Donald Herbert Davidson: Mind and Action

Donald Davidson was a 20th century American philosopher whose most profound influences on contemporary philosophy were in the philosophy of mind and action. This article examines in detail two leading motifs in Davidson’s philosophy. One is that mental phenomena resist being “captured in the nomological net of physical theory.” Davidson claims there are no strict deterministic laws on the basis of which mental events can be predicted and explained. He rejects all deterministic, non-normative laws connecting either mental states with physical states or mental states with other mental states. The other motif concerns the problem of analyzing the explanatory force of an agent’s reasons for his or her actions. It is Davidson’s contention that explanation by appeal to reasons is a form of causal explanation, because this is the only way to account for the fact that we have many reasons for acting the way we did, but only one of them is the reason we acted that way.

Davidson’s argument that mental phenomena cannot be captured by strict, deterministic scientific laws as they are normally understood depends upon his treatment of propositional attitudes, attitudes of hoping that p, or fearing that p, or believing that p, where p is some proposition. Propositional attitudes have certain features that distinguish them from physical states and events, says Davidson. For Davidson there is no “underlying mental reality whose laws we can study in abstraction from the normative and holistic perspectives of interpretation.” His theory of propositional attitudes is guided by conclusions drawn from the project of Radical Interpretation, a project initiated by W.V.O. Quine, Davidson’s teacher. Quine challenged two central tenets of Logical Positivism: reductionism and the analytic/synthetic distinction. Following in Quine’s footsteps, Davidson does away with what he considers to be the third and last dogma of empiricism: the dogma of the dualism of scheme and reality.

Table of Contents

Life and Influences

Mind

Anomalism of the Mental

Propositional Attitudes

No Psychophysical Laws

No Psychological Laws

Action

References and Further Reading

Primary Sources

Secondary Sources

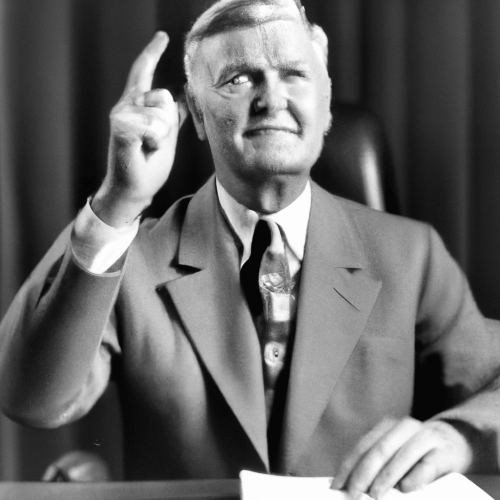

1. Life and Influences

Donald Davidson was born on March 6, 1917 in Springfield, Massachusetts. He studied English, Comparative Literature and Classics in his undergraduate years at Harvard, and in his sophomore year he attended two classes that made a lasting impression on him. These were two philosophy classes taught by Alfred North Whitehead in the last year of his career. Afterwards, Davidson was accepted to graduate studies in philosophy at Harvard, where he studied under Willard Van Orman Quine. Quine set Davidson on a course in philosophy quite different from that of Whitehead. Subsequently, Davidson did his dissertation on Plato’s Philebus.

According to Davidson, “The central thesis that emerged was that when Plato had reworked the theory of ideas as a consequence of the explorations and criticisms of the Parmenides, Sophist, Theaetetus, and Politicus, he realized that the theory could no longer be deployed as a main support of an ethical position, as it had been developed in the Republic and elsewhere.” This dissertation reveals the development of Davidson’s philosophical method and his epistemological position.

Davidson’s most profound influences on contemporary philosophy stem from his philosophy of mind and action. However, Davidson’s philosophical positions in action theory and philosophy of mind are intrinsically tied into his work on the semantics of natural languages.

