Presentation of the Duišan and Kven language

Autor: Sebastien Thomine

MS-Datum: 09-08-2021

FL-Datum: 03-01-2022

FL-Nummer: FL-00007E-00

Zitat: Thomine, Sebastien. 2021. “Presentation of the

Duišan and Kven language” FL-00007E-00,

Fiat Lingua,

March 2022.

Urheberrechte ©: © 2021 Sebastien Thomine. Diese Arbeit ist

lizenziert unter einer Creative Commons Namensnennung-

NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unportierte Lizenz.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

Fiat Lingua wird von der Language Creation Society produziert und gepflegt (LCS). Für mehr Informationen

über die LCS, Besuchen Sie http://www.conlang.org/

Autor: Sébastien Thomine

Presentation of the Duišan and Kven language

Table of contents

Introduction …………………………………………………………… p.1

1. The sound systems of Duišan and Kven …………………………… p.3

1.1 The vowel system

1.2 The consonant system

1.3 Basic phonotactics of Duišan and Kven

2. The basic nominal system of Duišan and Kven ………………… p.5

2.1 Personal pronouns

2.2 Possessive pronouns

2.3 Word types

2.4 Preposition system

2.5 Adjectives

3. The basic verbal systems of Duišan and Kven ………………….. p.9

3.1 Verb types

3.2 Alignment

3.3 Mood and tenses

3.4 Aspects

3.5 Interrogative words

3.6 Adverbs of manner

3.7 Negation

3.8 Evidentiality and derivation patterns

4. A short text in Duišan …………………………………………….. p.14

Referenzen

Appendix (numeral system and glossary)

This paper is adapted from the final exam paper of the course HIF-1022 Constructed language

given at the Arctic University of Tromsø in Norway during the spring semester of 2021. Dabei

paper I present the constructed language Duišan and compare it with the Kven language, An

minority language from the Uralic language family spoken in Northern Norway.

