Ma’alahi: Use of a Simplified Language to Test a

Linguistic Hypothesis

Autore: Jeffrey R. Marrone

Data della SM: 12-09-2014

Data FL: 01-01-2015

Numero FL: Florida-000028-00

Citazione: Marrone, Jeffrey R. 2014. “Ma’alahi: Use of a

Simplified Language to Test a Linguistic

Hypothesis.” Florida-000028-00, Fiat Lingua,

Diritto d'autore: © 2014 Jeffrey R. Marrone. Questo lavoro è concesso in licenza

sotto un'attribuzione Creative Commons-

Non commerciale, senza derivati 3.0 Licenza non trasportata.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

Fiat Lingua è prodotto e gestito dalla Language Creation Society (LCS). Per maggiori informazioni

riguardo alla LCS, visita http://www.conlang.org/

Maʻalahi:

Use of a simplified language to test a linguistic hypothesis

by Jeffrey R. Marrone

Abstract

Maʻalahi is a constructed language derived from a single source language, Hawaiian, with a

ruthlessly simplified Polynesian grammar. This makes it an appropriate candidate for

investigating hypotheses about the ease of L2 language acquisition. An exploratory study was

performed to determine whether grammatical features or external factors (social or personal) Sono

more significantly correlated with perceived ease of learning and correct performance on

translation tasks. Only external factors were shown to be significantly correlated.

(Please refer to glossary for unfamiliar terms.)

Hypothesis

The hypothesis of the study was that the ease of learning a language, whether a natural or a

constructed one, is not significantly related to the simplicity or regularity of its grammar; Piuttosto,

it is related to three other factors:

Cognacy: The similarity of the lexicon, and to a lesser extent, the grammar, to a language

already spoken by the learner;

Polyglottism: The number of different languages, especially from diverse language

families, spoken by the learner; e

Metalinguistic Awareness: The degree of linguistic knowledge of the learner, e il

ability to conceptualize languages abstractly.

To test this hypothesis, a study was done in which the participants were asked to learn a

grammatically simple conlang, Maʻalahi, which was based on Hawaiian – a language whose

grammar and lexicon differ markedly from any European language, and which would likely be

unfamiliar to the participants. After studying the language, the participants were asked to

perform translation exercises from Maʻalahi to English and from English to Maʻalahi. Ease of

learning was evaluated by scoring the correctness of the translation exercises, and by asking the

participants to report on how easy they felt the language was.

Maʻalahi

1

Other questions in the questionnaire were used to assess cognacy (familiarity with any

Polynesian language); polyglottism (number of languages spoken and reported competency in

loro, as well as: [a.] number of language families, e [B.] number of auxlangs spoken); e

metalinguistic awareness (as based on: [a.] formal education in linguistics, [B.] the number of

auxlangs constructed by the participant, e [c.] the number of artlangs constructed by the

participant).

The Background of the Study

For a long time, I have felt that Hawaiian was the most beautiful natural language in the world. IO

have regretted occasionally that Mozart hadn’t written any operas in Hawaiian, as lovely as

Italian opera is. Admittedly this is a subjective, aesthetic opinion.

In January 2014, David Peterson, Sylvia Sotomayor, and I were invited to be on a panel of

conlangers for the student linguistics club at University of California – San Diego. One of the

questions posed was this: “If you had to choose one single natural language for the entire world,

what would it be?” Both David and I answered “Hawaiian” immediately. (Silvia, I believe, era

somewhat dumbfounded by the alacrity of our replies.)

I decided the next day to create a conlang with the same sound (phonology and phonotactics) COME

Hawaiian.1 I agonized over what specific features of Hawaiian phonology gave it its particular

phonoaesthetics. Poi, I had one of those rare “aha!” moments of obviousness: the language that

would sound the most like Hawaiian, was Hawaiian.

The problem with learning Hawaiian, Anche se, is that its grammar is quite complex: two

categories of possessives (volitional and non-volitional), close to three dozen pronouns (if one

counts all the possessive forms), complex syntax for relative clauses, odd word order shifts for

topicalization, and inscrutable rules (still debated by linguists) governing the ellipsis of markings

for nouns and verbs. It’s a hard language to learn.

I decided to create a conlang called “Maʻalahi,” which means “simple” in Hawaiian. I retained

the Hawaiian phonology (with one change: letting /k/ and /t/ function as separate phonemes,

rather than allophones in complementary distribution), as well as the entire Hawaiian lexicon,

thus preserving the exact sound of the language. I then drastically simplified the grammar,

removing all but the most common forms, coalescing types wherever possible, and regularizing

the syntax and the rules concerning markings. The result was a grammar no more complex than

Esperanto’s, and which, I hoped, would be as easy to learn.

1 I should point out that David has already done this in his conlang, Kamakawi.

Maʻalahi

2

Around this same time, there was one of the recurrent arguments taking place on the Brown

University Auxlang list: What factors led to the adoption of an auxlang? One contingent pointed

to sociological factors, whether political, economic or socio-prestigious. The other contingent

emphasized the ease of learning the auxlang. This branched off (as usual) into a secondary

argument as to which inherent attributes of an auxlang contributed primarily to its ease of

apprendimento: Was it the simplicity and regularity of its grammar? Or the recognizability of the words

of the lexicon, because they were cognate to words in a language already spoken by the learner?

That question had never been studied quantitatively. After a thorough search through the

letteratura, and wading through unsubstantiated claims made by devotees promoting one auxlang

or another, I found only these few published articles [see Bibliography for complete citations]

peripherally related to this question:

Folia et al, Artificial Language Learning in Adults and Children

Lindstedt, Native Esperanto as a Test Case for Natural Language

Montúfar, The Contemporary Esperanto Community

Roehr-Bracklin & Tellier, Enhancing Children’s Language Learning: Esperanto as a

Tool

None of them addressed directly the issue of cognacy (the degree to which the words in the

auxlang’s lexicon resemble words in a natlang spoken by the learner)2. Tuttavia, one intriguing

discovery was that Esperanto could function as a tool to increase children’s metalinguistic

awareness, thereby accelerating their acquisition of foreign languages.3

I felt that it would be a boon to auxlangers to know which inherent linguistic factors led to the

ease of learning, and hence likelihood of adoption, of an auxlang (regardless of the extent to

which external factors are critical to that adoption). Most of the auxlangs in circulation today,

such as Esperanto, Ido, Interlingua, Sambahsa, eccetera, are based on European source languages, e

their speech communities are drawn heavily from people whose natal and/or second languages

are also European. This makes it difficult to disentangle which of the two factors, simplicity or

cognacy, is primarily contributive to the ease of learning.

