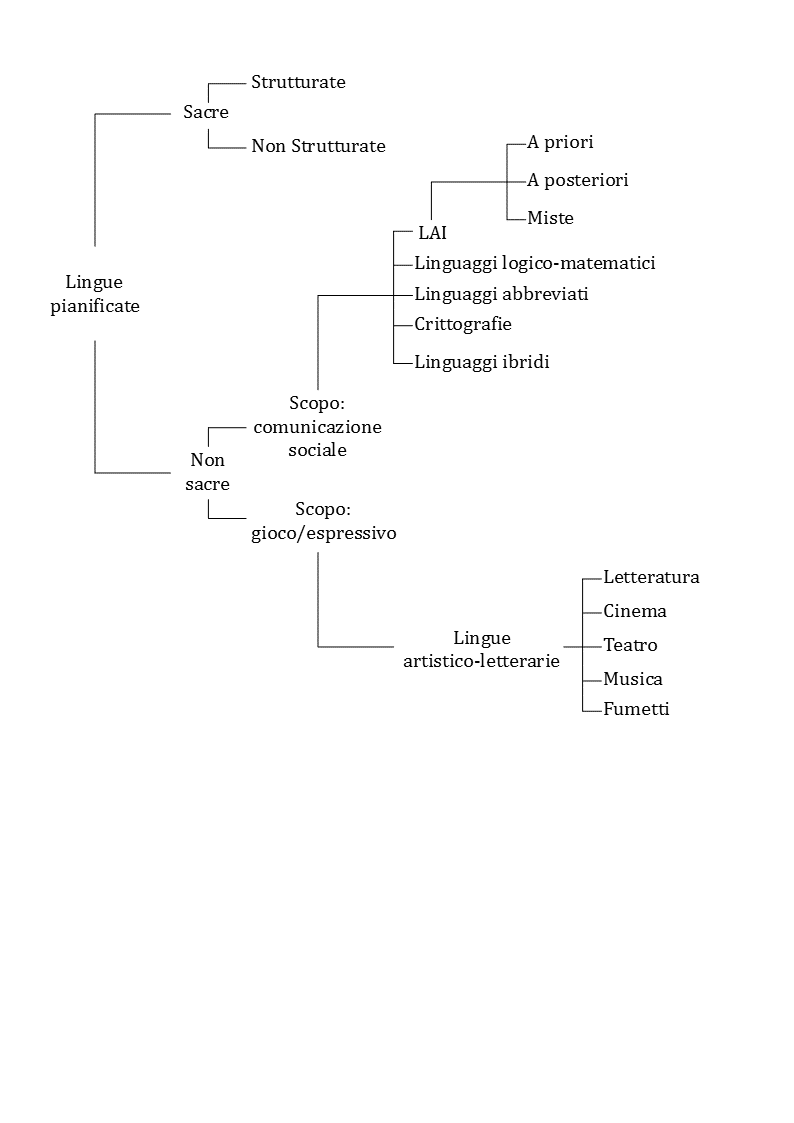

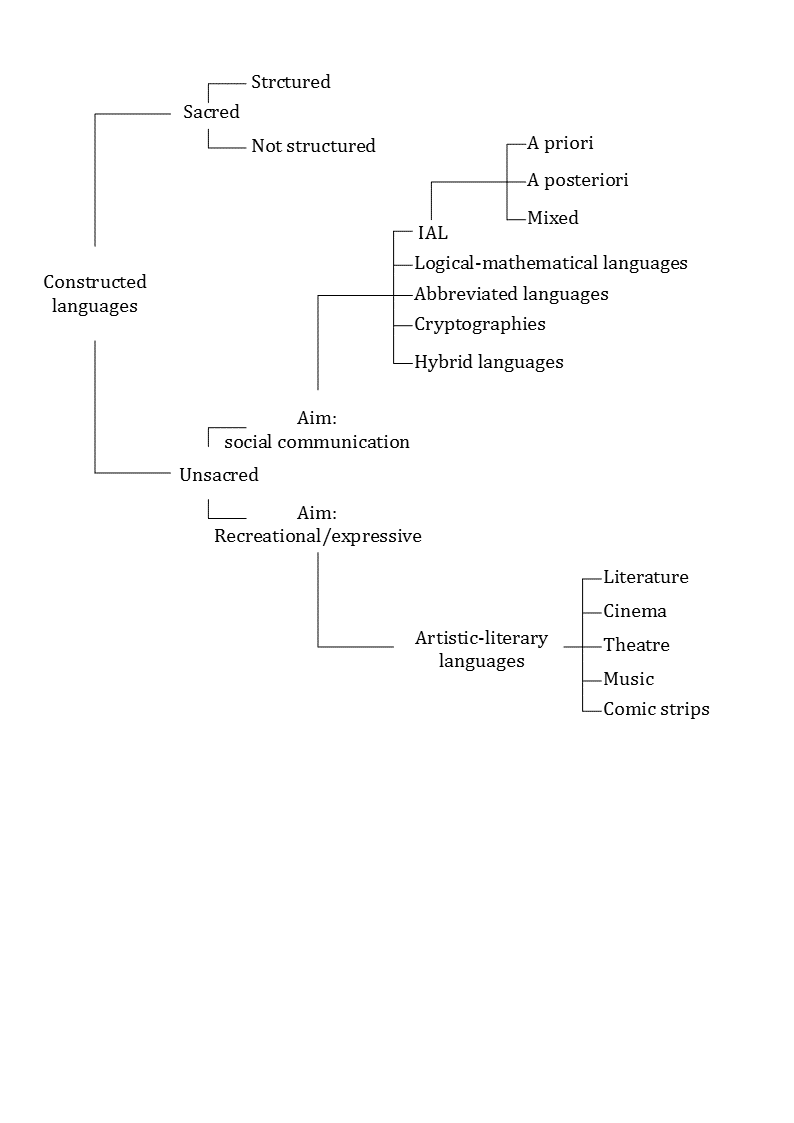

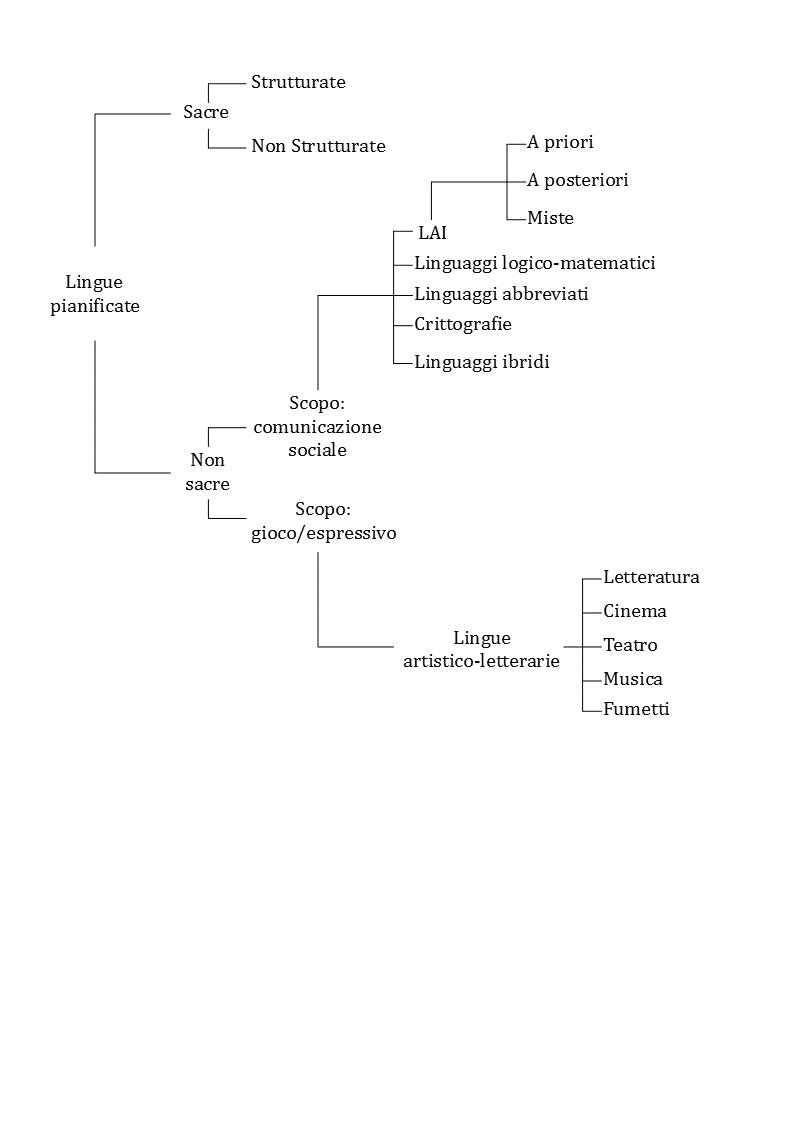

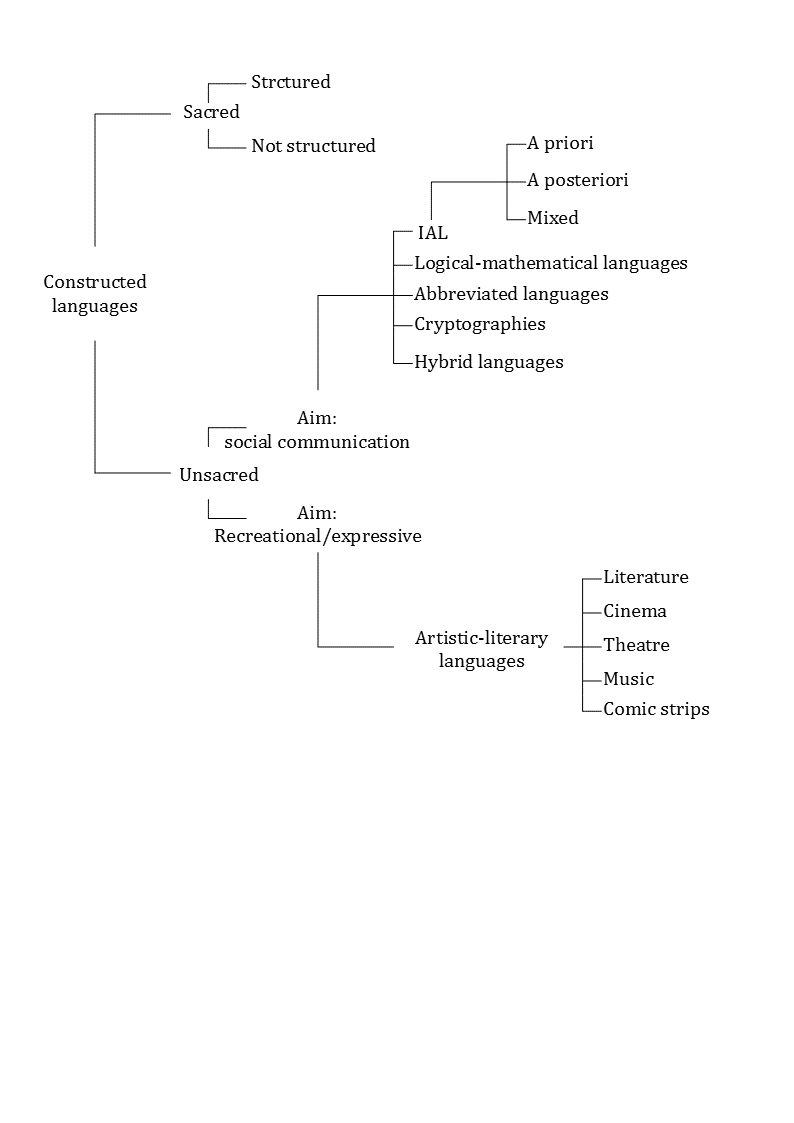

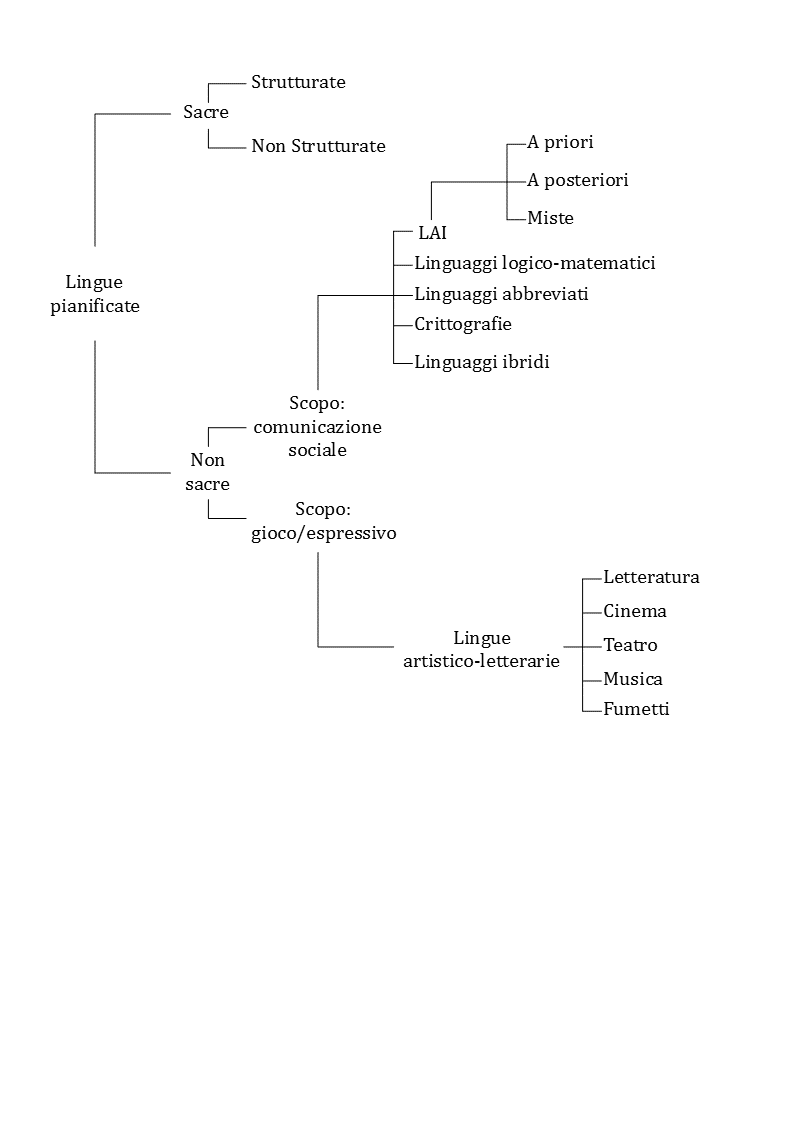

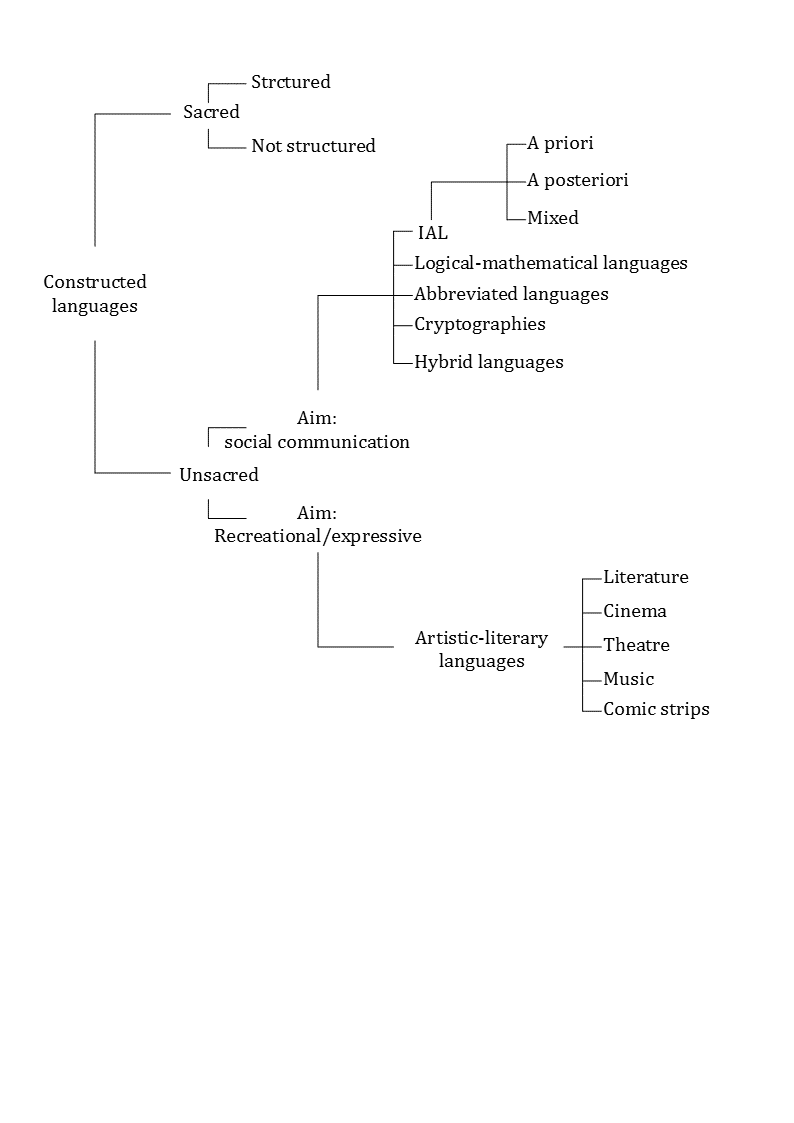

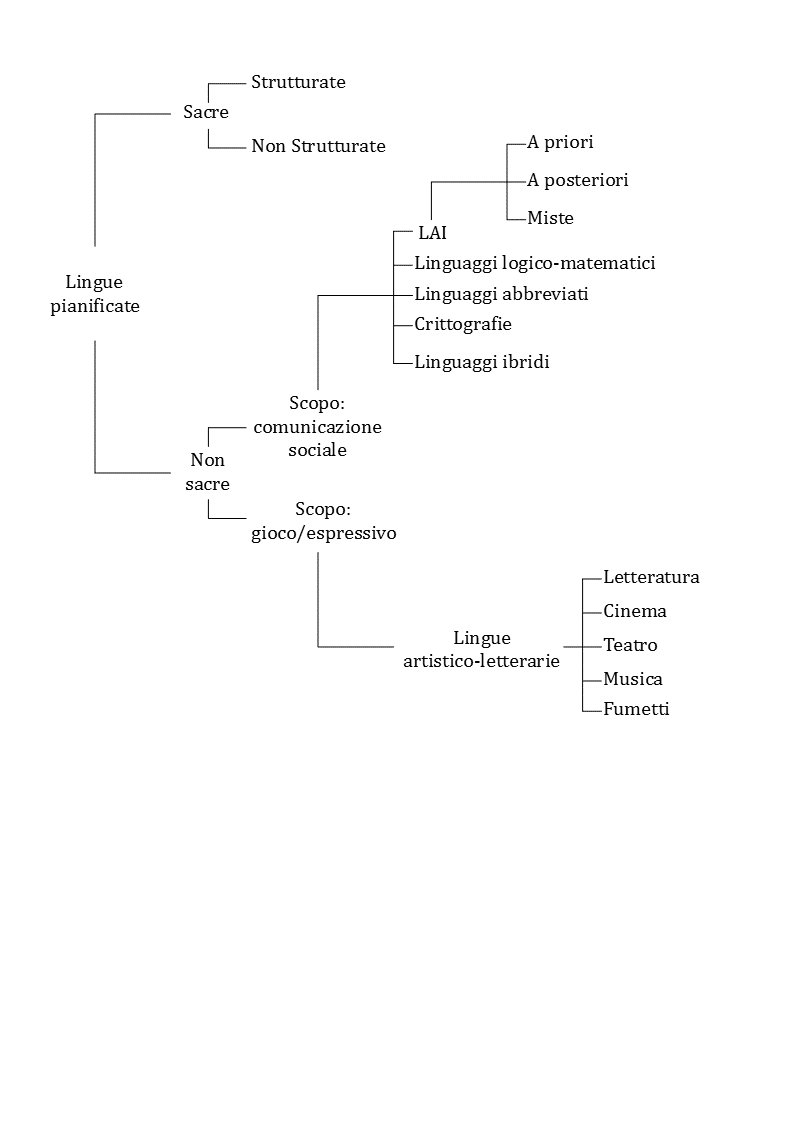

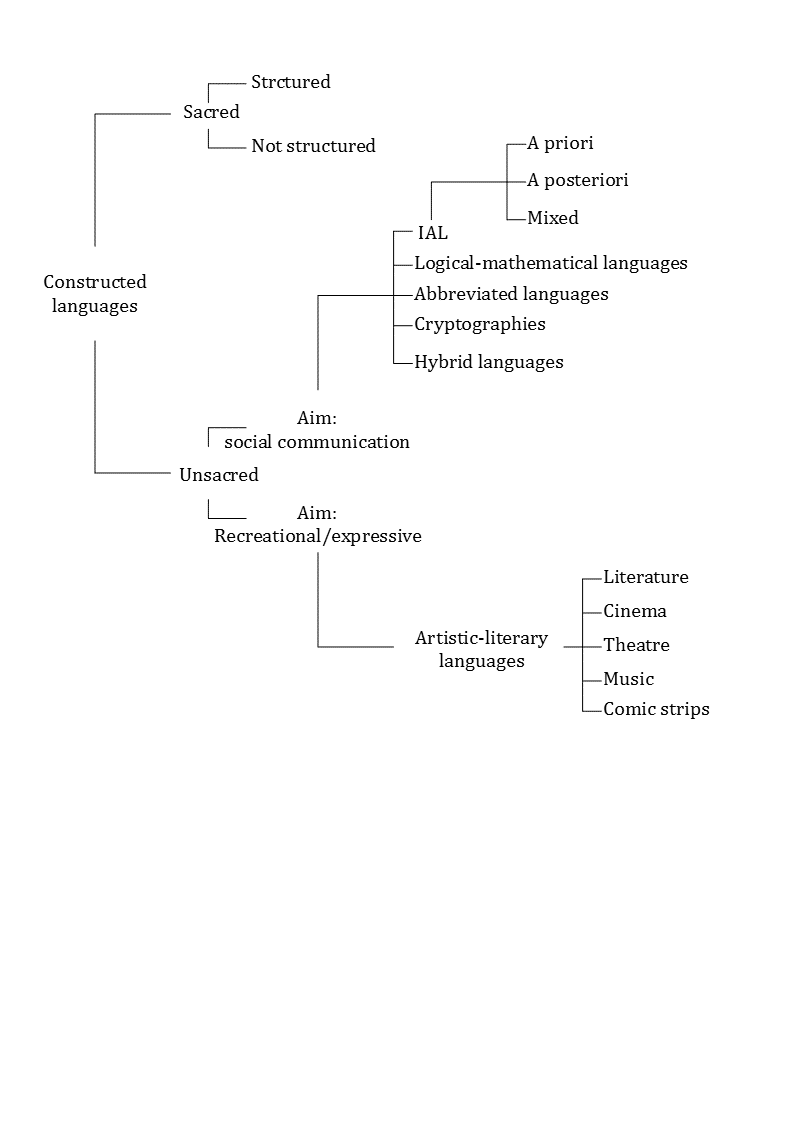

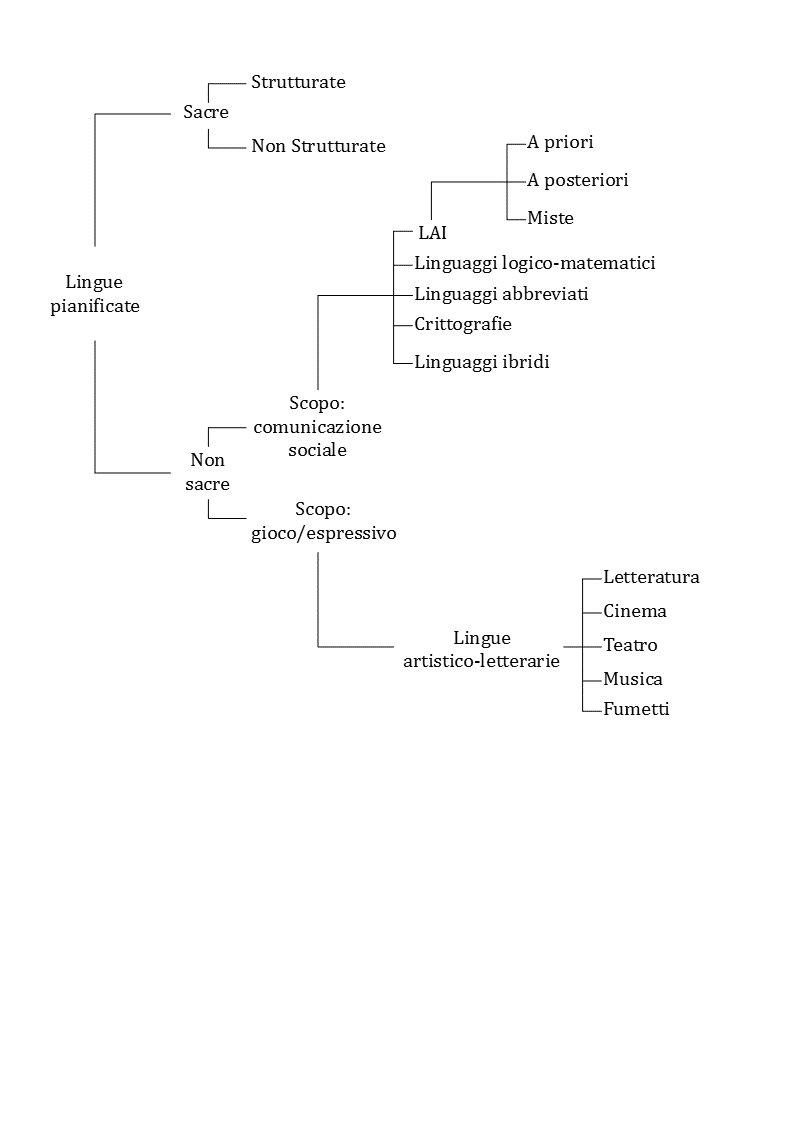

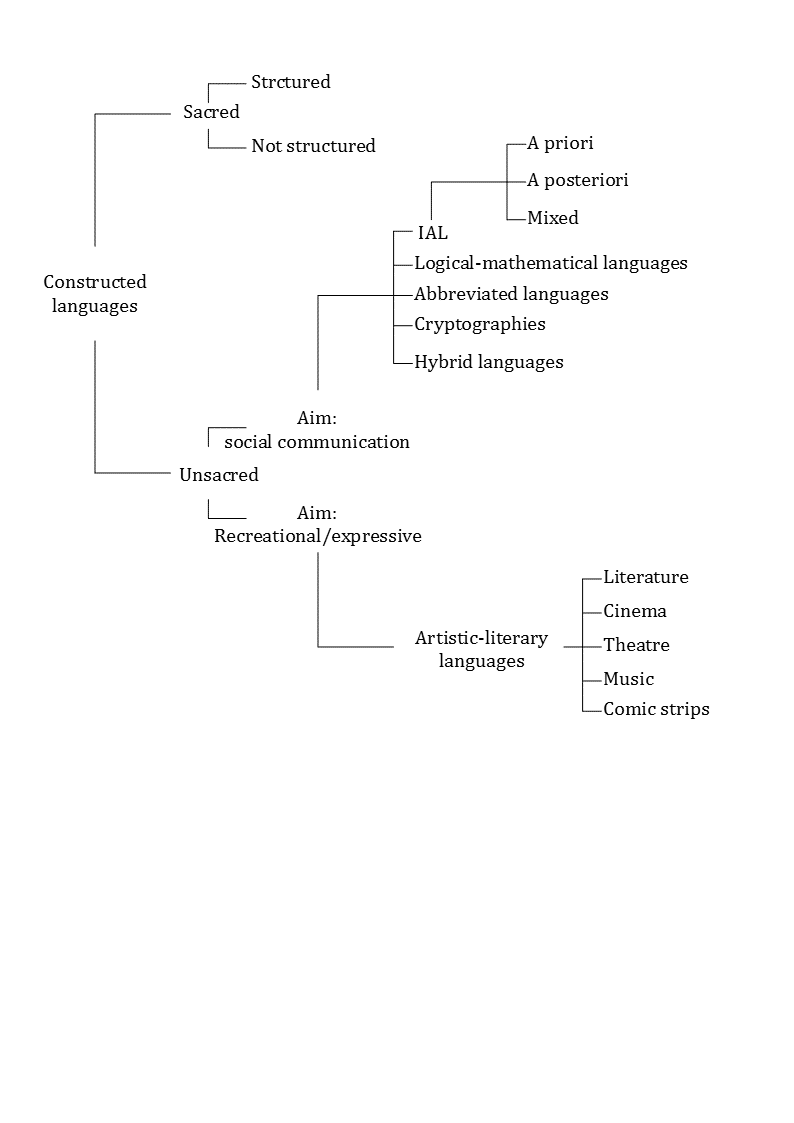

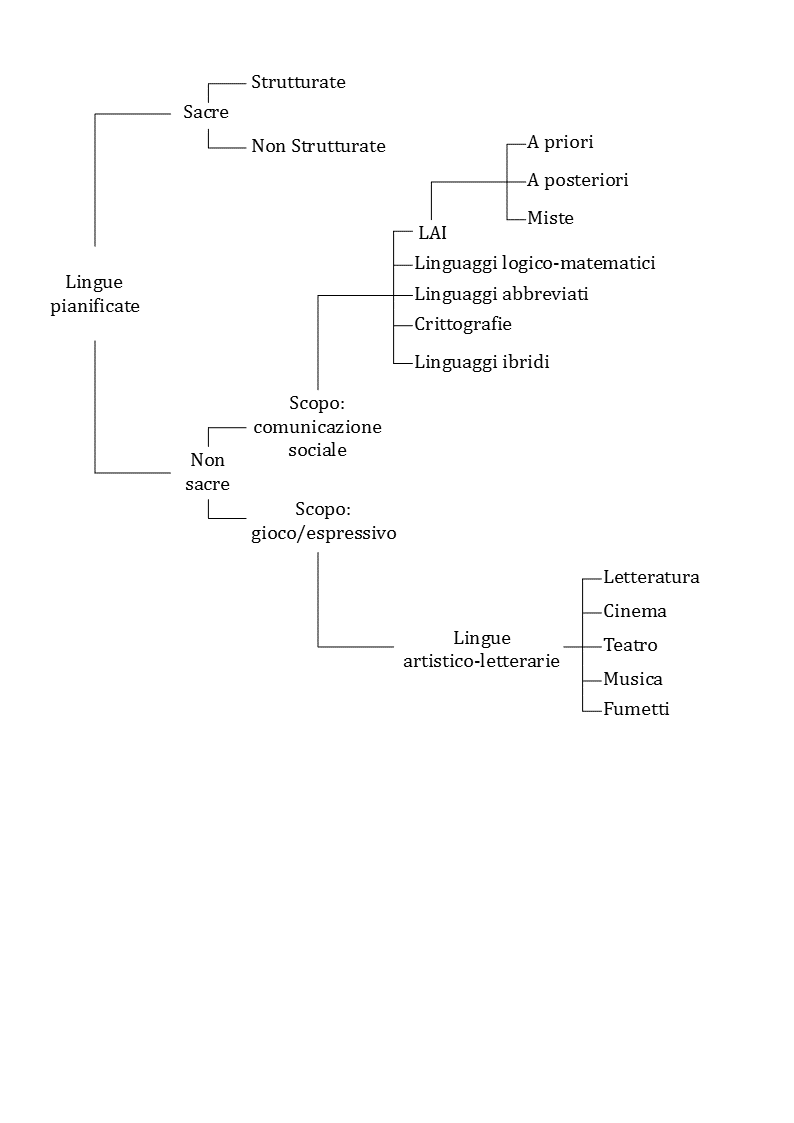

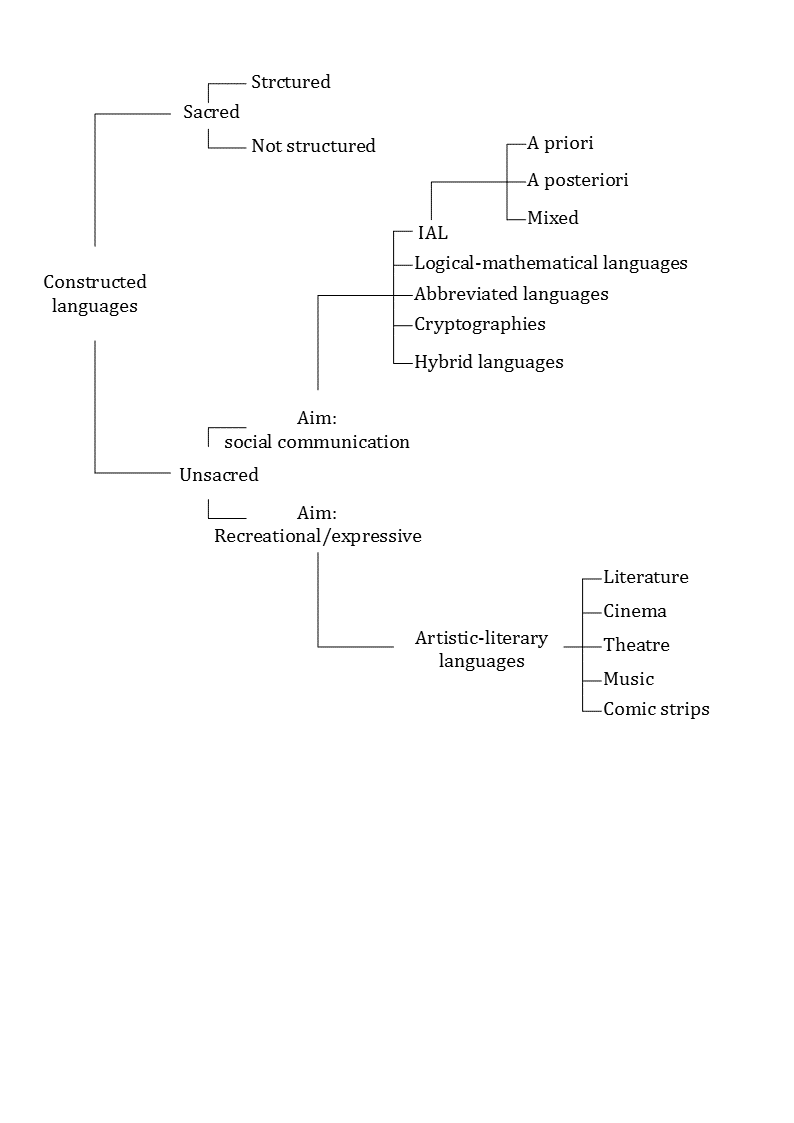

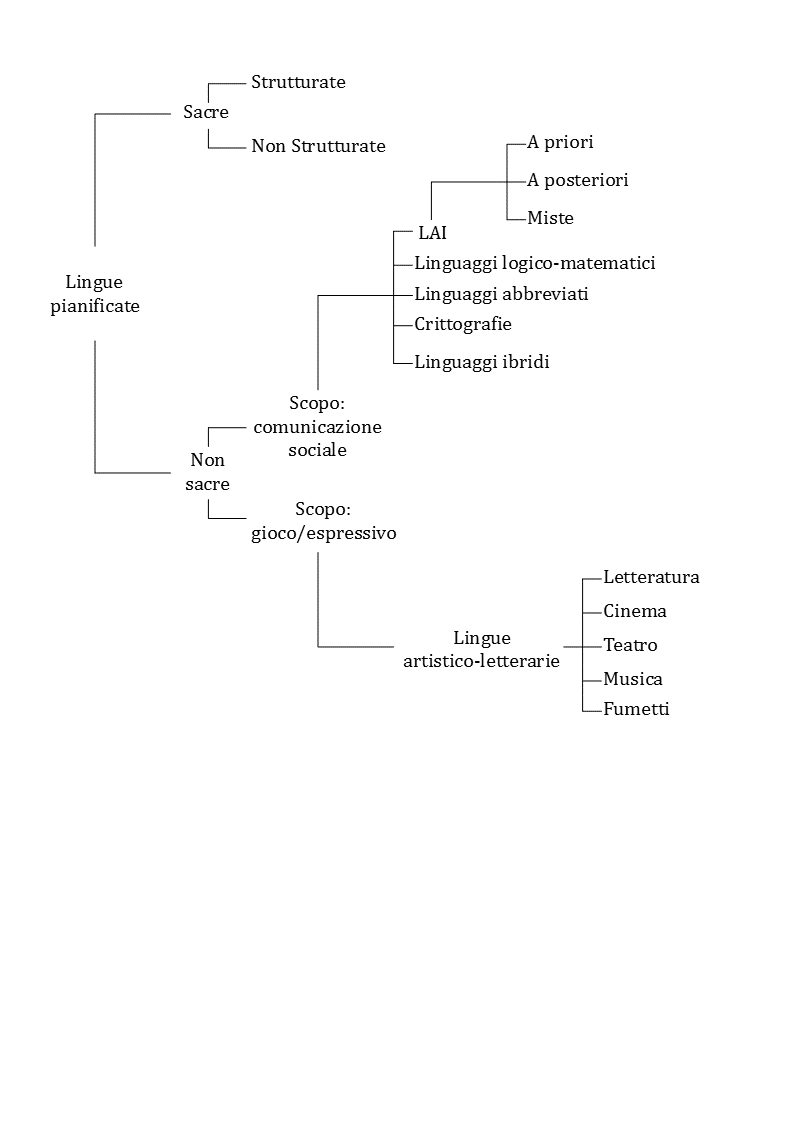

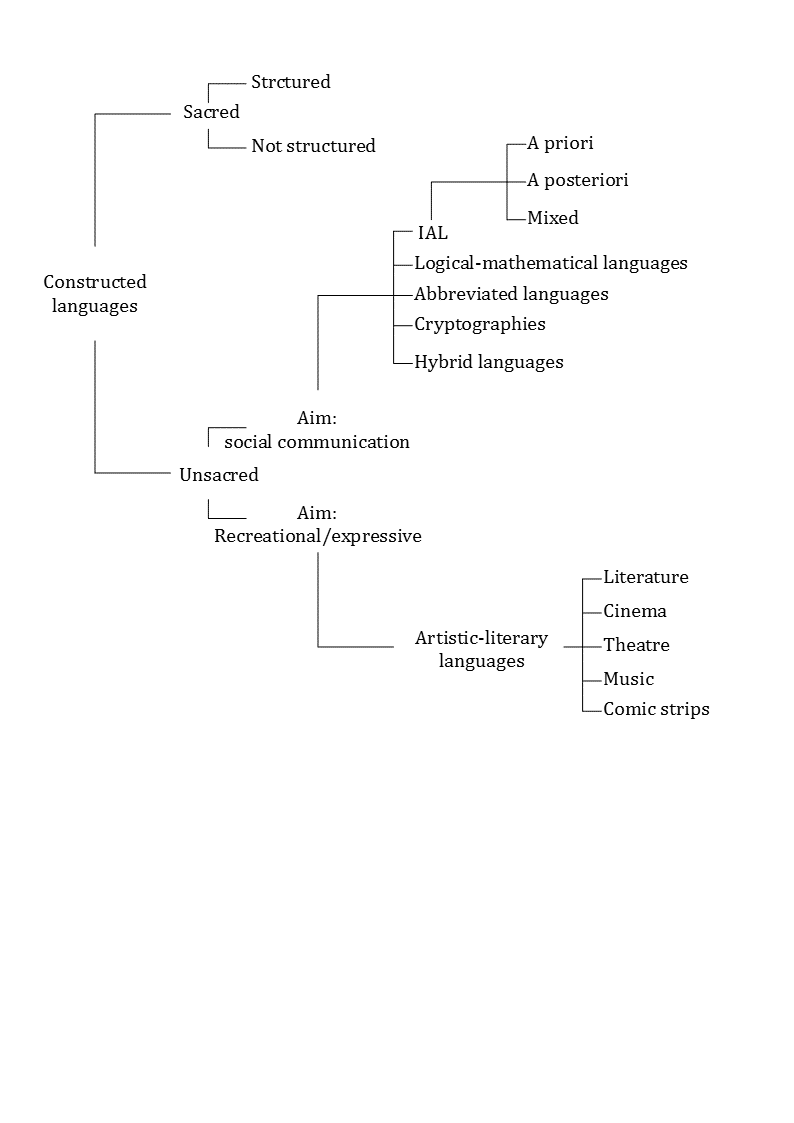

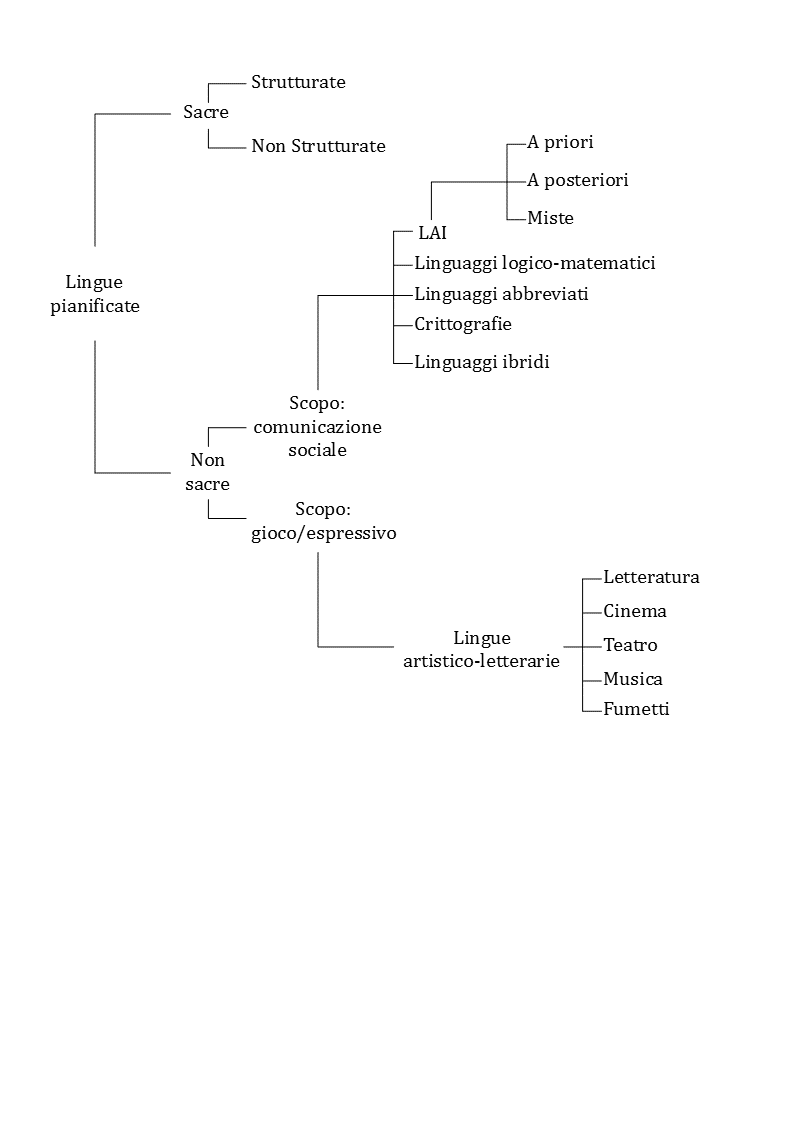

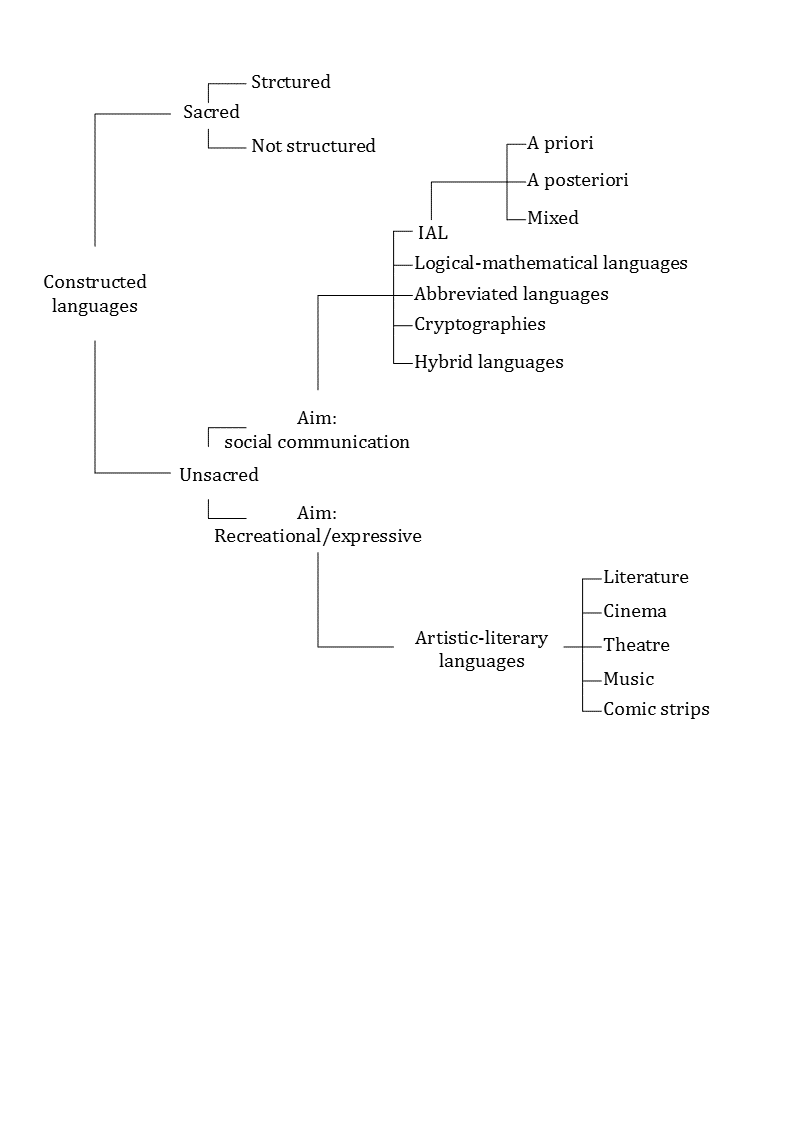

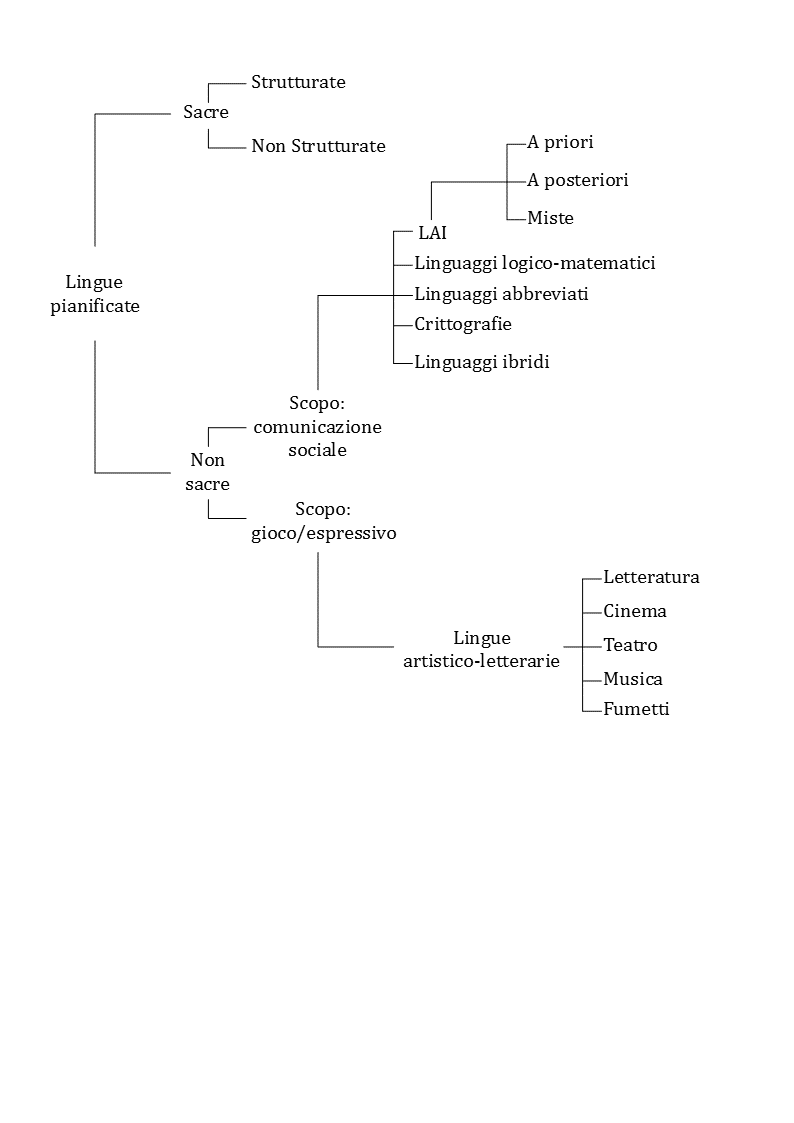

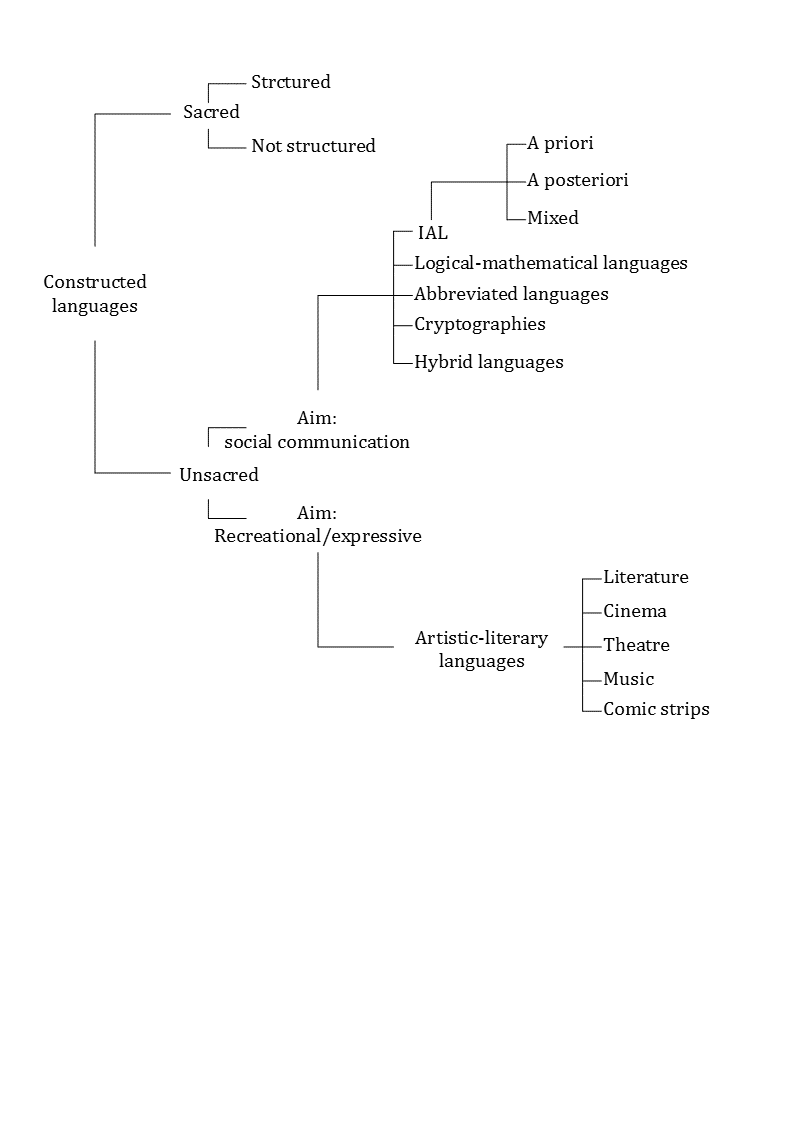

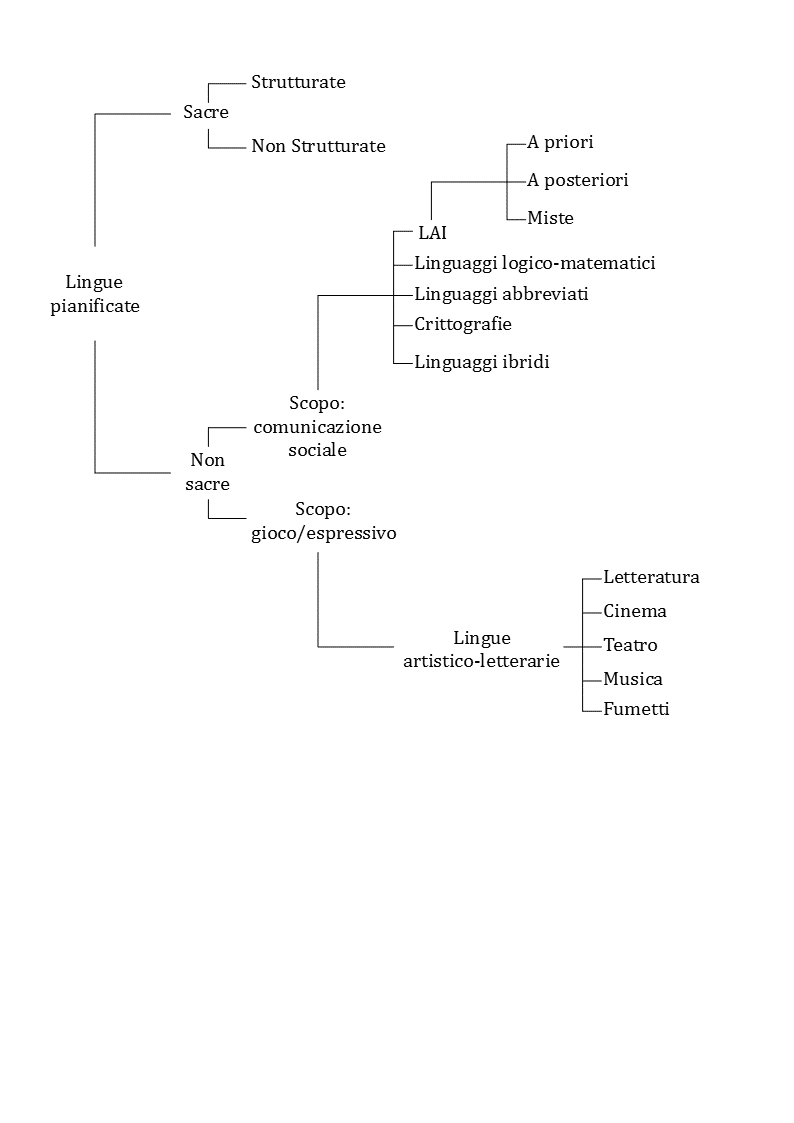

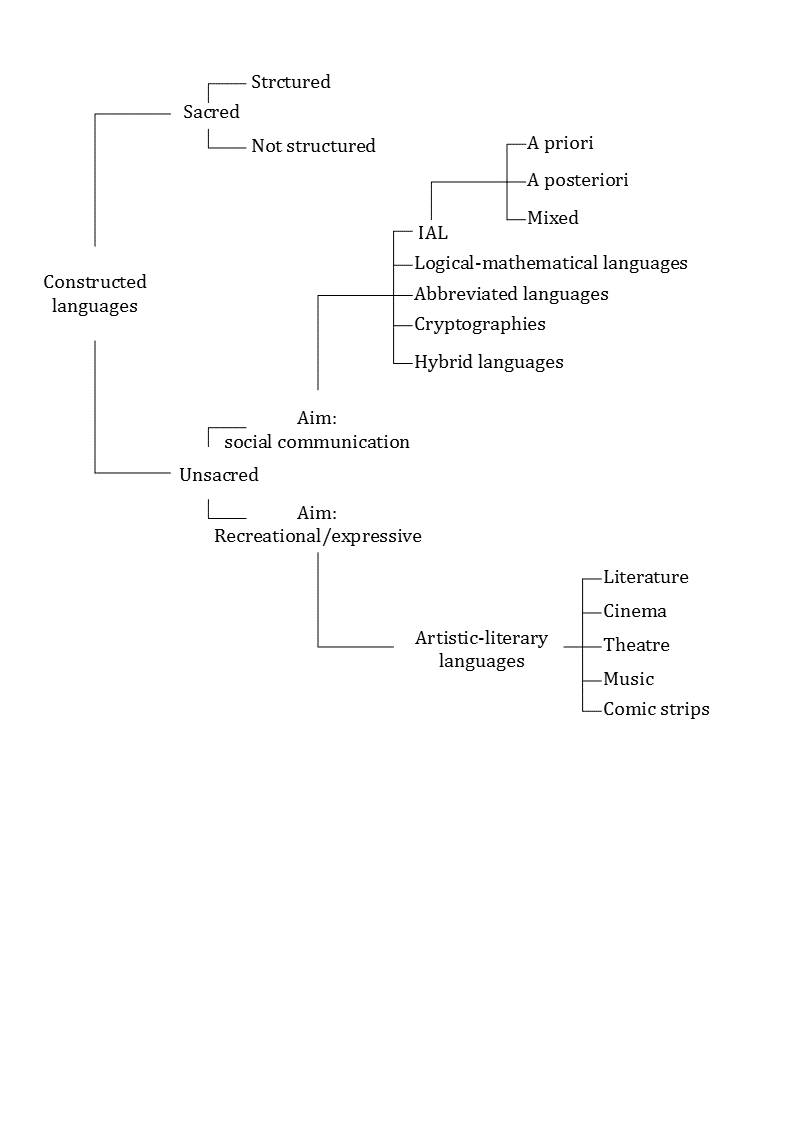

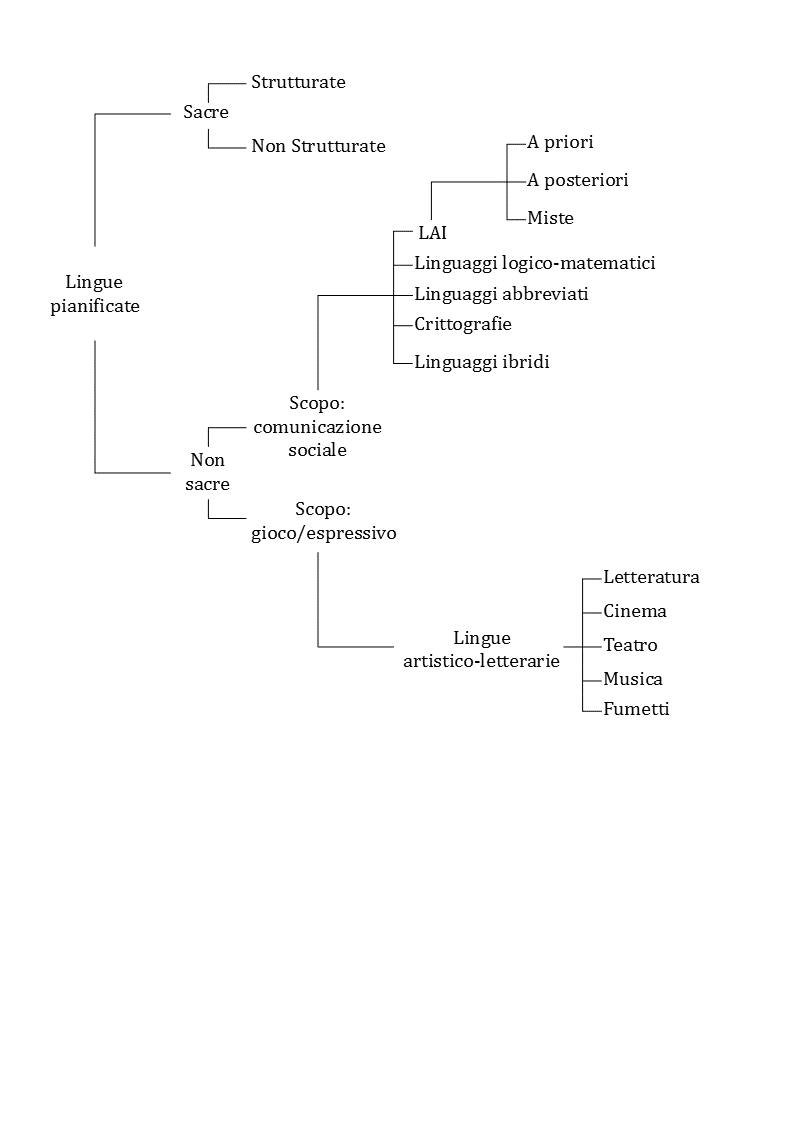

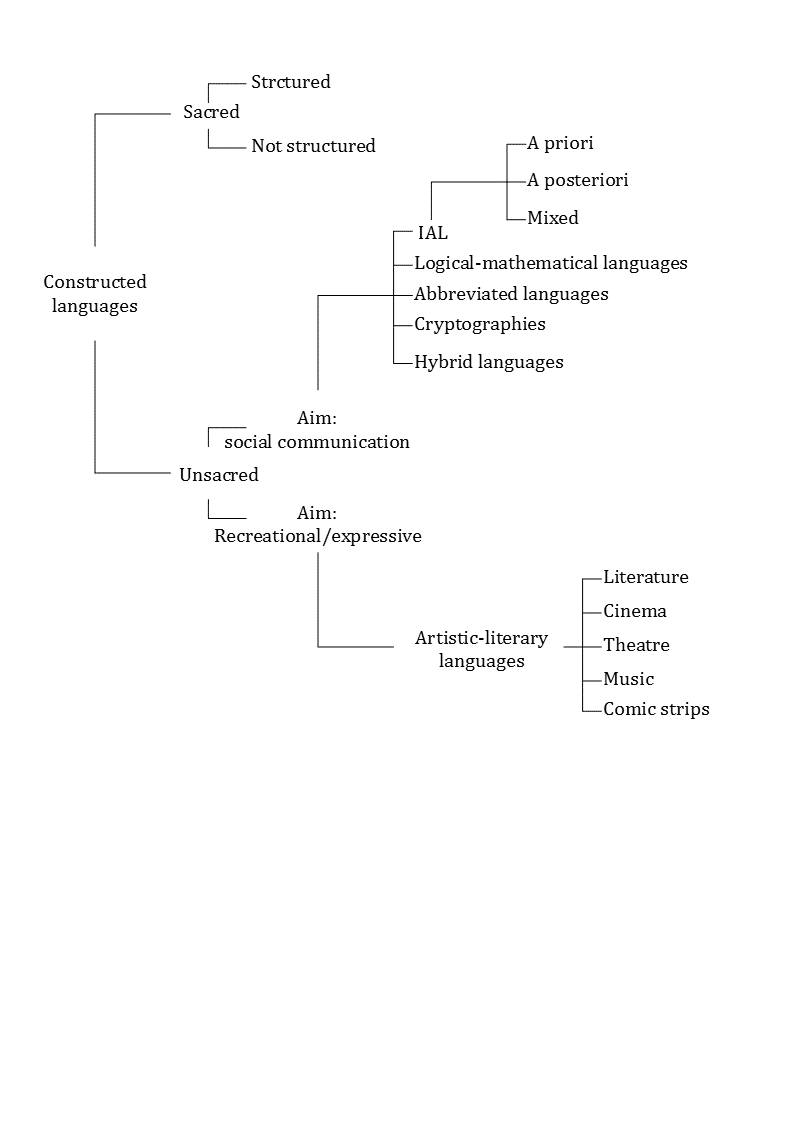

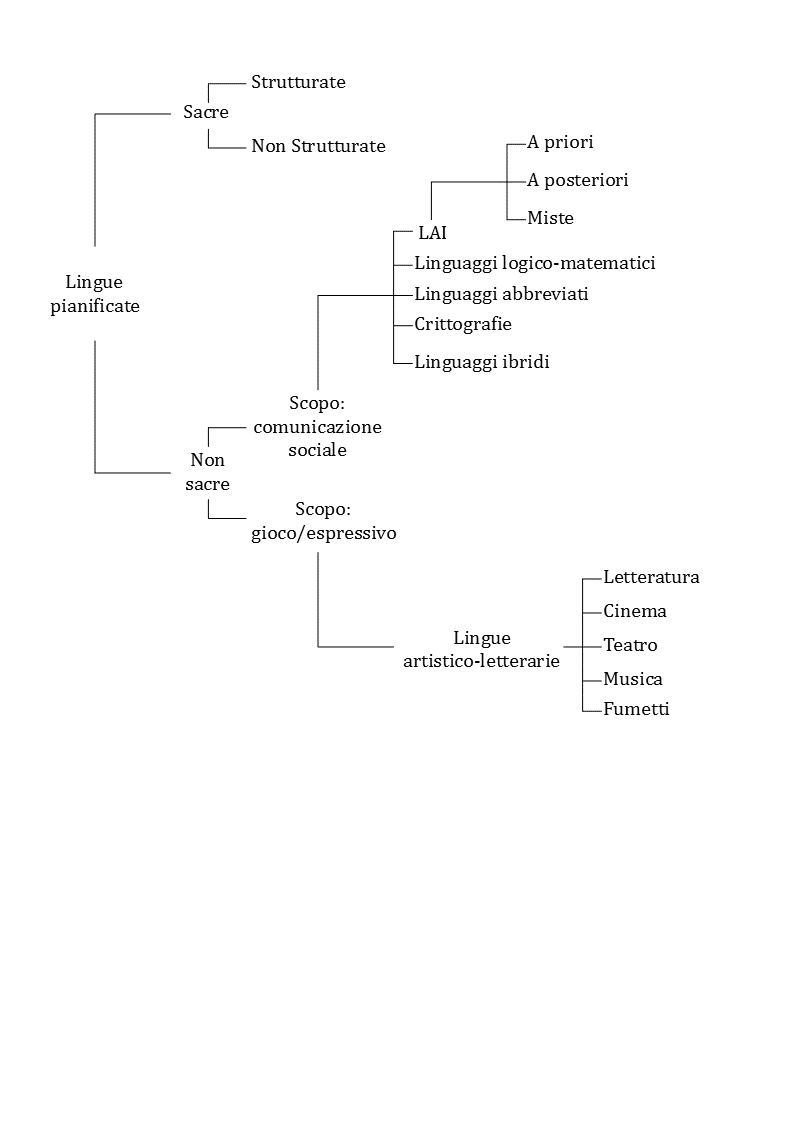

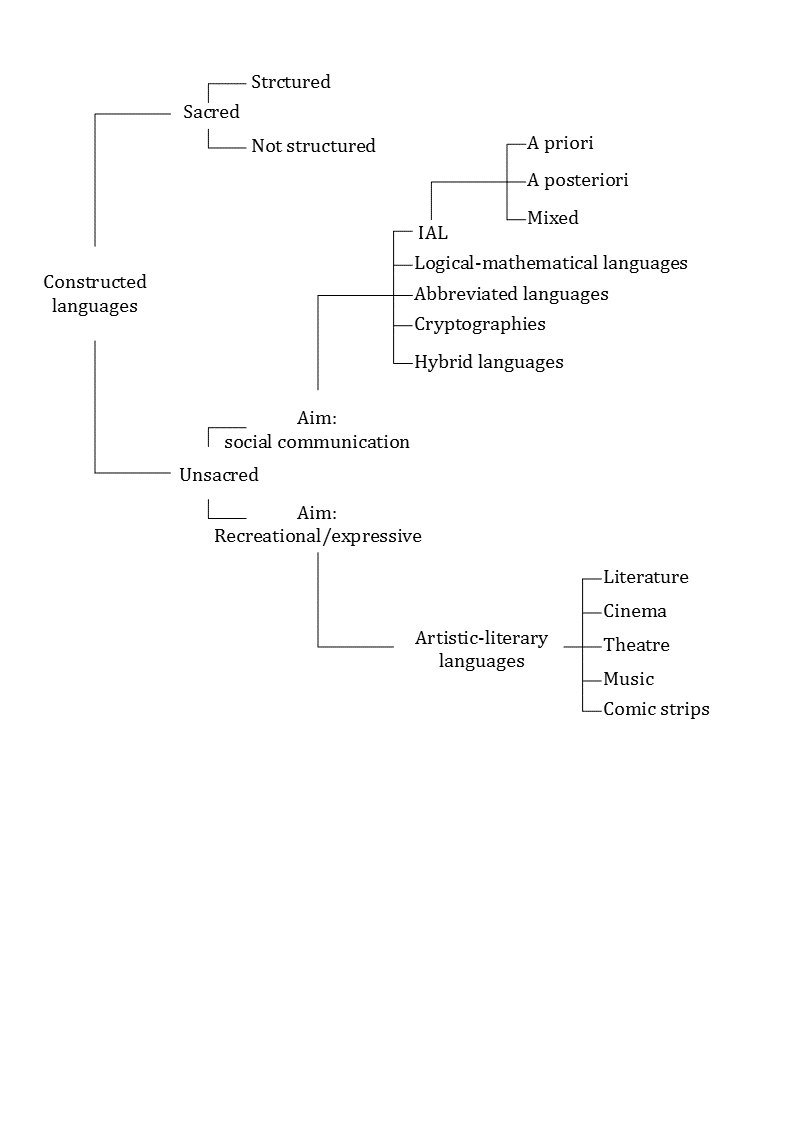

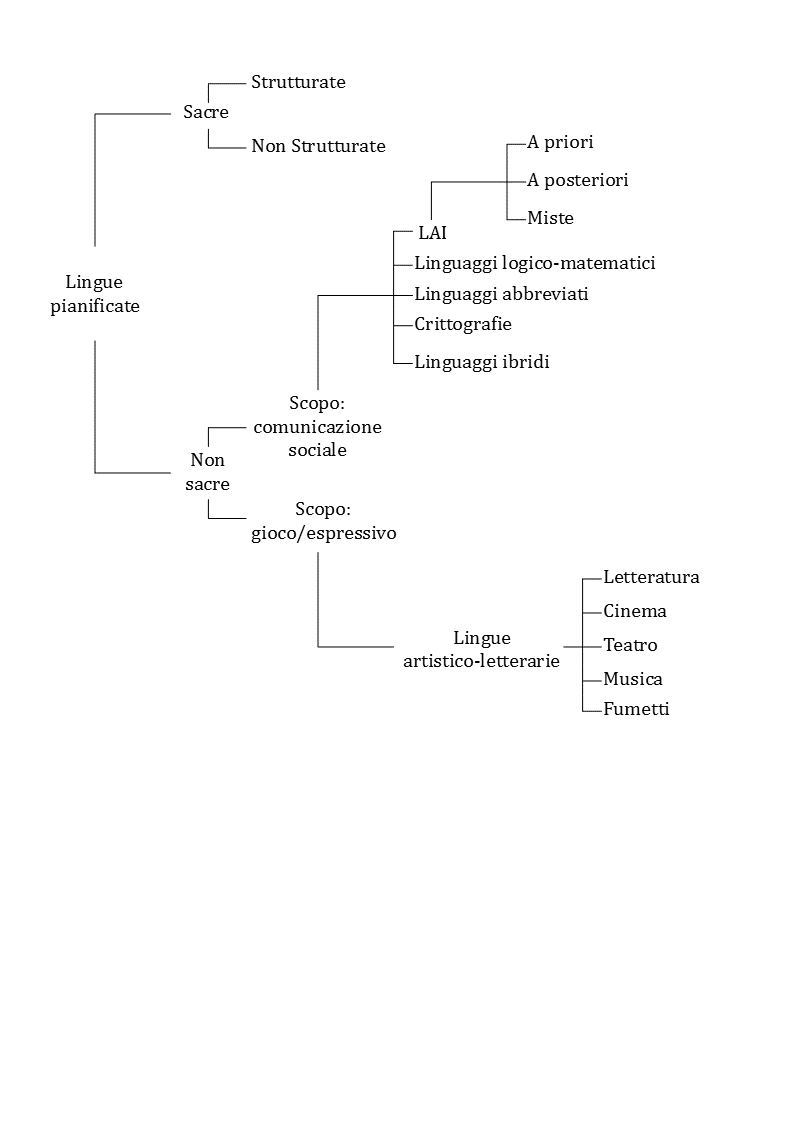

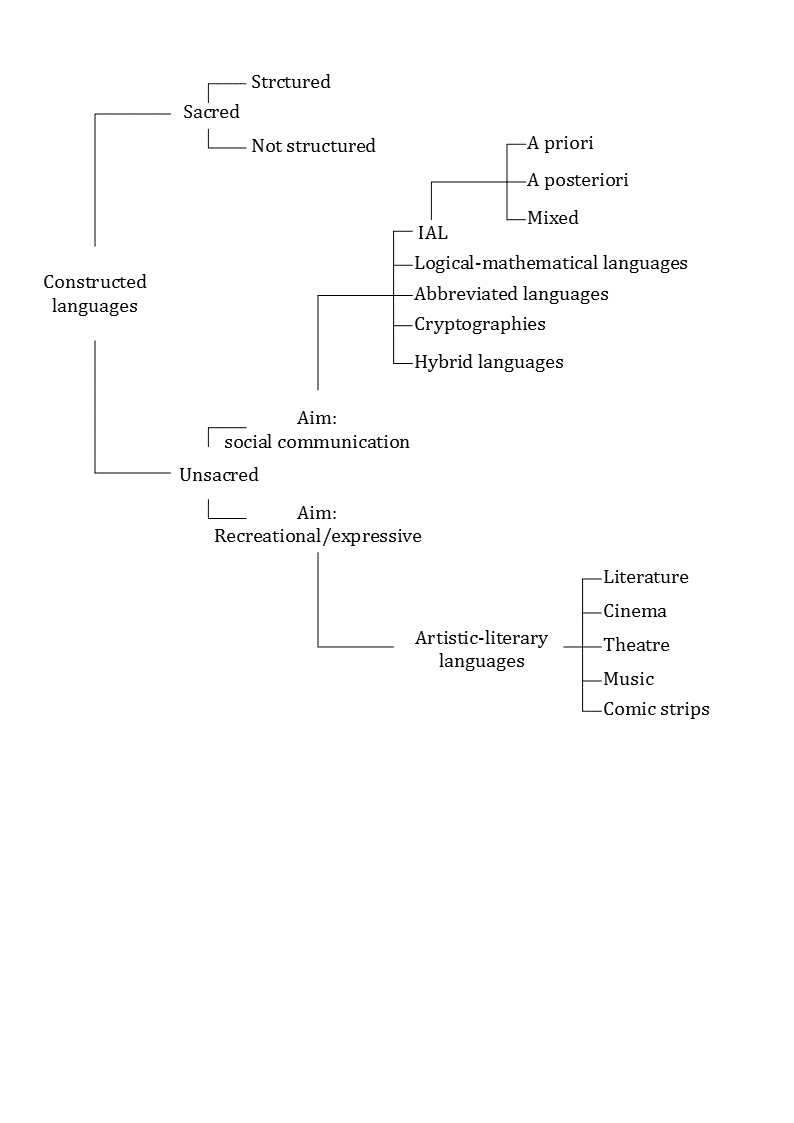