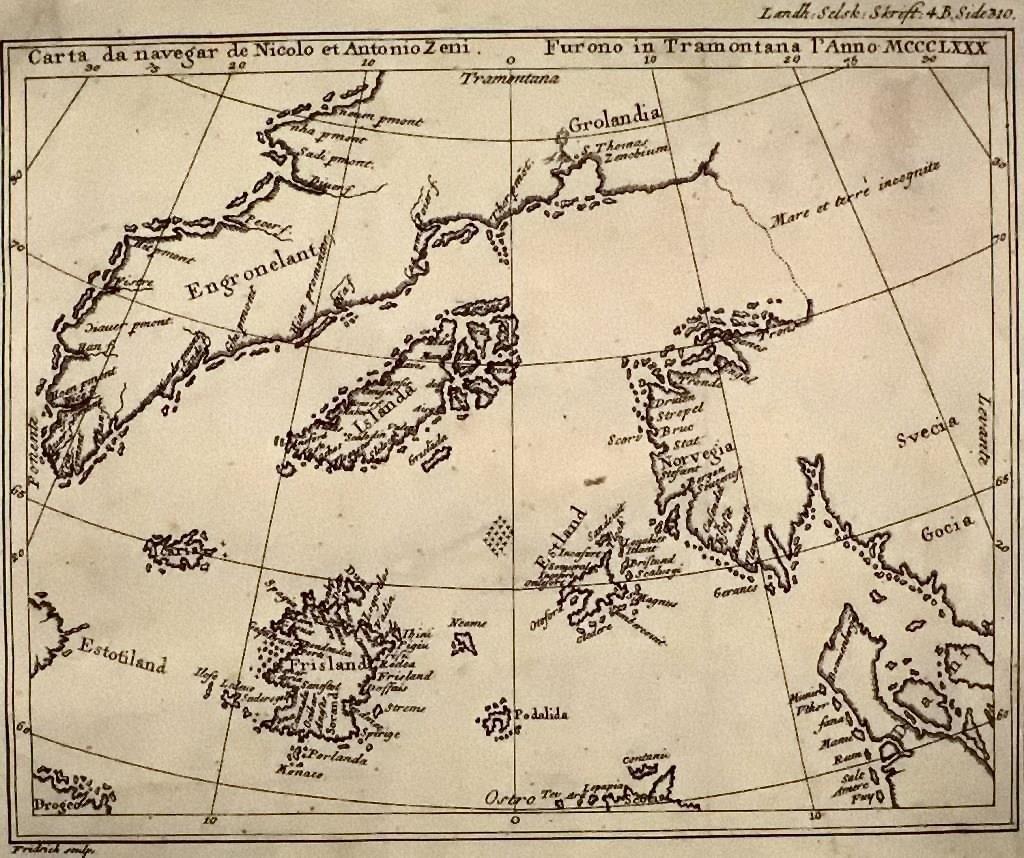

Duišan is a language spoken by the inhabitants of the imaginary island of Frisland, which was

located between Iceland and Greenland. Even though Frisland is an imaginary island, it

appeared in most of the maritime map from the 1560s through the 1660s. The belief in Frisland

was so strong that a few maps of the island mentioning the names of its regions and major cities

were even drawn and published in the most renowned maps of the 17th century. It was so

systematic that it became a way for the historians to quickly identify the maritime maps of that

period. In the lore of my constructed language however, Frisland is the name only used by the

outsiders. The natives of the island use the word Duišia. Even though none of the island natives

ever came back to Duišia after they left, the people of Duišia, the Duišan, have knowledge of

the outside world thanks to the people they rescue from shipwrecks. It drove the Duišan to

question the nature of their reality and constantly wonder if they are real or not. Infolgedessen,

their society is peacefully divided between the people who think they are real and the people

who think they are imaginary.

Kven, the language I compare Duišan with, is a Finnic language derived from the Finnish

dialects spoken from the 16th to the early 20th century in the northernmost parts of Sweden and

Finland. From the 16th century onwards, peoples from those northern areas started to gradually

settle in Northern Norway, with a peak during the middle of the 19th century (Niemi, 1995). Als

the decades went, the language of the newcomers started to be influenced by the Norwegian

language and the Northern Sámi language. Like the indigenous Sámi people of Norway, Die

Kven were the victims of strong assimilation policies from the middle of the 19th century

through the 1970s. In the early 21th century, the Kven is spoken by less than 2000 individuals

and became officially a language of its own in 2005 (Niemi, 2017).

In this paper, I will compare some of the main features of the Duišan and Kven languages. ICH

start by presenting the sound systems of Duišan and Kven, then their basic nominal system and

finally the basic verbal systems of both languages. The rules and grammar of Kven come from

the book Kvensk grammatikk by Eira Söderholm whereas the concepts and notions used in the

creation of Duišan come from The Art of Language Invention by David Peterson and the

materials presented in the course HIF-1022 Constructed language.

1

The Island of Frisland in the Zeno map (1558)

Source: https://no.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frisland

2

1. The sound systems of Duišan and Kven:

The sound system of both languages is presented through the International Phonetic Alphabet

IPA.

1.1 The vowel system

Duišan Kven

Nasal

Front

Back

Front Back

Unrounded Rounded Unrounded Rounded

Close-mid

Open

ɛ̃

ɔ̃

ɑ̃

Schließen

i iː

Mid

e eː

y yː

ø øː

u uː

o oː

Open æ æː

ɑ ɑː

The vowels alphabet of Duišan for the vowels are a, e, Ich, o, u, und, ê, ø. The nasal sounds are -in,

-an, -on. An accent is put on the vowels i, a and o before the consonant –n when the sound is

not nasalized. The Kven has short and long vowels that affect the meaning of the words and is

identical to the Finnish language. The vowels alphabet is a, e, Ich, o, u, und, ä, ö, å

