A Grammar of Hiuʦɑθ

Author: Jessie Sams

MS Date: 04-14-2012

FL Date: 05-01-2021

FL Number: FL-000074-00

Citation: Sams, Jessie. 2012. «A Grammar of Hiuʦɑθ» FL-

000074-00, Fiat Lingua,

Copyright: © 2012 Jessie Sams. This work is licensed

under a Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

Fiat Lingua is produced and maintained by the Language Creation Society (LCS). For more information

about the LCS, visit http://www.conlang.org/

A Grammar of

Hiuʦɑθ

Jessie Sams

How astonishing it is that language can almost mean,

and frightening that it does not quite….

from “The Forgotten Dialect of the Heart”

by Jack Gilbert

Table of Contents

Grammar

Chapter 1: Introduction to Hiuʦɑθ

Chapter 2: Sounds

Chapter 3: Orthography

Chapter 4: Nouns and Pronouns

Chapter 5: Verbs

Chapter 6: Adjectives and Adverbs

Chapter 7: Negation and Clauses

Chapter 8: Semantic Categories

Chapter 9: Discourse Structure

Appendices

Appendix I: Guide to IPA

Appendix II: Morpheme analysis of Hiuʦɑθ story

Appendix III: Grammar cheat sheets

Dictionaries

English-Hiuʦɑθ Dictionary

Hiuʦɑθ-English Dictionary

5

12

18

23

37

53

65

77

91

98

99

103

108

148

A GRAMMAR OF HIUTSAθ

5

Chapter 1

Introduction to Hiuʦɑθ

Hiuʦɑθ is an invented language that appears in a series of novels writ-

ten for young adults. The goal of this grammar is to investigate not only the

language itself but also the speakers of Hiuʦɑθ, integrating the language

with the speakers’ culture. As an invented language, there are only fictional

speakers of Hiuʦɑθ; however, throughout the grammar, the language will

be explored as if it and its speakers actually exist in order to bring the

readers into the fictional world of the language. Throughout the grammar,

when words in Hiuʦɑθ are written, they be written with a spelling based on

the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) for the readers’ convenience (a

guide to pronouncing IPA is in Appendix I).

This introductory chapter first focuses on the speakers of Hiuʦɑθ (Sec-

tion 1.1) before outlining key characteristics of the language and providing

the overall organization of the grammar (Section 1.2). The information on

the grammar is meant to provide readers with a broad understanding of

how Hiuʦɑθ is classified as a language in comparison with other world

languages; therefore, it will cover such features as lexicon and language

family, morphological type of language, and syntactic structure.

1.1 Speakers

Hiuʦɑθ is a language spoken by the Xiɸɑθeho (‘Gifteds’), a race of

women who, though they look human in appearance, have special abilities

(or Gifts). There are 12 families of Xiɸɑθeho, and each family has a desig-

nated xiɸɑθ (‘Gift’), such as the xiɸɑθ of Finding (the ability to find any-

thing, no matter how hidden) or of Making (the ability to make any object

from an existing, but different one). Each family has four generations at all

times, so the number of Xiɸɑθeho always remains 48. By most standards,

having only 48 speakers would classify Hiuʦɑθ as an endangered language;

however, the population has held steady at 48 speakers for well over a

millinium without the language losing its linguistic status, despite the fact

that the Xiɸɑθeho do not willingly allow their language to be shared with

human speakers (which makes collecting data for written grammars quite

difficult). In the unlikely event that the number of speakers should dwindle,

Hiuʦɑθ could quickly become a dead language.

JESSIE SAMS6

The Xiɸɑθeho—along with their language—first appeared in the sev-

enth century in Europe and parts of northern Africa, where they remained

until the 16th century. During those 900 years, they were a nomadic tribe

that traveled individually or, in some cases, in pairs or small groups. They

used their Gifts to help the humans they came in contact with as they jour-

neyed. All Xiɸɑθeho are able to speak and understand human languages

but use only Hiuʦɑθ to communicate with one another. Any fluctuations in

their language occurred during that time when they borrowed or calqued

terms from the continental languages to fill any lexical gaps; although, the

amount of borrowing and calquing remained rather limited even during that

period of fluctuation. The languages with the biggest effect on Hiuʦɑθ are

the ancient languages of Europe—primarily Latin and ancient Greek.

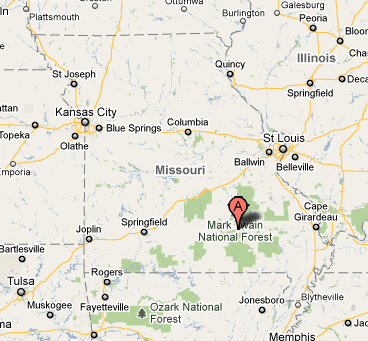

After near persecution in the 16th century when women were be-

ing burned for witchcraft and religious persecution was at its height, the

Xiɸɑθeho began questioning their purpose of helping humanity and banded

together to flee Europe for the isolation of the American “New World”

continent, where they once again became nomadic and mingled with the

indigenous people of the land for nearly 100 years. However, with the in-

flux of European settlers, they feared that another time of persecution was

near. After witnessing the Salem witch trials in the late 17th century, they

shunned humans and isolated themselves in a settlement they simply called

‘ekonilɑ’ (‘the colony’). They currently live—and have lived for over 300

years—in a rural (and otherwise uninhabited) area of the Ozarks in Mis-

souri. The approximate location of ekonilɑ is marked on the map below:

Figure 1. Location of ekonilɑ on Google map: 37.242765,-91.225233

Figure 1 shows the isolation of ekonilɑ—all roads end before the outer

boundaries. No human knows exactly how large ekonilɑ is, nor has any

A GRAMMAR OF HIUTSAθ

7

human been inside its boundaries. Based on information from a Xiɸɑθe

informant, though, ekonilɑ has at least 13 structures: 12 buildings house

the different families, and one building is their Assembly Hall (functioning

as both a temple and courthouse for the Xiɸɑθeho). Unpaved paths run be-

tween the buildings, and the outer area of ekonilɑ is wild forest land. While

the Xiɸaθeho can travel outside their confines, their borders are guarded

against intruders (other than animals, which can come and go freely).

The Xiɸɑθeho typically resist change, which is evident in their lan-

guage—a language with little to no irregularities, even in the morphology

of common nouns and verbs. Their resistance to change is also reflected in

borrowing: If a word or term is borrowed from another language, it often

takes years (or, in some cases, centuries) for the word to be entrenched

enough in Hiuʦɑθ to be considered a part of the language. If a lexical gap

exists, the Xiɸɑθeho are more likely to create an entirely new word in their

own language than they are to borrow one.

One change that occurred internally is a change in the name of their

language. When they isolated themselves in ekonila, they changed their

language name to Hiuʦeʦɑθeiθo (or ‘Hiuʦɑθ’), which literally means ‘su-

perior language.’ While the language itself is not linguistically superior to

any other language, its name portrays the attitude of the Xiɸɑθeho toward

other languages or, more specifically, toward speakers of other languages.

The Xiɸɑθeho view humans as inferior and, therefore, are often disdainful

when referring to humans or the things they hold important, and they resist

filling any lexical gaps caused by human invention over the past 300 years

(e.g., they have no specific word for car or computer).

1.2 Language

In its recognizable roots, Hiuʦɑθ is primarily Indo-European with cog-

nates for many common terms, such as those in the following table. In

Table 1 below, the Greek column is Ancient Greek, and the dashes repre-

sent entries that are either not available or are not cognates.

JESSIE SAMS

8

IE Root Sanskrit Greek

Latin

German Russian Hiuʦɑθ English

mater-

matar

mētēr

māter

Mutter

mat’

mɑθɑne mother

pəter-

pitar

patēr

swesor-

svasar

—

pater

soror

Vater

pápa

pɑθɑne

father

Schwester

sestrá

ʃuθɑno

sister

bhrāter-

bhratar —

frater

Bruder

brat

fɑθɑno

brother

nekʷ-t- —

ster-

mūs-

trei-

—

—

tri

nyx

aster

—

treis

nox

stella

mus

trēs

Nacht

noch

nuθne

night

Stern

Maus

drei

—

myš’

tri

ɑʦeli

muʃe

θele

star

mouse

three

Table 1. Indo-European cognates

A common pattern, which is seen in Table 1, is that when the IE root has

a [t], Hiuʦɑθ uses a [θ]; for example, the ‘mater-’ from IE is ‘mɑθɑne’ in

Hiuʦɑθ. Another common pattern is that the [s] in an IE root is an [ʃ] in

Hiuʦɑθ; an example is that the IE root ‘mūs-’ becomes the Hiuʦɑθ ‘muʃe’.

The exception listed in Table 1 to both of those generalizations is the IE

root ‘ster-’, which is ‘ɑʦeli’ in Hiuʦɑθ—a form of metathesis (reversing

the [s] and [t] sounds). Because Hiuʦɑθ does not have an [r] in its phone-

mic inventory, anytime an [r] carries through to Hiuʦɑθ, it is realized as an

[l]; an example is the IE root ‘trei-’ becoming the Hiuʦɑθ ‘θele’. Based on

cognates in the lexicon—like those in Table 1—Hiuʦɑθ is classified as an

Indo-European language. Beyond its lexicon, though, Hiuʦɑθ is an outlier

of Indo-European languages with features reminiscent of languages around

the world.