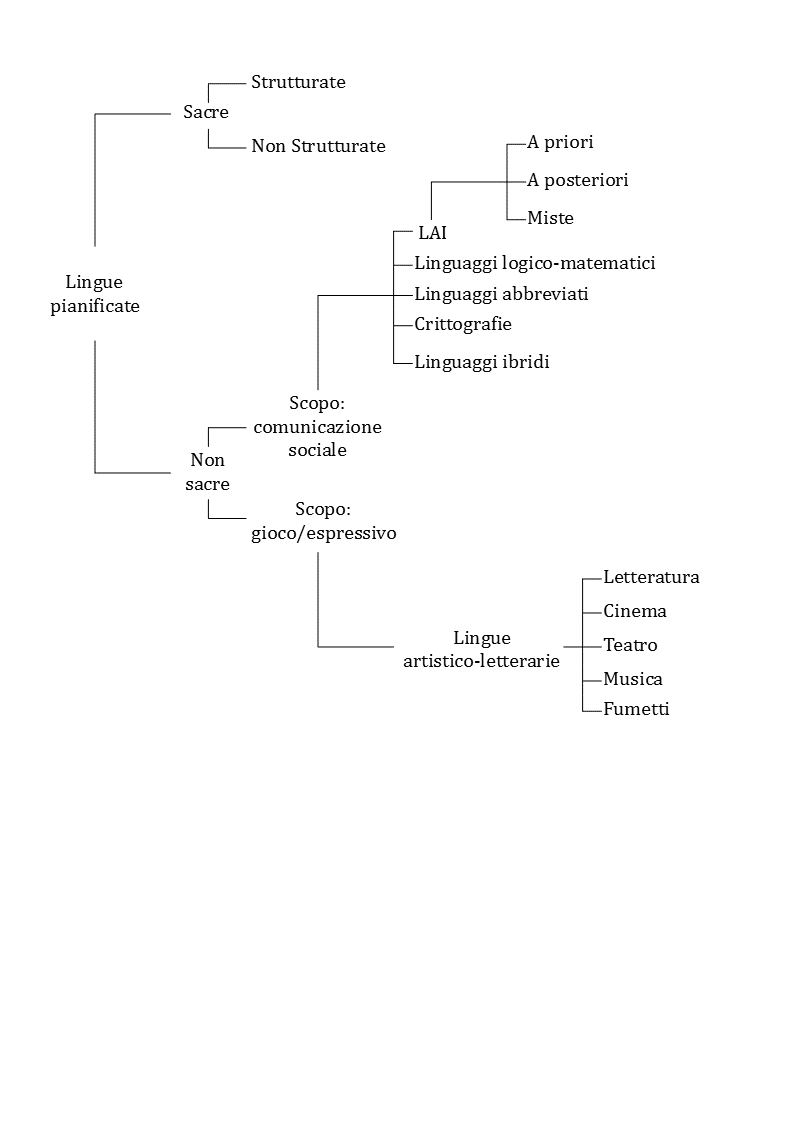

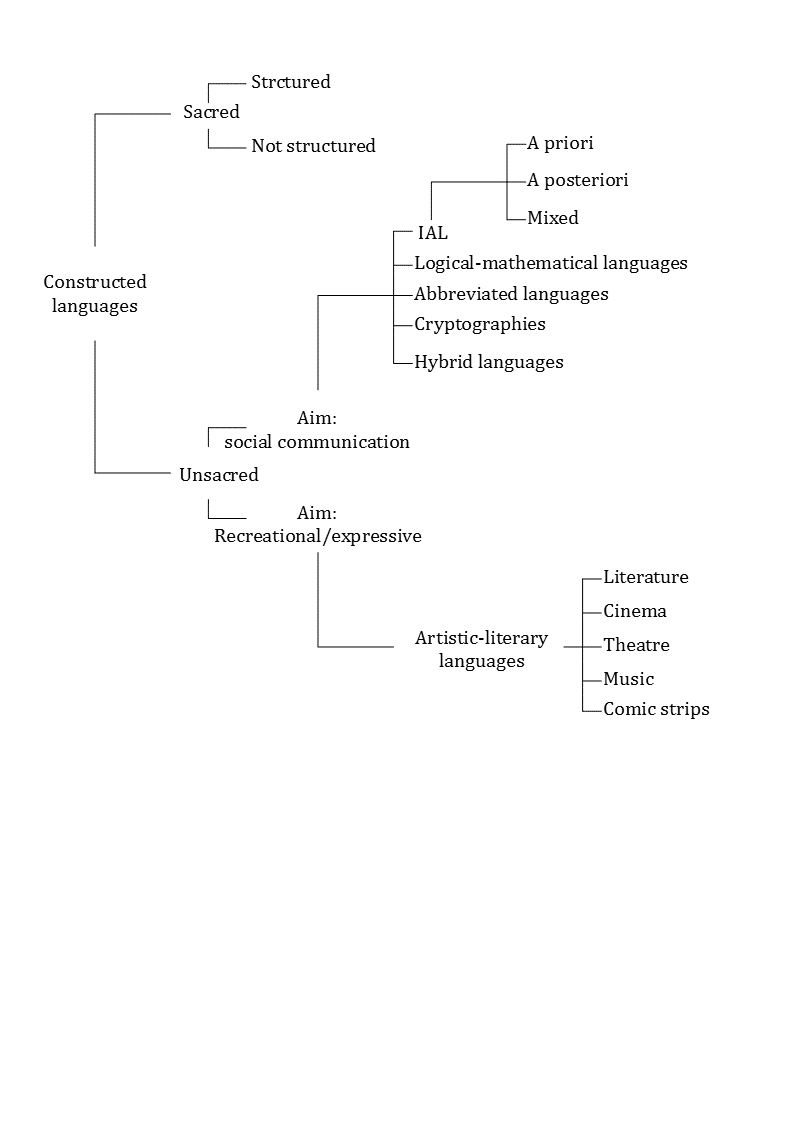

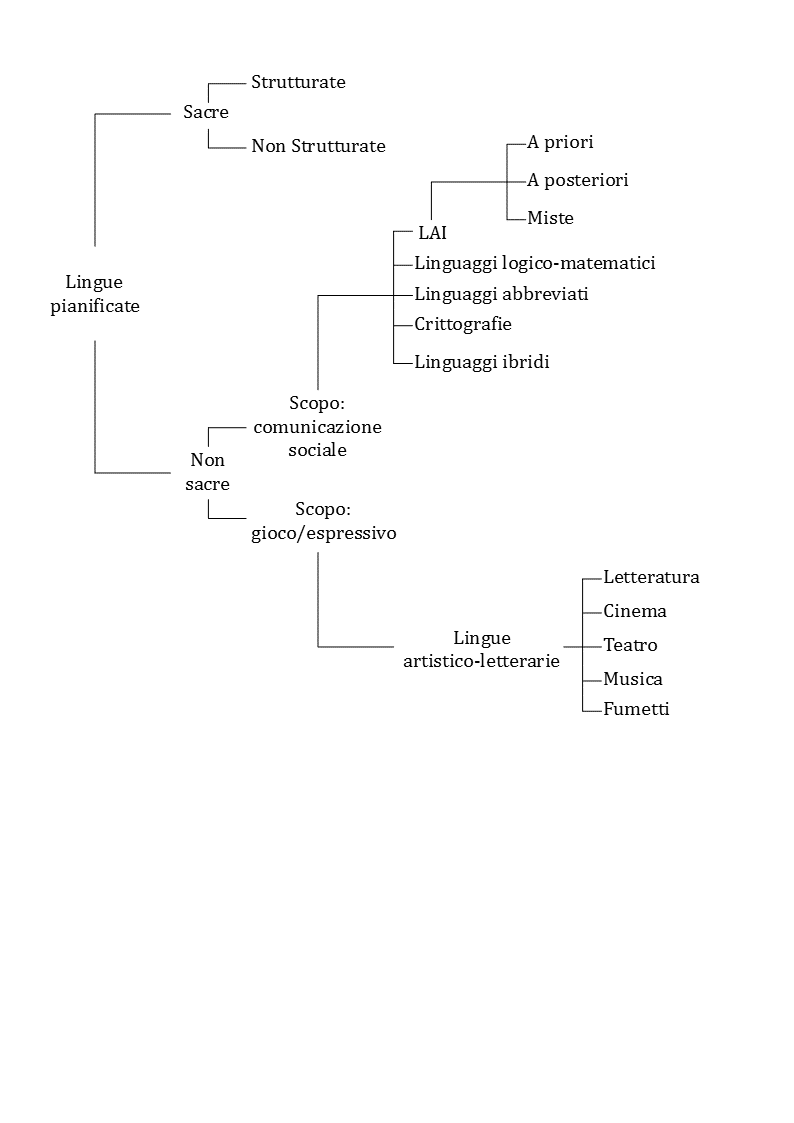

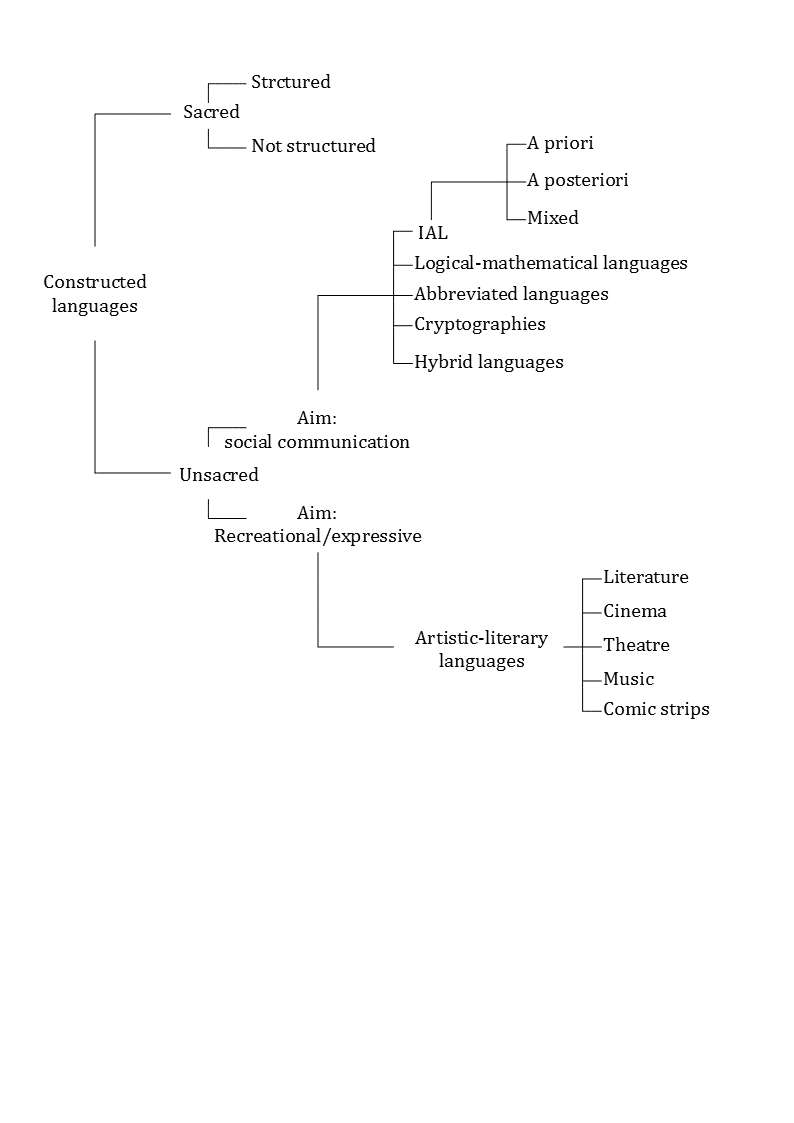

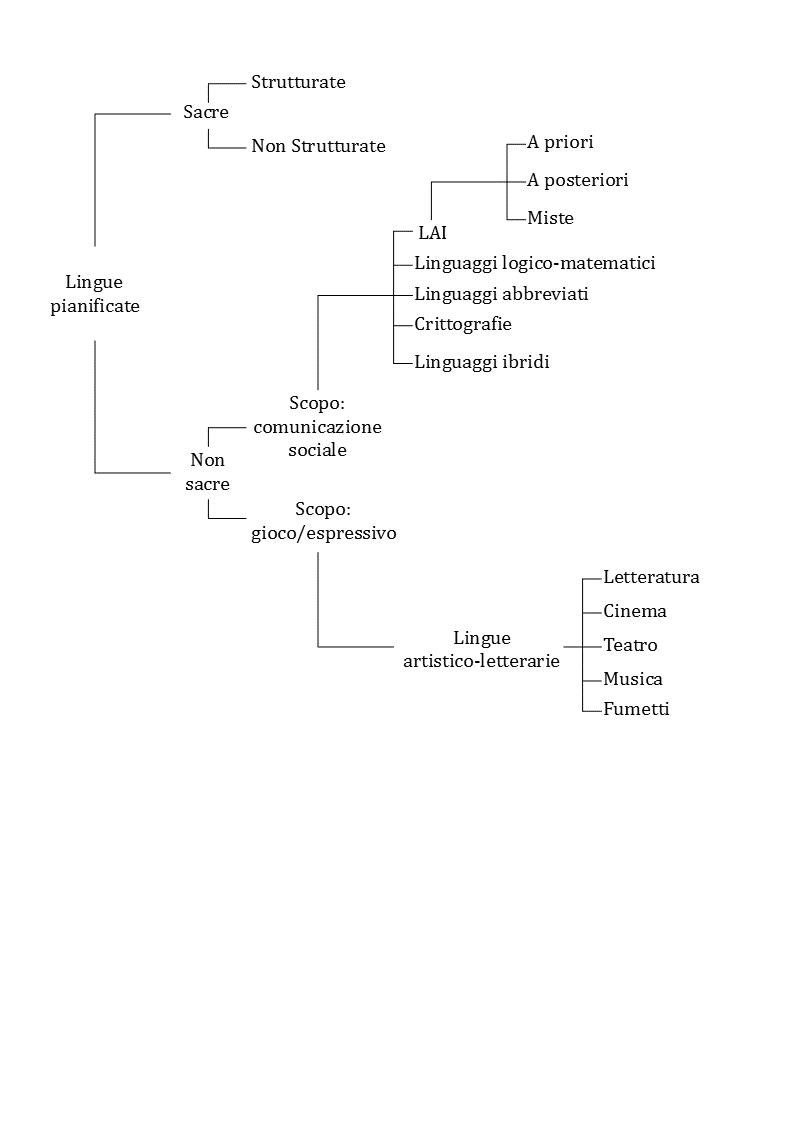

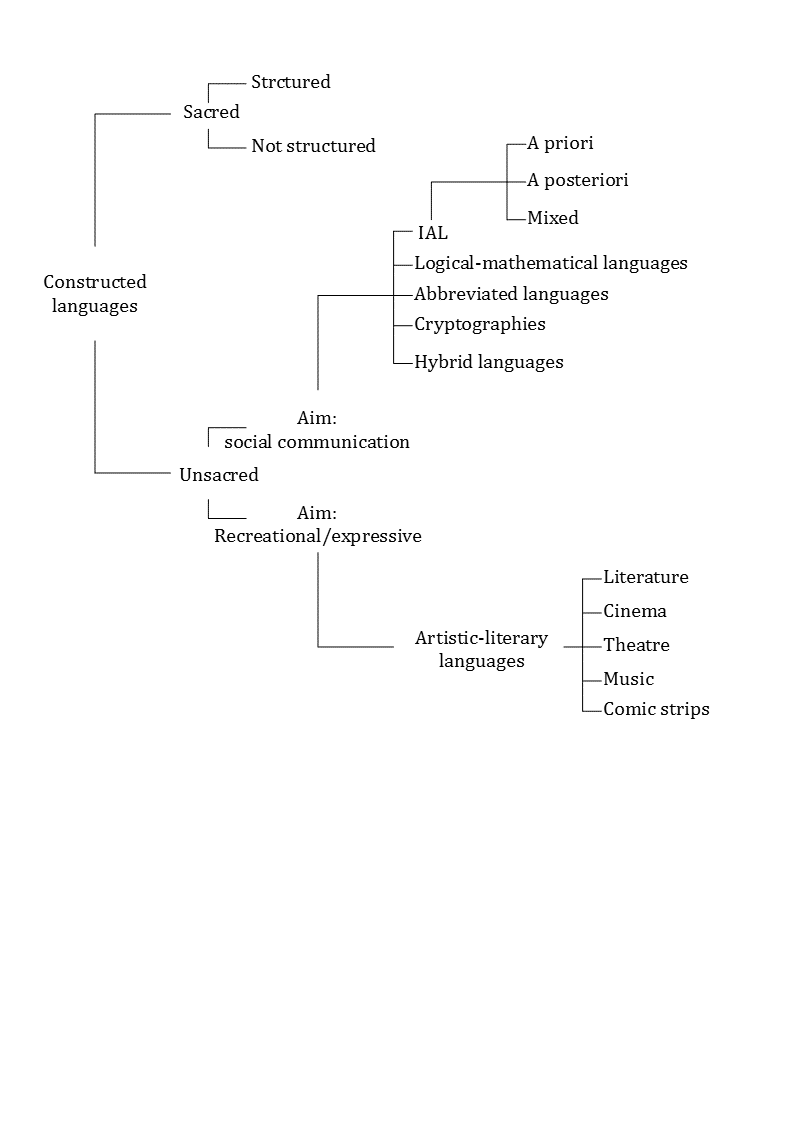

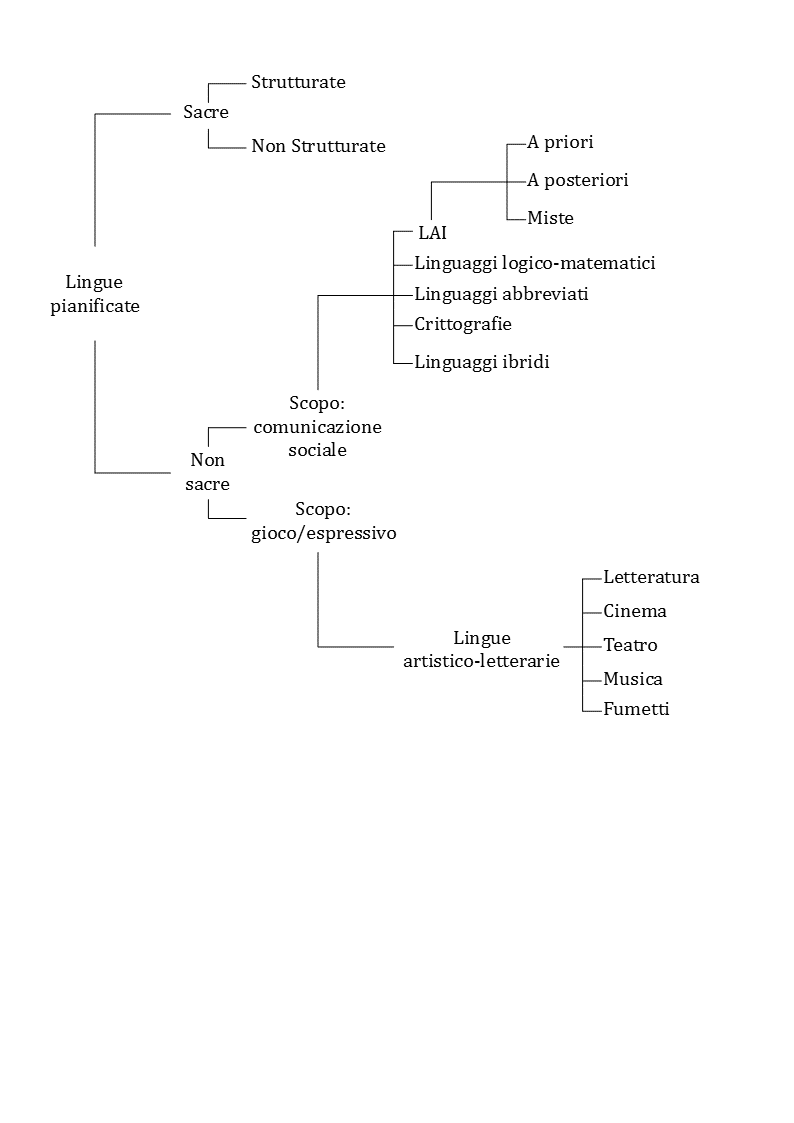

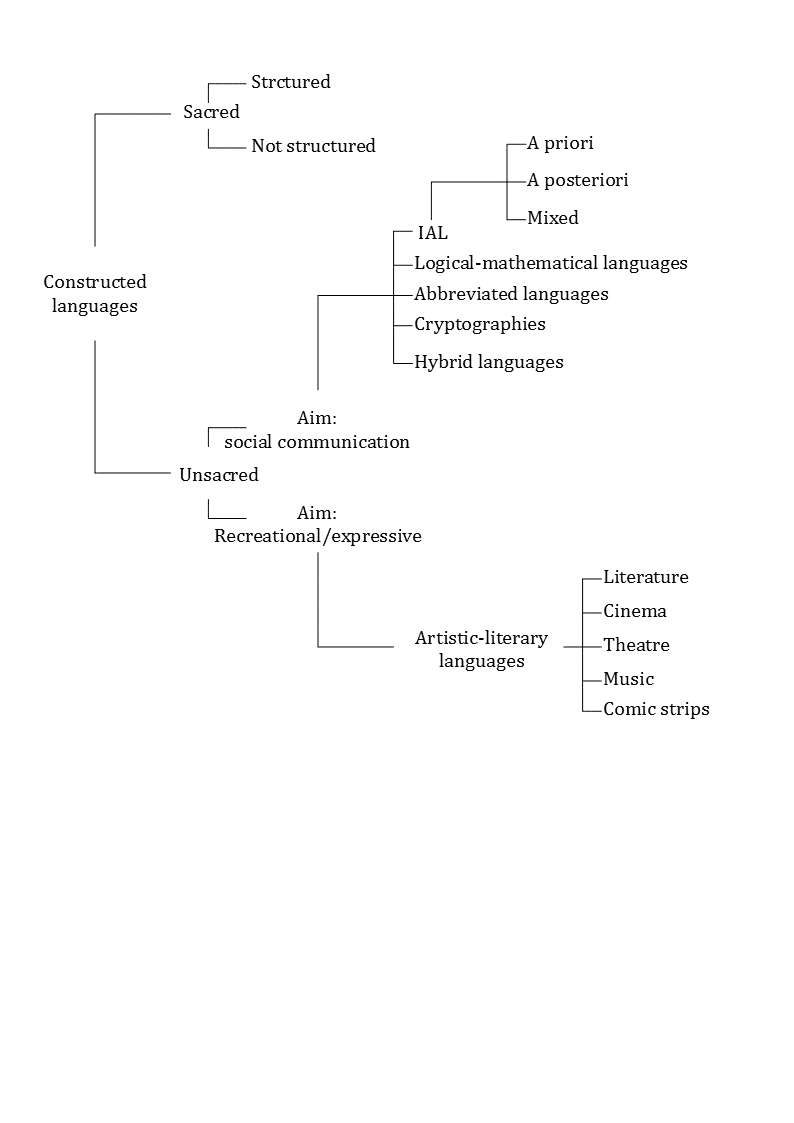

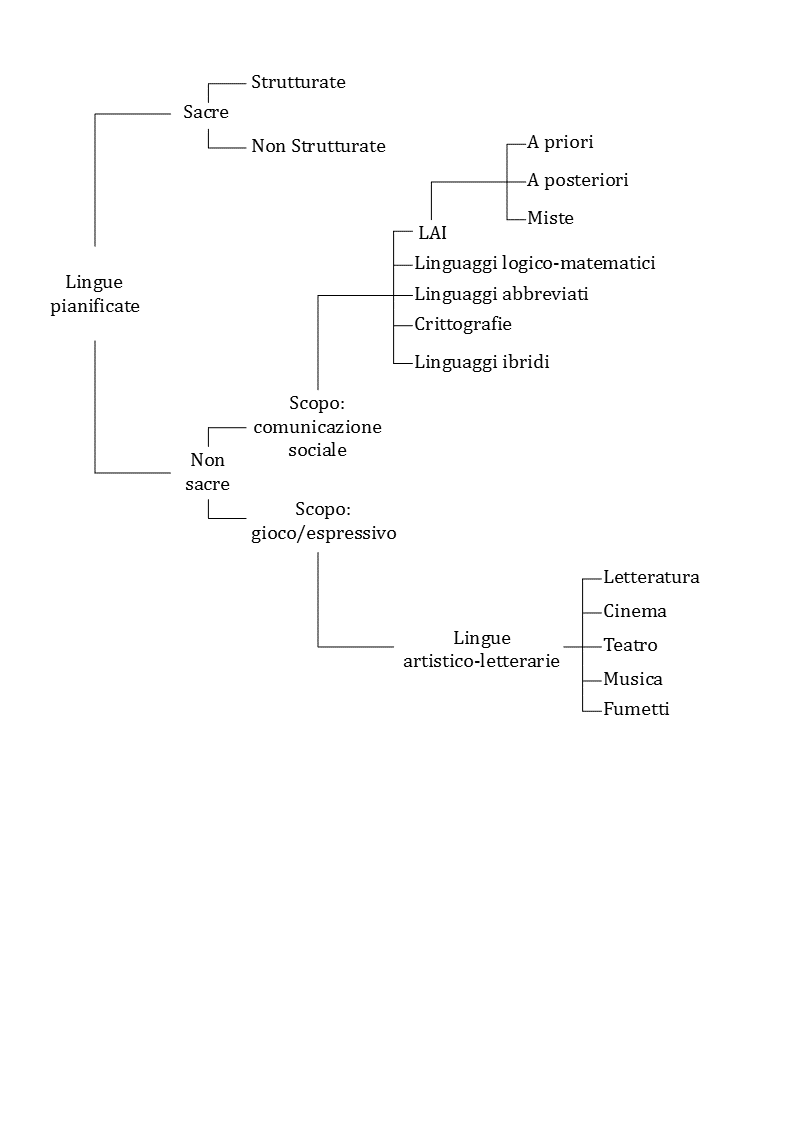

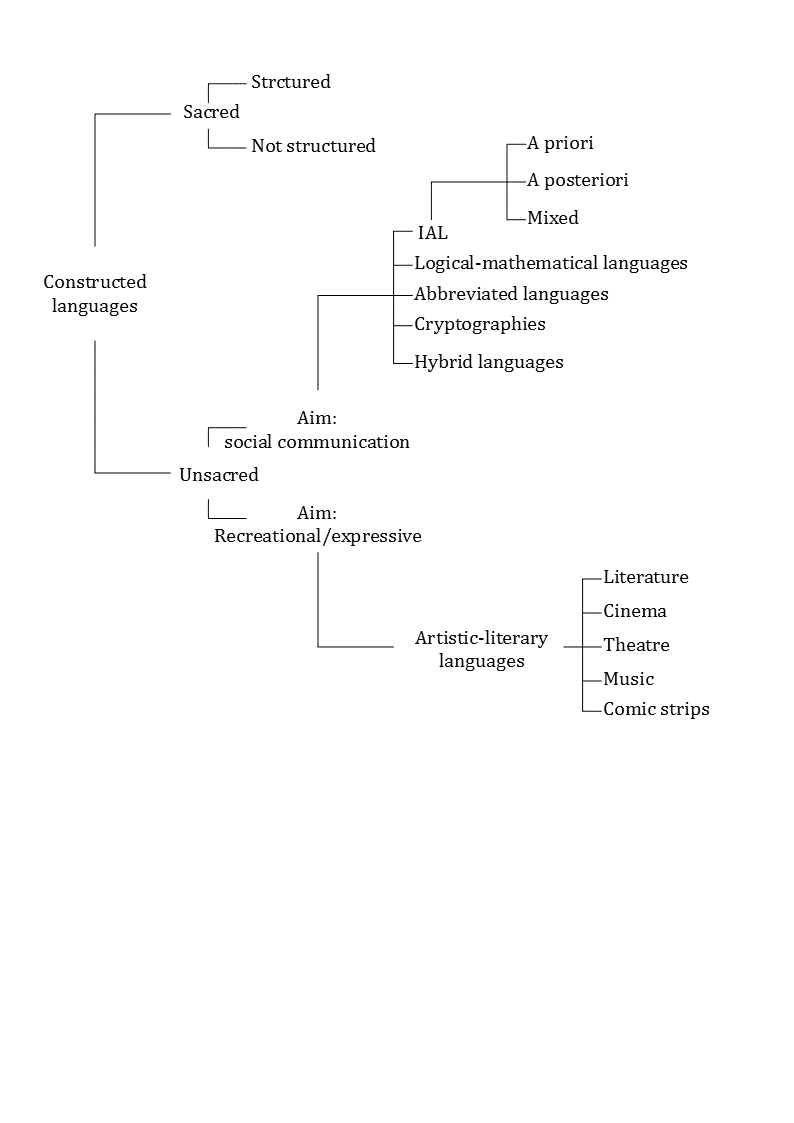

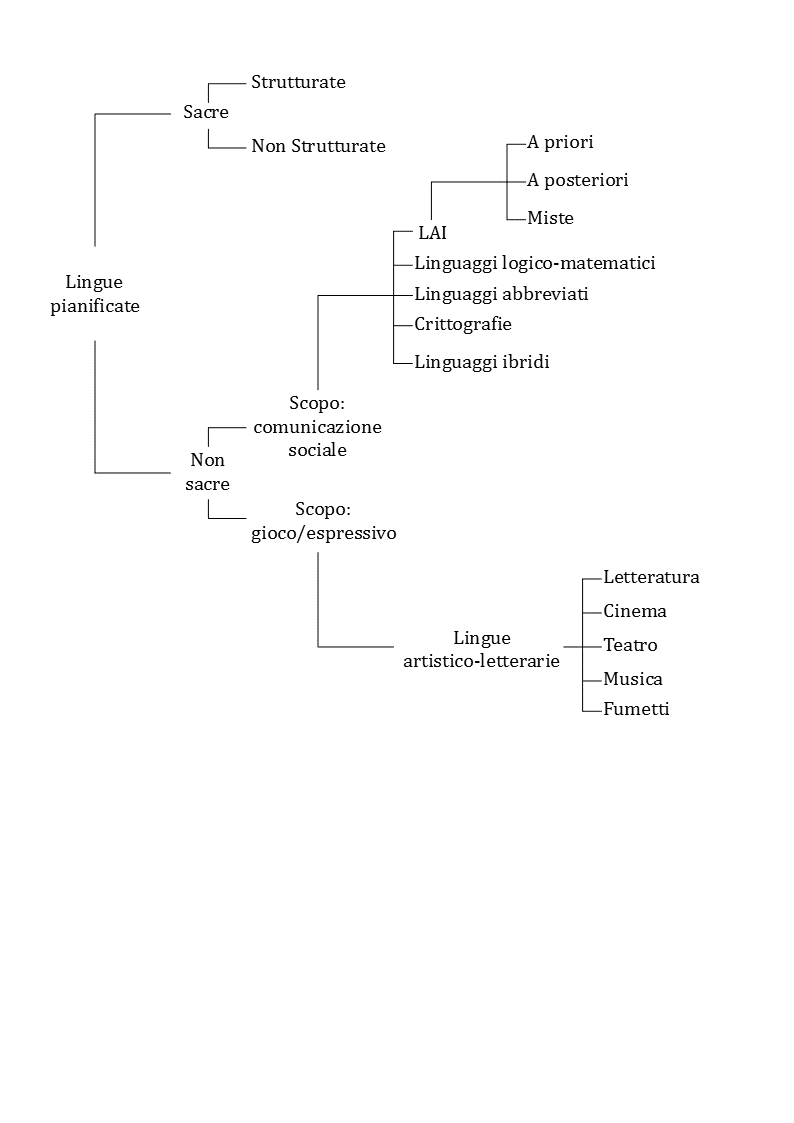

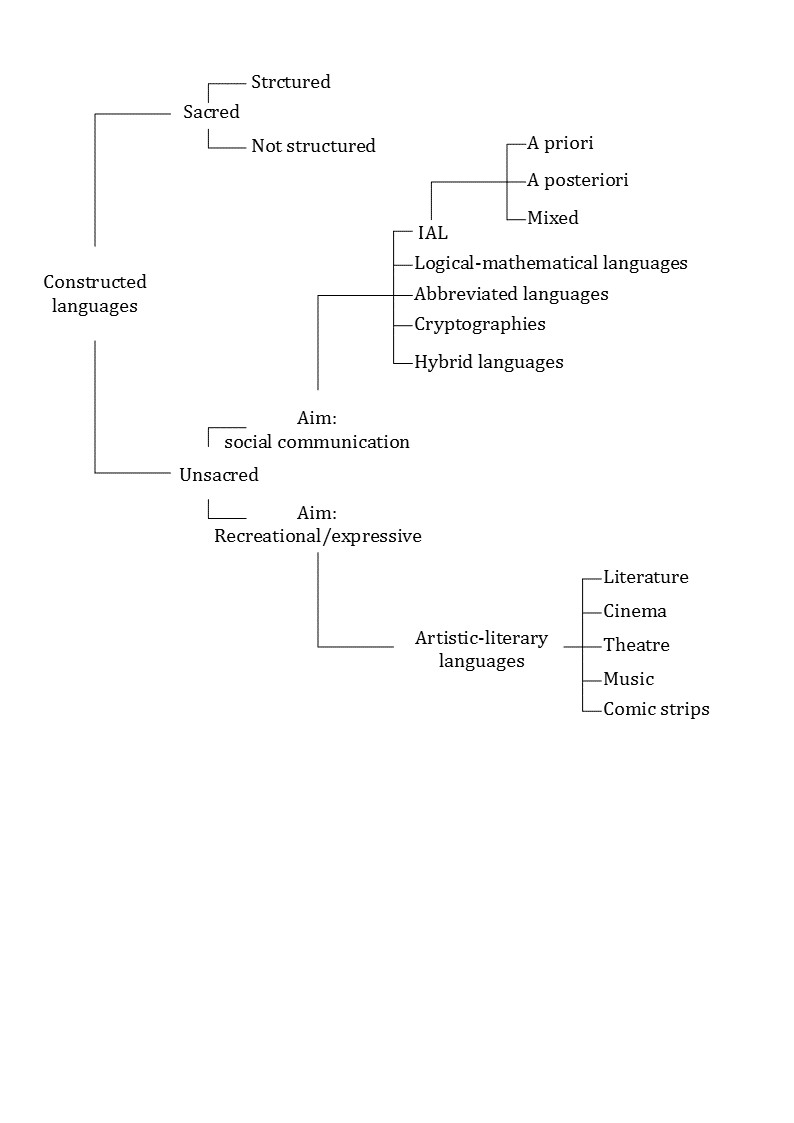

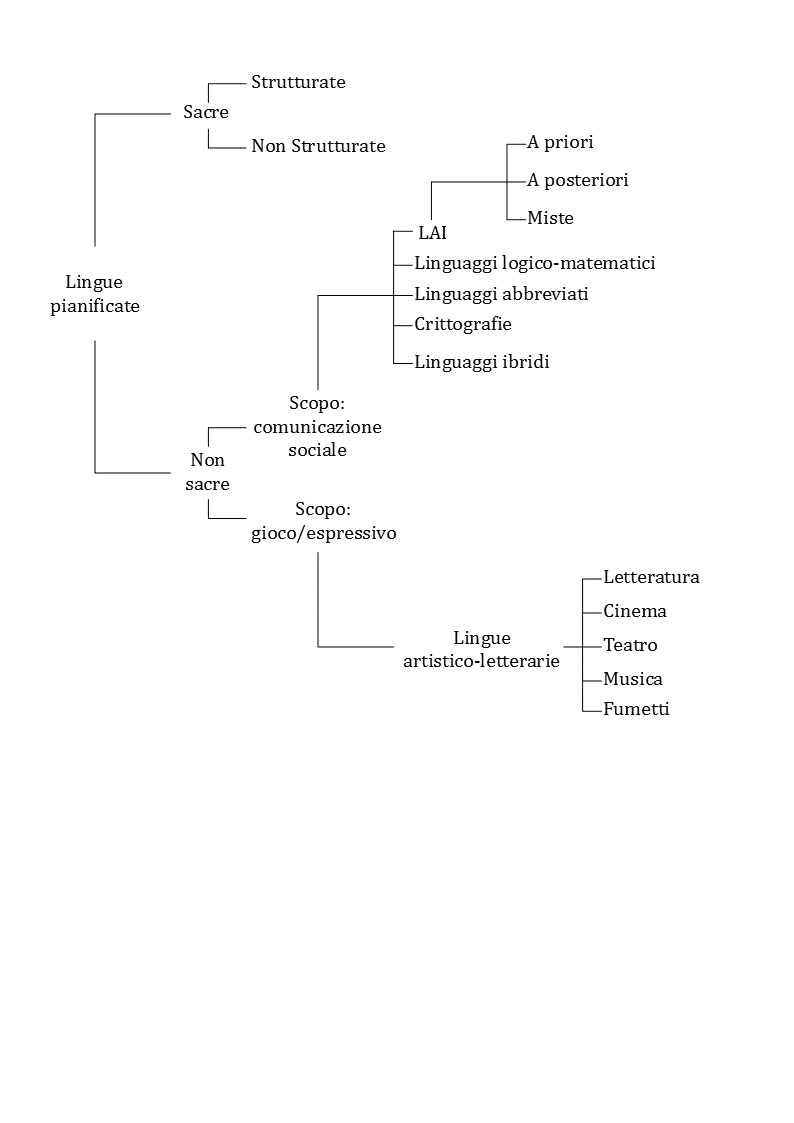

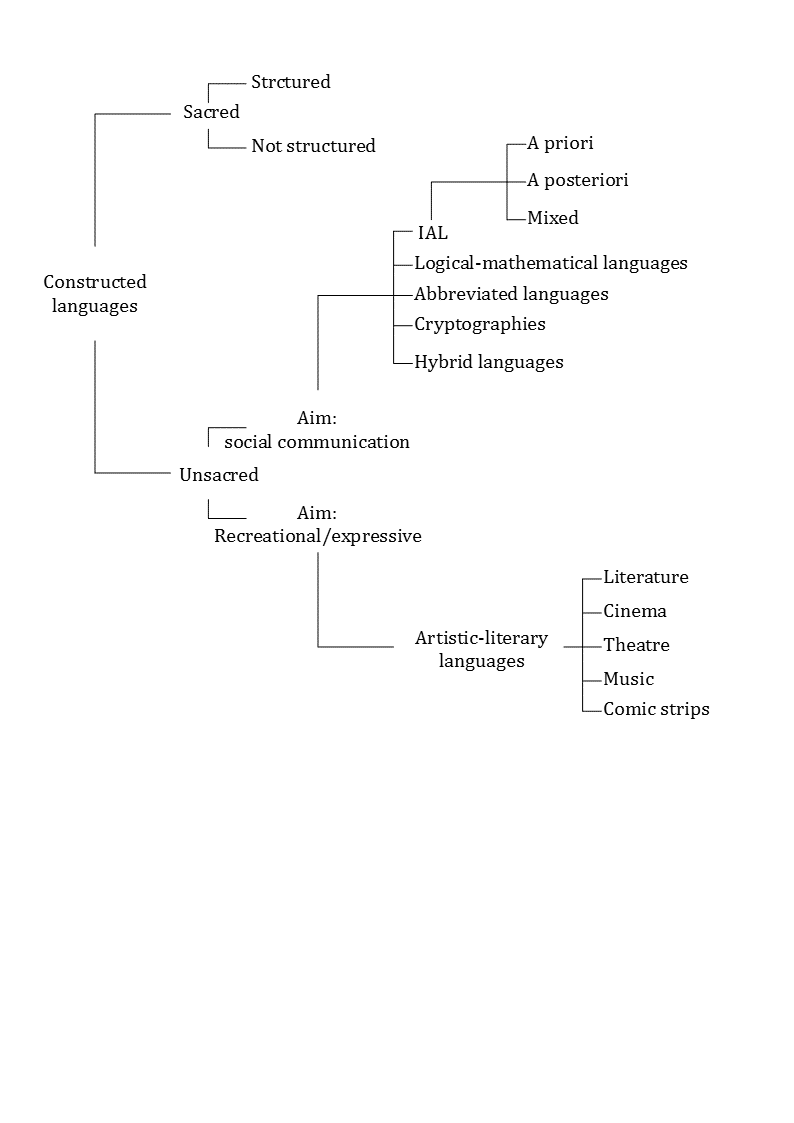

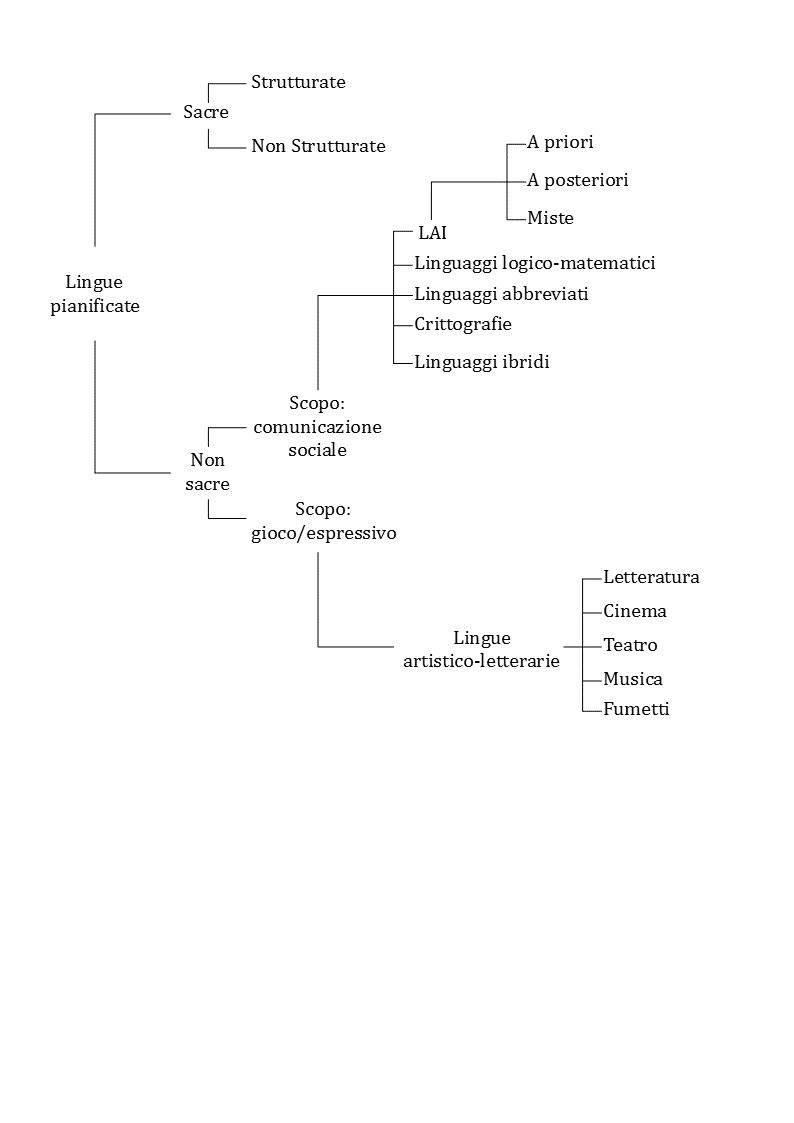

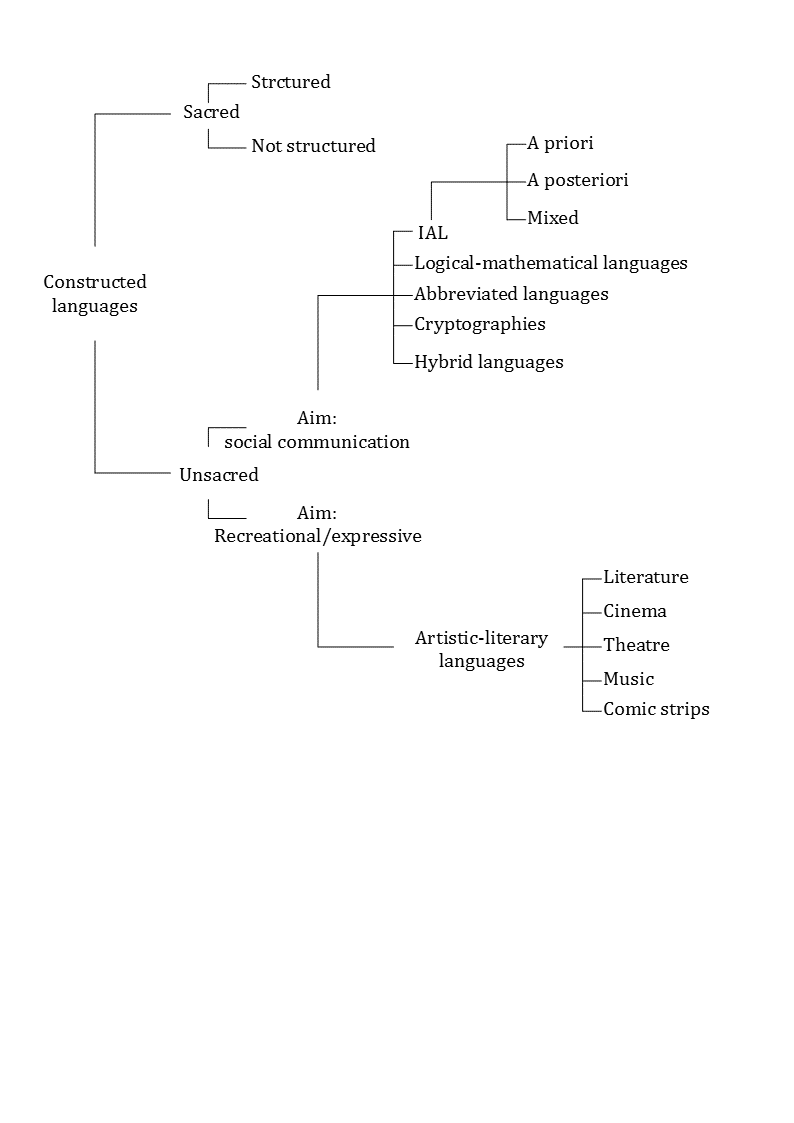

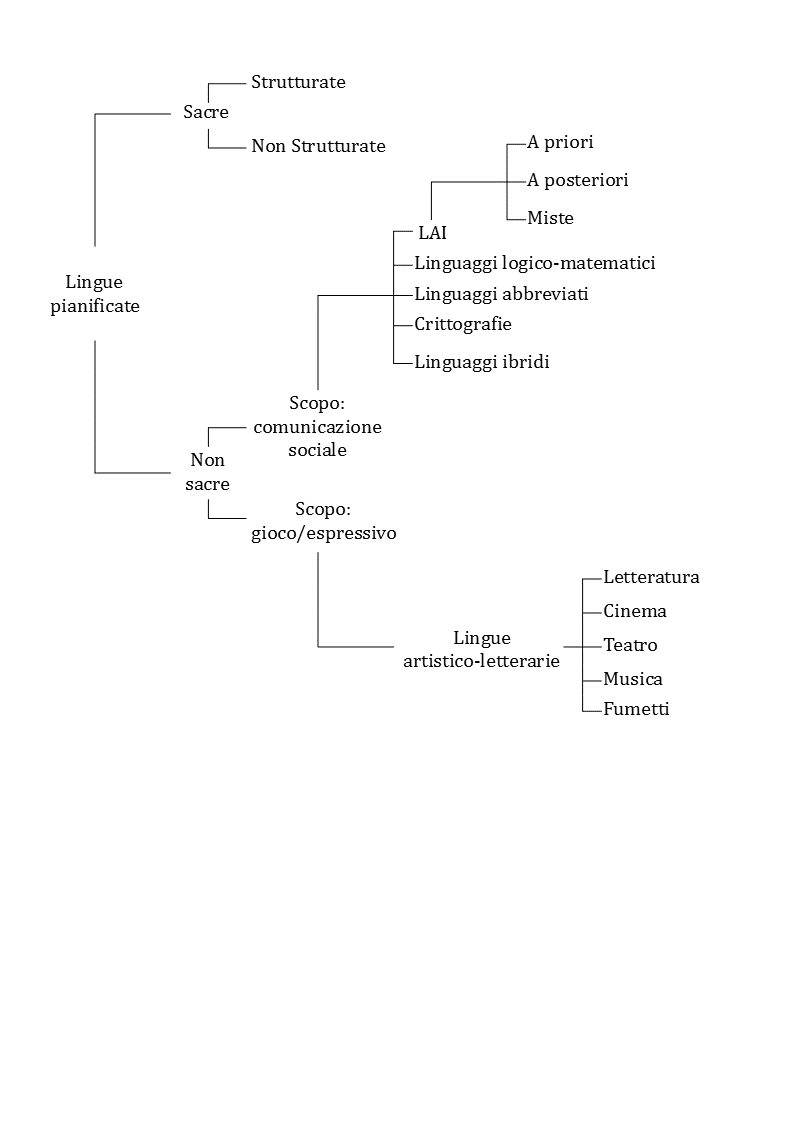

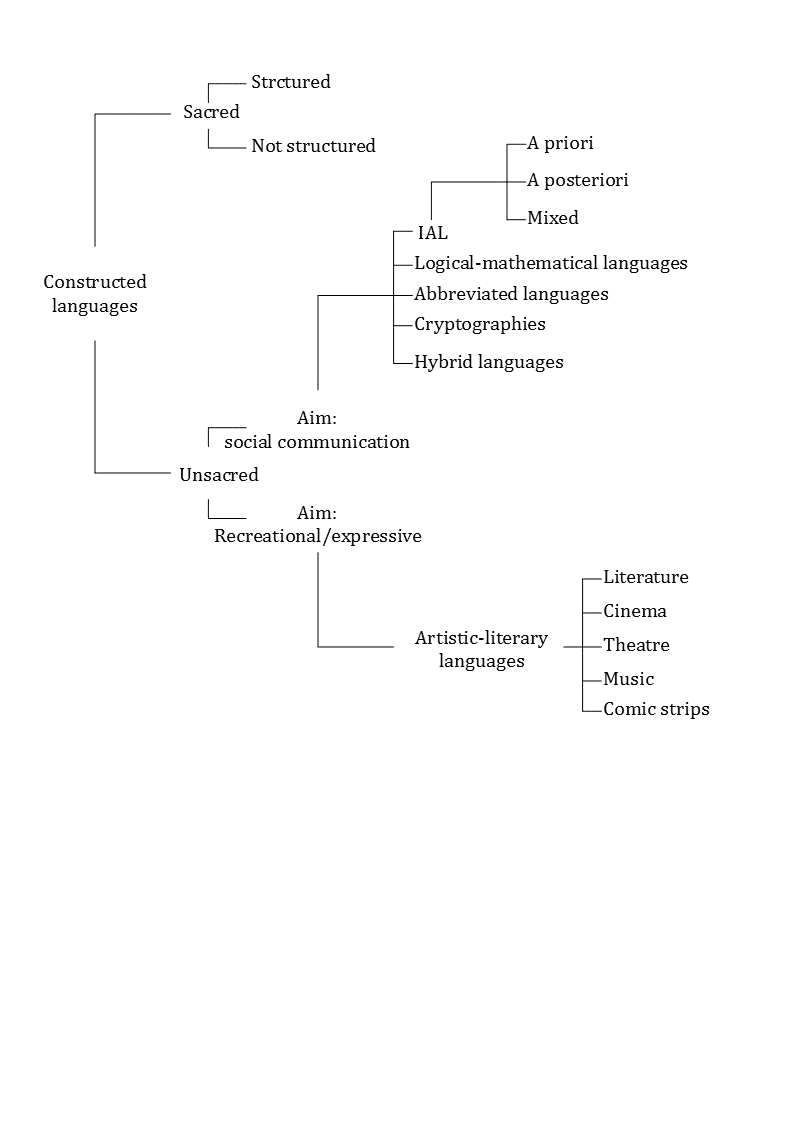

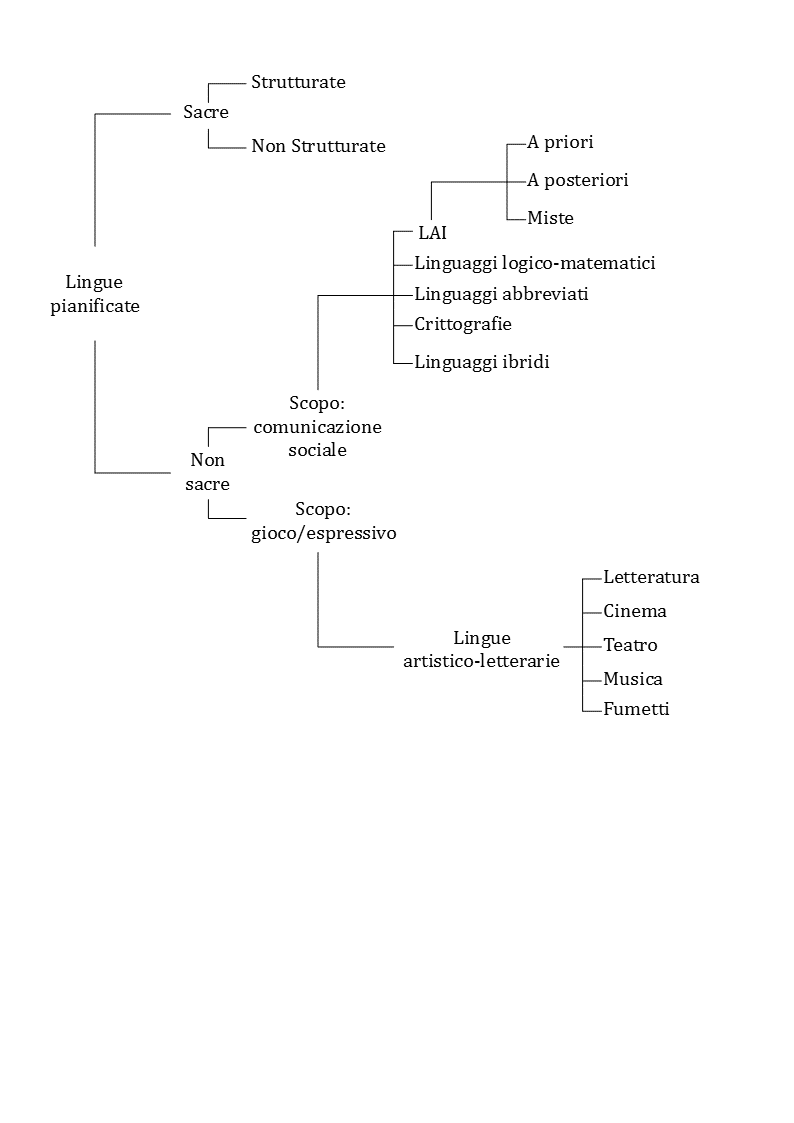

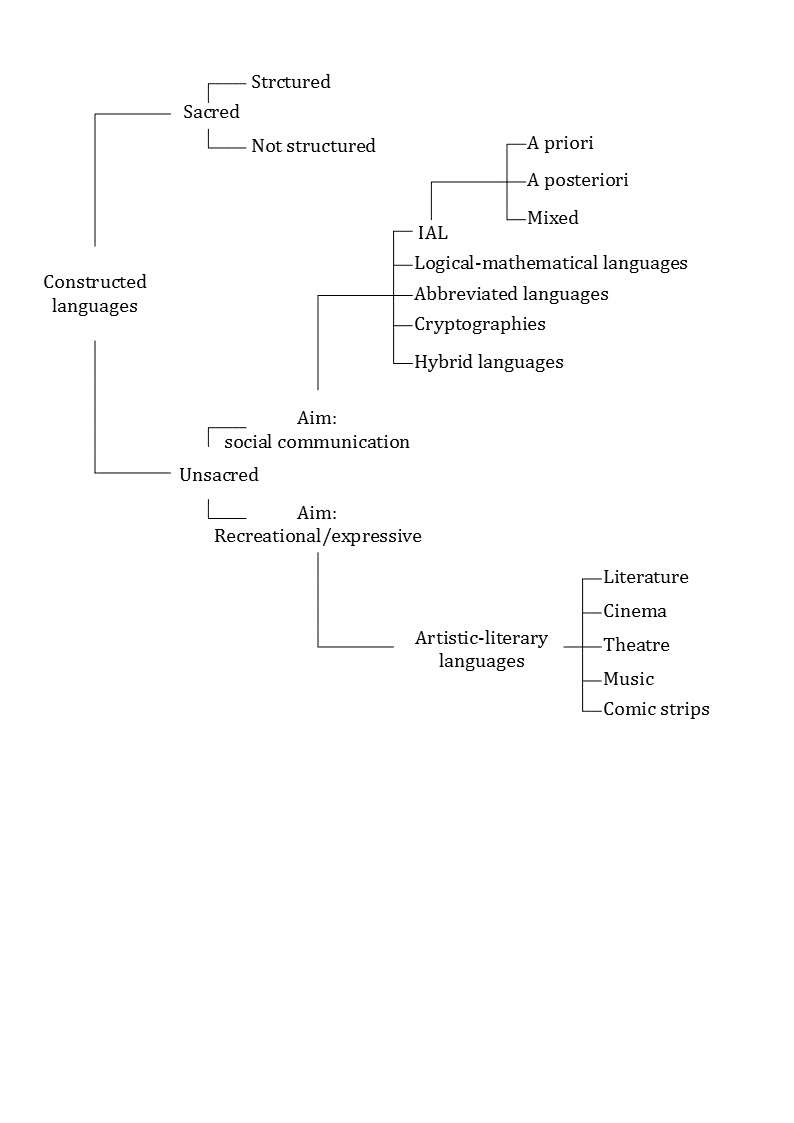

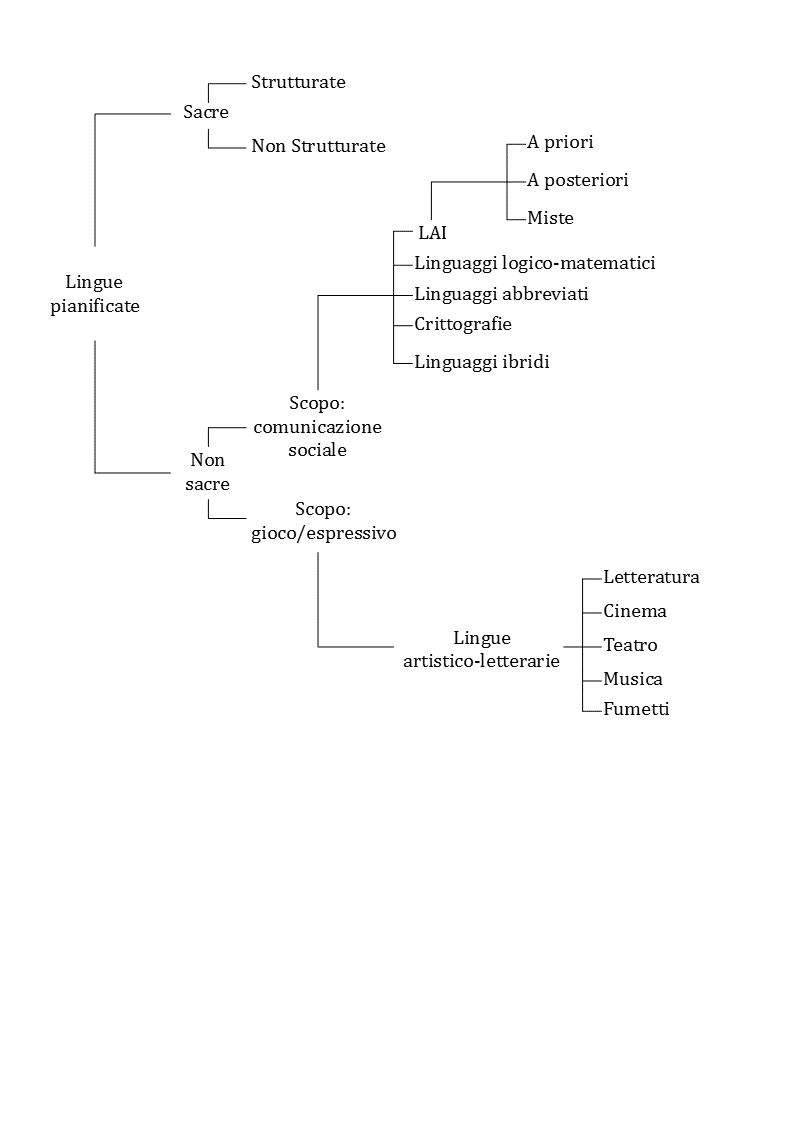

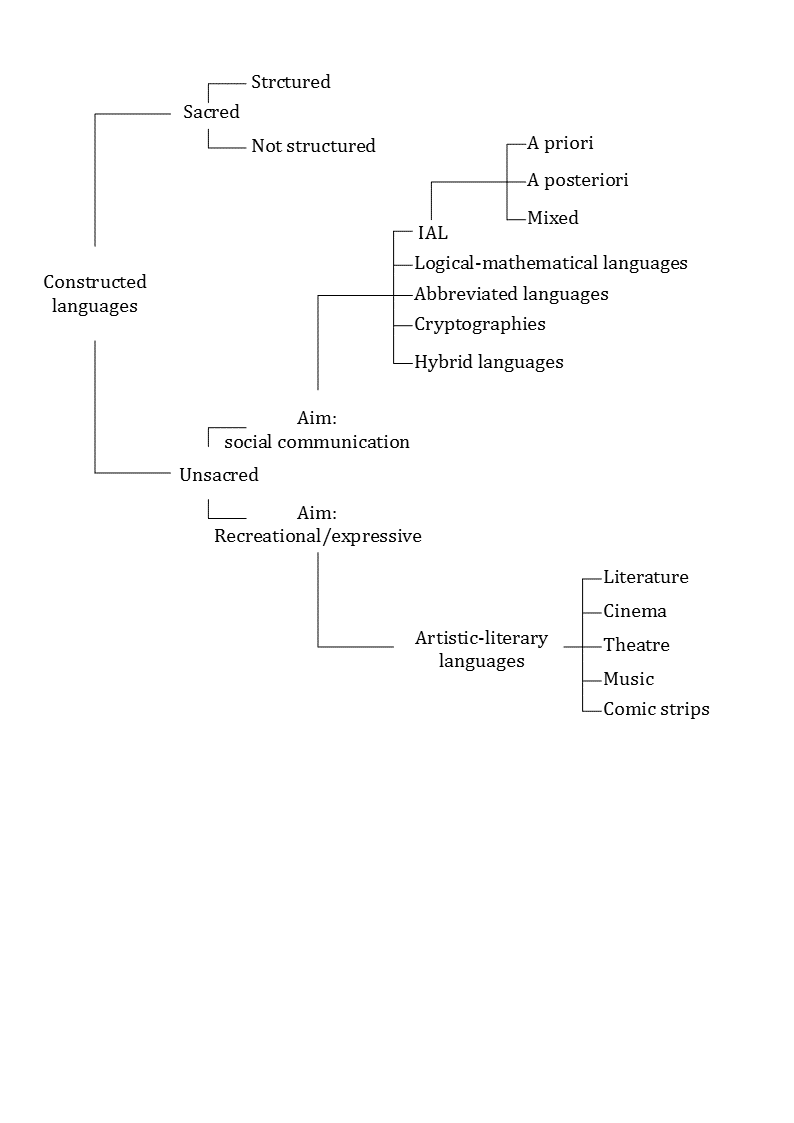

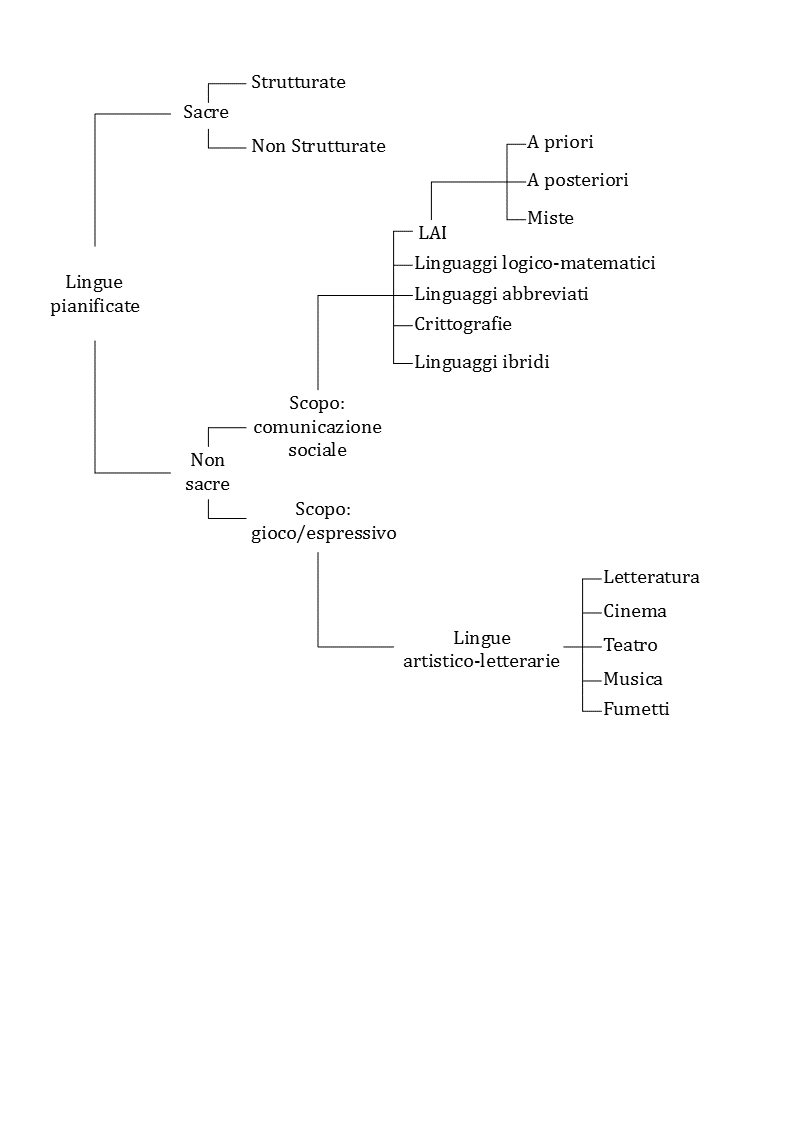

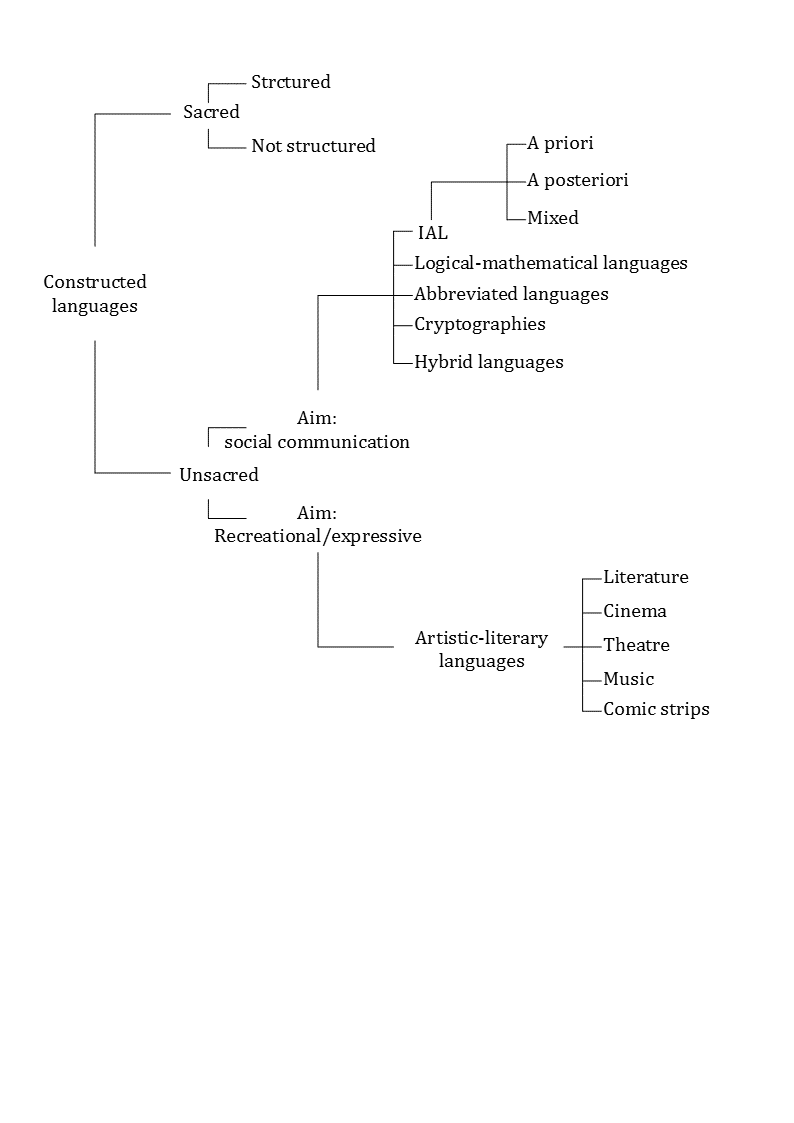

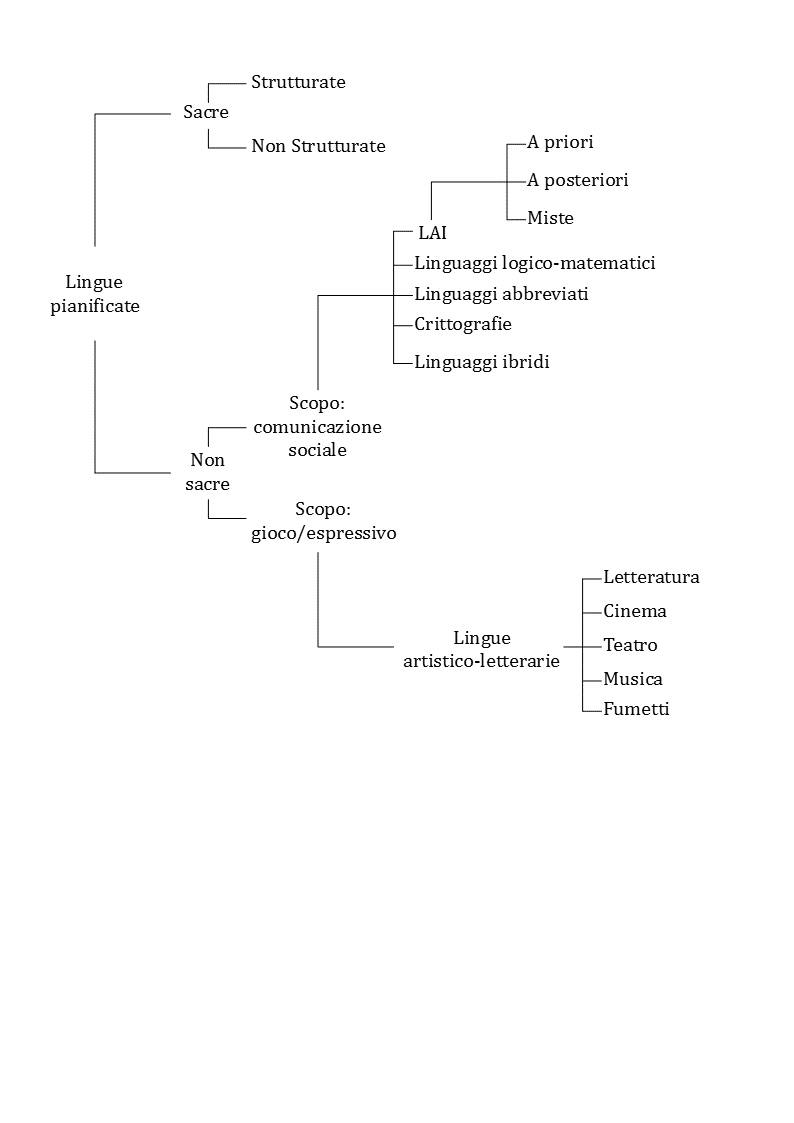

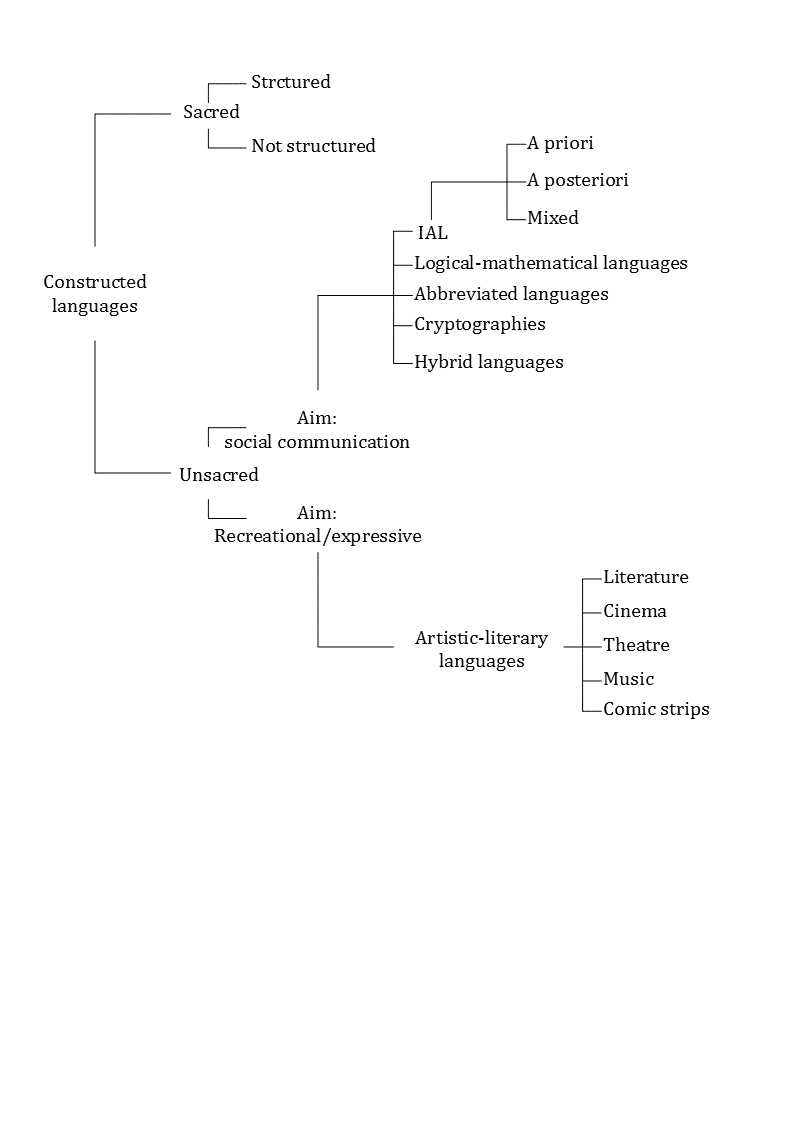