Davidson’s apprenticeship in philosophy took place in an intellectual milieu very different from today’s. In the Anglo-American philosophical community, the middle of the century was dominated by Logical Positivism. Davidson recalls that he got through graduate school at Harvard by reading an anthology of Logical Positivism by Feigl and Sellars. Logical positivism emerged in the Austro-Hungarian Empire early in this century. Influenced by the logicist project of Bertrand Russell and Gottlob Frege on the one hand, and by advances in science on the other, the Logical Positivists of the Vienna Circle turned to physics as a model of theoretical discourse; and they considered sensory experiences to be fundamental. Although Logical Positivism was not entirely a unified movement, the Verification Principle was shared by most of them. It states that the meaning of sentences can be accounted for in terms of experiences that would verify them. Logical Positivism usually promotes a reductionist program: the reduction of all special sciences to physics, and of all meaningful statements to reports about sensory experiences. In his famous paper, Two Dogmas of Empiricism, Davidson’s teacher Quine challenged two central tenets of Logical Positivism: reductionism and the analytic/synthetic distinction. Following in Quine’s footsteps, Davidson does away with what he considers to be the third and last dogma of empiricism: the dogma of the dualism of scheme and reality. See his paper “On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme.”

Of the two leading motifs in Davidson’s mature philosophy discussed in this article, one has to do with the fact that mental phenomena resist being “captured in the nomological net of physical theory.” Davidson rejects strict psychophysical and psychological laws. The other motif concerns the problem of analyzing the explanatory force of an agent’s reasons for his or her actions. It is Davidson’s contention that explanation by appeal to reasons is a form of causal explanation.

2. Mind

a. Anomalism of the Mental

Simply put, “anomalism of the mental” amounts to the claim that the mental is not governed by laws as we usually understand them. In Davidson’s own words:

There are no strict deterministic laws on the basis of which mental events can be predicted and explained.

In developing his position, Davidson attempts to retain his materialism while at the same time to avoid a reductionism. Usually reductionism has been held to have followed from materialism. When Davidson asserts that there can be no laws on the basis of which mental events can be predicted and explained, he has two different types of laws in mind. In the first type of law, an attempt is made to link mental states and events with physical states and events, and the law is used to explain the former on the basis of the latter. Davidson spends much of his effort in Mental Events showing the impossibility of such psychophysical laws. In the second type of law, there is an attempt to formulate strict deterministic laws linking mental states and events to other mental states and events. Davidson denies the possibility of these psychological laws as well. Davidson’s latter claim is considered to be a rejection of the most basic goal of the science of psychology.

In arguing against the possibility of psychophysical laws, Davidson has in mind the following kinds of laws:

(BL) ∀x (x is in M iff x is in P)

where M denotes some mental state or event and P denotes some physical state or event and “iff” abbreviates “if and only if.” The laws of the above kind are known as bridging laws (BL). A stronger version of a bridging law claims identity of properties from different theoretical discourses. A weaker version claims only that whenever an object instantiates one property it instantiates the other. An important distinction between laws and generalizations must be made. There has been general agreement among philosophers, Davidson included, that a law is distinguished from a mere generalization by the following features:

A law must support counterfactual claims. A law of the form “All A are B,” for instance, is said to sustain the claim that if any arbitrary x were, contrary to fact, an A, it would also be B.

It must be capable of confirmation by observable instances.

To illustrate the difference between generalizations that just happen to be true, and real laws, consider the following story (adopted from Jaegwon Kim). Assume that all objects in a fixed domain, for instance all objects in my room, are either blue or red. In addition, all of the above objects are considered either edible or inedible. By some coincidence it so happens that all red objects in my room are edible. Perhaps the red objects in my room are either ripe tomatoes or ripe cherries. This allows us to form a true generalization about this fixed domain:

(G) If x is red then x is edible.

It is obvious that (G) does not support counterfactual conditionals. For instance (G) does not allow us to infer of some green object (say a copy of Davidson’s Essays on Actions and Events) that if it were red it would be edible. Davidson is quite explicit that his attack is aimed at psychophysical laws not at true psychophysical generalizations:

The thesis is rather that the mental is nomologically irreducible: there may be true general statements relating the mental and the physical, statements that have the logical form of a law; but they are not lawlike (in a strong sense to be described). If by absurdly remote chance we were to stumble on a non-probabilistic, true, psychophysical generalization, we would have no reason to believe it more than roughly true; we would have no reason to believe it was a law.

Following this view, it is important to keep in mind the fact that whether any given psychophysical generalization is true is a contingent, empirical matter. As we will see later, it is an a priori matter for Davidson that no such generalization can be a law.

The core idea of Davidson’s argument against the possibility of psychophysical laws can be found in the following passage:

Nomological statements bring together predicates that we know a priori are made for each other — know, that is, independently of knowing whether the evidence supports a connection between them. If we can know a priori when the predicates are made for each other, then we can know by the same token when they aren’t. Davidson finds that it is an a priori truth that mental and physical predicates are not made for each other. Here is the structure of his argument.