My first thought about testing this was to consider the feasibility of evaluating the ease of

learning of Esperanto among the Quechua who live in the highlands of Peru and Bolivia (where I

2 Or, Anche, grammatical cognacy: The degree to which grammatical forms resemble those of a natlang spoken by the

learner.

3 As an example, British middle-school children who studied one semester of Esperanto followed by three semesters

of French, learned more French than those students who studied four semesters of French without exposure to

Esperanto. This may indicate that the purposeful construction of simplified languages can be a useful pedagogical

tool to enhance second-language acquisition.

Maʻalahi

3

had visited), as there is no commonality between Quechuan and the source languages of

Esperanto. The logistics of, and resources for, such a study, Tuttavia, would be prohibitive.

Inoltre, most of the Quechua speak Spanish as a second language, which might invalidate

any test results.

My second idea was to test the ease of learning of an auxlang that was derived exclusively from

one or more non-European source languages, among speakers of European languages. Era

then that I realized that I had already constructed such a test vehicle. It was Maʻalahi, a language

with a simplified and regularized grammar whose lexicon (and grammar) is derived from a single

source language: Hawaiian (which is definitely not Indo-European). Only those familiar with

Hawaiian, or some other Polynesian language, would be likely to recognize any words or

grammatical forms.

This was origin of the study which is presented in this paper.

Status of the Hawaiian language

The readers of this paper may find it helpful to know a little about the Hawaiian language and its

status today. Hawaiian is a language of the “Eastern Polynesian” family. Secondo

Wikipedia:

The Polynesian languages are a language family spoken in geographical Polynesia as well as

on a patchwork of “Outliers” from south central Micronesia, to small islands off the northeast

of the larger islands of the Southeast Solomon Islands and sprinkled through Vanuatu. Essi

are classified as part of the Austronesian family, belonging to the Oceanic branch of that

famiglia. Polynesians share many unique cultural traits which resulted from about 1,000 anni

of common development, including common linguistic development, in the Tonga and

Sāmoa area through most of the first millennium BC.

There are approximately forty Polynesian languages. The most prominent of these are

Tahitian, Sāmoan, Tongan, Māori and Hawaiʻian. Because the Polynesian islands were

settled relatively recently and because internal linguistic diversification only began around

2,000 anni fa, their languages retain strong commonalities.

One of the difficulties of creating a simplified Hawaiian, such as Maʻalahi, is that the Hawaiian

lingua (ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi) does not present a single target. Synchronically (questo è, the current

giorno) there are three different forms of spoken Hawaiian:

1. Those who have learned Hawaiian as children and use it as their primary language (L1).

The only speech community where Hawaiian is used as the primary language is on the

Maʻalahi

4

island of Niʻihau and a few areas on Kauaʻi. There are between 100 and 200 speakers.

The pronunciation and accent of the Niʻihau speakers differ significantly from speakers

on the other islands.

2. Those who have learned Hawaiian as children but use English as their primary language.

This community consists of mostly of elderly Hawaiians, many of whom live in the rural

parts of the islands. They speak Hawaiian mostly with their elderly friends or with their

relatives. The size of this community is rapidly shrinking, and today numbers no more

than 1,000 speakers.

3. Those who have learned Hawaiian as adults as a second language (L2), but use English as

their primary language.

Starting in the 1970s, as part of the activism movement in Hawaiian heritage and culture,

schools were started to teach Hawaiian as a second language. A large number of students

have taken language courses, often at the college level (Per esempio, at the University of

Hawaiʻi – Hilo). There may be as many as 10,000 individuals who have studied Hawaiian

as a second language, but their level of competency and subsequent frequency of usage

varies greatly. This language is sometimes referred to as “Neo-Hawaiian” to distinguish it

from the traditional language. Compared to traditional Hawaiian, Neo-Hawaiian is

grammatically simpler and more regular, and the intonation is more similar to American

English than to a Polynesian language.

In addition to those three categories, there are also four distinct diachronic (storico) periodi

during which the language was studied or examples of its usage were recorded in writing:

1. Before 1825, some early explorers documented the language. Even in this earliest period,

there is evidence of loan words from English, Portuguese and Chinese.

2. From 1825 through the end of the 19th century was a period during which Christian

missionaries documented the language, created the alphabet that is still in use today,

promoted Hawaiian literacy, encouraged the printing of newspapers in Hawaiian, e

transcribed many samples of the language.

3. After the American annexation of Hawaii in 1893, usage of Hawaiian dropped off, partly

because it was made illegal to teach it in any school (although it was still used privately at

casa). English was taught to all native Hawaiian children and became the primary language

of the territory.

4. Starting in the late 1950s, the prohibition against teaching Hawaiian was dropped, e il

first schools were opened to teach the language. Gradualmente, more immersion schools have

Maʻalahi

5

opened, college courses have been offered, and more students have learned the language,

some of whom had never been exposed to it until entering university.

There are changes in the documented language during these periods. The “modern period” (#4)

has seen the rise of Neo-Hawaiian (Hawaiian as an L2) whose grammar is simpler and more

regular than the prior time periods. [NeSmith] The documentation from the earliest period (#1) È

scant. Some of those early transcriptions appear to be inconsistent with the known rules of

Hawaiian grammar, as documented in the latter part of the 19th century. Could it have been a

transcription error? Could the storyteller who was being recorded have made an ungrammatical

utterance? Or was traditional Hawaiian more irregular than how it was spoken at the end of the

19th century? It is impossible for anyone alive to answer those questions, because there is no

standard to use as a guide.