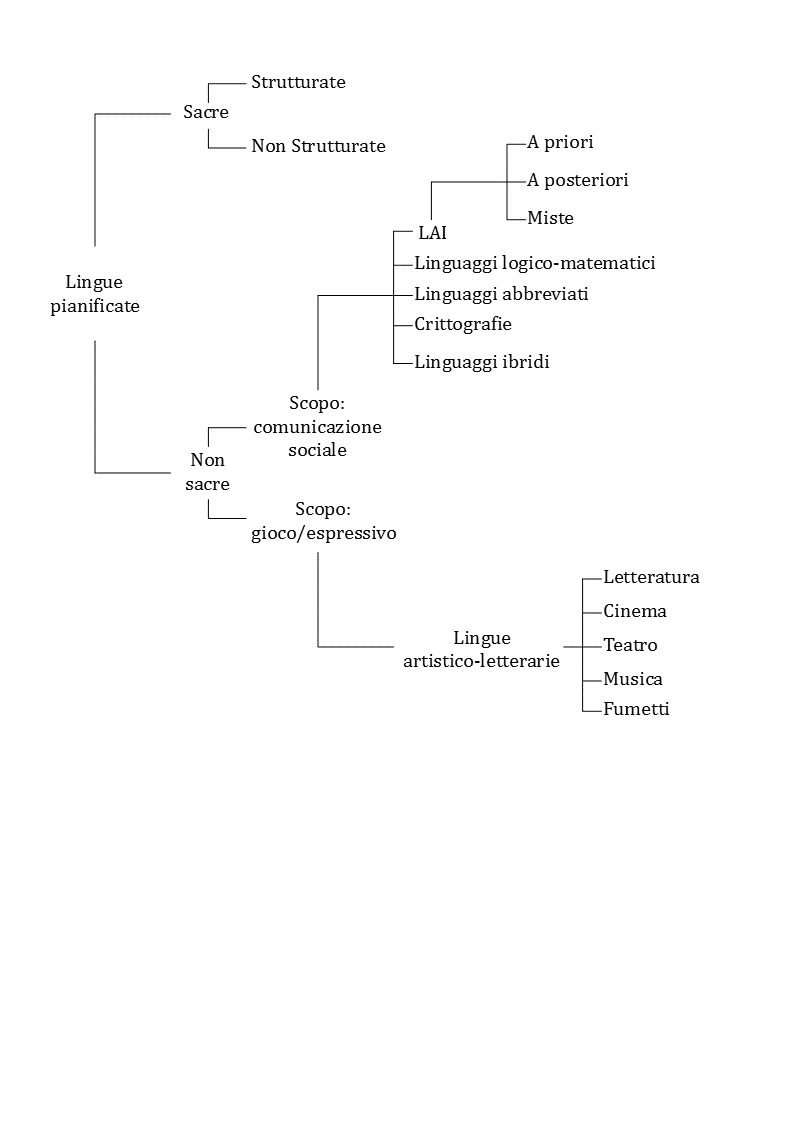

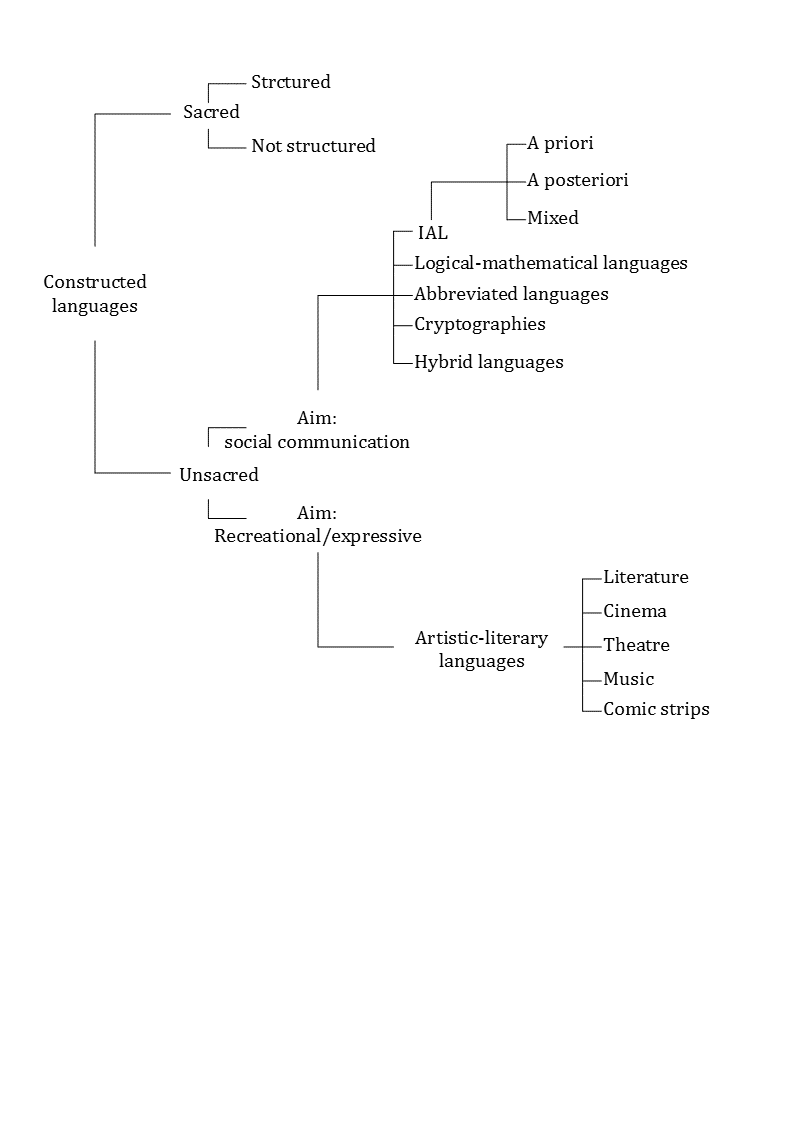

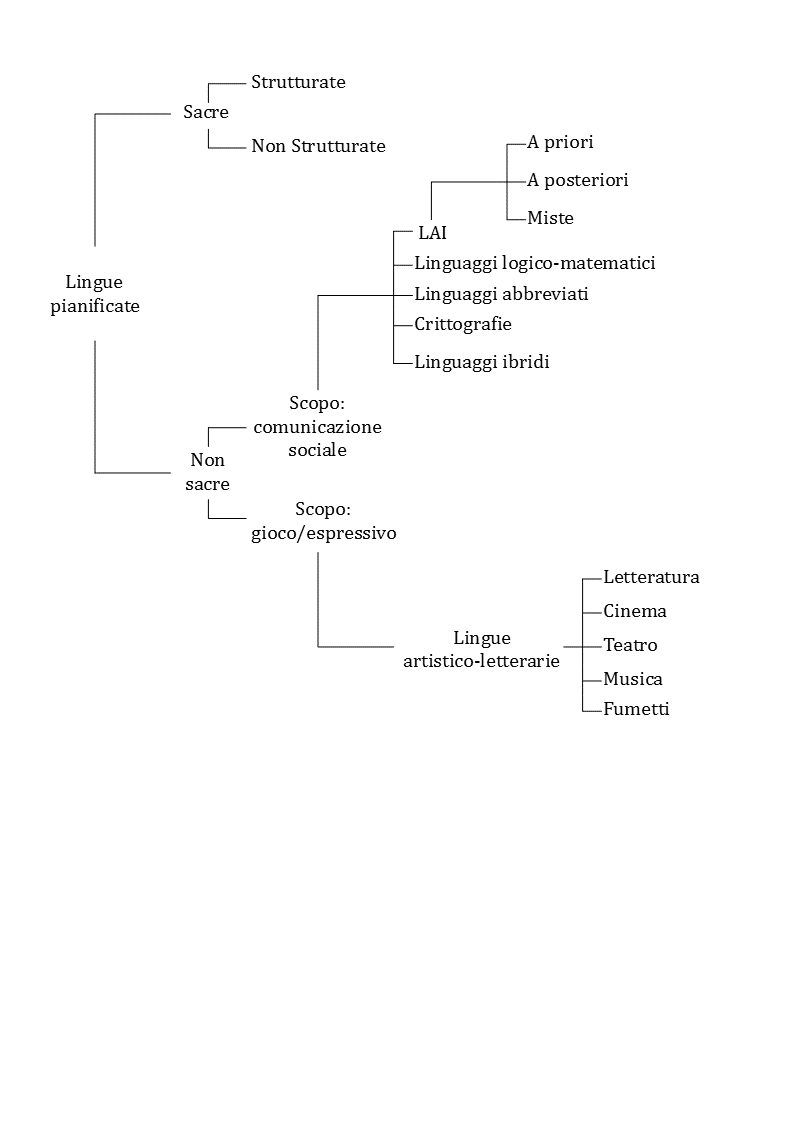

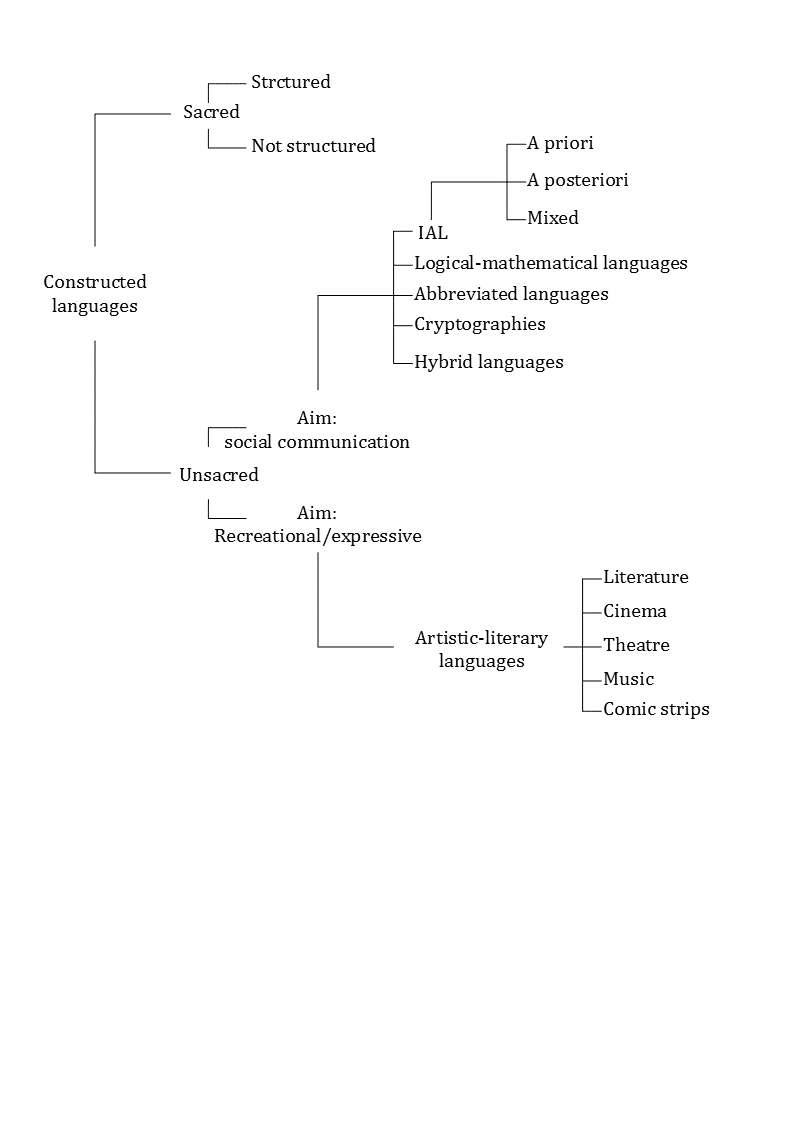

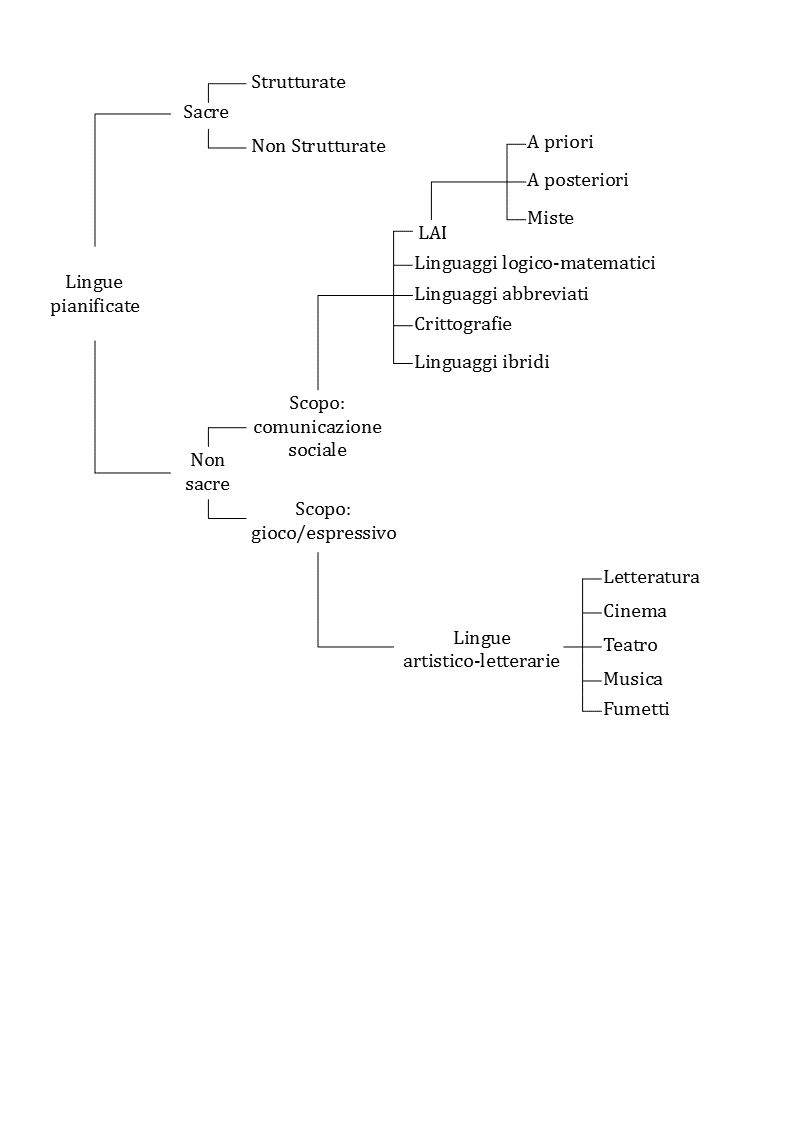

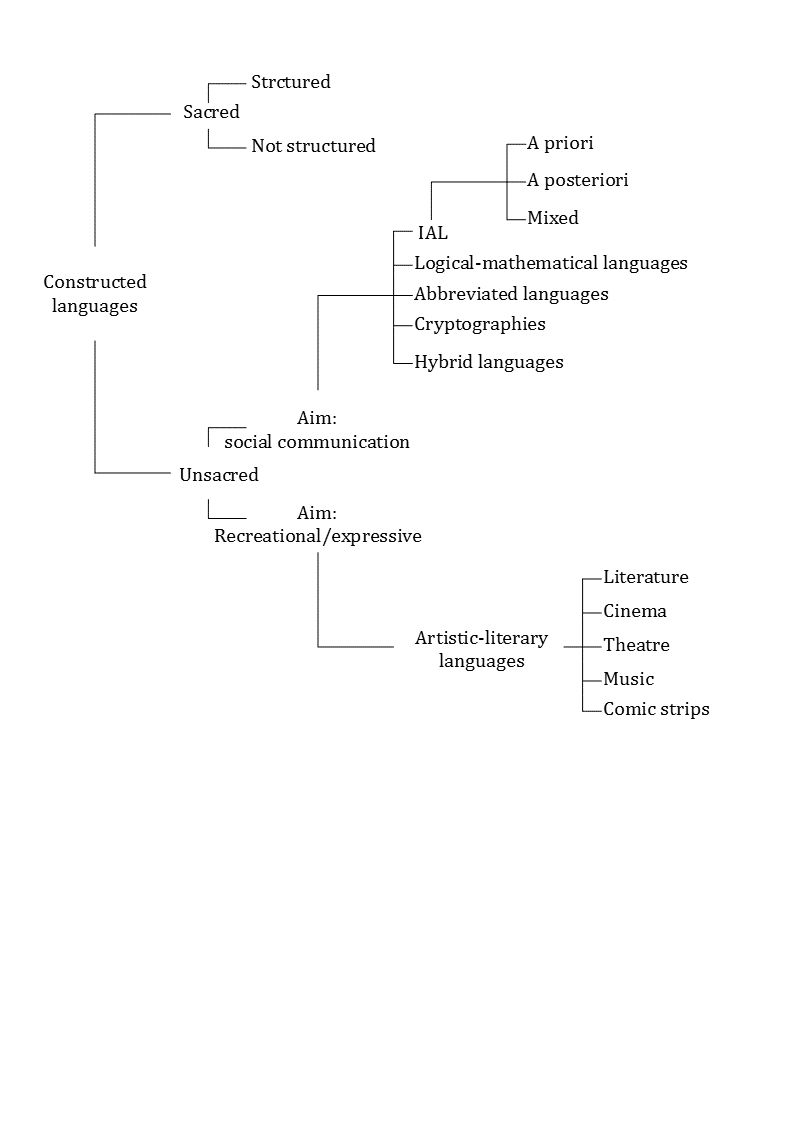

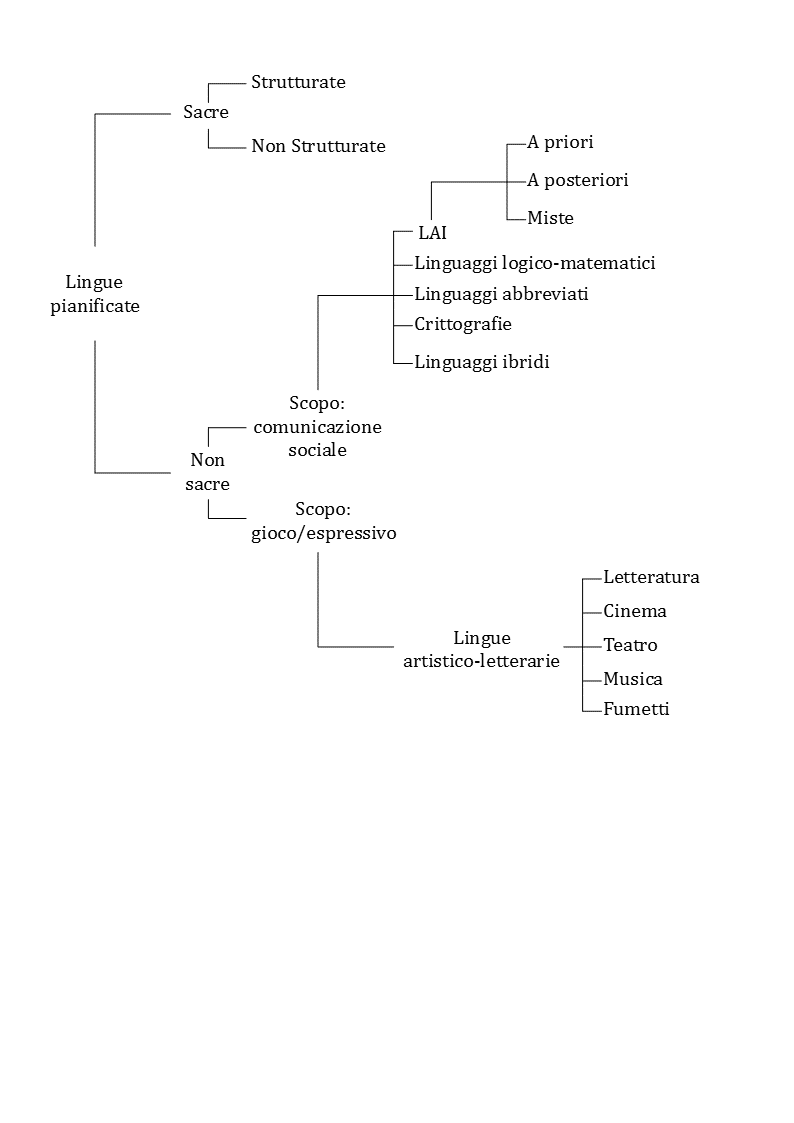

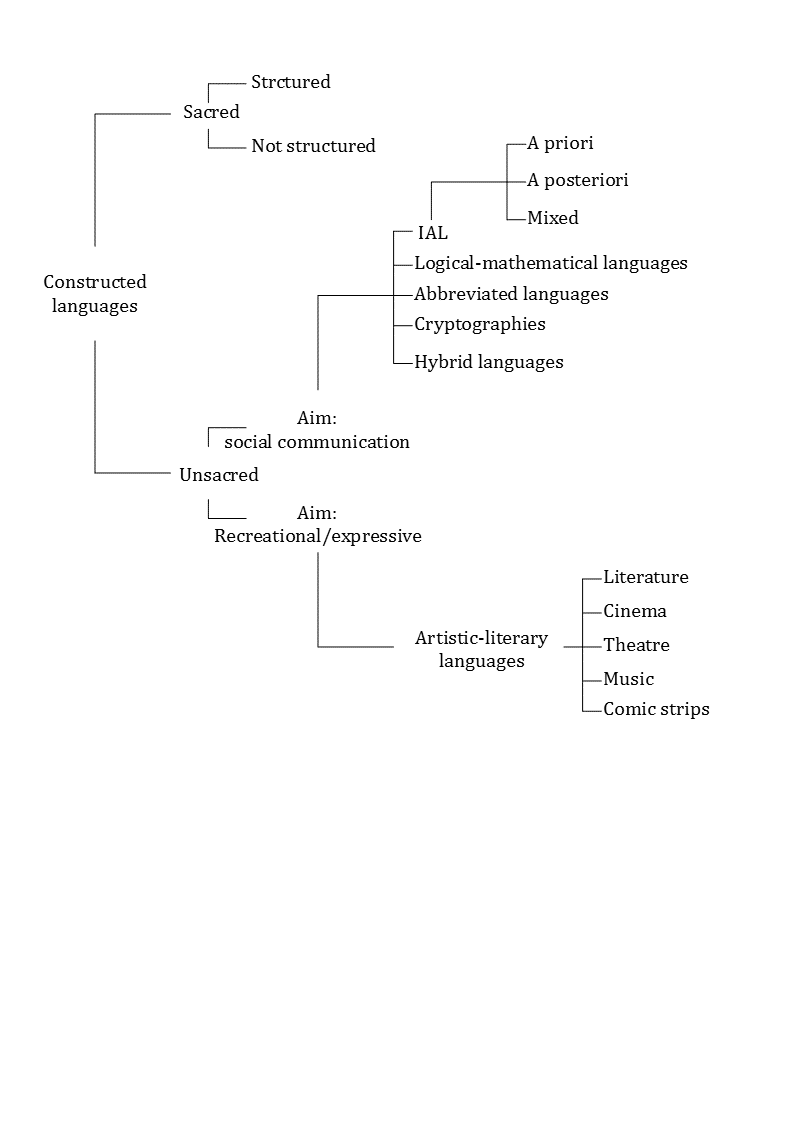

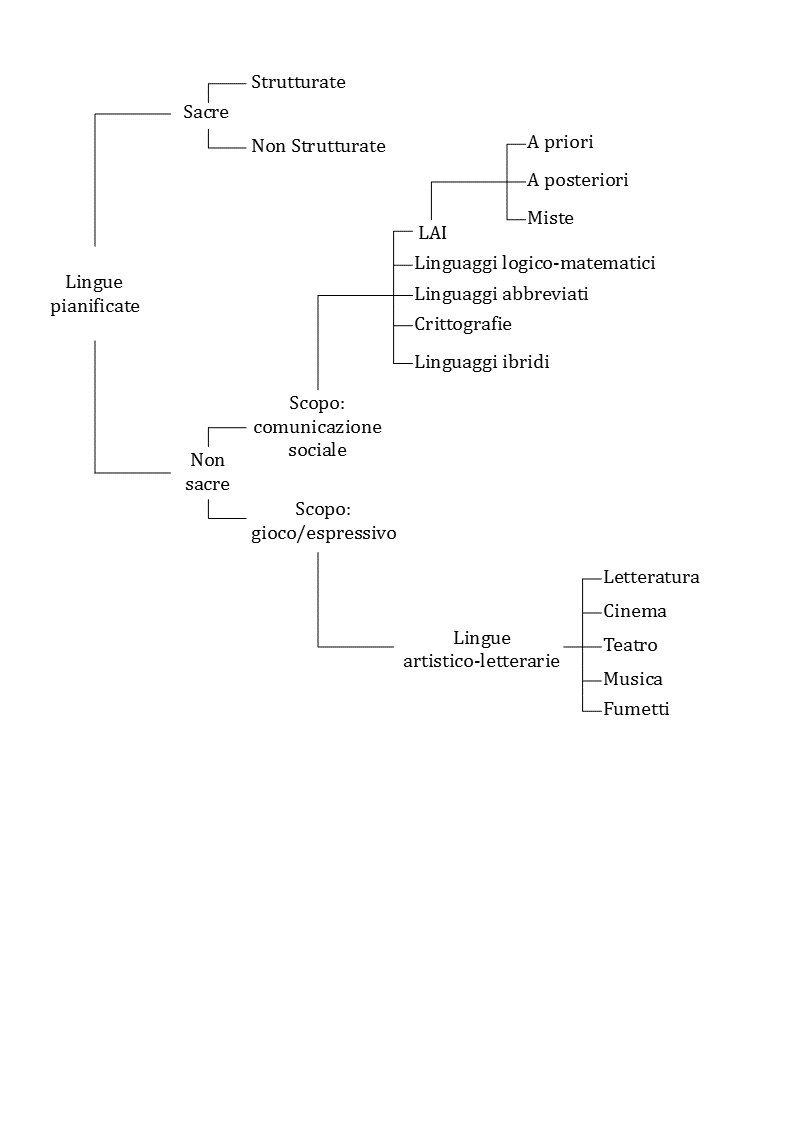

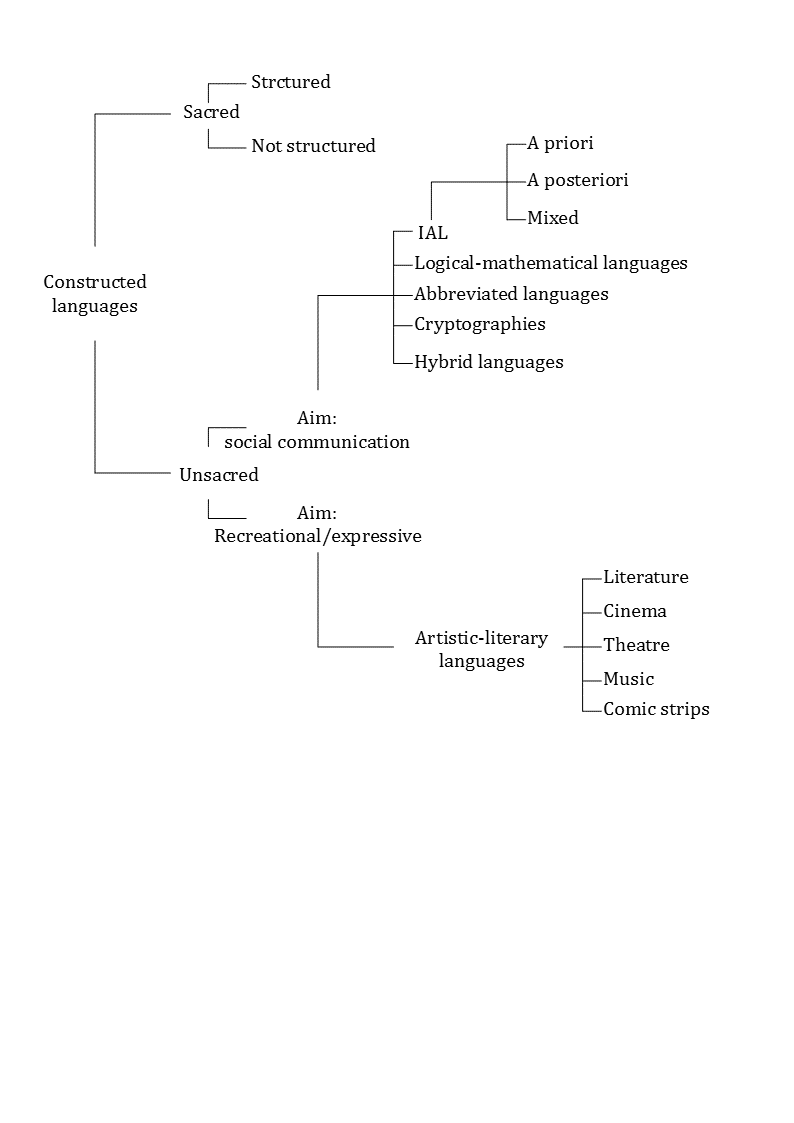

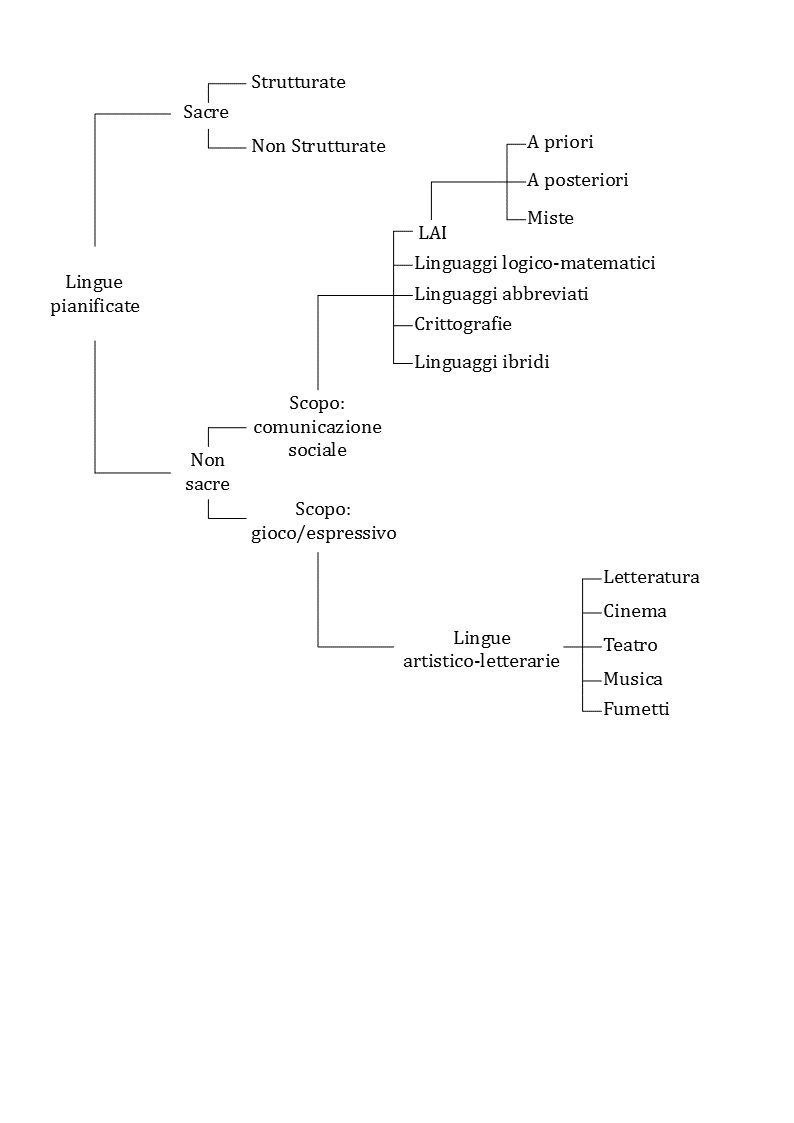

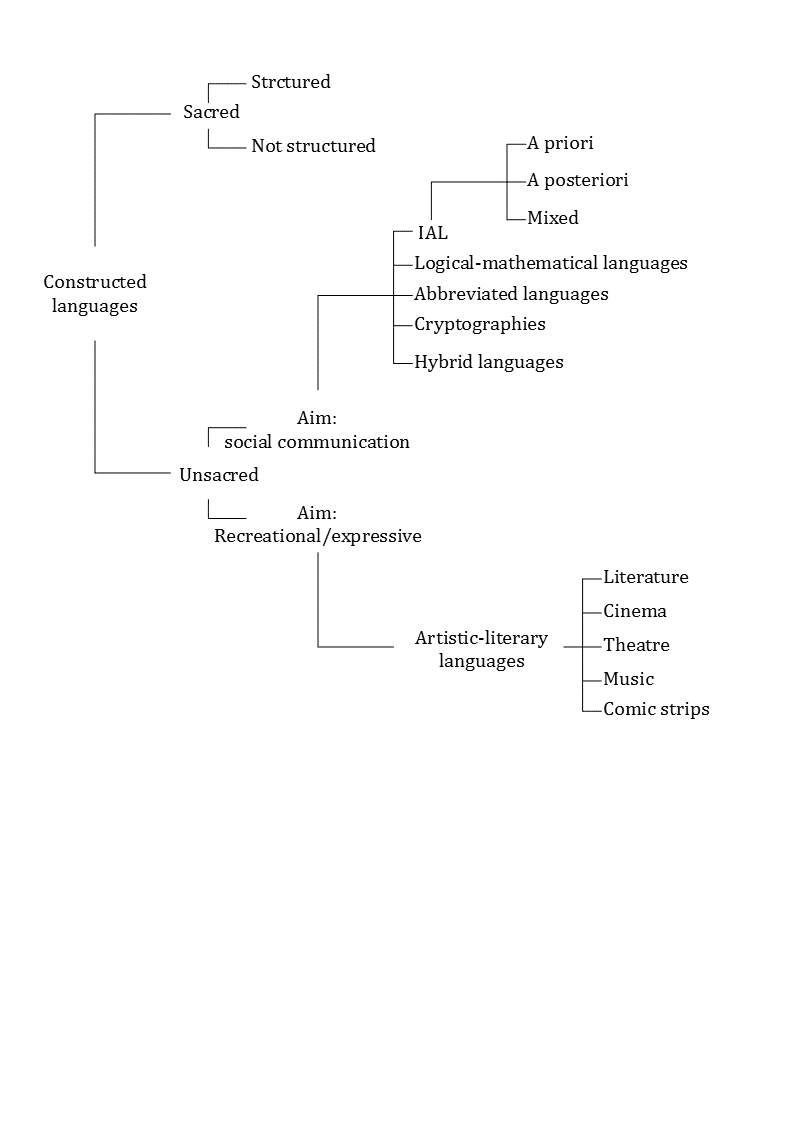

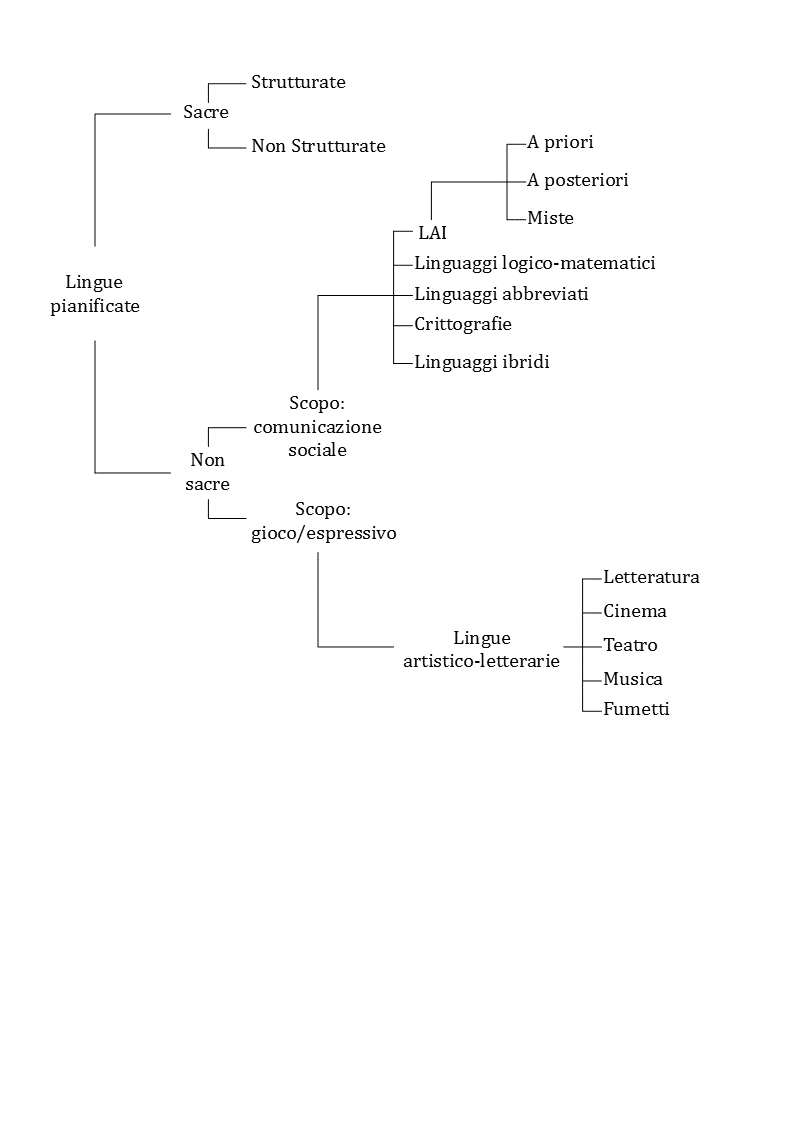

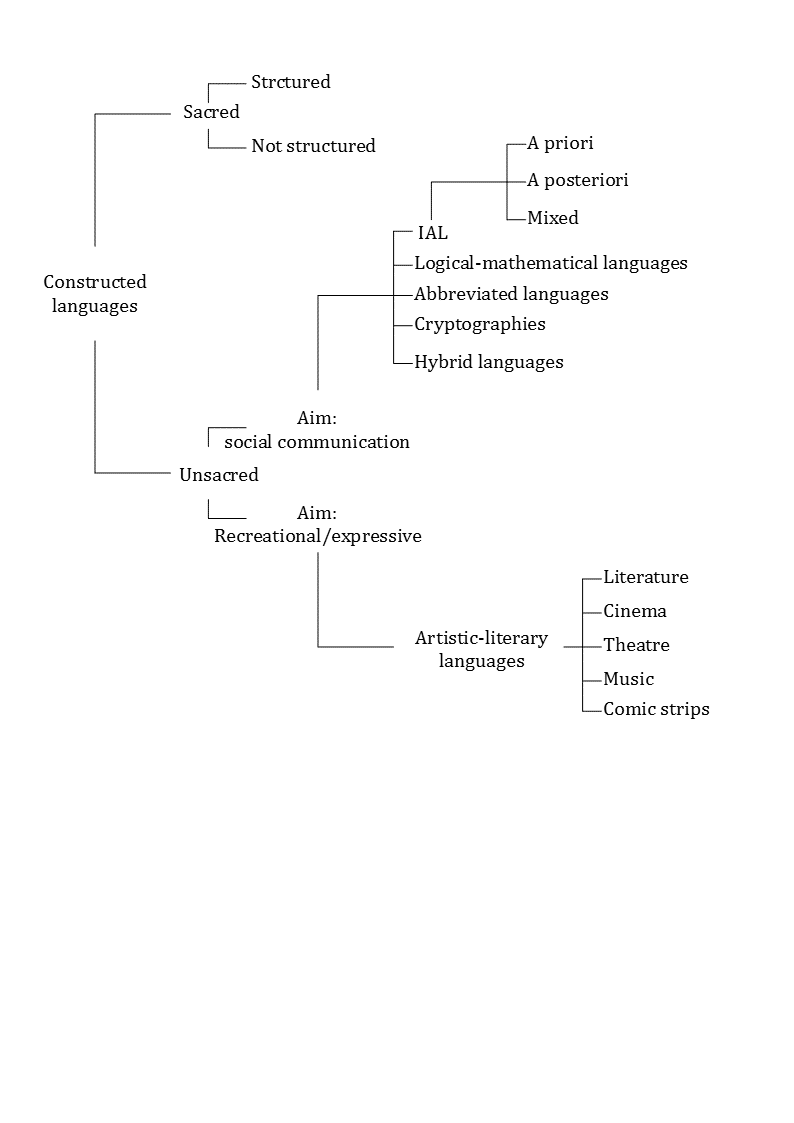

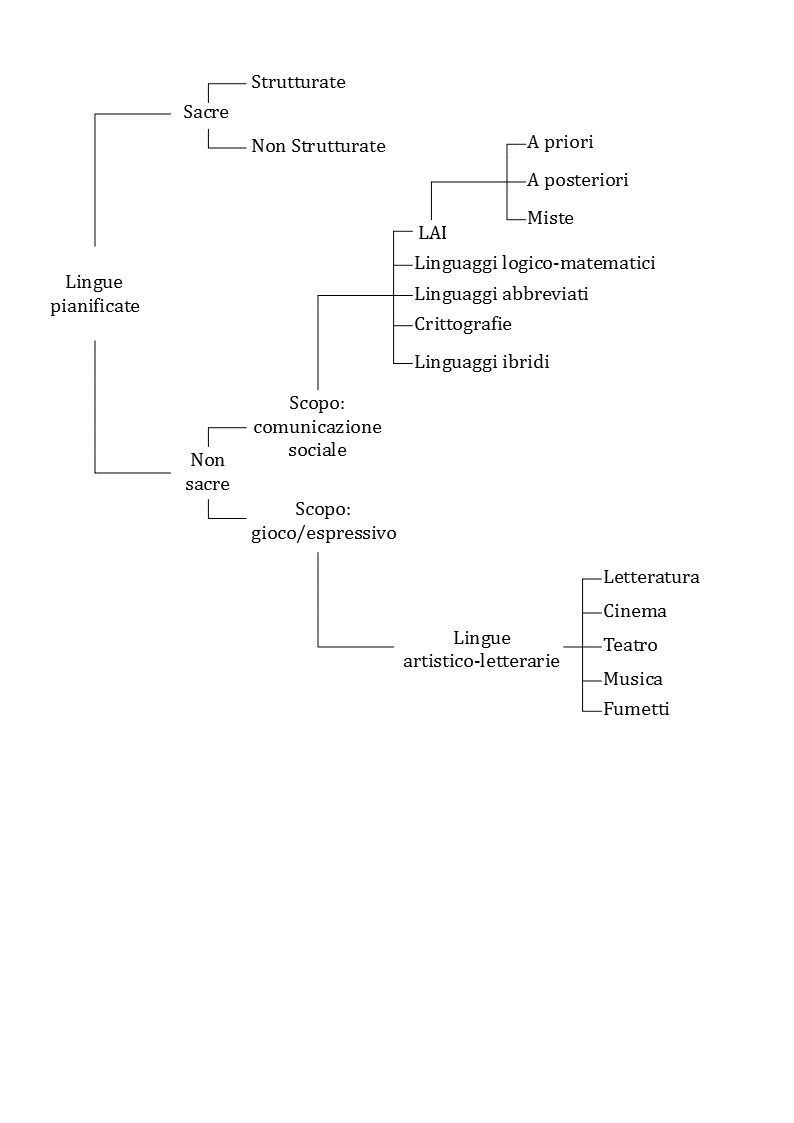

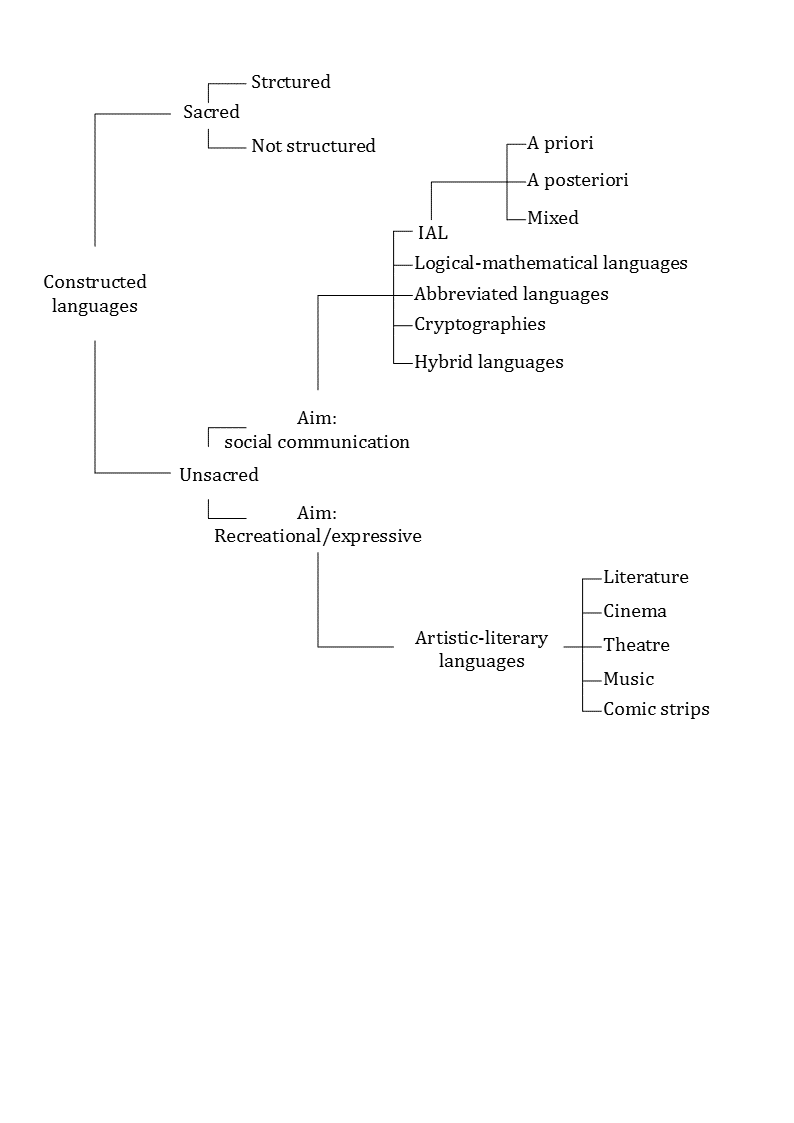

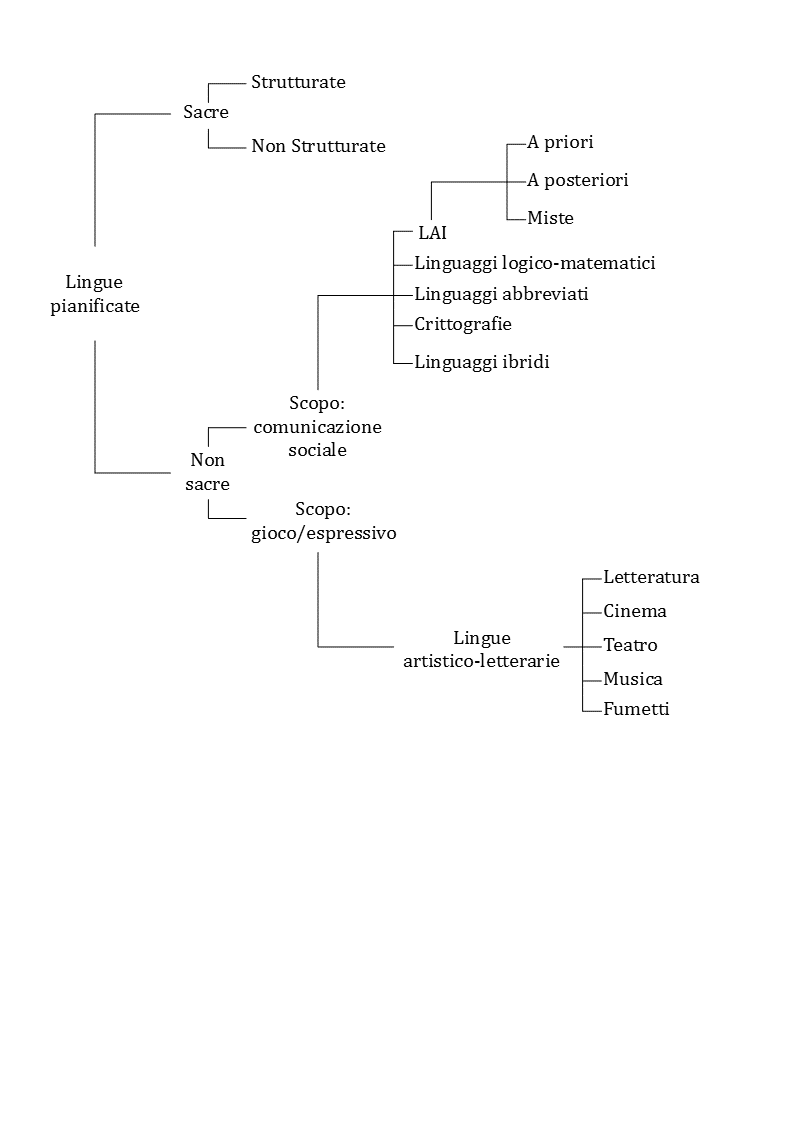

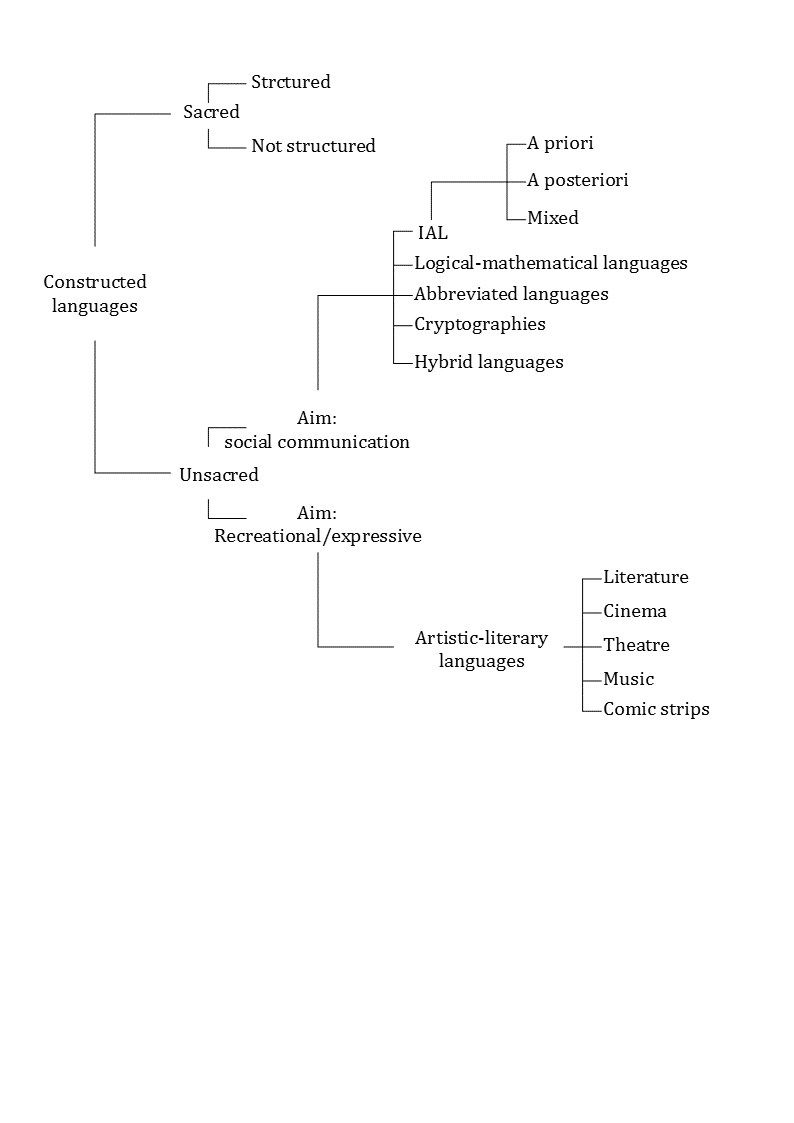

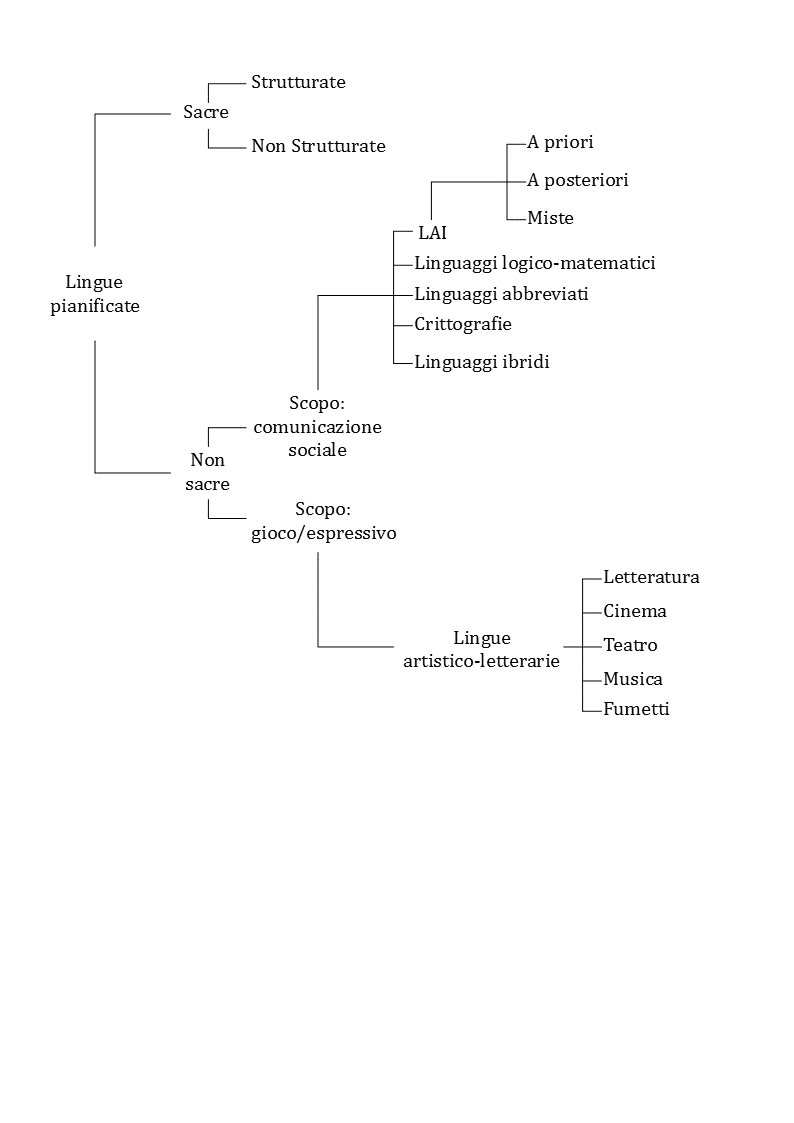

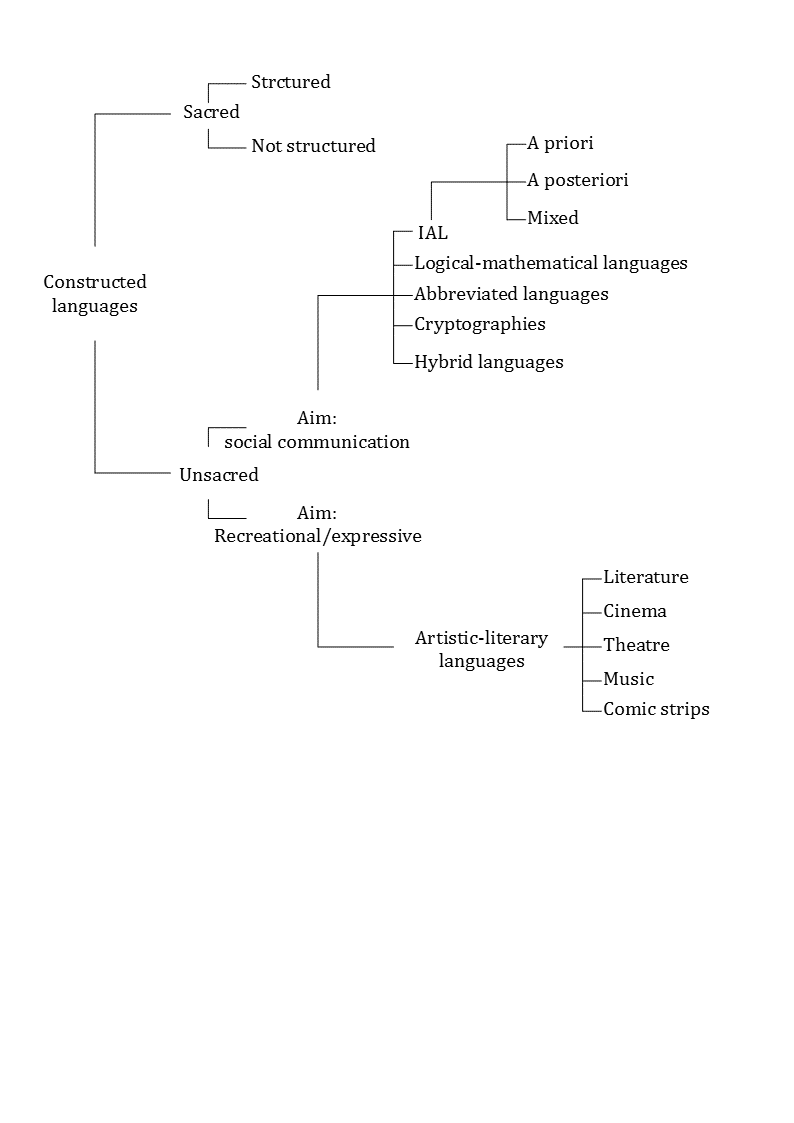

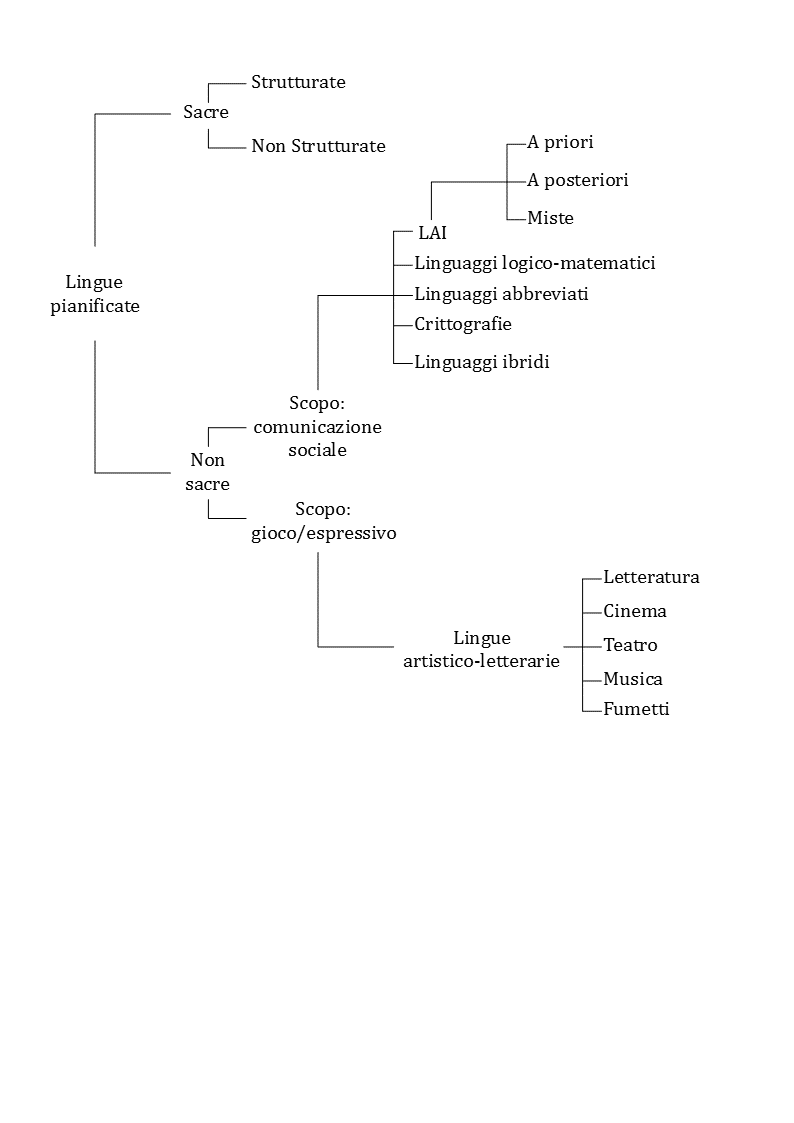

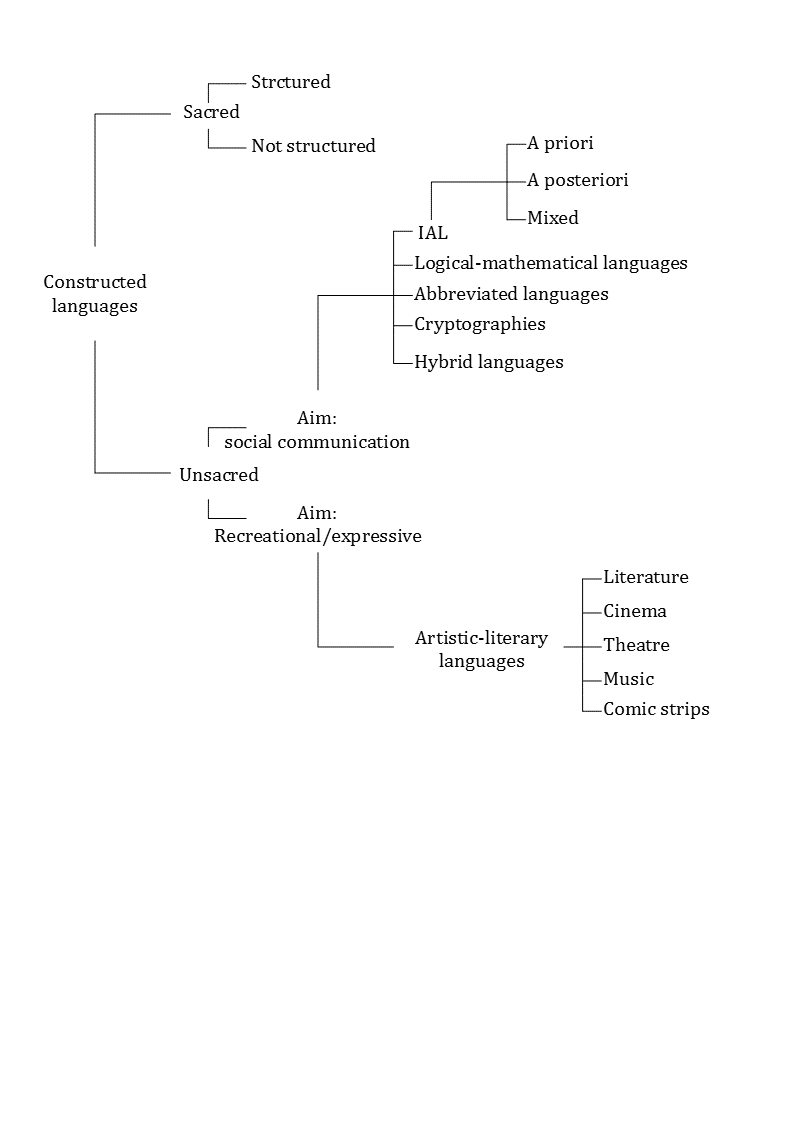

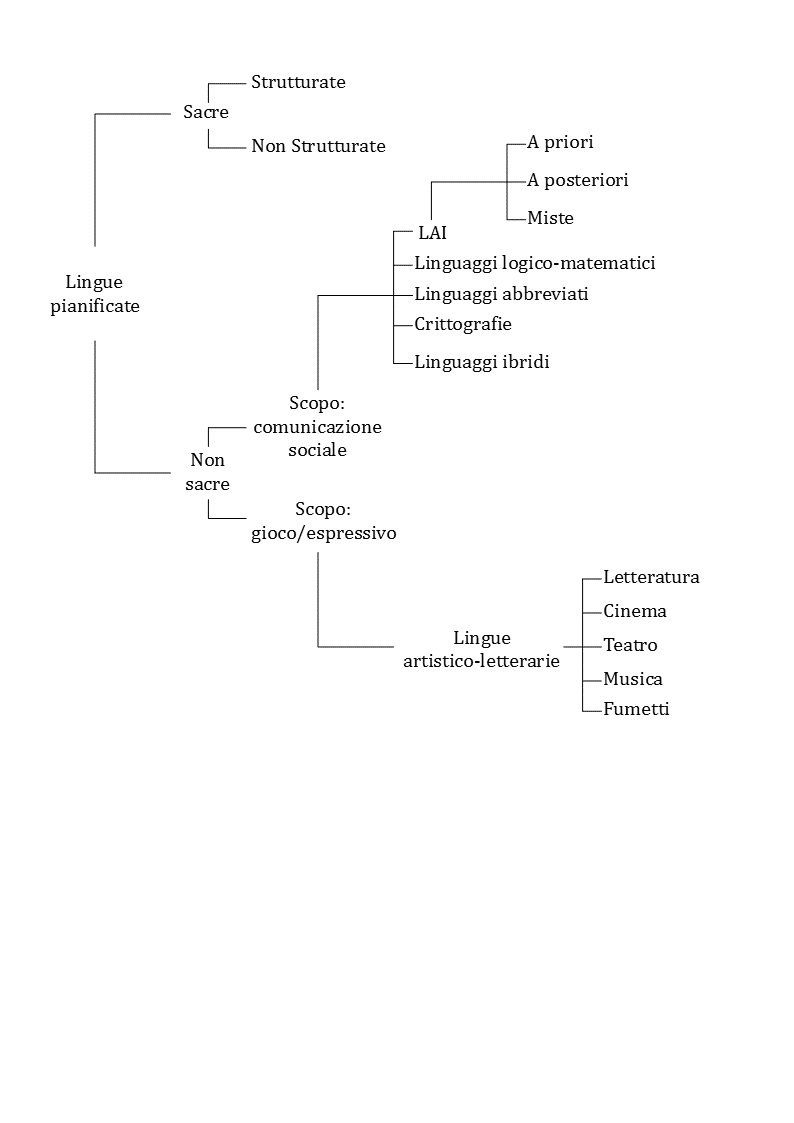

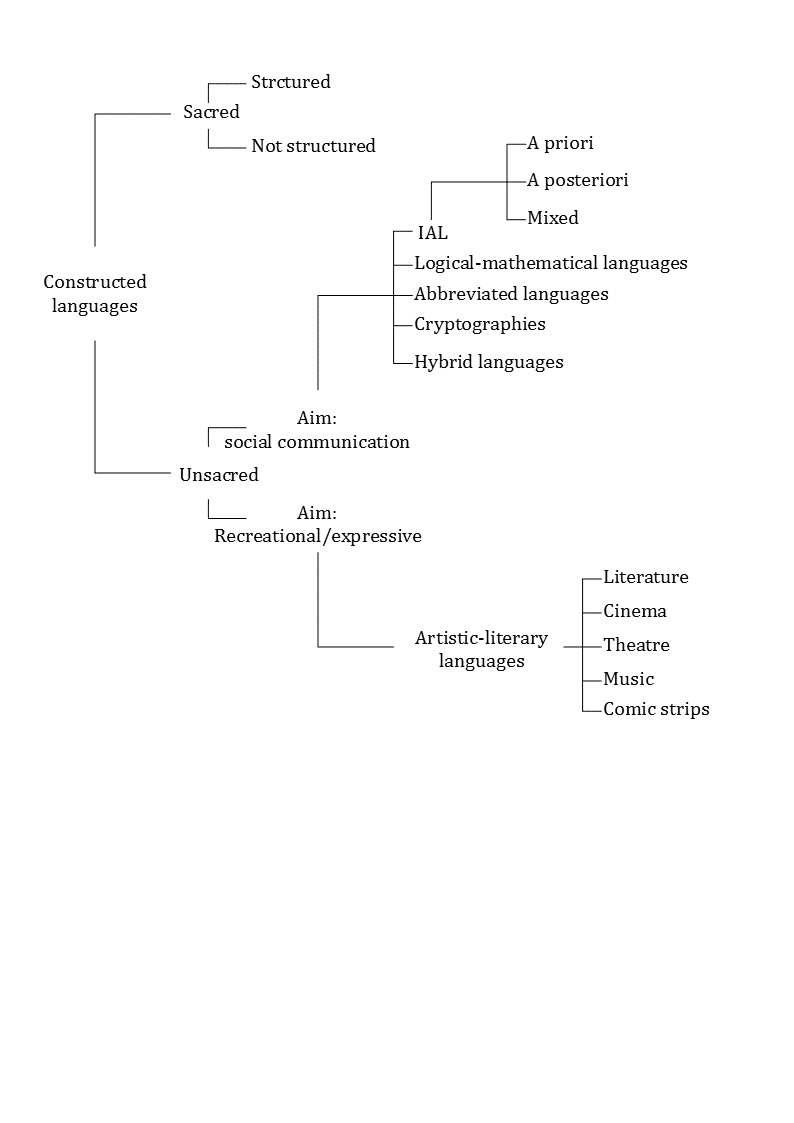

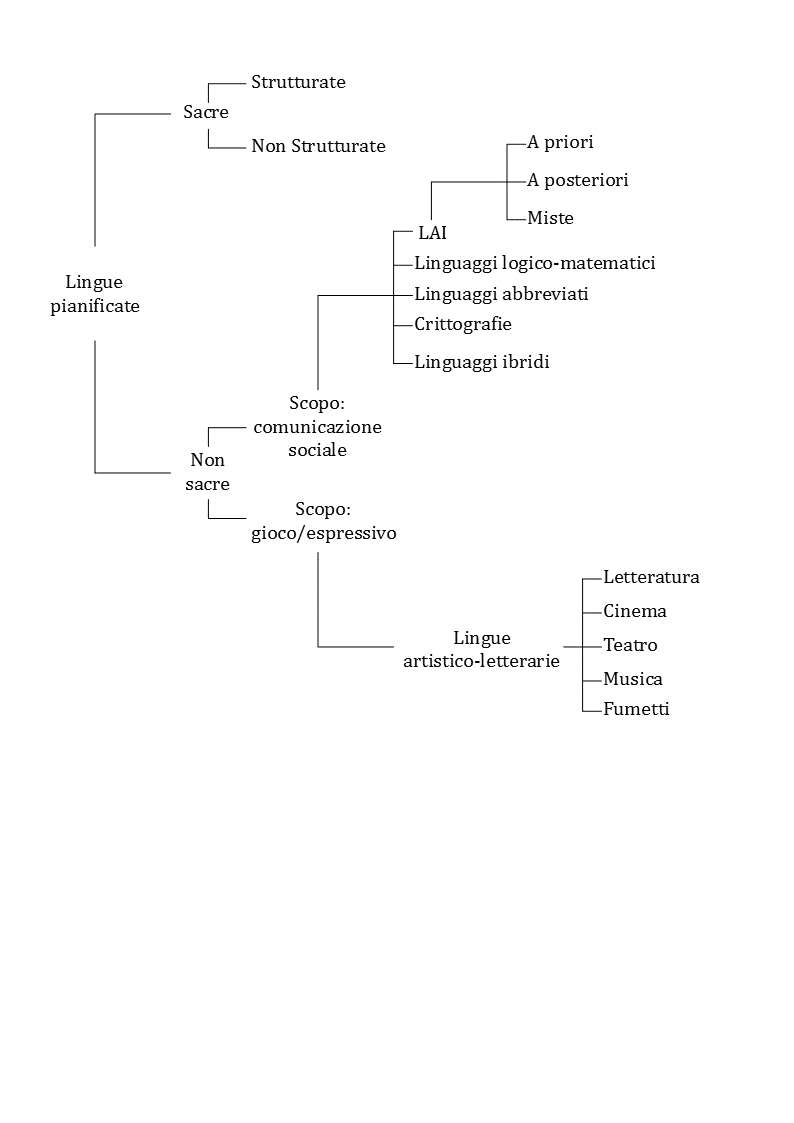

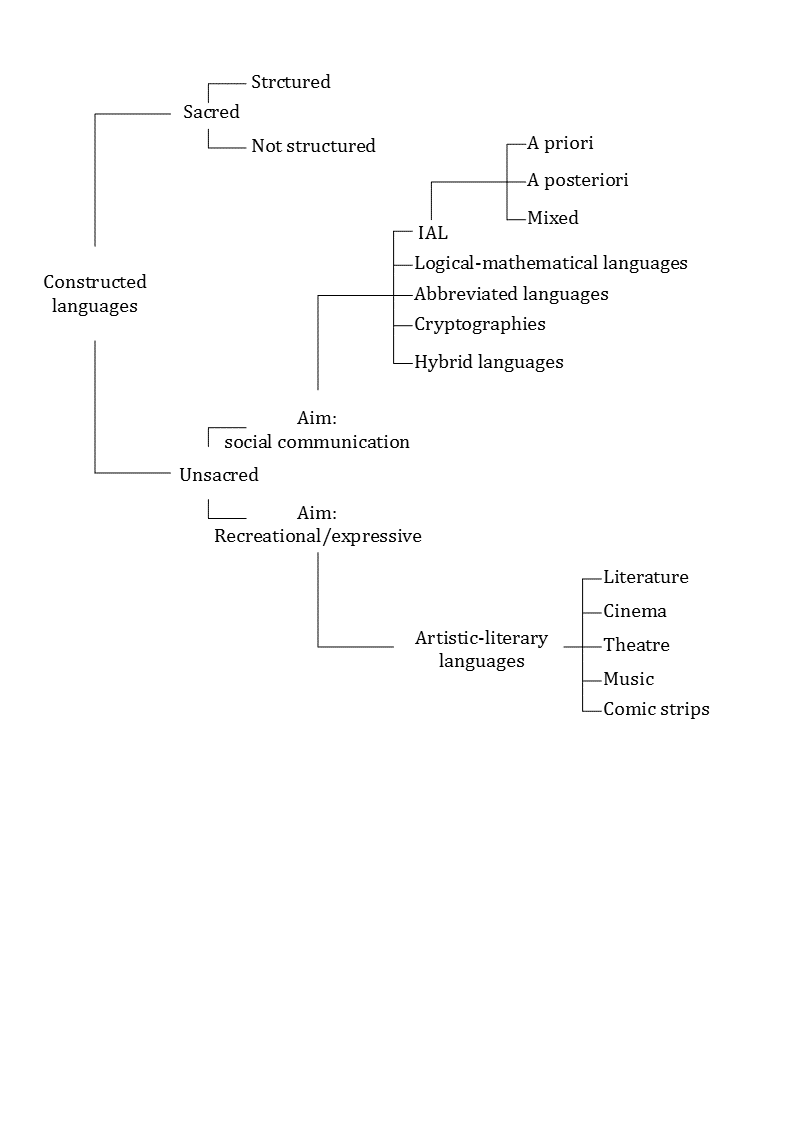

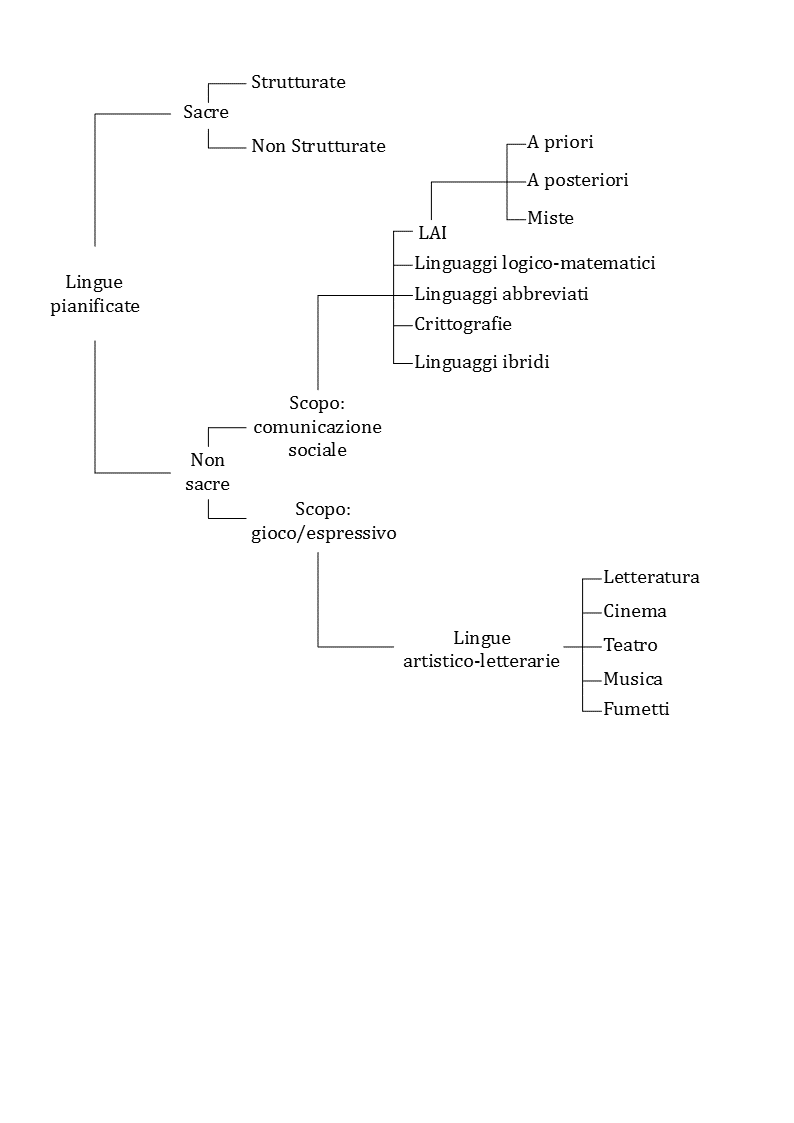