Both mental and physical phenomena have distinct sets of features characteristic of their own domains, but these features are incompatible with each other.

Bridging laws linking properties from two distinct theoretical discourses (in this case mental and physical) would transmit properties from one discourse to another, which in case of mental and physical phenomena would lead into incoherence.

Therefore, there could be no psychophysical laws linking mental and physical phenomena.

b. Propositional Attitudes

According to Davidson, the paradigmatic criterion of the mental events is their susceptibility to the description “in terms of vocabulary of propositional attitudes.” Propositional attitudes, or intentional states as they are sometimes called, are various cognitive attitudes; we can have hope that the proposition p is true, we can fear that p is true, we can desire that p is true, and so forth. You and I can have different attitudes toward the proposition “Snow is white.” I hope that snow is white, whereas you believe that it is but don’t hope it is. The proposition itself, namely, that snow is white, towards which one has an attitude is said to give the content to one’s mental state.

Propositional attitudes have certain features (or are constrained by certain principles) that distinguish them from physical states and events. Davidson’s theory of propositional attitudes is guided by conclusions drawn from the project of Radical Interpretation, a project initiated by Quine. Imagine that you have encountered a group of people in an unfamiliar land who display what appear to you to be shared verbal and non-verbal behavior. What do they mean when they point at a rabbit running by and say, “Gavagai”? Interpreting their behavior by assigning meaning to their actions (of which linguistic utterances is a subclass) is the task of Radical Interpretation. The principles and techniques we would apply in the above described situation are not unlike the principles and techniques we commonly apply in interpretation of other people’s actions and utterances whose language we already share. Radical Interpretation, according to Davidson, is guided by normative principles and must proceed holistically:

This method is intended to solve the problem of the interdependence of belief and meaning by holding belief constant as far as possible while solving for meaning. This is accomplished by assigning truth conditions to alien sentences that make native speakers right when plausibly possible, according, of course to our own view of what is right.

These general normative principles that guide the task of Radical Interpretation, and therefore constrain the task of attribution of propositional attitudes, are principles such as “Don’t believe an open contradiction”, or “If you believe that p and q, then also believe that p.” It is important to keep in mind the fact that intentional states are capable of justifying other intentional states. In physical theory the movement of one ball is explained by the movement of the other. Having a belief that pressing on a lever will stop the flow of water doesn’t just explain my action of stopping the flow of water. This belief (together with the desire to stop the flow of water) also justifies my action in the sense that it makes it reasonable in the light of the above belief. (Intentional states justifying other intentional states will be discussed further in the second part of this article.) Davidson is explicit that it is a part of what it is for something to be a propositional attitude (like a belief) that it be subject to these normative principles. This makes these principles a priori and necessary constitutive of the concept of propositional attitudes. In contrast, our knowledge of things physical is a posteriori and contingent in nature.

So far, we have spent time explaining the normative character of the mental and have discussed that the interpretation must proceed holistically:

There is no assigning beliefs to a person one by one on the basis of his verbal behavior, his choices, or other local signs no matter how plain and evident, for we make sense of particular beliefs only as they cohere with other beliefs, with preferences, with intention, hopes, fears, expectation, and the rest.

It can be seen from the above remark that interpretation is holistic in the sense that the attribution of each individual mental state to another person must be made against the background of attribution of other mental states. In addition, the attribution to an agent of the entire system of propositional attitudes is further constrained by considerations that involve maximization of coherence and rationality.

c. No Psychophysical Laws

Davidson is quite aware of the fact that holism and interdependence are common to physical theory. In physical theory such a priori facts as the transitivity of “longer than” is what makes physical measurements possible. Thus, the physical realm is also characterized by the a priori laws constitutive of our conception of the physical. What sets the realms of the mental and the physical apart is the disparate commitments of each realm. Rationality and the governing normative principles are essential characteristics of the mental. Thus, the absence of rationality and normative principles is a characteristic of the physical. If there were bridging laws, we would find, unhappily, that the characteristics of the mental that have “no echo in physical theory” would be transmitted to the physical and vice versa. In the first of the above scenarios we would have to apply the Principle of Charity with its rule of maximization of coherence and rationality to the physical, which, according to Davidson, is plainly absurd. In the second scenario we would have the principles governing the attribution of the mental be preempted by the merely physical constraints. This happens for the following reason: if there were bridging laws of the type (BL), then neural states of the brain would be nomologically coextensive with certain intentional states. But neural states (being theoretical states of physical theory) are governed by conditions of attribution that in turn are regulated by the constitutive rules of the physical theory. Thus, constitutive rules of the mental are ignored in this scenario. Davidson concludes that:

There are no strict psychophysical laws because of the disparate commitments of the mental and physical schemes. It is a feature of physical reality that physical change can be explained by laws that connect it with other changes and conditions physically described. It is a feature of the mental that the attribution of mental phenomena must be responsible to the background of reasons, beliefs, and intentions of the individual. There cannot be tight connections between the realms if each is to retain allegiance to its proper source of evidence.

It is important for Davidson to note that the mental does have its own laws, for instance, the laws of rational decision making. The crucial difference between such laws and the laws that could be counted as psychophysical is the difference between the normative character of the former and the predictive power of the latter. When anomalism of the mental denies the existence of psychophysical and psychological laws, the sense of “law” is taken to involve strict nomological predictions and explanations of behavior. Thus, normative “laws” are quite compatible with anomalism of the mental. An interesting question is whether Davidson’s notion of what constitutes a “law” has merit won’t be discussed here.

d. No Psychological Laws

The claim of the anomalism of the mental consists of two subsidiary claims. Thus far we have considered the support for the claim that there are no psychophysical laws. Davidson also defends the claim that there could be no precise psychological laws, that is, there are no precise laws that relate mental states and events to other mental states and events. The argument for this claim can be found in “Psychology as Philosophy.” As the title suggests, Davidson intends to contrast the claim that psychology is more like philosophy with the claim that it is more like science and then refute the latter claim. One point deserves special attention before proceeding to the exegesis of Davidson’s argument against psychological laws. Actions, although undeniably physical under some descriptions, are considered to be mental by Davidson. This is so because, when we state which action someone is performing versus merely describing the physical movement his body is undergoing, we are contributing an interpretation of him and interpretation, as we have seen, is guided by certain normative constraints. Thus, the laws that could relate an agent’s mental states to his actions would count as psychological laws.

The gist of the argument against psychological laws can be found in the following passage:

It is an error to compare truisms like “If a man wants to eat an acorn omelette, then he generally will if the opportunity exists and no other desire overrides” with a law that says how fast a body will fall in a vacuum. It is an error, because in the latter case, but not the former, we can tell in advance whether the condition holds, and we know what allowance to make if it doesn’t.

If the above truism were a psychological law, then for the antecedent to obtain, the agent must want to eat an acorn omelette. But our knowledge of an agent’s desires crucially depends upon our attribution of other mental states to him (or her). In addition, knowing his action subsequent to his desire will help us interpret whether the agent had the desire in the first place. Thus both the antecedent and the consequent of the supposed psychological law are related to each other through the holism of interpretation.

What is needed in the case of action, if we are to predict on the basis of desires and beliefs, is a quantitative calculus that brings all relevant beliefs and desires into the picture. There is no hope of refining the simple pattern of explanation on the basis of reasons into such a calculus.

Since no such hope exists, any psychological generalization purporting to be law must rely upon generous escape clauses such as “if no other desire overrides,” ceteris paribus, and so forth. The necessity of such fail-safe clauses is dictated by the fact that for Davidson there is no “underlying mental reality whose laws we can study in abstraction from the normative and holistic perspectives of interpretation.”

3. Action

Actions, according to Davidson, are events. Events, in his ontology, are particular dated occurrences; the essential feature of which is susceptibility to redescription. In order to admit an entity into one’s ontology, one must specify the conditions of individuation for that entity. On Davidson’s view:

[E]vents are identical if and only if they have exactly the same causes and effects.

This criterion may seem to have an air of circularity about it, but if there is circularity it certainly is not formal. For the criterion is simply this: where x and y are events,

x = y if and only if [(z) (z caused x implies z caused y) and (z) (x caused z implies y caused z)].

It is important to keep in mind that for an event to be an action, the event must be describable in a specific way. Actions are events that people perform with intentions and for reasons. One and the same action can be specified as intentional under some description and as purely physical under another description. But in order to be an action an event must have at least one description under which it is specified as intentional. The above requirement for an action hinges on the larger distinction between specifying the whole of an event with wholly specifying it. The distinction comes up in the context of the discussion of causation and causal explanation:

The salient point that emerges so far is that we must distinguish firmly between causes and the features we hit on for describing them, and hence between the question whether a statement says truly that one event causes another and the further question whether the events are characterized in such a way that we can deduce, or otherwise infer, from laws or other causal lore, that the relation was causal.