3

1.2 The consonant system

The Duišan

Bilabial Labiodental Dental Alveolar Postalveolar Palatal Velar

m

P

b

Nasal

Plosive

Affricates

Fricative

voiceless

voiced

Voiceless

voices

voiceless

voiced

Approximant

f

v

ist

t

d

t͡ s

d͡ z

s

z

l

ŋ

k

g

ʁ

t͡ ʃ

d͡ ʒ

ʃ

J

The Kven

Bilabial Labiodental Dental Alveolar Postalveolar Palatal Velar Glottal

Nasal

m

Plosive

voiceless

P

voiced

(b)

voiceless

f

Fricative

voiced

Trill

Approximant

ʋ

ist

t

(d)

s

die

l

ð

ŋ

k

(ɡ)

(ʃ)

h

J

The sound /b, d, ɡ, ʃ/ are only found in loanwords and /ð/ is highlighted in red because it is a

sound that does not exist in Finnish and is unique to Kven.

4

1.3 Basic phonotactics of Duišan and Kven

Duišan

Any of the vowels can be found in the word-finals and word initials positions. There is no

double vowels of the same type and nearly all the vowels can combined to create diphthongs

thanks to the different influences Duišan received from the people rescued from shipwrecks.

A cluster of three consonants can be found anywhere in a word but not in word-finals, wo

one consonant is usually the norm. The consonants /p, b, d, g, ŋ, s, z/ are never word-finals

unless the word is a loan word.

There is a vowel harmony in Duišan. When the ending of a word changes due to a plural form,

the vowel of the plural in that case will always be the same as the one preceding it.

Ex: house: pysín – houses: pysimit / time: veras – times: veraksat

Kven

Kven is similar to the Finnish language when it comes to phonotactics. Any of the vowels can

be found in the word-final and word-initial positions. Almost all the vowels can be doubled

and combined with 18 diphthongs possible. When it comes to the consonant, only /t, s, ist, die, l/

can be word-finals whereas all the consonants except /d/ and /ŋ/ can be word-initial. Es gibt

no consonant clusters on a word-final except for loan words.

The Kven has a strict vocal harmony with two main groups of vowels that do not mix in the

same word. The groups are ä, ö, y and a, o, u. The vowels e and i are used with both groups.

5

2. The basic nominal system of Duišan and Kven

2.1 Personal pronouns

In Duišan, when a verb starts with a vowel, the last vowel of the pronoun disappears and take

an apostrophe, ex: mo – m’. Modua in Duišan is based on the French pronoun on.

2.2 Possessive pronouns

The possessive pronouns of both Kven and Duišan are placed before the substantive

possessed.

Ex: Duišan: Dalo pysín: my house / Kven: Minun huonet: my house

6

2.3 Word types

There is no cases in Duišan but words decline when they take the plural or are compounded

with other words. In Kven, there is over 13 different cases. Both Duišan and Kven have a base

form for nouns, adjectives and sometimes adverbs. Here are the main word endings and how

they decline when they take a case.

Duišan

Kven

The plural in both Kven and Duišan is marked by –t at the end of the words.

Ex: Duišan: house – pysín – pysimit / time – veras – veraksat

Kven: idea – ajatus – ajatukset / truth – totuus – tottudet

7

Noun typeStemHousePysínpysimi-CityRaušotánRaušotama-LeftSoidonSoidomo-Aloneiata (one vocal ending)iata-TimeVerasVerks-Godtottode-Personiatešiateče-Bolarpontponne-Rocknaifnaive-WeatherOsea (two vocals ending)Oset-Egg/yellowénkalénkal-Noun typeStemMorningaamuaamu-countrymaamaa-coffeekaffikaffi-wintertalvitalve-languagekielikiele-watervesiveđe-Boatvenetvenhee-Guest/unknownvierasvierhaa-Ideaajatusajatuks-Personihminenihmise-memberjäsenjäsene-keysavvainavvaime-loverakkhausrakkhauđe-unluckyonnetononnetoma-truthtottuustottuđe- / tottuksi-

2.4 Preposition systems

Kven has very few prepositions and uses a system of 13 cases: nominative, genitive, essive,

partitive, translative, inessive, illative, adessive, elative, ablative, allative, comitative and

abessive. Duišan on the other hand uses many prepositions that combine to create words of their

own. Here are some examples:

2.5 Adjectives

In Kven, all adjectives go before the noun they qualify, taking their cases and numbers. Der

relational adjectives are also before the nouns.