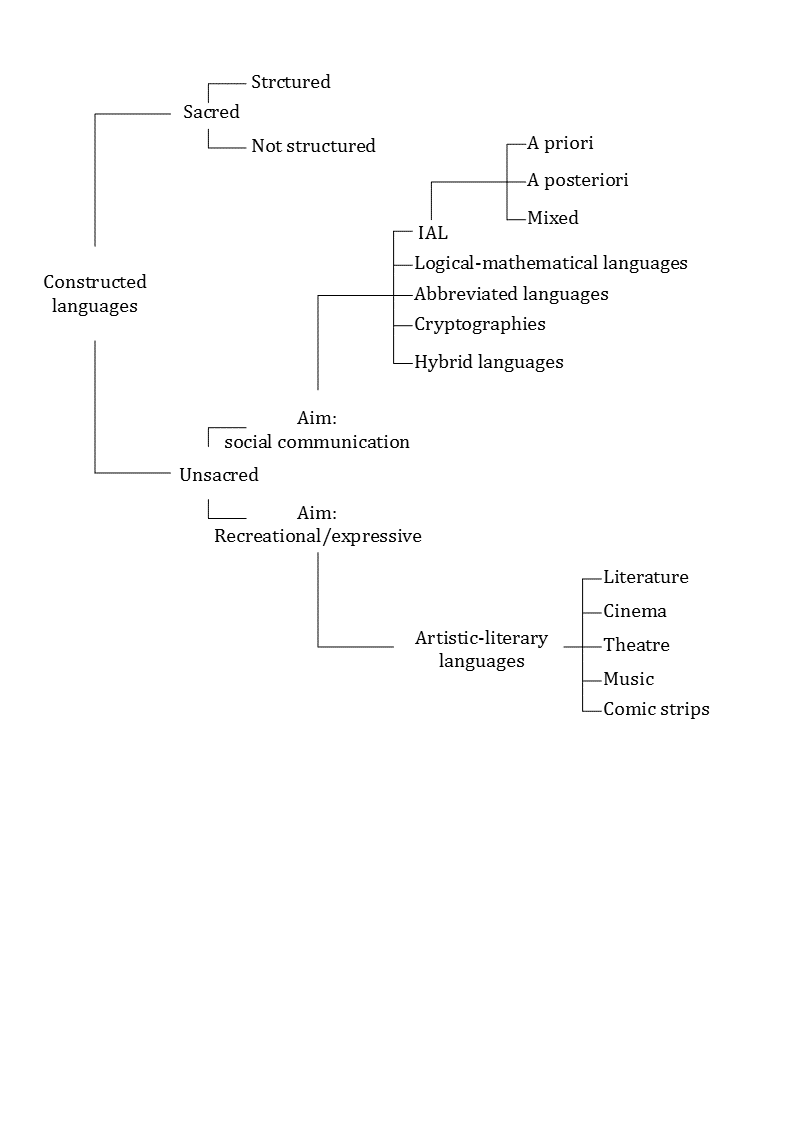

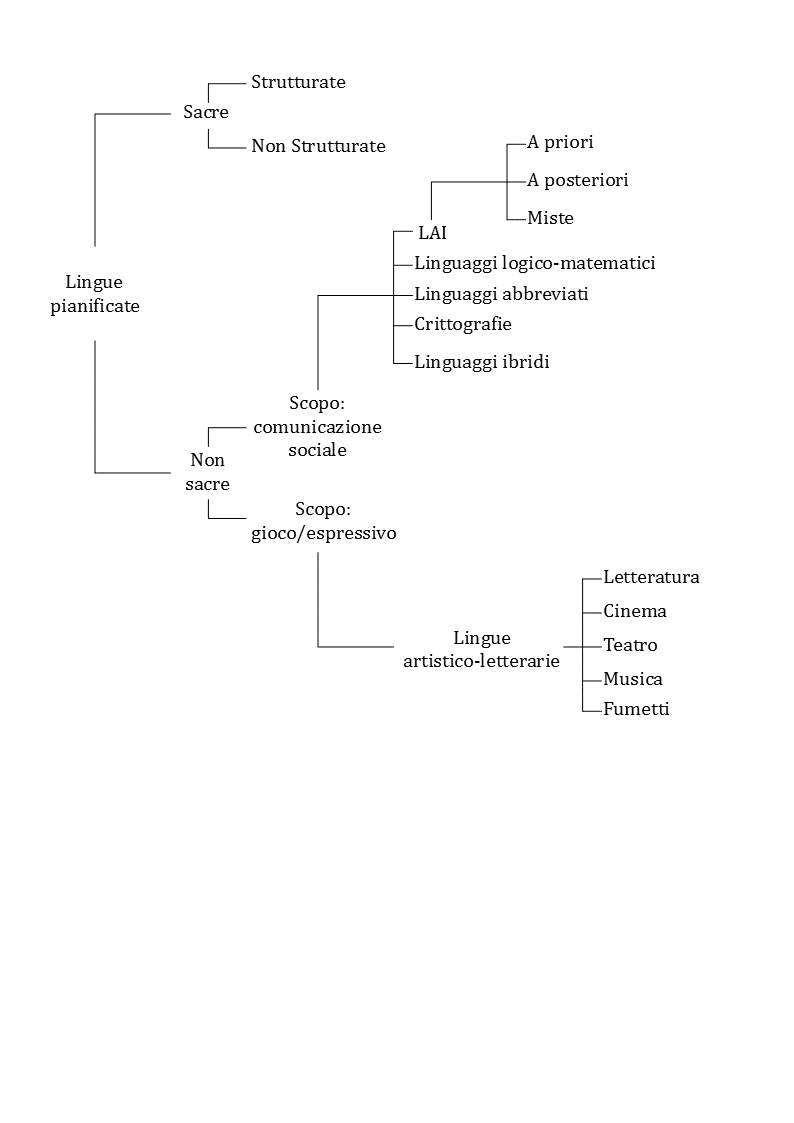

Chiarite queste tre differenze, per esemplificare la classificazione delle lingue

pianificate possono essere utili lo schema che segue, elaborato a partire dal

21

modello riportato in Aga Magéra Difúra (Albani & Buonarroti, 1994/2011, pp. 12-

13) e la sua successiva analisi.

Figure 1: Classificazione delle lingue pianificate – Schema rielaborato da Aga Magéra Difúra (Albani

& Buonarroti, 1994/2011, pp. 12-13)

Quando si studia una lingua pianificata, uno dei primi suoi aspetti da considerare è

il motivo per cui è stata creata, in quanto il fine determinerà, insieme ad altri

fattori, il risultato finale. Ecco dunque che si distinguono lingue sacre e non sacre;

come specificano Albani e Buonarroti (1994/2011), le prime permettono la

comunicazione con il divino, mentre le altre rientrano nella “tipologia che

comprende da un lato i progetti per la comunicazione a scopo sociale e dall’altro le

sperimentazioni più o meno artistiche motivate da un puro gioco espressivo” (p.8).