In inflecting words, Hiuʦɑθ is primarily an agglutinating language—it

has a variety of prefixes and suffixes that attach to a base with clear bound-

aries. For example, in (1) below, the word ‘itɑɑlihomɑ’ is broken down into

its individual morphemes:

(1) i-tɑɑli-ho-mɑ

def-animal-pl-acc

‘the animals’

The base for (1) is ‘tɑɑli’ (‘animal’); the prefix ‘i-’ is a definite marker that

attaches directly to the base. Furthermore, the plural suffix ‘-ho’ is distinct

A GRAMMAR OF HIUTSAθ

from the accusative suffix ‘-mɑ’. As an agglutinating language, the major-

ity of the prefixes and suffixes have a single meaning or grammatical func-

tion, like those in (1). While Hiuʦɑθ is primarily agglutinating, it has some

fusional characteristics, especially in the verbal inflections:

9

(2) ʦɑθe-keme

say-1p,incl,past

‘we said’

In the example in (2), the suffix ‘-keme’ indicates multiple grammatical

features: person, number, inclusiveness, and tense. In this case, the suf-

fix is first-person, plural, inclusive, and past tense. Unlike most fusional

languages, though, the suffix is still easily separable from its base, ‘ʦɑθe’

(‘say’). Hiuʦɑθ also shares some characteristics with analytic languages;

for instance, Hiuʦɑθ has prepositions:

(3) mexo e-konilɑ-hɑθ

around def-colony-loc

‘around the Colony’

Example (3) demonstrates that Hiuʦɑθ has function words (like preposi-

tions) that stand alone. Even with these features, though, Hiuʦɑθ is still

primarily an agglutinating language.

In general, the expected (i.e., ‘unmarked’) sentence structure is VSO,

which is not entirely uncommon in world languages but is less common

than SVO or SOV word orders. Examples of the typical word order are

below:

(4) a.

b.

ɑlikɑθito iuʦekɑ

V S

‘the bird is flying’

ʃinɑkɑ elelune menikoʃiɑmɑ

V S

‘the girl saw a cat’

O

If a sentence only has a subject and a verb, as in (4a), the verb will gener-

ally precede the subject. If a sentence has a subject, object, and verb, as

JESSIE SAMS

10

in (4b), the typical order is VSO. If a sentence has more constituents than

VSO, the typical sentence structure is the following:

(Neg) (Aux) V S O1 O2 ADJUNCT

An example of a sentence with more constituents is in (5):

(5) ŋɑi mifne ɲuekɑ emɑθɑne ɑsuneomɑ ehɑloneɸis ʦuʃo θexohɑθ

neg aux V S O1

O2 adjunct

‘No, the mother should not give her daughter the stone in front of

me’

The sentence in (5) demonstrates the typical order for sentences with ne-

gation, an auxiliary, two objects, and an adjunct. Because the language

inflects nouns, and to some extent adjectives, in the sentence to show their

grammatical roles (which will be further discussed in a later chapter), the

word order can vary from the typical one without resulting in any major

misunderstandings. Therefore, the sentence in (5) could be reworded like

the following:

(6) ʦuʃo θexohɑθ ɑsuneomɑ ŋɑi mifne ɲuekɑ emɑθɑne ehɑloneɸis

adjunct

‘No, the mother should not give her daughter the stone in front of

O1 neg aux V

O2

S

me’

Even with the consituents in a different order, the overall meaning of the

setnence does not change. However, with a different word order, the em-

phasis shifts—the sentence in (6) might be better translated into English as

‘In front of me, the stone the mother should not give to her daughter.’ The

wording sounds awkward in English, but it reflects the fact that in Hiuʦɑθ

any constituent placed at the beginning of the sentence (that would not

typically appear there) is brought into focus. Emphasis—focus or topical-

ization—is the primary reason sentences appear in a different word order.

However, a different word order could also reflect strong emotion.

1.3 Organization of the grammar

The following grammar of Hiuʦɑθ is organized into eight chapters,

each one exploring a different feature of the language and building on the

general information provided above.

A GRAMMAR OF HIUTSAθ

11

Chapter 2 focuses on the sounds of Hiuʦɑθ, examining both the pho-

nemes and the phonological processes present in the language. Chapter 3

builds on the sounds by providing the native writing system of Hiuʦɑθ, as

well as alternate spelling systems for writing Hiuʦɑθ words

Chapter 4 begins the investigation of the morpho-syntax of Hiuʦɑθ by

describing the noun and pronoun usage in the language. Chapter 5 builds

on the morpho-syntax by describing verb usage, and Chapter 6 provides

information on adjectives and adverbs. Chapter 7 finishes the section on

morhpo-syntax with descriptions of the use of negatives in utterances and

complex clauses, including subordinate clauses, questions, and reported

speech.

Chapter 8 focuses on the semantic categories within the Hiuʦɑθ lexi-

con, tying in key information about the Xiɸɑθe culture. Chapter 9, then,

builds on that by providing information about discourse and narrative struc-

ture in Hiuʦɑθ.

After the written grammar, two dictionaries are provided: an English-

Hiuʦɑθ Dictionary and a Hiuʦɑθ-English Dictionary.

JESSIE SAMS12

Chapter 2

Sounds of Hiuʦɑθ

In order to cover the full range of sounds in Hiuʦɑθ, this chapter has

three sections: phonemic inventories, syllabic concerns, and phonological

processes.

2.1 Phonemic inventories

Hiuʦɑθ was originally called the “whispered language” (Huɸelihʦɑθeiθo,

or Huɸeʦɑθ for short) because it was only spoken in wisps in passing when

the Xiɸɑθeho crossed paths while living among humans; the language was

spoken primarily in whispers to keep humans from deciphering the lan-

guage through any sort of frequent exposure. Because it was primarily

whispered, there are no voiced/voiceless distinctions (as they are all lost

when whispered) in any of the sounds. In other words, while there are

voiced phonemes (e.g., [m] or [e]), there are no voiceless counterparts to

those phonemes.

The consonants in the phonemic inventory are largely voiceless to pro-

vide maximal distinctions between consonants and vowels when the lan-

guage is spoken aloud; furthermore, there are more fricatives than any

other type of consonant, which gives the language a whispered (or hissing)

feel. Table 2 below provides the phonemic inventory of Hiuʦɑθ consonants

(Table 2 is an IPA chart; refer to Appendix I for further tips on pronounc-

ing IPA):

Bilabial Labio-

dental

Dental Alveolar Post-

Palatal Velar Glottal

alveolar

ɲ

ʃ

k

ŋ

x

h

p

m

ɸ

Plosive

Nasal

Fricative

Affricate

Lat. app.

f

θ

t

n

s

ʦ

l

Table 2. Phonemic consonants of Hiuʦɑθ

A GRAMMAR OF HIUTSAθ

13

Many of the consonants in Table 2 are familiar to English speakers; how-

ever, some of the consonants are unfamiliar or pronounced differently than

those in English:

(a) All three voiceless plosives (or stops) are unaspirated (e.g., [p] is

pronounced as the initial [p] in Spanish perro).

(b) The palatal nasal [ɲ] is pronounced like the medial sounds in Span-

ish piña, and the velar nasal [ŋ] is pronounced like the final sound in

English sing.

(c) The two fricatives not found in English are the voiceless bilabial fric-

ative [ɸ] and the voiceless velar fricative [x]; the [x] is pronounced

like the final sound of German ach.

(d) The voiceless glottal fricative [h] is fully pronounced as a glottal

fricative, not as a voiceless vowel counterpart as it is in English, and

when [h] appears at the end of a syllable, it is still fully pronounced.

(e) The voiceless alveolar affricate [ʦ] is not found in English but is

easily produceable by most English speakers (as it is like the end of

common words like cats [kæts]); it helps make Hiuʦɑθ feel exotic

that the [ʦ] appears in the onset of syllables, something that would

not naturally occur in English.

The IPA symbols for the consonants (found in Table 2) are used throughout

this grammar to spell out Hiuʦɑθ words.

Hiuʦɑθ is a typical language in that it has the three voiceless stops [p],

[t], and [k] that are found most frequently in languages, and it has the most

sounds produced in the alveolar region than any other, which is a typical

pattern for languages. Furthermore, the most frequent three nasals are all

present ([n], [m], and [ŋ]) along with the less frequent [ɲ]. The language is

a bit atypical in that it has the dental fricative [θ], which is not a common

world sound, and it has no voicing distinctions. According to Maddieson,

Hiuʦɑθ has a moderately small consonant inventory with 16 consonants,

where the typical inventory is 19-25. Having a moderately small consonant

inventory is one way that Hiuʦɑθ differs from other Indo-European lan-

guages, as the highest concentrations of languages with moderately small

consonant inventories are “in the Pacific region (including New Guinea),

in South America and in the eastern part of North America” (Maddieson,

Chapter 1).