In Duišan, the qualitative adjectives are congruent in number with the noun they qualify (except

in some cases for the adjectives ending in –e). The qualificative adjectives expressing an

opinion-impression and indicating a color are placed after the nouns. Aber, the adjectives

referring to the weather and physical features are placed before the nouns. While qualificative

adjectives are not created following any particular set of rules, the relational adjectives are

formed from a substantive with the suffix –nín added and goes after the substantive. Many

adjectives in Duišan can also be used as substantives.

Ex: Die Welt: dal’iktevašín – The world day: dal’iktevašiminín turpa

8

At/to – one : At the / to the – onedal (sg), onedame (pl) / at a – ony (sg), onyme (pl) For – veron: For the – Verondal (sg), Verondame (pl) / For a – Verony (sg), Veronyme (pl) In – Sasan: in the – sasandal (sg), sasandame (pl) / in a – Sasany (sg), Sasanyme (pl) On – čan: on the – čadal (sg), čadame (pl) / on a – čany (sg), čanyme (pl) In front of – aitron: … the – aitrodal (sg), aitrodame (pl) / … a – aitrony (sg), aitronyme (pl)

3. The basic verbal systems of Duišan and Kven

3.1 Verb types

Duišan has three verb groups and a fourth group with two different endings. The first group

ends with – ute (ex: rániute – to take). the second group – ite (ex: Kačite – to say) and the third

group –ate (ex: avate – to see. The fourth group ends in –otre (ex: potre – to do) and –uatre

(namuatre – to know). There are two auxiliary verbs in Duišan, to be Enotre and to have Obate.

In Kven, the verbs can be regrouped in five main categories (with many subcategories) in dem

the number of syllables and the endings decide of the type. This paper does not present the verb

types of Kven due to their important number and complexity.

3.2 Alignment

In term of alignment, Duišan is a nominative/accusative system marked by a strict word order

Subject-Verb-Object. Kven is also a nominative/accusative verbal system but with a more

flexible word order. The object can be for example placed before the verb depending on the

case it takes.

3.3 Mood and tenses

Duišan has three moods: indicative, imperative and conditional. Kven has the same moods but

some traces of a potential mood that derives from Finnish can be found in some words. In the

indicative mood Duišan has six tenses: gegenwärtig, imperfect, perfect, past perfect, future and

future perfect. Kven has four tenses in the indicative: gegenwärtig, imperfect, perfect and past

perfect, while the future is decided by the context. I will only detail the indicative tenses in

Duišan in this section.

The present tense in Duišan takes an –n at the singular and -ne at the plural, except for the third

person modua.

An -i- marks the imperfect:

9

The perfect tense is formed with to have + past participle, except for the verb of movement that

takes to be, like in French or Italian. Enotre is to be and is one of the few irregular verbs in

Duišan.

For the imperative tense in Duišan, the singular of the second person is the same as in the

indicative present form. The plural of the first person is the indicative plural of to go – žitune

followed by the infinitive. Ex: Let’s speak! = Žitune smavate! /Go[in plural] you speak/. Der

plural of the second person is the same as the indicative present form.

The future tense is formed by adding –r after the vowel without the infinitive and adding the

same vowel followed by –n or –ne.

10

Mo žituín– I went More žituine– we went Dø žituín – you went Dore žituine – you went Tuot žituín – he/she went Totre žituine – they went Diot žituín – it/this/that went Modua žituri – French “on” went

3.4 Aspects

Duišan and Kven have a continuous and progressive aspect. In Duišan, the continuous tense is

built on the structure enotre pari (to be + pari ) + infinitive.

Ex: Mo šén pari rániute = I am taking.

The present participle is built with only Pari + infinitive.

Ex: Pari rániute – While/when taking.

A derivative of pari is para as a suffix in the form substantive/adjective + para, a suffix

referring to the entrance into a certain state and function as an archaic translative case (Die

vowel before para is the same vowel that the last vowel of the base form).