22

Facendo un breve accenno alle prime, le quali non saranno più trattate in seguito,

esse si suddividono in strutturate, come il balaibalan, e non strutturate, come le

glossolalie. Il balaibalan è una lingua pianificata creata negli ambienti mistici

islamici attorno al XV secolo, probabilmente da uno sceicco arabo. Quest’idioma è

considerato completo in quanto possiede una propria grammatica, una propria

sintassi e un proprio lessico, le cui parole sono per lo più di origine persiana e

turca. Alessandro Bausani la considera “la prima vera e propria lingua inventata del

mondo colto” (Bausani, 1954; Bausani, 1974, pp. 89 – 97, citato da Albani &

Buonarroti, 1994/2011, p.55). Le glossolalie sono invece pseudo-lingue inventate

semplicemente accostando tra di loro parole prive di senso; in ambito sacro e

religioso, come ci ricordano Albani e Buonarroti (1994/2011), si considerano

glossolalie i modi di parlare dei profeti in quanto essi non scelgono personalmente

le parole ma sono guidati in questo dallo Spirito Santo ed essi stessi non

comprendono ciò che dicono. Per il cristianesimo, la glossolalia è quindi un dono

grazie al quale il fedele ha la possibilità di parlare una lingua a lui sconosciuta.

Esempi di glossolalie sono preghiere di appartenenti al movimento religioso dei

pentecostali, oppure di missionari in tempi passati, oppure di medium in stato di

trance.

Au contraire, le lingue non sacre possono essere create a scopo di comunicazione

sociale o di gioco; siccome a entrambe queste categorie appartengono molti esempi

di lingue pianificate, è stata effettuata una selezione analizzando solo quelli ritenuti

più importanti.

Tra gli idiomi creati a scopo di comunicazione sociale, troviamo linguaggi ibridi

(per esempio i pidgin), le crittografie, i linguaggi abbreviati (stenografie), J’ai

linguaggi logico-matematici e le LAI, già accennate in precedenza. Queste ultime

possono essere definite a priori, a posteriori o miste. Tra quelle a priori troviamo le

lingue filosofiche, ovvero sistemi di segni convenzionali che hanno lo scopo di

eliminare le ambiguità e gli equivoci prodotti dagli idiomi naturali; per questo

motivo vengono spesso associate al termine “lingua perfetta” come ricorda

Umberto Eco (1996/2006): "[…] il sogno di una lingua perfetta è duro a morire, e

non mancano nel settecento progetti compiuti di lingue universali” (p. 315).

Cambiando categoria, troviamo le lingue a posteriori: un esempio molto conosciuto

23

è l’esperanto, lingua creata da Lejzer Ludovik Zamenhof a fine ‘800. Questo famoso

progetto di LAI è basato sulle lingue romanze, germaniche e slave, il che lo rende

appunto una lingua a posteriori, e ha avuto molto successo. Siccome tale lingua

sarà trattata più nello specifico in seguito, verrà ora presentato l’ultimo tipo di LAI:

le lingue miste, come il volapük. Anch’esso progetto di lingua internazionale e nato

quasi in concomitanza con l’esperanto, non condivide il suo successo in quanto è

risultato troppo complicato da comprendere ed è stato quindi abbandonato. ET

considerato un sistema misto in quanto si basa su inglese, tedesco e lingue latino-

romanze, ma possiede anche una caratteristica tipica degli idiomi a priori, c'est-à-dire

la scelta del suo creatore, Johann Martin Schleyer, di eliminare la “r” (cfr. cap. 1).

ensuite, si trovano i linguaggi logico-matematici (o linguaggi di

programmazione), anch’essi creati a scopo di comunicazione sociale. Si tratta di un

“insieme di caratteri che formano parole, espressioni, frasi e aggregati più ampi”

(Albani & Buonarroti, 1994/2011, p. 340) utilizzato in ambito informatico. Ces

particolari linguaggi sono caratterizzati da non ambiguità ed eseguibilità e hanno

una sintassi precisa e severa. Alcuni esempi sono il COBOL (COmmon Business

Oriented Language), codice creato nel 1959 con una grammatica molto vicina alla

lingua naturale inglese in quanto pensato appositamente per applicazioni in

ambito amministrativo e commerciale, o il più recente Java, emerso nel 1995 e più

“distante” dall’inglese nonostante questa lingua rimanga ancora alla sua base.

In seguito, troviamo i linguaggi abbreviati, ovvero sistemi di segni che svolgono la

funzione di surrogati linguistici delle lingue naturali. Un esempio molto comune

sono gli acronimi o le sigle come etc., prof., o UNESCO, ma rientra in questa

categoria anche la stenografia, una scrittura veloce e sintetica che si avvale di segni

e abbreviazioni per formulare parole. L’invenzione di questo codice è attribuita a

Marco Tullio Tirone, il quale utilizzò un sistema simile per annotare in modo

rapido le orazioni del suo patrono Marco Tullio Cicerone.

In qualche modo simile alla stenografia abbiamo la crittografia, ovvero la scrittura

segreta, utilizzata ovviamente per produrre un messaggio comprensibile solo a chi

conosca il codice utilizzato.

L’ultima voce da prendere in esame per quanto riguarda le lingue create a scopo di

comunicazione sociale è quella dei linguaggi ibridi: essi sono il risultato di una

24

miscela di varie lingue tra loro. L’esempio più comune è costituito dalle lingue

pidgin e creole, nate nel periodo del commercio triangolare e della tratta degli

schiavi. Esse sono frutto del contatto tra due o più idiomi diversi quali le lingue

degli schiavi, le lingue dei nativi e una lingua coloniale come spagnolo, portoghese,

francese, olandese, o inglese; la lingua coloniale è considerata “lessificatrice” per la

sua forte influenza sulla nuova lingua che sta nascendo. La differenza principale tra

pidgin e creolo è che quest’ultimo deriva dal primo; entrambi hanno origine

dall’incontro di varie lingue, ma nel momento in cui il pidgin inizia a essere parlato

dai nati delle nuove generazioni e la grammatica fortemente semplificata si evolve

verso forme più complesse, esso sarà definibile creolo. Nonostante questa

evoluzione, Toutefois, la lingua continuerà a rimanere piuttosto semplice. Alcune

località in cui si parlano oggi varietà di creolo, come specificano Albano e

Buonarroti (2011) sono le isole di Capo Verde, Haiti, le Antille o le isole Mauritius e

La Réunion.

Enfin, troviamole lingue non sacre create per scopo di gioco o espressivo: le più

diffuse sono quelle artistico-letterarie, che si sviluppano non solo in ambito

letterario, ma anche nel cinema, nel teatro, nella musica o anche nei fumetti. Di

solito sono idiomi creati per i generi fantasy o fantascientifico, in quanto danno

voce ad alieni o a comunità che vivono in luoghi immaginari. Due esempi già citati

sono il klingon e l’alto valyriano: entrambi creati per il cinema, hanno anche dei

testi a loro dedicati e sono dotati di sintassi e fonologia proprie e lessico specifico.

È importante notare che esso risulta molto diverso dall’una all’altra poiché l’alto

valyriano è utilizzato in un mondo fantasy ambientato in una sorta di Medioevo,

mentre il klingon è parlato da una razza aliena capace di costruire navicelle per

viaggiare nello spazio.

Queste sono le principali tipologie di lingue inventate esistenti; ce ne sarebbero

tantissime altre di cui parlare e per ognuna di esse si potrebbe scrivere un libro per

scendere nei particolari e analizzarla in modo preciso. Per questa trattazione si è

scelto di considerare soltanto l’alto valyriano poiché la serie televisiva Il Trono di

Spade è ormai molto seguita a livello mondiale, ma raramente i suoi fan prestano

attenzione al discorso linguistico, nonostante esso sia molto interessante da

studiare approfonditamente e offra diversi spunti di riflessione.

25

CAPITOLO 2

Nascita di una lingua

2.1 Processo di nascita e sviluppo di una lingua naturale

Le lingue naturali sono frutto di numerosi mutamenti che si verificano nel corso

del tempo. Quelle pianificate, Plutôt, sono create da uno o più inventori. In questo

capitolo sarà presentata l’analisi del modo in cui si verificano i mutamenti

linguistici e le conseguenze che ne derivano. Questi cambiamenti non avvengono

mai in modo improvviso, ma necessitano di molto tempo per affermarsi (Luraghi,

2006/2013). Difatti, i parlanti non si rendono conto che la loro lingua si sta

lentamente evolvendo; saranno i posteri ad accorgersi dei mutamenti avvenuti nei

secoli che, parfois, possono portare alla nascita di una nuova lingua. Ce

fenomeno è denominato “variazione diacronica” ed è oggetto di studio della

linguistica storica, che si occupa di studiare i cambiamenti delle lingue nel tempo e

le modalità in cui essi avvengono (Berruto & Cerruti, 2011).

Il mutamento linguistico può essere causato da diversi fattori, interni ed esterni

alla lingua stessa, fattori che possono essere di tipo ambientale, sociale, storico,

culturale, politico, demografico. I mutamenti possono essere di diversi tipi e

riguardare il suono, la morfologia, la sintassi, il lessico. Dal punto di vista fonetico,

avvengono,

per esempio,

fenomeni di assimilazione o dissimilazione.

L’assimilazione avviene quando un fono assume i tratti di un fono vicino e i due

foni diventano simili o uguali; per esempio, il latino noctem si è trasformato

nell’italiano notte, in cui la occlusiva velare sorda [k] diventa dentale come la [t],

occlusiva dentale sorda. La dissimilazione avviene quando in una parola due foni

simili o uguali non contigui diventano diversi come è successo, per esempio, Dans le

passaggio dal latino venenum all’italiano veleno.

I mutamenti morfologici hanno fatto sì che, nel passaggio dal latino all’italiano,

27

cadessero i casi e il genere neutro. Il mutamento sintattico riguarda l’ordine dei

costituenti della frase. In latino l’ordine è soggetto-oggetto-verbo; nelle lingue

romanze l’ordine è soggetto-verbo-oggetto. Il mutamento lessicale avviene con

fenomeni di arricchimento del lessico, che possono verificarsi in vari modi: escroquer

l’ingresso nella lingua di neologismi, cioè di nuovi lessemi, oppure con i

meccanismi che permettono la formazione di parole nuove, come la derivazione o

la composizione. Un ulteriore possibilità è l’apporto da altre lingue, che può

avvenire sotto forma di prestito o di calco. I lessemi si possono anche perdere, escroquer

il passare del tempo. Alcune parole latine sono state abbandonate, come cunctus

(tutto intero); anche alcune parole italiane sono state abbandonate nel corso del

tempo come, per esempio, la parola donzello (Berruto & Cerruti, 2011).

Oltre a quella diacronica, esistono altre dimensioni di variabilità che influenzano

anch’esse lo sviluppo delle lingue. La variazione diatopica consiste nella presenza

di varianti linguistiche in relazione allo spazio. In Italia, per esempio, exister

diversi modi per definire lo stesso oggetto. Si tratta di varietà regionali dal punto di

vista lessicale. Per esempio, l’appendiabiti può essere chiamato “attaccapanni”,

oppure “ometto”, oppure “appendino”, a seconda del luogo geografico di

référence.

Esistono anche delle varietà grammaticali che riguardano l’uso dei tempi e dei

modi verbali come, per esempio, l’uso del passato remoto o del congiuntivo nelle

varie regioni del nord, del centro e del sud Italia. Aussi, esistono delle varietà

fonologiche, soprattutto per quanto riguarda i dialetti.

La variazione diafasica riguarda invece le varianti in base al contesto d’uso della

lingua. In ogni idioma si possono distinguere vari registri, quelli formali e quelli

informali, e in ciascuno di essi i parlanti si esprimono in modo diverso. En italien,

per esempio, il verbo “fare” in un contesto formale è spesso sostituito dal sinonimo

“effettuare”; pur non cambiando il significato, il secondo verbo è più adatto a un

registro formale che non il primo.

La variazione diastratica è la presenza di varianti a seconda dello strato sociale di

appartenenza del parlante. Più il ceto è basso, più egli tenderà probabilmente a

utilizzare il dialetto al posto dell’italiano, il quale, se eventualmente parlato,

risulterà comunque influenzato dal vernacolo. Al contrario, se il parlante

28

appartiene a uno strato sociale alto avrà un accesso più facile all’istruzione e ciò

comporterà una maggiore competenza nell’utilizzo della lingua standard.

Esiste infine la variazione diamesica, vale a dire la presenza di varianti della lingua

in base al mezzo di produzione usato. Nella forma scritta c’è la tendenza a

utilizzare un tipo di linguaggio più formale e burocratico. Nel parlato invece,

generalmente il linguaggio è più informale e colloquiale, nonostante si usi, dans

determinati contesti, anche un linguaggio formale.

Ciascuna di queste varietà è importante e contribuisce alla variazione diacronica;

essa infatti non avverrebbe se non esistessero, già in fase sincronica, ovvero in un

determinato arco temporale, diverse varianti della stessa lingua. La variabilità

viene definita mutamento nel momento in cui una varietà è accolta. Essa quindi

può affermarsi e diffondersi fino a contribuire al cambiamento dell’idioma di

partenza.

Nonostante le varianti sincroniche, Toutefois, le lingue attraversano dei periodi di

stabilità. Generalmente se un idioma gode di elevato prestigio subirà modifiche in

tempi più lunghi, mentre una lingua parlata da pochi si evolverà in tempi più

ristretti. Il prestigio di una lingua dipende da vari fattori: sarà alto se la lingua in

questione è ufficiale a livello nazionale, se è letteraria, cioè se esiste una

produzione letteraria in quella lingua, e se si insegna a scuola. Solitamente le lingue

più stabili sono quindi quelle ufficiali che si parlano a livello nazionale come

italien, l’inglese, il francese e via dicendo. Anch’esse però tendono al

cambiamento, soprattutto al giorno d’oggi in cui i parlanti di ogni Stato sono

costantemente in contatto con altre lingue e culture, fattore che facilita

enormemente il mutamento linguistico.

Un altro aspetto molto utile per stabilire il livello di prestigio di una lingua è

costituito dalla forma di governo dello Stato in cui si parla l’idioma in questione. Se è

presente un centro politico unitario e coeso la lingua tenderà a essere più stabile,

mentre nel caso di frammentazione sarebbe invece favorito il mutamento linguistico.

Il latino, per esempio, non ha subito sostanziali mutamenti per secoli proprio perché

era parlato da una comunità unitaria e coesa con un forte centro politico unificatore.

Toutefois, nel momento in cui l’Impero è crollato e questo centro si è disgregato, le

diverse varianti hanno iniziato ad affermarsi e diffondersi rapidamente, finché si è

29

giunti al mutamento del latino che si è trasformato nelle lingue romanze. Le varianti

che si sono affermate nei vari luoghi esistevano già da tempo, ma non avevano forza

sufficiente per imporsi; è stato necessario il crollo dell’Impero Romano per far sì che

le variazioni presenti nel latino si trasformassero in mutamenti.

Se non ci fossero dunque varianti in un determinato arco temporale non

avverrebbe alcun cambiamento nel tempo. La presenza di queste varietà è dovuta a

molteplici motivi.

Generalmente le lingue tendono a semplificarsi con il passare del tempo. I casi latini, par

exemple, sono stati abbandonati dalle lingue romanze e la sintassi si è semplificata.

Anche le differenze lessicali regionali italiane sono dovute a cause politiche, sociali e

culturali. È quindi lecito riproporre l’esempio precedente sulle varianti della parola

“appendiabiti”: il motivo della loro esistenza è da ricercarsi nel fatto che l’Italia è stata

per secoli una nazione estremamente frammentata con la presenza di vari centri

politici. Ciascuno di essi costituiva un polo politico e culturale quasi a sé stante, donc

ha avuto ripercussioni sulla lingua che ha preso una direzione più o meno diversa per

ogni regione. (Luraghi, 2006/2013; Gensini, 1988/1992)

I mutamenti sono dunque la causa principale della nascita di nuove lingue, maman

alcune possono prendere vita in un modo diverso, ovvero attraverso il contatto

linguistique. Ne sono un esempio perfetto le lingue creole e i pidgins, lingue di

contact.

Se il mutamento diacronico porta alla nascita di una nuova lingua, potrà causare

anche la morte di quella precedente che, dopo essersi evoluta e trasformata, verrà

abbandonata.

Tali processi sono difficilmente prevedibili e solo a posteriori ci si renderà conto che si

sono accumulate nel tempo così tante differenze da rendere la lingua antica

incomprensibile, nonostante essa sia la base di quella nuova. C’è comunque un margine

di tempo in cui si può capire che la fine di una lingua è vicina: secondo l’Unesco, quando

essa non è più appresa da almeno il 30% dei parlanti come prima lingua, allora è

destinata a morire. A questo punto qualsiasi tentativo di recupero sarebbe poco

fruttuoso, perché se un idioma muore significa che non possiede prestigio e che i

parlanti non sono interessanti a mantenerlo in vita (Luraghi, 2006/2013).

30

2.2 Processo di creazione e sviluppo di una lingua pianificata

Una lingua naturale richiede secoli per formarsi e in realtà non ha mai un punto di

arrivo, se non temporaneo, in quanto continuerà a mutare nel tempo. Una lingua

pianificata, Plutôt, nasce grazie a un atto di creazione consapevole e non deriva da

una lingua precedente; ciò non significa, Mais, che la nascita delle lingue pianificate

non attraversi una serie di passaggi. Il processo si divide in due fasi principali, la

prima delle quali è la glottopoiesi: con questo termine si indica “la fase di

costruzione a tavolino del nucleo strutturale della lingua da parte del glottoteta”.

Durante questa fase egli ha il compito di decidere “la grammatica della lingua a

tutti i livelli – fonetica, morphologie, sintassi – e il dizionario di base” (Gobbo, 2009,

p. 72); alla fine di questo momento il glottoteta avrà creato una “lingua progetto”

(Blanke,1985, citato da Gobbo, 2009).

In questa prima fase il glottoteta inizia a codificare un modello semiformale della

lingua che vuole pianificare e ciò che creerà sarà la varietà standard dell’idioma.

Ciò significa che, se la si considerasse naturale, questa variante coesisterebbe

probabilmente insieme a uno o più dialetti. Compito del glottoteta è anche quello di

elaborare un lessico e trovare un modo affinché la sua creazione venga acquisita

dai futuri e ipotetici parlanti. Questi ultimi due passaggi in particolare sono molto

influenzati dalla L1 dell’inventore, cioè dalla sua lingua madre, fenomeno che

avviene inconsapevolmente e che prende il nome di “effetto Bausani” (Gobbo,

2009, p. 73).

A questo punto inizia il secondo momento della creazione delle lingue pianificate,

detto “fase della vita semiologica”, termine suggerito da Ferdinand De Saussure.

L’idioma creato è stato accettato dai parlanti, i quali iniziano a utilizzarlo nella

communication; ciò significa che il glottoteta creatore ha perso ogni potere di

controllo nei confronti della lingua, che “avrà il carattere di trasmettersi in

condizioni che non hanno alcun rapporto con quelle che l’hanno costituito […]. […]

la lingua è entrata nella sua vita semiologica, e non si può più tornare indietro: que

si trasmetterà per via di leggi che non hanno niente a che fare con le leggi di

creazione” (De Saussure, 1970, p. 42, citato da Gobbo, 2009, p. 74).

Toutefois, è facile intuire che non tutte le lingue pianificate raggiungono questa fase

31

di vita semiologica; per fare un esempio, è sufficiente pensare a una qualunque

delle lingue create per scopi letterari, come l’alto valyriano. Esso possiede sì

morphologie, sintassi e fonetica, ma non viene parlato se non nel mondo fantastico

per il quale è stato concepito.

Questo discorso però non riguarda esclusivamente questo tipo di lingue: anche

alcune LAI non hanno raggiunto la condizione di vita semiologica, nonostante siano

state concepite per uno scopo ben preciso e reale; un esempio, già menzionato in

precedenza, è il Latino sine Flexione di Giuseppe Peano.

Per tutte le lingue che invece raggiungono la condizione di vita semiologica, il loro

processo di sviluppo non è ancora concluso. È infatti a questo punto che ha inizio

l’arduo compito di diffondere la lingua affinché si crei una comunità di parlanti in

grado di trasmetterla alle generazioni future. È dunque di vitale importanza far sì

che essa raggiunga il maggior numero di parlanti possibile ed esistono vari modi

per cercare di realizzare quest’obiettivo; si possono organizzare congressi, fondare

società che abbiano come scopo proprio quello di diffondere la lingua, redigere

manuali di grammatica nel nuovo idioma per dare la possibilità ai nuovi parlanti di

apprenderla e tradurre testi letterari conosciuti.

Oggigiorno l’avvento di Internet fornisce ai glottoteti desiderosi di diffondere la

loro lingua una grande possibilità di successo, attraverso blog, pagine, siti o video.

Internet si è rivelato utile non solo per la diffusione, ma anche per la creazione di

nuovi idiomi. En fait, tra il diciannovesimo e il ventesimo secolo, il numero di

persone che proponevano una lingua pianificata, creata come progetto di LAI, par

scopi letterari o ludici, è aumentato sempre di più.

Il 29 luglio del 1991 ebbe luogo il primo raduno di creatori di lingue e venne creato

il primo listserv apposta per loro, che fu chiamato Conlang Listserv. Conlang è un

termine coniato dalla prima radice di constructed (pianificato) e language (lingua)

e ben presto il termine conlang divenne il più utilizzato per riferirsi alle lingue

pianificate (Peterson, 2015, pp. 11-12). Grazie a questa piattaforma e ai vari metodi

per entrare in contatto tra loro, i conlanger, coloro che creano lingue, iniziarono

come mai prima di quel momento a scambiarsi idee, opinioni e consigli per creare e

diffondere i loro progetti.

32

Il processo di sviluppo delle lingue pianificate non è uguale per tutti gli idiomi e

differisce a seconda del motivo per cui essi vengono creati.

Se il glottoteta ha intenzione di fornire ai parlanti che non condividono lo stesso

codice una lingua che permetta loro di comunicare in modo semplice, cioè una LAI,

allora probabilmente il suo progetto sarà di una lingua a posteriori, ovvero basata

su idiomi già esistenti. Il glottoteta dovrà ricordarsi che la sua lingua dovrà essere

piuttosto semplice in modo da poter essere appresa in poco tempo e senza troppe

difficoltà da parlanti provenienti da diverse aree linguistiche. Un glottoteta che

invece avesse il compito, o il desiderio, di creare una lingua pianificata per la

letteratura o lo spettacolo, incontrerebbe ostacoli di tipo diverso. La sua lingua

potrebbe essere creata a priori, cioè senza basarsi su alcuna lingua già esistente,

dato che dovrebbe essere usata da una popolazione immaginaria. Una delle

maggiori sfide però, sarebbe quella di cercare di rendere la lingua il più verosimile

possibile e di legarla alla cultura del popolo fittizio; la lingua infatti è sempre

strettamente connessa all’ambiente culturale e sociale. David Peterson descrive

perfettamente questa situazione quando commenta la creazione della lingua

dothraki per lo show televisivo Il Trono di Spade. Essendo i Dothraki una

popolazione di nomadi piuttosto barbara, gli sceneggiatori richiedevano una lingua

che suonasse “dura”, proprio perché essa doveva in qualche modo rispecchiare la

comunità dei suoi parlanti (Peterson, 2015, pp. 25-26).

Saranno ora analizzate le modalità in cui sono state create due lingue tra loro molto

diverse, proprio per sottolineare le diverse metodologie utilizzate: il celebre

esperanto, una LAI creata per il mondo reale, e l’alto valyriano, creato invece per la

letteratura e il cinema.

2.2.1 Una lingua pianificata per il mondo reale (l’esperanto)

L’esperanto è una lingua pianificata nata come progetto di LAI nella seconda metà

del XIX secolo. Il suo ideatore, il dottor Louis-Lazare Zamenhof, pubblicò

autonomamente, non avendo trovato un editore disponibile a farlo, il suo primo

pamphlet adottando lo pseudonimo di Doktoro Esperanto, da cui deriva il nome

dell’idioma (Couturat & Leau, 2006).

Il testo fu pubblicato nel 1887, ma l’esperanto esisteva già da tempo. Il dottor

33

Zamenhof, en fait, già durante gli anni del ginnasio aveva iniziato a dedicarsi alla

pianificazione di quella che sarebbe diventata in futuro la più conosciuta tra le LAI.

Continuò a sviluppare il suo progetto nel corso dei sei anni di università: non solo

creò lessico e grammatica, ma si dedicò alla traduzione e alla composizione di testi

mentre si esercitava anche a pensare in lingua, arricchendola e perfezionandola.

Come narrato da Zamenhof stesso in una lettera spedita a Nikolai Borovko, la culla

dell’esperanto è la città di Białystok, la stessa in cui egli trascorse l’infanzia. Essa

era abitata da russi, polacchi, tedeschi ed ebrei e il giovane Zamenhof riteneva di

poter risolvere le tensioni presenti grazie alla creazione di una lingua neutra che

facilitasse la comunicazione. Avendo quindi ben presente lo scopo di una lingua

ausiliaria, iniziò a elaborare una grammatica semplificata, dopo aver abbandonato

l’idea iniziale di restaurare una lingua morta risalente all’età classica. Per quanto

riguarda il vocabolario scelse di attingere a quello romano-germanico e slavo,

inserendo molte parole internazionali; questo rende dunque l’esperanto una lingua

a posteriori.

L’alfabeto si compone di 27 lettere, di cui 5 vocali e 22 consonanti, alle quali si

aggiunge la semiconsonante “ŭ”, corrispondente alla u breve. Gli unici dittonghi

previsti sono aŭ e eŭ, mentre tutte le altre vocali vengono pronunciate

separatamente. Ogni fonema può essere pronunciato in un solo modo. L’accento si

trova sempre sulla penultima sillaba. È presente un unico articolo determinativo,

“la”, invariabile sia per genere sia per numero, mentre non sono previsti l’articolo

partitivo né quello indefinito.

Anche il sistema numerico è molto semplice: i numeri cardinali sono invariabili e

conoscendo i termini da “uno” a “dieci”, più “cento” e “mille”, sarà possibile formare

tutti gli altri numeri. È infatti sufficiente elencare ciascuna unità che compone il

nombre, in ordine dalla maggiore alla minore; per esempio, 2457 si scrive dumil

(duemila) kvarcent (quattrocento) kvindek (cinquanta) sep (sette). Per formare i

numeri ordinali basta aggiungere la desinenza “a” ai numeri cardinali.

La vocale finale permette di distinguere il ruolo di ciascuna parola all’interno del

discours:

La “-i” caratterizza i verbi all’infinito; essi sono invariabili per numero e persona,

dunque la coniugazione risulta uniforme. Per poter distinguere i tempi verbali

34

gli uni dagli altri è sufficiente osservare la desinenza: se il verbo termina con “-

as” sarà al presente, con “-is” al passato, con “-os” al futuro, con “-us” al

condizionale e con “-u” all’imperativo o al congiuntivo.

La “-o” caratterizza i sostantivi al nominativo singolare; per formare il plurale è

sufficiente aggiungere una “-j”, mentre per passare al caso accusativo (l’unico

esistente oltre al nominativo), singulier ou pluriel, è necessario aggiungere la “-

n” al nominativo. Non esistono altri casi, che sono sostituito da preposizioni.

La “-a” caratterizza gli aggettivi al nominativo singolare; essi devono sempre

essere accordati con il sostantivo al quale si riferiscono in numero e in caso,

mentre il genere è invariabile. La formazione del plurale e dell’accusativo

avviene come per i sostantivi.

La “-e” caratterizza gli avverbi derivati, mentre quelli primitivi o le preposizioni

terminano spesso con il dittongo “-aŭ”.

La costruzione della frase non segue regole troppo severe pur non essendo

eccessivamente libera, in modo da evitare sia equivoci che scaturiscono dall’ordine

delle parole, sia l’assenza di eleganza e logica. Generalmente si raggruppano le

parole della stessa proposizione separandole mediante la virgola da quelle di altre

proposizioni; in questo modo esse non s’intrecciano tra loro, dunque non nascono

equivoci.

Di solito l’ordine della frase è soggetto – verbo – complemento oggetto –

complementi indiretti, ma data la quasi assenza di regole è possibile cambiare la

disposizione.

Per la scelta del vocabolario, Zamenhof ha escogitato un modo per renderlo

relativamente semplice e il più internazionale possibile. È riuscito a ridurlo a un

nucleo ristretto di radicali ai quali è sufficiente aggiungere determinati suffissi

invariabili per formare le parole. Questi radicali sono stati scelti secondo il

principio dell’internazionalità, cioè selezionando solo quelli che comparivano più

volte in diverse lingue europee; in questo modo Zamenhof è riuscito a favorire il

maggior numero di parlanti possibile.

I radicali possono essere suddivisi in tre categorie. La prima comprende quelli

internazionali per le lingue europee, si riferiscono per lo più all’ambito scientifico e

sono di origine greca o latina. Nella seconda categoria si trovano i radicali solo

35

parzialmente internazionali; ma comunque condivisi dalla maggior parte delle

lingue europee. Nella terza e ultima categoria si trovano infine i radicali non

internazionali, che Zamenhof ha scelto tra quelli usati dalle persone colte. Ha

inserito anche in questa categoria vari radicali di origine slava o germanica, par

garantire maggiormente la parità tra le lingue. I radicali di origine latina, en fait,

hanno più degli altri carattere di internazionalità e sono quindi molto presenti

nelle prime due categorie; in questo modo Zamenhof ha trattato in modo

imparziale le lingue europee.

Zamenhof era consapevole del fatto che un uomo da solo non può creare una lingua

perfetta e che ogni idioma, anche pianificato, se è utilizzato da una comunità di

parlanti è destinato a cambiare nel tempo. Lasciò quindi che il pubblico utilizzasse

e sviluppasse la lingua, senza pretendere di averne il controllo. Seppur con qualche

difficoltà iniziale, l’esperanto cominciò a diffondersi lentamente a partire dalla

Russia. Dimostra l’interesse verso l’esperanto la fondazione a San Pietroburgo, Dans le

1892, della società Espero.

Nacque in seguito il primo giornale esperantista, La esperantisto, che assunse un

ruolo fondamentale nella diffusione della lingua.

Per incoraggiarne l’utilizzo vennero pubblicati manuali, traduzioni di classici come

l’Amleto, l’Iliade o le Nozze di Figaro e vari adepti s’impegnarono affinché

l’esperanto si diffondesse il più possibile. Colui che contribuì maggiormente fu

Louis de Beaufront, un filologo molto noto. Egli stava elaborando, grazie a un

lavoro che stava durando da più di dieci anni, un’altra lingua pianificata:

l’adjuvanto, che scoprì essere molto simile all’esperanto. De Beaufront si rese conto

che la sua lingua era meno precisa, per alcuni aspetti, rispetto a quella di

Zamenhof, così la abbandonò per dedicarsi all’esperanto. Grazie a lui l’idioma si

diffuse in Francia, con la fondazione del mensile L’Esperantiste e della Societé Pour

la Propagation de l’Esperanto (Couturat & Leau, 2006).

Dopo più di un secolo, l’esperanto continua ad avere successo e il suo uso non

accenna ad arrestarsi: esistono manuali in varie lingue, riviste, società di

propaganda e siti web, come risulta dal sito della Federazione Esperantista Italiana

(http://www.esperanto.it/).

36

Nonostante l’esperanto abbia riscosso un notevole successo, ha anche ricevuto un

certo numero di critiche. La prima di esse ha come destinatario l’alfabeto. Et

rimprovera all’esperanto di avere troppe lettere accentate, che creano confusione nel

lettore, costituiscono dei suoni difficili da imparare e comportano delle difficoltà

nella scrittura. Per esempio, il fonema corrispondente alla lettera ĥ è arduo da

pronunciare per i francesi. I problemi di questo genere vanificano tutti gli sforzi di

Zamenhof per rendere la lingua il più internazionale possibile. Altre critiche sono

state mosse contro aspetti che in realtà sono più positivi che negativi: alcuni non

hanno apprezzato, per esempio, la distinzione delle parti del discorso che avviene

grazie alla desinenza in finale di parola. Questa è, Plutôt, una caratteristica che rende

la lingua comoda e semplice da imparare perché permette innanzitutto di

riconoscere a colpo d’occhio il ruolo di ciascuna parola nella proposizione e in

secondo luogo di formare le parole in modo meccanico (Couturat & Leau, 2006).

2.2.2. Una lingua pianificata per la finzione letteraria (alto valyriano)

L’alto valyriano è una lingua pianificata da David Joshua Peterson per la serie

televisiva Il Trono di Spade, basata sui libri dello scrittore americano George

Raymond Richard Martin.

David Peterson ha recentemente dato un importante contributo al mondo della

pianificazione linguistica, non solo per aver creato varie lingue, ma anche per

essere uno dei fondatori della Language Creation Society. Si tratta di

un’organizzazione creata per promuovere le lingue pianificate e farle conoscere al

pubblico. Tale società riveste inoltre un ruolo di intermediazione tra coloro che

vogliono avvalersi di lingue pianificate nei loro lavori (che possono essere la

scrittura di libri o di sceneggiature cinematografiche) e chi si occupa di crearle.

Tra le varie lingue create da Peterson, oltre all’alto valyriano e al dothraki, le più

importanti e famose sono l’indojisnen, l’irathient, il castithan e il kinuk’aaz per la

serie televisiva Defiance e lo shiväisith per Thor: The Dark World. A differenza del

dottor Zamenhof, Peterson non ha mai creato un progetto di LAI e i suoi idiomi

sono tutti destinati al mondo fantasy o fantascientifico.

La prima comparsa dell’alto valyriano è avvenuta nel corso della terza stagione

della serie televisiva Il Trono di Spade, nel 2013, mentre il dothraki aveva già avuto

37

il suo debutto nella prima stagione. I produttori David Benioff e Daniel Brett Weiss

affidarono a Peterson il compito di pianificare l’alto valyriano nel 2012, Malgré

lui avesse già iniziato a svilupparne un progetto nel 2009.

Non trattandosi di una LAI, come lo è l’esperanto, Peterson non era legato a

particolari vincoli per quanto riguarda la semplicità e la neutralità; la sua lingua,

dopotutto, non ha né ha avuto, sin dall’inizio, lo scopo di agevolare la

comunicazione tra parlanti di diversa nazionalità. Toutefois, quello di Peterson non

è stato un lavoro totalmente libero, poiché lo scrittore George R. R. Martin aveva già

creato delle espressioni in alto valyriano che era essenziale rimanessero tali. Par

questo motivo Peterson scelse di iniziare a partire dalla grammatica, Malgré

fosse sua abitudine, come da lui stesso dichiarato in The Art of Language Invention,

cominciare dalla fonologia di una lingua (Peterson, 2015).

Perché potesse lavorare al progetto di elaborazione del dothraki, George Martin gli

aveva fornito un elenco di parole da lui create, per un totale di 56, compresi 24 nomi

propri. Per l’alto valyriano, al contrario, il numero era molto ristretto: 6 parole più un