Table 3 provides the vowels in the phonemic inventory of Hiuʦɑθ:

JESSIE SAMS14

Front

Back

Close

Close-mid

i

e

u

o

Open

ɑ

Table 3. Phonemic vowels of Hiuʦɑθ

The vowels in Table 3 are the classic five vowels that often show up in

natural languages (and invented languages). While most English speakers

will produce the close-mid tense vowels [e] and [o] as diphthongs, they

are monophthongs in Hiuʦɑθ. The vowels are balanced and are typical for

world languages: According to the Maddieson, the average vowel inven-

tory is 5-6 vowels, and languages with average-sized vowel inventories

appear throughout the world (Chapter 2).

The phonemic inventory, when considered together, falls into the aver-

age size for phonemic inventories (20-37 phonemes) with 21 phonemes. Its

consonant-vowel ratio (3.2) is average when compared across world lan-

guages (Maddieson states that the average ratio is between 2.75 and 4.5);

several other Indo-European languages share this average ratio, including

Spanish, Modern Greek, and Romanian (Maddieson, Chapter 3).

2.2 Syllabic concerns

The syllable structure of Hiuʦɑθ is theoretically (C)V(C); however, due

to phonological constraints, it is really a CV(C) language because any vow-

el without a C onset is automatically preceded by a glottal stop. While the

onset can be any consonantal sound, the coda can only be a fricative, and

the nucleus can only be a vowel (i.e., Hiuʦɑθ has no syllabic consonants).

There are no consonant clusters in the language, so when a syllable is CVC,

the coda is always produced as its own sound (i.e., the coda C never blends

with the onset C of the next syllable). Thus, /mostɑ/ is pronounced [mɔs-tɑ]

and not [mɔ-stɑ], as many English speakers would typically do, or [mɔst-ɑ].

(The hyphen in the pronunciation is only used to show where the syllable

boundary occurs for ease of reference.) Furthermore, when the coda C is

the same as the onset C of the following syllable, the two consonants are

still fully produced; therefore, /mosse/ is pronounced [mɔs-se] (with an

elongated, or geminated, consonant) and not [mɔse].

A GRAMMAR OF HIUTSAθ15

Accent in Hiuʦɑθ is realized with a pitch accent on the initial syllable:

If the word is polysyllabic, the pitch is a rising one; if the word is monosyl-

labic, the pitch is a falling one. For instance, the word [hɑlɑθɑ] has a rising

pitch on the first syllable [hɑ] while the word [se] has a falling pitch on

its only syllable. All other syllables are produced with a neutral pitch. The

pitch accent remains on the initial syllable of the root word so that even if

a prefix is added, the accent remains on the same syllable; thus, when the

verb [hɑlɑθɑ] (‘need’) becomes part of an interrogative construction and re-

ceives the prefix [ʦi-] to become [ʦihɑlɑθɑ], the rising pitch accent remains

on the [hɑ]. For words that have four or more syllables, a secondary pitch

accent with a rising pitch that is not quite as high as the primary accent is

placed on the fourth syllable (so that no more than two unaccented syllables

occur in a row); proper compounds in Hiuʦɑθ ignore word boundaries and

place the secondary pitch accent on the syllable it typically falls on, regard-

less of where the second word begins. For example, [ʔifepɑʔiθo] ‘belief’

receives the following pitch accents: [ʔí fe pɑ ʔi ̋ θo], where the initial syl-

lable [ʔi] receives the primary accent ( ́) and the fourth syllable [ʔi] receives

the secondary accent ( ̋). The compound [ʔifepɑʔiθoloɸɔs] ‘religion’ (liter-

ally ‘belief system’) receives the accents on those same syllables with the

addition of a falling accent on the final syllable: [ʔí fe pɑ ʔi ̋ θo lo ɸɔ̀s].

Having the initial syllable receive the stress is common to Indo-European

languages: Goedemans and van der Hulst state that many European systems

have initial stress (Chapter 14).

2.3 Phonological processes

As previously stated, the theoretical V syllable structure in Hiuʦɑθ is

never pronounced as such because of an obligatory glottal stop insertion.

glottal stop insertion: When a vowel occurs without a consonant onset

in its syllable, a glottal stop is inserted as the onset.

For instance, consider the following examples:

(7) a. fɑhɑle → [fɑhɑle]

b. ɑŋelɑ → [ʔɑŋelɑ]

c. eolɑ → [ʔeʔolɑ]

‘different’

‘to cook’

‘empty’

In all three examples, any vowel with a specified syllable onset is produced

as is; however, in examples (7b) and (7c), a glottal stop is inserted in front

JESSIE SAMS

16

of the vowels that have no specified onset, which is why the initial [ɑ] of

‘ɑŋelɑ’ is pronounced [ʔɑ] in example (7b) and why the [eo] of example

(7c) is pronounced [ʔeʔo]. Thus, any V syllable automatically becomes a

CV syllable.

Another phonological process deals with vowels in closed syllables

(those with a coda); the vowels in closed syllables become lax.

vowel laxation: Any vowel in a closed syllable becomes a lax vowel.

The following five examples demonstrate the obligatory vowel laxation in

each of the vowels:

(8) a. hemiθ → [hemɪθ]

b. leθlo → [lɛθlo]

c. uʃte → [ʔʊʃte]

d. meoʃ → [meʔɔʃ]

e. ʦɑθmɑ → [ʦɑθmɑ]

‘blood’

‘baby’

‘rotten’

‘to sit’

‘word’

Examples in (8) show the four tense vowels becoming lax when the syl-

lable structure is CVC: the close front tense vowel [i] becomes the lax [ɪ]

in example (8a), the close-mid back tense vowel [o] becomes the lax [ɔ] in

example (8b), and so on. Because the open back vowel [ɑ] is already lax, it

undergoes no outward change, which can be seen in example (8e).

Another phonological process in Hiuʦɑθ is a type of assimilation called

palatalization, which is an optional process:

[x] palatalization: When the voiceless velar fricative [x] is followed

by the close front vowel [i], the [x] is optionally palatalized to become

the voiceless palatal fricative [ç].

The following two examples demonstrate [x] palatalization:

(9) a. ɲixes → [ɲixɛs]

b. xilɑ → [xilɑ]/[çilɑ]

‘breakfast’

‘to laugh’

In (9a), the [x] is produced as a velar fricative because the [i] does not fol-

low it; however, in (9b), the verb ‘to laugh’ can be pronounced either with

the [x] or with the [ç].

A GRAMMAR OF HIUTSAθ

17

If a suffix is added onto a morpheme that exactly reduplicates the last

syllable of the root, the final syllable of the root undergoes a vowel change.

dissimilation: When a suffix causes a reduplicated syllable, the vowel

of the first syllable shifts.

For any vowel besides [ɑ], the shift is to [ɑ]; if the vowel is [ɑ], it shifts to

[e]. For example:

(10)

(11)

a. ʦɑθe

b. -θe

c. ʦɑθɑθe

a. iʦimɑ

b. -mɑ

c. iʦimemɑ ‘idea-acc’

‘speak’

‘one who…’

‘speaker’

‘idea’

acc

‘Speaker’ should be ‘ʦɑθeθe’; however, due to the dissimilation rule, it be-

comes ‘ʦɑθɑθe’, as seen in (10). Also, the accusative form of ‘idea’ should

be ‘iʦimɑmɑ’; example (11) demonstrates, though, that it is ‘iʦimemɑ’.

When considering these phonological processes, the following phones

would need to be added to the preceding phonemic inventories to create

phonetic inventories: the voiceless glottal stop [ʔ], voiceless palatal frica-

tive [ç], and lax vowels [ɪ], [ɛ], [ʊ], and [ɔ]. So while Hiuʦɑθ has 21 pho-

nemes, it has 27 phones. The only phonological process that changes the

spelling of the word is the dissimilation of final syllables (e.g., ‘speaker’ is

spelled ‘ʦɑθɑθe’, not *‘ʦɑθeθe’); all other types of phonological processes

are not reflected in the spelling of the word. As such, the IPA representa-

tions do not reflect those process either. Therefore, even though ‘blood’ has

the spelling ‘hemiθ’, it is pronounced [hemɪθ]. This spelling convention

follows the orthography (as outlined in chapter 3) and is the reason Chapter

1 states that the spelling throughout this grammar is “based on IPA” and

not an actual IPA representation. The spelling convention could also be

described as a phonemic one (as opposed to a phonetic one).