All of this feeds into the difficulty of creating a simplified Hawaiian such as Maʻalahi. Which

time period and which version of the language should be used as a starting point? The greatest

number of speakers today consist of L2 speakers. Should Neo-Hawaiian be taken as the starting

point for constructing a simplified language? Or would it be more appropriate to use the

traditional language as it was documented during the early 19th century? As is true for all

natlangs, there is no such thing as a “pure” Hawaiian language; even the earliest documented

transcriptions show the inevitable incursion of foreign words.

What I did for the creation of Maʻalahi was to lay out, in tabular form, all the alternants, and then

do my best to arrive at a consistent scheme for regularization.

Description of Maʻalahi

A complete description of the Maʻalahi language is available on the web. Rather than repeat that

information in appendices of this document, links are provided below.

A description of the grammar, including numerous sample sentences:

http://www.temenia.org/Ma_alahi/docs/Grammar.pdf

(Note that this description of the grammar is somewhat different than what was shown to the

participants in the study. The grammar document now includes a section on the differences

between Maʻalahi and Hawaiian, and also some of the explanations and examples have been

augmented for clarity.)

A short lexicon:

http://www.temenia.org/Ma_alahi/docs/Lexicon.pdf

(Notare che, except for the “grammar words,” Maʻalahi’s lexicon is identical to Hawaiian. IL

linked document is an abridged Hawaiian dictionary of about 500 words.)

Maʻalahi

6

A reference aid listing the “grammar words” (and the section of the grammar description

where they are explained) as an aid for translation:

http://www.temenia.org/Ma_alahi/docs/ReferenceAid.pdf

Simplicity of Grammar: Comparison to Esperanto

In order to test the hypothesis that it is not simplicity of the grammar, di per sé, that makes an

auxlang easy to learn, it is important to quantify, in una certa misura, the degree of difficulty of the

grammar of a language. This turns out to be an extremely thorny question to answer, perhaps an

intractable one.

Per prima cosa, it is hard to assign numerical measures to grammatical attributes. Per esempio:

Are inflectional grammars always more difficult than agglutinating or isolating ones? To what

extent? If the inflections are regular, but the equivalent ways to express those elements in an

isolating language are irregular with many exceptions, then how does one account for that?

One possibility is to fully specify the grammar with formal transformational rules. In my

esperienza, language learners do not conceptualize the grammars of languages in that way, Ma

rather use much less formal rules, or rules-of-thumb, which allow for exceptions.4 Formal

syntactic rules, Inoltre, do not take into account rules bound to the semantic meanings of

parole, such as gender (Is Susan a “he” or a “she”?), or animacy (Is the blowing of the wind

volitional or not?), all of which increase the difficult of attaining competency in a language.

Perciò, I do not believe that it is possible to accurately quantify the difficulty of a grammar in

a way that is relevant to the question of how easy it is for a learner to internalize the rules.

Tuttavia, è possibile, secondo me, to make crude comparisons. Virtually everyone

would agree that the grammar of modern standard Arabic is more complex than the grammar of

Esperanto. If nothing else, the fact that Haywood & Nahmad’s A New Arabic Grammar is over

450 pages in length (with another 150 pages for index, appendices, glossary, and supplements)

should serve as a demonstration of the greater complexity of Arabic grammar.

As part of this study, I wished to quantify, however roughly, the complexity of Maʻalahi’s

grammar relative to Esperanto’s. Many proponents of Esperanto point out that its grammar is so

simple that it can be described in only sixteen rules (and thereby “proving” to their satisfaction

its ease of learning) – see Don Harlow’s webpage (http://donh.best.vwh.net/Esperanto/rules.html)

for an example. Following that model, I created a short, preliminary table comparing the

grammars of the two languages:

4 As in the well-known English-spelling mnemonic: “I before E / except after C / or when sounded like A / as in

neighbor or weigh.”

Maʻalahi

7

Maʻalahi

Esperanto

Pages to describe grammar

Number of rules

14

25

Number of Letters/Phonemes 19

Note:

13

20

28

1. The page count for Maʻalahi excludes the sections on the differences from Hawaiian.

2. Differing text formats makes page count a crude comparison indeed.

3. The “Sixteen Rules of Esperanto Grammar” contain four implicit rules which are not

stated (ad esempio: word order is SVO) – perhaps because these seem self-evident to an

audience consisting primarily of Europhones. These four implicit rules are included in the

above total.

From this very short comparison we see that the descriptions of the languages are approximately

of the same length, with about the same number of grammatical rules and of phonemes. Pursuing

this tack, I made a more detailed table, counting the number of grammatical features of each

lingua:

Maʻalahi Esperanto Notes

Verbal Types

Verbal Forms

Nominal Forms

Adjectival Forms

Adverbial Forms

3

6

1

0

0

Pronouns

14

Prepositional Cases

Types of Negation

Directionals

Demonstratives

Interrogatives

Comparatives

2

3

4

6

8

0

2

12

4

4

1

9

1

3

0

4

9

3

Esperanto: transitive & intransitive

Maʻalahi: transitive, intransitive & stative

12 forms in Esperanto (rich TAM structure

common to Euro-langs)

Esperanto: singular/plural &

nominative/accusative

No adjectives in Maʻalahi – Esperanto:

singular/plural, nominative/accusative

No adverbs in Maʻalahi

14 forms in Maʻalahi (because of dual number

and exclusive/inclusive 1st person, common to

Polynesian-langs)

No directionals in Esperanto (discounting use of

accusative to indicate destination)

Maʻalahi uses stative verbs. Esperanto:

standard/comparative/superlative

Maʻalahi

8

Maʻalahi Esperanto Notes

Ellipsis

2

0

TOTAL

49

52

Subject and direct object markers of common

nouns can be nulled in Maʻalahi

These totals are crude. All they indicate is that

the complexity of the two grammars are roughly

pari. A natlang such as English or Russian

would have a total of over 200.