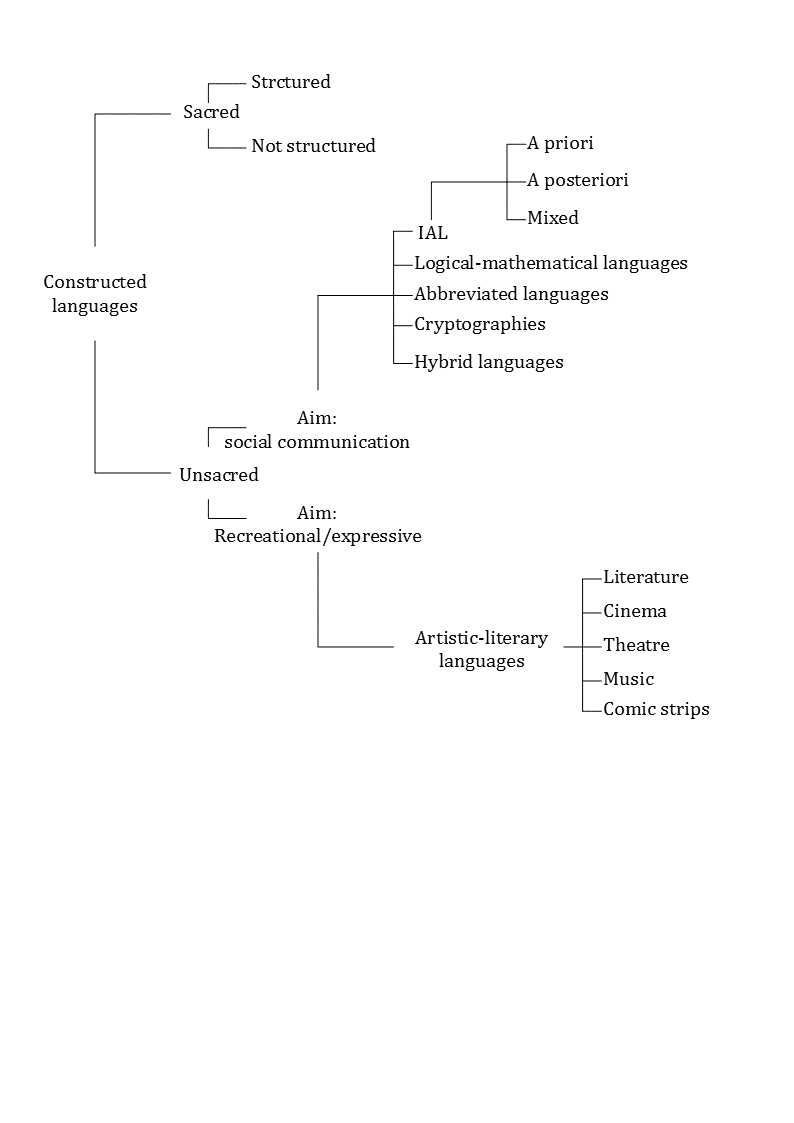

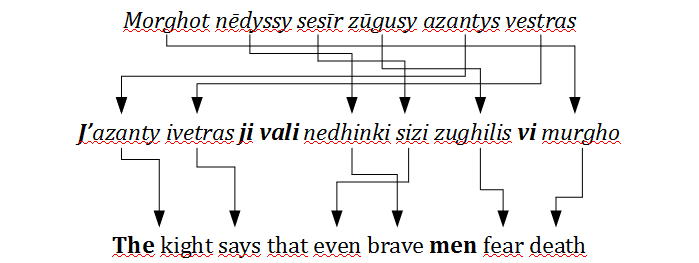

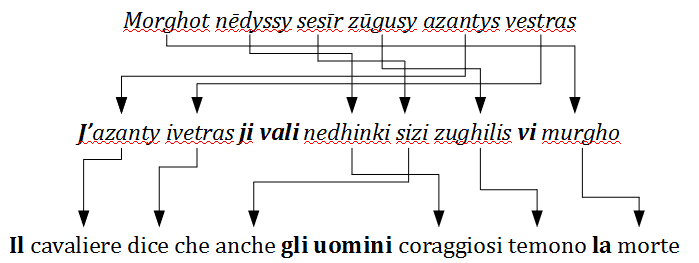

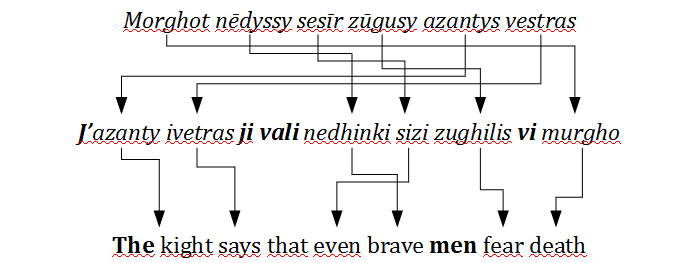

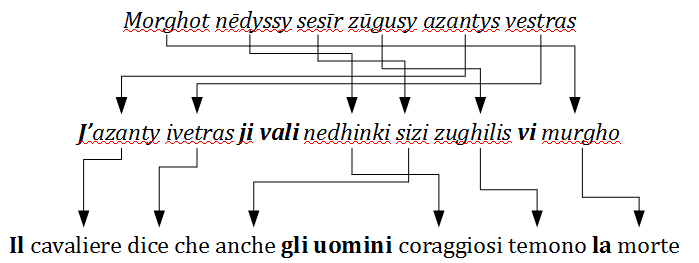

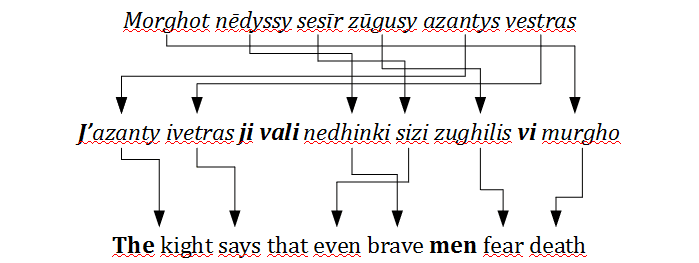

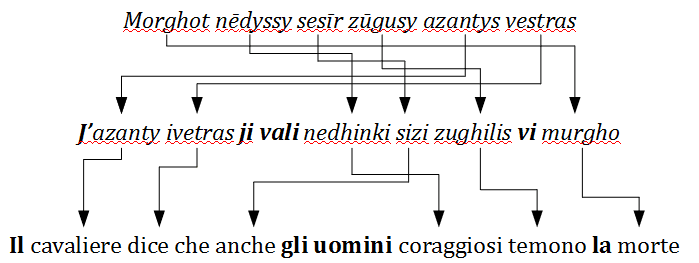

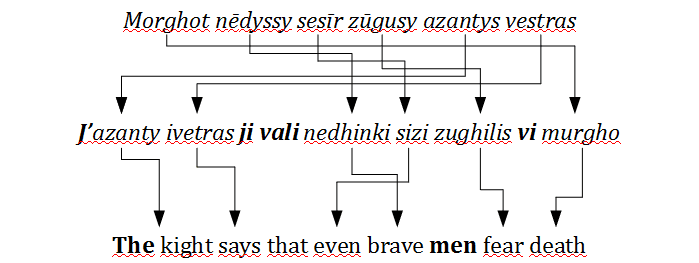

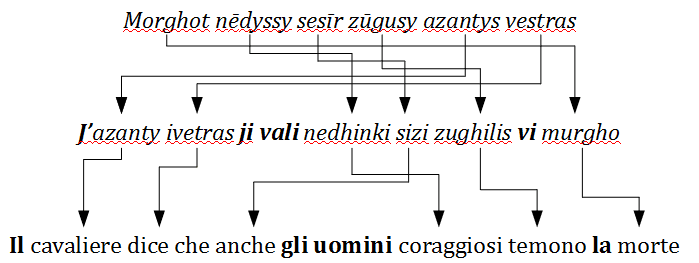

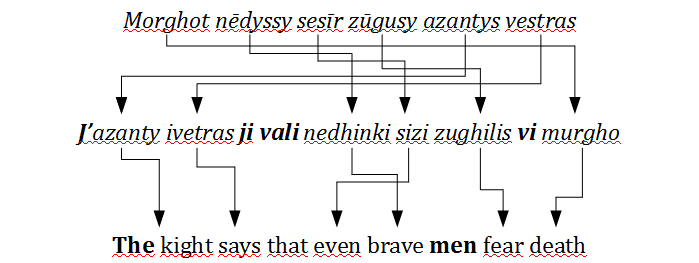

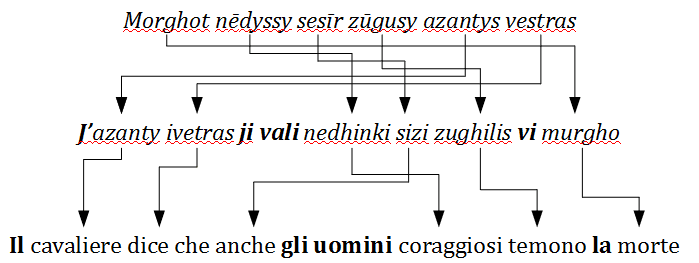

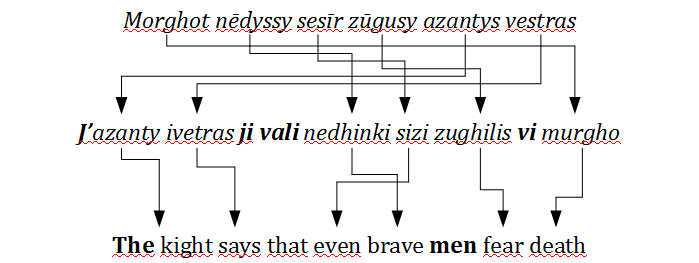

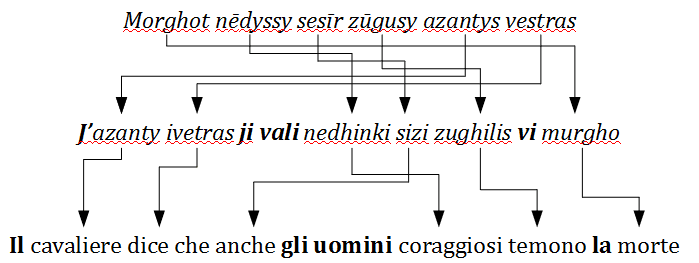

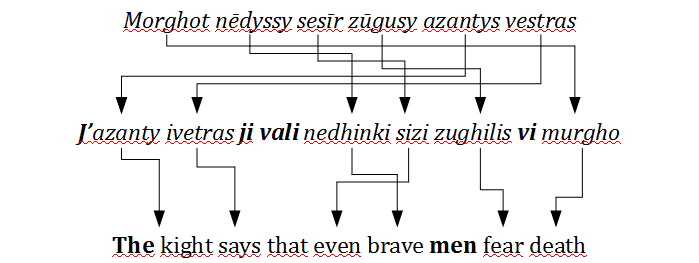

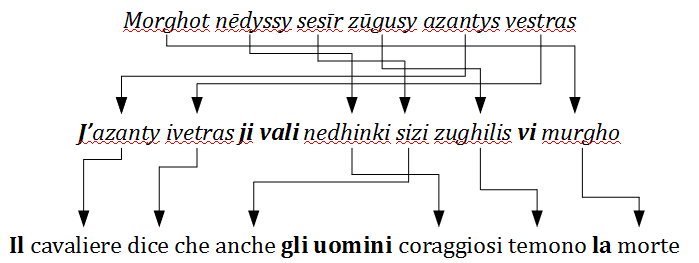

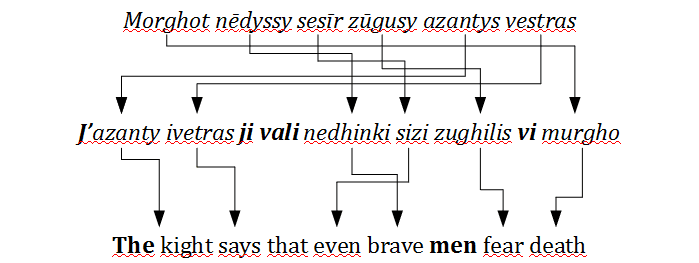

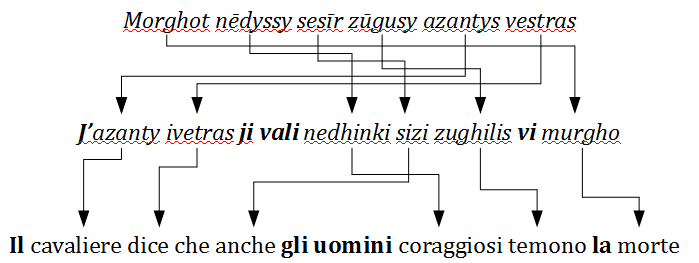

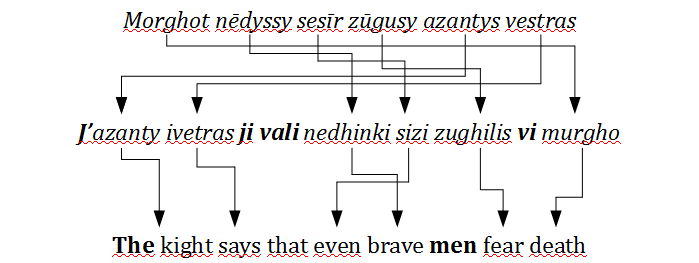

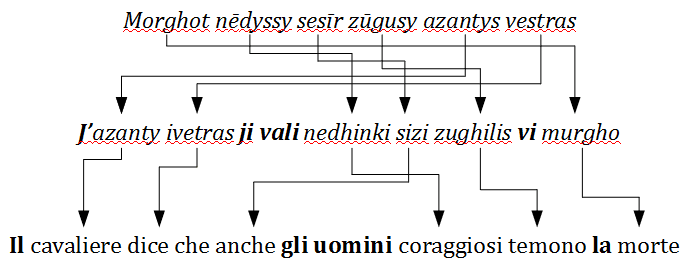

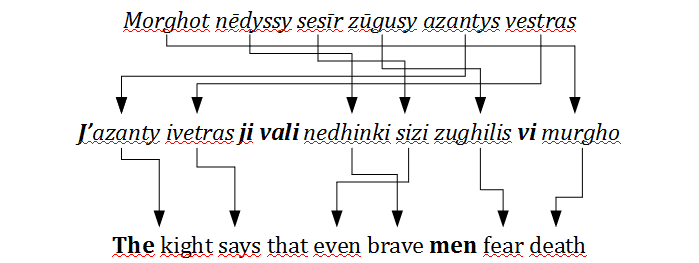

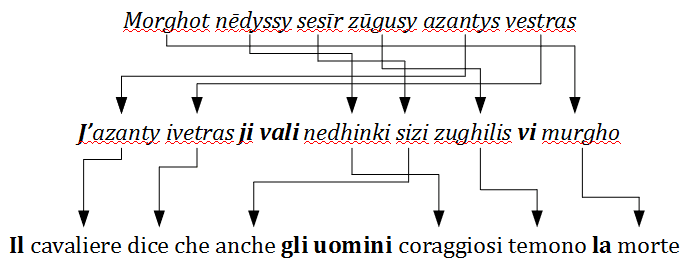

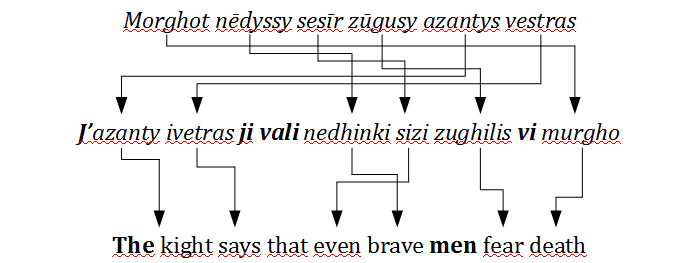

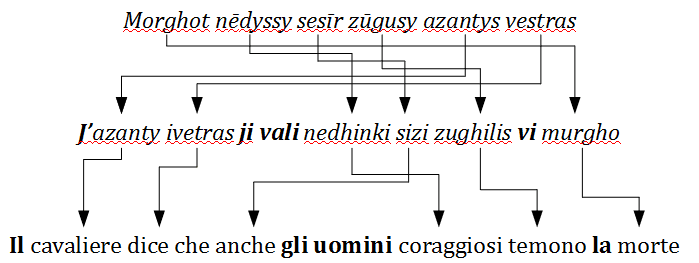

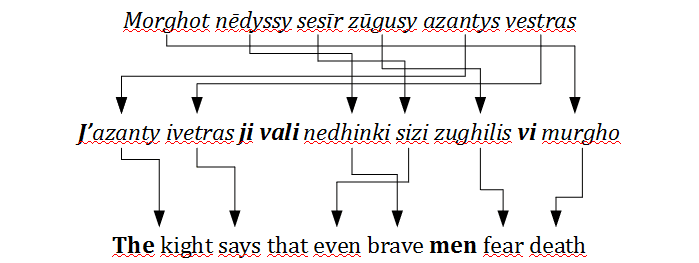

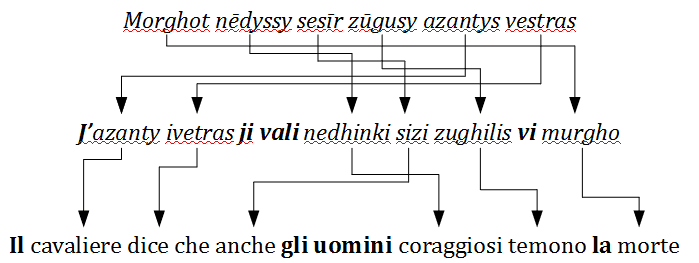

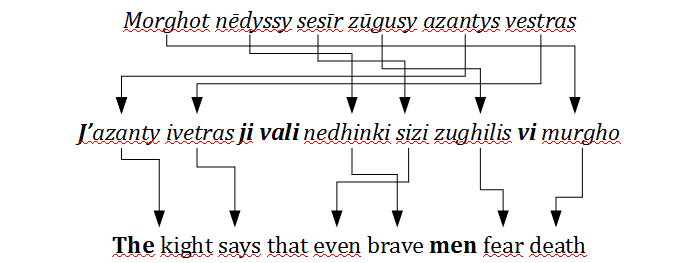

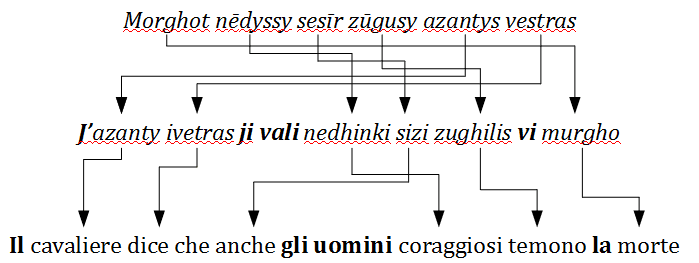

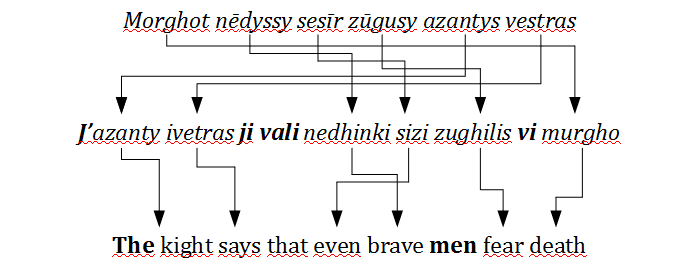

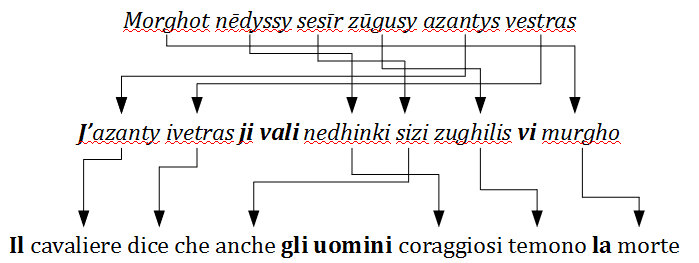

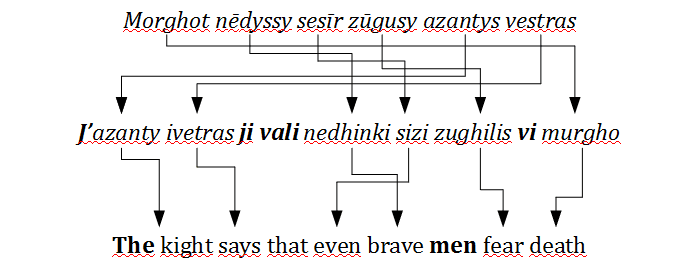

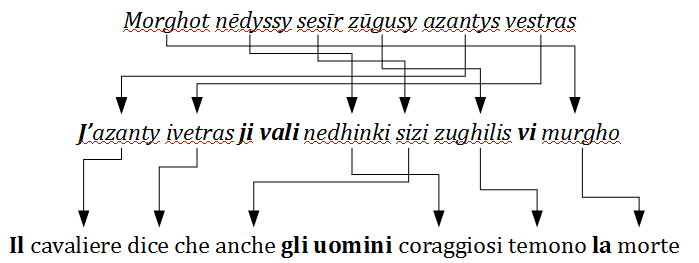

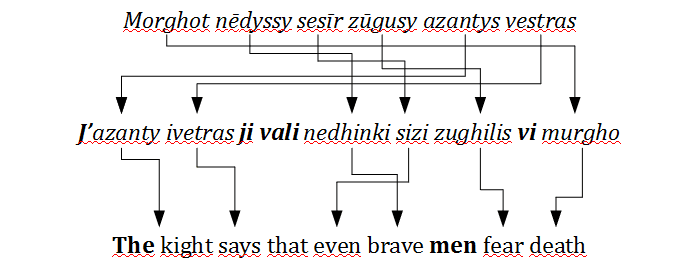

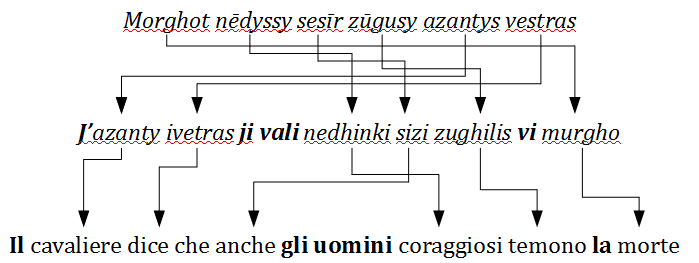

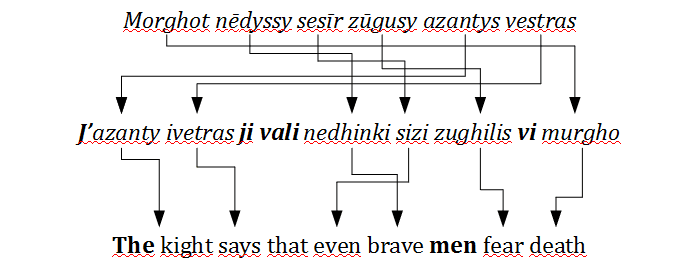

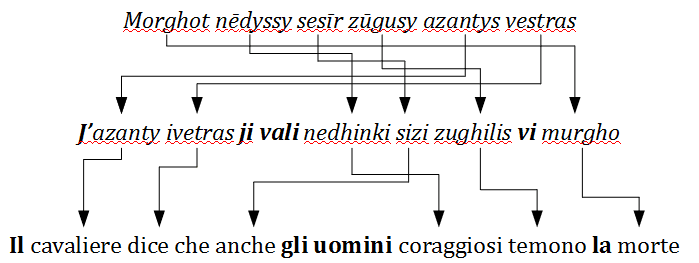

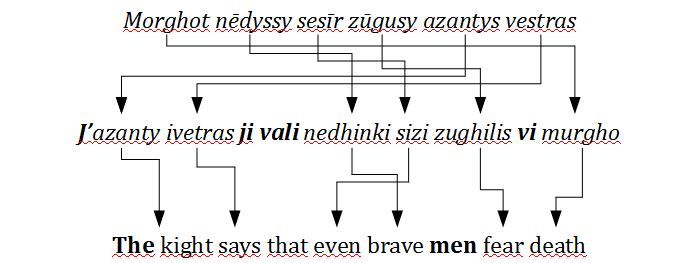

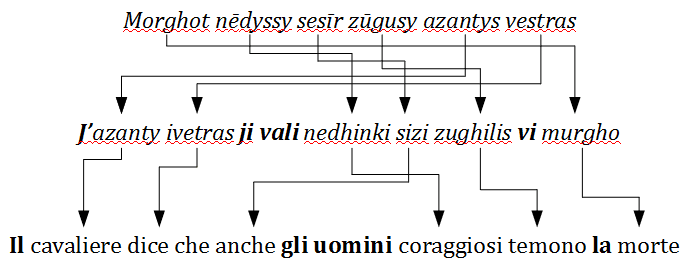

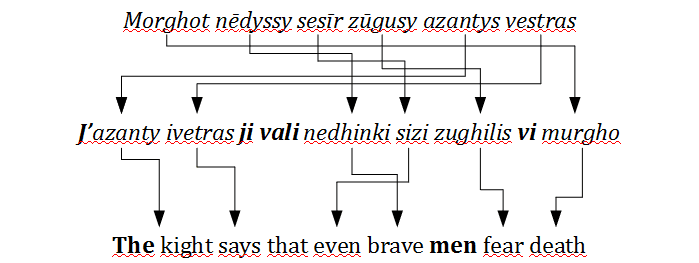

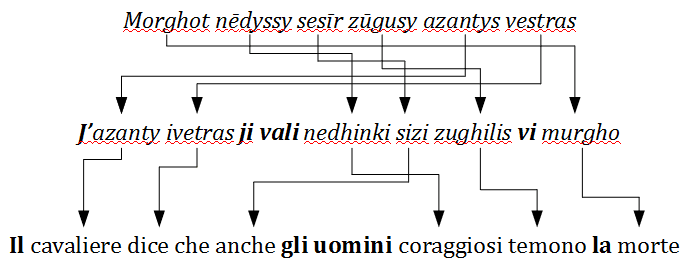

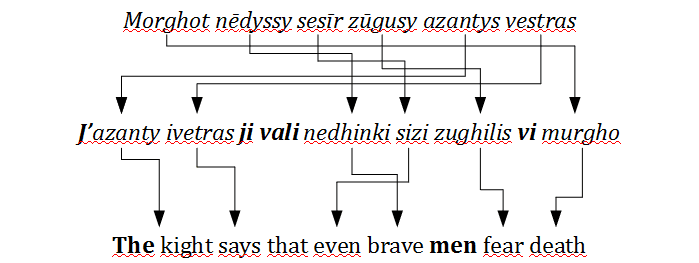

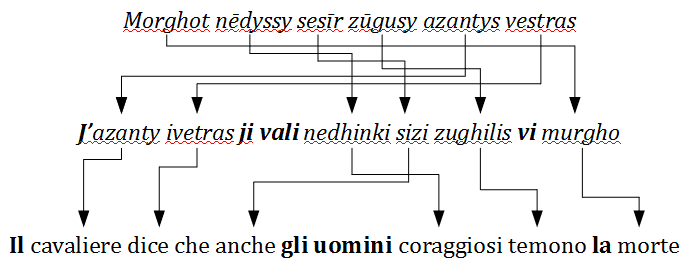

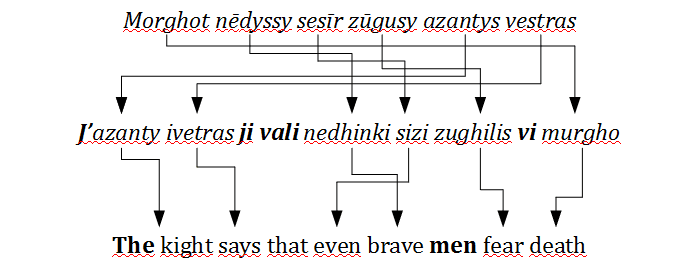

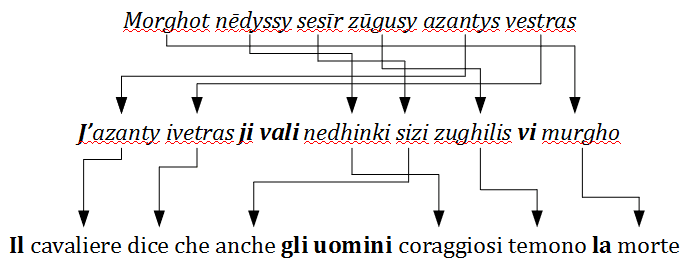

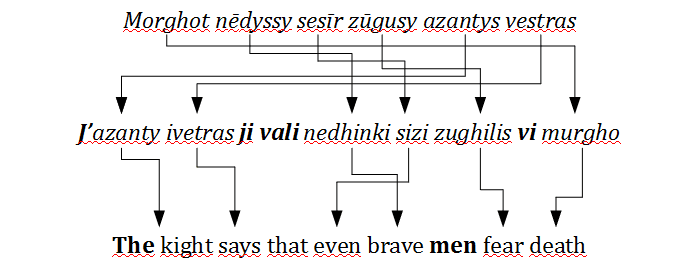

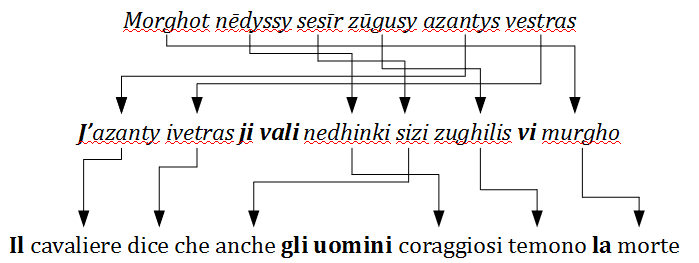

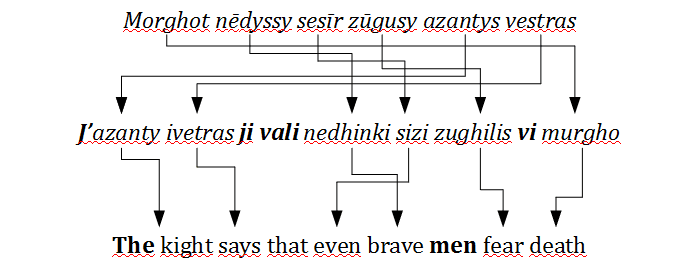

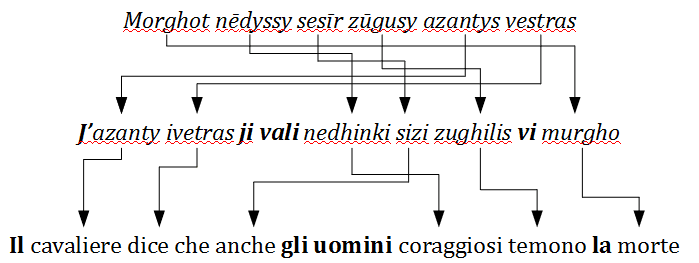

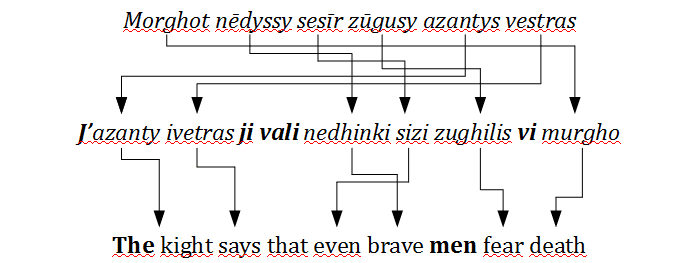

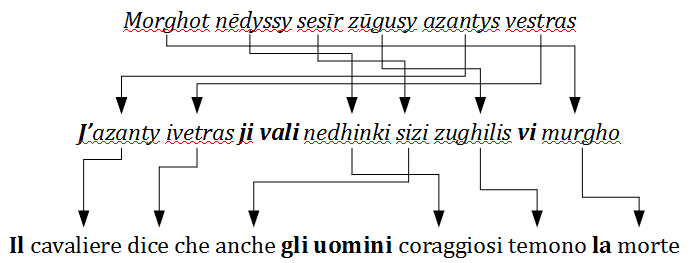

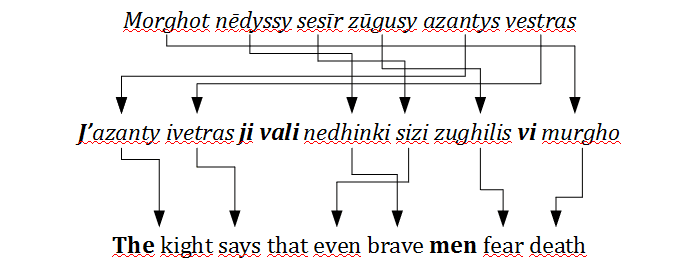

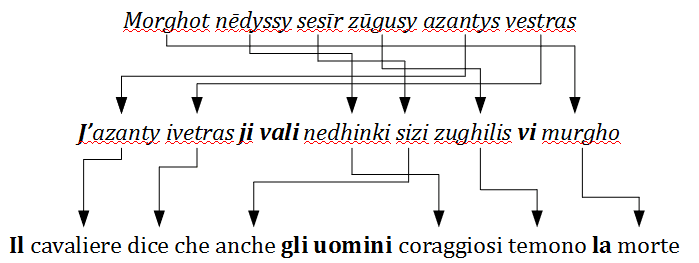

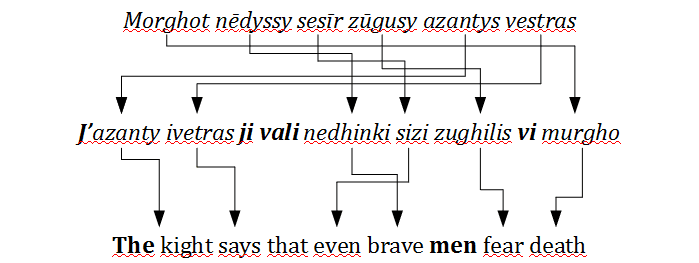

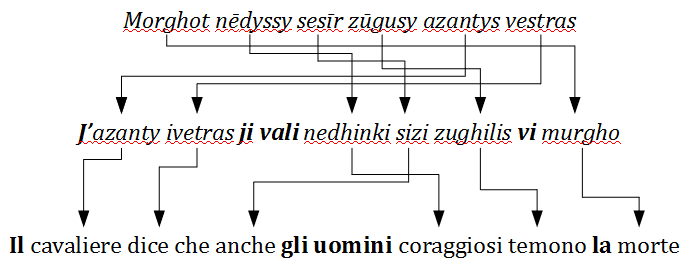

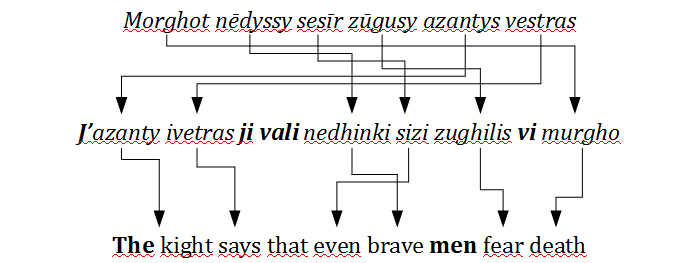

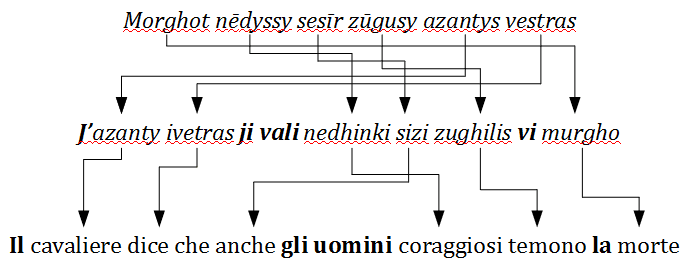

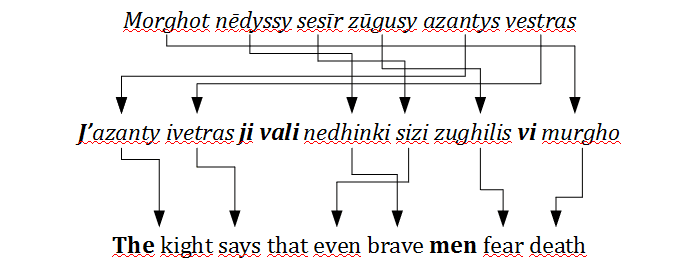

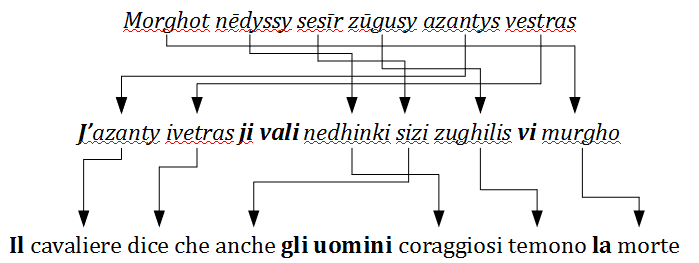

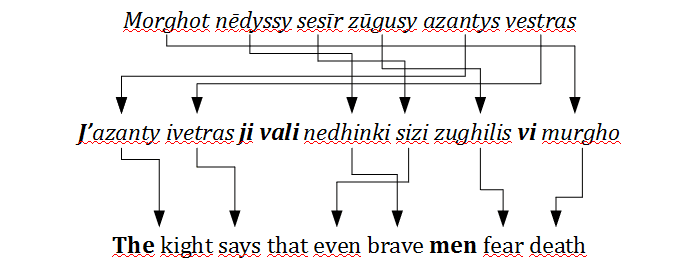

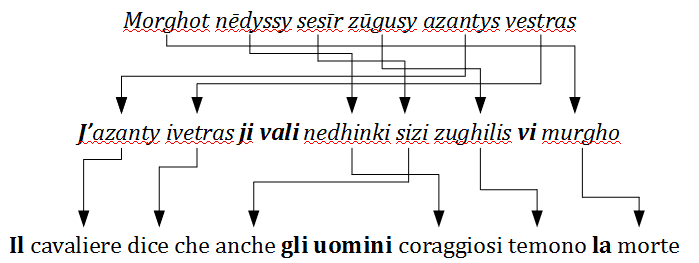

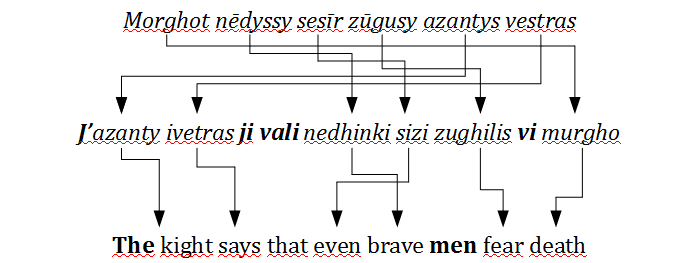

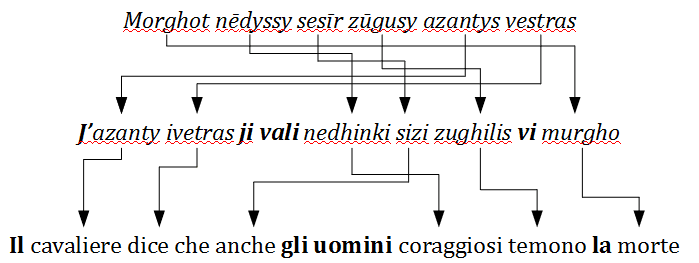

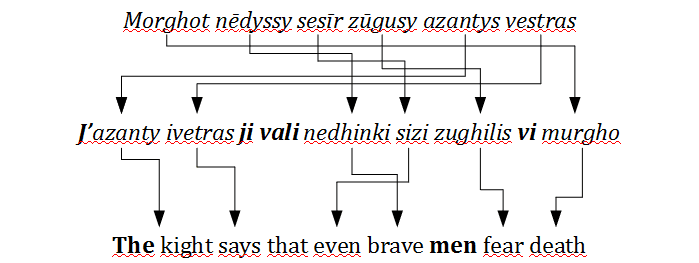

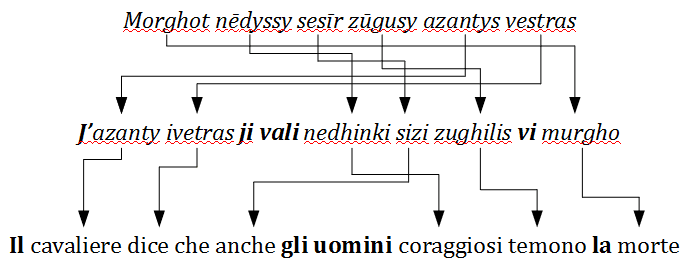

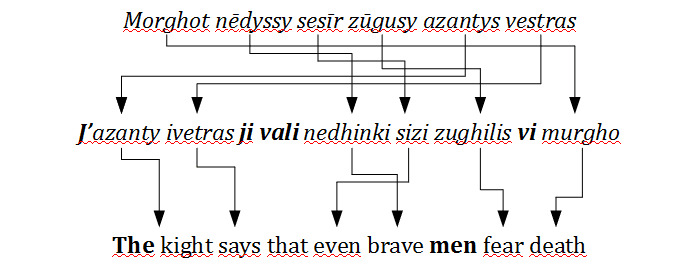

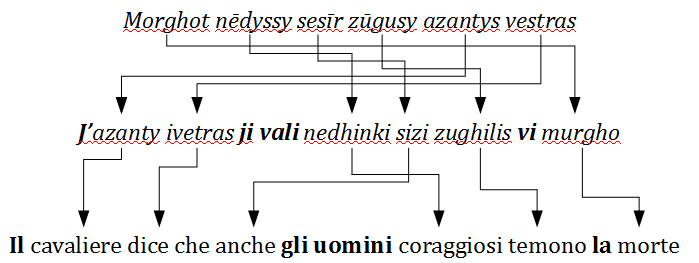

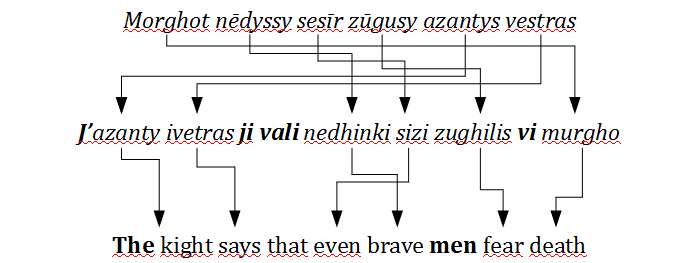

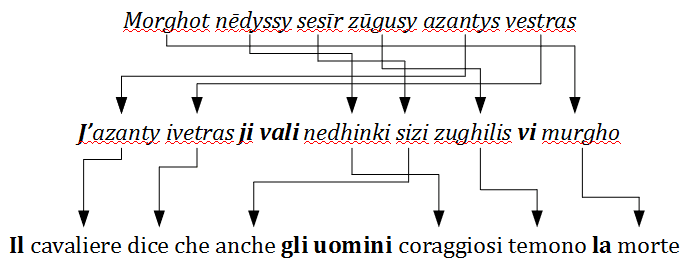

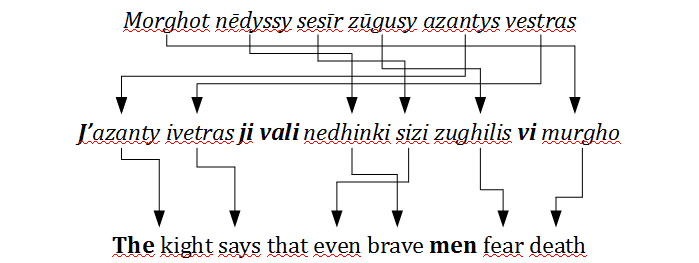

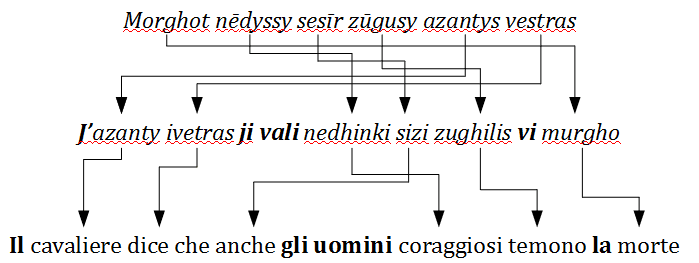

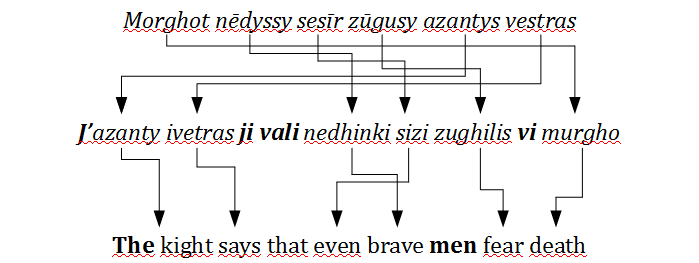

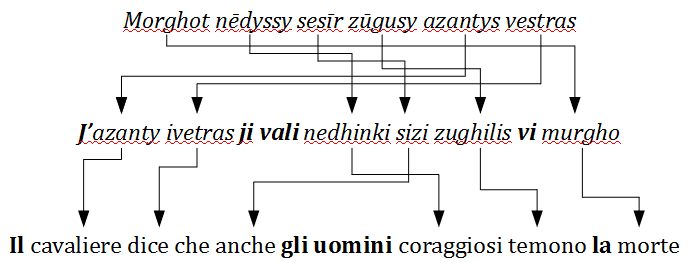

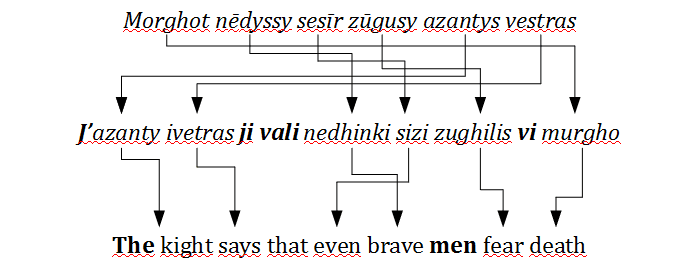

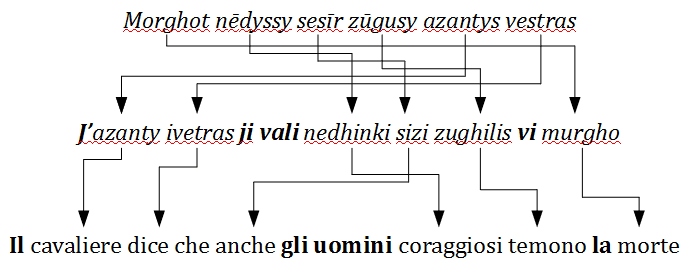

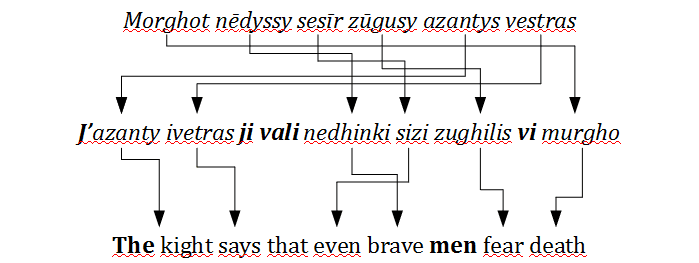

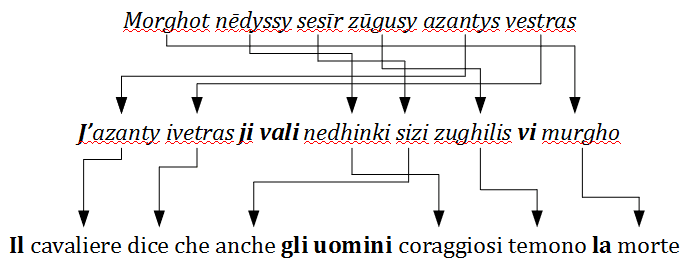

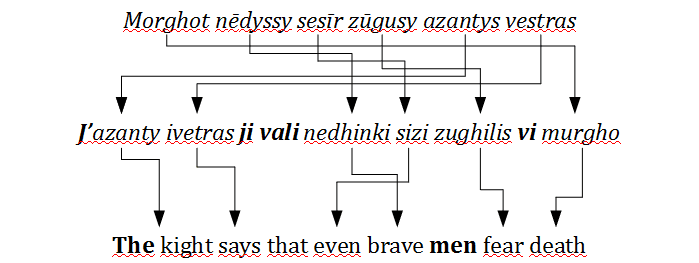

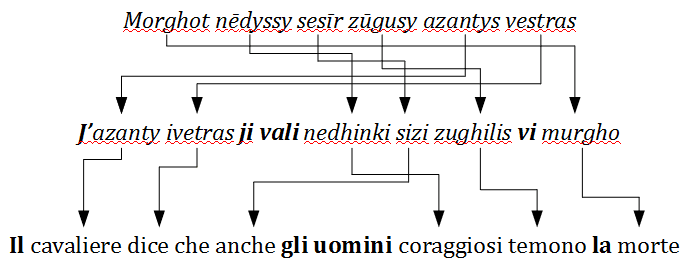

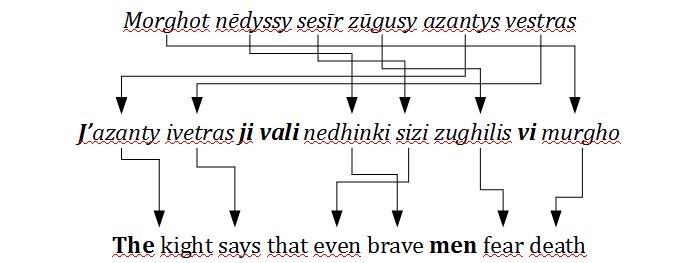

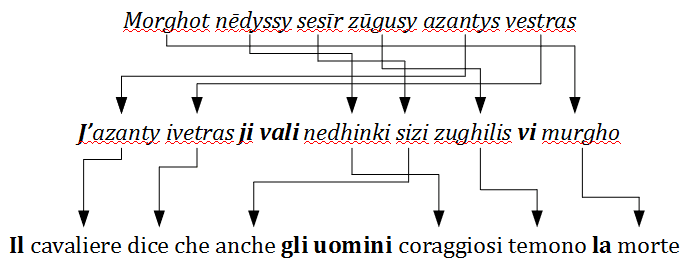

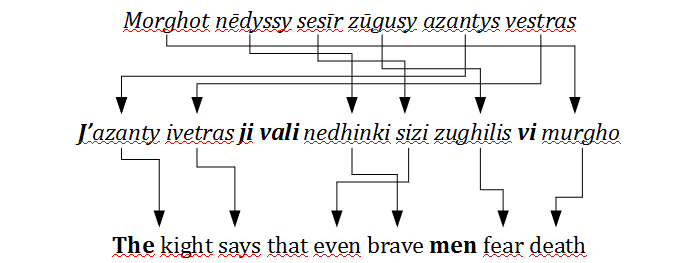

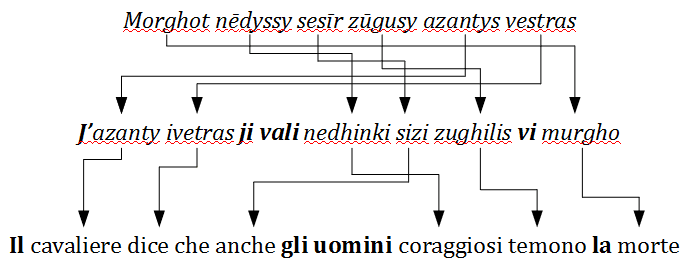

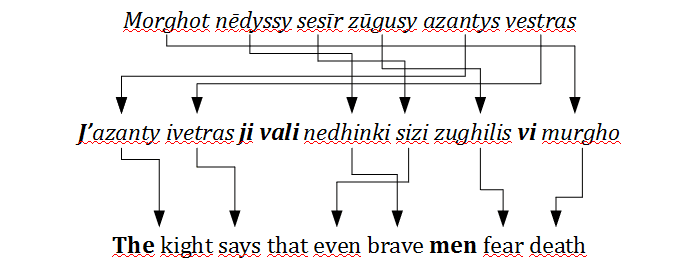

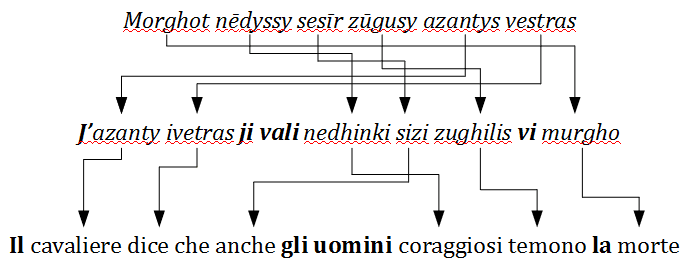

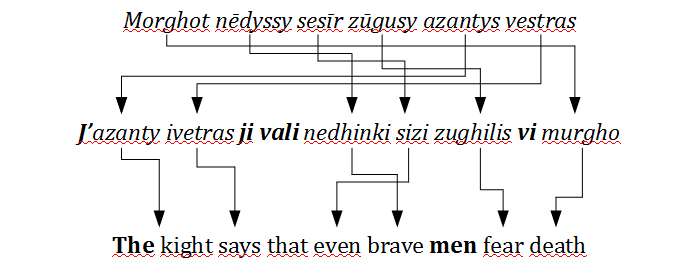

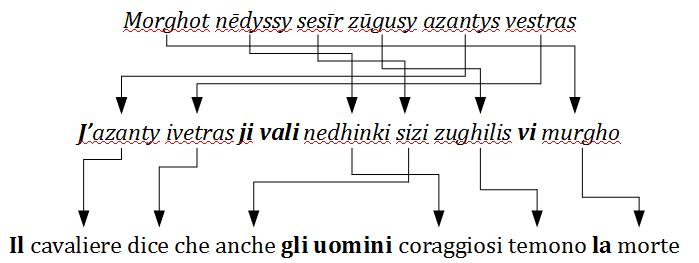

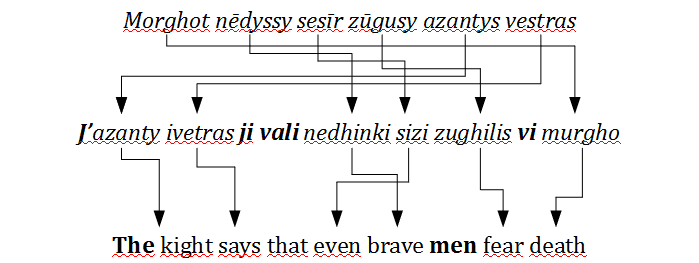

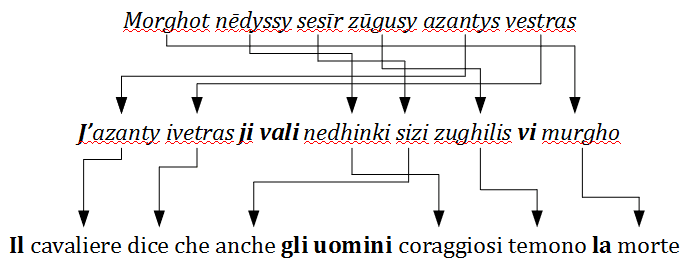

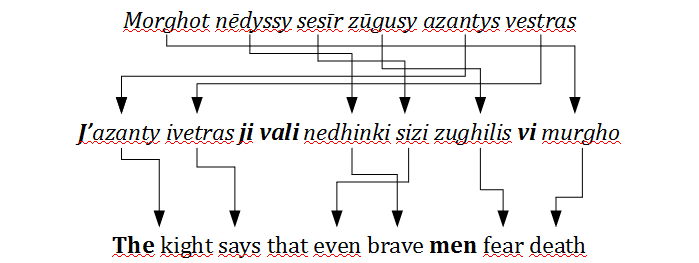

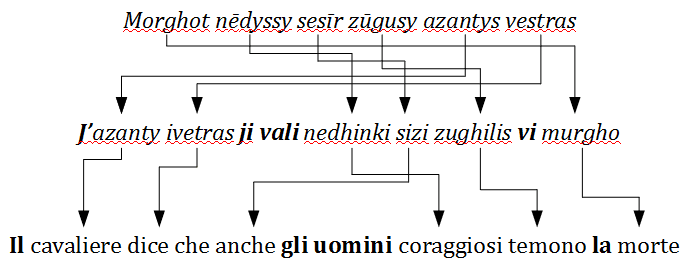

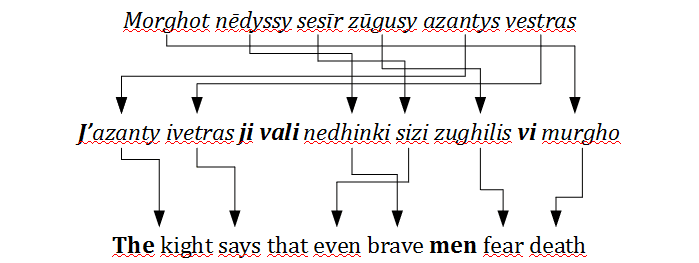

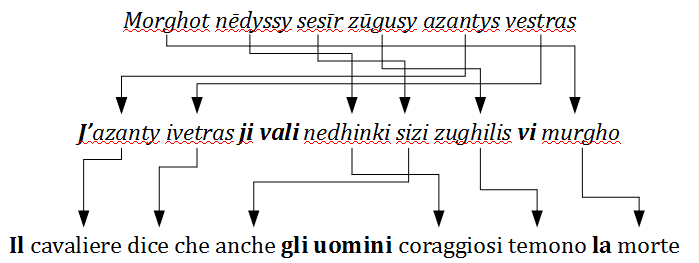

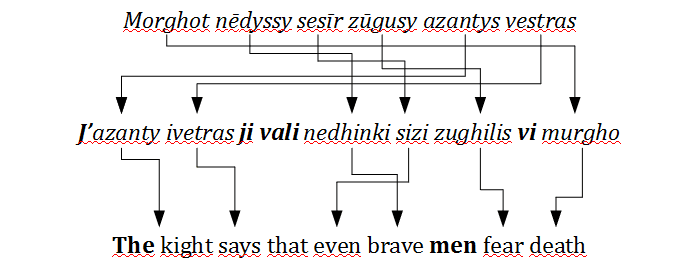

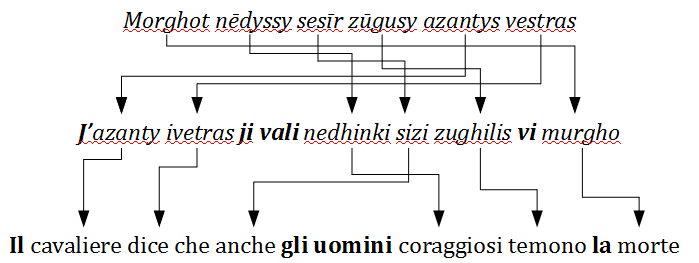

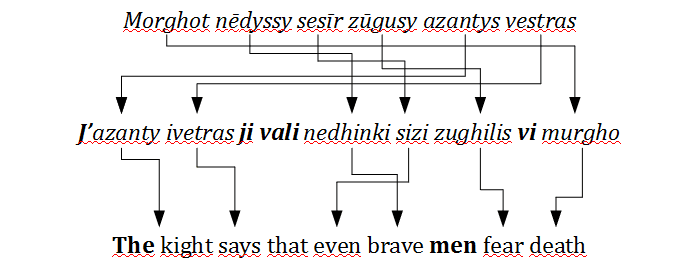

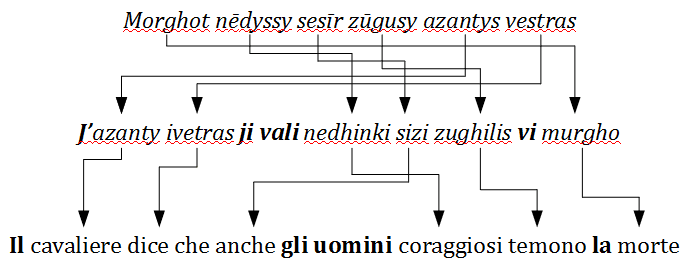

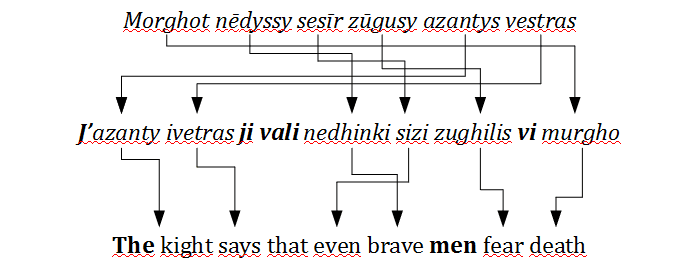

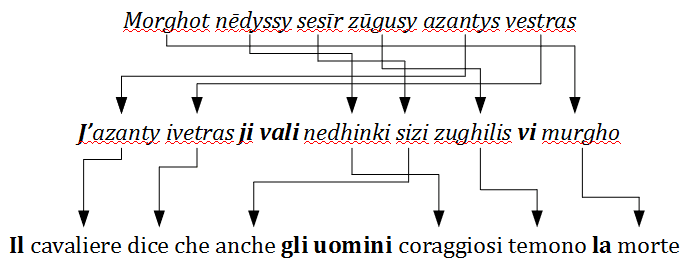

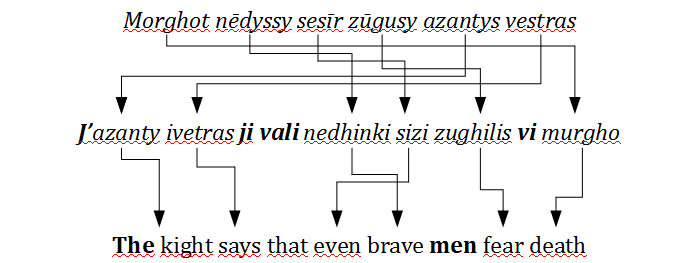

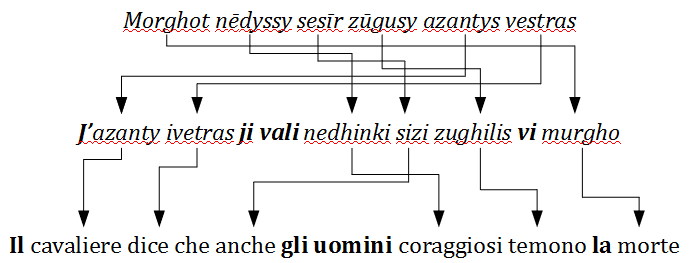

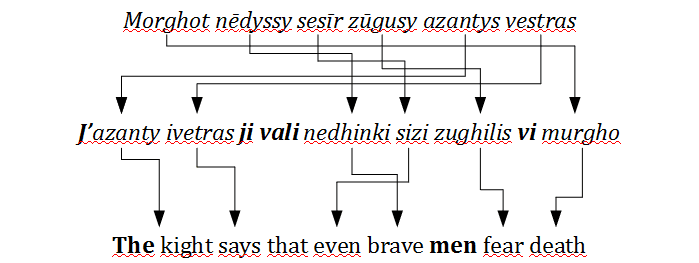

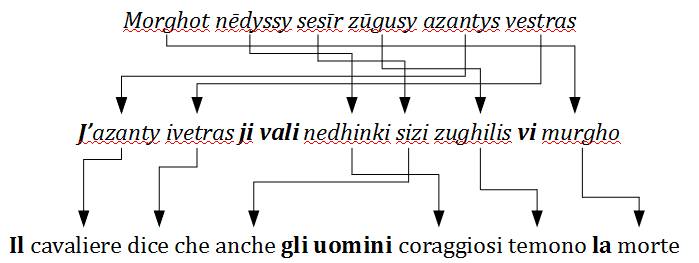

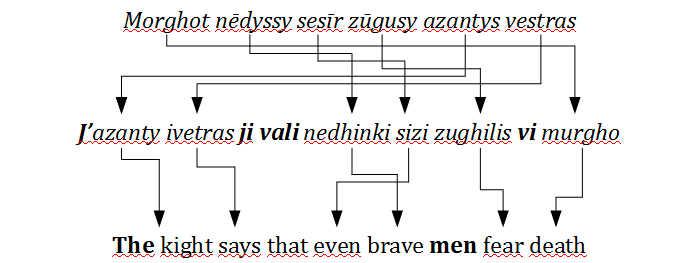

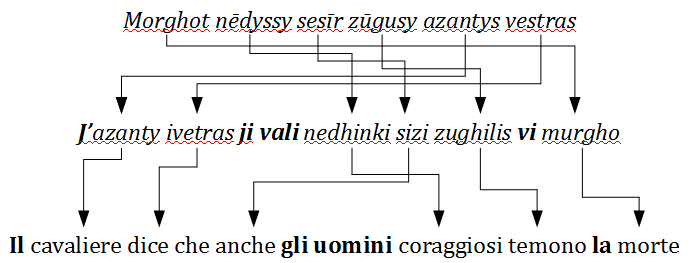

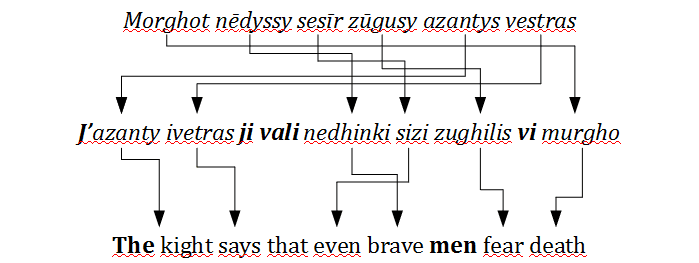

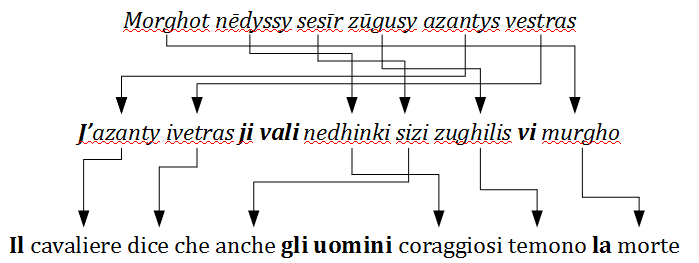

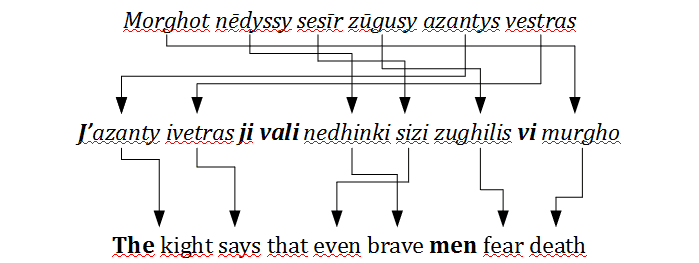

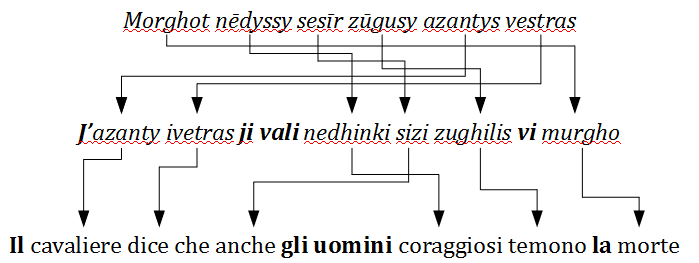

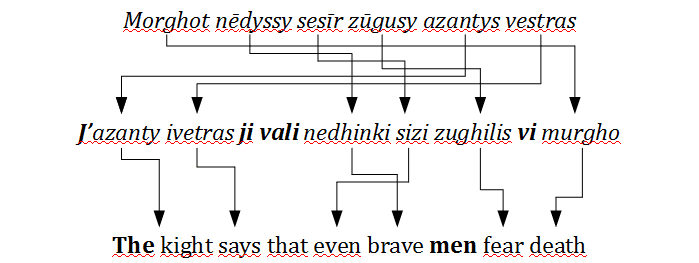

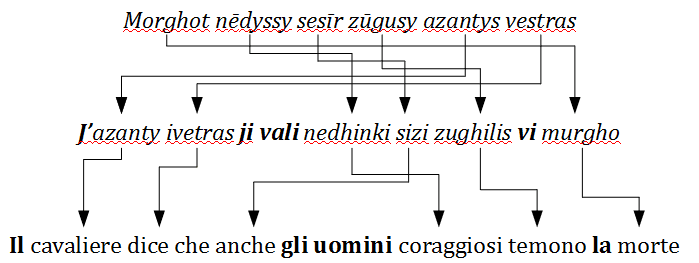

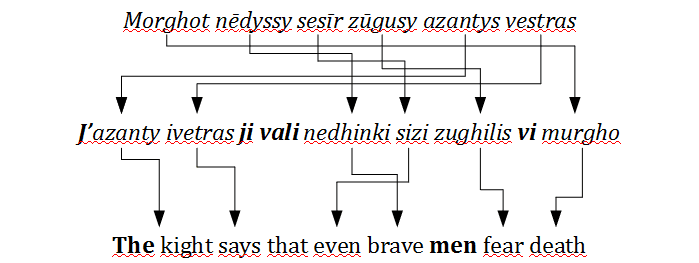

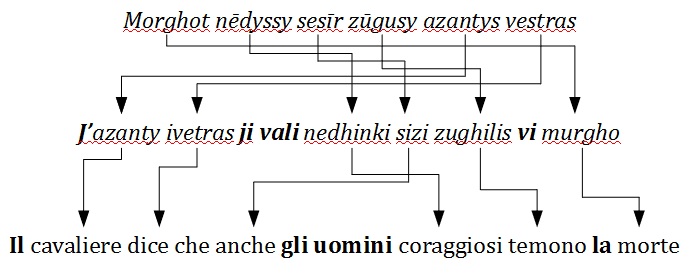

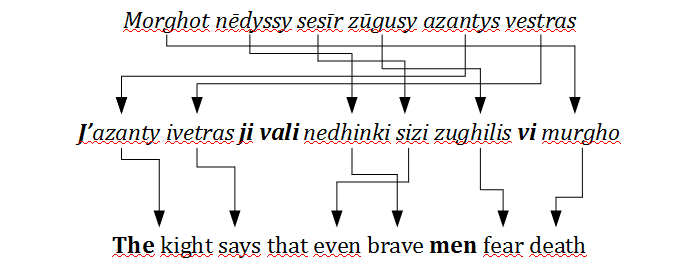

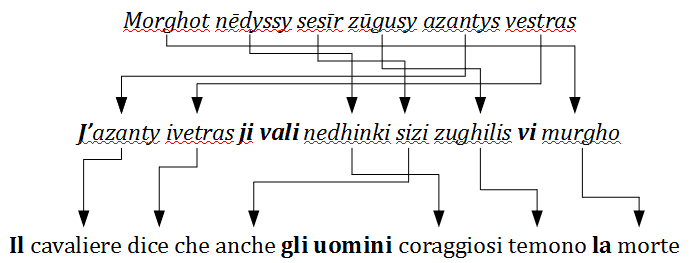

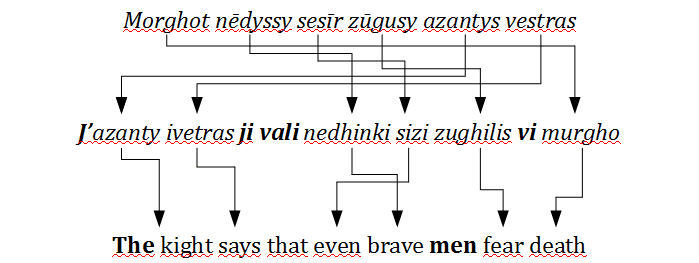

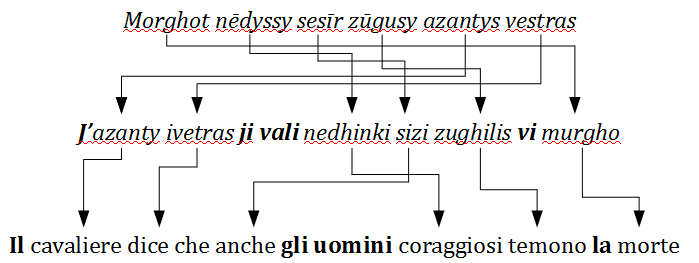

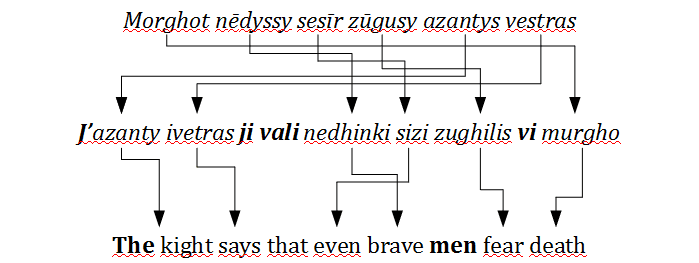

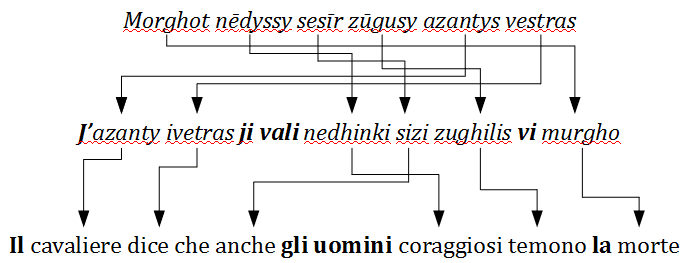

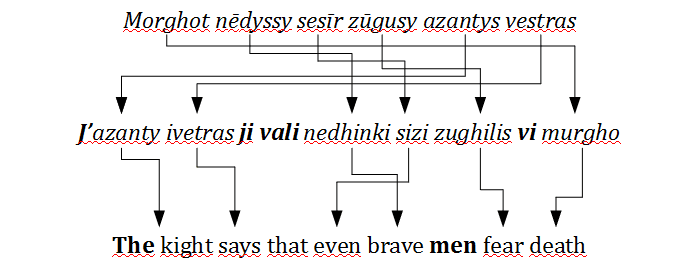

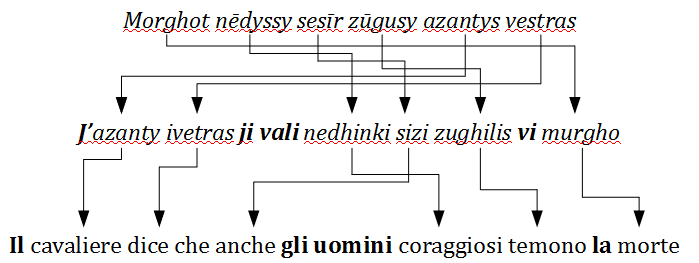

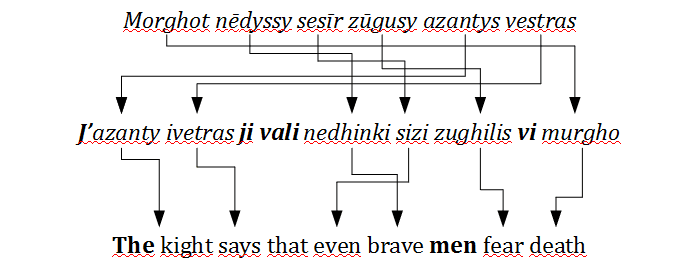