JESSIE SAMS

18

Chapter 3

Orthography

The Xiɸɑθeho do not generally write their language—written language

provides lasting records of the language that could be intercepted by hu-

mans, and, as stated in Chapter 2, the Xiɸɑθeho guard their language from

humans. However, they still have a writing sytem for their language be-

cause they are able to read each other’s thoughts (as written ribbons of

thought that they see appear above the thinker’s head). As such, the writing

system is meant to quite literally represent ribbons—the letters look like

what scraps of ribbons might do if they fell onto the floor. While it is par-

tially (and very loosely) based on the Greek alphabet, the system is actually

an abjad (or a ‘consonant alphabet’) and is written horizontally from left

to right (like English). Figure 1 below presents the Hiuʦɑθ abjad, with the

names of the letters (which are heavily influenced by Ancient Greek), in the

order used to organize Hiuʦɑθ dictionaries:

A

a

E

e

f h

I

i

k l

[ɑ]

[ʔɑ]

ɑlef

[ʔe]

etɑ

[e]

[f]

fe

[h]

hɑ

[ʔi]

iotɑ

[i]

[k]

kɑpɑ

[l]

lɑmɑ

m

n

j

g

O

o

p

b

s c

[m]

mu

[n]

nu

[ɲ]

eɲɑ

[ŋ]

eŋɑ

[o]

[ʔo]

omekɑ

[p]

pe

[ɸ]

ɸi

[s]

[ʃ]

simɑ eʃɑ

t

z U

u

x d

[t]

tɑ

[ʦ]

oʦe

[ʔu]

uselo

[u]

[x]

xi

[θ]

θetɑ

Figure 2. Abjad of Hiuʦɑθ

While the order presented in Figure 2 represents the organization of Hiuʦɑθ

dictionaries, the Xiɸɑθeho do not have a set order for their abjad. Because

the Xiɸɑθeho naturally pick up the ability to produce and comprehend the

ribbons of thought much like they do spoken language, they do not have

to learn an alphabet or recite letters. The names of the letters are used to

A GRAMMAR OF HIUTSAθ

19

refer to the letters themselves but are not often used in education or even

conversation.

As seen in Figure 2, the vowels have two different orthographical rep-

resentations: The first, their “true” form, is only used when the syllable has

no onset (i.e., when the glottal stop is inserted); the second, their “reduced”

form or diacritic form, is only used when the syllable is CV. For example,

the following are words in Hiuʦɑθ:

(12)

‘head’

‘to help’

a. kɑθɑ kada

b. ɑθu Adu

c. meoʃ meOc ‘to sit’

d. lɑiθe laIde

‘wide’

e. eliɑ EliA ‘space’

The examples in (12) demonstrate the differences in vowel representation.

Because all “true” forms of the vowels are pronounced with a glottal stop

in front of the vowel sound (e.g., A [ʔɑ] but a [ɑ]), the glyphs representing

those “true” vowels are actually syllabic representations. The “reduced”

or diacritic forms are called ‘tiɑkɑleθo’ forms in Hiuʦɑθ. To refer to a

particular tiɑkɑleθo, the letter represented by the diacritic is compounded

with ‘tiɑkɑleθo’; for instance, < a > is called ‘ɑleftiɑkɑleθo’, and < u > is

called ‘uselotiɑkɑleθo’. Examples (12b-e) demonstrate that though the glot-

tal stop is pronounced, it does not appear in the Hiuʦɑθ written form; due

to its absence in Hiuʦɑθ, spelling conventions based on IPA also omit the

glottal stop (i.e., ‘wide’ is written as ‘lɑiθe’, not ‘lɑʔiθe’). Because there are

no diphthongs in Hiuʦɑθ, the omission of the glottal stop in written form

rarely causes ambiguities. An example where it does cause an ambiguity

is in (13):

(13) meoʃiθo

‘sitting’ (n.)

The syllables of (13) are as follows: [me-ʔɔʃ-ʔi-θo]. The spelling in (13),

though, could lead to the following misparsing: [me-ʔo-ʃi-θo]. Speakers

familiar with the language would not have this problem, as the ‘-iθo’ suf-

fix is a common suffix that turns a verb into a noun. Because morpheme

boundaries are represented in the majority of the examples provided in this

grammar, even beginning speakers will be able to differentiate the syllable

breaks; the example in (13) can be represented as ‘meoʃ-iθo’, which indi-

cates that the [i] from ‘-iθo’ begins a new syllable and, thus, is pronounced

JESSIE SAMS

20

with a glottal stop preceding it.

The glyphs of written Hiuʦɑθ can be organized to show that sounds

with similar manners have similar features; thus, the abjad could be broken

down into manners of production, as in Table 4 below.

Manner

stop

nasal

Representation

p t k

m n j g

Feature

straight line with attached curved line

line that changes vertical direction

fricative/affricate

b f d s c x h z

curved line with a single small loop

liquid

vowel

l

A E I O U

a large loop

curved line with a “near” loop

Table 4. Glyphs by manner

The first column in Table 4 breaks the sounds of Hiuʦɑθ into five man-

ners; the single affricate [ʦ] is considered a part of the fricatives for this

table. The second column provides the written glyphs that correspond to the

manners listed in the first column, and then the third column provides the

feature the glyphs share. If new sounds were introduced to the language,

they would most likely follow these feature guidelines. For instance, if the

language were to create letters to correspond to the lax vowels, they would

most likely be curved lines with near loops.

The only phonetic consonant that has its own written representation is

the voiceless glottal stop [ʔ], which is represented by ‘utɑ’ < q >. The utɑ

does not appear in any orthographic representations of Hiuʦɑθ, so it does

not appear even when a word has a glottal stop (as indicated by examples

such as those shown above). The written representation of utɑ exists solely

as a way to speak about the sound that occurs so frequently in the Hiuʦɑθ

language yet does not appear in written form.

In written Hiuʦɑθ, the boundaries between words are indicated by

spaces. The end of a sentence is marked by an ‘ɑpole’ < . >, which

should not be confused with a period—the ɑpole is used to show the end of

any sentence, whether it is a statement, question, or exclamation. There is

also an ‘imute’ < : >, which indicates mid-punctuation of a sentence and

is generally represented in English as either a comma or colon. No strict

punctuation “rules” exist for Hiuʦɑθ, and so these two punctuation marks

can be liberally applied and used in a variety of situations. The best transla-

A GRAMMAR OF HIUTSAθ

21

tions for the ɑpole and imute are ‘final punctuation’ and ‘middle punctua-

tion’, respectively: the ɑpole indicates the current sentence is finished while

an imute indicates that the sentence will continue.

The written numbers in Hiuʦɑθ are borrowed from the Arabic numer-

als. Originally, Hiuʦɑθ had no written form for numerals, and so any writ-

ten representation was either a system of slashes (much like keeping score,

where the fifth slash crosses through the first four slashes) or a written

form of the name of the number. Neither forms are efficient for dealing

with larger numbers, though, and the Xiɸɑθeho adopted the Arabic numeral

system well over a millineum ago. The numbers are presented in Figure 3

below:

0

1

2

3

4

neɑɸθe mone

ʃolu

θele

5

ɸiɸlu

6

7

8

sixɑ

ɑhne

Figure 3. Numbers in Hiuʦɑθ

sife

ɸɑle

9

neni

Because of their strong similarity to other Arabic numeral systems (such

as the one used in English), these numbers are recognizable by speakers of

many languages.

All words but one in the Hiuʦɑθ language are written according to their

sounds (i.e., written using the writing system presented above). The excep-

tion is the word ‘ximɑlɑ’, which most closely translates as ‘the mark of the

Xiɸɑθe’. When ximɑlɑ is represented in writing, it looks like the symbol in

(14a) and is never written out, as in (14b):

(14)

b.

a. y

*ximala

The asterisk next to the form in (14b) indicates that the written form is

never used for the word ‘ximɑlɑ’.

While this grammar uses a spelling system based on IPA that most

closely matches the Hiuʦɑθ writing system, Hiuʦɑθ also has a Roman-

ized form of spelling, used in works for people unfamiliar with IPA. The

Romanization differs from the IPA representation slightly; Table 5 below

provides the Hiuʦɑθ, IPA, and Romanized equivalents for those sounds

represented differently in the IPA and Romanized conventions:

JESSIE SAMS

22

Hiuʦɑθ

A

a

j

g

b

c

z

x

d

IPA

Romanization

ɑ

ɑ

ɲ

ŋ

ɸ

ʃ

ʦ

x

θ

a

a

ñ

ng

ph

sh

ts

ch or x

th

Table 5. Romanization versus IPA

The sounds not present in Table 5 are represented the same in IPA and

Romanized conventions. For example, hiUzad in IPA conventions is repre-

sented as ‘Hiuʦɑθ’ but is represented as ‘Hiutsath’ in Romanized conven-

tions. The primary difference is that the Romanized conventions represent

some of the single sounds as a combination of two letters. The majority of

those two-letter combinations do not cause any misunderstandings; the only

exception is the ‘sh’ representation of the [ʃ] sound. For example, the word

‘lɑʃɑ’ (‘do’) is represented as ‘lasha’ in Romanized conventions. However,

in Hiuʦɑθ, ‘lasha’ could indicate [lɑʃɑ] (‘do’) or [lɑshɑ] (‘lick’).

Of the three methods used to represent Hiuʦɑθ in written form, the

Hiuʦɑθ abjad is the most reliable, as it most directly reflects the pronuncia-

tion. If the Hiuʦɑθ abjad is not used, the IPA conventions for spelling are

the second best at reflecting the actual pronunciation. However, if a speaker

is unfamiliar with both conventions, the Romanized form is a good indica-

tor of how the majority of the words will be pronounced.