Certo, the comparison shown in the above table is crude, and open to interpretation and

criticism. My intent is not to prove that the grammar of Maʻalahi is simpler than Esperanto, Ma

merely that Maʻalahi’s grammar, which was regularized and simplified based on auxlang design

principals, is approximately as simple an Esperanto’s or any other major auxlang, such as Ido,

Interlingua, or Sambahsa.

It is important to add, that although Maʻalahi’s grammar may be simple based on crude objective

measures as shown in the above table, it is very different from the SAE grammars that so many

of today’s auxlangs possess. It is this combination of properties: simple grammar, yet with little

similarity to SAE languages, that makes Maʻalahi a good test vehicle to investigate the question

as to whether it is the simplicity of the grammar, or the cognacy of the lexicon and grammatical

features, that makes an auxlang easy to learn.

Description of the Study

A letter inviting participation in the study was emailed to the LCS Members listserver, and to the

Conlang and Auxlang listservers maintained by Brown University. A similar letter was posted on

the Facebook groups: Conlangs, Auxlangs, Polyglots, and Omniglot. The main part of that letter

is reproduced below:

Would you be willing to participate in a sociolinguistic study to test theories about the

ease of learning of auxiliary languages? (Please consider this, even if you have never

learned nor constructed an auxiliary language.)

If you volunteer, you will be sent:

(1) a short, multipart questionnaire;

(2) a concise 14-page description of an auxlang’s grammar (written for linguists

or conlangers, not as a primer);

(3) a 500-word lexicon;

(4) a translation exercise.

You will be asked to study the grammar and lexicon of the language, to complete the

translation exercise and the questionnaire, and to return your answers to me.

Maʻalahi

9

The questionnaire consisted of four parts:

1. Preliminary questions about the languages spoken by the participant, the level of formal

linguistics education, and any languages constructed by the participant;

2. Instructions on reading/studying the description of Maʻalahi (phonology, orthography,

grammar, examples);

3. The translation exercises;

4. Final questions about the participant’s opinion concerning the difficulty of Maʻalahi and

the translation exercises.

62 individuals responded and requested the materials to participate in the study. Of those, 28

completed the questionnaire and translation exercises and returned them to me. Of the others, 11

notified me that they had decided to quit the study without completing it, and 23 never responded

to my follow-up emails.

Of the 28 participants:

Two were or had been professional linguists; eleven others had studied linguistics at

university

Four were bilingual from childhood

All participants spoke at least two natlangs, with two participants speaking a total of

eight apiece; the average was slightly over four

Fourteen spoke at least one auxlang with some degree of fluency

Eighteen had constructed at least one artlang (although sketchlangs were included in

this count)

For the purposes of the study, the participants self-evaluated their competency level in the

natlangs and auxlangs that they spoke. In terms of the languages constructed by the participants,

it was clear from the responses in the questionnaire that some of the listed languages were

significantly developed while others were mere sketches. I was not sure that the raw number of

artlangs constructed by each participant would result in meaningful comparisons. Perciò, IO

created a scale summarizing the “skill level” of the artlangs listed by the participants, using the

following rubric:

0 = no artlangs constructed

1 = only sketchlangs

2 = at least one significantly developed artlang

3 = at least one significantly developed artlang plus other incomplete artlangs

4 = at least two significantly developed artlangs

5 = more than two significantly developed artlangs

This “skill level of artlangs” was used as a variable in the statistical analysis, as well as the raw

count of artlangs constructed by the participant.5

5 It is acknowledged that the assessment of this skill level is a subjective judgment by me.

Maʻalahi

10

There were two sets of translation exercises: a set of five sentences to translate from Maʻalahi to

English, and a second set of five translations from English to Maʻalahi. Each set was arranged so

that the first exercise was easy and the last one was difficult, with an increasing level of

difficulty for the intermediate exercises.

Most of the participants completed the entire questionnaire and, to the best of their ability, all the

translation exercises. A few of them, due to noted lack of time or interest, completed only a

portion of the translation exercises.

Each translation was scored as follows:

3 = correct, or only minor errors

2 = “medium” errors

1 = major errors

0 = not attempted

A perfect score for all ten translation exercises was 30. Four of 28 participants (14%) achieved

perfect scores. Only six participants (21%) scored 20 or less. The average score was 23.7.

The data was analyzed using Epi Info 7, a free statistical analysis package developed for

epidemiologists.

Quantitative Analysis

The results of the study are presented in relationship to the hypothesis, reiterated below:

The ease of learning a language is not significantly related to the simplicity or regularity

of its grammar; Piuttosto, it is related to three factors:

Cognacy: The similarity of the lexicon, and to a lesser extent, the grammar, to a

language already spoken by the learner;

Polyglottism: The number of different languages, especially from diverse language

families, spoken by the learner; e

Metalinguistic Awareness: The degree of linguistic knowledge of the learner and the

ability to conceptualize languages abstractly.

To evaluate the “ease of learning” two factors were used. One was the participant’s reported ease

of learning after having studied the Maʻalahi language and completed the translation exercises.

As this was a subjective factor, the correctness of the translation exercises was also used as a

proxy for the ease of learning.

Maʻalahi

11

These two factors correlated closely. [Correlation coefficient r = 0.51. Spearman’s p = 0.0066.]

Perciò, throughout the remainder of the analysis, the correctness of the translation exercises

was used to evaluate the factors related to the ease of language learning.6

The supposition that the simplicity of a language’s grammar accounts, in larga misura, for ease

of learning, was not supported by the study. Come è noto, most learners of Esperanto (e

similar European-language-based auxlangs) report that it is easy to learn. Come discusso sopra,

the grammar of Maʻalahi is roughly as simple as Esperanto’s. Perciò, if the simplicity of

grammar was the overriding factor to determine ease of learning, the expectation would be that a

significant proportion of the participants would report that learning Maʻalahi was similarly easy.