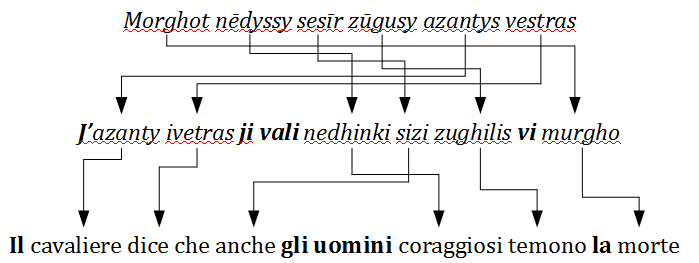

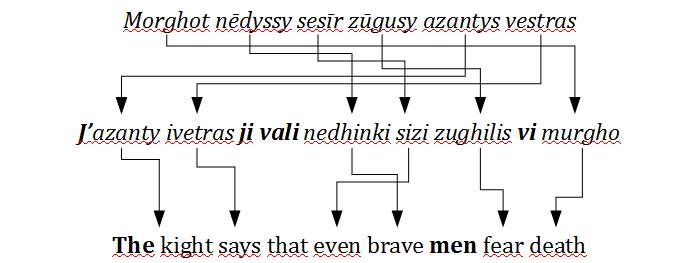

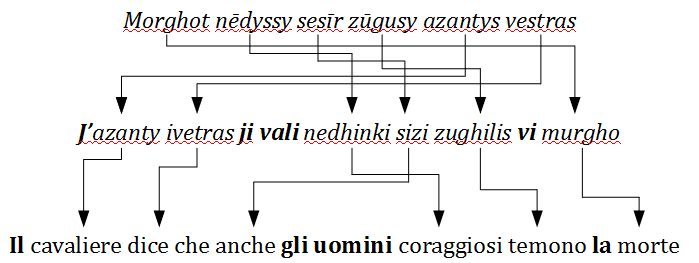

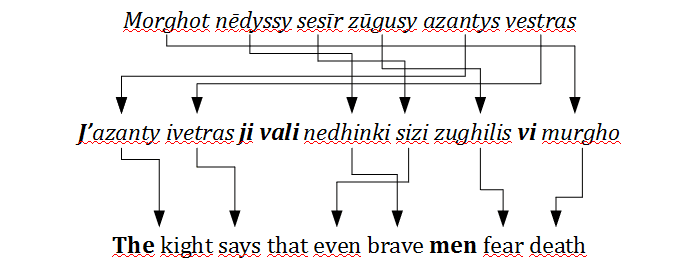

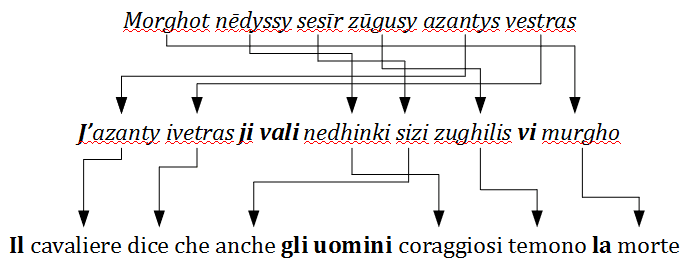

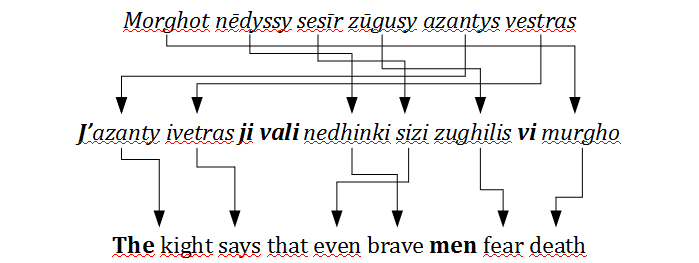

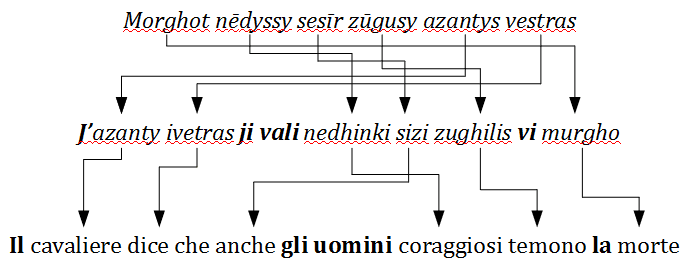

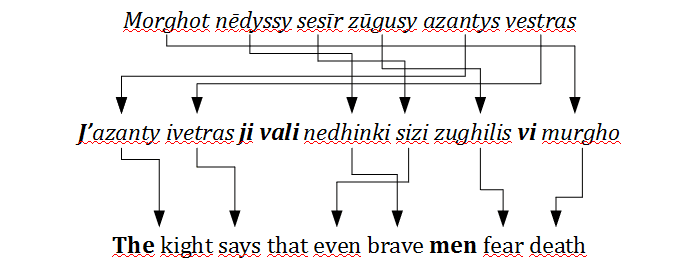

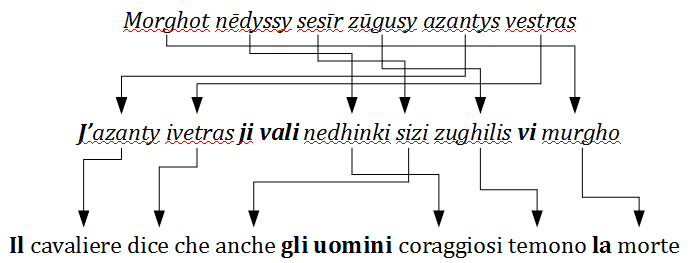

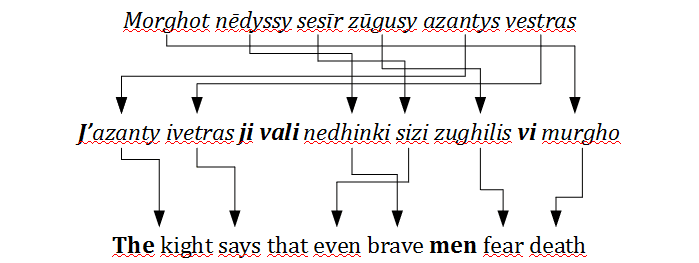

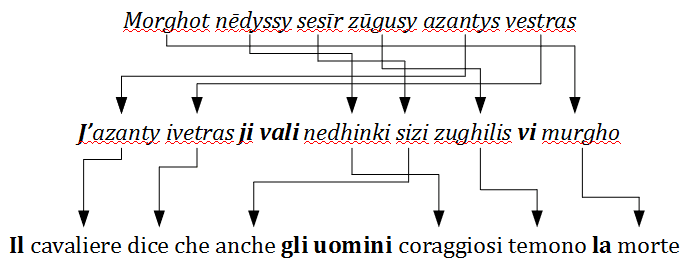

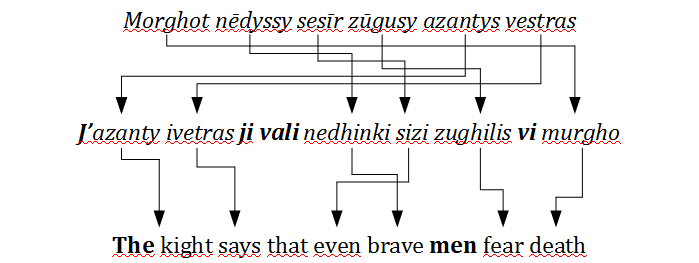

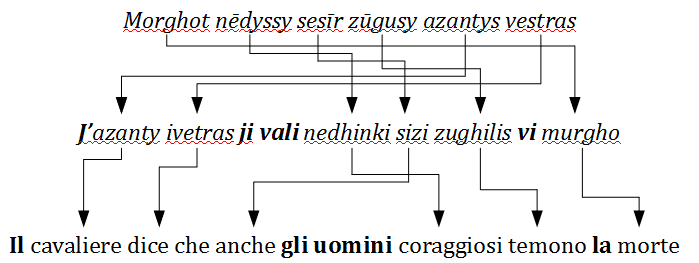

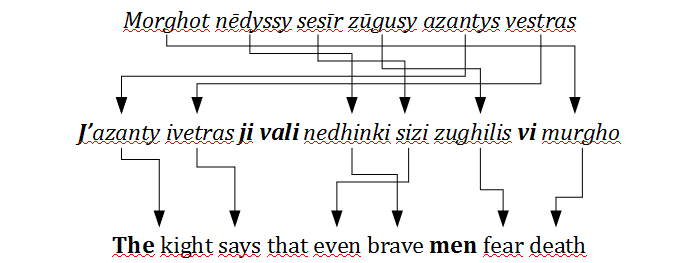

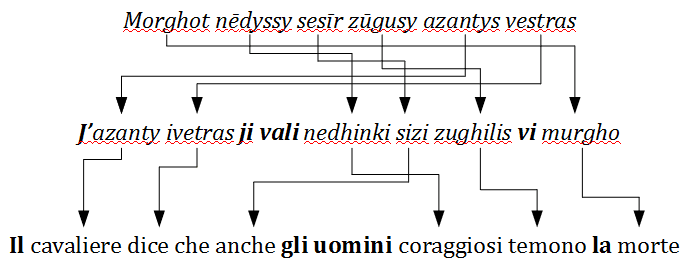

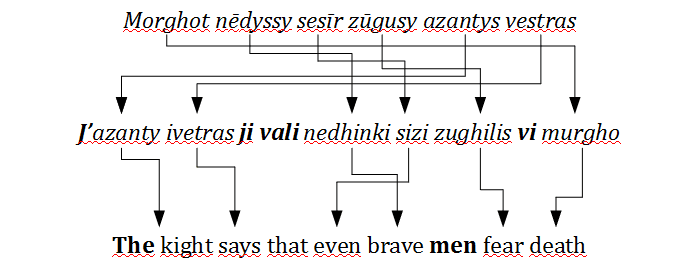

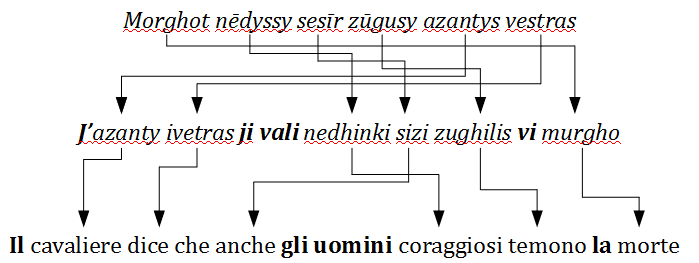

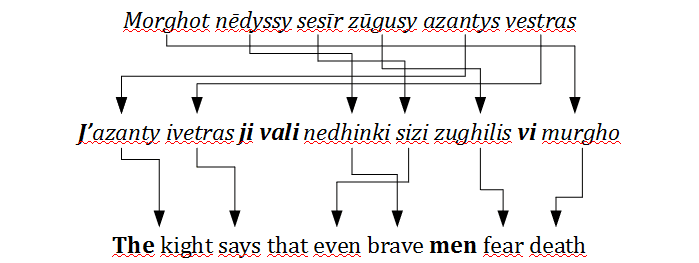

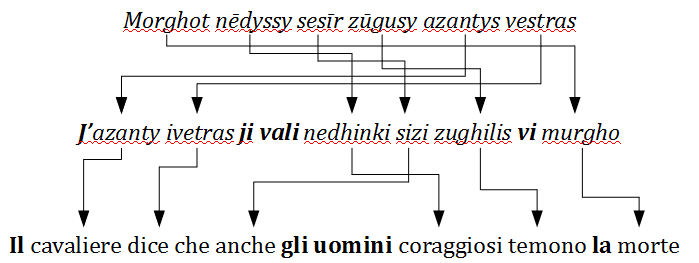

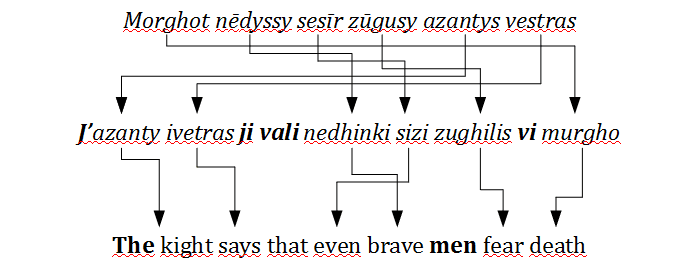

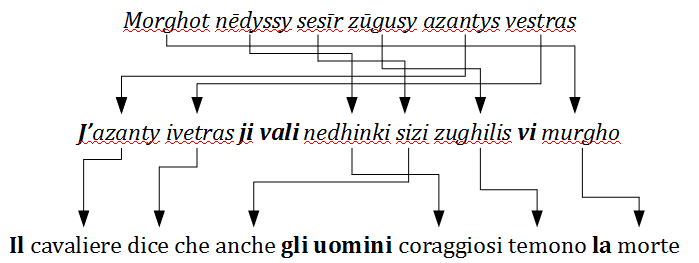

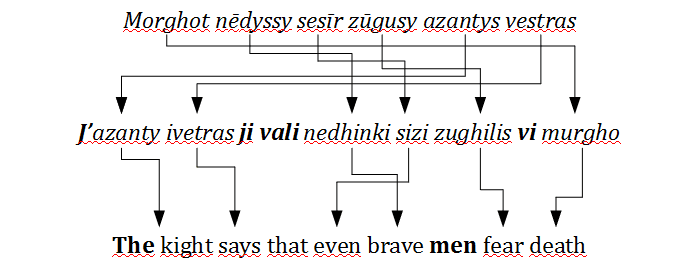

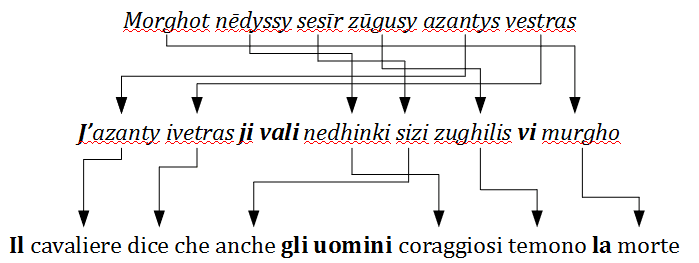

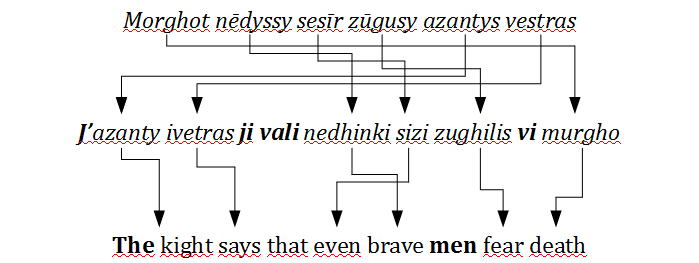

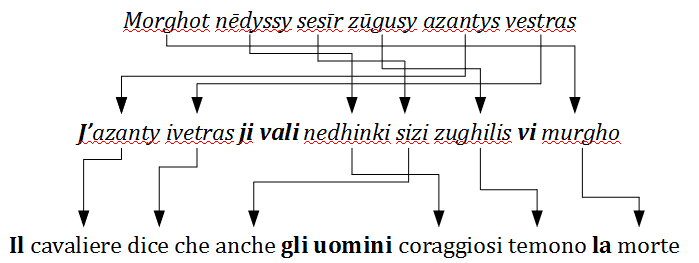

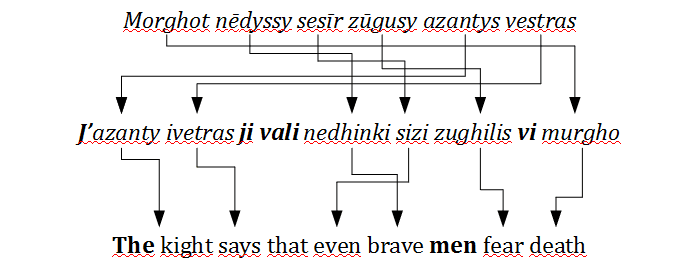

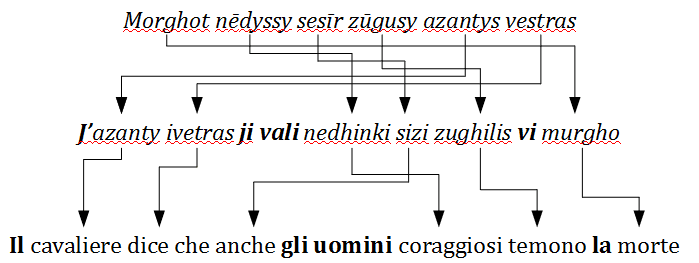

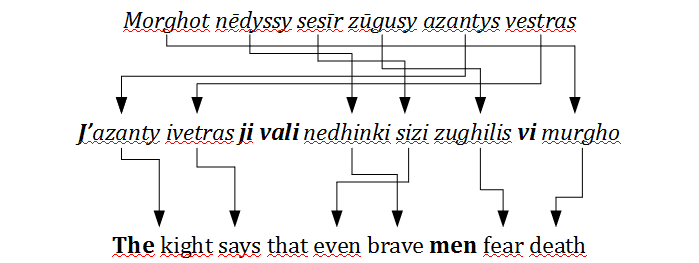

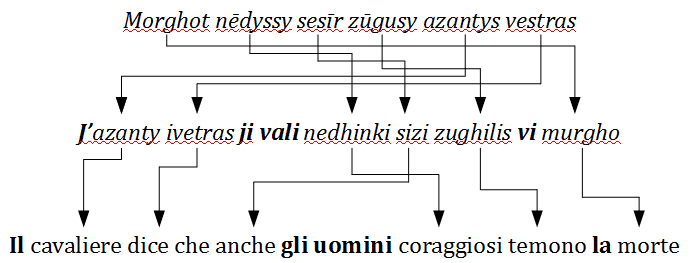

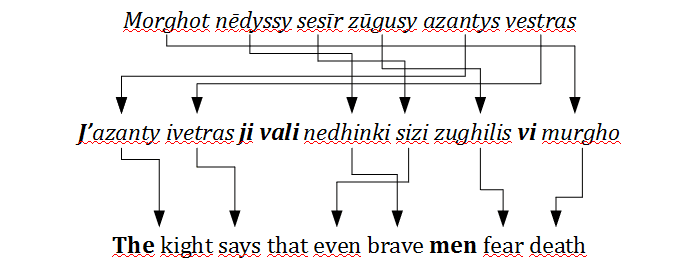

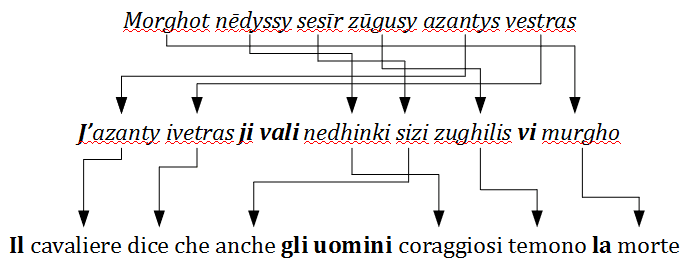

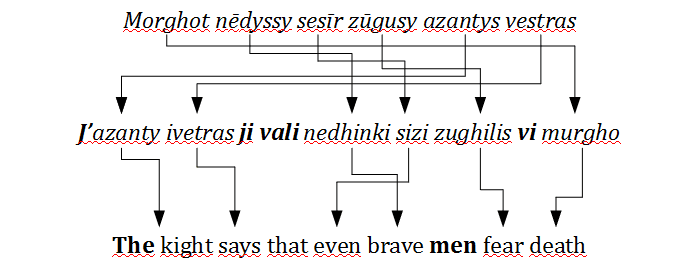

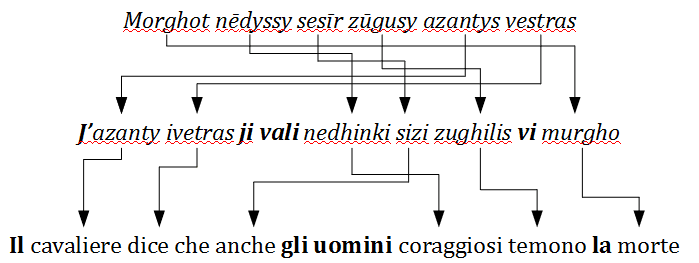

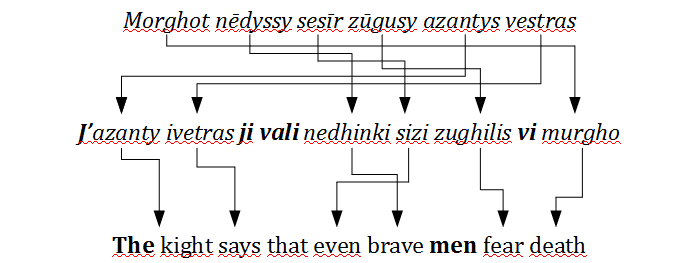

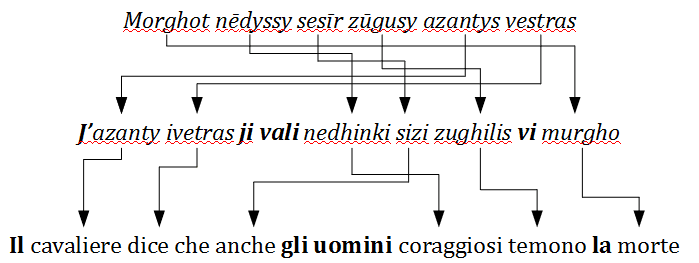

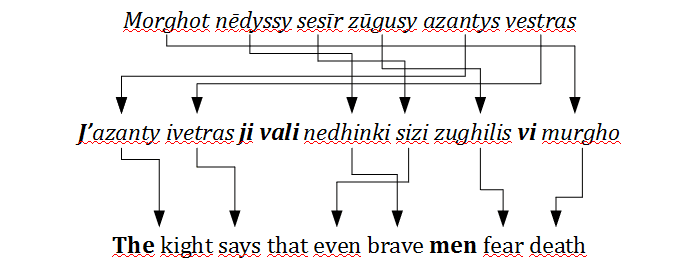

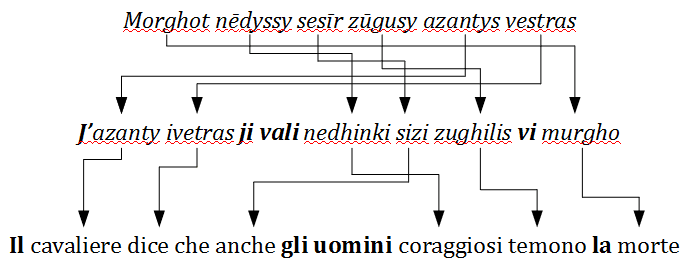

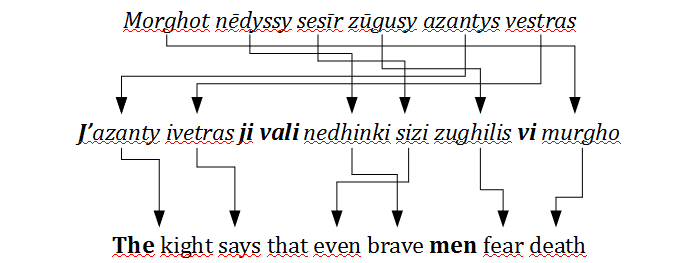

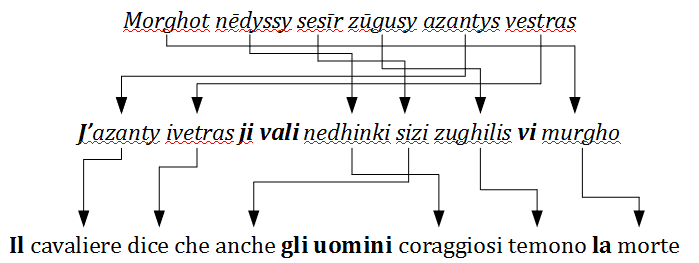

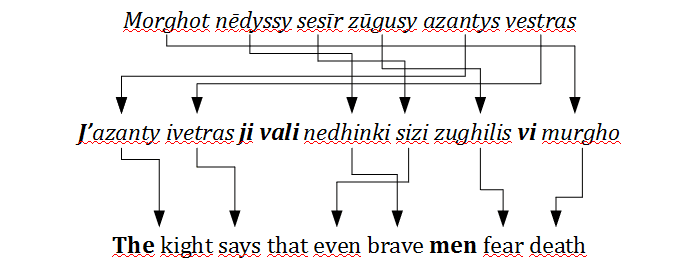

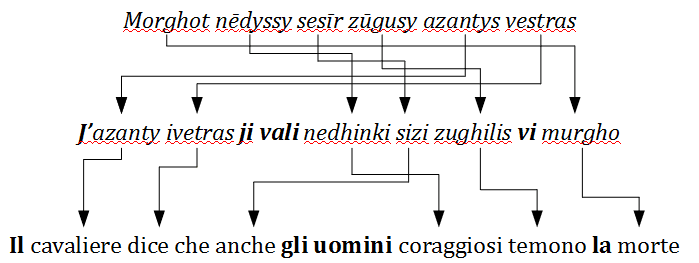

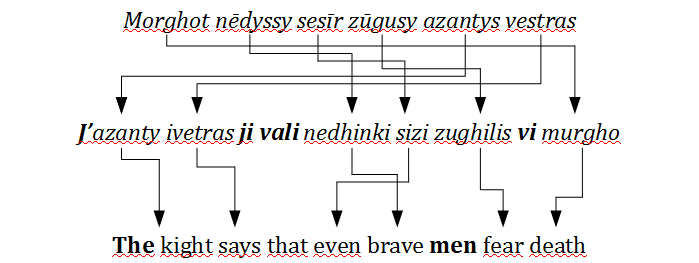

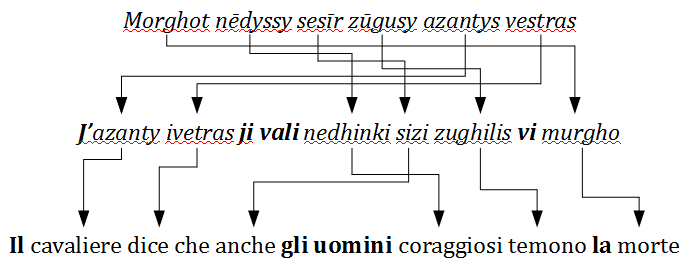

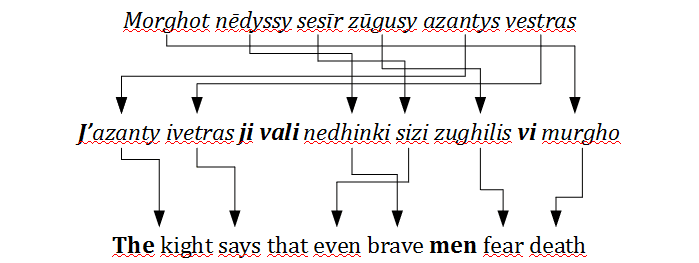

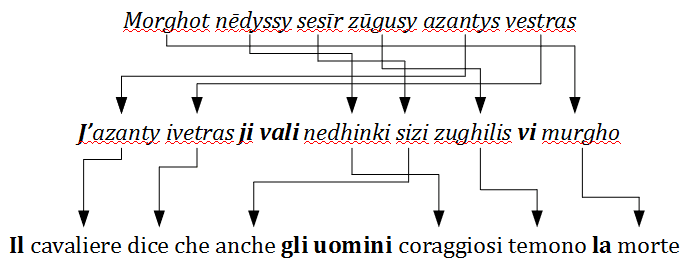

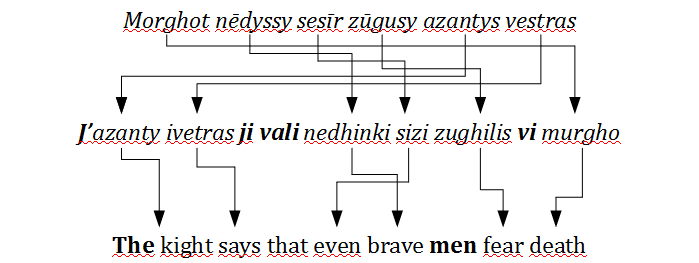

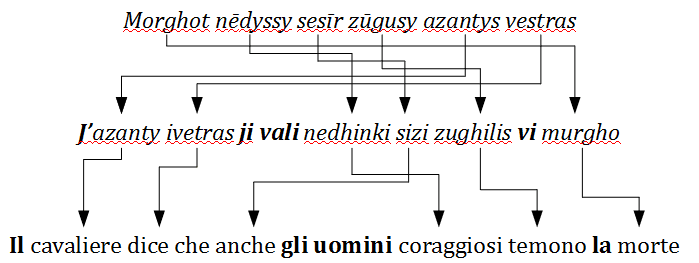

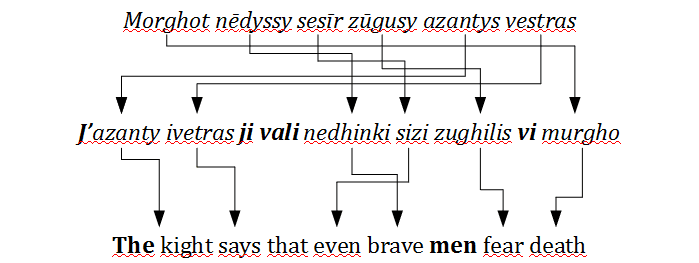

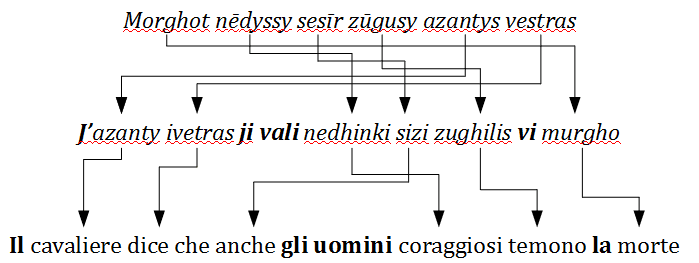

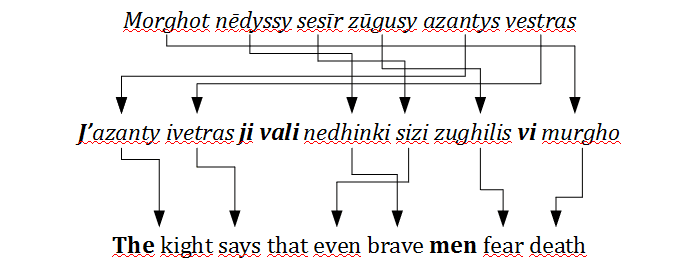

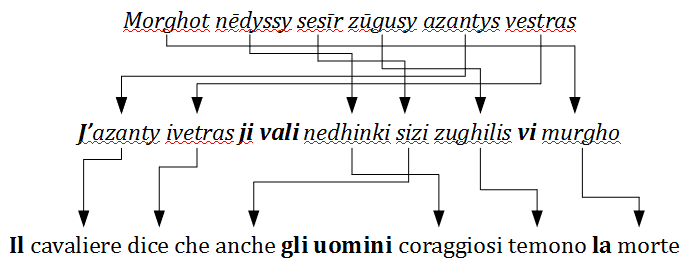

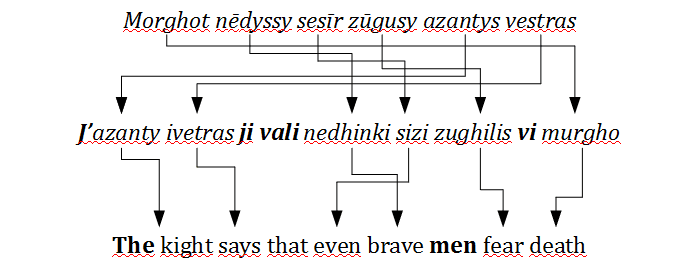

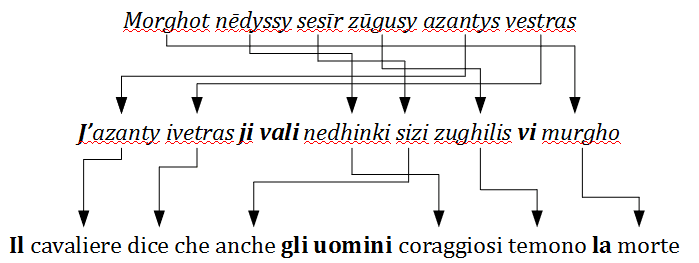

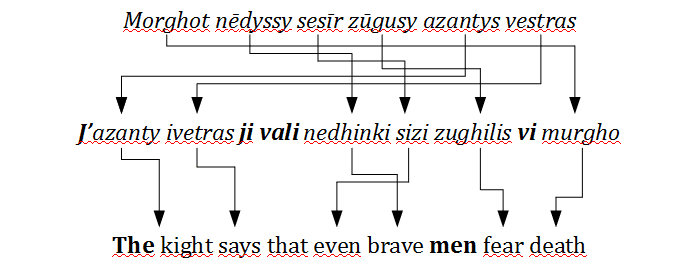

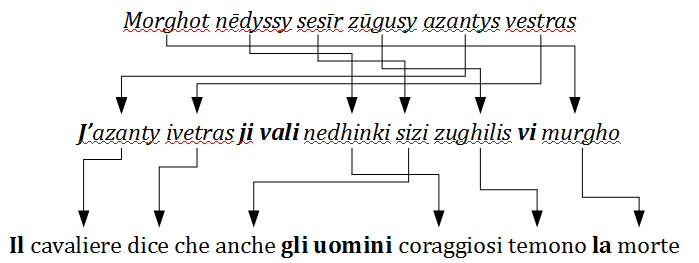

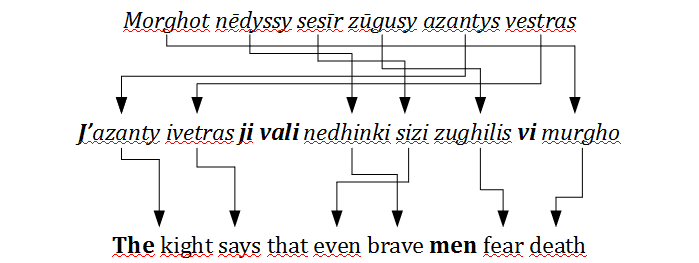

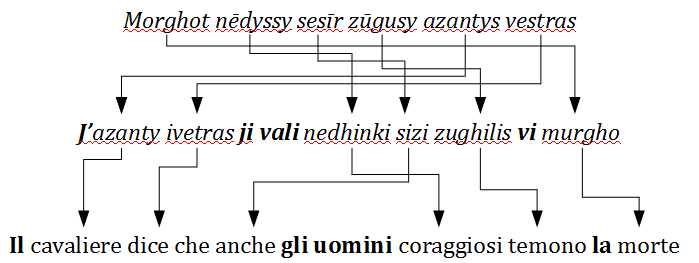

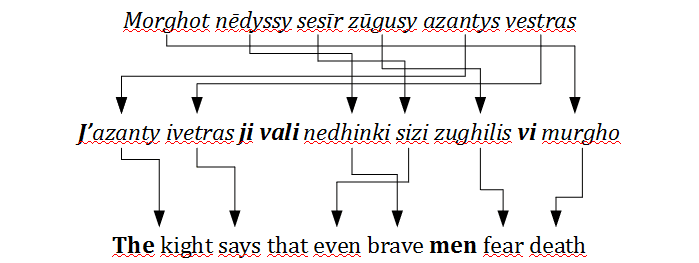

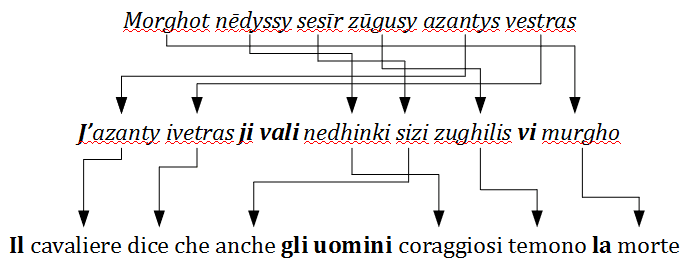

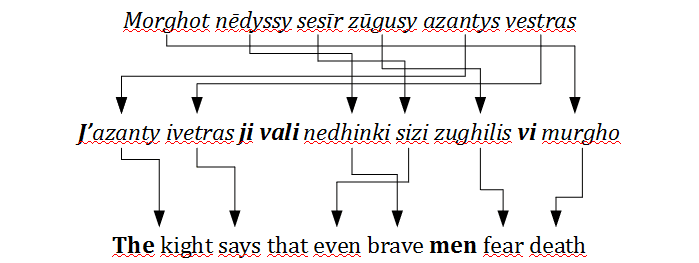

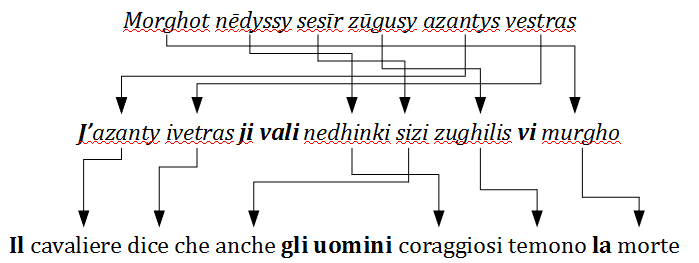

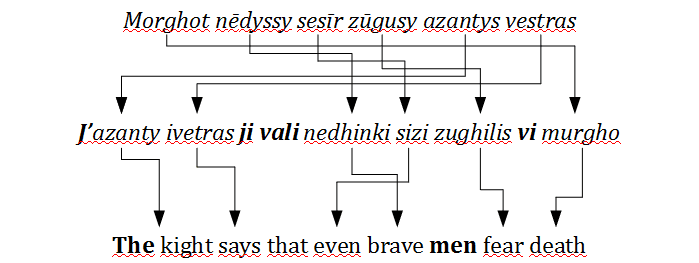

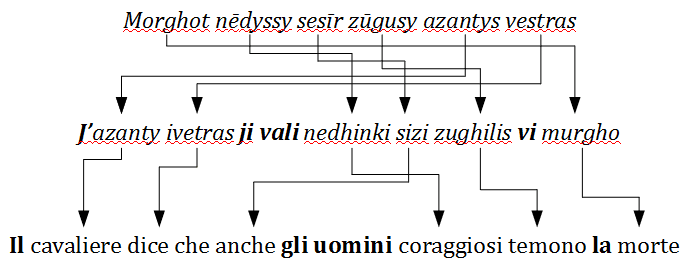

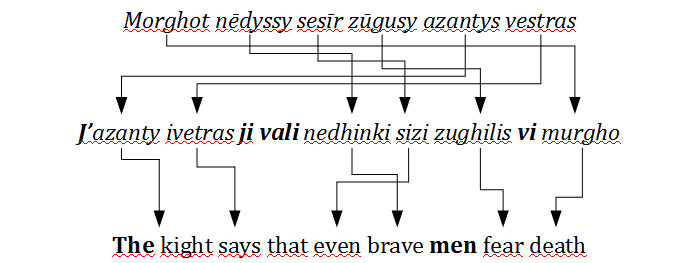

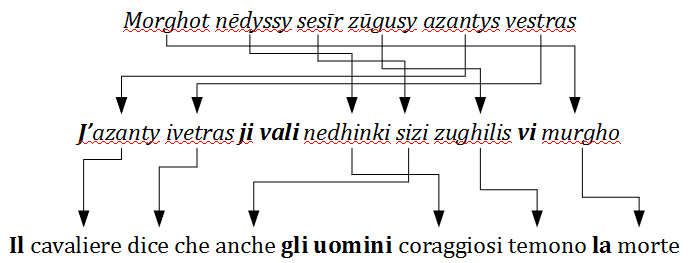

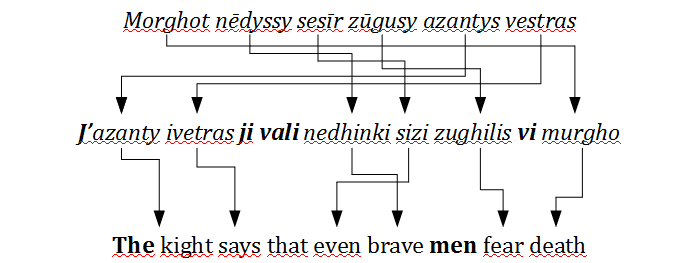

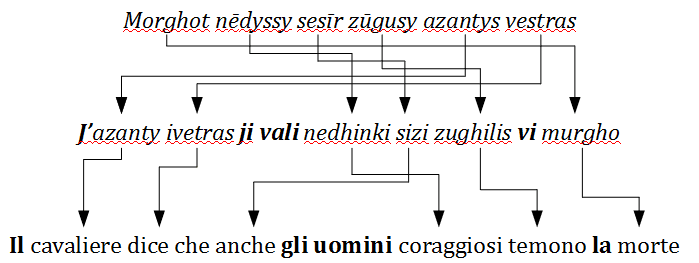

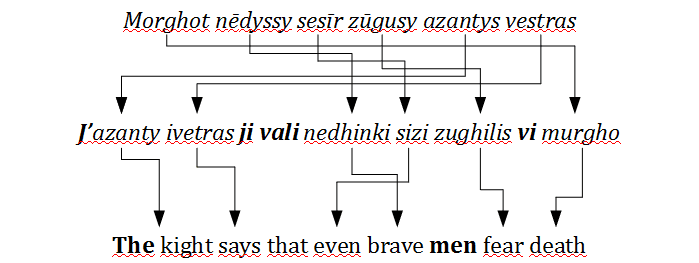

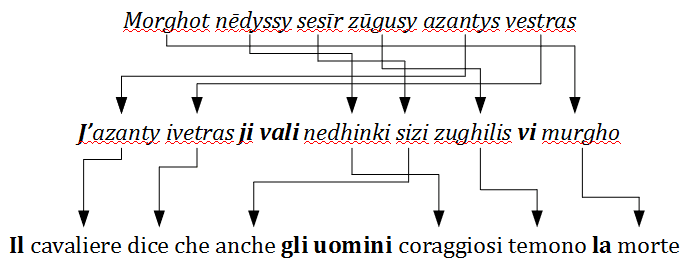

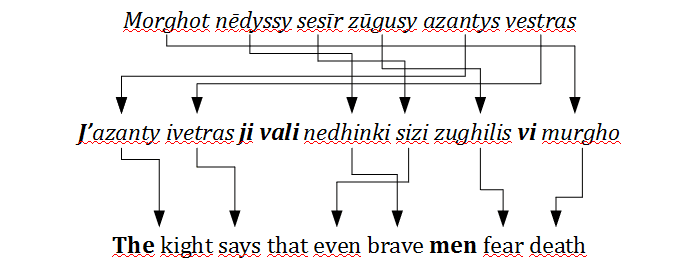

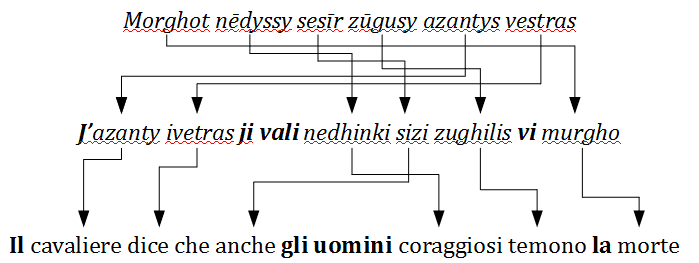

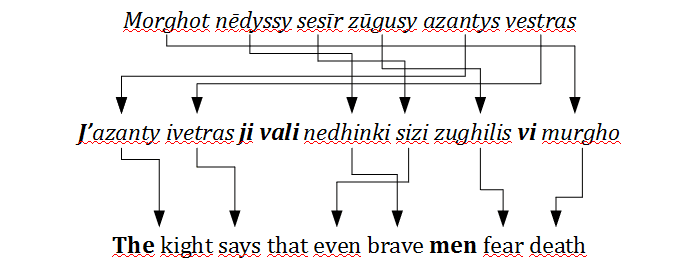

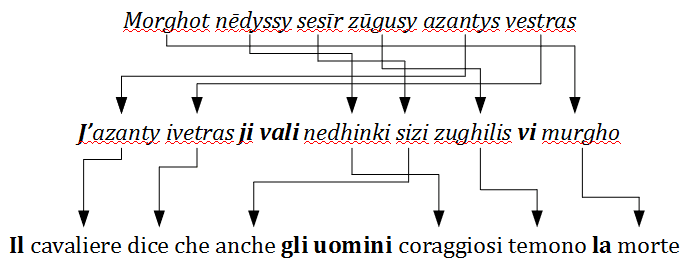

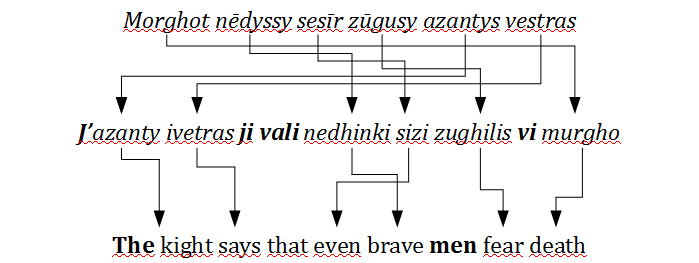

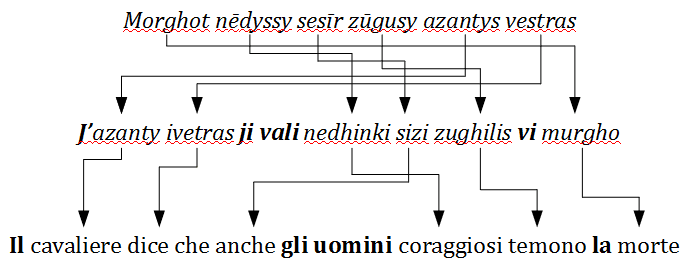

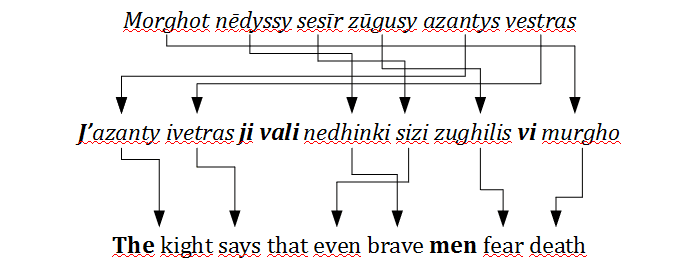

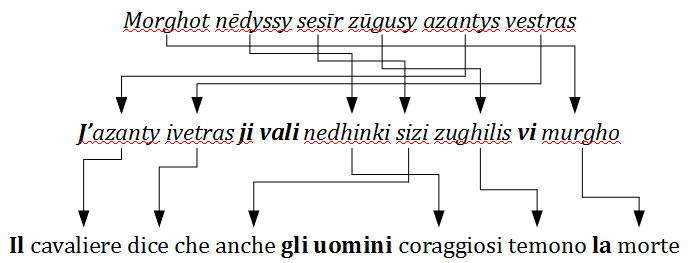

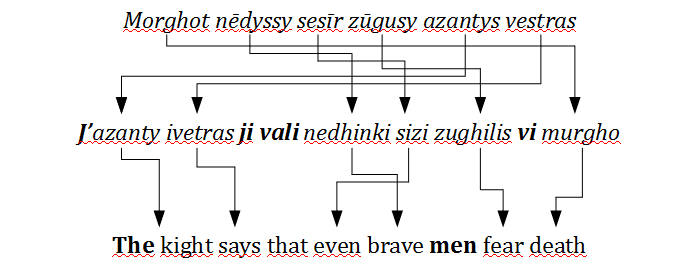

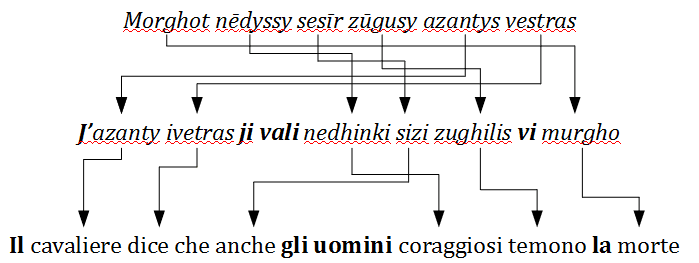

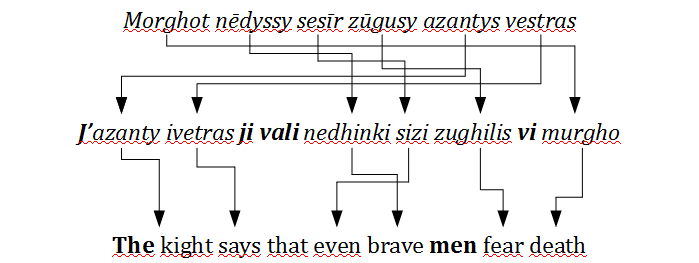

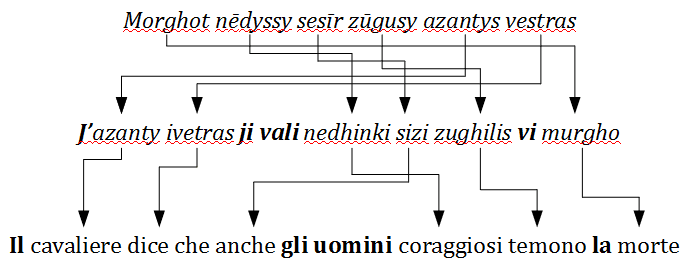

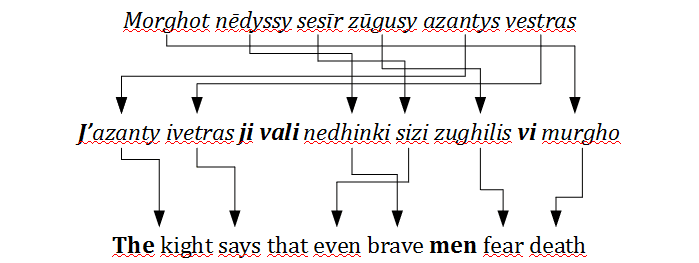

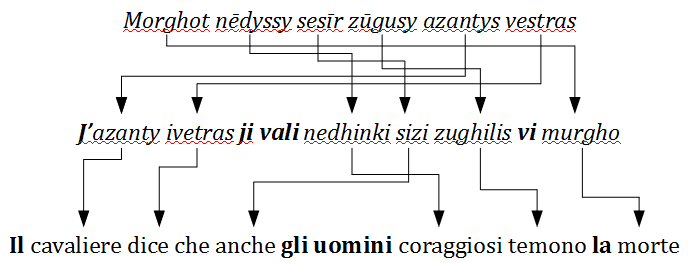

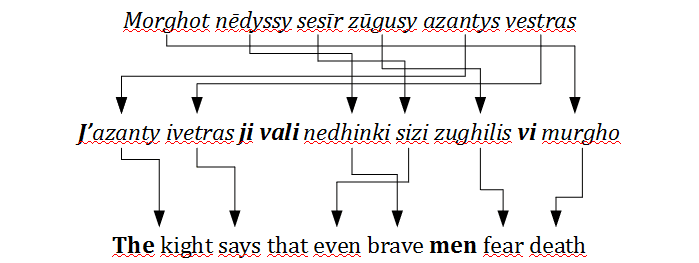

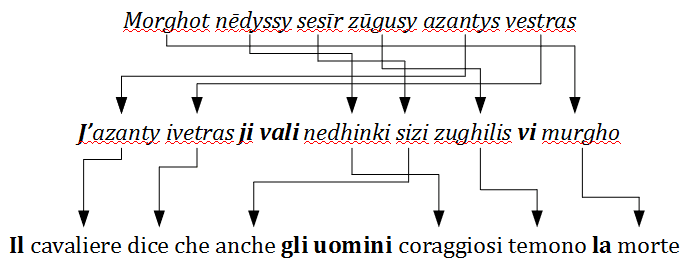

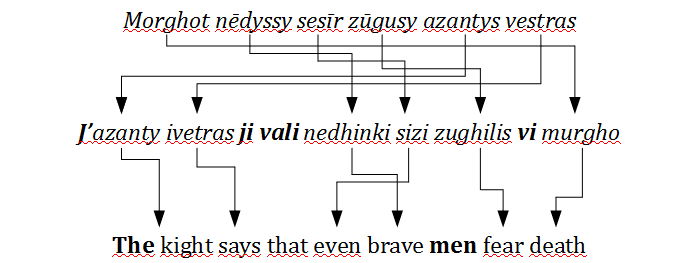

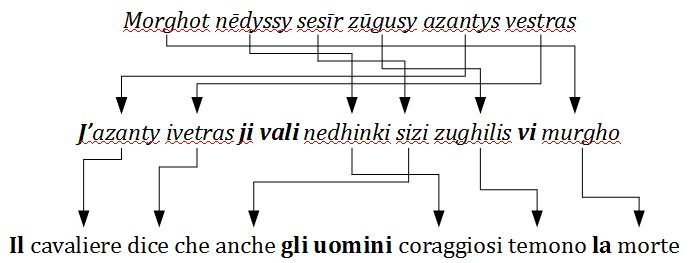

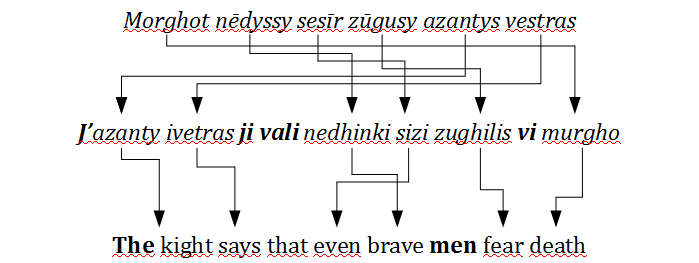

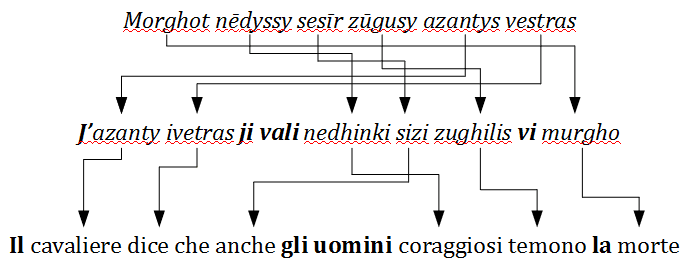

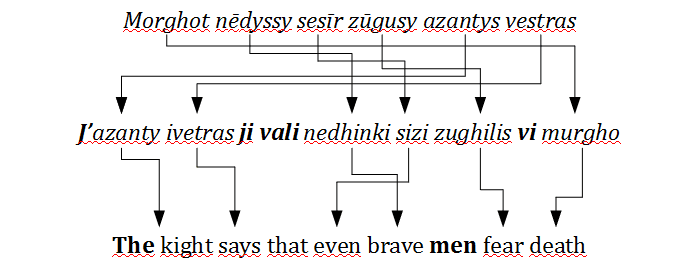

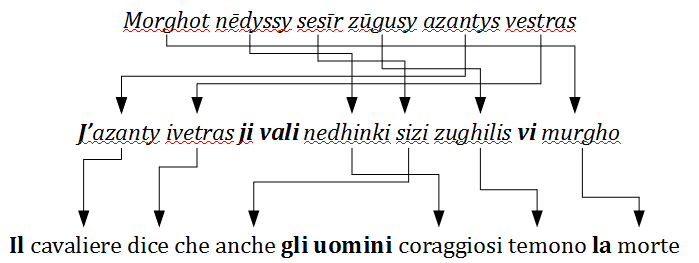

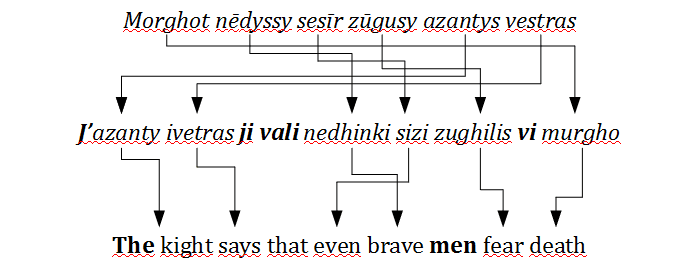

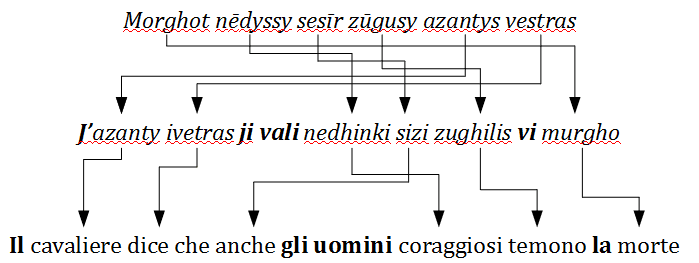

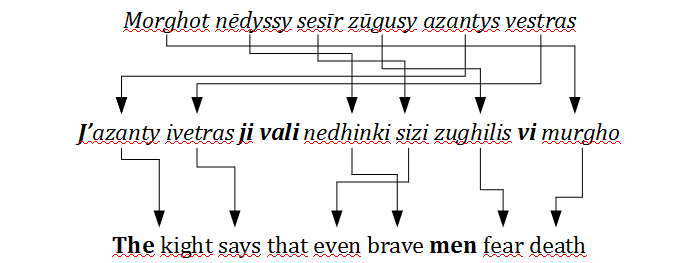

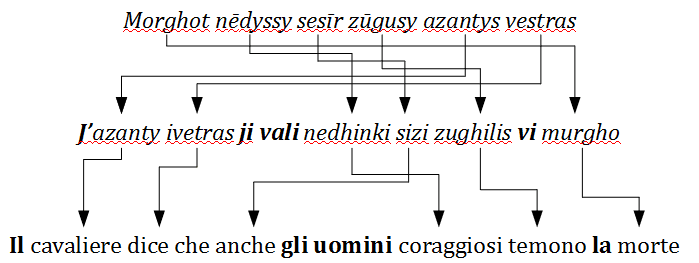

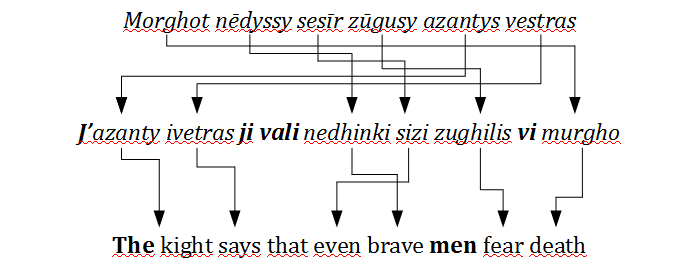

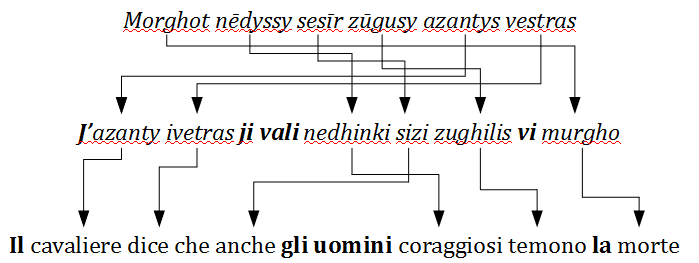

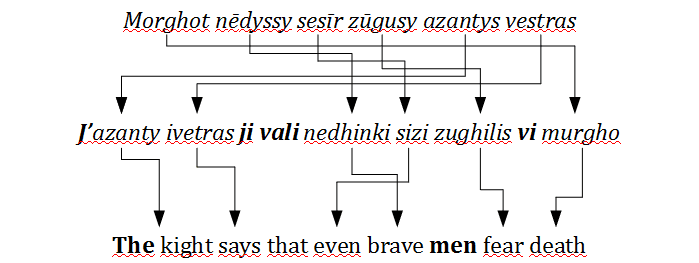

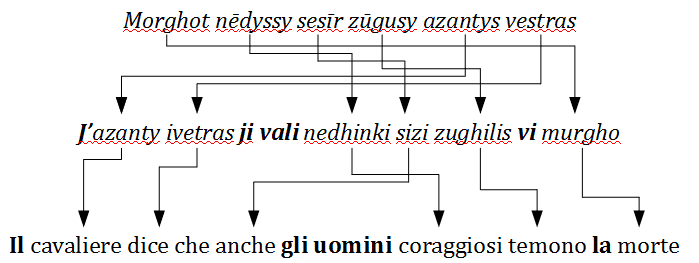

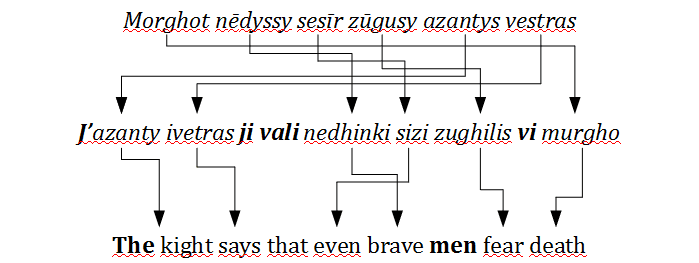

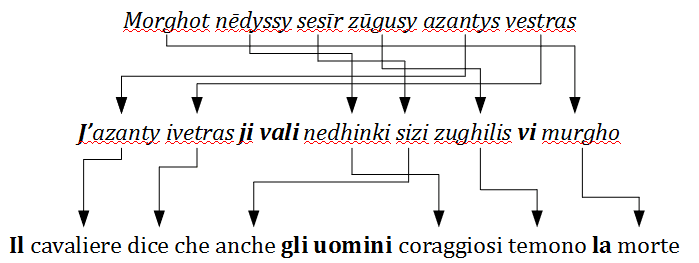

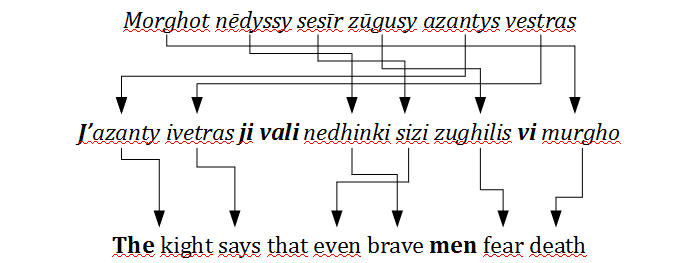

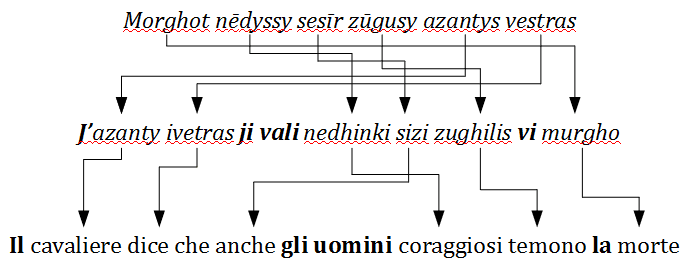

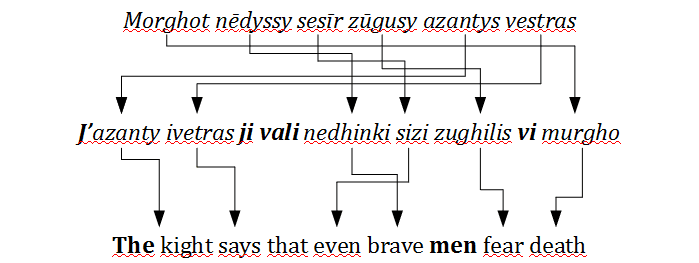

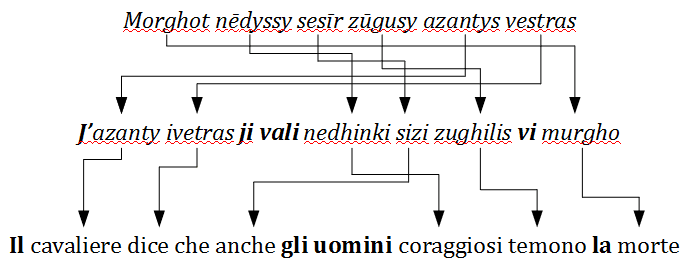

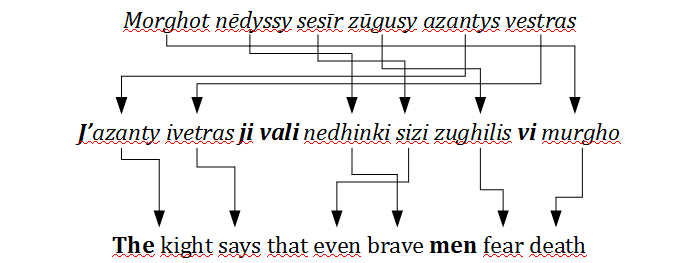

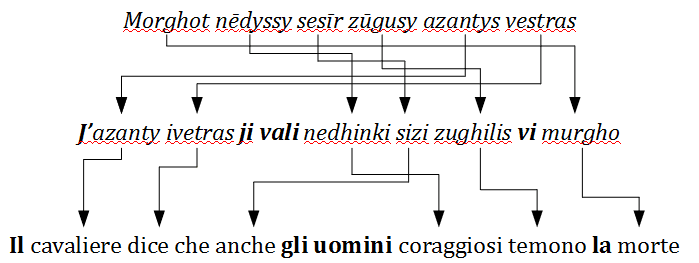

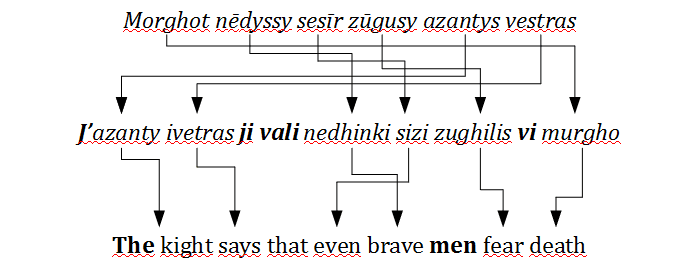

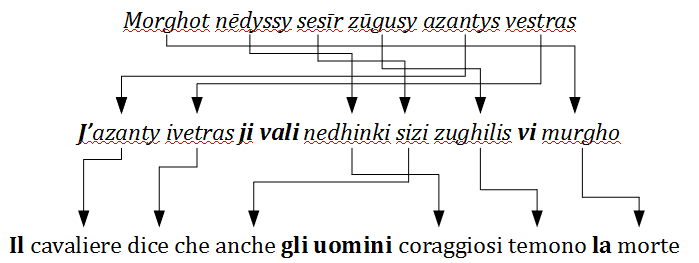

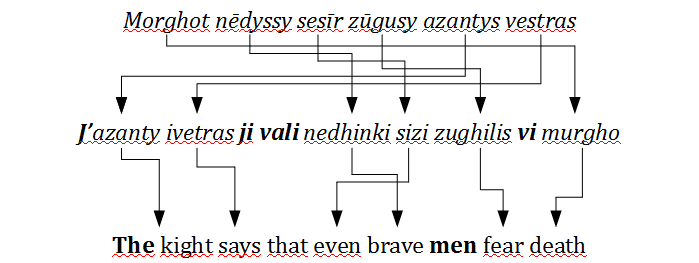

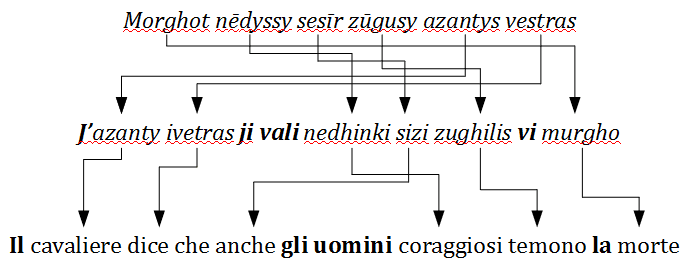

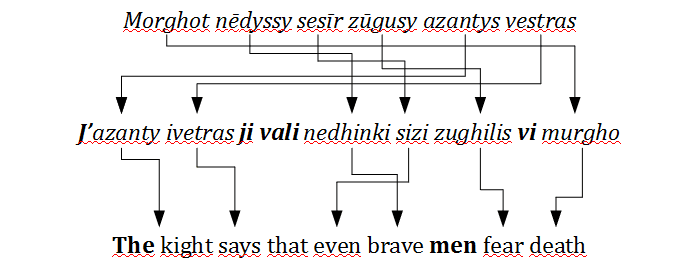

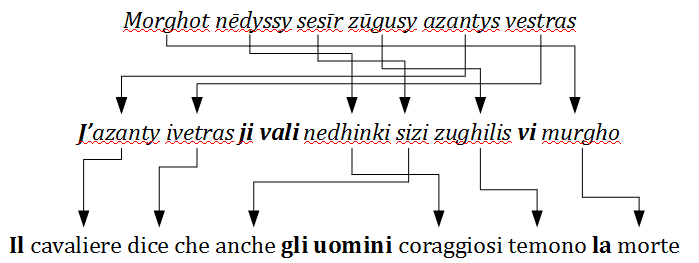

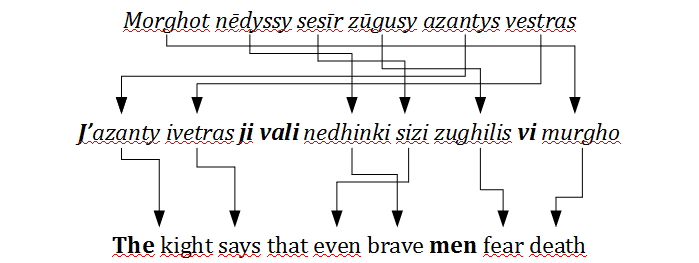

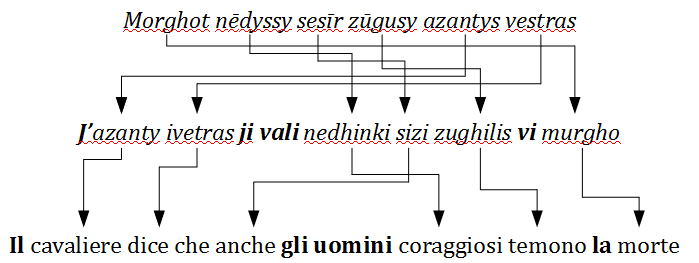

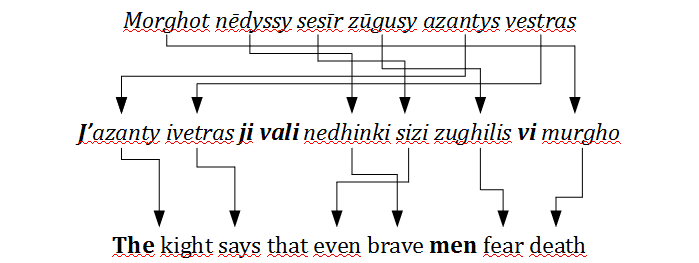

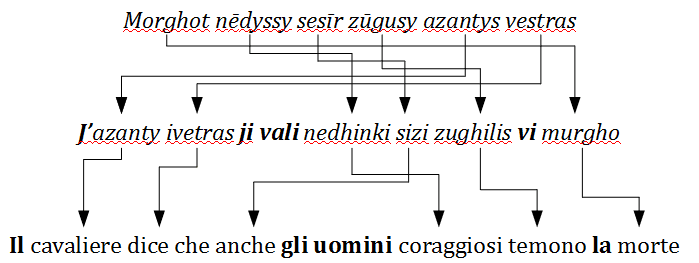

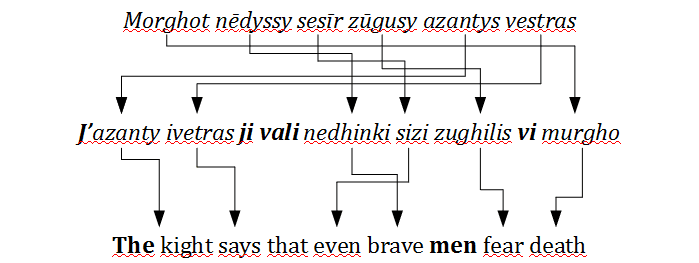

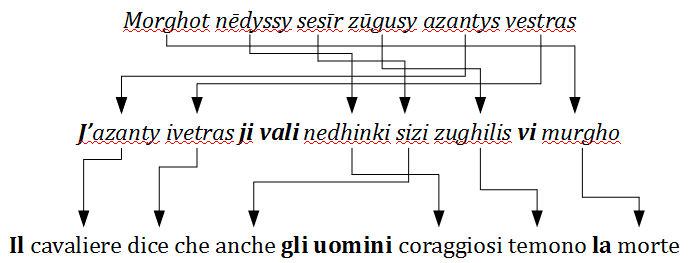

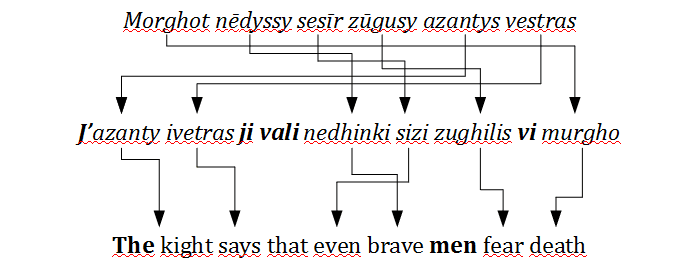