A GRAMMAR OF HIUTSAθ23

Chapter 4

Nouns and Pronouns

Hiuʦɑθ nouns can be modified with both inflectional and derivational

affixes. Nouns inflect for number, case, and determinacy, which are dis-

cussed in the first three subsections. Nominal derivations are discussed in

the fourth subsection, and pronouns, which also inflect for case, are dis-

cussed in the final subsection.

4.1 Number

Nouns in Hiuʦɑθ have two possible numbers: singular and plural. Sin-

gular is the unmarked form (i.e., a bare noun indicates it is singular) while

plurality is marked with the suffix ‘-(h)o’.

(15)

a. leθlo

b. leθloho

‘baby’

‘babies’

The plural suffix is generally fully pronounced as ‘-ho’, as in (15); how-

ever, the [h] can be optionally deleted in the plural suffix. That occurs

most often when the noun ends in a consonant; when the ‘-o’ is added, the

syllable breaks change (this is the only instance when the syllables blend).

(16)

a. sɑox

b. sɑoxho

c. sɑoxo

‘leg’

‘legs’

‘legs’

In example (16a), the noun ‘sɑox’ ends in a fricative; the plural ‘-ho’ can

be fully pronounced, as in (16b), or it can delete the [h], as in (16c). When

the [h] is deleted, the syllables shift so that the final fricative is a part of

the plural affix:

(17)

sɑ-o-xo

This syllable break that is demonstrated in (17) only occurs with the ‘-o’

plural. When the fricative is taken from the previous syllable, the vowel

goes back to its tense pronunciation (i.e., the laxing process is undone

JESSIE SAMS

24

because the syllable is now an open one). Therefore, (17) is pronounced

[sɑoxo] and not [sɑɔxo].

4.2 Case

Hiuʦɑθ is an active-stative language and has nine cases, all of which

are provided in Table 6 below. Widely used terms for case will be used to

describe the case system, along with full descriptions of how those cases

are applied in the language.

nominative (NOM) —

accusative (ACC)

genitive (GEN)

dative (DAT)

locative (LOC)

-mɑ

-su

-ɸis

-hɑθ

comitative (COM)

-xɑ

instrumental (INST)

-xɑɸ

ablative (ABL)

vocative (VOC)

-lof

-i

Table 6. Nominal cases

As can be seen in Table 6, the unmarked case is the nominative; if a bare

noun occurs, it is not only singular but also in the nominative case. All

other cases are marked with agglutinating suffixes, with the case marking

occurring after plurality:

(18)

a. loteʃi-lof

road-abl

b. loteʃi-ho-lof

road-pl-abl

Example (18) demonstrates the order of bound morphemes: NOUN-plural-

ity-case.

As an active-stative language, the subject of a transitive verb is in the

nominative case, and the subject of an intransitive verb is either nominative

A GRAMMAR OF HIUTSAθ

or accusative, depending on the verb. The nominative case is perhaps bet-

ter termed the “agentive” and “copulative” case, as it marks subjects that

either think/do something or are being described as something, as in the

following examples:

25

(19)

a. felɑ-to

e-leθelune

ɑ-meŋo-mɑ

hit-3s,pres def-child,nom def-chair-acc

‘The child is hitting the chair’

b. lusi-to

e-leθelune

dance-3s,pres def-child,nom

‘The child is dancing’

c. mɑθo-to

e-leθelune

iɸune-teɸ

be-3s,pres def-child,nom good-pred

‘The child is good’

In the examples in (19), ‘eleθelune’ (‘the child’) is the subject of the verb;

all instances are marked as the nominative case.

The accusative case is used to mark objects of transitive verbs, subjects

of some intransitive verbs, and grammatical subjects of passive verbs; it

could perhaps be better termed the “patientive” case because it typically

marks entities that are undergoing some change, as in the examples below:

(20)

a. felɑ-to

e-leθelune-mɑ

hit-3s,pres def-child-acc

‘She is hitting the child’

b. oɲeθ-to

e-leθelune-mɑ

fall-3s,pres def-child-acc

‘The child is falling’

c. pe-felɑ-to

e-leθelune-mɑ

pass-hit-3s,pres def-child-acc

‘The child is being hit’

In example (20a), ‘eleθelune’ is the object of the transitive verb ‘felɑ’ and

so carries the accusative suffix, ‘-mɑ’. In (20b), ‘eleθelune’ is the subject

of an intransitive verb; however, the subject is not an agentive subject (the

falling is happening to the child rather than the child doing the falling out

of volition). Then, in (20c), it is the grammatical subject of a passive verb.

Furthermore, the accusative case is used with objects of prepositions

that mark movement; generally, that movement is toward something, but

JESSIE SAMS

26

other times, it simply denotes movement regardless of the goal.

(21)

a. filoθ oɲele-mɑ

to

river-acc

‘to/toward a river’

b. xiuθ oɲele-mɑ

along river-acc

‘(move) along the side of a river’

The example in (21a) provides the most prototypical usage of an accusa-

tive object with a preposition: movement toward a goal. While ‘filoθ’ can

have other meanings (e.g., ‘into’), it means ‘to/toward’ when used with an

accusative object. As (21b) demonstrates, though, the movement does not

necessarily have to be toward its goal; ‘xiuθ’ can mean ‘beside’ but with an

accusative object means ‘(to move) along the side of’.

The genitive case is primarily used to mark possession; the suffix is at-

tached to the noun indicating the possessor, as in (22):

(22)

e-tinofiθe-su

ekɑfelɑ

strength,nom def-teacher-gen

‘strength of the teacher’ / ‘the teacher’s strength’

When used alone, the genitive can be translated as ‘of NOUN’, as in (22).

Also, some verbs require their objects to be in the genitive case. The typi-

cal word order shifts when the object is genitive so that the object appears

directly after the verb.

(23)

a. ɑxisɑnɑhe-to θexo-su

awe-3s,pres 1s-gen

‘The teacher’s strength awes me’

ekɑfelɑ

strength,nom def-teacher-gen

e-tinofiθe-su

b. ɑxisɑnɑhe-to θexo-su

awe-3s,pres 1s-gen

‘She awes me’

In both examples in (23), the one being awed, ‘θexo’ (‘I’), is in the genitive

case; the genitive object, then, occurs directly after the verb instead of the

subject, as would typically be expected.

The dative case is used to mark the “recipient” (or intended recipient)

of ditransitive verbs—it marks the second object in dual object sentences;

A GRAMMAR OF HIUTSAθ

27

it could also be translated with ‘due to’ or ‘on account of’ when it is not the

second object of a verb. Some (albeit very few) prepositions can take dative

objects.

(24)

a. ɲue-to

menɑ-etɑɸe-mɑ e-leθelune-ɸis

give-3s,pres indef-stick-acc def-child-dat

‘She is giving a stick to the child’

b. ulefɑte-to

ɑ-seɲeiθo-mɑ

e-leθelune-ɸis

listen-3s,pres def-song-acc def-child-dat

‘She is listening to the song on account of the child’ (i.e., for

the benefit of the child)

c. mexo e-leθelune-ɸis

about def-child-dat

‘concerning/about the child’

The recipient of the verb ‘ɲue’ (‘give’) in (24a) takes a dative recipient (or

second object); in this case, the child is receiving the stick and so has the

dative suffix. In (24b), though, there is no direct recipient; instead, the child

could be understood as a metaphorical recipient: the child is receiving sat-

isfaction or pleasure from the subject listening to the song. Example (24c)

demonstrates that some prepositions can take dative objects; ‘mexo’ can

be translated several ways, depending on the case of its object. In (24c), it

is translated as ‘about’ or ‘concerning’ because the object is in the dative

case.

Some verbs require dative objects, such as ‘lusiɑ’ (‘to please’):

(25)

a. lusiɑ-to

e-tinofiθe

e-hɑlosne-ɸis

please-3s,pres def-teacher,nom def-student-dat

‘The student likes the teacher’ (lit. ‘The teacher pleases the

student’)

b. xilɑ-to

e-hɑlosne-ɸis

laugh-3s,pres def-student-dat

‘She is laughing at the student’

In all cases where the verb requires a dative object, there is an implied

reading that the object is receiving something, whether it be concrete or

abstract; for instance, the student is “receiving” pleasure in (25a), and the

student is “receiving” laughter in (25b).

JESSIE SAMS

28

The locative is used for nouns marking the location and can often be

translated as ‘in/at NOUN’:

(26)

ɑ-hɑʃose-hɑθ

nɑɸθe-to

swim-3s,pres def-water-loc

‘She is swimming in the water’

The locative suffix on ‘hɑʃose’ indicates that the swimming takes place in

the water; no preposition is needed to show that relationship between the

verb and noun. The locative can also be used to mark the objects of some

prepositions, denoting the goal for movement:

(27) filoθ ɑ-hɑʃose-hɑθ

into def-water-loc

‘into the water’

While ‘filoθ’ was translated as ‘to/toward’ in (21a) with an accusative ob-

ject, it is translated as ‘into’ with a locative object, as in (27); the locative

indicates that the movement resulted in an ending location (in this case, the

water) while the accusative simply indicates movement toward a goal.