Ex: to go to war – žitute vitunaksapara (to go war-entering);(Vitunas: war)

to go down in history – žitute banakiksipara (banakis is the nominative form).

In Kven, the continuous aspect marked by to be is followed with the verb at the third infinitive

Ex: Mie oon syömässä – I am eating. What is called the second infinitive in Kven is used to

marked something that is done at the same time Ex: Tullessani kotiin satoi – When I came

home, it rained.

The Kven has a translative case of its own adding up -ksi to the stem of the word

Ex: Mie puhun franskaksi – I am speaking in French (im Augenblick)

Mie tulen kippeeksi – I am getting sick (Litteraly I come sick)

3.5 Interrogative words

The interrogative words in Duišan are invariable, while in Kven some of them change

depending on the cases or the number. The structure Verb + subject at the beginning of a

question is used in both Duišan and Kven, but Kven adds the suffix particle – ko/kö after the

verb. Here are some examples in Duišan:

Who – Pam, Was – kaima, Was (exclamative and accusative) – kait, Where – tau

When – poimi, Why – veronkait, How – Kaimaka

11

3.6 Adverbs of manner

In Duišan, the mark of the adverbs is –aksa or – ksa added to the adjective.

Ex: Slow – Pios – Slowly – Pioksaksa / Fast – Striván – quickly – Strivamaksa

In Kven, the mark of an adverb is – sti added to the adjective

Ex: Nice – Siivo – Siivosti / Slow – Hiđas – Hithaasti

3.7 Negation

In Duišan, the negation is marked by two elements when the personal pronouns are used. In

that case, the personal pronoun transforms, and a second negative elements can be added after

the verb, to mark an emphasis (but can be omitted otherwise). In Kven, the negation is marked

by a particle in front of the verb at the negative form, and the negative particle changes for each

person.

Amo: ICH – not Amore: We – not

Ado: Du – not Adore: Du – not

Atuo: he/she – not Adotre: Sie – not

Adit: it -not

Amodua: ‘everybody/nobody’ – not

The second element of negation is ‘kán’ and follows the verb when the personal pronouns are

not used. If used alone it emphazes

Ex: I don’t speak Duišan: Amo smavan Duišan

Henry don’t speak: Henry smavan kán Duišan

12

3.8 Evidentiality and derivation patterns

Duišan is a verb-framed language and the evidentiality is marked by a verb in context without

the infinitive and the added suffix particles – arpi / -narpi. Derivational patterns can sometimes

occur with different suffixes, but they come from archaic language forms.

Ex: namuatre – to know / Namuanarpi: as far as [eins] knows

Kven on the other hand is a satellite-frames language. Evidentiality on the first person is built

on the infinitive verb with the what used to be the Finnish possessive suffix -ni.

Ex: Tietääkseni ‘to my knowledge, as far as I know’

13

3. Leipzig Glossing Rules: A short text in Duišan

This last section contains a small text in Duišan that is analyzed by using the Leipzig glossing

rules.

We are the Duišan, the people who might not exist. We live on an Island that people never came

back from but that you heard from the sailors and cartographers. We fish, we farm, and we

herd sheep and goats.

More žéne dame duišamat, dal’iatia pám akaines kán invuatre. More napurine čan ny

duišanosti kymet dam’iatinakat pečarine niet mavín čan dore kaivaine atadame

stradavemêkset nav katkarasvemêkset. More vladamine, more akorasune dal rata nav more

akorasune dame bailet nav kornarit.

More žéne dame duiša-mat

We be-PRS-PL the-PL Duišan-PL

‘We are the Duišan’

dal’ iatia pám akaines kán invuatre.

the people who can-COND not-NEG exist

‘the people who might not exist’

More napurine čan ny duišanosti

We live-PRS-SG on an Island

‘We live on an Island’

Kymet dam’iatinakat pečarine niet mavín

that-REL-PL people come.back.from-PST-PL never but

‘that people never came back from but’

čan dore kaivaine atadame stradavemêkse-t nav katkarasvemêkse-t

That you hear-PST-SG from.the;ART;PL sailor-PL and cartographer+PL

‘that you heard from the sailors and cartographers’

More vladamine, more akorasune dal rata nav

We fish-PRS-PRL we take.care.of-PRS-PRL the earth and

‘We fish, we farm and’

more akorasune dame baile-t nav kornari-t

we take.care.of-PRS-PRL the-PRL sheep-PRL and goat-PRL.