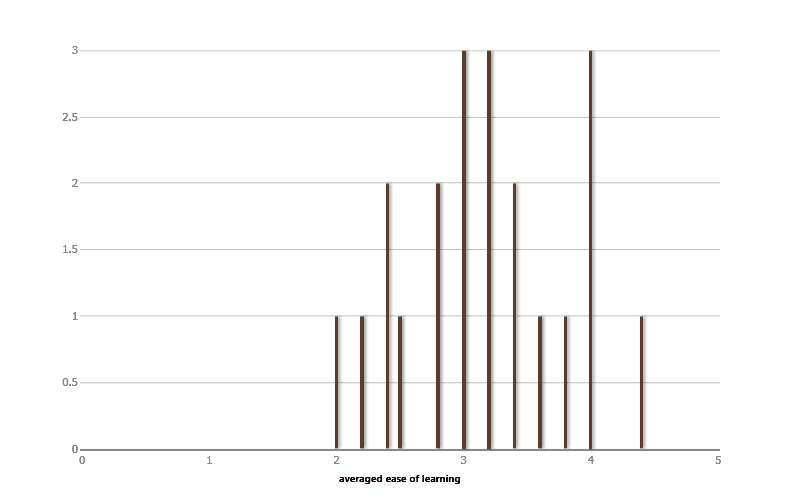

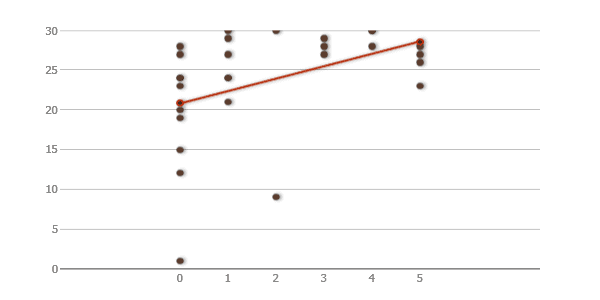

Tuttavia, from inspection of Chart 1, it can be seen that the reported ease of learning varied

greatly. For a constructed language with a simple grammar, one would expect a much narrower

distribution with a mean close to the left-hand side of the chart. Considering that the participants

in the study have a much higher degree of competency and interest in languages and linguistics

than the general population, this shows that grammatical simplicity or regularity for these

participants were minor factors in the ease of language learning.

Chart 1

t

N

tu

o

C

Ease of Learning (1 = “very easy” to 5 = “very difficult”)

6 Throughout the study, Spearman’s correlation analysis was used instead of the more common Pearson’s analysis,

since Spearman’s analysis is more tolerant of non-normal data, such as found in this study.

Maʻalahi

12

To investigate cognacy, the participants were split into three groups:

(1) Those who spoke any Polynesian language

(2) Those for whom none of their native languages was a European language

(3) Everyone else

This analysis could not be performed. Only one participant did not list a European language as

one of his/her native languages. No participants had more than a minimal familiarity with any

Polynesian language. Although seven (25%) of the participants had a slight degree of exposure

to a Polynesian language, either in their studies or during travel to the area, this casual exposure

was insufficient to distinguish them from the other participants.

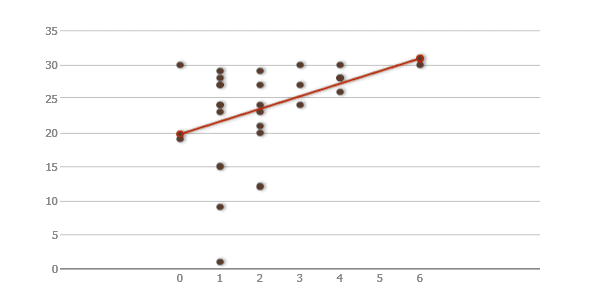

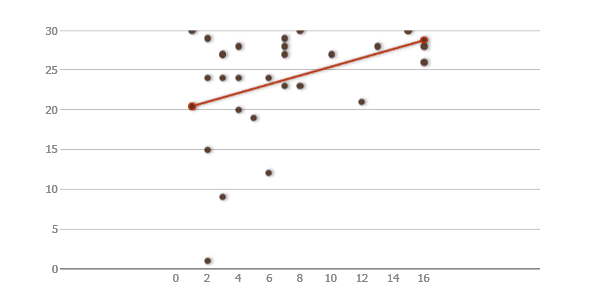

Significant correlation was found between the ease of learning of Maʻalahi and polyglottism.

Analysis of the number of childhood native languages was not fruitful, because no participant

listed more than two. The other factors (the number of non-native natlangs spoken, the number

of families to which those natlangs belong, and the reported competency level in those natlangs),

were all shown to correlate with the reported ease of learning and the correctness of the

translation exercises. Charts 2 and 3 show examples of these relationships.

Chart 2

s

N

o

io

t

l

UN

s

N

UN

r

T

f

o

s

s

e

N

t

c

e

r

r

o

C

Non-Native Natlang Families

Correlation Coefficient: r = 0.39

Spearman’s Correlation: p = 0.0419

Maʻalahi

13

Chart 3

s

N

o

io

t

l

UN

s

N

UN

r

T

f

o

s

s

e

N

t

c

e

r

r

o

C

Total Natlang Competency Level

Correlation Coefficient: r = 0.37

Spearman’s Correlation: p = 0.1067

Metalinguistic awareness, as defined in this study, was not found to be related to the ease of

learning of the Maʻalahi language. Some of the factors used to assess metalinguistic awareness

did not correlate. Per esempio, no statistically significant relationship was found between the

level of formal linguistics study and reported ease of language learning.