The comitative case denotes accompaniment and is best translated as

‘with NOUN’:

(28)

peʃne-to

e-tinofiθe-xɑ

walk-3s,pres def-teacher-com

‘She is walking with the teacher’

The comitative in (28) is distinct from the instrumental case, which can also

be translated as ‘with NOUN’:

(29)

ɑxikileʃnɑ-to ɑ-esɑ-mɑ

hɑʃose-xɑɸ

wash-3s,pres def-wall-acc water-inst

‘She is washing the wall with water’

If the comitative is used, it is understood that the noun in question was

“along for the ride” while the instrumental indicates that the noun in ques-

tion is being used to achieve some goal:

A GRAMMAR OF HIUTSAθ

(30)

a. felɑ-to

ɑ-esɑ-mɑ

e-leθelune-xɑ

hit-3s,pres def-wall-acc def-child-com

‘She is hitting the wall with the child’ (they are hitting the

29

wall together)

b. felɑ-to

ɑ-esɑ-mɑ

e-leθelune-xɑɸ

hit-3s,pres def-wall-acc def-child-inst

‘She is hitting the wall with the child’ (she is using the child

to hit the wall)

As the examples in (30) demonstrate, using one case versus another results

in a different meaning even though both can be translated as ‘with NOUN’

in English.

The ablative case most generally marks the source. When the ablative

case is used without a preposition, it can be translated as ‘from’ or ‘by

means of’ or ‘caused by’; when it is used with a preposition, it indicates

movement away from some source.

(31)

a. peʃne-to

walk-3s,pres def-river-abl

ɑ-oɲele-lof

b. oɲeθ-to

‘She is walking from the river’

selɑ meŋo-lof

chair-abl

fall-3s,pres off

‘She is falling off (of) a chair’

In both examples in (31), the ablative most generally marks the noun indi-

cating the origin of the action; in (31a), the walking began in or at the river,

and, in (31b), the falling started on a chair. Sensory verbs can take ablative

or accusative objects, depending on the intended meaning:

(32)

a. ŋeo-to

ɑ-ɸiθe-ho-mɑ

smell-3s,pres def-flower-pl-acc

‘She smells the flowers’ (she is purposefully smelling the

flowers)

b. ŋeo-to

ɑ-ɸiθe-ho-lof

smell-3s,pres def-flower-pl-abl

‘She smells the flowers’ (the smell of flowers is in the air,

and she happens to smell them)

The difference in interpretation of sensory verbs is that with an accusative

JESSIE SAMS

30

object, as in (32a), the verb indicates that the subject has volition while

with an ablative object, as in (32b), the verb indicates that the sensory in-

formation is involuntarily being processed.

The vocative “case” is used to indicate the addressee(s) of an utterance.

(33)

θɑlihɑ-i

neʃi-to

Thaliha-voc go-3s,pres

‘Thaliha, she is going’

In (33), Thaliha is the addressee, not the subject of the verb. The speaker

is letting Thaliha know that someone else is going. The vocative is most

typically used with a proper name and often occurs at the beginning of the

utterance.

4.3 Determinacy

Nouns in Hiuʦɑθ are also inflected for determinacy; the determiner

used depends on two features: definite/indefinite and animacy of the noun.

Inanimate nouns are objects with no ability to move or think on their own

(e.g., stone, water). Animate nouns are then divided into two categories:

those with volition and those without. Animate nouns with volition are

humans (and Xiɸɑθeho) while animate nouns without volition are animals

and plants. Placing plants into an animate category reflects the Xiɸɑθeho

belief that plants are living beings but, like animals, have no volition.

DEF (vol.)

DEF (no vol.)

DEF (inani.)

e-

i-

ɑ-

IND (vol.)

(mone-)

IND (no vol.)

(meni-)

IND (inani.)

(menɑ-)

Table 7. Determiners

Table 7 provides the six determiners in Hiuʦɑθ; the indefinite determiners

are in parentheses because they are optional. While definite determiners

are required (unless the noun in question is a proper name), indefinite de-

terminers are not required. The definite determiners are most closely trans-

A GRAMMAR OF HIUTSAθ

31

lated as ‘the’, and the indefinite determiners are most closely translated as

either ‘a/an’ or ‘any’.

(34)

a. ɑ-hɑʃose

def-water

‘the water’

b. menɑ-hɑʃose or hɑʃose

indef-water water,indef

‘any/some water’ (there is some undefined body of water)

As the examples in (34) demonstrate, Hiuʦɑθ determiners are prefixes, at-

taching directly to the noun.

Taking determinacy into consideration with the above information, the

overall structure for inflections on nouns is the following:

Det.NOUN.Pl.Case

Those three features are the inflectional possibilities for nouns; the next

subsection covers some possible derivations.

4.4 Derivations on nouns

The nominal derivations in Hiuʦɑθ are prefixes, and the most common

derivational prefixes are listed in Table 8.

PROPER

(heθ-)

DIM

pejorative

NEG

le-

ɑɸ-

ɲe-

adjectivalize

eθɑ-

Table 8. Nominal derivations

All derivational prefixes follow the determiner prefixes but precede the

noun (i.e., Det-Derivation-NOUN). When prefixes are used, the pitch ac-

cent remains on the first syllable of the base word (in this case, the noun).

The first prefix in Table 8 is an optional one that can replace the determiner

for proper names:

JESSIE SAMS

32

(35)

a. elenɑ

Elena

b. heθ-elenɑ

prop-Elena

Using the ‘heθ-’ prefix is like saying ‘the NAME’; it is most useful when

the name, like ‘elenɑ’ in (35) is also a common noun or verb. In Hiuʦɑθ,

‘elenɑ’ is the word meaning ‘to lead’. When it is used with ‘heθ-’, though,

the only meaning it can have is as a proper name. The prefix ‘heθ-’ can also

be used to indicate respect or to bring emphasis to the name.

The ‘le-’ diminutive means ‘little’ and can be combined with basically

any noun:

(36)

a. iŋos

‘insect’

b. le-iŋos

dim-insect

‘little insect’

For (36b), the pitch accent would fall on the [i] of ‘iŋos’. Some words have

diminutive forms as part of the basic vocabulary; for those words, the di-

minutive fuses with the base to become a new, single word.

(37)

a. θelune

‘person’

b. leθelune

‘child’ (lit. ‘little person’)

c. le-θelune

dim-person

‘little person’ (as in, a short person or otherwise small per-

son)

The accent in (37b) is on the initial [le]: ‘léθelune’. The accent on the di-

minutive shows that the word is more of a compound and that the diminu-

tive has become part of the base itself. That is distinguished, then, from the

non-compounded form, in which the accent would not fall on the ‘le-’. The

accent in (37c) is on the [θe]: ‘leθélune’. Any compounded forms could

then have the diminutive added:

A GRAMMAR OF HIUTSAθ

33

(38)

a. le-leθelune

dim-child

‘little child’

b. *le-le-θelune

dim-dim-person

As the examples in (38) show, the compounded form can take the diminu-

tive, but the non-compounded forms can only take one diminutive, making

(38b) ungrammatical.

The pejorative ‘ɑɸ-’ can only be used with nouns that denote animate

nouns with volition; the root ‘AΦ’ literally means ‘thing’ or ‘object’, and

so using it with an animate, volitional noun indicates that the speaker thinks

the person being denoted is little more than a thing.

(39)

a. e-elenɑθe

def-leader

‘the leader’

b. e-ɑɸ-elenɑθe

def-pej-leader

‘the (disliked) leader’

The pejorative prefix, as in (39b), shows extreme dislike and has no exact

translation in English. If the diminutive and pejorative are used together,

the diminutive precedes the pejorative:

(40)

a. e-le-ɑɸ-θelune

def-dim-pej-person

‘the little (disliked) person’

b. e-ɑɸ-leθelune

def-pej-child

‘the (disliked) child’

The examples in (40) demonstrate, again, the distinction between the di-

minutive as a prefix and as a compounded form.

Nouns can be turned into adjectives with the prefix ‘eθɑ-’.

(41)

a. ɸehe

‘wind’

JESSIE SAMS

34

b. eθɑ-ɸehe

adj-wind

‘windy’

As adjectives, no other nominal markings are necessary; therefore, words

with ‘eθɑ-’ do not inflect for determinacy, number, or case. The only form

that has been fused and has a shifted accent is ‘éθɑsolɑ’ (‘everyday’). In all

other forms, like the example in (41b), the pitch accent falls on the initial

syllable of the base: ‘eθɑ-ɸéhe’.

4.5 Pronouns

Pronouns behave similarly to nouns by inflecting with the same case

markings and appearing in the same sentential positions (with the exception

of pronominal subjects, which are indicated on the verb and are thus de-

leted); however, there are different distinctions made for pronouns in terms

of formality, animacy, and inclusiveness.

Singular

Plural

Informal

Formal

Informal

Formal

First

θexo

θeeme (incl.)

θeome (excl.)