‘we herd sheep and goats’.

14

Referenzen

Niemi, Einar (1995). History of minorities: the Sami and the Kvens. In William H. Hubbard et

al. (Hrsg.) Making a historical culture. Historiography in Norway pp. 325-346. Scandinavian

Universitätsverlag, Oslo.

Niemi, E. (2017). Fornorskingspolitikken overfor samene og kvenene. [Norwegianization

politics towards the Sami and Kven]. In N. Brandal, C. Ein. Døving, & ICH. Thorson. Plesner

(Hrsg.), Nasjonale minoriteter og urfolk i norsk politikk fra 1900 til 2016 [National minorities

and indigenous peoples in Norwegian politics from 1900 to 2016] pp. 131–150. Oslo,

Norwegen: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

Peterson, David J (2015). The Art of Language Invention: From Horse-Lords to Dark Elves,

the Words Behind World-Building. Penguin Publishing Group, New York

Söderholm, Eira (2017). Kvensk Grammatikk. Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

https://doi.org/10.23865/noasp.24

15

Appendix

Ein. Numeral system

Numerals 1-10

1: Ny 6: Pimán

2: Dy 7: Atki

3: čako 8: Nitki

4: Katko 9: Arimki

5: žalko (also hand) 10: Nyse

Numerals 10-20

11: Nyvaika 16: Pimánvaika

12: Dyvaika 17: Atgivaika

13: čagovaika 18: Nitgivaika

14: Katgovaika 19: Arimgivaika

15: žalgovaika 20: Dynyse

Numerals 21-100

21: Dynyseny 60: Pimányse

27: Dynysatki 70: Atkinyse

29: Dynysarimki 80: Nitkimyse

30: čakonyse 90: Arimkinyse

B. Colors

Grey – énšiš

Yellow – énkal (also egg)

Black – Proton

White – šiš

Red – Arán

Brown – sule

Blue – Darile

Green – Marsis

Violetti – Korgra

Orange – laranra

16

C. Glossary

Dark orange – laranra proti

Light orange – laranra šiš

Akate: to can

Akorasute: to take care of

At: von

Atadame: des (pl.)

Avate – to see

Baile: sheep

Čan: auf

Dal: Die

Dame: Der (pl.)

Daši: winter

Dore: Du (pl.)

Duiša: Frisland

Duišan: the Duišan people and the Duišan anguage

Duišanosti: Island

Énkal: egg ; yellow

Enotre: to be

Iatinakat

Iata:allein

Iateš: person

Iatia: Menschen

Irún: before

Ikte: alle

Iktevašín: world

Ikturpa: stets

Invuatre: to exit

Kačite – to say

Kaivatre: zu hören

Kán: not

Kar: that/which (relative)

17

Karikar: a few

Katkaras: something small and square

Katkarasvemês: cartographer

kornari: Goat

Kyne: of which (sg.)

Kymet: of which (pl.)

Mavín: Aber

Mehr: Wir

Naif: Felsen

Napurite: to live

Nav: und

Niet: never

Ny: Ein

Nyme: Ein (plural)

Obate: to have

Osea: weather

Pančo: these/those

Pios: slow

Pont: bolar

potre – to do

proti – dark

Pysín: house

Pám: Was

pečarite: to come back

Očan: over/above

Rániute – to take

Rata: Erde

Rauči: market

Raušotán: city

Soidon: Links

Strada: sea

Stradavemês: sailor

18

Striván: fast

Strym: now

Šiš: (adj.)Weiß ; Licht

Tot: god

Turpa: day

Vačo: this/that

Veras: Zeit

Veroimi: Weil

Vlanamite: to rain

19