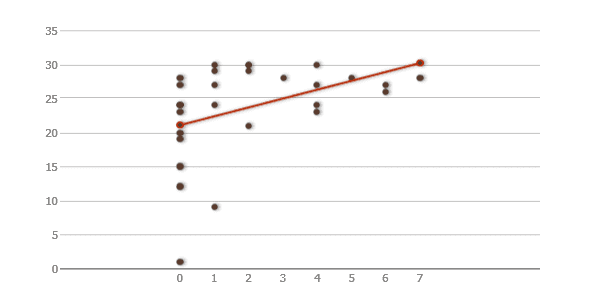

Tuttavia, one factor, in particolare, did correlate highly. This was the number of artlangs

constructed by the participant. The number of artlangs, and the assessed skill level (the degree of

completeness to which those artlangs were developed), were predictive of the correctness of

translations and the reported ease of learning in this study. Charts 4 and 5 show, rispettivamente, IL

relationships for the number of constructed artlangs, and the skill level of same.

Maʻalahi

14

Chart 4

Number of Artlangs Constructed

Correlation Coefficient: r = 0.40

Spearman’s Correlation: p = 0.0130

Chart 5

s

N

o

io

t

l

UN

s

N

UN

r

T

f

o

s

s

e

N

t

c

e

r

r

o

C

s

N

o

io

t

l

UN

s

N

UN

r

T

f

o

s

s

e

N

t

c

e

r

r

o

C

Skill Level of Constructed Artlangs

Correlation Coefficient: r = 0.42

Spearman’s Correlation: p = 0.0073

Maʻalahi

15

Inoltre, if the number of constructed artlangs is converted to a binomial variable (no artlangs

constructed versus at least one), the correlation is even stronger. [Correlation coefficient r = 0.47.

Spearman’s p = 0.0019.] Chiaramente, the act of constructing even a single artlang is related to one’s

ability to learn Maʻalahi, and probably any language (although whether this is a causal

relationship is undetermined).

Perciò, within the limitations of this study, as discussed below, it is concluded that simplicity

or regularity of the grammar is not significantly related to the ease of learning that language, Ma

rather that the major factors are the level of the learner’s polyglottism and the extent to which

he/she has been involved in language construction.

Qualitative Analysis

At the end of the questionnaire, the participants were invited to offer additional comments. 24 of

28 chose to do so. From analyzing these responses, some conclusions can be drawn:

1. Twelve of the participants volunteered that they felt that the materials (the grammar

description and the lexicon) were inadequate for learning the language. There were

suggestions to:

Incorporate more examples

Include interlinear glosses

•

•

• Merge the lexicon and the grammar reference aid

• Explain in more detail unfamiliar concepts, such as directionals or modal verbs or

passive intransitives

• Add a series of progressive lessons

Even though the letter soliciting volunteers stated that the material was “written for linguists

or conlangers,” and the instructions said that a primer was not available, it seems that for half

of the participants the description of the grammar was overly terse. From other comments, Esso

appeared that some of the participants, rather than studying the grammar, merely skimmed it

and then turned directly to the translation exercises, during which they paged through the

grammar using it as a reference. This was true even for participants who indicated that they

had studied linguistics at the university level. Ovviamente, this made completing the

translation exercises more time consuming, although it didn’t decrease the correctness of the

traduzioni.

The take-away from this is that creators of future studies which ask volunteers to learn a test

language should consider preparing progressive lessons similar to what is found in a

Maʻalahi

16

language textbook, even if the population from which the participants are drawn consists

mostly of conlangers or polyglots.

2. As is common among the conlang and auxlang community, many participants freely offered

helpful, constructive criticism of Maʻalahi, and how it ought to have been designed. IL

most prevalent comment was that the use of the ʻokina as a letter, and of the macron as a

diacritical mark indicating a long vowel, was “problematic” and made lexical lookup

difficult. I doubt that these same individuals have similar problems with the circumflex or

breve as used in Esperanto, or for that matter, the umlaut of German. This raises the question

about whether their perceived difficulty lends additional weight to my hypothesis that it is

familiarity with a language one already knows that contributes most strongly to the ease of

learning of a new language (although I had not initially considered that this hypothesis would

extend to a language’s orthography).

3. Other critical comments focused on the phonology, specifically the small size of the phonetic

inventory, which leads to a large number of homonyms, and words that differ only by a short

versus a long vowel, or the presence versus the absence of an ʻokina, (which are distinctive in

Hawaiian). I wonder if the phonetic inventory had been larger than is common among

European languages, similar comments would have been forthcoming complaining that the

large number of phonemes made the language unnecessarily difficult.

4. Of the 28 participants, seven of them (25%) recognized Maʻalahi as a Polynesian language

(identified either as Hawaiian, or some suggested it was based on Tahitian or Niuean). None

of these participants, unfortunately, were fluent or competent speakers of any Polynesian

lingua, which would have led to additional useful results for this study.

5. E infine, six of the participants volunteered that participating in the study was fun,

whereas three participants said that it was not fun.

Discussion of Results

Before discussing the results of the present study and their implications, it must be noted that a

limitation is the nature of the sample. It is not a representative sample of the general population

whatsoever. It is a “convenience sample” drawn from a subpopulation of language enthusiasts.

Inoltre, all the participants were fluent in English, and most knew at least one other European

lingua. Half of the participants spoke an auxlang with a reasonable degree of competency.

Many had studied Latin and/or classical Greek. A more extensive and thorough study would

include participants selected from diverse regions of the world, including those whose spoke no

European language, and who possessed varying degrees of linguistic interest.

Maʻalahi

17

An open question is whether the results of this small study can be extended to the general

population. I believe the answer is yes. Considering that the sample of participants was drawn

from among language enthusiasts, the results could reasonably be even more extreme for the

general population. This would indicate, pertanto, that the focus of most auxlangers, on the

development of ever simpler and more regular grammars, may be misplaced. Most auxlangs

today are based on European languages (leading to the somewhat pejorative term: “euroclone”).

The purported ease of language learning and usage claimed by many auxlangers may be

attributable to nothing more than that the learners of those auxlangs natively speak a European

language and are benefitting from the cognacy of the auxlang to their own native language, o

possibly to some other European language in which they are fluent.

The present study implies that the learning of a European-language-based auxlang would be

much more difficult by a monolingual speaker whose native language was Quechuan, o

Hawaiian, or any non-European language. Those who attempt to construct a “worldlang” (an

auxlang whose target is everyone throughout the world) may be more successful if they

downsize their ambitions to working on a regional auxlang, such as Afrihili [Annis] che è

aimed at a target of sub-Saharan African speakers.