Second

θesu

θeseɑ

θeume

θesutɑ

Third

θeto (vol.)

θeleɑ

θeɑtɑ (vol.)

θelutɑ

ʦito (no vol.)

ɑɸto (inani.)

tiɑtɑ (no vol.)

ɑɸɑtɑ (inani.)

Table 9. Personal pronouns

The first-person pronouns are the only pronouns to not have an informal/

formal distinction, but they do have an inclusive/exclusive distinction for

the plural pronouns. In Hiuʦɑθ, two versions of ‘we’ are made explicit:

The inclusive form of ‘we’ includes the speaker and the person being ad-

dressed while the exclusive ‘we’ includes the speaker but not the addressee.

A GRAMMAR OF HIUTSAθ

35

(42)

a. ifepɑ-to

θeeme-mɑ

believe-3s,pres 1p,incl-acc

‘She believes us’

b. ifepɑ-to

θeome-mɑ

believe-3s,pres 2p,excl-acc

‘She believes us’

In (42a), the addressee and speaker are part of the ‘θeeme’ while, in (42b),

the ‘θeome’ does not include the addressee (i.e., ‘us’ indicates the speaker

and at least one other person, but that other person is not the person being

spoken to).

The second-person pronouns have informal/formal distinctions in both

the singular and plural. The social hierarchy is determined by age so that

any Xiɸɑθe in an older generation than the speaker is addressed with the

formal ‘you’ (‘θeseɑ’). If there is a group of Xiɸɑθeho being addressed that

has at least one elder in it, the plural formal ‘you’ (‘θesutɑ’) is required.

Regardless of age, the Xiɸɑθeho never use the formal pronouns to refer to

humans.

The third-person pronouns carry the same informal/formal distinction

as the second-person pronouns, and they also carry animacy markers. The

formal third-person pronoun is only used for animate, volitional nouns (and

can be further narrowed to only being used for fellow Xiɸɑθeho). If a

speaker chooses to show disrespect for an elder Xiɸɑθe, she can use the

informal third-person pronoun ‘θeto’ to refer to the elder Xiɸɑθe (but not

when speaking to her directly). This disrespect through pronoun selection

can only be in third-person; it is a social taboo to show disrespect when

directly addressing the Xiɸɑθe in question.

The indefinite pronouns are like the personal pronouns in that they

inflect for case, but they do not carry distinctions for person, number, in-

clusiveness, animacy, or formality. The most common indefinite pronouns

(which also double as interrogative and relative pronouns) are the follow-

ing:

JESSIE SAMS

36

θe

osθe

one (pronoun for ‘person’)

some, any (unknown entity)

meloosθe

someone (lit. ‘who some’)

monɑosθe

something (lit. ‘what some’)

meɲiosθe

sometime (lit. ‘when some’)

mɑleosθe

somewhere (lit. ‘where some’)

mose

which

Table 10. Indefinite (and other) pronouns

As indefinite pronouns, the pronouns in Table 10 occur where their nomi-

nal counterparts occur in sentences—including subjects, which must be

expressed if indefinite.

(43)

a. ʦɑθhe-to meloosθe

θexo-mɑ

call-3s,pres someone,nom 1s-acc

‘Someone is calling me’

θexo-mɑ

b. ʦɑθhe-to

call-3s,pres 1s-acc

‘She is calling me’

As seen in (43a), the majority of the indefinite pronouns are considered

third-person singular (and informal). The only exception to that classifica-

tion is ‘osθe’, which is third-person plural (also informal) for verb agree-

ment. If the subject is deleted, it is assumed that the subject is known,

which is why (43b) cannot be translated as ‘someone is calling me’.

Other uses of the pronouns (i.e., interrogative and relative uses) in Ta-

ble 10 will be discussed in a later section.

A GRAMMAR OF HIUTSAθ

37

Chapter 5

Verbs

The Hiuʦɑθ verbs inflect for voice, mood, aspect, evidentuality, tense,

person, and number (the last three are included in the same inflectional

morpheme). The ordering for these inflections is the following:

Voice-Mood-Aspect-Evidentual-VERB-Tense,Person,Number

While all those inflections are possible, all except the suffixed tense, per-

son, and number have an unmarked form, so not every finite verb has all

five inflections. When a verb appears in its bare form, it is in its infinitival

form:

(44)

ʃone

‘to begin’

The verb ‘ʃone’, provided in (44), is translated as the infinitival ‘to begin’

when it carries no inflections. The inflections discussed below begin with

the suffix (tense, person, number) and then move to the prefixes, beginning

with the prefix placed closest to the verb and moving out (i.e., beginning

with evidentuals and then moving out toward voice).

5.1 Person, number, and tense

The inflectional suffixes on verbs are all fusional suffixes that mark

tense, person, inclusive/exclusive distinctions on first-person plural forms,

and formality distinctions on second- and third-person forms. The five

tenses in Hiuʦɑθ are present, past (near- to mid-past), remote past, future

(near- to mid-future), and remote future.

JESSIE SAMS

38

Present

Past

Remote Past

Future

Remote Future

Sing Plural Sing Plural

Sing

Plural

Sing

Plural Sing

Plural

1

incl.

-xo

-eme

-ko

-keme

-kɑxo

-kɑeme

-so

-seme

-sɑxo

-sɑeme

excl.

-ome

-kɑme

-kɑome

-sɑme

-sɑome

2

inf.

-su

-ume

-ku

-kome

-kɑsu

-kɑume

-sɑu

-some

-sɑsu

-sɑume

form.

-seɑ

-sutɑ

-ke

-kotɑ

-kɑe

-kɑutɑ

-se

-sotɑ

-sɑe

-sɑutɑ

3

form.

-leɑ

-lutɑ

inf.

-to

-ɑtɑ

-kɑ

-kɑtɑ

-kɑto

-kɑɑtɑ

-sɑ

-sɑtɑ

-sɑto

-sɑɑtɑ

Table 11. Verbs: Tense, Person, Number

In Table 11, the first-person suffixes are divided into inclusive and exclusive

for the plural forms; this distinction is the same one made for pronouns—it

determines whether or not the addressee is being included in the ‘we’. The

second- and third-person suffixes both have informal and formal distinc-

tions. The third-person rows have formal and informal backwards so that

the second-person formal row can be directly above the third-person formal

row. That shifting in rows makes it easier to see that all formal forms, out-

side of the present tense, are the same. When a verb shows formal inflection

for any tense but the present tense, its meaning is ambiguous as to whether

the speaker is saying, for example, ‘you (formal) began’ or ‘she (formal)

began’. The third-person informal suffixes are for all third-person subjects,

including inanimate, animation non-volitional, and animate volitional sub-

jects. The formal third-person suffixes, however, are only for animate vo-

litional subjects, which can be further narrowed to include only Xiɸɑθeho

subjects (i.e., humans are animate volitional subjects but would not merit

the formal suffixes).

Historically, the verbal inflectional suffixes in Table 11 were agglutinat-

ing suffixes so that tense was a separate suffix from person/number. The

present tense was the unmarked form and so took no extra suffix. The past

tense suffix was ‘-kɑ’ and the future tense suffix was ‘-sɑ’. Over time, the

‘-kɑ’ and ‘-sɑ’ suffixes blended with the person/number suffixes to form

the past and future tenses while the “pure” forms retained their status as

the remote past and remote future tenses. The personal suffixes (seen most

clearly in the present tense column) are shortened forms of the personal

pronouns; thus, ‘θexo’ is the first-person singular pronoun, and ‘-xo’ is

the suffix indicating a first-person singular subject. It is possible that at

A GRAMMAR OF HIUTSAθ39

one point in the language’s history, the verbal suffixes were more like

compounded forms that eventually dropped the first syllable of the forms

marking person and number.

Examples of the verb ‘ʃone’ inflected for tense, person, and number are

in (45):

(45)

a. ʃone-xo

begin-1s,pres

‘I begin/I am beginning’

b. ʃone-kome

begin-2p,inform,past

‘you (pl. informal) began (in the near- to mid-past)’

c. ʃone-sɑeme

begin-1p,incl,rem.fut

‘we (inclusive) will begin (in the remote future)’

The present tense in Hiuʦɑθ can be translated either as the simple present

tense or as the present progressive, as in (45a). The labeling conventions

used in this grammar for the past and future tenses are provided in (45b-c):

If the label simply reads past or fut, the near- to mid- past/future is indi-

cated; if the remote past or future are being used, the label will read rem.

past or rem.fut.

5.2 Evidentuals, aspect, mood, and voice

There are seven layers of evidentual markings in Hiuʦɑθ, which only

appear on declarative utterances: speaker’s firsthand knowledge of the

statement’s truth, heresy (neutral), heresy (speaker has reason to believe

it), heresy (speaker has no reason to believe it), speaker believes its truth

through reasoning, speaker believes it to be a possibility, and speaker is

doubtful about its truth.