In the case of one event causing another, any description that picks out the right event specifies the whole of the cause. Some descriptions, of course, will be richer in the information they disclose about an event. This richness should not affect in any way how much of a cause they refer to. The story is quite different when it comes to what Davidson calls “the further question” of causal explanation. Causal explanations are by their very nature attempts to explain events in terms of the causes of these events. But, according to Davidson, causal explanations are, in addition, sensitive to how the events in question are described. For instance, the two descriptions “Jack’s walking in the room” and “Jack’s stomping in the room” may refer to the same event that caused Jill to wake up. However the latter may serve as a causal explanation of Jill’s waking up, whereas the former may not.

One of Davidson’s major contributions to philosophy of action is his claim that explanation via reasons is a form of causal explanation. In order to understand Davidson’s claims that reasons are the causes of the actions that they are reasons for and that “reason explanation” is a form of causal explanation, we must understand how on his view causal explanation works.

One theory of causal explanation arises out of Hume’s position that wherever there is a causal relation between two distinct events a and b there must be a law relating two types of events A and B that the events in question instantiate. This position has been further developed in the middle of the twentieth century by Carl Hempel into the deductive-nomological theory of explanation (DN from now on). According to DN, an event E is causally explained just in case the statement asserting the occurrence of E deductively follows from

the statement asserting the occurrence of its cause C , and

the statement of some general causal law L.

The opponents of the DN model argue that one can judge that an event a caused an event b without knowing the laws that these events instantiate. Davidson contends that the opposition between the opponents and the champions of the DN model is more apparent than real. The solution to the conflict depends on the distinction between events and their descriptions:

Causality and identity are relations between individual events no matter how described. But laws are linguistic; and so events can instantiate laws, and hence be explained or predicted in the light of laws, only as those events are described in one or the other way.

In short, Davidson lends his support to the principle of Nomological Character of Causality. This principle says that “when events are related as cause and effect, they have descriptions that instantiate a law. It doesn’t say that every true singular statement of causality instantiates a law.” It is worth noting that Davidson accepts this principle on faith, as many commentators have pointed out. Unlike David Hume, who accepts the principle because his analysis of the nature of causation as a constant conjunction requires it, Davidson disavows analyzing the nature of causation itself. His goal, explicitly stated, is to provide an analysis of the logical form of causal statements.

We can now turn to the question of the causal explanation of action and briefly discuss Davidson’s impetus for his claim that reason explanation must be a form of causal explanation. Davidson’s opponents (the anti-causalists) on the explanation of actions claim that reason explanation is different in kind from causal explanation. There are two main types of arguments for the anti-causalist position: methodological and conceptual. Anti-causalists who rely on methodological arguments for their position, claim that a DN model that relies on the concept of lawful regularity has a place only in the physical sciences. By contrast, the primary constraint placed on explanation in the social sciences is a normative one. Thus, lawful regularities relating reasons to actions would be simply irrelevant to explanation in social sciences, according to anti-causalists.

Conceptual arguments are meant to establish the stronger claim that reasons cannot in principle be causes. One plausible argument of the conceptual variety rests on the assumption that “the presence of a reason cannot be ascertained independently of the occurrence of the action it rationalizes.” This, presumably, leads to the disparate evidential commitments of the causal explanation and reason explanation. Davidson himself appears to advocate the above point in the passage quoted above. Thus, all arguments against the causalist position, including the ones briefly mentioned, revolve around the normative constraints placed on the explanation of the mental.

In short, an explanation of an agent’s action can be considered adequate only if it shows the action in question to be reasonable against the background of an agent’s beliefs and desires. This latter condition together with the truth condition, which states that the propositional attitudes a rationalization attributes to an agent must be true, form the necessary conditions for the justification model of explanation. Davidson considers the above conditions necessary but not sufficient. The deficiency of the justification model is explained by drawing attention to the distinction between having a reason for an action and having the reason why one performs an action. For a reason to be the reason why one performs an action the reason must cause the action. For example, one has a reason to turn on the television, say, to watch one’s favorite TV show. But this need not be the reason why one turns on the television. This is because the above reason did not cause one to turn on the television. As Davidson puts it:

[S]omething essential has certainly been left out, for a person can have a reason for an action, and perform the action, and yet this reason not be the reason why he did it.