The results of this small study (and someday, fiduciosamente, of a more extensive one), should be of

significant interest to those who are involved in the construction of auxlangs. The discord and

schisms between aficionados of one auxlang or another have perplexed outsiders over the

seemingly minuscule grammatical or orthographic differences that are the source of the

arguments. What this study shows, Anche se, is that these tiny differences are irrelevant to the ease

of learning of the auxlang. Since any auxlang which is deemed to be successful must be easy to

learn so that its usage may expand, it would be advisable for auxlangers to desist from these

disputes and turn their focus to the experimental investigation and objective determination of the

factors which are more likely to lead to the dissemination of their languages.

This study implies, considering the vast grammatical, lexical and phonetic differences that exist

between the languages of the world, that the adoption of a true international auxiliary language

cannot be driven by features or attributes inherent to the language, but rather by external

economico, politico, or religious factors. The 19th century dream of a true international auxiliary

lingua, untainted by the history of conquest and domination [Eco], cannot be achieved unless

its propagation is forced, or strongly encouraged, by such external factors.

The Use of Conlangs for Experimental Linguistics

Most conlangers are familiar with the two main categories of constructed languages: artlangs (UN

conlang created for an artistic purpose, such as literature, film, or for deepening the reality of a

science-fiction world), and auxlangs (a conlang developed to be spoken as an auxiliary language

Maʻalahi

18

by a region or by the entire world). There are also engelangs (engineered languages developed to

investigate the capabilities and limitations of human cognition or linguistic processing).

A subset of engelangs could be denoted as a “testlang," questo è, a conlang developed primarily for

the purpose of testing a particular linguistic hypothesis. In quanto tale, its proper domain is confined to

the research laboratory; there is never an intent to promote it as a candidate IAL nor to have it

spoken by characters in a fantasy novel.

The most well-known testlang is Loglan/Lojban. Originally it was developed by James Cooke

Brown to test the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. To my knowledge, no such experiment of Sapir-

Whorf has ever been performed, perhaps due to the schism between early speakers of the

lingua. That failure is no reason, Tuttavia, to desist from creating testlangs whose purpose is

to probe the intricacies of neurolinguistic processing, or address any other linguistic hypotheses.7

The original intent behind the construction of Maʻalahi was not as a testlang. Piuttosto, I created it

merely because I wanted a simple language that sounded as much as possible as Hawaiian.

Tuttavia, as I was working on one of the later drafts of Maʻalahi, I realized it could function as a

test vehicle to answer the question of whether grammatical simplicity/regularity or lexical

cognacy were more important factors in the ease of learning of an auxlang.

I would like to take this opportunity to encourage my fellow conlangers, especially those who are

professional linguists in university settings, to consider the craft of testlanging as a relatively

unused experimental technique.

There have already been some cognitive-psychological studies which have purported to use

“artificial languages” or “artificial grammars.” [Folia] Tuttavia, these so-called artificial

languages are little more than sequences of symbols, which may or may not conform to an

arbitrary “grammatical” rule created by the experiment designer. In my opinion, these studies do

not actually examine the type of neurolinguistic processing that occurs with natural language

apprendimento. I propose that more fully developed artificial languages would function better to tease

out the intricacies of language learning.

It is my belief that the conlang community is positioned to offer help in the custom design of

constructed languages to function as testlangs.

The Future of Auxlangs

The foregoing may give the impression that I am opposed to auxlangs, or believe, almeno, Quello

7 Perhaps, someday, a testlang will be developed to examine Chomsky’s hypothesis of deep structure and

transformational grammar.

Maʻalahi

19

the pursuit of a true international auxiliary language is a pointless exercise. Nothing could be

further from the truth.

Infatti, I believe that sometime in the future (after I, and all those who are alive today, are long

gone), an IAL to be used by the world’s populace will be designed, selected and authorized by

the world’s governments. Tuttavia, this process will be brought about by external factors, based

on the widely perceived benefits of peace and political and economic cooperation and

communication. No language, no matter how cleverly designed, nor how aesthetically attractive,

nor how easy to learn, can, on its own merits, overcome the political inertia and provincial

nationalism that pervades the world of today.

The conclusions presented in this study, Anche se, may be a guide to those who wish to pursue the

craft of auxlang design. They indicate that it may be fruitless to pursue a goal of designing a

worldlang which will be easily learnable by all. It may be possible, Anche se, to create a regional

auxlang, such as Afrihili [Annis] or Lingua Franca Nova, whose lexical and grammatical source

languages all belong to one, or several closely related, linguistic families, and the learning of

which may be perceived as relatively easy by the intended target audience.

This does not mean, I wish to reiterate, that there never will be an IAL, but rather that its

adoption will not be an easy or painless process. No such language, in an environment of

linguistic diversity, can ever be driven solely from the grassroots; its promulgation must also be

supported economically and politically by the major sovereign powers of the world.

Outside of the personal enjoyment one may experience in constructing an engineered language,

there appears to be no reward in the activity of auxlanging (though this could be said of

artlanging as well). Worldlang development today can thus best be perceived as a playful

investigation into the parameters of language design, whose time of fruition has not yet arrived.

This investigation, ciò nonostante, can produce prototypes that may serve as examples for that

future time, when the world political structure will be finally ready for linguistic unity.

Acknowledgments

My appreciation to David Peterson for his encouragement in this project and his reviews and

critiques of early versions of the Maʻalahi language, to Philip Newton for detailed proofreading

and the correction of several errors, and to Joan Jensen for the statistical analysis in this study

and proofreading the write-up.

Maʻalahi

20

Glossary

Artlang

Auxlang

Conlang

Engelang

IAL

L1

L2

LCS

“Artistic Language” – Any conlang that is created primarily for aesthetic

reasons, Per esempio, to increase the realism in literary works or films.