JESSIE SAMS

40

speaker knowledge —

heresy

heresy/reason

ɑʦe-

ɑ-

heresy/no reason

ɑne-

belief/reasoning

possibility

doubted

lo-

i-

ʦu-

Table 12. Evidentual prefixes

The unmarked form indicates that the speaker has first-hand knowledge

of the event; as the unmarked form, it is indicative of the expectations

audiences have of their speakers to provide primarily information that the

speaker knows—without a doubt—to be true.

(46)

a. xiɲe-to

smile-3s,pres

‘she is smiling’ (and I know because I see her right now)

b. ɑʦe-xiɲe-to

here-smile-3s,pres

‘I heard she is smiling’ (neutral heresy)

c. ɑ-xiɲe-to

here,r-smile-3s,pres

‘I heard she is smiling, and I have reason to believe it’

d. ɑne-xiɲe-to

here,nr-smile-3s,pres

‘I heard she is smiling, but I have no reason to believe it’

e. lo-xiɲe-to

f.

bel-smile-3s,pres

‘I believe she is smiling through reasoning’ (e.g., I know

her, and this would cause her to smile)

i-xiɲe-to

poss-smile-3s,pres

‘she could be smiling’ (it is entirely within the realm of pos-

sibility)

A GRAMMAR OF HIUTSAθ

41

g. ʦu-xiɲe-to

dou-smile-3s,pres

‘I doubt she is smiling’ (but she could be)

The most common forms of lying in Hiuʦɑθ rely on the misuse of these

evidentual prefixes. If, for instance, a speaker says ‘xiɲeto’ in (46a) but

does not actually have first-hand knowledge of the smiling (i.e., the speaker

cannot see her and so does not know for sure that she is smiling), that is

considered a lie. The neutral heresy form, provided in (46b) is the speaker’s

way of simply saying, “I heard it” without making a comment on its believ-

ability, thus leaving it up to the addressee to decide if she believes the state-

ment. That neutral form, along with the first-hand knowledge form, are the

only forms available to speakers that do not indicate the speaker’s stance—

all other forms indicate how the speaker feels about what is being discussed

(in terms of believability). When the subject is a first-person subject (either

singular or plural), the unmarked evidentual form is the only option.

The four distinctions of aspect on verbs are aorist/simple, perfective,

imperfective, and habitual:

AOR/SIMP —

PERF

IMPERF

ni-

ɸɑ-

HABITUAL ʃɑ-

Table 13. Aspect prefixes

The unmarked form for aspect is the simple or aorist reading; examples of

aspectual prefixes are provided in (47):

(47)

a. seɲe-ko

sing-1s,past

‘I sang’

b. ni-seɲe-ko

perf-sing-1s,past

‘I had sung’

c. ɸɑ-seɲe-ko

imperf-sing-1s,past

‘I had been singing’/ ‘I was singing’

JESSIE SAMS

42

d. ʃɑ-seɲe-ko

hab-sing-1s,past

‘I used to sing’ / ‘I would sing’

The imperfective, like the example in (47c), only appears in the four past

and future tenses; in the present tense, the unmarked (simple) form, as in

‘seɲexo’, can be translated either as ‘I sing’ or ‘I am singing’. The un-

marked present tense would not, though, be translated as a habitual because

habitual present tense would carry that marking: ʃɑseɲexo ‘I sing (every

day)’.

The five possible moods of Hiuʦɑθ verbs are declarative, interrogative,

imperative/hortative, subjunctive, and optative.

DEC

INT

—

(ʦi-)

IMP/HORT xe-

SUBJ

OPT

tɑ-

lu-

Table 14. Mood prefixes

Table 14 shows that the declarative form is the unmarked form and that

the interrogative is an optional marker. The interrogative prefix is only at-

tached to the verb when the verb is in question—questions and interroga-

tive markers will be discussed more fully in a later section. The examples

in (48) provide the mood prefixes with the verb ‘neʃi’ (‘to go’):

(48)

a. neʃi-su

go-2p, pres

‘you go’ / ‘you are going’

b. ʦi-neʃi-su

int-go-2p, pres

‘are you going?’

c. xe-neʃi-su

imp-go-2p, pres

‘go!’

A GRAMMAR OF HIUTSAθ

43

d. tɑ-neʃi-su

subj-go-2p, pres

‘if you were to go’

e. lu-neʃi-su

opt-go-2p, pres

‘may you go’

The translations provided in (48) for the moods are typical. One difference

between the moods is that the imperative/hortative and optative moods can

only be used in present and future tenses; neither can be combined with the

past tenses. All other moods, though, can combine with any of the tenses.

While most of the moods are more straight-forward, the imperative mood

is the exception.

When the imperative is used with a second-person informal subject

(singular or plural), it is a command form, as in (48c); when it is used with

a second-person formal subject (singular or plural), though, it is rendered

as encouragement or urging rather than a command:

(49)

xe-neʃi-seɑ

‘you should go’

When the imperative/hortative is used with first-person or third-person, it is

the hortative ‘let…’ construction:

(49)

a. xe-neʃi-ɑtɑ

b. xe-neʃi-eme

‘let them go’

‘let’s go’

In very rare cases, the imperative/hortative could be construed as an im-

perative with the first-person singular:

(50)

xe-neʃi-xo

‘go!’ (I ordered myself) / ‘let me go’

All these instances will be glossed as imp for simplicity’s sake; however, in

that label, all the above readings are possible—the subject and context will

determine which reading is best in a particular situation.

As mentioned earlier, the interrogative marker is only used when the

verb is being questioned; otherwise, there is a separate interrogative par-

ticle that goes before the verb to indicate that a question is being asked.

JESSIE SAMS

44

(51)

a. ʦɑh ʦi-lɑʃɑ-su

int-do-2s, pres

int

‘what are you doing?’ (where the expected answer is a verb)

b. ʦɑh

int

‘what are you doing?’ (where the expected answer is a noun)

lɑʃɑ-su

do-2s,pres

ʦi-monɑ

int-what

In (51a), the speaker wants to know what action/verb the addressee is doing

(e.g., singing, dancing, thinking) while the speaker wants to know what the

addressee is doing in (51b) (e.g., homework, the dishes). These distinctions

(and more like them) will be more thoroughly discussed in a later section.

While Hiiʦɑθ utilizes both active and passive voices on verbs, the pas-

sive voice is restricted in its usage, and the grammatical subject is marked

differently than it is in English.

ACT —

PASS pe-

Table 15. Voice prefixes

As Table 15 shows, the active voice is the unmarked form, and the passive

voice is the marked form. Examples of active and passive sentences are in

(52):

(52)

a. felɑ-ko

e-lelune-mɑ

hit-1s,past def-girl-acc

‘I hit the girl’

b. pe-felɑ-kɑ

e-lelune-mɑ

pass-hit-3s,past def-girl-acc

‘the girl was hit’

c. felɑ-kɑ

e-lelune-mɑ

hit-3s,past def-girl-acc

‘she hit the girl’

d. pe-felɑ-kɑ

pass-hit-3s,past

‘she was hit’

The examples in (52a) and (52c) show the active constructions in which the

girl ‘lelune’ is the object of the transitive verb ‘felɑ’ and is marked with

A GRAMMAR OF HIUTSAθ

45

the accusative case. The example in (52b), however, demonstrates that the

grammatical subject of a passive verb is also marked with the accusative

case, and the example in (52d) demonstrates that the grammatical subject

of a passive verb does not need to be outwardly expressed. Passive verbs

agree in person and number with the grammatical subject (in this case,

‘lelune’).

The passive voice in Hiuʦɑθ is restricted in that it can only be used to

indicate one of the following four situations: (1) the source is unknown or

is one of many possibilities; (2) the source does not matter; (3) the source is

known, but the speaker is keeping it to herself; or (4) the source is obvious

through verb selection. Due to these restrictions, the “doer” of the action is

never represented in a passive structure (i.e., Hiuʦɑθ has no way of saying

‘she was hit by the girl’—it would have to be rendered as either simply ‘she

was hit’ or ‘the girl hit her’). Moreover, some verbs cannot be passivized

or can only be passivized for particular meanings:

(53)

a. pɑoʃθɑmo

‘to burn’ (when active, indicates someone is burning some

one/something (transitive); when passive, indicates that fire

is responsible (intransitive))

b. pe-pɑoʃθɑmo-sɑ θeto-mɑ

pass-burn-3s,fut 3s-acc

‘she will be burned’ (she is standing close to the fire, and the

flames could reach her); cannot be used to indicate that

someone will burn her with fire

c. pɑoʃθɑmo-sɑ θeto-mɑ

burn-3s,fut 3s-acc

‘she will burn her’

For verbs like ‘pɑoʃθɑmo’, where the passive is not allowed or where it

is restricted, the speaker can still express that the subject (i.e., the person

doing the burning) is unknown through the use of indefinite pronouns:

‘pɑoʃθɑmosɑ meloosθe θetomɑ’ (‘someone will burn her’).

It is not possible for marked forms of all five inflections to appear on

the same verb since the declarative is the only mood that can take eviden-

tual markings (and the declarative is the unmarked mood); therefore, the

most marked inflections a verb can have at once is four:

JESSIE SAMS

46

(54)

pe-lu-ʃɑ-lisune-sɑu