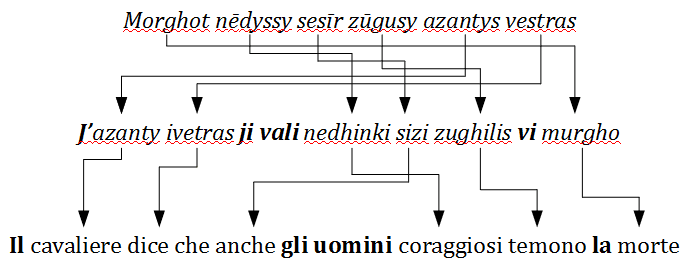

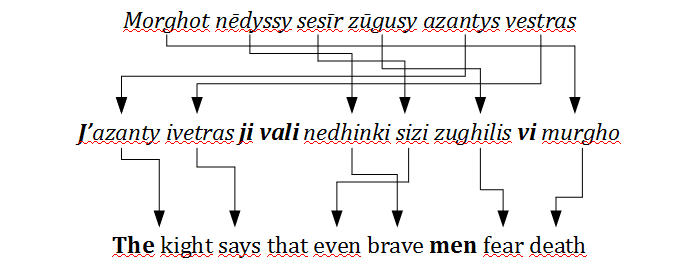

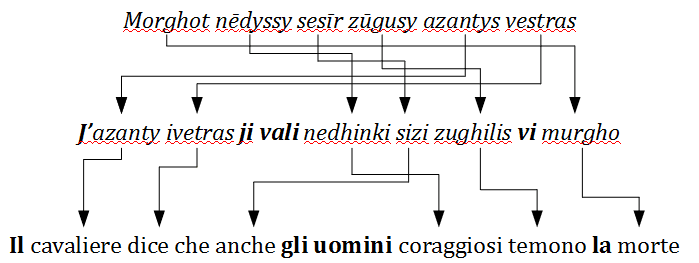

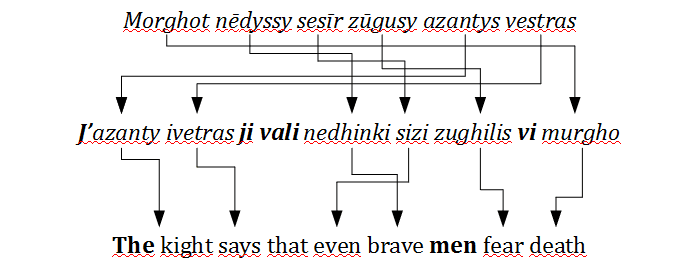

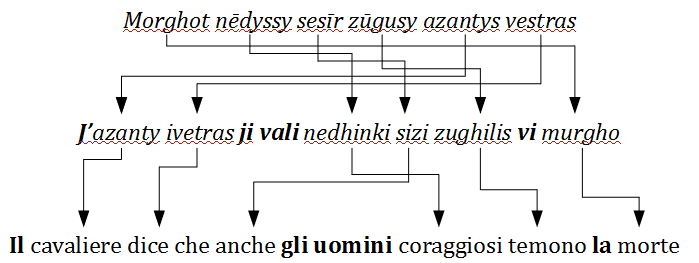

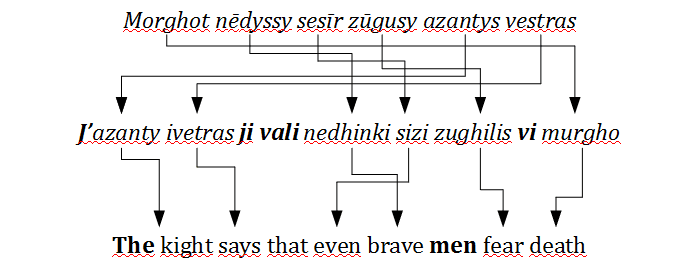

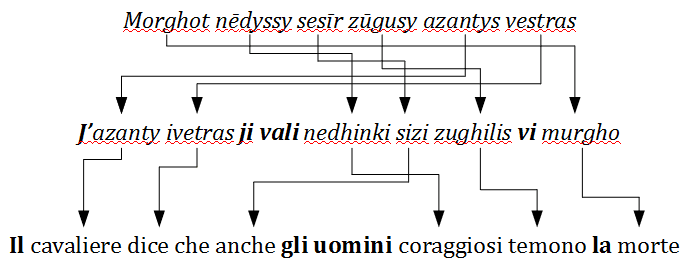

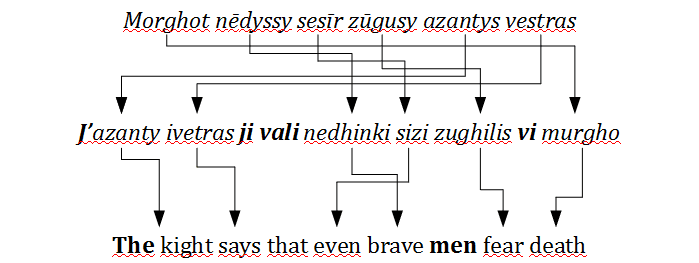

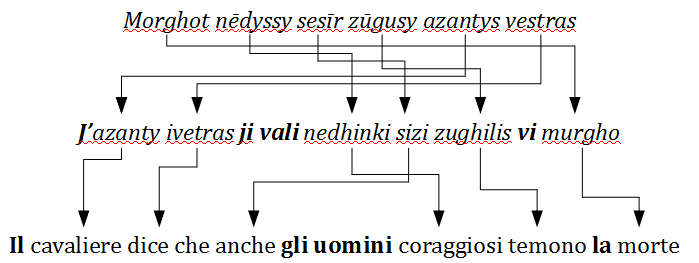

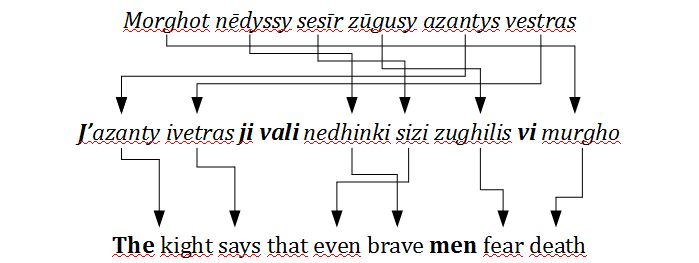

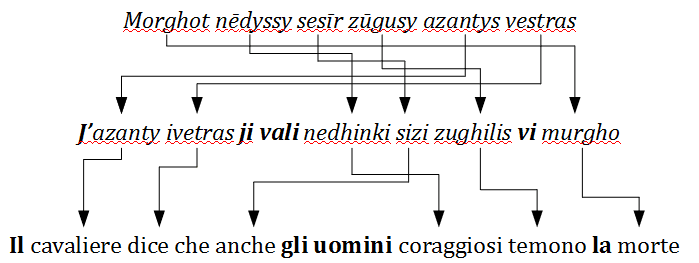

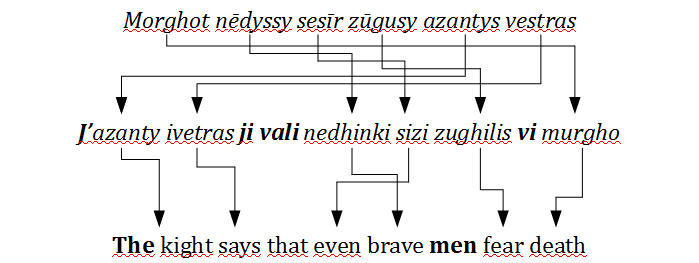

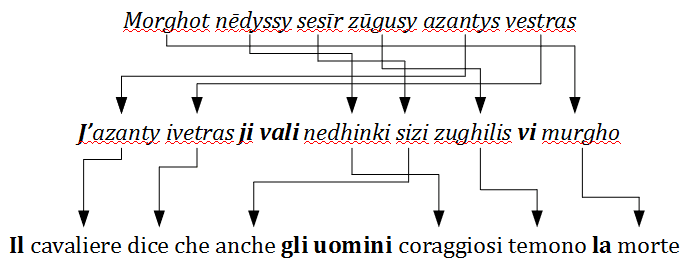

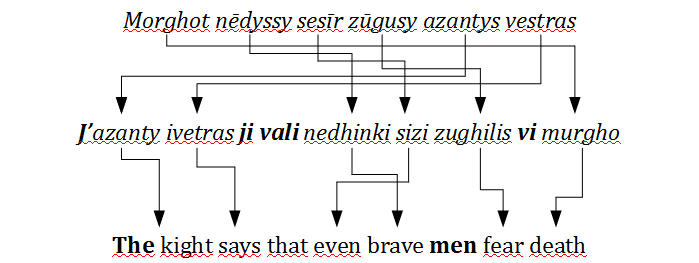

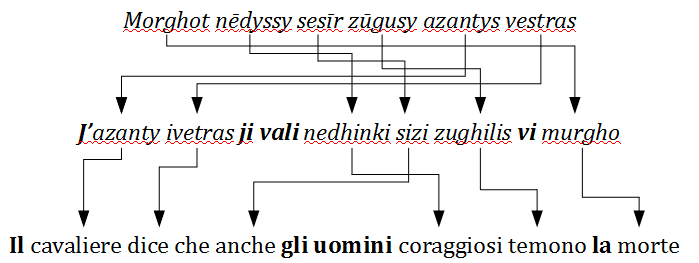

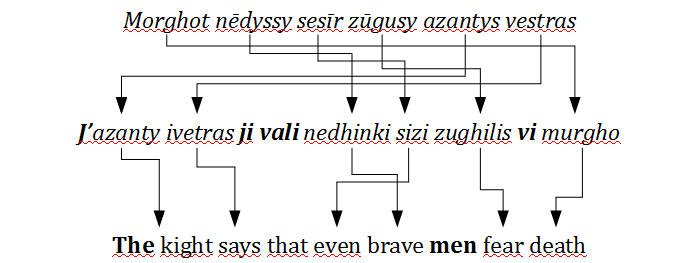

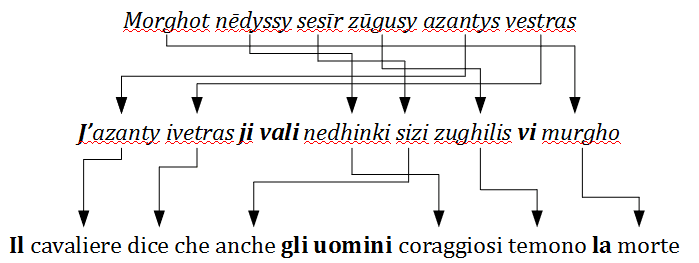

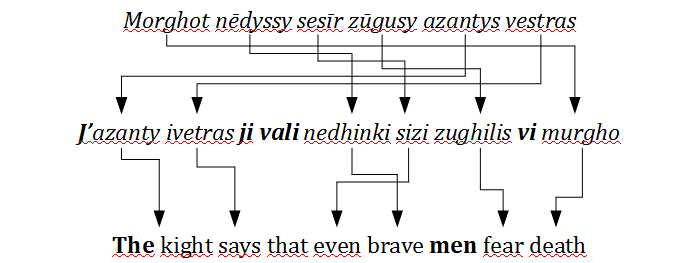

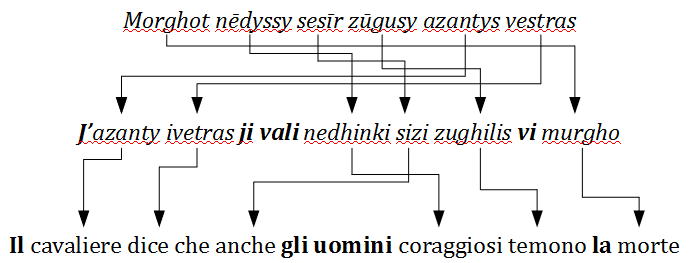

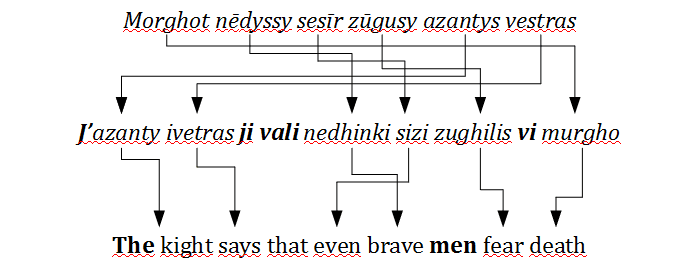

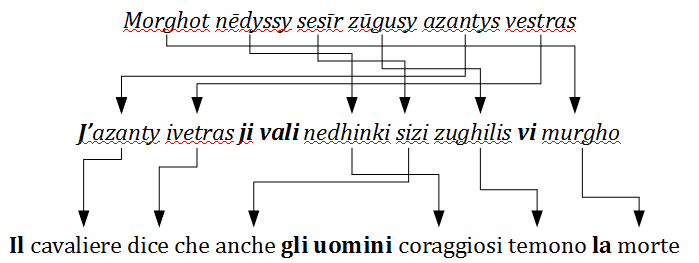

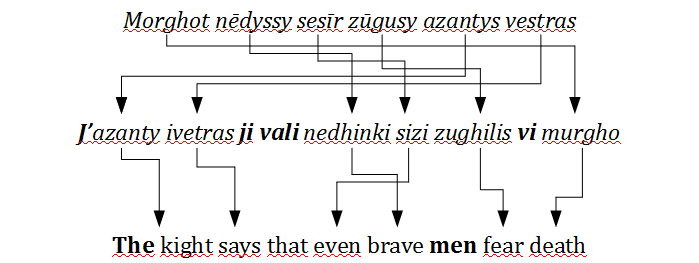

vasto numero di nomi propri. I due elementi che più hanno aiutato Peterson sono

state due frasi: Valar morghulis e Valar dohaeris, rispettivamente “tutti gli uomini

devono morire” e “tutti gli uomini devono servire”. Queste espressioni hanno

costituito il punto di partenza dell’alto valyriano, la cui pianificazione è iniziata con la

stesura della struttura verbale e del sistema numerico.

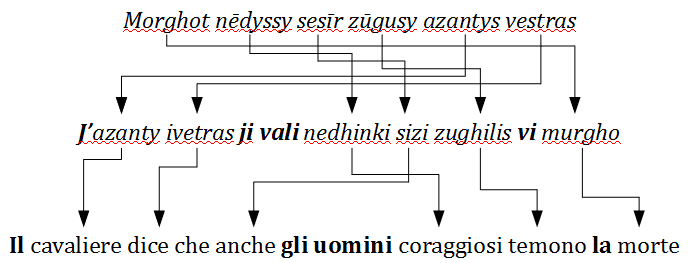

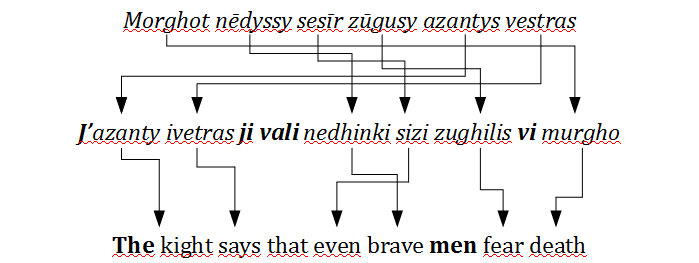

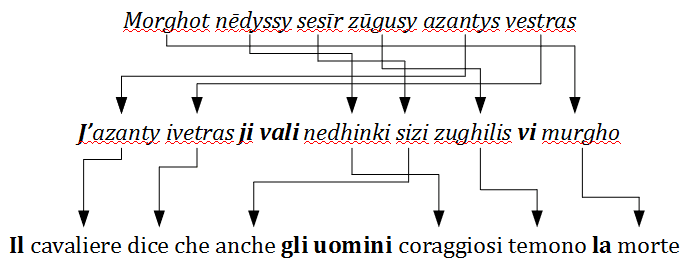

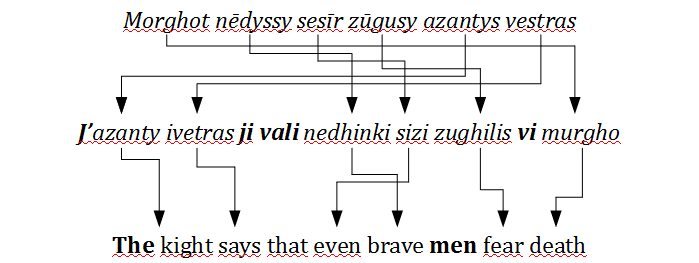

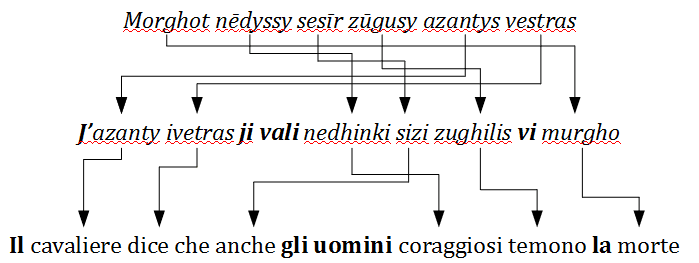

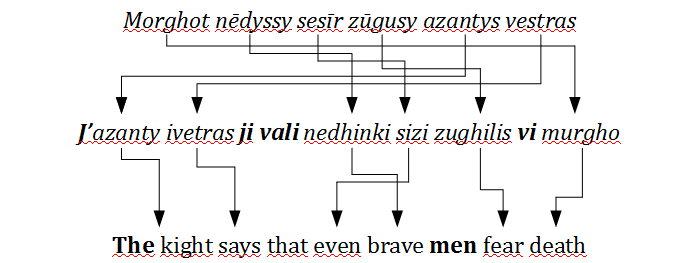

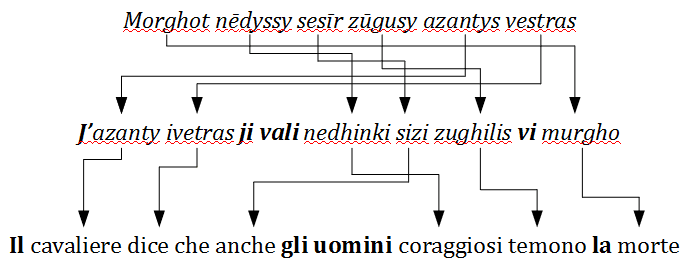

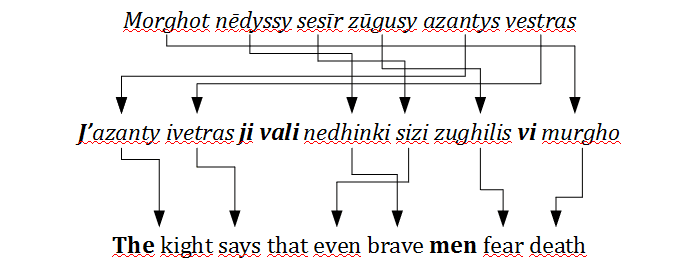

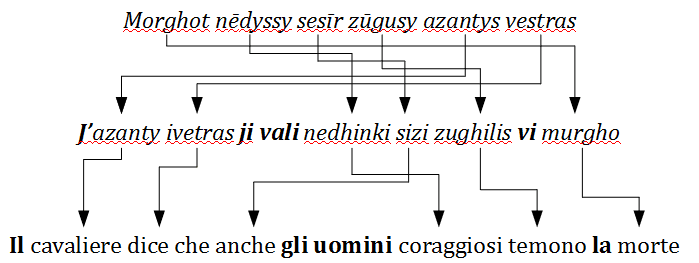

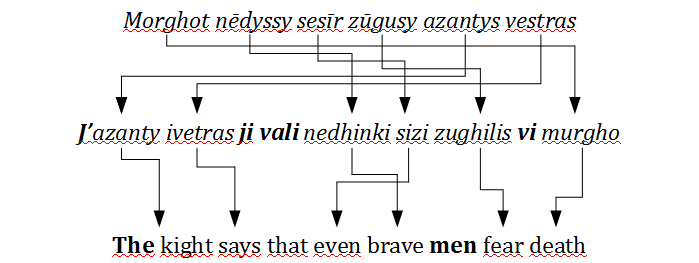

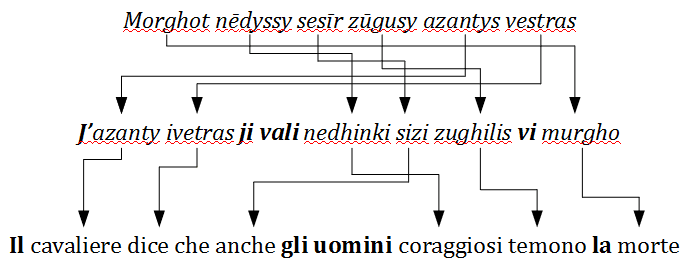

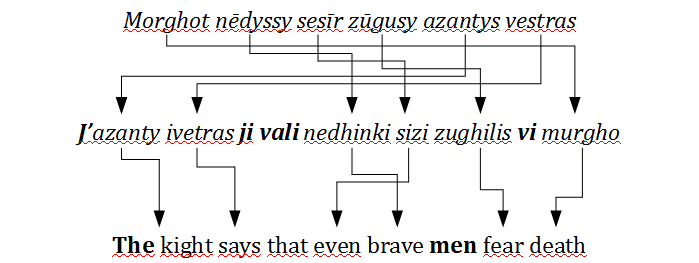

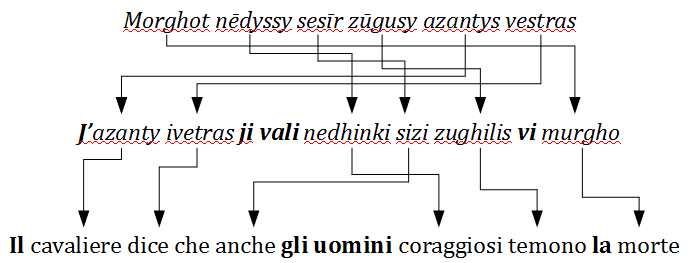

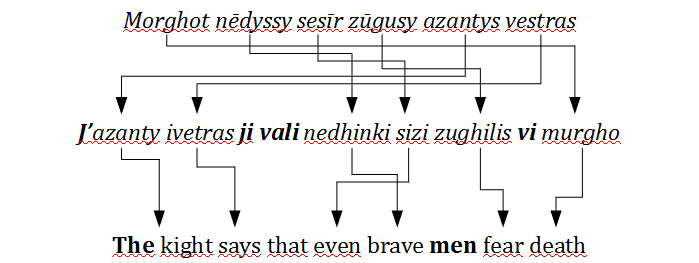

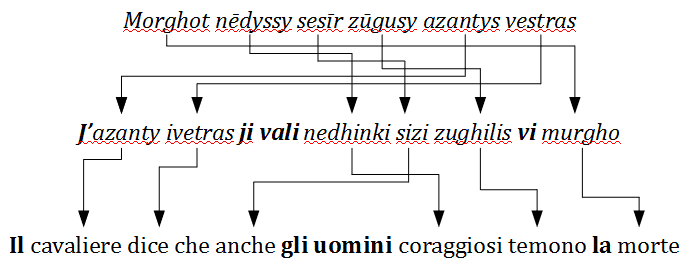

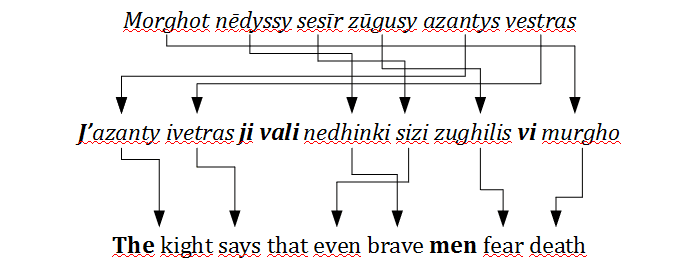

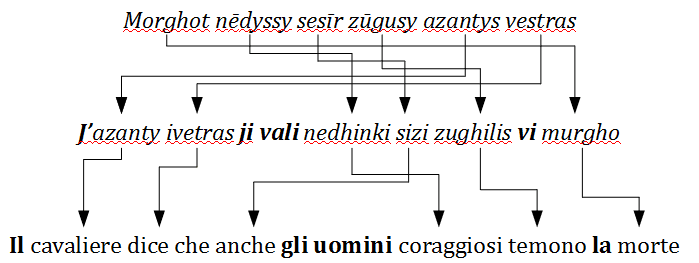

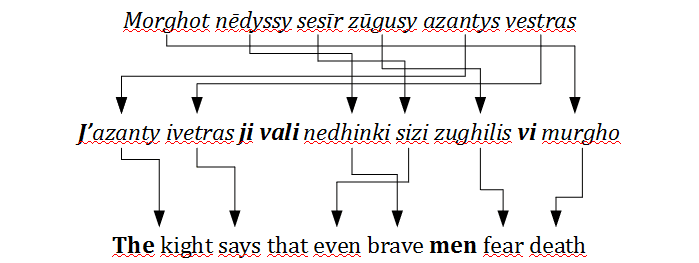

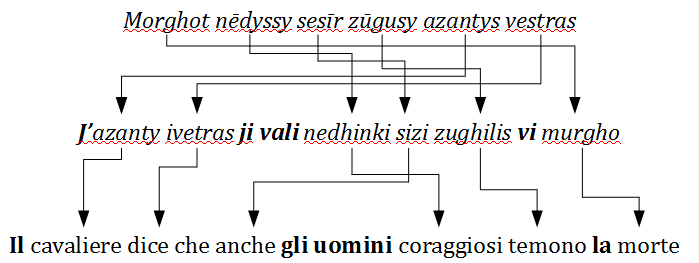

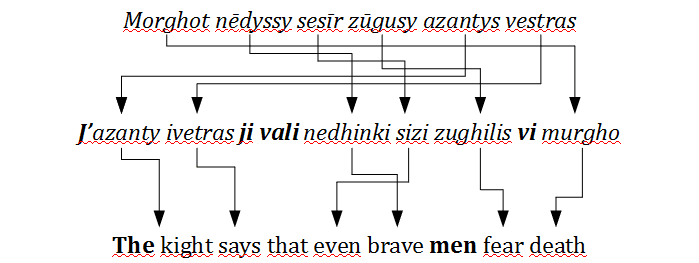

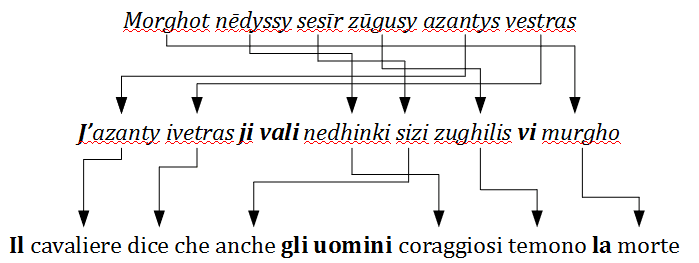

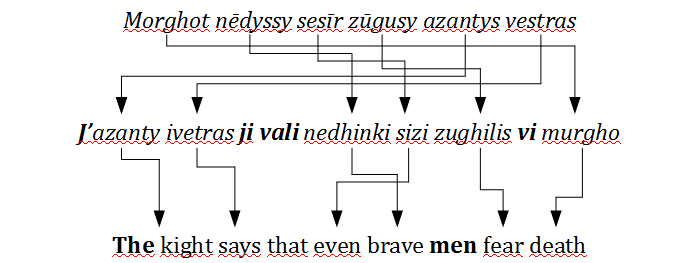

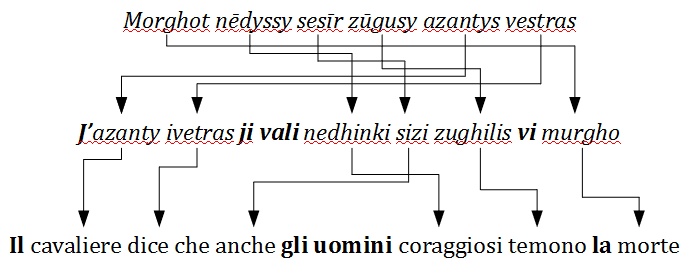

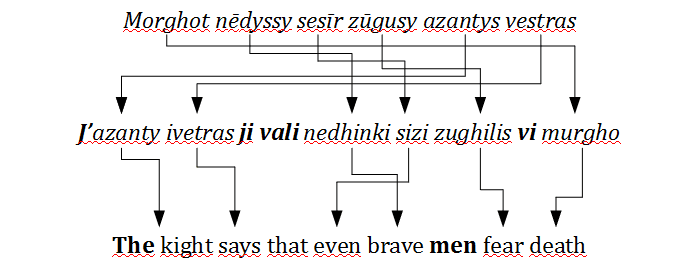

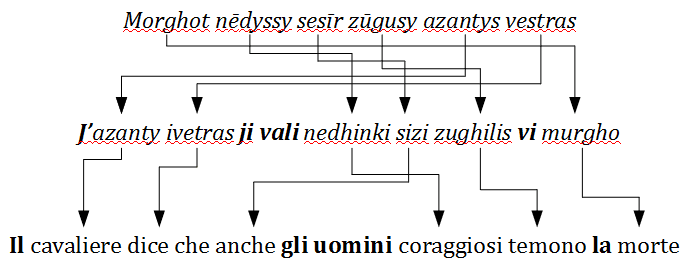

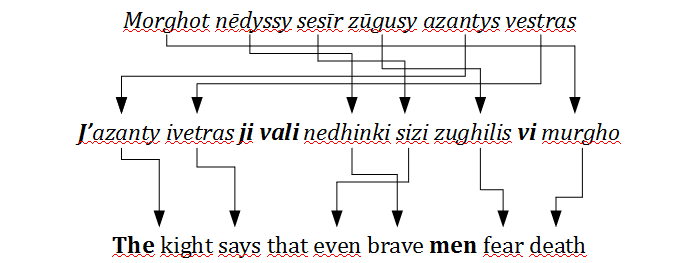

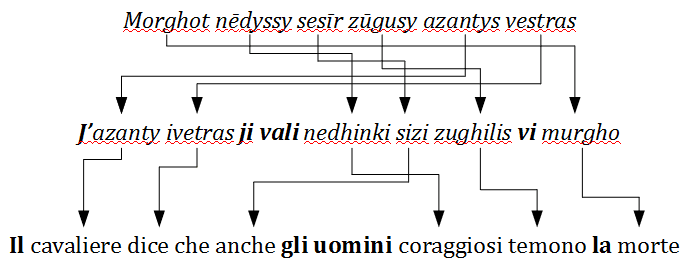

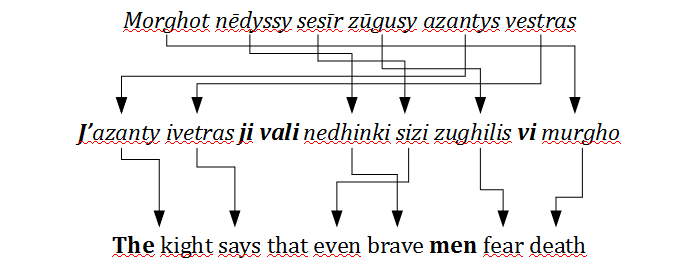

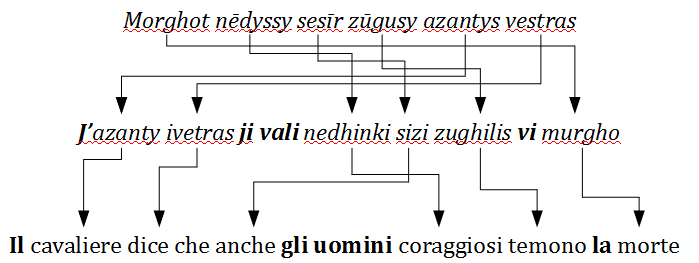

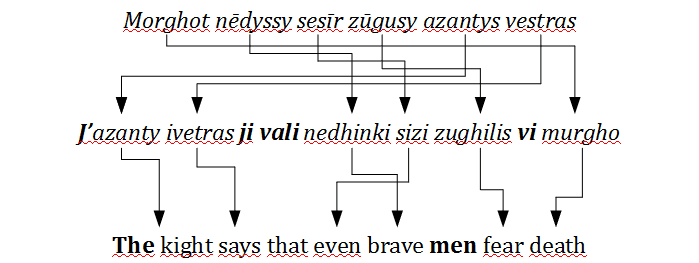

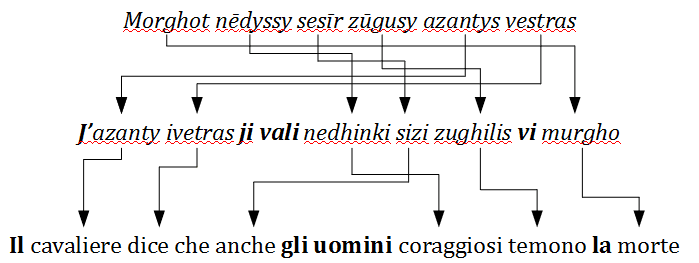

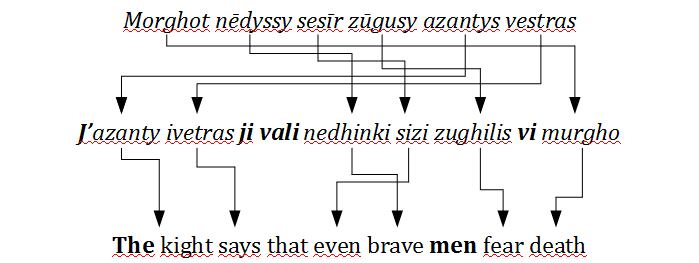

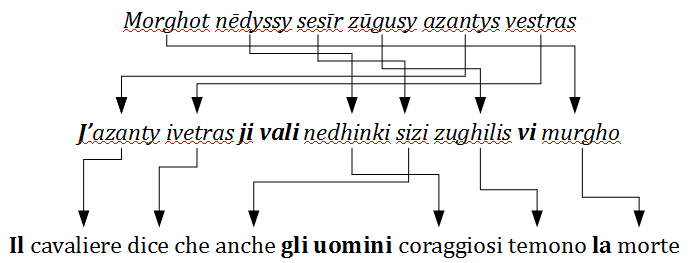

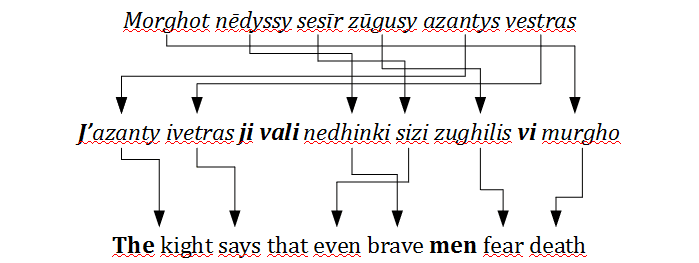

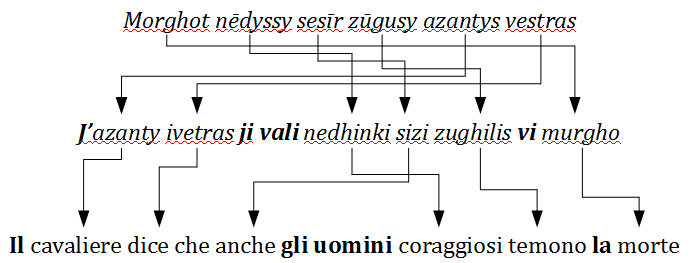

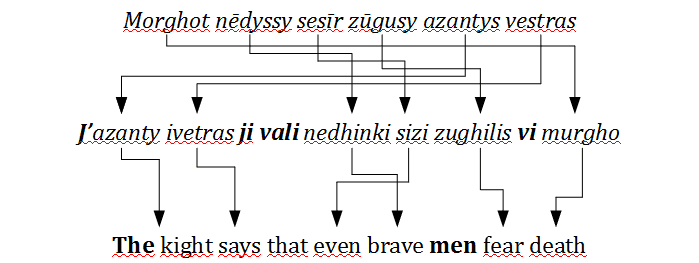

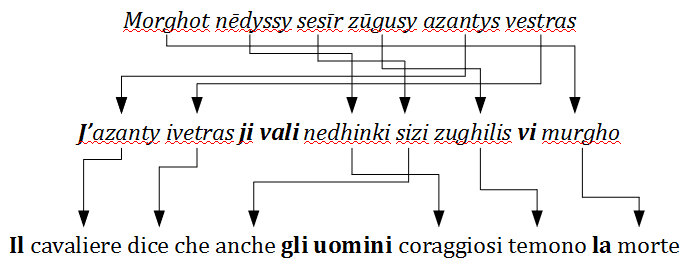

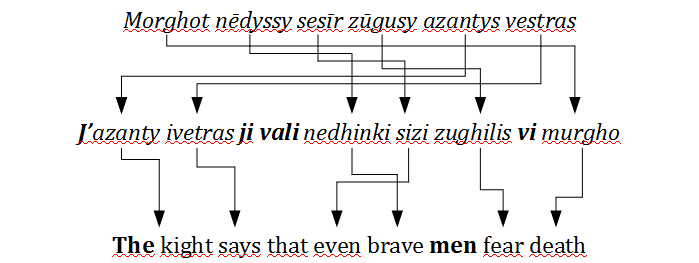

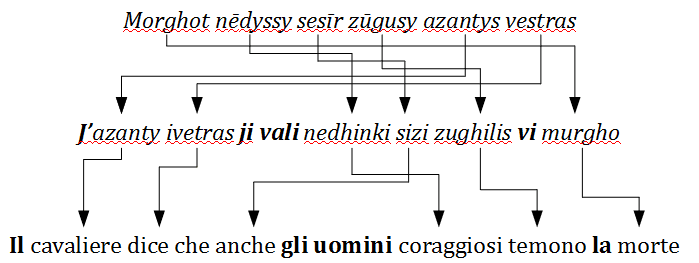

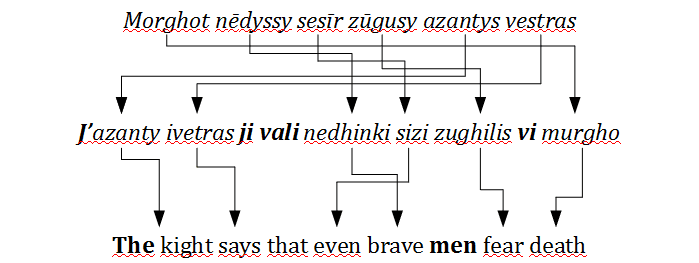

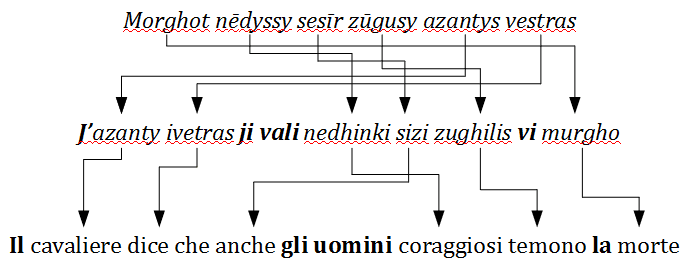

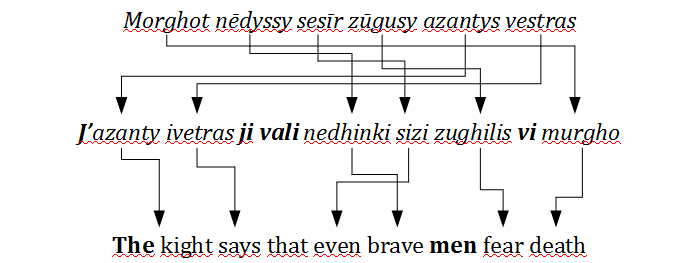

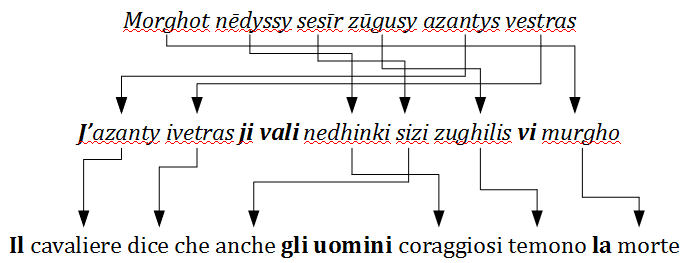

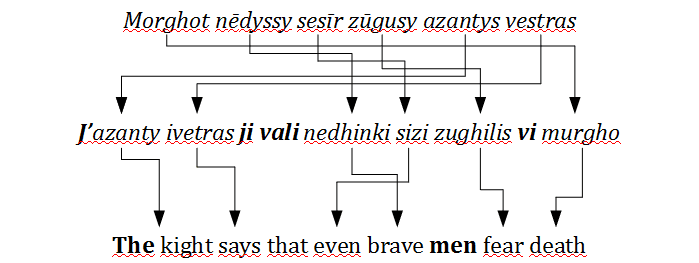

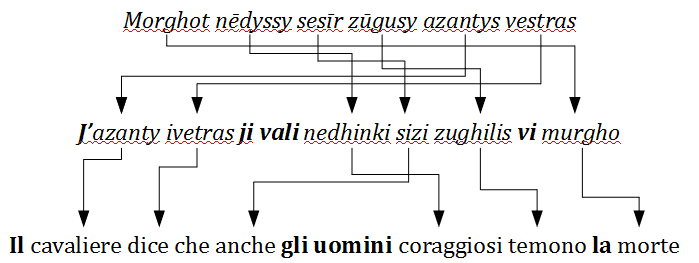

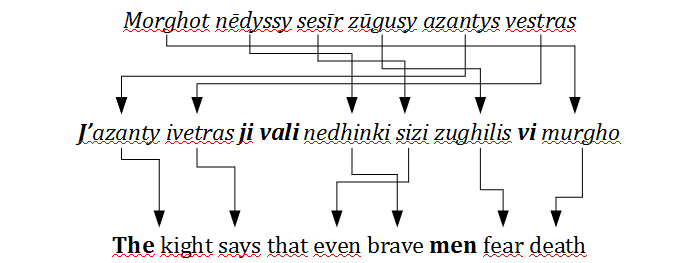

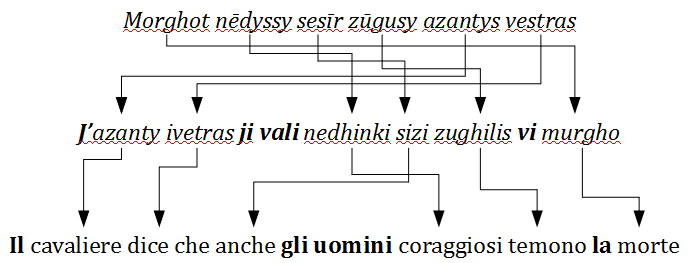

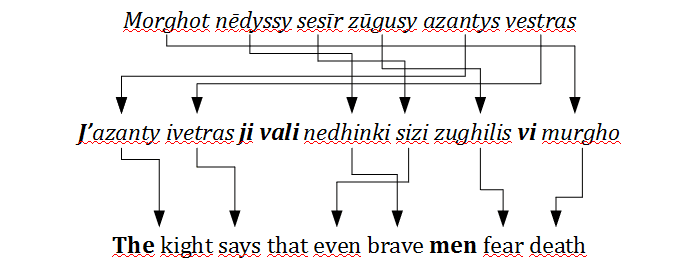

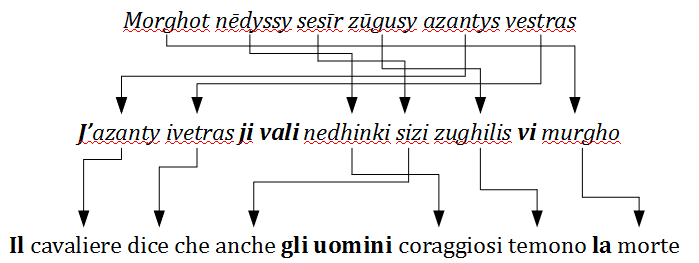

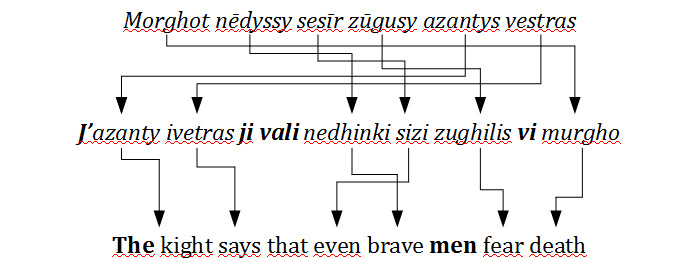

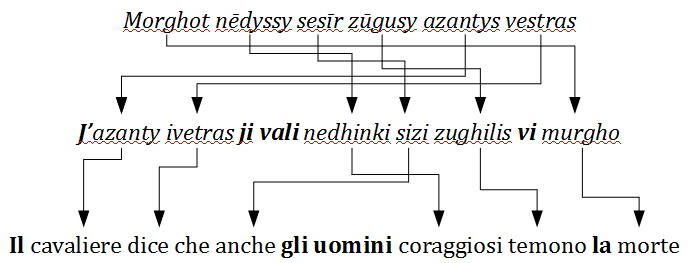

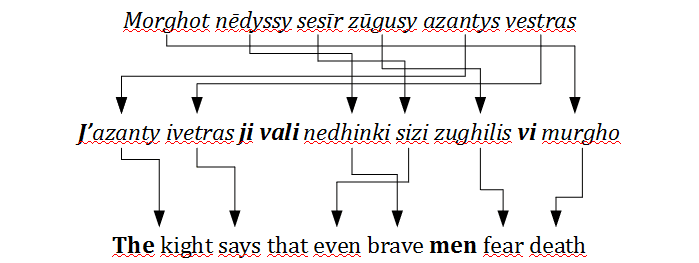

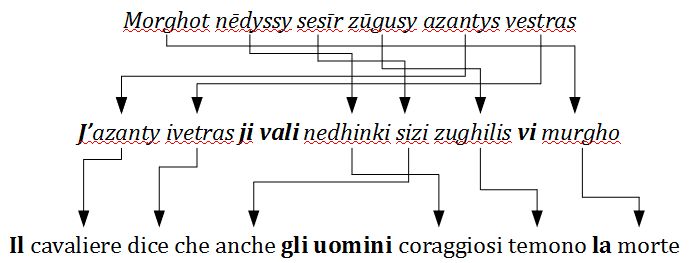

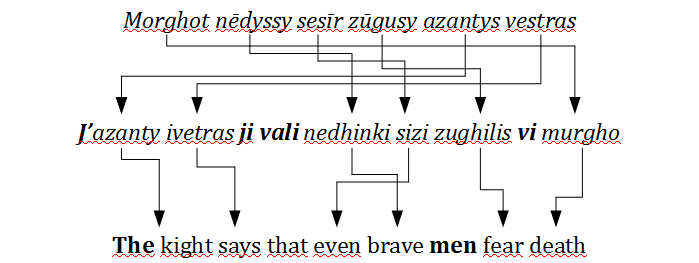

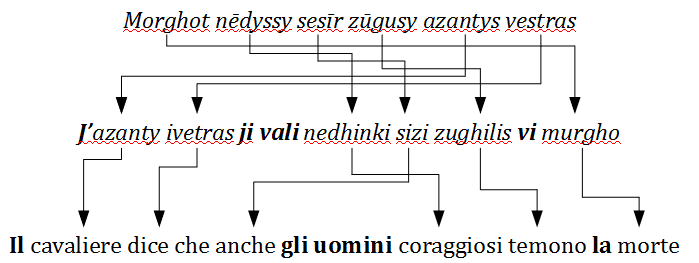

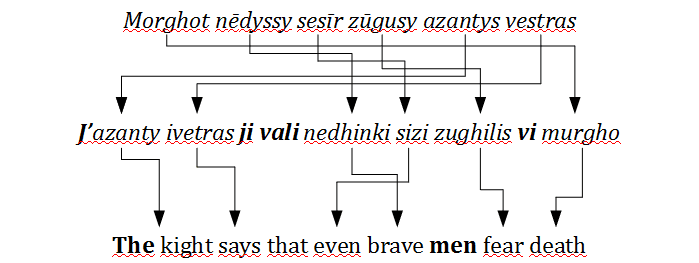

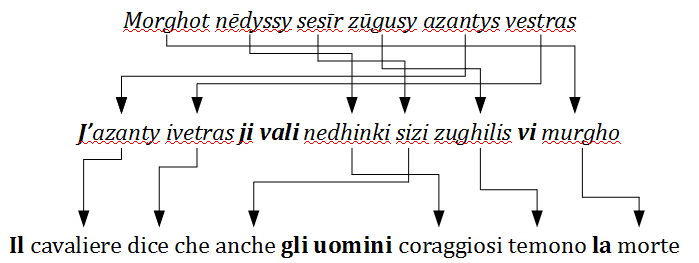

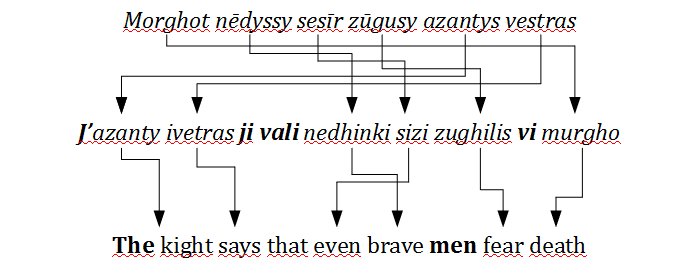

Osservando queste due frasi e le rispettive traduzioni, Peterson decise innanzitutto

che la parola valar avrebbe avuto il significato di “tutti gli uomini”, mentre morghulis

e dohaeris avrebbero dovuto corrispondere a “devono morire” e “devono servire”. Est

l’inglese (all men must die/serve) che l’italiano (tutti gli uomini devono

morire/servire) si servono di più parole per esprimere lo stesso concetto. Pensando

dunque a una traduzione letterale, in alto valyriano mancherebbero degli elementi

linguistici a cui far corrispondere il pronome indefinito “tutti” e il verbo “devono”.

Per essere precisi, in italiano è presente anche l’articolo “gli”, ma Peterson,

influenzato dalla sua lingua madre, non si è posto il problema della sua assenza.

Come spiega egli stesso, decise di rielaborare alcune caratteristiche del latino per

giungere alla soluzione (Peterson, 2015, p. 201). Il motivo per cui scelse proprio il

latino e non un’altra lingua risiede nelle affinità che trovava tra la storia dell’Impero

38

romano e quella della Libera Fortezza di Valyria, nome dell’antico impero valyriano.

La Libera Fortezza, posta nel continente orientale chiamato Essos, era un grande

impero che nei secoli aveva conquistato larga parte del continente, arrivando persino