In our example, the reason for one to turn on the television, let’s say, is that one is lonely and desires company. Thus, one reason (namely, to keep one company) was the cause of the action while the other reason (namely, to watch one’s favorite show) was not. Davidson continues:

Of course, we can include this idea too in justification; but then the notion of justification becomes as dark as the notion of reason until we can account for the force of that “because.”

The mere possibility that a person acted on the basis of one reason rather than another presents an insurmountable obstacle. The anti-causalist has no way of accounting for the force of the “because” in the rationalization. Thus, the justification model is silent on what would count as the correct rationalization. The only solution, according to Davidson, is to view the efficacious reasons (the ones that account for the correct rationalization) as causes of action. This leaves us, according to Davidson, with only one alternative to justificationalism, namely, the view that reason explanation is a species of causal explanation.

4. References and Further Reading

Davidson’s research primarily ran in articles published from the 1960s through the 1990s, most of which have conveniently been reprinted. The first two collections contain Davidson’s most influential works, and the last volume cited below is a good place to begin. [This section on references and further reading was composed by Paul Saka.] See also the article Davidson: Philosophy of Language.

a. Primary Sources

Essays on Actions and Events. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980.

Includes “Mental Events,” which introduces anomalous monism; “The Logical Form of Action Sentences,” an important semantic theory of adverbs; “Actions, Reasons, and Causes”, which famously argues that rationalization is a species of causal explanation. To the revised edition (2001) is added “Adverbs of Action” and a short reply to Quine.

Inquiries into Truth and Interpretation. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984.

Includes “Semantics for Natural Languages,” a good place for beginners to start; “Truth and Meaning,” the locus classicus of Davidsonian semantics; “Quotation” and “On Saying That,” which offer extensional analyses of intensional phenomena; “Radical Interpretation,” “Belief and the Basis of Meaning,” and “On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme” on the principle of charity; “Thought and Talk,” which argues that only verbal creatures can think; “Reality without Reference,” which concedes that reference is not real; and a pioneering treatment in analytic philosophy on metaphor. To the revised edition (2001) is added a short reply to Quine.

Subjective, Intersubjective, Objective. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Includes “Knowing One’s Own Mind”, source of the Swampman argument.

Problems of Rationality. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Follows up on themes from Davidson’s first collection; includes an interview of Davidson by Ernie Lepore.

Truth, Language, and History. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Includes the highly cited “The Folly of Trying to Define Truth” plus six other articles on truth; six articles on language; two articles on anomalous monism; and minor articles in the history of philosophy.

Truth and Predication. Boston: Harvard University Press, 2005.

Part I is a revised version of Davidson’s 1989 Dewey Lectures, first published as “The Structure and Content of the Theory of Truth” in the Journal of Philosophy. Part II, on predication, is a version of Davidson’s 2001 Hermes Lectures.

The Essential Davidson. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Consists of six articles taken from Essays on Actions and Events, five articles taken from Inquiries into Truth and Interpretation, three articles taken from Davidson’s other collections, and “A Coherence Theory of Truth and Knowledge”, taken from the Journal of Philosophy.

b. Secondary Sources

Ludwig, Kirk, ed. Donald Davidson. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

Accessible contributions, each on one aspect of Davidson’s work: actions, events, truth and meaning, radical interpretation, literature, knowledge.

Lepore, Ernest, and Ludwig, Kirk. 2005. Donald Davidson: Meaning, Truth, Language, and Reality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

A sustained and authoritative treatment of how Davidson’s projects tie together, and their significance to philosophy.

Lepore, Ernest, and Ludwig, Kirk. 2009. Donald Davidson’s Truth-Theoretic Semantics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Foundations and applications of Davidsonian semantics, relevant for philosophers of language and linguists.

Hahn, Edwin Lewis. 1999. The Philosophy of Donald Davidson. The Library of Living Philosophers, volume XXVII. Peru, IL: Open Court Publishing Company.

Includes, as do all volumes in the Library of Living Philosophers, an intellectual autobiography and extensive bibliography.

Author Information

Vladimir Kalugin

Email: [email protected]

California State University, Northridge

U. S. A.