“Auxiliary Language” – Any conlang that is purposefully created as a

means of communication between people who do not share a common

lingua, such as Esperanto, Ido, Sambahsa, eccetera.

“Constructed Language” – Any language that has been consciously

devised (as opposed to natlang).

“Engineered Language” – Any conlang designed to fulfill specific

objective criteria, such as Ithkuil or Toki Pona. Most auxlangs could be

considered to be a type of engelang.

“International Auxiliary Language” – Any auxlang whose target is all the

peoples of the world, as opposed to a regional auxlang.

Same as “native language.”

Any non-native language spoken by a person, questo è, any language that

was learned after the age of six years (sometimes referred to as a “foreign

language”).

“Language Construction Society” (http://conlang.org/) – The premier

organization for those active or interested in the art and science of

constructing languages.

Native Language

Any language spoken by a person that was learned from birth (or before

the age of six years, according to some linguists).

Natlang

SAE

“Natural Language” – Any language that is not purposefully constructed,

but that has arisen “naturally,” such as English, cinese, Hindi, Spanish,

eccetera (as opposed to conlang).

Abbreviation for “Standard Average European,” a term used to describe

auxlangs derived exclusively or primarily from Indo-European source

lingue.

Sketchlang

A “sketchlang” or “sketch” is any conlang that is not fully developed,

perhaps only an idea or a concept for a conlang.

Maʻalahi

21

SVO

TAM

Testlang

Abbreviation for Subject/Verb/Object, as applied to word order.

Abbreviation for Tense/Aspect/Mood, as applied to the grammar of verbs.

“Test Language” – Any engelang designed to test or demonstrate a

linguistic hypothesis, such as Loglan (or Maʻalahi).

Worldlang

Same as “IAL.”

Bibliografia

Annis, William S. Pomeriggio: an African Interlanguage. Fiat Lingua, April 2014.

[http://fiatlingua.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/fl-00001F-00.pdf]

A description of the regional auxlang, Pomeriggio, created by K. UN. Kumi Attobrah in 1967

as a lingua franca for sub-Saharan Africa.

Eco, Umberto. The Search for the Perfect Language. Trans. James Fentress. 1995. Blackwell

Publishing.

The history of language construction in Europe from the middle ages to the present time.

Elbert, Samuel H. & Pukui, Mary Kawena. Hawaiian Grammar. 1979. University of Hawaiʻi

Press.

The most complete grammar of the Hawaiian language. It covers all parts of speech in

detail, differing speech patterns between 19th century, Presto, and late 20th century usage,

rare constructions, and different linguists’ opinions on disputed areas of Hawaiian

grammar.

Folia, Vasiliki; Uddén, Giulia; de Vries, Meinou; Forkstam, cristiano & Petersson, Karl Magnus.

Artificial Language Learning in Adults and Children. Language Learning, vol. 60, supplement 2,

Dec. 2010, pp. 188-220.

[http://pubman.mpdl.mpg.de/pubman/item/escidoc:541621:6/component/escidoc:541620/Folia-

LanguageLearning10.pdf]

A report on experiments in which adults and children are trained in an artificial

(constructed) language and tested on their ability to distinguish grammatical from

ungrammatical syntax. The neurological foundation of syntax learning for the artificial

language is tested using fMRI and TMS scanning. The results indicate that syntax

learning of an artificial language uses the same neural apparatus as for a natural language.

Maʻalahi

22

Lindstedt, Jouko. Native Esperanto as a Test Case for Natural Language. Festschrift in Honour

of Fred Karlsson, pp. 47-55. SKY Journal of Linguistics, vol. 19:2006 supplement.

[http://www.linguistics.fi/julkaisut/SKY2006_1/1FK60.1.5.LINDSTEDT.pdf]

A study of the usage of Esperanto among L1 speakers with particular attention to changes

introduced by the “nativization” of Esperanto. The author finds that the changes are

minimal and due mostly to crossover from the subjects’ other native languages. Lui

concludes that the lack of change is due to the fact that Esperanto grammar is not learned

prescriptively as a formal grammar, but from the reading of Esperanto texts, Quale

allows for the natural and unconscious learning of grammar, similar to natural languages.

Montúfar, Adelina Mariflor Solis. The Contemporary Esperanto Speech Community. Fiat

Lingua, gen. 2013. [http://fiatlingua.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/fl-000010-01.pdf]

A description of today’s Esperanto speech community, focusing on why individuals

choose to learn Esperanto, the demographics of Esperanto speakers, and the factors that

lead to their coalescence into a speech community.8

NeSmith, R. Keao. Tūtū’s Hawaiian and the Emergence of a Neo-Hawaiian Language. ʻŌiwi

Journal—A Native Hawaiian Journal, vol. 3, 2005. [http://www.traditionalhawaiian.com/Oiwi-

Journal-_3-1-09_.pdf]

A description of the evolution of “Neo-Hawaiian” among L2 speakers with limited

exposure to L1 speakers, and examples of the differences between Neo-Hawaiian and

traditional Hawaiian.

Pukui, Mary Kawena & Elbert, Samuel H. Hawaiian Dictionary. Revised edition, 1986.

University of Hawaiʻi Press.

The most complete Hawaiian-English / English-Hawaiian dictionary. Also see the

excellent online dictionary: Nā Puke Wehewehe ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi

[http://www.wehewehe.org/]

Roehr-Brackin, Karen & Tellier, Angela. Enhancing Children’s Language Learning: Esperanto

as a Tool. 5th Essex Language Conference for Teachers. 29 June 2013.

[http://www.essex.ac.uk/langling/documents/elct/2013/esperanto_tool.pdf]

A PowerPoint presentation on the use of teaching Esperanto to middle-school children to

increase their metalinguistic awareness, and the benefits this had for their subsequent

performance on learning a foreign language.

8 Of particular relevance, for this study, is the fact that Asian learners of Esperanto had a good degree of fluency in

English previously, which may indicate that the ease of learning of Esperanto is due partly to its cognacy with

English and other European languages.

Maʻalahi

23